Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, illegitimacy, also known as bastardy, has been the status of a child born outside marriage, such a child being known as a bastard, a love child, a natural child, or illegitimate. In Scots law, the terms natural son and natural daughter carry the same implications.

The importance of legitimacy has decreased substantially in Western developed countries since the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s and the declining influence of Christian churches, especially Catholic, Anglican, and Lutherans, in family and social life.

Births outside marriage now represent majorities in multiple countries in Western Europe, the Americas, and many former European colonies.[citation needed]

England's Statute of Merton (1235) stated, regarding illegitimacy: "He is a bastard that is born before the marriage of his parents."[1] This definition also applied to situations when a child's parents could not marry, as when one or both were already married or when the relationship was incestuous.

The Poor Act 1575 formed the basis of English bastardy law. Its purpose was to punish a bastard child's mother and putative father, and to relieve the parish from the cost of supporting mother and child. "By an act of 1576 (18 Elizabeth C. 3), it was ordered that bastards should be supported by their putative fathers, though bastardy orders in the quarter sessions date from before this date. If the genitor could be found, then he was put under very great pressure to accept responsibility and to maintain the child."[2]

Under English law, a bastard could not inherit real property and could not be legitimized by the subsequent marriage of father to mother. There was one exception: when his father subsequently married his mother, and an older illegitimate son (a "bastard eignè") took possession of his father's lands after his death, he would pass the land on to his own heirs on his death, as if his possession of the land had been retroactively converted into true ownership. A younger non-bastard brother (a "mulier puisnè") would have no claim to the land.[3]

There were many "natural children" of Scotland's monarchy granted positions which founded prominent families. In the 14th century, Robert II of Scotland gifted one of his illegitimate sons estates in Bute, founding the Stewarts of Bute, and similarly a natural son of Robert III of Scotland was ancestral to the Shaw Stewarts of Greenock.[4]

In Scots law an illegitimate child, a "natural son" or "natural daughter", would be legitimated by the subsequent marriage of his parents, provided they had been free to marry at the date of the conception.[5][6] The Legitimation (Scotland) Act 1968 extended legitimation by the subsequent marriage of the parents to children conceived when their parents were not free to marry, but this was repealed in 2006 by the amendment of section 1 of the Law Reform (Parent and Child) (Scotland) Act 1986 (as amended in 2006) which abolished the status of illegitimacy stating that "(1) No person whose status is governed by Scots law shall be illegitimate ...".

The Legitimacy Act 1926[7] of England and Wales legitimised the birth of a child if the parents subsequently married each other, provided that they had not been married to someone else in the meantime. The Legitimacy Act 1959 extended the legitimisation even if the parents had married others in the meantime and applied it to putative marriages which the parents incorrectly believed were valid. Neither the 1926 nor 1959 Acts changed the laws of succession to the British throne and succession to peerage and baronetcy titles. In Scotland children legitimated by the subsequent marriage of their parents have always been entitled to succeed to peerages and baronetcies and the Legitimation (Scotland) Act 1968 extended this right to children conceived when their parents were not free to marry.[8] The Family Law Reform Act 1969 (c. 46) allowed a bastard to inherit on the intestacy of his parents. In canon and in civil law, the offspring of putative marriages have also been considered legitimate.[9]

Since December 2003 in England and Wales, April 2002 in Northern Ireland and May 2006 in Scotland, an unmarried father has parental responsibility if he is listed on the birth certificate.[10]

In the United States, in the early 1970s a series of Supreme Court decisions held that most common-law disabilities imposed upon illegitimacy were invalid as violations of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[11] Still, children born out of wedlock may not be eligible for certain federal benefits (e.g., automatic naturalization when the father becomes a US citizen) unless the child has been legitimized in the appropriate jurisdiction.[12][13]

Many other countries have legislatively abolished any legal disabilities of a child born out of wedlock.[14][citation needed]

In France, legal reforms regarding illegitimacy began in the 1970s, but it was only in the 21st century that the principle of equality was fully upheld (through Act no. 2002-305 of 4 March 2002, removing mention of "illegitimacy" — filiation légitime and filiation naturelle; and through law no. 2009-61 of 16 January 2009).[15][16][17] In 2001, France was forced by the European Court of Human Rights to change several laws that were deemed discriminatory, and in 2013 the Court ruled that these changes must also be applied to children born before 2001.[18]

In some countries, the family law itself explicitly states that there must be equality between the children born outside and inside marriage: in Bulgaria, for example, the new 2009 Family Code lists "equality of the born during the matrimony, out of matrimony and of the adopted children" as one of the principles of family law.[19]

The European Convention on the Legal Status of Children Born out of Wedlock[20] came into force in 1978. Countries which ratify it must ensure that children born outside marriage are provided with legal rights as stipulated in the text of this convention. The convention was ratified by the UK in 1981 and by Ireland in 1988.[21]

In later years, the inheritance rights of many illegitimate children have improved, and changes of laws have allowed them to inherit properties.[22] More recently, the laws of England have been changed to allow illegitimate children to inherit entailed property, over their legitimate brothers and sisters.[citation needed]

Despite the decreasing legal relevance of illegitimacy, an important exception may be found in the nationality laws of many countries, which do not apply jus sanguinis (nationality by citizenship of a parent) to children born out of wedlock, particularly in cases where the child's connection to the country lies only through the father. This is true, for example, of the United States,[23] and its constitutionality was upheld in 2001 by the Supreme Court in Nguyen v. INS.[24] In the UK, the policy was changed so that children born after 1 July 2006 could receive British citizenship from their father if their parents were unmarried at the time of the child's birth; illegitimate children born before this date cannot receive British citizenship through their father.[25]

Legitimacy also continues to be relevant to hereditary titles, with only legitimate children being admitted to the line of succession. Some monarchs, however, have succeeded to the throne despite the controversial status of their legitimacy. For example, Elizabeth I succeeded to the throne though she was legally held illegitimate as a result of her parents' marriage having been annulled after her birth.[26] Her older half-sister Mary I had acceded to the throne before her in a similar circumstance: her parents' marriage had been annulled in order to allow her father to marry Elizabeth's mother.

Annulment of marriage does not currently change the status of legitimacy of children born to the couple during their putative marriage, i.e., between their marriage ceremony and the legal annulment of their marriage. For example, canon 1137 of the Roman Catholic Church's Code of Canon Law specifically affirms the legitimacy of a child born to a marriage that is declared null following the child's birth.[27]

The Catholic Church is also changing its attitude toward unwed mothers and baptism of the children. In criticizing the priests who refused to baptize out-of-wedlock children, Pope Francis argued that the mothers had done the right thing by giving life to the child and should not be shunned by the church:[28][29][30]

In our ecclesiastical region there are priests who don't baptise the children of single mothers because they weren't conceived in the sanctity of marriage. These are today's hypocrites. Those who clericalise the church. Those who separate the people of God from salvation. And this poor girl who, rather than returning the child to sender, had the courage to carry it into the world, must wander from parish to parish so that it's baptised!

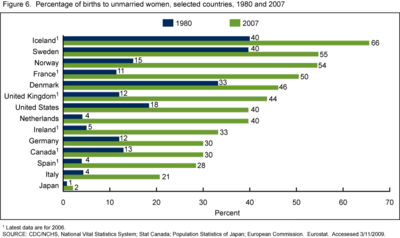

The proportion of children born outside marriage has been rising since the turn of the 21st century in most European Union countries,[49][50] North America, and Australia.[51] In Europe, besides the low levels of fertility rates and the delay of motherhood, another factor that now characterizes fertility is the growing percentage of births outside marriage. In the EU, this phenomenon has been on the rise in recent years in almost every country; and in eight EU countries, mostly in northern Europe, as well as in Iceland outside of the EU, it already accounts for the majority of births.[50]

In 2009, 41% of children born in the United States were born to unmarried mothers, a significant increase from the 5% of half a century earlier. That includes 73% of non-Hispanic black children, 53% of Hispanic children (of all races), and 29% of non-Hispanic white children.[52][53] In 2020, the proportion was almost similar, with 40.5% of children born in the United States being born to unmarried mothers.[54]

In April 2009, the National Center for Health Statistics announced that nearly 40 percent of American infants born in 2007 were born to an unwed mother; that of 4.3 million children, 1.7 million were born to unmarried parents, a 25 percent increase from 2002.[55] Most births to teenagers in the United States (86% in 2007) are nonmarital; in 2007, 60% of births to women 20–24, and nearly one-third of births to women 25–29, were nonmarital.[31] In 2007, teenagers accounted for just 23% of non-marital births, down steeply from 50% in 1970.[31]

In 2014, 42% of all births in the 28 EU countries were nonmarital.[56] The percentage was also 42% in 2018.[50] In 2018, births outside of marriage represented the majority of births in eight EU member states: France (60%), Bulgaria (59%), Slovenia (58%), Portugal (56%), Sweden (55%), Denmark and Estonia (both 54%), and the Netherlands (52%). The lowest percentage were in Greece, Cyprus, Croatia, Poland and Lithuania, with a percentage of under 30%.[50]

To a certain degree, religion (the religiosity of the population - see religion in Europe) correlates with the proportion of non-marital births (e.g., Greece, Cyprus, Croatia have a low percentage of births outside marriage), but this is not always the case: Portugal (56% in 2018[50]) is among the most religious countries in Europe.

The proportion of non-marital births is also approaching half in the Czech Republic (48.5%. in 2021[57]), the