La Unión de Repúblicas Socialistas Soviéticas [u] ( URSS ), [v] comúnmente conocida como la Unión Soviética , [w] fue un país transcontinental que se extendió por gran parte de Eurasia desde 1922 hasta 1991. Durante su existencia, fue el país más grande por área , extendiéndose a través de once zonas horarias y compartiendo fronteras con doce países , y el tercer país más poblado . [x] Un sucesor general del Imperio ruso , estaba organizado nominalmente como una unión federal de repúblicas nacionales , la más grande y poblada de las cuales era la RSFS de Rusia . [y] En la práctica, su gobierno y economía estaban altamente centralizados . Como estado de partido único gobernado por el Partido Comunista de la Unión Soviética , era un estado comunista insignia . Su capital y ciudad más grande era Moscú .

Las raíces de la Unión Soviética se encuentran en la Revolución de Octubre de 1917. El nuevo gobierno, encabezado por Vladimir Lenin , estableció la República Socialista Federativa Soviética de Rusia (RSFSR), [z] el primer estado constitucionalmente socialista del mundo . La revolución no fue aceptada por todos dentro de la República Rusa , lo que resultó en la Guerra Civil Rusa . La RSFSR y las repúblicas soviéticas subordinadas se fusionaron en la Unión Soviética en 1922. Después de la muerte de Lenin en 1924, Joseph Stalin llegó al poder, inaugurando una rápida industrialización y colectivización forzada que condujo a un crecimiento económico significativo, pero contribuyó a una hambruna entre 1930 y 1933 que mató a millones. El sistema de campos de trabajo forzado del Gulag se expandió. A fines de la década de 1930, Stalin llevó a cabo la Gran Purga para eliminar a los opositores, lo que resultó en muerte masiva, encarcelamiento y deportación. En 1939, la URSS y la Alemania nazi firmaron un pacto de no agresión, pero en 1941, Alemania invadió la Unión Soviética en la mayor invasión terrestre de la historia, abriendo el Frente Oriental de la Segunda Guerra Mundial . Los soviéticos desempeñaron un papel decisivo en la derrota de las potencias del Eje , sufriendo aproximadamente 27 millones de bajas , que representaron la mayoría de las pérdidas aliadas . Después de la guerra , la Unión Soviética consolidó el territorio ocupado por el Ejército Rojo , formando estados satélites , y emprendió un rápido desarrollo económico que consolidó su condición de superpotencia .

Las tensiones geopolíticas con los EE. UU. llevaron a la Guerra Fría . El Bloque Occidental liderado por Estados Unidos se fusionó en la OTAN en 1949, lo que llevó a la Unión Soviética a formar su propia alianza militar, el Pacto de Varsovia , en 1955. Ninguno de los dos bandos participó en una confrontación militar directa y, en cambio, luchó sobre una base ideológica y mediante guerras por poderes . En 1953, tras la muerte de Stalin , la Unión Soviética emprendió una campaña de desestalinización bajo Nikita Khrushchev , que vio reversiones y rechazos de las políticas estalinistas. Esta campaña causó tensiones con la China comunista . Durante la década de 1950, la Unión Soviética amplió sus esfuerzos en la exploración espacial y tomó la delantera en la carrera espacial con el primer satélite artificial , el primer vuelo espacial humano , la primera estación espacial y la primera sonda en aterrizar en otro planeta . En 1985, el último líder soviético, Mijaíl Gorbachov , buscó reformar el país a través de sus políticas de glásnost y perestroika . En 1989, varios países del Pacto de Varsovia derrocaron a sus regímenes respaldados por la Unión Soviética y estallaron movimientos nacionalistas y separatistas en toda la Unión Soviética. En 1991, en medio de los esfuerzos por preservar el país como una federación renovada , un intento de golpe de Estado contra Gorbachov por parte de comunistas de línea dura impulsó a las repúblicas más grandes (Ucrania, Rusia y Bielorrusia) a separarse. El 26 de diciembre, Gorbachov reconoció oficialmente la disolución de la Unión Soviética . Boris Yeltsin , el líder de la RSFSR, supervisó su reconstitución en la Federación Rusa , que se convirtió en el estado sucesor de la Unión Soviética; todas las demás repúblicas surgieron como estados postsoviéticos completamente independientes .

Durante su existencia, la Unión Soviética produjo muchos logros e innovaciones sociales y tecnológicas importantes . Tenía la segunda economía más grande del mundo y el mayor ejército permanente. Un estado designado por el TNP , manejaba el arsenal de armas nucleares más grande del mundo . Como nación aliada, fue miembro fundador de las Naciones Unidas , así como uno de los cinco miembros permanentes del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas . Antes de su disolución, la URSS era una de las dos superpotencias del mundo a través de su hegemonía en Europa del Este, influencia diplomática e ideológica global (particularmente en el Sur Global ), fortalezas militares y económicas y logros científicos .

La palabra soviet se deriva de la palabra rusa sovet (ruso: совет ), que significa 'consejo', 'asamblea', 'consejo', [aa] que en última instancia deriva de la raíz verbal protoeslava de * vět-iti ('informar'), relacionada con el eslavo věst ('noticias'), del inglés wise . La palabra sovietnik significa 'consejero'. [5] Algunas organizaciones en la historia rusa fueron llamadas consejo (ruso: совет ). En el Imperio ruso , el Consejo de Estado , que funcionó desde 1810 hasta 1917, fue conocido como Consejo de Ministros. [5]

Los Soviets como consejos obreros aparecieron por primera vez durante la Revolución rusa de 1905. [6] [7] Aunque fueron rápidamente suprimidos por el ejército imperial, después de la Revolución de febrero de 1917 , los Soviets de obreros y soldados surgieron en todo el país y compartieron el poder con el Gobierno provisional ruso . [6] [8] Los bolcheviques, liderados por Vladímir Lenin , exigieron que todo el poder fuera transferido a los Soviets, y obtuvieron el apoyo de los obreros y soldados. [9] Después de la Revolución de octubre , en la que los bolcheviques tomaron el poder del Gobierno provisional en nombre de los Soviets, [8] [10] Lenin proclamó la formación de la República Federativa Socialista Soviética de Rusia (RSFSR). [11]

Durante el asunto georgiano de 1922, Lenin pidió que la RSFS de Rusia y otras repúblicas soviéticas nacionales formaran una unión mayor que inicialmente denominó Unión de Repúblicas Soviéticas de Europa y Asia (en ruso: Союз Советских Республик Европы и Азии , romanizado : Soyuz Sovyetskikh Respublik Evropy i Azii ). [12] Joseph Stalin inicialmente se resistió a la propuesta de Lenin, pero finalmente la aceptó y, con el acuerdo de Lenin, cambió el nombre a Unión de Repúblicas Socialistas Soviéticas (URSS), aunque todas las repúblicas comenzaron como soviet socialistas y no cambiaron al otro orden hasta 1936 . Además, en las lenguas regionales de varias repúblicas, la palabra consejo o conciliar en el idioma respectivo fue cambiada bastante tarde a una adaptación del ruso soviet y nunca en otros, por ejemplo, en la RSS de Ucrania .

СССР (en el alfabeto latino: SSSR ) es la abreviatura del cognado en idioma ruso de URSS, tal como se escribe en letras cirílicas . Los soviéticos usaban esta abreviatura con tanta frecuencia que el público de todo el mundo se familiarizó con su significado. Después de esto, la inicial rusa más común es Союз ССР (transliteración: Soyuz SSR ) que esencialmente se traduce como Unión de SSR en español. Además, la forma corta del nombre ruso Советский Союз (transliteración: Sovyetsky Soyuz , que literalmente significa Unión Soviética ) también se usa comúnmente, pero solo en su forma no abreviada. Desde el comienzo de la Gran Guerra Patria , a más tardar, abreviar el nombre ruso de la Unión Soviética como СС ha sido un tabú, ya que СС, como abreviatura cirílica rusa, está asociada con las infames Schutzstaffel de la Alemania nazi , como SS en inglés.

En los medios de comunicación en lengua inglesa, se hacía referencia al Estado como Unión Soviética o URSS. La RSFS de Rusia dominaba la Unión Soviética hasta tal punto que, durante la mayor parte de la existencia de la Unión Soviética, se la conocía de manera coloquial, pero incorrecta, como Rusia .

La historia de la Unión Soviética comenzó con los ideales de la Revolución bolchevique y terminó en disolución en medio del colapso económico y la desintegración política. Fundada en 1922 tras la Guerra Civil Rusa , la Unión Soviética se convirtió rápidamente en un estado de partido único bajo el mando del Partido Comunista . Sus primeros años bajo el gobierno de Lenin estuvieron marcados por la implementación de políticas socialistas y la Nueva Política Económica (NEP), que permitió reformas orientadas al mercado.

El ascenso de Iósif Stalin a finales de la década de 1920 marcó el comienzo de una era de intensa centralización y totalitarismo. El gobierno de Stalin se caracterizó por la colectivización forzada de la agricultura , la rápida industrialización y la Gran Purga , que eliminó a los enemigos percibidos del Estado. La Unión Soviética desempeñó un papel crucial en la victoria aliada en la Segunda Guerra Mundial , pero a un tremendo costo humano, ya que millones de ciudadanos soviéticos perecieron en el conflicto.

La Unión Soviética surgió como una de las dos superpotencias del mundo, liderando el Bloque del Este en oposición al Bloque Occidental durante la Guerra Fría . Este período vio a la URSS participar en una carrera armamentista, la carrera espacial y guerras por poderes en todo el mundo. El liderazgo posterior a Stalin, particularmente bajo Nikita Khrushchev , inició un proceso de desestalinización , que condujo a un período de liberalización y apertura relativa conocido como el Deshielo de Khrushchev . Sin embargo, la era posterior bajo Leonid Brezhnev , conocida como la Era del Estancamiento , estuvo marcada por el declive económico, la corrupción política y una gerontocracia rígida . A pesar de los esfuerzos por mantener el estatus de superpotencia de la Unión Soviética, la economía tuvo problemas debido a su naturaleza centralizada, el atraso tecnológico y las ineficiencias. Los enormes gastos militares y las cargas de mantener el Bloque del Este tensaron aún más la economía soviética.

En la década de 1980, las políticas de Glasnost (apertura) y Perestroika (reestructuración) de Mijail Gorbachov apuntaban a revitalizar el sistema soviético, pero en cambio aceleraron su desintegración. Los movimientos nacionalistas ganaron impulso en todas las repúblicas soviéticas y el control del Partido Comunista se debilitó. El fallido intento de golpe de Estado en agosto de 1991 contra Gorbachov por parte de comunistas de línea dura aceleró el fin de la Unión Soviética , que se disolvió formalmente el 26 de diciembre de 1991, poniendo fin a casi siete décadas de gobierno soviético.

_of_the_Tian_Shan_mountain_range).jpg/440px-The_Soviet_Union_1964_CPA_3139_stamp_(Development_of_mountaineering_in_Russia._Mountain_Khan_Tengri_(6,995_m)_of_the_Tian_Shan_mountain_range).jpg)

Con una superficie de 22.402.200 kilómetros cuadrados (8.649.500 millas cuadradas), la Unión Soviética era el país más grande del mundo, [14] un estatus que conserva la Federación Rusa . [15] Cubriendo una sexta parte de la superficie terrestre de la Tierra, su tamaño era comparable al de América del Norte . [16] Otros dos estados sucesores, Kazajistán y Ucrania , se encuentran entre los 10 países principales por área terrestre y el país más grande completamente en Europa, respectivamente. La parte europea representó una cuarta parte del área del país y fue el centro cultural y económico. La parte oriental en Asia se extendía hasta el Océano Pacífico al este y Afganistán al sur y, excepto algunas áreas en Asia Central , era mucho menos poblada. Se extendía más de 10.000 kilómetros (6.200 millas) de este a oeste a través de 11 zonas horarias , y más de 7.200 kilómetros (4.500 millas) de norte a sur. Tenía cinco zonas climáticas: tundra , taiga , estepas , desierto y montañas .

La URSS, al igual que Rusia , tenía la frontera más larga del mundo , con más de 60.000 kilómetros (37.000 millas), o 1+1 ⁄ 2 circunferencias de la Tierra. Dos tercios de ella eran costas . El país limitaba con Afganistán , la República Popular China , Checoslovaquia , Finlandia , Hungría , Irán , Mongolia , Corea del Norte , Noruega , Polonia , Rumania y Turquía desde 1945 hasta 1991. El estrecho de Bering separaba a la URSS de los Estados Unidos .

La montaña más alta del país era el Pico del Comunismo (ahora Pico Ismoil Somoni ) en Tayikistán , con 7.495 metros (24.590 pies). La URSS también incluía la mayoría de los lagos más grandes del mundo: el mar Caspio (compartido con Irán ) y el lago Baikal , el lago de agua dulce más grande (en volumen) y más profundo del mundo, que también es un cuerpo de agua interno en Rusia.

Los países vecinos eran conscientes de los altos niveles de contaminación de la Unión Soviética [17] [18], pero tras la disolución de la Unión Soviética se descubrió que sus problemas ambientales eran mayores de lo que admitían las autoridades soviéticas [19] . La Unión Soviética era el segundo mayor productor mundial de emisiones nocivas. En 1988, las emisiones totales de la Unión Soviética eran aproximadamente el 79% de las de los Estados Unidos. Pero como el PNB soviético era sólo el 54% del de los Estados Unidos, esto significa que la Unión Soviética generaba 1,5 veces más contaminación que los Estados Unidos por unidad de PNB [20] .

El desastre soviético de Chernóbil en 1986 fue el primer accidente importante en una planta nuclear civil . [21] [22] [23] Sin precedentes en el mundo, resultó en la liberación de una gran cantidad de isótopos radiactivos a la atmósfera. Las dosis radiactivas se dispersaron relativamente lejos. [24] Aunque se desconocían los efectos a largo plazo del accidente, en el momento del accidente se notificaron 4.000 nuevos casos de cáncer de tiroides que resultaron de la contaminación del accidente, pero esto provocó un número relativamente bajo de muertes (datos de la OMS, 2005). [25] Otro accidente radiactivo importante fue el desastre de Kyshtym . [26]

La península de Kola fue uno de los lugares con mayores problemas. [27] Alrededor de las ciudades industriales de Monchegorsk y Norilsk , donde se extrae níquel , por ejemplo, todos los bosques han sido destruidos por la contaminación, mientras que el norte y otras partes de Rusia se han visto afectadas por las emisiones. [28] Durante la década de 1990, la gente en Occidente también se interesó por los peligros radiactivos de las instalaciones nucleares, los submarinos nucleares desmantelados y el procesamiento de desechos nucleares o combustible nuclear gastado . [29] [30] También se supo a principios de la década de 1990 que la URSS había transportado material radiactivo al mar de Barents y al mar de Kara , lo que luego fue confirmado por el parlamento ruso. El accidente del submarino K-141 Kursk en 2000 en Occidente generó más preocupaciones. [31] En el pasado, hubo accidentes que involucraron a los submarinos K-19 , K-8 , K-129 , K-27 , K-219 y K-278 Komsomolets . [32] [33] [34] [35]

Había tres jerarquías de poder en la Unión Soviética: la legislatura representada por el Soviet Supremo de la Unión Soviética , el gobierno representado por el Consejo de Ministros , y el Partido Comunista de la Unión Soviética (PCUS), el único partido legal y el máximo responsable de las políticas en el país. [36]

En la cúspide del Partido Comunista estaba el Comité Central , elegido en los Congresos y Conferencias del Partido . A su vez, el Comité Central votaba por un Politburó (llamado Presidium entre 1952 y 1966), el Secretariado y el secretario general (Primer Secretario de 1953 a 1966), el cargo de facto más alto en la Unión Soviética. [37] Dependiendo del grado de consolidación del poder, era el Politburó como cuerpo colectivo o el Secretario General, que siempre era uno de los miembros del Politburó, quien dirigía efectivamente el partido y el país [38] (excepto durante el período de la autoridad altamente personalizada de Stalin, ejercida directamente a través de su posición en el Consejo de Ministros en lugar del Politburó después de 1941). [39] No estaban controlados por la militancia general del partido, ya que el principio clave de la organización del partido era el centralismo democrático , que exigía una estricta subordinación a los órganos superiores, y las elecciones no eran objeto de concurso, respaldando a los candidatos propuestos desde arriba. [40]

El Partido Comunista mantuvo su dominio sobre el Estado principalmente a través de su control sobre el sistema de nombramientos . Todos los altos funcionarios del gobierno y la mayoría de los diputados del Soviet Supremo eran miembros del PCUS. De los propios jefes del partido, Stalin (1941-1953) y Jruschov (1958-1964) fueron primeros ministros. Tras el retiro forzoso de Jruschov, al líder del partido se le prohibió este tipo de doble afiliación, [41] pero los secretarios generales posteriores, al menos durante una parte de su mandato, ocuparon el puesto mayoritariamente ceremonial de presidente del Presidium del Soviet Supremo , el jefe nominal del Estado . Las instituciones de niveles inferiores eran supervisadas y a veces suplantadas por organizaciones primarias del partido . [42]

Sin embargo, en la práctica, el grado de control que el partido pudo ejercer sobre la burocracia estatal, particularmente después de la muerte de Stalin, estuvo lejos de ser total, ya que la burocracia perseguía diferentes intereses que a veces estaban en conflicto con el partido, [43] ni el partido en sí era monolítico de arriba a abajo, aunque las facciones estaban oficialmente prohibidas . [44]

El Soviet Supremo (sucesor del Congreso de los Soviets ) fue nominalmente el órgano estatal más alto durante la mayor parte de la historia soviética, [45] actuando al principio como una institución de sello de goma, aprobando e implementando todas las decisiones tomadas por el partido. Sin embargo, sus poderes y funciones se ampliaron a fines de la década de 1950, 1960 y 1970, incluida la creación de nuevas comisiones y comités estatales. Obtuvo poderes adicionales relacionados con la aprobación de los Planes Quinquenales y el presupuesto del gobierno . [46] El Soviet Supremo eligió un Presidium (sucesor del Comité Ejecutivo Central ) para ejercer su poder entre sesiones plenarias, [47] celebradas ordinariamente dos veces al año, y nombró al Tribunal Supremo , [48] al Procurador General [49] y al Consejo de Ministros (conocido antes de 1946 como el Consejo de Comisarios del Pueblo ), encabezado por el Presidente (Premier) y gestionando una enorme burocracia responsable de la administración de la economía y la sociedad. [47] Las estructuras estatales y partidarias de las repúblicas constituyentes emularon en gran medida la estructura de las instituciones centrales, aunque la RSFS de Rusia, a diferencia de las otras repúblicas constituyentes, durante la mayor parte de su historia no tuvo una rama republicana del PCUS, siendo gobernada directamente por el partido de toda la unión hasta 1990. Las autoridades locales se organizaron igualmente en comités del partido , soviets locales y comités ejecutivos . Si bien el sistema estatal era nominalmente federal, el partido era unitario. [50]

La policía de seguridad del Estado (el KGB y sus agencias predecesoras ) desempeñó un papel importante en la política soviética. Fue instrumental en el Terror Rojo y la Gran Purga , [51] pero quedó bajo estricto control del partido después de la muerte de Stalin. Bajo Yuri Andropov , el KGB participó en la supresión de la disidencia política y mantuvo una extensa red de informantes, reafirmándose como un actor político en cierta medida independiente de la estructura del partido-estado, [52] que culminó en la campaña anticorrupción dirigida a funcionarios de alto rango del partido a fines de la década de 1970 y principios de la de 1980. [53]

La constitución , promulgada en 1924 , 1936 y 1977 , [54] no limitaba el poder estatal. No existía una separación formal de poderes entre el Partido, el Soviet Supremo y el Consejo de Ministros [55] que representaban las ramas ejecutiva y legislativa del gobierno. El sistema se regía menos por estatutos que por convenciones informales, y no existía ningún mecanismo establecido de sucesión del liderazgo. Se produjeron luchas de poder amargas y a veces mortales en el Politburó después de las muertes de Lenin [56] y Stalin, [57] así como después de la destitución de Jruschov, [58] debido a una decisión tanto del Politburó como del Comité Central. [59] Todos los líderes del Partido Comunista antes de Gorbachov murieron en el cargo, excepto Georgy Malenkov [60] y Jruschov, ambos destituidos de la dirección del partido en medio de una lucha interna dentro del partido. [59]

Entre 1988 y 1990, frente a una considerable oposición, Mijaíl Gorbachov promulgó reformas que desviaban el poder de los órganos superiores del partido y hacían que el Soviet Supremo fuera menos dependiente de ellos. Se estableció el Congreso de los Diputados del Pueblo , la mayoría de cuyos miembros fueron elegidos directamente en elecciones competitivas celebradas en marzo de 1989, las primeras en la historia soviética. El Congreso ahora elegía al Soviet Supremo, que se convirtió en un parlamento de tiempo completo, y mucho más fuerte que antes. Por primera vez desde la década de 1920, se negó a aprobar las propuestas del partido y el Consejo de Ministros. [61] En 1990, Gorbachov introdujo y asumió el cargo de Presidente de la Unión Soviética , concentró el poder en su oficina ejecutiva, independiente del partido, y subordinó el gobierno, [62] ahora rebautizado como Gabinete de Ministros de la URSS , a sí mismo. [63]

Las tensiones aumentaron entre las autoridades de toda la Unión bajo Gorbachov, los reformistas liderados en Rusia por Boris Yeltsin y que controlaban el recién elegido Soviet Supremo de la RSFS de Rusia , y los comunistas de línea dura. Entre el 19 y el 21 de agosto de 1991, un grupo de línea dura organizó un intento de golpe de Estado . El golpe fracasó y el Consejo de Estado de la Unión Soviética se convirtió en el máximo órgano del poder estatal "en el período de transición". [64] Gorbachov dimitió como secretario general, permaneciendo como presidente sólo durante los últimos meses de existencia de la URSS. [65]

El poder judicial no era independiente de los demás poderes del Estado. El Tribunal Supremo supervisaba a los tribunales inferiores ( Tribunal Popular ) y aplicaba la ley tal como la establecía la Constitución o la interpretaba el Soviet Supremo. El Comité de Supervisión Constitucional revisaba la constitucionalidad de las leyes y los actos. La Unión Soviética utilizaba el sistema inquisitivo del derecho romano , en el que el juez, el procurador y el abogado defensor colaboraban para "establecer la verdad". [66]

Los derechos humanos en la Unión Soviética estaban severamente limitados. La Unión Soviética fue un estado totalitario desde 1927 hasta 1953 [67] [68] [69] [70] y un estado de partido único hasta 1990. [71] La libertad de expresión fue suprimida y la disidencia fue castigada. No se toleraron las actividades políticas independientes, ya sea que implicaran la participación en sindicatos libres, corporaciones privadas , iglesias independientes o partidos políticos de oposición . La libertad de movimiento dentro y especialmente fuera del país estaba limitada. El estado restringió los derechos de los ciudadanos a la propiedad privada .

Según la Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos , los derechos humanos son los " derechos y libertades fundamentales que corresponden a todos los seres humanos" [72], incluidos el derecho a la vida y a la libertad , la libertad de expresión y la igualdad ante la ley ; y los derechos sociales, culturales y económicos, incluido el derecho a participar en la cultura , el derecho a la alimentación , el derecho al trabajo y el derecho a la educación .

La concepción soviética de los derechos humanos era muy diferente del derecho internacional . Según la teoría jurídica soviética , "es el gobierno el beneficiario de los derechos humanos que deben hacerse valer frente al individuo". [73] El Estado soviético era considerado la fuente de los derechos humanos. [74] Por lo tanto, el sistema jurídico soviético consideraba la ley como un brazo de la política y también consideraba a los tribunales como agencias del gobierno. [75] Se otorgaron amplios poderes extrajudiciales a las agencias de policía secreta soviéticas . En la práctica, el gobierno soviético frenó significativamente el estado de derecho , las libertades civiles , la protección de la ley y las garantías de propiedad , [76] [77] que fueron considerados como ejemplos de "moral burguesa" por los teóricos del derecho soviético como Andrey Vyshinsky . [78]

La URSS y otros países del bloque soviético se habían abstenido de afirmar la Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos (1948), diciendo que era "demasiado jurídica" y potencialmente infringía la soberanía nacional. [79] : 167–169 La Unión Soviética firmó más tarde documentos de derechos humanos legalmente vinculantes, como el Pacto Internacional de Derechos Civiles y Políticos en 1973 (y el Pacto Internacional de Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales de 1966 ), pero no eran ampliamente conocidos o accesibles para las personas que vivían bajo el régimen comunista, ni eran tomados en serio por las autoridades comunistas. [80] : 117 Bajo Joseph Stalin , la pena de muerte se extendió a adolescentes de tan solo 12 años en 1935. [81] [82] [83]

Sergei Kovalev recordó "el famoso artículo 125 de la Constitución, que enumeraba todos los derechos civiles y políticos básicos" de la Unión Soviética. Pero cuando él y otros prisioneros intentaron utilizarlo como base legal para sus denuncias de abusos, el argumento del fiscal fue que "la Constitución no fue escrita para ustedes, sino para los negros estadounidenses, para que supieran lo feliz que es la vida de los ciudadanos soviéticos". [84]

El crimen no se definía como una infracción de la ley, sino como cualquier acción que pudiera amenazar al Estado y la sociedad soviéticos. Por ejemplo, el deseo de obtener beneficios podía interpretarse como una actividad contrarrevolucionaria castigada con la muerte. [75] La liquidación y deportación de millones de campesinos en 1928-31 se llevó a cabo dentro de los términos del Código Civil Soviético. [75] Algunos juristas soviéticos incluso dijeron que la "represión criminal" podía aplicarse en ausencia de culpabilidad. [75] Martin Latsis , jefe de la policía secreta de la Ucrania soviética, explicó: "No miren en el archivo de pruebas incriminatorias para ver si el acusado se levantó o no contra los soviéticos con armas o palabras. Pregúntenle en cambio a qué clase pertenece, cuál es su origen, su educación , su profesión . Estas son las preguntas que determinarán el destino del acusado. Ese es el significado y la esencia del Terror Rojo ". [85]

El objetivo de los procesos públicos no era "demostrar la existencia o ausencia de un delito -eso estaba predeterminado por las autoridades correspondientes del partido- sino proporcionar otro foro para la agitación política y la propaganda para la instrucción de la ciudadanía (véase, por ejemplo, los Procesos de Moscú ). Los abogados defensores, que tenían que ser miembros del partido , estaban obligados a dar por sentada la culpabilidad de su cliente..." [75]

Durante su gobierno, Stalin siempre tomó las decisiones políticas finales. De lo contrario, la política exterior soviética era establecida por la comisión de Política Exterior del Comité Central del Partido Comunista de la Unión Soviética , o por el órgano más alto del partido, el Politburó . Las operaciones eran manejadas por el Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores independiente . Fue conocido como el Comisariado del Pueblo para Asuntos Exteriores (o Narkomindel), hasta 1946. Los portavoces más influyentes fueron Georgy Chicherin (1872-1936), Maxim Litvinov (1876-1951), Vyacheslav Molotov (1890-1986), Andrey Vyshinsky (1883-1954) y Andrei Gromyko (1909-1989). Los intelectuales estaban basados en el Instituto Estatal de Relaciones Internacionales de Moscú . [86]

La dirigencia marxista-leninista de la Unión Soviética debatió intensamente cuestiones de política exterior y cambió de rumbo varias veces. Incluso después de que Stalin asumiera el control dictatorial a fines de la década de 1920, hubo debates y él cambió de postura con frecuencia. [99]

Durante los primeros años de la historia del país, se suponía que pronto estallarían revoluciones comunistas en todos los grandes países industriales y que Rusia tenía la responsabilidad de ayudarlas. El Comintern era el arma preferida. Estallaron algunas revoluciones, pero fueron rápidamente reprimidas (la más duradera fue la de Hungría); la República Soviética Húngara duró sólo del 21 de marzo al 1 de agosto de 1919. Los bolcheviques rusos no estaban en condiciones de prestar ninguna ayuda.

En 1921, Lenin, Trotsky y Stalin se dieron cuenta de que el capitalismo se había estabilizado en Europa y que no habría revoluciones generalizadas en un futuro próximo. Los bolcheviques rusos tenían el deber de proteger lo que tenían en Rusia y evitar enfrentamientos militares que pudieran destruir su cabeza de puente. Rusia era ahora un estado paria, junto con Alemania. En 1922, los dos países llegaron a un acuerdo con el Tratado de Rapallo, que resolvió antiguos agravios. Al mismo tiempo, los dos países establecieron en secreto programas de entrenamiento para las operaciones ilegales del ejército y la fuerza aérea alemanes en campos ocultos en la URSS. [100]

Moscú finalmente dejó de amenazar a otros estados y, en cambio, trabajó para abrir relaciones pacíficas en términos de comercio y reconocimiento diplomático. El Reino Unido desestimó las advertencias de Winston Churchill y algunos otros sobre una amenaza marxista-leninista continua, y abrió relaciones comerciales y reconocimiento diplomático de facto en 1922. Hubo esperanza de un arreglo de las deudas zaristas de antes de la guerra, pero se pospuso repetidamente. El reconocimiento formal llegó cuando el nuevo Partido Laborista llegó al poder en 1924. [101] Todos los demás países siguieron el ejemplo en la apertura de relaciones comerciales. Henry Ford abrió relaciones comerciales a gran escala con los soviéticos a fines de la década de 1920, con la esperanza de que conduciría a una paz a largo plazo. Finalmente, en 1933, Estados Unidos reconoció oficialmente a la URSS, una decisión respaldada por la opinión pública y especialmente por los intereses comerciales estadounidenses que esperaban una apertura de un nuevo mercado rentable. [102]

A finales de la década de 1920 y principios de la de 1930, Stalin ordenó a los partidos marxistas-leninistas de todo el mundo que se opusieran firmemente a los partidos políticos no marxistas, a los sindicatos y a otras organizaciones de izquierda, a los que calificaron de socialfascistas . En el uso de la Unión Soviética, y de la Comintern y sus partidos afiliados en este período, el epíteto fascista se utilizó para describir la sociedad capitalista en general y prácticamente cualquier actividad u opinión antisoviética o antiestalinista. [103] Stalin dio marcha atrás en 1934 con el programa del Frente Popular que llamaba a todos los partidos marxistas a unirse a todas las fuerzas políticas, laborales y organizativas antifascistas que se oponían al fascismo , especialmente a la variedad nazi . [104] [105]

El rápido crecimiento del poder en la Alemania nazi alentó a París y Moscú a formar una alianza militar, y el Tratado franco-soviético de asistencia mutua se firmó en mayo de 1935. Un firme creyente en la seguridad colectiva, el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores de Stalin, Maxim Litvinov, trabajó muy duro para formar una relación más estrecha con Francia y Gran Bretaña. [106]

En 1939, medio año después del Acuerdo de Múnich , la URSS intentó formar una alianza antinazi con Francia y Gran Bretaña. [107] Adolf Hitler propuso un mejor acuerdo, que daría a la URSS el control sobre gran parte de Europa del Este a través del Pacto Mólotov-Ribbentrop . En septiembre, Alemania invadió Polonia, y la URSS también invadió más tarde ese mes, lo que resultó en la partición de Polonia. En respuesta, Gran Bretaña y Francia declararon la guerra a Alemania, lo que marcó el comienzo de la Segunda Guerra Mundial . [108]

Hasta su muerte en 1953, Iósif Stalin controló todas las relaciones exteriores de la Unión Soviética durante el período de entreguerras . A pesar de la creciente acumulación de la maquinaria bélica de Alemania y el estallido de la Segunda Guerra Sino-Japonesa , la Unión Soviética no cooperó con ninguna otra nación, optando por seguir su propio camino. [109] Sin embargo, después de la Operación Barbarroja , las prioridades de la Unión Soviética cambiaron. A pesar del conflicto previo con el Reino Unido , Vyacheslav Molotov abandonó sus demandas fronterizas de posguerra. [110]

La Guerra Fría fue un período de tensión geopolítica entre Estados Unidos y la Unión Soviética y sus respectivos aliados, el Bloque Occidental y el Bloque Oriental , que comenzó después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en 1945. El término guerra fría se utiliza porque no hubo combates a gran escala directamente entre las dos superpotencias , sino que cada una de ellas apoyó importantes conflictos regionales conocidos como guerras por poderes . El conflicto se basó en la lucha ideológica y geopolítica por la influencia global de estas dos superpotencias, tras su alianza temporal y victoria contra la Alemania nazi en 1945. Aparte del desarrollo del arsenal nuclear y el despliegue militar convencional, la lucha por el dominio se expresó a través de medios indirectos como la guerra psicológica , las campañas de propaganda, el espionaje , los embargos de largo alcance , la rivalidad en eventos deportivos y las competiciones tecnológicas como la carrera espacial .

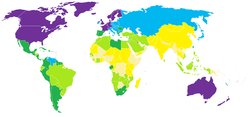

Constitucionalmente, la URSS era una federación de Repúblicas federadas constituyentes, que eran estados unitarios, como Ucrania o Bielorrusia (RSS), o federaciones, como Rusia o Transcaucasia (RSFS), [36] las cuatro siendo las repúblicas fundadoras que firmaron el Tratado de Creación de la URSS en diciembre de 1922. En 1924, durante la delimitación nacional en Asia Central, Uzbekistán y Turkmenistán se formaron a partir de partes de la ASSR de Turkestán de Rusia y dos dependencias soviéticas, las PSP de Jorezm y Bujará . En 1929, Tayikistán se separó de la RSS de Uzbekistán. Con la constitución de 1936, la RSFS de Transcaucasia se disolvió, lo que resultó en que sus repúblicas constituyentes de Armenia , Georgia y Azerbaiyán se elevaran a Repúblicas de la Unión, mientras que Kazajstán y Kirguistán se separaron de la RSFS de Rusia, lo que resultó en el mismo estatus. [111] En agosto de 1940, Moldavia se formó a partir de partes de Ucrania y Besarabia ocupada por los soviéticos , y la República Socialista Soviética de Ucrania. Estonia , Letonia y Lituania también fueron anexadas por la Unión Soviética y se convirtieron en Repúblicas Socialista Soviéticas, lo que no fue reconocido por la mayoría de la comunidad internacional y se consideró una ocupación ilegal . Después de la invasión soviética de Finlandia , la República Socialista Soviética de Karelo-Finlandia se formó en territorio anexado como una República de la Unión en marzo de 1940 y luego se incorporó a Rusia como la República Socialista Soviética Autónoma de Carelia en 1956. Entre julio de 1956 y septiembre de 1991, hubo 15 repúblicas de la unión (ver mapa a continuación). [112]

Aunque nominalmente era una unión de iguales, en la práctica la Unión Soviética estaba dominada por los rusos . La dominación era tan absoluta que durante la mayor parte de su existencia, el país era comúnmente (pero incorrectamente) referido como "Rusia". Si bien la SFSR rusa era técnicamente solo una república dentro de la unión más grande, era de lejos la más grande (tanto en términos de población como de área), la más poderosa y la más desarrollada. La SFSR rusa también era el centro industrial de la Unión Soviética. El historiador Matthew White escribió que era un secreto a voces que la estructura federal del país era "una fachada" para el dominio ruso. Por esa razón, a los habitantes de la URSS generalmente se los llamaba "rusos", no "soviéticos", ya que "todos sabían quién realmente dirigía el espectáculo". [113]

Según la Ley Militar de septiembre de 1925, las Fuerzas Armadas Soviéticas estaban formadas por las Fuerzas Terrestres , la Fuerza Aérea , la Armada , la Dirección Política Estatal Conjunta (OGPU) y las Tropas Internas . [114] La OGPU se independizó más tarde y en 1934 se unió a la policía secreta NKVD , por lo que sus tropas internas estaban bajo el liderazgo conjunto de las comisarías de defensa e interior. Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, se formaron las Fuerzas de Misiles Estratégicos (1959), las Fuerzas de Defensa Aérea (1948) y las Fuerzas Nacionales de Defensa Civil (1970), que ocuparon el primer, tercer y sexto lugar en el sistema oficial soviético de importancia (las fuerzas terrestres fueron segundas, la Fuerza Aérea cuarta y la Armada quinta).

El ejército tenía la mayor influencia política. En 1989, prestaban servicio dos millones de soldados divididos entre 150 divisiones motorizadas y 52 divisiones blindadas. Hasta principios de la década de 1960, la marina soviética era una rama militar bastante pequeña, pero después de la crisis del Caribe , bajo el liderazgo de Sergei Gorshkov , se expandió significativamente. Se hizo famosa por los cruceros de batalla y los submarinos. En 1989, prestaban servicio 500 000 hombres. La Fuerza Aérea Soviética se centró en una flota de bombarderos estratégicos y, en situaciones de guerra, debía erradicar la infraestructura y la capacidad nuclear del enemigo. La fuerza aérea también tenía una serie de cazas y bombarderos tácticos para apoyar al ejército en la guerra. Las fuerzas de misiles estratégicos tenían más de 1.400 misiles balísticos intercontinentales (ICBM), desplegados entre 28 bases y 300 centros de mando.

En el período de posguerra, el ejército soviético participó directamente en varias operaciones militares en el extranjero. [3] [115] [116] Estas incluyeron la represión del levantamiento en Alemania del Este (1953), la revolución húngara (1956) y la invasión de Checoslovaquia (1968). La Unión Soviética también participó en la guerra de Afganistán entre 1979 y 1989 .

En la Unión Soviética se aplicaba el servicio militar obligatorio general , es decir, todos los varones sanos mayores de 18 años eran reclutados en las fuerzas armadas. [117]

La Unión Soviética adoptó una economía de comando , en la que la producción y distribución de bienes estaban centralizadas y dirigidas por el gobierno. La primera experiencia bolchevique con una economía de comando fue la política del comunismo de guerra , que implicó la nacionalización de la industria, la distribución centralizada de la producción, la requisición coercitiva o forzosa de la producción agrícola e intentos de eliminar la circulación de dinero, las empresas privadas y el libre comercio . Las tropas de barrera también se utilizaron para imponer el control bolchevique sobre los suministros de alimentos en áreas controladas por el Ejército Rojo, un papel que pronto les valió el odio de la población civil rusa. [118] Después del severo colapso económico, Lenin reemplazó el comunismo de guerra por la Nueva Política Económica (NEP) en 1921, legalizando el libre comercio y la propiedad privada de pequeñas empresas. La economía se recuperó de manera constante como resultado. [119]

Después de un largo debate entre los miembros del Politburó sobre el curso del desarrollo económico, en 1928-1929, al obtener el control del país, Stalin abandonó la NEP e impulsó una planificación central completa, iniciando la colectivización forzada de la agricultura y promulgando una legislación laboral draconiana. Se movilizaron recursos para una rápida industrialización , que expandió significativamente la capacidad soviética en la industria pesada y los bienes de capital durante la década de 1930. [119] La principal motivación para la industrialización fue la preparación para la guerra, principalmente debido a la desconfianza en el mundo capitalista exterior. [120] Como resultado, la URSS se transformó de una economía en gran parte agraria en una gran potencia industrial, abriendo el camino para su surgimiento como superpotencia después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial . [121] La guerra causó una gran devastación de la economía y la infraestructura soviéticas, que requirieron una reconstrucción masiva. [122]

A principios de la década de 1940, la economía soviética se había vuelto relativamente autosuficiente ; durante la mayor parte del período hasta la creación del Comecon , solo una pequeña parte de los productos nacionales se comercializaba internacionalmente. [123] Después de la creación del Bloque del Este, el comercio exterior aumentó rápidamente. Sin embargo, la influencia de la economía mundial en la URSS estaba limitada por los precios internos fijos y un monopolio estatal sobre el comercio exterior . [124] Los granos y las manufacturas de consumo sofisticadas se convirtieron en importantes artículos de importación desde alrededor de la década de 1960. [123] Durante la carrera armamentista de la Guerra Fría, la economía soviética se vio agobiada por los gastos militares, fuertemente presionados por una poderosa burocracia dependiente de la industria armamentística. Al mismo tiempo, la URSS se convirtió en el mayor exportador de armas al Tercer Mundo . Una parte de los recursos soviéticos durante la Guerra Fría se asignaron en ayuda a los estados alineados con la Unión Soviética. [123] El presupuesto militar de la Unión Soviética en la década de 1970 fue gigantesco: representaba entre el 40 y el 60% de todo el presupuesto federal y el 15% del PIB de la URSS (13% en la década de 1980). [125]

Desde la década de 1930 hasta su disolución a fines de 1991, la forma en que operaba la economía soviética permaneció esencialmente sin cambios. La economía estaba dirigida formalmente por la planificación central , llevada a cabo por Gosplan y organizada en planes quinquenales . Sin embargo, en la práctica, los planes eran altamente agregados y provisionales, sujetos a la intervención ad hoc de los superiores. Todas las decisiones económicas críticas eran tomadas por el liderazgo político. Los recursos asignados y los objetivos del plan generalmente se denominaban en rublos en lugar de en bienes físicos. El crédito estaba desalentado, pero era generalizado. La asignación final de la producción se lograba mediante contrataciones relativamente descentralizadas y no planificadas. Aunque en teoría los precios se fijaban legalmente desde arriba, en la práctica a menudo se negociaban y los vínculos horizontales informales (por ejemplo, entre fábricas productoras) estaban muy extendidos. [119]

Varios servicios básicos , como la educación y la atención sanitaria, estaban financiados por el Estado. En el sector manufacturero, la industria pesada y la defensa tenían prioridad sobre los bienes de consumo . [126] Los bienes de consumo, en particular fuera de las grandes ciudades, solían ser escasos, de mala calidad y de variedad limitada. En la economía dirigida, los consumidores casi no tenían influencia en la producción y las demandas cambiantes de una población con ingresos crecientes no podían satisfacerse con suministros a precios rígidamente fijados. [127] Una segunda economía masiva no planificada creció a niveles bajos junto con la planificada, proporcionando algunos de los bienes y servicios que los planificadores no podían proporcionar. La legalización de algunos elementos de la economía descentralizada se intentó con la reforma de 1965. [ 119]

Aunque las estadísticas de la economía soviética son notoriamente poco fiables y su crecimiento económico difícil de estimar con precisión, [128] [129] según la mayoría de las estimaciones, la economía continuó expandiéndose hasta mediados de los años 1980. Durante los años 1950 y 1960, tuvo un crecimiento comparativamente alto y estaba alcanzando a Occidente. [130] Sin embargo, después de 1970, el crecimiento, aunque todavía positivo, disminuyó de manera constante mucho más rápida y consistente que en otros países, a pesar de un rápido aumento del stock de capital (la tasa de aumento de capital solo fue superada por Japón). [119]

En general, la tasa de crecimiento del ingreso per cápita en la Unión Soviética entre 1960 y 1989 fue ligeramente superior a la media mundial (basada en 102 países). [131] Un estudio de 1986 publicado en el American Journal of Public Health afirmó que, citando datos del Banco Mundial , el modelo soviético proporcionaba una mejor calidad de vida y desarrollo humano que las economías de mercado con el mismo nivel de desarrollo económico en la mayoría de los casos. [132] Según Stanley Fischer y William Easterly , el crecimiento podría haber sido más rápido. Según sus cálculos, el ingreso per cápita en 1989 debería haber sido el doble de lo que fue, considerando la cantidad de inversión, educación y población. Los autores atribuyen este pobre desempeño a la baja productividad del capital. [133] Steven Rosefielde afirma que el nivel de vida disminuyó debido al despotismo de Stalin. Si bien hubo una breve mejora después de su muerte, cayó en el estancamiento. [134]

En 1987, Mijail Gorbachov intentó reformar y revitalizar la economía con su programa de perestroika . Sus políticas relajaron el control estatal sobre las empresas, pero no lo reemplazaron por incentivos de mercado, lo que resultó en una fuerte caída de la producción. La economía, que ya sufría una reducción de los ingresos por exportación de petróleo , comenzó a colapsar. Los precios seguían siendo fijos y la propiedad seguía siendo en gran parte propiedad del Estado hasta después de la disolución del país. [119] [127] Durante la mayor parte del período posterior a la Segunda Guerra Mundial hasta su colapso, el PIB soviético ( PPA ) fue el segundo más grande del mundo , y el tercero durante la segunda mitad de la década de 1980, [135] aunque en términos per cápita , estaba detrás del de los países del Primer Mundo . [136] En comparación con los países con un PIB per cápita similar en 1928, la Unión Soviética experimentó un crecimiento significativo. [ cita requerida ]

En 1990, el país tenía un Índice de Desarrollo Humano de 0,920, lo que lo colocaba en la categoría de "alto" de desarrollo humano. Era el tercero más alto en el Bloque del Este, detrás de Checoslovaquia y Alemania Oriental , y el 25.º en el mundo de 130 países. [137]

La necesidad de combustible disminuyó en la Unión Soviética desde la década de 1970 hasta la de 1980, [138] tanto por rublo de producto social bruto como por rublo de producto industrial. Al principio, este descenso creció muy rápidamente, pero gradualmente se desaceleró entre 1970 y 1975. De 1975 a 1980, creció aún más lentamente, [ aclaración necesaria ] solo un 2,6%. [139] David Wilson, un historiador, creía que la industria del gas representaría el 40% de la producción de combustible soviética para fines de siglo. Su teoría no se hizo realidad debido al colapso de la URSS. [140] La URSS, en teoría, habría seguido teniendo una tasa de crecimiento económico del 2-2,5% durante la década de 1990 debido a los campos energéticos soviéticos. [ aclaración necesaria ] [141] Sin embargo, el sector energético enfrentó muchas dificultades, entre ellas el alto gasto militar del país y las relaciones hostiles con el Primer Mundo . [142]

En 1991, la Unión Soviética tenía una red de oleoductos de 82.000 kilómetros (51.000 millas) para petróleo crudo y otros 206.500 kilómetros (128.300 millas) para gas natural. [143] Se exportaban petróleo y productos derivados del petróleo, gas natural, metales, madera, productos agrícolas y una variedad de bienes manufacturados, principalmente maquinaria, armas y equipo militar. [144] En las décadas de 1970 y 1980, la URSS dependía en gran medida de las exportaciones de combustibles fósiles para obtener divisas . [123] En su apogeo en 1988, fue el mayor productor y el segundo mayor exportador de petróleo crudo, superado solo por Arabia Saudita . [145]

La Unión Soviética puso gran énfasis en la ciencia y la tecnología dentro de su economía, [146] [147] sin embargo, los éxitos soviéticos más notables en tecnología, como la producción del primer satélite espacial del mundo , generalmente fueron responsabilidad de los militares. [126] Lenin creía que la URSS nunca superaría al mundo desarrollado si permanecía tan tecnológicamente atrasada como lo estaba en su fundación. Las autoridades soviéticas demostraron su compromiso con la creencia de Lenin desarrollando redes masivas, organizaciones de investigación y desarrollo. A principios de la década de 1960, los soviéticos otorgaron el 40% de los doctorados en química a mujeres, en comparación con solo el 5% en los Estados Unidos. [148] En 1989, los científicos soviéticos se encontraban entre los especialistas mejor capacitados del mundo en varias áreas, como la física energética, áreas seleccionadas de la medicina, las matemáticas, la soldadura y las tecnologías militares. Debido a la rígida planificación estatal y la burocracia , los soviéticos permanecieron muy atrasados tecnológicamente en química, biología y computadoras en comparación con el Primer Mundo . El gobierno soviético se opuso y persiguió a los genetistas en favor del lysenkoísmo , una pseudociencia rechazada por la comunidad científica en la Unión Soviética y en el extranjero, pero apoyada por los círculos internos de Stalin. Implementada en la URSS y China, resultó en una reducción de los rendimientos de los cultivos y se cree ampliamente que contribuyó a la Gran Hambruna China . [149] La Unión Soviética también tenía más científicos e ingenieros , en relación con la población mundial, que cualquier otro país importante debido a los fuertes niveles de apoyo estatal a los desarrollos científicos en la década de 1980. [150]

Bajo la administración Reagan , el Proyecto Sócrates determinó que la Unión Soviética abordaba la adquisición de ciencia y tecnología de una manera radicalmente diferente a la que utilizaba Estados Unidos. En el caso de Estados Unidos, se estaba utilizando la priorización económica para la investigación y el desarrollo autóctonos como medio para adquirir ciencia y tecnología tanto en el sector privado como en el público. En contraste, la URSS estaba maniobrando ofensiva y defensivamente en la adquisición y uso de la tecnología mundial, para aumentar la ventaja competitiva que adquirían de la tecnología mientras impedían que Estados Unidos adquiriera una ventaja competitiva. Sin embargo, la planificación basada en la tecnología se ejecutaba de una manera centralizada y centrada en el gobierno que obstaculizaba en gran medida su flexibilidad. Esto fue explotado por Estados Unidos para socavar la fuerza de la Unión Soviética y así fomentar su reforma. [151] [152] [153]

A finales de la década de 1950, la URSS construyó el primer satélite , el Sputnik 1 , que marcó el inicio de la carrera espacial , una competencia para lograr una capacidad superior de vuelo espacial con los Estados Unidos. [154] A esto le siguieron otros satélites exitosos, en particular el Sputnik 5 , donde se enviaron perros de prueba al espacio. El 12 de abril de 1961, la URSS lanzó el Vostok 1 , que transportó a Yuri Gagarin , convirtiéndolo en el primer humano en ser lanzado al espacio y completar un viaje espacial. [155] Los primeros planes para transbordadores espaciales y estaciones orbitales se elaboraron en oficinas de diseño soviéticas, pero las disputas personales entre los diseñadores y la gerencia impidieron su desarrollo.

En cuanto al programa Luna , la URSS sólo tenía lanzamientos de naves espaciales automatizadas sin naves espaciales tripuladas, pasando por alto la parte "Luna" de la Carrera Espacial , que fue ganada por los estadounidenses . La reacción del público soviético al alunizaje estadounidense fue mixta. El gobierno soviético limitó la divulgación de información al respecto, lo que afectó la reacción. Una parte de la población no le prestó atención y otra parte se enojó. [156] [157]

En la década de 1970 surgieron propuestas específicas para el diseño de un transbordador espacial, pero las deficiencias, especialmente en la industria electrónica (sobrecalentamiento rápido de la electrónica), lo pospusieron hasta finales de la década de 1980. El primer transbordador, el Buran , voló en 1988, pero sin tripulación humana. Otro, el Ptichka , soportó una construcción prolongada y fue cancelado en 1991. Para su lanzamiento al espacio, existe hoy en día un cohete superpotente sin uso, el Energia , que es el más poderoso del mundo. [158]

A finales de los años 1980, la Unión Soviética construyó la estación orbital Mir . Se construyó sobre la base de la construcción de las estaciones Salyut y su única función era la de realizar tareas de investigación de carácter civil. [159] [160] La Mir fue la única estación orbital en funcionamiento entre 1986 y 1998. Poco a poco, se le fueron añadiendo otros módulos, incluidos los estadounidenses. Sin embargo, la estación se deterioró rápidamente tras un incendio a bordo, por lo que en 2001 se decidió llevarla a la atmósfera, donde se quemó. [159]

El transporte era un componente vital de la economía del país. La centralización económica de finales de los años 1920 y 1930 condujo al desarrollo de infraestructura a gran escala, en particular al establecimiento de Aeroflot , una empresa de aviación . [161] El país tenía una amplia variedad de modos de transporte por tierra, agua y aire. [143] Sin embargo, debido al mantenimiento inadecuado, gran parte del transporte por carretera, agua y aviación civil soviética estaba obsoleto y tecnológicamente atrasado en comparación con el Primer Mundo. [162]

El transporte ferroviario soviético era el más grande y más utilizado del mundo; [162] también estaba mejor desarrollado que la mayoría de sus homólogos occidentales. [163] A finales de la década de 1970 y principios de la de 1980, los economistas soviéticos pedían la construcción de más carreteras para aliviar algunas de las cargas de los ferrocarriles y mejorar el presupuesto del gobierno soviético . [164] La red de calles y la industria automotriz [165] seguían subdesarrolladas, [166] y los caminos de tierra eran comunes fuera de las principales ciudades. [167] Los proyectos de mantenimiento soviéticos demostraron ser incapaces de cuidar incluso las pocas carreteras que tenía el país. A principios y mediados de la década de 1980, las autoridades soviéticas intentaron resolver el problema de las carreteras ordenando la construcción de otras nuevas. [167] Mientras tanto, la industria automotriz estaba creciendo a un ritmo más rápido que la construcción de carreteras. [168] La red de carreteras subdesarrollada provocó una creciente demanda de transporte público. [169]

A pesar de las mejoras, varios aspectos del sector del transporte seguían plagados de problemas debido a una infraestructura obsoleta, falta de inversión, corrupción y malas decisiones. Las autoridades soviéticas no pudieron satisfacer la creciente demanda de infraestructura y servicios de transporte. [170]

La marina mercante soviética era una de las más grandes del mundo. [143]

El exceso de muertes durante la Primera Guerra Mundial y la Guerra Civil Rusa (incluida la hambruna de 1921-1922 que fue provocada por las políticas de comunismo de guerra de Lenin ) [171] ascendió a un total combinado de 18 millones, [172] unos 10 millones en la década de 1930, [173] y más de 20 millones en 1941-1945. La población soviética de posguerra fue de 45 a 50 millones menor de lo que habría sido si el crecimiento demográfico anterior a la guerra hubiera continuado. [174] Según Catherine Merridale , "... una estimación razonable situaría el número total de muertes en exceso durante todo el período en torno a los 60 millones". [175]

La tasa de natalidad de la URSS disminuyó de 44,0 por mil en 1926 a 18,0 en 1974, debido principalmente a la creciente urbanización y al aumento de la edad promedio de los matrimonios. La tasa de mortalidad también mostró una disminución gradual, de 23,7 por mil en 1926 a 8,7 en 1974. En general, las tasas de natalidad de las repúblicas del sur de Transcaucasia y Asia central fueron considerablemente más altas que las de las partes septentrionales de la Unión Soviética, y en algunos casos incluso aumentaron en el período posterior a la Segunda Guerra Mundial, un fenómeno atribuido en parte a tasas de urbanización más lentas y matrimonios tradicionalmente más tempranos en las repúblicas del sur. [176] La Europa soviética avanzó hacia una fecundidad por debajo del nivel de reemplazo , mientras que el Asia central soviética continuó exhibiendo un crecimiento demográfico muy por encima de la fecundidad del nivel de reemplazo. [177]

A finales de los años 1960 y en los años 1970 se produjo una reversión de la trayectoria descendente de la tasa de mortalidad en la URSS, y fue especialmente notable entre los hombres en edad de trabajar, pero también prevaleció en Rusia y otras áreas predominantemente eslavas del país. [178] Un análisis de los datos oficiales de finales de los años 1980 mostró que después de empeorar a finales de los años 1970 y principios de los años 1980, la mortalidad de adultos comenzó a mejorar de nuevo. [179] La tasa de mortalidad infantil aumentó de 24,7 en 1970 a 27,9 en 1974. Algunos investigadores consideraron que el aumento fue en su mayoría real, una consecuencia del empeoramiento de las condiciones y los servicios de salud. [180] Los funcionarios soviéticos no explicaron ni defendieron los aumentos de la mortalidad tanto de adultos como de niños, y el gobierno soviético dejó de publicar todas las estadísticas de mortalidad durante diez años. Los demógrafos y especialistas en salud soviéticos guardaron silencio sobre el aumento de la mortalidad hasta fines de la década de 1980, cuando se reanudó la publicación de datos de mortalidad y los investigadores pudieron profundizar en las causas reales. [181]

La Unión Soviética impuso un fuerte control sobre el crecimiento de las ciudades, impidiendo que algunas alcanzaran su máximo potencial mientras que promovía otras. [182] [183]

Durante toda su existencia, las ciudades más pobladas fueron Moscú y Leningrado (ambas en la RSFS de Rusia ), con el tercer puesto ocupado por Kiev ( RSS de Ucrania ). En sus inicios, el Top 5 lo completaban Járkov (RSS de Ucrania) y Bakú ( RSS de Azerbaiyán ), pero, a finales de siglo, Tashkent ( RSS de Uzbekistán ), que había asumido la posición de capital del Asia Central soviética, había ascendido al cuarto lugar. Otra ciudad que vale la pena mencionar es Minsk ( RSS de Bielorrusia ), que experimentó un rápido crecimiento durante el siglo XX, pasando de ser la 32.ª más poblada de la unión a la 7.ª. [183] [184] [185]

Bajo Lenin, el estado asumió compromisos explícitos para promover la igualdad entre hombres y mujeres. Muchas de las primeras feministas rusas y mujeres trabajadoras rusas comunes participaron activamente en la Revolución, y muchas más se vieron afectadas por los eventos de ese período y las nuevas políticas. A partir de octubre de 1918, el gobierno de Lenin liberalizó las leyes de divorcio y aborto, despenalizó la homosexualidad (volvió a ser penalizada en 1932), permitió la cohabitación e introdujo una serie de reformas. [186] Sin embargo, sin control de la natalidad , el nuevo sistema produjo muchos matrimonios rotos, así como innumerables niños fuera del matrimonio. [187] La epidemia de divorcios y aventuras extramatrimoniales creó dificultades sociales cuando los líderes soviéticos querían que la gente concentrara sus esfuerzos en hacer crecer la economía. Dar a las mujeres el control sobre su fertilidad también condujo a una caída precipitada de la tasa de natalidad, percibida como una amenaza para el poder militar de su país. En 1936, Stalin revocó la mayoría de las leyes liberales, marcando el comienzo de una era pronatalista que duró décadas. [188]

En 1917, Rusia se convirtió en la primera gran potencia en conceder a las mujeres el derecho al voto. [189] Después de las fuertes bajas en la Primera y Segunda Guerra Mundial, las mujeres superaban en número a los hombres en Rusia en una proporción de 4:3. [190] Esto contribuyó al papel más importante que desempeñaron las mujeres en la sociedad rusa en comparación con otras grandes potencias de la época.

Anatoly Lunacharsky se convirtió en el primer Comisario del Pueblo para la Educación de la Rusia Soviética. Al principio, las autoridades soviéticas pusieron gran énfasis en la eliminación del analfabetismo . Todos los niños zurdos fueron obligados a escribir con la mano derecha en el sistema escolar soviético. [191] [192] [193] [194] Las personas alfabetizadas fueron contratadas automáticamente como maestros. [ cita requerida ] Durante un corto período, se sacrificó la calidad por la cantidad. En 1940, Stalin pudo anunciar que se había eliminado el analfabetismo. A lo largo de la década de 1930, la movilidad social aumentó drásticamente, lo que se ha atribuido a las reformas en la educación. [195] Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el sistema educativo del país se expandió drásticamente, lo que tuvo un tremendo efecto. En la década de 1960, casi todos los niños tenían acceso a la educación, la única excepción eran los que vivían en áreas remotas. Nikita Khrushchev intentó hacer que la educación fuera más accesible, dejando en claro a los niños que la educación estaba estrechamente vinculada a las necesidades de la sociedad. La educación también adquirió importancia para el surgimiento del Hombre Nuevo . [196] Los ciudadanos que entraban directamente a la fuerza laboral tenían el derecho constitucional a un empleo y a una formación vocacional gratuita .

El sistema educativo estaba altamente centralizado y era universalmente accesible para todos los ciudadanos, con acciones afirmativas para los solicitantes de naciones asociadas con el atraso cultural . Sin embargo, como parte de una política antisemita general , se aplicó una cuota judía no oficial [ ¿cuándo? ] en las principales instituciones de educación superior al someter a los solicitantes judíos a exámenes de ingreso más severos. [197] [198] [199] [200] La era de Brezhnev también introdujo una regla que requería que todos los solicitantes universitarios presentaran una referencia del secretario del partido Komsomol local. [201] Según las estadísticas de 1986, el número de estudiantes de educación superior por cada 10.000 habitantes era de 181 en la URSS, en comparación con 517 en los EE. UU. [202]

La Unión Soviética era un país étnicamente diverso, con más de 100 grupos étnicos distintos. La población total del país se estimó en 293 millones en 1991. Según una estimación de 1990, la mayoría de la población eran rusos (50,78%), seguidos de ucranianos (15,45%) y uzbekos (5,84%). [203] En general, en 1989 la demografía étnica del país mostró que el 69,8% era eslavo oriental , el 17,5% era turco , el 1,6% eran armenios , el 1,6% eran bálticos , el 1,5% eran fineses , el 1,5% eran tayikos , el 1,4% eran georgianos , el 1,2% eran moldavos y el 4,1% pertenecían a otros grupos étnicos diversos. [204]

Todos los ciudadanos de la URSS tenían su propia afiliación étnica. La etnia de una persona era elegida a la edad de dieciséis años por los padres del niño. [205] Si los padres no estaban de acuerdo, al niño se le asignaba automáticamente la etnia del padre. En parte debido a las políticas soviéticas, algunos de los grupos étnicos minoritarios más pequeños fueron considerados parte de los más grandes, como los mingrelianos de Georgia , que fueron clasificados con los georgianos lingüísticamente relacionados . [206] Algunos grupos étnicos se asimilaron voluntariamente, mientras que otros fueron traídos por la fuerza. Los rusos, bielorrusos y ucranianos, que eran todos eslavos orientales y ortodoxos, compartían estrechos lazos culturales, étnicos y religiosos, mientras que otros grupos no. Con múltiples nacionalidades viviendo en el mismo territorio, se desarrollaron antagonismos étnicos a lo largo de los años. [207] [ la neutralidad está en disputa ]

En los órganos legislativos participaban miembros de diversas etnias. Los órganos de poder como el Politburó, el Secretariado del Comité Central, etc., eran formalmente étnicamente neutrales, pero en realidad los rusos étnicos estaban sobrerrepresentados, aunque también había dirigentes no rusos en la cúpula soviética , como Iósif Stalin , Grigori Zinóviev , Nikolai Podgorni o Andréi Gromiko . Durante la era soviética, un número significativo de rusos y ucranianos étnicos emigraron a otras repúblicas soviéticas, y muchos de ellos se establecieron allí. Según el último censo de 1989, la «diáspora» rusa en las repúblicas soviéticas había alcanzado los 25 millones. [208]

In 1917, before the revolution, health conditions were significantly behind those of developed countries. As Lenin later noted, "Either the lice will defeat socialism, or socialism will defeat the lice".[209] The Soviet health care system was conceived by the People's Commissariat for Health in 1918. Under the Semashko model, health care was to be controlled by the state and would be provided to its citizens free of charge, a revolutionary concept at the time. Article 42 of the 1977 Soviet Constitution gave all citizens the right to health protection and free access to any health institutions in the USSR. Before Leonid Brezhnev became general secretary, the Soviet healthcare system was held in high esteem by many foreign specialists. This changed, however, from Brezhnev's accession and Mikhail Gorbachev's tenure as leader, during which the health care system was heavily criticized for many basic faults, such as the quality of service and the unevenness in its provision.[210] Minister of Health Yevgeniy Chazov, during the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, while highlighting such successes as having the most doctors and hospitals in the world, recognized the system's areas for improvement and felt that billions of rubles were squandered.[211]

After the revolution, life expectancy for all age groups went up. This statistic in itself was seen by some that the socialist system was superior to the capitalist system. These improvements continued into the 1960s when statistics indicated that the life expectancy briefly surpassed that of the United States. Life expectancy started to decline in the 1970s, possibly because of alcohol abuse. At the same time, infant mortality began to rise. After 1974, the government stopped publishing statistics on the matter. This trend can be partly explained by the number of pregnancies rising drastically in the Asian part of the country where infant mortality was the highest while declining markedly in the more developed European part of the Soviet Union.[212]

Soviet dental technology and dental health were considered notoriously bad. In 1991, the average 35-year-old had 12 to 14 cavities, fillings or missing teeth. Toothpaste was often not available, and toothbrushes did not conform to standards of modern dentistry.[213][214]

Under Lenin, the government gave small language groups their own writing systems.[215] The development of these writing systems was highly successful, even though some flaws were detected. During the later days of the USSR, countries with the same multilingual situation implemented similar policies. A serious problem when creating these writing systems was that the languages differed dialectally greatly from each other.[216] When a language had been given a writing system and appeared in a notable publication, it would attain 'official language' status. There were many minority languages which never received their own writing system; therefore, their speakers were forced to have a second language.[217] There are examples where the government retreated from this policy, most notably under Stalin where education was discontinued in languages that were not widespread. These languages were then assimilated into another language, mostly Russian.[218] During World War II, some minority languages were banned, and their speakers accused of collaborating with the enemy.[219]

As the most widely spoken of the Soviet Union's many languages, Russian de facto functioned as an official language, as the 'language of interethnic communication' (Russian: язык межнационального общения), but only assumed the de jure status as the official national language in 1990.[220]

Christianity and Islam had the highest number of adherents among the religious citizens.[221] Eastern Christianity predominated among Christians, with Russia's traditional Russian Orthodox Church being the largest Christian denomination. About 90% of the Soviet Union's Muslims were Sunnis, with Shias being concentrated in the Azerbaijan SSR.[221] Smaller groups included Roman Catholics, Jews, Buddhists, and a variety of Protestant denominations (especially Baptists and Lutherans).[221]

Religious influence had been strong in the Russian Empire. The Russian Orthodox Church enjoyed a privileged status as the church of the monarchy and took part in carrying out official state functions.[222] The immediate period following the establishment of the Soviet state included a struggle against the Orthodox Church, which the revolutionaries considered an ally of the former ruling classes.[223]

In Soviet law, the 'freedom to hold religious services' was constitutionally guaranteed, although the ruling Communist Party regarded religion as incompatible with the Marxist spirit of scientific materialism.[223] In practice, the Soviet system subscribed to a narrow interpretation of this right, and in fact used a range of official measures to discourage religion and curb the activities of religious groups.[223]

The 1918 Council of People's Commissars decree establishing the Russian SFSR as a secular state also decreed that 'the teaching of religion in all [places] where subjects of general instruction are taught, is forbidden. Citizens may teach and may be taught religion privately.'[224] Among further restrictions, those adopted in 1929 included express prohibitions on a range of church activities, including meetings for organized Bible study.[223] Both Christian and non-Christian establishments were shut down by the thousands in the 1920s and 1930s. By 1940, as many as 90% of the churches, synagogues, and mosques that had been operating in 1917 were closed; the majority of them were demolished or re-purposed for state needs with little concern for their historic and cultural value.[225]

More than 85,000 Orthodox priests were shot in 1937 alone.[226] Only a twelfth of the Russian Orthodox Church's priests were left functioning in their parishes by 1941.[227] In the period between 1927 and 1940, the number of Orthodox Churches in Russia fell from 29,584 to less than 500 (1.7%).[228]

The Soviet Union was officially a secular state,[229][230] but a 'government-sponsored program of forced conversion to atheism' was conducted under the doctrine of state atheism.[231][232][233] The government targeted religions based on state interests, and while most organized religions were never outlawed, religious property was confiscated, believers were harassed, and religion was ridiculed while atheism was propagated in schools.[234] In 1925, the government founded the League of Militant Atheists to intensify the propaganda campaign.[235] Accordingly, although personal expressions of religious faith were not explicitly banned, a strong sense of social stigma was imposed on them by the formal structures and mass media, and it was generally considered unacceptable for members of certain professions (teachers, state bureaucrats, soldiers) to be openly religious. While persecution accelerated following Stalin's rise to power, a revival of Orthodoxy was fostered by the government during World War II and the Soviet authorities sought to control the Russian Orthodox Church rather than liquidate it. During the first five years of Soviet power, the Bolsheviks executed 28 Russian Orthodox bishops and over 1,200 Russian Orthodox priests. Many others were imprisoned or exiled. Believers were harassed and persecuted. Most seminaries were closed, and the publication of most religious material was prohibited. By 1941, only 500 churches remained open out of about 54,000 in existence before World War I.

Convinced that religious anti-Sovietism had become a thing of the past, and with the looming threat of war, the Stalin administration began shifting to a more moderate religion policy in the late 1930s.[236] Soviet religious establishments overwhelmingly rallied to support the war effort during World War II. Amid other accommodations to religious faith after the German invasion, churches were reopened. Radio Moscow began broadcasting a religious hour, and a historic meeting between Stalin and Orthodox Church leader Patriarch Sergius of Moscow was held in 1943. Stalin had the support of the majority of the religious people in the USSR even through the late 1980s.[236] The general tendency of this period was an increase in religious activity among believers of all faiths.[237]

Under Nikita Khrushchev, the state leadership clashed with the churches in 1958–1964, a period when atheism was emphasized in the educational curriculum, and numerous state publications promoted atheistic views.[236] During this period, the number of churches fell from 20,000 to 10,000 from 1959 to 1965, and the number of synagogues dropped from 500 to 97.[238] The number of working mosques also declined, falling from 1,500 to 500 within a decade.[238]

Religious institutions remained monitored by the Soviet government, but churches, synagogues, temples, and mosques were all given more leeway in the Brezhnev era.[239] Official relations between the Orthodox Church and the government again warmed to the point that the Brezhnev government twice honored Orthodox Patriarch Alexy I with the Order of the Red Banner of Labour.[240] A poll conducted by Soviet authorities in 1982 recorded 20% of the Soviet population as 'active religious believers.'[241]

The culture of the Soviet Union passed through several stages during the USSR's existence. During the first decade following the revolution, there was relative freedom and artists experimented with several different styles to find a distinctive Soviet style of art. Lenin wanted art to be accessible to the Russian people. On the other hand, hundreds of intellectuals, writers, and artists were exiled or executed, and their work banned, such as Nikolay Gumilyov who was shot for alleged conspiracy against the Bolsheviks, and Yevgeny Zamyatin.[242]

The government encouraged a variety of trends. In art and literature, numerous schools, some traditional and others radically experimental, proliferated. Communist writers Maxim Gorky and Vladimir Mayakovsky were active during this time. As a means of influencing a largely illiterate society, films received encouragement from the state, and much of director Sergei Eisenstein's best work dates from this period.

During Stalin's rule, the Soviet culture was characterized by the rise and domination of the government-imposed style of socialist realism, with all other trends being severely repressed, with rare exceptions, such as Mikhail Bulgakov's works. Many writers were imprisoned and killed.[243]

Following the Khrushchev Thaw, censorship was diminished. During this time, a distinctive period of Soviet culture developed, characterized by conformist public life and an intense focus on personal life. Greater experimentation in art forms was again permissible, resulting in the production of more sophisticated and subtly critical work. The government loosened its emphasis on socialist realism; thus, for instance, many protagonists of the novels of author Yury Trifonov concerned themselves with problems of daily life rather than with building socialism. Underground dissident literature, known as samizdat, developed during this late period. In architecture, the Khrushchev era mostly focused on functional design as opposed to the highly decorated style of Stalin's epoch. In music, in response to the increasing popularity of forms of popular music like jazz in the West, many jazz orchestras were permitted throughout the USSR, notably the Melodiya Ensemble, named after the principle record label in the USSR.

In the second half of the 1980s, Gorbachev's policies of perestroika and glasnost significantly expanded freedom of expression throughout the country in the media and the press.[244]

In summer of 1923 in Moscow was established the Proletarian Sports Society "Dynamo" as a sports organization of Soviet secret police Cheka.

On 13 July 1925 the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) adopted a statement "About the party's tasks in sphere of physical culture". In the statement was determined the role of physical culture in Soviet society and the party's tasks in political leadership of physical culture movement in the country.

The Soviet Olympic Committee formed on 21 April 1951, and the IOC recognized the new body in its 45th session. In the same year, when the Soviet representative Konstantin Andrianov became an IOC member, the USSR officially joined the Olympic Movement. The 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki thus became first Olympic Games for Soviet athletes. The Soviet Union was the biggest rival to the United States at the Summer Olympics, winning six of its nine appearances at the games and also topping the medal tally at the Winter Olympics six times. The Soviet Union's Olympics success has been attributed to its large investment in sports to demonstrate its superpower image and political influence on a global stage.[245]

The Soviet Union national ice hockey team won nearly every world championship and Olympic tournament between 1954 and 1991 and never failed to medal in any International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) tournament in which they competed.

Soviet Olympic team was notorious for skirting the edge of amateur rules. All Soviet athletes held some nominal jobs, but were in fact state-sponsored and trained full-time. According to many experts, that gave the Soviet Union a huge advantage over the United States and other Western countries, whose athletes were students or real amateurs.[246][247] Indeed, the Soviet Union monopolized the top place in the medal standings after 1968, and, until its collapse, placed second only once, in the 1984 Winter games, after another Eastern bloc nation, the GDR. Amateur rules were relaxed only in the late 1980s and were almost completely abolished in the 1990s, after the fall of the USSR.[245][248]