In computer science, a call stack is a stack data structure that stores information about the active subroutines of a computer program. This type of stack is also known as an execution stack, program stack, control stack, run-time stack, or machine stack, and is often shortened to simply the "stack". Although maintenance of the call stack is important for the proper functioning of most software, the details are normally hidden and automatic in high-level programming languages. Many computer instruction sets provide special instructions for manipulating stacks.

A call stack is used for several related purposes, but the main reason for having one is to keep track of the point to which each active subroutine should return control when it finishes executing. An active subroutine is one that has been called, but is yet to complete execution, after which control should be handed back to the point of call. Such activations of subroutines may be nested to any level (recursive as a special case), hence the stack structure. For example, if a subroutine DrawSquare calls a subroutine DrawLine from four different places, DrawLine must know where to return when its execution completes. To accomplish this, the address following the instruction that jumps to DrawLine, the return address, is pushed onto the top of the call stack as part of each call.

Since the call stack is organized as a stack, the caller pushes the return address onto the stack, and the called subroutine, when it finishes, pulls or pops the return address off the call stack and transfers control to that address. If a called subroutine calls on yet another subroutine, it will push another return address onto the call stack, and so on, with the information stacking up and unstacking as the program dictates. If the pushing consumes all of the space allocated for the call stack, an error called a stack overflow occurs, generally causing the program to crash. Adding a block's or subroutine's entry to the call stack is sometimes called "winding", and removing entries "unwinding".

There is usually exactly one call stack associated with a running program (or more accurately, with each task or thread of a process), although additional stacks may be created for signal handling or cooperative multitasking (as with setcontext). Since there is only one in this important context, it can be referred to as the stack (implicitly "of the task"); however, in the Forth programming language the data stack or parameter stack is accessed more explicitly than the call stack and is commonly referred to as the stack (see below).

In high-level programming languages, the specifics of the call stack are usually hidden from the programmer. They are given access only to a set of functions, and not the memory on the stack itself. This is an example of abstraction. Most assembly languages, on the other hand, require programmers to be involved in manipulating the stack. The actual details of the stack in a programming language depend upon the compiler, operating system, and the available instruction set.

As noted above, the primary purpose of a call stack is to store the return addresses. When a subroutine is called, the location (address) of the instruction at which the calling routine can later resume must be saved somewhere. Using a stack to save the return address has important advantages over some alternative calling conventions, such as saving the return address before the beginning of the called subroutine or in some other fixed location. One is that each task can have its own stack, and thus the subroutine can be thread-safe, that is, able to be active simultaneously for different tasks doing different things. Another benefit is that by providing reentrancy, recursion is automatically supported. When a function calls itself recursively, a return address needs to be stored for each activation of the function so that it can later be used to return from the function activation. Stack structures provide this capability automatically.

Depending on the language, operating system, and machine environment, a call stack may serve additional purposes, including, for example:

this pointer.The typical call stack is used for the return address, locals, and parameters (known as a call frame). In some environments there may be more or fewer functions assigned to the call stack. In the Forth programming language, for example, ordinarily only the return address, counted loop parameters and indexes, and possibly local variables are stored on the call stack (which in that environment is named the return stack), although any data can be temporarily placed there using special return-stack handling code so long as the needs of calls and returns are respected; parameters are ordinarily stored on a separate data stack or parameter stack, typically called the stack in Forth terminology even though there is a call stack since it is usually accessed more explicitly. Some Forths also have a third stack for floating-point parameters.

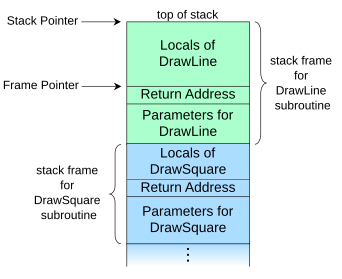

DrawSquare subroutine (shown in blue) called DrawLine (shown in green), which is the currently executing routineA call stack is composed of stack frames (also called activation records or activation frames). These are machine dependent and ABI-dependent data structures containing subroutine state information. Each stack frame corresponds to a call to a subroutine which has not yet terminated with a return. For example, if a subroutine named DrawLine is currently running, having been called by a subroutine DrawSquare, the top part of the call stack might be laid out like in the adjacent picture.

A diagram like this can be drawn in either direction as long as the placement of the top, and so direction of stack growth, is understood. Architectures differ as to whether call stacks grow towards higher addresses or towards lower addresses, so the logic of any diagram is not dependent on this addressing choice by convention.

The stack frame at the top of the stack is for the currently executing routine, which can access information within its frame (such as parameters or local variables) in any order.[1] The stack frame usually includes at least the following items (in push order):

DrawLine stack frame, an address into DrawSquare's code); andWhen stack frame sizes can differ, such as between different functions or between invocations of a particular function, popping a frame off the stack does not constitute a fixed decrement of the stack pointer. At function return, the stack pointer is instead restored to the frame pointer, the value of the stack pointer just before the function was called. Each stack frame contains a stack pointer to the top of the frame immediately below. The stack pointer is a mutable register shared between all invocations. A frame pointer of a given invocation of a function is a copy of the stack pointer as it was before the function was invoked.[2]

The locations of all other fields in the frame can be defined relative either to the top of the frame, as negative offsets of the stack pointer, or relative to the top of the frame below, as positive offsets of the frame pointer. The location of the frame pointer itself must inherently be defined as a negative offset of the stack pointer.

In most systems a stack frame has a field to contain the previous value of the frame pointer register, the value it had while the caller was executing. For example, the stack frame of DrawLine would have a memory location holding the frame pointer value that DrawSquare uses (not shown in the diagram above). The value is saved upon entry to the subroutine. Having such a field in a known location in the stack frame enables code to access each frame successively underneath the currently executing routine's frame, and also allows the routine to easily restore the frame pointer to the caller's frame, just before it returns.

Programming languages that support nested subroutines also have a field in the call frame that points to the stack frame of the latest activation of the procedure that most closely encapsulates the callee, i.e. the immediate scope of the callee. This is called an access link or static link (as it keeps track of static nesting during dynamic and recursive calls) and provides the routine (as well as any other routines it may invoke) access to the local data of its encapsulating routines at every nesting level. Some architectures, compilers, or optimization cases store one link for each enclosing level (not just the immediately enclosing), so that deeply nested routines that access shallow data do not have to traverse several links; this strategy is often called a "display".[3]

Access links can be optimized away when an inner function does not access any (non-constant) local data in the encapsulation, as is the case with pure functions communicating only via arguments and return values, for example. Some historical computers, such as the Electrologica X8 and somewhat later the Burroughs large systems, had special "display registers" to support nested functions, while compilers for most modern machines (such as the ubiquitous x86) simply reserve a few words on the stack for the pointers, as needed.

For some purposes, the stack frame of a subroutine and that of its caller can be considered to overlap, the overlap consisting of the area where the parameters are passed from the caller to the callee. In some environments, the caller pushes each argument onto the stack, thus extending its stack frame, then invokes the callee. In other environments, the caller has a preallocated area at the top of its stack frame to hold the arguments it supplies to other subroutines it calls. This area is sometimes termed the outgoing arguments area or callout area. Under this approach, the size of the area is calculated by the compiler to be the largest needed by any called subroutine.

Usually the call stack manipulation needed at the site of a call to a subroutine is minimal (which is good since there can be many call sites for each subroutine to be called). The values for the actual arguments are evaluated at the call site, since they are specific to the particular call, and either pushed onto the stack or placed into registers, as determined by the used calling convention. The actual call instruction, such as "branch and link", is then typically executed to transfer control to the code of the target subroutine.

In the called subroutine, the first code executed is usually termed the subroutine prologue, since it does the necessary housekeeping before the code for the statements of the routine is begun.

For instruction set architectures in which the instruction used to call a subroutine puts the return address into a register, rather than pushing it onto the stack, the prologue will commonly save the return address by pushing the value onto the call stack, although if the called subroutine does not call any other routines it may leave the value in the register. Similarly, the current stack pointer and/or frame pointer values may be pushed.

If frame pointers are being used, the prologue will typically set the new value of the frame pointer register from the stack pointer. Space on the stack for local variables can then be allocated by incrementally changing the stack pointer.

The Forth programming language allows explicit winding of the call stack (called there the "return stack").

When a subroutine is ready to return, it executes an epilogue that undoes the steps of the prologue. This will typically restore saved register values (such as the frame pointer value) from the stack frame, pop the entire stack frame off the stack by changing the stack pointer value, and finally branch to the instruction at the return address. Under many calling conventions, the items popped off the stack by the epilogue include the original argument values, in which case there usually are no further stack manipulations that need to be done by the caller. With some calling conventions, however, it is the caller's responsibility to remove the arguments from the stack after the return.

Returning from the called function will pop the top frame off the stack, perhaps leaving a return value. The more general act of popping one or more frames off the stack to resume execution elsewhere in the program is called stack unwinding and must be performed when non-local control structures are used, such as those used for exception handling. In this case, the stack frame of a function contains one or more entries specifying exception handlers. When an exception is thrown, the stack is unwound until a handler is found that is prepared to handle (catch) the type of the thrown exception.

Some languages have other control structures that require general unwinding. Pascal allows a global goto statement to transfer control out of a nested function and into a previously invoked outer function. This operation requires the stack to be unwound, removing as many stack frames as necessary to restore the proper context to transfer control to the target statement within the enclosing outer function. Similarly, C has the setjmp and longjmp functions that act as non-local gotos. Common Lisp allows control of what happens when the stack is unwound by using the unwind-protect special operator.

When applying a continuation, the stack is (logically) unwound and then rewound with the stack of the continuation. This is not the only way to implement continuations; for example, using multiple, explicit stacks, application of a continuation can simply activate its stack and wind a value to be passed. The Scheme programming language allows arbitrary thunks to be executed in specified points on "unwinding" or "rewinding" of the control stack when a continuation is invoked.

The call stack can sometimes be inspected as the program is running. Depending on how the program is written and compiled, the information on the stack can be used to determine intermediate values and function call traces. This has been used to generate fine-grained automated tests,[4] and in cases like Ruby and Smalltalk, to implement first-class continuations. As an example, the GNU Debugger (GDB) implements interactive inspection of the call stack of a running, but paused, C program.[5]

Taking regular-time samples of the call stack can be useful in profiling the performance of programs as, if a subroutine's address appears in the call stack sampling data many times, it is likely to act as a code bottleneck and should be inspected for performance problems.

In a language with free pointers or non-checked array writes (such as in C), the mixing of control flow data which affects the execution of code (the return addresses or the saved frame pointers) and simple program data (parameters or return values) in a call stack is a security risk, and is possibly exploitable through stack buffer overflows, which are the most common type of buffer overflow.

One such attack involves filling one buffer with arbitrary executable code, and then overflowing this or some other buffer to overwrite some return address with a value that points directly to the executable code. As a result, when the function returns, the computer executes that code. This kind of an attack can be blocked with W^X,[citation needed] but similar attacks can succeed even with W^X protection enabled, including the return-to-libc attack or the attacks coming from return-oriented programming. Various mitigations have been proposed, such as storing arrays in a completely separate location from the return stack, as is the case in the Forth programming language.[6]