La guerra civil siria es un conflicto multilateral en curso en Siria en el que participan varios actores patrocinados por el Estado y no estatales . En marzo de 2011, el descontento popular con el gobierno de Bashar al-Assad desencadenó protestas a gran escala y manifestaciones a favor de la democracia en toda Siria, como parte de las protestas más amplias de la Primavera Árabe en la región. Después de meses de represión por parte del aparato de seguridad del gobierno , varios grupos rebeldes armados como el Ejército Libre Sirio comenzaron a formarse en todo el país, lo que marcó el comienzo de la insurgencia siria . A mediados de 2012, la crisis había escalado hasta convertirse en una guerra civil en toda regla.

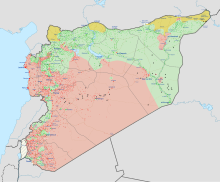

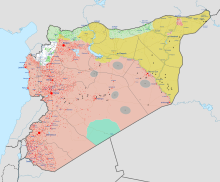

Las fuerzas rebeldes , que recibieron armas de la OTAN y de los países del CCG , inicialmente lograron avances significativos contra las fuerzas gubernamentales, que recibían armas de Irán y Rusia . Los rebeldes capturaron las capitales regionales de Raqqa en 2013 e Idlib en 2015. En consecuencia, en septiembre de 2015 Rusia lanzó una intervención militar en apoyo del gobierno, lo que cambió el equilibrio del conflicto. A fines de 2018, todos los bastiones rebeldes, excepto partes de la región de Idlib , habían caído en manos de las fuerzas gubernamentales.

En 2014, el grupo Estado Islámico tomó el control de grandes partes del este de Siria y el oeste de Irak , lo que llevó a la coalición CJTF liderada por Estados Unidos a lanzar una campaña de bombardeos aéreos en su contra, al tiempo que brindaba apoyo terrestre a las Fuerzas Democráticas Sirias de mayoría kurda . Culminando en la Batalla de Raqqa , el Estado Islámico fue derrotado territorialmente a fines de 2017. En agosto de 2016, Turquía lanzó una invasión de múltiples frentes del norte de Siria , en respuesta a la creación de Rojava , al tiempo que luchaba contra el Estado Islámico y las fuerzas gubernamentales en el proceso. Desde el alto el fuego de Idlib de marzo de 2020 , los combates en primera línea durante el conflicto han disminuido en su mayoría y se han caracterizado por escaramuzas regulares.

En marzo de 2011, el descontento popular con el gobierno baazista condujo a protestas a gran escala y manifestaciones a favor de la democracia en toda Siria, como parte de las protestas más amplias de la Primavera Árabe en la región. [15] [16] Numerosas protestas fueron violentamente reprimidas por las fuerzas de seguridad en represiones mortales ordenadas por Bashar al-Assad, que resultaron en decenas de miles de muertos y detenidos . [15] [16] La revolución siria se transformó en una insurgencia con la formación de milicias de resistencia en todo el país, deteriorándose hasta convertirse en una guerra civil en toda regla en 2012. [d]

La guerra es librada por varias facciones. Las Fuerzas Armadas Árabes Sirias , junto con sus aliados nacionales y extranjeros, representan a la República Árabe Siria y al gobierno de Asad. En su oposición se encuentra el Gobierno Provisional Sirio , una gran alianza de grupos de oposición nacionalistas y prodemocráticos (cuyas fuerzas militares consisten en el Ejército Nacional Sirio y milicias aliadas de Siria Libre ). Otra facción de oposición es el Gobierno de Salvación Sirio , cuyas fuerzas armadas están representadas por una coalición de milicias sunitas lideradas por Tahrir al-Sham . Independiente de ellos está la Administración Autónoma del Norte y el Este de Siria , cuya fuerza militar son las Fuerzas Democráticas Sirias (FDS), una fuerza multiétnica de mayoría árabe liderada por el YPG kurdo. Otras facciones en competencia incluyen organizaciones yihadistas como la rama de Al Qaeda Hurras al-Din (sucesora del Frente Al-Nusra ) y el Estado Islámico (EI).

Varios países extranjeros, como Irán , Rusia , Turquía y Estados Unidos , han estado directamente involucrados en la guerra civil , brindando apoyo a las facciones opuestas en el conflicto. Irán, Rusia y Hezbolá apoyan militarmente a la República Árabe Siria, y Rusia lleva a cabo ataques aéreos y operaciones terrestres en el país desde septiembre de 2015. Desde 2014, la coalición internacional liderada por Estados Unidos ha estado realizando operaciones aéreas y terrestres principalmente contra el Estado Islámico y ocasionalmente contra las fuerzas pro-Assad , y ha estado apoyando militar y logísticamente a facciones como el Ejército de Comando Revolucionario y las Fuerzas Democráticas Sirias (SDF) de la Administración Autónoma . Las fuerzas turcas ocupan actualmente partes del norte de Siria y, desde 2016, han luchado contra las SDF, el EI y el gobierno de Asad mientras apoyan activamente al Ejército Nacional Sirio (SNA). Entre 2011 y 2017, los combates de la guerra civil siria se extendieron al Líbano cuando opositores y partidarios del gobierno sirio viajaron al Líbano para luchar y atacarse entre sí en suelo libanés. Aunque oficialmente es neutral, Israel ha intercambiado fuego fronterizo y ha llevado a cabo repetidos ataques contra Hezbolá y las fuerzas iraníes , cuya presencia en el oeste de Siria considera una amenaza. [17] [18]

La violencia en la guerra alcanzó su punto máximo durante 2012-2017, pero la situación sigue siendo una crisis. [19] [20] Para 2020, el gobierno sirio controlaba alrededor de dos tercios del país y estaba consolidando el poder. [21] [22] Los combates en primera línea entre el gobierno de Asad y los grupos de oposición habían disminuido en su mayoría para 2023, pero había habido estallidos regulares en el noroeste de Siria y protestas a gran escala surgieron en el sur de Siria y se extendieron a todo el país en respuesta a las extensas políticas autocráticas y la situación económica. Se señaló que las protestas se parecían a la revolución de 2011 que precedió a la guerra civil. [23] [24] [25] [26] [27]

La guerra ha resultado en un estimado de 470.000 a 610.000 muertes violentas, lo que la convierte en el segundo conflicto más mortífero del siglo XXI, después de la Segunda Guerra del Congo . [28] Las organizaciones internacionales han acusado a prácticamente todas las partes involucradas (el gobierno de Asad, EI, grupos de oposición, Irán, Rusia, [29] Turquía, [30] y la coalición liderada por Estados Unidos [31]) de graves violaciones de los derechos humanos y masacres . [32] El conflicto ha causado una importante crisis de refugiados , con millones de personas huyendo a países vecinos como Turquía, Líbano y Jordania ; [33] [34] sin embargo, una minoría considerable también ha buscado refugio en países fuera del Medio Oriente, y solo Alemania ha aceptado a más de medio millón de sirios desde 2011. [34] En el transcurso de la guerra, se han lanzado varias iniciativas de paz, incluidas las conversaciones de paz de Ginebra de marzo de 2017 sobre Siria lideradas por las Naciones Unidas , pero los combates han continuado. [35]

En octubre de 2019, los líderes kurdos de Rojava , una región dentro de Siria, anunciaron que habían llegado a un importante acuerdo con el gobierno de Siria bajo el mando de Asad. Este acuerdo se promulgó a raíz de la retirada estadounidense de Siria. Los líderes kurdos hicieron este trato para obtener la ayuda de Siria para detener a las fuerzas turcas hostiles que estaban invadiendo Siria y atacando a los kurdos. [36] [37] [38]

Una importante ONG afirmó:

Doce años después de que comenzara la devastadora guerra civil siria, el conflicto parece haberse estancado. Aunque aproximadamente el 30% del país está controlado por fuerzas de oposición, los combates intensos han cesado en gran medida y hay una creciente tendencia regional hacia la normalización de las relaciones con el régimen de Bashar al-Assad. En el último decenio, el conflicto estalló y se convirtió en uno de los más complicados del mundo, con una vertiginosa variedad de poderes internacionales y regionales, grupos de oposición, agentes, milicias locales y grupos extremistas, todos ellos involucrados. La población siria ha sido brutalizada: casi medio millón de personas han muerto, 12 millones han huido de sus hogares en busca de seguridad en otro lugar y la pobreza y el hambre han sido generalizadas. Mientras tanto, los esfuerzos por negociar un acuerdo político no han dado resultado, lo que ha dejado al régimen de Assad firmemente en el poder. [39]

En 2023, la guerra civil había disminuido en gran medida y se había estancado en gran medida. Una fuente afirmó:

La guerra, cuya brutalidad en otro tiempo dominaba los titulares, ha llegado a un incómodo punto muerto. Las esperanzas de un cambio de régimen se han extinguido en gran medida, las conversaciones de paz han sido infructuosas y algunos gobiernos regionales están reconsiderando su oposición a dialogar con el líder sirio Bashar al-Assad. El gobierno ha recuperado el control de la mayor parte del país y el poder de Assad parece afianzado. [40]

En 2023, el principal conflicto militar no fue entre el gobierno sirio y los rebeldes, sino entre las fuerzas turcas y las facciones dentro de Siria. A fines de 2023, las fuerzas turcas continuaron atacando a las fuerzas kurdas en la región de Rojava. [41] A partir del 5 de octubre de 2023, las Fuerzas Armadas Turcas lanzaron una serie de ataques aéreos y terrestres contra las Fuerzas Democráticas Sirias en el noreste de Siria . Los ataques aéreos se lanzaron en respuesta al bombardeo de Ankara de 2023 , que el gobierno turco alega que fue llevado a cabo por atacantes originarios del noreste de Siria. [42]

El gobierno regional sirio del partido Baaz, no religioso , llegó al poder mediante un golpe de Estado en 1963. Durante varios años, Siria sufrió golpes de Estado y cambios de liderazgo adicionales, [43] hasta que en marzo de 1971, el general Hafez al-Assad , un alauita , se declaró presidente . Marcó el comienzo de la dominación de los cultos a la personalidad centrados en la dinastía Assad que impregnaron todos los aspectos de la vida cotidiana siria y estuvieron acompañados por una supresión sistemática de las libertades civiles y políticas, convirtiéndose en la característica central de la propaganda estatal. La autoridad en la Siria baazista está monopolizada por tres centros de poder: los clanes leales alauitas, el partido Baaz y las fuerzas armadas ; unidos por una lealtad inquebrantable hacia la dinastía Assad . [44] [45] [46]

La rama regional siria siguió siendo la autoridad política dominante en lo que había sido un estado de partido único hasta que se celebraron las primeras elecciones multipartidistas al Consejo Popular de Siria en 2012. [47] El 31 de enero de 1973, Hafez al-Assad implementó una nueva constitución, lo que llevó a una crisis nacional. La Constitución de 1973 confió al Partido Baaz Socialista Árabe el papel distintivo de "líder del estado y la sociedad", lo que le dio poder para movilizar a los civiles en favor de los programas del partido, emitir decretos para determinar su lealtad y supervisar todos los sindicatos legales. La ideología baazista se impuso a los niños como parte obligatoria del currículo escolar y las Fuerzas Armadas Sirias estaban estrechamente controladas por el Partido. La constitución eliminó el reconocimiento del Islam como religión del estado y eliminó las disposiciones existentes, como la exigencia de que el presidente de Siria fuera musulmán . Estas medidas provocaron un furor generalizado entre el público, lo que llevó a feroces manifestaciones en Hama , Homs y Alepo organizadas por la Hermandad Musulmana y los ulemas . El régimen de Assad aplastó violentamente las revueltas islámicas que ocurrieron durante 1976-1982, libradas por revolucionarios de la Hermandad Musulmana siria . [48]

El partido Baaz construyó cuidadosamente a Assad como la figura paternal que guiaría al partido y a la nación siria moderna, abogando por la continuación del gobierno dinástico de Assad en Siria. Como parte de los esfuerzos publicitarios para presentar a la nación y a la dinastía Assad como inseparables, lemas como "Assad o quemamos el país", "Assad o al diablo con el país" y "Hafez Assad, para siempre" se convirtieron en parte integral del discurso del Estado y del partido durante la década de 1980. Con el tiempo, la propia organización del partido se convirtió en un sello de goma y las estructuras de poder pasaron a depender profundamente de la afiliación sectaria a la familia Assad y del papel central de las fuerzas armadas necesarias para reprimir la disidencia en la sociedad. Los críticos del régimen han señalado que el despliegue de la violencia es el quid de la Siria baazista y la describen como "una dictadura con tendencias genocidas ". [49] Hafez gobernó Siria durante tres décadas con mano de hierro, utilizando métodos que iban desde la censura hasta medidas violentas de terrorismo de Estado como asesinatos en masa , deportaciones forzadas y prácticas brutales como la tortura , que se desataron colectivamente contra la población civil. [50] Tras la muerte de Hafez al-Assad en 2000, su hijo Bashar al-Assad lo sucedió como presidente de Siria . [49]

La esposa de Bashar , Asma , una musulmana sunita nacida y educada en Gran Bretaña, fue inicialmente aclamada en la prensa occidental como una "rosa en el desierto". [51] La pareja alguna vez generó esperanzas entre los intelectuales sirios y los observadores occidentales externos al querer implementar reformas económicas y políticas. Sin embargo, Bashar no cumplió con las reformas prometidas, y en cambio aplastó a los grupos de la sociedad civil, los reformistas políticos y los activistas democráticos que surgieron durante la primavera de Damasco en la década de 2000. [52] Bashar Al-Assad afirma que no existe una "oposición moderada" a su gobierno, y que todas las fuerzas de oposición son islamistas centrados en destruir su liderazgo secular ; su opinión era que los grupos terroristas que operan en Siria están "vinculados a las agendas de países extranjeros". [53]

La población total en julio de 2018 se estimó en 19.454.263 personas; grupos étnicos: aproximadamente árabes 50%, alauitas 15%, kurdos 10%, levantinos 10%, otros 15% (incluye drusos , ismaelitas , imami , asirios , turcomanos , armenios ); religiones: musulmanes 87% (oficiales; incluye sunitas 74% y alauitas, ismaelitas y chiítas 13%), cristianos 10% (principalmente de iglesias cristianas orientales [54] —puede ser menor como resultado de los cristianos que huyen del país), drusos 3% y judíos (pocos restantes en Damasco y Alepo). [55]

La desigualdad socioeconómica aumentó significativamente después de que Hafez al-Assad iniciara políticas de libre mercado en sus últimos años, y se aceleró después de que Bashar al-Assad llegara al poder. Con énfasis en el sector de servicios , estas políticas beneficiaron a una minoría de la población del país, en su mayoría personas que tenían conexiones con el gobierno y miembros de la clase mercantil sunita de Damasco y Alepo. [56] En 2010, el PIB nominal per cápita de Siria fue de solo $ 2.834, comparable a los países del África subsahariana como Nigeria y mucho más bajo que sus vecinos como el Líbano, con una tasa de crecimiento anual del 3,39%, por debajo de la mayoría de los demás países en desarrollo. [57]

El país también enfrentó tasas de desempleo juvenil particularmente altas. [58] Al comienzo de la guerra, el descontento contra el gobierno era más fuerte en las áreas pobres de Siria, predominantemente entre los sunitas conservadores. [56] Estas incluían ciudades con altas tasas de pobreza, como Daraa y Homs , y los distritos más pobres de las grandes ciudades.

Esto coincidió con la sequía más intensa jamás registrada en Siria, que duró de 2006 a 2011 y resultó en una pérdida generalizada de cosechas, un aumento en los precios de los alimentos y una migración masiva de familias de agricultores a los centros urbanos. [59] Esta migración tensó la infraestructura ya sobrecargada por la afluencia de alrededor de 1,5 millones de refugiados de la guerra de Irak . [60] La sequía se ha relacionado con el calentamiento global antropogénico . [61] [62] [63] Sin embargo, análisis posteriores han desafiado la narrativa de la sequía como un contribuyente importante al inicio de la guerra. [64] [65] [66] El suministro adecuado de agua sigue siendo un problema en la guerra civil en curso y con frecuencia es el objetivo de la acción militar. [67]

La situación de los derechos humanos en Siria ha sido objeto de duras críticas por parte de organizaciones internacionales durante mucho tiempo. [68] Los derechos de libre expresión , asociación y reunión estaban estrictamente controlados en Siria incluso antes del levantamiento. [69] El país estuvo bajo un régimen de emergencia desde 1963 hasta 2011 y las reuniones públicas de más de cinco personas estaban prohibidas. [70] Las fuerzas de seguridad tenían amplios poderes de arresto y detención. [71] A pesar de las esperanzas de cambio democrático con la Primavera de Damasco de 2000 , se informó ampliamente que Bashar al-Assad no había implementado ninguna mejora. En 2010, impuso una controvertida prohibición nacional de los códigos de vestimenta islámicos femeninos (como los velos faciales ) en las universidades, donde, según se informa, más de mil maestros de escuela primaria que usaban el niqab fueron reasignados a trabajos administrativos. [72] Un informe de Human Rights Watch publicado justo antes del comienzo del levantamiento de 2011 afirmó que Assad no había mejorado sustancialmente el estado de los derechos humanos desde que tomó el poder. [73]

Estados Unidos y sus aliados pretendían construir el gasoducto Qatar-Turquía que aliviaría a Europa de su dependencia del gas natural ruso, especialmente durante los meses de invierno, cuando muchos hogares europeos dependen de Rusia para sobrevivir al invierno. Por el contrario, Rusia y sus aliados pretendían detener este gasoducto planeado y en su lugar construir el gasoducto Irán-Irak-Siria . [74] [75] El presidente sirio Bashar al-Assad rechazó la propuesta de Qatar del año 2000 de construir un gasoducto Qatar-Turquía de 10 mil millones de dólares a través de Arabia Saudita, Jordania, Siria y Turquía, lo que supuestamente provocó operaciones encubiertas de la CIA para provocar una guerra civil siria para presionar a Bashar al-Assad para que dimitiera y permitiera que un presidente pro-estadounidense interviniera y firmara el acuerdo. Documentos filtrados han demostrado que en 2009, la CIA comenzó a financiar y apoyar a grupos de oposición en Siria para fomentar una guerra civil. [76] [75]

El profesor de Harvard Mitchell A. Orenstein y George Romer afirmaron que esta disputa por el oleoducto es la verdadera motivación detrás de que Rusia entrara en la guerra en apoyo de Bashar al-Assad, apoyando su rechazo del oleoducto Qatar-Turquía y esperando allanar el camino para el oleoducto Irán-Irak-Siria que reforzaría a los aliados de Rusia y estimularía la economía de Irán. [77] [78] El ejército estadounidense ha establecido bases cerca de gasoductos en Siria, supuestamente para luchar contra ISIS, pero quizás también para defender sus propios activos de gas natural, que supuestamente han sido atacados por milicias iraníes. [79] Los campos de gas de Conoco han sido un punto de discordia para Estados Unidos desde que cayeron en manos de ISIS, que fueron capturados por las Fuerzas Democráticas Sirias respaldadas por Estados Unidos en 2017. [80]

Protestas, levantamientos civiles y deserciones (marzo-julio de 2011)

Insurgencia armada inicial (julio de 2011 – abril de 2012)

Intento de alto el fuego de Kofi Annan (abril-mayo de 2012)

Comienza la siguiente fase de la guerra: la escalada (2012-2013)

El auge de los grupos islamistas (enero-septiembre de 2014)

Intervención de EE.UU. (septiembre de 2014 – septiembre de 2015)

Intervención rusa (septiembre de 2015 – marzo de 2016), incluido el primer alto el fuego parcial

Alepo recuperada; alto el fuego respaldado por Rusia, Irán y Turquía (diciembre de 2016 – abril de 2017)

Conflicto sirio-estadounidense; zonas de distensión (abril-junio de 2017)

Roto el asedio del EI a Deir ez-Zor; se detiene el programa de la CIA; las fuerzas rusas permanecen (julio-diciembre de 2017)

Avance del ejército en la provincia de Hama y Ghouta; intervención turca en Afrín (enero-marzo de 2018)

Ataque químico en Duma; ataques con misiles liderados por Estados Unidos; ofensiva en el sur de Siria (abril-agosto de 2018)

Desmilitarización de Idlib; Trump anuncia la retirada de Estados Unidos; Irak ataca objetivos del EI (septiembre-diciembre de 2018)

Continúan los ataques del EI; EE.UU. establece las condiciones de la retirada; quinto conflicto entre rebeldes (enero-mayo de 2019)

Fracasa el acuerdo de desmilitarización; se lanza una ofensiva en el noroeste de Siria en 2019; se establece una zona de amortiguación en el norte de Siria (mayo-octubre de 2019)

Las fuerzas estadounidenses se retiran de la zona de contención; Turquía lanza una ofensiva en el noreste de Siria (octubre de 2019)

Ofensiva en el noroeste; ataques aéreos en Baylun; Operación Escudo de Primavera; enfrentamientos en Daraa; bombardeos en Afrin (finales de 2019; 2020)

Nueva crisis económica y estancamiento del conflicto (junio de 2020-actualidad)

Hay numerosas facciones, tanto extranjeras como nacionales, involucradas en la guerra civil siria. Estas pueden dividirse en cuatro grupos principales. Primero, la Siria baazista liderada por Bashar al-Assad y respaldada por sus aliados rusos e iraníes . Segundo, la oposición siria que consiste en dos gobiernos alternativos: i) el Gobierno interino sirio , una gran coalición de grupos políticos democráticos , nacionalistas sirios e islámicos cuyas fuerzas de defensa consisten en el Ejército Nacional Sirio [81] y el Ejército Libre Sirio , y ii) el Gobierno de Salvación Sirio , una coalición islamista sunita liderada por Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham . [82] Tercero, la Administración Autónoma del Norte y Este de Siria dominada por los kurdos y su ala militar Fuerzas Democráticas Sirias apoyadas por Estados Unidos , Francia y otros aliados de la coalición . [83] Cuarto, el campo yihadista global que consiste en la organización afiliada a al-Qaeda Guardianes de la Religión y su rival Estado Islámico de Irak y el Levante . [84] El gobierno sirio, la oposición y las SDF han recibido apoyo —militar, logístico y diplomático— de países extranjeros, lo que ha llevado a que el conflicto sea descrito a menudo como una guerra por poderes . [85]

Los principales partidos que apoyan al gobierno sirio son Irán , [86] Rusia [87] y la milicia libanesa Hezbolá . Los grupos rebeldes sirios recibieron apoyo político, logístico y militar de los Estados Unidos , [88] [89] Turquía , [90] Arabia Saudita , [91] Qatar , [92] Gran Bretaña, Francia, [93] Israel , [94] [95] y los Países Bajos . [96] Bajo la égida de la operación Timber Sycamore y otras actividades clandestinas, los agentes de la CIA y las tropas de operaciones especiales estadounidenses han entrenado y armado a casi 10.000 combatientes rebeldes a un costo de 1.000 millones de dólares al año desde 2012. [97] [98] Irak también había estado involucrado en el apoyo al gobierno sirio, pero principalmente contra el EIIL . [99]

Hezbolá , el grupo militante chiita libanés, estuvo significativamente involucrado en la Guerra Civil Siria. A partir de la revolución siria de 2011 , Hezbolá brindó apoyo activo a las fuerzas gubernamentales baasistas. [100] [101] Para 2012, el grupo intensificó su participación, desplegando tropas en toda Siria. [102] En 2013, Hezbolá reconoció públicamente su presencia en Siria, intensificando su compromiso terrestre. Esta participación incluyó un estimado de 5.000 a 8.000 combatientes en un momento dado, que comprendían Fuerzas Especiales , fuerzas permanentes de todas las unidades, combatientes a tiempo parcial y nuevos reclutas con entrenamiento de combate acelerado. La presencia de Hezbolá, apoyada por armamento y entrenamiento iraníes, complicó aún más la dinámica del conflicto, provocando ataques aéreos israelíes contra Hezbolá y objetivos iraníes en Siria. [103]

En junio de 2014, miembros del Estado Islámico de Irak y el Levante (EIIL) cruzaron la frontera desde Siria hacia el norte de Irak y tomaron el control de grandes franjas de territorio iraquí mientras el ejército iraquí abandonaba sus posiciones. Los combates entre rebeldes y fuerzas gubernamentales también se extendieron al Líbano en varias ocasiones. Hubo repetidos incidentes de violencia sectaria en la Gobernación del Norte del Líbano entre partidarios y opositores del gobierno sirio, así como enfrentamientos armados entre sunitas y alauitas en Trípoli . [104]

El 5 de junio de 2014, el EIIL se apoderó de amplias zonas de territorio iraquí. A partir de ese año, la Fuerza Aérea Árabe Siria realizó ataques aéreos contra el EIIL en Raqqa y Al-Hasakah en coordinación con el gobierno iraquí. [105]

_12.jpg/440px-International_Mine_Action_Center_in_Syria_(Aleppo)_12.jpg)

Durante el conflicto se han utilizado gas sarín , gas mostaza y gas cloro . Numerosas víctimas provocaron una reacción internacional, especialmente el ataque químico de Ghouta en 2013. Se solicitó una misión de investigación de las Naciones Unidas para investigar los ataques con armas químicas denunciados . En cuatro casos, los inspectores de las Naciones Unidas confirmaron el uso de gas sarín . [106] En agosto de 2016, un informe confidencial de las Naciones Unidas y la OPAQ culpó explícitamente al ejército sirio de Bashar al-Assad por lanzar armas químicas (bombas de cloro) sobre las ciudades de Talmenes en abril de 2014 y Sarmin en marzo de 2015 y al ISIS por usar gas mostaza de azufre en la ciudad de Marea en agosto de 2015. [107]

Estados Unidos y la Unión Europea han dicho que el gobierno sirio ha llevado a cabo varios ataques químicos. Tras los ataques de Ghouta en 2013 y la presión internacional, comenzó la destrucción de las armas químicas de Siria . En 2015, la misión de la ONU reveló rastros previamente no declarados de compuestos de sarín en un "sitio de investigación militar". [108] Después del ataque químico de Khan Shaykhun en abril de 2017 , Estados Unidos lanzó su primer ataque intencional contra las fuerzas del gobierno sirio. La investigación realizada por Tobias Schneider y Theresa Lutkefend del instituto de investigación GPPi documentó 336 ataques confirmados con armas químicas en Siria entre el 23 de diciembre de 2012 y el 18 de enero de 2019. El estudio atribuyó el 98% del total de ataques químicos al régimen de Assad. Casi el 90% de los ataques ocurrieron después del ataque químico de Ghouta en agosto de 2013. [109] [110]

En abril de 2020, el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU celebró una sesión informativa sobre las conclusiones de un organismo de control mundial de armas químicas, la Organización para la Prohibición de las Armas Químicas (OPAQ), que descubrió que la Fuerza Aérea Siria utilizó gas sarín y cloro en múltiples ataques en 2017. Los aliados cercanos de Siria, Rusia y los países europeos debatieron sobre el tema, donde las conclusiones de la OPAQ fueron desestimadas por Moscú, mientras que muchos países de Europa occidental pidieron rendición de cuentas por los crímenes de guerra del gobierno . [111] El embajador adjunto de Gran Bretaña ante la ONU, Jonathan Allen, declaró que el informe del Equipo de Investigación e Identificación (IIT) de la OPAQ afirmaba que el régimen sirio es responsable del uso de armas químicas en la guerra en al menos cuatro ocasiones. La información también se señaló en dos investigaciones ordenadas por la ONU. [112]

En abril de 2021, Siria fue suspendida de la OPAQ mediante votación pública de los estados miembros, por no cooperar con el IIT y violar la Convención sobre Armas Químicas . [113] [114] [115] Las conclusiones de otro informe de investigación de la OPAQ publicado en julio de 2021 concluyeron que el régimen sirio había participado en ataques químicos confirmados al menos 17 veces, de los 77 incidentes denunciados de uso de armas químicas atribuidos a las fuerzas asadistas . [116] [117]

Siria no es parte de la Convención sobre Municiones en Racimo y no reconoce la prohibición del uso de bombas de racimo . Se informa que el ejército sirio comenzó a utilizar bombas de racimo en septiembre de 2012. Steve Goose, director de la División de Armas de Human Rights Watch, dijo que "Siria está ampliando su uso incesante de municiones de racimo, un arma prohibida, y los civiles están pagando el precio con sus vidas y sus extremidades". "El costo inicial es sólo el comienzo porque las municiones de racimo a menudo dejan bombas pequeñas sin explotar que matan y mutilan mucho después". [118]

Las armas termobáricas rusas , también conocidas como "bombas de aire y combustible", fueron utilizadas por el lado gubernamental durante la guerra. El 2 de diciembre de 2015, The National Interest informó que Rusia estaba desplegando el sistema de lanzamiento de cohetes múltiples TOS-1 Buratino en Siria, que está "diseñado para lanzar cargas termobáricas masivas contra la infantería en espacios confinados como las áreas urbanas". [119] Un lanzacohetes termobárico Buratino "puede arrasar un área de aproximadamente 200 por 400 metros (660 por 1.310 pies) con una sola salva". [120] Desde 2012, los rebeldes han dicho que la Fuerza Aérea Siria (fuerzas gubernamentales) está utilizando armas termobáricas contra áreas residenciales ocupadas por los combatientes rebeldes, como durante la Batalla de Alepo y también en Kafr Batna . [121] Un panel de investigadores de derechos humanos de las Naciones Unidas informó que el gobierno sirio utilizó bombas termobáricas contra la ciudad estratégica de Qusayr en marzo de 2013. [122] En agosto de 2013, la BBC informó sobre el uso de bombas incendiarias similares al napalm en una escuela en el norte de Siria. [123]

En Siria se utilizan varios tipos de misiles antitanque . Rusia ha enviado misiles antitanque guiados de tercera generación 9M133 Kornet al gobierno sirio, cuyas fuerzas los han utilizado ampliamente contra blindados y otros objetivos terrestres para combatir a los yihadistas y rebeldes. [124] Los misiles BGM-71 TOW de fabricación estadounidense son una de las principales armas de los grupos rebeldes y han sido proporcionados principalmente por Estados Unidos y Arabia Saudita. [125] Estados Unidos también ha suministrado muchos lanzadores y ojivas 9K111 Fagot de origen europeo del este a grupos rebeldes sirios en el marco de su programa Timber Sycamore . [126]

En junio de 2017, Irán atacó objetivos del EI en la zona de Deir ez-Zor , en el este de Siria, con misiles balísticos Zolfaghar disparados desde el oeste de Irán, [127] en el primer uso de misiles de mediano alcance por parte de Irán en 30 años. [128] Según Jane's Defence Weekly , los misiles viajaron entre 650 y 700 kilómetros. [127]

En 2022, un tribunal alemán condenó a cadena perpetua a Anwar Raslan , de 58 años, un alto funcionario del régimen del presidente Bashar al-Assad, después de que solicitara asilo en Alemania y fuera arrestado en 2019. Fue acusado de ser cómplice del asesinato de al menos 27 personas, junto con la agresión sexual y la tortura de al menos otras 4.000 personas entre el 29 de abril de 2011 y el 7 de septiembre de 2012. Raslan era un oficial de nivel medio en la Sección 251 y supervisó la tortura de detenidos. Su juicio fue de una naturaleza sin precedentes porque Alemania asumió un juicio por crímenes cometidos en la guerra de Siria y los abogados de derechos humanos lo asumieron bajo el principio de "jurisdicción universal". La jurisdicción universal es un concepto en la ley alemana que permite que los delitos graves sean juzgados en Alemania incluso si no ocurrieron en el país. Su coacusado, Eyad al-Gharib, de 44 años, un oficial de bajo rango de la Sección 251, también fue condenado a 4 años y 6 meses de prisión el 24 de febrero de 2021. Las funciones de Eyad incluían el transporte de detenidos a lugares donde serían torturados durante días seguidos. Fue su conocimiento del hecho de que allí se estaban produciendo torturas lo que le valió la condena. [129] [130]

Los sucesivos gobiernos de Hafez y Bashar al-Assad han estado estrechamente asociados con el grupo religioso minoritario alauita del país [131], una rama de los chiítas, mientras que la mayoría de la población, y la mayor parte de la oposición, es sunita . Esto dio lugar a llamamientos a la persecución de los alauitas por parte de sectores de la oposición. [132]

Un tercio de los 250.000 hombres alauitas en edad militar han muerto combatiendo en la guerra civil siria. [133] En mayo de 2013, el SOHR afirmó que de los 94.000 muertos durante la guerra, al menos 41.000 eran alauitas. [134]

Según el sitio web de noticias The Daily Beast , muchos cristianos sirios declararon en noviembre de 2013 que habían huido después de haber sido atacados por los rebeldes antigubernamentales. [135]

A medida que las milicias y los chiítas no sirios, motivados por un sentimiento pro chií más que por la lealtad al gobierno de Asad, han asumido la lucha contra las fuerzas antigubernamentales que estaban en manos del debilitado ejército sirio, la lucha ha adquirido un carácter más sectario. Un líder de la oposición ha dicho que las milicias chiítas a menudo "intentan ocupar y controlar los símbolos religiosos de la comunidad sunita para lograr no sólo una victoria territorial sino también sectaria" [136], ocupando supuestamente mezquitas y reemplazando iconos sunitas por imágenes de líderes chiítas. [136] Según la Red Siria de Derechos Humanos, las milicias han cometido abusos contra los derechos humanos, incluida "una serie de masacres sectarias entre marzo de 2011 y enero de 2014 que dejaron 962 civiles muertos". [136]

La Administración Autónoma del Norte y el Este de Siria (AANES), también conocida como Rojava, [e] es una región autónoma de facto en el noreste de Siria. [140] [141] La región no pretende buscar la independencia total, sino la autonomía dentro de una Siria federal y democrática. [142] Rojava consta de subregiones autónomas en las áreas de Afrín , Jazira , Éufrates , Raqqa , Tabqa , Manbij y Deir Ez-Zor . [143] [144] La región obtuvo su autonomía de facto en 2012 en el contexto del actual conflicto de Rojava , en el que ha participado su fuerza militar oficial, las Fuerzas Democráticas Sirias (SDF). [145] [146]

Si bien mantiene algunas relaciones exteriores , la región no está oficialmente reconocida como autónoma por el gobierno de Siria ni por ningún estado, excepto por el Parlamento catalán . [147] [148] La AANES tiene un amplio apoyo a sus políticas universales democráticas , sostenibles , autónomas , pluralistas , igualitarias y feministas en los diálogos con otros partidos y organizaciones. [149] [150] [151] [152] El noreste de Siria es poliétnico y alberga importantes poblaciones étnicas kurdas , árabes y asirias , con comunidades más pequeñas de etnias turcomanas , armenias , circasianas y yazidíes . [153] [154] [155]

Los partidarios de la administración de la región afirman que se trata de una entidad política oficialmente secular [156] [157] con ambiciones democráticas directas basadas en una ideología socialista anarquista , feminista y libertaria que promueve la descentralización , la igualdad de género , [158] [159] la sostenibilidad medioambiental , la ecología social y la tolerancia pluralista hacia la diversidad religiosa, cultural y política , y que estos valores se reflejan en su constitución , sociedad y política, afirmando que es un modelo para una Siria federalizada en su conjunto, en lugar de una independencia absoluta. [142] [160] [161] [162] [163] La administración de la región también ha sido acusada por algunas fuentes partidistas y no partidistas de autoritarismo , apoyo al gobierno sirio, [164] kurdificación y desplazamiento. [165] Sin embargo, a pesar de esto, la AANES ha sido el sistema más democrático en Siria, con elecciones directas abiertas, igualdad universal , respeto a los derechos humanos dentro de la región, así como defensa de los derechos de las minorías y religiosos dentro de Siria. [149] [166] [167] [168] [169] [170] [171]

En marzo de 2015, el Ministro de Información sirio anunció que su gobierno estaba considerando reconocer la autonomía kurda "dentro de la ley y la constitución". [172] Si bien la administración de la región no fue invitada a las conversaciones de paz de Ginebra III sobre Siria , [173] ni a ninguna de las conversaciones anteriores, Rusia en particular pidió la inclusión de la región y hasta cierto punto llevó las posiciones de la región a las conversaciones, como se documenta en el borrador de Rusia de mayo de 2016 para una nueva constitución para Siria. [174] [175]

Un análisis publicado en junio de 2017 describió la “relación de la región con el gobierno como tensa pero funcional” y una “dinámica semi-cooperativa”. [176] A fines de septiembre de 2017, el Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores de Siria dijo que Damasco consideraría otorgar a los kurdos más autonomía en la región una vez que el EIIL fuera derrotado. [177]

El 13 de octubre de 2019, las SDF anunciaron que habían llegado a un acuerdo con el ejército sirio que permitía a este último entrar en las ciudades de Manbij y Kobani bajo su control para disuadir un ataque turco contra esas ciudades como parte de la ofensiva transfronteriza de los rebeldes turcos y sirios apoyados por Turquía. [178] El ejército sirio también se desplegó en el norte de Siria junto con las SDF a lo largo de la frontera sirio-turca y entró en varias ciudades bajo su control, como Ayn Issa y Tell Tamer. [179] [180] Tras la creación de la Segunda Zona de Amortiguación del Norte de Siria, las SDF declararon que estaban dispuestas a trabajar en cooperación con el ejército sirio si se lograba un acuerdo político entre el gobierno sirio y las SDF. [181]

Según información recopilada en diciembre de 2021, las autoridades iraquíes han repatriado a 100 combatientes iraquíes del grupo EIIL (ISIS) que estaban detenidos por las fuerzas kurdas en el noreste de Siria. [182]

A partir de 2022, la principal amenaza militar y el conflicto que enfrenta la fuerza de defensa oficial de Rojava, las Fuerzas Democráticas Sirias (FDS), son, en primer lugar, un conflicto en curso con ISIS; y en segundo lugar, las preocupaciones actuales sobre una posible invasión de las regiones del noreste de Siria por parte de las fuerzas turcas, con el fin de atacar a los grupos kurdos en general, y a Rojava en particular. [183] [184] [185] Un informe oficial del gobierno de Rojava señaló a las milicias respaldadas por Turquía como la principal amenaza para la región de Rojava y su gobierno. [186]

En mayo de 2022, funcionarios turcos y de la oposición siria dijeron que las Fuerzas Armadas de Turquía y el Ejército Nacional Sirio están planeando una nueva operación contra las SDF, compuestas principalmente por las YPG/YPJ. [187] [188] La nueva operación está programada para reanudar los esfuerzos para crear "zonas seguras" de 30 kilómetros de ancho (19 millas) a lo largo de la frontera de Turquía con Siria, dijo el presidente Erdoğan en un comunicado. [189] La operación tiene como objetivo las regiones de Tal Rifaat y Manbij al oeste del Éufrates y otras áreas más al este. Mientras tanto, Ankara está en conversaciones con Moscú sobre la operación. El presidente Erdoğan reiteró su determinación para la operación el 8 de agosto de 2022. [190]

El 5 de junio de 2022, el líder de las Fuerzas Democráticas Sirias (FDS), Mazloum Abdi, dijo que las fuerzas del gobierno kurdo en la Administración Autónoma del Norte y el Este de Siria (AANES) estaban dispuestas a trabajar con las fuerzas del gobierno sirio para defenderse de Turquía, diciendo que "Damasco debería usar sus sistemas de defensa aérea contra los aviones turcos". Abdi dijo que los grupos kurdos podrían cooperar con el gobierno sirio y aún así conservar su autonomía. [191] [192] [193] [194] [195] Las discusiones conjuntas fueron el resultado de los procesos de negociación que habían comenzado en octubre de 2019. [196] A principios de 2023, los informes indicaron que las fuerzas del Estado Islámico en Siria habían sido derrotadas en su mayoría, y que solo quedaban unas pocas células en varios lugares remotos. [197] [198] [199]

En 2023, Turquía siguió apoyando a varias milicias en Siria, principalmente el Ejército Nacional Sirio , que periódicamente intentó algunas operaciones contra grupos kurdos. [187] [188] [200] Un objetivo declarado era crear "zonas seguras" a lo largo de la frontera de Turquía con Siria, según una declaración del presidente turco Erdoğan. [189] Las operaciones estaban dirigidas generalmente a las regiones de Tal Rifaat y Manbij al oeste del Éufrates y otras áreas más al este. El presidente Erdoğan declaró abiertamente su apoyo a las operaciones, en conversaciones con Moscú a mediados de 2022. [190]

En 2015 [update], 3,8 millones de personas se habían convertido en refugiados. [201] En 2013 [update], uno de cada tres refugiados sirios (unas 667.000 personas) buscó seguridad en el Líbano (normalmente una población de 4,8 millones). [202] Otros han huido a Jordania, Turquía e Irak. Turquía ha aceptado a 1,7 millones (2015) de refugiados sirios, la mitad de los cuales están repartidos por ciudades y una docena de campamentos colocados bajo la autoridad directa del Gobierno turco. Las imágenes por satélite confirmaron que los primeros campamentos sirios aparecieron en Turquía en julio de 2011, poco después de que las ciudades de Deraa, Homs y Hama fueran sitiadas. [203] En septiembre de 2014, la ONU declaró que el número de refugiados sirios había superado los tres millones. [204] Según el Centro de Asuntos Públicos de Jerusalén , los sunitas se están marchando al Líbano y están socavando el estatus de Hezbolá. La crisis de refugiados sirios ha hecho que la amenaza de "Jordania es Palestina" disminuya debido a la avalancha de nuevos refugiados en Jordania. El patriarca católico griego Gregorios III Laham dice que más de 450.000 cristianos sirios han sido desplazados por el conflicto. [205] A septiembre de 2016 [update], la Unión Europea ha informado de que hay 13,5 millones de refugiados que necesitan asistencia en el país. [206] Se está haciendo un llamamiento a Australia para que rescate a más de 60 mujeres y niños atrapados en el campamento de Al-Hawl, en Siria, ante una posible invasión turca. [207]

Una importante declaración de la ONG ACT Alliance concluyó que millones de refugiados sirios siguen desplazados en países de Siria. Esto incluye alrededor de 1,5 millones de refugiados en el Líbano. El informe también concluyó que el número de refugiados en los campamentos del noreste de Siria se ha triplicado este año. [208]

Numerosos refugiados permanecen en campamentos de refugiados locales, donde se informa de que las condiciones son duras, especialmente ahora que se acerca el invierno. [209] [210]

En el campamento de Washokani se encuentran alojadas 4.000 personas. Ninguna organización las ayuda, salvo la Cruz Roja kurda. Numerosos residentes del campamento han pedido ayuda a grupos internacionales. [211] [212]

Los refugiados en el noreste de Siria informan que no han recibido ayuda de las organizaciones de ayuda internacional. [213]

El 30 de diciembre de 2019, más de 50 refugiados sirios, incluidos 27 niños, fueron recibidos en Irlanda, donde comenzaron una nueva vida en sus nuevos hogares temporales en el Centro de Alojamiento Mosney en el condado de Meath. Los refugiados migrantes fueron entrevistados previamente por funcionarios irlandeses en el marco del Programa Irlandés de Protección de Refugiados (IRPP). [214]

En 2022, hay más de 5,6 millones de refugiados, de los cuales más de 3,7 millones (alrededor del 65%) se encuentran en Turquía. [215] Estas cifras han hecho que se atribuya mucha culpa a los refugiados de todo el espectro político del país, a quienes se les culpa del empeoramiento de la crisis económica. Se han puesto en marcha medidas para "expulsarlos", incluido el aumento de las tarifas de los servicios públicos, como el agua, y de servicios como las licencias de matrimonio. Se ha producido un aumento de los ataques contra los refugiados sirios en el país. [216]

Otro aspecto de los años de posguerra será cómo repatriar a los millones de refugiados. El gobierno sirio ha presentado una ley conocida comúnmente como "ley 10", que podría despojar a los refugiados de sus propiedades, como los inmuebles dañados. Algunos refugiados también temen que si regresan a reclamar sus propiedades se enfrentarán a consecuencias negativas, como el reclutamiento forzoso o la prisión. El gobierno sirio ha sido criticado por utilizar esta ley para recompensar a quienes han apoyado al gobierno. Sin embargo, el gobierno dijo que esta declaración era falsa y expresó que desea el regreso de los refugiados del Líbano. [217] [218] En diciembre de 2018, también se informó de que el gobierno sirio había comenzado a confiscar propiedades en virtud de una ley antiterrorista, lo que está afectando negativamente a los opositores al gobierno, y muchos han perdido sus propiedades. También se han cancelado las pensiones de algunas personas. [219]

Erdogan dijo que Turquía espera reasentar a alrededor de 1 millón de refugiados en la "zona de amortiguación" que controla. [220] [221] [222] [223] Erdogan afirmó que Turquía había gastado miles de millones en aproximadamente cinco millones de refugiados que ahora están alojados en Turquía; y pidió más financiación de las naciones más ricas y de la UE. [224] [225] [226] [227] [228] [229] Este plan generó preocupación entre los kurdos sobre el desplazamiento de las comunidades y grupos existentes en esa área.

La violencia en Siria ha obligado a millones de personas a huir de sus hogares. Según estimaciones de Al-Jazeera, en marzo de 2015, 10,9 millones de sirios, es decir, casi la mitad de la población, han sido desplazados. [201] La violencia que estalló debido a la crisis en curso en el noroeste de Siria ha obligado a 6.500 niños a huir cada día durante la última semana de enero de 2020. El recuento registrado de niños desplazados en la zona ha llegado a más de 300.000 desde diciembre de 2019. [230]

En 2022, hay 6,2 millones de desplazados internos en Siria según el Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Refugiados . De ellos, 2,5 millones son niños. Solo en 2017 se produjo el desplazamiento de al menos 1,8 millones de personas, muchas de ellas desplazadas por segunda y tercera vez. [231]

Cientos de niños están retenidos como rehenes por el ISIS. El 25 de enero de 2022, The New York Times afirmó que la lucha por una prisión en el noreste de Siria ha llamado la atención sobre la difícil situación de miles de niños extranjeros que fueron traídos a Siria por sus padres para unirse al califato del Estado Islámico y han estado detenidos durante tres años en campamentos y prisiones de la región, abandonados por sus países de origen. [232]

Se estima que unos 40.000 extranjeros, incluidos niños, viajaron a Siria para luchar por el califato o trabajar para él. Miles de ellos habían traído consigo a sus hijos pequeños. También había otros niños nacidos allí. Cuando el ISIS perdió el control del último trozo de territorio en Siria, Baghuz, hace tres años, las mujeres y los niños pequeños supervivientes fueron detenidos en campos, mientras que los presuntos militantes y los niños, algunos de tan sólo 10 años, fueron encarcelados. [232]

Además, cuando los muchachos de los campos llegan a la adolescencia, suelen ser trasladados a la prisión de Sinaa, en Hasaka, donde son hacinados en celdas sin acceso a la luz solar. Según los guardias de la prisión de la zona, no hay suficiente comida ni atención médica. [232] Cuando los muchachos llegan a los 18 años, son enviados a la población penitenciaria regular, donde los miembros del ISIS heridos son colocados de tres en tres por cama. [232]

El 2 de enero de 2013, las Naciones Unidas declararon que 60.000 personas habían muerto desde que comenzó la guerra civil, y la Alta Comisionada de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos, Navi Pillay, afirmó que "el número de víctimas es mucho mayor de lo que esperábamos y es verdaderamente impactante". [234] Cuatro meses después, la cifra actualizada de la ONU sobre el número de muertos había llegado a 80.000. [235] El 13 de junio de 2013, la ONU publicó una cifra actualizada de personas muertas desde que comenzaron los combates, que era exactamente 92.901, hasta finales de abril de 2013. Navi Pillay , Alta Comisionada de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos, declaró que: "Es muy probable que se trate de una cifra mínima de víctimas". Se estimó que el número real de víctimas era superior a 100.000. [236] [237] Algunas zonas del país se han visto afectadas desproporcionadamente por la guerra; según algunas estimaciones, hasta un tercio de todas las muertes se han producido en la ciudad de Homs . [238]

Un problema ha sido determinar el número de "combatientes armados" que han muerto, debido a que algunas fuentes cuentan a los combatientes rebeldes que no eran desertores del gobierno como civiles. [239] Se ha estimado que al menos la mitad de los muertos confirmados eran combatientes de ambos bandos, incluidos 52.290 combatientes del gobierno y 29.080 rebeldes, con otras 50.000 muertes de combatientes no confirmadas. [240] Además, UNICEF informó que más de 500 niños habían sido asesinados a principios de febrero de 2012, [241] y otros 400 niños habrían sido arrestados y torturados en cárceles sirias; [242] ambos informes han sido refutados por el gobierno sirio. Además, se sabe que más de 600 detenidos y presos políticos han muerto bajo tortura. [243] A mediados de octubre de 2012, el grupo activista de la oposición SOHR informó que el número de niños muertos en el conflicto había aumentado a 2.300, [244] y en marzo de 2013, fuentes de la oposición afirmaron que más de 5.000 niños habían sido asesinados. [245] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ] En enero de 2014, se publicó un informe que detallaba el asesinato sistemático de más de 11.000 detenidos del gobierno sirio. [246]

El 20 de agosto de 2014, un nuevo estudio de la ONU concluyó que al menos 191.369 personas habían muerto en el conflicto sirio. [247] Posteriormente, la ONU dejó de recopilar estadísticas, pero un estudio del Centro Sirio de Investigación Política publicado en febrero de 2016 estimó que el número de muertos era de 470.000, con 1,9 millones de heridos (lo que supone un total del 11,5% de la población total herida o muerta). [248] Un informe de la SNHR pro-oposición en 2018 mencionó 82.000 víctimas que habían sido desaparecidas por la fuerza por el gobierno sirio, sumadas a 14.000 muertes confirmadas debido a la tortura. [249] Según varios observadores de la guerra, las Fuerzas Armadas Sirias y las fuerzas pro-Assad han sido responsables de más del 90% del total de víctimas civiles en la guerra civil. [f]

El 15 de abril de 2017, un convoy de autobuses que transportaba evacuados de las ciudades chiítas sitiadas de al-Fu'ah y Kafriya , que estaban rodeadas por el Ejército de la Conquista , [258] fue atacado por un terrorista suicida al oeste de Alepo, [259] matando a más de 126 personas, incluidos al menos 80 niños. [260] El 1 de enero de 2020, al menos ocho civiles, incluidos cuatro niños, murieron en un ataque con cohetes contra una escuela en Idlib por parte de las fuerzas del gobierno sirio, dijo el Observatorio Sirio de Derechos Humanos (SOHR). [261]

En enero de 2020, UNICEF advirtió que los niños eran los más afectados por la creciente violencia en el noroeste de Siria. Más de 500 niños resultaron heridos o murieron durante los primeros tres trimestres de 2019, y más de 65 niños fueron víctimas de la guerra solo en diciembre. [262]

Más de 380.000 personas han muerto desde que comenzó la guerra en Siria hace nueve años, según afirmó el 4 de enero de 2020 el Observatorio Sirio de Derechos Humanos, un organismo que supervisa la guerra. El número de muertos incluye civiles, soldados gubernamentales, miembros de milicias y tropas extranjeras. [263]

En un ataque aéreo de las fuerzas rusas leales al gobierno sirio, murieron al menos cinco civiles, de los cuales cuatro pertenecían a la misma familia. El Observatorio Sirio de Derechos Humanos afirmó que entre los muertos había tres niños tras el ataque en la región de Idlib el 18 de enero de 2020. [264]

El 30 de enero de 2020, los ataques aéreos rusos contra un hospital y una panadería mataron a más de 10 civiles en la región siria de Idlib. Moscú rechazó de inmediato la acusación. [265]

El 23 de junio de 2020, siete combatientes, incluidos dos sirios , murieron en ataques israelíes en una provincia central. Los medios estatales citaron a un funcionario militar que dijo que el ataque tenía como objetivo puestos en zonas rurales de la provincia de Hama . [266]

Apenas cuatro días después de que comenzara 2022, dos niños fueron asesinados y otros cinco resultaron heridos en el noroeste de Siria. Solo en 2021, más del 70% de los ataques violentos contra niños se han registrado en la región. [267]

El 14 de enero de 2022, una persona murió a causa de un coche bomba y varias más resultaron heridas en la ciudad de Azaz , en el noroeste de Siria, tres personas resultaron heridas en un mercado en un presunto atentado suicida en la ciudad de Al Bab y otra bomba suicida explotó en la ciudad de Afrin en una rotonda. [268]

Las Naciones Unidas y las organizaciones de derechos humanos han afirmado que tanto el gobierno como las fuerzas rebeldes han cometido violaciones de los derechos humanos, y que "la gran mayoría de los abusos han sido cometidos por el gobierno sirio". [269] Numerosos abusos de los derechos humanos , represión política , crímenes de guerra y crímenes contra la humanidad perpetrados por el gobierno de Assad a lo largo del conflicto han dado lugar a la condena internacional y a llamamientos generalizados para condenar a Bashar al-Assad en la Corte Penal Internacional (CPI). [g] La escala sin precedentes de las atrocidades lanzadas por las fuerzas gubernamentales desde el estallido de la revolución siria ha provocado indignación internacional, y la membresía de Siria fue suspendida de varias organizaciones internacionales. [275] [276]

Según tres abogados internacionales, [277] los funcionarios del gobierno sirio podrían enfrentar cargos por crímenes de guerra a la luz de un enorme alijo de evidencia sacada de contrabando del país que muestra el "asesinato sistemático" de unos 11.000 detenidos . La mayoría de las víctimas eran hombres jóvenes y muchos cadáveres estaban demacrados, manchados de sangre y presentaban signos de tortura. Algunos no tenían ojos; otros mostraban signos de estrangulamiento o electrocución. [278] Los expertos dijeron que esta evidencia era más detallada y a una escala mucho mayor que cualquier otra cosa que hubiera surgido de la crisis que entonces duraba 34 meses. [279] Las atrocidades cometidas por el régimen de Assad han sido descritas como los "mayores crímenes de guerra del siglo XXI", con escalofriantes revelaciones de tortura , violaciones , masacres y exterminio que se filtraron a través del Informe César de 2014 , que contenía evidencia fotográfica reunida por un fotógrafo del ejército disidente que trabajaba en prisiones militares baazistas . [276] Según el abogado internacional Stephen Rapp :

Tenemos mejores pruebas —contra Assad y su camarilla— que las que teníamos contra Milosevic en Yugoslavia , o que las que teníamos en cualquiera de los tribunales de crímenes de guerra en los que he participado, hasta cierto punto, incluso mejores que las que teníamos contra los nazis en Nuremberg , porque los nazis en realidad no tomaron fotografías individuales de cada una de sus víctimas con información de identificación sobre ellas. [276]

La ONU informó en 2014 que " la guerra de asedio se emplea en un contexto de atroces violaciones de los derechos humanos y del derecho internacional humanitario. Las partes en conflicto no temen rendir cuentas por sus actos". Las fuerzas armadas de ambos lados del conflicto bloquearon el acceso de los convoyes humanitarios, confiscaron alimentos, cortaron el suministro de agua y atacaron a los agricultores que trabajaban en sus campos. El informe señaló cuatro lugares asediados por las fuerzas gubernamentales: Muadamiyah , Daraya , el campamento de Yarmouk y la ciudad vieja de Homs, así como dos áreas bajo asedio de grupos rebeldes: Alepo y Hama. [280] [281] En el campamento de Yarmouk, 20.000 residentes se enfrentaron a la muerte por inanición debido al bloqueo de las fuerzas del gobierno sirio y los combates entre el ejército y Jabhat al-Nusra , que impide la distribución de alimentos por parte de la UNRWA. [280] [282] En julio de 2015, la ONU eliminó a Yarmouk de su lista de zonas sitiadas en Siria, a pesar de no haber podido entregar ayuda allí durante cuatro meses, y se negó a decir por qué lo había hecho. [283] Después de intensos combates en abril/mayo de 2018, las fuerzas del gobierno sirio finalmente tomaron el campamento, cuya población ahora se redujo a 100-200 personas. [284]

Las fuerzas del ISIS también han sido criticadas por la ONU por utilizar ejecuciones públicas y asesinatos de cautivos , amputaciones y azotes en una campaña para infundir miedo. "Las fuerzas del Estado Islámico de Irak y el Levante han cometido torturas, asesinatos, actos equivalentes a desapariciones forzadas y desplazamientos forzados como parte de los ataques contra la población civil en las provincias de Alepo y Raqqa, que constituyen crímenes contra la humanidad", afirma el informe del 27 de agosto de 2014. [285] El ISIS también persiguió a hombres homosexuales y bisexuales . [286]

Las desapariciones forzadas y las detenciones arbitrarias también han sido una característica desde que comenzó el levantamiento sirio. [287] Un informe de Amnistía Internacional , publicado en noviembre de 2015, afirmó que el gobierno sirio ha hecho desaparecer por la fuerza a más de 65.000 personas desde el comienzo de la guerra civil siria. [288] Según un informe de mayo de 2016 del Observatorio Sirio de Derechos Humanos , al menos 60.000 personas han sido asesinadas desde marzo de 2011 a través de torturas o por las malas condiciones humanitarias en las cárceles del gobierno sirio. [289]

En febrero de 2017, Amnistía Internacional publicó un informe en el que se afirmaba que el gobierno sirio había asesinado a unas 13.000 personas, en su mayoría civiles, en la prisión militar de Saydnaya . Afirmaban que los asesinatos habían comenzado en 2011 y que todavía se estaban produciendo. Amnistía Internacional describió esto como una "política de exterminio deliberado" y también afirmó que "estas prácticas, que constituyen crímenes de guerra y crímenes contra la humanidad, están autorizadas en los niveles más altos del gobierno sirio". [290] Tres meses después, el Departamento de Estado de los Estados Unidos declaró que se había identificado un crematorio cerca de la prisión. Según Estados Unidos, se estaba utilizando para quemar miles de cadáveres de personas asesinadas por las fuerzas del gobierno y para encubrir pruebas de atrocidades y crímenes de guerra. [291] Amnistía Internacional expresó su sorpresa por los informes sobre el crematorio, ya que las fotografías utilizadas por los EE. UU. son de 2013 y no las consideraron concluyentes, y funcionarios gubernamentales fugitivos han declarado que el gobierno entierra a sus ejecutados en cementerios en terrenos militares en Damasco. [292] El gobierno sirio dijo que los informes no eran ciertos.

En julio de 2012, el grupo de derechos humanos Women Under Siege había documentado más de 100 casos de violación y agresión sexual durante el conflicto, y muchos de estos crímenes fueron perpetrados por la Shabiha y otras milicias pro gubernamentales. Entre las víctimas había hombres, mujeres y niños, y aproximadamente el 80% de las víctimas conocidas eran mujeres y niñas. [293] [ se necesita una fuente más precisa ]

El 11 de septiembre de 2019, los investigadores de la ONU afirmaron que los ataques aéreos llevados a cabo por la coalición liderada por Estados Unidos en Siria habían matado o herido a varios civiles, lo que indica que no se tomaron las precauciones necesarias, lo que dio lugar a posibles crímenes de guerra. [294]

A finales de 2019, cuando la violencia se intensificó en el noroeste de Siria, miles de mujeres y niños fueron retenidos en "condiciones inhumanas" en un campamento remoto, según afirmaron investigadores designados por la ONU. [295] En octubre de 2019, Amnistía Internacional afirmó que había reunido pruebas de crímenes de guerra y otras violaciones cometidas por fuerzas turcas y sirias respaldadas por Turquía, que, al parecer, "han mostrado un vergonzoso desprecio por la vida civil, llevando a cabo graves violaciones y crímenes de guerra, incluidos asesinatos sumarios y ataques ilegales que han matado y herido a civiles". [30]

Según un informe de 2020 elaborado por investigadores de la guerra civil siria respaldados por las Naciones Unidas, niñas de nueve años o más han sido violadas y conducidas a esclavitud sexual, mientras que los niños han sido sometidos a torturas y entrenados a la fuerza para ejecutar asesinatos en público. Los niños han sido atacados por francotiradores y engañados para que sean moneda de cambio para pedir rescates. [296]

El 6 de abril de 2020, las Naciones Unidas publicaron su investigación sobre los ataques a los sitios humanitarios en Siria . En sus informes, el Consejo afirmó que había examinado seis sitios de ataques y concluyó que los ataques aéreos habían sido llevados a cabo por el "Gobierno de Siria y/o sus aliados". Sin embargo, el informe fue criticado por ser parcial hacia Rusia y no nombrarla, a pesar de que existían pruebas adecuadas. "La negativa a nombrar explícitamente a Rusia como parte responsable que trabaja junto con el gobierno sirio... es profundamente decepcionante", citó HRW. [297]

El 27 de abril de 2020, la Red Siria de Derechos Humanos informó de que se habían producido múltiples delitos en Siria durante los meses de marzo y abril . La organización de derechos humanos denunció que el régimen sirio había diezmado a 44 civiles, incluidos seis niños, durante los tiempos sin precedentes de la COVID-19 . También afirmó que las fuerzas sirias mantuvieron cautivas a 156 personas y cometieron un mínimo de cuatro ataques contra instalaciones civiles vitales. El informe recomendó además que las Naciones Unidas impusieran sanciones al régimen de Bashar al-Assad si seguía cometiendo violaciones de los derechos humanos. [298]

El 8 de mayo de 2020, la Alta Comisionada de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos, Michelle Bachelet, expresó su profunda preocupación por el hecho de que los grupos rebeldes, incluidos los combatientes terroristas del EIIL , puedan estar utilizando la pandemia de COVID-19 como "una oportunidad para reagruparse e infligir violencia en el país". [299]

El 21 de julio de 2020, las fuerzas del Gobierno sirio llevaron a cabo un ataque y mataron a dos civiles con cuatro cohetes Grad en el subdistrito occidental de Al-Bab. [300]

El 14 de enero de 2022, en la ciudad de Azaz, en manos de los rebeldes, al noroeste de Siria, explotó un coche bomba que mató a una persona e hirió a varios transeúntes. Según un miembro del equipo de rescate, se había colocado un artefacto explosivo improvisado en el interior de un coche y luego el coche fue colocado cerca de una oficina de transporte local de la ciudad, que está cerca de la frontera turca. En la ciudad de Al Bab, explotó una bomba suicida que hirió a tres personas y, en la ciudad de Afrín, otra bomba suicida explotó en una rotonda. Estos tres atentados ocurrieron con un intervalo de horas y minutos entre sí. [268]

Según Aljazeera, un ataque con cohetes contra una ciudad del norte de Siria controlada por combatientes de la oposición respaldados por Turquía mató a seis civiles e hirió a más de una docena el 21 de enero de 2022. Según el Observatorio Sirio de Derechos Humanos, con sede en el Reino Unido, no estaba claro quién disparó los proyectiles de artillería, pero el ataque provino de una región poblada por combatientes kurdos y fuerzas del gobierno sirio. [301]

Tras un ataque a una cárcel siria el 23 de enero de 2022, más de 120 personas murieron en un conflicto en curso entre tropas lideradas por los kurdos y combatientes del EI (ISIS). Según el Observatorio Sirio de Derechos Humanos, con sede en el Reino Unido, "al menos 77 miembros del EI y 39 combatientes kurdos, incluidas fuerzas de seguridad interna, guardias de prisiones y fuerzas antiterroristas, murieron" en el ataque. [302] El 17 de diciembre de 2023, ocho civiles, incluida una mujer embarazada, murieron durante los bombardeos del Ejército Árabe Sirio en la ciudad de Darat Izza . El Observatorio Sirio de Derechos Humanos informó de que las fuerzas pro-Assad perpetraron deliberadamente una masacre "atacando directamente zonas residenciales, utilizando proyectiles de artillería y lanzacohetes". [303]

A medida que el conflicto se ha extendido por Siria, muchas ciudades se han visto envueltas en una ola de delincuencia, pues los combates han provocado la desintegración de gran parte del estado civil y muchas comisarías han dejado de funcionar. Los índices de robos han aumentado, y los delincuentes han saqueado casas y tiendas. También han aumentado los índices de secuestros. Se ha visto a combatientes rebeldes robando coches y, en un caso, destruyendo un restaurante en Alepo en el que se había visto a soldados sirios comiendo. [304]

Los comandantes locales de las Fuerzas Nacionales de Defensa a menudo se dedicaban a “ lucrarse con la guerra a través de extorsiones, saqueos y crimen organizado”. Los miembros de las NDF también estuvieron implicados en “oleadas de asesinatos, robos, hurtos, secuestros y extorsiones en las partes de Siria controladas por el gobierno desde la formación de la organización en 2013”, según informó el Instituto para el Estudio de la Guerra. [305]

Criminal networks have been used by both the government and the opposition during the conflict. Facing international sanctions, the Syrian government relied on criminal organizations to smuggle goods and money in and out of the country. The economic downturn caused by the conflict and sanctions also led to lower wages for Shabiha members. In response, some Shabiha members began stealing civilian properties and engaging in kidnappings.[306] Rebel forces sometimes rely on criminal networks to obtain weapons and supplies. Black market weapon prices in Syria's neighboring countries have significantly increased since the start of the conflict. To generate funds to purchase arms, some rebel groups have turned towards extortion, theft and kidnapping.[306]

Syria has become the chief location for manufacturing of Captagon, an illegal amphetamine. Drugs manufactured in Syria have found their way across the Gulf, Jordan and Europe but have at times been intercepted. In January 2022, a Jordanian army officer was shot and killed and three army personnel injured after a shoot out erupted between drug smugglers and the army. The Jordanian army has said that it shot down a drone in 2021 that was being used to smuggle a substantial amount of drugs across the Jordanian border.[307]

The World Health Organization has reported that 35% of the country's hospitals are out of service. Fighting makes it impossible to undertake the normal vaccination programs. The displaced refugees may also pose a disease risk to countries to which they have fled.[308] Four hundred thousand civilians were isolated by the Siege of Eastern Ghouta from April 2013 to April 2018, resulting in acutely malnourished children according to the United Nations Special Advisor, Jan Egeland, who urged the parties for medical evacuations. 55,000 civilians are also isolated in the Rukban refugee camp between Syria and Jordan, where humanitarian relief access is difficult due to the harsh desert conditions. Humanitarian aid reaches the camp only sporadically, sometimes taking three months between shipments.[309][310]

Formerly rare infectious diseases have spread in rebel-held areas brought on by poor sanitation and deteriorating living conditions. The diseases have primarily affected children. These include measles, typhoid, hepatitis, dysentery, tuberculosis, diphtheria, whooping cough and the disfiguring skin disease leishmaniasis. Of particular concern is the contagious and crippling Poliomyelitis. As of late 2013 doctors and international public health agencies have reported more than 90 cases. Critics of the government complain that, even before the uprising, it contributed to the spread of disease by purposefully restricting access to vaccination, sanitation and access to hygienic water in "areas considered politically unsympathetic".[311]

In June 2020, the United Nations reported that after more than nine years of war, Syria was falling into an even deeper crisis and economic deterioration as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. As of 26 June, a total of 248 people were infected by COVID-19, out of which nine people died. Restrictions on the importation of medical supplies, limited access to essential equipment, reduced outside support and ongoing attacks on medical facilities left Syria's health infrastructure in peril, and unable to meet the needs of its population. Syrian communities were additionally facing unprecedented levels of hunger crisis.[312]

In September 2022, the UN representative in Syria reported that several regions in the country were witnessing a cholera outbreak. UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator Imran Riza called for an urgent response to contain the outbreak, saying that it posed "a serious threat to people in Syria". The outbreak was linked to the use of contaminated water for growing crops and the reliance of people on unsafe water sources.[313]

The conflict holds the record for the largest sum ever requested by UN agencies for a single humanitarian emergency, $6.5 billion worth of requests of December 2013.[314] The international humanitarian response to the conflict in Syria is coordinated by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) in accordance with General Assembly Resolution 46/182.[315] The primary framework for this coordination is the Syria Humanitarian Assistance Response Plan (SHARP) which appealed for US$1.41 billion to meet the humanitarian needs of Syrians affected by the conflict.[316] Official United Nations data on the humanitarian situation and response is available at an official website managed by UNOCHA Syria (Amman).[317] UNICEF is also working alongside these organizations to provide vaccinations and care packages to those in need. Financial information on the response to the SHARP and assistance to refugees and for cross-border operations can be found on UNOCHA's Financial Tracking Service. As of 19 September 2015, the top ten donors to Syria were United States, European Commission, United Kingdom, Kuwait, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Japan, UAE and Norway.[318]

The difficulty of delivering humanitarian aid to people is indicated by the statistics for January 2015: of the estimated 212,000 people during that month who were besieged by government or opposition forces, 304 were reached with food.[319] USAID and other government agencies in US delivered nearly $385 million of aid items to Syria in 2012 and 2013. The United States has provided food aid, medical supplies, emergency and basic health care, shelter materials, clean water, hygiene education and supplies, and other relief supplies.[320] Islamic Relief has stocked 30 hospitals and sent hundreds of thousands of medical and food parcels.[321]

Other countries in the region have also contributed various levels of aid. Iran has been exporting between 500 and 800 tonnes of flour daily to Syria.[322] Israel supplied aid through Operation Good Neighbor, providing medical treatment to 750 Syrians in a field hospital located in Golan Heights where rebels say that 250 of their fighters were treated.[323] Israel established two medical centers inside Syria. Israel also delivered heating fuel, diesel fuel, seven electric generators, water pipes, educational materials, flour for bakeries, baby food, diapers, shoes and clothing. Syrian refugees in Lebanon make up one quarter of Lebanon's population, mostly consisting of women and children.[324] In addition, Russia has said it created six humanitarian aid centers within Syria to support 3000 refugees in 2016.[325]

On 9 April 2020, the UN dispatched 51 truckloads of humanitarian aid to Idlib. The organization said that the aid would be distributed among civilians stranded in the north-western part of the country.[326]

On 30 April 2020, Human Rights Watch condemned the Syrian authorities for their longstanding restriction on the entry of aid supplies.[327] It also demanded the World Health Organization to keep pushing the UN to allow medical aid and other essentials to reach Syria via the Iraq border crossing, to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in the war-torn nation. The aid supplies, if allowed, will allow the Syrian population to protect themselves from contracting the COVID-19 virus.[328]

As of December 2019, a diplomatic dispute is occurring at the UN over re-authorization of cross-border aid for refugees. China and Russia oppose the draft resolution that seeks to re-authorize crossing points in Turkey, Iraq and Jordan; China and Russia, as allies of Assad, seek to close the two crossing points in Iraq and Jordan, and to leave only the two crossing points in Turkey active.[329] The current authorization expired on 10 January 2020.[330]

All of the ten individuals representing the non-permanent members of the Security Council stood in the corridor outside of the chamber speaking to the press to state that all four crossing points are crucial and must be renewed.[329]

United Nations official Mark Lowcock is asking the UN to re-authorize cross-border aid to enable aid to continue to reach refugees in Syria. He says there is no other way to deliver the aid that is needed. He noted that four million refugees out of the over eleven million refugees who need assistance are being reached through four specific international crossing points. Lowcock serves as the United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator and the Head of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.[331]

Russia, aided by China's support, has vetoed the resolution to retain all four border crossings. An alternate resolution also did not pass.[332][333] The U.S. strongly criticized the vetoes and opposition by Russia and China.[334][335] China explained the reason for veto is the concern of "unilateral coercive measures" by certain states causing humanitarian suffering on the Syrian people. It views lifting all unilateral sanctions respecting Syrian sovereignty and for humanitarian reasons is a must.[336]

As of March 2015[update], the war has affected 290 heritage sites, severely damaged 104, and completely destroyed 24.[needs update] Five of the six UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Syria have been damaged.[201] Destruction of antiquities has been caused by shelling, army entrenchment, and looting at various tells, museums and monuments.[337] A group called Syrian Archaeological Heritage Under Threat is monitoring and recording the destruction in an attempt to create a list of heritage sites damaged during the war and to gain global support for the protection and preservation of Syrian archaeology and architecture.[338]

UNESCO listed all six Syria's World Heritage Sites as endangered but direct assessment of damage is not possible. It is known that the Old City of Aleppo was heavily damaged during battles being fought within the district, while Palmyra and Krak des Chevaliers suffered minor damage. Illegal digging is said to be a grave danger, and hundreds of Syrian antiquities, including some from Palmyra, appeared in Lebanon. Three archeological museums are known to have been looted; in Raqqa some artifacts seem to have been destroyed by foreign Islamists due to religious objections.[339]

In 2014 and 2015, following the rise of the Islamic State, several sites in Syria were destroyed by the group as part of a deliberate destruction of cultural heritage sites. In Palmyra, the group destroyed many ancient statues, the Temples of Baalshamin and Bel, many tombs including the Tower of Elahbel and part of the Monumental Arch.[340] The 13th-century Palmyra Castle was extensively damaged by retreating militants during the Palmyra offensive in March 2016.[341] IS also destroyed ancient statues in Raqqa,[342] and a number of churches, including the Armenian Genocide Memorial Church in Deir ez-Zor.[343]

In January 2018 Turkish airstrikes seriously damaged an ancient Neo-Hittite temple in Syria's Kurdish-held Afrin region. It was built by the Arameans in the first millennium BC.[344] According to a September 2019 report published by the Syrian Network for Human Rights, more than 120 Christian churches have been destroyed or damaged in Syria since 2011.[345]

The war has inspired its own particular artwork, done by Syrians. A late summer 2013 exhibition in London at the P21 Gallery showed some of this work, which had to be smuggled out of Syria.[346]

The Syrian civil war is one of the most heavily documented wars in history, despite the extreme dangers that journalists face while in Syria.[347]

On 19 August 2014, American journalist James Foley was executed by ISIL, who said it was in retaliation for the United States operations in Iraq. Foley was kidnapped in Syria in November 2012 by Shabiha militia.[348] ISIL also threatened to execute Steven Sotloff, who was kidnapped at the Syrian–Turkish border in August 2013.[349] There were reports ISIS captured a Japanese national, two Italian nationals, and a Danish national as well.[350] Sotloff was later executed in September 2014. At least 70 journalists have been killed covering the Syrian war, and more than 80 kidnapped, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.[351] On 22 August 2014, the al-Nusra Front released a video of captured Lebanese soldiers and demanded Hezbollah withdraw from Syria under threat of their execution.[352]

.jpg/440px-Esther_Brimmer_Speaks_at_Human_Rights_Council_Urgent_Debate_on_Syria_(3).jpg)