La persecución de los cristianos se puede rastrear históricamente desde el primer siglo de la era cristiana hasta nuestros días . Tanto los misioneros cristianos como los conversos al cristianismo han sido objeto de persecución, a veces hasta el punto de ser martirizados por su fe , desde el surgimiento del cristianismo.

Los primeros cristianos fueron perseguidos a manos de los judíos , de cuya religión surgió el cristianismo , y de los romanos que controlaban muchos de los primeros centros del cristianismo en el Imperio romano . Desde el surgimiento de los estados cristianos en la Antigüedad tardía , los cristianos también han sido perseguidos por otros cristianos debido a diferencias en la doctrina que han sido declaradas heréticas . A principios del siglo IV , las persecuciones oficiales del imperio terminaron con el Edicto de Serdica en 311 y la práctica del cristianismo fue legalizada por el Edicto de Milán en 312. Para el año 380, los cristianos habían comenzado a perseguirse entre sí. Los cismas de la Antigüedad tardía y la Edad Media , incluidos los cismas de Roma-Constantinopla y las muchas controversias cristológicas , junto con la posterior Reforma protestante provocaron graves conflictos entre las denominaciones cristianas . Durante estos conflictos, los miembros de las diversas denominaciones se persiguieron con frecuencia entre sí y participaron en la violencia sectaria . En el siglo XX, las poblaciones cristianas fueron perseguidas, en ocasiones hasta el punto del genocidio , por diversos estados, entre ellos el Imperio Otomano y su estado sucesor , que cometieron las masacres hamidianas , el genocidio armenio , el genocidio asirio , el genocidio griego y el genocidio de Diyarbekir , y estados ateos como los del antiguo Bloque del Este .

La persecución de los cristianos ha continuado durante el siglo XXI . El cristianismo es la religión más grande del mundo y sus seguidores viven en todo el mundo. Aproximadamente el 10% de los cristianos del mundo son miembros de grupos minoritarios que viven en estados de mayoría no cristiana. [10] La persecución contemporánea de los cristianos incluye la persecución estatal oficial que ocurre principalmente en países ubicados en África y Asia porque tienen religiones estatales o porque sus gobiernos y sociedades practican el favoritismo religioso. Tal favoritismo suele ir acompañado de discriminación religiosa y persecución religiosa .

Según el informe de 2020 de la Comisión de los Estados Unidos para la Libertad Religiosa Internacional , los cristianos en Birmania , China , Eritrea , India , Irán , Nigeria , Corea del Norte , Pakistán , Rusia , Arabia Saudita , Siria y Vietnam son perseguidos; estos países están etiquetados como "países de especial preocupación" por el Departamento de Estado de los Estados Unidos , debido a la participación de sus gobiernos en, o la tolerancia de, "graves violaciones de la libertad religiosa". [11] : 2 El mismo informe recomienda que Afganistán , Argelia , Azerbaiyán , Bahréin , la República Centroafricana, Cuba , Egipto , Indonesia , Irak , Kazajstán , Malasia , Sudán y Turquía constituyan la "lista de vigilancia especial" del Departamento de Estado de los Estados Unidos de países en los que el gobierno permite o participa en "graves violaciones de la libertad religiosa ". [11] : 2

Gran parte de la persecución de los cristianos en los últimos tiempos es perpetrada por actores no estatales que son etiquetados como "entidades de particular preocupación" por el Departamento de Estado de los EE. UU., incluidos los grupos islamistas Boko Haram en Nigeria , el movimiento Houthi en Yemen , el Estado Islámico de Irak y el Levante - Provincia de Khorasan en Pakistán , al-Shabaab en Somalia , los talibanes en Afganistán , el Estado Islámico , así como el Ejército Unido del Estado Wa y los participantes en el conflicto de Kachin en Myanmar . [11] : 2

.jpg/440px-Crucifixion_of_Saint_Peter-Caravaggio_(c.1600).jpg)

El cristianismo primitivo comenzó como una secta entre los judíos del Segundo Templo . La disensión intercomunitaria comenzó casi inmediatamente. [12] Según el relato del Nuevo Testamento , Saulo de Tarso, antes de su conversión al cristianismo, persiguió a los primeros judeocristianos . Según los Hechos de los Apóstoles , un año después de la crucifixión romana de Jesús , Esteban fue apedreado por sus transgresiones a la ley judía . [13] Y Saulo (también conocido como Pablo ) consintió, mirando y presenciando la muerte de Esteban. [12] Más tarde, Pablo comienza una lista de sus propios sufrimientos después de la conversión en 2 Corintios 11: "Cinco veces recibí de los judíos los cuarenta azotes menos uno. Tres veces fui azotado con varas, una vez fui apedreado ..." [14]

En el año 41 d. C., Herodes Agripa , que ya poseía el territorio de Herodes Antipas y Filipo (sus antiguos colegas en la tetrarquía herodiana ), obtuvo el título de rey de los judíos y, en cierto sentido, reformó el reino de Judea de Herodes el Grande ( r. 37-4 a. C. ). Herodes Agripa estaba ansioso por ganarse el cariño de sus súbditos judíos y continuó la persecución en la que Santiago el Grande perdió la vida, San Pedro escapó por poco y el resto de los apóstoles huyeron. [12] Después de la muerte de Agripa en el año 44, comenzó la procuraduría romana (antes del 41 eran prefectos en la provincia de Judea) y esos líderes mantuvieron una paz neutral, hasta que el procurador Porcio Festo murió en el año 62 y el sumo sacerdote Ananus ben Ananus aprovechó el vacío de poder para atacar a la Iglesia y ejecutar a Santiago el Justo , entonces líder de los cristianos de Jerusalén .

El Nuevo Testamento afirma que Pablo fue encarcelado en varias ocasiones por las autoridades romanas, apedreado por los fariseos y dejado por muerto en una ocasión, y finalmente llevado a Roma como prisionero. Pedro y otros cristianos primitivos también fueron encarcelados, golpeados y acosados. La Primera Rebelión Judía , impulsada por la matanza romana de 3.000 judíos, condujo a la destrucción de Jerusalén en el año 70 d. C. , el fin del judaísmo del Segundo Templo (y el posterior ascenso lento del judaísmo rabínico ). [12]

Claudia Setzer afirma que "los judíos no vieron a los cristianos como claramente separados de su propia comunidad hasta al menos mediados del siglo II", pero la mayoría de los estudiosos sitúan la "separación de caminos" mucho antes, y la separación teológica se produjo inmediatamente. [15] El judaísmo del Segundo Templo había permitido más de una manera de ser judío. Después de la caída del Templo, una manera condujo al judaísmo rabínico, mientras que otra se convirtió en el cristianismo; pero el cristianismo fue "moldeado en torno a la convicción de que el judío, Jesús de Nazaret, no solo era el Mesías prometido a los judíos, sino el hijo de Dios, que ofrecía acceso a Dios y la bendición de Dios a los no judíos tanto como, y quizás eventualmente más que, a los judíos". [16] : 189 Si bien la escatología mesiánica tenía raíces profundas en el judaísmo, y la idea del siervo sufriente, conocido como el Mesías Efraín, había sido un aspecto desde la época de Isaías (siglo VII a. C.), en el primer siglo, esta idea fue vista como usurpada por los cristianos. Luego fue suprimido y no volvió a aparecer en la enseñanza rabínica hasta los escritos del siglo VII de Pesiqta Rabati. [17]

La visión tradicional de la separación del judaísmo y el cristianismo sostiene que los judíos cristianos huyeron en masa a Pella (poco antes de la caída del Templo en el año 70 d. C.) como resultado de la persecución y el odio judíos. [18] Steven D. Katz dice que "no puede haber duda de que la situación posterior al 70 fue testigo de un cambio en las relaciones entre judíos y cristianos". [19] El judaísmo intentó reconstituirse después del desastre, lo que incluyó determinar la respuesta adecuada al cristianismo judío. La forma exacta de esto no se conoce directamente, pero se alega tradicionalmente que tomó cuatro formas: la circulación de pronunciamientos oficiales anticristianos, la emisión de una prohibición oficial contra los cristianos que asistían a la sinagoga, una prohibición contra la lectura de escritos cristianos y la difusión de la maldición contra los herejes cristianos: el Birkat haMinim . [19]

El primer caso documentado de persecución de cristianos bajo supervisión imperial en el Imperio romano comienza con Nerón (54-68). En los Anales , Tácito afirma que Nerón culpó a los cristianos por el Gran Incendio de Roma , y aunque generalmente se cree que es auténtico y confiable, algunos eruditos modernos han puesto en duda esta opinión, en gran parte porque no hay más referencias a que Nerón culpara a los cristianos por el incendio hasta finales del siglo IV. [20] [21] Suetonio menciona los castigos infligidos a los cristianos, definidos como hombres que seguían una nueva y maléfica superstición, pero no especifica las razones del castigo; simplemente enumera el hecho junto con otros abusos denunciados por Nerón. [21] : 269 Hay un amplio consenso en que el Número de la bestia en el Libro del Apocalipsis , que suma 666, se deriva de una gematría del nombre de Nerón César, lo que indica que Nerón era visto como una figura excepcionalmente malvada. [22] Varias fuentes cristianas informan que el apóstol Pablo y San Pedro murieron durante la persecución neroniana. [23] [24] [25] [26]

En los dos primeros siglos, el cristianismo era una secta relativamente pequeña que no era una preocupación importante para el emperador. Rodney Stark estima que había menos de 10.000 cristianos en el año 100. El cristianismo creció hasta unos 200.000 en el año 200, lo que equivale a alrededor del 0,36% de la población del imperio, y luego a casi 2 millones en el año 250, lo que todavía representa menos del 2% de la población total del imperio. [27] Según Guy Laurie, la Iglesia no estaba en una lucha por su existencia durante sus primeros siglos. [28] Sin embargo, Bernard Green dice que, aunque las primeras persecuciones de los cristianos fueron generalmente esporádicas, locales y bajo la dirección de gobernadores regionales, no emperadores, los cristianos "siempre estuvieron sujetos a la opresión y en riesgo de persecución abierta". [29] La política de Trajano hacia los cristianos no era diferente del trato hacia otras sectas, es decir, sólo serían castigados si se negaban a adorar al emperador y a los dioses, pero no debían ser buscados. [30]

James L. Papandrea dice que hay diez emperadores generalmente aceptados por haber patrocinado la persecución estatal de los cristianos, [31] aunque la primera persecución patrocinada por el gobierno de todo el imperio no fue hasta Decio en 249. [32] Un relato temprano de una matanza en masa es la persecución en Lyon en la que los cristianos fueron supuestamente masacrados en masa al ser arrojados a las bestias salvajes bajo el decreto de los funcionarios romanos por supuestamente negarse a renunciar a su fe según Ireneo . [33] [34] En el siglo III, la casa del emperador Severo Alejandro contenía muchos cristianos, pero su sucesor, Maximino Tracio , odiando esta casa, ordenó que los líderes de las iglesias fueran ejecutados. [35] [36] Según Eusebio, esta persecución envió a Hipólito de Roma y al Papa Ponciano al exilio, pero otra evidencia sugiere que las persecuciones fueron locales en las provincias donde ocurrieron en lugar de suceder bajo la dirección del Emperador. [37]

Según dos tradiciones cristianas diferentes, Simón bar Kokhba , el líder de la segunda revuelta judía contra Roma (132-136 d. C.), que fue proclamado Mesías, persiguió a los cristianos: Justino Mártir afirma que los cristianos fueron castigados si no negaban y blasfemaban contra Jesucristo, mientras que Eusebio afirma que Bar Kokhba los acosó porque se negaron a unirse a su revuelta contra los romanos. [38]

Algunos cristianos primitivos buscaron y dieron la bienvenida al martirio. [39] [40] Según Droge y Tabor, "en 185, un grupo de cristianos se acercó al procónsul de Asia, Arrio Antonino, y le exigió ser ejecutado. El procónsul obligó a algunos de ellos y luego despidió al resto, diciendo que si querían suicidarse, había muchas cuerdas disponibles o acantilados desde los que podían saltar". [41] Este entusiasmo por la muerte se encuentra en las cartas de San Ignacio de Antioquía , quien fue arrestado y condenado como criminal antes de escribir sus cartas mientras se dirigía a la ejecución. Ignacio presenta su propio martirio como un sacrificio eucarístico voluntario que debe ser aceptado. [42] : 55

"Muchos actos martiriales presentan el martirio como una elección aguda que llega al núcleo de la identidad cristiana: vida o muerte, salvación o condenación, Cristo o apostasía..." [42] : 145 Posteriormente, la literatura sobre el martirio ha establecido distinciones entre aquellos que eran entusiastamente pro-martirio voluntario (los montanistas y donatistas ), aquellos que ocupaban una posición neutral y moderada (los ortodoxos), y aquellos que eran anti-martirio (los gnósticos ). [42] : 145

La categoría de mártir voluntario comenzó a surgir recién en el siglo III en el contexto de los esfuerzos por justificar la huida de la persecución. [43] La condena del martirio voluntario se utiliza para justificar la huida de Clemente de la persecución de los Severos en Alejandría en el año 202 d. C., y el martirio de Policarpo justifica la huida de Policarpo por las mismas razones. "El martirio voluntario se interpreta como una locura apasionada", mientras que "la huida de la persecución es paciencia" y el resultado es un verdadero martirio. [42] : 155

Daniel Boyarin rechaza el uso del término "martirio voluntario", diciendo que "si el martirio no es voluntario, no es martirio". [44] GEM de Ste. Croix añade una categoría de "martirio cuasi voluntario": "mártires que no fueron directamente responsables de su propio arresto pero que, después de ser arrestados, se comportaron con" una negativa obstinada a obedecer o acatar la autoridad. [42] : 153 Candida Moss afirma que el juicio de De Ste. Croix sobre qué valores vale la pena morir es moderno y no representa valores clásicos. Según ella, no existía el concepto de "martirio cuasi voluntario" en la antigüedad. [42] : 153

En el reinado del emperador Decio ( r. 249-251 ), se emitió un decreto que requería que todos los residentes del imperio realizaran sacrificios, que se haría cumplir mediante la emisión de cada persona con un libelo que certificara que habían realizado el ritual necesario. [45] No se sabe qué motivó el decreto de Decio, o si estaba destinado a atacar a los cristianos, aunque es posible que el emperador estuviera buscando favores divinos en las próximas guerras con los carpos y los godos . [45] Los cristianos que se negaron a ofrecer sacrificios públicamente o quemar incienso a los dioses romanos fueron acusados de impiedad y castigados con arresto, prisión, tortura o ejecución. [32] Según Eusebio, los obispos Alejandro de Jerusalén , Babilas de Antioquía y Fabián de Roma fueron encarcelados y asesinados. [45] El patriarca Dionisio de Alejandría escapó del cautiverio, mientras que el obispo Cipriano de Cartago huyó de su sede episcopal al campo. [45] La Iglesia cristiana, a pesar de que no hay ninguna indicación en los textos supervivientes de que el edicto se dirigiera a ningún grupo específico, nunca olvidó el reinado de Decio, a quien etiquetaron como ese "tirano feroz". [32] Después de la muerte de Decio, Treboniano Galo ( r. 251-253 ) lo sucedió y continuó la persecución deciana durante la duración de su reinado. [45]

La ascensión al trono de Valeriano ( 253-260 ), sucesor de Treboniano Galo , puso fin a la persecución de Decio. [45] Sin embargo, en 257 Valeriano comenzó a imponer la religión pública. Cipriano de Cartago fue exiliado y ejecutado al año siguiente, mientras que el papa Sixto II también fue condenado a muerte. [45] Dionisio de Alejandría fue juzgado, se le instó a reconocer a "los dioses naturales" con la esperanza de que su congregación lo imitara, y fue exiliado cuando se negó. [45]

Valeriano fue derrotado por los persas en la batalla de Edesa y él mismo fue tomado prisionero en 260. Según Eusebio, el hijo de Valeriano, co- augusto y sucesor Galieno ( r. 253-268 ) permitió a las comunidades cristianas volver a utilizar sus cementerios e hizo la restitución de sus edificios confiscados. [45] Eusebio escribió que Galieno permitió a los cristianos "libertad de acción". [45]

.jpg/440px-Barbara_of_Nicomedia_(Menologion_of_Basil_II).jpg)

La Gran Persecución, o Persecución Diocleciana, fue iniciada por el augusto mayor y emperador romano Diocleciano ( r. 284-305 ) el 23 de febrero de 303. [45] En el imperio romano oriental, la persecución oficial duró de manera intermitente hasta 313, mientras que en el imperio romano occidental la persecución no se aplicó a partir de 306. [45] Según el De mortibus persecutorum ("sobre las muertes de los perseguidores") de Lactancio , el emperador menor de Diocleciano, el césar Galerio ( r. 293-311 ) presionó al augusto para que comenzara a perseguir a los cristianos. [45] La Historia de la Iglesia de Eusebio de Cesarea informa que se promulgaron edictos imperiales para destruir iglesias y confiscar escrituras, y para remover a los ocupantes cristianos de puestos gubernamentales, mientras que los sacerdotes cristianos debían ser encarcelados y obligados a realizar sacrificios en la antigua religión romana . [45] En el relato de Eusebio, un hombre cristiano anónimo (nombrado por hagiógrafos posteriores como Euecio de Nicomedia y venerado el 27 de febrero) derribó un aviso público de un edicto imperial mientras los emperadores Diocleciano y Galerio estaban en Nicomedia ( İzmit ), una de las capitales de Diocleciano; según Lactancio, fue torturado y quemado vivo. [46] Según Lactancio, la iglesia de Nicomedia ( İzmit ) fue destruida, mientras que el Apéndice Optatan tiene un relato de la prefectura pretoriana de África que involucra la confiscación de materiales escritos que llevaron al cisma donatista . [45] Según los Mártires de Palestina de Eusebio y el De mortibus persecutorum de Lactancio , un cuarto edicto de 304 exigía que todos realizaran sacrificios, aunque en el imperio occidental esto no se aplicó. [45]

Un diálogo "inusualmente filosófico" se registra en los procedimientos del juicio de Phileas de Thmuis , obispo de Thmuis en el delta del Nilo en Egipto , que sobreviven en papiros griegos del siglo IV entre los papiros Bodmer y los papiros Chester Beatty de las bibliotecas Bodmer y Chester Beatty y en manuscritos en latín , etíope y copto de siglos posteriores, un cuerpo de hagiografía conocido como los Hechos de Phileas . [45] Phileas fue condenado en su quinto juicio en Alejandría bajo Clodio Culciano, el praefectus Aegypti el 4 de febrero de 305 (el décimo día de Mecheir ).

En el imperio occidental, la persecución de Diocleciano cesó con la usurpación de dos hijos de emperadores en 306: la de Constantino, que fue aclamado augusto por el ejército después de que su padre Constancio I ( r. 293-306 ) muriera, y la de Majencio ( r. 306-312 ), que fue elevado a augusto por el Senado romano después del retiro a regañadientes de su padre Maximiano ( r. 285-305 ) y su co- augusto Diocleciano en mayo de 305. [45] De Majencio, que controlaba Italia con su padre ahora no retirado, y Constantino, que controlaba Britania , Galia e Iberia , ninguno estaba inclinado a continuar la persecución. [45] Sin embargo, en el imperio oriental, Galerio, ahora augusto , continuó la política de Diocleciano. [45] Tanto la Historia de la Iglesia de Eusebio como los Mártires de Palestina dan relatos del martirio y la persecución de los cristianos, incluido el propio mentor de Eusebio, Pánfilo de Cesarea , con quien estuvo encarcelado durante la persecución. [45]

.jpg/440px-Peter_the_Archbishop_of_Alexandria_(Menologion_of_Basil_II).jpg)

_the_reader_(Menologion_of_Basil_II).jpg/440px-Martyrs_Silvanus_the_Bishop_of_Emesa,_Luke_the_deacon,_and_Mocius_(Mucius)_the_reader_(Menologion_of_Basil_II).jpg)

Cuando Galerio murió en mayo de 311, Lactancio y Eusebio informaron que había compuesto un edicto en su lecho de muerte -el Edicto de Serdica- que permitía la reunión de cristianos en conventículos y explicaba los motivos de la persecución anterior. [45] Eusebio escribió que la Pascua se celebraba abiertamente. [45] Sin embargo, en otoño, el sobrino de Galerio, ex césar y co- augusto Maximino Daia ( r. 310-313 ) estaba haciendo cumplir la persecución de Diocleciano en sus territorios de Anatolia y la Diócesis de Oriente en respuesta a peticiones de numerosas ciudades y provincias, incluidas Antioquía , Tiro , Licia y Pisidia . [45] Maximino también se vio alentado a actuar por un pronunciamiento oracular hecho por una estatua de Zeus Philios erigida en Antioquía por Teotecno de Antioquía, quien también organizó una petición anticristiana que se enviaría desde los antioquenos a Maximino, solicitando que los cristianos de allí fueran expulsados. [45] Entre los cristianos que se sabe que murieron en esta fase de la persecución están el presbítero Luciano de Antioquía , el obispo Metodio del Olimpo en Licia y Pedro , el patriarca de Alejandría . Derrotado en una guerra civil por el augusto Licinio ( r. 308-324 ), Maximino murió en 313, poniendo fin a la persecución sistemática del cristianismo en su conjunto en el Imperio romano. [45] Sólo se conoce por su nombre un mártir del reinado de Licinio, quien emitió el Edicto de Milán conjuntamente con su aliado, co- augusto y cuñado Constantino, que tuvo el efecto de reanudar la tolerancia de antes de la persecución y devolver la propiedad confiscada a los propietarios cristianos. [45]

La Nueva Enciclopedia Católica afirma que «los hagiógrafos antiguos, medievales y modernos tendían a exagerar el número de mártires. Puesto que el título de mártir es el más alto al que puede aspirar un cristiano, esta tendencia es natural». [47] Los intentos de estimar las cifras implicadas se basan inevitablemente en fuentes inadecuadas. [48]

La Iglesia cristiana marcó la conversión de Constantino el Grande como el cumplimiento final de su victoria celestial sobre los "falsos dioses". [49] : xxxii El estado romano siempre se había considerado a sí mismo como dirigido por Dios, ahora veía llegar a su fin la primera gran era de persecución, en la que se consideraba que el Diablo había usado la violencia abierta para disuadir el crecimiento del cristianismo. [50] Los cristianos católicos ortodoxos cercanos al estado romano representaban la persecución imperial como un fenómeno histórico, más que contemporáneo. [50] Según MacMullan, las historias cristianas están teñidas por este "triunfalismo". [51] : 4

Peter Leithart dice que, "[Constantino] no castigó a los paganos por ser paganos, ni a los judíos por ser judíos, y no adoptó una política de conversión forzada". [52] : 61 Los paganos permanecieron en posiciones importantes en su corte. [52] : 302 Prohibió los espectáculos de gladiadores, destruyó algunos templos y saqueó más, y utilizó una retórica contundente contra los no cristianos, pero nunca participó en una purga. [52] : 302 Los partidarios de Majencio no fueron masacrados cuando Constantino tomó la capital; la familia y la corte de Licinio no fueron asesinadas. [52] : 304 Sin embargo, los seguidores de doctrinas que eran vistas como heréticas o causantes de cisma fueron perseguidos durante el reinado de Constantino, el primer emperador romano cristiano, y serían perseguidos nuevamente más tarde en el siglo IV. [53] La consecuencia de las disputas doctrinales cristianas era generalmente la excomunión mutua, pero una vez que el gobierno romano se involucraba en la política eclesiástica, las facciones rivales podían encontrarse sujetas a "represión, expulsión, encarcelamiento o exilio" llevado a cabo por el ejército romano. [54] : 317

En el año 312, la secta cristiana llamada donatistas apeló a Constantino para resolver una disputa. Convocó un sínodo de obispos para escuchar el caso, pero el sínodo se puso de parte de ellos. Los donatistas se negaron a aceptar la decisión, por lo que se convocó una segunda reunión de 200 obispos en Arles, en el año 314, pero también fallaron en su contra. Los donatistas nuevamente se negaron a aceptar la decisión y procedieron a actuar en consecuencia estableciendo su propio obispo, construyendo sus propias iglesias y negándose a cooperar. [54] : 317 [53] : xv Esto fue un desafío a la autoridad imperial y produjo la misma respuesta que Roma había tomado en el pasado contra tales negativas. Para un emperador romano, "la religión podía ser tolerada solo mientras contribuyera a la estabilidad del estado". [55] : 87 Constantino utilizó el ejército en un esfuerzo por obligar a la obediencia donatista, quemando iglesias y martirizando a algunos entre 317 y 321. [53] : ix, xv Constantino fracasó en alcanzar su objetivo y finalmente admitió la derrota. El cisma permaneció y el donatismo continuó. [54] : 318 Después de Constantino, su hijo menor Flavio Julio Constante inició la campaña macariana contra los donatistas entre 346 y 348 que solo logró renovar la lucha sectaria y crear más mártires. El donatismo continuó. [53] : xvii

El siglo IV estuvo dominado por sus numerosos conflictos que definían la ortodoxia frente a la heterodoxia y la herejía. En el imperio romano oriental, conocido como Bizancio, la controversia arriana comenzó con su debate sobre las fórmulas trinitarias que duró 56 años. [56] : 141 A medida que se trasladó a Occidente, el centro de la controversia fue el "campeón de la ortodoxia", Atanasio . En 355 Constancio, que apoyaba el arrianismo, ordenó la supresión y el exilio de Atanasio, expulsó al papa ortodoxo Liberio de Roma y exilió a los obispos que se negaron a consentir al exilio de Atanasio. [57] En 355, Dionisio , obispo de Mediolanum ( Milán ), fue expulsado de su sede episcopal y reemplazado por el cristiano arriano Auxentius de Milán . [58] Cuando Constancio regresó a Roma en 357, consintió en permitir el regreso de Liberio al papado; El papa arriano Félix II , que lo había reemplazado, fue expulsado junto con sus seguidores. [57]

El último emperador de la dinastía constantiniana , el hijo del medio hermano de Constantino, Juliano ( r. 361-363 ), se opuso al cristianismo y trató de restaurar la religión tradicional, aunque no organizó una persecución general u oficial. [45]

Según la Collectio Avellana , tras la muerte del papa Liberio en 366, Dámaso, asistido por bandas contratadas de "aurigas" y hombres "de la arena", irrumpió en la Basílica Julia para impedir violentamente la elección del papa Ursicino . [57] La batalla duró tres días, "con gran matanza de fieles" y una semana después Dámaso tomó la Basílica de Letrán , se ordenó como papa Dámaso I y obligó al praefectus urbi Viventius y al praefectus annonae a exiliar a Ursicino. [ 57] Dámaso hizo arrestar a siete sacerdotes cristianos y los puso a la espera del destierro, pero escaparon y los "sepultureros" y el clero menor se unieron a otra turba de hombres del hipódromo y del anfiteatro reunidos por el papa para atacar la Basílica de Liberia , donde los leales a Ursacino se habían refugiado. [57] Según Amiano Marcelino , el 26 de octubre, la turba del Papa mató a 137 personas en la iglesia en un solo día, y muchas más murieron posteriormente. [57] El público romano con frecuencia exigía al emperador Valentiniano el Grande que derrocara a Dámaso del trono de San Pedro, llamándolo asesino por haber librado una "guerra sucia" contra los cristianos. [57]

En el siglo IV, el rey tervingo Atanarico ordenó en torno al año 375 la persecución gótica de los cristianos . [59] Atanarico le perturbaba la difusión del cristianismo gótico entre sus seguidores y temía que el paganismo gótico fuera desplazado .

No fue hasta finales del siglo IV, durante los reinados de los augustos Graciano ( r. 367-383 ), Valentiniano II ( r. 375-392 ) y Teodosio I ( r. 379-395 ), que el cristianismo se convertiría en la religión oficial del imperio con la promulgación conjunta del Edicto de Tesalónica , que establecía el cristianismo niceno como religión estatal y como iglesia estatal del Imperio romano el 27 de febrero de 380. Después de esto comenzó la persecución estatal de los cristianos no nicenos, incluidos los devotos arrianos y no trinitarios . [60] : 267

Cuando Agustín se convirtió en obispo coadjutor de Hipona en 395, tanto el partido donatista como el católico habían existido, durante décadas, uno al lado del otro, con una doble línea de obispos para las mismas ciudades, todos compitiendo por la lealtad del pueblo. [53] : xv [a] : 334 Agustín estaba angustiado por el cisma en curso, pero sostenía la opinión de que la creencia no puede ser obligada, por lo que apeló a los donatistas utilizando propaganda popular, debate, apelación personal, Concilios Generales, apelaciones al emperador y presión política, pero todos los intentos fracasaron. [62] : 242, 254 Los donatistas fomentaron protestas y violencia callejera, abordaron a los viajeros, atacaron a católicos al azar sin previo aviso, a menudo causando daños corporales graves y no provocados, como golpear a las personas con palos, cortarles las manos y los pies y sacarles los ojos, al mismo tiempo que invitaban a su propio martirio. [63] : 120–121 En 408, Agustín apoyó el uso de la fuerza por parte del estado contra ellos. [61] : 107–116 El historiador Frederick Russell dice que Agustín no creía que esto "haría a los donatistas más virtuosos", pero sí creía que los haría "menos viciosos". [64] : 128

Agustín escribió que, en el pasado, hubo diez persecuciones cristianas, comenzando con la persecución de Nerón, y alegando persecuciones por parte de los emperadores Domiciano , Trajano , "Antonino" ( Marco Aurelio ), "Severo" ( Septimio Severo ) y Maximino ( Tracia ), así como persecuciones de Decio y Valeriano, y luego otra por Aureliano , así como por Diocleciano y Maximiano. [50] Estas diez persecuciones Agustín comparó con las 10 plagas de Egipto en el Libro del Éxodo . [nota 1] [65] Agustín no vio estas primeras persecuciones de la misma manera que la de los herejes del siglo IV. En la opinión de Agustín, cuando el propósito de la persecución es "corregir e instruir amorosamente", entonces se convierte en disciplina y es justa. [66] : 2 Agustín escribió que "la coerción no puede transmitir la verdad al hereje, pero puede prepararlos para escuchar y recibir la verdad". [61] : 107–116 Dijo que la iglesia disciplinaría a su gente por un amoroso deseo de sanarlo, y que, "una vez obligados a entrar, los herejes gradualmente darían su asentimiento voluntario a la verdad de la ortodoxia cristiana". [64] : 115 Se opuso a la severidad de Roma y a la ejecución de los herejes. [67] : 768

Es su enseñanza sobre la coerción lo que hace que la literatura sobre Agustín se refiera frecuentemente a él como le prince et patriarche de persecuteurs (el príncipe y patriarca de los perseguidores). [63] : 116 [61] : 107 Russell dice que la teoría de la coerción de Agustín "no fue elaborada a partir de un dogma, sino en respuesta a una situación histórica única" y, por lo tanto, depende del contexto, mientras que otros la ven como inconsistente con sus otras enseñanzas. [64] : 125 Su autoridad sobre la cuestión de la coerción fue indiscutible durante más de un milenio en el cristianismo occidental y, según Brown, "proporcionó la base teológica para la justificación de la persecución medieval". [61] : 107–116

Calínico I , inicialmente sacerdote y esceúfilax en la Iglesia de la Theotokos de Blanquernas, se convirtió en patriarca de Constantinopla en 693 o 694. [68] : 58–59 Habiendo rehusado consentir la demolición de una capilla en el Gran Palacio , la Theotokos ton Metropolitou , y posiblemente habiendo estado involucrado en la deposición y exilio de Justiniano II ( r. 685–695, 705–711 ), una acusación negada por el Sinaxario de Constantinopla , él mismo fue exiliado a Roma cuando Justiniano regresó al poder en 705. [68] : 58–59 El emperador hizo emparedar a Calínico . [68] : 58–59 Se dice que sobrevivió cuarenta días cuando se abrió el muro para revisar su condición, aunque murió cuatro días después. [68] : 58–59

Las violentas persecuciones de los cristianos comenzaron en serio en el largo reinado de Sapor II ( r. 309-379 ). [69] Se registra una persecución de cristianos en Kirkuk en la primera década de Sapor, aunque la mayor parte de la persecución ocurrió después de 341. [69] En guerra con el emperador romano Constancio II ( r. 337-361 ), Sapor impuso un impuesto para cubrir los gastos de guerra, y Shemon Bar Sabbae , el obispo de Seleucia-Ctesifonte , se negó a cobrarlo. [69] A menudo citando la colaboración con los romanos, los persas comenzaron a perseguir y ejecutar a los cristianos. [69] Las narraciones de Passio describen el destino de algunos cristianos venerados como mártires; son de variada confiabilidad histórica, algunos son registros contemporáneos de testigos oculares, otros dependían de la tradición popular a cierta distancia de los eventos. [69] Un apéndice del Martirologio siríaco de 411 enumera a los mártires cristianos de Persia , pero otros relatos de juicios de mártires contienen importantes detalles históricos sobre el funcionamiento de la geografía histórica del Imperio sasánida y las prácticas judiciales y administrativas. [69] Algunos fueron traducidos al sogdiano y descubiertos en Turfán . [69]

Bajo Yazdegerd I ( r. 399-420 ) hubo persecuciones ocasionales, incluyendo un caso de persecución en represalia por la quema de un templo de fuego zoroastriano por parte de un sacerdote cristiano, y ocurrieron más persecuciones en el reinado de Bahram V ( r. 420-438 ). [69] Bajo Yazdegerd II ( r. 438-457 ) un caso de persecución en 446 está registrado en el martirologio siríaco Actas de Ādur-hormizd y de Anāhīd . [69] Algunos martirios individuales están registrados del reinado de Khosrow I ( r. 531-579 ), pero probablemente no hubo persecuciones masivas. [69] Aunque según un tratado de paz de 562 entre Cosroes y su homólogo romano Justiniano I ( r. 527-565 ), a los cristianos de Persia se les concedió la libertad de religión; sin embargo, el proselitismo era un crimen capital. [69] En ese momento, la Iglesia de Oriente y su cabeza, la Catholicosis de Oriente , estaban integradas en la administración del imperio y la persecución masiva era rara. [69]

La política sasánida pasó de la tolerancia hacia otras religiones bajo Sapor I a la intolerancia bajo Bahram I y aparentemente a un retorno a la política de Sapor hasta el reinado de Sapor II . La persecución en ese momento fue iniciada por la conversión de Constantino al cristianismo que siguió a la del rey armenio Tiridates alrededor del año 301. Por lo tanto, los cristianos eran vistos con sospechas de ser partidarios secretos del Imperio romano. Esto no cambió hasta el siglo V, cuando la Iglesia de Oriente se separó de la Iglesia de Occidente . [70] Las élites zoroastrianas continuaron viendo a los cristianos con enemistad y desconfianza durante todo el siglo V, y la amenaza de persecución siguió siendo significativa, especialmente durante la guerra contra los romanos. [71]

El sumo sacerdote zoroástrico Kartir , en su inscripción fechada alrededor del año 280 en el monumento Ka'ba-ye Zartosht en la necrópolis de Naqsh-e Rostam cerca de Zangiabad, Fars , se refiere a la persecución ( zatan – "golpear, matar") de los cristianos ("nazareos n'zl'y y cristianos klstyd'n "). Kartir tomó al cristianismo como un serio oponente. El uso de la doble expresión puede ser indicativo de los cristianos de habla griega deportados por Shapur I de Antioquía y otras ciudades durante su guerra contra los romanos. [72] Los esfuerzos de Constantino por proteger a los cristianos persas los convirtieron en blanco de acusaciones de deslealtad a los sasánidas. Con la reanudación del conflicto romano-sasánida bajo Constancio II , la posición cristiana se volvió insostenible. Los sacerdotes zoroástricos apuntaron al clero y a los ascetas de los cristianos locales para eliminar a los líderes de la iglesia. Un manuscrito siríaco encontrado en Edesa en el año 411 documenta docenas de ejecuciones en diversas partes del Imperio sasánida occidental. [71]

En el año 341, Sapor II ordenó la persecución de todos los cristianos. [73] [74] En respuesta a su actitud subversiva y su apoyo a los romanos, Sapor II duplicó los impuestos a los cristianos. Shemon Bar Sabbae le informó que no podía pagar los impuestos que se le exigían a él y a su comunidad. Fue martirizado y comenzó un período de cuarenta años de persecución de los cristianos. El Concilio de Seleucia-Ctesifonte renunció a elegir obispos porque eso resultaría en la muerte. Los mobads locales –clérigos zoroastrianos– con la ayuda de los sátrapas organizaron matanzas de cristianos en Adiabene , Beth Garmae , Khuzistan y muchas otras provincias. [75]

Yazdegerd I mostró tolerancia hacia los judíos y los cristianos durante gran parte de su gobierno. Permitió a los cristianos practicar su religión libremente, demolió monasterios y reconstruyeron iglesias y se permitió a los misioneros operar libremente. Sin embargo, revirtió sus políticas durante la última parte de su reinado, suprimiendo las actividades misioneras. [76] Bahram V continuó e intensificó su persecución, lo que resultó en que muchos de ellos huyeran al imperio romano oriental . Bahram exigió su regreso, comenzando la guerra romano-sasánida de 421-422 . La guerra terminó con un acuerdo de libertad de religión para los cristianos en Irán con el del mazdeísmo en Roma. Mientras tanto, los cristianos sufrieron la destrucción de iglesias, renunciaron a la fe, vieron su propiedad privada confiscada y muchos fueron expulsados. [77]

Yazdegerd II había ordenado a todos sus súbditos que abrazaran el mazdeísmo en un intento de unificar ideológicamente su imperio. El Cáucaso se rebeló para defender el cristianismo que se había integrado en su cultura local, y los aristócratas armenios recurrieron a los romanos en busca de ayuda. Sin embargo, los rebeldes fueron derrotados en una batalla en la llanura de Avarayr . Yeghishe, en su Historia de Vardan y la guerra armenia , rinde homenaje a las batallas libradas para defender el cristianismo. [78] Se libró otra revuelta entre 481 y 483 que fue reprimida. Sin embargo, los armenios lograron obtener la libertad de religión, entre otras mejoras. [79]

Los relatos de ejecuciones por apostasía de zoroastrianos que se convirtieron al cristianismo durante el gobierno sasánida proliferaron desde el siglo V hasta principios del VII, y continuaron produciéndose incluso después del colapso de los sasánidas. El castigo de los apóstatas aumentó bajo Yazdegerd I y continuó bajo los reyes sucesivos. Era normativo que los apóstatas que eran llevados ante la atención de las autoridades fueran ejecutados, aunque el procesamiento de la apostasía dependía de las circunstancias políticas y la jurisprudencia zoroástrica. Según Richard E. Payne, las ejecuciones tenían como objetivo crear un límite mutuamente reconocido entre las interacciones de las personas de las dos religiones y evitar que una religión desafiara la viabilidad de otra. Aunque la violencia contra los cristianos era selectiva y se llevaba a cabo especialmente contra las élites, sirvió para mantener a las comunidades cristianas en una posición subordinada y, sin embargo, viable en relación con el zoroastrismo. A los cristianos se les permitió construir edificios religiosos y servir en el gobierno siempre que no expandieran sus instituciones y población a expensas del zoroastrismo. [80]

En general, se consideraba que Cosroes I era tolerante con los cristianos y se interesaba por las disputas filosóficas y teológicas durante su reinado. Sebeos afirmó que se había convertido al cristianismo en su lecho de muerte. Juan de Éfeso describe una revuelta armenia en la que afirma que Cosroes había intentado imponer el zoroastrismo en Armenia. El relato, sin embargo, es muy similar al de la revuelta armenia de 451. Además, Sebeos no menciona ninguna persecución religiosa en su relato de la revuelta de 571. [81] El historiador al-Tabari conserva una historia sobre la tolerancia de Hormizd IV . Cuando se le preguntó por qué toleraba a los cristianos, respondió: "Así como nuestro trono real no puede sostenerse sobre sus patas delanteras sin sus dos patas traseras, nuestro reino no puede mantenerse en pie o resistir con firmeza si hacemos que los cristianos y los seguidores de otras religiones, que difieren en creencia de las nuestras, se vuelvan hostiles hacia nosotros". [82]

Varios meses después de la conquista persa en el año 614 d. C., se produjo un motín en Jerusalén, y el gobernador judío de Jerusalén, Nehemías, fue asesinado por una banda de jóvenes cristianos junto con su "consejo de los justos" mientras estaba haciendo planes para la construcción del Tercer Templo . En ese momento, los cristianos se habían aliado con el Imperio Romano de Oriente . Poco después, los acontecimientos se intensificaron hasta convertirse en una rebelión cristiana a gran escala, lo que dio lugar a una batalla contra los judíos y los cristianos que vivían en Jerusalén. Después de la batalla, muchos judíos fueron asesinados y los sobrevivientes huyeron a Cesarea, que todavía estaba en manos del ejército persa.

La reacción judeo-persa fue despiadada: el general persa sasánida Xorheam reunió tropas judeo-persas y fue a acampar alrededor de Jerusalén y la sitió durante 19 días. [83] Finalmente, cavando debajo de los cimientos de Jerusalén, destruyeron el muro y el día 19 del asedio, las fuerzas judeo-persas tomaron Jerusalén. [83]

Según el relato del eclesiástico e historiador armenio Sebeos , el asedio resultó en un total de 17.000 muertos cristianos, la cifra más antigua y, por lo tanto, la más comúnmente aceptada. [84] : 207 Según Strategius , 4.518 prisioneros fueron masacrados solo cerca del embalse de Mamilla . [85] Una cueva que contiene cientos de esqueletos cerca de la Puerta de Jaffa , a 200 metros al este de la gran piscina de la era romana en Mamilla, se correlaciona con la masacre de cristianos a manos de los persas mencionada en los escritos de Strategius. Si bien refuerza la evidencia de la masacre de cristianos, la evidencia arqueológica parece menos concluyente sobre la destrucción de iglesias y monasterios cristianos en Jerusalén. [85] [86] [ verificación fallida ]

Según el relato posterior de Strategius, cuya perspectiva parece ser la de un griego bizantino y muestra una antipatía hacia los judíos, [87] miles de cristianos fueron masacrados durante la conquista de la ciudad. Las estimaciones basadas en diversas copias de los manuscritos de Strategos varían entre 4.518 y 66.509 muertos. [85] Strategos escribió que los judíos se ofrecieron a ayudarlos a escapar de la muerte si "se convertían en judíos y negaban a Cristo", y los cautivos cristianos se negaron. Enfadados, los judíos supuestamente compraron cristianos para matarlos. [88] En 1989, el arqueólogo israelí Ronny Reich descubrió una fosa común en la cueva de Mamilla , cerca del lugar donde Strategius registró la masacre. Los restos humanos estaban en malas condiciones y contenían un mínimo de 526 individuos. [89]

De las numerosas excavaciones realizadas en Galilea , se desprende claramente que todas las iglesias habían sido destruidas durante el período comprendido entre la invasión persa y la conquista árabe en 637. La iglesia de Shave Ziyyon fue destruida e incendiada en 614. Un destino similar corrió la iglesia de Evron , Nahariya , 'Arabe y el monasterio de Shelomi . El monasterio de Kursi resultó dañado durante la invasión. [90]

En el año 516 d. C., estallaron disturbios tribales en Yemen y varias élites tribales lucharon por el poder. Una de esas élites fue Joseph Dhu Nuwas o "Yousef Asa'ar", un rey judío del reino himyarita que se menciona en antiguas inscripciones del sur de Arabia. Fuentes siríacas y griegas bizantinas afirman que luchó en su guerra porque los cristianos de Yemen se negaron a renunciar al cristianismo. En 2009, un documental emitido en la BBC defendió la afirmación de que a los aldeanos se les había ofrecido la opción de convertirse al judaísmo o la muerte y que luego fueron masacrados 20.000 cristianos, afirmando que "el equipo de producción habló con muchos historiadores durante un período de 18 meses, entre ellos Nigel Groom , que fue nuestro consultor, y el profesor Abdul Rahman Al-Ansary , ex profesor de arqueología en la Universidad Rey Saud en Riad". [91] Las inscripciones documentadas por el propio Yousef muestran el gran orgullo que expresó después de matar a más de 22.000 cristianos en Zafar y Najran . [92] El historiador Glen Bowersock describió esta masacre como un "salvaje pogromo que el rey judío de los árabes lanzó contra los cristianos en la ciudad de Najran. El propio rey informó con todo lujo de detalles a sus aliados árabes y persas sobre las masacres que había infligido a todos los cristianos que se negaron a convertirse al judaísmo". [93]

Como se los considera " Pueblo del Libro " en la religión islámica , los cristianos bajo el gobierno musulmán estaban sujetos al estatus de dhimmi (junto con los judíos, samaritanos , gnósticos , mandeos y zoroastrianos ), que era inferior al estatus de los musulmanes. [94] [95] Los cristianos y otras minorías religiosas se enfrentaron así a la discriminación y persecución religiosa , ya que se les prohibió hacer proselitismo (para los cristianos, estaba prohibido evangelizar o difundir el cristianismo ) en las tierras invadidas por los musulmanes árabes bajo pena de muerte, se les prohibió portar armas, ejercer ciertas profesiones y se les obligó a vestirse de manera diferente para distinguirse de los árabes. [94] Bajo la ley islámica ( sharīʿa ), los no musulmanes estaban obligados a pagar los impuestos jizya y kharaj , [94] [95] junto con fuertes rescates periódicos impuestos a las comunidades cristianas por los gobernantes musulmanes para financiar campañas militares, todo lo cual contribuía con una proporción significativa de ingresos a los estados islámicos mientras que, a la inversa, reducía a muchos cristianos a la pobreza, y estas dificultades financieras y sociales obligaron a muchos cristianos a convertirse al Islam . [94] Los cristianos que no podían pagar estos impuestos se vieron obligados a entregar a sus hijos a los gobernantes musulmanes como pago, quienes los venderían como esclavos a hogares musulmanes donde se vieron obligados a convertirse al Islam . [94]

Según la tradición de la Iglesia Ortodoxa Siria , la conquista musulmana del Levante fue un alivio para los cristianos oprimidos por el Imperio Romano de Occidente. [95] Miguel el Sirio , patriarca de Antioquía , escribió más tarde que el Dios cristiano había "levantado del sur a los hijos de Ismael para librarnos por ellos de las manos de los romanos". [95] Varias comunidades cristianas en las regiones de Palestina , Siria , Líbano y Armenia resentían el gobierno del Imperio Romano de Occidente o el del Imperio bizantino, y por lo tanto prefirieron vivir en condiciones económicas y políticas más favorables como dhimmi bajo los gobernantes musulmanes. [95] Sin embargo, los historiadores modernos también reconocen que las poblaciones cristianas que vivían en las tierras invadidas por los ejércitos musulmanes árabes entre los siglos VII y X d. C. sufrieron persecución religiosa , violencia religiosa y martirio varias veces a manos de funcionarios y gobernantes musulmanes árabes; [95] [96] [97] [98] Muchos fueron ejecutados bajo la pena de muerte islámica por defender su fe cristiana a través de actos dramáticos de resistencia como negarse a convertirse al Islam, repudio a la religión islámica y posterior reconversión al cristianismo , y blasfemia hacia las creencias musulmanas . [96] [97] [98]

Cuando Amr ibn al-As conquistó Trípoli en 643, obligó a los bereberes judíos y cristianos a entregar a sus esposas e hijos como esclavos al ejército árabe como parte de su yizya . [99] [100] [101]

Alrededor del año 666 d.C., Uqba ibn Nafi “conquistó las ciudades del sur de Túnez... masacrando a todos los cristianos que vivían allí”. [102] Fuentes musulmanas informan de que libró innumerables incursiones, que a menudo terminaban con el saqueo total y la esclavización masiva de las ciudades. [103]

La evidencia arqueológica del norte de África en la región de Cirenaica apunta a la destrucción de iglesias a lo largo de la ruta que siguieron los conquistadores islámicos a fines del siglo VII, y los notables tesoros artísticos enterrados a lo largo de las rutas que conducían al norte de España por los visigodos e hispanorromanos que huían durante principios del siglo VIII consisten en gran parte en parafernalia religiosa y dinástica que los habitantes cristianos obviamente querían proteger del saqueo y la profanación musulmanes. [104]

Según la escuela Ḥanafī de la ley islámica ( sharīʿa ), el testimonio de un no musulmán (como un cristiano o un judío) no se consideraba válido contra el testimonio de un musulmán en asuntos legales o civiles. Históricamente, en la cultura islámica y la ley islámica tradicional, a las mujeres musulmanas se les ha prohibido casarse con hombres cristianos o judíos , mientras que a los hombres musulmanes se les ha permitido casarse con mujeres cristianas o judías [105] [106] ( véase : Matrimonio interreligioso en el Islam ). Los cristianos bajo el gobierno islámico tenían derecho a convertirse al Islam o a cualquier otra religión, mientras que, por el contrario, un murtad , o un apóstata del Islam , se enfrentaba a severas penas o incluso hadd , que podían incluir la pena de muerte islámica . [96] [97] [98]

En general, a los cristianos sometidos al gobierno islámico se les permitía practicar su religión con algunas limitaciones notables derivadas del Pacto apócrifo de Umar . Este tratado, supuestamente promulgado en el año 717 d. C., prohibía a los cristianos exhibir públicamente la cruz en los edificios de las iglesias, convocar a los feligreses a la oración con una campana, reconstruir o reparar iglesias y monasterios después de que hubieran sido destruidos o dañados, e impuso otras restricciones relacionadas con ocupaciones, vestimenta y armas. [107] El califato omeya persiguió a muchos cristianos bereberes en los siglos VII y VIII d. C., quienes lentamente se convirtieron al Islam. [108]

En el Al-Ándalus omeya (la península Ibérica ), la escuela Mālikī de la ley islámica era la más predominante. [97] Los martirios de cuarenta y ocho mártires cristianos que tuvieron lugar en el Emirato de Córdoba entre 850 y 859 d. C. [109] están registrados en el tratado hagiográfico escrito por el erudito cristiano ibérico y latinista Eulogio de Córdoba . [96] [97] [98] Los mártires de Córdoba fueron ejecutados bajo el gobierno de Abd al-Rahman II y Muhammad I , y la hagiografía de Eulogio describe en detalle las ejecuciones de los mártires por violaciones capitales de la ley islámica, incluida la apostasía y la blasfemia . [96] [97] [98]

Después de las conquistas árabes, varias tribus árabes cristianas sufrieron esclavitud y conversión forzada. [110]

A principios del siglo VIII, bajo el gobierno de los Omeyas, 63 de un grupo de 70 peregrinos cristianos de Iconio fueron capturados, torturados y ejecutados por orden del gobernador árabe de Cesarea por negarse a convertirse al Islam (siete fueron convertidos al Islam a la fuerza bajo tortura). Poco después, otros sesenta peregrinos cristianos de Amorium fueron crucificados en Jerusalén. [111]

Los almohades causaron una enorme destrucción a la población cristiana de Iberia. Decenas de miles de cristianos nativos de Iberia (Hispania) fueron deportados de sus tierras ancestrales a África por los almorávides y almohades. Sospechaban que los cristianos podían hacerse pasar por una quinta columna que podría ayudar potencialmente a sus correligionarios en el norte de Iberia. Muchos cristianos murieron en el camino hacia el norte de África durante estas expulsiones. [112] [113] Los cristianos bajo los almorávides sufrieron persecuciones y expulsiones masivas a África. En 1099 los almorávides saquearon la gran iglesia de la ciudad de Granada. En 1101 los cristianos huyeron de la ciudad de Valencia a los reinos católicos. En 1106 los almorávides deportaron a los cristianos de Málaga a África. En 1126, después de una rebelión cristiana fallida en Granada, los almorávides expulsaron a toda la población cristiana de la ciudad a África. Y en 1138, Ibn Tashufin se llevó por la fuerza a muchos miles de cristianos con él a África. [114]

Los mozárabes oprimidos enviaron emisarios al rey de Aragón, Alfonso I el Batalleur (1104-1134), para pedirle que acudiera en su ayuda y los liberara de los almorávides. Tras la incursión que el rey de Aragón lanzó en Andalucía en 1125-26 en respuesta a las súplicas de los mozárabes de Granada, estos fueron deportados en masa a Marruecos en el otoño de 1126. [115] Otra oleada de expulsiones a África tuvo lugar once años después y, como resultado, quedaron muy pocos cristianos en Andalucía. Lo que quedaba de la población católica cristiana en Granada fue exterminada tras una revuelta contra los almohades en 1164. El califa Abu Yaqub Yusuf se jactó de no haber dejado ninguna iglesia o sinagoga en pie en al-Andalus. [113]

Los clérigos musulmanes de Al Andalus consideraban a los cristianos y judíos como personas sucias e impuras y temían que un contacto excesivo con ellos pudiera contaminar a los musulmanes. En Sevilla, el faqih Ibn Abdun emitió estas normas que segregaban a las personas de ambas religiones: [116]

Un musulmán no debe dar masajes a un judío o a un cristiano, ni tirar sus desechos ni limpiar sus letrinas. El judío y el cristiano son más aptos para tales oficios, ya que son los oficios de los viles. Un musulmán no debe cuidar el animal de un judío o de un cristiano, ni servirle de arriero [ni los católicos ni los judíos podían montar a caballo; sólo los musulmanes podían hacerlo], ni sujetar su estribo. Si se sabe que algún musulmán hace esto, debe ser denunciado. […] A ningún judío o cristiano [inconverso] se le debe permitir vestirse con el traje de gente de posición, de jurista o de hombre digno [esta disposición hace eco del Pacto de Umar]. Por el contrario, deben ser aborrecidos y evitados y no deben ser recibidos con la fórmula: “La paz sea con vosotros”, porque el demonio ha ganado dominio sobre ellos y les ha hecho olvidar el nombre de Dios. Son el partido del diablo, “y en verdad, el partido del diablo son los perdedores” (Corán 57:22). Deben tener un signo distintivo por el cual se los reconozca para su vergüenza [énfasis añadido].

Se supone que Jorge Limnaiotes, un monje del Monte Olimpo conocido solo por el Sinaxario de Constantinopla y otros sinaxarios , tenía 95 años cuando fue torturado por su iconodulismo . [68] : 43 En el reinado de León III el Isaurio ( r. 717–741 ), fue mutilado por rinotomía y le quemaron la cabeza. [68] : 43

Germano I de Constantinopla , hijo del patricio Justiniano, cortesano del emperador Heraclio ( r. 610–641 ), habiendo sido castrado e inscrito en el clero de la catedral de Santa Sofía cuando su padre fue ejecutado en 669, fue más tarde obispo de Cícico y luego patriarca de Constantinopla desde 715. [68] : 45–46 En 730, durante el reinado de León III ( r. 717–741 ), Germano fue depuesto y desterrado, muriendo en el exilio en Plantanion ( Akçaabat ). [68] : 45–46 León III también exilió al monje Juan el Psichaites, un iconódulo, a Cherson , donde permaneció hasta después de la muerte del emperador. [68] : 57

Según el Synaxarion de Constantinopla , los clérigos Hipatio y Andrés del thema tracesio fueron, durante la persecución de León III, llevados a la capital, encarcelados y torturados. [68] : 49 El Synaxarion afirma que les aplicaron las brasas de iconos quemados en la cabeza, los sometieron a otros tormentos y luego los arrastraron por las calles bizantinas hasta su ejecución pública en el área de la VII Colina de la ciudad , la llamada en griego medieval : ξηρόλοφος , romanizado : Χērólophos , lit. 'colina seca' cerca del Foro de Arcadio . [68] : 49

Andrés de Creta fue golpeado y encarcelado en Constantinopla después de haber debatido con el emperador iconoclasta Constantino V ( r. 741–775 ), posiblemente en 767 o 768, y luego maltratado por los bizantinos mientras era arrastrado por la ciudad, muriendo de pérdida de sangre cuando un pescador le cortó el pie en el Foro del Buey . [68] : 19 La iglesia de San Andrés en Krisei recibió su nombre en su honor, aunque los eruditos dudan de su existencia. [68] : 19

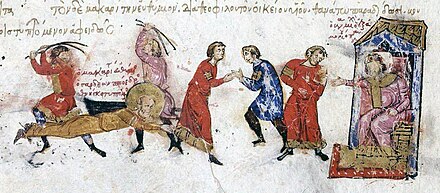

Después de haber derrotado y asesinado al emperador Nicéforo I ( r. 802-811 ) en la batalla de Pliska en 811, el kan del Primer Imperio Búlgaro , Krum , también ejecutó a varios soldados romanos que se negaron a renunciar al cristianismo, aunque estos martirios, conocidos solo por el Sinaxario de Constantinopla , pueden ser completamente legendarios. [68] : 66–67 En 813, los búlgaros invadieron el thema de Tracia , liderados por Krum, y la ciudad de Adrianópolis ( Edirne ) fue capturada. [68] : 66 El sucesor de Krum, Dukum, murió poco después que el propio Krum, siendo sucedido por Ditzevg, quien mató a Manuel, el arzobispo de Adrianópolis, en enero de 815. [68] : 66 Según el Sinaxario de Constantinopla y el Menologio de Basilio II , el propio sucesor de Ditzevg, Omurtag, mató a unos 380 cristianos más tarde ese mes. [68] : 66 Las víctimas incluyeron al arzobispo de Develtos , Jorge, y al obispo de Nicea tracia, León, así como dos estrategos llamados Juan y León. Colectivamente, estos son conocidos como los Mártires de Adrianópolis . [68] : 66

El monje bizantino Makarios, del monasterio de Pelekete en Bitinia, habiendo rechazado ya una posición envidiable en la corte ofrecida por el emperador iconoclasta León IV el Jázaro ( r. 775-780 ) a cambio del repudio de su iconodulismo, fue expulsado del monasterio por León V el Armenio ( r. 813-820 ), quien también lo encarceló y lo exilió. [68] : 65

El patriarca Nicéforo I de Constantinopla disintió del iconoclasta Concilio de Constantinopla de 815 y, como resultado, fue exiliado por León V. [68] : 74–75 Murió en el exilio en 828. [68] : 74–75

En la primavera de 816, el monje constantinopolitano Atanasio de Paulopetrión fue torturado y exiliado por su iconofilismo por el emperador León V. [68] : 28 En 815, durante el reinado de León V, habiendo sido nombrado hegoumenos del monasterio de Kathara en Bitinia por el emperador Nicéforo I, Juan de Kathara fue exiliado y encarcelado primero en Pentadactylon, una fortaleza en Frigia , y luego en la fortaleza de Kriotauros en el thema bucelario . [68] : 55–56 En el reinado de Miguel II fue llamado de nuevo, pero exiliado de nuevo bajo Teófilo, siendo desterrado a Aphousia ( Avşa ) donde murió, probablemente en 835. [68] : 55–56

Eustratios de Agauros, monje y hegumenos del monasterio de Agauros al pie del monte Trichalikos, cerca del monte Olimpo de Prusa en Bitinia, fue forzado al exilio por las persecuciones de León V y Teófilo ( r. 829-842 ). [68] : 37–38 León V y Teófilo también persiguieron y exiliaron a Hilarión de Dalmatos, hijo de Pedro el Capadocio, que había sido nombrado hegumenos del monasterio de Dalmatos por el patriarca Nicéforo I. [68] : 48–49 A Hilarión se le permitió regresar a su puesto solo en la regencia de Teodora . [68] : 48–49 Los mismos emperadores también persiguieron a Miguel Synkellos , un monje árabe del monasterio de Mar Saba en Palestina que, como syncellus del patriarca de Jerusalén, había viajado a Constantinopla en nombre del patriarca Tomás I. [ 68] : 70–71 Tras el triunfo de la ortodoxia, Miguel declinó el patriarcado ecuménico y se convirtió en su lugar en el hegumenos del monasterio de Chora . [68] : 70–71

Según Teófanes Continuatus , el monje e iconógrafo armenio de origen jázaro Lázaro Zógrafo se negó a dejar de pintar iconos en el segundo período iconoclasta oficial. [68] : 61–62 Teófilo lo hizo torturar y le quemaron las manos con hierros calientes, aunque fue liberado por intercesión de la emperatriz Teodora y escondido en el Monasterio de Juan el Bautista tou Phoberou , donde pudo pintar una imagen del santo patrón. [68] : 61–62 Después de la muerte de Teófilo y el triunfo de la ortodoxia, Lázaro volvió a pintar la representación de Cristo en la Puerta de Caliza del Gran Palacio de Constantinopla . [68] : 61–62

Simeón el Estilita de Lesbos fue perseguido por su iconodulismo en el segundo período de la iconoclasia oficial. Fue encarcelado y exiliado, regresando a Lesbos solo después de que se restableciera la vernación de los iconos en 842. [68] : 32–33 El obispo Jorge de Mitilene, que pudo haber sido hermano de Simeón, fue exiliado de Constantinopla en 815 debido a su iconofilia. Pasó los últimos seis años de su vida en el exilio en una isla, probablemente una de las Islas Príncipe , muriendo en 820 o 821. [68] : 42–43 Las reliquias de Jorge fueron llevadas a Mitilene para ser veneradas después de la restauración de la iconodulidad a la ortodoxia bajo el patriarca Metodio I , durante la cual se escribió la hagiografía de Jorge. [68] : 42–43

El obispo Eutimio de Sardes fue víctima de varias persecuciones cristianas iconoclastas. Eutimio había sido exiliado previamente a Pantelaria por el emperador Nicéforo I ( r. 802-811 ), llamado de nuevo en 806, lideró la resistencia iconódula contra León V ( r. 813-820 ), y exiliado de nuevo a Tasos en 814. [68] : 38 Después de su llamado a Constantinopla en el reinado de Miguel II ( r. 820-829 ), fue nuevamente encarcelado y exiliado a la isla de San Andrés, frente al cabo Akritas ( Tuzla , Estambul). [68] : 38 Según la hagiografía del patriarca Metodio I de Constantinopla , que afirmó haber compartido el exilio de Eutimio y haber estado presente en su muerte, Teoctisto y otros dos funcionarios imperiales azotaron personalmente a Eutimio hasta la muerte a causa de su iconodulismo ; Teoctisto participó activamente en la persecución de los iconódulos bajo los emperadores iconoclastas, pero más tarde defendió la causa iconódula. [68] : 38, 68–69 [117] : 218 Teoctisto fue posteriormente venerado como santo en la Iglesia Ortodoxa Oriental , y figura en el Sinaxario de Constantinopla . [117] : 217–218 El último de los emperadores iconoclastas, Teófilo ( r. 829–842 ), fue rehabilitado póstumamente por la Iglesia ortodoxa iconódula por intervención de su esposa Teodora , quien afirmó que había tenido una conversión al iconodulismo en su lecho de muerte en presencia de Teoctisto y había dado 60 libras bizantinas de oro a cada una de sus víctimas en su testamento. [117] : 219 La rehabilitación del emperador iconoclasta fue una condición previa de su viuda para convocar el Concilio de Constantinopla en marzo de 843, en el que se restableció la veneración de los iconos a la ortodoxia y que se celebró como el Triunfo de la Ortodoxia . [117] : 219

Evaristos, pariente de Theoktistos Bryennios y monje del monasterio de Stoudios , fue exiliado al Quersoneso tracio ( península de Galípoli ) por su apoyo a su hegumenos Nicolás y a su patrón, el patriarca Ignacio de Constantinopla, cuando este último fue depuesto por Focio I en 858. [68] : 41, 72–73 Tanto Nicolás como Evaristos se exiliaron. [68] : 41, 72–73 Solo después de muchos años se le permitió a Evaristos regresar a Constantinopla para fundar un monasterio propio. [68] : 41, 72–73 El hegumenos Nicolás, que había acompañado a Evaristos al Quersoneso, fue restaurado en su puesto en el monasterio de Stoudios. [68] : 72–73 Partidario de Ignacio de Constantinopla y refugiado de la conquista musulmana de Sicilia , el monje José el Himnógrafo fue desterrado a Quersón desde Constantinopla tras la elevación de Focio, rival de Ignacio, en 858. Sólo después del fin del patriarcado de Focio se le permitió a José regresar a la capital y convertirse en el skeuophylax de la catedral de Santa Sofía. [68] : 57–58

Eutimio, monje, senador y sinquello favorecido por León VI ( r. 870-912 ), fue nombrado primero hegúmeno y luego, en 907, patriarca de Constantinopla por el emperador. Cuando León VI murió y Nicolás Místico fue llamado de nuevo al trono patriarcal, Eutimio fue exiliado. [68] : 38–40

El califato abasí fue menos tolerante con el cristianismo que los califas omeyas . [95] No obstante, los funcionarios cristianos continuaron siendo empleados en el gobierno, y los cristianos de la Iglesia de Oriente a menudo se encargaron de la traducción de la filosofía griega antigua y las matemáticas griegas . [95] Los escritos de al-Jahiz atacaron a los cristianos por ser demasiado prósperos, e indican que eran capaces de ignorar incluso las restricciones que les imponía el estado. [95] A finales del siglo IX, el patriarca de Jerusalén , Teodosio , escribió a su colega, el patriarca de Constantinopla Ignacio, que "son justos y no nos hacen ningún mal ni nos muestran ninguna violencia". [95]

Elías de Heliópolis , habiéndose mudado a Damasco desde Heliópolis ( Ba'albek ), fue acusado de apostasía del cristianismo después de asistir a una fiesta celebrada por un árabe musulmán, y se vio obligado a huir de Damasco a su ciudad natal, regresando ocho años después, donde fue reconocido y encarcelado por el " eparca ", probablemente el jurista al-Layth ibn Sa'd . [68] : 34 Después de negarse a convertirse al Islam bajo tortura, fue llevado ante el emir damasceno y pariente del califa al-Mahdi ( r. 775-785 ), Muhammad ibn-Ibrahim, quien prometió un buen trato si Elías se convertía. [68] : 34 Ante su reiterada negativa, Elías fue torturado y decapitado y su cuerpo quemado, cortado en pedazos y arrojado al río Chrysorrhoes (el Barada ) en 779 d.C. [68] : 34

_and_36_fathers_with_him.jpg/440px-Michael,_Abbot_in_Sebastia_(Armenia)_and_36_fathers_with_him.jpg)

Según el Sinaxario de Constantinopla , el hegumeno Miguel de Zobe y treinta y seis de sus monjes en el monasterio de Zobe cerca de Sebasteia ( Sivas ) fueron asesinados por una incursión en la comunidad. [68] : 70 El perpetrador fue el " emir de los agarenos ", "Alim", probablemente Ali ibn-Sulayman , un gobernador abasí que invadió el territorio romano en 785 d. C. [68] : 70 Baco el Joven fue decapitado en Jerusalén en 786-787 d. C. Baco era palestino, cuya familia, habiendo sido cristiana, había sido convertida al Islam por su padre. [68] : 29-30 Baco, sin embargo, permaneció criptocristiano y emprendió una peregrinación a Jerusalén, en la que fue bautizado y entró en el monasterio de Mar Saba . [68] : 29–30 La reunión con su familia provocó la reconversión de éstos al cristianismo y el juicio y ejecución de Baco por apostasía bajo el gobierno del emir Harthama ibn A'yan . [68] : 29–30

Después del saqueo de Amorium en 838 , la ciudad natal del emperador Teófilo ( r. 829-842 ) y su dinastía amoria , el califa al-Mu'tasim ( r. 833-842 ) tomó más de cuarenta prisioneros romanos. [68] : 41–42 Estos fueron llevados a la capital, Samarra , donde después de siete años de debates teológicos y reiteradas negativas a convertirse al Islam, fueron ejecutados en marzo de 845 bajo el califa al-Wathiq ( r. 842-847 ). [68] : 41–42 En una generación fueron venerados como los 42 Mártires de Amorium . Según su hagiógrafo Euodius, probablemente escribiendo dentro de una generación de los eventos, la derrota en Amorium debía atribuirse a Teófilo y su iconoclasia. [68] : 41–42 Según algunas hagiografías posteriores, incluida una de uno de varios escritores bizantinos medios conocidos como Miguel el Sinquellos, entre los cuarenta y dos estaban Kallistos, el doux del thema de Koloneia , y el heroico mártir Teodoro Karteros. [68] : 41–42

Durante la fase del siglo X de las guerras árabe-bizantinas , las victorias de los romanos sobre los árabes resultaron en ataques de la turba contra los cristianos, que se creía que simpatizaban con el estado romano. [95] Según Bar Hebraeus , el catholicus de la Iglesia de Oriente, Abraham III ( r. 906-937 ), escribió al gran visir que "nosotros, los nestorianos, somos amigos de los árabes y rezamos por sus victorias". [95] La actitud de los nestorianos "que no tienen otro rey que los árabes", la contrastó con la de la Iglesia Ortodoxa Griega, cuyos emperadores, dijo, "nunca habían dejado de hacer la guerra contra los árabes". [95] Entre 923 y 924, varias iglesias ortodoxas fueron destruidas por la violencia de las turbas en Ramla , Ascalón , Cesarea Marítima y Damasco . [95] En cada caso, según el cronista cristiano árabe melquita Eutiquio de Alejandría , el califa al-Muqtadir ( r. 908-932 ) contribuyó a la reconstrucción de la propiedad eclesiástica. [95]

A finales del siglo VIII, en el Imperio abasí, los musulmanes destruyeron dos iglesias y un monasterio cerca de Belén y masacraron a sus monjes. En el año 796, los musulmanes quemaron vivos a otros veinte monjes. En los años 809 y 813, varios monasterios, conventos e iglesias fueron atacados en Jerusalén y sus alrededores; cristianos, tanto hombres como mujeres, fueron violados en grupo y masacrados. En el año 929, el Domingo de Ramos, estalló otra ola de atrocidades; se destruyeron iglesias y se masacró a cristianos. Al-Maqrizi registra que en el año 936, “los musulmanes en Jerusalén se rebelaron y quemaron la Iglesia de la Resurrección [el Santo Sepulcro], que saquearon y destruyeron todo lo que pudieron de ella”. [118]

Según el Sinaxario de Constantinopla , Dounale-Esteban, tras haber viajado a Jerusalén, continuó su peregrinación a Egipto, donde fue arrestado por el emir local y, negándose a renunciar a sus creencias, murió en la cárcel alrededor del año 950. [ 68] : 33–34

Cuando Abd Allah ibn Tahir fue a sitiar Kaisum, la fortaleza de Nasr: «Había habido una gran opresión en todo el país porque los habitantes [los dhimmis cristianos] se vieron obligados a llevar provisiones al campamento; y en todos los lugares era tiempo de hambruna y escasez de todo tipo de cosas». Para protegerse de los cañones de sus atacantes, Nasr ibn Shabath y sus tropas árabes utilizaron una estratagema que ya se había probado en el sitio de Balis (utilizando a mujeres y niños cristianos como escudos humanos): obligaron a las mujeres cristianas y a sus niños a subir a las murallas para que quedaran expuestos como objetivos para los persas. Nasr utilizó la misma táctica en el segundo sitio de Kaisum. [119]

El califa Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ( r. 996-1021 ) persiguió a los cristianos. [120] Al-Hakim estaba "medio loco" y había perpetrado la única persecución general de cristianos por parte de musulmanes hasta las Cruzadas. [121] La madre de Al-Hakim era cristiana y él había sido criado principalmente por cristianos, e incluso durante la persecución, Al-Hakim empleó ministros cristianos en su gobierno. [122] Entre 1004 y 1014, el califa elaboró una legislación para confiscar la propiedad eclesiástica y quemar cruces; más tarde, ordenó que se construyeran pequeñas mezquitas sobre los tejados de las iglesias y, más tarde, decretó que las iglesias debían ser quemadas. [122] Los súbditos judíos y musulmanes del califa fueron sometidos a un tratamiento arbitrario similar. [122] Como parte de la persecución de al-Hakim, se informó que treinta mil iglesias fueron destruidas, y en 1009 el califa ordenó la demolición de la Iglesia del Santo Sepulcro en Jerusalén, con el pretexto de que el milagro anual del Fuego Santo en Pascua era una falsificación. [122] La persecución de al-Hakim y la demolición de la Iglesia del Santo Sepulcro impulsaron al Papa Sergio IV a emitir un llamamiento a los soldados para expulsar a los musulmanes de Tierra Santa, mientras que los cristianos europeos se dedicaron a una persecución vengativa de los judíos, a quienes conjeturaban que eran de alguna manera responsables de las acciones de al-Hakim. [123] En la segunda mitad del siglo XI, los peregrinos trajeron a casa noticias de cómo el ascenso de los turcos y su conflicto con los egipcios aumentaron la persecución de los peregrinos cristianos. [123]

En 1013, por intervención del emperador Basilio II ( r. 960-1025 ), los cristianos recibieron permiso para abandonar el territorio fatimí. [122] Sin embargo, en 1016, el califa fue proclamado divino, alejando a sus súbditos musulmanes al prohibir el hajj y el ayuno del ramadán , y provocando que volviera a favorecer a los cristianos. [122] En 1017, al-Hakim emitió una orden de tolerancia con respecto a los cristianos y los judíos, mientras que al año siguiente la propiedad eclesiástica confiscada fue devuelta a la Iglesia, incluidos los materiales de construcción confiscados por las autoridades de los edificios demolidos. [122]

En 1027, el emperador Constantino VIII ( r. 962-1028 ) concluyó un tratado con Salih ibn Mirdas , el emir de Alepo , permitiendo al emperador reparar la Iglesia del Santo Sepulcro y permitir que los cristianos obligados a convertirse al Islam bajo al-Hakim regresaran al cristianismo. [122] Aunque el tratado fue reconfirmado en 1036, la construcción real del santuario comenzó solo a fines de la década de 1040, bajo el emperador Constantino IX Monómaco ( r. 1042-1055 ). [122] Según al-Maqdisi , los cristianos parecían tener en gran medida el control de Tierra Santa, y se rumoreaba que el propio emperador, según Nasir Khusraw , había estado entre los muchos peregrinos cristianos que acudieron al Santo Sepulcro. [122]

El sultán Alp Arslan prometió: “Consumiré con la espada a todas aquellas personas que veneran la cruz, y todas las tierras de los cristianos serán esclavizadas”. [124] Alp Arslan ordenó a los turcos: [125]

De ahora en adelante, todos ustedes serán como cachorros de león y crías de águila, corriendo por el campo día y noche, matando a los cristianos y sin tener piedad de la nación romana.

Se decía que “los emires se extendieron como langostas por la faz de la tierra”, [126] invadiendo cada rincón de Anatolia, saqueando algunas de las ciudades más importantes de la cristiandad antigua, incluyendo Éfeso, hogar de San Juan Evangelista; Nicea, donde se formuló el credo de la cristiandad en 325; y Antioquía, la sede original de San Pedro, y esclavizaron a muchos. [127] [128] [129] Según el historiador francés J. Laurent, se informó de que cientos de miles de cristianos nativos de Anatolia fueron masacrados o esclavizados durante las invasiones de Anatolia por los turcos seléucidas. [130] [131]

La destrucción y profanación de iglesias se generalizó durante las invasiones turcas de Anatolia, que causaron enormes daños a las fundaciones eclesiásticas en toda Asia Menor: [132]

Incluso antes de la batalla de Manzikert, las incursiones turcas dieron como resultado el saqueo de las famosas iglesias de San Basilio en Cesarea y del Arcángel Miguel en Chonae. En la década posterior a 1071, la destrucción de iglesias y la huida del clero se generalizaron. Las iglesias fueron saqueadas y destruidas con frecuencia. Las iglesias de San Focas en Sinope y Nicolás en Myra, ambos importantes centros de peregrinación, fueron destruidas. Los monasterios de Mt. Latrus, Strobilus y Elanoudium en la costa occidental fueron saqueados y los monjes expulsados durante las primeras invasiones, de modo que las fundaciones monásticas en esta área fueron completamente abandonadas hasta la reconquista bizantina y el amplio apoyo de los sucesivos emperadores bizantinos una vez más las reconstituyó. Los griegos se vieron obligados a rodear la iglesia de San Juan en Éfeso con murallas para protegerla de los turcos. La interrupción de la vida religiosa activa en las comunidades monásticas rupestres de Capadocia también está indicada para el siglo XII.

Las noticias de la gran tribulación y persecución de los cristianos orientales llegaron a los cristianos europeos occidentales en los pocos años posteriores a la batalla de Manzikert. Un testigo ocular franco dice: "Por todas partes [los turcos musulmanes] devastaron ciudades y castillos junto con sus asentamientos. Las iglesias fueron arrasadas hasta los cimientos. De los clérigos y monjes que capturaron, algunos fueron asesinados mientras que otros fueron entregados con una maldad indescriptible, sacerdotes y todo, a su terrible dominio y las monjas -¡ay de lo triste que fue!- fueron sometidas a sus lujurias". [133] En una carta al conde Roberto de Flandes, el emperador bizantino Alejo I Comneno escribe: [134]

Los lugares sagrados son profanados y destruidos de innumerables maneras. Matronas nobles y sus hijas, despojadas de todo, son violadas una tras otra, como animales. Algunos [de sus atacantes] colocan descaradamente a vírgenes delante de sus propias madres y las obligan a cantar canciones malvadas y obscenas hasta que terminan de hacer lo que quieren con ellas... hombres de todas las edades y descripciones, niños, jóvenes, ancianos, nobles, campesinos y lo que es aún peor y aún más angustioso, clérigos y monjes y, ¡ay de los males sin precedentes!, incluso los obispos son contaminados con el pecado de sodomía y ahora se pregona en todas partes que un obispo ha sucumbido a este pecado abominable.

En un poema, Malik Danishmend se jacta: “Soy Al Ghazi Danishmend, el destructor de iglesias y torres”. La destrucción y el saqueo de iglesias ocupan un lugar destacado en su poema. Otra parte del poema habla de la conversión simultánea de 5.000 personas al Islam y del asesinato de otras 5.000. [135]

Michael the Syrian wrote: “As the Turks were ruling the lands of Syria and Palestine, they inflicted injuries on Christians who went to pray in Jerusalem, beat them, pillaged them, and levied the poll tax [jizya]. Every time they saw a caravan of Christians, particularly of those from Rome and the lands of Italy, they made every effort to cause their death in diverse ways".[136] Such was the fate German pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1064. According to one of the surviving pilgrims:[137]

Accompanying this journey was a noble abbess of graceful body and of a religious outlook. Setting aside the cares of the sisters committed to her and against the advice of the wise, she undertook this great and dangerous pilgrimage. The pagans captured her, and the sight of all, these shameless men raped her until she breathed her last, to the dishonor of all Christians. Christ's enemies performed such abuses and others like them on the christians.

After the Seljuks invaded Anatolia and the levant, every Anatolian village they controlled along the route to Jerusalem began exacting tolls on Christian pilgrims. In principle the Seljuks allowed Christian pilgrims access to Jerusalem, but they often imposed huge ransoms and condoned local attacks against Christians. many pilgrims were seized and sold into slavery while others were tortured (seemingly for entertainment). Soon only very large, well-armed and wealthy groups would dare attempt a pilgrimage, and even so, many died and many more turned back.The pilgrims that survived these extremely dangerous journeys, “returned to the West weary and impoverished, with a dreadful tale to tell.”[138][139]

In the year 1064, 7,000 pilgrims lead by Bishop Gunther of Bamberg were ambushed by Muslims near Caesarea Maritima, and two-thirds of the pilgrims were slaughtered.[140]