Occurring between July 2011 and mid-2012, a severe drought affected the entire East African region.[7] Said to be "the worst in 60 years",[8] the drought caused a severe food crisis across Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia and Kenya that threatened the livelihood of 9.5 million people.[6] Many refugees from southern Somalia fled to neighboring Kenya and Ethiopia, where crowded, unsanitary conditions together with severe malnutrition led to a large number of deaths.[9] Other countries in East Africa, including Sudan, South Sudan and parts of Uganda, were also affected by a food crisis.[8][10][11][12]

According to FAO-Somalia, the food crisis in Somalia primarily affected farmers in the south rather than the northern pastoralists.[13] Human Rights Watch (HRW) consequently noted that most of the displaced persons belonged to the agro-pastoral Rahanweyn clan and the agricultural Bantu ethnic minority group.[14] On 20 July, the United Nations officially declared famine in two regions in the southern part of the country (IPC Phase 5), the first time a famine had been declared in the region by the UN in nearly thirty years.[15][16] Tens of thousands of people are believed to have died in southern Somalia before famine was declared.[15] This was mainly a result of Western governments preventing aid from reaching affected areas in an attempt to weaken the Al-Shabaab militant group, against whom they were engaged.[17][18]

Although fighting disrupted aid delivery in some areas, a scaling up of relief operations in mid-November had unexpectedly significantly reduced malnutrition and mortality rates in southern Somalia, prompting the UN to downgrade the humanitarian situation in the Bay, Bakool and Lower Shabele regions from famine to emergency levels.[19] According to the Lutheran World Federation, military activities in the country's southern conflict zones had also by early December 2011 greatly reduced the movement of migrants.[20] By February 2012, several thousand people had also begun returning to their homes and farms.[21] In addition, humanitarian access to rebel-controlled areas had improved and rainfall had surpassed expectations, improving the prospects of a good harvest in early 2012.[19]

By January 2012, the food crisis in southern Somalia was no longer at emergency levels according to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).[22] The UN indicated in February 2012 that indirect data from health and relief centers pointed to improved general conditions from August 2011. The UN also announced that the famine in southern Somalia was over.[23] However, FEWS NET indicated that Emergency (IPC Phase 4) levels of food insecurity persisted through March in several areas on account of crop flooding and ongoing military operations in these areas, which restricted humanitarian access, trade and movement.[24]

Aid agencies subsequently shifted their emphasis to recovery efforts, including digging irrigation canals and distributing plant seeds.[23] Long-term strategies by national governments in conjunction with development agencies were said to offer the most sustainable results.[25]

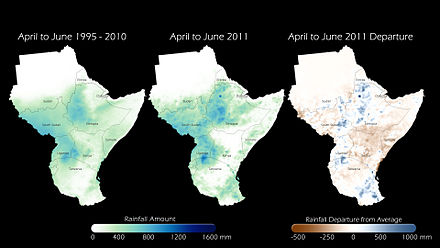

Weather conditions over the Pacific, including an unusually strong La Niña, interrupted seasonal rains for two consecutive seasons. The rains failed in 2011 in Kenya and Ethiopia, and for the previous two years in Somalia.[7][26] In many areas, the precipitation rate during the main rainy season from April to June, the primary season, was less than 30% of the average of 1995–2010.[27] The lack of rain led to crop failure and widespread loss of livestock, as high as 40–60% in some areas, which decreased milk production as well as exacerbating a poor harvest. As a result, cereal prices rose to record levels while livestock prices and wages fell, reducing purchasing power across the region.[28] Rains were also not expected to return until September of the year.[7] The crisis is compounded by rebel activity around southern Somalia from the Al-Shabaab group.[11]

The head of the United States Agency for International Development, Rajiv Shah, stated that climate change contributed to the severity of the crisis. "There's no question that hotter and drier growing conditions in sub-Saharan Africa have reduced the resiliency of these communities."[29] On the other hand, two experts with the International Livestock Research Institute suggested that it was premature to blame climate change for the drought. Indeed, the majority of climate models had predicted a long-term increase in rain for this area.[30] While there is consensus that a particularly strong La Niña contributed to the intensity of the drought, the relationship between La Niña and climate change is not well-established.[31]

The failure of the international community to heed the early warning system was criticized for leading to a worsening of the crisis. The Famine Early Warning Systems Network, financed by U.S.A.I.D., anticipated the crisis as early as August 2010, and by January 2011, the American ambassador to Kenya declared a disaster and called for urgent assistance. On 7 June 2011, FEWS NET declared that the crisis was "the most severe food security emergency in the world today, and the current humanitarian response is inadequate to prevent further deterioration".[32] The UN later announced on 28 June that 12 million people in the East Africa region were affected by the drought and that some areas were on the brink of famine, with many displaced in search of water and food.[33] Oxfam's humanitarian director Jane Cocking stated that "This is a preventable disaster and solutions are possible".[34] Suzanne Dvorak, the chief executive of Save the Children, wrote that "politicians and policymakers in rich countries are often skeptical about taking preventative action because they think aid agencies are inflating the problem. Developing country governments are embarrassed about being seen as unable to feed their people. [...] these children are wasting away in a disaster that we could—and should—have prevented."[35] Soon after a famine was declared in parts of southern Somalia. Oxfam also charged several European governments of "wilful neglect" over the crisis.[36] It issued a statement saying that "The warning signs have been seen for months, and the world has been slow to act. Much greater long-term investment is needed in food production and basic development to help people cope with poor rains and ensure that this is the last famine in the region."[37]

On 20 July 2011, the UN declared a famine in the Lower Shabelle and Bakool, two regions of southern Somalia.[15] On 3 August, famine was further declared in the Balcad and Cadale districts in Middle Shabelle as well as the IDP settlements in Mogadishu and Afgooye in response to data from the UN's food security and nutrition analysis unit.[28][38] According to the UN, famine would spread to all eight regions of southern Somalia in four to six weeks due to inadequate humanitarian response caused both by ongoing access restrictions and funding gaps.[28] The Economist also reported that widespread famine would soon occur across the entire Horn of Africa, "a situation...not seen for 25 years".[34]

According to Luca Alivoni, the head of FAO-Somalia, the food crisis in Somalia has primarily affected farmers in the south rather than the northern pastoralists since farmers often stay behind on their land plots to "protect their crops", while herders move with their livestock to pastureland.[13]

On 20 July 2011, staple prices were at 68% over the five-year average,[39] including increases of up to 240% in southern Somalia, 117% in south-eastern Ethiopia, and 58% in northern Kenya.[27][35] In early July, the UN World Food Programme said that it expected 10 million people across the Horn of Africa region to need food aid, revising upward an earlier estimate of 6 million. Later in the month, the UN further updated the figure to 12 million, with 2.8 million in southern Somalia alone, which was the most affected area. On 3 August, the UN declared famine in three other regions of southern Somalia, citing worsening conditions and inadequate humanitarian response. Famine was expected to spread across all regions of the south in the following four to six weeks.[28] On 5 Sep, the UN added the entire Bay region in Somalia to the list of famine-stricken areas.[40][41] The UN has conducted several airlifts of supplies in addition to on-the-ground assistance,[42] but humanitarian response to the crisis has been hindered by a severe lack of funding for international aid coupled with security issues in the region.[15][43][44] As of September 2011, 63 percent of the UN's appeal for $2.5 billion (US) in humanitarian assistance has been financed.[26]

The crisis was expected to worsen in the following months, peaking in August and September, with large-scale assistance needed until at least December 2011.[45] Torrential rains also exacerbated the situation in Mogadishu by destroying makeshift homes. Tens of thousands of southern Somalia's internally displaced people were consequently left out in the cold.[46]

In addition, the Kenyan Red Cross warns of a looming humanitarian crisis in the northwestern Turkana region of Kenya, which borders South Sudan. According to officials with the aid agency, over three-fourths of the area's population is now in dire need of food supplies. Malnutrition levels are also at their highest.[47] As a consequence, schools in the region have shut down "because there is no food for the children".[48] About 385,000 children in these neglected parts of Kenya are already malnourished, along with 90,000 pregnant and breast feeding women. A further 3.5 million people in Kenya are estimated to be at risk of malnutrition.[49]

In August 2012, an estimated 87,000 people in the Taita-Taveta District of Kenya were reportedly affected by famine, a situation attributed to a combination of wildlife invasions and drought. Large herds of elephants and monkeys overran farms in the district's lowland and highland areas, respectively, ruining thousands of acres of crops.[50] Local residents, about 67,000 of whom were receiving food aid, also accused the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) of intentionally moving the monkeys to the district. However, this was denied by the KWS.[50]

Food shortages have also been reported in northern and eastern Uganda. The Karamoja region and the Bulambuli district, in particular, are among the worst hit areas, with an estimated 1.2 million Ugandans affected. The Ugandan government has also indicated that as of September 2011, acute deficits in foodstuffs are expected in 35 of the country's districts.[51]

Although fighting disrupted aid delivery in some areas, a scaling up of relief operations in mid-November had unexpectedly significantly reduced malnutrition and mortality rates in southern Somalia, prompting the UN to downgrade the humanitarian situation in the Bay, Bakool and Lower Shabele regions from famine to emergency levels. Humanitarian access to rebel-controlled areas had also improved and rainfall had surpassed expectations, improving the prospects of a good harvest in early 2012.[19] Despite the re-imposition of blocks by the militants on the delivery of relief supplies in some areas under their control, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reported in January 2012 that the food crisis in southern Somalia was by then no longer at emergency levels.[22] Although security restrictions precluded the collection of updated information in December/January for a few regions in southern Somalia, the UN indicated in February 2012 that indirect data from health and relief centers pointed to improved general conditions from August 2011. The UN also announced that the famine in southern Somalia was over.[23] However, FEWS NET indicated that Emergency (IPC Phase 4) levels of food insecurity would persist through March in the southern riverine parts of the Juba and Gedo regions, the south-central agropastoral zones of Hiran and Middle Shebele, the southeast pastoral sections of Shebele and Juba, and the north-central Coastal Deeh on account of crop flooding and ongoing military operations in these areas that have restricted humanitarian access, trade and movement.[24]

The UN also warned that, in a worst-case scenario of poor rains and price instability, conditions would remain at crisis level for about 31% of the population in limited-access areas until the August harvest season. In the most-likely scenario, the FSNAU and FEWS NET expect the April–June rains to be average. Ameliorated food security outcomes are also expected on account of the start of the Deyr harvest, which reached 200% of the post-war mean and is predicted to be significantly higher than usual. Except for the Juba region, where damage from flooding and limitations on trade have kept cereal prices high, the above average harvest has led to a substantial drop in overall cereal prices in the south's vulnerable regions. This has resulted in more agricultural wage labour opportunities for underprivileged agropastoral households and increased the purchasing power of pastoralists. With the exception of some coastal areas, where a little under 95,000 pastoralists have yet to recover their herd sizes from the drought and consequently still require emergency livelihood assistance (IPC Phase 4), the abundant rainfall in most parts of central and northern Somalia has replenished pastureland and also further boosted the purchasing power of local herders. With the benefit of the current harvest likely to ebb in May, the UN stressed that continued multi-sectoral response is necessary to secure the recent gains made,[23][52] and that general humanitarian needs requiring international assistance would persist until at least September 2012.[53]

According to the Sudan Crop and Food Security Assessment Mission (CSFAM) for January 2012, due to subpar cereal production and increased cereal prices caused by intense conflict that has limited trade, humanitarian and population movements, an estimated 4.2 million people in Sudan are predicted to be in the Stressed (IPC Phase 3), Crisis and Emergency levels during the first three or four months of 2012. The number was previously estimated at 3.3 million people in December 2011, and is expected to especially affect the South Kordofan, North Darfur and Blue Nile states. Below average cereal production and a trade blockade imposed by Sudan have also extended food insecurity in South Sudan, with the northern and northeastern sections of the nation expected to be at Stressed and Crisis levels through March.[24]

Aid agencies have now shifted their emphasis to recovery efforts, including digging irrigation canals and distributing plant seeds.[23] Long-term strategies by national governments in conjunction with development agencies are believed to offer the most sustainable results.[25]

By 15 September, more than 920,000 refugees from Somalia had reportedly fled to neighboring countries, particularly Kenya and Ethiopia.[54] At the height of the crisis in June 2011, the UNHCR base in Dadaab, Kenya hosted at least 440,000 people in three refugee camps, though the maximum capacity was 90,000.[55] More than 1,500 refugees continued to arrive every day from southern Somalia, 80 per cent of whom were women and children.[56][57] UN High Commissioner for Refugees spokeswoman Melissa Fleming said that many people had died en route.[58] Within the camps, infant mortality had risen threefold in the few months leading up to July 2011. The overall mortality rate was 7.4 out of 10,000 per day, which was more than seven times as high as the "emergency" rate of 1 out of 10,000 per day.[9][59] There was an upsurge in sexual violence against women and girls, with the number of cases reported increasing by over 4 times. Incidents of sexual violence occurred primarily during travel to the refugee camps, with some cases reported in the camps themselves or as new refugees went in search for firewood.[57] This put them at high risk of acquiring HIV/AIDS.[39] According to UN representative Radhika Coomaraswamy, the food crisis had forced many women to leave their homes in search of assistance, where they were often without the protection of their family and clan.[60]

In July 2011, Dolo Odo, Ethiopia also hosted at least 110,000 refugees from Somalia, most of whom had arrived recently. The three camps at Bokolomanyo, Melkadida, and Kobe all exceeded their maximum capacity; one more camp was reportedly being built while another was planned in the future. Water shortage reportedly affected all the facilities.[39]

According to the Lutheran World Federation, military activities in the conflict zones of southern Somalia and a scaling up of relief operations had by early December 2011 greatly reduced the movement of migrants.[20] By February 2012, several thousand people had also begun returning to their homes and farms.[21]

In July 2011, measles cases broke out in the Dadaab camp, with 462 cases confirmed including 11 deaths.[11] Ethiopia and Kenya were also facing a severe measles epidemic, attributed in part to the refugee crisis, with over 17,500 cases reported in the first 6 months.[61][62] WHO statistics put the number of children that were then most at the risk of measles at 2 million.[62] The epidemic in Ethiopia may have led to an measles outbreak in the United States and other parts of the developed world.[62] The World Health Organization stated that "8.8 million people are at risk of malaria and 5 million of cholera" in Ethiopia, due to crowded, unsanitary conditions. Malnutrition rates among children in July also reached 30 percent in parts of Kenya and Ethiopia and over 50% in southern Somalia,[27][29][63] although the latter figure dropped to 36% by mid-September according to the Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit.[64] Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières) was also treating more than 10,000 severely malnourished children in its feeding centers and clinics.[65] In July 2011, the UN's food security and nutrition analysis unit announced that the situation in southern Somalia then met all three characteristics of widespread famine: a) more than 30 percent of children were suffering from acute malnutrition; b) more than two adults or four children were dying of hunger each day for every group of 10,000 people; and c) the population had access to less than 2,100 kilocalories of food and four liters of water per day.[38] In August, cholera was suspected in 181 deaths in Mogadishu, along with confirmed reports of several other outbreaks elsewhere in Somalia, thus raising fears of tragedy for a severely weakened population.[66] In mid-November, the office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) also announced that 60 cholera cases, with 10 lab-confirmed and one fatality, had hit the Dadaab refugee camp in northern Kenya.[67]

By early December 2011, the UN's OCHA bureau announced that a scaling up of relief operations had resulted in an improvement in global and severe acute malnutrition rates as well as a decrease in mortality rates in southern Somalia's conflict zones relative to the start of the drought crisis in July/August. Although acute malnutrition rates remained much higher than median global acute malnutrition (GAM) and severe acute malnutrition (SAM) rates for the October–December season, global acute malnutrition rates had fallen from 30–58 percent to 20–34 percent and severe acute malnutrition rates in turn dropped from 9–29 percent in July to 6–11 percent. The mortality rate likewise declined from 1.1–6.1 per 10,000 people per day in July/August to 0.6–2.8 per 10,000 people per day.[4] Despite some gaps in aid delivery in certain areas due imposed Islamist bans, the Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit (FSNAU) also reported that its Nutrition Cluster had by December reached 357,107 of the estimated 450,000 children that had been acutely malnourished at the start of the crisis in July.[53]