Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype. These products are often proteins, but in non-protein-coding genes such as transfer RNA (tRNA) and small nuclear RNA (snRNA), the product is a functional non-coding RNA. The process of gene expression is used by all known life—eukaryotes (including multicellular organisms), prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea), and utilized by viruses—to generate the macromolecular machinery for life.

In genetics, gene expression is the most fundamental level at which the genotype gives rise to the phenotype, i.e. observable trait. The genetic information stored in DNA represents the genotype, whereas the phenotype results from the "interpretation" of that information. Such phenotypes are often displayed by the synthesis of proteins that control the organism's structure and development, or that act as enzymes catalyzing specific metabolic pathways.

All steps in the gene expression process may be modulated (regulated), including the transcription, RNA splicing, translation, and post-translational modification of a protein. Regulation of gene expression gives control over the timing, location, and amount of a given gene product (protein or ncRNA) present in a cell and can have a profound effect on the cellular structure and function. Regulation of gene expression is the basis for cellular differentiation, development, morphogenesis and the versatility and adaptability of any organism. Gene regulation may therefore serve as a substrate for evolutionary change.

The production of a RNA copy from a DNA strand is called transcription, and is performed by RNA polymerases, which add one ribonucleotide at a time to a growing RNA strand as per the complementarity law of the nucleotide bases. This RNA is complementary to the template 3′ → 5′ DNA strand,[1] with the exception that thymines (T) are replaced with uracils (U) in the RNA and possible errors.

In bacteria, transcription is carried out by a single type of RNA polymerase, which needs to bind a DNA sequence called a Pribnow box with the help of the sigma factor protein (σ factor) to start transcription. In eukaryotes, transcription is performed in the nucleus by three types of RNA polymerases, each of which needs a special DNA sequence called the promoter and a set of DNA-binding proteins—transcription factors—to initiate the process (see regulation of transcription below). RNA polymerase I is responsible for transcription of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes. RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcribes all protein-coding genes but also some non-coding RNAs (e.g., snRNAs, snoRNAs or long non-coding RNAs). RNA polymerase III transcribes 5S rRNA, transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, and some small non-coding RNAs (e.g., 7SK). Transcription ends when the polymerase encounters a sequence called the terminator.

While transcription of prokaryotic protein-coding genes creates messenger RNA (mRNA) that is ready for translation into protein, transcription of eukaryotic genes leaves a primary transcript of RNA (pre-RNA), which first has to undergo a series of modifications to become a mature RNA. Types and steps involved in the maturation processes vary between coding and non-coding preRNAs; i.e. even though preRNA molecules for both mRNA and tRNA undergo splicing, the steps and machinery involved are different.[2] The processing of non-coding RNA is described below (non-coding RNA maturation).

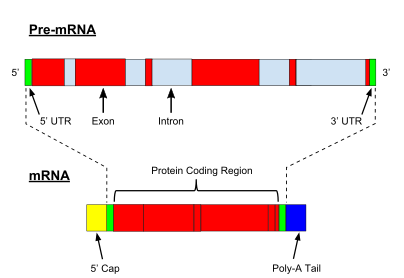

The processing of pre-mRNA include 5′ capping, which is set of enzymatic reactions that add 7-methylguanosine (m7G) to the 5′ end of pre-mRNA and thus protect the RNA from degradation by exonucleases.[3] The m7G cap is then bound by cap binding complex heterodimer (CBC20/CBC80), which aids in mRNA export to cytoplasm and also protect the RNA from decapping.[4]

Another modification is 3′ cleavage and polyadenylation.[5] They occur if polyadenylation signal sequence (5′- AAUAAA-3′) is present in pre-mRNA, which is usually between protein-coding sequence and terminator.[6] The pre-mRNA is first cleaved and then a series of ~200 adenines (A) are added to form poly(A) tail, which protects the RNA from degradation.[7] The poly(A) tail is bound by multiple poly(A)-binding proteins (PABPs) necessary for mRNA export and translation re-initiation.[8] In the inverse process of deadenylation, poly(A) tails are shortened by the CCR4-Not 3′-5′ exonuclease, which often leads to full transcript decay.[9]

A very important modification of eukaryotic pre-mRNA is RNA splicing. The majority of eukaryotic pre-mRNAs consist of alternating segments called exons and introns.[10] During the process of splicing, an RNA-protein catalytical complex known as spliceosome catalyzes two transesterification reactions, which remove an intron and release it in form of lariat structure, and then splice neighbouring exons together.[11] In certain cases, some introns or exons can be either removed or retained in mature mRNA.[12] This so-called alternative splicing creates series of different transcripts originating from a single gene. Because these transcripts can be potentially translated into different proteins, splicing extends the complexity of eukaryotic gene expression and the size of a species proteome.[13]

Extensive RNA processing may be an evolutionary advantage made possible by the nucleus of eukaryotes. In prokaryotes, transcription and translation happen together, whilst in eukaryotes, the nuclear membrane separates the two processes, giving time for RNA processing to occur.[14]

In most organisms non-coding genes (ncRNA) are transcribed as precursors that undergo further processing. In the case of ribosomal RNAs (rRNA), they are often transcribed as a pre-rRNA that contains one or more rRNAs. The pre-rRNA is cleaved and modified (2′-O-methylation and pseudouridine formation) at specific sites by approximately 150 different small nucleolus-restricted RNA species, called snoRNAs. SnoRNAs associate with proteins, forming snoRNPs. While snoRNA part basepair with the target RNA and thus position the modification at a precise site, the protein part performs the catalytical reaction. In eukaryotes, in particular a snoRNP called RNase, MRP cleaves the 45S pre-rRNA into the 28S, 5.8S, and 18S rRNAs. The rRNA and RNA processing factors form large aggregates called the nucleolus.[15]

In the case of transfer RNA (tRNA), for example, the 5′ sequence is removed by RNase P,[16] whereas the 3′ end is removed by the tRNase Z enzyme[17] and the non-templated 3′ CCA tail is added by a nucleotidyl transferase.[18] In the case of micro RNA (miRNA), miRNAs are first transcribed as primary transcripts or pri-miRNA with a cap and poly-A tail and processed to short, 70-nucleotide stem-loop structures known as pre-miRNA in the cell nucleus by the enzymes Drosha and Pasha. After being exported, it is then processed to mature miRNAs in the cytoplasm by interaction with the endonuclease Dicer, which also initiates the formation of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), composed of the Argonaute protein.

Even snRNAs and snoRNAs themselves undergo series of modification before they become part of functional RNP complex.[19] This is done either in the nucleoplasm or in the specialized compartments called Cajal bodies.[20] Their bases are methylated or pseudouridinilated by a group of small Cajal body-specific RNAs (scaRNAs), which are structurally similar to snoRNAs.[21]

In eukaryotes most mature RNA must be exported to the cytoplasm from the nucleus. While some RNAs function in the nucleus, many RNAs are transported through the nuclear pores and into the cytosol.[22] Export of RNAs requires association with specific proteins known as exportins. Specific exportin molecules are responsible for the export of a given RNA type. mRNA transport also requires the correct association with Exon Junction Complex (EJC), which ensures that correct processing of the mRNA is completed before export. In some cases RNAs are additionally transported to a specific part of the cytoplasm, such as a synapse; they are then towed by motor proteins that bind through linker proteins to specific sequences (called "zipcodes") on the RNA.[23]

For some non-coding RNA, the mature RNA is the final gene product.[24] In the case of messenger RNA (mRNA) the RNA is an information carrier coding for the synthesis of one or more proteins. mRNA carrying a single protein sequence (common in eukaryotes) is monocistronic whilst mRNA carrying multiple protein sequences (common in prokaryotes) is known as polycistronic.

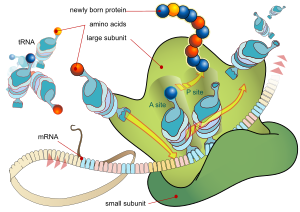

Every mRNA consists of three parts: a 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR), a protein-coding region or open reading frame (ORF), and a 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR). The coding region carries information for protein synthesis encoded by the genetic code to form triplets. Each triplet of nucleotides of the coding region is called a codon and corresponds to a binding site complementary to an anticodon triplet in transfer RNA. Transfer RNAs with the same anticodon sequence always carry an identical type of amino acid. Amino acids are then chained together by the ribosome according to the order of triplets in the coding region. The ribosome helps transfer RNA to bind to messenger RNA and takes the amino acid from each transfer RNA and makes a structure-less protein out of it.[25][26] Each mRNA molecule is translated into many protein molecules, on average ~2800 in mammals.[27][28]

In prokaryotes translation generally occurs at the point of transcription (co-transcriptionally), often using a messenger RNA that is still in the process of being created. In eukaryotes translation can occur in a variety of regions of the cell depending on where the protein being written is supposed to be. Major locations are the cytoplasm for soluble cytoplasmic proteins and the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum for proteins that are for export from the cell or insertion into a cell membrane. Proteins that are supposed to be produced at the endoplasmic reticulum are recognised part-way through the translation process. This is governed by the signal recognition particle—a protein that binds to the ribosome and directs it to the endoplasmic reticulum when it finds a signal peptide on the growing (nascent) amino acid chain.[29]

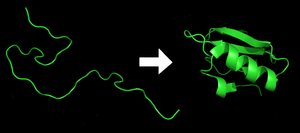

Each protein exists as an unfolded polypeptide or random coil when translated from a sequence of mRNA into a linear chain of amino acids. This polypeptide lacks any developed t