La escultura es la rama de las artes visuales que opera en tres dimensiones . La escultura es la obra de arte tridimensional que se presenta físicamente en las dimensiones de altura, anchura y profundidad. Es una de las artes plásticas . Los procesos escultóricos duraderos utilizaban originalmente el tallado (la eliminación de material) y el modelado (la adición de material, como arcilla), en piedra , metal , cerámica , madera y otros materiales pero, desde el Modernismo , ha habido una libertad casi completa de materiales y procesos. Una amplia variedad de materiales pueden trabajarse por eliminación como el tallado, ensamblarse por soldadura o modelado, o moldearse o fundirse .

Las esculturas en piedra sobreviven mucho mejor que las obras de arte en materiales perecederos y, a menudo, representan la mayoría de las obras supervivientes (aparte de la cerámica ) de culturas antiguas, aunque, por el contrario, las tradiciones de escultura en madera pueden haber desaparecido casi por completo. Sin embargo, la mayoría de las esculturas antiguas estaban pintadas con colores brillantes, y esto se ha perdido. [2]

La escultura ha sido un elemento central de la devoción religiosa en muchas culturas y, hasta hace pocos siglos, las esculturas de gran tamaño, demasiado caras para que las crearan particulares, solían ser una expresión de la religión o la política. Entre las culturas cuyas esculturas han sobrevivido en grandes cantidades se encuentran las del antiguo Mediterráneo, la India y China, así como muchas de América Central y del Sur y África.

La tradición occidental de la escultura comenzó en la antigua Grecia , y se considera que Grecia produjo grandes obras maestras en el período clásico . Durante la Edad Media , la escultura gótica representó las agonías y pasiones de la fe cristiana. El resurgimiento de los modelos clásicos en el Renacimiento produjo esculturas famosas como la estatua de David de Miguel Ángel . La escultura modernista se alejó de los procesos tradicionales y del énfasis en la representación del cuerpo humano, con la realización de esculturas construidas y la presentación de objetos encontrados como obras de arte terminadas.

Existe una distinción entre la escultura "en bulto redondo", escultura exenta como las estatuas , no unidas excepto posiblemente en la base a ninguna otra superficie, y los diversos tipos de relieve , que están al menos parcialmente unidos a una superficie de fondo. El relieve se clasifica a menudo por el grado de proyección desde la pared en bajorrelieve , altorrelieve y , a veces, un mediorrelieve intermedio . El relieve hundido es una técnica restringida al antiguo Egipto . El relieve es el medio escultórico habitual para grandes grupos de figuras y temas narrativos, que son difíciles de lograr en bulto redondo, y es la técnica típica utilizada tanto para la escultura arquitectónica , que se adhiere a los edificios, como para la escultura a pequeña escala que decora otros objetos, como en gran parte de la cerámica , la metalistería y la joyería . La escultura en relieve también puede decorar estelas , losas verticales, generalmente de piedra, que a menudo también contienen inscripciones.

Otra distinción básica es la que se da entre las técnicas de tallado sustractivo, que eliminan material de un bloque o masa existente, por ejemplo de piedra o madera, y las técnicas de modelado, que dan forma o construyen la obra a partir del material. Técnicas como la fundición , la estampación y el moldeado utilizan una matriz intermedia que contiene el diseño para producir la obra; muchas de ellas permiten la producción de varias copias.

El término "escultura" se utiliza a menudo principalmente para describir obras de gran tamaño, que a veces se denominan esculturas monumentales , es decir, esculturas de gran tamaño o que están adosadas a un edificio. Pero el término cubre propiamente muchos tipos de obras pequeñas en tres dimensiones que utilizan las mismas técnicas, incluidas monedas y medallas , tallas de piedra dura , un término para las pequeñas tallas en piedra que pueden requerir un trabajo detallado.

La estatua muy grande o "colosal" ha tenido un atractivo duradero desde la antigüedad ; la más grande registrada con 182 m (597 pies) es la Estatua de la Unidad de la India de 2018. Otra gran forma de escultura de retrato es la estatua ecuestre de un jinete a caballo, que se ha vuelto poco común en las últimas décadas. Las formas más pequeñas de escultura de retrato de tamaño natural son la "cabeza", que muestra solo eso, o el busto , una representación de una persona desde el pecho hacia arriba. Las formas pequeñas de escultura incluyen la figurilla , normalmente una estatua que no mide más de 18 pulgadas (46 cm) de alto, y para los relieves, la plaqueta , la medalla o la moneda.

El arte moderno y contemporáneo ha incorporado una serie de formas no tradicionales de escultura, entre las que se incluyen la escultura sonora , la escultura de luz , el arte ambiental , la escultura ambiental , la escultura de arte callejero , la escultura cinética (que involucra aspectos del movimiento físico ), el land art y el arte específico del sitio . La escultura es una forma importante de arte público . Una colección de esculturas en un entorno de jardín puede denominarse jardín de esculturas . También existe la opinión de que los edificios son un tipo de escultura, y Constantin Brâncuși describe la arquitectura como "escultura habitada". [ cita requerida ]

Uno de los propósitos más comunes de la escultura es la asociación con la religión. Las imágenes de culto son comunes en muchas culturas, aunque a menudo no son las colosales estatuas de deidades que caracterizaron el arte griego antiguo , como la estatua de Zeus en Olimpia . Las imágenes de culto reales en los santuarios más recónditos de los templos egipcios , de las que no ha sobrevivido ninguna, eran evidentemente más bien pequeñas, incluso en los templos más grandes. Lo mismo sucede a menudo en el hinduismo , donde la forma muy simple y antigua del lingam es la más común. El budismo trajo la escultura de figuras religiosas al este de Asia, donde parece que no hubo una tradición equivalente anterior, aunque nuevamente las formas simples como el bi y el cong probablemente tenían un significado religioso.

Las pequeñas esculturas como objetos personales se remontan al arte prehistórico más antiguo, y el uso de esculturas de gran tamaño como arte público , especialmente para impresionar al espectador con el poder de un gobernante, se remonta al menos a la Gran Esfinge de hace unos 4.500 años. En arqueología e historia del arte, la aparición, y a veces la desaparición, de esculturas grandes o monumentales en una cultura se considera de gran importancia, aunque rastrear su aparición a menudo se complica por la presunta existencia de esculturas en madera y otros materiales perecederos de las que no queda ningún registro; [3]

El tótem es un ejemplo de una tradición de escultura monumental en madera que no dejaría rastros para la arqueología. La capacidad de reunir los recursos para crear esculturas monumentales, transportando materiales generalmente muy pesados y organizando el pago de lo que generalmente se consideran escultores a tiempo completo, se considera una señal de una cultura relativamente avanzada en términos de organización social. Los recientes e inesperados descubrimientos de antiguas figuras de la Edad del Bronce china en Sanxingdui , algunas de más del doble del tamaño humano, han alterado muchas de las ideas que se tenían sobre la civilización china temprana, ya que anteriormente solo se conocían bronces mucho más pequeños. [4]

Algunas culturas indudablemente avanzadas, como la civilización del valle del Indo , parecen no haber tenido escultura monumental en absoluto, aunque produjeron figurillas y sellos muy sofisticados. La cultura misisipiana parece haber estado progresando hacia su uso, con pequeñas figuras de piedra, cuando colapsó. Otras culturas, como el antiguo Egipto y la cultura de la Isla de Pascua , parecen haber dedicado enormes recursos a la escultura monumental a gran escala desde una etapa muy temprana.

El coleccionismo de esculturas, incluidas las de períodos anteriores, se remonta a unos 2.000 años en Grecia, China y Mesoamérica, y muchas colecciones estaban disponibles en exposición semipública mucho antes de que se inventara el museo moderno . A partir del siglo XX, la gama relativamente restringida de temas que se encuentran en las esculturas de gran tamaño se amplió enormemente, y ahora son comunes los temas abstractos y el uso o la representación de cualquier tipo de tema. Hoy en día, muchas esculturas se hacen para su exposición intermitente en galerías y museos, y la capacidad de transportar y almacenar las obras, cada vez más grandes, es un factor en su construcción.

Las pequeñas figuras decorativas , generalmente de cerámica, son tan populares hoy en día (aunque extrañamente descuidadas por el arte moderno y contemporáneo ) como lo fueron en el Rococó , o en la antigua Grecia cuando las figuras de Tanagra eran una industria importante, o en el arte del este de Asia y precolombino . Los pequeños accesorios esculpidos para muebles y otros objetos se remontan a la antigüedad, como en los marfiles de Nimrud , los marfiles de Begram y los hallazgos de la tumba de Tutankamón .

La escultura de retratos comenzó en Egipto , donde la Paleta de Narmer muestra a un gobernante del siglo XXXII a. C., y en Mesopotamia , donde tenemos 27 estatuas supervivientes de Gudea , que gobernó Lagash entre 2144 y 2124 a. C. En la antigua Grecia y Roma, la erección de una estatua de retrato en un lugar público era casi la mayor muestra de honor y la ambición de la élite, que también podía ser representada en una moneda. [5]

En otras culturas, como Egipto y Oriente Próximo, las estatuas públicas eran casi exclusivamente propiedad de los gobernantes, y las demás personas ricas solo se representaban en sus tumbas. Los gobernantes suelen ser las únicas personas a las que se retrata en las culturas precolombinas, comenzando por las cabezas colosales olmecas de hace unos 3000 años. La escultura de retratos de Asia oriental era completamente religiosa, y se conmemoraba con estatuas a los principales clérigos, especialmente a los fundadores de monasterios, pero no a los gobernantes ni a los antepasados. La tradición mediterránea revivió, inicialmente solo para efigies y monedas de tumbas, en la Edad Media, pero se expandió enormemente en el Renacimiento, que inventó nuevas formas, como la medalla de retrato personal .

Los animales son, junto con la figura humana, el tema más antiguo de la escultura y siempre han sido populares, a veces como monstruos realistas, pero a menudo imaginarios; en China, los animales y los monstruos son casi los únicos temas tradicionales para la escultura en piedra fuera de las tumbas y los templos. El reino de las plantas es importante solo en la joyería y los relieves decorativos, pero estos forman casi la totalidad de la gran escultura del arte bizantino y el arte islámico , y son muy importantes en la mayoría de las tradiciones euroasiáticas, donde motivos como la palmeta y la vid han pasado de este a oeste durante más de dos milenios.

Una forma de escultura que se encuentra en muchas culturas prehistóricas de todo el mundo son versiones especialmente agrandadas de herramientas, armas o vasijas comunes creadas con materiales preciosos poco prácticos, ya sea para algún tipo de uso ceremonial o exhibición o como ofrendas. El jade u otros tipos de piedra verde se usaban en China, el México olmeca y la Europa neolítica , y en la Mesopotamia temprana se producían grandes formas de cerámica en piedra. El bronce se usaba en Europa y China para grandes hachas y espadas, como el puñal de Oxborough .

Los materiales utilizados en la escultura son diversos y han ido cambiando a lo largo de la historia. Los materiales clásicos, con una durabilidad sobresaliente, son el metal, especialmente el bronce , la piedra y la cerámica, siendo la madera, el hueso y la cornamenta opciones menos duraderas pero más económicas. Los materiales preciosos como el oro , la plata , el jade y el marfil se utilizan a menudo para pequeñas obras de lujo, y a veces en obras de mayor tamaño, como en las estatuas criselefantinas . Para la escultura de consumo más amplio se utilizaron materiales más comunes y menos costosos, incluidas las maderas duras (como el roble , el boj y el tilo ); la terracota y otras cerámicas , la cera (un material muy común para los modelos de fundición y para recibir las impresiones de sellos cilíndricos y gemas grabadas) y los metales fundidos como el peltre y el zinc (spelter). Pero se ha utilizado una gran cantidad de otros materiales como parte de las esculturas, tanto en obras etnográficas y antiguas como en las modernas.

Las esculturas suelen estar pintadas , pero suelen perder su pintura con el paso del tiempo o con la ayuda de restauradores. Para realizar esculturas se han utilizado muchas técnicas de pintura diferentes, entre ellas el temple , la pintura al óleo , el dorado , la pintura para casas, el aerosol, el esmalte y el chorro de arena. [2] [6]

Muchos escultores buscan nuevas formas y materiales para hacer arte. Una de las esculturas más famosas de Pablo Picasso incluía piezas de bicicleta . Alexander Calder y otros modernistas hicieron un uso espectacular del acero pintado . Desde la década de 1960, también se han utilizado acrílicos y otros plásticos. Andy Goldsworthy hace sus esculturas inusualmente efímeras a partir de materiales casi completamente naturales en entornos naturales. Algunas esculturas, como la escultura de hielo , la escultura de arena y la escultura de gas , tienen una vida deliberadamente corta. Los escultores recientes han utilizado vidrieras , herramientas, piezas de máquinas, hardware y envases de consumo para dar forma a sus obras. Los escultores a veces utilizan objetos encontrados , y las rocas de los eruditos chinos han sido apreciadas durante muchos siglos.

La escultura en piedra es una actividad antigua en la que se moldean piezas de piedra natural en bruto mediante la extracción controlada de piedra . Debido a la permanencia del material, se pueden encontrar pruebas de que incluso las sociedades más antiguas se dedicaron a alguna forma de trabajo en piedra, aunque no todas las áreas del mundo tienen tanta abundancia de buena piedra para tallar como Egipto, Grecia, India y la mayor parte de Europa. Los petroglifos (también llamados grabados rupestres) son quizás la forma más antigua: imágenes creadas al eliminar parte de una superficie de roca que permanece in situ , mediante incisión, picoteo, tallado y abrasión. La escultura monumental cubre obras de gran tamaño y la escultura arquitectónica , que se adhiere a los edificios. El tallado en piedra dura es el tallado con fines artísticos de piedras semipreciosas como el jade , el ágata , el ónix , el cristal de roca , la sarda o la cornalina , y un término general para un objeto hecho de esta manera. El alabastro o yeso mineral es un mineral blando que es fácil de tallar para obras más pequeñas y aún relativamente duradero. Las gemas grabadas son pequeñas gemas talladas, incluidos los camafeos , originalmente utilizados como anillos de sello .

La copia de una estatua original en piedra, que era muy importante para las estatuas griegas antiguas, que casi todas se conocen a partir de copias, se lograba tradicionalmente mediante el " señalado ", junto con métodos más manuales. El señalizado implicaba colocar una cuadrícula de cuadrados de cuerda en un marco de madera que rodeaba el original y luego medir la posición en la cuadrícula y la distancia entre la cuadrícula y la estatua de una serie de puntos individuales, y luego usar esta información para tallar en el bloque del que se hace la copia. [8]

El bronce y las aleaciones de cobre relacionadas son los metales más antiguos y aún los más populares para las esculturas de metal fundido ; a una escultura de bronce fundido a menudo se la llama simplemente "bronce". Las aleaciones de bronce comunes tienen la propiedad inusual y deseable de expandirse ligeramente justo antes de fraguar, llenando así los detalles más finos de un molde. Su resistencia y falta de fragilidad (ductilidad) es una ventaja cuando se crean figuras en acción, especialmente cuando se compara con varios materiales cerámicos o de piedra (ver esculturas de mármol para varios ejemplos). El oro es el metal más blando y precioso, y muy importante en joyería ; al igual que la plata, es lo suficientemente blando como para trabajarlo con martillos y otras herramientas, así como para fundirlo; el repujado y el cincelado se encuentran entre las técnicas utilizadas en la orfebrería y la platería .

La fundición es un grupo de procesos de fabricación mediante los cuales un material líquido (bronce, cobre, vidrio, aluminio, hierro) se vierte (normalmente) en un molde, que contiene una cavidad hueca de la forma deseada, y luego se deja solidificar. Luego, la fundición sólida se expulsa o se rompe para completar el proceso, [9] aunque puede seguir una etapa final de "trabajo en frío" en la fundición terminada. La fundición se puede utilizar para formar metales líquidos calientes o varios materiales que se endurecen en frío después de mezclar los componentes (como epoxis , hormigón , yeso y arcilla ). La fundición se utiliza con mayor frecuencia para hacer formas complejas que de otro modo serían difíciles o poco económicas de hacer con otros métodos. La fundición más antigua que sobrevive es una rana mesopotámica de cobre del 3200 a. C. [10] Las técnicas específicas incluyen la fundición a la cera perdida , la fundición en molde de yeso y la fundición en arena .

La soldadura es un proceso en el que se fusionan diferentes piezas de metal para crear diferentes formas y diseños. Hay muchas formas diferentes de soldadura, como la soldadura oxi-combustible , la soldadura con electrodo , la soldadura MIG y la soldadura TIG . El oxi-combustible es probablemente el método de soldadura más común cuando se trata de crear esculturas de acero porque es el más fácil de usar para dar forma al acero, así como para hacer uniones limpias y menos visibles del acero. La clave de la soldadura oxi-combustible es calentar cada pieza de metal que se va a unir de manera uniforme hasta que todas estén rojas y tengan brillo. Una vez que ese brillo esté en cada pieza, ese brillo pronto se convertirá en un "baño" donde el metal se licúa y el soldador debe hacer que los baños se unan, fusionando el metal. Una vez enfriado, el lugar donde se unieron los baños ahora es una pieza continua de metal. También se usa mucho en la creación de esculturas de oxi-combustible la forja. La forja es el proceso de calentar el metal hasta un punto determinado para ablandarlo lo suficiente como para darle diferentes formas. Un ejemplo muy común es calentar el extremo de una varilla de acero y golpear la punta al rojo vivo con un martillo mientras se está sobre un yunque para formar una punta. Entre los golpes del martillo, el forjador hace girar la varilla y forma gradualmente una punta afilada a partir del extremo romo de una varilla de acero.

El vidrio se puede utilizar para la escultura mediante una amplia gama de técnicas de trabajo, aunque su uso para obras de gran tamaño es un desarrollo reciente. Se puede tallar, aunque con considerable dificultad; la copa romana de Licurgo es casi única. [11] Hay varias formas de moldear el vidrio : el vaciado en caliente se puede hacer vertiendo vidrio fundido en moldes que se han creado presionando formas en arena, grafito tallado o moldes detallados de yeso/sílice. El vaciado en horno de vidrio implica calentar trozos de vidrio en un horno hasta que se vuelven líquidos y fluyen hacia un molde que espera debajo de él en el horno. El vidrio caliente también se puede soplar y/o esculpir en caliente con herramientas manuales, ya sea como una masa sólida o como parte de un objeto soplado. Las técnicas más recientes implican cincelar y unir vidrio plano con silicatos poliméricos y luz ultravioleta. [12]

La cerámica es uno de los materiales más antiguos para la escultura, así como la arcilla es el medio en el que se modelan originalmente muchas esculturas fundidas en metal para su fundición. Los escultores suelen construir pequeñas obras preliminares llamadas maquetas de materiales efímeros como yeso de París , cera, arcilla sin cocer o plastilina . [13] Muchas culturas han producido cerámica que combina una función como recipiente con una forma escultórica, y las pequeñas figuras a menudo han sido tan populares como lo son en la cultura occidental moderna. Los sellos y moldes fueron utilizados por la mayoría de las civilizaciones antiguas, desde la antigua Roma y Mesopotamia hasta China. [14]

La talla de madera ha sido una práctica muy extendida, pero sobrevive mucho menos que los otros materiales principales, ya que es vulnerable a la descomposición, los daños de los insectos y el fuego. Por lo tanto, constituye un elemento oculto importante en la historia del arte de muchas culturas. [3] La escultura de madera al aire libre no dura mucho en la mayor parte del mundo, por lo que tenemos poca idea de cómo se desarrolló la tradición del tótem . Muchas de las esculturas más importantes de China y Japón en particular son de madera, y la gran mayoría de la escultura africana y la de Oceanía y otras regiones.

La madera es ligera, por lo que es adecuada para máscaras y otras esculturas que se deben llevar en el hombro, y puede soportar detalles muy finos. También es mucho más fácil de trabajar que la piedra. Muy a menudo se la ha pintado después de tallarla, pero la pintura se desgasta menos que la madera y a menudo falta en las piezas que sobreviven. La madera pintada a menudo se describe técnicamente como "madera y policromía ". Por lo general, se aplica una capa de yeso o yeso a la madera y luego se aplica la pintura.

Las obras tridimensionales que incorporan materiales no convencionales como tela, piel, plástico, caucho y nailon, que pueden ser rellenados, cosidos, colgados, cubiertos o tejidos, se conocen como esculturas blandas . Entre los creadores más conocidos de esculturas blandas se incluyen Claes Oldenburg , Yayoi Kusama , Eva Hesse , Sarah Lucas y Magdalena Abakanowicz . [15]

En todo el mundo, los escultores han sido generalmente comerciantes cuyo trabajo no está firmado; en algunas tradiciones, por ejemplo China, donde la escultura no compartía el prestigio de la pintura literaria , esto ha afectado al estatus de la escultura en sí. [16] Incluso en la antigua Grecia , donde escultores como Fidias se hicieron famosos, parecen haber conservado el mismo estatus social que otros artesanos, y tal vez no recompensas financieras mucho mayores, aunque algunos firmaron sus obras. [17] En la Edad Media, artistas como Gislebertus del siglo XII a veces firmaban su trabajo y eran buscados por diferentes ciudades, especialmente a partir del Trecento en Italia, con figuras como Arnolfo di Cambio y Nicola Pisano y su hijo Giovanni . Los orfebres y joyeros, que trataban con materiales preciosos y a menudo hacían las veces de banqueros, pertenecían a gremios poderosos y tenían un estatus considerable, a menudo ocupando cargos cívicos. Muchos escultores también practicaban otras artes; Andrea del Verrocchio también pintó, y Giovanni Pisano , Miguel Ángel y Jacopo Sansovino fueron arquitectos . Algunos escultores tenían grandes talleres. Incluso en el Renacimiento, Leonardo da Vinci y otros percibieron que la naturaleza física de la obra perjudicaba el estatus de la escultura en las artes, aunque la reputación de Miguel Ángel tal vez acabó con esta idea tan arraigada.

A partir del Alto Renacimiento, artistas como Miguel Ángel, León Leoni y Giambologna pudieron enriquecerse, ennoblecerse y entrar en el círculo de los príncipes, tras un período de acalorados debates sobre el estatus relativo de la escultura y la pintura. [18] Gran parte de la escultura decorativa de los edificios siguió siendo un oficio, pero los escultores que producían piezas individuales eran reconocidos al mismo nivel que los pintores. A partir del siglo XVIII o antes, la escultura también atraía a los estudiantes de clase media, aunque lo hacía con más lentitud que la pintura. Las escultoras tardaron más en aparecer que las pintoras, y fueron menos destacadas hasta el siglo XX.

El aniconismo se originó con el judaísmo , que no aceptó la escultura figurativa hasta el siglo XIX, [19] antes de expandirse al cristianismo , que inicialmente aceptó esculturas de gran tamaño. En el cristianismo y el budismo, la escultura llegó a ser muy significativa. La ortodoxia oriental cristiana nunca ha aceptado la escultura monumental, y el islam ha rechazado sistemáticamente casi toda la escultura figurativa, a excepción de figuras muy pequeñas en relieves y algunas figuras de animales que cumplen una función útil, como los famosos leones que sostienen una fuente en la Alhambra . Muchas formas de protestantismo tampoco aprueban la escultura religiosa. Ha habido mucha iconoclasia de la escultura por motivos religiosos, desde los primeros cristianos y el Beeldenstorm de la Reforma protestante hasta la destrucción de los Budas de Bamiyán en 2001 por los talibanes .

Los primeros ejemplos indiscutibles de escultura pertenecen a la cultura auriñaciense , que se localizó en Europa y el sudoeste de Asia y estuvo activa a principios del Paleolítico superior . Además de producir algunas de las primeras obras de arte rupestre conocidas , los habitantes de esta cultura desarrollaron herramientas de piedra finamente elaboradas, fabricaron colgantes, brazaletes, cuentas de marfil y flautas de hueso, así como figurillas tridimensionales. [20] [21]

El Löwenmensch de 30 cm de alto hallado en la zona de Hohlenstein Stadel en Alemania es una figura antropomorfa de león-hombre tallada en marfil de mamut lanudo . Se ha datado en alrededor de 35-40.000 años AP, lo que lo convierte, junto con la Venus de Hohle Fels , en los ejemplos de escultura más antiguos conocidos sin discusión. [22]

Gran parte del arte prehistórico que sobrevive son pequeñas esculturas portátiles, con un pequeño grupo de figurillas de Venus femeninas como la Venus de Willendorf (24-26.000 AP) encontrada en Europa central. [23] El reno nadador de hace unos 13.000 años es una de las mejores de una serie de tallas magdalenienses en hueso o asta de animales en el arte del Paleolítico superior , aunque son superadas en número por piezas grabadas, que a veces se clasifican como esculturas. [24] Dos de las esculturas prehistóricas más grandes se pueden encontrar en las cuevas de Tuc d'Audobert en Francia, donde hace unos 12-17.000 años un escultor magistral utilizó una herramienta de piedra similar a una espátula y los dedos para modelar un par de bisontes grandes en arcilla contra una roca caliza. [25]

Con el comienzo del Mesolítico en Europa la escultura figurativa se redujo considerablemente, [26] y siguió siendo un elemento menos común en el arte que la decoración en relieve de objetos prácticos hasta el período romano, a pesar de algunas obras como el caldero de Gundestrup de la Edad de Hierro europea y el carro solar de Trundholm de la Edad de Bronce . [27]

Del antiguo Oriente Próximo , el Hombre de Urfa de piedra de tamaño superior al natural de la actual Turquía data de alrededor del 9000 a. C., y las Estatuas de 'Ain Ghazal de alrededor del 7200 y 6500 a. C. Proceden de la actual Jordania , están hechas de yeso de cal y cañas y tienen aproximadamente la mitad del tamaño natural; hay 15 estatuas, algunas con dos cabezas una al lado de la otra, y 15 bustos. Se han encontrado pequeñas figuras de arcilla de personas y animales en muchos yacimientos de Oriente Próximo del Neolítico precerámico , y representan el comienzo de una tradición más o menos continua en la región.

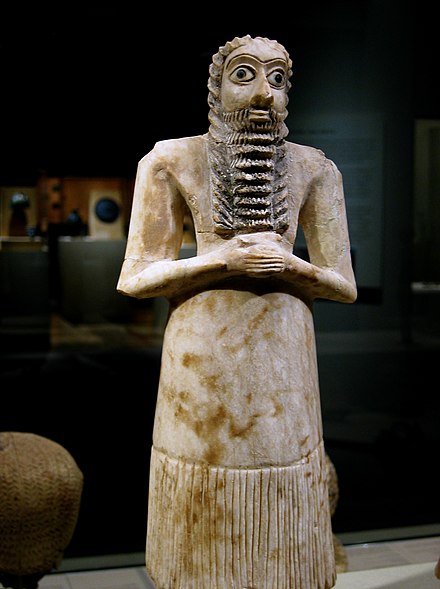

El período protoliterario en Mesopotamia , dominado por Uruk , vio la producción de obras sofisticadas como el vaso Warka y los sellos cilíndricos . La leona de Guennol es una pequeña figura de piedra caliza excepcional de Elam de alrededor de 3000-2800 a. C., mitad humana y mitad leona. [28] Un poco más tarde hay una serie de figuras de sacerdotes y adoradores de ojos grandes, principalmente en alabastro y de hasta un pie de altura, que asistían a imágenes de culto del templo de la deidad, pero muy pocas de estas han sobrevivido. [29] Las esculturas del período sumerio y acadio generalmente tenían ojos grandes y fijos, y largas barbas en los hombres. También se han encontrado muchas obras maestras en el Cementerio Real de Ur (c. 2650 a. C.), incluidas las dos figuras de un carnero en un matorral , el toro de cobre y la cabeza de un toro en una de las liras de Ur . [30]

De los muchos períodos posteriores al ascenso del Imperio neoasirio en el siglo X a. C., el arte mesopotámico sobrevive en varias formas: sellos cilíndricos , figuras relativamente pequeñas en bulto redondo y relieves de varios tamaños, incluidas placas baratas de cerámica moldeada para el hogar, algunas religiosas y otras aparentemente no. [31] El relieve de Burney es una placa de terracota inusualmente elaborada y relativamente grande (20 x 15 pulgadas, 50 x 37 cm) de una diosa alada desnuda con pies de ave rapaz y búhos y leones acompañantes. Procede del siglo XVIII o XIX a. C. y también puede estar moldeado. [32] También se encuentran estelas de piedra , ofrendas votivas o probablemente conmemorativas de victorias y que muestran fiestas en templos que, a diferencia de los más oficiales, carecen de inscripciones que las expliquen; [33] La Estela fragmentaria de los Buitres es un ejemplo temprano del tipo inscrito, [34] y el Obelisco Negro Asirio de Salmanasar III es un ejemplo tardío, grande y sólido. [35]

La conquista de toda Mesopotamia y gran parte del territorio circundante por los asirios creó un estado más grande y más rico que el que la región había conocido antes, y un arte muy grandioso en palacios y lugares públicos, sin duda en parte destinado a igualar el esplendor del arte del vecino imperio egipcio. A diferencia de los estados anteriores, los asirios podían usar piedra fácilmente tallada del norte de Irak, y lo hicieron en gran cantidad. Los asirios desarrollaron un estilo de esquemas extremadamente grandes de bajorrelieves narrativos muy finamente detallados en piedra para palacios, con escenas de guerra o caza; el Museo Británico tiene una colección excepcional, que incluye la Cacería del León de Asurbanipal y los relieves de Laquis que muestran una campaña. Produjeron muy poca escultura en bulto redondo, excepto figuras colosales de guardianes del lamassu con cabeza humana , que están esculpidas en alto relieve en dos lados de un bloque rectangular, con las cabezas efectivamente en bulto redondo (y también cinco piernas, de modo que ambas vistas parecen completas). Incluso antes de dominar la región, habían continuado la tradición del sello cilíndrico con diseños a menudo excepcionalmente enérgicos y refinados. [36]

La escultura monumental del antiguo Egipto es mundialmente famosa, pero existen obras pequeñas, refinadas y delicadas en un número mucho mayor. Los egipcios usaban la técnica distintiva del relieve hundido , que se adapta bien a la luz solar muy brillante. Las figuras principales en relieves se adhieren a la misma convención de figura que en la pintura, con las piernas separadas (cuando no están sentados) y la cabeza mostrada de lado, pero el torso de frente, y un conjunto estándar de proporciones que componen la figura, usando 18 "puños" para ir desde el suelo hasta la línea del cabello en la frente. [37] Esto aparece ya en la Paleta de Narmer de la Dinastía I. Sin embargo, allí como en otros lugares la convención no se usa para figuras menores que se muestran realizando alguna actividad, como los cautivos y los cadáveres. [38] Otras convenciones hacen que las estatuas de hombres sean más oscuras que las de mujeres. Las estatuas de retratos muy convencionalizadas aparecen desde la dinastía II, antes del 2780 a. C., [39] y con la excepción del arte del período de Amarna de Ahkenaten , [40] y algunos otros períodos como la dinastía XII, los rasgos idealizados de los gobernantes, al igual que otras convenciones artísticas egipcias, cambiaron poco hasta después de la conquista griega. [41]

Los faraones egipcios siempre fueron considerados deidades, pero otras deidades son mucho menos comunes en grandes estatuas, excepto cuando representan al faraón como otra deidad; sin embargo, las otras deidades se muestran con frecuencia en pinturas y relieves. La famosa fila de cuatro estatuas colosales fuera del templo principal de Abu Simbel muestra cada una a Ramsés II , un esquema típico, aunque aquí excepcionalmente grande. [42] Las pequeñas figuras de deidades, o sus personificaciones animales, son muy comunes y se encuentran en materiales populares como la cerámica. La mayoría de las esculturas más grandes sobreviven de los templos o tumbas egipcias ; hacia la dinastía IV (2680-2565 a. C.) a más tardar, la idea de la estatua Ka estaba firmemente establecida. Estas se colocaban en tumbas como un lugar de descanso para la porción ka del alma , por lo que tenemos un buen número de estatuas menos convencionalizadas de administradores adinerados y sus esposas, muchas de ellas en madera, ya que Egipto es uno de los pocos lugares del mundo donde el clima permite que la madera sobreviva durante milenios. Las llamadas cabezas de reserva , cabezas lisas y sin pelo, son especialmente naturalistas. Las tumbas más antiguas también contenían pequeños modelos de esclavos, animales, edificios y objetos como barcos necesarios para que el difunto continuara su estilo de vida en el más allá, y más tarde figuras de Ushabti . [43]

El primer estilo distintivo de la escultura griega antigua se desarrolló en el período de las Cícladas , en la Edad del Bronce Temprano (tercer milenio a. C.), donde las figuras de mármol, generalmente femeninas y pequeñas, se representan en un estilo geométrico elegantemente simplificado. La pose más típica es una pose de pie con los brazos cruzados al frente, pero otras figuras se muestran en poses diferentes, incluida una figura complicada de un arpista sentado en una silla. [44]

Las culturas minoica y micénica posteriores desarrollaron aún más la escultura, bajo la influencia de Siria y otros lugares, pero es en el período Arcaico posterior , alrededor del 650 a. C., cuando se desarrollaron los kouros . Se trata de grandes estatuas de jóvenes desnudos que se encuentran en templos y tumbas, siendo la kore el equivalente femenino vestido, con el pelo elaborado; ambos tienen la " sonrisa arcaica ". Parecen haber cumplido varias funciones, quizás a veces representando deidades y a veces a la persona enterrada en una tumba, como en el caso de los Kroisos Kouros . Están claramente influenciados por los estilos egipcio y sirio, pero los artistas griegos estaban mucho más dispuestos a experimentar con el estilo.

Durante el siglo VI la escultura griega se desarrolló rápidamente, volviéndose más naturalista y con poses de figuras mucho más activas y variadas en escenas narrativas, aunque todavía dentro de convenciones idealizadas. Se añadieron frontones esculpidos a los templos , incluido el Partenón de Atenas, donde los restos del frontón de alrededor de 520 que usaba figuras en bulto redondo se usaron afortunadamente como relleno para nuevos edificios después del saqueo persa en 480 a. C., y se recuperaron a partir de la década de 1880 en estado fresco y sin intemperie. Otros restos significativos de escultura arquitectónica provienen de Paestum en Italia, Corfú , Delfos y el Templo de Afea en Egina (gran parte ahora en Múnich ). [45] La mayoría de las esculturas griegas originalmente incluían al menos algo de color; el Museo Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek en Copenhague, Dinamarca, ha realizado una amplia investigación y recreación de los colores originales. [46] [47]

Hay menos restos originales de la primera fase del período clásico, a menudo llamado estilo severo ; las estatuas exentas ahora se hacían principalmente en bronce, que siempre tuvo valor como chatarra. El estilo severo duró desde alrededor de 500 en relieves, y poco después 480 en estatuas, hasta aproximadamente 450. Las poses relativamente rígidas de las figuras se relajaron, y las posiciones de giro asimétricas y las vistas oblicuas se volvieron comunes y buscadas deliberadamente. Esto se combinó con una mejor comprensión de la anatomía y la estructura armoniosa de las figuras esculpidas, y la búsqueda de la representación naturalista como objetivo, que no había estado presente antes. Las excavaciones en el Templo de Zeus, Olimpia desde 1829 han revelado el grupo más grande de restos, de aproximadamente 460, de los cuales muchos están en el Louvre . [48]

El período del "Clásico Superior" duró sólo unas décadas, desde aproximadamente 450 hasta 400, pero ha tenido una influencia trascendental en el arte y conserva un prestigio especial, a pesar de un número muy restringido de supervivencias originales. Las obras más conocidas son los mármoles del Partenón , tradicionalmente (desde Plutarco ) ejecutados por un equipo dirigido por el escultor griego antiguo más famoso Fidias , activo desde aproximadamente 465-425, que en su propia época fue más famoso por su colosal estatua criselefantina de Zeus en Olimpia (c. 432), una de las Siete Maravillas del Mundo Antiguo , su Atenea Partenos (438), la imagen de culto del Partenón , y Atenea Prómaco , una colosal figura de bronce que se encontraba junto al Partenón; todas estas se han perdido, pero se conocen a partir de muchas representaciones. También se le atribuye la creación de algunas estatuas de bronce de tamaño natural conocidas sólo a partir de copias posteriores cuya identificación es controvertida, incluido el Hermes de Ludovisi . [49]

El estilo clásico alto continuó desarrollando el realismo y la sofisticación en la figura humana, y mejoró la representación de los drapeados (ropa), utilizándolos para aumentar el impacto de las poses activas. Las expresiones faciales solían ser muy contenidas, incluso en las escenas de combate. La composición de grupos de figuras en relieves y frontones combinaba complejidad y armonía de una manera que tuvo una influencia permanente en el arte occidental. El relieve podía ser muy alto, de hecho, como en la ilustración del Partenón que se muestra a continuación, donde la mayor parte de la pierna del guerrero está completamente separada del fondo, al igual que las partes faltantes; un relieve tan alto hacía que las esculturas fueran más propensas a sufrir daños. [50] El estilo clásico tardío desarrolló la estatua femenina desnuda exenta, supuestamente una innovación de Praxíteles , y desarrolló poses cada vez más complejas y sutiles que eran interesantes cuando se veían desde varios ángulos, así como rostros más expresivos; ambas tendencias se llevarían mucho más lejos en el período helenístico. [51]

The Hellenistic period is conventionally dated from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, and ending either with the final conquest of the Greek heartlands by Rome in 146 BCE or with the final defeat of the last remaining successor-state to Alexander's empire after the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, which also marks the end of Republican Rome.[52] It is thus much longer than the previous periods, and includes at least two major phases: a "Pergamene" style of experimentation, exuberance and some sentimentality and vulgarity, and in the 2nd century BCE a classicising return to a more austere simplicity and elegance; beyond such generalizations dating is typically very uncertain, especially when only later copies are known, as is usually the case. The initial Pergamene style was not especially associated with Pergamon, from which it takes its name, but the very wealthy kings of that state were among the first to collect and also copy Classical sculpture, and also commissioned much new work, including the famous Pergamon Altar whose sculpture is now mostly in Berlin and which exemplifies the new style, as do the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (another of the Seven Wonders), the famous Laocoön and his Sons in the Vatican Museums, a late example, and the bronze original of The Dying Gaul (illustrated at top), which we know was part of a group actually commissioned for Pergamon in about 228 BCE, from which the Ludovisi Gaul was also a copy. The group called the Farnese Bull, possibly a 2nd-century marble original, is still larger and more complex,[53]

Hellenistic sculpture greatly expanded the range of subjects represented, partly as a result of greater general prosperity, and the emergence of a very wealthy class who had large houses decorated with sculpture, although we know that some examples of subjects that seem best suited to the home, such as children with animals, were in fact placed in temples or other public places. For a much more popular home decoration market there were Tanagra figurines, and those from other centres where small pottery figures were produced on an industrial scale, some religious but others showing animals and elegantly dressed ladies. Sculptors became more technically skilled in representing facial expressions conveying a wide variety of emotions and the portraiture of individuals, as well representing different ages and races. The reliefs from the Mausoleum are rather atypical in that respect; most work was free-standing, and group compositions with several figures to be seen in the round, like the Laocoon and the Pergamon group celebrating victory over the Gauls became popular, having been rare before. The Barberini Faun, showing a satyr sprawled asleep, presumably after drink, is an example of the moral relaxation of the period, and the readiness to create large and expensive sculptures of subjects that fall short of the heroic.[54]

After the conquests of Alexander Hellenistic culture was dominant in the courts of most of the Near East, and some of Central Asia, and increasingly being adopted by European elites, especially in Italy, where Greek colonies initially controlled most of the South. Hellenistic art, and artists, spread very widely, and was especially influential in the expanding Roman Republic and when it encountered Buddhism in the easternmost extensions of the Hellenistic area. The massive so-called Alexander Sarcophagus found in Sidon in modern Lebanon, was probably made there at the start of the period by expatriate Greek artists for a Hellenized Persian governor.[55] The wealth of the period led to a greatly increased production of luxury forms of small sculpture, including engraved gems and cameos, jewellery, and gold and silverware.

Early Roman art was influenced by the art of Greece and that of the neighbouring Etruscans, themselves greatly influenced by their Greek trading partners. An Etruscan speciality was near life size tomb effigies in terracotta, usually lying on top of a sarcophagus lid propped up on one elbow in the pose of a diner in that period. As the expanding Roman Republic began to conquer Greek territory, at first in Southern Italy and then the entire Hellenistic world except for the Parthian far east, official and patrician sculpture became largely an extension of the Hellenistic style, from which specifically Roman elements are hard to disentangle, especially as so much Greek sculpture survives only in copies of the Roman period.[56] By the 2nd century BCE, "most of the sculptors working at Rome" were Greek,[57] often enslaved in conquests such as that of Corinth (146 BCE), and sculptors continued to be mostly Greeks, often slaves, whose names are very rarely recorded. Vast numbers of Greek statues were imported to Rome, whether as booty or the result of extortion or commerce, and temples were often decorated with re-used Greek works.[58]

A native Italian style can be seen in the tomb monuments, which very often featured portrait busts, of prosperous middle-class Romans, and portraiture is arguably the main strength of Roman sculpture. There are no survivals from the tradition of masks of ancestors that were worn in processions at the funerals of the great families and otherwise displayed in the home, but many of the busts that survive must represent ancestral figures, perhaps from the large family tombs like the Tomb of the Scipios or the later mausolea outside the city. The famous bronze head supposedly of Lucius Junius Brutus is very variously dated, but taken as a very rare survival of Italic style under the Republic, in the preferred medium of bronze.[59] Similarly stern and forceful heads are seen on coins of the Late Republic, and in the Imperial period coins as well as busts sent around the Empire to be placed in the basilicas of provincial cities were the main visual form of imperial propaganda; even Londinium had a near-colossal statue of Nero, though far smaller than the 30-metre-high Colossus of Nero in Rome, now lost.[60]

The Romans did not generally attempt to compete with free-standing Greek works of heroic exploits from history or mythology, but from early on produced historical works in relief, culminating in the great Roman triumphal columns with continuous narrative reliefs winding around them, of which those commemorating Trajan (CE 113) and Marcus Aurelius (by 193) survive in Rome, where the Ara Pacis ("Altar of Peace", 13 BCE) represents the official Greco-Roman style at its most classical and refined. Among other major examples are the earlier re-used reliefs on the Arch of Constantine and the base of the Column of Antoninus Pius (161),[61] Campana reliefs were cheaper pottery versions of marble reliefs and the taste for relief was from the imperial period expanded to the sarcophagus. All forms of luxury small sculpture continued to be patronized, and quality could be extremely high, as in the silver Warren Cup, glass Lycurgus Cup, and large cameos like the Gemma Augustea, Gonzaga Cameo and the "Great Cameo of France".[62] For a much wider section of the population, moulded relief decoration of pottery vessels and small figurines were produced in great quantity and often considerable quality.[63]

After moving through a late 2nd-century "baroque" phase,[64] in the 3rd century, Roman art largely abandoned, or simply became unable to produce, sculpture in the classical tradition, a change whose causes remain much discussed. Even the most important imperial monuments now showed stumpy, large-eyed figures in a harsh frontal style, in simple compositions emphasizing power at the expense of grace. The contrast is famously illustrated in the Arch of Constantine of 315 in Rome, which combines sections in the new style with roundels in the earlier full Greco-Roman style taken from elsewhere, and the Four Tetrarchs (c. 305) from the new capital of Constantinople, now in Venice. Ernst Kitzinger found in both monuments the same "stubby proportions, angular movements, an ordering of parts through symmetry and repetition and a rendering of features and drapery folds through incisions rather than modelling... The hallmark of the style wherever it appears consists of an emphatic hardness, heaviness and angularity—in short, an almost complete rejection of the classical tradition".[65]

This revolution in style shortly preceded the period in which Christianity was adopted by the Roman state and the great majority of the people, leading to the end of large religious sculpture, with large statues now only used for emperors. However, rich Christians continued to commission reliefs for sarcophagi, as in the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, and very small sculpture, especially in ivory, was continued by Christians, building on the style of the consular diptych.[66]

The Early Christians were opposed to monumental religious sculpture, though continuing Roman traditions in portrait busts and sarcophagus reliefs, as well as smaller objects such as the consular diptych. Such objects, often in valuable materials, were also the main sculptural traditions (as far as is known) of the barbaric civilizations of the Migration period, as seen in the objects found in the 6th-century burial treasure at Sutton Hoo, and the jewellery of Scythian art and the hybrid Christian and animal style productions of Insular art. Following the continuing Byzantine tradition, Carolingian art revived ivory carving, often in panels for the treasure bindings of grand illuminated manuscripts, as well as crozier heads and other small fittings.

Byzantine art, though producing superb ivory reliefs and architectural decorative carving, never returned to monumental sculpture, or even much small sculpture in the round.[67] However, in the West during the Carolingian and Ottonian periods there was the beginnings of a production of monumental statues, in courts and major churches. This gradually spread; by the late 10th and 11th century there are records of several apparently life-size sculptures in Anglo-Saxon churches, probably of precious metal around a wooden frame, like the Golden Madonna of Essen. No Anglo-Saxon example has survived,[68] and survivals of large non-architectural sculpture from before 1,000 are exceptionally rare. Much the finest is the Gero Cross, of 965–970, which is a crucifix, which was evidently the commonest type of sculpture; Charlemagne had set one up in the Palatine Chapel in Aachen around 800. These continued to grow in popularity, especially in Germany and Italy. The runestones of the Nordic world, the Pictish stones of Scotland and possibly the high cross reliefs of Christian Great Britain, were northern sculptural traditions that bridged the period of Christianization.

Beginning in roughly 1000 A.D., there was a rebirth of artistic production in all Europe, led by general economic growth in production and commerce, and the new style of Romanesque art was the first medieval style to be used in the whole of Western Europe. The new cathedrals and pilgrim's churches were increasingly decorated with architectural stone reliefs, and new focuses for sculpture developed, such as the tympanum over church doors in the 12th century, and the inhabited capital with figures and often narrative scenes. Outstanding abbey churches with sculpture include in France Vézelay and Moissac and in Spain Silos.[69]

Romanesque art was characterised by a very vigorous style in both sculpture and painting. The capitals of columns were never more exciting than in this period, when they were often carved with complete scenes with several figures.[70] The large wooden crucifix was a German innovation right at the start of the period, as were free-standing statues of the enthroned Madonna, but the high relief was above all the sculptural mode of the period. Compositions usually had little depth, and needed to be flexible to squeeze themselves into the shapes of capitals, and church typanums; the tension between a tightly enclosing frame, from which the composition sometimes escapes, is a recurrent theme in Romanesque art. Figures still often varied in size in relation to their importance portraiture hardly existed.

Objects in precious materials such as ivory and metal had a very high status in the period, much more so than monumental sculpture — we know the names of more makers of these than painters, illuminators or architect-masons. Metalwork, including decoration in enamel, became very sophisticated, and many spectacular shrines made to hold relics have survived, of which the best known is the Shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne Cathedral by Nicholas of Verdun. The bronze Gloucester candlestick and the brass font of 1108–17 now in Liège are superb examples, very different in style, of metal casting, the former highly intricate and energetic, drawing on manuscript painting, while the font shows the Mosan style at its most classical and majestic. The bronze doors, a triumphal column and other fittings at Hildesheim Cathedral, the Gniezno Doors, and the doors of the Basilica di San Zeno in Verona are other substantial survivals. The aquamanile, a container for water to wash with, appears to have been introduced to Europe in the 11th century, and often took fantastic zoomorphic forms; surviving examples are mostly in brass. Many wax impressions from impressive seals survive on charters and documents, although Romanesque coins are generally not of great aesthetic interest.[71]

The Cloisters Cross is an unusually large ivory crucifix, with complex carving including many figures of prophets and others, which has been attributed to one of the relatively few artists whose name is known, Master Hugo, who also illuminated manuscripts. Like many pieces it was originally partly coloured. The Lewis chessmen are well-preserved examples of small ivories, of which many pieces or fragments remain from croziers, plaques, pectoral crosses and similar objects.

The Gothic period is essentially defined by Gothic architecture, and does not entirely fit with the development of style in sculpture in either its start or finish. The facades of large churches, especially around doors, continued to have large typanums, but also rows of sculpted figures spreading around them. The statues on the Western (Royal) Portal at Chartres Cathedral (c. 1145) show an elegant but exaggerated columnar elongation, but those on the south transept portal, from 1215 to 1220, show a more naturalistic style and increasing detachment from the wall behind, and some awareness of the classical tradition. These trends were continued in the west portal at Reims Cathedral of a few years later, where the figures are almost in the round, as became usual as Gothic spread across Europe.[72]

In Italy Nicola Pisano (1258–1278) and his son Giovanni developed a style that is often called Proto-Renaissance, with unmistakable influence from Roman sarcophagi and sophisticated and crowded compositions, including a sympathetic handling of nudity, in relief panels on their Siena Cathedral Pulpit (1265–68), Pulpit in the Pisa Baptistery (1260), the Fontana Maggiore in Perugia, and Giovanni's pulpit in Pistoia of 1301.[73] Another revival of classical style is seen in the International Gothic work of Claus Sluter and his followers in Burgundy and Flanders around 1400.[74] Late Gothic sculpture continued in the North, with a fashion for very large wooden sculpted altarpieces with increasingly virtuoso carving and large numbers agitated expressive figures; most surviving examples are in Germany, after much iconoclasm elsewhere. Tilman Riemenschneider, Veit Stoss and others continued the style well into the 16th century, gradually absorbing Italian Renaissance influences.[75]

Life-size tomb effigies in stone or alabaster became popular for the wealthy, and grand multi-level tombs evolved, with the Scaliger Tombs of Verona so large they had to be moved outside the church. By the 15th century there was an industry exporting Nottingham alabaster altar reliefs in groups of panels over much of Europe for economical parishes who could not afford stone retables.[76] Small carvings, for a mainly lay and often female market, became a considerable industry in Paris and some other centres. Types of ivories included small devotional polyptychs, single figures, especially of the Virgin, mirror-cases, combs, and elaborate caskets with scenes from Romances, used as engagement presents.[77] The very wealthy collected extravagantly elaborate jewelled and enamelled metalwork, both secular and religious, like the Duc de Berry's Holy Thorn Reliquary, until they ran short of money, when they were melted down again for cash.[78]

Renaissance sculpture proper is often taken to begin with the famous competition for the doors of the Florence Baptistry in 1403, from which the trial models submitted by the winner, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and Filippo Brunelleschi survive. Ghiberti's doors are still in place, but were undoubtedly eclipsed by his second pair for the other entrance, the so-called Gates of Paradise, which took him from 1425 to 1452, and are dazzlingly confident classicizing compositions with varied depths of relief allowing extensive backgrounds.[79] The intervening years had seen Ghiberti's early assistant Donatello develop with seminal statues including his Davids in marble (1408–09) and bronze (1440s), and his Equestrian statue of Gattamelata, as well as reliefs.[80] A leading figure in the later period was Andrea del Verrocchio, best known for his equestrian statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni in Venice;[81] his pupil Leonardo da Vinci designed an equine sculpture in 1482 The Horse for Milan, but only succeeded in making a 24-foot (7.3 m) clay model which was destroyed by French archers in 1499, and his other ambitious sculptural plans were never completed.[82]

The period was marked by a great increase in patronage of sculpture by the state for public art and by the wealthy for their homes; especially in Italy, public sculpture remains a crucial element in the appearance of historic city centres. Church sculpture mostly moved inside just as outside public monuments became common. Portrait sculpture, usually in busts, became popular in Italy around 1450, with the Neapolitan Francesco Laurana specializing in young women in meditative poses, while Antonio Rossellino and others more often depicted knobbly-faced men of affairs, but also young children.[83] The portrait medal invented by Pisanello also often depicted women; relief plaquettes were another new small form of sculpture in cast metal.

Michelangelo was an active sculptor from about 1500 to 1520, and his great masterpieces including his David, Pietà, Moses, and pieces for the Tomb of Pope Julius II and Medici Chapel could not be ignored by subsequent sculptors. His iconic David (1504) has a contrapposto pose, borrowed from classical sculpture. It differs from previous representations of the subject in that David is depicted before his battle with Goliath and not after the giant's defeat. Instead of being shown victorious, as Donatello and Verocchio had done, David looks tense and battle ready.[84]

As in painting, early Italian Mannerist sculpture was very largely an attempt to find an original style that would top the achievement of the High Renaissance, which in sculpture essentially meant Michelangelo, and much of the struggle to achieve this was played out in commissions to fill other places in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, next to Michelangelo's David. Baccio Bandinelli took over the project of Hercules and Cacus from the master himself, but it was little more popular than it is now, and maliciously compared by Benvenuto Cellini to "a sack of melons", though it had a long-lasting effect in apparently introducing relief panels on the pedestal of statues for the first time. Like other works of his, and other Mannerists, it removes far more of the original block than Michelangelo would have done.[85] Cellini's bronze Perseus with the head of Medusa is certainly a masterpiece, designed with eight angles of view, another Mannerist characteristic, but is indeed mannered compared to the Davids of Michelangelo and Donatello.[86] Originally a goldsmith, his famous gold and enamel Salt Cellar (1543) was his first sculpture, and shows his talent at its best.[87] As these examples show, the period extended the range of secular subjects for large works beyond portraits, with mythological figures especially favoured; previously these had mostly been found in small works.

Small bronze figures for collector's cabinets, often mythological subjects with nudes, were a popular Renaissance form at which Giambologna, originally Flemish but based in Florence, excelled in the later part of the century, also creating life-size sculptures, of which two joined the collection in the Piazza della Signoria. He and his followers devised elegant elongated examples of the figura serpentinata, often of two intertwined figures, that were interesting from all angles.[88]

.jpg/440px-Apollo_and_Daphne_(Bernini).jpg)

In Baroque sculpture, groups of figures assumed new importance, and there was a dynamic movement and energy of human forms— they spiralled around an empty central vortex, or reached outwards into the surrounding space. Baroque sculpture often had multiple ideal viewing angles, and reflected a general continuation of the Renaissance move away from the relief to sculpture created in the round, and designed to be placed in the middle of a large space—elaborate fountains such as Bernini's Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi (Rome, 1651), or those in the Gardens of Versailles were a Baroque speciality. The Baroque style was perfectly suited to sculpture, with Gian Lorenzo Bernini the dominating figure of the age in works such as The Ecstasy of St Theresa (1647–1652).[89] Much Baroque sculpture added extra-sculptural elements, for example, concealed lighting, or water fountains, or fused sculpture and architecture to create a transformative experience for the viewer. Artists saw themselves as in the classical tradition, but admired Hellenistic and later Roman sculpture, rather than that of the more "Classical" periods as they are seen today.[90]

The Protestant Reformation brought an almost total stop to religious sculpture in much of Northern Europe, and though secular sculpture, especially for portrait busts and tomb monuments, continued, the Dutch Golden Age has no significant sculptural component outside goldsmithing.[91] Partly in direct reaction, sculpture was as prominent in Roman Catholicism as in the late Middle Ages. Statues of rulers and the nobility became increasingly popular. In the 18th century much sculpture continued on Baroque lines—the Trevi Fountain was only completed in 1762. Rococo style was better suited to smaller works, and arguably found its ideal sculptural form in early European porcelain, and interior decorative schemes in wood or plaster such as those in French domestic interiors and Austrian and Bavarian pilgrimage churches.[92]

The Neoclassical style that arrived in the late 18th century gave great emphasis to sculpture. Jean-Antoine Houdon exemplifies the penetrating portrait sculpture the style could produce, and Antonio Canova's nudes the idealist aspect of the movement. The Neoclassical period was one of the great ages of public sculpture, though its "classical" prototypes were more likely to be Roman copies of Hellenistic sculptures. In sculpture, the most familiar representatives are the Italian Antonio Canova, the Englishman John Flaxman and the Dane Bertel Thorvaldsen. The European neoclassical manner also took hold in the United States, where its pinnacle occurred somewhat later and is exemplified in the sculptures of Hiram Powers.

Greco-Buddhist art is the artistic manifestation of Greco-Buddhism, a cultural syncretism between the Classical Greek culture and Buddhism, which developed over a period of close to 1000 years in Central Asia, between the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE, and the Islamic conquests of the 7th century CE. Greco-Buddhist art is characterized by the strong idealistic realism of Hellenistic art and the first representations of the Buddha in human form, which have helped define the artistic (and particularly, sculptural) canon for Buddhist art throughout the Asian continent up to the present. Though dating is uncertain, it appears that strongly Hellenistic styles lingered in the East for several centuries after they had declined around the Mediterranean, as late as the 5th century CE. Some aspects of Greek art were adopted while others did not spread beyond the Greco-Buddhist area; in particular the standing figure, often with a relaxed pose and one leg flexed, and the flying cupids or victories, who became popular across Asia as apsaras. Greek foliage decoration was also influential, with Indian versions of the Corinthian capital appearing.[93]

The origins of Greco-Buddhist art are to be found in the Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian kingdom (250–130 BCE), located in today's Afghanistan, from which Hellenistic culture radiated into the Indian subcontinent with the establishment of the small Indo-Greek kingdom (180–10 BCE). Under the Indo-Greeks and then the Kushans, the interaction of Greek and Buddhist culture flourished in the area of Gandhara, in today's northern Pakistan, before spreading further into India, influencing the art of Mathura, and then the Hindu art of the Gupta empire, which was to extend to the rest of South-East Asia. The influence of Greco-Buddhist art also spread northward towards Central Asia, strongly affecting the art of the Tarim Basin and the Dunhuang Caves, and ultimately the sculpted figure in China, Korea, and Japan.[94]

Chinese ritual bronzes from the Shang and Western Zhou dynasties come from a period of over a thousand years from c. 1500 BCE, and have exerted a continuing influence over Chinese art. They are cast with complex patterned and zoomorphic decoration, but avoid the human figure, unlike the huge figures only recently discovered at Sanxingdui.[95] The spectacular Terracotta Army was assembled for the tomb of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China from 221 to 210 BCE, as a grand imperial version of the figures long placed in tombs to enable the deceased to enjoy the same lifestyle in the afterlife as when alive, replacing actual sacrifices of very early periods. Smaller figures in pottery or wood were placed in tombs for many centuries afterwards, reaching a peak of quality in Tang dynasty tomb figures.[96] The tradition of unusually large pottery figures persisted in China, through Tang sancai tomb figures to later Buddhist statues such as the near life-size set of Yixian glazed pottery luohans and later figures for temples and tombs. These came to replace earlier equivalents in wood.

Native Chinese religions do not usually use cult images of deities, or even represent them, and large religious sculpture is nearly all Buddhist, dating mostly from the 4th to the 14th century, and initially using Greco-Buddhist models arriving via the Silk Road. Buddhism is also the context of all large portrait sculpture; in total contrast to some other areas, in medieval China even painted images of the emperor were regarded as private. Imperial tombs have spectacular avenues of approach lined with real and mythological animals on a scale matching Egypt, and smaller versions decorate temples and palaces.[97]

Small Buddhist figures and groups were produced to a very high quality in a range of media,[98] as was relief decoration of all sorts of objects, especially in metalwork and jade.[99] In the earlier periods, large quantities of sculpture were cut from the living rock in pilgrimage cave-complexes, and as outside rock reliefs. These were mostly originally painted. In notable contrast to literati painters, sculptors of all sorts were regarded as artisans and very few names are recorded.[100] From the Ming dynasty onwards, statuettes of religious and secular figures were produced in Chinese porcelain and other media, which became an important export.

Towards the end of the long Neolithic Jōmon period, some pottery vessels were "flame-rimmed" with extravagant extensions to the rim that can only be called sculptural,[103] and very stylized pottery dogū figures were produced, many with the characteristic "snow-goggle" eyes. During the Kofun period of the 3rd to 6th century CE, haniwa terracotta figures of humans and animals in a simplistic style were erected outside important tombs. The arrival of Buddhism in the 6th century brought with it sophisticated traditions in sculpture, Chinese styles mediated via Korea. The 7th-century Hōryū-ji and its contents have survived more intact than any East Asian Buddhist temple of its date, with works including a Shaka Trinity of 623 in bronze, showing the historical Buddha flanked by two bodhisattvas and also the Guardian Kings of the Four Directions.[104]

Jōchō is said to be one of the greatest Buddhist sculptors not only in Heian period but also in the history of Buddhist statues in Japan. Jōchō redefined the body shape of Buddha statues by perfecting the technique of "yosegi zukuri" (寄木造り) which is a combination of several woods. The peaceful expression and graceful figure of the Buddha statue that he made completed a Japanese style of sculpture of Buddha statues called "Jōchō yō" (Jōchō style, 定朝様) and determined the style of Japanese Buddhist statues of the later period. His achievement dramatically raised the social status of busshi (Buddhist sculptor) in Japan.[105]

In the Kamakura period, the Minamoto clan established the Kamakura shogunate and the samurai class virtually ruled Japan for the first time. Jocho's successors, sculptors of the Kei school of Buddhist statues, created realistic and dynamic statues to suit the tastes of samurai, and Japanese Buddhist sculpture reached its peak. Unkei, Kaikei, and Tankei were famous, and they made many new Buddha statues at many temples such as Kofuku-ji, where many Buddha statues had been lost in wars and fires.[106]

Almost all subsequent significant large sculpture in Japan was Buddhist, with some Shinto equivalents, and after Buddhism declined in Japan in the 15th century, monumental sculpture became largely architectural decoration and less significant.[107] However sculptural work in the decorative arts was developed to a remarkable level of technical achievement and refinement in small objects such as inro and netsuke in many materials, and metal tosogu or Japanese sword mountings. In the 19th century there were export industries of small bronze sculptures of extreme virtuosity, ivory and porcelain figurines, and other types of small sculpture, increasingly emphasizing technical accomplishment.

,_gupta_period,_krishna_battling_the_horse_demon_keshi,_5th_century.JPG/440px-Met,_india_(uttar_pradesh),_gupta_period,_krishna_battling_the_horse_demon_keshi,_5th_century.JPG)

The first known sculpture in the Indian subcontinent is from the Indus Valley civilization (3300–1700 BCE), found in sites at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa in modern-day Pakistan. These include the famous small bronze female dancer and the so-called Priest-king. However, such figures in bronze and stone are rare and greatly outnumbered by pottery figurines and stone seals, often of animals or deities very finely depicted. After the collapse of the Indus Valley civilization there is little record of sculpture until the Buddhist era, apart from a hoard of copper figures of (somewhat controversially) c. 1500 BCE from Daimabad.[108] Thus the great tradition of Indian monumental sculpture in stone appears to begin, relative to other cultures, and the development of Indian civilization, relatively late, with the reign of Asoka from 270 to 232 BCE, and the Pillars of Ashoka he erected around India, carrying his edicts and topped by famous sculptures of animals, mostly lions, of which six survive.[109] Large amounts of figurative sculpture, mostly in relief, survive from Early Buddhist pilgrimage stupas, above all Sanchi; these probably developed out of a tradition using wood that also embraced Hinduism.[110]

The pink sandstone Hindu, Jain and Buddhist sculptures of Mathura from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE reflected both native Indian traditions and the Western influences received through the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, and effectively established the basis for subsequent Indian religious sculpture.[110] The style was developed and diffused through most of India under the Gupta Empire (c. 320–550) which remains a "classical" period for Indian sculpture, covering the earlier Ellora Caves,[111] though the Elephanta Caves are probably slightly later.[112] Later large-scale sculpture remains almost exclusively religious, and generally rather conservative, often reverting to simple frontal standing poses for deities, though the attendant spirits such as apsaras and yakshi often have sensuously curving poses. Carving is often highly detailed, with an intricate backing behind the main figure in high relief. The celebrated bronzes of the Chola dynasty (c. 850–1250) from south India, many designed to be carried in processions, include the iconic form of Shiva as Nataraja,[113] with the massive granite carvings of Mahabalipuram dating from the previous Pallava dynasty.[114]

The sculpture of the region tends to be characterised by a high degree of ornamentation, as seen in the great monuments of Hindu and Buddhist Khmer sculpture (9th to 13th centuries) at Angkor Wat and elsewhere, the enormous 9th-century Buddhist complex at Borobudur in Java, and the Hindu monuments of Bali.[115] Both of these include many reliefs as well as figures in the round; Borobudur has 2,672 relief panels, 504 Buddha statues, many semi-concealed in openwork stupas, and many large guardian figures.

In Thailand and Laos, sculpture was mainly of Buddha images, often gilded, both large for temples and monasteries, and small figurines for private homes. Traditional sculpture in Myanmar emerged before the Bagan period. As elsewhere in the region, most of the wood sculptures of the Bagan and Ava periods have been lost.

Traditional Anitist sculptures from the Philippines are dominated by Anitist designs mirroring the medium used and the culture involved, while being highlighted by the environments where such sculptures are usually placed on. Christian and Islamic sculptures from the Philippines have different motifs compared to other Christian and Islamic sculptures elsewhere. In later periods Chinese influence predominated in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, and more wooden sculpture survives from across the region.

Islam is famously aniconic, so the vast majority of sculpture is arabesque decoration in relief or openwork, based on vegetable motifs, but tending to geometrical abstract forms. In the very early Mshatta Facade (740s), now mostly in Berlin, there are animals within the dense arabesques in high relief, and figures of animals and men in mostly low relief are found in conjunction with decoration on many later pieces in various materials, including metalwork, ivory and ceramics.[116]

Figures of animals in the round were often acceptable for works used in private contexts if the object was clearly practical, so medieval Islamic art contains many metal animals that are aquamaniles, incense burners or supporters for fountains, as in the stone lions supporting the famous one in the Alhambra, culminating in the largest medieval Islamic animal figure known, the Pisa Griffin. In the same way, luxury hardstone carvings such as dagger hilts and cups may be formed as animals, especially in Mughal art. The degree of acceptability of such relaxations of strict Islamic rules varies between periods and regions, with Islamic Spain, Persia and India often leading relaxation, and is typically highest in courtly contexts.[117]

Historically, with the exception of some monumental Egyptian sculpture, most African sculpture was created in wood and other organic materials that have not survived from earlier than a few centuries ago; older pottery figures are found from a number of areas. Masks are important elements in the art of many peoples, along with human figures, often highly stylized. There is a vast variety of styles, often varying within the same context of origin depending on the use of the object, but wide regional trends are apparent; sculpture is most common among "groups of settled cultivators in the areas drained by the Niger and Congo rivers" in West Africa.[118] Direct images of deities are relatively infrequent, but masks in particular are or were often made for religious ceremonies; today many are made for tourists as "airport art".[119] African masks were an influence on European Modernist art, which was inspired by their lack of concern for naturalistic depiction.

The Nubian Kingdom of Kush in modern Sudan was in close and often hostile contact with Egypt, and produced monumental sculpture mostly derivative of styles to the north. In West Africa, the earliest known sculptures are from the Nok culture which thrived between 500 BCE and 500 CE in modern Nigeria, with clay figures typically with elongated bodies and angular shapes. Later West African cultures developed bronze casting for reliefs to decorate palaces like the famous Benin Bronzes, and very fine naturalistic royal heads from around the Yoruba town of Ife in terracotta and metal from the 12th–14th centuries. Akan goldweights are a form of small metal sculptures produced over the period 1400–1900, some apparently representing proverbs and so with a narrative element rare in African sculpture, and royal regalia included impressive gold sculptured elements.[120]

Many West African figures are used in religious rituals and are often coated with materials placed on them for ceremonial offerings. The Mande-speaking peoples of the same region make pieces of wood with broad, flat surfaces and arms and legs are shaped like cylinders. In Central Africa, however, the main distinguishing characteristics include heart-shaped faces that are curved inward and display patterns of circles and dots.

Populations in the African Great Lakes are not known for their sculpture.[118] However, one style from the region is pole sculptures, carved in human shapes and decorated with geometric forms, while the tops are carved with figures of animals, people, and various objects. These poles are, then, placed next to graves and are associated with death and the ancestral world. The culture known from Great Zimbabwe left more impressive buildings than sculpture but the eight soapstone Zimbabwe Birds appear to have had a special significance and were mounted on monoliths. Modern Zimbabwean sculptors in soapstone have achieved considerable international success. Southern Africa's oldest known clay figures date from 400 to 600 CE and have cylindrical heads with a mixture of human and animal features.

The creation of sculptures in Ethiopia and Eritrea can be traced back to its ancient past with the kingdoms of Dʿmt and Aksum. Christian art was established in Ethiopia with the conversion from paganism to Christianity in the 4th century CE, during the reign of king Ezana of Axum.[121] Christian imagery decorated churches during the Asksumite period and later eras.[122] For instance, at Lalibela, life-size saints were carved into the Church of Bet Golgotha; by tradition these were made during the reign of the Zagwe ruler Gebre Mesqel Lalibela in the 12th century, but they were more likely crafted in the 15th century during the Solomonic dynasty.[123] However, the Church of Saint George, Lalibela, one of several examples of rock cut architecture at Lalibela containing intricate carvings, was built in the 10th–13th centuries as proven by archaeology.[124]