A Turing machine is a mathematical model of computation describing an abstract machine[1] that manipulates symbols on a strip of tape according to a table of rules.[2] Despite the model's simplicity, it is capable of implementing any computer algorithm.[3]

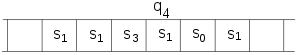

The machine operates on an infinite[4] memory tape divided into discrete cells,[5] each of which can hold a single symbol drawn from a finite set of symbols called the alphabet of the machine. It has a "head" that, at any point in the machine's operation, is positioned over one of these cells, and a "state" selected from a finite set of states. At each step of its operation, the head reads the symbol in its cell. Then, based on the symbol and the machine's own present state, the machine writes a symbol into the same cell, and moves the head one step to the left or the right,[6] or halts the computation. The choice of which replacement symbol to write, which direction to move the head, and whether to halt is based on a finite table that specifies what to do for each combination of the current state and the symbol that is read. Like a real computer program, it is possible for a Turing machine to go into an infinite loop which will never halt.

The Turing machine was invented in 1936 by Alan Turing,[7][8] who called it an "a-machine" (automatic machine).[9] It was Turing's doctoral advisor, Alonzo Church, who later coined the term "Turing machine" in a review.[10] With this model, Turing was able to answer two questions in the negative:

Thus by providing a mathematical description of a very simple device capable of arbitrary computations, he was able to prove properties of computation in general—and in particular, the uncomputability of the Entscheidungsproblem ('decision problem').[13]

Turing machines proved the existence of fundamental limitations on the power of mechanical computation.[14] While they can express arbitrary computations, their minimalist design makes them too slow for computation in practice: real-world computers are based on different designs that, unlike Turing machines, use random-access memory.

Turing completeness is the ability for a computational model or a system of instructions to simulate a Turing machine. A programming language that is Turing complete is theoretically capable of expressing all tasks accomplishable by computers; nearly all programming languages are Turing complete if the limitations of finite memory are ignored.

A Turing machine is an idealised model of a central processing unit (CPU) that controls all data manipulation done by a computer, with the canonical machine using sequential memory to store data. Typically, the sequential memory is represented as a tape of infinite length on which the machine can perform read and write operations.

In the context of formal language theory, a Turing machine (automaton) is capable of enumerating some arbitrary subset of valid strings of an alphabet. A set of strings which can be enumerated in this manner is called a recursively enumerable language. The Turing machine can equivalently be defined as a model that recognises valid input strings, rather than enumerating output strings.

Given a Turing machine M and an arbitrary string s, it is generally not possible to decide whether M will eventually produce s. This is due to the fact that the halting problem is unsolvable, which has major implications for the theoretical limits of computing.

The Turing machine is capable of processing an unrestricted grammar, which further implies that it is capable of robustly evaluating first-order logic in an infinite number of ways. This is famously demonstrated through lambda calculus.

A Turing machine that is able to simulate any other Turing machine is called a universal Turing machine (UTM, or simply a universal machine). Another mathematical formalism, lambda calculus, with a similar "universal" nature was introduced by Alonzo Church. Church's work intertwined with Turing's to form the basis for the Church–Turing thesis. This thesis states that Turing machines, lambda calculus, and other similar formalisms of computation do indeed capture the informal notion of effective methods in logic and mathematics and thus provide a model through which one can reason about an algorithm or "mechanical procedure" in a mathematically precise way without being tied to any particular formalism. Studying the abstract properties of Turing machines has yielded many insights into computer science, computability theory, and complexity theory.

In his 1948 essay, "Intelligent Machinery", Turing wrote that his machine consists of:

...an unlimited memory capacity obtained in the form of an infinite tape marked out into squares, on each of which a symbol could be printed. At any moment there is one symbol in the machine; it is called the scanned symbol. The machine can alter the scanned symbol, and its behavior is in part determined by that symbol, but the symbols on the tape elsewhere do not affect the behavior of the machine. However, the tape can be moved back and forth through the machine, this being one of the elementary operations of the machine. Any symbol on the tape may therefore eventually have an innings.[15]

— Turing 1948, p. 3[16]

The Turing machine mathematically models a machine that mechanically operates on a tape. On this tape are symbols, which the machine can read and write, one at a time, using a tape head. Operation is fully determined by a finite set of elementary instructions such as "in state 42, if the symbol seen is 0, write a 1; if the symbol seen is 1, change into state 17; in state 17, if the symbol seen is 0, write a 1 and change to state 6;" etc. In the original article ("On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem", see also references below), Turing imagines not a mechanism, but a person whom he calls the "computer", who executes these deterministic mechanical rules slavishly (or as Turing puts it, "in a desultory manner").

More explicitly, a Turing machine consists of:

In the 4-tuple models, erasing or writing a symbol (aj1) and moving the head left or right (dk) are specified as separate instructions. The table tells the machine to (ia) erase or write a symbol or (ib) move the head left or right, and then (ii) assume the same or a new state as prescribed, but not both actions (ia) and (ib) in the same instruction. In some models, if there is no entry in the table for the current combination of symbol and state, then the machine will halt; other models require all entries to be filled.

Every part of the machine (i.e. its state, symbol-collections, and used tape at any given time) and its actions (such as printing, erasing and tape motion) is finite, discrete and distinguishable; it is the unlimited amount of tape and runtime that gives it an unbounded amount of storage space.

Following Hopcroft & Ullman (1979, p. 148), a (one-tape) Turing machine can be formally defined as a 7-tuple where

A relatively uncommon variant allows "no shift", say N, as a third element of the set of directions .

The 7-tuple for the 3-state busy beaver looks like this (see more about this busy beaver at Turing machine examples):