La violencia contra la mujer ( VCM ), también conocida como violencia de género [1] [2] y violencia sexual y de género ( VSG ), [3] son actos violentos cometidos principalmente por hombres o niños contra mujeres o niñas . Dicha violencia a menudo se considera una forma de delito de odio , [4] cometido contra personas específicamente por ser del género femenino , y puede adoptar muchas formas.

La violencia contra las mujeres tiene una larga historia, aunque los incidentes y la intensidad de esa violencia han variado a lo largo del tiempo y entre sociedades. Esta violencia suele considerarse un mecanismo de subyugación de las mujeres, ya sea en la sociedad en general o en una relación interpersonal . [5] [6]

La Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre la eliminación de la violencia contra la mujer afirma que “la violencia contra la mujer es una manifestación de relaciones de poder históricamente desiguales entre hombres y mujeres” y que “la violencia contra la mujer es uno de los mecanismos sociales cruciales por los cuales se fuerza a las mujeres a una posición subordinada en comparación con los hombres”. [7]

Kofi Annan , Secretario General de las Naciones Unidas , declaró en un informe de 2006 publicado en el sitio web del Fondo de Desarrollo de las Naciones Unidas para la Mujer (UNIFEM):

La violencia contra las mujeres y las niñas es un problema de proporciones pandémicas . Al menos una de cada tres mujeres en todo el mundo ha sido golpeada, obligada a mantener relaciones sexuales o ha sufrido algún otro tipo de abuso a lo largo de su vida, y el abusador suele ser alguien conocido de ella. [8]

Diversos organismos internacionales han promulgado una serie de instrumentos internacionales destinados a eliminar la violencia contra la mujer y la violencia doméstica. Por lo general, estos instrumentos comienzan con una definición de lo que es dicha violencia y una propuesta para combatirla. El Convenio de Estambul ( Convenio del Consejo de Europa sobre prevención y lucha contra la violencia contra la mujer y la violencia doméstica ) del Consejo de Europa describe la violencia contra la mujer como "una violación de los derechos humanos y una forma de discriminación contra la mujer" y define la violencia contra la mujer como "todos los actos de violencia de género que tengan o puedan tener como resultado un daño o sufrimiento físico, sexual, psicológico o económico para la mujer, incluidas las amenazas de tales actos, la coacción o la privación arbitraria de la libertad, tanto si se producen en la vida pública como en la privada". [9]

La Convención sobre la eliminación de todas las formas de discriminación contra la mujer (CEDAW) de 1979 de la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas hace recomendaciones relacionadas con la violencia contra la mujer, [10] y la Declaración y Programa de Acción de Viena menciona la violencia contra la mujer. [11] Sin embargo, la resolución de la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas de 1993 sobre la Declaración sobre la eliminación de la violencia contra la mujer fue el primer instrumento internacional en definir explícitamente la violencia contra la mujer y desarrollar el tema. [12] Otras definiciones de violencia contra la mujer se establecen en la Convención Interamericana para Prevenir, Sancionar y Erradicar la Violencia contra la Mujer de 1994 [13] y en el Protocolo de Maputo de 2003. [14]

Además, el término violencia de género se refiere a "todo acto o amenaza de acto destinado a dañar o hacer sufrir a la mujer física, sexual o psicológicamente, y que afecta a la mujer porque es mujer o la afecta desproporcionadamente". [15] La violencia de género se utiliza a menudo indistintamente con la violencia contra la mujer , [1] y algunos artículos sobre la VCM reiteran estas concepciones al afirmar que los hombres son los principales perpetradores de esta violencia. [16] Además, la definición establecida por la Declaración sobre la Eliminación de la Violencia contra la Mujer de 1993 también respaldó la noción de que la violencia tiene sus raíces en la desigualdad entre hombres y mujeres cuando el término violencia se utiliza junto con el término violencia de género . [1]

En la Recomendación Rec(2002)5 del Comité de Ministros a los Estados miembros sobre la protección de las mujeres contra la violencia , el Consejo de Europa estipuló que la violencia contra las mujeres "incluye, pero no se limita a, lo siguiente": [17]

Algunas personas consideran que estas definiciones de la violencia contra las mujeres basadas en el género son insatisfactorias. Estas definiciones entienden que la sociedad es patriarcal, lo que significa relaciones desiguales entre hombres y mujeres. [18] Los opositores a tales definiciones argumentan que no tienen en cuenta la violencia contra los hombres y que el término género , tal como se utiliza en la violencia de género , solo se refiere a las mujeres. Otros críticos argumentan que emplear el término género de esta manera particular introduce nociones de inferioridad y subordinación para la feminidad y superioridad para la masculinidad. [19] [20] No existe una definición actual ampliamente aceptada que cubra todas las dimensiones de la violencia de género. [21]

La violencia contra la mujer puede clasificarse en varias categorías amplias, entre las que se incluyen la violencia ejercida tanto por individuos como por los Estados. Algunas de las formas de violencia perpetradas por individuos son: violación , violencia doméstica , acoso sexual , lanzamiento de ácido , coerción reproductiva , infanticidio femenino , selección prenatal del sexo , violencia obstétrica , violencia de género en línea y violencia colectiva ; así como prácticas consuetudinarias o tradicionales nocivas, como los asesinatos por honor , la violencia relacionada con la dote , la mutilación genital femenina , el matrimonio por secuestro y el matrimonio forzado . Existen formas de violencia que pueden ser perpetradas o toleradas por el gobierno, como la violación en tiempos de guerra , la violencia sexual y la esclavitud sexual durante los conflictos, la esterilización forzada , el aborto forzado , la violencia por parte de la policía y el personal autorizado, la lapidación y la flagelación . Muchas formas de violencia contra la mujer, como la trata de mujeres y la prostitución forzada, suelen ser perpetradas por redes delictivas organizadas. [21] Históricamente, ha habido formas de violencia contra la mujer organizada, como los juicios por brujería en el período moderno temprano o la esclavitud sexual de las mujeres de solaz . La Comisión de Igualdad de Género del Consejo de Europa identifica nueve formas de violencia contra la mujer basadas en el sujeto y el contexto en lugar del ciclo de vida o el período de tiempo: [27] [28]

La Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) ha desarrollado una tipología de violencia contra las mujeres basada en sus ciclos de vida culturales.

El acoso sexual incluye una variedad de acciones con connotaciones sexuales no deseadas, incluidas las transgresiones verbales. [30] La violencia sexual es un término más amplio que se refiere al uso de la violencia para obtener un acto sexual, incluyendo, por ejemplo, la trata. [31] [32] La agresión sexual generalmente se define como contacto sexual no deseado [33] y cuando esto implica penetración sexual o relación sexual se denomina violación .

Las mujeres son las víctimas más frecuentes de violación, generalmente perpetrada por hombres que conocen. [34] La tasa de denuncias, procesamientos y condenas por violación varía considerablemente en diferentes jurisdicciones y refleja, en cierta medida, las actitudes de la sociedad hacia esos delitos. Se considera el delito violento menos denunciado. [35] [36] Después de una violación, la víctima puede enfrentarse a la violencia o amenazas de violencia por parte del violador y, en muchas culturas, de la propia familia y parientes de la víctima. La violencia o intimidación de la víctima puede ser perpetrada por el violador o por amigos y parientes del violador, como una forma de impedir que las víctimas denuncien la violación, castigarlas por denunciarla u obligarlas a retirar la denuncia; o puede ser perpetrada por los familiares de la víctima como castigo por "traer vergüenza" a la familia. A nivel internacional, la incidencia de violaciones registradas por la policía durante 2008 varió entre 0,1 por 100.000 personas en Egipto y 91,6 por 100.000 personas en Lesotho, con 4,9 por 100.000 personas en Lituania como mediana . [37] En todo el mundo, las violaciones a menudo no son denunciadas o manejadas adecuadamente por las fuerzas del orden por una amplia variedad de razones. [38] [39]

En 2011, los Centros para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades (CDC) de Estados Unidos descubrieron que "casi el 20% de todas las mujeres" de ese país sufrieron un intento de violación o una violación en algún momento de sus vidas. Más de un tercio de las víctimas fueron violadas antes de cumplir los 18 años. [40] [41]

Las mujeres que ejercen el trabajo sexual terminan ejerciendo esa profesión por diversas razones. Algunas fueron víctimas de abuso sexual y doméstico. Muchas mujeres han dicho que fueron violadas cuando eran niñas trabajadoras y pueden tener miedo de denunciar los ataques. Cuando denunciaron, muchas mujeres dijeron que el estigma era demasiado grande y que la policía les dijo que se lo merecían y que eran reacias a seguir la política policial. Se argumenta que la despenalización del trabajo sexual ayudaría a las trabajadoras sexuales en este aspecto. [42]

En algunos países, es habitual que los hombres mayores tengan "citas remuneradas" con chicas menores de edad. Estas relaciones se denominan enjo kōsai en Japón y también son comunes en países asiáticos como Taiwán, Corea del Sur y Hong Kong. La OMS condenó las "relaciones sexuales bajo coacción económica (por ejemplo, las colegialas que tienen relaciones sexuales con "sugar daddies" ( sugar baby a cambio de cuotas escolares)") como una forma de violencia contra la mujer. [29]

Las mujeres de ciertas castas inferiores han estado involucradas en la prostitución como parte de una tradición, llamada prostitución intergeneracional . En la Corea premoderna, las mujeres de la casta inferior Cheonmin , conocidas como Kisaeng , eran entrenadas para brindar entretenimiento, conversación y servicios sexuales a los hombres de la clase alta. [43] En el sur de Asia, las castas asociadas con la prostitución hoy incluyen a los Bedias , [44] la casta Perna , [45] los Banchhada , [46] la casta Nat y, en Nepal , el pueblo Badi . [47] [48]

Las mujeres que residen ilegalmente en el país están desproporcionadamente involucradas en la prostitución. Por ejemplo, en 1997, Le Monde diplomatique afirmó que el 80% de las prostitutas en Amsterdam eran extranjeras y el 70% no tenían documentos de inmigración. [49]

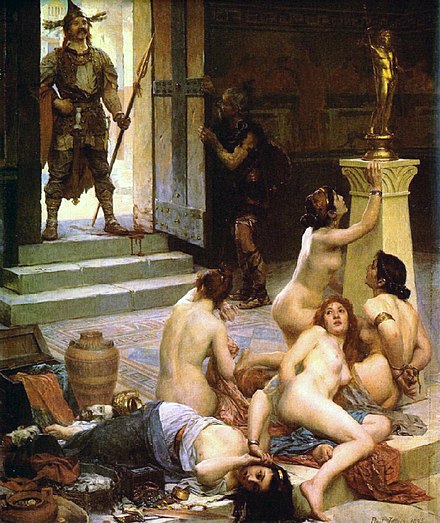

El militarismo produce entornos especiales que permiten un aumento de la violencia contra las mujeres. Las violaciones en tiempos de guerra han acompañado a las guerras en prácticamente todas las épocas históricas conocidas. [50] La violación en el curso de la guerra se menciona varias veces en la Biblia: “Porque yo reuniré a todas las naciones para combatir contra Jerusalén; y la ciudad será tomada, las casas saqueadas y las mujeres violadas…” (Zacarías 14:2). “Sus niños pequeños serán estrellados ante sus ojos, sus casas saqueadas y sus mujeres violadas.” (Isaías 13:16).

Las violaciones de guerra son violaciones cometidas por soldados, otros combatientes o civiles durante un conflicto armado o una guerra o durante una ocupación militar, a diferencia de las agresiones sexuales y las violaciones cometidas entre tropas en servicio militar. También abarca la situación en la que una potencia ocupante obliga a las mujeres a prostituirse o a convertirse en esclavas sexuales . Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el ejército japonés estableció burdeles llenos de " mujeres de solaz ", niñas y mujeres que eran obligadas a convertirse en esclavas sexuales para los soldados, explotando a las mujeres con el fin de crear acceso y derechos para los hombres. [51] [52] La gente rara vez intenta explicar por qué ocurren las violaciones en las guerras. Una explicación que se barajó fue que los hombres en la guerra tienen "impulsos". [53]

Otro ejemplo de violencia contra las mujeres incitada por el militarismo durante la guerra tuvo lugar en el gueto de Kovno . Los prisioneros judíos varones tenían acceso a (y utilizaban) mujeres judías obligadas a ir a los burdeles del campo por los nazis, quienes también las utilizaban. [54]

Durante la Guerra de Liberación de Bangladesh, las violaciones cometidas por miembros del ejército paquistaní y las milicias que los apoyaban dieron lugar a que 200.000 mujeres fueran violadas en un período de nueve meses. Durante la Guerra de Bosnia , las fuerzas armadas serbias utilizaron la violación como un instrumento de guerra sumamente sistematizado, que se dirigía principalmente a mujeres y niñas del grupo étnico bosnio para destruirlas física y moralmente. Se estima que el número de mujeres violadas durante la guerra oscila entre 50.000 y 60.000; hasta 2010, sólo se habían llevado a juicio 12 casos. [55]

El Tribunal Penal Internacional para Ruanda de 1998 reconoció la violación en el genocidio ruandés como un crimen de guerra. [56]

Según un informe, la captura de ciudades iraquíes por parte del Estado Islámico de Irak y el Levante en junio de 2014 estuvo acompañada de un aumento de los crímenes contra las mujeres, incluidos secuestros y violaciones. [57] The Guardian informó de que la agenda extremista del EI se extendía a los cuerpos de las mujeres y que las mujeres que vivían bajo su control estaban siendo capturadas y violadas. [58] A los combatientes se les dice que son libres de tener relaciones sexuales y violar a mujeres cautivas no musulmanas. [59] Haleh Esfandiari, del Centro Internacional de Académicos Woodrow Wilson, ha destacado el abuso de las mujeres locales por parte de los militantes del EI después de capturar una zona. "Normalmente llevan a las mujeres mayores a un mercado improvisado de esclavos y tratan de venderlas. Las niñas más jóvenes... son violadas o casadas con combatientes", dijo, y añadió: "Se basa en matrimonios temporales, y una vez que estos combatientes han tenido relaciones sexuales con estas jóvenes, simplemente las pasan a otros combatientes". [60] En diciembre de 2014, el Ministerio de Derechos Humanos iraquí anunció que el Estado Islámico de Irak y el Levante había asesinado a más de 150 mujeres y niñas en Faluya que se negaron a participar en la yihad sexual . [61]

Durante el genocidio rohingya (2016-presente), las Fuerzas Armadas de Myanmar , junto con la Policía de la Guardia Fronteriza de Myanmar y las milicias budistas de Rakhine , cometieron violaciones en grupo generalizadas y otras formas de violencia sexual contra las mujeres y niñas musulmanas rohingya . Un estudio de enero de 2018 estimó que los militares y los budistas rakhine locales perpetraron violaciones en grupo y otras formas de violencia sexual contra 18.000 mujeres y niñas musulmanas rohingya. [62] Human Rights Watch afirmó que las violaciones en grupo y la violencia sexual se cometieron como parte de la campaña de limpieza étnica del ejército, mientras que la Representante Especial del Secretario General de las Naciones Unidas sobre la Violencia Sexual en los Conflictos, Pramila Patten, dijo que las mujeres y niñas rohingya se convirtieron en el objetivo "sistemático" de violaciones y violencia sexual debido a su identidad étnica y religión . Otras formas de violencia sexual incluyeron la esclavitud sexual en cautiverio militar, la desnudez pública forzada y la humillación. [63] Algunas mujeres y niñas fueron violadas hasta la muerte, mientras que otras fueron encontradas traumatizadas y con heridas abiertas después de haber llegado a campos de refugiados en Bangladesh. Human Rights Watch informó sobre una niña de 15 años que fue arrastrada sin piedad por el suelo durante más de 15 metros y luego violada por 10 soldados birmanos. [64] [65]

La trata de personas se refiere a la adquisición de personas por medios indebidos como la fuerza, el fraude o el engaño, con el objetivo de explotarlas . [66] El Protocolo para prevenir, reprimir y sancionar la trata de personas, especialmente mujeres y niños establece: [67]

Por "trata de personas" se entenderá la captación, el transporte, el traslado, la acogida o la recepción de personas recurriendo a la amenaza o al uso de la fuerza u otras formas de coacción, al rapto, al fraude, al engaño, al abuso de poder o de una situación de vulnerabilidad o a la concesión o recepción de pagos o beneficios para obtener el consentimiento de una persona que tenga autoridad sobre otra, con fines de explotación. La explotación incluirá, como mínimo, la explotación de la prostitución ajena u otras formas de explotación sexual, los trabajos o servicios forzados, la esclavitud o las prácticas análogas a la esclavitud, la servidumbre o la extracción de órganos.

Debido a la naturaleza ilegal de la trata, los datos fiables sobre su alcance son muy limitados. [68] La OMS afirma que "la evidencia actual sugiere firmemente que las personas que son objeto de trata para la industria del sexo y como sirvientes domésticos tienen más probabilidades de ser mujeres y niños". [68] Un estudio de 2006 sobre mujeres víctimas de trata en Europa concluyó que las mujeres estaban sujetas a graves formas de abuso, como violencia física o sexual, que afectaban a su salud física y mental. [68]

La prostitución forzada es aquella que se lleva a cabo como resultado de la coacción de un tercero. En la prostitución forzada, la parte o partes que obligan a la víctima a ser sometida a actos sexuales no deseados ejercen control sobre ella. [69]

Ciertos grupos de hombres han vilipendiado a las mujeres solteras y a las mujeres económicamente independientes. En Hassi Messaoud , Argelia , en 2001, las turbas atacaron a mujeres solteras , atacaron a 95 y mataron al menos a seis [70] [71] y, en 2011, se produjeron ataques similares en toda Argelia. [72] [73]

El acoso es la atención no deseada u obsesiva de un individuo o grupo hacia otra persona, que a menudo se manifiesta a través del acoso persistente , la intimidación o el seguimiento/monitoreo de la víctima. El acoso se entiende a menudo como "una línea de conducta dirigida a una persona específica que haría que una persona razonable sintiera miedo". [74] Aunque los acosadores suelen ser retratados como extraños, la mayoría de las veces son personas conocidas, como parejas anteriores o actuales, amigos, colegas o conocidos. En los EE. UU., una encuesta de NVAW encontró que solo el 23% de las víctimas femeninas fueron acosadas por extraños. [75] El acoso por parte de parejas puede ser muy peligroso, ya que a veces puede escalar a una violencia grave, incluido el asesinato. [75] Las estadísticas policiales de la década de 1990 en Australia indicaron que el 87,7% de los acosadores eran hombres y el 82,4% de las víctimas de acoso eran mujeres. [76]

Un ataque con ácido es el acto de arrojar ácido a alguien con la intención de herirlo o desfigurarlo. Las mujeres y las niñas son las víctimas en el 75-80% de los casos [77] y a menudo están relacionados con disputas domésticas, incluidas disputas por la dote, rechazo de una propuesta de matrimonio o insinuaciones sexuales. [78] El ácido suele arrojarse a las caras, quemando el tejido, a menudo exponiendo y a veces disolviendo los huesos. [79] Las consecuencias a largo plazo de estos ataques incluyen ceguera y cicatrices permanentes en la cara y el cuerpo. [80] [81] Estos ataques son comunes en el sur de Asia, en países como Bangladesh, Pakistán e India; y en el sudeste asiático, especialmente en Camboya. [82]

._Molla_Nasreddin.jpg/440px-Oskar_Shmerling._Free_love_(Forced_marriage)._Molla_Nasreddin.jpg)

Un matrimonio forzado es un matrimonio en el que una o ambas partes se casan contra su voluntad. Los matrimonios forzados son comunes en el sur de Asia, Oriente Medio y África. Las costumbres del precio de la novia y la dote , que existen en muchas partes del mundo, contribuyen a esta práctica. Un matrimonio forzado también suele ser el resultado de una disputa entre familias, donde la disputa se "resuelve" entregando una mujer de una familia a la otra. [83]

La costumbre del rapto de novias sigue existiendo en algunos países de Asia central, como Kirguistán, Kazajstán, Uzbekistán y el Cáucaso, o en algunas partes de África, especialmente Etiopía. La niña o la mujer es raptada por el futuro novio, que a menudo recibe la ayuda de sus amigos. La víctima suele ser violada por el futuro novio, tras lo cual puede tratar de negociar un precio por la novia con los ancianos de la aldea para legitimar el matrimonio. [84]

Algunos habitantes de Tanzania practican matrimonios forzados e infantiles. Las familias venden a las niñas a hombres mayores a cambio de beneficios económicos y, a menudo, las casan tan pronto como llegan a la pubertad, cuando pueden tener tan solo siete años. [85] Para los hombres mayores, estas jóvenes novias actúan como símbolos de masculinidad y logros. Las niñas novias sufren sexo forzado, lo que les causa riesgos para la salud y problemas de crecimiento. [86] Las niñas casadas no suelen terminar la educación primaria. Las estudiantes casadas y embarazadas suelen ser discriminadas, expulsadas y excluidas de la escuela. [85] La Ley de Matrimonio actualmente no aborda cuestiones relacionadas con la tutela y el matrimonio infantil. La cuestión del matrimonio infantil no se aborda lo suficiente en esta ley y solo establece una edad mínima de 18 años para los niños de Tanzania. Es necesario establecer una edad mínima para las niñas para poner fin a estas prácticas y proporcionarles igualdad de derechos y una vida menos dañina. [87]

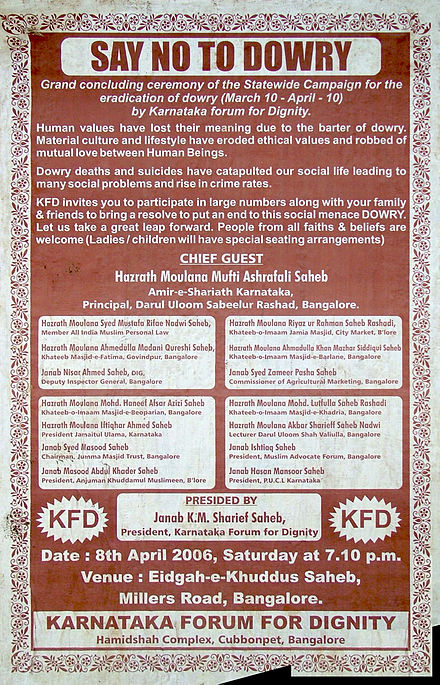

La costumbre de la dote , común en el sur de Asia, especialmente en la India, es el detonante de muchas formas de violencia contra la mujer. La quema de novias es una forma de violencia contra la mujer en la que la novia es asesinada en su casa por su marido o la familia de su marido debido a su insatisfacción con la dote proporcionada por su familia. La muerte por dote se refiere al fenómeno de mujeres y niñas que son asesinadas o se suicidan debido a disputas sobre la dote. La violencia por dote es común en la India, Pakistán, Bangladesh y Nepal. En la India, solo en 2011, la Oficina Nacional de Registros Criminales informó de 8.618 muertes por dote, mientras que las cifras no oficiales sugieren que las cifras son al menos tres veces superiores. [88]

.jpg/440px-Anti-domestic_violence_sign_in_Liberia_panoramio_(193).jpg)

También se ha discutido la relación entre la violencia contra las mujeres y las leyes, regulaciones y tradiciones matrimoniales. [89] [90] El derecho romano dio a los hombres el derecho de castigar a sus esposas, incluso hasta el punto de la muerte. [91] El derecho estadounidense e inglés suscribieron hasta el siglo XX el sistema de coverture , es decir, una doctrina legal bajo la cual, al casarse, los derechos legales de una mujer eran subsumidos por los de su esposo. [92] El common law en los Estados Unidos y en el Reino Unido permitía la violencia doméstica [93] y en el Reino Unido, antes de 1891, el esposo tenía el derecho de infligir castigos corporales moderados a su esposa para mantenerla "dentro de los límites del deber". [94] [95] Hoy, fuera de Occidente, muchos países restringen severamente los derechos de las mujeres casadas: por ejemplo, en Yemen , las regulaciones matrimoniales establecen que una esposa debe obedecer a su esposo y no debe salir de casa sin su permiso. [96] En Irak, los esposos tienen el derecho legal de "castigar" a sus esposas. El código penal establece en el párrafo 41 que no hay delito si un acto se comete mientras se ejerce un derecho legal; ejemplos de derechos legales incluyen: "El castigo de una esposa por su marido, la disciplina por los padres y maestros de los niños bajo su autoridad dentro de ciertos límites prescritos por la ley o por la costumbre". [97] En Occidente, las mujeres casadas enfrentaron discriminación hasta hace solo unas décadas: por ejemplo, en Francia, las mujeres casadas recibieron el derecho a trabajar sin el permiso de su marido en 1965. [98] En España, durante la era de Franco, una mujer casada requería el consentimiento de su marido ( permiso marital ) para casi todas las actividades económicas, incluido el empleo, la propiedad de bienes y los viajes fuera de casa; el permiso marital fue abolido en 1975. [99] Existen preocupaciones sobre la violencia relacionada con el matrimonio, tanto dentro del matrimonio (abuso físico, violencia sexual, restricción de la libertad) como en relación con las costumbres matrimoniales ( dote , precio de la novia , matrimonio forzado , matrimonio infantil , matrimonio por secuestro , violencia relacionada con la virginidad prematrimonial femenina ). Claudia Card, profesora de filosofía en la Universidad de Wisconsin-Madison, escribe: [100]

Las mujeres tienen más probabilidades de ser víctimas de alguien con quien tienen intimidad, lo que comúnmente se denomina " violencia de pareja " (VPI). Los casos de VPI no suelen denunciarse a la policía, por lo que a muchos expertos les resulta difícil estimar la verdadera magnitud del problema. [101] Aunque esta forma de violencia suele considerarse un problema en el contexto de las relaciones heterosexuales, también se da en las relaciones lésbicas, [102] las relaciones entre hijas y madres, las relaciones entre compañeras de piso y otras relaciones domésticas en las que participan dos mujeres. La violencia contra las mujeres en las relaciones lésbicas es casi tan común como la violencia contra las mujeres en las relaciones heterosexuales. [103]

Las mujeres tienen muchas más probabilidades que los hombres de ser asesinadas por su pareja. En Estados Unidos, en 2005, 1181 mujeres fueron asesinadas por sus parejas, en comparación con 329 hombres. [104] [105] Se estima que el 30% o más de las mujeres que ingresan en urgencias podrían ser víctimas de violencia doméstica.

[106] En Inglaterra y Gales, alrededor de 100 mujeres son asesinadas por sus parejas o ex parejas cada año, mientras que 21 hombres fueron asesinados en 2010. [107] En 2008, en Francia, 156 mujeres fueron asesinadas por su pareja íntima, en comparación con 27 hombres. [108] Según la OMS, a nivel mundial, hasta un 38% de los asesinatos de mujeres son cometidos por una pareja íntima. [109] Un informe de la ONU compilado a partir de una serie de estudios diferentes realizados en al menos 71 países encontró que la violencia doméstica contra las mujeres es más frecuente en Etiopía . [110] Un estudio de la Organización Panamericana de la Salud realizado en 12 países latinoamericanos encontró que la prevalencia más alta de violencia doméstica contra las mujeres se encuentra en Bolivia . [111] En Europa occidental, un país que ha recibido importantes críticas internacionales por la forma en que ha abordado legalmente el problema de la violencia contra las mujeres es Finlandia; Los autores señalan que un alto nivel de igualdad para las mujeres en la esfera pública (como en Finlandia) nunca debería equipararse con la igualdad en todos los demás aspectos de la vida de las mujeres. [112] [113] [114]

Los comités de planificación e investigación de la Asociación Estadounidense de Psiquiatría para el próximo DSM-5 (2013) han examinado una serie de nuevos trastornos relacionales , que incluyen el trastorno de conflicto marital sin violencia o el trastorno de abuso marital (trastorno de conflicto marital con violencia) . [115] : 164, 166 Las parejas con trastornos maritales a veces acuden a la atención clínica porque la pareja reconoce una insatisfacción de larga data con su matrimonio y acuden al clínico por iniciativa propia o son derivadas por un profesional de la salud astuto. En segundo lugar, existe violencia grave en el matrimonio que "generalmente es el marido que golpea a la esposa". [115] : 163 En estos casos, la sala de emergencias o una autoridad legal a menudo es la primera en notificar al clínico . Lo más importante es que la violencia marital "es un factor de riesgo importante de lesiones graves e incluso de muerte, y las mujeres en matrimonios violentos tienen un riesgo mucho mayor de sufrir lesiones graves o morir ( Consejo Asesor Nacional sobre Violencia contra la Mujer , 2000)". [115] : 166 Los autores de este estudio añaden: "Actualmente existe una considerable controversia sobre si la violencia marital entre hombres y mujeres se considera mejor como un reflejo de la psicopatología y el control masculinos o si existe una base empírica y una utilidad clínica para conceptualizar estos patrones como relacionales". [115] : 166

Las recomendaciones para los médicos que realizan un diagnóstico de trastorno de la relación conyugal deben incluir la evaluación de la violencia masculina real o "potencial" con la misma regularidad con la que evalúan el potencial de suicidio en pacientes deprimidos. Además, "los médicos no deben relajar su vigilancia después de que una esposa maltratada abandona a su marido, porque algunos datos sugieren que el período inmediatamente posterior a una separación marital es el período de mayor riesgo para las mujeres. Muchos hombres acechan y golpean a sus esposas en un esfuerzo por lograr que regresen o castigarlas por abandonarlas. Las evaluaciones iniciales del potencial de violencia en un matrimonio pueden complementarse con entrevistas y cuestionarios estandarizados, que han sido ayudas confiables y válidas para explorar la violencia marital de manera más sistemática". [115] : 166

Los autores concluyen con lo que llaman "información muy reciente" [115] : 167, 168 sobre la evolución de los matrimonios violentos, que sugiere que "con el tiempo, los malos tratos del marido pueden disminuir un poco, pero quizás porque ha logrado intimidar a su esposa. El riesgo de violencia sigue siendo fuerte en un matrimonio en el que ha sido una característica en el pasado. Por lo tanto, el tratamiento es esencial en este caso; el médico no puede limitarse a esperar y observar". [115] : 167, 168 La prioridad clínica más urgente es la protección de la esposa porque es ella la que corre más riesgo, y los médicos deben ser conscientes de que apoyar la asertividad de una esposa maltratada puede conducir a más palizas o incluso a la muerte. [115] : 167, 168

La violación conyugal o conyugal, que en el pasado era ampliamente tolerada o ignorada por la ley, ahora se considera ampliamente una violencia inaceptable contra la mujer, repudiada por las convenciones internacionales y cada vez más criminalizada. Aun así, en muchos países la violación conyugal sigue siendo legal o ilegal, pero es ampliamente tolerada y aceptada como una prerrogativa del marido. La criminalización de la violación conyugal es reciente, y se produjo durante las últimas décadas. La comprensión y las opiniones tradicionales sobre el matrimonio , la violación , la sexualidad , los roles de género y la autodeterminación comenzaron a ser cuestionadas en la mayoría de los países occidentales durante los años 1960 y 1970, lo que llevó a la posterior criminalización de la violación conyugal durante las décadas siguientes. Con algunas excepciones notables, fue durante los últimos 30 años que se promulgaron la mayoría de las leyes contra la violación conyugal. Algunos países de Escandinavia y del antiguo bloque comunista de Europa ilegalizaron la violación conyugal antes de 1970, pero la mayoría de los países occidentales la criminalizaron recién en los años 1980 y 1990. En muchas partes del mundo las leyes contra la violación conyugal son muy nuevas, pues se promulgaron en la década de 2000. [116]

En Canadá, la violación conyugal se volvió ilegal en 1983, cuando se realizaron varios cambios legales, incluyendo cambiar el estatuto de violación a agresión sexual y hacer que las leyes fueran neutrales en cuanto al género. [117] [118] [119] En Irlanda, la violación conyugal fue ilegalizada en 1990. [120] En los EE. UU., la criminalización de la violación conyugal comenzó a mediados de la década de 1970, y en 1993, Carolina del Norte se convirtió en el último estado en ilegalizar la violación conyugal. [121] En Inglaterra y Gales , la violación conyugal se volvió ilegal en 1991. Las opiniones de Sir Matthew Hale, un jurista del siglo XVII, publicadas en The History of the Pleas of the Crown (1736), afirmaban que un marido no puede ser culpable de la violación de su esposa porque la esposa "se ha entregado de esta manera a su marido, de lo cual no puede retractarse"; En Inglaterra y Gales, esto seguiría siendo ley durante más de 250 años, hasta que fue abolido por el Comité de Apelaciones de la Cámara de los Lores , en el caso de R v. R en 1991. [122] En los Países Bajos, la violación conyugal también se volvió ilegal en 1991. [123] Uno de los últimos países occidentales en criminalizar la violación conyugal fue Alemania, en 1997. [124]

La relación entre algunas religiones ( cristianismo e islam ) y la violación marital es controvertida. La Biblia, en 1 Corintios 7:3-5, explica que uno tiene el "deber conyugal" de tener relaciones sexuales con su cónyuge (en clara oposición al sexo fuera del matrimonio , que se considera un pecado ) y afirma: "La mujer no tiene autoridad sobre su propio cuerpo, sino el marido. Y, asimismo, el marido no tiene autoridad sobre su propio cuerpo, sino la mujer. No os privéis el uno del otro". [125] Algunas figuras religiosas conservadoras interpretan esto como un rechazo a la posibilidad de violación marital. [126] El Islam también hace referencia a las relaciones sexuales en el matrimonio, en particular: "El Apóstol de Alá dijo: 'Si un marido llama a su mujer a su cama (es decir, para tener relaciones sexuales) y ella se niega y lo hace dormir enfadada, los ángeles la maldecirán hasta la mañana';" [127] y varios comentarios sobre el tema de la violación marital hechos por líderes religiosos musulmanes han sido criticados. [128] [129]

El abuso en el noviazgo, o violencia en el noviazgo, es la perpetración de coerción, intimidación o agresión en el contexto de una relación de noviazgo o cortejo . También se da cuando uno de los miembros de la pareja intenta mantener un poder y control abusivos . Los CDC definen la violencia en el noviazgo como "la violencia física, sexual, psicológica o emocional dentro de una relación de noviazgo, incluido el acecho". [130]

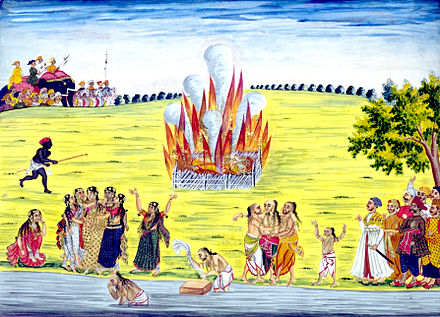

Las viudas han sido sometidas a un nuevo matrimonio forzado llamado herencia de viuda , donde se las obliga a casarse con un pariente masculino de su difunto marido. [131] Otra práctica es el nuevo matrimonio prohibido de las viudas, que es legal en la India [132] y Corea. [133] Una versión más extrema es el asesinato ritual de las viudas, como se ve en la India y Fiji. Sati es la quema de viudas, y aunque el sati en la India es hoy una práctica casi extinta, han ocurrido incidentes aislados en los últimos años, como el sati de 1987 de Roop Kanwar , así como varios incidentes en áreas rurales en 2002 [134] y 2006. [135] Una idea tradicional sostenida en algunos lugares de África es que una viuda soltera es impía y "perturbada" si no está casada y se abstiene de tener relaciones sexuales durante un período de tiempo. Esto alimenta la práctica de la purificación de las viudas, en la que se exige a la viuda soltera que tenga relaciones sexuales como una forma de purificación ritual, que comienza con una ceremonia para que el vecindario sea testigo de que ahora está purificada. [136]

Las viudas solteras tienen más probabilidades de ser acusadas y asesinadas como brujas . [137] [138] Los juicios por brujería en el período moderno temprano (entre los siglos XV y XVIII) eran comunes en Europa y en las colonias europeas en América del Norte. Hoy en día, quedan regiones del mundo (como partes del África subsahariana , el norte rural de la India y Papúa Nueva Guinea ) donde mucha gente cree en la brujería , y las mujeres acusadas de ser brujas son sometidas a una violencia grave. [139]

La preferencia por los hijos varones es una costumbre que prevalece en muchas sociedades [140] y que, en su grado extremo, puede llevar al rechazo de las hijas. El aborto selectivo por sexo de las niñas es más común entre la población de mayores ingresos, que puede acceder a la tecnología médica . Después del nacimiento, el descuido y la desviación de recursos hacia los hijos varones pueden llevar a que algunos países tengan una proporción sesgada con más niños que niñas, [140] y tales prácticas matan aproximadamente a 230.000 niñas menores de cinco años en la India cada año. [141] En China, la política de un solo hijo aumentó los abortos selectivos por sexo y fue en gran medida responsable de una proporción sexual desequilibrada. The Dying Rooms es un documental televisivo de 1995 sobre los orfanatos estatales chinos, que documentó cómo los padres abandonaban a sus niñas recién nacidas en orfanatos , donde el personal dejaba a las niñas en habitaciones para que murieran de sed o de hambre. [142] [143]

Otra manifestación de la preferencia por los hijos varones es la violencia infligida a las madres que dan a luz niñas. [144]

La mutilación genital femenina (MGF) es definida por la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) como “todos los procedimientos que implican la extirpación parcial o total de los genitales externos femeninos u otras lesiones a los órganos genitales femeninos por razones no médicas”. [146]

La OMS afirma: “El procedimiento no tiene ningún beneficio para la salud de las niñas y las mujeres” y “Los procedimientos pueden causar sangrado severo y problemas para orinar, y posteriormente quistes, infecciones, infertilidad y complicaciones en el parto aumentan el riesgo de muerte de los recién nacidos”. [146]

Según un informe de UNICEF de 2016, las tasas más altas de mutilación genital femenina se dan en Somalia (con un 98 por ciento de mujeres afectadas), Guinea (97 por ciento), Yibuti (93 por ciento), Egipto (87 por ciento), Eritrea (83 por ciento), Malí (89 por ciento), Sierra Leona (90 por ciento), Sudán (87 por ciento), Gambia (75 por ciento), Burkina Faso (76 por ciento), Etiopía (74 por ciento), Mauritania (69 por ciento), Liberia (50 por ciento) y Guinea-Bissau (45 por ciento). [147] Más de la mitad de los casos documentados por Unicef se concentran en solo tres países (Indonesia, Egipto y Etiopía). [148] [147]

La mutilación genital femenina está vinculada a ritos y costumbres culturales, incluidas las prácticas tradicionales y la religión. Sigue practicándose en diferentes comunidades de África y Oriente Medio, incluso en lugares donde está prohibida por la legislación nacional. Según un informe de UNICEF de 2016, al menos 200 millones de mujeres y niñas de África y Oriente Medio han sufrido la mutilación genital femenina. [147] Debido a la globalización y la inmigración, la mutilación genital femenina se está extendiendo más allá de las fronteras de África y Oriente Medio a países como Australia, Bélgica, Canadá, Francia, Nueva Zelanda, Estados Unidos y el Reino Unido. [149]

Aunque hoy en día la mutilación genital femenina se asocia a países en desarrollo, esta práctica era común hasta la década de 1970 también en algunas partes del mundo occidental. La mutilación genital femenina se consideró un procedimiento médico estándar en los Estados Unidos durante la mayor parte de los siglos XIX y XX. [150] Los médicos realizaban cirugías de diversa invasividad para tratar una serie de diagnósticos, entre ellos la histeria , la depresión , la ninfomanía y la frigidez . La medicalización de la mutilación genital femenina en los Estados Unidos permitió que estas prácticas continuaran hasta la segunda parte del siglo XX, con algunos procedimientos cubiertos por el seguro Blue Cross Blue Shield hasta 1977. [151] [150]

En África, desde 2016, la mutilación genital femenina está prohibida legalmente en Benín, Burkina Faso, Chad, Costa de Marfil, Egipto, Eritrea, Etiopía, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenia, Mauritania, Níger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sudáfrica, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda y Zambia. [152] El Convenio de Estambul prohíbe la mutilación genital femenina (artículo 38). [153]

El estiramiento de los labios , también conocido como elongación de los labios o tracción de los labios , es el acto de alargar los labios menores (los labios internos de los genitales femeninos) mediante manipulación manual (tracción) o equipo físico (como pesas). [154] A menudo lo realizan mujeres mayores a niñas. [155]

.jpg/440px-Bound_feet_(X-ray).jpg)

En China, vendar los pies era una práctica que se practicaba para reducir el tamaño de los pies de las niñas. Se consideraba una práctica más deseable y probablemente permitía un matrimonio más prestigioso. [156]

En algunos países, en particular Mauritania, se engorda a la fuerza a las niñas para prepararlas para el matrimonio, ya que la obesidad se considera deseable. Esta práctica de alimentación forzada se conoce como leblouh o gavage . [157] La práctica se remonta al siglo XI y se ha informado de que ha vuelto a cobrar importancia después de que una junta militar tomara el poder en el país en 2008. [ 158]

La "limpieza" sexual es una ceremonia en la que las niñas tienen relaciones sexuales como ritual de limpieza después de su primera menstruación [159] y se conoce como kusasa fumbi en algunas regiones de Malawi. [160] Las niñas prepúberes a menudo son enviadas a un campo de entrenamiento donde las mujeres conocidas como anamkungwi , o "líderes clave", les enseñan a cocinar, limpiar y tener relaciones sexuales para ser esposas. [161] Después del entrenamiento, un hombre conocido como hiena realiza la limpieza para mujeres de 12 a 17 años durante tres días y a veces se le pide a la niña que realice una danza con los pechos desnudos, conocida como chisamba , para señalar el final de su iniciación frente a la comunidad. [162]

Los crímenes de honor son una forma común de violencia contra las mujeres en ciertas partes del mundo. Los crímenes de honor son perpetrados por miembros de la familia (generalmente esposos, padres, tíos o hermanos) contra mujeres de la familia que se cree que han deshonrado a la familia. Se cree que la muerte de la mujer deshonrosa restaura el honor. [163] Estos asesinatos son una práctica tradicional [ ¿dónde? ] que se cree que se originó en las costumbres tribales donde una acusación contra una mujer puede ser suficiente para manchar la reputación de una familia. [164] [165] Las mujeres son asesinadas por razones como negarse a entrar en un matrimonio concertado , estar en una relación que es desaprobada por sus familiares, intentar dejar un matrimonio, tener relaciones sexuales fuera del matrimonio, convertirse en víctima de violación y vestirse de formas que se consideran inapropiadas, entre otras. [164] [166] En culturas donde la virginidad femenina es muy valorada y se considera obligatoria antes del matrimonio, en casos extremos, las víctimas de violación son asesinadas en crímenes de honor . Las víctimas también pueden verse obligadas por sus familias a casarse con el violador para restaurar el "honor" de la familia. [167] En el Líbano, en diciembre de 2016 se lanzó la Campaña contra la Ley libanesa sobre violación - Artículo 522 para abolir el artículo que permitía a un violador escapar de la prisión casándose con su víctima. En Italia, antes de 1981, el Código Penal preveía circunstancias atenuantes en caso de asesinato de una mujer o su pareja sexual por razones relacionadas con el honor, previendo una pena reducida. [168] [169]

Los crímenes de honor son comunes en países como Afganistán, Egipto, Irak, Jordania, Líbano, Libia, Marruecos, Pakistán, Arabia Saudita, Siria, Turquía y Yemen. [166] [170] [171] [172] [173] Los crímenes de honor también ocurren en comunidades inmigrantes en Europa, Estados Unidos y Canadá. Aunque los crímenes de honor se asocian más a menudo con Oriente Medio y el sur de Asia, también ocurren en otras partes del mundo. [164] [174] En la India, los crímenes de honor ocurren en las regiones del norte del país, especialmente en los estados de Punjab, Haryana, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Himachal Pradesh y Madhya Pradesh. [175] [176] En Turquía, los crímenes de honor son un problema grave en el sudeste de Anatolia. [177] [178]

La violencia obstétrica se refiere a actos categorizados como física o psicológicamente violentos en el contexto del parto y el nacimiento. A veces se puede obligar a una mujer embarazada a aceptar intervenciones quirúrgicas que se realizan sin su consentimiento. [180] [181] Esto podría incluir el " punto del marido ", en el que se utilizan una o más suturas adicionales a las necesarias para reparar el perineo de una mujer después de que se ha desgarrado o cortado durante el parto con la intención de apretar la abertura de la vagina y, de ese modo, aumentar el placer de su pareja sexual masculina durante el coito con penetración. Varios países latinoamericanos tienen leyes para proteger contra la violencia obstétrica. [182] La coerción reproductiva es un conjunto de comportamientos que interfieren en la toma de decisiones relacionadas con la salud reproductiva . [183] Según la OMS, "la discriminación en los entornos de atención de la salud adopta muchas formas y a menudo se manifiesta cuando a una persona o un grupo se le niega el acceso a servicios de atención de la salud que de otro modo estarían disponibles para otros. También puede ocurrir a través de la negación de servicios que solo necesitan ciertos grupos, como las mujeres". [184]

En algunas culturas, las mujeres se ven obligadas a vivir en aislamiento social durante sus períodos menstruales . En algunas partes de Nepal, por ejemplo, se las obliga a vivir en cobertizos, se les prohíbe tocar a los hombres o incluso entrar en el patio de sus propias casas, y se les prohíbe consumir leche, yogur, mantequilla, carne y otros alimentos por temor a que contaminen esos productos. Hay mujeres que han muerto durante este período debido al hambre, el mal tiempo o las mordeduras de serpientes. [185] En las culturas en las que las mujeres tienen prohibido estar en lugares públicos, por ley o por costumbre, las mujeres que violan esas restricciones a menudo se enfrentan a la violencia. [186]

El embarazo forzado es la práctica de obligar a una mujer o niña a quedarse embarazada . Una motivación común para esto es ayudar a establecer un matrimonio forzado , incluso mediante el rapto de la novia . Esto también se utilizó como parte de un programa de cría de esclavos (véase Cría de esclavos en los Estados Unidos ). En el siglo XX, el matrimonio forzado ordenado por el estado con el objetivo de aumentar la población fue practicado por algunos gobiernos autoritarios, en particular durante el régimen de los Jemeres Rojos en Camboya , que sistemáticamente obligaba a las personas a casarse y les ordenaba tener hijos, con el fin de aumentar la población y continuar la revolución. [187]

Algunas organizaciones también consideran que la continuación forzada del embarazo (es decir, negar a la mujer un aborto legal y seguro) constituye una violación de los derechos de la mujer. Por ejemplo, el Comité para la Eliminación de la Discriminación contra la Mujer considera que la penalización del aborto constituye una "violación de la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos de la mujer" y una forma de "violencia de género". [188]

Además, en algunas partes de América Latina, con leyes antiabortistas muy estrictas, las mujeres embarazadas evitan el sistema médico por temor a ser investigadas por las autoridades si sufren un aborto espontáneo, un parto de feto muerto u otros problemas con el embarazo. El procesamiento de estas mujeres es bastante común en lugares como El Salvador . [189] [190] [191] [192]

La esterilización y el aborto forzados se consideran formas de violencia de género. [193] El Convenio de Estambul prohíbe el aborto y la esterilización forzados (artículo 39). [194] Según la Convención sobre la eliminación de todas las formas de discriminación contra la mujer, "se garantiza a todas las mujeres el derecho a decidir libre y responsablemente el número y el espaciamiento de sus hijos y a tener acceso a la información, la educación y los medios que les permitan ejercer estos derechos". [195]

Los estudios muestran que las esterilizaciones forzadas a menudo se dirigen a grupos social y políticamente desfavorecidos, como las minorías raciales y étnicas, los pobres y las poblaciones indígenas. [196] En los Estados Unidos, gran parte de la historia de la esterilización forzada está relacionada con el legado de la eugenesia y el racismo en los Estados Unidos . [196] Muchos médicos pensaron que le estaban haciendo un servicio al país al esterilizar a mujeres pobres, discapacitadas o pertenecientes a minorías; los médicos consideraban que esas mujeres eran una carga para el sistema. [196] [197] Las mujeres nativas americanas , mexicoamericanas , afroamericanas y puertorriqueñas-americanas fueron obligadas a participar en programas de esterilización, y las nativas americanas y afroamericanas fueron especialmente el objetivo. [196] Los registros han demostrado que a niñas nativas americanas de tan solo once años se les realizaron operaciones de histerectomía . [198]

En Europa, se han presentado numerosas demandas y acusaciones contra la República Checa y Eslovaquia por esterilizar a mujeres gitanas sin la información adecuada ni un período de espera. [199] En respuesta, ambas naciones han instituido un período de espera obligatorio de siete días y un consentimiento escrito. Eslovaquia ha sido condenada varias veces por el Tribunal Europeo de Derechos Humanos por la cuestión de la esterilización forzada de mujeres gitanas (véase VC vs. Eslovaquia , NB vs. Eslovaquia e IG y otros vs. Eslovaquia ). [200]

En Perú , en 1995, Alberto Fujimori lanzó una iniciativa de planificación familiar dirigida especialmente a las mujeres pobres e indígenas. En total, se esterilizó a más de 215.000 mujeres, y se cree que más de 200.000 fueron sometidas a coacción. [201] En 2002, el Ministro de Salud Fernando Carbone admitió que el gobierno había dado información engañosa, ofrecido incentivos alimentarios y amenazado con multar a los padres si tenían más hijos. También se ha descubierto que los procedimientos fueron negligentes, ya que menos de la mitad de ellos utilizaron anestesia adecuada. [202]

En China, la política de hijo único incluía abortos forzados y esterilizaciones forzadas. [203] La esterilización forzada también se practica en Uzbekistán. [204] [205]

En Irán , desde 1981, después de la Revolución Islámica , todas las mujeres deben llevar ropa holgada y un pañuelo en la cabeza en público. [206] [207] En 1983, la Asamblea Consultiva Islámica decidió que las mujeres que no se cubran el cabello en público serán castigadas con 74 latigazos. Desde 1995, las mujeres sin velo también pueden ser encarceladas hasta por 60 días. [208] Las protestas iraníes contra el hijab obligatorio continuaron hasta las protestas iraníes de septiembre de 2022 que se desencadenaron en respuesta al asesinato de Mahsa Amini , quien supuestamente fue golpeada hasta la muerte por la policía debido a que usaba un "hiyab inadecuado". En Arabia Saudita , después de la toma de la Gran Mezquita de 1979, se volvió obligatorio que las mujeres se cubrieran el rostro en público [209], pero esto ya no fue requerido desde 2018. [210] En Afganistán, desde mayo de 2022, las mujeres deben usar un hijab y cubrirse el rostro en público. [211] En países donde no es obligatorio el uso del hijab, las mujeres pueden enfrentar acoso y ser culpadas por no llevarlo . [ 212]

El hijab ha sido prohibido en lugares como Austria, [213] Yugoslavia, [214] Kosovo, [215] Kazajstán, [216] la Unión Soviética, [217] y Túnez. [218] El 8 de enero de 1936, [219] Reza Shah emitió un decreto, Kashf-e hijab , que prohibía todos los velos. [207] Para hacer cumplir este decreto, se ordenó a la policía que quitara físicamente el velo a cualquier mujer que lo usara en público. Las mujeres que se negaban eran golpeadas, se les arrancaban los pañuelos y chadores y se registraban sus casas a la fuerza. [220]

En muchas partes del mundo, la libertad de movimiento de las mujeres está severamente restringida . La libertad de movimiento es un derecho esencial, reconocido por instrumentos internacionales, incluido el artículo 15 (4) de la CEDAW . [221] Sin embargo, en algunos países, a las mujeres no se les permite legalmente salir de casa sin un tutor masculino (un pariente masculino o su marido). [222] Arabia Saudita fue el único país del mundo donde a las mujeres se les prohibió conducir vehículos de motor hasta junio de 2018. [223]

Los delitos sexuales como el adulterio y las relaciones sexuales fuera del matrimonio se aplican desproporcionadamente contra las mujeres y el castigo suele ser la lapidación y la flagelación . Esto se ha visto en Irán, Arabia Saudita, Sudán, Pakistán, Yemen, los Emiratos Árabes Unidos y algunos estados de Nigeria. [224] Además, esto puede disuadir a las víctimas de violencia sexual de denunciar el delito, porque las propias víctimas pueden ser castigadas (si no pueden probar su caso, si se considera que estuvieron en compañía de un hombre no emparentado o si no estaban casadas ni eran vírgenes en el momento de la violación). [225] [226] Otro aspecto es la negación de atención médica que a menudo ocurre con respecto a la salud reproductiva y sexual. A veces, las propias mujeres evitan el sistema médico por miedo a ser denunciadas a la policía o enfrentarse a la violencia familiar debido a tener relaciones sexuales prematrimoniales o ser víctimas de violencia sexual . [227]

.jpg/440px-End_Slut_Shaming_(6201500323).jpg)

La violencia contra las mujeres en la política (VAWP) es el acto o amenaza de violencia física, emocional o psicológica contra las mujeres políticas por su género , con mayor frecuencia con la intención de disuadir a las víctimas y a otras mujeres políticas de participar en el proceso político. La VAWP ha ido ganando importancia en los campos de la ciencia política de género y los estudios de teoría política feminista. La intención principal detrás de la creación de una categoría separada que sea distinta de la violencia contra las mujeres es destacar las barreras que enfrentan las mujeres que trabajan en política o desean seguir una carrera en el ámbito político. La VAWP es única de la violencia contra las mujeres en tres formas importantes: las víctimas son atacadas por su género; la violencia en sí puede ser de género (es decir, sexismo, violencia sexual); el objetivo principal es disuadir a las mujeres de participar en la política (incluyendo, entre otros, votar, postularse para un cargo, hacer campaña, etc.). [228] También es importante distinguir la VAWP de la violencia política , que se define por el uso o amenazas de fuerza para alcanzar fines políticos, y puede ser experimentada por todos los políticos. [229]

Si bien la participación de las mujeres en los parlamentos nacionales ha ido aumentando, pasando del 11% en 1995 al 26,5% en 2023, todavía existe una gran disparidad entre la representación masculina y femenina en la política gubernamental. [230] Ampliar la participación de las mujeres en el gobierno es un objetivo crucial para muchos países, ya que las mujeres políticas han demostrado ser invaluables con respecto a llevar ciertas cuestiones al primer plano, como la eliminación de la violencia de género, la licencia parental y el cuidado de los niños, las pensiones, las leyes de igualdad de género, la reforma electoral y la provisión de nuevas perspectivas en numerosas áreas de políticas que típicamente han permanecido en un ámbito dominado por los hombres. [230] Para aumentar la participación de las mujeres de manera efectiva, no se puede subestimar la importancia de reconocer las cuestiones relacionadas con la violencia contra las mujeres en la política y hacer todos los esfuerzos posibles para proporcionar los recursos necesarios a las víctimas y condenar cualquier comportamiento hostil en las instituciones políticas. Experimentar la VCMP puede disuadir a las mujeres de permanecer en la política (y llevarlas a abandonar prematuramente su carrera o a aspirar a un cargo político más alto). Ser testigo de cómo las mujeres en la política experimentan la VCMP puede servir como uno de los muchos elementos disuasorios para que las aspirantes se postulen a un cargo y para que los candidatos sigan haciendo campaña. [229]

Los actos de violencia o acoso a menudo no se consideran relacionados con el género cuando se denuncian, si es que se denuncian. La VCMP se suele desestimar como "el costo de hacer política" y la denuncia puede verse como un "suicidio político", lo que contribuye a la normalización de la VCMP. [229] Esta ambigüedad da lugar a una falta de información sobre los ataques y hace que el problema parezca relativamente común. Si bien se informa de que las mujeres en política son más a menudo objeto de violencia que sus homólogos masculinos, [231] la causa específica a menudo no se denuncia como un delito relacionado con el género. Esto hace que sea más difícil determinar dónde están realmente los vínculos entre la violencia específica de género y la violencia política. En muchos países, la práctica de la política electoral se considera tradicionalmente un ámbito masculino . [232]

La historia de una política dominada por los hombres ha permitido que algunos políticos hombres crean que tienen derecho a participar en la política mientras que las mujeres no deberían hacerlo, ya que la participación de las mujeres es una amenaza para el orden social. Por lo tanto, las mujeres que ocupan puestos de poder tienen más probabilidades que sus homólogos masculinos de recibir amenazas y sufrir violencia. Como escribió una profesora de sociología, Marie E. Berry: "cuando se capacita y anima a las mujeres a competir por esos escaños, corren el riesgo de apropiarse de un poder (y de recursos) que los políticos hombres consideran que les corresponde por derecho, lo que las expone al riesgo de la violencia y de otros intentos de limitar la eficacia de sus campañas". [233] [234]

El 48% de la violencia electoral contra las mujeres se ejerce contra sus simpatizantes, lo que probablemente sea el porcentaje más alto, ya que es donde participa la mayor cantidad de público. El 9% de la violencia electoral contra las mujeres se dirige a los candidatos, mientras que el 22% se dirige a las mujeres votantes. Esto significa que las mujeres que actúan directamente en la política tienen más probabilidades de enfrentarse a algún tipo de violencia, ya sea física o emocional. [235] En cuanto a la violencia contra las mujeres políticas, las mujeres más jóvenes y aquellas con identidades interseccionales , en particular las minorías raciales y étnicas, tienen más probabilidades de ser víctimas. Las mujeres políticas que se expresan y actúan abiertamente desde perspectivas feministas también tienen más probabilidades de ser víctimas. [229]

El informe de 2011 de Gabrielle Bardell: "Rompiendo moldes: Entendiendo la violencia de género y electoral" fue uno de los primeros documentos publicados que mostraba ejemplos y cifras de cómo las mujeres son intimidadas y atacadas en la política. [235] Desde el informe de Bardall, otros académicos han llevado a cabo más investigaciones sobre el tema. Cabe destacar que el trabajo de Mona Lena Krook sobre la VCMP introdujo cinco formas de violencia y acoso: física, sexual, psicológica, económica y semiótica/simbólica. La violencia física abarca infligir, o intentar infligir, daño y lesión corporal. [229] [236] Si bien la violencia física es la forma más fácil de identificar, en realidad es el tipo menos común. [229] La violencia sexual implica (intentos de) actos sexuales mediante coerción, incluidos comentarios sexuales no deseados, insinuaciones y acoso. [229] [236] La violencia psicológica incluye causar daño emocional y mental a través de amenazas de muerte/violación, acecho, etc. [229] [236] La violencia económica implica negar, retener y controlar el acceso de las mujeres políticas a los recursos financieros, particularmente en lo que respecta a las campañas. [229] [236] La violencia semiótica o simbólica, el subtipo más abstracto de la VCMP, se refiere al borrado de las mujeres políticas a través de imágenes degradantes y lenguaje sexista. [229] [236] [237] Krook teoriza que la violencia semiótica contra las mujeres en la política funciona de dos maneras relacionadas: volviendo invisibles a las mujeres y volviéndolas incompetentes. Al eliminar simbólicamente a las mujeres de la esfera política pública, la violencia semiótica las vuelve invisibles. Los ejemplos incluyen el uso de gramática masculina cuando se habla sobre y a las mujeres políticas, interrumpir a las mujeres políticas y no retratar a las mujeres políticas en los medios. Al destacar la incongruencia de roles entre los atributos estereotípicamente femeninos (por ejemplo, cálida, educada, sumisa) y los rasgos típicamente atribuidos a los buenos líderes (por ejemplo, fuerte, poderosa, asertiva), la violencia semiótica enfatiza que las mujeres son incompetentes para ser actores políticos. [237] Esta forma de violencia semiótica puede manifestarse a través de la negación y minimización de las calificaciones políticas de las mujeres, la cosificación sexual y el etiquetado de las mujeres políticas como emocionales, entre otras acciones. [237]

La violencia sexual en los campus universitarios se considera un problema importante en los Estados Unidos. Según la conclusión de un importante estudio sobre agresiones sexuales en los campus: "Los datos del estudio sugieren que las mujeres en las universidades corren un riesgo considerable de sufrir agresiones sexuales". [238]

La violencia contra las mujeres en el deporte es cualquier acto físico, sexual o mental que sea "perpetrado tanto por deportistas masculinos como por aficionados o consumidores masculinos del deporte y de los acontecimientos deportivos, así como por entrenadores de deportistas femeninas". [239] Los informes y la bibliografía que lo documentan sugieren que existen conexiones obvias entre el deporte contemporáneo y la violencia contra las mujeres. Eventos como la Copa del Mundo de 2010 , los Juegos Olímpicos y los Juegos de la Commonwealth "han puesto de relieve las conexiones entre el hecho de ser espectadores de un deporte y la violencia de pareja, y la necesidad de que la policía, las autoridades y los servicios sean conscientes de ello al planificar acontecimientos deportivos". [239] La violencia relacionada con el deporte se produce en diversos contextos y lugares, incluidos los hogares, los bares, los clubes, las habitaciones de hotel y las calles. [239]

La violencia contra las mujeres es un tema de preocupación en la comunidad atlética universitaria de los Estados Unidos. Desde el asesinato de un jugador de lacrosse de la UVA en 2010, en el que un atleta masculino fue acusado de asesinato en segundo grado de su novia, hasta el escándalo de fútbol de la Universidad de Colorado en 2004, cuando los jugadores fueron acusados de nueve presuntas agresiones sexuales, [240] los estudios sugieren que los atletas tienen un mayor riesgo de cometer agresiones sexuales contra mujeres que el estudiante promedio. [241] [242] Se informa que una de cada tres agresiones universitarias son cometidas por atletas. [243] Las encuestas sugieren que los atletas estudiantes masculinos, que representan el 3,3% de la población universitaria, cometen el 19% de las agresiones sexuales denunciadas y el 35% de la violencia doméstica. [244] Las teorías que rodean estas estadísticas varían desde la tergiversación del estudiante-atleta hasta una mentalidad poco saludable hacia las mujeres dentro del propio equipo. [243] El sociólogo Timothy Curry, después de realizar un análisis observacional de las conversaciones en los vestuarios de dos grandes equipos deportivos, dedujo que el alto riesgo de abuso de género entre los estudiantes atletas varones es resultado de la subcultura del equipo. [245] Curry afirma: "Sus conversaciones en el vestuario generalmente trataban a las mujeres como objetos, alentaban actitudes sexistas hacia ellas y, en su forma más extrema, promovían la cultura de la violación". [245] Propone que esta cosificación es una forma del hombre de reafirmar su estatus heterosexual e hipermasculinidad. Se ha afirmado que la atmósfera cambia cuando un extraño (especialmente mujeres) se entromete en el vestuario. [246]

In the wake of the reporter Lisa Olson being harassed by a Patriots player in the locker room in 1990, she said, "We are taught to think we must have done something wrong and it took me a while to realize I hadn't done anything wrong."[246] Other female sports reporters (college and professional) have said that they often brush off the players' comments, which leads to further objectification.[246] Some sociologists challenge this assertion. Steve Chandler says that because of their celebrity status on campus, "athletes are more likely to be scrutinized or falsely accused than non-athletes."[242] Stephanie Mak says that "if one considers the 1998 estimates that about three million women were battered and almost one million raped, the proportion of incidences[spelling?] that involve athletes in comparison to the regular population is relatively small."[243]

In response to the proposed link between college athletes and gender-based violence, and media coverage holding universities as responsible for these scandals more universities are requiring athletes to attend workshops that promote awareness. For example, St. John's University holds sexual assault awareness classes in the fall for its incoming student athletes.[247] Other groups, such as the National Coalition Against Violent Athletes, have formed to provide support for the victims as their mission statement reads, "The NCAVA works to eliminate off the field violence by athletes through the implementation of prevention methods that recognize and promote the positive leadership potential of athletes within their communities. In order to eliminate violence, the NCAVA is dedicated to empowering individuals affected by athlete violence through comprehensive services including advocacy, education and counseling."[248]

A 1995 study of female war veterans found that 90 percent had been sexually harassed. A 2003 survey found that 30 percent of female vets said they were raped in the military and a 2004 study of veterans who were seeking help for post-traumatic stress disorder found that 71 percent of the women said they were sexually assaulted or raped while serving.[249]

In 2021, The New York Times reported that about one in four women in the military had experienced sexual assault.[250] Until the end of 2023, these reports went through the service member's chain-of-command, and many women reported that their reports were dismissed without due process and/or resulted in professional reprisal, ostracism, or other maltreatment.[251] Beginning in December 2023, however, sexual assault reports are handled outside of the chain-of-command, hopefully reducing biases in the process of investigation.[252]

Cyberbullying is a form of intimidation using electronic forms of contact. In the 21st century, cyberbullying has become increasingly common, especially among teenagers in Western countries.[253] Almost 75% of women have encountered harassment and threats of violence online, known as cyber violence, as reported by the United Nations Broadband Commission in 2015.[254] Misogynistic rhetoric is prevalent online, and the public debate over gender-based attacks has increased significantly, leading to calls for policy interventions and better responses by social networks like Facebook and Twitter.[255][256] Some specialists have argued that gendered online attacks should be given particular attention within the wider category of hate speech.[257] Abusers quickly identified opportunities online to humiliate their victims, destroy their careers, reputations and relationships, and even drive them to suicide or "trigger so-called 'honor' violence in societies where sex outside of marriage is seen as bringing shame on a family".[258]According to a poll conducted by Amnesty International in 2018 across 8 countries, 23% of women have experienced online abuse of harassment. These are often sexist or misogynistic in nature and include direct of indirect threats of physical or sexual violence, abuse targeting aspects of their personality and privacy violations.[259]According to Human Rights Watch, 90% of those who experienced sexual violence online in 2019 were women and girls.[258]

According to UNESCO,[260] women journalists in prominent and visible positions tend to attract more virulent abuse. In their survey of 901 journalists, nearly three quarters (73%) said they had experienced online violence.[261] In another survey by The Guardian that looked at comments received on articles, women writers were 4 times more likely to be abused compared to their male counterparts.[262] This is a trend that is persistent across geography - in the Netherlands, 82% of the 300 female journalists surveyed in 2022 said they encountered abuse online.[263]

Generative AI can lead to an increase in the number of attackers, the creation of sustained and automated attacks and the generation of content such as posts, texts, and emails that are written convincingly from multiple ‘voices’. This makes existing harms such as hate speech, cyber harassment, misinformation, and impersonation - all of which rank in the top five most common vectors of technology-facilitated gender-based violence - have a much wider reach and be more dangerous.[260]

According to an article published in the Health and Human Rights journal,[264] regardless of many years of advocacy and involvement of many feminist activist organizations, the issue of violence against women still "remains one of the most pervasive forms of human rights violations worldwide".[264]: 91 The violence against women can occur in both public and private spheres of life and at any time of their life span. Violence against women often keeps women from wholly contributing to social, economic, and political development of their communities.[264][265] Many women are terrified by these threats of violence and this essentially influences their lives so that they are impeded to exercise their human rights; for instance, they fear contributing to the development of their communities socially, economically, and politically.[265] Apart from that, the causes that trigger VAW or gender-based violence can go beyond just the issue of gender and into the issues of age, class, culture, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, and specific geographical area of their origins.[citation needed]

Most often, violence against women has been framed as a health issue, and also as a violation of human rights. The research seems to provide convincing evidence that violence against women is a severe and pervasive problem the world over, with devastating effects on the health and well-being of women and children.[266] Importantly, other than the issue of social divisions, gendered violence can also extend into the realm of health issues and become a direct concern of the public health sector.[267] A health issue such as HIV/AIDS is another cause that also leads to violence. Women who have HIV/AIDS infection are also among the targets of the violence.[264]: 91 The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that violence against women puts an undue burden on health care services, as women who have suffered violence are more likely to need health services and at higher cost, compared to women who have not suffered violence.[109] The Council of Europe describes violence against women in private sphere, at home or domestic violence, as the main reason of "death and disability" among the women who encountered violence.[264]: 91

In addition, several studies have shown a link between poor treatment of women and international violence. These studies show that one of the best predictors of inter- and intranational violence is the maltreatment of women in the society.[268][269]

Violence against women can be connected with victim blaming.[212]

According to the UN, "there is no region of the world, no country and no culture in which women's freedom from violence has been secured."[266] Several forms of violence are more prevalent in certain parts of the world, often in developing countries. For example, dowry violence and bride burning is associated with India, Bangladesh, and Nepal. Acid throwing is also associated with these countries, as well as in Southeast Asia, including Cambodia. Honor killing is associated with the Middle East and South Asia. Female genital mutilation is found mostly in Africa, and to a lesser extent in the Middle East and some other parts of Asia. Marriage by abduction is found in Ethiopia, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. Abuse related to payment of bride price (such as violence, trafficking, and forced marriage) is linked to parts of Sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania (also see Lobolo).[270][271]

A study in 2002 estimated that at least one in five women in the world had been physically or sexually abused by a man sometime in their lives, and "gender-based violence accounts for as much death and ill-health in women aged 15–44 years as cancer, and is a greater cause of ill-health than malaria and traffic accidents combined."[272]

A 2007 survey by the National Institute of Justice found that 19.0% of college women and 6.1% of college men experienced either sexual assault or attempted sexual assault since entering college.[273] In the University of Pennsylvania Law Review in 2017, D. Tuerkheimer reviewed the literature on rape allegations, and reported on the problems surrounding the credibility of rape victims, and how that relates to false rape accusations. She pointed to national survey data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicates 1 in every 5 women (and 1 in 71 men) will be raped during their lifetime at some point. Despite the prevalence of rape and the fact that false rape allegations are rare, Tuerkheimer reported that law enforcement officers often default to disbelief about an alleged rape. This documented prejudice leads to reduced investigation and criminal justice outcomes that are faulty compared to other crimes. Tuerkheimer says that women face "credibility discounts" at all stages of the justice system, including from police, jurors, judges, and prosecutors. These credibility discounts are especially pronounced when the victim is acquainted with the accuser, and the vast majority of rapes fall into this category.[274] The U.S. Department of Justice estimated from 2005 to 2007 that about 2% of victims who were raped while incapacitated (from drugs, alcohol, or other reasons) reported the rape to the police, compared to 13% of victims who experienced physically forced sexual assault.[273]

Many kinds of violence against women (specifically rape, sexual assault, and domestic violence) are under-reported, often due to societal norms, taboos, stigma, and the sensitive nature of the subject.[275][276] It is widely recognized that even today, a lack of reliable and continuous data is an obstacle to forming a clear picture of violence against women.[266]

Acts of violence against women are often not unique episodes, but are ongoing over time. More often than not, the violence is perpetrated by someone the woman knows, not by a stranger.[276]

Indigenous women are often targets of physical violence, including sexual assault. Many indigenous communities are rural, with few resources and little help from the government or non-state actors. They often have strained relationships with law enforcement, making prosecution difficult. Many indigenous societies find themselves at the center of land disputes between nations and ethnic groups, resulting in these communities sometimes bearing the brunt of national and ethnic conflicts.[277]

Violence is often perpetrated by the state, such as in Peru, in the 1990s. President Alberto Fujimori has been accused of genocide and crimes against humanity as a result of a forced sterilization program.[278] Fujimori put in place a program against indigenous people (mainly the Quechuas and the Aymaras), in the name of a "public health plan", in 1995.[citation needed]

Many countries have higher rates of violence against indigenous women] than non‐indigenous women. This includes Bolivia,[279] which has the highest rate of domestic violence in Latin America;[280][281] and Canada,[282] which violence against women falling, except for aboriginal populations.[283] Guatemalan indigenous women have faced extensive violence. Throughout three decades of conflict, Maya women and girls have continued to be targeted.[citation needed] The Commission for Historical Clarification found 88% of women affected by state-sponsored rape and sexual violence were indigenous.[citation needed]

The concept of white dominion over indigenous women's bodies has been rooted in American history since the beginning of colonization. The theory of Manifest destiny went beyond simple land extension and into the belief that European settlers had the right to exploit Native women's bodies as a method of taming and "humanizing" them.[283][284] In the US, Native American women are more than twice as likely to experience violence than any other demographic.[283] One in three Native women is sexually assaulted, and 67% of these assaults are perpetrated by non-Natives,[285][283][286] with Native Americans constituting 0.7% of U.S. population in 2015.[287] The disproportionate rate of assault is due to a variety of causes, including the historical legal inability of tribes to prosecute on their own on the reservation. The federal Violence Against Women Act was reauthorized in 2013, which for the first time gave tribes jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute felony domestic violence offenses involving Native American and non-Native offenders on the reservation,[288] as 26% of Natives live on reservations.[289][290] In 2019 the Democrat House passed the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019, which increased tribes' prosecution rights further. However, in the Republican Senate its progress stalled.[291]