Los pueblos turcos son un conjunto de diversos grupos étnicos del oeste , centro , este y norte de Asia , así como de partes de Europa , que hablan lenguas turcas . [37] [38]

Según los historiadores y lingüistas, la lengua proto-turca se originó en Asia central y oriental, [39] potencialmente en la región de Altai-Sayan , Mongolia o Tuva . [40] [41] [42] Inicialmente, los hablantes de proto-turco eran potencialmente cazadores-recolectores y agricultores; más tarde se convirtieron en pastores nómadas . [43] Los grupos turcos tempranos y medievales exhibieron una amplia gama de apariencias físicas y orígenes genéticos tanto de Asia oriental como de Eurasia occidental, en parte a través del contacto a largo plazo con pueblos vecinos como los pueblos iraníes , mongoles , tocarios , urálicos y yeniseos . [44]

A lo largo de la historia, muchos grupos étnicos muy diferentes se han convertido en parte de los pueblos turcos a través del cambio de idioma , la aculturación , la conquista , el mestizaje , la adopción y la conversión religiosa . [1] Sin embargo, los pueblos turcos comparten, en diversos grados, características no lingüísticas como rasgos culturales, ascendencia de un acervo genético común y experiencias históricas. [1] Algunos de los grupos étnicos turcos modernos más notables incluyen al pueblo altai , azerbaiyanos , chuvasios , gagauzes , kazajos , kirguís , turcomanos , turcomanos , tuvanos , uigures , uzbekos y yakutos .

.jpg/440px-Dīwān_Lughāt_al-Turk_(original).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Turkic_Head_of_Koltegin_Statue_(35324303410).jpg)

La primera mención conocida del término turco ( antiguo turco : 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 Türük o 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰:𐰜𐰇𐰛 Kök Türük , chino :突厥, pinyin : Tūjué < chino medio * tɦut-kyat < * dwət-kuɑt , antiguo tibetano : drugu ) [45] [46] [ 47] [48] se aplicaba a un solo grupo turco, a saber, los Göktürks , [49] que también fueron mencionados, como türüg ~ török , en la inscripción Khüis Tolgoi del siglo VI , probablemente no más tarde del 587 d. C. [50] [51] [52] Una carta de Ishbara Qaghan al emperador Wen de Sui en 585 lo describió como "el Gran Kan Turco". [53] [54] Las inscripciones Bugut (584 d. C.) y Orkhon (735 d. C.) utilizan los términos Türküt , Türk y Türük . [55]

Durante el siglo I d. C., Pomponio Mela se refiere a los Turcae en los bosques al norte del Mar de Azov , y Plinio el Viejo enumera a los Tyrcae entre los pueblos de la misma zona. [56] [57] [58] Sin embargo, el arqueólogo inglés Ellis Minns sostuvo que Tyrcae Τῦρκαι es "una corrección falsa" para Iyrcae Ἱύρκαι, un pueblo que habitó más allá de Thyssagetae , según Heródoto ( Historias , iv. 22), y probablemente eran antepasados ugrios de los magiares . [59] Hay referencias a ciertos grupos en la antigüedad cuyos nombres podrían haber sido transcripciones extranjeras de Tür(ü)k , como Togarma , Turukha / Turuška , Turukku , etc. Pero la brecha de información es tan sustancial que no es posible establecer ninguna conexión entre estos antiguos pueblos y los turcos modernos. [60] [61]

El Libro chino de Zhou (siglo VII) presenta una etimología del nombre Turk como derivado de 'casco', explicando que este nombre proviene de la forma de una montaña donde trabajaban en las montañas de Altai . [62] El erudito húngaro András Róna-Tas (1991) señaló una palabra Khotanese-Saka, tturakä 'tapa', semánticamente estirable a 'casco', como una posible fuente para esta etimología popular, sin embargo, Golden piensa que esta conexión requiere más datos. [63]

Se acepta generalmente que el nombre Türk se deriva en última instancia del término de migración turco antiguo [64] 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 Türük / Törük , [65] que significa 'creado, nacido' [66] o 'fuerte'. [67] El turkólogo Peter B. Golden está de acuerdo en que el término Turk tiene raíces en el turco antiguo , [68] pero no está convencido por los intentos de vincular Dili , Dingling , Chile , Tele y Tiele , que posiblemente transcribieron * tegrek (probablemente significa ' carro '), a Tujue , que se transcribió a Türküt . [69]

Los eruditos, incluidos Toru Haneda, Onogawa Hidemi y Geng Shimin, creían que Di , Dili , Dingling , Chile y Tujue provenían de la palabra turca Türk , que significa 'poderoso' y 'fuerza', y su forma plural es Türküt . [70] Aunque Gerhard Doerfer apoya la propuesta de que türk significa 'fuerte' en general, Gerard Clauson señala que "la palabra türk nunca se usa en el sentido generalizado de 'fuerte'" y que türk era originalmente un sustantivo y significaba "'el punto culminante de la madurez' (de una fruta, ser humano, etc.), pero se usaba más a menudo como un [adjetivo] que significa (de una fruta) 'recién madura'; (de un ser humano) 'en la flor de la vida, joven y vigoroso'". [71] Hakan Aydemir (2022) también sostiene que Türk originalmente no significaba "fuerte, poderoso" sino "reunido; unido, aliado, confederado" y se derivaba del verbo preprototurco * türü " amontonar, recolectar, reunir, reunir". [72]

Los primeros pueblos de habla turca identificables en fuentes chinas son los kirguises de Yenisei y los xinli , ubicados en el sur de Siberia. [73] [74] [nota 2] Otro ejemplo de una población turca temprana sería el de los dingling . [79] [80] [81]

En la Antigüedad tardía, así como en la Edad Media , el nombre "escitas" se utilizó en la literatura grecorromana y bizantina para varios grupos de " bárbaros " nómadas que vivían en la estepa póntico-caspia y que no estaban relacionados con los escitas reales. [82] [83] Los cronistas europeos medievales incluyeron a varios pueblos turcos de la estepa euroasiática como "escitas". Entre el 400 d. C. y el siglo XVI, las fuentes bizantinas utilizan el nombre Σκύθαι ( Skuthai ) en referencia a doce pueblos turcos diferentes. [84]

En el idioma turco moderno que se utiliza en la República de Turquía, se hace una distinción entre "turcos" y "pueblos túrquicos" en términos generales: el término Türk corresponde específicamente a los pueblos "de habla turca" (en este contexto, "de habla turca" se considera lo mismo que "de habla túrquica"), mientras que el término Türki se refiere en general a los pueblos de las "repúblicas túrquicas" modernas ( Türki Cumhuriyetler o Türk Cumhuriyetleri ). Sin embargo, el uso correcto del término se basa en la clasificación lingüística para evitar cualquier sentido político . En resumen, el término Türki puede usarse para Türk o viceversa. [85]

Se ha postulado una posible ascendencia proto-turca, al menos parcial, [88] [89] [90] [91] [92] [93] para los xiongnu , los hunos y los ávaros de Panonia , así como para los tuoba y los rouran , que eran de ascendencia protomongólica donghu . [94] [95] [96] [97] así como para los tártaros , supuestos descendientes de los rouran. [98] [99] [nota 6]

Las lenguas túrquicas constituyen una familia lingüística de unas 30 lenguas, habladas en una vasta zona desde Europa del Este y el Mediterráneo , hasta Siberia y Manchuria y hasta Oriente Medio. Unos 170 millones de personas tienen una lengua túrquica como lengua materna; [101] otros 20 millones de personas hablan una lengua túrquica como segunda lengua . La lengua túrquica con mayor número de hablantes es el turco propiamente dicho , o turco de Anatolia , cuyos hablantes representan alrededor del 40% de todos los hablantes de turco. [102] Más de un tercio de estos son turcos étnicos de Turquía , que viven predominantemente en Turquía propiamente dicha y en áreas anteriormente dominadas por los otomanos del sur y este de Europa y Asia occidental ; así como en Europa occidental, Australia y las Américas como resultado de la inmigración. El resto del pueblo turco se concentra en Asia central, Rusia, el Cáucaso , China y el norte de Irak.

Tradicionalmente, se ha considerado que la familia de lenguas túrquicas forma parte de la familia de lenguas altaicas propuesta . [103] Sin embargo, desde la década de 1950, una mayoría de lingüistas ha rechazado la propuesta, después de que se descubriera que los supuestos cognados no eran válidos, no se encontraran cambios de sonido hipotéticos y se descubriera que las lenguas túrquicas y mongólicas convergían en lugar de divergir a lo largo de los siglos. Los oponentes de la teoría propusieron que las similitudes se deben a influencias lingüísticas mutuas entre los grupos en cuestión. [104] [105] [106] [107] [108]

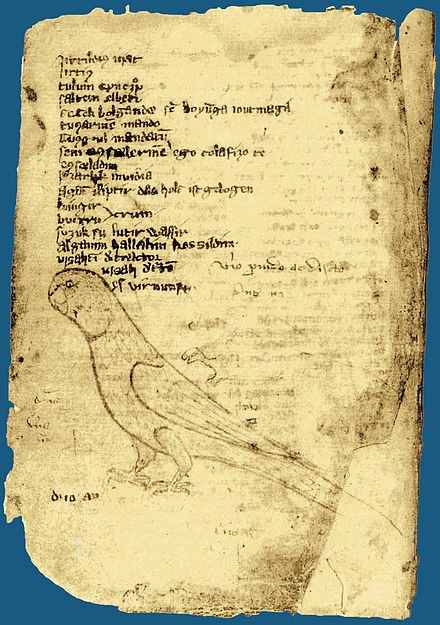

Los alfabetos turcos son conjuntos de alfabetos relacionados con letras (antes conocidas como runas ), utilizados para escribir principalmente en lenguas turcas . Se encontraron inscripciones en alfabetos turcos en Mongolia . La mayoría de las inscripciones conservadas datan de entre los siglos VIII y X d. C.

Las primeras inscripciones turcas datadas y leídas con certeza datan del siglo VIII, y los alfabetos fueron generalmente reemplazados por el antiguo alfabeto uigur en Asia oriental y central , la escritura árabe en Asia central y occidental, el cirílico en Europa oriental y en los Balcanes, y el alfabeto latino en Europa central. El último uso registrado del alfabeto turco se registró en Hungría, en Europa central, en 1699 d. C.

Las escrituras rúnicas turcas , a diferencia de otras escrituras tipológicamente cercanas del mundo, no tienen una paleografía uniforme como, por ejemplo, las escrituras rúnicas góticas , conocidas por su excepcional uniformidad de lenguaje y paleografía. [109] Los alfabetos turcos se dividen en cuatro grupos, el más conocido de los cuales es la versión Orkhon del grupo Enisei. La escritura Orkhon es el alfabeto utilizado por los Göktürks desde el siglo VIII para registrar la antigua lengua turca . Más tarde fue utilizado por el Imperio uigur ; se conoce una variante de Yenisei a partir de inscripciones kirguisas del siglo IX , y es probable que tenga primos en el valle de Talas de Turkestán y en la antigua escritura húngara del siglo X. Irk Bitig es el único texto manuscrito completo conocido escrito en la antigua escritura turca. [110]

Los orígenes de los pueblos turcos han sido un tema de mucha discusión. [111] [112] Peter Benjamin Golden propone dos ubicaciones para el Urheimat proto-turco: la región meridional de Altai-Sayan , [40] y en el sur de Siberia , desde el lago Baikal hasta el este de Mongolia . [113] Otros estudios sugirieron una presencia temprana de pueblos turcos en Mongolia, [114] [41] o Tuva . [42]

Un posible vínculo genealógico de las lenguas túrquicas con las lenguas mongólicas y tungúsicas, específicamente una patria hipotética en Manchuria , como la propuesta en la hipótesis transeurasiática , de Martine Robbeets , ha recibido apoyo pero también críticas, con oponentes atribuyendo similitudes al contacto a largo plazo. [115] [116] [117] Los proto-hablantes túrquicos pueden estar vinculados a las sociedades agrícolas neolíticas del este de Asia en el noreste de China , que se asociarán con la cultura Xinglongwa y la cultura Hongshan que la siguió , basándose en diversos grados de sustrato genético específico del este de Asia entre los hablantes túrquicos modernos. [118] [119] [120] Según los historiadores, "la estrategia de subsistencia proto-túrquica incluía un componente agrícola, una tradición que en última instancia se remonta al origen de la agricultura del mijo en el noreste de China". [118] [119] [120] Sin embargo, esta visión es cuestionada por otros genetistas, quienes no encontraron evidencia de una "ascendencia neolítica Hongshan" compartida, sino, por el contrario, una ascendencia neolítica primaria del noreste asiático antiguo (ANA) de la región de Amur , lo que apoya un origen del noreste asiático en lugar de Manchuria. [121]

Alrededor de 2200 a. C., los ancestros (agrícolas) de los pueblos turcos probablemente migraron hacia el oeste, a Mongolia , donde adoptaron un estilo de vida pastoral, en parte tomado de los pueblos iraníes . Dado que los pueblos nómadas como los xiongnu , los rouran y los xianbei comparten una ascendencia genética subyacente "que se encuentra dentro o cerca del acervo genético del noreste de Asia", es probable que la lengua proto-túrquica se originara en el noreste de Asia. [123]

Los datos genéticos han demostrado que casi todos los pueblos turcos modernos conservan al menos algún ancestro compartido asociado con poblaciones del "Siberia meridional y Mongolia" (SSM), lo que respalda a esta región como la "Patria del Asia interior (IAH) de los portadores pioneros de las lenguas turcas" que posteriormente se expandieron a Asia central. La principal expansión turca tuvo lugar durante los siglos V al XVI, superponiéndose parcialmente con el período del Imperio mongol . Según los tramos de IBD de una sola ruta, la población ancestral turca común vivió antes de estos eventos migratorios y probablemente provenga de una población de origen similar a la de los pueblos mongoles más al este. Los datos históricos sugieren que el período del Imperio mongol actuó como una fuerza secundaria de "turquificación", ya que la conquista mongola "no implicó reasentamientos masivos de mongoles sobre los territorios conquistados. En cambio, la maquinaria de guerra mongol fue aumentada progresivamente por varias tribus turcas a medida que se expandían, y de esta manera los pueblos turcos finalmente reforzaron su expansión sobre la estepa euroasiática y más allá". [112]

Un estudio de polimorfismo autosómico de un solo nucleótido de 2018 sugirió que la estepa euroasiática pasó lentamente de grupos de habla indoeuropea e iraní con ascendencia euroasiática mayoritariamente occidental a una ascendencia creciente del este de Asia con grupos turcos y mongoles en los últimos 4000 años, incluidas extensas migraciones turcas fuera de Mongolia y una lenta asimilación de las poblaciones locales. [124] [120] Un estudio de 2022 sugirió que las poblaciones turcas y mongoles en Asia Central se formaron a través de eventos de mezcla durante la Edad del Hierro entre " un grupo indoiraní local y un grupo del sur de Siberia o mongol con una alta ascendencia del este de Asia (alrededor del 60%)". Los turcomanos de hoy en día forman un caso atípico entre los hablantes de turco de Asia Central con una frecuencia más baja del componente Baikal (c. 22%) y una falta del componente similar al Han, estando más cerca de otros grupos indoiraníes. [125] Un estudio posterior de 2022 también encontró que la expansión de las poblaciones de habla turca en Asia Central ocurrió después de la expansión de los hablantes indoeuropeos en el área. [126] Otro estudio de 2022 encontró que todas las poblaciones de habla altaica (turca, tungusica y mongólica) "eran una mezcla de ascendencia neolítica siberiana dominante y ascendencia YRB no despreciable", lo que sugiere que sus orígenes estaban en algún lugar del noreste de Asia, muy probablemente en la cuenca del río Amur . Excepto los hablantes mongoles del este y del sur, todos "poseían una alta proporción de ascendencia relacionada con Eurasia occidental, de acuerdo con el préstamo lingüístico documentado lingüísticamente en las lenguas turcas". [121]

Un estudio de 2023 analizó el ADN de la emperatriz Ashina (568-578 d. C.), una Göktürk real, cuyos restos fueron recuperados de un mausoleo en Xianyang , China . [127] Los autores determinaron que la emperatriz Ashina pertenecía al haplogrupo F1d del ADNmt del noreste de Asia , y que aproximadamente el 96-98% de su ascendencia autosómica era de origen del noreste de Asia antiguo , mientras que aproximadamente el 2-4% era de origen euroasiático occidental, lo que indica una mezcla antigua. [127] Este estudio debilitó las "hipótesis de origen euroasiático occidental y de origen múltiple". [127] Sin embargo, también señalaron que "la estepa central y el Türk medieval temprano exhibieron un alto pero variable grado de ascendencia euroasiática occidental, lo que indica que había una subestructura genética del imperio túrquico". [127] Las muestras de Türk de la Alta Edad Media se modelaron como que tenían un 37,8% de ascendencia euroasiática occidental y un 62,2% de ascendencia del noreste asiático antiguo [128] y las muestras históricas de Türk de la estepa central también eran una mezcla de ascendencia euroasiática occidental y del noreste asiático antiguo, [129] mientras que las muestras históricas Karakhanid, Kipchak y Turkic Karluk tenían un 50,6%-61,1% de ascendencia euroasiática occidental y un 38,9%-49,4% de ascendencia de agricultores del río Amarillo de la Edad del Hierro . [130] Un estudio de 2020 también encontró "alta heterogeneidad y diversidad genética durante los períodos turco y uigur" en el período medieval temprano en la estepa euroasiática oriental . [131]

Los primeros pueblos turcos separados, como los gekun (鬲昆) y los xinli (薪犁), aparecieron en las periferias de la última confederación xiongnu alrededor del año 200 a. C. [132] [133] (contemporáneamente con la dinastía Han china ) [134] y más tarde entre los tiele de habla turca [135] como hegu (紇骨) [136] y xue (薛). [75] [76]

Los tiele (también conocidos como gaoche 高車, lit. "carros altos"), [137] pueden estar relacionados con los xiongnu y los dingling . [138] Según el Libro de Wei , los tiele eran los remanentes de los chidi (赤狄), el pueblo rojo di que competía con los jin en el período de primavera y otoño . [139] Históricamente se establecieron después del siglo VI a. C. [133]

Los tiele fueron mencionados por primera vez en la literatura china entre los siglos VI y VIII. [140] Algunos eruditos (Haneda, Onogawa, Geng, etc.) propusieron que Tiele , Dili , Dingling , Chile , Tele y Tujue transliteraban la palabra subyacente Türk ; sin embargo, Golden propuso que Dili , Dingling , Chile , Tele y Tiele transliteraban Tegrek mientras que Tujue transliteraba Türküt , plural de Türk . [141] La denominación Türük ( antiguo turco : 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰) ~ Türk (OT: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰚) (de donde chino medio突厥 * dwət-kuɑt > * tɦut-kyat > chino estándar : Tūjué ) fue inicialmente reservada exclusivamente para los Göktürks por los chinos, tibetanos e incluso los uigures de habla turca . En contraste, los escritores musulmanes medievales, incluidos los hablantes de turco como el historiador otomano Mustafa Âlî y el explorador Evliya Çelebi , así como el científico timúrida Ulugh Beg , a menudo veían a las tribus del interior de Asia, "como formando una sola entidad independientemente de su afiliación lingüística" y usaban comúnmente Turk como un nombre genérico para los asiáticos interiores (ya fueran de habla turca o mongólica). Sólo en la era moderna los historiadores modernos utilizan el término "turcos" para referirse a todos los pueblos que hablan lenguas turcas , diferenciándolos de los hablantes no turcos. [142]

Según algunos investigadores (Duan, Xue, Tang, Lung, Onogawa, etc.) la posterior tribu Ashina descendió de la confederación Tiele . [143] [144] [145] [146] [147] Sin embargo, los Tiele fueron probablemente uno de los muchos grupos turcos tempranos, ancestrales de las poblaciones turcas posteriores. [148] [149] Sin embargo, según Lee y Kuang (2017), las historias chinas no describen a los Ashina y los Göktürks como descendientes de los Dingling o la confederación Tiele. [150]

Incluso se ha sugerido que los propios xiongnu, que fueron mencionados en los registros de la dinastía Han, eran hablantes de proto-turco . [151] [152] [153] [154] Los turcos pueden haber sido en última instancia de ascendencia xiongnu. [155] Aunque se sabe poco con certeza sobre la(s) lengua(s) xiongnu, parece probable que al menos una parte considerable de las tribus xiongnu hablaran una lengua turca. [156] Algunos académicos creen que probablemente eran una confederación de varios grupos étnicos y lingüísticos. [157] [158] Según un estudio de Alexander Savelyev y Choongwon Jeong, publicado en 2020 en la revista Evolutionary Human Sciences de Cambridge University Press, "es probable que la parte predominante de la población xiongnu haya hablado turco". Sin embargo, los estudios genéticos encontraron una mezcla de ascendencia euroasiática occidental y oriental, lo que sugiere una gran diversidad genética dentro de los xiongnu. El componente relacionado con el turco puede ser aportado por el sustrato genético euroasiático oriental. [159]

Utilizando los únicos escritos posiblemente xiongnu existentes, el arte rupestre de las montañas Yinshan y Helan , [160] algunos eruditos sostienen que los escritos xiongnu más antiguos son precursores del alfabeto turco más antiguo conocido , la escritura orkhon . Los petroglifos de esta región datan del noveno milenio a. C. hasta el siglo XIX, y consisten principalmente en signos grabados (petroglifos) y algunas imágenes pintadas. [161] Las excavaciones realizadas durante 1924-1925 en los kurganes de Noin-Ula ubicados en el río Selenga en las colinas del norte de Mongolia al norte de Ulaanbaatar produjeron objetos con más de 20 caracteres tallados, que eran idénticos o muy similares a las letras rúnicas de la escritura turca orkhon descubierta en el valle de Orkhon . [162]

La primera mención cierta del politónimo "turco" se encuentra en el Libro de Zhou chino . En la década del 540 d. C., este texto menciona que los turcos llegaron a la frontera de China en busca de productos de seda y una relación comercial. Un diplomático sogdiano representó a China en una serie de embajadas entre la dinastía Wei occidental y los turcos en los años 545 y 546. [164]

Según el Libro de Sui y el Tongdian , eran "bárbaros mixtos" (雜胡; záhú ) que emigraron de Pingliang (ahora en la moderna provincia de Gansu , China ) a los Rourans buscando inclusión en su confederación y protección de la dinastía prevaleciente. [165] [166] Alternativamente, según el Libro de Zhou , Historia de las dinastías del norte y Nuevo libro de Tang , el clan Ashina era un componente de la confederación Xiongnu . [167] [168] [169] [170] También se postuló que los Göktürks se originaron en un oscuro estado Suo (索國), al norte de los Xiongnu. [171] [172] La tribu Ashina eran famosos herreros y se les concedió tierra al sur de las montañas de Altai (金山Jinshan ), que parecía un casco , de donde se decía que habían obtenido su nombre 突厥 ( Tūjué ), [173] [165] el primer uso registrado de "turco" como nombre político. En el siglo VI, el poder de Ashina había aumentado tanto que conquistaron los Tiele en nombre de sus señores Rouran e incluso derrocaron a los Rouran y establecieron el Primer Kanato Turco. [174]

El nombre turco antiguo original Kök Türk deriva de kök ~ kö:k , "cielo, color cielo, azul, azul grisáceo". [175] A diferencia de su predecesor Xiongnu, el Kanato Göktürk tenía sus Kanatos temporales del clan Ashina , que estaban subordinados a una autoridad soberana controlada por un consejo de jefes tribales. El Kanato conservó elementos de su religión animista - chamánica original , que más tarde evolucionó hacia el tengriismo , aunque recibió misioneros de monjes budistas y practicó una religión sincrética. Los Göktürks fueron el primer pueblo turco en escribir en turco antiguo en una escritura rúnica, la escritura Orkhon . El Kanato también fue el primer estado conocido como "turco". Finalmente se derrumbó debido a una serie de conflictos dinásticos, pero muchos estados y pueblos utilizaron más tarde el nombre "turco". [176] [177]

Los Göktürks ( primer kaganato turco ) se extendieron rápidamente hacia el oeste hasta el mar Caspio. Entre 581 y 603, el kaganato turco occidental de Kazajstán se separó del kaganato turco oriental de Mongolia y Manchuria durante una guerra civil. Los chinos han derrocaron con éxito a los turcos orientales en 630 y crearon un protectorado militar hasta 682. Después de esa época, el segundo kaganato turco gobernó grandes partes de la antigua zona de Göktürk. Después de varias guerras entre turcos, chinos y tibetanos, el debilitado segundo kaganato turco fue reemplazado por el kaganato uigur en el año 744. [178]

Los búlgaros se establecieron entre los mares Caspio y Negro en los siglos V y VI, seguidos por sus conquistadores, los jázaros que se convirtieron al judaísmo en el siglo VIII o IX. Después de ellos vinieron los pechenegos que crearon una gran confederación, que posteriormente fue tomada por los cumanos y los kipchaks . Un grupo de búlgaros se estableció en la región del Volga y se mezcló con los finlandeses del Volga locales para convertirse en los búlgaros del Volga en lo que hoy es Tartaristán . Estos búlgaros fueron conquistados por los mongoles después de su barrido hacia el oeste bajo Ogedei Khan en el siglo XIII. [179] Otros búlgaros se establecieron en el sudeste de Europa en los siglos VII y VIII, y se mezclaron con la población eslava , adoptando lo que finalmente se convirtió en el idioma búlgaro eslavo . En todas partes, los grupos turcos se mezclaron con las poblaciones locales en diversos grados. [174]

La Bulgaria del Volga se convirtió en un estado islámico en 922 e influyó en la región, ya que controlaba muchas rutas comerciales. En el siglo XIII, los mongoles invadieron Europa y establecieron la Horda de Oro en Europa del Este, el oeste y norte de Asia Central e incluso Siberia occidental. La Confederación Cuman-Kipchak y la Bulgaria islámica del Volga fueron absorbidas por la Horda de Oro en el siglo XIII; en el siglo XIV, el Islam se convirtió en la religión oficial bajo el kan uzbeko , donde la población en general (turcos) así como la aristocracia (mongoles) comenzaron a hablar el idioma kipchak y fueron conocidos colectivamente como " tártaros " por los rusos y los occidentales. Este país también era conocido como el Kanato Kipchak y cubría la mayor parte de lo que hoy es Ucrania , así como la totalidad de la actual Rusia meridional y oriental (la sección europea). La Horda de Oro se desintegró en varios kanatos y hordas en los siglos XV y XVI, incluidos el Kanato de Crimea , el Kanato de Kazán y el Kanato de Kazajstán (entre otros), que fueron conquistados y anexados uno por uno por el Imperio ruso entre los siglos XVI y XIX. [180]

En Siberia, el Kanato siberiano fue fundado en la década de 1490 por aristócratas tártaros que huyeron de la Horda de Oro en desintegración y que establecieron el Islam como religión oficial en Siberia occidental, sobre los tártaros siberianos nativos parcialmente islamizados y los pueblos urálicos indígenas. Fue el estado islámico más septentrional de la historia registrada y sobrevivió hasta 1598, cuando fue conquistado por Rusia. [181]

El Kanato uigur se había establecido en el año 744 d. C. [182] Gracias a las relaciones comerciales establecidas con China, su capital, Ordu Baliq, en el valle de Orkhon , en el centro de Mongolia , se convirtió en un rico centro de comercio, [183] y una parte significativa de la población uigur abandonó su estilo de vida nómada para adoptar uno sedentario . El Kanato uigur produjo una extensa literatura y un número relativamente alto de sus habitantes sabían leer y escribir. [184]

La religión oficial del estado del primer Kanato Uigur era el maniqueísmo , que fue introducido a través de la conversión de Bögü Qaghan por los sogdianos después de la rebelión de An Lushan . [185] El Kanato Uigur era tolerante con la diversidad religiosa y practicaba una variedad de religiones, incluyendo el budismo, el cristianismo, el chamanismo y el maniqueísmo. [186]

Durante el mismo período, los turcos Shatuo surgieron como un factor de poder en el norte y centro de China y fueron reconocidos por el Imperio Tang como potencia aliada.

En 808, 30.000 shatuo bajo el mando de Zhuye Jinzhong desertaron de los tibetanos a la China Tang y los tibetanos los castigaron matando a Zhuye Jinzhong mientras los perseguían. [187] Los uigures también lucharon contra una alianza de shatuo y tibetanos en Beshbalik. [188]

Los turcos Shatuo bajo el mando de Zhuye Chixin ( Li Guochang ) sirvieron a la dinastía Tang en la lucha contra sus compatriotas turcos en el Kanato Uigur . En 839, cuando el general del Kanato Uigu (Huigu) Jueluowu (掘羅勿) se levantó contra el gobierno del entonces reinante Zhangxin Khan , solicitó la ayuda de Zhuye Chixin dándole 300 caballos y juntos derrotaron a Zhangxin Khan, quien luego se suicidó, precipitando el posterior colapso del Kanato Uigur. En los años siguientes, cuando los remanentes del Kanato Uigur intentaron asaltar las fronteras Tang, los Shatuo participaron ampliamente en el contraataque al Kanato Uigur con otras tribus leales a Tang. [189] En 843, Zhuye Chixin, bajo el mando del oficial chino Han Shi Xiong con tropas chinas Tuyuhun, Tangut y Han, participó en una incursión contra el khaganato uigur que condujo a la masacre de las fuerzas uigures en la montaña Shahu. [190] [191] [192]

Los turcos Shatuo habían fundado varias dinastías sinizadas de corta duración en el norte de China durante el período de las Cinco Dinastías y los Diez Reinos, comenzando con la dinastía Tang Posterior. La familia del jefe Shatuo Zhuye Chixin fue adoptada por la dinastía Tang y recibió el título de príncipe de Jin y el apellido imperial de la dinastía Tang de Li, por lo que los Shatuo de la dinastía Tang Posterior afirmaron estar restaurando la dinastía Tang y no fundando una nueva. El idioma oficial de estas dinastías era el chino y usaban títulos y nombres chinos. Algunos emperadores turcos Shatuo (de la dinastía Jin Posterior, la dinastía Han Posterior y la dinastía Han del Norte) también afirmaron tener ascendencia china Han patrilineal. [193] [194] [195]

Después de la caída de la dinastía Tang en 907, los turcos Shatuo los reemplazaron y crearon la dinastía Tang posterior en 923. Los turcos Shatuo gobernaron una gran parte del norte de China, incluida Pekín . Adoptaron nombres chinos y unieron las tradiciones turcas y chinas. La dinastía Tang posterior cayó en 937, pero los Shatuo se alzaron para convertirse en una poderosa facción del norte de China. Crearon otras dos dinastías, incluidas la dinastía Jin posterior y la dinastía Han posterior y la dinastía Han del Norte (la dinastía Han posterior y la dinastía Han del Norte fueron gobernadas por la misma familia, siendo la última un estado residual de la primera). El Shatuo Liu Zhiyuan era budista y adoraba al Buda gigante de Mengshan en 945. Las dinastías Shatuo fueron reemplazadas por la dinastía Song china Han . [196] [197] Los Shatuo se convirtieron en los turcos Ongud que vivían en Mongolia Interior después de que la dinastía Song conquistara la última dinastía Shatuo de la dinastía Han del Norte. [198] [199] Los ongud se asimilaron a los mongoles. [200] [201] [202] [199]

Los kirguises del Yeniséi se aliaron con China para destruir el Kanato uigur en el año 840 d. C. [178] [196] Desde el río Yeniséi , los kirguises avanzaron hacia el sur y el este hasta Xinjiang y el valle de Orkhon en Mongolia central, dejando gran parte de la civilización uigur en ruinas. [203] Gran parte de la población uigur se trasladó al suroeste de Mongolia, estableciendo el Reino Uigur de Ganzhou en Gansu, donde sus descendientes son los actuales Yugurs y el Reino Qocho en Turpan, Xinjiang. [204]

La Unión Kangar ( Qanghar Odaghu ) era un estado turco en el antiguo territorio del Khaganato Turco Occidental (todo el estado actual de Kazajistán , sin Zhetysu ). La capital de la Unión Kangar estaba ubicada en las montañas Ulytau. Entre los pechenegos, los kangar [nota 1] formaban la élite de las tribus pechenegas. Después de ser derrotados por los kipchaks , los turcos oghuz y los jázaros , emigraron al oeste y derrotaron a los magiares , [205] y después de formar una alianza con los búlgaros , derrotaron al ejército bizantino . [206] El estado pechenego se estableció en el siglo XI y en su apogeo tenía una población de más de 2,5 millones, compuesta por muchos grupos étnicos diferentes. [207]

Se cree que la élite de las tribus Kangar tenía un origen iraní , [208] y probablemente hablaban una lengua iraní, [209] mientras que la mayoría de la población Pecheneg hablaba una lengua turca, y un porcentaje significativo hablaba dialectos huno-búlgaros .

Los Yatuks, una tribu dentro del estado Kangar que no pudo acompañar a los Kangars cuando migraron hacia el Oeste, permanecieron en las antiguas tierras, donde se les conoce como el pueblo Kangly , que ahora es parte de las tribus uzbeka , kazaja y karakalpak . [210]

El Estado de Oguz Yabgu ( Oguz il , que significa «Tierra de Oguz», «País de Oguz») (750–1055) fue un estado túrquico , fundado por los turcos oguz en 766, ubicado geográficamente en un área entre las costas de los mares Caspio y Aral . Las tribus oguz ocupaban un vasto territorio en Kazajistán a lo largo de los ríos Irgiz , Yaik , Emba y Uil , la zona del mar de Aral, el valle del Syr Darya , las estribaciones de las montañas Karatau en Tien-Shan y el valle del río Chui (ver mapa). La asociación política oguz se desarrolló en los siglos IX y X en la cuenca del Syr Darya. [211]

Los salar descienden de turcomanos que emigraron de Asia central y se asentaron en una zona tibetana de Qinghai bajo el dominio chino Ming. La etnia salar se formó y experimentó una etnogénesis a partir de un proceso en el que los hombres turcomanos migrantes de Asia central se casaron con mujeres tibetanas amdo durante la dinastía Ming temprana. [212] [213] [214] [215]

Los pueblos turcos y grupos relacionados migraron hacia el oeste desde el noreste de China , Mongolia , Siberia y la región del Turquestán en varias oleadas hacia la meseta iraní , el sur de Asia y Anatolia (la actual Turquía). Se desconoce la fecha de la expansión inicial.

La dinastía Ghaznavid ( persa : غزنویان ġaznaviyān ) fue una dinastía musulmana persa [216] de origen mameluco turco , [217] que en su máxima extensión gobernó grandes partes de Irán , Afganistán , gran parte de Transoxiana y el subcontinente indio noroccidental (parte de Pakistán ) desde 977 hasta 1186. [218] [219] [220] La dinastía fue fundada por Sabuktigin tras su sucesión al gobierno de la región de Ghazna después de la muerte de su suegro, Alp Tigin , que era un exgeneral disidente del Imperio samánida de Balkh , al norte del Hindu Kush en el Gran Jorasán . [221]

Aunque la dinastía era de origen turco de Asia Central , estaba completamente persianizada en términos de lengua, cultura, literatura y hábitos [222] [223] [224] [225] y por eso algunos la consideran una "dinastía persa". [226]

El Imperio seléucida ( persa : آل سلجوق , romanizado : Āl-e Saljuq , lit. 'Casa de Saljuq') o el Gran Imperio seléucida [227] [228] [229] fue un imperio turco-persa [230] sunita de la Alta Edad Media , originado en la rama qiniq de los turcos oghuz . [231] En su máxima extensión, el Imperio seléucida controlaba una vasta área que se extendía desde Anatolia occidental y el Levante hasta el Hindu Kush en el este, y desde Asia Central hasta el Golfo Pérsico en el sur.

El imperio selyúcida fue fundado por Tughril Beg (1016-1063) y su hermano Chaghri Beg (989-1060) en 1037. Desde sus tierras natales cerca del mar de Aral , los selyúcidas avanzaron primero hacia Jorasán y luego hacia la Persia continental , antes de conquistar finalmente Anatolia oriental. Aquí los selyúcidas ganaron la batalla de Manzikert en 1071 y conquistaron la mayor parte de Anatolia del Imperio bizantino , lo que se convirtió en una de las razones de la primera cruzada (1095-1099). Entre 1150 y 1250 aproximadamente, el imperio selyúcida decayó y fue invadido por los mongoles alrededor de 1260. Los mongoles dividieron Anatolia en emiratos . Finalmente, uno de ellos, el otomano , conquistaría el resto. [232]

El Imperio timúrida fue un imperio turco-mongol fundado a finales del siglo XIV mediante conquistas militares lideradas por Timurlán . El establecimiento de un imperio cosmopolita fue seguido por el Renacimiento timúrida , un período de enriquecimiento local en matemáticas , astronomía , arquitectura , así como un nuevo crecimiento económico. [233] El progreso cultural del período timúrida terminó tan pronto como el imperio colapsó a principios del siglo XVI, lo que dejó a muchos intelectuales y artistas con la obligación de buscar empleo en otros lugares. [234]

El Kanato de Bujará fue un estado uzbeko [235] que existió desde 1501 hasta 1785. El Kanato fue gobernado por tres dinastías: los shaybánidas , los janíes y la dinastía uzbeka de los mangitas. En 1785, Shahmurad formalizó el gobierno dinástico de la familia ( dinastía manghit ) y el Kanato se convirtió en el Emirato de Bujará (1785-1920). [236] En 1710, el Kanato de Kokand (1710-1876) se separó del Kanato de Bujará. En 1511-1920, el Khwarazm (Khiva Khanate) fue gobernado por la dinastía Arabshahid y la dinastía uzbeka de los Kungrats. [237]

La dinastía Afsharid recibió su nombre de la tribu turca Afshar a la que pertenecían. Los Afshar habían emigrado de Turkestán a Azerbaiyán en el siglo XIII. La dinastía fue fundada en 1736 por el comandante militar Nader Shah , quien depuso al último miembro de la dinastía safávida y se autoproclamó rey de Irán . Nader pertenecía a la rama Qereqlu de los Afshar. [238] Durante el reinado de Nader, Irán alcanzó su mayor extensión desde el Imperio sasánida .

La dinastía Qajar fue creada por la tribu turca Qajar , que gobernó Irán desde 1789 hasta 1925. [239] [240] La familia Qajar tomó el control total de Irán en 1794, deponiendo a Lotf 'Ali Khan , el último Sha de la dinastía Zand , y reafirmó la soberanía iraní sobre grandes partes del Cáucaso . En 1796, Mohammad Khan Qajar se apoderó de Mashhad con facilidad, [241] poniendo fin a la dinastía Afsharid , y Mohammad Khan fue coronado formalmente como Sha después de su campaña punitiva contra los súbditos georgianos de Irán . [242] En el Cáucaso, la dinastía Qajar perdió permanentemente muchas de las áreas integrales de Irán [243] a manos de los rusos a lo largo del siglo XIX, que comprenden la actual Georgia , Daguestán , Azerbaiyán y Armenia . [244] La dinastía fue fundada por Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar y continuó hasta Ahmad Shah Qajar .

El Sultanato de Delhi es un término utilizado para cubrir cinco reinos de corta duración con sede en Delhi , dos de los cuales eran de origen turco: la dinastía mameluca (1206-90) y la dinastía Tughlaq (1320-1414). El sur de la India vio surgir la dinastía Qutb Shahi , uno de los sultanatos del Decán . El Imperio mogol fue un imperio turco-mongol que, en su mayor extensión territorial, gobernó la mayor parte del sur de Asia, incluidos Afganistán , Pakistán, India, Bangladesh y partes de Uzbekistán desde principios del siglo XVI hasta principios del XVIII. La dinastía mogol fue fundada por un príncipe turco-mongol llamado Babur (reinó entre 1526 y 1530), que descendía de Tamerlán (Tamerlán) por parte de padre y de Chagatai, segundo hijo del gobernante mongol Gengis Kan , por parte de madre. [245] [246] Otra distinción fue el intento de los mogoles de integrar a hindúes y musulmanes en un estado indio unido. [245] [247] [248] [249]

Los omeyas y abasíes árabes musulmanes lucharon contra los turcos paganos en el Kanato de Türgesh en la conquista musulmana de Transoxiana . Los soldados turcos en el ejército de los califas abasíes surgieron como gobernantes de facto de la mayor parte del Medio Oriente musulmán (aparte de Siria y Egipto ), particularmente después del siglo X. Ejemplos de estados regionales independientes de facto incluyen a los efímeros tuluníes e ikhshidíes en Egipto. Los oghuz y otras tribus capturaron y dominaron varios países bajo el liderazgo de la dinastía selyúcida y finalmente capturaron los territorios de la dinastía abasí y el Imperio bizantino . [174]

Después de muchas batallas, los turcos oghuz occidentales establecieron su propio estado y más tarde construyeron el Imperio otomano . La principal migración de los turcos oghuz ocurrió en la época medieval, cuando se extendieron por la mayor parte de Asia y hacia Europa y Oriente Medio. [174] También participaron en los enfrentamientos militares de las Cruzadas . [250] En 1090-91, los pechenegos turcos llegaron a las murallas de Constantinopla , donde el emperador Alejo I con la ayuda de los kipchaks aniquiló su ejército. [251]

A medida que el Imperio selyúcida declinaba tras la invasión mongola , el Imperio otomano emergió como el nuevo e importante estado turco, que llegó a dominar no solo el Medio Oriente, sino también el sudeste de Europa, partes del suroeste de Rusia y el norte de África. [174]

Los pueblos turcos como los karluks (principalmente del siglo VIII), los uigures , los kirguisos , los turcomanos y los kipchaks entraron más tarde en contacto con los musulmanes , y la mayoría de ellos adoptó gradualmente el islam . Algunos grupos de pueblos turcos practican otras religiones, incluida su religión animista-chamánica original, el cristianismo , el burkhanismo , el judaísmo ( jázaros , krimchaks , caraítas de Crimea ), el budismo y un pequeño número de zoroastrianos .

El Imperio Otomano se fue debilitando gradualmente ante la mala administración, las repetidas guerras con Rusia , Austria y Hungría, y el surgimiento de movimientos nacionalistas en los Balcanes , y finalmente dio paso después de la Primera Guerra Mundial a la actual República de Turquía . [174] El nacionalismo étnico también se desarrolló en el Imperio Otomano durante el siglo XIX, tomando la forma de pan-turquismo o turanismo .

Los pueblos turcos de Asia Central no estuvieron organizados en estados-nación durante la mayor parte del siglo XX, después del colapso del Imperio ruso y vivieron en la Unión Soviética o (después de una efímera Primera República del Turquestán Oriental ) en la República de China . Durante gran parte del siglo XX, Turquía fue el único país turco independiente. [252]

En 1991, tras la desintegración de la Unión Soviética , cinco estados turcos obtuvieron su independencia. Estos fueron Azerbaiyán , Kazajistán , Kirguistán , Turkmenistán y Uzbekistán . Otras regiones turcas como Tartaristán , Tuvá y Yakutia permanecieron en la Federación de Rusia . El Turquestán chino siguió siendo parte de la República Popular China . Inmediatamente después de la independencia de los estados turcos, Turquía comenzó a buscar relaciones diplomáticas con ellos. Con el tiempo, las reuniones políticas entre los países turcos aumentaron y llevaron al establecimiento de TÜRKSOY en 1993 y del Consejo Turco en 2009, que luego pasó a llamarse Organización de Estados Turcos en 2021. [253]

Según los historiadores Joo-Yup Lee y Shuntu Kuang, las historias oficiales chinas no describen a los pueblos túrquicos como pertenecientes a una única entidad uniforme llamada "turcos". [254] Sin embargo, "las historias chinas también describen a los pueblos de habla túrquica como poseedores típicos de una fisonomía del este/interior de Asia , así como ocasionalmente de una fisonomía de Eurasia occidental". [254] Según "información fragmentaria sobre el idioma xiongnu que se puede encontrar en las historias chinas, los xiongnu eran túrquicos", [255] sin embargo, los historiadores no han podido confirmar si eran o no túrquicos. La descripción de Sima Qian de sus orígenes legendarios sugiere que su fisonomía "no era demasiado diferente de la de... la población china Han (漢)", [255] pero un subconjunto de los xiongnu conocido como el pueblo Jie fue descrito como teniendo "ojos hundidos", "puentes nasales altos" y "pelo facial espeso". [255] Los Jie pueden haber sido yeniseianos , aunque otros mantienen una afiliación iraní , e independientemente de si los Xiongnu eran turcos o no, eran un pueblo híbrido. [256] Según el Antiguo Libro de Tang , Ashina Simo "no recibió un alto puesto militar por parte de los gobernantes Ashina debido a su fisonomía sogdiana ( huren胡人)". [257] El historiador Tang Yan Shigu describió al pueblo Hu de su época como descendientes de los Wusun "de ojos azules y barba roja" , [258] mientras que "no se encuentra ninguna representación comparable de los Kök Türks o Tiele en las historias oficiales chinas". [258]

El historiador Peter Golden ha informado de que las pruebas genéticas de los descendientes propuestos de la tribu Ashina parecen confirmar un vínculo con los indoiraníes , enfatizando que " los turcos en su conjunto 'estaban formados por poblaciones heterogéneas y somáticamente disímiles' ". [262] El historiador Emel Esin y el profesor Xue Zongzheng han argumentado que los rasgos de Eurasia occidental eran típicos del clan real Ashina del Khaganato turco oriental y que su apariencia cambió a una de Asia oriental debido al matrimonio mixto con la nobleza extranjera. Como resultado, en la época de Kul Tigin (684 d. C.), los miembros de la dinastía Ashina tenían rasgos de Asia oriental. [263] [264] Un estudio genético de 2023 descubrió que la emperatriz Ashina (568-578 d. C.), una Göktürk real, tenía casi en su totalidad un origen del noreste asiático antiguo , lo que debilita las "hipótesis de origen euroasiático occidental y de origen múltiple". [127] Lee y Kuang creen que es probable que "los pueblos turcos tempranos y medievales no formaran una entidad homogénea y que algunos de ellos, no turcos por origen, se hubieran turquizado en algún momento de la historia". [265] También sugieren que muchas poblaciones modernas de habla turca no descienden directamente de los pueblos turcos tempranos. [265] Lee y Kuang concluyeron que "tanto las historias chinas medievales como los estudios de ADN modernos apuntan al hecho de que los pueblos turcos tempranos y medievales estaban formados por poblaciones heterogéneas y somáticamente diferentes". [266]

Al igual que los historiadores chinos, los escritores musulmanes medievales generalmente describieron a los turcos con una apariencia de Asia oriental. [267] A diferencia de los historiadores chinos, los escritores musulmanes medievales usaron el término "turco" de manera amplia para referirse no solo a los pueblos de habla turca sino también a varios pueblos de habla no turca, [267] como los heftalitas , los rus , los magiares y los tibetanos . En el siglo XIII, Juzjani se refirió a la gente del Tíbet y las montañas entre el Tíbet y Bengala como "turcos" y "gente con rasgos turcos". [268] Las descripciones medievales árabes y persas de los turcos afirman que se veían extraños desde su perspectiva y eran extremadamente diferentes físicamente de los árabes. Los turcos fueron descritos como "gente de cara ancha y ojos pequeños", con cabello claro, a menudo rojizo, y con piel rosada, [269] como "bajos, con ojos, fosas nasales y bocas pequeñas" ( Sharaf al-Zaman al-Marwazi ), como "de cara llena y ojos pequeños" ( Al-Tabari ), como poseedores de "una cabeza grande ( sar-i buzurg ), una cara ancha ( rūy-i pahn ), ojos estrechos ( chashmhā-i tang ), y una nariz chata ( bīnī-i pakhch ), y labios y dientes desagradables ( lab va dandān na nīkū )" ( Keikavus ). [270] En las monedas turcas occidentales , "los rostros del gobernador y la institutriz son claramente mongoloides (una cara redondeada, ojos estrechos), y el retrato tiene rasgos turcos antiguos definidos (cabello largo, ausencia de tocado del gobernador, un tocado de tres picos de la institutriz)". [271]

En el palacio residencial de los Ghaznavids de Lashkari Bazar , sobrevive un retrato parcialmente conservado que representa una figura adolescente con turbante y aureola, con mejillas llenas, ojos rasgados y una boca pequeña y sinuosa. [272] El historiador armenio Movses Kaghankatvatsi describe a los turcos del Kanato túrquico occidental como "de cara ancha, sin pestañas y con cabello largo y suelto como las mujeres". [273]

Al-Masudi escribe que los turcos oghuz de Yengi-kent, cerca de la desembocadura del Syr Darya , «se distinguen de otros turcos por su valor, sus ojos rasgados y su pequeña estatura». [267] Escritores musulmanes posteriores notaron un cambio en la fisonomía de los turcos oghuz. Según Rashid al-Din Hamadani , «debido al clima, sus rasgos gradualmente cambiaron a los de los tayikos. Como no eran tayikos, los pueblos tayikos los llamaban turkmān , es decir, parecidos a los turcos ( Turk-mānand )». Ḥāfiẓ Tanīsh Mīr Muḥammad Bukhārī también relata que el «rostro turco» de los oghuz no permaneció como era después de su migración a Transoxiana e Irán . El kan de Jiva Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur escribió en su tratado en lengua chagatai Shajara-i Tarākima (Genealogía de los turcomanos) que «sus barbillas empezaron a estrecharse, sus ojos empezaron a agrandarse, sus caras empezaron a hacerse pequeñas y sus narices empezaron a hacerse grandes» después de cinco o seis generaciones. El historiador otomano Mustafa Âlî comentó en Künhüʾl-aḫbār que los turcos de Anatolia y las élites otomanas son étnicamente mixtos: «La mayoría de los habitantes de Rûm son de origen étnico confuso. Entre sus notables hay pocos cuyo linaje no se remonta a un converso al Islam». [274]

Kevin Alan Brook afirma que, como "la mayoría de los turcos nómadas, los jázaros turcos occidentales eran racial y étnicamente mixtos". [275] Istakhri describió a los jázaros como personas de pelo negro, mientras que Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi los describió como personas de ojos azules, piel clara y pelo rojizo. Istakhri menciona que había "jázaros negros" y "jázaros blancos". La mayoría de los estudiosos creen que se trataba de designaciones políticas: los negros eran de clase baja, mientras que los blancos de clase alta. Constantin Zuckerman sostiene que estos "tenían diferencias físicas y raciales y explicó que se derivaban de la fusión de los jázaros con los barsiles". [276] Las antiguas fuentes eslavas orientales llamaban a los jázaros "ugrios blancos" y a los magiares "ugrios negros". [277] Los restos jázaros excavados por los soviéticos muestran cráneos de tipo eslavo, de tipo europeo y una minoría de tipo mongoloide. [276]

Los kirguisos del Yeniséi son mencionados en el Nuevo Libro de Tang como personas que tienen la misma escritura y lengua que los uigures, pero "La gente es alta y grande y tiene pelo rojo, caras blancas y ojos verdes". [278] [nota 2] El Nuevo Libro de Tang también afirma que la vecina tribu Boma se parecía a los kirguisos, pero su lengua era diferente, lo que puede implicar que los kirguisos eran originalmente un pueblo no turco, que luego se turquizó a través de matrimonios intertribales. [278] Según Gardizi , los kirguisos se mezclaron con los "saqlabs" (eslavos), lo que explica el pelo rojo y la piel blanca entre los kirguisos, mientras que el Nuevo Libro afirma que los kirguisos "se mezclaron con los dingling". [283] [284] Los kirguisos "consideraban a los de ojos negros como descendientes de [Li] Ling", un general de la dinastía Han que desertó a los xiongnu. [285]

En un estatuto legal chino del período temprano de la dinastía Ming , se describe a los kipchaks como personas con cabello rubio y ojos azules . También se afirma que tenían una apariencia "vil" y "peculiar", y que algunos chinos no querrían casarse con ellos. [286] [287] El antropólogo ruso Oshanin (1964: 24, 32) señala que "el fenotipo 'mongoloide', característico de los kazajos y qirghiz modernos, prevalece entre los cráneos de los nómadas qipchaq y pecheneg encontrados en los kurganes en el este de Ucrania"; Lee y Kuang (2017) proponen que el descubrimiento de Oshanin se explica asumiendo que los descendientes modernos de los kipchaks históricos son kazajos de la Horda Menor , cuyos hombres poseen una alta frecuencia del subclado C2b1b1 del haplogrupo C2 (59,7 a 78%). Lee y Kuang también sugieren que la alta frecuencia (63,9%) del haplogrupo R-M73 del ADN-Y entre los Karakypshaks (una tribu dentro de los Kipchaks) permite inferir la genética de los ancestros medievales de los Karakypshaks, explicando así por qué algunos Kipchaks medievales fueron descritos como poseedores de "ojos azules [o verdes] y cabello rojo". [288]

Los historiadores bizantinos de los siglos XI y XII describen a los turcomanos como muy diferentes de los griegos. Bertrandon de la Broquière , un viajero francés al Imperio otomano , se encontró con el sultán Murad II en Adrianópolis y lo describió en los siguientes términos: "En primer lugar, como lo he visto con frecuencia, diré que es un hombre pequeño, bajo y grueso, con la fisonomía de un tártaro . Tiene una cara ancha y morena, pómulos altos, barba redonda, una nariz grande y torcida, con ojos pequeños". [289]

Existen varias organizaciones internacionales creadas con el propósito de promover la cooperación entre países con poblaciones de habla turca, como la Administración Conjunta de Artes y Cultura Turcas (TÜRKSOY), la Asamblea Parlamentaria de Países de Habla Turca (TÜRKPA) y el Consejo Turco .

La TAKM – Organización de los Organismos Euroasiáticos de Aplicación de la Ley con Estatus Militar, fue establecida el 25 de enero de 2013. Es una organización intergubernamental de aplicación de la ley militar ( gendarmería ) de actualmente tres países turcos ( Azerbaiyán , Kirguistán y Turquía ) y Kazajstán como observador.

Türksoy lleva a cabo actividades para fortalecer los lazos culturales entre los pueblos túrquicos. Uno de los principales objetivos es transmitir su patrimonio cultural común a las generaciones futuras y promoverlo en todo el mundo. [290]

Cada año, una ciudad del mundo turco es elegida “capital cultural del mundo turco”. En el marco de las actividades de conmemoración de la capital cultural del mundo turco, se celebran numerosos eventos culturales que reúnen a artistas, científicos e intelectuales, les ofrecen la oportunidad de intercambiar sus experiencias y promocionar la ciudad en cuestión a nivel internacional. [291]

La Organización de Estados Turcos , fundada el 3 de noviembre de 2009 por la confederación del Acuerdo de Najicheván , Kazajstán , Kirguistán y Turquía , tiene como objetivo integrar estas organizaciones en un marco geopolítico más estrecho.

Los países miembros son Azerbaiyán , Kazajstán , Kirguistán , Turquía y Uzbekistán . [292] La idea de crear este consejo cooperativo fue presentada por primera vez por el presidente kazajo Nursultan Nazarbayev en 2006. Hungría ha anunciado su interés en unirse a la Organización de Estados Turcos. Desde agosto de 2018, Hungría tiene estatus oficial de observador en la Organización de Estados Turcos. [293] Turkmenistán también se unió como estado observador a la organización en la octava cumbre. [294] La República Turca del Norte de Chipre fue admitida en la organización como miembro observador en la Cumbre de Samarcanda de 2022. [ 295] [296]

La distribución de las personas de origen cultural turco va desde Siberia , a través de Asia Central, hasta el sur de Europa. A partir de 2011, [update]los grupos más grandes de personas turcas viven en toda Asia Central: Kazajstán , Kirguistán , Turkmenistán , Uzbekistán y Azerbaiyán , además de Turquía e Irán . Además, los pueblos turcos se encuentran en Crimea , la región de Altishahr en el oeste de China , el norte de Irak , Israel , Rusia , Afganistán , Chipre y los Balcanes : Moldavia , Bulgaria , Rumania , Grecia y la ex Yugoslavia .

A small number of Turkic people also live in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. Small numbers inhabit eastern Poland and the south-eastern part of Finland.[297] There are also considerable populations of Turkic people (originating mostly from Turkey) in Germany, United States, and Australia, largely because of migrations during the 20th century.

Sometimes ethnographers group Turkic people into six branches: the Oghuz Turks, Kipchak, Karluk, Siberian, Chuvash, and Sakha/Yakut branches. The Oghuz have been termed Western Turks, while the remaining five, in such a classificatory scheme, are called Eastern Turks.[citation needed]

The genetic distances between the different populations of Uzbeks scattered across Uzbekistan is no greater than the distance between many of them and the Karakalpaks. This suggests that Karakalpaks and Uzbeks have very similar origins. The Karakalpaks have a somewhat greater bias towards the eastern markers than the Uzbeks.[298]

Historical population:

The following incomplete list of Turkic people shows the respective groups' core areas of settlement and their estimated sizes (in millions):

Markets in the steppe region had a limited range of foodstuffs available—mostly grains, dried fruits, spices, and tea. Turks mostly herded sheep, goats and horses. Dairy was a staple of the nomadic diet and there are many Turkic words for various dairy products such as süt (milk), yagh (butter), ayran, qaymaq (similar to clotted cream), qi̅mi̅z (fermented mare's milk) and qurut (dried yoghurt). During the Middle Ages Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Tatars, who were historically part of the Turkic nomadic group known as the Golden Horde, continued to develop new variations of dairy products.[301]

Nomadic Turks cooked their meals in a qazan, a pot similar to a cauldron; a wooden rack called a qasqan can be used to prepare certain steamed foods, like the traditional meat dumplings called manti. They also used a saj, a griddle that was traditionally placed on stones over a fire, and shish. In later times, the Persian tava was borrowed from the Persians for frying, but traditionally nomadic Turks did most of their cooking using the qazan, saj and shish. Meals were served in a bowl, called a chanaq, and eaten with a knife (bïchaq) and spoon (qashi̅q). Both bowl and spoon were historically made from wood. Other traditional utensils used in food preparation included a thin rolling pin called oqlaghu, a colander called süzgu̅çh, and a grinding stone called tāgirmān.[301]

Medieval grain dishes included preparations of whole grains, soups, porridges, breads and pastries. Fried or toasted whole grains were called qawïrmach, while köchä was crushed grain that was cooked with dairy products. Salma were broad noodles that could be served with boiled or roasted meat; cut noodles were called tutmaj in the Middle Ages and are called kesme today.[301]

There are many types of bread doughs in Turkic cuisine. Yupqa is the thinnest type of dough, bawi̅rsaq is a type of fried bread dough, and chälpäk is a deep fried flat bread. Qatlama is a fried bread that may be sprinkled with dried fruit or meat, rolled, and sliced like pinwheel sandwiches. Toqach and chöräk are varieties of bread, and böräk is a type of filled pie pastry.[301]

Herd animals were usually slaughtered during the winter months and various types of sausages were prepared to preserve the meats, including a type of sausage called sujuk. Though prohibited by Islamic dietary restrictions, historically Turkic nomads also had a variety of blood sausage. One type of sausage, called qazi̅, was made from horsemeat and another variety was filled with a mixture of ground meat, offal and rice. Chopped meat was called qïyma and spit-roasted meat was söklünch—from the root sök- meaning "to tear off", the latter dish is known as kebab in modern times. Qawirma is a typical fried meat dish, and kullama is a soup of noodles and lamb.[301]

Early Turkic mythology was dominated by Shamanism, Animism and Tengrism. The Turkic animistic traditions were mostly focused on ancestor worship, polytheistic-animism and shamanism. Later this animistic tradition would form the more organized Tengrism.[citation needed] The chief deity was Tengri, a sky god, worshipped by the upper classes of early Turkic society until Manichaeism was introduced as the official religion of the Uyghur Empire in 763.

The wolf symbolizes honour and is also considered the mother of most Turkic peoples. Ashina is the wolf mother of Tumen Il-Qağan, the first Khan of the Göktürks. The horse and predatory birds, such as the eagle or falcon, are also main figures of Turkic mythology.[citation needed]

Buddhism played an important role in the history of Turkic peoples, with the first Turkic state adopting and supporting the spread of Buddhism being the Turkic Shahis and the Göktürks. The Göktürks syncretized Buddhism with their traditional religion Tengrism and also incorporated elements of the Iranian traditional religions, such as Zoroastrianism. Buddhism had its height among the Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region.[302] Buddhism had also considerable impact and influence onto various other historical Turkic groups. In pre-Islamic times, Buddhism and Tengrism coexisted, with several Buddhist temples, monasteries, figures and steles, with images of Buddhist characters and sceneries, were constructed by various Turkic tribes. Throughout Kazakhstan, there exist various historical Buddhist sites, including an underground Buddhist cave monastery. After the Arab conquest of Central Asia, and the spread of Islam among locals, Buddhism (and Tengrism) started to lose ground, however a certain influence of the Buddhist teachings remained during the next centuries.[303]

Tengri Bögü Khan initially made the now extinct Manichaeism the state religion of the Uyghur Khaganate in 763 and it was also popular among the Karluks. It was gradually replaced by the Mahayana Buddhism.[citation needed] It existed in the Buddhist Uyghur Gaochang up to the 12th century.[304]

Tibetan Buddhism, or Vajrayana was the main religion after Manichaeism.[305] They worshipped Täŋri Täŋrisi Burxan,[306] Quanšï Im Pusar[307] and Maitri Burxan.[308] Turkic Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent and west Xinjiang attributed with a rapid and almost total disappearance of it and other religions in North India and Central Asia. The Sari Uygurs "Yellow Yughurs" of Western China, as well as the Tuvans of Russia are the only remaining Buddhist Turkic peoples.[309]

Most Turkic people today are Sunni Muslims, although a significant number in Turkey are Alevis. Alevi Turks, who were once primarily dwelling in eastern Anatolia, are today concentrated in major urban centers in western Turkey with the increased urbanism. Turkic Sunni Muslims generally follow the Hanafi rite. Azeris are traditionally Shiite Muslims. Religious observance is less strict in the Republic of Azerbaijan compared to Iranian Azerbaijan.

Islam first made contact with the Turkic peoples in 642, when Muslim armies crossed the Amu Darya after toppling the Sassanid Empire the year before. Some of the earliest rulers to convert to Islam were the Turkic princes of the city-states in the region of Sogdiana. Mass conversions did not take place until the Battle of Talas in 751, in which Turkic tribes sided with the Arabs against Chinese forces, which marked a significant milestone in the history of Islam in the region. From then onwards much of the Turkic heartland became Muslim.[310] In the 19th century, Turkic Muslim progressives in the Russian Empire spearheaded a reformist movement called Jadidism, calling for a return to basic Islamic beliefs while simultaneously accepting modernist trends.

The major Christian-Turkic peoples are the Chuvash of Chuvashia and the Gagauz (Gökoğuz) of Moldova, the vast majority of Chuvash and the Gagauz are Eastern Orthodox Christians.[311][312][313] The traditional religion of the Chuvash of Russia, while containing many ancient Turkic concepts, also shares some elements with Zoroastrianism, Khazar Judaism, and Islam. The Chuvash converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity for the most part in the second half of the 19th century.[312] As a result, festivals and rites were made to coincide with Orthodox feasts, and Christian rites replaced their traditional counterparts. A minority of the Chuvash still profess their traditional faith.[314] Between the 9th and 14th centuries, Church of the East was popular among Turks such as the Naimans.[315] It even revived in Gaochang and expanded in Xinjiang in the Yuan dynasty period.[316][317][318] It disappeared after its collapse.[319][320]

Kryashens are a sub-group of the Volga Tatars, and the vast majority are Orthodox Christians.[321] Nağaybäk are an indigenous Turkic people in Russia, most Nağaybäk are Christian and were largely converted during the 18th century.[322] Many Volga Tatars were Christianized by Ivan the Terrible during the 16th century, and continued to Christianized under subsequent Russian rulers and Orthodox clergy up to the mid-eighteenth century.[323]

Today there are several groups that support a revival of the ancient traditions. Especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union, many in Central Asia converted or openly practice animistic and shamanistic rituals. It is estimated that about 60% of Kyrgyz people practice a form of animistic rituals. In Kazakhstan there are about 54,000 followers of the ancient traditions.[324][325]

The Uyghur Turks, who once belonged to a variety of religions, were gradually Islamized during a period spanning the 10th and 13th centuries. Some scholars have linked the phenomenon of recently Islamized Uyghur soldiers recruited by the Mongol Empire to the slow conversion of Uyghur populations to Islam.[326][327]

The non-Muslim Turks' worship of Tengri and other gods was mocked and insulted by the Muslim Turk Mahmud al-Kashgari, who wrote a verse referring to them – The Infidels – May God destroy them![328][329]

The Basmil, Yabāḳu and Uyghur states were among the Turkic peoples who fought against the Kara-Khanids spread of Islam. The Islamic Kara-Khanids were made out of Tukhsi, Yaghma, Çiğil and Karluk.[330]

Kashgari claimed that the Prophet assisted in a miraculous event where 700,000 Yabāqu infidels were defeated by 40,000 Muslims led by Arslān Tegīn claiming that fires shot sparks from gates located on a green mountain towards the Yabāqu.[331] The Yabaqu were a Turkic people.[332]

Mahmud al-Kashgari insulted the Uyghur Buddhists as "Uighur dogs" and called them "Tats", which referred to the "Uighur infidels" according to the Tuxsi and Taghma, while other Turks called Persians "tat".[333][334] While Kashgari displayed a different attitude towards the Turks diviners beliefs and "national customs", he expressed towards Buddhism a hatred in his Diwan where he wrote the verse cycle on the war against Uighur Buddhists. Buddhist origin words like toyin (a cleric or priest) and Burxān or Furxan (meaning Buddha, acquiring the generic meaning of "idol" in the Turkic language of Kashgari) had negative connotations to Muslim Turks.[335][329]

Mahmud al-Kashgari in his Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk, described a game called "tepuk" among Turks in Central Asia. In the game, people try to attack each other's castle by kicking a ball made of sheep leather.[336] (see also: Cuju)

Kyz kuu (chase the girl) has been played by Turkic people at festivals since time immemorial.[337]

Horses have been essential and even sacred animals for Turks living as nomadic tribes in the Central Asian steppes. Turks were born, grew up, lived, fought and died on horseback. Jereed became the most important sporting and ceremonial game of Turkish people.[338]

The kokpar began with the nomadic Turkic peoples who have come from farther north and east spreading westward from China and Mongolia between the 10th and 15th centuries.[339]

"jigit" is used in the Caucasus and Central Asia to describe a skillful and brave equestrian, or a brave person in general.[340]

Images of Buddhist and Manichean Old Uyghurs from the Bezeklik caves and Mogao grottoes.

Approximately 200 million people,... speak nearly 40 Turkic languages and dialects. Turkey is the largest Turkic state, with about 60 million ethnic Turks living in its territories.

The greatest are the 65 million Turks of Turkey, who speak Turkish, a Turkic language...

The ancient Turkic Urheimat appears to have been located in Southern Siberia from the Lake Baikal region to Eastern Mongolia. The "Proto-Turks" in their Southern Siberian-Mongolian "homeland" were in contact with speakers of Eastern Iranian (Scytho-Sakas, who were also in Mongolia), Uralic and Paleo-Siberian languages.

All Altaic-speaking populations were a mixture of dominant Siberian Neolithic ancestry and non-negligible YRB ancestry, suggesting that Altaic-people and their language were more likely to originate from the Northeast Asia (mostly likely the ARB and surrounding regions as the primary common ancestry identified here) and further experienced influence from Neolithic YRB farmers. All Altaic people but eastern and southern Mongolic-speaking populations possessed a high proportion of West Eurasian-related ancestry, in accordance with the linguistically documented language borrowing in Turkic language.

The diversification within the Turkic languages suggests that several waves of migrations occurred35, and on the basis of the impact of local languages gradual assimilation to local populations were already assumed36. The East Asian migration starting with the Xiongnu complies well with the hypothesis that early Turkic was their major language37. Further migrations of East Asians westwards find a good linguistic correlate in the influence of Mongolian on Turkic and Iranian in the last millennium38. As such, the genomic history of the Eurasian steppe is the story of a gradual transition from Bronze Age pastoralists of western Eurasian ancestry, towards mounted warriors of increased East Asian ancestry – a process that continued well into historical times.

Modern DNA studies suggested that the Indo-Iranian group was present in Central Asia before the Turko-Mongol group11, maybe as early as Neolithic times; the Turko-Mongol group emerged later from the admixture between a group related to local Indo-Iranian and a South-Siberian or Mongolian group11,13,14 with a high East-Asian ancestry (around 60%).

By contrast, the Kyrgyz, together with other Turkic-speaking populations, originated from the admixture since the Iron Age. The Historical Era gene flow derived from the Eastern Steppe with the representative of Mongolia_Xiongnu_o1 made a more substantial contribution to Kyrgyz and other Turkic-speaking populations (i.e., Kazakh, Uyghur, Turkmen, and Uzbek; 34.9–55.2%) higher than that to the Tajik populations (11.6–18.6%; fig. 4A), suggesting Tajiks suffer fewer impacts of the recent admixtures (Martínez-Cruz et al. 2011). Consequently, the Tajik populations generally present patterns of genetic continuity of Central Asians since the Bronze Age. Our results are consistent with linguistic and genetic evidence that the spreading of Indo-European speakers into Central Asia was earlier than the expansion of Turkic speakers (Kuz′mina and Mallory 2007; Yunusbayev et al. 2015).

From the late first millennium BCE onward, a series of hierarchical and centrally organized empires arose on the Eastern Steppe, notably the Xiongnu (209 BCE–98 CE), Türkic (552–742 CE), Uyghur (744–840 CE), and Khitan (916–1125 CE) empires...Genetic data for the subsequent Early Medieval period are relatively sparse and uneven, and few Xianbei or Rouran sites have yet been identified during the 400-year gap between the Xiongnu and Türkic periods. We observed high genetic heterogeneity and diversity during the Türkic and Uyghur periods...

The Türks emerged from the Āshĭnà clan, of probable Xiōngnú descent, part of the military nobility of the Róurán.

The collapse of the Hephthalite domains made neighbours of the Türk Khāqānate and the Sasanian Empire, both sharing a border that ran the length of the River Oxus. Further Turkish expansion to the west and around the Caspian Sea saw them dominate the western steppes and its people and extend this frontier down to the Caucasus where they also shared a border with the Sasanians. Khusrow is noted at the time for improving the fortifications on either side of the Caspian, Bāb al-Abwāb at Derbent and the Great Wall of Gorgān.

Even then, the term 'Turk' was still applied in a loose sense, and we find for instance the Magyars (Majghari) or the Rus described as Turks by the same Muslim writers.70 And this is a fact which cannot be explained by assuming that these were people who were under the rule of the Turks, or, in other words, by assuming that the word is always used as a political-territorial ethnonym.71 Tibetans are also frequently confused with Turks, for instance by Al-Biruni, who speaks of 'Turks from Tibet' and 'Turks of Tibetan origin'