La Guerra Polaco-Soviética [N 1] (14 de febrero de 1919 [3] – 18 de marzo de 1921) se libró principalmente entre la Segunda República Polaca y la República Socialista Federativa Soviética de Rusia , después de la Primera Guerra Mundial y la Revolución rusa , por territorios previamente controlados por el Imperio ruso y la monarquía de los Habsburgo .

Tras el colapso de las Potencias Centrales y el armisticio del 11 de noviembre de 1918 , la Rusia soviética de Vladímir Lenin anuló el Tratado de Brest-Litovsk y trasladó sus fuerzas hacia el oeste para recuperar las regiones del Ober Ost abandonadas por los alemanes. Lenin consideraba que la recién independizada Polonia era una ruta fundamental para la propagación de las revoluciones comunistas en Europa . [16] Mientras tanto, los líderes polacos, incluido Józef Piłsudski , tenían como objetivo restaurar las fronteras de Polonia anteriores a 1772 y asegurar la posición del país en la región. A lo largo de 1919, las fuerzas polacas ocuparon gran parte de las actuales Lituania y Bielorrusia , y salieron victoriosas de la guerra polaco-ucraniana . Sin embargo, las fuerzas soviéticas recuperaron fuerza después de sus victorias en la guerra civil rusa , y Symon Petliura , líder de la República Popular de Ucrania , se vio obligado a aliarse con Piłsudski en 1920 para resistir el avance de los bolcheviques.

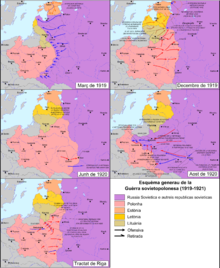

En abril de 1920, Piłsudski lanzó la ofensiva de Kiev con el objetivo de asegurar fronteras favorables para Polonia. El 7 de mayo, las fuerzas polacas y ucranianas aliadas capturaron Kiev , aunque los ejércitos soviéticos en el área no fueron derrotados decisivamente. La ofensiva carecía de apoyo local y muchos ucranianos se unieron al Ejército Rojo en lugar de a las fuerzas de Petliura. En respuesta, el Ejército Rojo soviético lanzó una contraofensiva exitosa que comenzó en junio de 1920. En agosto, las tropas soviéticas habían hecho retroceder a las fuerzas polacas a Varsovia . Sin embargo, en la decisiva Batalla de Varsovia (1920) , las fuerzas polacas lograron una victoria inesperada entre el 12 y el 25 de agosto de 1920, cambiando el rumbo de la guerra. Esta batalla, a menudo denominada el "Milagro del Vístula", se considera uno de los triunfos militares más importantes de la historia de Polonia.

La guerra terminó con un alto el fuego el 18 de octubre de 1920, y las negociaciones de paz condujeron a la Paz de Riga , firmada el 18 de marzo de 1921. El tratado dividió los territorios en disputa entre Polonia y la Rusia soviética. La frontera oriental de Polonia se estableció a unos 200 km al este de la Línea Curzon , asegurando el control polaco sobre partes de las actuales Ucrania y Bielorrusia . La guerra resultó en el reconocimiento oficial de la República Socialista Soviética de Ucrania y la República Socialista Soviética de Bielorrusia como estados soviéticos, socavando las ambiciones de Piłsudski de una federación intermarium liderada por Polonia. A pesar de esto, el éxito de Polonia en la Batalla de Varsovia consolidó su posición como un actor importante en la geopolítica de Europa del Este en el período de entreguerras.

La guerra se conoce por varios nombres. El más común es "guerra polaco-soviética", pero también se la conoce como "guerra ruso-polaca" (o "guerra polaco-rusa") y "guerra polaco-bolchevique". [4] Este último término (o simplemente "guerra bolchevique" ( en polaco : Wojna bolszewicka )) es el más común en las fuentes polacas. En algunas fuentes polacas también se la denomina "guerra de 1920" ( en polaco : Wojna 1920 roku ). [N 2]

El año final del conflicto se da de diversas maneras, ya sea 1920 o 1921; esta confusión se debe al hecho de que, si bien el alto el fuego entró en vigor el 18 de octubre de 1920, el tratado oficial que puso fin a la guerra se firmó el 18 de marzo de 1921. Si bien los eventos de finales de 1918 y 1919 pueden describirse como un conflicto fronterizo y solo en la primavera de 1920 ambos lados se involucraron en una guerra total , la guerra que tuvo lugar a fines de abril de 1920 fue una escalada de los combates que habían comenzado un año y medio antes. [2]

Los principales territorios en disputa durante la guerra se encuentran en lo que hoy es Ucrania y Bielorrusia . Hasta mediados del siglo XIII, formaban parte del estado medieval de la Rus de Kiev . Después de un período de guerras internas y la invasión mongola de 1240 , las tierras se convirtieron en objetos de expansión para el Reino de Polonia y para el Gran Ducado de Lituania . En la primera mitad del siglo XIV, el Principado de Kiev y las tierras entre los ríos Dniéper , Prípiat y Daugava (Dvina occidental) pasaron a formar parte del Gran Ducado de Lituania. En 1352, Polonia y Lituania se dividieron el Reino de Galicia-Volinia entre ellos. En 1569, de acuerdo con los términos de la Unión de Lublin entre Polonia y Lituania, algunas de las tierras ucranianas pasaron a la Corona polaca . Entre 1772 y 1795, muchos de los territorios eslavos orientales pasaron a formar parte del Imperio ruso en el curso de las Particiones de Polonia-Lituania . En 1795 (la Tercera Partición de Polonia ), Polonia perdió su independencia formal. Después del Congreso de Viena de 1814-1815, gran parte del territorio del Ducado de Varsovia fue transferido a control ruso y se convirtió en el Congreso de Polonia autónomo (oficialmente el Reino de Polonia). [17] Después de que los jóvenes polacos se negaran a alistarse en el Ejército Imperial Ruso durante el Levantamiento de Enero de 1863, el zar Alejandro II despojó al Congreso de Polonia de su constitución separada, intentó forzar el uso general del idioma ruso y le quitó vastas extensiones de tierra a los polacos. El Congreso de Polonia se incorporó más directamente a la Rusia imperial al ser dividido en diez provincias, cada una con un gobernador militar ruso designado y todas bajo el control completo del Gobernador General ruso en Varsovia. [18] [19]

Tras la Primera Guerra Mundial , el mapa de Europa central y oriental cambió drásticamente. La derrota del Imperio alemán dejó obsoletos los planes de Berlín para la creación de estados dominados por Alemania en Europa del Este ( Mitteleuropa ), que incluían otra rendición del Reino de Polonia . El Imperio ruso colapsó, lo que resultó en la Revolución rusa y la Guerra Civil rusa . El estado ruso perdió territorio debido a la ofensiva alemana y al Tratado de Brest-Litovsk , firmado por la emergente República Socialista Federativa Soviética de Rusia . Varias naciones de la región vieron una oportunidad para la independencia y aprovecharon su oportunidad para obtenerla. La derrota de Alemania en el frente occidental y la retirada del Ejército Imperial Alemán en el frente oriental habían dejado a Berlín sin posición para tomar represalias contra la Rusia soviética, que rápidamente repudió el tratado y procedió a recuperar muchos de los antiguos territorios del Imperio ruso. [20] Sin embargo, preocupado por la guerra civil, no tenía los recursos para reaccionar rápidamente a las rebeliones nacionales. [20]

En noviembre de 1918, Polonia se convirtió en un estado soberano . Entre las diversas guerras fronterizas libradas por la Segunda República Polaca estuvo el exitoso levantamiento de la Gran Polonia (1918-1919) contra la Alemania de Weimar . La histórica Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania incluía vastos territorios en el este. Habían sido incorporados al Imperio ruso entre 1772 y 1795 y habían permanecido como partes de éste, como el Territorio del Noroeste , hasta la Primera Guerra Mundial . [21] Después de la guerra fueron disputados por los intereses polacos, rusos, ucranianos, bielorrusos, lituanos y letones .

En la recién independizada Polonia, la política estuvo fuertemente influenciada por Józef Piłsudski . El 11 de noviembre de 1918, Piłsudski fue nombrado jefe de las fuerzas armadas polacas por el Consejo de Regencia del Reino de Polonia, un organismo instalado por las Potencias Centrales . Posteriormente, fue reconocido por muchos políticos polacos como jefe de Estado temporal y ejerció en la práctica amplios poderes. Bajo la Pequeña Constitución del 20 de febrero de 1919, se convirtió en jefe de Estado . Como tal, reportaba al Sejm legislativo . [22]

Con el colapso de las autoridades de ocupación rusas y alemanas , prácticamente todos los vecinos de Polonia comenzaron a luchar por las fronteras y otros asuntos. La Guerra Civil Finlandesa , la Guerra de Independencia de Estonia , la Guerra de Independencia de Letonia y las Guerras de Independencia de Lituania se libraron en la región del Mar Báltico . [23] Rusia se vio abrumada por las luchas internas. A principios de marzo de 1919, se estableció la Internacional Comunista en Moscú . La República Soviética de Hungría se proclamó en marzo y la República Soviética de Baviera en abril. [24] [25] Winston Churchill , en una conversación con el Primer Ministro David Lloyd George , comentó sarcásticamente: "La guerra de gigantes ha terminado, comienzan las guerras de los pigmeos". [26] [27] La Guerra Polaco-Soviética fue la más duradera de los enfrentamientos internacionales.

El territorio de lo que se había convertido en Polonia había sido un importante campo de batalla durante la Primera Guerra Mundial y el nuevo país carecía de estabilidad política. Había ganado la reñida guerra polaco-ucraniana contra la República Popular de Ucrania Occidental en julio de 1919, pero ya se había visto envuelto en nuevos conflictos con Alemania (los Levantamientos de Silesia de 1919-1921 ) y el conflicto fronterizo de enero de 1919 con Checoslovaquia . Mientras tanto, la Rusia soviética se centró en frustrar la contrarrevolución y la intervención de las potencias aliadas de 1918-1925 . Los primeros enfrentamientos entre las fuerzas polacas y soviéticas ocurrieron en otoño e invierno de 1918/1919, pero tardó un año y medio en desarrollarse una guerra a gran escala. [4]

Las potencias occidentales consideraban que cualquier expansión territorial significativa de Polonia, a expensas de Rusia o Alemania, sería sumamente perjudicial para el orden posterior a la Primera Guerra Mundial. Entre otros factores, los aliados occidentales no querían darle a Alemania y Rusia una razón para conspirar juntas. [28] El ascenso del régimen bolchevique no reconocido complicó esta lógica. [29]

El Tratado de Versalles , firmado el 28 de junio de 1919, reguló la frontera occidental de Polonia. [30] La Conferencia de Paz de París (1919-1920) no había tomado una decisión definitiva con respecto a la frontera oriental de Polonia, pero el 8 de diciembre de 1919, el Consejo Supremo de Guerra Aliado emitió un límite provisional (su versión posterior se conocería como la Línea Curzon ). [29] Fue un intento de definir las áreas que tenían una "indiscutible mayoría étnica polaca". [30] [31] [32] La frontera permanente dependía de las futuras negociaciones de las potencias occidentales con la Rusia Blanca , que se presumía que prevalecería en la Guerra Civil Rusa. [29] Piłsudski y sus aliados culparon al primer ministro Ignacy Paderewski por este resultado y provocaron su despido. Paderewski, amargado, se retiró de la política. [32]

El líder del nuevo gobierno bolchevique de Rusia, Vladimir Lenin , tenía como objetivo recuperar el control de los territorios abandonados por Rusia en el Tratado de Brest-Litovsk en marzo de 1918 (el tratado fue anulado por Rusia el 1 de marzo de 1918).13 de noviembre de 1918)[33] y establecer gobiernos soviéticos en los países emergentes en las partes occidentales del antiguo Imperio Ruso. El objetivo más ambicioso era también llegar a Alemania, donde esperaba que estallara una revolución socialista . A finales del verano de 1919, los soviéticos habían tomado la mayor parte del este y centro de Ucrania (antiguamente partes del Imperio Ruso) y expulsado al Directorio de Ucrania de Kiev . En febrero de 1919, establecieron la República Socialista Soviética de Lituania y Bielorrusia (Litbel). Sin embargo, es poco probable que la fuerza soviética planeara más incursiones hacia el oeste. [34]

A fines de 1919, Lenin, alentado por las victorias del Ejército Rojo en la guerra civil sobre las fuerzas rusas blancas y sus aliados occidentales, comenzó a vislumbrar el futuro de la revolución mundial con mayor optimismo. Los bolcheviques proclamaron la necesidad de la dictadura del proletariado y promovieron una comunidad comunista mundial. Tenían la intención de vincular la revolución en Rusia con la revolución comunista que habían deseado y ayudar a otros movimientos comunistas en Europa. Para poder brindar apoyo físico directo a los revolucionarios en Occidente, el Ejército Rojo tendría que cruzar el territorio de Rumania. [35]

Sin embargo, según el historiador Andrzej Chwalba , el escenario era diferente a finales de 1919 y en el invierno-primavera de 1920. Los soviéticos, ante la disminución del fervor revolucionario en Europa y teniendo que lidiar con los propios problemas de Rusia, intentaron hacer las paces con sus vecinos, incluida Polonia. [36]

Según Aviel Roshwald , (Piłsudski) "esperaba incorporar la mayoría de los territorios de la extinta Mancomunidad Polaca-Lituana al futuro estado polaco estructurándolo como una federación multinacional liderada por Polonia". [37] Piłsudski había querido romper el Imperio ruso y establecer la federación Intermarium de varios estados diferentes: Polonia, Lituania, Bielorrusia, Ucrania y otros países de Europa central y oriental que surgieron de los imperios en desmoronamiento después de la Primera Guerra Mundial. En la visión de Piłsudski, Polonia reemplazaría a una Rusia truncada y enormemente reducida como la gran potencia de Europa del Este. Su plan excluía las negociaciones antes de la victoria militar. [38] [39] [ 40] [41] [42] [43] Había esperado que la nueva unión liderada por Polonia se convirtiera en un contrapeso a cualquier intención imperialista potencial de Rusia o Alemania. [44] Piłsudski creía que no podía haber una Polonia independiente sin una Ucrania libre del control ruso, por lo que su principal interés era separar a Ucrania de Rusia. [45] [46] Utilizó la fuerza militar para expandir las fronteras polacas en Galicia y Volinia y aplastar un intento ucraniano de autodeterminación en los territorios en disputa al este de la Línea Curzon, que contenían una minoría polaca significativa. [16] El 7 de febrero de 1919, Piłsudski habló sobre el tema de las futuras fronteras de Polonia:

"En la actualidad, Polonia no tiene fronteras y todo lo que podamos ganar en este sentido en el oeste depende de la Entente , de hasta qué punto quiera presionar a Alemania. En el este, es otra cosa: aquí hay puertas que se abren y se cierran y depende de quién las abra a la fuerza y hasta qué punto". [47] [48]

Las fuerzas militares polacas se habían propuesto expandirse hacia el este. Como imaginaba Piłsudski,

"Rusia, encerrada en los límites del siglo XVI, aislada del mar Negro y del mar Báltico, privada de las tierras y de las riquezas minerales del sur y del sudeste, podía fácilmente ascender a la categoría de potencia de segundo orden. Polonia, como el mayor y más fuerte de los nuevos estados, podía fácilmente establecer una esfera de influencia que se extendiera desde Finlandia hasta el Cáucaso ". [49]

Los conceptos de Piłsudski parecían más progresistas y democráticos en comparación con los planes de la Democracia Nacional rival, [41] [50] [51] aunque ambos perseguían la idea de la incorporación directa y la polonización de las tierras orientales en disputa. [52] Sin embargo, Piłsudski utilizó su idea de "federación" de manera instrumental. Como le escribió a su estrecho colaborador Leon Wasilewski en abril de 1919, (por ahora)

"No quiero ser ni imperialista ni federalista... Teniendo en cuenta que en este mundo de Dios parece que triunfan tanto las palabras vacías sobre la fraternidad de los pueblos y las naciones como las pequeñas doctrinas norteamericanas, me pongo gustoso de parte de los federalistas". [51]

Según Chwalba, las diferencias entre la visión de Polonia de Piłsudski y la de su rival, el líder nacionaldemócrata Roman Dmowski, eran más retóricas que reales. Piłsudski había hecho muchas declaraciones confusas, pero nunca expresó específicamente sus opiniones sobre las fronteras orientales de Polonia o los acuerdos políticos que pretendía para la región. [53]

A finales de 1917 se formaron en Rusia unidades militares revolucionarias polacas , que se fusionaron en la División de Fusileros Occidental en octubre de 1918. En el verano de 1918 se creó en Moscú un gobierno comunista polaco de corta duración , dirigido por Stefan Heltman. Tanto las estructuras militares como las civiles tenían como objetivo facilitar la eventual introducción del comunismo en Polonia en forma de una República Soviética Polaca . [54]

Dada la precaria situación resultante de la retirada de las fuerzas alemanas de Bielorrusia y Lituania y la esperada llegada del Ejército Rojo a esas zonas, en otoño de 1918 se organizaron las Autodefensas Polacas en torno a las principales concentraciones de población polaca, como Minsk , Vilna y Grodno . Se basaron en la Organización Militar Polaca y fueron reconocidas como parte de las Fuerzas Armadas Polacas por decreto del Jefe de Estado polaco Piłsudski, emitido el 7 de diciembre de 1918. [55] [56]

El Soldatenrat alemán del Ober Ost declaró el 15 de noviembre que su autoridad en Vilnius sería transferida al Ejército Rojo. [33]

A finales de otoño de 1918, la 4.ª División de Fusileros de Polonia luchó contra el Ejército Rojo en Rusia. La división operaba bajo la autoridad del Ejército polaco en Francia y del general Józef Haller . Políticamente, la división luchaba bajo el mando del Comité Nacional Polaco (KNP), reconocido por los aliados como un gobierno temporal de Polonia. En enero de 1919, por decisión de Piłsudski, la 4.ª División de Fusileros pasó a formar parte del Ejército polaco. [3]

Las fuerzas de autodefensa polacas fueron derrotadas por los soviéticos en varios lugares. [54] Minsk fue tomada por el ejército occidental ruso el 11 de diciembre de 1918. [57] La República Socialista Soviética de Bielorrusia fue declarada allí el 31 de diciembre. Después de tres días de duros combates con la División de Fusileros Occidental, las unidades de autodefensa se retiraron de Vilna el 5 de enero de 1919. Las escaramuzas polaco-soviéticas continuaron en enero y febrero. [55]

Las fuerzas armadas polacas se formaron rápidamente para luchar en varias guerras fronterizas. Dos formaciones principales ocuparon el frente ruso en febrero de 1919: la del norte, dirigida por el general Wacław Iwaszkiewicz-Rudoszański , y la del sur, bajo el mando del general Antoni Listowski . [54]

El 18 de octubre de 1918 se formó el Consejo Nacional Ucraniano en Galitzia Oriental , todavía parte del Imperio austrohúngaro ; estaba dirigido por Yevhen Petrushevych . El establecimiento de un estado ucraniano allí se proclamó en noviembre de 1918; se lo conoció como la República Popular de Ucrania Occidental y reclamó a Lviv como su capital. [58] Debido a consideraciones políticas relacionadas con Rusia, los intentos ucranianos de generar el apoyo de las potencias de la Entente no lograron obtenerlo . [59]

El 31 de octubre de 1918, los ucranianos tomaron posesión de los edificios más importantes de Lviv. El 1 de noviembre, los residentes polacos de la ciudad contraatacaron y comenzó la guerra polaco-ucraniana. [59] Lviv quedó bajo control polaco desde el 22 de noviembre. [60] Para los políticos polacos, la reivindicación polaca sobre Lviv y la Galicia oriental era indiscutible; en abril de 1919, el Sejm legislativo declaró por unanimidad que toda la Galicia debía ser anexada a Polonia. [61] Entre abril y junio de 1919, el Ejército Azul polaco del general Józef Haller llegó desde Francia . Estaba formado por más de 67.000 soldados bien equipados y altamente entrenados. [62] El Ejército Azul ayudó a expulsar a las fuerzas ucranianas hacia el este más allá del río Zbruch y contribuyó decisivamente al resultado de la guerra. La República Popular de Ucrania Occidental fue derrotada a mediados de julio y la Galicia oriental quedó bajo administración polaca. [59] [60] La destrucción de la República de Ucrania Occidental confirmó la creencia de muchos ucranianos de que Polonia era el principal enemigo de su nación. [63]

A partir de enero de 1919 también se produjeron combates en Volinia, donde los polacos se enfrentaron a las fuerzas de la República Popular de Ucrania dirigidas por Symon Petliura . La ofensiva polaca dio como resultado la toma de la parte occidental de la provincia. [48] [64] La guerra polaco-ucraniana allí se interrumpió a partir de finales de mayo y a principios de septiembre se firmó un armisticio. [48] [64]

El 21 de noviembre de 1919, después de polémicas deliberaciones, el Consejo Supremo de Guerra Aliado otorgó a Polonia el control sobre Galicia oriental durante 25 años, con garantías de autonomía para la población ucraniana. [60] [50] La Conferencia de Embajadores , que reemplazó al Consejo Supremo de Guerra, reconoció el reclamo polaco sobre Galicia oriental en marzo de 1923. [50] [65]

Jan Kowalewski , un criptógrafo aficionado y políglota , descifró los códigos y cifras del ejército de la República Popular de Ucrania Occidental y de las fuerzas rusas blancas del general Anton Denikin . [66] [67] En agosto de 1919, se convirtió en jefe de la sección de criptografía del Estado Mayor polaco en Varsovia. [68] A principios de septiembre, había reunido a un grupo de matemáticos de la Universidad de Varsovia y la Universidad de Lwów (en particular, los fundadores de la Escuela Polaca de Matemáticas : Stanisław Leśniewski , Stefan Mazurkiewicz y Wacław Sierpiński ), que también lograron descifrar los códigos rusos soviéticos. Durante la guerra polaco-soviética, el descifrado polaco de los mensajes de radio del Ejército Rojo hizo posible utilizar las fuerzas militares polacas de manera eficiente contra las fuerzas rusas soviéticas y ganar muchas batallas individuales, la más importante de las cuales fue la Batalla de Varsovia . [66] [67]

El 5 de enero de 1919, el Ejército Rojo tomó Vilna, lo que llevó al establecimiento de la República Socialista Soviética de Lituania y Bielorrusia (Litbel) el 28 de febrero. [21] [23] El 10 de febrero, el Comisario del Pueblo de Asuntos Exteriores de la Rusia Soviética, Georgy Chicherin , escribió al Primer Ministro polaco Ignacy Paderewski, proponiendo la resolución de los asuntos en desacuerdo y el establecimiento de relaciones entre los dos estados. Fue una de las series de notas intercambiadas por los dos gobiernos en 1918 y 1919. [69]

En febrero, las tropas polacas marcharon hacia el este para enfrentarse a los soviéticos; el nuevo Sejm polaco declaró la necesidad de liberar "las provincias del noreste de Polonia con su capital en Wilno [Vilna]". [21] Después de que las tropas alemanas de la Primera Guerra Mundial hubieran sido evacuadas de la región, tuvo lugar la Batalla de Bereza Kartuska , una escaramuza polaco-soviética. [70] Ocurrió durante una acción ofensiva local polaca del 13 al 16 de febrero, dirigida por el general Antoni Listowski, cerca de Byaroza , Bielorrusia. [4] [2] [16] [70] [71] El evento ha sido presentado como el comienzo de la guerra de liberación por parte de Polonia, o de la agresión polaca por parte de Rusia. [70] A finales de febrero, la ofensiva soviética hacia el oeste se había detenido. Mientras continuaba la guerra de bajo nivel, las unidades polacas cruzaron el río Niemen , tomaron Pinsk el 5 de marzo y llegaron a las afueras de Lida ; el 4 de marzo, [ ¿ período de tiempo? ] Piłsudski ordenó detener el movimiento hacia el este. [72] [70] El liderazgo soviético se había preocupado por la cuestión de proporcionar asistencia militar a la República Soviética Húngara y con la ofensiva siberiana del Ejército Blanco , liderado por Alexander Kolchak . [73]

En julio de 1919, los ejércitos polacos eliminaron la República Popular de Ucrania Occidental. [32] A principios de abril, Piłsudski preparó en secreto un asalto a Vilna, ocupada por los soviéticos, y logró trasladar algunas de las fuerzas empleadas en Ucrania al frente norte. La idea era crear un hecho consumado e impedir que las potencias occidentales concedieran los territorios reclamados por Polonia a la Rusia Blanca (se esperaba que los blancos prevalecieran en la guerra civil rusa). [74]

El 16 de abril se inició una nueva ofensiva polaca. [4] [48] [74] Cinco mil soldados, liderados por Piłsudski, se dirigieron a Vilna. [75] Avanzando hacia el este, las fuerzas polacas tomaron Lida el 17 de abril, Novogrudok el 18 de abril, Baranavichy el 19 de abril y Grodno el 28 de abril. [76] El grupo de Piłsudski entró en Vilna el 19 de abril y capturó la ciudad después de dos días de combates. [48] [76] La acción polaca expulsó al gobierno de Litbel de su proclamada capital. [21] [16]

Tras la toma de Vilna, en pos de sus objetivos de federación, Piłsudski emitió una "Proclamación a los habitantes del antiguo Gran Ducado de Lituania" el 22 de abril. Esta fue duramente criticada por sus rivales Demócratas Nacionales, que exigieron la incorporación directa de las tierras del antiguo Gran Ducado a Polonia y manifestaron su oposición a los conceptos territoriales y políticos de Piłsudski. De este modo, Piłsudski había procedido a restaurar los territorios históricos de la Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania por medios militares, dejando las determinaciones políticas necesarias para más adelante. [48] [74]

El 25 de abril, Lenin ordenó al comandante del Frente Occidental que recuperara Vilna lo antes posible. Las formaciones del Ejército Rojo que atacaron a las fuerzas polacas fueron derrotadas por las unidades de Edward Rydz-Śmigły entre el 30 de abril y el 7 de mayo. [74] [77] Mientras los polacos ampliaban sus posiciones, el Ejército Rojo, incapaz de lograr sus objetivos y enfrentándose a un combate intensificado con las fuerzas blancas en otros lugares, se retiró de sus posiciones. [74]

El « Frente Lituano-Bielorruso » polaco se creó el 15 de mayo y quedó bajo el mando del general Stanisław Szeptycki . [70]

En un estatuto aprobado el 15 de mayo, el Sejm polaco pidió la inclusión de las naciones fronterizas del este en el estado polaco como entidades autónomas. El objetivo era causar una impresión positiva en los participantes en la Conferencia de Paz de París. En la conferencia, el Primer Ministro y Ministro de Asuntos Exteriores, Ignacy Paderewski, declaró el apoyo de Polonia a la autodeterminación de las naciones del este, en consonancia con la doctrina de Woodrow Wilson y en un esfuerzo por asegurar el apoyo occidental a las políticas de Polonia con respecto a Ucrania, Bielorrusia y Lituania. [78]

La ofensiva polaca se interrumpió en torno a la línea de trincheras y fortificaciones alemanas de la Primera Guerra Mundial, debido a la alta probabilidad de una guerra de Polonia con la Alemania de Weimar por cuestiones territoriales y de otro tipo. A mediados de junio, la mitad de la fuerza militar de Polonia se había concentrado en el frente alemán. La ofensiva en el este se reanudó a fines de junio, tras el Tratado de Versalles. El tratado, firmado y ratificado por Alemania, preservó el statu quo en el oeste de Polonia. [79]

En el frente sur de Volinia, en mayo y julio las fuerzas polacas se enfrentaron al Ejército Rojo, que estaba expulsando a las unidades ucranianas de Petliura de los territorios en disputa. La población rural ortodoxa de la zona era hostil a las autoridades polacas y apoyaba activamente a los bolcheviques. [64] También en Podolia y cerca de los confines orientales de Galicia, los ejércitos polacos siguieron avanzando lentamente hacia el este hasta diciembre. Cruzaron el río Zbruch y desplazaron a las fuerzas soviéticas de varias localidades. [64]

Las fuerzas polacas tomaron Minsk el 8 de agosto. [4] [80] El 18 de agosto se alcanzó el río Berezina . [80] El 28 de agosto se desplegaron tanques por primera vez y se capturó la ciudad de Babruysk . [4] [80] El 2 de septiembre, las unidades polacas alcanzaron el río Daugava. [4] Barysaw fue tomada el 10 de septiembre y partes de Polotsk el 21 de septiembre. [80] A mediados de septiembre, los polacos aseguraron la región a lo largo del Daugava desde el río Dysna hasta Daugavpils . [4] La línea del frente también se había extendido hacia el sur, atravesando Polesia y Volhynia; [74] [80] a lo largo del río Zbruch llegó a la frontera rumana . [74] Un asalto del Ejército Rojo entre los ríos Daugava y Berezina fue repelido en octubre y el frente se había vuelto relativamente inactivo con solo encuentros esporádicos, ya que se alcanzó la línea designada por Piłsudski como el objetivo de la operación polaca en el norte. [74] [80]

En otoño de 1919, el Sejm votó incorporar a Polonia los territorios conquistados hasta los ríos Daugava y Berezina, incluido Minsk. [81]

Los éxitos polacos en el verano de 1919 fueron el resultado de que los soviéticos dieron prioridad a la guerra contra las fuerzas blancas, que era más crucial para ellos. Los éxitos crearon una ilusión de destreza militar polaca y de debilidad soviética. [82] Como dijo Piłsudski, "no me preocupa la fuerza de Rusia; si quisiera, podría ir ahora, digamos a Moscú, y nadie sería capaz de resistir mi poder...". [83] La ofensiva fue frenada a finales del verano por Piłsudski, porque no quería mejorar la situación estratégica de los blancos que avanzaban. [82]

A principios del verano de 1919, el movimiento blanco había ganado la iniciativa y sus fuerzas, comandadas por Anton Denikin y conocidas como el Ejército Voluntario , marcharon sobre Moscú. Piłsuski se negó a unirse a la intervención aliada en la guerra civil rusa porque consideraba que los blancos eran una mayor amenaza para Polonia que los bolcheviques. [48] [84] La relación adversaria de Piłsudski con la Rusia zarista se remontaba a las primeras etapas de su carrera. Participó en la guerra con la Rusia soviética desde el comienzo de su mandato como comandante en jefe polaco. [85] Basándose en esta experiencia, subestimó la fuerza de los bolcheviques. [84] Piłsudski también pensó que podía obtener un mejor trato para Polonia de los bolcheviques que de los blancos, [86] que representaban, en su opinión, las antiguas políticas imperiales rusas, hostiles a una Polonia fuerte y a una Ucrania independiente de Rusia, los principales objetivos de Piłsudski. [87] Los bolcheviques habían proclamado que las particiones de Polonia eran inválidas y declararon su apoyo a la autodeterminación de la nación polaca. [88] [89] Piłsudski especuló que Polonia estaría mejor con los bolcheviques internacionalistas , que también estaban alejados de las potencias occidentales, que con el restaurado Imperio ruso, su nacionalismo tradicional y su asociación con la política occidental. [63] [86] [90] Con su negativa a unirse al ataque al gobierno en dificultades de Lenin, ignoró la fuerte presión de los líderes de la Triple Entente y posiblemente salvó al gobierno bolchevique en el verano y el otoño de 1919, [91] aunque un ataque a gran escala por parte de los polacos para apoyar a Denikin no habría sido posible. [92] Mikhail Tukhachevsky comentó más tarde sobre las probables consecuencias desastrosas para los bolcheviques si el gobierno polaco emprendiera una cooperación militar con Denikin en el momento de su avance sobre Moscú . [93] En un libro que publicó posteriormente, Denikin señaló a Polonia como el salvador del poder bolchevique. [94]

Denikin pidió ayuda a Piłsudski en dos ocasiones, en verano y otoño de 1919. Según Denikin, «la derrota del sur de Rusia pondrá a Polonia frente a un poder que se convertirá en una calamidad para la cultura polaca y amenazará la existencia del Estado polaco». Según Piłsudski, «el mal menor es facilitar la derrota de la Rusia Blanca por la Rusia Roja... Con cualquier Rusia, luchamos por Polonia. Que todo ese sucio Occidente hable todo lo que quiera; no vamos a dejarnos arrastrar y utilizar para la lucha contra la revolución rusa. Muy al contrario, en nombre de los intereses permanentes polacos, queremos facilitarle al ejército revolucionario la acción contra el ejército contrarrevolucionario». [93] El 12 de diciembre, el Ejército Rojo expulsó a Denikin de Kiev. [93]

Los intereses percibidos de Polonia y la Rusia Blanca eran irreconciliables. Piłsudski quería dividir Rusia y crear una Polonia poderosa. Denikin, Alexander Kolchak y Nikolai Yudenich querían la integridad territorial de la "Rusia única, grande e indivisible". [94] Piłsudski tenía en baja estima a las fuerzas militares bolcheviques y pensaba que la Rusia Roja era fácil de derrotar. Los comunistas victoriosos en la guerra civil iban a ser empujados hacia el este y privados de Ucrania, Bielorrusia, las tierras bálticas y el sur del Cáucaso; ya no constituirían una amenaza para Polonia. [94]

Desde el comienzo del conflicto, las partes polaca y rusa habían declarado muchas iniciativas de paz, pero estaban destinadas a cubrirse o ganar tiempo, ya que cada lado se concentraba en los preparativos y movimientos militares. [24] Una serie de negociaciones polaco-soviéticas comenzaron en Białowieża después de la terminación de las actividades militares del verano de 1919; se trasladaron a principios de noviembre de 1919 a Mikashevichy . [82] [93] El asociado de Piłsudski, Ignacy Boerner se reunió allí con el emisario de Lenin, Julian Marchlewski . Animado por los éxitos de sus ejércitos en la guerra civil rusa, el gobierno soviético rechazó las duras condiciones de armisticio polacas en diciembre. Piłsudski interrumpió las conversaciones de Mikashevichy dos días después de la toma soviética de Kiev, pero las principales operaciones militares no se habían reanudado. [82] [93] Al principio de las conversaciones, Boerner informó a Marchlewski que Polonia no tenía intención de renovar su ofensiva; Permitió a los soviéticos trasladar cuarenta y tres mil tropas del frente polaco para luchar contra Denikin. [82] [95]

La única excepción a la política polaca de estabilización del frente desde el otoño de 1919 fue el ataque invernal a Daugavpils. [96] Los intentos anteriores de Rydz-Śmigły de capturar la ciudad en verano y principios de otoño habían sido infructuosos. [96] Un pacto político y militar secreto sobre un ataque común a Daugavpils fue firmado entre representantes de Polonia y el Gobierno Provisional de Letonia el 30 de diciembre. El 3 de enero de 1920, fuerzas polacas y letonas (30.000 polacos y 10.000 letones) comenzaron una operación conjunta contra el sorprendido enemigo. El 15.º Ejército bolchevique se retiró y no fue perseguido; la lucha terminó el 25 de enero. [96] La toma de Daugavpils fue realizada principalmente por la División de Infantería de la 3.ª Legión bajo el mando de Rydz-Śmigły. [48] [97] Posteriormente, la ciudad y sus alrededores fueron entregados a los letones. [48] [96] [98] [99] El resultado de la campaña interrumpió las comunicaciones entre las fuerzas lituanas y rusas. [96] Una guarnición polaca estuvo estacionada en Daugavpils hasta julio de 1920. Al mismo tiempo, las autoridades letonas entablaron negociaciones de paz con los soviéticos, que dieron como resultado la firma de un armisticio preliminar. Piłsudski y la diplomacia polaca no fueron notificados y no estaban al tanto de este desarrollo. [96]

Los combates de 1919 dieron como resultado la formación de un frente muy largo, que, según el historiador Eugeniusz Duraczyński, favorecía a Polonia en esta etapa. [84]

A finales de 1919 y principios de 1920, Piłsudski emprendió su gigantesca tarea de dividir Rusia y crear el bloque de países Intermarium . [100] [101] Ante la negativa de Lituania y otros países de la región del Báltico oriental a participar en el proyecto, puso su mirada en Ucrania. [98] [100]

A finales del otoño de 1919, muchos políticos polacos creían que Polonia había logrado establecer fronteras estratégicamente deseables en el este y que, por lo tanto, era necesario poner fin a la lucha contra los bolcheviques y comenzar las negociaciones de paz. La búsqueda de la paz también dominaba los sentimientos populares y se habían producido manifestaciones contra la guerra. [102]

Los dirigentes de la Rusia soviética se enfrentaban en aquel momento a una serie de acuciantes problemas internos y externos. Para abordar eficazmente las dificultades, querían detener la guerra y ofrecer la paz a sus vecinos, con la esperanza de poder salir del aislamiento internacional al que habían estado sometidos. Los aliados potenciales de Polonia (Lituania, Letonia, Rumania o los estados del Cáucaso meridional), cortejados por los soviéticos, no estaban dispuestos a sumarse a una alianza antisoviética liderada por Polonia. Frente al decreciente fervor revolucionario en Europa, los soviéticos se inclinaban a postergar su proyecto emblemático, una república soviética de Europa, hasta un futuro indefinido. [103]

Las ofertas de paz enviadas a Varsovia por el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores de Rusia, Georgy Chicherin, y otras instituciones gubernamentales rusas entre finales de diciembre de 1919 y principios de febrero de 1920 no habían recibido respuesta. Los soviéticos propusieron una línea de demarcación de tropas favorable para Polonia, coherente con las fronteras militares actuales, y dejaron la determinación de las fronteras permanentes para más adelante. [104]

Aunque las propuestas soviéticas despertaron un interés considerable en los sectores socialistas, agrarios y nacionalistas, los intentos del Sejm polaco de evitar más guerras resultaron inútiles. Piłsudski, que gobernaba el ejército y en gran medida el débil gobierno civil, impidió cualquier movimiento hacia la paz. A finales de febrero, ordenó a los representantes polacos que entablaran negociaciones simuladas con los soviéticos. Piłsudski y sus colaboradores destacaron lo que veían como una ventaja militar polaca cada vez mayor sobre el Ejército Rojo y su creencia de que el estado de guerra había creado condiciones muy favorables para el desarrollo económico de Polonia. [105]

El 4 de marzo de 1920, el general Władysław Sikorski inició una nueva ofensiva en Polesia; las fuerzas polacas habían abierto una brecha entre las fuerzas soviéticas al norte (Bielorrusia) y al sur (Ucrania). La contraofensiva soviética en Polesia y Volinia fue rechazada. [98]

Las negociaciones de paz polaco-rusas de marzo de 1920 no dieron resultado. Piłsudski no estaba interesado en una solución negociada del conflicto. Se estaban ultimando los preparativos para una reanudación a gran escala de las hostilidades y el recién nombrado mariscal (a pesar de las protestas de la mayoría de los diputados parlamentarios) y su círculo esperaban que la nueva ofensiva planeada condujera al cumplimiento de las ideas federalistas de Piłsudski. [82] [106]

El 7 de abril, Chicherin acusó a Polonia de rechazar la oferta de paz soviética y notificó a los aliados los acontecimientos negativos, instándolos a prevenir la inminente agresión polaca. La diplomacia polaca alegó la necesidad de contrarrestar la amenaza inmediata de un asalto soviético en Bielorrusia, pero la opinión occidental, a la que los argumentos soviéticos parecían razonables, rechazó la narrativa polaca. [107] Las fuerzas soviéticas en el frente bielorruso eran débiles en ese momento y los bolcheviques no tenían planes para una acción ofensiva. [105]

Tras resolver los conflictos armados de Polonia con los estados ucranianos emergentes a satisfacción de Polonia, Piłsudski pudo trabajar en una alianza polaco-ucraniana contra Rusia. [108] [109] El 2 de diciembre de 1919, Andriy Livytskyi y otros diplomáticos ucranianos declararon su disposición a renunciar a las reclamaciones ucranianas sobre el este de Galicia y el oeste de Volinia, a cambio del reconocimiento por parte de Polonia de la independencia de la República Popular Ucraniana (UPR). [109] El Tratado de Varsovia , el acuerdo de Piłsudski con Hetman Symon Petliura, el líder nacionalista ucraniano exiliado, y otros dos miembros del Directorio de Ucrania, se firmó el 21 de abril de 1920. [110] [111] Parecía ser el mayor éxito de Piłsudski, que potencialmente significaba el comienzo de una implementación exitosa de sus planes de larga data. Petliura, que representaba formalmente al gobierno de la República Popular de Ucrania, que había sido derrotada de facto por los bolcheviques , huyó con algunas tropas ucranianas a Polonia, donde encontró asilo político . Su control se extendía sólo a una franja de tierra cerca de las áreas controladas por Polonia. [112] Por lo tanto, Petliura no tuvo más remedio que aceptar la oferta polaca de alianza, en gran medida en términos polacos, según lo determinado por el resultado de la reciente guerra entre las dos naciones. [113]

Al concluir un acuerdo con Piłsudski, Petliura aceptó las ganancias territoriales polacas en el oeste de Ucrania y la futura frontera polaco-ucraniana a lo largo del río Zbruch. A cambio de renunciar a las reivindicaciones territoriales ucranianas, se le prometió la independencia de Ucrania y la asistencia militar polaca para restablecer su gobierno en Kiev. [16] [100] Dada la poderosa oposición contra la política oriental de Piłsudski en una Polonia cansada de la guerra, las negociaciones con Petliura se llevaron a cabo en secreto y el texto del acuerdo del 21 de abril permaneció secreto. Polonia reconoció en él el derecho de Ucrania a partes de la antigua Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania (antes de 1772) al este del Zbruch. [48] Se añadió una convención militar el 24 de abril; puso las unidades ucranianas bajo el mando polaco. [110] El 1 de mayo, se negoció un acuerdo comercial polaco-ucraniano. No se había firmado para evitar que sus amplias disposiciones que anticipaban la explotación de Ucrania por parte de Polonia se revelaran y causaran un daño catastrófico a la reputación política de Petliura. [114]

Para Piłsudski, la alianza proporcionó a su campaña por la federación Intermarium un punto de partida real y potencialmente el socio más importante de la federación, satisfizo sus demandas con respecto a partes de la frontera oriental de Polonia relevantes para el estado ucraniano propuesto y sentó las bases para un estado ucraniano dominado por Polonia entre Rusia y Polonia. [113] Según Richard K. Debo, mientras que Petliura no podía aportar fuerza real a la ofensiva polaca, para Piłsudski la alianza proporcionó cierto camuflaje para la "agresión descarada involucrada". [113] Para Petliura, era la última oportunidad de preservar la condición de Estado ucraniano y al menos una independencia teórica de las tierras centrales ucranianas, a pesar de su aceptación de la pérdida de tierras de Ucrania occidental a manos de Polonia.

Los británicos y los franceses no reconocieron a la UPR y bloquearon su admisión en la Sociedad de Naciones en el otoño de 1920. El tratado con la república ucraniana no generó ningún apoyo internacional para Polonia, pero provocó nuevas tensiones y conflictos, especialmente dentro de los movimientos ucranianos que aspiraban a la independencia del país. [115]

En cuanto al acuerdo que habían cerrado, ambos líderes se encontraron con una fuerte oposición en sus respectivos países. Piłsudski se enfrentó a una dura oposición de los Demócratas Nacionales de Roman Dmowski, que se oponían a la independencia de Ucrania. [108] Para protestar por la alianza y la inminente guerra por Ucrania, Stanisław Grabski renunció a la presidencia del comité de asuntos exteriores del Sejm, donde los Demócratas Nacionales eran una fuerza dominante (su aprobación sería necesaria para finalizar cualquier futuro acuerdo político). [100] [108] Petliura fue criticado por muchos políticos ucranianos por entrar en un pacto con los polacos y por abandonar Ucrania occidental (después de la destrucción de la República Popular de Ucrania Occidental, Ucrania occidental estaba, desde su punto de vista, ocupada por Polonia). [116] [117] [108]

Durante la ocupación del territorio destinado a la UPR, los funcionarios polacos llevaron a cabo requisas forzadas, algunas de las cuales estaban destinadas al suministro de tropas, pero también saquearon a gran escala a Ucrania y su gente. Esto abarcó desde actividades aprobadas y promovidas al más alto nivel, como el robo generalizado de trenes cargados de mercancías, hasta el saqueo perpetrado por soldados polacos en el campo y las ciudades ucranianas. En sus cartas del 29 de abril y el 1 de mayo al general Kazimierz Sosnkowski y al primer ministro Leopold Skulski , Piłsudski enfatizó que el botín ferroviario había sido enorme, pero no pudo divulgar más porque las apropiaciones se llevaron a cabo en violación del tratado de Polonia con Ucrania. [118]

La alianza con Petliura proporcionó a Polonia 15.000 tropas ucranianas aliadas al comienzo de la campaña de Kiev, [119] que aumentaron a 35.000 mediante el reclutamiento y los desertores soviéticos durante la guerra. [119] Según Chwalba, 60.000 soldados polacos y 4.000 ucranianos participaron en la ofensiva original; había solo 22.488 soldados ucranianos en la lista de raciones de alimentos de Polonia al 1 de septiembre de 1920. [120]

El Ejército polaco estaba formado por soldados que habían servido en los ejércitos de los imperios en proceso de división (especialmente oficiales profesionales ), así como por muchos nuevos reclutas y voluntarios. Los soldados provenían de diferentes ejércitos, formaciones, orígenes y tradiciones. Si bien los veteranos de las legiones polacas de Piłsudski y de la Organización Militar Polaca formaban un estrato privilegiado, la integración del Ejército de la Gran Polonia y del Ejército Azul en la fuerza nacional presentó muchos desafíos. [121] La unificación del Ejército de la Gran Polonia dirigido por el general Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki (una fuerza muy valorada de 120.000 soldados) y el Ejército Azul dirigido por el general Józef Haller, con el Ejército polaco principal bajo el mando de Piłsudski, se había finalizado el 19 de octubre de 1919 en Cracovia , en una ceremonia simbólica. [122]

En el joven Estado polaco, cuya existencia continua era incierta, los miembros de muchos grupos se resistieron al reclutamiento . Por ejemplo, los campesinos polacos y los habitantes de pequeñas ciudades, los judíos o los ucranianos de los territorios controlados por Polonia tendían a evitar el servicio en las fuerzas armadas polacas por diferentes razones. El ejército polaco era abrumadoramente étnico polaco y católico . [123] El problema de la deserción, que se intensificó en el verano de 1920, llevó a la introducción de la pena de muerte por deserción en agosto. Los juicios militares sumarios y las ejecuciones a menudo se llevaban a cabo el mismo día. [124]

Las mujeres soldados funcionaban como miembros de la Legión Voluntaria de Mujeres ; normalmente se les asignaban tareas auxiliares. [125] Se estableció un sistema de entrenamiento militar para oficiales y soldados con la importante ayuda de la Misión Militar Francesa en Polonia . [126]

La Fuerza Aérea polaca contaba con unos dos mil aviones, en su mayoría viejos. El 45% de ellos habían sido capturados al enemigo. Solo doscientos podían estar en el aire en un momento dado. Se utilizaban para diversos fines, incluido el combate, pero sobre todo para el reconocimiento . [127] 150 pilotos y navegantes franceses volaron como parte de la Misión Francesa. [128]

Según Norman Davies , estimar la fuerza de los bandos opuestos es difícil e incluso los generales a menudo tenían informes incompletos de sus propias fuerzas. [129]

Las fuerzas polacas crecieron de aproximadamente 100.000 a finales de 1918 a más de 500.000 a principios de 1920 y 800.000 en la primavera de ese año. [130] [131] Antes de la Batalla de Varsovia, el ejército alcanzó la fuerza total de alrededor de un millón de soldados, incluidos 100.000 voluntarios. [9]

Las fuerzas armadas polacas recibieron ayuda de miembros militares de misiones occidentales, especialmente de la Misión Militar Francesa. Polonia recibió apoyo, además de las fuerzas aliadas ucranianas (más de veinte mil soldados), [132] de unidades rusas y bielorrusas y voluntarios de muchas nacionalidades. [128] Veinte pilotos estadounidenses sirvieron en el Escuadrón Kościuszko . Sus contribuciones en la primavera y el verano de 1920 en el frente ucraniano se consideraron de importancia crítica. [133]

Las unidades antibolcheviques rusas lucharon en el lado polaco. Alrededor de mil soldados blancos lucharon en el verano de 1919. [134] La formación rusa más grande fue patrocinada por el Comité Político Ruso representado por Boris Savinkov y comandada por el general Boris Permikin. [110] [134] El "3er Ejército Ruso" alcanzó más de diez mil soldados listos para el combate y a principios de octubre de 1920 fue enviado al frente para luchar en el lado polaco; no entraron en combate debido al armisticio que entró en vigor en ese momento. [134] Seis mil soldados lucharon valientemente en el lado polaco en las unidades rusas " cosacas " desde el 31 de mayo de 1920. [134] Varias formaciones bielorrusas más pequeñas lucharon en 1919 y 1920. Sin embargo, las organizaciones militares rusas, cosacas y bielorrusas tenían sus propias agendas políticas y su participación ha sido marginada u omitida en la narrativa de guerra polaca. [134]

Las pérdidas soviéticas y el reclutamiento espontáneo de voluntarios polacos permitieron una paridad numérica aproximada entre los dos ejércitos; [48] en el momento de la Batalla de Varsovia, los polacos pueden haber obtenido una ligera ventaja en número y logística. [135] Una de las principales formaciones del lado polaco fue el Primer Ejército Polaco .

A principios de 1918, Lenin y León Trotsky se embarcaron en la reconstrucción de las fuerzas armadas rusas. El nuevo Ejército Rojo fue establecido por el Consejo de Comisarios del Pueblo (Sovnarkom) el 28 de enero, para reemplazar al desmovilizado Ejército Imperial Ruso. Trotsky se convirtió en comisario de guerra el 13 de marzo y Georgy Chicherin asumió el trabajo anterior de Trotsky como ministro de Asuntos Exteriores. El 18 de abril, se creó la Oficina de Comisarios; inició la práctica de asignar comisarios políticos a las formaciones militares. [136] Un millón de soldados alemanes ocuparon el Imperio ruso occidental, pero el 1 de octubre, después de los primeros indicios de la derrota alemana en Occidente, Lenin ordenó el reclutamiento general con la intención de construir un ejército de varios millones de miembros. Si bien más de 50.000 ex oficiales zaristas se habían unido al Ejército Blanco, 75.000 de ellos terminaron en el Ejército Rojo en el verano de 1919. [137]

En septiembre de 1918 se creó el Consejo Militar Revolucionario de la República Rusa, presidido por Trotsky. Trotsky carecía de experiencia o conocimientos militares, pero sabía cómo movilizar tropas y era un maestro de la propaganda de guerra. Los consejos de guerra revolucionarios de determinados frentes y ejércitos dependían del consejo de la república. El sistema pretendía implementar el concepto de dirección y gestión colectiva de los asuntos militares. [138]

El comandante en jefe del Ejército Rojo, a partir de julio de 1919, fue Serguéi Kámenev , quien fue nombrado por Iósif Stalin . El Estado Mayor de Kámenev estaba dirigido por exgenerales zaristas. Todas sus decisiones debían ser aprobadas por el Consejo Militar. El centro de mando real estaba situado en un tren blindado, utilizado por Trotski para viajar por las zonas del frente y coordinar la actividad militar. [138]

Cientos de miles de reclutas desertaron del Ejército Rojo, lo que dio lugar a 600 ejecuciones públicas en la segunda mitad de 1919. El ejército, sin embargo, llevó a cabo operaciones en varios frentes y siguió siendo una fuerza de combate eficaz. [139]

Oficialmente, el Ejército Rojo contaba con cinco millones de soldados el 1 de agosto de 1920, pero sólo el 10 o 12 por ciento de ellos podía considerarse como fuerza de combate real. Las mujeres voluntarias servían en combate en la misma base que los hombres, también en el 1.er Ejército de Caballería de Semión Budión . El Ejército Rojo era particularmente débil en las áreas de logística, suministros y comunicaciones. Se habían capturado grandes cantidades de armas occidentales a las fuerzas blancas y aliadas y la producción nacional de equipo militar siguió aumentando durante toda la guerra. Aun así, las existencias a menudo eran críticamente escasas. Como en el ejército polaco, las botas habían escaseado y muchos luchaban descalzos. Había relativamente pocos aviones soviéticos (220 como máximo en el frente occidental) [140] y las formaciones aéreas polacas pronto llegaron a dominar el espacio aéreo. [141]

Cuando los polacos lanzaron su ofensiva en Kiev, el Frente Sudoeste ruso contaba con unos 83.000 soldados soviéticos, incluidos 29.000 soldados de primera línea. Los polacos tenían cierta superioridad numérica, que se estimó entre 12.000 y 52.000 efectivos. [129] Durante la contraofensiva soviética de mediados de 1920, en todos los frentes, los soviéticos sumaban unos 790.000 efectivos, al menos 50.000 más que los polacos. Mijaíl Tujachevski estimó que tenía 160.000 soldados listos para el combate, mientras que Piłsudski estimó las fuerzas de Tujachevski en 200.000-220.000. [142]

En 1920, el personal del Ejército Rojo contaba con 402.000 efectivos en el Frente Occidental Soviético y 355.000 en el Frente Sudoeste en Galicia, según Davies. [142] Grigori F. Krivosheev da 382.071 efectivos para el Frente Occidental y 282.507 para el Frente Sudoeste entre julio y agosto. [143]

Tras la reorganización de la División de Fusileros Occidental a mediados de 1919, no había unidades polacas independientes dentro del Ejército Rojo. En los frentes occidental y sudoeste, además de unidades rusas, había unidades ucranianas, letonas y germano-húngaras independientes. Además, muchos comunistas de diversas nacionalidades, por ejemplo los chinos, lucharon en unidades integradas. El ejército lituano apoyó a las fuerzas soviéticas en cierta medida. [110]

Entre los comandantes que lideraron la ofensiva del Ejército Rojo estaban Semyon Budyonny, León Trotsky, Sergey Kamenev, Mikhail Tukhachevsky (el nuevo comandante del Frente Occidental), Alexander Yegorov (el nuevo comandante del Frente Suroccidental) y Hayk Bzhishkyan .

La logística era muy mala para ambos ejércitos y se apoyaban en todo el equipo que quedaba de la Primera Guerra Mundial o que se podía capturar. El ejército polaco, por ejemplo, utilizaba armas fabricadas en cinco países y fusiles fabricados en seis, cada uno de los cuales utilizaba munición diferente. [144] Los soviéticos tenían a su disposición muchos depósitos militares que habían sido abandonados por los ejércitos alemanes después de su retirada en 1918-1919, y armamentos franceses modernos que fueron capturados en gran número a los rusos blancos y a las fuerzas expedicionarias aliadas durante la guerra civil rusa. Aun así, sufrieron una escasez de armas, ya que tanto el Ejército Rojo como las fuerzas polacas estaban muy mal equipadas según los estándares occidentales. [144]

Sin embargo, el Ejército Rojo tenía a su disposición un extenso arsenal, así como una industria armamentística en pleno funcionamiento concentrada en Tula , ambos heredados de la Rusia zarista. [145] [146] Por el contrario, las potencias que se repartieron habían evitado deliberadamente industrializar los territorios étnicamente polacos, y mucho menos permitir el establecimiento de una industria armamentística significativa dentro de ellos. Como resultado, no había fábricas de armas de fuego en Polonia y todo, incluidos fusiles y municiones, tenía que ser importado. [145] Se había logrado un progreso gradual en el área de la fabricación militar y después de la guerra había en Polonia 140 establecimientos industriales que producían artículos militares. [147]

La guerra polaco-soviética no se libró mediante una guerra de trincheras , sino mediante formaciones maniobrables. El frente total tenía una longitud de 1500 km (más de 900 millas) y estaba formado por un número relativamente pequeño de tropas. [145] En la época de la Batalla de Varsovia y después, los soviéticos sufrían de líneas de transporte excesivamente largas y no habían podido abastecer a sus fuerzas de manera oportuna. [145]

A principios de 1920, el Ejército Rojo había tenido mucho éxito contra el movimiento blanco. [42] En enero de 1920, los soviéticos comenzaron a concentrar fuerzas en el frente norte de Polonia, a lo largo del río Berezina. [71] El primer ministro británico David Lloyd George ordenó que se levantara el bloqueo del mar Báltico a la Rusia soviética. Estonia firmó con Rusia el Tratado de Tartu el 3 de febrero, reconociendo al gobierno bolchevique. Los comerciantes de armas europeos procedieron a suministrar a los soviéticos los artículos que necesitaban los militares, por los que el gobierno ruso pagó con oro y objetos de valor tomados del stock imperial y confiscados a individuos. [139]

Desde principios de 1920, tanto el lado polaco como el soviético se habían preparado para enfrentamientos decisivos. Sin embargo, Lenin y Trotsky aún no habían podido deshacerse de todas las fuerzas blancas, incluido especialmente el ejército de Pyotr Wrangel , que los amenazaba desde el sur. Piłsudski, libre de tales limitaciones, pudo atacar primero. [84] Convencido de que los blancos ya no eran una amenaza para Polonia, decidió encargarse del enemigo restante, los bolcheviques. [111] El plan para la ofensiva de Kiev era derrotar al Ejército Rojo en el flanco sur de Polonia e instalar el gobierno pro-polaco de Petliura en Ucrania. [16]

Victor Sebestyen , autor de una biografía de Lenin en 2017, escribió: «Los polacos recién independizados comenzaron la guerra. Con el respaldo de Inglaterra y Francia, invadieron Ucrania en la primavera de 1920». Algunos líderes aliados no habían apoyado a Polonia, incluido el ex primer ministro británico HH Asquith , quien calificó la ofensiva de Kiev como «una aventura puramente agresiva, una empresa desenfrenada». Sebestyen caracterizó a Piłsudski como un «nacionalista polaco, no un socialista». [148]

El 17 de abril de 1920, el Estado Mayor polaco ordenó a las fuerzas armadas que asumieran posiciones de ataque. El Ejército Rojo, que se había estado reagrupando desde el 10 de marzo, no estaba completamente preparado para el combate. [149] El objetivo principal de la operación militar era crear un estado ucraniano, formalmente independiente pero bajo el patrocinio polaco, que separaría a Polonia de Rusia. [16] [149]

El 25 de abril, el grupo del sur de los ejércitos polacos bajo el mando de Piłsudski comenzó una ofensiva en dirección a Kiev . [149] Las fuerzas polacas fueron asistidas por miles de soldados ucranianos bajo el mando de Petliura , que representaba a la República Popular de Ucrania. [119] [150]

Aleksandr Yegorov , comandante del Frente Sudoeste Ruso , tenía a su disposición los ejércitos 12 y 14. Estos se enfrentaron a la fuerza invasora, pero eran pequeños (15.000 soldados listos para el combate), débiles, mal equipados y habían sido distraídos por las rebeliones campesinas en Rusia . Los ejércitos de Yegorov se habían reforzado gradualmente desde que los soviéticos se enteraron de los preparativos de guerra polacos. [151]

El 26 de abril, en su "Llamado al pueblo de Ucrania", Piłsudski dijo a su audiencia prevista que "el ejército polaco sólo se quedaría el tiempo que fuera necesario hasta que un gobierno ucraniano legal tomara el control de su propio territorio". Sin embargo, aunque muchos ucranianos eran anticomunistas, muchos eran antipolacos y estaban resentidos por el avance polaco. [16] [116]

El 3.er Ejército polaco, muy bien equipado y móvil, bajo el mando de Rydz-Śmigły, rápidamente dominó al Ejército Rojo en Ucrania. [152] Los 12.º y 14.º Ejércitos soviéticos se habían negado en su mayor parte a entrar en combate y sufrieron pérdidas limitadas; se retiraron o fueron empujados más allá del río Dniéper. [100] [149] [153] El 7 de mayo, las fuerzas combinadas polaco-ucranianas, lideradas por Rydz-Śmigły, encontraron solo una resistencia simbólica al entrar en Kiev, en su mayoría abandonada por el ejército soviético. [16] [149]

Los soviéticos lanzaron su primera contraofensiva utilizando las fuerzas del frente occidental. Siguiendo las órdenes de Trotsky, Mijail Tujachevski lanzó una ofensiva en el frente bielorruso antes de la llegada (planeada por el mando polaco) de tropas polacas procedentes del frente ucraniano.14 de mayo,Sus fuerzas atacaron a los ejércitos polacos, algo más débiles, y penetraron en las zonas controladas por ellos (territorios entre los ríos Daugava y Berezina ) hasta una profundidad de 100 km. Después de que dos divisiones polacas llegaran desde Ucrania y se reuniera el nuevo Ejército de Reserva, Stanisław Szeptycki , Kazimierz Sosnkowski y Leonard Skierski lideraron una contraofensiva polaca a partir del 28 de mayo. El resultado fue la recuperación polaca de la mayor parte del territorio perdido. A partir del 8 de junio, el frente se había estabilizado cerca del río Avuta y permaneció inactivo hasta julio. [154] [155]

El avance polaco en Ucrania fue respondido con contraataques del Ejército Rojo a partir del 29 de mayo. [4] Para entonces, el Frente Suroccidental de Yegorov había sido considerablemente reforzado e inició una maniobra de asalto en el área de Kiev. [149]

El 1.er Ejército de Caballería de Semión Budyonny ( Konarmia ) llevó a cabo repetidos ataques y rompió el frente polaco-ucraniano el 5 de junio. [4] Los soviéticos desplegaron unidades de caballería móviles para interrumpir la retaguardia polaca y atacar las comunicaciones y la logística. [149] El 10 de junio, los ejércitos polacos estaban en retirada a lo largo de todo el frente. Siguiendo la orden de Piłsudski, Rydz-Śmigły, con las tropas polacas y ucranianas bajo su mando, abandonó Kiev (la ciudad no estaba siendo atacada) en manos del Ejército Rojo. [149] [156]

El 29 de abril de 1920, el Comité Central del Partido Comunista Bolchevique de Rusia hizo un llamamiento a los voluntarios para la guerra contra Polonia, con el fin de defender la república rusa contra la usurpación polaca . Las primeras unidades del ejército voluntario partieron de Moscú y se dirigieron al frente el 6 de mayo. [157] El 9 de mayo, el periódico soviético Pravda publicó un artículo titulado "¡Vayan al Oeste!" ( en ruso : На Запад! ): "A través del cadáver de la Polonia Blanca se encuentra el camino al Infierno Mundial. Con bayonetas, llevaremos la felicidad y la paz a la humanidad trabajadora". [158] El 30 de mayo de 1920, el general Aleksei Brusilov , el último comandante en jefe zarista, publicó en Pravda un llamamiento "A todos los ex oficiales, dondequiera que estén", alentándolos a perdonar los agravios pasados y unirse al Ejército Rojo. [159] Brusilov consideraba que era un deber patriótico de todos los oficiales rusos alistarse en el gobierno bolchevique, que según él estaba defendiendo a Rusia contra los invasores extranjeros. [111] Lenin comprendió la importancia de la apelación al nacionalismo ruso . La contraofensiva soviética fue efectivamente impulsada por la participación de Brusilov: 14.000 oficiales y más de 100.000 soldados de rangos inferiores se alistaron o regresaron al Ejército Rojo; miles de voluntarios civiles también contribuyeron al esfuerzo bélico. [160]

El 3.er Ejército y otras formaciones polacas evitaron ser destruidas durante su larga retirada de la frontera de Kiev, pero permanecieron estancadas en el oeste de Ucrania. No pudieron apoyar el frente norte polaco y reforzar, como había planeado Piłsudski , las defensas en el río Avuta . [161]

El frente norte de Polonia, de 320 km de longitud, estaba formado por una delgada línea de 120.000 soldados, respaldados por unas 460 piezas de artillería, sin reservas estratégicas. Esta estrategia de defensa del territorio recordaba la práctica de la Primera Guerra Mundial de establecer una línea de defensa fortificada. Sin embargo, el frente polaco-soviético se parecía poco a las condiciones de esa guerra, ya que estaba escasamente dotado de personal, apoyado por una artillería inadecuada y casi no tenía fortificaciones. Esta disposición permitió a los soviéticos alcanzar la superioridad numérica en lugares estratégicamente cruciales. [161]

Frente a la línea polaca, el Ejército Rojo reunió su Frente Occidental, dirigido por Tujachevski. Su número superaba los 108.000 soldados de infantería y 11.000 de caballería, apoyados por 722 piezas de artillería y 2.913 ametralladoras. [161]

Según Chwalba, los ejércitos 3º, 4º, 15º y 16º de Tujachevski tenían un total de 270.000 soldados y una ventaja de 3:1 sobre los polacos en el área de ataque del frente occidental. [162]

El 4 de julio se lanzó una segunda ofensiva soviética más fuerte y mejor preparada a lo largo del eje Smolensk - Brest y cruzó los ríos Avuta y Berezina. [4] [157] [161] El 3.er Cuerpo de Caballería, conocido como el "ejército de asalto" y dirigido por Hayk Bzhishkyan , desempeñó un papel importante . El primer día de combate, las primeras y segundas líneas de defensa polacas fueron dominadas y el 5 de julio las fuerzas polacas comenzaron una retirada completa y rápida a lo largo de todo el frente. La fuerza de combate del Primer Ejército Polaco se redujo en un 46% durante la primera semana de combate. La retirada pronto se convirtió en una huida caótica y desorganizada. [162]

El 9 de julio comenzaron las conversaciones de Lituania con los soviéticos. Los lituanos lanzaron una serie de ataques contra los polacos y desorganizaron la reubicación planificada de las fuerzas polacas. [163] Las tropas polacas se retiraron de Minsk el 11 de julio.11 de julio. [149]

A lo largo de la línea de antiguas trincheras y fortificaciones alemanas de la Primera Guerra Mundial, solo Lida fue defendida durante dos días. [164] Las unidades de Bzhishkyan junto con las fuerzas lituanas capturaron Vilna el 14 de julio. [149] [161] Al sur, en el este de Galitzia , la caballería de Budyonny se aproximó a Brody , Lwów y Zamość . A los polacos les había quedado claro que los objetivos soviéticos no se limitaban a contrarrestar los efectos de la ofensiva de Kiev, sino que estaba en juego la existencia independiente de Polonia. [165]

Los ejércitos soviéticos avanzaron hacia el oeste a una velocidad notable. Llevando a cabo una maniobra audaz, Bzhishkyan tomó Grodno el 19 de julio; la fortaleza de Osowiec, estratégicamente importante y fácil de defender , fue capturada por el 3.er Cuerpo de Caballería de Bzhishkyan el 27 de julio. [164] Białystok cayó el 28 de julio y Brest el 29 de julio. [166] Una contraofensiva polaca que Piłsudski pretendía fue frustrada por la inesperada caída de Brest. [149] El alto mando polaco intentó defender la línea del río Bug , alcanzada por los rusos el 30 de julio, pero la rápida pérdida de la fortaleza de Brest obligó a cancelar los planes de Piłsudski. [164] El mismo día, las fuerzas polacas retrasaron la ofensiva soviética en la batalla de Żabinka . [167] Después de cruzar el río Narew el 2 de agosto, el frente occidental estaba a sólo unos 100 km (62 millas) de Varsovia. [161]

En ese momento, sin embargo, la resistencia polaca se intensificó. El frente acortado facilitó una mayor concentración de tropas polacas involucradas en operaciones defensivas; se las reforzaba constantemente debido a la proximidad de los centros de población polacos y la afluencia de voluntarios. Las líneas de suministro polacas se habían acortado, mientras que lo contrario sucedía con respecto a la logística enemiga. Como el general Sosnkowski fue capaz de generar y energizar a 170.000 nuevos soldados polacos en pocas semanas, Tukhachevsky notó que, en lugar de concluir rápidamente su misión como se esperaba, su fuerza encontró una resistencia decidida. [168]

El Frente Sudoeste expulsó a las fuerzas polacas de la mayor parte de Ucrania. Stalin frustró las órdenes de Serguéi Kámenev y ordenó a las formaciones bajo el mando de Budión que se acercaran a Zamość y Lviv, la ciudad más grande de Galicia oriental y guarnición del 6.º Ejército polaco. [169] [170] La prolongada batalla de Lviv comenzó en julio de 1920. La acción de Stalin fue perjudicial para la situación de las fuerzas de Tujachevski en el norte, ya que éste necesitaba el relevo de Budión cerca de Varsovia, donde en agosto se libraron batallas decisivas. En lugar de realizar un ataque concéntrico sobre Varsovia, los dos frentes soviéticos se estaban distanciando cada vez más. [145] [170] Piłsudski utilizó el vacío resultante para lanzar su contraofensiva el 16 de agosto, durante la batalla de Varsovia. [145]

En la batalla de Brody y Berestechko (29 de julio-3 de agosto), las fuerzas polacas intentaron detener el avance de Budyonny sobre Lwów, pero el esfuerzo fue frustrado por Piłsudski, que reunió dos divisiones para participar en la lucha que se aproximaba por la capital polaca. [171] [172]

El 1 de agosto de 1920, las delegaciones polaca y soviética se reunieron en Baranavichy e intercambiaron notas, pero sus conversaciones de armisticio no produjeron resultados. [173]

Los aliados occidentales criticaron la política polaca y no estaban contentos con la negativa de Polonia a cooperar con la intervención aliada en la guerra civil rusa, pero apoyaron a las fuerzas polacas que luchaban contra el Ejército Rojo, enviando armamento a Polonia, extendiendo créditos y apoyando al país políticamente. Francia estaba especialmente decepcionada, pero también particularmente interesada en derrotar a los bolcheviques, por lo que Polonia era un aliado natural en este sentido. Los políticos británicos representaban una gama de opiniones sobre la cuestión polaco-rusa, pero muchos eran muy críticos con las políticas y acciones polacas. En enero de 1920, el secretario de Guerra de los Estados Unidos, Newton D. Baker, acusó a Polonia de llevar a cabo una política imperial a expensas de Rusia. A principios de la primavera de 1920, los aliados, irritados por la conducta polaca, consideraron la idea de transferir las tierras al este del río Bug al control aliado, bajo los auspicios de la Liga de las Naciones. [29]

En otoño de 1919, el gobierno británico del primer ministro David Lloyd George aceptó proporcionar armas a Polonia. El 17 de mayo de 1920, tras la toma de Kiev por parte de Polonia, el portavoz del gabinete afirmó en la Cámara de los Comunes que "no se ha prestado ni se está prestando ninguna ayuda al gobierno polaco". [111]

El éxito inicial de la ofensiva de Kiev provocó una enorme euforia en Polonia y la mayoría de los políticos reconocieron el papel de líder de Piłsudski. [48] Sin embargo, cuando la marea se volvió contra Polonia, el poder político de Piłsudski se debilitó y el de sus oponentes, incluido Roman Dmowski , aumentó. El gobierno de Leopold Skulski , aliado de Piłsudski, dimitió a principios de junio. Después de prolongadas disputas, se nombró un gobierno extraparlamentario de Władysław Grabski el 23 de junio de 1920. [174]

Los aliados occidentales estaban preocupados por el avance de los ejércitos bolcheviques, pero culpaban a Polonia de la situación. En su opinión, la conducta de los dirigentes polacos era aventurera y equivalía a jugar con fuego de forma estúpida, lo que podía llevar a la destrucción de los trabajos de la Conferencia de Paz de París. Las sociedades occidentales querían la paz y unas buenas relaciones con Rusia. [175]

As the Soviet armies advanced, the Soviet leadership's confidence soared. In a telegram, Lenin exclaimed, "We must direct all our attention to preparing and strengthening the Western Front. A new slogan must be announced: Prepare for war against Poland".[176] The Soviet communist theorist Nikolai Bukharin, writing for the newspaper Pravda, wished for the resources to carry the campaign beyond Warsaw, "right up to London and Paris".[177] According to General Tukhachevsky's exhortation, "Over the corpse of White Poland lies the path to world conflagration ... On to ... Warsaw! Forward!"[111] As the victory seemed more certain to them, Stalin and Trotsky engaged in political intrigues and argued about the direction of main Soviet offensive.[9][178]

At the height of the Polish–Soviet conflict, Jews were subjected to antisemitic violence by Polish forces, who considered them a potential threat and often accused of supporting the Bolsheviks.[179][180] The perpetrators of the pogroms that took place were motivated by Żydokomuna accusations.[181] During the Battle of Warsaw, the Polish authorities interned Jewish soldiers and volunteers and sent them to an internment camp.[182][183]

To counter the immediate Soviet threat, national resources were urgently mobilized in Poland and competing political factions declared unity. On 1 July, the Council of Defense of the State was appointed.[48][174] On 6 July, Piłsudski was outvoted in the council, which resulted in the trip of Prime Minister Grabski to the Spa Conference in Belgium made to request Allied assistance for Poland and their mediation in setting up peace negotiations with Soviet Russia.[184][185] The Allied representatives made a number of demands as conditions for their involvement.[186] On 10 July,[184] Grabski signed an agreement containing several terms as required by the Allies: Polish forces would withdraw to the border intended to delineate Poland's eastern ethnographic frontier and published by the Allies on 8 December 1919; Poland would participate in a subsequent peace conference; and the questions of sovereignty over Vilnius, Eastern Galicia, Cieszyn Silesia and Danzig would be left up to the Allies.[185][186] Promises of possible Allied help in mediating the Polish–Soviet conflict were made in exchange.[185][186]

On 11 July 1920, the British Foreign Secretary George Curzon sent a telegram to Georgy Chicherin.[186][187] It requested the Soviets to halt their offensive at what had since become known as the Curzon Line and to accept it as a temporary border with Poland (along the Bug and San Rivers)[32] until a permanent border could be established in negotiations.[16][186] Talks in London with Poland and the Baltic states were proposed. In case of a Soviet refusal, the British threatened to assist Poland with unspecified measures.[188][189] Roman Dmowski's reaction was that Poland's "defeat was greater than the Poles had realized".[186] In the Soviet response issued on 17 July, Chicherin rejected the British mediation and declared willingness to negotiate only directly with Poland.[16][184] Both the British and the French reacted with more definitive promises of help with military equipment for Poland.[190]

The Second Congress of the Communist International deliberated in Moscow between 19 July and 7 August 1920. Lenin spoke of the increasingly favorable odds for the accomplishment of the World Proletarian Revolution, which would lead to the World Soviet Republic; the delegates eagerly followed daily reports from the front.[184] The congress issued an appeal to workers in all countries, asking them to forestall their governments' efforts to aid "White" Poland.[191]

Piłsudski lost another vote at the Defense Council and on 22 July the government dispatched a delegation to Moscow to ask for armistice talks. The Soviets claimed interest in peace negotiations only, the subject the Polish delegation was not authorized to discuss.[184]

Sponsored by the Soviets, the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee (Polrewkom) was formed on 23 July to organise the administration of Polish territories captured by the Red Army.[16][48][184] The committee was led by Julian Marchlewski; Feliks Dzierżyński and Józef Unszlicht were among its members.[184] They found little support in Soviet-controlled Poland.[116] On 30 July in Białystok, the Polrewkom decreed the end of the Polish "gentry–bourgeoisie" government. At Polrewkom's Białystok rally on 2 August, its representatives were greeted on behalf of Soviet Russia, the Bolshevik party and the Red Army by Mikhail Tukhachevsky.[191] The Galician Revolutionary Committee (Galrewkom) was established already on 8 July.[192]

On 24 July, the all-party Polish Government of National Defense under Wincenty Witos and Ignacy Daszyński was established.[48][63][191] It eagerly adopted a radical program of land reform meant to counter Bolshevik propaganda (the scope of the promised reform was greatly reduced once the Soviet threat had receded).[63] The government attempted to conduct peace negotiations with Soviet Russia; a new Polish delegation tried to cross the front and establish contact with the Soviets from 5 August.[191] On 9 August, General Kazimierz Sosnkowski became Minister of Military Affairs.[193]

Piłsudski was severely criticized by politicians ranging from Dmowski to Witos. His military competence and judgement were questioned and he displayed signs of mental instability. However, a majority of members of the Council of National Defense, which was asked by Piłsudski to rule on his fitness to lead the military, quickly expressed their "full confidence". Dmowski, disappointed, resigned his membership in the council and left Warsaw.[194]

Poland suffered from sabotage and delays in deliveries of war supplies when Czechoslovak and German workers refused to transit such materials to Poland.[16] After 24 July in Danzig, given the Germany-instigated strike of seaport workers, the British official and Allied representative Reginald Tower, having consulted the British government, used his soldiers to unload commodities heading for Poland.[191][195] On 6 August, the British Labour Party printed in a pamphlet that British workers would not take part in the war as Poland's allies. In 1920 London dockworkers refused to allow a ship bound for Poland until the weapons were off-loaded. The Trades Union Congress, the Parliamentary Labour Party, and the National Executive Committee also all threatened a general strike if the British Armed Forces directly intervened in Poland.[196] The French Section of the Workers' International declared in its newspaper L'Humanité: "Not a man, not a sou, not a shell for the reactionary and capitalist Poland. Long live the Russian Revolution! Long live the Workers' International!".[161] Weimar Germany, Austria and Belgium banned transit of materials destined for Poland through their territories.[191] On 6 August the Polish government issued an "Appeal to the World", which disputed the charges of Polish imperialism and stressed Poland's belief in self-determination and the dangers of a Bolshevik invasion of Europe.[197]