Flow in positive psychology, also known colloquially as being in the zone or locked in, is the mental state in which a person performing some activity is fully immersed in a feeling of energized focus, full involvement, and enjoyment in the process of the activity. In essence, flow is characterized by the complete absorption in what one does, and a resulting transformation in one's sense of time.[1] Flow is the melting together of action and consciousness; the state of finding a balance between a skill and how challenging that task is. It requires a high level of concentration. Flow is used as a coping skill for stress and anxiety when productively pursuing a form of leisure that matches one's skill set.[2]

Named by the psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi in 1970, the concept has been widely referred to across a variety of fields (and is particularly well recognized in occupational therapy).[3][need quotation to verify]

The flow state shares many characteristics with hyperfocus.[4] However, hyperfocus is not always described in a positive light. Some examples include spending "too much" time playing video games or becoming pleasurably absorbed by one aspect of an assignment or task to the detriment of the overall assignment. In some cases, hyperfocus can "capture" a person, perhaps causing them to appear unfocused or to start several projects, but complete few. Hyperfocus is often mentioned "in the context of autism, schizophrenia, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder – conditions that have consequences on attentional abilities."[4]

Flow is an individual experience and the idea behind flow originated from the sports-psychology theory about an Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning. The individuality of the concept of flow suggests that each person has their subjective area of flow, where they would function best given the situation. One is most likely to experience flow at moderate levels of psychological arousal, as one is unlikely to be overwhelmed, but not understimulated to the point of boredom.[5]

Flow is so named because, during Csíkszentmihályi's 1975 interviews, several people described their "flow" experiences using the metaphor of a water current carrying them along: "'It was like floating,' 'I was carried on by the flow.'"[6][failed verification][7]

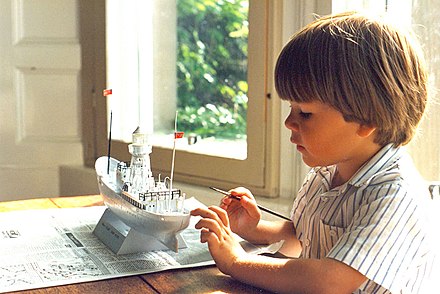

Mihaly Csikszentmihályi and others began researching flow after Csikszentmihályi became fascinated by artists who would essentially get lost in their work.[8] Artists, especially painters, got so immersed in their work that they would disregard their need for food, water and even sleep. The theory of flow came about when Csikszentmihályi tried to understand the phenomenon experienced by these artists. Flow research became prevalent in the 1980s and 1990s, with Csikszentmihályi and his colleagues in Italy still at the forefront. Researchers grew interested in optimal experiences and emphasizing positive experiences, especially in places such as schools and the business world.[9] They also began studying the theory of flow at this time.[10]

The cognitive science of flow has been studied under the rubric of effortless attention.[11]

Jeanne Nakamura and Csíkszentmihályi identify the following six factors as encompassing an experience of flow:[10]

Those aspects can appear independently of each other, but only in combination do they constitute a so-called flow experience. Additionally, psychology writer Kendra Cherry has mentioned three other components that Csíkszentmihályi lists as being a part of the flow experience:[12]

Just as with the conditions listed above, these conditions can be independent of one another.

In any given moment, there is a great deal of information made available to each individual. Psychologists have found that one's mind can attend to only a certain amount of information at a time. According to Csikszentmihályi's 2004 TED talk, that number is about "110 bits of information per second."[13] That may seem like a lot of information, but simple daily tasks take quite a lot of information. Just decoding speech takes about 40–60 bits of information per second,[14] which is why when having a conversation, one cannot focus as much attention on other things.[15]

Generally, people have the ability to decide what they will give their full attention to. This excludes basic distinctive feelings, such as hunger and pain. However, when one is in the flow state, they are completely engrossed with the one task at hand and, without making the conscious decision to do so, lose awareness of all other things: time, people, distractions, and even basic bodily needs.[16][17] According to Csikszentmihályi, this event occurs because all of the attention of the person in the flow state is on the task at hand; there is no more attention to be allocated.[18]

The flow state has been described by Csikszentmihályi as the "optimal experience" in that one gets to a level of high gratification from the experience.[3] Achieving this experience is considered to be personal and "depends on the ability" of the individual.[3] One's capacity and desire to overcome challenges in order to achieve their ultimate goals leads not only to the optimal experience but also to a sense of life satisfaction overall.[3]

There are three common ways to measure flow experiences: the flow questionnaire (FQ), the experience sampling method (ESM), and the "standardized scales of the componential approach."[19]

The FQ requires individuals to identify definitions of flow and situations in which they believe that they have experienced flow, followed by a section that asks them to evaluate their personal experiences in these flow-inducing situations. The FQ identifies flow as multiple constructs, therefore allowing the results to be used to estimate differences in the likelihood of experiencing flow across a variety of factors. Another strength of the FQ is that it does not assume that everyone's flow experiences are the same. Because of this, the FQ is the ideal measure for estimating the prevalence of flow.[20] However, the FQ has some weaknesses that more recent methods have set out to address. The FQ does not allow for a measurement of the intensity of flow during specific activities. This method also does not measure the influence of the ratio of challenge to skill on the flow state.[19]

The ESM requires individuals to fill out the experience sampling form (ESF) at eight randomly chosen time intervals throughout the day. The purpose of this is to understand subjective experiences by estimating the time intervals that individuals spend in specific states during everyday life. The ESF is made up of 13 categorical items and 29 scaled items. The purpose of the categorical items is to determine the context and motivational aspects of the current actions (these items include: time, location, companionship/desire for companionship, activity being performed, reason for performing activity). Because these questions are open-ended, the answers need to be coded by researchers. This needs to be done carefully so as to avoid any biases in the statistical analysis. The scaled items are intended to measure the levels of a variety of subjective feelings that the individual may be experiencing. The ESM is more complex than the FQ and contributes to the understanding of how flow plays out in a variety of situations, however the possible biases make it a risky choice.[19]

Some researchers are not satisfied with the methods mentioned above and have set out to create their own scales. The scales developed by Jackson and Eklund are the most commonly used in research. Mainly because they are still consistent with Csíkszentmihályi's definition of flow and consider flow as being both a state and a trait. Jackson and Eklund created two scales that have been proven to be psychometrically valid and reliable: the flow state scale-2 (which measures flow as a state), and the dispositional flow scale-2 (designed to measure flow as either a general trait or domain-specific trait). The statistical analysis of the individual results from these scales gives a much more complete understanding of flow than the ESM and the FQ.[19]

The flow state can be entered while performing any activity, although it is more likely to occur when the task or activity is wholeheartedly engaged for intrinsic purposes.[18][22] Passive activities such as taking a bath or even watching TV, usually do not elicit a flow experience because active engagement is prerequisite to entering the flow state.[23][24] While the activities that induce flow vary and may be multifaceted, Csikszentmihályi asserts that the experience of flow is similar whatever the activity.[25]

Flow theory postulates that three conditions must be met to achieve flow:

It has been argued that the antecedent factors of flow are interrelated, and as such, a balance between perceived challenges and skills requires that the goals are clear and feedback is effective. Thus, such balance can be identified as the central precondition of flow experience.[27]

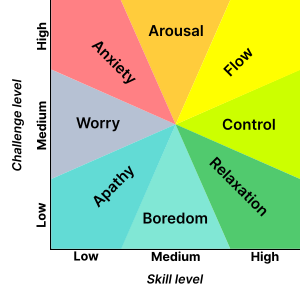

In 1987, Massimini, Csíkszentmihályi and Carli published the eight-channel model of flow .[28] Antonella Delle Fave, who worked with Fausto Massimini at the University of Milan, calls this graph the Experience Fluctuation Model.[29] The model depicts the channels of experience that result from different levels of perceived challenges and perceived skills. The graph illustrates another aspect of flow: it is more likely to occur when the activity is a higher-than-average challenge (above the center point) and the individual has above-average skills (to the right of the center point).[18] The center of the graph where the sectors meet represents the average level of challenge and skill across all individual daily activities. The further from the center an experience is, the greater the intensity of that state of being, whether it is flow or anxiety or boredom or relaxation.[22]

Several problems of the model have been discussed in literature.[27][30] One is that it does not ensure the perceived balance between challenges and skills which is said to be the central precondition of flow experience. Individuals with a low average level of skills and a high average level of challenges, (or the converse) do not necessarily experience a match between skills and challenges when both are above their individual average.[31] Another study found that low challenge situations which were surpassed by skill were associated with enjoyment, relaxation, and happiness, which, they claim, is contrary to flow theory.[32]

Schaffer (2013) proposed seven flow conditions:

Schaffer published a flow condition questionnaire (FCQ), to measure each of these seven flow conditions for any given task or activity.[33]

Some of the challenges to staying in flow include states of apathy, boredom, and anxiety. The state of apathy is characterized by easy challenges and low skill level requirements, resulting in a general lack of interest in the activity. Boredom is a slightly different state that occurs when challenges are few, but one's skill level exceeds those challenges causing one to seek higher challenges. A state of anxiety occurs when challenges are high enough to exceed perceived skill level, causing distress and uneasiness. These states in general prevent achieving the balance necessary for flow.[34] Csíkszentmihályi has said, "If challenges are too low, one gets back to flow by increasing them. If challenges are too great, one can return to the flow state by learning new skills."[12]

Csíkszentmihályi hypothesized that people with certain personality traits may be better able to achieve flow than the average person. These traits include curiosity, persistence, low egotism, and a high propensity to perform activities for intrinsic reasons. People with most of these personality traits are said to have an autotelic personality.[22] The term "autotelic" derives from two Greek words, auto, meaning self, and telos meaning goal. Being autotelic means having a self-contained activity, without the expectation of future benefit, but simply to be experienced.[35][unreliable source?]

There is scant research on the autotelic personality, but results of the few studies that have been conducted suggest that indeed some people are more likely to experience flow than others. One researcher (Abuhamdeh, 2000) found that people with an autotelic personality have a greater preference for "high-action-opportunity, high-skills situations that stimulate them and encourage growth" compared to those without an autotelic personality.[22] It is in such high-challenge, high-skills situations that people are most likely to experience flow.

Experimental evidence shows that a balance between individual skills and demands of the task (compared to boredom and overload) only elicits the flow experience in individuals having an internal locus of control[36] or a habitual action orientation.[37] Several correlational studies found need for achievement to be a personal characteristic that fosters flow experiences.[38][39][40]

Autotelic Personality also has been shown in studies to correlate and show overlapping of flow in personal life and the Big Five Personality Traits of Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness to Experience. More particularly the traits of agreeableness and extraversion. Study of Autotelic Personality is difficult as most studies are performed through self-evaluation, as an Autotelic Personality is difficult to observe.[41][42]

Group flow (or team flow) is notably different from independent flow, as it is inherently mutual. Group flow is attainable when the performance unit is a group, such as a team or musical group. When groups cooperate to agree on goals and patterns, social flow, commonly known as group cohesion, is much more likely to occur. If a group still has not entered flow, a team-level challenge may stimulate the group to harmonize.[43] Group flow is different from synchronized solitary flow, in which a group is simultaneously experiencing individual flow. Group Flow occurs in an interpersonal manner, in which the act of others being present is inherent to the cause of the state of flow.[44]

In research presented in a review written by PLoS ONE,[44] it is stated, "Group contexts introduce many additional variables that cause individuals to act, think, and feel differently during group situations compared to solitary situations." Due to these additional variables, the cause and effect of flow are vastly different and unique to the experience of individual flow, hence providing evidence for the existence of a separate flow state: group flow.

Snijdewint[45] studies the correlation of the physiological effect of a group that simultaneously reports a "flow" state. This research concludes that between many similar studies when a participant reports a feeling of flow state (in synchronization or due to a group environment), there are similarities in the cardiovascular triggers[46] that the participant's experience.

Only Csíkszentmihályi seems to have published suggestions for extrinsic applications of the flow concept, such as design methods for playgrounds to elicit the flow experience. Other practitioners of Csíkszentmihályi's flow concept focus on intrinsic applications, such as spirituality, performance improvement, or self-help.

Flow state theory suggests that when individuals are in a state of flow, they experience deep immersion, focus, and intrinsic motivation in their activities.[47] In the context of education, flow has been associated with increased student engagement, which is a key determinant of learning success .

Numerous studies have examined the relationship between flow and student engagement, demonstrating positive associations. For example, Csikszentmihalyi and Larson (1984) found that students who reported experiencing flow during their academic tasks exhibited higher levels of engagement, concentration, and enjoyment. Similarly, Cho and Lee (2017) discovered that flow experiences positively correlated with student engagement in a college classroom setting.[48]

Flow state research has also explored its impact on learning outcomes, such as knowledge acquisition, skill development, and creativity. When students are in a state of flow, they are more likely to experience a heightened sense of focus, concentration, and intrinsic motivation, which can lead to improved learning outcomes.[49]

Studies have shown that flow experiences can enhance cognitive processes related to learning. For instance, Schüler and Brunner (2009) found that university students who reported being in a state of flow while studying demonstrated better information recall and problem-solving abilities. In addition, studies by Simons and Dewitte (2004) and Jackson and Csikszentmihalyi (1999) revealed that flow experiences positively influenced creativity and innovation among students.[citation needed]

The concept of flow has been applied to various educational settings and practices, offering valuable insights for teaching and learning. Here are a few notable applications:

These applications demonstrate the potential benefits of integrating flow state theory into educational practices. However, further research is needed to explore the specific strategies and interventions that effectively foster flow in educational settings.

In education, the concept of overlearning plays a role in a student's ability to achieve flow. Csíkszentmihályi[3] states that overlearning enables the mind to concentrate on visualizing the desired performance as a singular, integrated action instead of a set of actions. Challenging assignments that (slightly) stretch one's skills lead to flow.[54]

In the 1950s British cybernetician Gordon Pask designed an adaptive teaching machine called SAKI, an early example of "e-learning". The machine is discussed in some detail in Stafford Beer's book "Cybernetics and Management".[55] In the patent application for SAKI (1956),[56] Pask's comments (some of which are included below) indicate an awareness of the pedagogical importance of balancing student competence with didactic challenge, which is quite consistent with flow theory:

If the operator is receiving data at too slow a rate, he is likely to become bored and attend to other irrelevant data.

If the data given indicates too precisely what responses the operator is required to make, the skill becomes too easy to perform and the operator again tends to become bored.

If the data given is too complicated or is given at too great a rate, the operator is unable to deal with it. He is then liable to become discouraged and lose interest in performing or learning the skill.

Ideally, for an operator to perform a skill efficiently, the data presented to him should always be of sufficient complexity to maintain his interest and maintain a competitive situation, but not so complex as to discourage the operator. Similarly these conditions should obtain at each stage of a learning process if it is to be efficient. A tutor teaching one pupil seeks to maintain just these conditions.

Around 2000, it came to the attention of Csíkszentmihályi that the principles and practices of the Montessori Method of education, seemed to purposefully set up continuous flow opportunities and experiences for students. Csíkszentmihályi and psychologist Kevin Rathunde embarked on a multi-year study of student experiences in Montessori settings and traditional educational settings. The research supported observations that students achieved flow experiences more frequently in Montessori settings.[57][58][59]

Musicians, especially improvisational soloists, may experience a state of flow while playing their instrument.[60]Research has shown that performers in a flow state have a heightened quality of performance as opposed to when they are not in a flow state.[61] In a study performed with professional classical pianists who played piano pieces several times to induce a flow state, a significant relationship was found between the flow state of the pianist and the pianist's heart rate, blood pressure, and major facial muscles. As the pianist entered the flow state, heart rate and blood pressure decreased, and the major facial muscles relaxed. This study further emphasized that flow is a state of effortless attention. In spite of the effortless attention and overall relaxation of the body, the performance of the pianist during the flow state improved.[62]

Groups of drummers go through a state of flow when they sense a collective energy that drives the beat, something they refer to as getting into the groove or entrainment. Likewise, drummers and bass guitarists often describe a state of flow when they are feeling the downbeat together as being in the pocket.[63] Researchers have measured flow through subscales; challenge-skill balance, merging of action and awareness, clear goals, unambiguous feedback, total concentration, sense of control, loss of self-consciousness, transformation of time and autotelic experience.[64]