La historia de Lituania se remonta a asentamientos fundados hace unos 10.000 años, [1] [2] pero el primer registro escrito del nombre del país se remonta al año 1009 d. C. [3] Los lituanos , uno de los pueblos bálticos , conquistaron posteriormente tierras vecinas y establecieron el Gran Ducado de Lituania en el siglo XIII (y también un efímero Reino de Lituania ). El Gran Ducado fue un estado guerrero exitoso y duradero. Se mantuvo ferozmente independiente y fue una de las últimas áreas de Europa en adoptar el cristianismo (a partir del siglo XIV). Una potencia formidable, se convirtió en el estado más grande de Europa en el siglo XV y se extendió desde el mar Báltico hasta el mar Negro , a través de la conquista de grandes grupos de eslavos orientales que residían en Rutenia . [4]

En 1385, el Gran Ducado formó una unión dinástica con Polonia a través de la Unión de Krewo . Más tarde, la Unión de Lublin (1569) creó la Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania . Durante la Segunda Guerra del Norte , el Gran Ducado buscó protección bajo el Imperio sueco a través de la Unión de Kėdainiai en 1655. Sin embargo, pronto volvió a ser parte del estado polaco-lituano, que persistió hasta 1795, cuando la última de las Particiones de Polonia borró tanto a Lituania como a Polonia independientes del mapa político. Después de la disolución , los lituanos vivieron bajo el gobierno del Imperio ruso hasta el siglo XX, aunque hubo varias rebeliones importantes, especialmente en 1830-1831 y 1863 .

El 16 de febrero de 1918, Lituania se restableció como un estado democrático. Permaneció independiente hasta el inicio de la Segunda Guerra Mundial , cuando fue ocupada por la Unión Soviética según los términos del Pacto Mólotov-Ribbentrop . Después de una breve ocupación por parte de la Alemania nazi después de que los nazis libraran una guerra contra la Unión Soviética , Lituania fue nuevamente absorbida por la Unión Soviética durante casi 50 años. En 1990-1991, Lituania restableció su soberanía con la Ley de Restablecimiento del Estado de Lituania . Lituania se unió a la alianza de la OTAN en 2004 y a la Unión Europea como parte de su ampliación en 2004 .

.jpg/440px-Lithuania_(32).jpg)

Los primeros humanos llegaron al territorio de la actual Lituania en la segunda mitad del X milenio a. C., después de que los glaciares retrocedieran al final del último período glaciar . [2] Según la historiadora Marija Gimbutas , estas personas vinieron de dos direcciones: la península de Jutlandia y de la actual Polonia . Trajeron dos culturas diferentes, como lo demuestran las herramientas que usaban. Eran cazadores itinerantes y no formaron asentamientos estables. En el VIII milenio a. C., el clima se volvió mucho más cálido y se desarrollaron los bosques. Los habitantes de lo que hoy es Lituania viajaron menos y se dedicaron a la caza local, la recolección y la pesca de agua dulce. Durante el VI-V milenio a. C., se domesticaron varios animales y las viviendas se volvieron más sofisticadas para albergar a familias más numerosas. La agricultura no surgió hasta el III milenio a. C. debido a un clima y un terreno duros y a la falta de herramientas adecuadas para cultivar la tierra. La artesanía y el comercio también comenzaron a formarse en esta época.

Los hablantes del indoeuropeo noroccidental podrían haber llegado con la cultura de la cerámica cordada alrededor del 3200/3100 a. C. [5]

Los primeros lituanos eran una rama de un antiguo grupo conocido como los bálticos . [a] Las principales divisiones tribales de los bálticos eran los antiguos prusianos y yotvingios del Báltico occidental , y los lituanos y letones del Báltico oriental . Los bálticos hablaban formas de las lenguas indoeuropeas . [7] Hoy en día, las únicas nacionalidades bálticas restantes son los lituanos y los letones, pero hubo más grupos o tribus bálticas en el pasado. Algunos de estos se fusionaron en lituanos y letones ( samogitios , selonios , curonianos , semigalios ), mientras que otros ya no existían después de que fueran conquistados y asimilados por el Estado de la Orden Teutónica (antiguos prusianos, yotvingios, sambianos , escalvios y galindios ). [8]

Las tribus bálticas no mantuvieron estrechos contactos culturales o políticos con el Imperio romano , pero sí mantuvieron contactos comerciales (véase Ruta del Ámbar ). Tácito , en su estudio Germania , describió a los aesti , habitantes de las costas del sureste del mar Báltico que probablemente eran bálticos, alrededor del año 97 d. C. [9] Los bálticos occidentales se diferenciaron y fueron conocidos primero por los cronistas externos. Ptolomeo en el siglo II d. C. conocía a los galindios y yotvingios, y los primeros cronistas medievales mencionaron a los prusianos, curonianos y semigalianos. [10]

Lituania, situada a lo largo de la cuenca baja y media del río Niemen , comprendía principalmente las regiones culturalmente diferentes de Samogitia (conocida por sus entierros esqueléticos medievales tempranos), y más al este Aukštaitija , o Lituania propiamente dicha (conocida por sus entierros de cremación medievales tempranos). [11] El área era remota y poco atractiva para los forasteros, incluidos los comerciantes, lo que explica su identidad lingüística, cultural y religiosa separada y su integración tardía en los patrones y tendencias generales europeos. [7]

El idioma lituano se considera muy conservador debido a su estrecha conexión con las raíces indoeuropeas. Se cree que se diferenció del idioma letón , el idioma existente más estrechamente relacionado, alrededor del siglo VII. [12] Las costumbres y la mitología paganas lituanas tradicionales , con muchos elementos arcaicos, se conservaron durante mucho tiempo. Los cuerpos de los gobernantes fueron incinerados hasta la cristianización de Lituania : han sobrevivido las descripciones de las ceremonias de cremación de los grandes duques Algirdas y Kęstutis . [13]

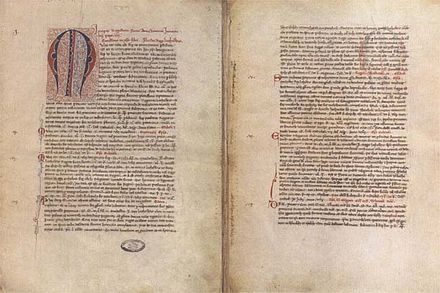

Se cree que la tribu lituana se desarrolló de manera más reconocible hacia fines del primer milenio . [10] La primera referencia conocida a Lituania como nación ("Litua") proviene de los Anales del monasterio de Quedlinburg , fechados el 9 de marzo de 1009. [14] En 1009, el misionero Bruno de Querfurt llegó a Lituania y bautizó al gobernante lituano como "Rey Nethimer". [15]

Desde el siglo IX al XI, los bálticos costeros fueron objeto de incursiones por parte de los vikingos , y los reyes de Dinamarca cobraron tributos en ocasiones. Durante los siglos X y XI, los territorios lituanos se encontraban entre las tierras que pagaban tributo a la Rus de Kiev , y Yaroslav el Sabio estaba entre los gobernantes rutenos que invadieron Lituania (a partir de 1040). Desde mediados del siglo XII, fueron los lituanos quienes invadieron los territorios rutenos. En 1183, Polotsk y Pskov fueron devastadas, e incluso la lejana y poderosa República de Nóvgorod se vio amenazada repetidamente por las incursiones de la emergente maquinaria de guerra lituana hacia finales del siglo XII. [16]

En el siglo XII y después, se produjeron esporádicamente incursiones mutuas en las que participaban fuerzas lituanas y polacas, pero los dos países estaban separados por las tierras de los yotvingios . A finales del siglo XII se produjo una expansión oriental de colonos alemanes (la Ostsiedlung ) hasta la desembocadura del río Daugava . En esa época y a finales del siglo se produjeron enfrentamientos militares con los lituanos, pero por el momento los lituanos tenían la ventaja. [17]

Desde finales del siglo XII, Lituania contaba con una fuerza militar organizada que se utilizaba para realizar incursiones externas, saqueos y la captura de esclavos. Estas actividades militares y pecuniarias fomentaron la diferenciación social y desencadenaron una lucha por el poder en Lituania. Esto dio inicio a la formación de un Estado primitivo, a partir del cual se desarrolló el Gran Ducado de Lituania . [7] En 1231, el Libro del Censo danés menciona que las tierras bálticas pagaban tributo a los daneses, incluida Lituania ( Littonia ). [18]

Desde principios del siglo XIII, las frecuentes incursiones militares en el extranjero se hicieron posibles gracias a la creciente cooperación y coordinación entre las tribus bálticas. [7] Cuarenta expediciones de este tipo tuvieron lugar entre 1201 y 1236 contra Rutenia, Polonia, Letonia y Estonia, que estaban siendo conquistadas por la Orden de Livonia . Pskov fue saqueada e incendiada en 1213. [17] En 1219, veintiún jefes lituanos firmaron un tratado de paz con el estado de Galicia-Volinia . Este evento es ampliamente aceptado como la primera prueba de que las tribus bálticas se estaban uniendo y consolidando. [19]

A principios del siglo XIII, dos órdenes militares cruzadas alemanas , los Hermanos de la Espada de Livonia y los Caballeros Teutónicos , se establecieron en la desembocadura del río Daugava y en la Tierra de Chełmno respectivamente. Con el pretexto de convertir a la población al cristianismo, procedieron a conquistar gran parte del área que ahora es Letonia y Estonia , además de partes de Lituania. [7] En respuesta, varios pequeños grupos tribales bálticos se unieron bajo el gobierno de Mindaugas . Mindaugas, originalmente un kunigas o jefe mayor, uno de los cinco duques mayores enumerados en el tratado de 1219, es mencionado como el gobernante de toda Lituania a partir de 1236 en la Crónica rimada de Livonia . [20]

En 1236 el Papa declaró una cruzada contra los lituanos. [21] Los samogitianos , liderados por Vykintas , rival de Mindaugas, [22] derrotaron rotundamente a los Hermanos Livonios y sus aliados en la Batalla de Saule en 1236, lo que obligó a los Hermanos a fusionarse con los Caballeros Teutónicos en 1237. [23] Pero Lituania estaba atrapada entre las dos ramas de la Orden. [21]

Alrededor de 1240, Mindaugas gobernó sobre toda Aukštaitija . Después, conquistó la región de Rutenia Negra (que consistía en Grodno , Brest , Navahrudak y los territorios circundantes). [7] Mindaugas estaba en proceso de extender su control a otras áreas, matando rivales o enviando parientes y miembros de clanes rivales al este de Rutenia para que pudieran conquistar y establecerse allí. Lo hicieron, pero también se rebelaron. El duque ruteno Daniel de Galicia percibió una ocasión para recuperar Rutenia Negra y en 1249-1250 organizó una poderosa coalición anti-Mindaugas (y "antipagana") que incluía a los rivales de Mindaugas, los yotvingios, los samogitianos y los caballeros teutónicos de Livonia . Mindaugas, sin embargo, se aprovechó de los intereses divergentes en la coalición a la que se enfrentó. [24]

En 1250, Mindaugas firmó un acuerdo con la Orden Teutónica; consintió en recibir el bautismo (el acto tuvo lugar en 1251) y renunciar a su reclamo sobre algunas tierras en el oeste de Lituania, por lo que recibiría una corona real a cambio. [25] Mindaugas pudo entonces resistir un asalto militar de la coalición restante en 1251 y, apoyado por los Caballeros, emerger como vencedor para confirmar su gobierno sobre Lituania. [26]

El 17 de julio de 1251, el papa Inocencio IV firmó dos bulas papales que ordenaban al obispo de Chełmno coronar a Mindaugas como rey de Lituania , nombrar un obispo para Lituania y construir una catedral. [27] En 1253, Mindaugas fue coronado y se estableció un Reino de Lituania por primera y única vez en la historia de Lituania. [28] [29] Mindaugas "concedió" partes de Yotvingia y Samogitia que no controlaba a los Caballeros entre 1253 y 1259. Una paz con Daniel de Galicia en 1254 fue consolidada por un acuerdo matrimonial que involucraba a la hija de Mindaugas y al hijo de Daniel, Shvarn . El sobrino de Mindaugas, Tautvilas, regresó a su ducado de Pólatsk y Samogitia se separó, para pronto ser gobernada por otro sobrino, Treniota . [26]

En 1260, los samogitianos, victoriosos sobre los Caballeros Teutónicos en la Batalla de Durbe , acordaron someterse al gobierno de Mindaugas con la condición de que abandonara la religión cristiana; el rey cumplió poniendo fin a la conversión emergente de su país, renovó la guerra antiteutónica (en la lucha por Samogitia) [30] y expandió aún más sus posesiones rutenas. [31] No está claro si esto fue acompañado por su apostasía personal . [7] [30] Mindaugas estableció así los principios básicos de la política lituana medieval: defensa contra la expansión de la Orden alemana desde el oeste y el norte y conquista de Rutenia en el sur y el este. [7]

Mindaugas fue el principal fundador del Estado lituano. Estableció durante un tiempo un reino cristiano bajo el papado en lugar del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico , en una época en la que los pueblos paganos que quedaban en Europa ya no se convertían pacíficamente, sino que eran conquistados. [32]

Mindaugas fue asesinado en 1263 por Daumantas de Pskov y Treniota , un evento que resultó en gran disturbios y guerra civil. Treniota, quien asumió el gobierno de los territorios lituanos, asesinó a Tautvilas, pero él mismo fue asesinado en 1264. El gobierno del hijo de Mindaugas, Vaišvilkas, siguió. Fue el primer duque lituano conocido que se convirtió al cristianismo ortodoxo y se estableció en Rutenia, estableciendo un patrón a seguir por muchos otros. [30] Vaišvilkas fue asesinado en 1267. Se produjo una lucha de poder entre Shvarn y Traidenis ; terminó con una victoria para este último. El reinado de Traidenis (1269-1282) fue el más largo y estable durante el período de disturbios. Tradenis reunificó todas las tierras lituanas, invadió Rutenia y Polonia repetidamente con éxito, derrotó a los Caballeros Teutónicos en Prusia y en Livonia en la Batalla de Aizkraukle en 1279. También se convirtió en el gobernante de Yotvingia, Semigalia y Prusia oriental. Siguieron las relaciones amistosas con Polonia y en 1279, la hija de Tradenis, Gaudemunda de Lituania, se casó con Boleslao II de Mazovia , un duque Piast . [7] [31]

La Lituania pagana fue un objetivo de las cruzadas cristianas del norte de los Caballeros Teutónicos y la Orden de Livonia . [33] En 1241, 1259 y 1275, Lituania también fue devastada por las incursiones de la Horda de Oro , que anteriormente (1237-1240) debilitó a la Rus de Kiev . [31] Después de la muerte de Traidenis, los Caballeros alemanes finalizaron sus conquistas de las tribus del Báltico occidental, y pudieron concentrarse en Lituania, [34] especialmente en Samogitia, para conectar las dos ramas de la Orden. [31] Una oportunidad particular se abrió en 1274 después de la conclusión de la Gran Rebelión Prusiana y la conquista de la antigua tribu prusiana. Los Caballeros Teutónicos luego procedieron a conquistar otras tribus bálticas: los nadruvianos y los escalvios en 1274-1277 y los yotvingios en 1283. La Orden Livona completó su conquista de Semigalia, el último aliado báltico de Lituania, en 1291. [23]

La familia de Gediminas , cuyos miembros estaban a punto de formar la gran dinastía nativa de Lituania , [35] asumió el gobierno del Gran Ducado en 1285 bajo Butigeidis . Vytenis (r. 1295-1315) y Gediminas (r. 1315-1341), de quien se nombró la dinastía Gediminid , tuvieron que lidiar con constantes incursiones de las órdenes teutónicas que eran costosas de rechazar. Vytenis los combatió eficazmente alrededor de 1298 y aproximadamente al mismo tiempo pudo aliar a Lituania con los burgueses alemanes de Riga . Por su parte, los caballeros prusianos instigaron una rebelión en Samogitia contra el gobernante lituano en 1299-1300, seguida de veinte incursiones allí en 1300-15. [31] Gediminas también luchó contra los Caballeros Teutónicos, y además de eso hizo astutas maniobras diplomáticas cooperando con el gobierno de Riga en 1322-23 y aprovechándose del conflicto entre los Caballeros y el arzobispo Friedrich von Pernstein de Riga. [36]

Gediminas amplió las conexiones internacionales de Lituania manteniendo correspondencia con el Papa Juan XXII , así como con gobernantes y otros centros de poder en Europa occidental, e invitó a los colonos alemanes a establecerse en Lituania. [37] En respuesta a las quejas de Gediminas sobre la agresión de la Orden Teutónica, el Papa obligó a los Caballeros a observar una paz de cuatro años con Lituania entre 1324 y 1327. [36] Los legados del Papa investigaron las oportunidades para la cristianización de Lituania, pero no tuvieron éxito. [36] Desde la época de Mindaugas, los gobernantes del país intentaron romper el aislamiento cultural de Lituania, unirse a la cristiandad occidental y así estar protegidos de los Caballeros, pero los Caballeros y otros intereses habían podido bloquear el proceso. [38] En el siglo XIV, los intentos de Gediminas de bautizarse (1323-1324) y establecer el cristianismo católico en su país fueron frustrados por los samogitianos y los cortesanos ortodoxos de Gediminas. [37] En 1325, Casimiro , hijo del rey polaco Vladislao I , se casó con la hija de Gediminas, Aldona , que se convirtió en reina de Polonia cuando Casimiro ascendió al trono polaco en 1333. El matrimonio confirmó el prestigio del estado lituano bajo Gediminas, y se concluyó una alianza defensiva con Polonia el mismo año. Las incursiones anuales de los Caballeros se reanudaron en 1328-1340, a las que los lituanos respondieron con incursiones en Prusia y Letonia. [7] [36]

El reinado del Gran Duque Gediminas constituyó el primer período en la historia de Lituania en el que el país fue reconocido como una gran potencia, principalmente debido a la extensión de su expansión territorial en Rutenia. [7] [39] Lituania era única en Europa como un "reino" gobernado por paganos y una potencia militar de rápido crecimiento suspendida entre los mundos de la cristiandad bizantina y latina . Para poder afrontar la extremadamente costosa defensa contra los Caballeros Teutónicos, tuvo que expandirse hacia el este. Gediminas logró la expansión oriental de Lituania desafiando a los mongoles , quienes desde la década de 1230 patrocinaron una invasión mongola de la Rus . [40] El colapso de la estructura política de la Rus de Kiev creó un vacío de poder regional parcial que Lituania pudo explotar. [38] A través de alianzas y conquistas, en competencia con el Principado de Moscú , [36] los lituanos finalmente obtuvieron el control de vastas extensiones de las porciones occidental y meridional de la antigua Rus de Kiev. [7] [39] Las conquistas de Gediminas incluyeron la región occidental de Smolensk , el sur de Polesia y (temporalmente) Kiev , que fue gobernada alrededor de 1330 por el hermano de Gediminas, Fiodor . [36] El área de Rutenia controlada por Lituania creció hasta incluir la mayor parte de las actuales Bielorrusia y Ucrania (la cuenca del río Dniéper ) y comprendía un estado masivo que se extendía desde el mar Báltico hasta el mar Negro en los siglos XIV y XV. [38] [39]

En el siglo XIV, muchos príncipes lituanos instalados para gobernar las tierras de Rutenia aceptaron el cristianismo oriental y asumieron las costumbres y los nombres rutenos para apelar a la cultura de sus súbditos. A través de este medio, la integración en la estructura estatal lituana se logró sin perturbar las formas de vida locales. [7] Los territorios rutenos adquiridos eran mucho más grandes, más densamente poblados y más desarrollados en términos de organización eclesiástica y alfabetización que los territorios del núcleo de Lituania. Así, el estado lituano pudo funcionar gracias a las contribuciones de los representantes de la cultura rutena . [38] Los territorios históricos de los antiguos ducados rutenos se conservaron bajo el gobierno lituano, y cuanto más lejos estaban de Vilna, más autónomas tendían a ser las localidades. [41] Los soldados lituanos y los rutenos defendieron juntos las fortalezas rutenas, a veces pagando tributo a la Horda de Oro por algunas de las localidades periféricas. [36] Las tierras rutenas pudieron haber sido gobernadas conjuntamente por Lituania y la Horda de Oro como condominios hasta la época de Vitautas , quien dejó de pagar tributo. [42] El estado de Gediminas proporcionó un contrapeso contra la influencia de Moscú y disfrutó de buenas relaciones con los principados rutenos de Pskov , Veliky Novgorod y Tver . Los enfrentamientos militares directos con el Principado de Moscú bajo Iván I ocurrieron alrededor de 1335. [36]

.jpg/440px-Algierd._Альгерд_(A._Guagnini,_1578).jpg)

Alrededor de 1318, el hijo mayor de Gediminas, Algirdas, se casó con María de Vítebsk , hija del príncipe Yaroslav de Vítebsk , y se estableció en Vítebsk para gobernar el principado. [36] De los siete hijos de Gediminas, cuatro permanecieron paganos y tres se convirtieron al cristianismo ortodoxo. [7] A su muerte, Gediminas dividió sus dominios entre los siete hijos, pero la precaria situación militar de Lituania, especialmente en la frontera teutónica, obligó a los hermanos a mantener unido el país. [43] A partir de 1345, Algirdas asumió el cargo de Gran Duque de Lituania. En la práctica, gobernó solo sobre la Rutenia lituana, mientras que Lituania propiamente dicha era el dominio de su igualmente capaz hermano Kęstutis . Algirdas luchó contra los tártaros de la Horda de Oro y el Principado de Moscú; Kęstutis asumió la exigente lucha con la Orden Teutónica. [7]

La guerra con la Orden Teutónica continuó desde 1345, y en 1348, los Caballeros derrotaron a los lituanos en la Batalla de Strėva . Kęstutis solicitó al rey Casimiro de Polonia que mediara con el papa con la esperanza de convertir a Lituania al cristianismo, pero el resultado fue negativo, y Polonia tomó de Lituania en 1349 el área de Halych y algunas tierras rutenas más al norte. La situación de Lituania mejoró a partir de 1350, cuando Algirdas formó una alianza con el Principado de Tver . Halych fue cedida por Lituania, lo que trajo la paz con Polonia en 1352. Asegurados por esas alianzas, Algirdas y Kęstutis se embarcaron en la implementación de políticas para expandir aún más los territorios de Lituania. [43]

Briansk fue tomada en 1359, y en 1362, Algirdas capturó Kiev después de derrotar a los mongoles en la Batalla de las Aguas Azules . [39] [40] [43] Volinia , Podolia y la orilla izquierda de Ucrania también fueron incorporadas. Kęstutis luchó heroicamente por la supervivencia de los lituanos étnicos al intentar repeler unas treinta incursiones de los Caballeros Teutónicos y sus combatientes invitados europeos. [7] Kęstutis también atacó las posesiones teutónicas en Prusia en numerosas ocasiones, pero los Caballeros tomaron Kaunas en 1362. [44] La disputa con Polonia se renovó y se resolvió con la paz de 1366, cuando Lituania entregó una parte de Volinia, incluido Volodymyr . En 1367 también se firmó la paz con los caballeros de Livonia. En 1368, 1370 y 1372, Algirdas invadió el Gran Ducado de Moscú y en cada ocasión se acercó a la propia Moscú . Tras el último intento se firmó una paz "eterna" (el Tratado de Lyubutsk ), que Lituania necesitaba con urgencia debido a su participación en duros combates con los caballeros de nuevo entre 1373 y 1377. [44]

Los dos hermanos y los demás descendientes de Gediminas dejaron muchos hijos ambiciosos con territorio heredado. Su rivalidad debilitó al país frente a la expansión teutónica y al nuevo Gran Ducado de Moscú, fortalecido por la victoria de 1380 sobre la Horda de Oro en la batalla de Kulikovo y con la intención de unificar todas las tierras de la Rus bajo su dominio. [7]

Algirdas murió en 1377 y su hijo Jogaila se convirtió en gran duque mientras Kęstutis aún vivía. La presión teutónica estaba en su apogeo y Jogaila se inclinó a dejar de defender Samogitia para concentrarse en preservar el imperio ruteno de Lituania. Los Caballeros explotaron las diferencias entre Jogaila y Kęstutis y consiguieron un armisticio separado con el duque mayor en 1379. Jogaila luego hizo propuestas a la Orden Teutónica y concluyó el Tratado secreto de Dovydiškės con ellos en 1380, contrario a los principios e intereses de Kęstutis. Kęstutis sintió que ya no podía apoyar a su sobrino y en 1381, cuando las fuerzas de Jogaila estaban preocupadas por sofocar una rebelión en Polotsk , entró en Vilna para derrocar a Jogaila del trono. Se produjo una guerra civil lituana . Las dos incursiones de Kęstutis contra las posesiones teutónicas en 1382 recuperaron la tradición de sus hazañas pasadas, pero Jogaila recuperó Vilna durante la ausencia de su tío. Kęstutis fue capturado y murió bajo la custodia de Jogaila. El hijo de Kęstutis, Vytautas , escapó. [7] [40] [45]

En 1382, Jogaila aceptó el Tratado de Dubysa con la Orden, lo que indicaba su debilidad. Una tregua de cuatro años estipulaba la conversión de Jogaila al catolicismo y la cesión de la mitad de Samogitia a los Caballeros Teutónicos. Vitautas fue a Prusia en busca del apoyo de los Caballeros para sus reivindicaciones, incluido el Ducado de Trakai , que consideraba heredado de su padre. La negativa de Jogaila a someterse a las demandas de su primo y de los Caballeros resultó en la invasión conjunta de Lituania en 1383. Vitautas, sin embargo, al no haber logrado obtener todo el ducado, estableció contactos con el gran duque. Tras recibir de él las áreas de Grodno , Podlasie y Brest , Vitautas cambió de bando en 1384 y destruyó las fortalezas fronterizas que le había confiado la Orden. En 1384, los dos duques lituanos, actuando juntos, emprendieron una exitosa expedición contra las tierras gobernadas por la Orden. [7]

En ese momento, en aras de su supervivencia a largo plazo, el Gran Ducado de Lituania había iniciado los procesos que condujeron a su inminente aceptación de la cristiandad europea . [7] Los Caballeros Teutónicos apuntaban a una unificación territorial de sus ramas prusiana y livonia conquistando Samogitia y toda Lituania propiamente dicha, tras la anterior subordinación de las tribus prusianas y letonas. Para dominar a los pueblos bálticos y eslavos vecinos y expandirse hasta convertirse en una gran potencia báltica, los Caballeros utilizaron combatientes voluntarios alemanes y de otros países. Desataron 96 ataques en Lituania durante el período 1345-1382, contra los cuales los lituanos pudieron responder con solo 42 incursiones retributivas propias. El imperio ruteno de Lituania en el este también se vio amenazado tanto por las ambiciones de unificación de la Rus de Moscú como por las actividades centrífugas llevadas a cabo por los gobernantes de algunas de las provincias más distantes. [46]

.jpg/440px-VILLINUS_OLD_TOWN_LITHUANIA_SEP_2013_(9851576794).jpg)

El Estado lituano de finales del siglo XIV era fundamentalmente binacional, lituano y ruteno (en territorios que corresponden a las actuales Bielorrusia y Ucrania). De su superficie total de 800.000 kilómetros cuadrados, el 10% estaba formado por la etnia lituana, probablemente poblada por no más de 300.000 habitantes. Lituania dependía para su supervivencia de los recursos humanos y materiales de las tierras rutenas. [47]

La sociedad lituana, cada vez más diferenciada, estaba liderada por príncipes de las dinastías Gediminid y Rurik y los descendientes de antiguos jefes kunigas de familias como los Giedraitis , Olshanski y Svirski. Por debajo de ellos en rango estaba la nobleza lituana regular (o boyardos ), que en Lituania propiamente dicha estaban estrictamente sujetos a los príncipes y generalmente vivían en modestas granjas familiares, cada una atendida por unos pocos súbditos feudales o, más a menudo, trabajadores esclavos si el boyardo podía permitírselos. Por sus servicios militares y administrativos, los boyardos lituanos eran compensados con exenciones de contribuciones públicas, pagos y concesiones de tierras rutenas. La mayoría de los trabajadores rurales ordinarios eran libres. Estaban obligados a proporcionar artesanías y numerosas contribuciones y servicios; por no pagar este tipo de deudas (o por otros delitos), uno podía ser obligado a la esclavitud. [7] [48]

Los príncipes rutenos eran ortodoxos, y muchos príncipes lituanos también se convirtieron a la ortodoxia oriental , incluso algunos que residían en Lituania propiamente dicha, o al menos sus esposas. Las iglesias y monasterios rutenos de mampostería albergaban monjes eruditos, sus escritos (incluidas traducciones de los Evangelios como los Evangelios de Ostromir ) y colecciones de arte religioso. Un barrio ruteno poblado por súbditos ortodoxos de Lituania, y que contenía su iglesia, existió en Vilna desde el siglo XIV. La cancillería de los grandes duques en Vilna estaba atendida por clérigos ortodoxos, quienes, formados en el idioma eslavo eclesiástico , desarrollaron el eslavo de cancillería , un idioma escrito ruteno útil para el mantenimiento de registros oficiales. Los documentos más importantes del Gran Ducado, la Métrica lituana , las Crónicas lituanas y los Estatutos de Lituania , estaban todos escritos en ese idioma. [49]

Se invitó a colonos alemanes, judíos y armenios a vivir en Lituania; los dos últimos grupos establecieron sus propias comunidades confesionales directamente bajo el mando de los duques gobernantes. Los tártaros y los caraítas de Crimea fueron asignados como soldados para la guardia personal de los duques. [49]

Las ciudades se desarrollaron en un grado mucho menor que en las cercanas Prusia o Livonia . Fuera de Rutenia, las únicas ciudades eran Vilna (capital de Gediminas desde 1323), la antigua capital de Trakai y Kaunas . [7] [9] [29] Kernavė y Kreva eran los otros antiguos centros políticos. [36] Vilna en el siglo XIV era un importante centro social, cultural y comercial. Vinculaba económicamente a Europa central y oriental con el área del Báltico . Los comerciantes de Vilna disfrutaban de privilegios que les permitían comerciar en la mayor parte de los territorios del estado lituano. De los comerciantes rutenos, polacos y alemanes que pasaban por allí (muchos de Riga), muchos se establecieron en Vilna y algunos construyeron residencias de mampostería. La ciudad estaba gobernada por un gobernador nombrado por el gran duque y su sistema de fortificaciones incluía tres castillos. Las monedas extranjeras y la moneda lituana (del siglo XIII) se usaban ampliamente. [7] [50]

El Estado lituano mantenía una estructura de poder patrimonial . El gobierno gedimínido era hereditario, pero el gobernante elegía al hijo que consideraba más capaz para ser su sucesor. Existían consejos, pero sólo podían asesorar al duque. El enorme Estado estaba dividido en una jerarquía de unidades territoriales administradas por funcionarios designados que también tenían poderes en asuntos judiciales y militares. [7]

Los lituanos hablaban varios dialectos aukštaitios y samogitios (del Báltico occidental), pero las peculiaridades tribales estaban desapareciendo y el uso creciente del nombre Lietuva era un testimonio del creciente sentido de identidad independiente de los lituanos. El sistema feudal lituano en formación conservó muchos aspectos de la organización social anterior, como la estructura familiar de clanes, el campesinado libre y cierta esclavitud. La tierra pertenecía ahora al gobernante y a la nobleza. Se utilizaron modelos importados principalmente de Rutenia para la organización del estado y su estructura de poder. [51]

Tras el establecimiento del cristianismo occidental a finales del siglo XIV, la práctica de ceremonias paganas de cremación disminuyó notablemente. [52]

A medida que el poder de los duques-caudillos lituanos se expandía hacia el sur y el este, los cultos rutenos eslavos orientales ejercieron influencia sobre la clase dirigente lituana. [53] Trajeron consigo la liturgia eslava eclesiástica de la religión cristiana ortodoxa oriental , una lengua escrita (eslavo de la cancillería) que se desarrolló para satisfacer las necesidades de producción de documentos de la corte lituana durante unos pocos siglos, y un sistema de leyes. De este modo, los rutenos transformaron Vilna en un importante centro de la civilización de la Rus de Kiev. [53] Cuando Jogaila aceptó el catolicismo en la Unión de Krewo en 1385, muchas instituciones de su reino y miembros de su familia ya habían sido asimilados en gran medida al cristianismo ortodoxo y se rusificaron (en parte como resultado de la política deliberada de la casa gobernante gedimínida). [53] [54]

La influencia y los contactos católicos, incluidos los derivados de los colonos, comerciantes y misioneros alemanes de Riga, [55] habían ido aumentando durante algún tiempo en la región noroeste del imperio, conocida como Lituania propiamente dicha. Las órdenes de los frailes franciscanos y dominicos existían en Vilna desde la época de Gediminas . Kęstutis en 1349 y Algirdas en 1358 negociaron la cristianización con el papa, el Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico y el rey polaco. La cristianización de Lituania involucró, por tanto, aspectos tanto católicos como ortodoxos. La conversión por la fuerza, tal como la practicaban los Caballeros Teutónicos, había sido en realidad un impedimento que retrasó el progreso del cristianismo occidental en el gran ducado. [7]

Jogaila , gran duque desde 1377, era todavía pagano al comienzo de su reinado. En 1386, aceptó la oferta de la corona polaca de los principales nobles polacos, que estaban ansiosos por aprovechar la expansión de Lituania, si se convertía al catolicismo y se casaba con la reina (no reina) Eduviges, de 13 años de edad . [56] Para el futuro cercano, Polonia le dio a Lituania un aliado valioso contra las crecientes amenazas de los Caballeros Teutónicos y el Gran Ducado de Moscú . Lituania, en la que los rutenos superaban en número a los lituanos étnicos en varias veces, podía aliarse con el Gran Ducado de Moscú o con Polonia. También se negoció un acuerdo ruso con Dmitri Donskoy en 1383-1384, pero Moscú estaba demasiado lejos para poder ayudar con los problemas planteados por las órdenes teutónicas y presentaba una dificultad como centro que competía por la lealtad de los rutenos lituanos ortodoxos. [7] [54]

Jogaila fue bautizado, recibió el nombre bautismal de Władysław, se casó con la reina Jadwiga y fue coronado rey de Polonia en febrero de 1386. [57] [58]

El bautismo y la coronación de Jogaila fueron seguidos por la cristianización oficial y final de Lituania . [59] En el otoño de 1386, el rey regresó a Lituania y en la primavera y el verano siguientes participó en ceremonias de conversión masiva y bautismo para la población en general. [60] El establecimiento de un obispado en Vilna en 1387 fue acompañado por la extraordinariamente generosa donación de Jogaila de tierras y campesinos a la Iglesia y la exención de las obligaciones y el control del estado. Esto transformó instantáneamente a la Iglesia lituana en la institución más poderosa del país (y los futuros grandes duques prodigaron aún más riqueza en ella). Los boyardos lituanos que aceptaron el bautismo fueron recompensados con un privilegio más limitado que mejoró sus derechos legales. [61] [62] A los habitantes de Vilna se les concedió el autogobierno. La Iglesia prosiguió con su misión civilizadora de alfabetización y educación, y los estados del reino comenzaron a surgir con sus propias identidades separadas. [52]

Las órdenes de Jogaila para que su corte y sus seguidores se convirtieran al catolicismo tenían como objetivo privar a los Caballeros Teutónicos de la justificación para su práctica de conversión forzada mediante ataques militares. En 1403, el Papa prohibió a la Orden llevar a cabo guerras contra Lituania, y su amenaza a la existencia de Lituania (que había perdurado durante dos siglos) fue efectivamente neutralizada. A corto plazo, Jogaila necesitaba el apoyo polaco en su lucha con su primo Vytautas. [52] [54]

La Guerra Civil Lituana de 1389-1392 involucró a los Caballeros Teutónicos, los polacos y las facciones rivales leales a Jogaila y Vytautas en Lituania. En medio de una guerra despiadada, el gran ducado fue devastado y amenazado de colapso. Jogaila decidió que la salida era hacer las paces y reconocer los derechos de Vytautas, cuyo objetivo original, ahora en gran medida cumplido, era recuperar las tierras que consideraba su herencia. Después de las negociaciones, Vytautas terminó ganando mucho más que eso; a partir de 1392 se convirtió prácticamente en el gobernante de Lituania, un autodenominado "Duque de Lituania", en virtud de un compromiso con Jogaila conocido como el Acuerdo de Ostrów . Técnicamente, era simplemente el regente de Jogaila con autoridad extendida. Jogaila se dio cuenta de que cooperar con su capaz primo era preferible a intentar gobernar (y defender) Lituania directamente desde Cracovia. [62] [63]

Vitautas se había sentido frustrado por los acuerdos polacos de Jogaila y rechazó la perspectiva de la subordinación de Lituania a Polonia. [64] Bajo Vitautas, se produjo una considerable centralización del estado, y la nobleza lituana catolicizada se hizo cada vez más prominente en la política estatal. [65] Los esfuerzos de centralización comenzaron en 1393-1395, cuando Vitautas se apropió de sus provincias de varios duques regionales poderosos en Rutenia. [66] Varias invasiones de Lituania por parte de los Caballeros Teutónicos ocurrieron entre 1392 y 1394, pero fueron repelidas con la ayuda de las fuerzas polacas. Posteriormente, los Caballeros abandonaron su objetivo de conquistar Lituania propiamente dicha y se concentraron en subyugar y mantener Samogitia. En 1395, Wenceslao IV de Bohemia , el superior formal de la Orden, prohibió a los Caballeros atacar Lituania. [67]

En 1395, Vitautas conquistó Smolensk y en 1397 dirigió una expedición victoriosa contra una rama de la Horda de Oro. Ahora sentía que podía permitirse la independencia de Polonia y en 1398 se negó a pagar el tributo debido a la reina Eduviges. En busca de libertad para perseguir sus objetivos internos y rutenos, Vitautas tuvo que conceder a la Orden Teutónica una gran parte de Samogitia en el Tratado de Salynas de 1398. La conquista de Samogitia por la Orden Teutónica mejoró en gran medida su posición militar, así como la de los Hermanos de la Espada de Livonia asociados . Vitautas pronto persiguió los intentos de recuperar el territorio, una empresa para la que necesitaba la ayuda del rey polaco. [67] [68]

Durante el reinado de Vitautas, Lituania alcanzó la cima de su expansión territorial, pero sus ambiciosos planes de subyugar a toda Rutenia se vieron frustrados por su desastrosa derrota en 1399 en la Batalla del río Vorskla , infligida por la Horda de Oro. Vitautas sobrevivió huyendo del campo de batalla con una pequeña unidad y se dio cuenta de la necesidad de una alianza permanente con Polonia. [67] [68]

La Unión de Krewo original de 1385 fue renovada y redefinida en varias ocasiones, pero cada vez con poca claridad debido a los intereses en pugna de Polonia y Lituania. Se acordaron nuevos acuerdos en las " uniones " de Vilna (1401) , Horodło (1413) , Grodno (1432) y Vilna (1499) . [69] En la Unión de Vilna, Jogaila concedió a Vitautas un gobierno vitalicio sobre el gran ducado. A cambio, Jogaila preservó su supremacía formal, y Vitautas prometió "permanecer fielmente con la Corona y el Rey". La guerra con la Orden se reanudó. En 1403, el papa Bonifacio IX prohibió a los Caballeros atacar Lituania, pero ese mismo año Lituania tuvo que aceptar la Paz de Raciąż , que establecía las mismas condiciones que en el Tratado de Salynas. [70]

Asegurado en el oeste, Vitautas volvió a centrar su atención en el este. Las campañas libradas entre 1401 y 1408 involucraron Smolensk, Pskov , Moscú y Veliki Nóvgorod . Smolensk fue retenida, Pskov y Veliki Nóvgorod terminaron siendo dependencias lituanas, y en 1408 se acordó una división territorial duradera entre el Gran Ducado y Moscú en el tratado de Ugra , donde una gran batalla no llegó a materializarse. [70] [71]

La guerra decisiva contra los Caballeros Teutónicos (la Gran Guerra ) fue precedida en 1409 por un levantamiento de Samogotia apoyado por Vitautas. Finalmente, la alianza lituano-polaca logró derrotar a los Caballeros en la Batalla de Grunwald el 15 de julio de 1410, pero los ejércitos aliados no lograron tomar Marienburgo , la fortaleza-capital de los Caballeros. Sin embargo, la victoria total sin precedentes en el campo de batalla contra los Caballeros eliminó permanentemente la amenaza que habían representado para la existencia de Lituania durante siglos. La Paz de Thorn (1411) permitió a Lituania recuperar Samogotia, pero solo hasta la muerte de Jogaila y Vitautas, y los Caballeros tuvieron que pagar una gran reparación monetaria. [72] [73] [74]

La Unión de Horodło (1413) incorporó a Lituania a Polonia de nuevo, pero sólo como una formalidad. En términos prácticos, Lituania se convirtió en un socio igualitario de Polonia, porque cada país estaba obligado a elegir a su futuro gobernante sólo con el consentimiento del otro, y se declaró que la Unión continuaría incluso bajo una nueva dinastía. Los boyardos católicos lituanos iban a disfrutar de los mismos privilegios que los nobles polacos ( szlachta ). 47 clanes lituanos superiores se unieron a 47 familias nobles polacas para iniciar una futura hermandad y facilitar la esperada unidad plena. Se establecieron dos divisiones administrativas (Vilnius y Trakai) en Lituania, siguiendo el modelo polaco existente. [75] [76]

Vitautas practicaba la tolerancia religiosa y sus grandiosos planes también incluían intentos de influir en la Iglesia Ortodoxa Oriental, a la que quería utilizar como herramienta para controlar Moscú y otras partes de Rutenia. En 1416, elevó a Gregorio Tsamblak como su patriarca ortodoxo elegido para toda Rutenia (el obispo metropolitano ortodoxo establecido permaneció en Vilna hasta fines del siglo XVIII). [66] [77] Estos esfuerzos también tenían como objetivo servir al objetivo de la unificación global de las iglesias oriental y occidental. Tsamblak encabezó una delegación ortodoxa al Concilio de Constanza en 1418. [78] Sin embargo, el sínodo ortodoxo no reconoció a Tsamblak. [77] El gran duque también estableció nuevos obispados católicos en Samogitia (1417) [78] y en la Rutenia lituana ( Lutsk y Kiev). [77]

La Guerra de Gollub con los Caballeros Teutónicos siguió y en 1422, en el Tratado de Melno , el gran ducado recuperó permanentemente Samogitia, lo que puso fin a su participación en las guerras con la Orden. [79] Las políticas cambiantes de Vitautas y su renuencia a perseguir a la Orden hicieron posible la supervivencia de la Prusia Oriental alemana durante los siglos siguientes. [80] Samogitia fue la última región de Europa en ser cristianizada (a partir de 1413). [78] [81] Más tarde, Lituania y Polonia llevaron a cabo diferentes políticas exteriores, acompañadas de conflictos por Podolia y Volinia , los territorios del gran ducado en el sureste. [82]

Los mayores éxitos y reconocimientos de Vitautas se produjeron al final de su vida, cuando el Kanato de Crimea y los tártaros del Volga quedaron bajo su influencia. El príncipe Vasili I de Moscú murió en 1425, y Vitautas administró entonces el Gran Ducado de Moscú junto con su hija, la viuda de Vasili, Sofía de Lituania . En 1426-1428 Vitautas recorrió triunfalmente los confines orientales de su imperio y recaudó enormes tributos de los príncipes locales. [80] Pskov y Veliki Novgorod fueron incorporadas al gran ducado en 1426 y 1428. [78] En el Congreso de Lutsk en 1429, Vitautas negoció la cuestión de su coronación como rey de Lituania con el emperador del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico Segismundo y Jogaila. Esa ambición estuvo cerca de cumplirse, pero al final se vio frustrada por intrigas de último momento y la muerte de Vitautas. El culto y la leyenda de Vitautas se originaron durante sus últimos años y han continuado hasta hoy. [80]

El vínculo dinástico con Polonia dio lugar a lazos religiosos , políticos y culturales y al aumento de la influencia occidental entre la nobleza nativa lituana y, en menor medida, entre los boyardos rutenos del este , súbditos lituanos. [64] Los católicos recibieron un trato preferencial y acceso a los cargos debido a las políticas de Vitautas, pronunciadas oficialmente en 1413 en la Unión de Horodło, y más aún de sus sucesores, destinadas a afirmar el gobierno de la élite católica lituana sobre los territorios rutenos. [65] Tales políticas aumentaron la presión sobre la nobleza para convertirse al catolicismo. La Lituania étnica propiamente dicha constituía el 10% del área y el 20% de la población del Gran Ducado. De las provincias rutenas, Volinia estaba más estrechamente integrada con la Lituania propiamente dicha. Las ramas de la familia Gediminid , así como otros clanes de magnates lituanos y rutenos , finalmente se establecieron allí. [66]

Durante este período, se fue formando un estrato de terratenientes ricos, importantes también como fuerza militar, [83] acompañado por la clase emergente de siervos feudales asignados a ellos. [66] El Gran Ducado de Lituania se conservó por el momento en gran parte como un estado separado con instituciones separadas, pero se hicieron esfuerzos, originados principalmente en Polonia, para acercar las élites y los sistemas polacos y lituanos. [75] [76] A Vilnius y otras ciudades se les concedió el sistema de leyes alemán ( derechos de Magdeburgo ). La artesanía y el comercio se estaban desarrollando rápidamente. Bajo Vytautas funcionó una red de cancillerías, se establecieron las primeras escuelas y se escribieron anales . Aprovechando las oportunidades históricas, el gran gobernante abrió Lituania a la influencia de la cultura europea e integró su país con el cristianismo occidental europeo . [78] [83]

La dinastía Jagellónica fundada por Jogaila (miembro de una de las ramas de los Gediminidas) gobernó Polonia y Lituania continuamente entre 1386 y 1572.

Tras la muerte de Vitautas en 1430, se produjo otra guerra civil y Lituania fue gobernada por sucesores rivales. Posteriormente, la nobleza lituana rompió técnicamente en dos ocasiones la unión entre Polonia y Lituania al elegir unilateralmente grandes duques de la dinastía Jagellónica . En 1440, los grandes señores lituanos elevaron a Casimiro , el segundo hijo de Jogaila, al gobierno del gran ducado. Esta cuestión se resolvió con la elección de Casimiro como rey por los polacos en 1446. En 1492, el nieto de Jogaila, Juan Alberto, se convirtió en rey de Polonia, mientras que su nieto Alejandro se convirtió en gran duque de Lituania. En 1501, Alejandro sucedió a Juan como rey de Polonia, lo que resolvió la dificultad de la misma manera que antes. [68] Una conexión duradera entre los dos estados fue beneficiosa para los polacos, lituanos y rutenos, católicos y ortodoxos, así como para los propios gobernantes jagellónicos, cuyos derechos de sucesión hereditaria en Lituania prácticamente garantizaban su elección como reyes de acuerdo con las costumbres que rodeaban las elecciones reales en Polonia . [69]

En el frente teutónico, Polonia continuó su lucha, que en 1466 condujo a la Paz de Thorn y a la recuperación de gran parte de las pérdidas territoriales de la dinastía Piast . En 1525 se estableció un ducado secular de Prusia, cuya presencia tendría un gran impacto en el futuro tanto de Lituania como de Polonia. [84]

El kanato tártaro de Crimea reconoció la soberanía del Imperio otomano desde 1475. En busca de esclavos y botín, los tártaros saquearon vastas porciones del gran ducado de Lituania, quemando Kiev en 1482 y acercándose a Vilna en 1505. Su actividad resultó en la pérdida de Lituania de sus territorios distantes en las costas del Mar Negro en las décadas de 1480 y 1490. Los dos últimos reyes Jagellón fueron Segismundo I y Segismundo II Augusto , durante cuyo reinado la intensidad de las incursiones tártaras disminuyó debido a la aparición de la casta militar de los cosacos en los territorios del sureste y al creciente poder del Gran Ducado de Moscú . [85]

_by_Martynas_Mažvydas,_published_in_Königsberg,_1547_(cropped).jpg/440px-CATECHISMVSA_PRAsty_Szadei_(in_Lithuanian_language)_by_Martynas_Mažvydas,_published_in_Königsberg,_1547_(cropped).jpg)

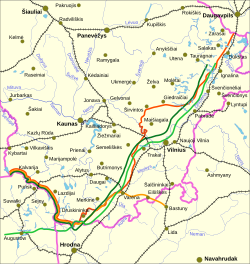

Lituania necesitaba una alianza estrecha con Polonia cuando, a finales del siglo XV, el cada vez más agresivo Gran Ducado de Moscú amenazó a algunos de los principados de la Rus lituana con el objetivo de "recuperar" las tierras que antes estaban bajo el gobierno ortodoxo. En 1492, Iván III de Rusia desató lo que resultó ser una serie de guerras moscovitas-lituanas y guerras livonias . [86]

En 1492, la frontera del territorio ruteno oriental de Lituania, poco controlado, se extendía a menos de cien millas de Moscú . Pero como resultado de la guerra, un tercio de la superficie terrestre del gran ducado fue cedida al estado ruso en 1503. Luego, la pérdida de Smolensk en julio de 1514 fue particularmente desastrosa, aunque fue seguida por la exitosa batalla de Orsha en septiembre, ya que los intereses polacos reconocían a regañadientes la necesidad de su propia participación en la defensa de Lituania. La paz de 1537 dejó a Gomel como el límite oriental del gran ducado. [86]

En el norte, la Guerra de Livonia tuvo lugar por la región estratégica y económicamente crucial de Livonia, el territorio tradicional de la Orden de Livonia. La Confederación de Livonia formó una alianza con el lado polaco-lituano en 1557 con el Tratado de Pozvol . Deseada tanto por Lituania como por Polonia, Livonia fue entonces incorporada a la Corona polaca por Segismundo II. Estos acontecimientos hicieron que Iván el Terrible de Rusia lanzara ataques en Livonia a partir de 1558, y más tarde en Lituania. La fortaleza del gran ducado de Pólatsk cayó en 1563. A esto le siguió una victoria lituana en la batalla de Ula en 1564, pero no una recuperación de Pólatsk. Las ocupaciones rusas, suecas y polaco-lituanas subdividieron Livonia. [87]

_(2).jpg/440px-Statut_Vialikaha_Kniastva_Litoŭskaha._Статут_Вялікага_Княства_Літоўскага_(1588)_(2).jpg)

El estamento gobernante polaco había tenido como objetivo la incorporación del Gran Ducado de Lituania a Polonia desde antes de la Unión de Krewo. [88] Los lituanos pudieron defenderse de esta amenaza en los siglos XIV y XV, pero la dinámica del poder cambió en el siglo XVI. En 1508, el Sejm polaco votó por primera vez la financiación de la defensa de Lituania contra Moscovia, y se desplegó un ejército. El movimiento verdugo de la nobleza polaca exigía la incorporación total del Gran Ducado debido a su creciente dependencia del apoyo de la Corona polaca contra las invasiones de Moscú. Este problema solo se agudizó durante el reinado de Segismundo II Augusto , el último rey jagellónico y gran duque de Lituania, que no tenía un heredero que heredara y continuara la unión personal entre Polonia y Lituania. La preservación del arreglo de poder polaco-lituano pareció requerir que el monarca forzara una solución decisiva durante su vida. La resistencia a una unión más estrecha y permanente provenía de las familias gobernantes de Lituania, cada vez más polonizadas en términos culturales, pero apegadas a la herencia lituana y a su gobierno patrimonial. [89] [90]

Sin embargo, en Lituania se había producido una evolución jurídica en los últimos tiempos. En el Privilegio de Vilna de 1563, Segismundo restauró los derechos políticos plenos a los boyardos ortodoxos del Gran Ducado , que habían estado restringidos hasta entonces por Vitautas y sus sucesores; a partir de entonces, todos los miembros de la nobleza eran oficialmente iguales. Se establecieron tribunales electivos en 1565-66, y el Segundo Estatuto Lituano de 1566 creó una jerarquía de cargos locales inspirada en el sistema polaco. La asamblea legislativa lituana asumió los mismos poderes formales que el Sejm polaco. [89] [90]

El Sejm polaco de enero de 1569, que deliberó en Lublin , contó con la presencia de los señores lituanos por insistencia de Segismundo. La mayoría abandonó la ciudad el 1 de marzo, descontentos con las propuestas de los polacos de establecer derechos para adquirir propiedades en Lituania y otras cuestiones. Segismundo reaccionó anunciando la incorporación de los voivodatos de Volinia y Podlasie del Gran Ducado a la Corona polaca. Pronto también se anexionaron los grandes voivodatos de Kiev y Bratslav . Los boyardos rutenos del antiguo Gran Ducado del sudeste aprobaron en su mayoría las transferencias territoriales, ya que significaba que se convertirían en miembros de la privilegiada nobleza polaca. Pero el rey también presionó a muchos diputados obstinados para que aceptaran compromisos importantes para el lado lituano. La presión, combinada con garantías recíprocas de los derechos de los nobles lituanos, dio como resultado la aprobación "voluntaria" de la Unión de Lublin el 1 de julio. El sistema político combinado sería gobernado por un Sejm común, pero se mantendrían las jerarquías separadas de los principales cargos estatales. Muchos en el establishment lituano consideraron esto objetable, pero al final fueron prudentes y aceptaron. Por el momento, Segismundo logró preservar el estado polaco-lituano como gran potencia. No se llevaron a cabo las reformas necesarias para proteger su éxito y supervivencia a largo plazo. [89] [90]

Desde el siglo XVI hasta mediados del siglo XVII, la cultura, las artes y la educación florecieron en Lituania, impulsadas por el Renacimiento y la Reforma protestante . Las ideas luteranas de la Reforma entraron en la Confederación Livona en la década de 1520, y el luteranismo pronto se convirtió en la religión predominante en las áreas urbanas de la región, mientras que Lituania siguió siendo católica. [91] [92]

Un influyente comerciante de libros fue el humanista y bibliófilo Francysk Skaryna (c. 1485-1540), que fue el padre fundador de las letras bielorrusas . Escribió en su lengua materna , el ruteno (eslavo de la cancillería), [93] como era típico de los literatos en la fase anterior del Renacimiento en el Gran Ducado de Lituania. Después de mediados del siglo XVI, el polaco predominó en las producciones literarias. [94] Muchos lituanos cultos regresaron de sus estudios en el extranjero para ayudar a construir la activa vida cultural que distinguió a la Lituania del siglo XVI, a veces denominada Renacimiento lituano (que no debe confundirse con el Renacimiento nacional lituano del siglo XIX).

En esta época se introdujo la arquitectura italiana en las ciudades lituanas y floreció la literatura lituana escrita en latín. También en esta época aparecieron los primeros textos impresos en lengua lituana y comenzó la formación de la lengua lituana escrita. El proceso fue dirigido por los eruditos lituanos Abraomas Kulvietis , Stanislovas Rapalionis , Martynas Mažvydas y Mikalojus Daukša .

Con la Unión de Lublin de 1569, Polonia y Lituania formaron un nuevo estado conocido como la República de Ambas Naciones, pero comúnmente conocido como Polonia-Lituania o Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania . La Mancomunidad, que oficialmente consistía en la Corona del Reino de Polonia y el Gran Ducado de Lituania , estaba gobernada por la nobleza polaca y lituana, junto con reyes elegidos por la nobleza . La Unión fue diseñada para tener una política exterior, aduanas y moneda comunes. Se mantuvieron ejércitos polacos y lituanos separados, pero se establecieron oficinas centrales y ministeriales paralelas de acuerdo con una práctica desarrollada por la Corona. [90] El Tribunal Lituano , un tribunal superior para los asuntos de la nobleza, fue creado en 1581. [95]

Tras la muerte de Segismundo II Augusto en 1572, se eligió un monarca conjunto polaco-lituano, tal como se acordó en la Unión de Lublin . Según el tratado, el título de «Gran Duque de Lituania» lo recibiría un monarca elegido conjuntamente en el sejm electoral en el momento de su ascenso al trono, perdiendo así su anterior significado institucional. Sin embargo, el tratado garantizaba que la institución y el título de «Gran Duque de Lituania» se conservarían. [96] [97]

El 20 de abril de 1576 se celebró en Grodno el congreso de los nobles del Gran Ducado de Lituania , que adoptó una Asamblea Universal . Fue firmada por los nobles lituanos participantes, quienes anunciaron que si los delegados del Gran Ducado de Lituania sentían presión de los polacos en el sejm electoral , los lituanos no estarían obligados por un juramento de la Unión de Lublin y tendrían el derecho de elegir un monarca separado. [98] El 29 de mayo de 1580 se celebró una ceremonia en la catedral de Vilna durante la cual el obispo Merkelis Giedraitis entregó a Esteban Báthory (rey de Polonia desde el 1 de mayo de 1576) una espada lujosamente decorada y un gorro adornado con perlas (ambos fueron santificados por el propio papa Gregorio XIII ). Tal ceremonia manifestaba la soberanía del Gran Ducado de Lituania y tenía el significado de la elevación del nuevo Gran Duque de Lituania , ignorando así las estipulaciones de la Unión de Lublin. [99] [100]

El idioma lituano cayó en desuso en los círculos de la gran corte ducal en la segunda mitad del siglo XV a favor del polaco. [101] Un siglo después, el polaco era de uso común incluso entre la nobleza lituana común. [101] Después de la Unión de Lublin, la polonización afectó cada vez más a todos los aspectos de la vida pública lituana, pero el proceso tardó más de un siglo en completarse. Los Estatutos de Lituania de 1588 todavía se redactaban en el idioma eslavo de la cancillería rutena, al igual que las codificaciones legales anteriores. [102] Desde aproximadamente 1700, el polaco se utilizó en los documentos oficiales del Gran Ducado como reemplazo del uso del ruteno y el latín . [103] [104] La nobleza lituana se polonizó lingüística y culturalmente, al tiempo que conservaba un sentido de identidad lituana. [105] El proceso de integración de la nobleza de la Mancomunidad no fue considerado como una polonización en el sentido de la nacionalidad moderna, sino más bien como una participación en la corriente cultural-ideológica del sarmatismo , erróneamente entendida como implicando también una ascendencia común ( sármata ) de todos los miembros de la clase noble. [104] La lengua lituana sobrevivió, sin embargo, a pesar de las invasiones de las lenguas rutena, polaca, rusa , bielorrusa y alemana , como lengua vernácula campesina, y desde 1547 en el uso religioso escrito. [106]

El oeste de Lituania desempeñó un papel importante en la preservación de la lengua lituana y su cultura. En Samogitia, muchos nobles nunca dejaron de hablar lituano de forma nativa. El noreste de Prusia Oriental, a veces denominada Lituania Menor , estaba poblada principalmente por lituanos [107] y predominantemente luteranos . Los luteranos promovieron la publicación de libros religiosos en idiomas locales, por lo que el Catecismo de Martynas Mažvydas se imprimió en 1547 en Königsberg , en Prusia Oriental . [108]

_(2).jpg/440px-Kryštap_Radzivił._Крыштап_Радзівіл_(W._Delff,_1639)_(2).jpg)

La población predominantemente eslava oriental del Gran Ducado era mayoritariamente ortodoxa oriental , y gran parte de la nobleza del estado lituano también siguió siendo ortodoxa. A diferencia de la gente común del reino lituano, aproximadamente en la época de la Unión de Lublin en 1569, grandes porciones de la nobleza se convirtieron al cristianismo occidental . Después del movimiento de la Reforma protestante , muchas familias nobles se convirtieron al calvinismo en las décadas de 1550 y 1560, y típicamente una generación después, conformándose con las tendencias de la Contrarreforma en la Mancomunidad, al catolicismo romano . [109] La presencia protestante y ortodoxa debe haber sido muy fuerte, porque según una fuente indudablemente exagerada de principios del siglo XVII, "apenas uno de cada mil seguía siendo católico" en Lituania en ese momento. [110] [b] En la Mancomunidad temprana, la tolerancia religiosa era la norma y fue promulgada oficialmente por la Confederación de Varsovia en 1573. [111]

En 1750, los católicos nominales comprendían aproximadamente el 80% de la población de la Mancomunidad, la gran mayoría de la ciudadanía noble y toda la legislatura. En el este, también estaban los seguidores de la Iglesia Ortodoxa Oriental. Sin embargo, los católicos en el propio Gran Ducado estaban divididos. Menos de la mitad eran de la Iglesia latina con una fuerte lealtad a Roma, adorando según el rito romano . Los demás (en su mayoría rutenos no nobles) seguían el rito bizantino . Eran los llamados uniatos , cuya iglesia se estableció en la Unión de Brest en 1596, y reconocían solo la obediencia nominal a Roma. Al principio, la ventaja fue para la Iglesia católica que avanzaba y rechazó a una Iglesia Ortodoxa Oriental que retrocedía. Sin embargo, después de la primera partición de la Mancomunidad en 1772, los ortodoxos tenían el apoyo del gobierno y ganaron la partida. La Iglesia Ortodoxa Rusa prestó especial atención a los uniatos (que alguna vez habían sido ortodoxos) y trató de recuperarlos. La lucha fue política y espiritual, y se valió de misioneros, escuelas y la presión ejercida por poderosos nobles y terratenientes. En 1800, más de dos millones de uniatos se habían convertido a la Iglesia ortodoxa, y otros 1,6 millones en 1839. [112] [113]

A pesar de la Unión de Lublin y la integración de los dos países, Lituania continuó existiendo como un gran ducado dentro de la Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania durante más de dos siglos. Mantuvo leyes separadas, así como un ejército y un tesoro. [114] En el momento de la Unión de Lublin, el rey Segismundo II Augusto retiró Ucrania y otros territorios de Lituania y los incorporó directamente a la Corona polaca. El gran ducado quedó con la actual Bielorrusia y partes de la Rusia europea , además de las principales tierras étnicas lituanas. [115] A partir de 1573, los reyes de Polonia y los grandes duques de Lituania siempre fueron la misma persona y fueron elegidos por la nobleza, a la que se le otorgaron privilegios cada vez mayores en un sistema político aristocrático único conocido como la Libertad Dorada . Estos privilegios, especialmente el liberum veto , llevaron a la anarquía política y la eventual disolución del estado.

Dentro de la Mancomunidad, el Gran Ducado hizo importantes contribuciones a la vida económica, política y cultural europea: Europa occidental se abastecía de grano, a lo largo de la ruta marítima de Danzig a Ámsterdam ; la tolerancia religiosa y la democracia de la Mancomunidad temprana entre la clase noble gobernante eran únicas en Europa; Vilna era la única capital europea ubicada en la frontera de los mundos de la cristiandad occidental y oriental y allí se practicaban muchas religiones; para los judíos , [c] era la " Jerusalén del Norte" y la ciudad del Gaón de Vilna , su gran líder religioso; la Universidad de Vilna produjo numerosos ex alumnos ilustres y fue uno de los centros de aprendizaje más influyentes en su parte de Europa; la escuela de Vilna hizo contribuciones significativas a la arquitectura europea en estilo barroco ; la tradición legal lituana dio lugar a los códigos legales avanzados conocidos como los Estatutos de Lituania ; al final de la existencia de la Mancomunidad, la Constitución del 3 de mayo de 1791 fue la primera constitución escrita integral producida en Europa. Después de las particiones de Polonia , la escuela de Romanticismo de Vilnius produjo a dos grandes poetas: Adam Mickiewicz y Juliusz Słowacki . [117]

La Mancomunidad se vio muy debilitada por una serie de guerras, comenzando con el Levantamiento de Jmelnitski en Ucrania en 1648. [118] Durante las Guerras del Norte de 1655-1661, el territorio y la economía lituanos fueron devastados por el ejército sueco en una invasión conocida como el Diluvio , y Vilna fue quemada y saqueada por las fuerzas rusas. [108] Antes de que pudiera recuperarse por completo, Lituania fue devastada nuevamente durante la Gran Guerra del Norte de 1700-1721.

Además de la guerra, la Mancomunidad sufrió la Gran Guerra del Norte, el brote de peste y la hambruna (la peor causada por la Gran Helada de 1709 ). Estas calamidades resultaron en la pérdida de aproximadamente el 40% de los habitantes del país. Las potencias extranjeras, especialmente Rusia, se convirtieron en actores dominantes en la política interna de la Mancomunidad. Numerosas facciones entre la nobleza, controladas y manipuladas por los poderosos magnates de Polonia y Lituania , a menudo en conflicto entre sí, utilizaron su "Libertad Dorada" para evitar reformas. Algunos clanes lituanos, como los Radziwiłłs , se contaban entre los nobles más poderosos de la Mancomunidad.

La Constitución del 3 de mayo de 1791 fue la culminación del tardío proceso de reforma de la Mancomunidad. Intentó integrar a Lituania y Polonia de manera más estrecha, aunque la separación se mantuvo gracias a la Garantía Recíproca de Dos Naciones . Las particiones de la Mancomunidad polaco-lituana en 1772, 1793 y 1795 pusieron fin a su existencia y vieron al Gran Ducado de Lituania dividido entre el Imperio ruso , que se hizo cargo del 90% del territorio del ducado, y el Reino de Prusia . La Tercera Partición de 1795 tuvo lugar después del fracaso del Levantamiento de Kościuszko , la última guerra librada por polacos y lituanos para preservar su condición de Estado. Lituania dejó de existir como entidad distinta durante más de un siglo. [29]

Tras la división de la Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania , el Imperio ruso controlaba la mayor parte de Lituania, incluida Vilna , que formaba parte de la Gobernación de Vilna . En 1803, el zar Alejandro I revivió y actualizó la antigua academia jesuita como la Universidad Imperial de Vilna , la más grande del Imperio ruso. La universidad y el sistema educativo regional fueron dirigidos en nombre del zar por el príncipe Adam Czartoryski . [119] En los primeros años del siglo XIX, hubo indicios de que Lituania podría recibir algún reconocimiento independiente por parte del Imperio, sin embargo esto nunca sucedió.

En 1812, los lituanos recibieron con entusiasmo a la Grande Armée de Napoleón Bonaparte como libertadores, y muchos se unieron a la invasión francesa de Rusia . Después de la derrota y retirada del ejército francés, el zar Alejandro I decidió mantener abierta la Universidad de Vilna y el poeta de lengua polaca Adam Mickiewicz , residente en Vilna entre 1815 y 1824, pudo recibir su educación allí. [120] La parte suroeste de Lituania que fue tomada por Prusia en 1795, luego incorporada al Ducado de Varsovia (un estado títere francés que existió entre 1807 y 1815), se convirtió en parte del Reino de Polonia controlado por Rusia (" Polonia del Congreso ") en 1815. El resto de Lituania continuó siendo administrada como una provincia rusa.

Los polacos y lituanos se rebelaron contra el gobierno ruso dos veces, en 1830-31 (el Levantamiento de Noviembre ) y 1863-64 (el Levantamiento de Enero ), pero ambos intentos fracasaron y resultaron en una mayor represión por parte de las autoridades rusas. Después del Levantamiento de Noviembre, el zar Nicolás I comenzó un programa intensivo de rusificación y la Universidad de Vilna fue cerrada. [121] Lituania pasó a formar parte de una nueva región administrativa llamada Krai del Noroeste . [122] A pesar de la represión, la enseñanza del idioma polaco y la vida cultural pudieron continuar en gran medida en el antiguo Gran Ducado de Lituania hasta el fracaso del Levantamiento de Enero . [102] Los Estatutos de Lituania fueron anulados por el Imperio ruso recién en 1840, y la servidumbre fue abolida como parte de la reforma general de Emancipación de 1861 que se aplicó a todo el Imperio ruso. [123] La Iglesia Uniata, importante en la parte bielorrusa del antiguo Gran Ducado, fue incorporada a la Iglesia Ortodoxa en 1839. [124]

La poesía polaca de Adam Mickiewicz, que estaba emocionalmente ligado a la campiña lituana y a las leyendas medievales asociadas a ella, influyó en los fundamentos ideológicos del emergente movimiento nacional lituano. Simonas Daukantas , que estudió con Mickiewicz en la Universidad de Vilna, promovió un retorno a las tradiciones de Lituania anteriores a la Commonwealth y una renovación de la cultura local, basada en la lengua lituana . Con esas ideas en mente, escribió ya en 1822 una historia de Lituania en lituano (aunque todavía no se había publicado en ese momento). Teodor Narbutt escribió en polaco una voluminosa Historia antigua de la nación lituana (1835-1841), donde también expuso y amplió aún más el concepto de Lituania histórica, cuyos días de gloria habían terminado con la Unión de Lublin en 1569. Narbutt, invocando la erudición alemana, señaló la relación entre las lenguas lituana y sánscrita . Esto indicaba la proximidad del lituano a sus antiguas raíces indoeuropeas y más tarde proporcionaría el argumento de la "antigüedad" para los activistas asociados con el Renacimiento Nacional Lituano . A mediados del siglo XIX, la ideología básica del futuro movimiento nacionalista lituano se definió teniendo en mente la identidad lingüística; para establecer una identidad lituana moderna, era necesario romper con la dependencia tradicional de la cultura y la lengua polacas. [125]

Around the time of the January Uprising, there was a generation of Lithuanian leaders of the transitional period between a political movement bound with Poland and the modern Lithuanian nationalist movement based on language. Jakób Gieysztor, Konstanty Kalinowski and Antanas Mackevičius wanted to form alliances with the local peasants, who, empowered and given land, would presumably help defeat the Russian Empire, acting in their own self-interest. This created new dilemmas that had to do with languages used for such inter-class communication and later led to the concept of a nation as the "sum of speakers of a vernacular tongue."[126]

The failure of the January Uprising in 1864 made the connection with Poland seem outdated to many Lithuanians and at the same time led to the creation of a class of emancipated and often prosperous peasants who, unlike often Polonized urban residents, were effectively custodians of the Lithuanian language. Educational opportunities, now more widely available to young people of such common origins, were one of the crucial factors responsible for the Lithuanian national revival. As schools were being de-Polonized and Lithuanian university students sent to Saint Petersburg or Moscow rather than Warsaw, a cultural void resulted, and it was not being successfully filled by the attempted Russification policies.[127]

Russian nationalists regarded the territories of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania as an East Slavic realm that ought to be (and was being) "reunited" with Russia.[128] In the following decades however, a Lithuanian national movement emerged, composed of activists of different social backgrounds and persuasions, often primarily Polish-speaking, but united by their willingness to promote the Lithuanian culture and language as a strategy for building a modern nation.[127] The restoration of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania was no longer the objective of this movement, and the territorial ambitions of its leaders were limited to the lands they considered historically Lithuanian.[108]

In 1864, the Lithuanian language and the Latin alphabet were banned in junior schools. The prohibition on printing in the Lithuanian language reflected the Russian nationalist policy of "restoration" of the supposedly Russian beginnings of Lithuania. The tsarist authorities implemented a number of Russification policies, including a Lithuanian press ban and the closing of cultural and educational institutions. Those were resisted by Lithuanians, led by Bishop Motiejus Valančius, among others.[108] Lithuanians resisted by arranging printing abroad and smuggling of the books in from neighboring East Prussia.

Lithuanian was not considered a prestigious language. There were even expectations that the language would become extinct, as more and more territories in the east were slavicized, and more people used Polish or Russian in daily life. The only place where Lithuanian was considered more prestigious and worthy of books and studying was in East Prussia, sometimes referred to by Lithuanian nationalists as "Lithuania Minor." At the time, northeastern East Prussia was home to numerous ethnic Lithuanians, but even there Germanization pressure threatened their cultural identity.

The language revival spread into more affluent strata, beginning with the release of the Lithuanian newspapers Aušra and Varpas, then with the writing of poems and books in Lithuanian many of which glorified the historic Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

The two most prominent figures in the revival movement, Jonas Basanavičius and Vincas Kudirka, both originated from affluent Lithuanian peasantry and attended the Mariampol Gymnasium (secondary school) in the Suwałki Governorate. The school was a Polish educational center, Russified after the January Uprising, with Lithuanian language classes introduced at that time.[129]

Basanavičius studied medicine at the Moscow State University, where he developed international connections, published (in Polish) on Lithuanian history and graduated in 1879. From there he went to Bulgaria, and in 1882 moved to Prague. In Prague he met and became influenced by the Czech National Revival movement. In 1883, Basanavičius began working on a Lithuanian language review, which assumed the form of a newspaper named Aušra (The Dawn), published in Ragnit, Prussia, Germany (now Neman, Russia). Aušra was printed in Latin characters banned under Russian law, which mandated the Cyrillic alphabet for printing Lithuanian. It was smuggled to Lithuania, together with other Lithuanian publications and books printed in East Prussia. The paper (forty issues in total), building on the work of the earlier writers, sought to demonstrate continuities with the medieval Grand Duchy and lionize the Lithuanian people.[130]

.jpg/440px-Jonas_Basanavicius_(1851-1927).jpg)

Russian restrictions at Marijampolė secondary school were eased in 1872 and Kudirka learned Polish there. He went on to study at the University of Warsaw, where he was influenced by Polish socialists. In 1889, Kudirka returned to Lithuania and worked on incorporating the Lithuanian peasantry into mainstream politics as the main building block of a modern nation. In 1898, he wrote a poem inspired by the opening strophe of Mickiewicz's epic poem Pan Tadeusz: "Lithuania, my fatherland! You are like health." The poem became the national anthem of Lithuania, Tautiška giesmė: ("Lithuania, Our Homeland").[131]

As the revival grew, Russian policy became harsher. Attacks took place against Catholic churches while the ban forbidding the Lithuanian press continued. However, in the late 19th century, the language ban was lifted.[29] and some 2,500 books were published in the Lithuanian Latin alphabet. The majority of these were published in Tilsit, Kingdom of Prussia (now Russian Sovetsk, Kaliningrad Oblast), although some publications reached Lithuania from the United States. A largely standardized written language was achieved by 1900, based on historical and Aukštaitijan (highland) usages.[132] The letters -č-, -š- and -v- were taken from the modern (redesigned) Czech orthography, to avoid the Polish usage for corresponding sounds.[133][134] The widely accepted Lithuanian Grammar, by Jonas Jablonskis, appeared in 1901.[133]

Large numbers of Lithuanians had emigrated to the United States in 1867–1868 after a famine in Lithuania.[135] Between 1868 and 1914, approximately 635,000 people, almost 20 percent of the population, left Lithuania.[136] Lithuanian cities and towns were growing under the Russian rule, but the country remained underdeveloped by the European standards and job opportunities were limited; many Lithuanians left also for the industrial centers of the Russian Empire, such as Riga and Saint Petersburg. Many of Lithuania's cities were dominated by non-Lithuanian-speaking Jews and Poles.[108]

Lithuania's nationalist movement continued to grow. During the 1905 Russian Revolution, a large congress of Lithuanian representatives in Vilnius known as the Great Seimas of Vilnius demanded provincial autonomy for Lithuania (by which they meant the northwestern portion of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania)[137] on 5 December of that year. The tsarist regime made a number of concessions as the result of the 1905 uprising. The Baltic states once again were permitted to use their native languages in schooling and public discourse, and Catholic churches were built in Lithuania.[108] Latin characters replaced the Cyrillic alphabet that had been forced upon Lithuanians for four decades. But not even Russian liberals were prepared to concede autonomy similar to that that had already existed in Estonia and Latvia, albeit under Baltic German hegemony. Many Baltic Germans looked toward aligning the Baltics (Lithuania and Courland in particular) with Germany.[138]

After the Russian entry into World War I, the German Empire occupied Lithuania and Courland in 1915. Vilnius fell to the Imperial German Army on 19 September 1915. An alliance with Germany in opposition to both tsarist Russia and Lithuanian nationalism became for the Baltic Germans a real possibility.[138] Lithuania was incorporated into Ober Ost under a German government of occupation.[139] As open annexation could result in a public-relations backlash, the Germans planned to form a network of formally independent states that would in fact be dependent on Germany.[140]

The German occupation government permitted a Vilnius Conference to convene between 18 and 22 September 1917, with the demand that Lithuanians declare loyalty to Germany and agree to an annexation. The intent of the conferees was to begin the process of establishing a Lithuanian state based on ethnic identity and language that would be independent of the Russian Empire, Poland, and the German Empire. The mechanism for this process was to be decided by a constituent assembly, but the German government would not permit elections. Furthermore, the publication of the conference's resolution calling for the creation of a Lithuanian state and elections for a constituent assembly was not allowed.[141] The Conference nonetheless elected a 20-member Council of Lithuania (Taryba) and empowered it to act as the executive authority of the Lithuanian people.[140] The Council, led by Jonas Basanavičius, declared Lithuanian independence as a German protectorate on 11 December 1917, and then adopted the outright Act of Independence of Lithuania on 16 February 1918.[9] It proclaimed Lithuania as an independent republic, organized according to democratic principles.[142] The Germans, weakened by the losses on the Western Front, but still present in the country,[108] did not support such a declaration and hindered attempts to establish actual independence. To prevent being incorporated into the German Empire, Lithuanians elected Monaco-born King Mindaugas II as the titular monarch of the Kingdom of Lithuania in July 1918. Mindaugas II never assumed the throne, however.