La Guerra de Bosnia [a] ( en serbocroata : Rat u Bosni i Hercegovini / Рат у Босни и Херцеговини) fue un conflicto armado internacional que tuvo lugar en Bosnia y Herzegovina entre 1992 y 1995. Se cree que la guerra comenzó el 6 de abril de 1992, tras varios incidentes violentos anteriores. Terminó el 14 de diciembre de 1995 cuando se firmaron los Acuerdos de Dayton . Los principales beligerantes fueron las fuerzas de la República de Bosnia y Herzegovina , la República de Herzeg-Bosnia y la República Srpska , siendo estas dos últimas entidades protoestados liderados y abastecidos por Croacia y Serbia , respectivamente. [12] [13]

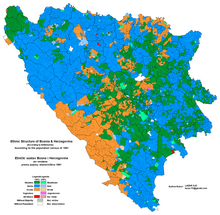

La guerra fue parte de la desintegración de Yugoslavia . Tras la secesión de Eslovenia y Croacia de la República Federativa Socialista de Yugoslavia en 1991, la República Socialista de Bosnia y Herzegovina , un país multiétnico habitado principalmente por bosnios musulmanes (44%), serbios ortodoxos (32,5%) y croatas católicos (17%), aprobó un referéndum de independencia el 29 de febrero de 1992. Los representantes políticos de los serbios de Bosnia boicotearon el referéndum y rechazaron su resultado. Anticipándose al resultado del referéndum, la Asamblea del Pueblo Serbio de Bosnia y Herzegovina adoptó la Constitución de la República Serbia de Bosnia y Herzegovina el 28 de febrero de 1992. Tras la declaración de independencia de Bosnia y Herzegovina (que obtuvo reconocimiento internacional) y tras la retirada de Alija Izetbegović del Plan Cutileiro [14] previamente firmado (que proponía una división de Bosnia en cantones étnicos ), los serbios de Bosnia , liderados por Radovan Karadžić y apoyados por el gobierno de Slobodan Milošević y el Ejército Popular Yugoslavo (JNA), movilizaron sus fuerzas dentro de Bosnia y Herzegovina para asegurar el territorio étnico serbio. La guerra pronto se extendió por todo el país, acompañada de una limpieza étnica .

El conflicto se produjo inicialmente entre las unidades del ejército yugoslavo en Bosnia, que más tarde se transformaron en el Ejército de la República Srpska (VRS), por un lado, y el Ejército de la República de Bosnia y Herzegovina (ARBiH), compuesto en gran parte por bosnios, y las fuerzas croatas del Consejo de Defensa de Croacia (HVO), por el otro. Las tensiones entre croatas y bosnios aumentaron a lo largo de finales de 1992, lo que dio lugar a la escalada de la guerra croata-bosnia a principios de 1993. [15] La guerra de Bosnia se caracterizó por combates encarnizados, bombardeos indiscriminados de ciudades y pueblos, limpieza étnica y violaciones masivas sistemáticas , perpetradas principalmente por fuerzas serbias [16] y, en menor medida, croatas [17] y bosnias [18] . Eventos como el asedio de Sarajevo y la masacre de Srebrenica de julio de 1995 se convirtieron más tarde en icónicos del conflicto. La masacre de más de 8.000 hombres bosnios por parte de las fuerzas serbias en Srebrenica es el único incidente en Europa que ha sido reconocido como genocidio desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial . [19]

Los serbios, aunque inicialmente militarmente superiores debido a las armas y recursos proporcionados por el JNA, finalmente perdieron impulso cuando los bosnios y croatas se aliaron contra la República Srpska en 1994 con la creación de la Federación de Bosnia y Herzegovina tras el Acuerdo de Washington . Pakistán ignoró la prohibición de la ONU sobre el suministro de armas y misiles antitanque transportados por aire a los musulmanes bosnios, mientras que después de las masacres de Srebrenica y Markale , la OTAN intervino en 1995 con la Operación Fuerza Deliberada , apuntando a las posiciones del Ejército de la República Srpska, que resultó clave para poner fin a la guerra. [20] [21] La guerra terminó después de la firma del Acuerdo Marco General para la Paz en Bosnia y Herzegovina en París el 14 de diciembre de 1995. Las negociaciones de paz se llevaron a cabo en Dayton, Ohio , y finalizaron el 21 de noviembre de 1995. [22]

A principios de 2008, el Tribunal Penal Internacional para la ex Yugoslavia había condenado a cuarenta y cinco serbios, doce croatas y cuatro bosnios por crímenes de guerra en relación con la guerra en Bosnia. [23] [ necesita actualización ] Las estimaciones sugieren que más de 100.000 personas murieron durante la guerra. [24] [25] [26] Más de 2,2 millones de personas fueron desplazadas, [27] convirtiéndolo, en ese momento, en el conflicto más violento en Europa desde el final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. [28] [29] Además, se estima que entre 12.000 y 50.000 mujeres fueron violadas , principalmente por fuerzas serbias, y la mayoría de las víctimas fueron mujeres bosnias. [30] [31]

Los enfrentamientos entre bosnios, croatas y serbios en Bosnia comenzaron a finales de febrero de 1992, y "las hostilidades a gran escala habían estallado el 6 de abril", [6] el mismo día en que los Estados Unidos [32] y la Comunidad Económica Europea (CEE) [33] reconocieron a Bosnia y Herzegovina. [34] [35] Misha Glenny da una fecha del 22 de marzo, Tom Gallagher da el 2 de abril, mientras que Mary Kaldor , Laura Silber y Allan Little dan el 6 de abril. [36] Philip Hammond afirmó que la opinión más común es que la guerra comenzó el 6 de abril. [34]

Los serbios consideran el tiroteo de la boda de Sarajevo , cuando el padre del novio fue asesinado el segundo día del referéndum de independencia de Bosnia , el 1 de marzo de 1992, como la primera muerte de la guerra. [37] Las matanzas de serbios de Sijekovac tuvieron lugar el 26 de marzo y la masacre de Bijeljina el 1 y 2 de abril. El 5 de abril, después de que los manifestantes se acercaran a una barricada, un manifestante fue asesinado por las fuerzas serbias. [38]

La guerra llegó a su fin con el Acuerdo Marco General de Paz en Bosnia y Herzegovina , negociado en la Base Aérea Wright-Patterson en Dayton, Ohio, entre el 1 y el 21 de noviembre de 1995 y firmado en París el 14 de diciembre. [39]

La guerra se produjo como resultado de la desintegración de la República Federativa Socialista de Yugoslavia . En Yugoslavia surgió una crisis como resultado del debilitamiento del sistema de confederación al final de la Guerra Fría . En Yugoslavia, el partido comunista nacional , la Liga de Comunistas de Yugoslavia , perdió potencia ideológica. Mientras tanto, el nacionalismo étnico experimentó un renacimiento en la década de 1980 después de la violencia en Kosovo . [40] Mientras que el objetivo de los nacionalistas serbios era la centralización de Yugoslavia, otras nacionalidades aspiraban a la federalización y la descentralización del estado. [41]

Bosnia y Herzegovina, antigua provincia otomana , ha sido históricamente un Estado multiétnico. Según el censo de 1991, el 44% de la población se consideraba musulmana (bosnia), el 33% serbia, el 17% croata y el 6% yugoslavo. [42]

En marzo de 1989, la crisis en Yugoslavia se profundizó tras la adopción de enmiendas a la Constitución serbia que permitían al gobierno de Serbia dominar las provincias de Kosovo y Vojvodina . [43] Hasta entonces, la toma de decisiones de Kosovo y Vojvodina era independiente, y cada provincia autónoma tenía un voto a nivel federal yugoslavo. Serbia, bajo el recién elegido presidente Slobodan Milošević , obtuvo el control de tres de los ocho votos en la presidencia yugoslava. Con los votos adicionales de Montenegro, Serbia pudo así influir fuertemente en las decisiones del gobierno federal. Esta situación provocó objeciones de las otras repúblicas y llamados a la reforma de la federación yugoslava.

En el XIV Congreso Extraordinario de la Liga de Comunistas de Yugoslavia, celebrado el 20 de enero de 1990, las delegaciones de las repúblicas no pudieron ponerse de acuerdo sobre las principales cuestiones que enfrentaba la federación yugoslava. Como resultado, los delegados eslovenos y croatas abandonaron el Congreso. La delegación eslovena, encabezada por Milan Kučan , exigió cambios democráticos y una federación más flexible, mientras que la delegación serbia, encabezada por Milošević, se opuso. [44]

En las primeras elecciones multipartidistas en Bosnia y Herzegovina, en noviembre de 1990, los votos se emitieron en gran medida según la etnia, lo que llevó al éxito del Partido Bosnio de Acción Democrática (SDA), el Partido Democrático Serbio (SDS) y la Unión Democrática Croata (HDZ BiH). [45]

Los partidos dividían el poder según líneas étnicas, de modo que el presidente de la presidencia de la República Socialista de Bosnia y Herzegovina era un bosnio, el presidente del Parlamento era un serbio y el primer ministro era un croata. Los partidos nacionalistas separatistas alcanzaron el poder en otras repúblicas, incluidas Croacia y Eslovenia. [46]

A principios de 1991 se celebraron reuniones entre los dirigentes de las seis repúblicas yugoslavas y de las dos regiones autónomas para tratar la crisis. [47] Los dirigentes serbios estaban a favor de una solución federal, mientras que los croatas y eslovenos estaban a favor de una alianza de estados soberanos. El dirigente bosnio Alija Izetbegović propuso en febrero una federación asimétrica, en la que Eslovenia y Croacia mantendrían vínculos laxos con las cuatro repúblicas restantes. Poco después, cambió de postura y optó por una Bosnia soberana como requisito previo para dicha federación. [48]

El 25 de marzo, Franjo Tuđman y el presidente serbio Slobodan Milošević se reunieron en Karađorđevo . [49] La reunión fue controvertida debido a las afirmaciones de algunos políticos yugoslavos de que los dos presidentes habían acordado la partición de Bosnia y Herzegovina. [50] El 6 de junio, Izetbegović y el presidente macedonio Kiro Gligorov propusieron una confederación débil entre Croacia, Eslovenia y una federación de las otras cuatro repúblicas. Esta propuesta fue rechazada por la administración de Milošević. [51]

El 25 de junio de 1991, Eslovenia y Croacia declararon su independencia. Se desató un conflicto armado en Eslovenia, mientras que los enfrentamientos en zonas de Croacia con importantes poblaciones étnicamente serbias se intensificaron hasta convertirse en una guerra a gran escala . [52] El Ejército Popular Yugoslavo (JNA) abandonó sus esfuerzos por recuperar el control sobre Eslovenia en julio, mientras que los combates en Croacia se intensificaron hasta que se acordó un alto el fuego en enero de 1992. El JNA también atacó a Croacia desde Bosnia y Herzegovina. [53]

En julio de 1991, representantes del Partido Democrático Serbio (SDS), entre ellos el presidente del SDS Radovan Karadžić , Muhamed Filipović y Adil Zulfikarpašić de la Organización Musulmana Bosniak (MBO), redactaron un acuerdo conocido como el acuerdo Zulfikarpašić-Karadžić . Este dejaría a la SR Bosnia y Herzegovina en una unión estatal con la SR Serbia y la SR Montenegro. El acuerdo fue denunciado por los partidos políticos croatas. Aunque inicialmente acogió con agrado la iniciativa, la administración de Izetbegović más tarde desestimó el acuerdo. [54] [55]

Entre septiembre y noviembre de 1991, el SDS organizó la creación de seis « regiones autónomas serbias » (SAO). [56] Esto fue en respuesta a las medidas adoptadas por los bosnios para separarse de Yugoslavia. [57] Los croatas de Bosnia tomaron medidas similares. [57]

En agosto de 1991, la Comunidad Económica Europea organizó una conferencia en un intento de evitar que Bosnia y Herzegovina se deslizara hacia la guerra. El 25 de septiembre de 1991, el Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas aprobó la Resolución 713 , imponiendo un embargo de armas a todos los territorios de la ex Yugoslavia. El embargo tuvo poco efecto sobre el JNA y las fuerzas serbias. Las fuerzas croatas habían confiscado armamento al JNA durante la Batalla de los Cuarteles . El embargo tuvo un impacto significativo en Bosnia y Herzegovina al comienzo de la Guerra de Bosnia. [58] Las fuerzas serbias heredaron el armamento y el equipo del JNA, mientras que las fuerzas croatas y bosnias obtuvieron armas a través de Croacia en violación del embargo. [59]

El 19 de septiembre de 1991, el JNA trasladó tropas adicionales a la zona de la ciudad de Mostar , lo que provocó la protesta del gobierno local. El 20 de septiembre de 1991, el JNA trasladó tropas al frente de Vukovar a través de la región de Višegrad , en el noreste de Bosnia. En respuesta, los croatas y bosnios locales levantaron barricadas y puestos de ametralladoras. Detuvieron una columna de 60 tanques del JNA, pero fueron dispersados por la fuerza al día siguiente. Más de 1.000 personas tuvieron que huir de la zona. Esta acción, casi siete meses antes del inicio de la guerra de Bosnia, causó las primeras bajas de las guerras yugoslavas en Bosnia. En los primeros días de octubre, el JNA atacó y arrasó la aldea croata de Ravno , en el este de Herzegovina, en su camino a atacar Dubrovnik, en el sur de Croacia. [60]

El 6 de octubre de 1991, el presidente bosnio Alija Izetbegović pronunció una declaración televisada de neutralidad, que incluía la siguiente declaración: "no es nuestra guerra". [61] Izetbegović hizo una declaración ante el parlamento bosnio el 14 de octubre con respecto al JNA: "No hagan nada contra el ejército. (...) la presencia del ejército es un factor estabilizador para nosotros, y necesitamos ese ejército... Hasta ahora, no hemos tenido problemas con el ejército, y no los tendremos más adelante". Izetbegović tuvo un tenso intercambio con el líder serbobosnio Radovan Karadžić en el parlamento ese día. Después de que Karadžić apostara a que los musulmanes bosnios no podrían defenderse si se desarrollaba un estado de guerra, Izetbegović observó que encontraba ofensiva la manera y el discurso de Karadžić y que eso explicaba por qué los bosnios se sentían mal recibidos, que su tono podría explicar por qué los demás federados por Yugoslavia se sentían repelidos, y que las amenazas de Karadžić eran indignas del pueblo serbio. [62]

A lo largo de 1990, el SDB y un grupo de oficiales serbios seleccionados del Ejército Popular Yugoslavo (JNA) desarrollaron el Plan RAM con el propósito de organizar a los serbios fuera de Serbia, consolidar el control de los incipientes partidos del SDS y el posicionamiento de armas y municiones. [63] El plan tenía por objeto preparar el marco para una tercera Yugoslavia en la que todos los serbios con sus territorios vivirían juntos en el mismo estado. [64]

El periodista Giuseppe Zaccaria resumió una reunión de oficiales del ejército serbio en Belgrado en 1992, informando que habían adoptado una política explícita para atacar a las mujeres y los niños como la parte vulnerable de la estructura social musulmana. [65] Según algunas fuentes, el plan RAM fue elaborado en la década de 1980. [66] Su existencia fue filtrada por Ante Marković , el primer ministro de Yugoslavia , un croata étnico de Bosnia y Herzegovina. La existencia y posible implementación de este plan alarmó al gobierno bosnio. [67] [68]

El 15 de octubre de 1991, el Parlamento de la República Socialista de Bosnia y Herzegovina en Sarajevo aprobó un " Memorando sobre la Soberanía de Bosnia y Herzegovina " por mayoría simple. [69] [70] El Memorando fue fuertemente cuestionado por los miembros serbios de Bosnia del Parlamento, argumentando que la Constitución exigía garantías procesales y una mayoría de dos tercios para tales cuestiones. El Memorando fue debatido de todos modos, lo que llevó a un boicot del Parlamento por parte de los serbios de Bosnia, y la legislación fue aprobada. [71] Los representantes políticos serbios proclamaron la Asamblea del Pueblo Serbio de Bosnia y Herzegovina el 24 de octubre de 1991, declarando que el pueblo serbio deseaba permanecer en Yugoslavia. [57] El Partido de Acción Democrática (SDA), dirigido por Alija Izetbegović, estaba decidido a buscar la independencia y contaba con el apoyo de Europa y los EE. UU. [72] El SDS dejó en claro que si se declaraba la independencia, los serbios se separarían, ya que era su derecho ejercer la autodeterminación. [72]

La HDZ BiH se creó como una rama del partido gobernante en Croacia, la Unión Democrática Croata (HDZ). Si bien pedía la independencia del país, hubo una división en el partido y algunos abogaban por la secesión de las áreas de mayoría croata. [73] En noviembre de 1991, los líderes croatas organizaron comunidades autónomas en áreas con mayoría croata. El 12 de noviembre de 1991, se estableció la Comunidad Croata de Bosnia Posavina en Bosanski Brod . Abarcaba ocho municipios en el norte de Bosnia. [74] El 18 de noviembre de 1991, se estableció la Comunidad Croata de Herzeg-Bosnia en Mostar. Mate Boban fue elegido como su presidente. [75] Su documento fundacional decía: "La Comunidad respetará al gobierno elegido democráticamente de la República de Bosnia y Herzegovina mientras exista la independencia estatal de Bosnia y Herzegovina en relación con la antigua Yugoslavia o cualquier otra". [76]

Las memorias de Borisav Jović muestran que el 5 de diciembre de 1991 Milošević ordenó que las tropas del JNA en Bosnia y Herzegovina se reorganizaran y que su personal no bosnio se retirara, en caso de que el reconocimiento diera como resultado la percepción del JNA como una fuerza extranjera; los serbios de Bosnia permanecerían para formar el núcleo de un ejército serbio de Bosnia. [77] En consecuencia, a finales de mes sólo el 10-15% del personal del JNA en Bosnia y Herzegovina era de fuera de la república. [77] Silber y Little señalan que Milošević ordenó en secreto que todos los soldados del JNA nacidos en Bosnia y Herzegovina fueran transferidos a Bosnia y Herzegovina. [77] Las memorias de Jović sugieren que Milošević planeó un ataque a Bosnia con mucha antelación. [77]

El 9 de enero de 1992, los serbios de Bosnia proclamaron la «República del Pueblo Serbio en Bosnia-Herzegovina» (SR BiH, más tarde Republika Srpska ), pero no declararon oficialmente la independencia. [57] La Comisión de Arbitraje de la Conferencia de Paz sobre Yugoslavia, en su Opinión Nº 4 del 11 de enero de 1992 sobre Bosnia y Herzegovina, declaró que no se debía reconocer la independencia de Bosnia y Herzegovina porque el país aún no había celebrado un referéndum sobre la independencia. [78]

El 25 de enero de 1992, una hora después de que se suspendiera la sesión del parlamento, éste convocó a un referéndum sobre la independencia para el 29 de febrero y el 1 de marzo. [69] El debate había terminado después de que los diputados serbios se retiraran después de que los delegados bosnio-croatas mayoritarios rechazaran una moción para que la cuestión del referéndum se sometiera al Consejo de Igualdad Nacional, que aún no se había establecido. [79] La propuesta de referéndum fue adoptada en la forma propuesta por los diputados musulmanes, en ausencia de los miembros del SDS. [79] Como señalan Burg y Shoup, "la decisión puso al gobierno bosnio y a los serbios en una situación de colisión". [79] El referéndum que se avecinaba causó preocupación internacional en febrero. [80]

La guerra croata daría lugar a la Resolución 743 del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas el 21 de febrero de 1992, que creó la Fuerza de Protección de las Naciones Unidas (UNPROFOR). Durante las conversaciones en Lisboa el 21 y 22 de febrero, el mediador de la CE, José Cutileiro , presentó un plan de paz que proponía que el estado independiente de Bosnia se dividiera en tres unidades constituyentes. El acuerdo fue denunciado por los líderes bosnios el 25 de febrero. [80] El 28 de febrero de 1992, la Constitución de la República de Bosnia y Herzegovina declaró que el territorio de esa República incluía "los territorios de las regiones y distritos autónomos serbios y de otras entidades étnicas serbias en Bosnia y Herzegovina, incluidas las regiones en las que el pueblo serbio permaneció en minoría debido al genocidio llevado a cabo contra él en la Segunda Guerra Mundial", y se declaró parte de Yugoslavia. [81]

Los miembros de la Asamblea de los serbios de Bosnia aconsejaron a los serbios que boicotearan los referendos celebrados el 29 de febrero y el 1 de marzo de 1992. Se informó de que la participación en los referendos fue del 64%, y que el 93% de los votantes votó a favor de la independencia (lo que implica que los serbios de Bosnia, que constituían aproximadamente el 34% de la población, en gran medida boicotearon el referendo). [82] Los dirigentes políticos serbios utilizaron los referendos como pretexto para levantar barricadas en protesta. El parlamento bosnio declaró formalmente la independencia el 3 de marzo de 1992. [32]

Durante el referéndum del 1 de marzo, Sarajevo estuvo tranquila, salvo por un tiroteo en el que se celebraba una boda serbia. [83] Los musulmanes consideraron que el blandir banderas serbias en la Baščaršija era una provocación deliberada el día del referéndum. [84] Nikola Gardović , el padre del novio, fue asesinado, y un sacerdote ortodoxo serbio resultó herido. Los testigos identificaron al asesino como Ramiz Delalić , un gánster que se había convertido en un delincuente descarado desde la caída del comunismo y que se decía que había sido miembro del grupo paramilitar bosnio " Boinas Verdes ". Se emitieron órdenes de arresto contra él y otro presunto agresor. El SDS denunció el asesinato y afirmó que el hecho de que no lo arrestaran se debió a la complicidad del SDA o del gobierno bosnio. [85] [86] Un portavoz del SDS declaró que era una prueba de que los serbios estaban en peligro mortal y que lo estarían aún más en una Bosnia independiente, lo que fue rechazado por Sefer Halilović , fundador de la Liga Patriótica , quien afirmó que no se trataba de una boda sino de una provocación y acusó a los invitados a la boda de ser activistas del SDS. A la mañana siguiente aparecieron barricadas en puntos de tránsito clave en toda la ciudad y estaban ocupadas por partidarios del SDS armados y enmascarados. [87]

Tras la declaración de independencia de Bosnia y Herzegovina de Yugoslavia el 3 de marzo de 1992, estallaron combates esporádicos entre los serbios y las fuerzas gubernamentales en todo el territorio. [88] El 18 de marzo de 1992, las tres partes firmaron el Acuerdo de Lisboa : Alija Izetbegović por los bosnios, Radovan Karadžić por los serbios y Mate Boban por los croatas. Sin embargo, el 28 de marzo de 1992, Izetbegović, tras reunirse con el embajador de los Estados Unidos en Yugoslavia, Warren Zimmermann, en Sarajevo, retiró su firma y declaró su oposición a cualquier tipo de división étnica de Bosnia. [89] [90]

No está claro qué se dijo ni quién lo dijo. Zimmerman niega haber dicho a Izetbegovic que si retiraba su firma, Estados Unidos concedería el reconocimiento de Bosnia como Estado independiente. Lo que es indiscutible es que Izetbegovic, ese mismo día, retiró su firma y renunció al acuerdo. [91]

A finales de marzo de 1992, hubo combates entre serbios y fuerzas combinadas croatas y bosnias en Bosanski Brod y sus alrededores , [92] lo que resultó en la muerte de serbios en Sijekovac . [93] Los paramilitares serbios cometieron la masacre de Bijeljina , la mayoría de las víctimas eran bosnios, el 1 y 2 de abril de 1992. [94]

Había tres facciones en la guerra de Bosnia:

Los tres grupos étnicos apoyaron predominantemente a su respectiva facción étnica o nacional: los bosnios, principalmente, a la ARBiH, los croatas al HVO y los serbios al VRS. En cada facción había voluntarios extranjeros .

Los bosnios se organizaron principalmente en el Ejército de la República de Bosnia y Herzegovina ( Armija Republike Bosne i Hercegovine , ARBiH) como las fuerzas armadas de la República de Bosnia y Herzegovina . Las fuerzas de la República de Bosnia y Herzegovina se dividieron en cinco cuerpos. El 1.er Cuerpo operaba en la región de Sarajevo y Goražde, mientras que el 5.º Cuerpo, más fuerte, estaba posicionado en la zona occidental de Bosanska Krajina , que cooperaba con las unidades del HVO en Bihać y sus alrededores . Las fuerzas del gobierno bosnio estaban mal equipadas y no estaban preparadas para la guerra. [95]

En junio de 1992, Sefer Halilović , jefe del Estado Mayor de la Defensa Territorial de Bosnia, afirmó que sus fuerzas estaban compuestas por un 70% de musulmanes, un 18% de croatas y un 12% de serbios. [96] El porcentaje de soldados serbios y croatas en el ejército bosnio era particularmente alto en Sarajevo, Mostar y Tuzla. [97] El comandante adjunto del Cuartel General del Ejército bosnio era el general Jovan Divjak , el serbio étnico de mayor rango en el ejército bosnio. El general Stjepan Šiber , de etnia croata, era el segundo comandante adjunto. Izetbegović también nombró al coronel Blaž Kraljević , comandante de las Fuerzas de Defensa Croatas en Herzegovina , para que fuera miembro del Cuartel General del Ejército bosnio, siete días antes del asesinato de Kraljević, con el fin de reunir un frente de defensa multiétnico pro-bosnio. [98] Esta diversidad se reduciría a lo largo de la guerra. [96] [99]

El gobierno bosnio presionó para que se levantara el embargo de armas, pero el Reino Unido, Francia y Rusia se opusieron. Las propuestas estadounidenses de seguir esta política se conocieron como " lift and strike" . El Congreso de los Estados Unidos aprobó dos resoluciones pidiendo que se levantara el embargo, pero ambas fueron vetadas por el presidente Bill Clinton por temor a crear una grieta entre los Estados Unidos y los países antes mencionados. No obstante, los Estados Unidos utilizaron tanto aviones de transporte C-130 " negros " como canales secundarios , incluidos grupos islamistas , para contrabandear armas a las fuerzas bosnio-musulmanas, así como también permitieron que las armas suministradas por Irán transitaran a través de Croacia hacia Bosnia. [100] [101] [102] Sin embargo, a la luz de la oposición generalizada de la OTAN a los esfuerzos estadounidenses (y posiblemente turcos) por coordinar los "vuelos negros de Tuzla ", el Reino Unido y Noruega expresaron su desaprobación de estas medidas y sus efectos contraproducentes en la aplicación del embargo de armas por parte de la OTAN. [103]

Entre 1992 y 1995, el Servicio de Inteligencia Interservicios de Pakistán suministró en secreto armas, municiones y misiles antitanque guiados a los combatientes musulmanes para darles una oportunidad contra los serbios. Pakistán estaba desafiando así el embargo de armas de la ONU. El general Javed Nasir afirmó más tarde que el ISI había transportado misiles antitanque guiados por vía aérea a Bosnia, lo que finalmente inclinó la balanza a favor de los musulmanes bosnios y obligó a los serbios a levantar el asedio. [104] [105] [106]

En su libro The Clinton Tapes: Wrestling History with the President de 2009, el historiador y autor Taylor Branch , amigo del presidente estadounidense Bill Clinton , hizo públicas más de 70 sesiones grabadas con el presidente durante su presidencia desde 1993 hasta 2001. [107] [108] Según una sesión grabada el 14 de octubre de 1993, se afirma que:

Clinton dijo que los aliados de Estados Unidos en Europa bloquearon las propuestas para ajustar o eliminar el embargo. Justificaron su oposición con argumentos humanitarios plausibles, argumentando que más armas sólo alimentarían el derramamiento de sangre, pero en privado, dijo el presidente, los aliados clave objetaron que una Bosnia independiente sería "antinatural" como la única nación musulmana en Europa. Dijo que favorecían el embargo precisamente porque fijaba la desventaja de Bosnia. [...] Cuando expresé mi sorpresa por tal cinismo, reminiscente de la diplomacia de la vista gorda con respecto a la difícil situación de los judíos de Europa durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el presidente Clinton se encogió de hombros. Dijo que el presidente francés François Mitterrand había sido especialmente franco al decir que Bosnia no pertenecía a ese lugar, y que los funcionarios británicos también hablaron de una restauración dolorosa pero realista de la Europa cristiana. Contra Gran Bretaña y Francia, dijo, el canciller alemán Helmut Kohl, entre otros, había apoyado iniciativas para reconsiderar el embargo de armas de las Naciones Unidas, fracasando en parte porque Alemania no tenía un asiento en el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU.

— Taylor Branch, Las cintas de Clinton: La historia de la lucha con el presidente [109]

Los croatas comenzaron a organizar sus fuerzas militares a finales de 1991. El 8 de abril de 1992 se fundó el Consejo de Defensa Croata ( Hrvatsko vijeće obrane , HVO) como el "órgano supremo de defensa croata en Herzeg-Bosnia". [110] El HVO se organizó en cuatro zonas operativas con sedes en Mostar, Tomislavgrad, Vitez y Orašje. [111] En febrero de 1993, el Estado Mayor del HVO estimó la fuerza del HVO en 34.080 oficiales y soldados. [4] Su armamento incluía alrededor de 50 carros de combate principales, principalmente T-34 y T-55, y 500 armas de artillería diversas. [112]

Al comienzo de la guerra, el gobierno croata ayudó a armar tanto a las fuerzas croatas como a las bosnias. [113] Se establecieron centros logísticos en Zagreb y Rijeka para el reclutamiento de soldados para la ARBiH. [114] La Guardia Nacional Croata (Zbor Narodne Garde, ZNG), posteriormente rebautizada oficialmente como Ejército Croata ( Hrvatska vojska , HV) participó en Posavina, Herzegovina y Bosnia occidental contra las fuerzas serbias. [115] Durante el conflicto croata-bosnio , el gobierno croata proporcionó armas al HVO y organizó el envío de unidades de voluntarios, con orígenes en Bosnia y Herzegovina, al HVO. [116]

Las Fuerzas de Defensa de Croacia (HOS), el ala paramilitar del Partido Croata de los Derechos , lucharon contra las fuerzas serbias junto con el HVO y la ARBiH. Las HOS se disolvieron poco después de la muerte de su comandante Blaž Kraljević y se incorporaron al HVO y la ARBiH. [117]

El Ejército de la República Srpska ( Vojska Republike Srpske , VRS) fue creado el 12 de mayo de 1992. Era leal a la República Srpska , la parte de Bosnia poblada por serbios que no deseaba separarse de Yugoslavia . El líder político serbobosnio Radovan Karadžić declaró: "Nuestro objetivo óptimo es una Gran Serbia , y si no eso, entonces una Yugoslavia Federal". [118]

Serbia proporcionó apoyo logístico, dinero y suministros al VRS. Los serbios de Bosnia habían constituido una parte sustancial del cuerpo de oficiales del JNA. Milošević dependía de los serbios de Bosnia para ganar la guerra por sí mismos. La mayor parte de la cadena de mando, el armamento y el personal militar de alto rango, incluido el general Ratko Mladić , eran del JNA. [119]

Varias unidades paramilitares operaron durante la Guerra de Bosnia: las " Águilas Blancas " serbias ( Beli Orlovi ) y la " Guardia Voluntaria Serbia " ( Srpska Dobrovoljačka Garda ), también conocidas como "Tigres de Arkan"; la " Liga Patriótica " bosnia ( Patriotska Liga ) y los " Boinas Verdes " ( Zelene Beretke ); y las " Fuerzas de Defensa Croatas " ( Hrvatske Obrambene Snage ), etc. Los paramilitares serbios y croatas involucraban voluntarios de Serbia y Croacia, y eran apoyados por partidos políticos nacionalistas en esos países.

La guerra atrajo a combatientes extranjeros [120] [121] y mercenarios de varios países. Los voluntarios acudieron a luchar por diversas razones, incluidas las lealtades religiosas o étnicas y, en algunos casos, por dinero. Como regla general, los bosnios recibieron apoyo de los países islámicos, los serbios de los países ortodoxos orientales y los croatas de los países católicos. La presencia de combatientes extranjeros está bien documentada, sin embargo, ninguno de estos grupos comprendía más del 5 por ciento de la fuerza total de los respectivos ejércitos. [122]

Los serbios de Bosnia recibieron apoyo de combatientes cristianos eslavos de varios países de Europa del Este, [123] [124] incluidos voluntarios de otros países cristianos ortodoxos . Entre ellos había cientos de rusos, [125] alrededor de 100 griegos, [126] y algunos ucranianos y rumanos. [126] Algunos estiman que había hasta 1.000 voluntarios de ese tipo. [127] Se informó de que voluntarios griegos de la Guardia Voluntaria Griega participaron en la Masacre de Srebrenica , y que la bandera griega se izó en Srebrenica cuando la ciudad cayó en manos de los serbios. [128]

Algunas personas de otros países europeos se ofrecieron como voluntarios para luchar en el bando croata, incluidos neonazis como Jackie Arklöv , que fue acusado de crímenes de guerra a su regreso a Suecia . Más tarde confesó haber cometido crímenes de guerra contra civiles musulmanes bosnios en los campos de Heliodrom y Dretelj como miembro de las fuerzas croatas. [129]

Los bosnios recibieron apoyo de grupos musulmanes. Pakistán apoyó a Bosnia al tiempo que proporcionaba apoyo técnico y militar. [130] [131] El Servicio de Inteligencia Interservicios (ISI) de Pakistán supuestamente dirigió un programa de inteligencia militar activo durante la guerra de Bosnia que comenzó en 1992 y duró hasta 1995. Ejecutado y supervisado por el general paquistaní Javed Nasir , el programa proporcionó logística y suministros de municiones a varios grupos de muyahidines bosnios durante la guerra. El contingente bosnio del ISI se organizó con asistencia financiera proporcionada por Arabia Saudita , según el historiador británico Mark Curtis . [132]

Según The Washington Post , Arabia Saudita proporcionó 300 millones de dólares en armas a las fuerzas gubernamentales en Bosnia con el conocimiento y la cooperación tácita de los Estados Unidos, una afirmación negada por los funcionarios estadounidenses. [133] Los combatientes musulmanes extranjeros también se unieron a las filas de los musulmanes bosnios, incluidos los de la organización guerrillera libanesa Hezbolá , [134] y la organización global Al Qaeda . [135] [136] [137] [138]

Desde julio de 1991 hasta enero de 1992, durante la Guerra de Independencia de Croacia , el JNA y los paramilitares serbios utilizaron territorio bosnio para lanzar ataques contra Croacia. [139] [140] El JNA armó a los serbios de Bosnia y la Fuerza de Defensa Croata armó a los croatas de Herzegovina durante la guerra en Croacia. [141] Los Boinas Verdes musulmanes bosnios ya se habían establecido en el otoño de 1991 y elaboraron un plan de defensa en febrero de 1992. [141] Se estimó que entre 250.000 y 300.000 bosnios estaban armados y que unos 10.000 estaban luchando en Croacia. [142] En marzo de 1992, quizás tres cuartas partes del país estaban en manos de nacionalistas serbios y croatas. [142] El 4 de abril de 1992, Izetbegović ordenó a todos los reservistas y a la policía de Sarajevo que se movilizaran, y el SDS pidió la evacuación de los serbios de la ciudad, lo que marcó la "ruptura definitiva entre el gobierno bosnio y los serbios". [143] Bosnia y Herzegovina recibió el reconocimiento internacional el 6 de abril de 1992. [32] La opinión más común es que la guerra comenzó ese día. [144]

La guerra en Bosnia se intensificó en abril. [145] El 3 de abril, comenzó la Batalla de Kupres entre el JNA y una fuerza combinada del HV-HVO que terminó en una victoria del JNA. [146] El 6 de abril, las fuerzas serbias comenzaron a bombardear Sarajevo , y en los dos días siguientes cruzaron el Drina desde Serbia propiamente dicha y sitiaron las ciudades de mayoría musulmana de Zvornik , Višegrad y Foča . [143] Después de la captura de Zvornik, las tropas serbias de Bosnia mataron a varios cientos de musulmanes y obligaron a decenas de miles a huir. [147] Toda Bosnia estaba envuelta en la guerra a mediados de abril. [143] El 23 de abril, el JNA evacuó a su personal en helicóptero de los cuarteles de Čapljina , [148] que habían estado bloqueados desde el 4 de marzo. [149] Hubo esfuerzos para detener la violencia. [150] El 27 de abril, el gobierno bosnio ordenó que el JNA fuera puesto bajo control civil o expulsado, lo que fue seguido por conflictos a principios de mayo entre los dos. [151] Prijedor fue tomada por los serbios el 30 de abril. [152] El 2 de mayo, los Boinas Verdes y miembros de pandillas locales contraatacaron un ataque serbio desorganizado destinado a cortar Sarajevo en dos. [151] El 3 de mayo, Izetbegović fue secuestrado en el aeropuerto de Sarajevo por oficiales del JNA, y utilizado para obtener un paso seguro de las tropas del JNA desde el centro de Sarajevo. [151] Sin embargo, las fuerzas bosnias atacaron el convoy del JNA que salía , lo que amargó a todos los bandos. [151] Un alto el fuego y un acuerdo sobre la evacuación del JNA se firmaron el 18 de mayo, y el 20 de mayo la presidencia bosnia declaró al JNA una fuerza de ocupación. [151]

El Ejército de la República Srpska fue creado recientemente y puesto bajo el mando del general Ratko Mladić , en una nueva fase de la guerra. [151] Los bombardeos sobre Sarajevo los días 24, 26, 28 y 29 de mayo fueron atribuidos a Mladić por el Secretario General de la ONU Boutros Boutros-Ghali . [153] Las bajas civiles de un bombardeo del 27 de mayo llevaron a la intervención occidental, en forma de sanciones impuestas el 30 de mayo a través de la Resolución 757 del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas . [153] Las fuerzas bosnias atacaron los cuarteles del JNA en la ciudad, a lo que siguió un intenso bombardeo. [153] El 5 y 6 de junio, el último personal del JNA abandonó la ciudad durante los combates callejeros y los bombardeos. [153] El alto el fuego del 20 de junio, ejecutado para que la ONU se hiciera cargo del aeropuerto de Sarajevo para vuelos humanitarios, se rompió cuando ambos bandos lucharon por el territorio entre la ciudad y el aeropuerto. [153] La crisis del aeropuerto llevó a Boutros-Ghali a dar el ultimátum el 26 de junio: que los serbios detuvieran los ataques a la ciudad, permitieran a la ONU tomar el aeropuerto y pusieran sus armas pesadas bajo la supervisión de la ONU. [153] Mientras tanto, los medios de comunicación informaron de que Bush estaba considerando el uso de la fuerza en Bosnia. [153] La opinión pública mundial estaba "decisiva y permanentemente en contra de los serbios" tras los informes de los medios de comunicación sobre los ataques con francotiradores y los bombardeos de Sarajevo. [154]

Fuera de Sarajevo, los éxitos de los combatientes variaron enormemente en 1992. [154] Los serbios habían tomado ciudades de mayoría musulmana a lo largo de los ríos Drina y Sava y expulsado a su población musulmana en cuestión de meses. [154] Una ofensiva conjunta bosnia-HVO en mayo, habiendo aprovechado la confusión tras la retirada del JNA, revirtió los avances serbios en Posavina y Bosnia central. [154] La ofensiva continuó hacia el sur, sitiando Doboj, cortando así a las fuerzas serbias en Bosanska Krajina de Semberija y Serbia. [154] A mediados de mayo, Srebrenica fue retomada por fuerzas bosnias bajo el mando de Naser Orić . [154] Las fuerzas serbias sufrieron una costosa derrota en Bosnia oriental en mayo, cuando, según relatos serbios, la fuerza de Avdo Palić fue emboscada cerca de Srebrenica, matando a 400 personas. [154] De mayo a agosto, Goražde fue sitiada por el VRS, hasta que el sitio fue roto por la ARBiH el 1 de septiembre. [155] En abril de 1992, el Consejo de Defensa Croata (HVO) entró en Orašje y, según fuentes croatas, comenzó una campaña de acoso contra civiles serbios, incluyendo tortura, violación y asesinato. [156] [157]

El 15 de mayo de 1992, una columna del JNA fue víctima de una emboscada en Tuzla . La 92.ª Brigada Motorizada del JNA recibió órdenes de abandonar Tuzla y Bosnia-Herzegovina y entrar en Serbia. Se llegó a un acuerdo con el gobierno bosnio según el cual las unidades del JNA tendrían hasta el 19 de mayo para abandonar Bosnia de forma pacífica. A pesar del acuerdo, el convoy fue atacado en el distrito de Brčanska Malta de Tuzla con fusiles y lanzacohetes; se colocaron minas a lo largo de su ruta. 52 soldados del JNA murieron y más de 40 resultaron heridos, la mayoría de etnia serbia. [158] [159]

La República de Bosnia y Herzegovina fue admitida como estado miembro de la ONU el 22 de mayo de 1992. [160] La opinión pública mundial fue sacudida por la existencia de campos de concentración establecidos por el Ejército Popular Yugoslavo (JNA) y las autoridades de la República Srpska (RS), donde miles de musulmanes bosnios y civiles croatas fueron torturados y asesinados. [161] [162] Después de la ocupación de la región de Prijedor, civiles musulmanes fueron capturados y transportados a campos como Omarska , Trnopolje , Keraterm , Manjača , donde soportaron meses de trato inhumano y tortura. [163] [164] Un número significativo fue asesinado o desapareció, lo que marcó el crimen más grave de la guerra hasta el genocidio de Srebrenica tres años después. [165] [166] En la campaña de limpieza étnica se establecieron otros campos para no serbios en toda Bosnia , incluidos Luka , Liplje , Batković , Sušica , Uzamnica , [167] [168] así como campos para la violación de mujeres en Foča y Višegrad . Los bosnios y los croatas establecieron campos, con significativamente menos prisioneros. [169] El TPIY condenó a unas 20 personas por crímenes en estos campos. [170] [171] [172] [173] [174] [175]

De mayo a diciembre de 1992, el Ministerio del Interior de Bosnia (MUP de Bosnia), el HVO y más tarde las Fuerzas de Defensa Territorial de Bosnia (RBiH) operaron el campo de Čelebići . Se utilizó para detener a prisioneros de guerra serbobosnios , muchos de ellos ancianos, arrestados durante operaciones destinadas a desbloquear las rutas a Sarajevo y Mostar en mayo de 1992, que anteriormente habían sido bloqueadas por las fuerzas serbias. [176] De los 700 prisioneros, al menos 13 murieron durante su cautiverio. [177] Los detenidos fueron sometidos a tortura, agresiones sexuales, palizas y otros tratos crueles e inhumanos. Algunos prisioneros fueron fusilados o golpeados hasta la muerte. [178] [179]

El 6 de mayo de 1992, Mate Boban se reunió con Radovan Karadžić en Graz , Austria , donde llegaron a un acuerdo para un alto el fuego y discutieron una demarcación entre una unidad territorial croata y serbia, en Bosnia y Herzegovina. [180] [181] Sin embargo, el alto el fuego se rompió al día siguiente, cuando el JNA y las fuerzas serbias de Bosnia lanzaron un ataque contra posiciones ocupadas por los croatas en Mostar. [182] En junio de 1992, las fuerzas serbias de Bosnia atacaron y bombardearon la aldea bosnia de Žepa, lo que conduciría al asedio de Žepa que duró 3 años .

En junio de 1992, los refugiados y desplazados internos habían llegado a 2,6 millones. [183] En septiembre de 1992, Croacia había aceptado 335.985 refugiados de Bosnia y Herzegovina, en su mayoría civiles bosnios (excluidos los hombres en edad militar). [184] El número de refugiados tensó significativamente la economía y la infraestructura croatas. [185] El entonces embajador de los EE.UU. en Croacia, Peter Galbraith , puso el número de refugiados en Croacia en una perspectiva adecuada en una entrevista el 8 de noviembre de 1993. Dijo que la situación sería el equivalente a que los EE.UU. acogieran a 30.000.000 de refugiados. [186] El número de refugiados bosnios en Croacia, fue superado sólo por el número de desplazados internos dentro de la propia Bosnia y Herzegovina, 588.000. [184] Serbia acogió a 252.130 refugiados de Bosnia, mientras que otras ex repúblicas yugoslavas recibieron un total de 148.657 personas. [184]

En junio de 1992, los serbios de Bosnia iniciaron la Operación Corredor en el norte de Bosnia contra las fuerzas del HV-HVO, para asegurar una carretera abierta entre Belgrado, Banja Luka y Knin. [187] Las muertes reportadas de 12 recién nacidos en el hospital de Banja Luka debido a la escasez de oxígeno embotellado para las incubadoras fueron citadas como una causa inmediata de la acción, [188] pero la veracidad de estas muertes ha sido cuestionada. Borisav Jović, un funcionario serbio contemporáneo de alto rango y miembro de la Presidencia yugoslava , afirmó que el informe era propaganda , afirmando que Banja Luka tenía 2 plantas de producción de oxígeno embotellado en sus inmediaciones y era autosuficiente en ese sentido. [189] La Operación Corredor comenzó el 14 de junio de 1992, cuando la 16.ª Brigada Motorizada Krajina del VRS, con la ayuda de una compañía de tanques del VRS de Doboj , comenzó la ofensiva cerca de Derventa . El VRS capturó Modriča el 28 de junio, Derventa el 4 y 5 de julio y Odžak el 12 de julio. Las fuerzas del HV-HVO se vieron reducidas a posiciones aisladas alrededor de Bosanski Brod y Orašje , que resistieron durante agosto y septiembre. El VRS logró atravesar sus líneas a principios de octubre y capturar Bosanski Brod. La mayoría de las fuerzas croatas restantes se retiraron al norte, a Croacia. El HV-HVO continuó manteniendo el enclave de Orašje y pudo repeler un ataque del VRS en noviembre. [190] El 21 de junio de 1992, las fuerzas bosnias entraron en la aldea serbobosnia de Ratkovići, cerca de Srebrenica, y asesinaron a 24 civiles serbios. [191]

En junio de 1992, la UNPROFOR, originalmente desplegada en Croacia, vio su mandato ampliado a Bosnia y Herzegovina, inicialmente para proteger el Aeropuerto Internacional de Sarajevo. [192] [193] En septiembre, el papel de la UNPROFOR se amplió para proteger la ayuda humanitaria y ayudar a la entrega de socorro en toda Bosnia y Herzegovina, así como para ayudar a proteger a los refugiados civiles cuando lo requiriera la Cruz Roja . [194]

El 4 de agosto de 1992, la IV Brigada Motorizada de Caballeros de la ARBiH intentó romper el cerco que rodeaba Sarajevo, y se produjo una feroz batalla entre la ARBiH y el VRS en la fábrica dañada de FAMOS y sus alrededores, en el suburbio de Hrasnica . El VRS repelió el ataque, pero no logró tomar Hrasnica en un contraataque decisivo. [195]

El 12 de agosto de 1992, el nombre de la República Serbia de Bosnia y Herzegovina pasó a ser República Srpska (RS). [81] [196] En noviembre de 1992, 1.000 kilómetros cuadrados (400 millas cuadradas) de Bosnia oriental estaban bajo control musulmán. [154]

La alianza croata-bosnia, formada al comienzo de la guerra, no siempre fue armoniosa. [2] La existencia de dos comandos paralelos causó problemas en la coordinación de los dos ejércitos contra el VRS. [197] Un intento de crear un cuartel general militar conjunto del HVO y el TO a mediados de abril fracasó. [198] El 21 de julio de 1992, Tuđman e Izetbegović firmaron el Acuerdo de Amistad y Cooperación , estableciendo una cooperación militar entre los dos ejércitos. [199] En una sesión celebrada el 6 de agosto, la Presidencia bosnia aceptó al HVO como parte integral de las fuerzas armadas bosnias. [200]

A pesar de estos intentos, las tensiones aumentaron constantemente durante la segunda mitad de 1992. [198] A principios de mayo se produjo un conflicto armado en Busovača y otro el 13 de junio. El 19 de junio, estalló un conflicto entre las unidades del TO por un lado y las unidades del HVO y el HOS por el otro en Novi Travnik. También se registraron incidentes en Konjic en julio y en Kiseljak y el asentamiento croata de Stup en Sarajevo durante agosto. [201] El 14 de septiembre, el Tribunal Constitucional de Bosnia y Herzegovina declaró inconstitucional la proclamación de Herzeg-Bosnia. [202]

El 18 de octubre, una disputa sobre una gasolinera compartida por ambos ejércitos cerca de Novi Travnik se convirtió en un conflicto armado en el centro de la ciudad. La situación empeoró después de que el comandante del HVO, Ivica Stojak, fuera asesinado cerca de Travnik el 20 de octubre. [203] El mismo día, los combates se intensificaron en un puesto de control de la ARBiH situado en la carretera principal que atraviesa el valle de Lašva. Los enfrentamientos espontáneos se extendieron por toda la región y provocaron casi 50 víctimas hasta que la UNPROFOR negoció un alto el fuego el 21 de octubre. [204] El 23 de octubre, comenzó una importante batalla entre la ARBiH y el HVO en la ciudad de Prozor, en el norte de Herzegovina, que dio como resultado una victoria del HVO. [205]

El 29 de octubre, el VRS capturó Jajce . La ciudad fue defendida tanto por el HVO como por la ARBiH, pero la falta de cooperación, así como una ventaja en tamaño de tropas y potencia de fuego para el VRS, llevaron a la caída de la ciudad. [206] [207] Los refugiados croatas de Jajce huyeron a Herzegovina y Croacia, mientras que alrededor de 20.000 refugiados bosnios se establecieron en Travnik, Novi Travnik, Vitez, Busovača y pueblos cerca de Zenica. [207] A pesar de los enfrentamientos de octubre, y con cada lado culpando al otro por la caída de Jajce, no hubo enfrentamientos a gran escala y una alianza militar general todavía estaba en vigor. [208] Tuđman e Izetbegović se reunieron en Zagreb el 1 de noviembre de 1992 y acordaron establecer un Comando Conjunto del HVO y la ARBiH. [209]

El 7 de enero de 1993, día de Navidad ortodoxa , la 8.ª Unidad Operativa Srebrenica, una unidad de la ARBiH bajo el mando de Naser Orić , atacó la aldea de Kravica cerca de Bratunac . 46 serbios murieron en el ataque: 35 soldados y 11 civiles. [210] [211] [212] 119 civiles serbios y 424 soldados serbios murieron en Bratunac durante la guerra. [212] La República Srpska afirmó que las fuerzas de la ARBiH incendiaron casas serbias y masacraron a civiles. Sin embargo, esto no pudo verificarse durante los juicios del TPIY, que concluyeron que muchas casas ya estaban destruidas y que el asedio de Srebrenica provocó hambre, obligando a los bosnios a atacar las aldeas serbias cercanas para adquirir alimentos para sobrevivir. En 2006, Orić fue declarado culpable por el TPIY de los cargos de no prevenir el asesinato de serbios, pero fue absuelto de todos los cargos en apelación. [213]

El 8 de enero de 1993, las fuerzas serbias mataron al viceprimer ministro del RBiH, Hakija Turajlić, después de detener el convoy de la ONU que lo transportaba desde el aeropuerto. [214] El 16 de enero de 1993, soldados del ARBiH atacaron la aldea serbia de Bosnia de Skelani , cerca de Srebrenica . [215] 69 personas murieron y 185 resultaron heridas. [215] Entre las víctimas había 6 niños. [216]

La ONU, los Estados Unidos y la Comunidad Europea (CE) propusieron planes de paz , pero tuvieron poco impacto en la guerra. Entre ellos se encontraba el Plan de Paz Vance-Owen , revelado en enero de 1993. [217] El plan fue presentado por el enviado especial de la ONU Cyrus Vance y el representante de la CE David Owen . Preveía a Bosnia y Herzegovina como un estado descentralizado con diez provincias autónomas. [218]

El 22 de febrero de 1993, el Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas aprobó la Resolución 808 "por la que se establece un tribunal internacional para el procesamiento de las personas responsables de violaciones graves del derecho internacional humanitario". [219] El 15 y 16 de mayo, el plan de paz Vance-Owen fue rechazado en un referéndum . [220] [221] Algunos consideraron que el plan de paz era uno de los factores que llevaron a la escalada del conflicto croata-bosnio en Bosnia central. [222]

El 31 de marzo de 1993, el Consejo de Seguridad emitió la Resolución 816 , instando a los Estados miembros a hacer cumplir una zona de exclusión aérea sobre Bosnia y Herzegovina. [223] El 12 de abril de 1993, la OTAN inició la Operación Deny Flight para hacer cumplir esta zona de exclusión aérea. [224] El 25 de mayo de 1993, el Tribunal Penal Internacional para la ex Yugoslavia (TPIY) fue establecido formalmente por la Resolución 827 del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas . [219]

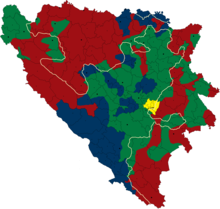

A finales de julio, los representantes de las tres facciones en pugna de Bosnia iniciaron una nueva ronda de negociaciones. El 20 de agosto, los mediadores de la ONU Thorvald Stoltenberg y David Owen mostraron un mapa que establecería el marco para la partición de Bosnia en tres estados étnicos. Los serbios de Bosnia recibirían el 52% del territorio de Bosnia, los musulmanes el 30% y los bosniocroatas el 18%. Alija Izetbegović rechazó el plan el 29 de agosto.

Gran parte de 1993 estuvo dominada por la guerra croata-bosnia . [209] A principios de enero, el HVO y la ARBiH se enfrentaron en Gornji Vakuf en Bosnia central. Se alcanzó un alto el fuego temporal después de días de combates, con la mediación de la UNPROFOR. [225] La guerra se extendió desde Gornji Vakuf a Busovača en la segunda mitad de enero. [226] Busovača era el principal punto de intersección de las líneas de comunicación en el valle de Lašva . El 26 de enero, la ARBiH tomó el control de las aldeas de la zona, incluidas Kaćuni y Bilalovac en la carretera Busovača-Kiseljak, aislando así a Kiseljak de Busovača. En el área de Kiseljak, la ARBiH aseguró las aldeas al noreste de la ciudad de Kiseljak, pero la mayor parte del municipio y la ciudad misma permanecieron bajo el control del HVO. [227] El 26 de enero, seis prisioneros de guerra y un civil serbio fueron asesinados por la ARBiH en la aldea de Dusina, al norte de Busovača. [228] Los combates en Busovača también provocaron bajas civiles bosnias. [229]

El 30 de enero, los líderes de la ARBiH y del HVO se reunieron en Vitez , junto con representantes de la UNPROFOR y otros observadores extranjeros, y firmaron un alto el fuego en la zona de Bosnia central, que entró en vigor al día siguiente. [230] La situación seguía tensa, por lo que Enver Hadžihasanović , comandante del 3.er Cuerpo de la ARBiH , y Tihomir Blaškić , comandante de la Zona Operativa de la HVO en Bosnia Central, se reunieron el 13 de febrero en la que se formó una comisión conjunta de la ARBiH y el HVO para resolver los incidentes. [231] El alto el fuego de enero en Bosnia central se mantuvo hasta principios de abril, a pesar de incidentes menores. [232] Los croatas atribuyeron la escalada del conflicto a la creciente política islámica de los bosnios, mientras que los bosnios acusaron al bando croata de separatismo. [15]

El comienzo de abril estuvo marcado por incidentes en Bosnia central entre civiles y soldados bosnios y croatas, incluidos asaltos, asesinatos y enfrentamientos armados. [233] Los más graves fueron el secuestro de cuatro miembros del HVO en las afueras de Novi Travnik y del comandante del HVO Živko Totić cerca de Zenica por parte de los muyahidines. Los representantes de la ARBiH negaron cualquier implicación y se formó una comisión conjunta de la ARBiH y el HVO para investigar. El personal del HVO fue posteriormente intercambiado en mayo por prisioneros de guerra que fueron arrestados por el HVO. [234] Los incidentes de abril se intensificaron hasta convertirse en un conflicto armado el 15 de abril en la zona de Vitez, Busovača, Kiseljak y Zenica. El HVO, superado en número en el municipio de Zenica, fue rápidamente derrotado, seguido de un éxodo de civiles croatas. [235]

En el municipio de Busovača, la ARBiH ganó algo de terreno e infligió fuertes bajas al HVO, pero el HVO mantuvo la ciudad de Busovača y la intersección de Kaonik entre Busovača y Vitez. [236] La ARBiH no logró dividir el enclave de Kiseljak en poder del HVO en partes más pequeñas ni aislar la ciudad de Fojnica de Kiseljak. [237] Muchos civiles bosnios fueron detenidos u obligados a abandonar Kiseljak. [238]

En la zona de Vitez, Blaškić utilizó sus limitadas fuerzas para llevar a cabo ataques de desmantelamiento contra la ARBiH, impidiendo así que la ARBiH cortara la carretera Travnik–Busovača y tomara la fábrica de explosivos SPS en Vitez. [239] El 16 de abril, el HVO lanzó un ataque de desmantelamiento contra Ahmići, al este de Vitez. Después de que las unidades atacantes rompieran las líneas de la ARBiH y entraran en el pueblo, grupos de unidades irregulares del HVO fueron de casa en casa, quemándolas y matando a civiles. Cuando las fuerzas croatas llegaron a Ahmići, dejaron a todos los croatas en paz, [240] y masacraron a los musulmanes que no pudieron huir a tiempo. [240] La masacre de Ahmići resultó en más de 100 civiles bosnios muertos. [240] [241] [242] La masacre fue descubierta por tropas de paz de la ONU del 1.er Batallón, Regimiento de Cheshire , [243] extraídas del Ejército británico , bajo el mando del coronel Bob Stewart . [244] [245] [246] El Gobierno bosnio hizo un monumento dedicado a las 116 víctimas. [240] En otras partes del área, el HVO bloqueó a las fuerzas de ARBiH en el barrio Stari Vitez de Vitez e impidió un avance de ARBiH al sur de la ciudad. [247] [248] El 24 de abril, fuerzas muyahidines atacaron a Miletići al noreste de Travnik y mataron a cuatro civiles croatas. [248] El resto de los civiles capturados fueron llevados al campamento de Poljanice. [228] [248] Sin embargo, el conflicto no se extendió a Travnik y Novi Travnik, aunque el HVO y la ARBiH trajeron refuerzos de esta zona. [249] El 25 de abril, Izetbegović y Boban firmaron un alto el fuego. [250] El Jefe de Estado Mayor de la ARBiH, Sefer Halilović , y el Jefe de Estado Mayor del HVO, Milivoj Petković , se reunieron semanalmente para resolver problemas e implementar el alto el fuego. [251] Sin embargo, la tregua no se respetó sobre el terreno y las fuerzas del HVO y la ARBiH siguieron comprometidas en la zona de Busovača hasta el 30 de abril. [236]

La guerra croata-bosnia se extendió desde Bosnia central hasta el norte de Herzegovina el 14 de abril con un ataque de la ARBiH a una aldea controlada por el HVO en las afueras de Konjic . El HVO respondió capturando tres aldeas al noreste de Jablanica . [252] El 16 de abril, la ARBiH mató a 15 civiles croatas y siete prisioneros de guerra en la aldea de Trusina , al norte de Jablanica. [253] Las batallas de Konjic y Jablanica duraron hasta mayo, y la ARBiH tomó el control de ambas ciudades y aldeas cercanas. [252]

A mediados de abril, Mostar se había convertido en una ciudad dividida, con la parte occidental, de mayoría croata, dominada por el HVO, y la parte oriental, de mayoría bosnia, dominada por la ARBiH. La batalla de Mostar comenzó el 9 de mayo, cuando tanto la parte este como la oeste de la ciudad quedaron bajo fuego de artillería. [254] Las batallas callejeras continuaron, a pesar de un alto el fuego firmado el 13 de mayo por Milivoj Petković y Sefer Halilović, hasta el 21 de mayo. [255] El HVO estableció campos de prisioneros en Dretelj, cerca de Čapljina, y en Heliodrom , [256] mientras que la ARBiH formó campos de prisioneros en Potoci y en una escuela en el este de Mostar. [257] La batalla se reanudó el 30 de junio. La ARBiH aseguró los accesos al norte de Mostar y el este de la ciudad, pero su avance hacia el sur fue repelido por el HVO. [258]

En la primera semana de junio, la ARBiH atacó el cuartel general del HVO en Travnik y las unidades del HVO situadas en las líneas del frente contra el VRS. Después de tres días de combates callejeros, las fuerzas del HVO, que eran inferiores en número, fueron derrotadas y miles de civiles y soldados croatas huyeron hacia territorios cercanos en poder de los serbios, ya que se les había cortado el acceso a las posiciones del HVO. La ofensiva de la ARBiH continuó al este de Travnik para asegurar la carretera a Zenica, lo que se logró el 14 de junio. [259] [260] El 8 de junio, los muyahidines mataron a 24 civiles y prisioneros de guerra croatas cerca de la aldea de Bikoši. [261]

En Novi Travnik se produjo un acontecimiento similar. El 9 de junio, la ARBiH atacó a las unidades del HVO situadas al este de la ciudad, enfrentándose al VRS en Donji Vakuf, y al día siguiente se produjeron combates en Novi Travnik. [262] El 15 de junio, la ARBiH había asegurado la zona al noroeste de la ciudad, mientras que el HVO conservaba la parte noreste del municipio y la ciudad de Novi Travnik. La batalla continuó hasta julio con apenas cambios menores en las líneas del frente. [263]

El HVO en la ciudad de Kakanj fue invadido a mediados de junio y alrededor de 13-15.000 refugiados croatas huyeron a Kiseljak y Vareš. [264] En el enclave de Kiseljak, el HVO resistió un ataque a Kreševo , pero perdió Fojnica el 3 de julio. [265] El 24 de junio, comenzó la Batalla de Žepče que terminó con una derrota de la ARBiH el 30 de junio. [266] A fines de julio, la ARBiH tomó el control de Bugojno , [264] lo que llevó a la partida de 15.000 croatas. [256] Se estableció un campo de prisioneros en el estadio de fútbol, donde fueron enviados alrededor de 800 croatas. [267]

A principios de septiembre, la ARBiH lanzó una operación conocida como Operación Neretva '93 contra el HVO en Herzegovina y Bosnia central, en un frente de 200 km de largo. Fue una de sus mayores ofensivas en 1993. La ARBiH expandió su territorio al oeste de Jablanica y aseguró la carretera hacia el este de Mostar, mientras que el HVO mantuvo el área de Prozor y aseguró la retaguardia de sus fuerzas en el oeste de Mostar. [268] Durante la noche del 8 al 9 de septiembre, al menos 13 civiles croatas fueron asesinados por la ARBiH en la masacre de Grabovica . 29 civiles croatas y un prisionero de guerra fueron asesinados en la masacre de Uzdol el 14 de septiembre. [269] [270]

El 23 de octubre, 37 bosnios fueron asesinados por el HVO en la masacre de Stupni Do. [271] Esto se utilizó como excusa para un ataque de la ARBiH contra el enclave de Vareš en poder del HVO a principios de noviembre . Los civiles y soldados croatas abandonaron Vareš el 3 de noviembre y huyeron a Kiseljak. La ARBiH entró en Vareš al día siguiente, que fue saqueada. [272]

En un intento de proteger a los civiles, el papel de la UNPROFOR se amplió en mayo de 1993 para proteger los "refugios seguros" que el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU había declarado alrededor de Sarajevo, Goražde , Srebrenica , Tuzla , Žepa y Bihać en la Resolución 824 del 6 de mayo de 1993. [273] El 4 de junio de 1993, el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU aprobó la Resolución 836 autorizando el uso de la fuerza por parte de la UNPROFOR en la protección de las zonas seguras. [274] El 15 de junio de 1993, comenzó la Operación Sharp Guard , un bloqueo naval en el mar Adriático por parte de la OTAN y la Unión Europea Occidental , que continuó hasta que se levantó en junio de 1996 al terminar el embargo de armas de la ONU. [274]

El HVO y la ARBiH siguieron luchando codo con codo contra el VRS en algunas zonas de Bosnia y Herzegovina, como el enclave de Bihać, la Posavina bosnia y la zona de Tešanj. A pesar de cierta animosidad, una brigada del HVO de unos 1.500 soldados luchó junto al ARBiH en Sarajevo. [275] [276] En otras zonas donde la alianza se derrumbó, el VRS cooperó ocasionalmente tanto con el HVO como con la ARBiH, siguiendo una política de equilibrio local y aliándose con el bando más débil. [277]

Las deportaciones forzadas de bosnios de los territorios ocupados por los serbios y la crisis de refugiados resultante continuaron aumentando. Miles de personas eran trasladadas en autobús fuera de Bosnia cada mes, amenazadas por motivos religiosos. Como resultado, Croacia se vio sometida a una gran presión por la llegada de 500.000 refugiados y, a mediados de 1994, las autoridades croatas prohibieron la entrada a un grupo de 462 refugiados que huían del norte de Bosnia, lo que obligó a la UNPROFOR a improvisar refugios para ellos. [278] Entre el 30 de marzo y el 23 de abril de 1994, los serbios lanzaron otra gran ofensiva contra la ciudad con el objetivo principal de invadir Goražde. El 9 de abril de 1994, el Secretario General de las Naciones Unidas , citando la Resolución de Seguridad 836 , amenazó con ataques aéreos contra las fuerzas serbias que estaban atacando el enclave de Goražde. Durante los dos días siguientes, los aviones de la OTAN llevaron a cabo ataques aéreos contra tanques y puestos de avanzada serbios. [279] Sin embargo, estos ataques no lograron detener al abrumador ejército serbio de Bosnia. [279] El ejército serbio de Bosnia rodeó a 150 soldados de la UNPROFOR y los tomó como rehenes en Goražde. [279] Sabiendo que Goražde caería a menos que hubiera una intervención extranjera, la OTAN lanzó un ultimátum a los serbios, que se vieron obligados a cumplir. Según las condiciones del ultimátum, los serbios tenían que retirar todas las milicias a 3 km de la ciudad antes del 23 de abril de 1994, y toda su artillería y vehículos blindados a 20 km de la ciudad antes del 26 de abril de 1994. El VRS cumplió. [280]

El 5 de febrero de 1994 , Sarajevo sufrió su ataque más mortífero de todo el asedio con la primera masacre de Markale , cuando un proyectil de mortero de 120 milímetros cayó en el centro de la abarrotada plaza del mercado, matando a 68 personas e hiriendo a otras 144. El 6 de febrero, el Secretario General de las Naciones Unidas , Boutros Boutros-Ghali, solicitó formalmente a la OTAN que confirmara que las futuras solicitudes de ataques aéreos se llevarían a cabo de inmediato. [281]

El 9 de febrero de 1994, la OTAN autorizó al Comandante de las Fuerzas Aliadas del Sur de Europa (CINCSOUTH), el almirante estadounidense Jeremy Boorda, a lanzar ataques aéreos —a petición de la ONU— contra posiciones de artillería y mortero en Sarajevo o sus alrededores que la UNPROFOR hubiera determinado que eran responsables de ataques contra objetivos civiles. [274] [282] Sólo Grecia no apoyó el uso de ataques aéreos, pero no vetó la propuesta. [281]

La OTAN también lanzó un ultimátum a los serbios de Bosnia exigiéndoles que retiraran las armas pesadas de los alrededores de Sarajevo antes de la medianoche del 20 al 21 de febrero, o de lo contrario se enfrentarían a ataques aéreos. El 12 de febrero, Sarajevo disfrutó de su primer día sin víctimas desde abril de 1992. [281] La retirada a gran escala de las armas pesadas de los serbios de Bosnia comenzó el 17 de febrero de 1994. [281]

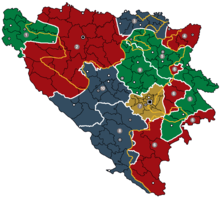

La guerra croata-bosnia terminó con la firma de un acuerdo de alto el fuego entre el Jefe de Estado Mayor del HVO, general Ante Roso, y el Jefe de Estado Mayor de la ARBiH, general Rasim Delić , el 23 de febrero de 1994 en Zagreb. El acuerdo entró en vigor el 25 de febrero. [283] [284] Un acuerdo de paz conocido como el Acuerdo de Washington , mediado por los EE. UU., fue concluido el 2 de marzo por representantes de la República de Bosnia y Herzegovina, Croacia y Herzeg-Bosnia. El acuerdo se firmó el 18 de marzo de 1994 en Washington. En virtud de este acuerdo, el territorio combinado en poder del HVO y la ARBiH se dividió en cantones autónomos dentro de la Federación de Bosnia y Herzegovina . Tuđman e Izetbegović también firmaron un acuerdo preliminar sobre una confederación entre Croacia y la Federación de Bosnia y Herzegovina. [285] [286] La alianza croata-bosnia se renovó, aunque no se resolvieron las cuestiones que los dividían. [284]

El primer esfuerzo militar coordinado entre el HVO y la ARBiH tras el Acuerdo de Washington fue el avance hacia Kupres , que fue recuperado del VRS el 3 de noviembre de 1994. [287] El 29 de noviembre, el HV y el HVO iniciaron la Operación Invierno '94 en el suroeste de Bosnia. Después de un mes de combates, las fuerzas croatas habían tomado alrededor de 200 kilómetros cuadrados (77 millas cuadradas) de territorio controlado por el VRS y amenazaban directamente la principal ruta de suministro entre la República Srpska y Knin , la capital de la República de la Krajina Serbia. El objetivo principal de aliviar la presión sobre el enclave de Bihać no se logró, aunque la ARBiH repelió los ataques del VRS al enclave. [288]

La OTAN se involucró activamente cuando sus aviones derribaron cuatro aviones serbios sobre Bosnia central el 28 de febrero de 1994 por violar la zona de exclusión aérea de la ONU. [289] El 12 de marzo de 1994, la Fuerza de Protección de las Naciones Unidas (UNPROFOR) hizo su primera solicitud de apoyo aéreo de la OTAN, pero no se desplegó apoyo aéreo cercano, debido a una serie de demoras asociadas con el proceso de aprobación. [290] El 20 de marzo, un convoy de ayuda con suministros médicos y médicos llegó a Maglaj , una ciudad de 100.000 habitantes, que había estado sitiada desde mayo de 1993 y había estado sobreviviendo gracias a los suministros de alimentos lanzados por aviones estadounidenses . Un segundo convoy el 23 de marzo fue secuestrado y saqueado. [285]

El 10 y 11 de abril de 1994, la UNPROFOR solicitó ataques aéreos para proteger la zona segura de Goražde , lo que resultó en el bombardeo de un puesto de mando militar serbio cerca de Goražde por dos aviones estadounidenses F-16 . [274] [279] [285] [290] Esta fue la primera vez en la historia de la OTAN que llevó a cabo ataques aéreos. [279] [285] En represalia, los serbios tomaron como rehenes a 150 miembros del personal de la ONU el 14 de abril. [274] [279] [290] El 15 de abril, las líneas del gobierno bosnio alrededor de Goražde se rompieron, [285] y el 16 de abril un Sea Harrier británico fue derribado sobre Goražde por fuerzas serbias.

Alrededor del 29 de abril de 1994, un contingente danés (Nordbat 2) en misión de mantenimiento de la paz en Bosnia , como parte del batallón nórdico de la UNPROFOR ubicado en Tuzla , fue emboscado cuando intentaba relevar un puesto de observación sueco (Tango 2) que estaba bajo intenso fuego de artillería por parte de la brigada serbobosnia Šekovići en la aldea de Kalesija . [291] La emboscada fue dispersada cuando las fuerzas de la ONU respondieron con intenso fuego en lo que se conocería como Operación Bøllebank .

El 12 de mayo, el Senado de los Estados Unidos adoptó la ley S. 2042, presentada por el senador Bob Dole , para levantar unilateralmente el embargo de armas contra los bosnios, pero fue repudiada por el presidente Clinton. [292] [293] El 5 de octubre de 1994, Pub. L. La resolución 103–337 fue firmada por el Presidente y establecía que si los serbios de Bosnia no habían aceptado la propuesta del Grupo de Contacto antes del 15 de octubre, el Presidente debería presentar una propuesta al Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU para poner fin al embargo de armas, y que si no se aprobaba antes del 15 de noviembre, solo los fondos requeridos por todos los miembros de la ONU bajo la Resolución 713 podrían usarse para hacer cumplir el embargo, lo que efectivamente pondría fin al embargo. [294] El 12 y 13 de noviembre, Estados Unidos levantó unilateralmente el embargo de armas contra el gobierno de Bosnia. [294] [295]

El 5 de agosto, a petición de la UNPROFOR, aviones de la OTAN atacaron un objetivo situado en la zona de exclusión de Sarajevo después de que los serbios de Bosnia se apoderaran de armas de un lugar de recogida de armas cerca de Sarajevo. El 22 de septiembre de 1994, aviones de la OTAN llevaron a cabo un ataque aéreo contra un tanque serbio de Bosnia a petición de la UNPROFOR. [274] La Operación Amanda fue una misión de la UNPROFOR dirigida por tropas danesas de mantenimiento de la paz, cuyo objetivo era recuperar un puesto de observación cerca de Gradačac (Bosnia y Herzegovina), el 25 de octubre de 1994. [296]

El 19 de noviembre de 1994, el Consejo del Atlántico Norte aprobó la ampliación del apoyo aéreo cercano a Croacia para la protección de las fuerzas de las Naciones Unidas en ese país. [274] El 21 de noviembre, aviones de la OTAN atacaron el aeródromo de Udbina , en Croacia bajo control serbio, en respuesta a los ataques lanzados desde ese aeródromo contra objetivos en la zona de Bihac, en Bosnia y Herzegovina. El 23 de noviembre, tras los ataques lanzados desde un emplazamiento de misiles tierra-aire al sur de Otoka (noroeste de Bosnia y Herzegovina) contra dos aviones de la OTAN, se realizaron ataques aéreos contra radares de defensa aérea en esa zona. [274]

El 25 de mayo de 1995, la OTAN bombardeó las posiciones del VRS en Pale debido a que no habían devuelto las armas pesadas. El VRS luego bombardeó todas las áreas seguras, incluida Tuzla . Aproximadamente 70 civiles murieron y 150 resultaron heridos. [297] [298] [299] [300] Durante abril y junio, las fuerzas croatas llevaron a cabo dos ofensivas conocidas como Leap 1 y Leap 2. Con estas ofensivas, aseguraron el resto del valle de Livno y amenazaron la ciudad de Bosansko Grahovo en poder del VRS . [301]

El 27 de mayo de 1995 se produjo un enfrentamiento en el puente de Vrbanja. Durante la batalla, elementos del ejército serbio de Bosnia asaltaron los puestos de observación de la UNPROFOR construidos por Francia y tomaron como rehenes a 10 soldados franceses. El ejército francés, dirigido por François Lecointre , envió unos 100 soldados de mantenimiento de la paz de las Naciones Unidas al puente, recuperó el puesto y poco después el VRS se retiró. [ cita requerida ]

On 11 July 1995, Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) forces under general Ratko Mladić occupied the UN "safe area" of Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia where more than 8,000 men were killed in the Srebrenica massacre (most women were expelled to Bosniak-held territory).[302][303] The United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR), represented on the ground by a 400-strong contingent of Dutch peacekeepers, Dutchbat, failed to prevent the town's capture by the VRS and the subsequent massacre.[304][305][306][307] The ICTY ruled this event as genocide in the Krstić case. On 25 July 1995, Serbs launched "Operation Stupčanica 95" to occupy the second UN "safe area", Žepa. UNPROFOR only sent 79 Ukrainian peacekeepers to Žepa.[308]

In line with the Split Agreement signed between Tuđman and Izetbegović on 22 July, a joint military offensive by the HV and the HVO codenamed Operation Summer '95 took place in western Bosnia. The HV-HVO force gained control of Glamoč and Bosansko Grahovo and isolated Knin from Republika Srpska.[309] On 4 August, the HV launched Operation Storm that effectively dissolved the Republic of Serbian Krajina.[310] With this, the Bosniak-Croat alliance gained the initiative in the war, taking much of western Bosnia from the VRS in several operations in September and October. In Novi Grad, Croatian forces launched Operation Una, which began on 18 September 1995, when HV crossed the Una river and entered Bosnia. In 2006, Croatian authorities began investigating allegations of war crimes committed during this operation, specifically the killing of 40 civilians in the Bosanska Dubica area by troops of the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Guards Brigade.[311]

The HV-HVO secured over 2,500 square kilometres (970 square miles) of territory during Operation Mistral 2, including the towns of Jajce, Šipovo and Drvar. At the same time, the ARBiH engaged the VRS further to the north in Operation Sana and captured several towns, including Bosanska Krupa, Bosanski Petrovac, Ključ and Sanski Most.[312] A VRS counteroffensive against the ARBiH in western Bosnia was launched on 23/24 September. Within two weeks the VRS was in the vicinity of the town of Ključ. The ARBiH requested Croatian assistance and on 8 October the HV-HVO launched Operation Southern Move under the overall command of HV Major General Ante Gotovina. The VRS lost the town of Mrkonjić Grad, while HVO units came within 25 kilometres (16 miles) south of Banja Luka.[313]

On 28 August, a VRS mortar attack on the Sarajevo Markale marketplace killed 43 people.[314][315] In response to the second Markale massacre, on 30 August, the Secretary General of NATO announced the start of Operation Deliberate Force, widespread airstrikes against Bosnian Serb positions supported by UNPROFOR rapid reaction force artillery attacks.[316][317] On 14 September 1995, the NATO air strikes were suspended to allow the implementation of an agreement with Bosnian Serbs for the withdrawal of heavy weapons from around Sarajevo.[318][319] Twelve days later, on 26 September, an agreement of further basic principles for a peace accord was reached in New York City between the foreign ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and the FRY.[320] A 60-day ceasefire came into effect on 12 October, and on 1 November peace talks began in Dayton, Ohio.[320] The war ended with the Dayton Peace Agreement signed on 21 November 1995; the final version of the peace agreement was signed 14 December 1995 in Paris.[321]

Following the Dayton Agreement, a NATO-led Implementation Force (IFOR) was deployed to Bosnia-Herzegovina. This 80,000 strong unit, was deployed in order to enforce the peace, as well as other tasks such as providing support for humanitarian and political aid, reconstruction, providing support for displaced civilians to return to their homes, collection of arms, and mine and unexploded ordnance clearing of the affected areas.[322]

Calculating the number of deaths resulting from the conflict has been subject to considerable, highly politicised debate, sometimes "fused with narratives about victimhood", from the political elites of various groups.[323] Estimates of the total number of casualties have ranged from 25,000 to 329,000. The variations are partly the result of the use of inconsistent definitions of who can be considered victims of the war, as some research calculated only direct casualties of military activity while other research included those who died from hunger, cold, disease or other war conditions. Early overcounts were also the result of many victims being entered in both civilian and military lists because little systematic coordination of those lists took place in wartime conditions. The death toll was originally estimated in 1994 at around 200,000 by Cherif Bassiouni, head of the UN expert commission investigating war crimes.[324]

Steven L. Burg and Paul S. Shoup, writing in 1999, observed about early high figures:

The figure of 200,000 (or more) dead, injured, and missing was frequently cited in media reports on the war in Bosnia as late as 1994. The October 1995 bulletin of the Bosnian Institute for Public Health of the Republic Committee for Health and Social Welfare gave the numbers as 146,340 killed, and 174,914 wounded on the territory under the control of the Bosnian army. Mustafa Imamovic gave a figure of 144,248 perished (including those who died from hunger or exposure), mainly Muslims. The Red Cross and the UNHCR have not, to the best of our knowledge, produced data on the number of persons killed and injured in the course of the war. A November 1995 unclassified CIA memorandum estimated 156,500 civilian deaths in the country (all but 10,000 of them in Muslim- or Croat-held territories), not including the 8,000 to 10,000 then still missing from Srebrenica and Zepa enclaves. This figure for civilian deaths far exceeded the estimate in the same report of 81,500 troops killed (45,000 Bosnian government; 6,500 Bosnian Croat; and 30,000 Bosnian Serb). [325]

In June 2007, the Sarajevo-based Research and Documentation Center published extensive research on the Bosnian war deaths, also called The Bosnian Book of the Dead, a database that initially revealed a minimum of 97,207 names of Bosnia and Herzegovina's citizens confirmed as killed or missing during the 1992–1995 war.[326][327] The head of the UN war crimes tribunal's Demographic Unit, Ewa Tabeau, has called it "the largest existing database on Bosnian war victims",[328] and it is considered the most authoritative account of human losses in the Bosnian war.[329] More than 240,000 pieces of data were collected, checked, compared and evaluated by an international team of experts in order to produce the 2007 list of 97,207 victims' names.[327]