La Revolución Industrial , a veces dividida en la Primera Revolución Industrial y la Segunda Revolución Industrial , fue un período de transición global de la economía humana hacia procesos de fabricación más generalizados, eficientes y estables que sucedieron a la Revolución Agrícola . Comenzó en Gran Bretaña y se extendió a Europa continental y Estados Unidos , desde alrededor de 1760 hasta aproximadamente 1820-1840. [1] Esta transición incluyó pasar de métodos de producción manuales a máquinas ; nuevos procesos de fabricación química y producción de hierro ; el uso creciente de la energía hidráulica y de vapor ; el desarrollo de máquinas herramienta ; y el surgimiento del sistema de fábrica mecanizada . La producción aumentó enormemente y el resultado fue un aumento sin precedentes de la población y la tasa de crecimiento de la población . La industria textil fue la primera en utilizar métodos de producción modernos, [2] : 40 y los textiles se convirtieron en la industria dominante en términos de empleo, valor de la producción y capital invertido.

Muchas de las innovaciones tecnológicas y arquitectónicas fueron de origen británico. [3] [4] A mediados del siglo XVIII, Gran Bretaña era la principal nación comercial del mundo, [5] controlando un imperio comercial global con colonias en América del Norte y el Caribe. Gran Bretaña tenía una importante hegemonía militar y política en el subcontinente indio ; particularmente con la Bengala mogol protoindustrializada , a través de las actividades de la Compañía de las Indias Orientales . [6] [7] [8] [9] El desarrollo del comercio y el auge de los negocios estuvieron entre las principales causas de la Revolución Industrial. [2] : 15 Los avances en la ley también facilitaron la revolución, como los tribunales que fallaron a favor de los derechos de propiedad . Un espíritu emprendedor y una revolución del consumo ayudaron a impulsar la industrialización en Gran Bretaña, que después de 1800, fue emulada en Bélgica, Estados Unidos y Francia. [10]

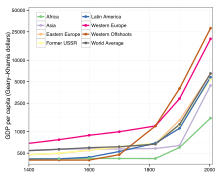

La Revolución Industrial marcó un punto de inflexión importante en la historia, comparable sólo a la adopción de la agricultura por parte de la humanidad en lo que respecta al avance material. [11] La Revolución Industrial influyó de alguna manera en casi todos los aspectos de la vida diaria. En particular, el ingreso promedio y la población comenzaron a exhibir un crecimiento sostenido sin precedentes. Algunos economistas han dicho que el efecto más importante de la Revolución Industrial fue que el nivel de vida de la población general en el mundo occidental comenzó a aumentar de manera constante por primera vez en la historia, aunque otros han dicho que no comenzó a mejorar significativamente hasta finales del siglo XIX y el siglo XX. [12] [13] [14] El PIB per cápita era en general estable antes de la Revolución Industrial y el surgimiento de la economía capitalista moderna, [15] mientras que la Revolución Industrial inició una era de crecimiento económico per cápita en las economías capitalistas. [16] Los historiadores económicos coinciden en que el inicio de la Revolución Industrial es el evento más importante en la historia humana desde la domesticación de animales y plantas. [17]

El inicio y el final precisos de la Revolución Industrial aún son objeto de debate entre los historiadores, al igual que el ritmo de los cambios económicos y sociales . [18] [19] [20] [21] Según el historiador de Cambridge Leigh Shaw-Taylor, Gran Bretaña ya se estaba industrializando en el siglo XVII, y "Nuestra base de datos muestra que una oleada de iniciativa y productividad transformó la economía en el siglo XVII, sentando las bases para la primera economía industrial del mundo. Gran Bretaña ya era una nación de creadores en el año 1700" y "la historia de Gran Bretaña necesita ser reescrita". [22] [23] Eric Hobsbawm sostuvo que la Revolución Industrial comenzó en Gran Bretaña en la década de 1780 y no se sintió plenamente hasta la década de 1830 o 1840, [18] mientras que TS Ashton sostuvo que ocurrió aproximadamente entre 1760 y 1830. [19] La rápida adopción de la hilatura textil mecanizada ocurrió en Gran Bretaña en la década de 1780, [24] y altas tasas de crecimiento en la energía de vapor y la producción de hierro ocurrieron después de 1800. La producción textil mecanizada se extendió desde Gran Bretaña a Europa continental y Estados Unidos a principios del siglo XIX, con importantes centros de textiles, hierro y carbón surgiendo en Bélgica y Estados Unidos y más tarde textiles en Francia. [2]

Desde finales de la década de 1830 hasta principios de la de 1840 se produjo una recesión económica, cuando la adopción de las primeras innovaciones de la Revolución Industrial, como el hilado y el tejido mecanizados, se desaceleró a medida que maduraban sus mercados; y a pesar de la creciente adopción de locomotoras, barcos de vapor y buques de vapor, y fundición de hierro con chorro de aire caliente . Las nuevas tecnologías, como el telégrafo eléctrico , ampliamente introducido en las décadas de 1840 y 1850 en el Reino Unido y los Estados Unidos, no fueron lo suficientemente potentes como para impulsar altas tasas de crecimiento económico.

El rápido crecimiento económico comenzó a repetirse después de 1870, a partir de un nuevo grupo de innovaciones en lo que se ha llamado la Segunda Revolución Industrial . Estas incluyeron nuevos procesos de fabricación de acero , producción en masa , líneas de montaje , sistemas de redes eléctricas , la fabricación a gran escala de máquinas herramienta y el uso de maquinaria cada vez más avanzada en fábricas impulsadas por vapor. [2] [25] [26] [27]

El primer uso registrado del término "Revolución industrial" fue en julio de 1799 por el enviado francés Louis-Guillaume Otto , anunciando que Francia había entrado en la carrera hacia la industrialización. [28] En su libro de 1976 Palabras clave: un vocabulario de cultura y sociedad , Raymond Williams afirma en la entrada de "Industria": "La idea de un nuevo orden social basado en un gran cambio industrial fue clara en Southey y Owen , entre 1811 y 1818, y estaba implícita ya en Blake a principios de la década de 1790 y Wordsworth a principios del siglo [XIX]". El término Revolución industrial aplicado al cambio tecnológico se estaba volviendo más común a fines de la década de 1830, como en la descripción de Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui en 1837 de la révolution industrielle . [29]

En su libro La situación de la clase obrera en Inglaterra, Friedrich Engels habló de «una revolución industrial, una revolución que al mismo tiempo cambió toda la sociedad civil». Aunque Engels escribió su libro en la década de 1840, no fue traducido al inglés hasta finales del siglo XIX, y su expresión no entró en el lenguaje cotidiano hasta entonces. El mérito de popularizar el término puede atribuirse a Arnold Toynbee , cuyas conferencias de 1881 dieron una explicación detallada del término. [30]

Historiadores económicos y autores como Mendels, Pomeranz y Kridte sostienen que la protoindustrialización en partes de Europa, el mundo musulmán , la India mogol y China creó las condiciones sociales y económicas que llevaron a la Revolución Industrial, causando así la Gran Divergencia . [31] [32] [33] Algunos historiadores, como John Clapham y Nicholas Crafts , han argumentado que los cambios económicos y sociales ocurrieron gradualmente y que el término revolución es un nombre inapropiado. Esto todavía es un tema de debate entre algunos historiadores. [34]

Seis factores facilitaron la industrialización: altos niveles de productividad agrícola, como los reflejados en la Revolución Agrícola Británica , para proporcionar un exceso de mano de obra y alimentos; un conjunto de habilidades gerenciales y empresariales; puertos, ríos, canales y carreteras disponibles para transportar materias primas y productos de manera barata; recursos naturales como carbón, hierro y cascadas; estabilidad política y un sistema legal que apoyaba a las empresas; y capital financiero disponible para invertir. Una vez que comenzó la industrialización en Gran Bretaña, se pueden agregar nuevos factores: el afán de los empresarios británicos de exportar experiencia industrial y la voluntad de importar el proceso. Gran Bretaña cumplió con los criterios y se industrializó a partir del siglo XVIII, y luego exportó el proceso a Europa occidental (especialmente Bélgica, Francia y los estados alemanes) a principios del siglo XIX. Estados Unidos copió el modelo británico a principios del siglo XIX, y Japón copió los modelos de Europa occidental a fines del siglo XIX. [35] [36]

El comienzo de la Revolución Industrial está estrechamente vinculado a un pequeño número de innovaciones, [37] que comenzaron en la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII. En la década de 1830, se habían logrado los siguientes avances en tecnologías importantes:

En 1750, Gran Bretaña importó 2,5 millones de libras de algodón crudo, la mayor parte del cual fue hilado y tejido por la industria casera en Lancashire . El trabajo se hacía a mano en las casas de los trabajadores o, ocasionalmente, en los talleres de los maestros tejedores. Los salarios en Lancashire eran aproximadamente seis veces mayores que los de la India en 1770, cuando la productividad general en Gran Bretaña era aproximadamente tres veces mayor que en la India. [44] En 1787, el consumo de algodón crudo era de 22 millones de libras, la mayor parte del cual se limpiaba, cardaba e hilaba en máquinas. [2] : 41–42 La industria textil británica utilizó 52 millones de libras de algodón en 1800, que aumentaron a 588 millones de libras en 1850. [45]

La participación del valor agregado por la industria textil del algodón en Gran Bretaña fue del 2,6% en 1760, del 17% en 1801 y del 22,4% en 1831. El valor agregado por la industria británica de la lana fue del 14,1% en 1801. Las fábricas de algodón en Gran Bretaña sumaban aproximadamente 900 en 1797. En 1760, aproximadamente un tercio de la tela de algodón fabricada en Gran Bretaña se exportaba, cifra que aumentó a dos tercios en 1800. En 1781, el algodón hilado ascendía a 5,1 millones de libras, cifra que aumentó a 56 millones de libras en 1800. En 1800, menos del 0,1% de la tela de algodón mundial se producía con maquinaria inventada en Gran Bretaña. En 1788, había 50.000 husos en Gran Bretaña, cifra que aumentó a 7 millones en los siguientes 30 años. [44]

Los primeros intentos europeos de mecanizar el hilado se hicieron con lana; sin embargo, el hilado de lana resultó más difícil de mecanizar que el de algodón. La mejora de la productividad en el hilado de lana durante la Revolución Industrial fue significativa, pero mucho menor que la del algodón. [2] [9]

Se podría decir que la primera fábrica altamente mecanizada fue la fábrica de seda impulsada por agua de John Lombe en Derby , que entró en funcionamiento en 1721. Lombe aprendió a fabricar hilo de seda al aceptar un trabajo en Italia y actuar como espía industrial; sin embargo, debido a que la industria de la seda italiana guardaba sus secretos celosamente, se desconoce el estado de la industria en ese momento. Aunque la fábrica de Lombe tuvo éxito técnico, se cortó el suministro de seda cruda de Italia para eliminar la competencia. Para promover la fabricación, la Corona pagó modelos de la maquinaria de Lombe que se exhibieron en la Torre de Londres . [46] [47]

Algunas partes de la India, China, América Central, América del Sur y Oriente Medio tienen una larga historia de fabricación artesanal de textiles de algodón, que se convirtió en una industria importante en algún momento después del año 1000 d. C. En las regiones tropicales y subtropicales donde se cultivaba, la mayor parte lo cultivaban pequeños agricultores junto con sus cultivos alimentarios y se hilaba y tejía en los hogares, principalmente para el consumo doméstico. En el siglo XV, China comenzó a exigir a los hogares que pagaran parte de sus impuestos en tela de algodón. En el siglo XVII, casi todos los chinos vestían ropa de algodón. Casi en todas partes, la tela de algodón podía usarse como medio de intercambio . En la India, se fabricaba una cantidad significativa de textiles de algodón para mercados lejanos, a menudo producidos por tejedores profesionales. Algunos comerciantes también poseían pequeños talleres de tejido. La India producía una variedad de telas de algodón, algunas de ellas de una calidad excepcional. [44]

El algodón era una materia prima difícil de obtener para Europa antes de que se cultivara en las plantaciones coloniales en las Américas. [44] Los primeros exploradores españoles encontraron a los nativos americanos cultivando especies desconocidas de algodón de excelente calidad: el algodón de las islas marinas ( Gossypium barbadense ) y el algodón de semillas verdes de las tierras altas Gossypium hirsutum . El algodón de las islas marinas crecía en áreas tropicales y en las islas barrera de Georgia y Carolina del Sur, pero le fue mal en el interior. El algodón de las islas marinas comenzó a exportarse desde Barbados en la década de 1650. El algodón de semillas verdes de las tierras altas crecía bien en las áreas del interior del sur de los EE. UU., pero no era económico debido a la dificultad de quitar las semillas, un problema resuelto por la desmotadora de algodón . [26] : 157 Una cepa de semilla de algodón traída de México a Natchez, Mississippi , en 1806 se convirtió en el material genético original de más del 90% de la producción mundial de algodón actual; produjo cápsulas que se recolectaban de tres a cuatro veces más rápido. [44]

La Era de los Descubrimientos fue seguida por un período de colonialismo que comenzó alrededor del siglo XVI. Tras el descubrimiento de una ruta comercial hacia la India por parte de los portugueses alrededor del sur de África, los británicos fundaron la Compañía de las Indias Orientales , junto con compañías más pequeñas de diferentes nacionalidades que establecieron puestos comerciales y emplearon agentes para participar en el comercio en toda la región del Océano Índico. [44]

Uno de los segmentos más grandes de este comercio era el de los textiles de algodón, que se compraban en la India y se vendían en el sudeste asiático , incluido el archipiélago indonesio , donde se compraban especias para venderlas al sudeste asiático y a Europa. A mediados de la década de 1760, las telas representaban más de las tres cuartas partes de las exportaciones de la Compañía de las Indias Orientales. Los textiles indios tenían demanda en la región del Atlántico Norte de Europa, donde anteriormente solo había lana y lino disponibles; sin embargo, la cantidad de productos de algodón consumidos en Europa occidental fue menor hasta principios del siglo XIX. [44]

En 1600, los refugiados flamencos comenzaron a tejer telas de algodón en las ciudades inglesas donde el hilado y el tejido de lana y lino en las casas estaban bien establecidos. Los gremios los dejaron tranquilos porque no consideraban que el algodón fuera una amenaza. Los primeros intentos europeos de hilar y tejer algodón se produjeron en la Italia del siglo XII y en el sur de Alemania del siglo XV, pero estas industrias finalmente terminaron cuando se cortó el suministro de algodón. Los moros en España comenzaron a cultivar, hilar y tejer algodón alrededor del siglo X. [44]

Las telas británicas no podían competir con las telas indias porque el costo de la mano de obra en la India era aproximadamente entre una quinta y una sexta parte del de Gran Bretaña. [24] En 1700 y 1721, el gobierno británico aprobó las Leyes Calico para proteger las industrias nacionales de lana y lino de las crecientes cantidades de tela de algodón importadas de la India. [2] [48]

La demanda de telas más pesadas fue satisfecha por una industria doméstica con base en Lancashire que producía fustán , una tela con urdimbre de lino y trama de algodón . Se utilizó lino para la urdimbre porque el algodón hilado a rueda no tenía suficiente resistencia, pero la mezcla resultante no era tan suave como el algodón 100% y era más difícil de coser. [48]

En vísperas de la Revolución Industrial, el hilado y el tejido se hacían en los hogares, para el consumo doméstico y como una industria casera bajo el sistema de trabajo a domicilio . Ocasionalmente, el trabajo se hacía en el taller de un maestro tejedor. Bajo el sistema de trabajo a domicilio, los trabajadores a domicilio producían bajo contrato con los vendedores mercantes, quienes a menudo suministraban las materias primas. Fuera de temporada, las mujeres, típicamente las esposas de los granjeros, hacían el hilado y los hombres el tejido. Usando la rueca , se necesitaban entre cuatro y ocho hilanderos para abastecer a un tejedor de telar manual. [2] [48] [49] : 823

La lanzadera volante , patentada en 1733 por John Kay (con una serie de mejoras posteriores, incluida una importante en 1747), duplicó la producción de un tejedor, empeorando el desequilibrio entre el hilado y el tejido. Se empezó a utilizar ampliamente en Lancashire después de 1760, cuando el hijo de John, Robert , inventó la caja de caída, que facilitaba el cambio de colores de los hilos. [49] : 821–822

Lewis Paul patentó la máquina de hilar de rodillos y el sistema de bobinas y volantes para estirar la lana hasta obtener un grosor más uniforme. La tecnología se desarrolló con la ayuda de John Wyatt de Birmingham . Paul y Wyatt abrieron una fábrica en Birmingham que utilizaba su máquina de laminar impulsada por un burro. En 1743, se abrió una fábrica en Northampton con 50 husos en cada una de las cinco máquinas de Paul y Wyatt. Esta funcionó hasta aproximadamente 1764. Daniel Bourn construyó una fábrica similar en Leominster , pero se incendió. Tanto Lewis Paul como Daniel Bourn patentaron las máquinas de cardar en 1748. Basadas en dos juegos de rodillos que se desplazaban a diferentes velocidades, se utilizaron más tarde en la primera hilandería de algodón .

En 1764, en el pueblo de Stanhill, Lancashire, James Hargreaves inventó la hiladora Jenny , que patentó en 1770. Fue el primer marco de hilado práctico con múltiples husos. [50] La hiladora Jenny funcionaba de manera similar a la rueca, primero sujetando las fibras, luego sacándolas y luego retorciéndolas. [51] Era una máquina simple con marco de madera que solo costaba alrededor de £6 para un modelo de 40 husos en 1792 [52] y era utilizada principalmente por hilanderos caseros. La hiladora Jenny producía un hilo ligeramente retorcido solo adecuado para la trama, no para la urdimbre. [49] : 825–827

El bastidor de hilado o hilandero de agua fue desarrollado por Richard Arkwright, quien, junto con dos socios, lo patentó en 1769. El diseño se basó en parte en una máquina de hilar construida por Kay, quien fue contratada por Arkwright. [49] : 827–830 Para cada huso, el bastidor de agua usaba una serie de cuatro pares de rodillos, cada uno operando a una velocidad de rotación sucesivamente mayor, para extraer la fibra que luego era torcida por el huso. El espaciado entre los rodillos era ligeramente mayor que la longitud de la fibra. Un espaciado demasiado cercano causaba que las fibras se rompieran, mientras que un espaciado demasiado distante causaba un hilo desigual. Los rodillos superiores estaban cubiertos de cuero y la carga sobre los rodillos se aplicaba mediante un peso. Los pesos evitaban que la torsión retrocediera antes que los rodillos. Los rodillos inferiores eran de madera y metal, con estrías a lo largo de la longitud. El bastidor de agua podía producir un hilo duro de recuento medio adecuado para la urdimbre, lo que finalmente permitió que se fabricaran telas 100% algodón en Gran Bretaña. Arkwright y sus socios utilizaron la energía hidráulica en una fábrica de Cromford , Derbyshire , en 1771, lo que dio nombre al invento.

Samuel Crompton inventó la mula de hilar en 1779, llamada así porque es un híbrido entre la máquina de hilar de Arkwright y la máquina de hilar Jenny de James Hargreaves , de la misma manera que una mula es el producto del cruce de una yegua con un burro . La mula de Crompton era capaz de producir hilo más fino que el hilado a mano y a un menor coste. El hilo hilado por mula tenía la resistencia adecuada para ser utilizado como urdimbre y finalmente permitió a Gran Bretaña producir hilo altamente competitivo en grandes cantidades. [49] : 832

Al darse cuenta de que la expiración de la patente de Arkwright aumentaría en gran medida el suministro de algodón hilado y conduciría a una escasez de tejedores, Edmund Cartwright desarrolló un telar mecánico vertical que patentó en 1785. En 1776, patentó un telar operado por dos hombres. [49] : 834 El diseño del telar de Cartwright tenía varios defectos, el más grave era la rotura del hilo. Samuel Horrocks patentó un telar bastante exitoso en 1813. El telar de Horock fue mejorado por Richard Roberts en 1822, y estos fueron producidos en grandes cantidades por Roberts, Hill & Co. Roberts también fue un fabricante de máquinas herramienta de alta calidad y un pionero en el uso de plantillas y calibres para la medición de precisión en el taller. [53]

La demanda de algodón presentó una oportunidad a los plantadores del sur de los Estados Unidos, quienes pensaron que el algodón de las tierras altas sería un cultivo rentable si se pudiera encontrar una mejor manera de quitar las semillas. Eli Whitney respondió al desafío inventando la desmotadora de algodón económica . Un hombre que usara una desmotadora de algodón podría quitar las semillas de algodón de las tierras altas en un día, tanto como antes hubiera llevado dos meses procesar, trabajando a un ritmo de una libra de algodón por día. [26] [54]

Estos avances fueron capitalizados por empresarios , de los cuales el más conocido es Arkwright. Se le atribuye una lista de inventos, pero estos fueron desarrollados en realidad por personas como Kay y Thomas Highs ; Arkwright nutrió a los inventores, patentó las ideas, financió las iniciativas y protegió las máquinas. Creó la fábrica de algodón que unificó los procesos de producción en una fábrica, y desarrolló el uso de la energía (primero los caballos de fuerza y luego la energía hidráulica), lo que convirtió la fabricación de algodón en una industria mecanizada. Otros inventores aumentaron la eficiencia de los pasos individuales del hilado (cardado, torsión e hilado y enrollado) de modo que el suministro de hilo aumentó enormemente. Luego se aplicó la energía del vapor para impulsar la maquinaria textil. Manchester adquirió el apodo de Cottonopolis a principios del siglo XIX debido a su expansión de fábricas textiles. [55]

Aunque la mecanización redujo drásticamente el costo de las telas de algodón, a mediados del siglo XIX las telas tejidas a máquina todavía no podían igualar la calidad de las telas indias tejidas a mano, en parte debido a la finura del hilo que era posible gracias al tipo de algodón utilizado en la India, que permitía una gran cantidad de hilos. Sin embargo, la alta productividad de la industria textil británica permitió que las calidades más gruesas de las telas británicas se vendieran a un precio inferior al de las telas hiladas y tejidas a mano en la India, donde los salarios eran bajos, lo que acabó destruyendo la industria india. [44]

El hierro en barra era la forma comercial del hierro que se utilizaba como materia prima para fabricar artículos de ferretería, como clavos, alambres, bisagras, herraduras, neumáticos para carros, cadenas, etc., así como formas estructurales. Una pequeña cantidad de hierro en barra se convertía en acero. El hierro fundido se utilizaba para ollas, estufas y otros artículos en los que su fragilidad era tolerable. La mayor parte del hierro fundido se refinaba y se convertía en hierro en barra, con pérdidas sustanciales. El hierro en barra se fabricaba mediante el proceso de fundición de hierro , que fue el proceso predominante hasta finales del siglo XVIII.

En el Reino Unido, en 1720, se produjeron 20.500 toneladas de hierro fundido con carbón vegetal y 400 toneladas con coque. En 1750 , la producción de hierro fundido con carbón vegetal fue de 24.500 toneladas y la de hierro fundido con coque de 2.500 toneladas. En 1788, la producción de hierro fundido con carbón vegetal fue de 14.000 toneladas, mientras que la de hierro fundido con coque fue de 54.000 toneladas. En 1806, la producción de hierro fundido con carbón vegetal fue de 7.800 toneladas y la de hierro fundido con coque de 250.000 toneladas. [41] : 125

En 1750, el Reino Unido importó 31.200 toneladas de hierro en barras y, ya sea refinando a partir de hierro fundido o produciendo directamente 18.800 toneladas de hierro en barras utilizando carbón vegetal y 100 toneladas utilizando coque. En 1796, el Reino Unido estaba produciendo 125.000 toneladas de hierro en barras con coque y 6.400 toneladas con carbón vegetal; las importaciones fueron de 38.000 toneladas y las exportaciones de 24.600 toneladas. En 1806, el Reino Unido no importó hierro en barras, pero exportó 31.500 toneladas. [41] : 125

Un cambio importante en las industrias del hierro durante la Revolución Industrial fue la sustitución de la madera y otros biocombustibles por carbón ; para una cantidad dada de calor, la extracción de carbón requería mucho menos trabajo que cortar madera y convertirla en carbón vegetal , [57] y el carbón era mucho más abundante que la madera, cuyos suministros se estaban volviendo escasos antes del enorme aumento en la producción de hierro que tuvo lugar a fines del siglo XVIII. [2] [41] : 122

En 1709, Abraham Darby hizo progresos usando coque para alimentar sus altos hornos en Coalbrookdale . [58] Sin embargo, el arrabio de coque que él producía no era adecuado para hacer hierro forjado y se usaba principalmente para la producción de artículos de hierro fundido, como ollas y teteras. Tenía la ventaja sobre sus rivales en que sus ollas, fundidas mediante su proceso patentado, eran más delgadas y más baratas que las de ellos.

En 1750, el coque había reemplazado en general al carbón vegetal en la fundición de cobre y plomo y se usaba ampliamente en la producción de vidrio. En la fundición y refinación de hierro, el carbón y el coque producían hierro de inferior calidad que el producido con carbón vegetal debido al contenido de azufre del carbón. Se conocían carbones con bajo contenido de azufre, pero aún contenían cantidades nocivas. La conversión de carbón en coque solo reduce ligeramente el contenido de azufre. [41] : 122–125 Una minoría de los carbones son coquizables. Otro factor que limitaba la industria del hierro antes de la Revolución Industrial era la escasez de energía hidráulica para accionar los fuelles de explosión. Esta limitación fue superada por la máquina de vapor. [41]

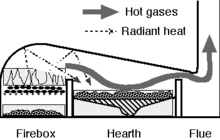

El uso del carbón en la fundición de hierro comenzó un poco antes de la Revolución Industrial, a partir de las innovaciones de Clement Clerke y otros a partir de 1678, que utilizaban hornos de reverbero de carbón conocidos como cubilotes. Estos se hacían funcionar con las llamas que se fundían en la mezcla de mineral y carbón vegetal o coque, reduciendo el óxido a metal. Esto tiene la ventaja de que las impurezas (como las cenizas de azufre) del carbón no migran al metal. Esta tecnología se aplicó al plomo a partir de 1678 y al cobre a partir de 1687. También se aplicó a la fundición de hierro en la década de 1690, pero en este caso el horno de reverbero se conocía como horno de aire. (El cubilote de fundición es una innovación diferente y posterior.) [59]

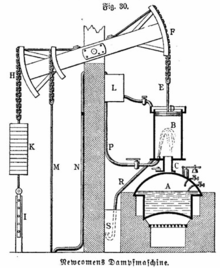

El arrabio de coque apenas se utilizó para producir hierro forjado hasta 1755-56, cuando el hijo de Darby, Abraham Darby II, construyó hornos en Horsehay y Ketley , donde había carbón con bajo contenido de azufre disponible (y no lejos de Coalbrookdale). Estos hornos estaban equipados con fuelles accionados por agua, que eran bombeados por máquinas de vapor Newcomen . Las máquinas Newcomen no estaban conectadas directamente a los cilindros de soplado porque las máquinas por sí solas no podían producir un chorro de aire constante. Abraham Darby III instaló cilindros de soplado similares accionados por agua y bombeados por vapor en la Dale Company cuando tomó el control en 1768. La Dale Company utilizó varias máquinas Newcomen para drenar sus minas y fabricó piezas para las máquinas que vendió en todo el país. [41] : 123–125

Las máquinas de vapor hicieron que el uso de soplado a mayor presión y volumen fuera práctico; sin embargo, el cuero usado en los fuelles era costoso de reemplazar. En 1757, el maestro siderúrgico John Wilkinson patentó un motor de soplado accionado hidráulicamente para altos hornos. [60] El cilindro de soplado para altos hornos se introdujo en 1760 y se cree que el primer cilindro de soplado hecho de hierro fundido fue el utilizado en Carrington en 1768, que fue diseñado por John Smeaton . [41] : 124, 135

Los cilindros de hierro fundido para su uso con un pistón eran difíciles de fabricar; los cilindros tenían que estar libres de agujeros y debían ser mecanizados para que quedaran lisos y rectos para eliminar cualquier deformación. James Watt tuvo grandes dificultades para intentar que le fabricaran un cilindro para su primera máquina de vapor. En 1774, Wilkinson inventó una máquina de mandrilar de precisión para mandrilar cilindros. Después de que Wilkinson perforara con éxito el primer cilindro para una máquina de vapor Boulton y Watt en 1776, recibió un contrato exclusivo para proporcionar cilindros. [26] [61] Después de que Watt desarrollara una máquina de vapor rotativa en 1782, se aplicaron ampliamente para soplar, martillar, laminar y cortar. [41] : 124

Las soluciones al problema del azufre fueron la adición de suficiente piedra caliza al horno para forzar el azufre a entrar en la escoria , así como el uso de carbón con bajo contenido de azufre. El uso de cal o piedra caliza requería temperaturas más altas en el horno para formar una escoria de flujo libre. El aumento de la temperatura del horno, posible gracias a un mejor soplado, también aumentó la capacidad de los altos hornos y permitió aumentar la altura del horno. [41] : 123–125

Además de su menor costo y mayor disponibilidad, el coque tenía otras ventajas importantes sobre el carbón, ya que era más duro y hacía que la columna de materiales (mineral de hierro, combustible, escoria) que fluía por el alto horno fuera más porosa y no se aplastara en los hornos mucho más altos de finales del siglo XIX. [62] [63]

A medida que el hierro fundido se volvió más barato y ampliamente disponible, comenzó a ser un material estructural para puentes y edificios. Un famoso ejemplo temprano es el Puente de Hierro construido en 1778 con hierro fundido producido por Abraham Darby III. [56] Sin embargo, la mayor parte del hierro fundido se convirtió en hierro forjado. La conversión del hierro fundido se había realizado durante mucho tiempo en una forja de refinación . Se desarrolló un proceso de refinación mejorado conocido como encapsulado y estampado , pero fue reemplazado por el proceso de pudling de Henry Cort . Cort desarrolló dos procesos importantes de fabricación de hierro: el laminado en 1783 y el pudling en 1784. [2] : 91 El pudling produjo un hierro de calidad estructural a un costo relativamente bajo.

El pudling era un método para descarburar el arrabio fundido mediante oxidación lenta en un horno de reverbero, revolviéndolo manualmente con una varilla larga. El pudlinger rastrillaba el hierro descarburado, que tiene un punto de fusión más alto que el hierro fundido, hasta formar bolas. Cuando la bola era lo suficientemente grande, la retiraba. El pudling era un trabajo agotador y extremadamente caliente. Pocos pudlingers vivían hasta los 40 años. [2] : 218 Debido a que el pudling se hacía en un horno de reverbero, se podía utilizar carbón o coque como combustible. El proceso de pudling se siguió utilizando hasta finales del siglo XIX, cuando el hierro estaba siendo reemplazado por el acero dulce. Debido a que el pudling requería habilidad humana para detectar las bolas de hierro, nunca se mecanizó con éxito. El laminado era una parte importante del proceso de pudling porque los rodillos ranurados expulsaban la mayor parte de la escoria fundida y consolidaban la masa de hierro forjado caliente. El laminado era 15 veces más rápido que un martillo de viaje . Un uso diferente del laminado, que se hacía a temperaturas más bajas que las utilizadas para expulsar la escoria, era la producción de láminas de hierro y, posteriormente, de formas estructurales como vigas, ángulos y rieles.

El proceso de pudling fue mejorado en 1818 por Baldwyn Rogers, quien reemplazó parte del revestimiento de arena en el fondo del horno de reverbero con óxido de hierro . [64] En 1838 , John Hall patentó el uso de ceniza de grifo tostada ( silicato de hierro ) para el fondo del horno, reduciendo en gran medida la pérdida de hierro a través del aumento de escoria causada por un fondo revestido de arena. La ceniza de grifo también aglutinaba algo de fósforo, pero esto no se entendía en ese momento. [41] : 166 El proceso de Hall también usaba cascarilla de hierro u óxido que reaccionaba con el carbono en el hierro fundido. El proceso de Hall, llamado pudling húmedo , redujo las pérdidas de hierro con la escoria de casi el 50% a alrededor del 8%. [2] : 93

El pudling se generalizó después de 1800. Hasta ese momento, los fabricantes de hierro británicos habían utilizado cantidades considerables de hierro importado de Suecia y Rusia para complementar los suministros nacionales. Debido al aumento de la producción británica, las importaciones comenzaron a disminuir en 1785 y, en la década de 1790, Gran Bretaña eliminó las importaciones y se convirtió en un exportador neto de hierro en barras.

El soplado caliente , patentado por el inventor escocés James Beaumont Neilson en 1828, fue el desarrollo más importante del siglo XIX para ahorrar energía en la fabricación de arrabio. Al utilizar aire de combustión precalentado, la cantidad de combustible para fabricar una unidad de arrabio se redujo al principio entre un tercio utilizando coque o dos tercios utilizando carbón; [65] las ganancias de eficiencia continuaron a medida que la tecnología mejoraba. [66] El soplado caliente también aumentó la temperatura de funcionamiento de los hornos, aumentando su capacidad. Usar menos carbón o coque significaba introducir menos impurezas en el arrabio. Esto significaba que se podía utilizar carbón de menor calidad en áreas donde el carbón de coque no estaba disponible o era demasiado caro; [67] sin embargo, a fines del siglo XIX los costos de transporte cayeron considerablemente.

Poco antes de la Revolución Industrial, se produjo una mejora en la producción de acero , que era un producto caro y se utilizaba solo donde el hierro no servía, como en herramientas de corte y resortes. Benjamin Huntsman desarrolló su técnica de acero al crisol en la década de 1740. La materia prima para esto era el acero blíster, fabricado mediante el proceso de cementación . [68] El suministro de hierro y acero más baratos ayudó a varias industrias, como las que fabricaban clavos, bisagras, alambre y otros artículos de ferretería. El desarrollo de máquinas herramienta permitió un mejor trabajo del hierro, lo que provocó que se utilizara cada vez más en las industrias de maquinaria y motores en rápido crecimiento. [69]

El desarrollo de la máquina de vapor estacionaria fue un elemento importante de la Revolución Industrial; sin embargo, durante el período inicial de la Revolución Industrial, la mayor parte de la energía industrial era suministrada por el agua y el viento. En Gran Bretaña, en 1800 se calculaba que el vapor suministraba unos 10.000 caballos de fuerza. En 1815, la energía del vapor había crecido hasta los 210.000 caballos de fuerza. [70]

El primer uso industrial comercialmente exitoso de la energía de vapor fue patentado por Thomas Savery en 1698. Construyó en Londres una bomba de agua combinada de vacío y presión de baja elevación que generaba aproximadamente un caballo de fuerza (hp) y se utilizó en numerosas plantas de abastecimiento de agua y en algunas minas (de ahí su "nombre comercial", The Miner's Friend ). La bomba de Savery era económica en rangos de potencia pequeños, pero era propensa a explosiones de calderas en tamaños más grandes. Las bombas de Savery continuaron produciéndose hasta fines del siglo XVIII. [71]

La primera máquina de vapor de pistón exitosa fue introducida por Thomas Newcomen antes de 1712. Las máquinas Newcomen se instalaron para drenar minas profundas que hasta entonces no se podían explotar, con el motor en la superficie; eran máquinas grandes, que requerían una cantidad significativa de capital para su construcción y producían más de 3,5 kW (5 hp). También se usaban para alimentar bombas de suministro de agua municipal. Eran extremadamente ineficientes para los estándares modernos, pero cuando se ubicaban donde el carbón era barato en las bocaminas, abrieron una gran expansión en la minería del carbón al permitir que las minas fueran más profundas. [72] A pesar de sus desventajas, las máquinas Newcomen eran confiables y fáciles de mantener y continuaron usándose en los yacimientos de carbón hasta las primeras décadas del siglo XIX.

En 1729, cuando murió Newcomen, sus máquinas se habían extendido a Hungría en 1722, y luego a Alemania, Austria y Suecia. Se sabe que se habían construido un total de 110 en 1733, cuando expiró la patente conjunta, de las cuales 14 estaban en el extranjero. En la década de 1770, el ingeniero John Smeaton construyó algunos ejemplos muy grandes e introdujo una serie de mejoras. En 1800 se habían construido un total de 1.454 máquinas. [72]

El escocés James Watt introdujo un cambio fundamental en los principios de funcionamiento . Con el apoyo financiero de su socio comercial, el inglés Matthew Boulton , en 1778 había logrado perfeccionar su máquina de vapor , que incorporaba una serie de mejoras radicales, en particular el cierre de la parte superior del cilindro, lo que hacía que el vapor a baja presión impulsara la parte superior del pistón en lugar de la atmósfera; el uso de una camisa de vapor; y la famosa cámara condensadora de vapor separada. El condensador separado eliminó el agua de refrigeración que se había inyectado directamente en el cilindro, lo que enfriaba el cilindro y desperdiciaba vapor. Asimismo, la camisa de vapor impedía que el vapor se condensara en el cilindro, lo que también mejoraba la eficiencia. Estas mejoras aumentaron la eficiencia del motor, de modo que los motores de Boulton y Watt usaban solo entre un 20 y un 25 % más de carbón por caballo de fuerza-hora que los de Newcomen. Boulton y Watt abrieron la Fundición Soho para la fabricación de tales motores en 1795.

En 1783, la máquina de vapor de Watt ya se había desarrollado por completo hasta convertirse en un tipo rotativo de doble efecto , lo que significaba que podía utilizarse para accionar directamente la maquinaria rotativa de una fábrica o un molino. Ambos tipos básicos de motores de Watt tuvieron un gran éxito comercial y, en 1800, la empresa Boulton & Watt había construido 496 motores, de los cuales 164 accionaban bombas reciprocantes, 24 servían a altos hornos y 308 alimentaban maquinaria de molino; la mayoría de los motores generaban de 3,5 a 7,5 kW (5 a 10 hp).

Hasta aproximadamente 1800, el modelo más común de máquina de vapor era la máquina de viga , construida como parte integral de una sala de máquinas de piedra o ladrillo, pero pronto se desarrollaron varios modelos de máquinas rotativas autónomas (fácilmente desmontables pero sin ruedas), como la máquina de mesa . A principios del siglo XIX, cuando expiró la patente de Boulton y Watt, el ingeniero de Cornualles Richard Trevithick y el estadounidense Oliver Evans comenzaron a construir máquinas de vapor sin condensación de alta presión, que expulsaban el vapor contra la atmósfera. La alta presión produjo un motor y una caldera lo suficientemente compactos para ser utilizados en locomotoras móviles de carretera y ferrocarril y en barcos de vapor . [73]

Hasta la electrificación generalizada a principios del siglo XX, las pequeñas necesidades energéticas industriales continuaron siendo satisfechas por la fuerza animal y humana . Entre ellas se encontraban talleres y maquinaria industrial ligera accionados por manivela , pedal y caballo. [74]

La maquinaria preindustrial fue construida por varios artesanos: los mecánicos construían molinos de agua y de viento ; los carpinteros hacían armazones de madera; y los herreros y torneros hacían piezas de metal. Los componentes de madera tenían la desventaja de cambiar de dimensiones con la temperatura y la humedad, y las diversas juntas tendían a aflojarse con el tiempo. A medida que avanzaba la Revolución Industrial, las máquinas con piezas y armazones de metal se volvieron más comunes. Otros usos importantes de las piezas de metal fueron en armas de fuego y sujetadores roscados , como tornillos para máquinas, pernos y tuercas. También existía la necesidad de precisión en la fabricación de piezas. La precisión permitiría un mejor funcionamiento de la maquinaria, la intercambiabilidad de piezas y la estandarización de los sujetadores roscados.

La demanda de piezas de metal condujo al desarrollo de varias máquinas herramienta . Tienen su origen en las herramientas desarrolladas en el siglo XVIII por los fabricantes de relojes y de instrumentos científicos para poder producir en serie pequeños mecanismos. Antes de la llegada de las máquinas herramienta, el metal se trabajaba manualmente utilizando las herramientas manuales básicas de martillos, limas, raspadores, sierras y cinceles. En consecuencia, el uso de piezas de maquinaria de metal se mantuvo al mínimo. Los métodos de producción manuales eran laboriosos y costosos, y era difícil lograr precisión. [43] [26]

La primera máquina herramienta de gran precisión fue la mandriladora de cilindros, inventada por John Wilkinson en 1774. Fue diseñada para mandrilar los grandes cilindros de las primeras máquinas de vapor. La máquina de Wilkinson fue la primera en utilizar el principio de mandrilado lineal, en el que la herramienta se apoya en ambos extremos, a diferencia de los diseños anteriores utilizados para mandrilar cañones que dependían de una barra mandriladora en voladizo menos estable . [26]

La cepilladora , la fresadora y la perfiladora se desarrollaron en las primeras décadas del siglo XIX. Aunque la fresadora se inventó en esta época, no se desarrolló como una herramienta de taller seria hasta algo más tarde en el siglo XIX. [43] [26] James Fox de Derby y Matthew Murray de Leeds fueron fabricantes de máquinas herramienta que tuvieron éxito en la exportación desde Inglaterra y también son notables por haber desarrollado la cepilladora casi al mismo tiempo que Richard Roberts de Manchester .

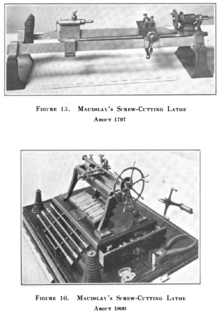

Henry Maudslay , que formó una escuela de fabricantes de máquinas herramienta a principios del siglo XIX, era un mecánico con una habilidad superior que había sido empleado en el Arsenal Real , Woolwich . Trabajó como aprendiz en el Arsenal Real con Jan Verbruggen . En 1774, Verbruggen había instalado una máquina perforadora horizontal que fue el primer torno de tamaño industrial en el Reino Unido. Maudslay fue contratado por Joseph Bramah para la producción de cerraduras de metal de alta seguridad que requerían una artesanía de precisión. Bramah patentó un torno que tenía similitudes con el torno de apoyo deslizante. [26] [49] : 392–395 Maudslay perfeccionó el torno de apoyo deslizante, que podía cortar tornillos de máquina de diferentes pasos de rosca mediante el uso de engranajes intercambiables entre el husillo y el tornillo guía. Antes de su invención, los tornillos no se podían cortar con precisión utilizando varios diseños de tornos anteriores, algunos de los cuales copiados de una plantilla. [26] [49] : 392–395 El torno con apoyo deslizante fue considerado uno de los inventos más importantes de la historia. Aunque no fue idea exclusiva de Maudslay, fue la primera persona en construir un torno funcional utilizando una combinación de innovaciones conocidas del husillo, el apoyo deslizante y los engranajes de cambio. [26] : 31, 36

Maudslay dejó el empleo de Bramah y montó su propio taller. Fue contratado para construir la maquinaria para fabricar poleas de barcos para la Marina Real Británica en Portsmouth Block Mills . Estas máquinas eran totalmente de metal y fueron las primeras máquinas para producción en masa y fabricación de componentes con un grado de intercambiabilidad. Las lecciones que Maudslay aprendió sobre la necesidad de estabilidad y precisión las adaptó al desarrollo de máquinas herramienta y en sus talleres formó a una generación de hombres para que siguieran trabajando sobre su trabajo, como Richard Roberts , Joseph Clement y Joseph Whitworth . [26]

Las técnicas para fabricar piezas metálicas producidas en masa con la precisión suficiente para ser intercambiables se atribuyen en gran medida a un programa del Departamento de Guerra de los EE. UU. que perfeccionó las piezas intercambiables para armas de fuego a principios del siglo XIX. [43] En el medio siglo siguiente a la invención de las máquinas herramienta fundamentales, la industria de la maquinaria se convirtió en el sector industrial más grande de la economía estadounidense, por valor agregado. [75]

La producción a gran escala de productos químicos fue un avance importante durante la Revolución Industrial. El primero de ellos fue la producción de ácido sulfúrico mediante el proceso de cámara de plomo inventado por el inglés John Roebuck (primer socio de James Watt) en 1746. Fue capaz de aumentar considerablemente la escala de fabricación al sustituir los recipientes de vidrio relativamente caros que se utilizaban anteriormente por cámaras más grandes y menos costosas hechas de láminas de plomo remachadas . En lugar de fabricar una pequeña cantidad cada vez, pudo fabricar alrededor de 50 kilogramos (100 libras) en cada una de las cámaras, al menos un aumento de diez veces.

La producción de un álcali a gran escala también se convirtió en un objetivo importante, y Nicolas Leblanc logró en 1791 introducir un método para la producción de carbonato de sodio (carbonato de sodio). El proceso Leblanc era una reacción de ácido sulfúrico con cloruro de sodio para dar sulfato de sodio y ácido clorhídrico . El sulfato de sodio se calentaba con carbonato de calcio y carbón para dar una mezcla de carbonato de sodio y sulfuro de calcio . Añadiendo agua se separaba el carbonato de sodio soluble del sulfuro de calcio. El proceso producía una gran cantidad de contaminación (el ácido clorhídrico se ventilaba inicialmente a la atmósfera y el sulfuro de calcio era un producto de desecho ). No obstante, este carbonato de sodio sintético resultó económico en comparación con el producido a partir de la quema de plantas específicas ( barilla o algas marinas ), que eran las fuentes dominantes anteriormente de carbonato de sodio, [76] y también con la potasa ( carbonato de potasio ) producida a partir de cenizas de madera dura. Estos dos productos químicos fueron muy importantes porque permitieron la introducción de una serie de otros inventos, reemplazando muchas operaciones a pequeña escala por procesos más rentables y controlables. El carbonato de sodio tuvo muchos usos en las industrias del vidrio, los textiles, el jabón y el papel. Los primeros usos del ácido sulfúrico incluyeron el decapado (eliminación del óxido) del hierro y el acero y el blanqueamiento de telas .

El desarrollo del polvo blanqueador ( hipoclorito de calcio ) por el químico escocés Charles Tennant en torno a 1800, basado en los descubrimientos del químico francés Claude Louis Berthollet , revolucionó los procesos de blanqueo en la industria textil al reducir drásticamente el tiempo requerido (de meses a días) para el proceso tradicional que se utilizaba entonces, que requería la exposición repetida al sol en campos de blanqueo después de remojar los tejidos con álcali o leche agria. La fábrica de Tennant en St Rollox , Glasgow , se convirtió en la planta química más grande del mundo.

Después de 1860, la innovación química se centró en los colorantes y Alemania asumió el liderazgo mundial, construyendo una fuerte industria química. [77] Los aspirantes a químicos acudieron en masa a las universidades alemanas en la era 1860-1914 para aprender las últimas técnicas. Los científicos británicos, por el contrario, carecían de universidades de investigación y no formaban a estudiantes avanzados; en cambio, la práctica era contratar químicos formados en Alemania. [78]

En 1824, Joseph Aspdin , un albañil británico convertido en constructor, patentó un proceso químico para fabricar cemento Portland , lo que supuso un avance importante en el sector de la construcción. Este proceso implica sinterizar una mezcla de arcilla y piedra caliza a unos 1400 °C (2552 °F), para luego molerla hasta obtener un polvo fino que luego se mezcla con agua, arena y grava para producir hormigón . El ingeniero inglés Marc Isambard Brunel utilizó hormigón de cemento Portland varios años después para construir el túnel del Támesis . [79] El hormigón se utilizó a gran escala en la construcción del sistema de alcantarillado de Londres una generación después.

Aunque otros hicieron una innovación similar en otros lugares, la introducción a gran escala de la iluminación a gas fue obra de William Murdoch , un empleado de Boulton & Watt. El proceso consistió en la gasificación a gran escala del carbón en hornos, la purificación del gas (eliminación de azufre, amoníaco e hidrocarburos pesados) y su almacenamiento y distribución. Las primeras empresas de iluminación a gas se establecieron en Londres entre 1812 y 1820. Pronto se convirtieron en uno de los principales consumidores de carbón en el Reino Unido. La iluminación a gas afectó a la organización social e industrial porque permitió que las fábricas y las tiendas permanecieran abiertas más tiempo que con velas de sebo o lámparas de aceite . Su introducción permitió que la vida nocturna floreciera en ciudades y pueblos, ya que los interiores y las calles podían iluminarse a mayor escala que antes. [80]

El vidrio se fabricaba en la antigua Grecia y Roma. [81] A principios del siglo XIX se desarrolló en Europa un nuevo método de producción de vidrio , conocido como proceso cilíndrico . En 1832, los hermanos Chance utilizaron este proceso para crear vidrio en láminas . Se convirtieron en los principales productores de vidrio para ventanas y placas. Este avance permitió crear paneles de vidrio más grandes sin interrupción, liberando así la planificación del espacio en los interiores, así como la fenestración de los edificios. El Palacio de Cristal es el ejemplo supremo del uso de vidrio en láminas en una estructura nueva e innovadora. [82]

En 1798, Louis-Nicolas Robert patentó en Francia una máquina para fabricar una hoja de papel continua sobre un bucle de tela metálica. La máquina de papel se conoce como Fourdrinier en honor a los hermanos Sealy y Henry Fourdrinier , financieros y papeleros de Londres. Aunque ha mejorado mucho y presenta muchas variaciones, la máquina Fourdrinier es el medio predominante de producción de papel en la actualidad. El método de producción continua demostrado por la máquina de papel influyó en el desarrollo del laminado continuo de hierro y, posteriormente, de acero, así como en otros procesos de producción continua. [83]

La Revolución Agrícola Británica se considera una de las causas de la Revolución Industrial porque la mejora de la productividad agrícola liberó a los trabajadores para trabajar en otros sectores de la economía. [84] En contraste, el suministro de alimentos per cápita en Europa estaba estancado o en declive y no mejoró en algunas partes de Europa hasta finales del siglo XVIII. [85]

El abogado inglés Jethro Tull inventó una sembradora mejorada en 1701. Se trataba de una sembradora mecánica que distribuía las semillas de manera uniforme en una parcela de tierra y las plantaba a la profundidad correcta. Esto era importante porque el rendimiento de las semillas cosechadas por las semillas plantadas en ese momento era de alrededor de cuatro o cinco. La sembradora de Tull era muy cara y no muy fiable, por lo que no tenía mucho efecto. Las sembradoras de buena calidad no se produjeron hasta mediados del siglo XVIII. [60] : 26

El arado Rotherham de Joseph Foljambe de 1730 fue el primer arado de hierro comercialmente exitoso. [84] : 122 [86] [60] : 18, 21 [87] La trilladora , inventada por el ingeniero escocés Andrew Meikle en 1784, reemplazó la trilla manual con un mayal , un trabajo laborioso que requería aproximadamente una cuarta parte del trabajo agrícola. [88] : 286 Los menores requisitos de mano de obra posteriormente resultaron en salarios más bajos y números de trabajadores agrícolas más bajos, que enfrentaron casi la inanición, lo que llevó a la rebelión agrícola de 1830 de los Swing Riots .

Las máquinas herramienta y las técnicas de metalurgia desarrolladas durante la Revolución Industrial finalmente dieron lugar a técnicas de fabricación de precisión a fines del siglo XIX para la producción en masa de equipos agrícolas, como segadoras, atadoras y cosechadoras. [43]

La minería de carbón en Gran Bretaña, particularmente en el sur de Gales , comenzó temprano. Antes de la máquina de vapor, los pozos eran a menudo pozos de campana poco profundos que seguían una veta de carbón a lo largo de la superficie, que se abandonaban a medida que se extraía el carbón. En otros casos, si la geología era favorable , el carbón se extraía por medio de un túnel excavado en la ladera de una colina. La minería de pozo se realizaba en algunas áreas, pero el factor limitante era el problema de la extracción de agua. Podía hacerse transportando baldes de agua por el pozo o hasta un sough (un túnel excavado en una colina para drenar una mina). En cualquier caso, el agua tenía que descargarse en un arroyo o zanja a un nivel donde pudiera fluir por gravedad. [89]

La introducción de la bomba de vapor por parte de Thomas Savery en 1698 y la máquina de vapor de Newcomen en 1712 facilitaron enormemente la extracción de agua y permitieron que los pozos se hicieran más profundos, lo que permitió extraer más carbón. Estos fueron desarrollos que habían comenzado antes de la Revolución Industrial, pero la adopción de las mejoras de John Smeaton a la máquina de Newcomen seguidas por las máquinas de vapor más eficientes de James Watt a partir de la década de 1770 redujeron los costos de combustible de las máquinas, lo que hizo que las minas fueran más rentables. La máquina de Cornish , desarrollada en la década de 1810, era mucho más eficiente que la máquina de vapor de Watt. [89]

La minería del carbón era muy peligrosa debido a la presencia de grisú en muchas vetas de carbón. La lámpara de seguridad , inventada en 1816 por Sir Humphry Davy y de forma independiente por George Stephenson , proporcionaba cierto grado de seguridad . Sin embargo, las lámparas resultaron ser un falso amanecer porque se volvían inseguras muy rápidamente y proporcionaban una luz débil. Las explosiones de grisú continuaron, a menudo provocando explosiones de polvo de carbón , por lo que las bajas aumentaron durante todo el siglo XIX. Las condiciones de trabajo eran muy malas, con una alta tasa de víctimas por desprendimientos de rocas.

Al comienzo de la Revolución Industrial, el transporte interior se hacía por ríos y carreteras navegables, y se utilizaban embarcaciones costeras para transportar mercancías pesadas por mar. Se utilizaban vías para carretas para transportar carbón a los ríos para su posterior envío, pero los canales aún no se habían construido ampliamente. Los animales proporcionaban toda la fuerza motriz en tierra, mientras que las velas proporcionaban la fuerza motriz en el mar. Los primeros ferrocarriles tirados por caballos se introdujeron hacia finales del siglo XVIII, y las locomotoras de vapor en las primeras décadas del siglo XIX. La mejora de las tecnologías de navegación a vela aumentó la velocidad media de navegación en un 50% entre 1750 y 1830. [90]

La Revolución Industrial mejoró la infraestructura de transporte de Gran Bretaña con una red de carreteras de peaje, una red de canales y vías navegables y una red ferroviaria. Las materias primas y los productos terminados podían transportarse con mayor rapidez y a menor costo que antes. La mejora del transporte también permitió que las nuevas ideas se difundieran rápidamente.

Antes y durante la Revolución Industrial, se mejoró la navegación en varios ríos británicos mediante la eliminación de obstrucciones, el enderezamiento de curvas, la ampliación y profundización, y la construcción de esclusas de navegación . En 1750, Gran Bretaña tenía más de 1600 kilómetros (1000 millas) de ríos y arroyos navegables. [2] : 46 Los canales y las vías fluviales permitieron transportar materiales a granel de manera económica a largas distancias tierra adentro. Esto se debió a que un caballo podía tirar de una barcaza con una carga docenas de veces mayor que la carga que podía arrastrarse en un carro. [49] [91]

Los canales comenzaron a construirse en el Reino Unido a fines del siglo XVIII para unir los principales centros manufactureros del país. Conocido por su enorme éxito comercial, el Canal de Bridgewater en el noroeste de Inglaterra , que se inauguró en 1761 y fue financiado principalmente por el tercer duque de Bridgewater . Desde Worsley hasta la ciudad de Manchester, en rápido crecimiento, su construcción costó £ 168,000 (£ 22,589,130 en 2013 [update]), [92] [93] pero sus ventajas sobre el transporte terrestre y fluvial significaron que dentro de un año de su apertura en 1761, el precio del carbón en Manchester cayó aproximadamente a la mitad. [94] Este éxito ayudó a inspirar un período de intensa construcción de canales, conocido como Canal Mania . [95] Los canales se construyeron apresuradamente con el objetivo de replicar el éxito comercial del Canal de Bridgewater, siendo los más notables el Canal de Leeds y Liverpool y el Canal del Támesis y Severn , que se abrieron en 1774 y 1789 respectivamente.

En la década de 1820 ya existía una red nacional. La construcción de canales sirvió como modelo para la organización y los métodos que se utilizaron más tarde para construir los ferrocarriles. Con el tiempo, fueron reemplazados en gran medida como empresas comerciales rentables por la expansión de los ferrocarriles a partir de la década de 1840. El último canal importante que se construyó en el Reino Unido fue el Canal Marítimo de Manchester , que, cuando se inauguró en 1894, era el canal marítimo más grande del mundo [96] y abrió Manchester como puerto . Sin embargo, nunca alcanzó el éxito comercial que sus patrocinadores habían esperado y señaló que los canales eran un modo de transporte moribundo en una era dominada por los ferrocarriles, que eran más rápidos y, a menudo, más baratos.

La red de canales de Gran Bretaña, junto con los edificios industriales que aún se conservan, es una de las características más duraderas de la Revolución Industrial temprana que se pueden ver en Gran Bretaña. [97]

Francia era conocida por tener un excelente sistema de carreteras en la época de la Revolución Industrial; sin embargo, la mayoría de las carreteras del continente europeo y del Reino Unido estaban en malas condiciones y peligrosamente llenas de baches. [91] [27] Gran parte del sistema de carreteras británico original estaba mal mantenido por miles de parroquias locales, pero a partir de la década de 1720 (y ocasionalmente antes) se crearon fideicomisos de peaje para cobrar peajes y mantener algunas carreteras. A partir de la década de 1750, un número cada vez mayor de carreteras principales se convirtieron en autopistas hasta el punto de que casi todas las carreteras principales de Inglaterra y Gales eran responsabilidad de un fideicomiso de autopistas. John Metcalf , Thomas Telford y, sobre todo, John McAdam construyeron nuevas carreteras de ingeniería , siendo el primer tramo de carretera " macadán " Marsh Road en Ashton Gate , Bristol, en 1816. [99] La primera carretera de macadán en los EE. UU. fue la "Boonsborough Turnpike Road" entre Hagerstown y Boonsboro, Maryland, en 1823. [98]

Las principales autopistas partían de Londres y eran el medio por el cual el Correo Real podía llegar al resto del país. El transporte de mercancías pesadas en estas carreteras se hacía mediante carros lentos de ruedas anchas tirados por yuntas de caballos. Las mercancías más ligeras se transportaban en carros más pequeños o en yuntas de caballos de carga . Las diligencias transportaban a los ricos, y los menos ricos podían pagar para viajar en los carros de los transportistas . La productividad del transporte por carretera aumentó enormemente durante la Revolución Industrial, y el coste de los viajes cayó drásticamente. Entre 1690 y 1840, la productividad casi se triplicó para el transporte de larga distancia y se cuadruplicó en el de las diligencias. [100]

Los ferrocarriles se hicieron prácticos gracias a la introducción generalizada del hierro fundido barato después de 1800, el laminador para fabricar rieles y el desarrollo de la máquina de vapor de alta presión también alrededor de 1800. La reducción de la fricción fue una de las principales razones del éxito de los ferrocarriles en comparación con los vagones. Esto se demostró en un tranvía de madera cubierto con placas de hierro en 1805 en Croydon, Inglaterra.

Un buen caballo puede arrastrar dos mil libras, o una tonelada, en una carretera normal. Se invitó a un grupo de caballeros a presenciar el experimento, para que se pudiera demostrar la superioridad de la nueva carretera mediante una demostración visual. Se cargaron doce carros con piedras, hasta que cada uno de ellos llegó a pesar tres toneladas, y se ataron los carros entre sí. Luego se les ató un caballo, que tiró de los carros con facilidad, seis millas [10 km] en dos horas, habiéndose detenido cuatro veces para demostrar que tenía la capacidad de arrancar, así como de tirar de su gran carga. [101]

Las vías para el transporte de carbón en las zonas mineras se habían construido en el siglo XVII y solían estar asociadas a sistemas de canales o ríos para el posterior transporte del carbón. Todas ellas eran tiradas por caballos o dependían de la gravedad, con una máquina de vapor estacionaria para llevar las carretas de vuelta a la cima de la pendiente. Las primeras aplicaciones de la locomotora de vapor fueron en vías para carretas o placas (como se las llamaba entonces a menudo por las placas de hierro fundido que se utilizaban). Los ferrocarriles públicos tirados por caballos comenzaron a principios del siglo XIX, cuando las mejoras en la producción de hierro fundido y hierro forjado estaban reduciendo los costos.

Las locomotoras de vapor comenzaron a construirse después de la introducción de los motores de vapor de alta presión, una vez que expiró la patente de Boulton y Watt en 1800. Los motores de alta presión expulsaban el vapor usado a la atmósfera, eliminando el condensador y el agua de refrigeración. También eran mucho más ligeros y de menor tamaño para una potencia dada que los motores de condensación estacionarios. Algunas de estas primeras locomotoras se utilizaron en minas. Los ferrocarriles públicos impulsados por vapor comenzaron con el ferrocarril Stockton y Darlington en 1825. [102]

La rápida introducción de los ferrocarriles siguió a las pruebas de Rainhill de 1829 , que demostraron el exitoso diseño de locomotoras de Robert Stephenson y al desarrollo en 1828 del aire caliente , que redujo drásticamente el consumo de combustible para fabricar hierro y aumentó la capacidad del alto horno. El 15 de septiembre de 1830, se inauguró el Ferrocarril de Liverpool y Manchester , el primer ferrocarril interurbano del mundo, al que asistió el primer ministro Arthur Wellesley . [103] El ferrocarril fue diseñado por Joseph Locke y George Stephenson , y unió la ciudad industrial de Manchester, en rápida expansión, con la ciudad portuaria de Liverpool. La inauguración se vio empañada por problemas causados por la naturaleza primitiva de la tecnología empleada; sin embargo, los problemas se resolvieron gradualmente y el ferrocarril tuvo un gran éxito, transportando pasajeros y mercancías.

El éxito del ferrocarril interurbano, en particular en el transporte de mercancías y productos básicos, dio lugar a la manía ferroviaria . La construcción de grandes ferrocarriles que conectaban las ciudades y pueblos más grandes comenzó en la década de 1830, pero solo cobró impulso al final de la primera Revolución Industrial. Después de que muchos de los trabajadores terminaron de construir los ferrocarriles, no regresaron a sus estilos de vida rurales, sino que permanecieron en las ciudades, proporcionando trabajadores adicionales para las fábricas.

A nivel estructural, la Revolución Industrial planteó a la sociedad la llamada cuestión social , exigiendo nuevas ideas para gestionar grandes grupos de individuos. La pobreza visible por un lado y el crecimiento de la población y la riqueza materialista por el otro provocaron tensiones entre los muy ricos y los más pobres de la sociedad. [104] Estas tensiones se liberaron a veces violentamente [105] y dieron lugar a ideas filosóficas como el socialismo , el comunismo y el anarquismo .

Antes de la Revolución Industrial, la mayor parte de la fuerza laboral trabajaba en la agricultura, ya fuera como agricultores autónomos, propietarios o arrendatarios de tierras, o como trabajadores agrícolas sin tierra . Era común que las familias de diversas partes del mundo hilaran, tejieran y confeccionaran su propia ropa. Las familias también hilaban y tejían para la producción comercial. Al comienzo de la Revolución Industrial, India, China y algunas regiones de Irak y otras partes de Asia y Oriente Medio producían la mayor parte de las telas de algodón del mundo, mientras que los europeos producían artículos de lana y lino.

En Gran Bretaña , en el siglo XVI, se practicaba el sistema de producción a domicilio , mediante el cual los agricultores y los habitantes de las ciudades producían bienes para un mercado en sus hogares, a menudo descrito como industria casera . Los bienes típicos del sistema de producción a domicilio incluían el hilado y el tejido. Los capitalistas mercantiles normalmente proporcionaban las materias primas, pagaban a los trabajadores por pieza y eran responsables de la venta de los bienes. La malversación de suministros por parte de los trabajadores y la mala calidad eran problemas comunes. El esfuerzo logístico para obtener y distribuir materias primas y recoger los productos terminados también eran limitaciones del sistema de producción a domicilio. [2] : 57–59

Algunas de las primeras máquinas de hilar y tejer, como una máquina Jenny de 40 husos por unas seis libras en 1792, eran asequibles para los habitantes de las cabañas. [2] : 59 La maquinaria posterior, como las máquinas de hilar, las mulas de hilar y los telares mecánicos, eran caras (especialmente si funcionaban con agua), lo que dio lugar a la propiedad capitalista de las fábricas.

La mayoría de los trabajadores de las fábricas textiles durante la Revolución Industrial eran mujeres solteras y niños, incluidos muchos huérfanos. Por lo general, trabajaban de 12 a 14 horas por día y solo descansaban los domingos. Era común que las mujeres aceptaran trabajos en las fábricas de forma estacional durante los períodos de poca actividad agrícola. La falta de transporte adecuado, las largas horas de trabajo y los bajos salarios dificultaban la contratación y el mantenimiento de los trabajadores. [44]

Karl Marx consideró desfavorablemente el cambio en la relación social del trabajador de fábrica en comparación con los agricultores y los campesinos ; sin embargo, reconoció el aumento de la productividad que fue posible gracias a la tecnología. [106]

Algunos economistas, como Robert Lucas Jr. , dicen que el efecto real de la Revolución Industrial fue que "por primera vez en la historia, los niveles de vida de las masas de la gente común han comenzado a experimentar un crecimiento sostenido... Los economistas clásicos no mencionan nada remotamente parecido a este comportamiento económico, ni siquiera como una posibilidad teórica". [12] Otros argumentan que, si bien el crecimiento de los poderes productivos generales de la economía no tuvo precedentes durante la Revolución Industrial, los niveles de vida de la mayoría de la población no crecieron significativamente hasta finales del siglo XIX y XX y que, en muchos sentidos, los niveles de vida de los trabajadores disminuyeron bajo el capitalismo temprano: algunos estudios han estimado que los salarios reales en Gran Bretaña solo aumentaron un 15% entre los años 1780 y 1850 y que la esperanza de vida en Gran Bretaña no comenzó a aumentar drásticamente hasta la década de 1870. [13] [14]

La altura media de la población disminuyó durante la Revolución Industrial, lo que implica que su estado nutricional también estaba disminuyendo. [107] [108]

Durante la Revolución Industrial, la esperanza de vida de los niños aumentó drásticamente. El porcentaje de niños nacidos en Londres que murieron antes de los cinco años disminuyó del 74,5% en 1730-1749 al 31,8% en 1810-1829. [109] Los efectos sobre las condiciones de vida han sido controvertidos y fueron objeto de acalorados debates entre los historiadores económicos y sociales desde los años 1950 hasta los años 1980. [110] Durante el período de 1813 a 1913, hubo un aumento significativo de los salarios de los trabajadores. [111] [112]

El hambre crónica y la desnutrición eran la norma para la mayoría de la población del mundo, incluida Gran Bretaña y Francia, hasta finales del siglo XIX. Hasta aproximadamente 1750, la desnutrición limitaba la esperanza de vida en Francia a unos 35 años y a unos 40 años en Gran Bretaña. La población de los Estados Unidos de la época estaba adecuadamente alimentada, era mucho más alta en promedio y tenía una esperanza de vida de 45 a 50 años, aunque la esperanza de vida estadounidense disminuyó unos pocos años a mediados del siglo XIX. El consumo de alimentos per cápita también disminuyó durante un episodio conocido como el rompecabezas antebellum . [113]

El suministro de alimentos en Gran Bretaña se vio afectado negativamente por las Leyes del Maíz (1815-1846), que imponían aranceles a los granos importados. Las leyes se promulgaron para mantener los precios altos y beneficiar a los productores nacionales. Las Leyes del Maíz fueron derogadas en los primeros años de la Gran Hambruna Irlandesa .

Las tecnologías iniciales de la Revolución Industrial, como los textiles mecanizados, el hierro y el carbón, hicieron poco, o nada, para reducir los precios de los alimentos . [85] En Gran Bretaña y los Países Bajos, el suministro de alimentos aumentó antes de la Revolución Industrial con mejores prácticas agrícolas; sin embargo, la población también creció. [2] [88] [114] [115]

El rápido crecimiento demográfico en el siglo XIX incluyó las nuevas ciudades industriales y manufactureras, así como centros de servicios como Edimburgo y Londres. [116] El factor crítico fue la financiación, que fue manejada por sociedades de construcción que trataban directamente con grandes empresas contratistas. [117] [118] El alquiler privado de las viviendas a los propietarios era la tenencia dominante. P. Kemp dice que esto solía ser una ventaja para los inquilinos. [119] La gente se mudó tan rápidamente que no había suficiente capital para construir viviendas adecuadas para todos, por lo que los recién llegados de bajos ingresos se apiñaron en barrios marginales cada vez más superpoblados . El agua potable , el saneamiento y las instalaciones de salud pública eran inadecuados; la tasa de mortalidad era alta, especialmente la mortalidad infantil y la tuberculosis entre los adultos jóvenes. El cólera por agua contaminada y la fiebre tifoidea eran endémicas. A diferencia de las áreas rurales, no hubo hambrunas como la que devastó Irlanda en la década de 1840. [120] [121] [122]

Se generó una gran cantidad de literatura de denuncia de las condiciones insalubres. La publicación más famosa, con diferencia, fue la de uno de los fundadores del movimiento socialista: La situación de la clase obrera en Inglaterra, de 1844. Friedrich Engels describe los barrios marginales de Manchester y otras ciudades industriales, donde la gente vivía en chabolas y chozas rudimentarias, algunas no completamente cerradas, otras con suelos de tierra. Estas chabolas tenían pasillos estrechos entre parcelas y viviendas de forma irregular. No había instalaciones sanitarias. La densidad de población era extremadamente alta. [123] Sin embargo, no todo el mundo vivía en condiciones tan pobres. La Revolución Industrial también creó una clase media de empresarios, oficinistas, capataces e ingenieros que vivían en condiciones mucho mejores.

Las condiciones mejoraron a lo largo del siglo XIX con nuevas leyes de salud pública que regulaban aspectos como el alcantarillado, la higiene y la construcción de viviendas. En la introducción de su edición de 1892, Engels señala que la mayoría de las condiciones sobre las que escribió en 1844 habían mejorado enormemente. Por ejemplo, la Ley de Salud Pública de 1875 ( 38 y 39 Vict. c. 55) dio lugar a la ordenanza más sanitaria de las casas adosadas .

En la época preindustrial, el suministro de agua se basaba en sistemas de gravedad y el agua se bombeaba mediante ruedas hidráulicas. Las tuberías solían estar hechas de madera. Las bombas de vapor y las tuberías de hierro permitieron el suministro generalizado de agua a los abrevaderos de los caballos y a los hogares. [27]

El libro de Engels describe cómo las aguas residuales sin tratar creaban olores horribles y volvían verdes los ríos en las ciudades industriales. En 1854, John Snow atribuyó un brote de cólera en el Soho de Londres a la contaminación fecal de un pozo público de agua por un pozo negro doméstico . Los hallazgos de Snow de que el cólera podía propagarse a través del agua contaminada tardaron algunos años en ser aceptados, pero su trabajo condujo a cambios fundamentales en el diseño de los sistemas públicos de agua y desechos.

In the 18th century, there were relatively high levels of literacy among farmers in England and Scotland. This permitted the recruitment of literate craftsmen, skilled workers, foremen, and managers who supervised the emerging textile factories and coal mines. Much of the labour was unskilled, and especially in textile mills children as young as eight proved useful in handling chores and adding to the family income. Indeed, children were taken out of school to work alongside their parents in the factories. However, by the mid-19th century, unskilled labor forces were common in Western Europe, and British industry moved upscale, needing many more engineers and skilled workers who could handle technical instructions and handle complex situations. Literacy was essential to be hired.[124][125] A senior government official told Parliament in 1870:

The invention of the paper machine and the application of steam power to the industrial processes of printing supported a massive expansion of newspaper and pamphlet publishing, which contributed to rising literacy and demands for mass political participation.[127]

Consumers benefited from falling prices for clothing and household articles such as cast iron cooking utensils, and in the following decades, stoves for cooking and space heating. Coffee, tea, sugar, tobacco, and chocolate became affordable to many in Europe. The consumer revolution in England from the early 17th century to the mid-18th century had seen a marked increase in the consumption and variety of luxury goods and products by individuals from different economic and social backgrounds.[128] With improvements in transport and manufacturing technology, opportunities for buying and selling became faster and more efficient than previous. The expanding textile trade in the north of England meant the three-piece suit became affordable to the masses.[129] Founded by potter and retail entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood in 1759, Wedgwood fine china and porcelain tableware was starting to become a common feature on dining tables.[130] Rising prosperity and social mobility in the 18th century increased the number of people with disposable income for consumption, and the marketing of goods (of which Wedgwood was a pioneer) for individuals, as opposed to items for the household, started to appear, and the new status of goods as status symbols related to changes in fashion and desired for aesthetic appeal.[130]

With the rapid growth of towns and cities, shopping became an important part of everyday life. Window shopping and the purchase of goods became a cultural activity in its own right, and many exclusive shops were opened in elegant urban districts: in the Strand and Piccadilly in London, for example, and in spa towns such as Bath and Harrogate. Prosperity and expansion in manufacturing industries such as pottery and metalware increased consumer choice dramatically. Where once labourers ate from metal platters with wooden implements, ordinary workers now dined on Wedgwood porcelain. Consumers came to demand an array of new household goods and furnishings: metal knives and forks, for example, as well as rugs, carpets, mirrors, cooking ranges, pots, pans, watches, clocks, and a dizzying array of furniture. The age of mass consumption had arrived.

— "Georgian Britain, The rise of consumerism", Matthew White, British Library.[129]

New businesses in various industries appeared in towns and cities throughout Britain. Confectionery was one such industry that saw rapid expansion. According to food historian Polly Russell: "chocolate and biscuits became products for the masses, thanks to the Industrial Revolution and the consumers it created. By the mid-19th century, sweet biscuits were an affordable indulgence and business was booming. Manufacturers such as Huntley & Palmers in Reading, Carr's of Carlisle and McVitie's in Edinburgh transformed from small family-run businesses into state-of-the-art operations".[131] In 1847 Fry's of Bristol produced the first chocolate bar.[132] Their competitor Cadbury of Birmingham was the first to commercialize the association between confectionery and romance when they produced a heart-shaped box of chocolates for Valentine's Day in 1868.[133] The department store became a common feature in major High Streets across Britain; one of the first was opened in 1796 by Harding, Howell & Co. on Pall Mall in London.[134] In the 1860s, fish and chip shops emerged across the country in order to satisfy the needs of the growing industrial population.[135]