En la historia de Australia , la ocupación ilegal era el acto de ocupar extrajudicialmente extensiones de tierra de la Corona , generalmente para pastoreo de ganado . Aunque la mayoría de los ocupantes ilegales inicialmente no tenían derechos legales sobre la tierra que ocupaban, la mayoría fueron gradualmente reconocidos por las sucesivas autoridades coloniales como los legítimos propietarios de la tierra debido a que estaban entre los primeros (y a menudo únicos) colonos blancos en su área. El término squattocracy , un juego de palabras con aristocracia , fue acuñado para referirse a los ocupantes ilegales como clase social y al inmenso poder sociopolítico que poseían. [1]

El término squatter se deriva de su uso en inglés como un término despectivo para una persona que se había instalado en un lugar sin tener derecho legal a reclamarlo. El uso de squatter en los primeros años de la colonización británica de Australia tenía una connotación similar, refiriéndose principalmente a una persona que había "ocupado ilegalmente" tierras aborígenes con fines pastorales u otros. [ cita requerida ] En su contexto despectivo inicial, el término se aplicaba a menudo a la ocupación ilegítima de tierras por parte de convictos o ex convictos con permiso de residencia ( emancipistas ).

Sin embargo, a partir de mediados de la década de 1820, la ocupación de tierras "desocupadas" sin título legal se hizo más común, a menudo llevada a cabo por personas de los escalones superiores de la sociedad colonial. A medida que se empezó a exportar lana a Inglaterra y la población colonial aumentó, la ocupación de tierras de pastoreo para la cría de ganado vacuno y ovino se convirtió progresivamente en una actividad más lucrativa. La ocupación ilegal de tierras se había generalizado tanto a mediados de la década de 1830 que la política del Gobierno de Nueva Gales del Sur hacia esta práctica pasó de la oposición a la regulación y el control. En esa etapa, el término "ocupante ilegal" se aplicaba a quienes ocupaban tierras en virtud de un contrato de arrendamiento o licencia de la Corona, sin la connotación negativa de épocas anteriores.

El término pronto desarrolló una asociación de clase, sugiriendo un estatus socioeconómico elevado y una actitud empresarial. En 1840, los ocupantes ilegales eran reconocidos como algunos de los hombres más ricos de la colonia de Nueva Gales del Sur, muchos de ellos de familias inglesas y escocesas de clase media y alta. A medida que la tierra "desocupada" con frente a agua permanente se hizo más escasa, la adquisición de terrenos requirió cada vez mayores desembolsos de capital. Un "terreno" se define en Reminiscencias de Australia, con pistas sobre la vida del okupa de Christopher Pemberton Hodgson de 1846 como: "tierra reclamada por el okupa como paso de ovejas, abierta, tal como la naturaleza la dejó, sin ninguna mejora por parte del okupa". [2]

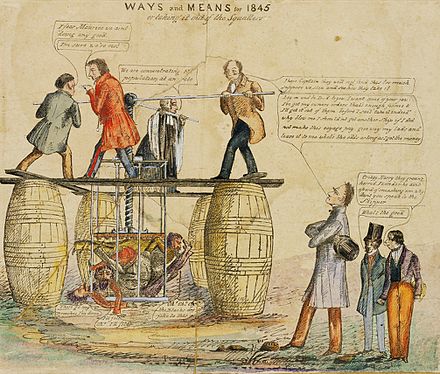

Con el tiempo, el término squatter pasó a referirse a una persona de alto prestigio social que pastorea ganado a gran escala (ya sea que la tierra estuviera en arrendamiento o en propiedad absoluta ). En Australia, el término todavía se usa para describir a los grandes terratenientes, especialmente en áreas rurales con una historia de ocupación pastoral. El término squattocracy , un juego de palabras con "aristocracia", [1] se usó despectivamente ya en 1841. [3]

Cuando la Primera Flota estableció un asentamiento en Sydney Cove en 1788, el gobierno colonial afirmó ser dueño de toda Australia al este del meridiano 135 este , ignorando cualquier reclamo indígena sobre la tierra. La tierra que había sido considerada "desocupada" por los europeos fue descrita como tierra de la Corona . Los gobernadores de Nueva Gales del Sur recibieron autoridad para hacer concesiones de tierras a colonos libres, emancipadores (ex convictos) y suboficiales. Cuando se hicieron concesiones de tierras, a menudo estaban sujetas a condiciones como una renta por abandono (un chelín por 50 acres [200.000 m 2 ] a pagar después de cinco años) y un requisito para que el concesionario residiera y cultivara la tierra. En línea con la política del gobierno británico de asentamiento concentrado en tierras para la colonia, los gobernadores de Nueva Gales del Sur tendieron a ser prudentes al hacer concesiones de tierras. Al final del mandato del gobernador Macquarie en 1821 , se habían concedido menos de 1.000 millas cuadradas (2.600 km2 ) de tierra en la colonia de Nueva Gales del Sur.

Sin embargo, durante el mandato del gobernador Brisbane , las concesiones de tierras se hicieron con mayor facilidad. Además, las regulaciones introducidas durante el mandato de Brisbane permitieron a los colonos comprar (con su permiso) hasta 4.000 acres (16 km2 ) a 5 chelines el acre (las tierras de calidad superior se vendían a 7 chelines y 6 peniques). Durante los cuatro años de mandato del gobernador Brisbane, la cantidad total de tierras en manos privadas prácticamente se duplicó. [4]

El impulso que impulsó las actividades de ocupación durante esta primera fase fue la expansión del mercado de carne a medida que la población de Sydney aumentaba. Los primeros pasos para establecer la producción de lana en Nueva Gales del Sur también generaron una mayor demanda de tierras. La ocupación fue llevada a cabo a menudo por colonos emancipadores y nativos que buscaban definir y consolidar su lugar dentro de la sociedad. [5]

A partir de 1824 se promulgaron leyes y reglamentos para limitar la ocupación ilegal de tierras. A partir de 1826 se definieron los "límites de ubicación", también conocidos como los Diecinueve Condados ; más allá de estos límites, no se podía ocupar tierra ilegalmente ni subdividirla y venderla. Esto se debía a los gastos que suponía proporcionar servicios gubernamentales (policía, etc.) y a la dificultad de supervisar a los convictos en una amplia extensión de tierra. Sin embargo, la naturaleza de la industria ovina, que requería acceso a vastas llanuras cubiertas de hierba, hizo que, a pesar de las limitaciones, los okupas a menudo ocuparan tierras mucho más allá de los límites oficiales de la colonia. A partir de 1833, se designaron comisionados de tierras de la Corona en virtud de la Ley de Invasión para gestionar la ocupación ilegal de tierras.

A partir de 1836 se aprobó una legislación para legalizar la ocupación ilegal de tierras, con derechos de pastoreo disponibles por diez libras al año. Esta tarifa se destinaba al arrendamiento de la tierra, en lugar de a la propiedad, que era lo que querían los ocupantes ilegales. Las órdenes del Consejo de 1847 dividían la tierra en zonas pobladas, intermedias y no pobladas, con arrendamientos de pastoreo de uno, ocho y catorce años para cada categoría respectivamente. A partir de entonces, los ocupantes ilegales podían comprar partes de sus tierras, en lugar de limitarse a arrendarlas.

Se sabe que muchos ocupantes ilegales libraron batallas con armas europeas avanzadas contra las comunidades indígenas australianas locales en las áreas que ocupaban, [6] aunque dichas batallas rara vez se investigaron. Estas batallas/masacres son el tema de las guerras históricas , siendo el término para una discusión pública en curso sobre la interpretación que Australia hace de su historia. Los ocupantes ilegales solo fueron procesados ocasionalmente por matar a indígenas. La primera condena de hombres blancos por la masacre de indígenas siguió a la masacre de Myall Creek en 1838, en la que los tribunales coloniales emplearon el estatus de sujeto aborigen por la rara coincidencia de autoridades locales, coloniales e imperiales .

Aunque la vida al principio fue dura para los ocupantes ilegales, muchos de ellos se hicieron muy ricos gracias a sus enormes propiedades y a menudo se los describía como la "okupacracia". Los descendientes de estos ocupantes ilegales a menudo siguen siendo propietarios de importantes extensiones de tierra en la Australia rural, aunque la mayoría de las propiedades más grandes se han dividido o, en las zonas más aisladas, se han vendido a intereses corporativos.

En abril de 1844, el gobernador Gipps dictó dos reglamentos con la intención de remodelar el sistema de ocupación ilegal de terrenos. El primero, publicado en el Boletín Oficial el 2 de abril, permitía a los ocupantes ilegales ocupar terrenos pagando 10 libras por cada 52 km2 . El segundo reglamento permitía a los ocupantes ilegales, tras cinco años de ocupación, comprar 130 hectáreas de terrenos y otorgaba a los compradores la seguridad de la tenencia de todo el terreno durante otros ocho años. A finales de abril, 150 ocupantes ilegales se reunieron en Sídney y protestaron contra los cambios de Gipps, redactando una petición a la Reina y formando la Asociación Pastoral de Nueva Gales del Sur, la primera formalización de la identidad de los ocupantes ilegales como grupo político.

En junio de 1844 se celebró en Melbourne una gran manifestación de ocupación de tierras . Los arrendatarios de las tierras de la Corona llegaron a Melbourne a caballo y marcharon al lugar de la reunión con banderas ondeando, precedidos por un gaitero de las Highlands que tocaba aires marciales. En esta reunión se aprobaron peticiones para ser transmitidas a las distintas ramas de las Legislaturas del Interior y Colonial, solicitando modificaciones en la ley de tierras de la Corona y una separación total del Distrito Medio (Nueva Gales del Sur). En esta reunión se formó una nueva asociación, a la que se denominó Sociedad Pastoral de Felix Australiano. [7]

En la década de 1860, varias colonias aprobaron leyes para permitir la selección .

En la colonia de Victoria , la Ley de Tierras de 1860 permitió la libre selección de tierras de la Corona, incluidas aquellas ocupadas por arrendamientos pastorales.

El proceso de selección de tierras en Queensland comenzó en 1860 y continuó bajo una serie de leyes de tierras en los años posteriores. [8] Separada de Nueva Gales del Sur en 1859, la tierra se consideró el mayor activo de la nueva colonia de Queensland y su prosperidad como colonia se medía de acuerdo con el alcance de la colonización de tierras. La renta de los arrendamientos de tierras era la mayor fuente de ingresos de la colonia. La contienda política inicial fue entre los ocupantes ilegales que controlaban grandes extensiones de tierra y los nuevos inmigrantes que querían pequeñas propiedades de tierra. La recuperación de las tierras de los ocupantes ilegales para dividirlas en granjas más pequeñas (lo que se conoce como asentamiento más cercano) fue promovida por el gobierno de Queensland para atraer inmigrantes a Queensland. Aunque la legislación de Queensland se enmarcó con el objetivo de una política de tierras integral, la presión de ambos grupos condujo a numerosos cambios de reglas sobre las condiciones de ocupación de la tierra y quién tenía prioridad. En consecuencia, hubo más de 50 leyes principales y modificatorias que cubrían toda la legislación de tierras hasta 1910. [8]

En la década de 1860, la posesión de tierras agrícolas por parte de los ocupantes ilegales en la colonia de Nueva Gales del Sur se vio cuestionada con la aprobación de las Leyes de Tierras que permitían a quienes tenían medios limitados adquirir tierras. Con la intención declarada de fomentar un asentamiento más cercano y una asignación más justa de la tierra al permitir la "selección libre antes de la inspección", la legislación de Leyes de Tierras se aprobó en 1861. Las leyes pertinentes se denominaron Ley de Alienación de Tierras de la Corona y Ley de Ocupación de Tierras de la Corona . La aplicación de la legislación se retrasó hasta 1866 en áreas del interior como Riverina, donde los contratos de arrendamiento de ocupación ilegal existentes todavía estaban por vencer. En cualquier caso, la grave sequía en Riverina a fines de la década de 1860 inicialmente desalentó la selección en áreas excepto aquellas cercanas a los municipios establecidos. La actividad de selección aumentó con estaciones más favorables a principios de la década de 1870.

Tanto los selectores como los ocupantes ilegales utilizaron el amplio marco de las Leyes de Tierras para maximizar sus ventajas en la lucha por la tierra que siguió. Hubo una manipulación general del sistema por parte de los ocupantes ilegales, selectores y especuladores por igual. La legislación aseguró el acceso a la tierra del ocupante ilegal para el selector, pero a partir de entonces lo dejó en la práctica abandonado a su suerte. Las enmiendas aprobadas en 1875 intentaron remediar algunos de los abusos perpetrados bajo la legislación original de selección.

Sin embargo, el descontento era generalizado y a principios de la década de 1880 se produjo un cambio político que llevó a la creación de una comisión para investigar los efectos de la legislación agraria. El comité de investigación Morris y Ranken, que presentó su informe en 1883, descubrió que el número de granjas establecidas era un pequeño porcentaje de las solicitudes de selección en virtud de la Ley, especialmente en áreas de escasas precipitaciones, como Riverina y el bajo río Darling. La mayor parte de las selecciones fueron realizadas por ocupantes ilegales o sus agentes, o por selectores que no pudieron establecerse o que buscaban obtener ganancias mediante la reventa. La Ley de Tierras de la Corona de 1884, introducida a raíz de la investigación Morris-Ranken, buscó un compromiso entre la integridad de los grandes arrendamientos pastorales y los requisitos políticos de igualdad de disponibilidad de tierras y patrones de asentamiento más cercanos. La Ley dividió las áreas pastorales en Áreas de Arrendamiento (mantenidas bajo arrendamientos a corto plazo) y Áreas Reanudadas (disponibles para asentamiento como arrendamientos de granjas más pequeñas) y permitió el establecimiento de Juntas de Tierras locales. [9]

Antes de 1851, los ocupantes ilegales pagaban una tasa de licencia de 10 libras al año (independientemente de la superficie), sin garantía de tenencia de un año para el siguiente. Después de 1851, se podían adquirir arrendamientos por 14 años, con un alquiler anual. [10] La Ley de Tierras de Strangways de 1869 preveía la sustitución de grandes áreas de pastoreo por explotaciones agrícolas intensivas más próximas y más pobladas .

Una proporción significativa de los okupantes se opuso al movimiento de autodeterminación de los trabajadores que cobró impulso en las últimas décadas del siglo XIX en Australia. Los acontecimientos de la huelga de esquiladores de 1891 y las duras medidas de respuesta adoptadas por el gobierno y los okupantes dejaron un amargo legado que afectó negativamente a las relaciones de clase en las décadas siguientes.

Históricamente, la squattocracy ha mantenido estrechos vínculos con Gran Bretaña. Muchas familias conservaron propiedades tanto en Gran Bretaña como en Australia, y a menudo se retiraron a Gran Bretaña después de hacer fortuna y dejaron grandes extensiones de tierra en manos de personal contratado o de sus hijos menores. [11]

Entre las familias australianas más destacadas de la squattocracia se incluyen:

Literatura: El poder de los okupantes, incluida su afinidad con la policía, se menciona en " Waltzing Matilda " de Banjo Paterson , la canción popular más famosa de Australia.

Clara Morison de Catherine Helen Spence explora el poder de Australia para transformar a aquellos con una posición social humilde en Gran Bretaña en la aristocracia de un nuevo mundo. [17]

La novela Bengala de Mary Theresa Vidal de 1860 es una comedia social austeniana que explora la evolución de los modales pseudoaristocráticos que definen la squattocracy. [17]

En Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries , el personaje principal, la Honorable Phyrne Fisher, se resiste a su clase y actúa como contraste con su tía Prudence, que tipifica el esnobismo ganadero y de la okupa.

La película Australia trata sobre el fracaso de muchas grandes propiedades ganaderas a mediados del siglo XX, así como de los estrechos vínculos históricos de la squattocracy con la aristocracia británica, con la que se casaban frecuentemente. La estrella de la película, Nicole Kidman , es pariente de la prominente familia de squatters, los Kidman, que, en el apogeo de su poder, poseían 107.000 millas cuadradas de tierra en Australia Central. [13]

El juego de mesa de estrategia Squatter recibe su nombre de este término.

{{cite book}}: Mantenimiento de CS1: falta la ubicación del editor ( enlace )