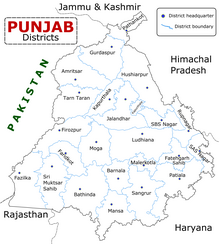

Punjab ( / p ʌ n ˈ dʒ ɑː b / ;[8] Punjabi: [pənˈdʒɑːb] ) es unestadoenel noroeste de la India. Forma parte de laregión más grande de Punjabdelsubcontinente indio, el estado limita con losestados indiosdeHimachal Pradeshal norte y noreste,Haryanaal sur y sureste, yRajastánal suroeste; por losterritorios de la unióndeChandigarhal este yJammu y Cachemiraal norte. Comparte una frontera internacional conPunjab, unaprovinciadePakistánal oeste.[9]El estado cubre un área de 50,362 kilómetros cuadrados (19,445 millas cuadradas), que es el 1,53% del área geográfica total de la India,[10]lo que lo convierte enel 19.º estado indio más grandepor área de los 28 estados indios (el 20.º más grande, si se consideran los Territorios de la Unión). Con más de 27 millones de habitantes, Punjab esel 16.º estado indio más grande por población, que comprende23 distritos.[2] El punjabi, escrito en lagurmukhi, es el idioma más hablado y oficial del estado.[11]El principal grupo étnico son lospunjabis, consikhs(57,7%) ehindúes(38,5%) formando los grupos religiosos dominantes.[12]La capital del estado, Chandigarh, es un territorio de la unión y también la capital del estado vecino deHaryana. Tres afluentes delrío Indo, elSutlej,el Beasyel Ravi, fluyen a través de Punjab.[13]

La historia de Punjab ha sido testigo de la migración y asentamiento de diferentes tribus de personas con diferentes culturas e ideas, formando un crisol de civilizaciones. La antigua civilización del valle del Indo floreció en la región hasta su declive alrededor de 1900 a. C. [14] Punjab se enriqueció durante el apogeo del período védico , pero disminuyó en predominio con el ascenso de los Mahajanapadas . [15] La región formó la frontera de los imperios iniciales durante la antigüedad, incluidos los imperios de Alejandro y Maurya . [16] [17] Posteriormente fue conquistada por el Imperio Kushan , el Imperio Gupta , [18] y luego el Imperio Harsha . [19] Punjab continuó siendo colonizado por pueblos nómadas; incluidos los huna , los turcos y los mongoles . Punjab quedó bajo el dominio musulmán alrededor del año 1000 d. C. , [20] y fue parte del Sultanato de Delhi y el Imperio mogol . [21] El sijismo , basado en las enseñanzas de los gurús sijs , surgió entre los siglos XV y XVII . Los conflictos entre los mogoles y los gurús sijs posteriores precipitaron una militarización de los sijs, lo que resultó en la formación de una confederación después del debilitamiento del Imperio mogol, que compitió por el control con el Imperio durrani más grande . [22] Esta confederación fue unificada en 1801 por Maharaja Ranjit Singh , formando el Imperio sij . [23]

La región más grande de Punjab fue anexada por la Compañía Británica de las Indias Orientales del Imperio Sikh en 1849. [24] En el momento de la independencia de la India del dominio británico en 1947, la provincia de Punjab fue dividida según líneas religiosas en medio de una violencia generalizada, con la porción occidental de mayoría musulmana pasando a formar parte de Pakistán y la parte oriental de mayoría hindú y sikh permaneciendo en la India, lo que provocó una migración a gran escala entre los dos. [25] Después del movimiento Punjabi Suba , el Punjab indio se reorganizó sobre la base del idioma en 1966, [26] cuando sus áreas de habla haryanvi e hindi se dividieron en regiones de habla haryana y pahari unidas a Himachal Pradesh y las áreas restantes, en su mayoría de habla punjabi, se convirtieron en el actual estado de Punjab. Una insurgencia separatista ocurrió en el estado durante la década de 1980. [27] En la actualidad, la economía de Punjab es la 15.ª economía estatal más grande de la India con ₹ 8,02 billones (equivalente a ₹ 8,0 billones o US$ 96 mil millones en 2023) en producto interno bruto y un PIB per cápita de ₹ 264 000 (equivalente a ₹ 260 000 o US$ 3200 en 2023), ocupando el puesto 17 entre los estados indios . [4] Desde la independencia, Punjab es predominantemente una sociedad agraria . Es el noveno puesto más alto entre los estados indios en el índice de desarrollo humano . [5] Punjab tiene industrias de turismo , música , gastronomía y cine muy activas . [28]

La región de Punjab es conocida por ser el sitio de una de las primeras sociedades urbanas, la Civilización del Valle del Indo que floreció alrededor del 3000 a. C. y decayó rápidamente 1000 años después, luego de las migraciones indoarias que invadieron la región en oleadas entre 1500 y 500 a. C. [29] Las frecuentes guerras intertribales estimularon el crecimiento de agrupaciones más grandes gobernadas por jefes y reyes, que gobernaban reinos locales conocidos como Mahajanapadas . [29] El surgimiento de reinos y dinastías en Punjab está narrado en las antiguas epopeyas hindúes, particularmente en el Mahabharata . [29] Las batallas épicas descritas en el Mahabharata están narradas como libradas en lo que ahora es el estado de Haryana y el Punjab histórico. Los Gandharas , Kambojas , Trigartas , Andhra , Pauravas , Bahlikas ( colonos bactrianos del Punjab), Yaudheyas y otros se aliaron con los Kauravas en la gran batalla librada en Kurukshetra . [30] Según el Dr. Fauja Singh y el Dr. L. M. Joshi: "No hay duda de que los Kambojas, Daradas, Kaikayas, Andhra, Pauravas, Yaudheyas, Malavas, Saindhavas y Kurus habían contribuido conjuntamente a la tradición heroica y la cultura compuesta del antiguo Punjab". [31] La mayor parte del Rigveda se compuso en la región del Punjab entre aproximadamente 1500 y 1200 a. C., [32] mientras que las escrituras védicas posteriores se compusieron más al este, entre los ríos Yamuna y Ganges . La religión védica histórica constituyó las ideas y prácticas religiosas en Punjab durante el período védico (1500-500 a. C.), centradas principalmente en el culto a Indra . [33] [34] [35] [i]

,_Adhyaya_1,_lines_1.1.1_to_1.1.9,_Sanskrit,_Devanagari.jpg/440px-1500-1200_BCE_Rigveda,_manuscript_page_sample_i,_Mandala_1,_Hymn_1_(Sukta_1),_Adhyaya_1,_lines_1.1.1_to_1.1.9,_Sanskrit,_Devanagari.jpg)

El primer rey local notable conocido de esta región fue conocido como el rey Poro , que luchó en la famosa Batalla del Hidaspes contra Alejandro Magno . Su reino se extendía entre los ríos Hidaspes ( Jhelum ) y Acesines ( Chenab ); Estrabón había mantenido el territorio para contener casi 300 ciudades. [36] Él (junto con Abisares ) tenía una relación hostil con el Reino de Taxila que estaba gobernado por su familia extendida. [36] Cuando los ejércitos de Alejandro cruzaron el Indo en su migración hacia el este, probablemente en Udabhandapura , fue recibido por el entonces gobernante de Taxila, Omphis . [36] Omphis esperaba obligar a Poro y Abisares a la sumisión aprovechando el poder de las fuerzas de Alejandro y se organizaron misiones diplomáticas, pero mientras Abisares aceptó la sumisión, Poro se negó. [36] Esto llevó a Alejandro a buscar un enfrentamiento con Poro. [36] Así comenzó la Batalla del Hidaspes en 326 a. C.; El lugar exacto sigue siendo desconocido. [36] Se cree que la batalla resultó en una victoria griega decisiva ; sin embargo, AB Bosworth advierte contra una lectura acrítica de las fuentes griegas que eran obviamente exageradas. [36]

Alejandro fundó más tarde dos ciudades: Nicea en el lugar de la victoria y Bucéfalo en el campo de batalla, en memoria de su caballo , que murió poco después de la batalla. [36] [a] Más tarde, se acuñarían tetradracmas que representaban a Alejandro a caballo, armado con una sarisa y atacando a un par de indios en un elefante. [36] [37] Poro se negó a rendirse y vagó por ahí sobre un elefante, hasta que fue herido y su fuerza fue derrotada. [36] Cuando Alejandro le preguntó cómo quería ser tratado, Poro respondió: "Trátame como un rey trataría a otro rey". [38] A pesar de los resultados aparentemente unilaterales, Alejandro quedó impresionado por Poro y decidió no deponerlo. [39] [40] [41] No solo se le restableció su territorio, sino que también se expandió con las fuerzas de Alejandro anexando los territorios de Glausaes, que gobernaba el área al noreste del reino de Poro. [39]

Tras la muerte de Alejandro en el 323 a. C., Pérdicas se convirtió en regente de su imperio, y tras el asesinato de Pérdicas en el 321 a. C., Antípatro se convirtió en el nuevo regente. [42] Según Diodoro , Antípatro reconoció la autoridad de Poro sobre los territorios a lo largo del río Indo . Sin embargo, Eudemo , que había servido como sátrapa de Alejandro en la región de Punjab, mató a traición a Poro. [43] La batalla es históricamente significativa porque dio lugar al sincretismo de las influencias políticas y culturales de la antigua Grecia en el subcontinente indio, produciendo obras como el arte grecobudista , que siguió teniendo un impacto durante los siglos siguientes. La región se dividió entonces entre el Imperio Maurya y el Reino grecobactriano en el 302 a. C. Menandro I Sóter conquistó Punjab e hizo de Sagala (actual Sialkot ) la capital del Reino indogriego . [44] [45] Menandro es conocido por haberse convertido en un mecenas y converso al greco-budismo y es ampliamente considerado como el más grande de los reyes indo-griegos. [46] La influencia griega en la región terminó alrededor del año 12 a. C. cuando el Punjab cayó bajo los sasánidas .

Tras las conquistas musulmanas en el subcontinente indio a principios del siglo VIII, los ejércitos árabes del califato omeya penetraron en el sur de Asia introduciendo el Islam en Punjab. [47] [48] En el siglo IX, la dinastía hindú Shahi surgió en Punjab, gobernando gran parte de Punjab y el este de Afganistán. [29] Los turcos Ghaznavids en el siglo X derrocaron a los hindúes Shahis y en consecuencia gobernaron durante 157 años, decayendo gradualmente como potencia hasta la conquista gúrida de Lahore por Muhammad de Ghor en 1186, deponiendo al último gobernante gáznávida Khusrau Malik . [49] Tras la muerte de Muhammad de Ghor en 1206, el estado gúrida se fragmentó y fue reemplazado en el norte de la India por el Sultanato de Delhi . El sultanato de Delhi gobernó el Punjab durante los siguientes trescientos años, liderado por cinco dinastías no relacionadas: los mamelucos , los khalajis , los tughlaqs , los sayyids y los lodis . Un acontecimiento significativo en el Punjab de finales del siglo XV fue la formación del sijismo por parte del gurú Nanak . [ii] [50] [51] La historia de la fe sij está estrechamente asociada con la historia del Punjab y la situación sociopolítica en el noroeste del subcontinente indio en el siglo XVII. [52] [53] [54] [55]

Los himnos compuestos por Gurú Nanak fueron posteriormente recopilados en el Gurú Granth Sahib , la escritura religiosa central de los sijs. [56] La religión se desarrolló y evolucionó en tiempos de persecución religiosa , ganando conversos tanto del hinduismo como del islam. [57] Los gobernantes mogoles de la India torturaron y ejecutaron a dos de los gurús sijs, Gurú Arjan (1563-1605) y Gurú Tegh Bahadur (1621-1675), después de que se negaran a convertirse al islam . [58] [59] [60] [61] [62] La persecución de los sijs desencadenó la fundación de la Khalsa por Gurú Gobind Singh en 1699 como una orden para proteger la libertad de conciencia y religión , [58] [63] con miembros que expresaban las cualidades de un Sant-Sipāhī ('santo-soldado'). [64] [65] La vida de Guru Nanak coincidió con la conquista del norte de la India por Babur y el establecimiento del Imperio mogol . Jahangir ordenó la ejecución de Guru Arjun Dev , mientras estaba bajo custodia mogol, por apoyar la reclamación rival de su hijo Khusrau Mirza al trono. [66] La muerte de Guru Arjan Dev llevó al sexto Guru Guru Hargobind a declarar la soberanía en la creación del Akal Takht y el establecimiento de un fuerte para defender Amritsar . Jahangir luego encarceló a Guru Hargobind en Gwalior , pero lo liberó después de varios años cuando ya no se sintió amenazado. El hijo sucesor de Jahangir, Shah Jahan , se ofendió por la declaración de Guru Hargobind y después de una serie de asaltos a Amritsar, obligó a los sikhs a retirarse a las colinas de Sivalik . [67] El noveno gurú, Gurú Tegh Bahadur , trasladó la comunidad sikh a Anandpur y viajó extensamente para visitar y predicar desafiando a Aurangzeb , quien intentó instalar a Ram Rai como nuevo gurú.

Los mogoles llegaron al poder a principios del siglo XVI y se expandieron gradualmente para controlar todo el Punjab desde su capital en Lahore . A medida que el poder mogol se debilitaba, los gobernantes afganos tomaron el control de la región. [29] Disputada por marathas y afganos, la región fue el centro de la creciente influencia de los sikhs, que se expandieron y establecieron el Imperio sikh en 1799 a medida que los mogoles y los afganos se debilitaban. [68] Los estados de Cis-Sutlej eran un grupo de estados en los modernos estados de Punjab y Haryana que se encuentran entre el río Sutlej al norte, el Himalaya al este, el río Yamuna y el distrito de Delhi al sur, y el distrito de Sirsa al oeste. Estos estados fueron gobernados por la Confederación Sikh . [69] El imperio existió desde 1799, cuando Ranjit Singh capturó Lahore , hasta 1849, cuando fue derrotado y conquistado en la Segunda Guerra Anglo-Sikh . Se forjó sobre los cimientos de la Khalsa a partir de una colección de misls sikh autónomos . [70] [71] En su apogeo en el siglo XIX, el Imperio se extendió desde el Paso Khyber en el oeste hasta el Tíbet occidental en el este, y desde Mithankot en el sur hasta Cachemira en el norte. Se dividió en cuatro provincias: Lahore , en Punjab, que se convirtió en la capital sikh; Multan , también en Punjab; Peshawar ; y Cachemira de 1799 a 1849. Religiosamente diverso, con una población estimada de 3,5 millones en 1831 (lo que lo convirtió en el decimonoveno país más poblado en ese momento ), [72] fue la última región importante del subcontinente indio en ser anexada por el Imperio británico . El Imperio sikh abarcó un total de más de 200.000 millas cuadradas (520.000 km 2 ) en su apogeo. [73] [74] [75]

Tras la muerte de Ranjit Singh en 1839, el imperio se vio gravemente debilitado por las divisiones internas y la mala gestión política. La Compañía de las Indias Orientales aprovechó esta oportunidad para lanzar la Primera y la Segunda Guerra Anglo-Sikh . El país fue finalmente anexado y disuelto al final de la Segunda Guerra Anglo-Sikh en 1849 en estados principescos separados y la provincia de Punjab . Finalmente, se estableció un teniente gobernador en Lahore como representante directo de la Corona . [76] : 221

El Punjab fue anexado por la Compañía de las Indias Orientales en 1849. Aunque nominalmente formaba parte de la Presidencia de Bengala , era administrativamente independiente. Durante la Rebelión de la India de 1857 , aparte de la Rebelión liderada por Ahmed Khan Kharal y la Rebelión de Murree de 1857 , el Punjab permaneció relativamente pacífico. [77] En 1858, bajo los términos de la Proclamación de la Reina emitida por la Reina Victoria , el Punjab quedó bajo el gobierno directo de Gran Bretaña. El gobierno colonial tuvo un profundo impacto en todas las áreas de la vida punjabi. Económicamente transformó el Punjab en la zona agrícola más rica de la India, socialmente sostuvo el poder de los grandes terratenientes y políticamente alentó la cooperación intercomunitaria entre los grupos terratenientes. [78] El Punjab también se convirtió en el principal centro de reclutamiento para el Ejército indio . Al patrocinar a aliados locales influyentes y centrar las políticas administrativas, económicas y constitucionales en la población rural, los británicos aseguraron la lealtad de su gran población rural. [78] Administrativamente, el régimen colonial instauró un sistema de burocracia y de aplicación de la ley. El sistema «paternal» de la élite gobernante fue reemplazado por el «gobierno de las máquinas», con un sistema de leyes, códigos y procedimientos. Para fines de control, los británicos establecieron nuevas formas de comunicación y transporte, incluidos sistemas de correos, ferrocarriles, carreteras y telégrafos. La creación de las Colonias del Canal en el oeste de Punjab entre 1860 y 1947 permitió el cultivo de 14 millones de acres de tierra y revolucionó las prácticas agrícolas en la región. [78] A la clase agraria y comercial se agregó una clase media profesional que había ascendido en la escala social mediante el uso de la educación inglesa, que abrió nuevas profesiones en derecho, gobierno y medicina. [79] A pesar de estos avances, el régimen colonial se caracterizó por la explotación de los recursos. Para fines de exportación, la mayoría del comercio exterior estaba controlado por los bancos de exportación británicos. El gobierno imperial ejercía control sobre las finanzas de Punjab y se quedaba con la mayoría de los ingresos. [80]

En 1919, Reginald Dyer ordenó a sus tropas disparar contra una multitud de manifestantes, en su mayoría sijs en Amritsar . La masacre de Jallianwala alimentó el movimiento de independencia de la India . [29] Los nacionalistas declararon la independencia de la India de Lahore en 1930, pero fueron rápidamente reprimidos. [29] La lucha por la independencia de la India fue testigo de intereses en competencia y en conflicto en el Punjab. Cuando estalló la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el nacionalismo en la India británica ya se había dividido en movimientos religiosos. [29] Las élites terratenientes de las comunidades musulmana, hindú y sij habían colaborado lealmente con los británicos desde la anexión, apoyaban al Partido Unionista y eran hostiles al movimiento de independencia liderado por el Partido del Congreso. [81] Entre el campesinado y las clases medias urbanas, los hindúes eran los partidarios más activos del Congreso Nacional , los sijs acudieron en masa al movimiento Akali mientras que los musulmanes finalmente apoyaron a la Liga Musulmana . [81] Muchos sijs y otras minorías apoyaron a los hindúes, que prometían una sociedad secular, multicultural y multirreligiosa. En marzo de 1940, la Liga Musulmana Panindia aprobó la Resolución de Lahore , que exigía la creación de un estado separado de las áreas de mayoría musulmana en la India británica. Esto desencadenó encarnizadas protestas de los hindúes y sijs en Punjab, que no podían aceptar vivir en un estado islámico musulmán. [82]

Después de que se decidiera la partición del subcontinente, el 23 de junio de 1947 se celebraron reuniones especiales de la Sección Occidental y Oriental de la Asamblea Legislativa para decidir si se dividiría o no la provincia de Punjab. Después de la votación de ambas partes, se decidió la partición y la Asamblea Legislativa de Punjab existente también se dividió en la Asamblea Legislativa de Punjab Occidental y la Asamblea Legislativa de Punjab Oriental . Esta última Asamblea antes de la independencia celebró su última sesión el 4 de julio de 1947. [83] Durante este período, los británicos concedieron la independencia separada a la India y al Pakistán, lo que desencadenó una violencia comunitaria masiva cuando los musulmanes punjabíes huyeron a Pakistán y los punjabíes hindúes y sikhs huyeron al este, a la India. [29] Los sikhs exigieron más tarde un estado de Punjab de habla punjabi con un gobierno sikh autónomo. [29]

Durante la era colonial , los diversos distritos y estados principescos que componían la provincia de Punjab eran religiosamente eclécticos, y cada uno de ellos contenía poblaciones significativas de musulmanes punjabíes , hindúes punjabíes , sijs punjabíes , cristianos punjabíes , junto con otras minorías étnicas y religiosas. Sin embargo, una consecuencia importante de la independencia y la partición de la provincia de Punjab en 1947 fue el cambio repentino hacia la homogeneidad religiosa que se produjo en todos los distritos de la provincia y la región debido a la nueva frontera internacional que atravesaba la subdivisión.

El cambio demográfico se capturó al comparar los datos del censo decenal tomados en 1941 y 1951 respectivamente, y se debió principalmente a la migración a gran escala, pero también fue causado por disturbios de limpieza religiosa a gran escala que se presenciaron en toda la región en ese momento. Según el demógrafo histórico Tim Dyson , en las regiones orientales de Punjab que finalmente se convirtieron en Punjab indio después de la independencia, los distritos que eran 66% hindúes en 1941 se convirtieron en 80% hindúes en 1951; aquellos que eran 20% sikhs se convirtieron en 50% sikhs en 1951. Por el contrario, en las regiones occidentales de Punjab que finalmente se convirtieron en Punjab paquistaní , todos los distritos se volvieron casi exclusivamente musulmanes en 1951. [84]

Tras la independencia, varios pequeños estados principescos punjabíes, entre ellos Patiala, se adhirieron a la Unión de la India y se unieron en la PEPSU . En 1956, esta se integró con el estado de Punjab Oriental para crear un nuevo estado indio ampliado llamado simplemente "Punjab". El Día de Punjab se celebra en todo el estado el 1 de noviembre de cada año, conmemorando la formación de un estado de habla punjabi en virtud de la Ley de Reorganización de Punjab (1966). [85] [86]

En 1966, siguiendo las demandas de los hindúes y sikhs punjabi, el gobierno indio dividió Punjab en el estado de Punjab y los estados de habla mayoritariamente hindi de Haryana y Himachal Pradesh . [29]

Durante la década de 1960, Punjab era conocida por su prosperidad dentro de la India, en gran medida debido a sus tierras fértiles y a sus habitantes trabajadores. Sin embargo, una parte importante de la comunidad sij sentía una sensación de disparidad con el gobierno central de la India. Las raíces de tales quejas se remontaban a varias décadas atrás, y el problema principal giraba en torno a la distribución del agua del trío de ríos (Ravi, Beas y Sutlej) que fluían a través del territorio punjabi. [87]

Aunque Punjab tenía estas vías fluviales que atravesaban sus tierras, sólo se le concedió legalmente una cuarta parte del agua, precisamente el 24%, según la Ley de Disputas Interestatales sobre el Agua . El resto, un asombroso 76%, se asignó a Rajastán y Haryana. Para muchos punjabis, especialmente la comunidad agrícola que dependía en gran medida de estas aguas para el riego, esta asignación parecía injusta. La distribución del agua fue un factor importante que contribuyó al creciente sentimiento de descontento contra el gobierno central. [87]

Las semillas del descontento brotaron aún más con la llegada de la Revolución Verde durante la década de 1960. Esta iniciativa pretendía impulsar la producción agrícola introduciendo variedades de semillas de alto rendimiento y mejorando el uso de fertilizantes y riego. En medio de esta fase de transformación, Punjab pasó a ser conocido como la "canasta de alimentos" de la India, contribuyendo considerablemente a la producción agrícola del país. Sin embargo, los beneficios financieros obtenidos de este auge agrícola no se distribuyeron de manera justa. [88]

La mayor parte de las ganancias fueron acaparadas por los terratenientes, que por lo general poseían grandes parcelas y estaban en mejor posición para explotar las tecnologías y prácticas agrícolas emergentes. La clase trabajadora y los segmentos económicamente desfavorecidos de la sociedad, que a menudo trabajaban como jornaleros en esas granjas, se quedaron con beneficios menores. Esta distribución desigual de la riqueza entró en marcado conflicto con las costumbres religiosas sikh, que predicaban la justicia económica y la distribución justa de la riqueza. [89]

La Revolución Verde asestó un duro golpe a los pequeños agricultores del Punjab. Los grandes terratenientes, con su acceso a abundantes recursos y capital, estaban en condiciones de adoptar las innovaciones agrícolas que trajo consigo la Revolución. Esta situación provocó aún más resentimiento entre los pequeños agricultores, muchos de los cuales se vieron obligados a renunciar a sus tierras, incapaces de competir, lo que profundizó la brecha económica. [87]

Más allá del sector agrícola, Punjab carecía de oportunidades de empleo sustanciales. Un enfoque excesivo en la agricultura resultó en el descuido del sector industrial del estado, dejándolo notablemente subdesarrollado. Esta concentración sesgada en la agricultura significó que muchos campesinos con dificultades económicas, sin alternativas de empleo viables, se sintieron acorralados y descontentos. [88]

Incluso los terratenientes ricos, los beneficiarios iniciales de la Revolución Verde, sintieron el impacto económico debido al aumento de los precios de los insumos agrícolas como fertilizantes y pesticidas, y la escasez de recursos esenciales como la electricidad y el agua. [89]

Aunque la Revolución Verde fue concebida principalmente para aumentar la productividad, no pudo sostener este aumento de la producción durante un período prolongado. La introducción de nuevas variedades de cultivos condujo a una disminución de la diversidad genética, introduciendo así un nuevo riesgo ecológico. Además, estos nuevos cultivos demandaban más agua y dependían en gran medida de fertilizantes químicos, ambos con consecuencias ambientales nocivas. El uso excesivo de agua condujo al agotamiento de los recursos de agua subterránea, y el uso intensivo de productos químicos afectó negativamente a los sistemas de suelo y agua, socavando aún más la productividad a largo plazo. [87]

Entre 1981 y 1995, el estado sufrió una insurgencia que duró 14 años . Los problemas comenzaron debido a las disputas entre los sijs de Punjab y el gobierno central de la República de la India. Las tensiones se intensificaron a lo largo de la década de 1980 y finalmente culminaron con la Operación Estrella Azul en 1984; una operación del ejército indio dirigida a la comunidad sij disidente de Punjab. Poco después, la primera ministra india, Indira Gandhi, fue asesinada por dos de sus guardaespaldas sijs. La década siguiente se caracterizó por la violencia intercomunitaria generalizada y las acusaciones de genocidio contra la comunidad sij por parte del gobierno indio. [90] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ]

Punjab se encuentra en el noroeste de la India y tiene una superficie total de 50.362 kilómetros cuadrados (19.445 millas cuadradas). Punjab limita con la provincia de Punjab de Pakistán al oeste, Jammu y Cachemira al norte, Himachal Pradesh al noreste y Haryana y Rajastán al sur. [9] La mayor parte de Punjab se encuentra en una llanura aluvial fértil con ríos perennes y un extenso sistema de canales de irrigación. [91] Un cinturón de colinas onduladas se extiende a lo largo de la parte noreste del estado al pie del Himalaya. Su elevación promedio es de 300 metros (980 pies) sobre el nivel del mar, con un rango de 180 metros (590 pies) en el suroeste a más de 500 metros (1.600 pies) alrededor de la frontera noreste. El suroeste del estado es semiárido y eventualmente se fusiona con el desierto de Thar . De los cinco ríos que hay en Punjab, tres (Sutlej, Beas y Ravi) atraviesan el estado indio. El Sutlej y el Ravi definen partes de la frontera internacional con Pakistán.

Las características del suelo están influenciadas en cierta medida por la topografía, la vegetación y la roca madre. La variación en las características del perfil del suelo es mucho más pronunciada debido a las diferencias climáticas regionales. [92] Punjab se divide en tres regiones distintas sobre la base de los tipos de suelo: suroeste, centro y este. Punjab se encuentra en las zonas sísmicas II, III y IV. La zona II se considera una zona de bajo riesgo de daños; la zona III se considera una zona de riesgo de daños moderados; y la zona IV se considera una zona de alto riesgo de daños. [93]

La geografía y la ubicación latitudinal subtropical de Punjab dan lugar a grandes variaciones de temperatura de un mes a otro. Aunque solo en algunas regiones se registran temperaturas inferiores a 0 °C (32 °F), en la mayor parte de Punjab es habitual encontrar heladas durante el invierno. La temperatura aumenta gradualmente cuando hay mucha humedad y cielos nublados. Sin embargo, el aumento de la temperatura es pronunciado cuando el cielo está despejado y la humedad es baja. [94]

Las temperaturas máximas suelen darse a mediados de mayo y junio. La temperatura se mantiene por encima de los 40 °C (104 °F) en toda la región durante este período. Ludhiana registró la temperatura máxima más alta con 46,1 °C (115,0 °F) y Patiala y Amritsar registraron 45,5 °C (113,9 °F). La temperatura máxima durante el verano en Ludhiana se mantiene por encima de los 41 °C (106 °F) durante un mes y medio. Estas áreas experimentan las temperaturas más bajas en enero. Los rayos del sol son oblicuos durante estos meses y los vientos fríos controlan la temperatura durante el día. [94]

Punjab experimenta su temperatura mínima de diciembre a febrero. La temperatura más baja se registró en Amritsar (0,2 °C (32,4 °F)) y Ludhiana se ubicó en segundo lugar con 0,5 °C (32,9 °F). La temperatura mínima de la región se mantiene por debajo de los 5 °C (41 °F) durante casi dos meses durante la temporada de invierno. La temperatura mínima más alta de estas regiones en junio es mayor que las temperaturas máximas diurnas experimentadas en enero y febrero. Ludhiana experimenta temperaturas mínimas superiores a los 27 °C (81 °F) durante más de dos meses. La temperatura media anual en todo el estado es de aproximadamente 21 °C (70 °F). Además, el rango de temperatura media mensual varía entre 9 °C (48 °F) en julio y aproximadamente 18 °C (64 °F) en noviembre. [94]

Punjab tiene tres estaciones principales:

Además de estas tres, el estado experimenta temporadas de transición como:

Punjab comienza a experimentar temperaturas ligeramente cálidas en febrero. La temporada de verano propiamente dicha comienza a mediados de abril y el calor continúa hasta fines de agosto. Las temperaturas máximas entre mayo y agosto oscilan entre 40 y 47 °C. La zona experimenta variaciones de presión atmosférica durante los meses de verano. La presión atmosférica de la región se mantiene alrededor de 987 milibares durante febrero y alcanza los 970 milibares en junio. [94]

La temporada de lluvias en Punjab comienza en la primera semana de julio, cuando las corrientes monzónicas generadas en la bahía de Bengala traen lluvias a la región. El monzón dura hasta mediados de septiembre. [94]

El monzón comienza a disminuir en la segunda semana de septiembre, lo que trae consigo un cambio gradual del clima y la temperatura. El período entre octubre y noviembre es el período de transición entre el monzón y el invierno. El clima durante este período es generalmente templado y seco. [94]

La variación de temperatura es mínima en enero. Las temperaturas medias diurnas y nocturnas descienden a 5 °C (41 °F) y 12 °C (54 °F), respectivamente. [94]

Los efectos del invierno disminuyen en la primera semana de marzo. La temporada de calor del verano comienza a mediados de abril. Este período se caracteriza por lluvias ocasionales con tormentas de granizo y borrascas que causan grandes daños a los cultivos. Los vientos permanecen secos y cálidos durante la última semana de marzo, cuando comienza el período de cosecha. [94]

La temporada de los monzones proporciona la mayor parte de las precipitaciones en la región. Punjab recibe las precipitaciones de la corriente monzónica de la bahía de Bengala. Esta corriente monzónica entra al estado desde el sureste en la primera semana de julio. [94]

La temporada de invierno es muy fría, con temperaturas que caen por debajo del punto de congelación en algunos lugares. El invierno también trae consigo algunas perturbaciones en el oeste. [94] Las lluvias en invierno brindan alivio a los agricultores, ya que algunos de los cultivos de invierno en la región de Shivalik Hills dependen completamente de ellas. Según las estadísticas meteorológicas, la zona sub-Shivalik recibe más de 100 milímetros (3,9 pulgadas) de lluvia en los meses de invierno. [94]

La fauna de la zona es rica, con 396 tipos de aves, 214 tipos de lepidópteros , 55 variedades de peces, 20 tipos de reptiles y 19 tipos de mamíferos. El estado de Punjab tiene grandes áreas de humedales, santuarios de aves que albergan numerosas especies de aves y muchos parques zoológicos. Los humedales incluyen el humedal nacional Hari-Ke-Pattan , el humedal de Kanjli y los humedales de Kapurthala Sutlej. Los santuarios de vida silvestre incluyen el Harike en el distrito de Tarn Taran Sahib, el Parque Zoológico en Rupnagar, el Jardín Chhatbir Bansar en Sangrur, Aam Khas Bagh en Sirhind, el famoso Palacio Ram Bagh de Amritsar , el Jardín Shalimar en Kapurthala y el famoso Jardín Baradari en la ciudad de Patiala. [106]

Punjab tiene la cobertura forestal más baja como porcentaje de la superficie terrestre de cualquier estado de la India , con un 3,6% de su superficie total cubierta de bosques en 2017. [107] Durante la Revolución Verde , se talaron grandes extensiones de selva en el estado para dejar espacio a la agricultura y también se despejaron áreas forestales para infraestructura vial y viviendas residenciales. [107] Varias ONG están trabajando por la forestación y reforestación del estado lanzando campañas educativas, plantando árboles jóvenes, trabajando por cambios regulatorios y presionando a las organizaciones para que cumplan con las leyes ambientales. [107] Una ONG, EcoSikh, ha plantado más de 100 bosques, compuestos de especies de plantas nativas, en el estado utilizando la metodología japonesa Miyawaki que se denominan "Bosques Sagrados Guru Nanak". [108] [109] [110] Las especies de plantas nativas se enfrentan al riesgo de extirpación del estado, pero la plantación de minibosques en todo el territorio puede ayudar a evitar que esto ocurra. [111] Antes de la Revolución Verde, los árboles de Butea monosperma (conocidos como 'dhak' en punjabi) se encontraban en abundancia en el estado. [112]

_from_the_walls_of_the_Golden_Temple_shrine_in_Amritsar_depicting_a_predatory_cat_hunting_an_antelope.jpg/440px-Inlaid_stone_art_(jaratkari)_from_the_walls_of_the_Golden_Temple_shrine_in_Amritsar_depicting_a_predatory_cat_hunting_an_antelope.jpg)

Algunos de los ríos de Punjab tienen cocodrilos, incluidos los gaviales reintroducidos en el río Beas después de medio siglo de su extirpación del estado. [113] [114] [115] Los delfines del río Indo se pueden encontrar en el humedal de Harike . [116] La extracción de seda de los gusanos de seda es otra industria que florece en el estado. La producción de miel de abeja se realiza en algunas partes de Punjab. Las llanuras del sur son tierras desérticas; por lo tanto, se pueden ver camellos. Los búfalos pastan alrededor de las orillas de los ríos. La parte noreste es el hogar de animales como los caballos. Los santuarios de vida silvestre tienen muchas más especies de animales salvajes como la nutria, el jabalí, el gato montés, el murciélago frugívoro, el ciervo porcino, el zorro volador, la ardilla y la mangosta. Se pueden ver bosques formados naturalmente en las cordilleras de Shivalik en los distritos de Ropar, Gurdaspur y Hoshiarpur. En Patiala se encuentra el bosque Bir, mientras que en la zona de humedales de Punjab se encuentra el bosque Mand. [117] La subespecie local de antílope negro, A. c. rajputanae , se enfrenta al riesgo de extirpación del estado. [118] [119] [120]

Existen jardines botánicos en todo el Punjab. Hay un parque zoológico y un parque de safari para tigres, así como tres parques dedicados a los ciervos. [117]

El ave estatal es el azor norteño ( Accipiter gentilis ), [121] el animal estatal es el antílope negro ( Antilope cervicapra ), el animal acuático estatal es el delfín del río Indo ( Platanista minor ) y el árbol estatal es el shisham ( Dalbergia sissoo ). [122]

Punjab alberga al 2,3% de la población de la India; con una densidad de 551 personas por km2 . Según los resultados provisionales del censo nacional de 2011 , Punjab tiene una población de 27.743.338, lo que lo convierte en el decimosexto estado más poblado de la India. De los cuales los hombres y las mujeres son 14.639.465 y 13.103.873 respectivamente. [133] El 32% de la población de Punjab está formada por dalits . [134] En el estado, la tasa de crecimiento de la población es del 13,9% (2011), inferior a la media nacional. Según la encuesta nacional de salud familiar 2019-21, la tasa de fecundidad total de Punjab fue de 1,6 hijos por mujer. [135] [136]

Del total de la población, el 37,5% de las personas viven en zonas urbanas. La cifra total de población que vive en zonas urbanas es de 10.399.146, de los cuales 5.545.989 son hombres y los 4.853.157 restantes son mujeres. La población urbana en los últimos 10 años ha aumentado un 37,5%.

La siguiente tabla muestra la densidad de población (personas por kilómetro cuadrado) de Punjab a través de los años. [138]

La siguiente tabla muestra la densidad de población por distrito en Punjab, según el censo de 2011. [138]

La proporción de sexos en el estado ha disminuido constantemente . En Punjab, la proporción de sexos era de 895 mujeres por cada 1000 hombres, por debajo de la media nacional de 940. En junio de 2023, el gobierno estatal del Partido Aam Aadmi anunció que todas las mujeres que den a luz a una segunda niña recibirán 6000 rupias. [139]

La siguiente tabla muestra la proporción de sexos en los distritos en 2011, en orden descendente. [140]

La tasa de alfabetización aumentó al 75,84% según el censo de población de 2011, que fue solo ligeramente superior al promedio nacional del 74,04%. De ese total, la alfabetización masculina se sitúa en el 80,4%, mientras que la alfabetización femenina es del 70,7%. En cifras reales, el total de alfabetizados en Punjab asciende a 18.707.137, de los cuales los hombres eran 10.436.056 y las mujeres 8.271.081.

En 2011, el número medio de años de escolaridad completados en el estado fue de 6,5 para las mujeres y de 7,8 para los hombres. [141]

La siguiente tabla muestra la tasa de alfabetización por distrito para el año 2011 en orden descendente. [142] [143]

El punjabi es el idioma nativo y oficial único de Punjab y, según el censo de 2011, lo hablan como primera lengua 24,9 millones de personas, o aproximadamente el 90% de la población del estado. [3] El hindi lo hablan 2,18 millones de personas, o el 7,9% de la población, y el bagri tiene 234.000 hablantes (o el 0,8%), mientras que los 413.000 restantes (o el 1,5%) hablan otros idiomas. [144]

Castas del Punjab (2011)

El censo de la India de 2011 determinó que las castas programadas representan el 31,9% de la población del estado. [145] Las otras clases atrasadas tienen el 31,3% de la población en Punjab. [146] La población exacta de las castas avanzadas no se conoce ya que sus datos del censo socioeconómico y de castas de 2011 no se hicieron públicos a partir de 2019. [147]

Según el censo de 2011, el 73,33% de las personas de castas programadas residen en áreas rurales y el 26,67% en áreas urbanas de Punjab. Punjab representa el 4,3% de la población de castas programadas del país, a pesar de tener solo el 2,3% de la población total. La tasa de crecimiento demográfico de la población de castas programadas entre 2001 y 2011 fue del 26,06%, en comparación con el 13,89% del estado en su conjunto. La tasa de alfabetización entre las castas programadas fue del 64,81%, en comparación con el 75,84% del estado en su conjunto. [148]

Según la Encuesta Nacional de Salud Familiar (NFHS-4, 2015-16), la tasa de mortalidad infantil fue de 40 por 1000 nacidos vivos antes de la edad de un año para las castas programadas , en comparación con 29 por 1000 nacimientos para el estado en su conjunto. La tasa de mortalidad infantil para otras castas atrasadas (OBC) fue de 21 por 1000 nacidos vivos y 22 por 1000 para aquellos que no son de las clases SC y OBC. Aunque la prevalencia de anemia (niveles bajos de hemoglobina en la sangre) se ha encontrado bastante alta entre todos los grupos de población en Punjab, todavía era más alta entre la población SC que otros grupos. Para las mujeres entre las edades de 15 y 49 años, la prevalencia de anemia entre las mujeres SC fue del 56,9%, en comparación con el 53,5% para el estado en su conjunto. Entre los niños de entre 6 y 59 meses, la tasa de anemia en los niños de Carolina del Sur fue del 60%, en comparación con el 56,9% en el estado en su conjunto. [148]

A continuación se muestra la lista de distritos según el porcentaje de su población de SC, según el censo de 2011. [148] [149] [150] [151]

Punjab tiene la mayor población de sijs en la India y es el único estado donde los sijs forman una mayoría, con alrededor de 16 millones que forman el 57,7% de la población del estado. [12] El hinduismo es la segunda religión más grande en el estado indio de Punjab, con alrededor de 10,68 millones y formando el 38,5% de la población del estado y una mayoría en la región de Doaba . El Islam es seguido por 535.489 que representan el 1,9% de la población y se concentran principalmente en Malerkotla y Qadian . Otros segmentos más pequeños de religiones existentes en Punjab son el cristianismo practicado por el 1,3%, el jainismo practicado por el 0,2%, el budismo practicado por el 0,1% y otras 0,3%. Los sikhs forman mayoría en 17 distritos de los 23 distritos en total, mientras que los hindúes forman mayoría en 5 distritos, a saber, Pathankot , Jalandhar , Hoshiarpur , Fazilka y Shaheed Bhagat Singh Nagar . [152]

La siguiente tabla muestra la tasa de alfabetización por religión en Punjab, según el censo de 2001. [155]

El santuario sij , el Templo Dorado ( Harmandir Sahib ), se encuentra en la ciudad de Amritsar, que alberga el Comité Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak , el organismo religioso sij más importante. El Sri Akal Takht Sahib , que se encuentra dentro del complejo del Templo Dorado, es la sede temporal más alta de los sijs. De los cinco Takhts (sedes temporales de autoridad religiosa) del sijismo , tres están en Punjab. Estos son Sri Akal Takht Sahib, Damdama Sahib y Anandpur Sahib . Se puede encontrar al menos un Gurdwara sij en casi todos los pueblos del estado, así como en los pueblos y ciudades (en varios estilos arquitectónicos y tamaños).

Se pueden encontrar templos hindúes por todo el Punjab, como el Shri Durgiana Mandir en Amritsar y el Shri Devi Talab Mandir en Jalandhar, que son visitados por muchos peregrinos cada año. Un segmento de los hindúes punjabíes exhibe tradiciones religiosas sincréticas en parentesco espiritual con el sijismo. Esto no solo incluye la veneración de los gurús sikhs en la práctica privada, sino también la visita a los gurdwaras sikhs además de los mandires hindúes. [156]

Punjab se rige por un sistema parlamentario de democracia representativa. Cada uno de los estados de la India posee un sistema parlamentario de gobierno, con un gobernador ceremonial del estado , designado por el presidente de la India siguiendo el consejo del gobierno central. El jefe de gobierno es un ministro jefe elegido indirectamente , que está investido con la mayoría de los poderes ejecutivos. La duración del mandato del gobierno es de cinco años. La legislatura estatal, la Vidhan Sabha , es la Asamblea Legislativa unicameral de Punjab , con 117 miembros elegidos en distritos electorales de un solo escaño. [157]

La capital de Punjab es Chandigarh , que también es la capital de Haryana y, por lo tanto, se administra por separado como territorio de la unión de la India. El poder judicial del gobierno estatal está a cargo del Tribunal Superior de Punjab y Haryana en Chandigarh. [158]

Los tres principales partidos políticos del estado son el Partido Aam Aadmi , un partido centrista a izquierdista, el Shiromani Akali Dal , un partido punjabiyat de derecha sij y el Congreso Nacional Indio , un partido centrista que abarca todo . [159] El gobierno del Presidente se ha impuesto en Punjab ocho veces hasta ahora, desde 1950, por diferentes razones. En términos del número absoluto de días, Punjab estuvo bajo el gobierno del Presidente durante 3.510 días, lo que equivale aproximadamente a 10 años. Gran parte de esto fue en los años 80 durante el apogeo de la militancia en Punjab. Punjab estuvo bajo el gobierno del Presidente durante cinco años continuos desde 1987 hasta 1992.

La ley y el orden en el estado de Punjab son mantenidos por la Policía de Punjab . La policía de Punjab está dirigida por su DGP, Dinkar Gupta, [160] y tiene 70.000 empleados. Gestiona los asuntos estatales a través de 22 jefes de distrito conocidos como SSP.

Punjab tiene 23 distritos, que se clasifican geográficamente en las regiones de Majha , Malwa , Doaba y Puadh , de la siguiente manera:

Estos distritos están divididos oficialmente en cinco divisiones administrativas: Faridkot, Ferozepur, Jalandhar, Patiala y Ropar (creada el 31 de diciembre de 2010, que anteriormente formaba parte de la División de Patiala). [161]

Each district is under the administrative control of a District Collector. The districts are subdivided into 93 tehsils, which have fiscal and administrative powers over settlements within their borders, including maintenance of local land records comes under the administrative control of a Tehsildar. Each Tehsil consists of blocks which are total 150 in number. These blocks consist of Revenue Villages. There are total number of revenue villages in the state is 12,278. There are 23 Zila Parishads, 136 Municipal Committees and 22 Improvement Trusts looking after 143 towns and 14 cities of Punjab.

The capital city of the state is Chandigarh and largest city of the state is Ludhiana. Out of total population of Punjab, 37.48% people live in urban regions. The absolute urban population living in urban areas is 10,399,146 of which 5,545,989 are males and while remaining 4,853,157 are females. The urban population in the last 10 years has increased by 37.48%. The major cities are Ludhiana, Amritsar, Jalandhar, Mohali, Patiala and Bathinda.

Punjab's GDP is ₹5.42 trillion (US$65 billion).[4] Punjab is one of the most fertile regions in India. The region is ideal for wheat-growing. Rice, sugar cane, fruits and vegetables are also grown. Indian Punjab is called the "Granary of India" or "India's bread-basket".[162] It produces 10.26% of India's cotton, 19.5% of India's wheat, and 11% of India's rice. The Firozpur and Fazilka Districts are the largest producers of wheat and rice in the state. In worldwide terms, Indian Punjab produces 2% of the world's cotton, 2% of its wheat and 1% of its rice.[162]

Punjab ranked first in GDP per capita among Indian states in 1981 and fourth in 2001, but has experienced slower growth than the rest of India, having the second-slowest GDP per capita growth rate of all Indian states and UTs between 2000 and 2010, behind only Manipur.[163][164][165][166][167][168][169]

.jpg/440px-A_Cotton_Farm_(South-West_Punjab).jpg)

Punjab's economy has been primarily agriculture-based since the Green Revolution due to the presence of abundant water sources and fertile soils;[170] most of the state lies in a fertile alluvial plain with many rivers and an extensive irrigation canal system.[91] The largest cultivated crop is wheat. Other important crops are rice, cotton, sugarcane, pearl millet, maize, barley and fruit. Rice and wheat are doublecropped in Punjab with rice stalks being burned off over millions of acres prior to the planting of wheat. This widespread practice is polluting and wasteful.[171] Despite covering only 1.53%[10] of its geographical area, Punjab makes up for about 15–20%[172][173][174][175] of India's wheat production, around 12%[176][177][178][179] of its rice production, and around 5%[172][180][181][182] of its milk production, being known as India's breadbasket.[183][184] About 80%[185]-95%[186] of Punjab's agricultural land is owned by its Jat Sikh community despite it only forming 21%[187] of the state's population.[188][189][190]

In Punjab the consumption of fertiliser per hectare is 223.46 kg as compared to 90 kg nationally. The state has been awarded the National Productivity Award for agriculture extension services for ten years, from 1991 to 1992 to 1998–99 and from 2001 to 2003–04. In recent years a drop in productivity has been observed, mainly due to falling fertility of the soil. This is believed to be due to excessive use of fertilisers and pesticides over the years. Another worry is the rapidly falling water table on which almost 90% of the agriculture depends; alarming drops have been witnessed in recent years. By some estimates, groundwater is falling by a meter or more per year.[191][192]

According to the India State Hunger Index 2019-20, Punjab falls under the "Moderate" hunger category in India.[193]

Other major industries include financial services, the manufacturing of scientific instruments, agricultural goods, electrical goods, machine tools, textiles, sewing machines, sports goods, starch, fertilisers, bicycles, garments, and the processing of pine oil and sugar.[184] Minerals and energy resources also contribute to Punjab's economy to a much lesser extent. Punjab has the largest number of steel rolling mill plants in India, which are in "Steel Town"—Mandi Gobindgarh in the Fatehgarh Sahib district.

Punjab also has a large diaspora that is mostly settled in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada, numbers about 3 million, and sends back billions of USD in remittances to the state, playing a major role in its economy.[194]

Sri Guru Ram Das Ji International Airport in Amritsar, is the Primary Hub Airport and Gateway to Punjab, as the airport serves direct connectivity to key cities around the world, including London, Singapore, Moscow, Dubai, Birmingham among others.

Punjab has six civil airports including two international airports: Amritsar International Airport and Chandigarh Airport at Mohali; and four domestic airports: Bathinda Airport, Pathankot Airport, Adampur Airport (Jalandhar) and Ludhiana Airport. Apart from these 6 airports, there are 2 airfields at Beas (Amritsar) and Patiala which do not serve any commercial flight operations, as of now.

The Indian Railways' Northern Railway line runs through the state connecting most of the major towns and cities. The Shatabdi Express, India's fastest series of train connects Amritsar to New Delhi covering total distance of 449 km. Amritsar Junction railway station is the busiest junction of the state. Bathinda Junction holds the record of maximum railway lines from a railway junction in Asia. Punjab's major railway stations are Amritsar Junction (ASR), Ludhiana Junction (LDH), Jalandhar Cantonment (JRC), Firozpur Cantonment (FZR), Jalandhar City Junction (JUC), Pathankot Junction (PTK) and Patiala railway station (PTA). The railway stations of Amritsar is included in the Indian Railways list of 50 world-class railway stations.[195]

Punjab Government have signed a memorandum of understanding with Virgin Hyperloop One to explore the feasibility of running a Hyperloop between Amritsar and Chandigarh which could decrease the travel time between 2 cities from five hours by road to less than 30 minutes. It will have stops in Ludhiana and Jalandhar.[196]

All the cities and towns of Punjab are connected by four-lane national highways. The Grand Trunk Road, also known as "NH1", connects Kolkata to Peshawar, passing through Amritsar and Jalandhar. National highways passing through the state are ranked the best in the country[by whom?] with widespread road networks that serve isolated towns as well as the border region. Amritsar and Ludhiana are among several Indian cities that have the highest accident rates in India.[197]

The following expressways will pass through Punjab:

The following national highways connect major towns, cities and villages:

There are also a bus rapid transit system Amritsar BRTS in the holy city of Amritsar, popularly known as 'Amritsar MetroBus'[198]

Primary and Secondary education is mainly affiliated to Punjab School Education Board. Punjab is served by several institutions of higher education, including 23 universities that provide undergraduate and postgraduate courses in all the major arts, humanities, science, engineering, law, medicine, veterinary science, and business. Reading and writing Punjabi language is compulsory till matriculation for every student[199] failing which the schools attract fine or cancellation of licence.[200]

The table below shows the district level teacher to pupil ratio from class 1 to 5 in Punjab, as of 2017.[201][202][203][204]

The table below shows the average population per school in each district of Punjab as of 2011 census and the total number of schools as of 2017. This includes government schools, affiliated schools, recognised and aided schools.[205] Note:- Pathankot and Fazilka were part of Gurdaspur and Ferozepur respectively, before 2011, so separate data for them regarding the average population per school is not available.

Punjab Agricultural University is a leading institution globally for the study of agriculture and played a significant role in Punjab's Green Revolution in the 1960s–70s. Alumni of the Panjab University, Chandigarh include Manmohan Singh, the former Prime Minister of India, and Har Gobind Khorana, a biochemistry nobel laureate. One of the oldest institutions of medical education is the Christian Medical College, Ludhiana, which has existed since 1894.[206] There is an existing gap in education between men and women, particularly in rural areas of Punjab. Of a total of 1 million 300 thousand students enrolled in grades five to eight, only 44% are women.[207]

Punjab has 23 universities, of which ten are private, 9 are state, one is central and three are deemed universities. Punjab has 104,000 (104,000) engineering seats.[208]

Punjab is also increasingly becoming known for education of yoga and naturopathy, with its student slowly adopting these as their career. The Board of Naturopathy and Yoga Science (BNYS) is located in the state.[209] Regional College Dinanagar is the first college to be opened in Dinanagar Town.[210]

According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data from 2015–16, the rate stunting (low height for age) for children between the ages of 0–59 months was 26%, which was lower than the national average of 38%. As of 2015-16, 56.6% children between the ages of 0–57 months were said to be having some degree of anaemia in Punjab.[211] According to the national family health survey of 2020-21, anaemia rate increased to 71.1%.[212]

According to the National Family Health Survey 2020-21, the percentage of people in Punjab above the age of 15 who consume alcohol was 22.8% for men and 0.3% for women. The rate of tobacco usage in the same age group was 12.9% for men and 0.4% for women. According to the same report, the percentage of males in the age group of 15-49 who were obese or overweight was 32.2% in 2020-21, which an increase from the 27.8% in 2015-16. For women in the same age group, the number in 2020-21 was 40.8% which was an increase from 31.3% in 2015-16. Moreover, according to the same report, 63.1% of the men and 72.8% of the women have high risk waist-to-hip ratio, as of 2020-21.[212]

The table below shows the district wise number of registered doctors and other registered medical personnel in Punjab, in year 2018.[213][214]Note:- The ranks of the districts in this table are in the descending order of the number of registered doctors.

The table below shows the population served per doctor, per nurse and per midwife by districts of Punjab, in the year 2018.[216][217][218][219]Note:- The ranks of the districts in the table are in the ascending order of the population served per doctor.

The table given below shows the population served per doctor in Punjab, by years.[217]

The table below shows the district wise population served per bed.[220]

Daily Ajit, Jagbani and Punjabi Tribune are the largest-selling Punjabi newspapers while The Tribune is most selling English newspaper. A vast number of weekly, biweekly and monthly magazines are under publication in Punjabi. Other main newspapers are Daily Punjab Times, Rozana Spokesman, Nawan Zamana, etc.

Doordarshan is the broadcaster of the Government of India and its channel DD Punjabi is dedicated to Punjabi. Prominent private Punjabi channels include news channels like BBC Punjabi,[221] ABP Sanjha,[222] Global Punjab TV,[223] News18 Punjab-Haryana-Himachal,[224] Zee Punjab Haryana Himachal, PTC News and entertainment channels like Zee Punjabi, GET Punjabi, ETC Punjabi, Chardikla Time TV, PTC Punjabi, Colours Punjabi, JUS Punjabi, MH1 and 9x Tashan.[225]

Punjab has witnessed a growth in FM radio channels, mainly in the cities of Jalandhar, Patiala and Amritsar, which has become hugely popular. There are government radio channels like All India Radio, Jalandhar, All India Radio, Bathinda and FM Gold Ludhiana.[226] Private radio channels include Radio Mirchi, BIG FM 92.7, 94.3 My FM, Radio Mantra and many more.

The culture of Punjab has many elements including music such as bhangra, an extensive religious and non-religious dance tradition, a long history of poetry in the Punjabi language, a significant Punjabi film industry that dates back to before Partition, a vast range of cuisine, which has become widely popular abroad, and a number of seasonal and harvest festivals such as Lohri,[227] Basant, Vaisakhi and Teeyan,[228][229][230] all of which are celebrated in addition to the religious festivals of India.

A kissa is a Punjabi language oral story-telling tradition that has a mixture of origins ranging from the Arabian Peninsula to Iran and Afghanistan.[231]

Punjabi wedding traditions and ceremonies are a strong reflection of Punjabi culture. Marriage ceremonies are known for their rich rituals, songs, dances, food and dresses, which have evolved over many centuries.[232][233]

Bhangra (Punjabi: ਭੰਗੜਾ (Gurmukhi); pronounced [pə̀ŋɡᵊ.ɽäː]) and Giddha are forms of dance and music that originated in the Punjab region.[234]

Bhangra dance began as a folk dance conducted by Punjabi farmers to celebrate the coming of the harvest season. The specific moves of Bhangra reflect the manner in which villagers farmed their land. This hybrid dance became Bhangra. The folk dance has been popularised in the western world by Punjabis in England, Canada and the US where competitions are held.[235] It is seen in the West as an expression of South Asian culture as a whole.[236] Today, Bhangra dance survives in different forms and styles all over the globe – including pop music, film soundtracks, collegiate competitions and cultural shows.

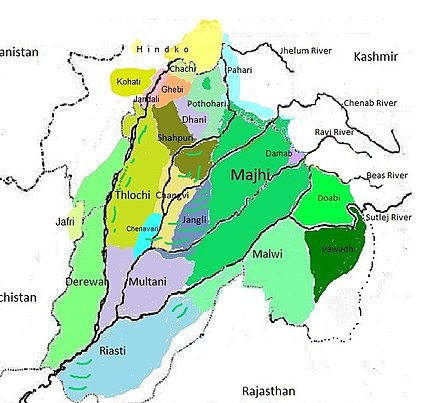

The folk heritage of the Punjab reflects its thousands of years of history. While Majhi is considered to be the standard dialect of Punjabi language, there are a number of Punjabi dialects through which the people communicate. These include Malwai, Doabi and Puadhi. The songs, ballads, epics and romances are generally written and sung in these dialects.

There are a number of folk tales that are popular in Punjab. These are the folk tales of Mirza Sahiban, Heer Ranjha, Sohni Mahiwal, Sassi Punnun, Jagga Jatt, Dulla Bhatti, Puran Bhagat, Jeona Maud etc. The mystic folk songs and religious songs include the Shalooks of Sikh gurus, Baba Farid and others.[237]

The most famous of the romantic love songs are Mayhiah, Dhola and Boliyan.[238] Punjabi romantic dances include Dhamaal, Bhangra, Giddha, Dhola, and Sammi and some other local folk dances.[239]

Most early Punjabi literary works are in verse form, with prose not becoming more common until later periods. Throughout its history, Punjabi literature has sought to inform and inspire, educate and entertain. The Punjabi language is written in several different scripts, of which the Shahmukhi, the Gurmukhī scripts are the most commonly used.[240]

Punjabi Folk Music is the traditional music on the traditional musical instruments of Punjab region.[241][242][243]

Bhangra music of Punjab is famous throughout the world.[28]

Punjabi music has a diverse style of music, ranging from folk and Sufi to classical, notably the Punjab gharana and Patiala gharana.[244][245]

Punjab is home to the Punjabi film industry, often colloquially referred to as 'Pollywood'.[246] It is known for being the fastest growing film industry in India. It is based mainly around Mohali city. According to MP Manish Tewari, the government is planning to build a film city in Mohali.[247]

The first Punjabi film was made in 1936. Since the 2000s Punjabi cinema has seen a revival with more releases every year with bigger budgets, homegrown stars, and Bollywood actors of Punjabi descent taking part.[citation needed]

The city of Amritsar is home to the craft of brass and copper metalwork done by the Thatheras of Jandiala Guru, which is enlisted on the UNESCO's List of Intangible Cultural Heritage.[248] Years of neglect had caused this craft to die out, and the listing prompted the Government of Punjab to undertake a craft revival effort under Project Virasat.[249][250]

One of the main features of Punjabi cuisine is its diverse range of dishes.[251][252] Home cooked and restaurant cuisine sometimes vary in taste. Restaurant style uses large amounts of ghee. Some food items are eaten on a daily basis while some delicacies are cooked only on special occasions.[253]

There are many regional dishes that are famous in some regions only. Many dishes are exclusive to Punjab, including Sarson Da Saag, Tandoori chicken, Shami kebab, makki di roti, etc.[254]

Punjabis celebrate a number of festivals, which have taken a semi-secular meaning and are regarded as cultural festivals by people of all religions. Some of the festivals are Bandi Chhor Divas (Diwali),[255][256] Mela Maghi,[257] Hola Mohalla,[258][259] Rakhri, Vaisakhi, Lohri, Gurpurb, Guru Ravidass Jayanti, Teeyan and Basant Kite Festival.

Kabbadi (Circle Style), a team contact sport originated in rural Punjab is recognised as the state game.[260][261] Field hockey is also a popular sport in the state.[262] Kila Raipur Sports Festival, popularly known as the Rural Olympics, is held annually in Kila Raipur (near Ludhiana). Competition is held for major Punjabi rural sports, include cart-race, rope pulling. Punjab government organises World Kabaddi League,[263][264]

Punjab Games and annual Kabaddi World Cup for Circle Style Kabbadi in which teams from countries like Argentina, Canada, Denmark, England, India, Iran, Kenya, Pakistan, Scotland, Sierra Leone, Spain and United States participated. A major C.B.S.E event C.B.S.E Cluster Athlectics also held in Punjab at Sant Baba Bhag Singh University.[265]

The Punjab state basketball team won the National Basketball Championship on many occasions, most recently in 2019 and 2020.[266][267]

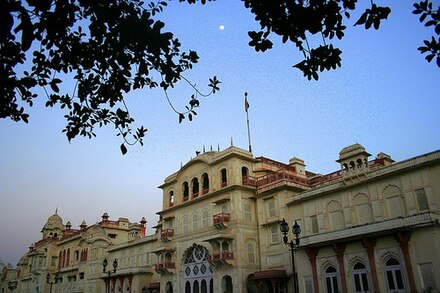

Tourism in Indian Punjab centres around the historic palaces, battle sites, and the great Sikh architecture of the state and the surrounding region.[268] Examples include various sites of the Indus Valley civilisation, the ancient fort of Bathinda, the architectural monuments of Kapurthala, Patiala, and Chandigarh, the modern capital designed by Le Corbusier.[269]

The Golden Temple in Amritsar is one of the major tourist destinations of Punjab and indeed India, attracting more visitors than the Taj Mahal. Lonely Planet Bluelist 2008 has voted the Harmandir Sahib as one of the world's best spiritual sites.[270] Moreover, there is a rapidly expanding array of international hotels in the holy city at Heritage Walk Amritsar that can be booked for overnight stays. Devi Talab Mandir is a Hindu temple located in Jalandhar. This temple is devoted to Goddess Durga[271] and is believed to be at least 200 years old. Another main tourist destination is religious and historic city of Sri Anandpur Sahib where large number of

tourists come to see the Virasat-e-Khalsa (Khalsa Heritage Memorial Complex) and also take part in Hola Mohalla festival. Kila Raipur Sports Festival is also popular tourist attraction in Kila Raipur near Ludhiana.[272][273][274] Shahpur kandi fort, Ranjit Sagar lake and Sikh Temple in Sri Muktsar Sahib are also popular attractions in Punjab. Punjab also has the world's first museum based on the Indian Partition of 1947, in Amritsar, called the Partition Museum.[275]

The number of casualties remains a matter of dispute, with figures being claimed that range from 200,000 to 2 million victims.

The Punjab, to say the least, was less Brahmanical. It was an ancient centre of the worship of Indra, who was always regarded as an enemy by the Bráhmans; and it was also a stronghold of Buddhism.

In the settlements of the Punjab, Indra thus advanced to the first place among the Vedic divinities.

The Rig Veda and the Upanishads, which belonged to the Vedic religion, were a precursor of Hinduism, both of which were composed in Punjab.

Menander king in India, known locally as Milinda, born at a village named Kalasi near Alasanda (Alexandria-in-the-Caucasus), and who was himself the son of a king. After conquering the Punjab, where he made Sagala his capital, he made an expedition across northern India and visited Patna, the capital of the Mauraya empire, though he did not succeed in conquering this land as he appears to have been overtaken by wars on the north-west frontier with Eucratides.

Demetrius died in 166 B.C., and Apollodotus, who was a near relation of the King died in 161 B.C. After his death, Menander carved out a kingdom in Punjab. Thus from 161 B.C. onward Menander was the ruler of Punjab till his death in 145 B.C. or 130 B.C.

First, Islam was introduced into the southern Punjab in the opening decades of the eighth century. By the sixteenth century, Muslims were the majority in the region and an elaborate network of mosques and mausoleums marked the landscape. Local converts constituted the majority of this Muslim community, and as far for the mechanisms of conversion, the sources of the period emphasize the recitation of the Islamic confession of faith (shahada), the performance of the circumsicion (indri vaddani), and the ingestion of cow-meat (bhas khana).

A large number of Hindu and Muslim peasants converted to Sikhism from conviction, fear, economic motives, or a combination of the three (Khushwant Singh 1999: 106; Ganda Singh 1935: 73).

The Sikh kingdom expanded from Tibet in the east to Kashmir in the west and from Sind in the south to the Khyber Pass in the north, an area of 200,000 square miles

..the Sikh state encompassed over 200,000 square miles (518,000 sq km)

..into existence a kingdom of the Punjab of over 200,000 square miles

In March 1930 the All-India Muslim League passed its famous Lahore Resolution, demanding the creation of a separate state from Muslim majority areas in India ... [it] sparked off an enormous furore amongst the Sikhs in the Punjab ... the professed intention of the Muslim League to impose a Muslim state on the Punjab (a Muslim majority province) was anathema to the Sikhs ... Sikhs launched a virulent campaign against the Lahore Resolution.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)Bhangra refers to both a traditional dance and a form of music invented in the 1980s. Bhangra, the Punjabi folk dance that has become popular all over the world. Punjabi folk songs have been integral part of fertile provinces

The whole institution of the Bhangra and its related processes are clearly an expression of Indian/Pakistan culture in a Western setting.