En la religión y el mito de la antigua Grecia , Dioniso ( / d aɪ . ə ˈ n aɪ s ə s / ; griego antiguo : Διόνυσος Dionysos ) es el dios de la vinificación, los huertos y las frutas, la vegetación, la fertilidad, la festividad , la locura, la locura ritual, el éxtasis religioso y el teatro . [3] [4] También era conocido como Baco ( / ˈ b æ k ə s / o / ˈ b ɑː k ə s / ; griego antiguo : Βάκχος Bacchos ) por los griegos (un nombre adoptado más tarde por los romanos ) por un frenesí que se dice que induce llamado baccheia . [5] Como Dionisio Eleuterio ("el liberador"), su vino, su música y su danza extática liberan a sus seguidores del miedo y la preocupación autoconscientes, y subvierten las restricciones opresivas de los poderosos. [6] Su tirso , un cetro de tallo de hinojo, a veces envuelto con hiedra y goteando miel, es a la vez una varita benéfica y un arma utilizada para destruir a quienes se oponen a su culto y a las libertades que representa. [7] Se cree que quienes participan de sus misterios son poseídos y empoderados por el propio dios. [8]

Sus orígenes son inciertos y sus cultos adoptaron muchas formas; algunos son descritos por fuentes antiguas como tracios , otros como griegos. [9] [10] [11] En el orfismo , era hijo de Zeus y Perséfone , un aspecto ctónico o del inframundo de Zeus, o el hijo nacido dos veces de Zeus y la mortal Sémele . Los misterios eleusinos lo identifican con Yaco , el hijo o esposo de Deméter . La mayoría de los relatos dicen que nació en Tracia, viajó al extranjero y llegó a Grecia como extranjero. Su atributo de "extranjería" como un dios forastero que llega puede ser inherente y esencial a sus cultos, ya que es un dios de la epifanía , a veces llamado "el dios que viene". [12]

El vino era un elemento religioso central en el culto de Dioniso y era su encarnación terrenal. [13] El vino podía aliviar el sufrimiento, traer alegría e inspirar la locura divina. [14] Los festivales de Dioniso incluían la representación de dramas sagrados que representaban sus mitos, la fuerza impulsora inicial detrás del desarrollo del teatro en la cultura occidental . [15] El culto de Dioniso es también un "culto de las almas"; sus ménades alimentan a los muertos mediante ofrendas de sangre, y él actúa como un comunicador divino entre los vivos y los muertos. [16] A veces se lo clasifica como un dios que muere y resucita . [17]

Los romanos identificaban a Baco con su propio Liber Pater , el "Padre Libre" de la fiesta Liberalia , patrón de la vinicultura, el vino y la fertilidad masculina, y guardián de las tradiciones, rituales y libertades ligadas a la mayoría de edad y la ciudadanía, pero el estado romano trataba las fiestas populares e independientes de Baco ( Bacanales ) como subversivas, en parte porque su libre mezcla de clases y géneros transgredía las restricciones sociales y morales tradicionales. La celebración de las Bacanales se convirtió en una ofensa capital, excepto en las formas atenuadas y las congregaciones muy reducidas aprobadas y supervisadas por el Estado. Las fiestas de Baco se fusionaron con las de Liber y Dionisio.

El prefijo dio- en griego antiguo Διόνυσος ( Diónūsos ; [di.ó.nyː.sos] ) ha sido asociado desde la antigüedad con Zeus ( genitivo Dios ), y las variantes del nombre parecen apuntar a un *Dios-nysos original . [18] La atestación más antigua es la forma dativa griega micénica 𐀇𐀺𐀝𐀰 (di-wo-nu-so) , [19] [18] que aparece en dos tablillas que se habían encontrado en Pilos micénica y que datan del siglo XII o XIII a. C. En ese momento, no podía haber certeza sobre si esto era de hecho un teónimo , [20] [21] pero las excavaciones greco-suecas de 1989-90 en la colina Kastelli , Chania, desenterraron, entre otros , cuatro artefactos con inscripciones en Lineal B; entre ellos, se cree que la inscripción en el elemento KH Gq 5 confirma el culto temprano de Dioniso. [22] En griego micénico, la forma de Zeus es di-wo . [23] El segundo elemento -nūsos es de origen desconocido. [18] Quizás esté asociado con el monte Nisa , el lugar de nacimiento del dios en la mitología griega, donde fue amamantado por ninfas (las Nisíadas ), [24] aunque Ferécides de Siros había postulado nũsa como una palabra arcaica para "árbol" en el siglo VI a. C. [25] [26] En un vaso de Sófilos las Nisíadas se nombran νύσαι ( nusae ). [27] Kretschmer afirmó que νύση ( nusē ) es una palabra tracia que tiene el mismo significado que νύμφη ( nýmphē ), una palabra similar a νυός ( nuos ) (nuera, o novia, IE *snusós, sánscrito. snusā ). [28] Sugirió que la forma masculina es νῦσος ( nūsos ) y esto haría de Dioniso el "hijo de Zeus". [27] Jane Ellen Harrison creía que el nombre Dioniso significa "joven Zeus". [29] Robert SP Beekes ha sugerido un origen pregriego del nombre, ya que todos los intentos de encontrar un origen indoeuropeo La etimología es dudosa. [19] [18]

Las variantes posteriores incluyen a Dionūsos y Diōnūsos en Beocia ; Dien(n)ūsos en Tesalia ; Deonūsos y Deunūsos en Jonia ; y Dinnūsos en Eolia , además de otras variantes. Un prefijo Dio- se encuentra en otros nombres, como el de los Dioscuros , y puede derivar de Dios , el genitivo del nombre de Zeus . [30]

Nonnus, en su Dionysiaca , escribe que el nombre Dionisio significa "Zeus cojo" y que Hermes nombró así al recién nacido Dionisio, "porque Zeus mientras llevaba su carga levantó un pie cojeando por el peso de su muslo, y nysos en lengua siracusana significa cojeando". [31] En su nota a estas líneas, WHD Rouse escribe "No es necesario decir que estas etimologías son erróneas". [31] La Suda , una enciclopedia bizantina basada en fuentes clásicas, afirma que Dionisio fue llamado así "por lograr [διανύειν] para cada uno de los que viven la vida salvaje. O por proporcionar [διανοεῖν] todo para los que viven la vida salvaje". [32]

Los académicos del siglo XIX, utilizando el estudio de la filología y la mitología comparada , a menudo consideraban a Dioniso como una deidad extranjera que solo fue aceptada a regañadientes en el panteón griego estándar en una fecha relativamente tardía, basándose en sus mitos que a menudo involucran este tema: un dios que pasa gran parte de su tiempo en la tierra en el extranjero y lucha por ser aceptado cuando regresa a Grecia. Sin embargo, evidencia más reciente ha demostrado que Dioniso fue de hecho uno de los primeros dioses atestiguados en la cultura griega continental. [14] Los primeros registros escritos del culto a Dioniso provienen de la Grecia micénica , específicamente en y alrededor del Palacio de Néstor en Pilos , que data de alrededor de 1300 a. C. [33] Los detalles de cualquier religión que rodeara a Dioniso en este período son escasos, y la mayoría de las evidencias vienen solo en forma de su nombre, escrito como di-wo-nu-su-jo ("Dionysoio" = 'de Dioniso') en Lineal B , preservado en fragmentos de tablillas de arcilla que indican una conexión con ofrendas o pagos de vino, que se describía como "de Dioniso". También se han descubierto referencias a "mujeres de Oinoa", el "lugar del vino", que pueden corresponder a las mujeres dionisíacas de períodos posteriores. [33]

Otros registros micénicos de Pilos registran el culto a un dios llamado Eleuther, que era hijo de Zeus, y a quien se le sacrificaban bueyes. El vínculo tanto con Zeus como con los bueyes, así como los vínculos etimológicos entre el nombre Eleuther o Eleutheros con el nombre latino Liber Pater , indican que este puede haber sido otro nombre para Dioniso. Según Károly Kerényi , estas pistas sugieren que incluso en el siglo XIII a. C., la religión central de Dioniso estaba vigente, al igual que sus mitos importantes. En Cnosos , en la Creta minoica , a los hombres a menudo se les daba el nombre de "Penteo", que es una figura en el mito dionisíaco posterior y que también significa "sufrimiento". Kerényi sostuvo que dar ese nombre a un hijo implica una fuerte conexión religiosa, posiblemente no como el personaje independiente de Penteo que sufre a manos de los seguidores de Dioniso en mitos posteriores, sino como un epíteto del propio Dioniso, cuya mitología describe a un dios que debe soportar el sufrimiento antes de triunfar sobre él. Según Kerényi, el título de "hombre que sufre" probablemente se refería originalmente al propio dios, y solo se aplicó a personajes distintos a medida que se desarrollaba el mito. [33]

La imagen más antigua conocida de Dioniso, acompañada de su nombre, se encuentra en un dinos del alfarero ático Sophilos alrededor del 570 a. C. y se encuentra en el Museo Británico . [34] Para el siglo VII, la iconografía encontrada en cerámica muestra que Dioniso ya era adorado como algo más que un dios asociado con el vino. Estaba asociado con las bodas, la muerte, el sacrificio y la sexualidad, y su séquito de sátiros y bailarines ya estaba establecido. Un tema común en estas primeras representaciones era la metamorfosis, a manos del dios, de sus seguidores en criaturas híbridas, generalmente representadas por sátiros tanto domesticados como salvajes , que representan la transición de la vida civilizada a la naturaleza como medio de escape. [14]

Aunque las referencias académicas son escasas, existe una notable superposición entre el Dioniso grecorromano y el dios hindú Shiva. La iconografía y el trasfondo compartidos incluyen una medialuna o cuernos en la cabeza, pieles de pantera o tigre, serpientes, simbolismo fálico (Shiva lingam), asociación como vagabundo y paria y asociación con el éxtasis ritual. Se entiende que Shiva es uno de los tres dioses que incluye a Vishnu y Brahma. En varias referencias se menciona a Dioniso asociado con Oriente y la India. [ cita requerida ]

Se pensaba que una variante micénica de Baco era "un niño divino" abandonado por su madre y finalmente criado por " ninfas , diosas o incluso animales". [35]

Dioniso era conocido con los siguientes epítetos :

Acratóforo , Ἀκρατοφόρος ("dador de vino puro"), en Figaleia en Arcadia . [36]

Acroreitas en Sición . [37]

Adoneus , un arcaísmo raro en la literatura romana, una forma latinizada de Adonis , utilizado como epíteto de Baco. [38]

Aegobolus Αἰγοβόλος ("tirador de cabras") en Potniae , en Beocia . [39]

Aesymnetes Αἰσυμνήτης ("gobernante" o "señor") en Aroe y Patras en Acaya .

Agrios Ἄγριος ("salvaje"), en Macedonia .

Andrógino Ἀνδρόγυνος ( andrógino , específicamente en las relaciones sexuales) que se refiere al dios que asume tanto un papel masculino activo como un papel femenino pasivo. [40] [41]

Anthroporraistes , Ἀνθρωπορραίστης ("destructor de hombres"), título de Dioniso en Tenedos. [42]

Bassareus , Βασσαρεύς, nombre tracio para Dioniso, que deriva de bassaris o "piel de zorro", artículo que usaban sus cultistas en sus misterios. [43] [44]

Bougenes , Βουγενής o Βοηγενής ("llevado por una vaca"), en los Misterios de Lerna . [45] [46]

Braetes , Βραίτης ("relacionado con la cerveza") en Tracia . [47]

Briseo Βρῑσεύς ("el que prevalece") en Esmirna . [48] [49]

Bromios Βρόμιος ("rugido", como el del viento, relacionado principalmente con el elemento central del mito de muerte/resurrección, [50] pero también con las transformaciones del dios en león y toro, [51] y el bullicio de los que beben alcohol. También relacionado con el "rugido del trueno", que se refiere al padre de Dioniso, Zeus "el tronador". [52] )

Choiropsalas χοιροψάλας («desplumador de cerdos»: griego χοῖρος = «cerdo», también utilizado como término coloquial para referirse a los genitales femeninos). Una referencia al papel de Dioniso como deidad de la fertilidad. [53] [54]

Chthonios Χθόνιος ("el subterráneo") [55]

Cistophorus Κιστοφόρος ("portador de cestas, portador de hiedra"), alude a que las cestas son sagradas para el dios. [40] [56]

Dimetor Διμήτωρ ("nacido dos veces") Se refiere a los dos nacimientos de Dioniso. [40] [57] [58] [59]

Dendritas Δενδρίτης ("de los árboles"), como dios de la fertilidad. [60]

Ditirambo , Διθύραμβος utilizado en sus fiestas, en referencia a su nacimiento prematuro.

Eleutherios Ἐλευθέριος ("el liberador"), epíteto compartido con Eros .

Endendros ("él en el árbol"). [61]

Enorches ("con bolas"), [62] con referencia a su fertilidad, o "en los testículos" en referencia a que Zeus cosió al bebé Dioniso "en su muslo", entendido como sus testículos). [63] usado en Samos y Lesbos .

Eridromos ("buen funcionamiento"), en Dionysiaca de Nonnus. [64]

Erikryptos Ἐρίκρυπτος ("completamente oculto"), en Macedonia.

Euaster (Εὐαστήρ), del grito "euae". [65]

Euius ( Euios ), del grito "euae" en pasajes líricos y en la obra de Eurípides , Las Bacantes . [66]

Iacchus , Ἴακχος, un posible epíteto de Dioniso, asociado con los Misterios de Eleusis . En Eleusis , se le conoce como hijo de Zeus y Deméter . El nombre "Iacchus" puede provenir del Ιακχος ( Iakchos ), un himno cantado en honor a Dioniso.

Indoletes , Ἰνδολέτης , que significa asesino de indios. Debido a su campaña contra los indios. [67]

Isodetes , Ισοδαίτης , que significa "el que distribuye porciones iguales", epíteto de culto también compartido con Helios. [68]

Kemilius , Κεμήλιος ( kemas : "ciervo joven, ciervo"). [69] [70]

Liknites ("el del aventador"), como dios de la fertilidad relacionado con las religiones mistéricas . Se utilizaba un aventador para separar la paja del grano.

Lenaius , Ληναῖος ("dios del lagar") [71]

Lyaeus , o Lyaios (Λυαῖος, "libertador", literalmente "liberador"), aquel que libera del cuidado y la ansiedad. [72]

Lisio , Λύσιος («liberador, liberador»). En Tebas había un templo de Dioniso Lisio. [73] [74] [75]

Melanaigis Μελάναιγις ("de la piel de cabra negra") en el festival de Apaturia .

Morychus Μόρυχος ("untado"); en Sicilia, porque su icono fue untado con posos de vino en la vendimia. [76] [77]

Mystes Μύστης ("de los misterios") en Korythio en Arcadia . [78] [79]

Nysian Nύσιος , según Filóstrato , lo llamaban así los antiguos indios . [80] Muy probablemente, porque según la leyenda fundó la ciudad de Nysa . [81] [82] [83]

Eneo , Οἰνεύς («vino oscuro») como dios del lagar . [84] [85]

Omadios , Ωμάδιος ("comer carne cruda" [86] ); Eusebio escribe en Preparación para el Evangelio que Euelpis de Caristo afirma que en Quíos y Ténedos hicieron sacrificios humanos a Dionisio Omadios. [87] [88] [89]

Phallen , ( Φαλλήν ) (probablemente "relacionado con el falo "), en Lesbos . [90] [91]

Phleus ("relacionado con la flor de una planta"). [92] [93] [94]

Pseudanor Ψευδάνωρ (literalmente "hombre falso", en referencia a sus cualidades femeninas), en Macedonia .

Pericionio , Περικιόνιος ("trepando la columna (hiedra)", un nombre de Dioniso en Tebas. [95]

Semeleios [96] ( Semeleius o Semeleus ), [97] un epíteto oscuro que significa 'El de la Tierra', 'hijo de Sémele'. [98] [99] [100] [101] También aparece en la expresión Semeleios Iakchus plutodotas ("Hijo de Sémele, Iakchus, dador de riquezas"). [102]

Skyllitas , Σκυλλίτας ("relacionado con la rama de la vid") en Kos. [103] [104]

Sykites , Συκίτης ("relacionado con los higos"), en Laconia. [105]

Taurophagus , Ταυροφάγος ("comedor de toros"). [106]

Tauros Ταῦρος ("un toro"), aparece como un apellido de Dionisio. [107] [108]

Teino , Θέοινος (dios del vino de un festival en el Ática). [109] [110] [111]

Τhyiοn , Θυίων ("del festival de Dionisio 'Thyia' (Θυῐα) en Elis"). [112] [113]

Thyllophorus , Θυλλοφόρος ("que lleva hojas"), en Kos. [114] [115]

En el panteón griego , Dioniso (junto con Zeus ) asume el papel de Sabacio , una deidad tracia / frigia . En el panteón romano , Sabacio se convirtió en un nombre alternativo para Baco. [116]

El culto a Dioniso se había establecido firmemente en el siglo VII a. C. [117] Es posible que los griegos micénicos lo adoraran ya en torno al 1500-1100 a. C. [ 118] [22] y también se han encontrado rastros de culto de tipo dionisíaco en la antigua Creta minoica . [33]

Las fiestas de las Dionisías , Haloa , Ascolia y Lenaia estaban dedicadas a Dioniso. [119] Las Dionisías Rurales (o Dionisías Menores) eran una de las fiestas más antiguas dedicadas a Dioniso, que comenzó en el Ática y probablemente celebraba el cultivo de la vid. Se celebraba durante el mes de invierno de Poseideón (el período que rodea el solsticio de invierno, el actual diciembre o enero). Las Dionisías Rurales se centraban en una procesión, durante la cual los participantes llevaban falos, panes largos, jarras de agua y vino, así como otras ofrendas, y las jóvenes llevaban cestas. La procesión era seguida por una serie de representaciones dramáticas y concursos de teatro. [120]

Las Dionisías urbanas (o Dionisías mayores) se celebraban en centros urbanos como Atenas y Eleusis , y fueron un acontecimiento posterior, que probablemente comenzó durante el siglo VI a. C. Celebradas tres meses después de las Dionisías rurales, las grandes fiestas se celebraban cerca del equinoccio de primavera en el mes de Elaphebolion (actual marzo o abril). La procesión de las Dionisías urbanas era similar a la de las celebraciones rurales, pero más elaborada, y encabezada por participantes que portaban una estatua de madera de Dioniso, e incluía toros sacrificiales y coros ornamentados. Las competiciones dramáticas de las Dionisías mayores también incluían a poetas y dramaturgos más destacados, y premios tanto para dramaturgos como para actores en múltiples categorías. [120] [15]

La Antesteria (Ἀνθεστήρια) era un festival ateniense que celebraba el comienzo de la primavera. Se extendía durante tres días: Pithoigia (Πιθοίγια, "Apertura de las jarras"), Choes (Χοαί, "El vertido") y Chythroi (Χύτροι "Las ollas"). [121] Se decía que los muertos se levantaban del inframundo durante el transcurso del festival. Junto con las almas de los muertos, las Keres también vagaban por la ciudad y tenían que ser desterradas cuando terminaba el festival. [122] El primer día se abrían los cubas de vino. [123] El vino se abría y se mezclaba en honor al dios. [124] Las habitaciones y los vasos para beber se adornaban con flores junto con niños mayores de tres años. [121]

El segundo día se celebraba un solemne ritual en honor a Dioniso, acompañado de una copa. La gente se disfrazaba, a veces como miembros del séquito de Dioniso, y visitaba a otros. Choes también era la ocasión de una ceremonia solemne y secreta en uno de los santuarios de Dioniso en el Lenaeum, que permanecía cerrado el resto del año. La basilisa (o basilinna), esposa del basileo, se casaba simbólicamente con el dios, posiblemente representando a un Hieros gamos . La basilisa era asistida por catorce matronas atenienses (llamadas Gerarai ) que eran elegidas por el basileo y juraban guardar el secreto. [121] [125]

El último día estaba dedicado a los muertos. También se hacían ofrendas a Hermes , debido a su conexión con el inframundo. Se consideraba un día de fiesta. [121] Algunos vertían libaciones sobre las tumbas de los parientes fallecidos. Los Chythroi terminaban con un grito ritual destinado a ordenar a las almas de los muertos que regresaran al inframundo. [125] Las keres también eran expulsadas del festival el último día. [122]

Para protegerse del mal, la gente masticaba hojas de espino blanco y untaba sus puertas con brea para protegerse. La fiesta también permitía que sirvientes y esclavos participaran en las festividades. [121] [122]

El culto religioso central de Dioniso se conoce como los misterios báquicos o dionisíacos . Se desconoce el origen exacto de esta religión, aunque se dice que Orfeo inventó los misterios de Dioniso. [126] La evidencia sugiere que muchas fuentes y rituales que normalmente se consideran parte de los misterios órficos similares en realidad pertenecen a los misterios dionisíacos. [14] Algunos estudiosos han sugerido que, además, no hay diferencia entre los misterios dionisíacos y los misterios de Perséfone , sino que todos eran facetas de la misma religión mistérica, y que Dioniso y Perséfone tenían papeles importantes en ella. [14] [127] Anteriormente se consideraba que era una parte principalmente rural y marginal de la religión griega, el principal centro urbano de Atenas jugó un papel importante en el desarrollo y la difusión de los misterios báquicos. [14]

Los misterios báquicos desempeñaron un papel importante en la creación de tradiciones rituales para las transiciones en la vida de las personas; originalmente, principalmente para los hombres y la sexualidad masculina, pero más tarde también crearon un espacio para ritualizar los roles cambiantes de las mujeres y celebrar los cambios de estatus en la vida de una mujer. Esto a menudo se simbolizaba mediante un encuentro con los dioses que gobiernan la muerte y el cambio, como Hades y Perséfone, pero también con Sémele, la madre de Dioniso, que probablemente cumplió un papel relacionado con la iniciación en los misterios. [14]

La religión de Dioniso incluía a menudo rituales que implicaban el sacrificio de cabras o toros, y al menos algunos participantes y bailarines llevaban máscaras de madera asociadas con el dios. En algunos casos, los registros muestran al dios participando en el ritual a través de una columna, un poste o un árbol enmascarado y vestido, mientras sus adoradores comen pan y beben vino. La importancia de las máscaras y las cabras para el culto a Dioniso parece remontarse a los primeros días de su culto, y estos símbolos se han encontrado juntos en una tumba minoica cerca de Festos en Creta. [33]

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/440px-Hans_von_Aachen_-_Bacchus,_Ceres_and_Amor_(%3F)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Ya en el siglo V a. C., Dioniso fue identificado con Iacchus , una deidad menor de la tradición de los Misterios de Eleusis . [128] Esta asociación puede haber surgido debido a la homofonía de los nombres Iacchus y Bacchus. Dos lekythoi de figuras negras (c. 500 a. C.), posiblemente representan la evidencia más temprana de tal asociación. Los jarrones casi idénticos, uno en Berlín, [129] el otro en Roma, [130] representan a Dioniso, junto con la inscripción IAKXNE , una posible mala escritura de IAKXE . [131] Se pueden encontrar más evidencias tempranas en las obras de los trágicos atenienses del siglo V a. C. Sófocles y Eurípides . [132] En la Antígona de Sófocles (c. 441 a. C.), una oda a Dioniso comienza dirigiéndose a Dioniso como el "Dios de muchos nombres" ( πολυώνυμε ), que gobierna sobre los valles de Eleusis de Deméter, y termina identificándolo con "Yaco el Dador", que lidera "el coro de las estrellas cuyo aliento es fuego" y cuyas "tíiadas asistentes" bailan en "frenesí nocturno". [133] Y en un fragmento de una obra perdida, Sófocles describe a Nisa , el lugar tradicional de crianza de Dioniso: "Desde aquí alcancé a ver a Nisa, guarida de Baco, famosa entre los mortales, a la que Yaco, el de los cuernos de toro, cuenta como su amada nodriza". [134] En Bacantes de Eurípides (c. 405 a. C.), un mensajero, al describir las orgías báquicas en el monte Citerón , asocia a Iacchus con Bromius , otro de los nombres de Dionisio, diciendo que "comenzaron a agitar los tirsos... llamando a Iacchus, el hijo de Zeus, Bromius, con voz unida". [135]

Una inscripción encontrada en una estela de piedra (c. 340 a. C.), hallada en Delfos , contiene un panegírico a Dioniso, que describe sus viajes. [136] Desde Tebas , donde nació, fue primero a Delfos donde exhibió su "cuerpo estrellado", y con "muchachas de Delfos" tomó su "lugar en los pliegues del Parnaso", [137] luego junto a Eleusis , donde se le llama "Iacchus":

Estrabón , dice que los griegos «dan el nombre de 'Iacchus' no sólo a Dioniso sino también al líder en jefe de los misterios». [139] En particular, Iacchus fue identificado con el Dioniso órfico , que era hijo de Perséfone. [140] Sófocles menciona a «Iacchus de los cuernos de toro», y según el historiador del siglo I a. C. Diodoro Sículo , fue este Dioniso mayor quien fue representado en pinturas y esculturas con cuernos, porque «sobresalió en sagacidad y fue el primero en intentar uncir bueyes y con su ayuda efectuar la siembra de la semilla». [141] Arriano , el historiador griego del siglo II, escribió que fue a este Dioniso, el hijo de Zeus y Perséfone, «no al Dioniso tebano, a quien se canta el canto místico 'Iacchus'». [142] El poeta del siglo II Luciano también se refirió al «desmembramiento de Yaco». [143]

El poeta del siglo IV o V Nono asoció el nombre de Yaco con el "tercer" Dioniso. Describió las celebraciones atenienses que se dieron al primer Dioniso Zagreo , hijo de Perséfone , al segundo Dioniso Bromio , hijo de Sémele , y al tercer Dioniso Yaco:

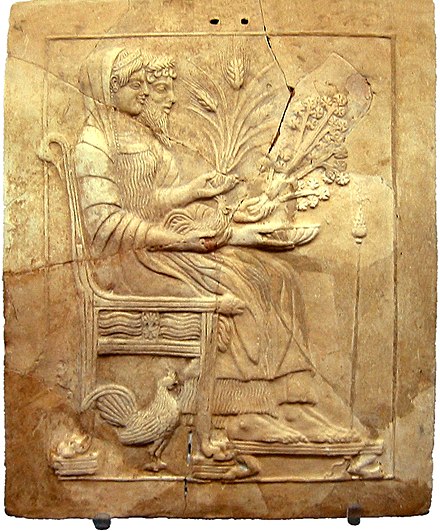

Según algunos relatos, Yaco era el esposo de Deméter. [145] Varias otras fuentes identifican a Yaco como el hijo de Deméter. [146] La fuente más antigua de este tipo, un fragmento de un vaso del siglo IV a. C. en Oxford, muestra a Deméter sosteniendo al niño Dioniso en su regazo. [147] Para el siglo I a. C., Deméter amamantando a Yaco se había convertido en un motivo tan común, que el poeta latino Lucrecio pudo usarlo como un ejemplo aparentemente reconocible del eufemismo de un amante. [148] Un escoliasta sobre Arístides , del siglo II d. C. , nombra explícitamente a Deméter como la madre de Yaco. [149]

En la tradición órfica , el «primer Dioniso» era hijo de Zeus y Perséfone , y fue desmembrado por los Titanes antes de renacer. [150] Dioniso era el dios patrón de los órficos, a quien conectaban con la muerte y la inmortalidad, y simbolizaba al que guía el proceso de reencarnación . [151]

A este Dioniso órfico se lo menciona a veces con el nombre alternativo Zagreo ( griego : Ζαγρεύς ). Las primeras menciones de este nombre en la literatura lo describen como un compañero de Gea y lo llaman el dios supremo. Esquilo relacionó a Zagreo con Hades, ya sea como hijo de Hades o como Hades mismo. [152] Al señalar la "identidad de Hades como el alter ego katachthonios de Zeus", Timothy Gantz pensó que era probable que Zagreo, originalmente, tal vez, el hijo de Hades y Perséfone, se fusionara más tarde con el Dioniso órfico, el hijo de Zeus y Perséfone. [153] Sin embargo, ninguna fuente órfica conocida usa el nombre "Zagreo" para referirse al Dioniso órfico. Es posible que la asociación entre los dos fuera conocida en el siglo III a. C., cuando el poeta Calímaco pudo haber escrito sobre ella en una fuente ahora perdida. [154] Calímaco, así como su contemporáneo Euforión , contaron la historia del desmembramiento del infante Dioniso, [155] y fuentes bizantinas citan a Calímaco refiriéndose al nacimiento de un "Dioniso Zagreo", explicando que Zagreo era el nombre de los poetas para el aspecto ctónico de Dioniso. [156] La primera referencia definitiva a la creencia de que Zagreo es otro nombre para el Dioniso órfico se encuentra en los escritos de finales del siglo I de Plutarco . [157] El poeta griego del siglo V Nono , Dionysiaca, cuenta la historia de este Dioniso órfico, en la que Nono lo llama el "Dioniso mayor... Zagreo malogrado", [158] "Zagreo el bebé con cuernos", [159] "Zagreo, el primer Dioniso", [160] "Zagreo el antiguo Dioniso", [161] y "Dioniso Zagreo". [162]

Baco era más conocido por ese nombre en Roma y otros lugares de la República y el Imperio, aunque muchos "a menudo lo llamaban Dioniso". [163]

_-_Napoli_MAN_9449_-_01.jpg/440px-Wall_painting_-_Dionysos_with_Helios_and_Aphrodite_-_Pompeii_(VII_2_16)_-_Napoli_MAN_9449_-_01.jpg)

El culto mistérico a Baco llegó a Roma desde la cultura griega del sur de Italia o a través de la Etruria de influencia griega . Fue establecido alrededor del año 200 a. C. en el bosque aventino de Stimula por una sacerdotisa de Campania , cerca del templo donde Liber Pater ("el Padre Libre") tenía un culto popular sancionado por el Estado. Liber era un dios romano nativo del vino, la fertilidad y la profecía, patrón de los plebeyos de Roma (ciudadanos comunes) y uno de los miembros de la Tríada del Aventino , junto con su madre Ceres y su hermana o consorte Libera. Se erigió un templo a la Tríada en el monte Aventino en el año 493 a. C., junto con la institución de la celebración del festival de Liberalia . El culto a la Tríada gradualmente adquirió cada vez más influencia griega, y hacia el año 205 a. C., Liber y Libera habían sido identificados formalmente con Baco y Proserpina . [164] A menudo se identificaba a Liber de forma intercambiable con Dioniso y su mitología, aunque esta identificación no era aceptada universalmente. [165] Cicerón insistió en la "no identidad de Liber y Dioniso" y describió a Liber y Libera como hijos de Ceres. [166]

Liber, al igual que sus compañeros del Aventino, trasladó varios aspectos de sus antiguos cultos a la religión romana oficial. Protegió varios aspectos de la agricultura y la fertilidad, incluida la vid y la "semilla blanda" de sus uvas, el vino y los recipientes para el vino, y la fertilidad masculina y la virilidad. [166] Plinio llamó a Liber "el primero en establecer la práctica de comprar y vender; también inventó la diadema, el emblema de la realeza, y la procesión triunfal". [167] Los mosaicos y sarcófagos romanos dan testimonio de varias representaciones de una exótica procesión triunfal similar a la de Dioniso. En fuentes literarias romanas y griegas de finales de la República y la era imperial, varios triunfos notables presentan elementos procesionales similares, distintivamente "baquicos", que recuerdan al supuestamente histórico "Triunfo de Liber". [168]

Es posible que Liber y Dioniso tuvieran una conexión que precedió a la Grecia y Roma clásicas, en la forma del dios micénico Eleutero, que compartía el linaje y la iconografía de Dioniso pero cuyo nombre tiene el mismo significado que Liber. [33] Antes de la importación de los cultos griegos, Liber ya estaba fuertemente asociado con los símbolos y valores báquicos, incluidos el vino y la libertad desinhibida, así como la subversión de los poderosos. Varias representaciones de la era de la República tardía presentan procesiones, que representan el "Triunfo de Liber". [168]

.jpg/440px-Sacrificio_a_Baco_(Massimo_Stanzione).jpg)

En Roma, las fiestas más conocidas de Baco eran las Bacanales , basadas en las anteriores fiestas griegas de las Dionisías. Se decía que estos rituales báquicos incluían prácticas homófagas , como descuartizar animales vivos y comérselos crudos. Esta práctica no sólo servía como una recreación de la muerte infantil y el renacimiento de Baco, sino también como un medio por el cual los practicantes báquicos producían "entusiasmo": etimológicamente, dejar que un dios entrara en el cuerpo del practicante o hacer que se volviera uno con Baco. [169] [170]

En el relato de Livio , los misterios báquicos eran una novedad en Roma; originalmente restringidos a las mujeres y celebrados sólo tres veces al año, fueron corrompidos por una versión etrusco-griega, y a partir de entonces, hombres y mujeres borrachos y desinhibidos de todas las edades y clases sociales retozaban en un caos sexual cinco veces al mes. Livio relata sus diversos atropellos contra las leyes civiles y religiosas de Roma y la moralidad tradicional ( mos maiorum ); una contracultura secreta, subversiva y potencialmente revolucionaria. Las fuentes de Livio, y su propio relato del culto, probablemente se basaron en gran medida en el género dramático romano conocido como "obras satíricas", basadas en originales griegos. [171] [172] El culto fue suprimido por el Estado con gran ferocidad; de los 7.000 arrestados, la mayoría fueron ejecutados. La erudición moderna trata gran parte del relato de Livio con escepticismo; Más ciertamente, un edicto senatorial, el Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus , se distribuyó por toda la Italia romana y sus aliadas. Prohibía las antiguas organizaciones de culto báquico. Cada reunión debía solicitar la aprobación senatorial previa a través de un pretor . No se permitía la presencia de más de tres mujeres y dos hombres en cada reunión, y quienes desafiaran el edicto se arriesgaban a la pena de muerte.

Baco fue incluido en el panteón romano oficial como un aspecto de Liber, y su festival fue insertado en la Liberalia . En la cultura romana, Liber, Baco y Dioniso se convirtieron en equivalentes prácticamente intercambiables. Gracias a su mitología que involucra viajes y luchas en la tierra, Baco se convirtió en un héroe histórico, conquistador y fundador de ciudades. Fue una deidad patrona y héroe fundador en Leptis Magna , lugar de nacimiento del emperador Septimio Severo , quien promovió su culto. En algunas fuentes romanas, la procesión ritual de Baco en un carro tirado por tigres, rodeado de ménades, sátiros y borrachos, conmemora el regreso triunfal del dios de la conquista de la India. Plinio creía que este era el prototipo histórico del Triunfo romano . [173]

En la filosofía y religión neoplatónica de la Antigüedad tardía , a veces se consideraba que los dioses olímpicos eran doce, en función de sus esferas de influencia. Por ejemplo, según Salustio , «Júpiter, Neptuno y Vulcano fabrican el mundo; Ceres, Juno y Diana lo animan; Mercurio, Venus y Apolo lo armonizan; y, por último, Vesta, Minerva y Marte lo presiden con un poder protector». [174] La multitud de otros dioses, en este sistema de creencias, subsiste dentro de los dioses primarios, y Salustio enseñó que Baco subsistía en Júpiter. [174]

En la tradición órfica , supuestamente un oráculo de Apolo decía que « Zeus , Hades y Helios -Dionisio» eran «tres dioses en una divinidad». Esta afirmación aparentemente confundía a Dioniso no solo con Hades, sino también con su padre Zeus, e implicaba una identificación particularmente estrecha con el dios del sol Helios. Al citar esto en su Himno al rey Helios , el emperador Juliano sustituyó el nombre de Dioniso por el de Serapis , cuyo homólogo egipcio, Osiris, también se identificaba con Dioniso.

Tres siglos después del reinado de Teodosio I , que vio la ilegalización del culto pagano en todo el Imperio Romano, el Concilio Quinisexto de 692 en Constantinopla sintió que era necesario advertir a los cristianos contra la participación en el persistente culto rural de Dioniso, mencionando y prohibiendo específicamente la fiesta de Brumalia , "las danzas públicas de mujeres", el travestismo ritual, el uso de máscaras dionisíacas y la invocación del nombre de Baco al "exprim[ir] el vino en los lagares" o "al verter el vino en jarras". [175]

Según la crónica de Lanercost , durante la Pascua de 1282 en Escocia , el párroco de Inverkeithing dirigió a las mujeres jóvenes en una danza en honor a Príapo y al padre Liber , comúnmente identificado con Dioniso. El sacerdote bailó y cantó al frente, llevando una representación del falo en un poste. Fue asesinado por una turba cristiana más tarde ese año. [176] El historiador CS Watkins cree que Ricardo de Durham, el autor de la crónica, identificó un suceso de magia apotropaica (haciendo uso de su conocimiento de la religión griega antigua ), en lugar de registrar un caso real de supervivencia de un ritual pagano. [177]

El erudito bizantino medieval tardío Gemistus Pletho abogó en secreto por un retorno al paganismo en la Grecia medieval. [ cita requerida ]

En el siglo XVIII, aparecieron los Clubes del Fuego Infernal en Gran Bretaña e Irlanda . Aunque las actividades variaban entre los clubes, algunos de ellos eran muy paganos e incluían santuarios y sacrificios. Dioniso era una de las deidades más populares, junto con deidades como Venus y Flora . Hoy en día todavía se puede ver la estatua de Dioniso que quedó en las Cuevas del Fuego Infernal . [178]

En 1820, Ephraim Lyon fundó la Iglesia de Baco en Eastford , Connecticut . Se declaró Sumo Sacerdote y añadió a los borrachos locales a la lista de miembros. Sostuvo que aquellos que murieran como miembros irían a una Bacanal para su vida después de la muerte. [179]

Los grupos paganos y politeístas modernos a menudo incluyen la adoración de Dioniso en sus tradiciones y prácticas, más prominentemente los grupos que han tratado de revivir el politeísmo helénico , como el Consejo Supremo de Helenos Étnicos (YSEE). [180] Además de las libaciones de vino, los adoradores modernos de Dioniso ofrecen al dios vides, hiedra y varias formas de incienso, particularmente styrax . [181] También pueden celebrar festivales romanos como Liberalia (17 de marzo, cerca del equinoccio de primavera ) o Bacchanalia (varias fechas), y varios festivales griegos como Anthesteria , Lenaia y las Dionisias Mayor y Menor , cuyas fechas se calculan por el calendario lunar . [182]

En la interpretación griega del panteón egipcio , Dioniso era identificado a menudo con Osiris . [183] Las historias del desmembramiento de Osiris y su reensamblaje y resurrección por Isis son muy paralelas a las del Dioniso y Deméter órficos. [184] Según Diodoro Sículo, [185] ya en el siglo V a. C., los dos dioses habían sido sincretizados como una única deidad conocida como Dioniso-Osiris . El registro más notable de esta creencia se encuentra en las " Historias " de Heródoto . [186] Plutarco era de la misma opinión, registrando su creencia de que Osiris y Dioniso eran idénticos y afirmando que cualquiera que estuviera familiarizado con los rituales secretos asociados con los dos dioses reconocería paralelismos obvios entre ellos, señalando que los mitos de su desmembramiento y sus símbolos públicos asociados constituían evidencia adicional suficiente para demostrar que eran, de hecho, el mismo dios adorado por las dos culturas bajo diferentes nombres. [187]

Otras deidades sincréticas grecoegipcias surgieron de esta fusión, incluyendo a los dioses Serapis y Hermanubis . Se creía que Serapis era Hades y Osiris, y el emperador romano Juliano lo consideraba igual a Dioniso. Dioniso-Osiris era particularmente popular en el Egipto ptolemaico, ya que los ptolomeos afirmaban descender de Dioniso, y como faraones tenían derecho al linaje de Osiris. [188] Esta asociación fue más notable durante una ceremonia de deificación donde Marco Antonio se convirtió en Dioniso-Osiris, junto con Cleopatra como Isis-Afrodita. [189]

Los mitos egipcios sobre Príapo decían que los Titanes conspiraron contra Osiris, lo mataron, dividieron su cuerpo en partes iguales y "las sacaron a escondidas de la casa". Todos menos el pene de Osiris, que como ninguno de ellos "estaba dispuesto a llevárselo", lo arrojaron al río. Isis, la esposa de Osiris, persiguió y mató a los Titanes, volvió a ensamblar las partes del cuerpo de Osiris "en forma de una figura humana" y se las dio "a los sacerdotes con órdenes de que rindieran a Osiris los honores de un dios". Pero como no pudo recuperar el pene, ordenó a los sacerdotes "que le rindieran los honores de un dios y lo colocaran en sus templos en posición erecta". [190]

El filósofo del siglo V-IV a. C. Heráclito , unificando los opuestos, declaró que Hades y Dioniso, la esencia misma de la vida indestructible ( zoë ) , son el mismo dios. [191] Entre otras pruebas, Karl Kerényi señala en su libro [192] que el Himno homérico "A Deméter", [193] imágenes votivas de mármol [194] y epítetos [195] vinculan a Hades con Dioniso. También señala que la afligida diosa Deméter se negó a beber vino, ya que afirma que sería contra themis [ jerga ] que bebiera vino, que es el regalo de Dioniso, después del rapto de Perséfone debido a esta asociación; lo que indica que Hades puede, de hecho, haber sido un "nombre encubierto" para el Dioniso del inframundo. [196] Sugiere que esta identidad dual puede haber sido familiar para aquellos que entraron en contacto con los Misterios . [197] Uno de los epítetos de Dioniso era "Chthonios", que significa "el subterráneo". [198]

La evidencia de una conexión de culto es bastante extensa, particularmente en el sur de Italia, especialmente cuando se considera la fuerte participación del simbolismo de la muerte incluido en el culto dionisíaco. [199] Las estatuas de Dioniso [200] [201] encontradas en el Ploutonion en Eleusis brindan más evidencia ya que las estatuas encontradas tienen un parecido sorprendente con la estatua de Eubouleus, también llamado Aides Kyanochaites (Hades del cabello oscuro suelto), [202] [203] [204] conocida como la representación juvenil del Señor del Inframundo. La estatua de Eubouleus se describe como radiante pero que revela una extraña oscuridad interior. [205] [203] Las representaciones antiguas muestran a Dioniso sosteniendo en su mano el kantharos, una jarra de vino con asas grandes, y ocupando el lugar donde uno esperaría ver a Hades. El artista arcaico Jenocles retrató en un lado de un jarrón a Zeus, Poseidón y Hades, cada uno con sus emblemas de poder; con la cabeza de Hades vuelta hacia adelante y, en el otro lado, Dioniso avanzando para encontrarse con su novia Perséfone, con el cántaro en su mano, sobre un fondo de uvas. [206] Dioniso también compartía varios epítetos con Hades como Ctonio , Eubuleo y Euclio .

Tanto Hades como Dioniso estaban asociados a una deidad divina tripartita con Zeus . [207] [208] A veces se creía que Zeus, como Dioniso, tenía una forma del inframundo, estrechamente identificada con Hades, hasta el punto de que a veces se pensaba que eran el mismo dios. [208]

Según Marguerite Rigoglioso, Hades es Dioniso, y la tradición eleusina creía que este dios dual había impregnado a Perséfone. Esto pondría a la tradición eleusina en armonía con el mito en el que Zeus, no Hades, impregnó a Perséfone para dar a luz al primer Dioniso. Rigoglioso sostiene que tomados en conjunto, estos mitos sugieren una creencia según la cual, con Perséfone, Zeus/Hades/Dioniso crearon (en términos citados de Kerényi) "un segundo, un pequeño Dioniso", que también es un "Zeus subterráneo". [208] La unificación de Hades, Zeus y Dioniso como un solo dios tripartito se utilizó para representar el nacimiento, la muerte y la resurrección de una deidad y para unificar el reino "brillante" de Zeus y el reino oscuro del inframundo de Hades. [207] Según Rosemarie Taylor-Perry, [207] [208]

A menudo se menciona que a Zeus, Hades y Dioniso se les atribuía ser exactamente el mismo dios... Al ser una deidad tripartita, Hades también es Zeus, y se duplica como el Dios del Cielo o Zeus. Hades rapta a su "hija" y amante Perséfone. La toma de Kore por Hades es el acto que permite la concepción y el nacimiento de una segunda fuerza integradora: Iacchos (Zagreus-Dioniso), también conocido como Liknites, la forma infantil indefensa de esa Deidad que es el unificador del reino del inframundo oscuro (ctónico) de Hades y el olímpico ("brillante") de Zeus.

El dios frigio Sabazio era identificado alternativamente con Zeus o con Dioniso. La enciclopedia griega bizantina Suda (c. siglo X) afirmaba: [211]

Sabazios... es lo mismo que Dionisos. Adquirió esta forma de tratamiento del rito que le pertenecía; pues los bárbaros llaman al grito báquico "sabazein". Por eso algunos de los griegos también siguen su ejemplo y llaman al grito "sabasmos"; de este modo Dionisos [se convierte en] Sabazios. También solían llamar "saboi" a los lugares que habían sido dedicados a él y a sus Bacantes ... Demóstenes [en el discurso] "En nombre de Ctesifón" [los menciona]. Algunos dicen que Saboi es el término para aquellos que están dedicados a Sabazios, es decir, a Dionisos, así como aquellos [dedicados] a Bakkhos [son] Bakkhoi. Dicen que Sabazios y Dionisos son lo mismo. Por eso algunos también dicen que los griegos llaman a los Bakkhoi Saboi.

Estrabón , en el siglo I, relacionó a Sabazio con Zagreo entre los ministros frigios y asistentes de los ritos sagrados de Rea y Dioniso. [212] El contemporáneo siciliano de Estrabón, Diodoro Sículo , confundió a Sabazio con el secreto Dioniso, nacido de Zeus y Perséfone, [213] Sin embargo, esta conexión no está respaldada por ninguna inscripción sobreviviente, que son enteramente para Zeus Sabazio . [214]

Varias fuentes antiguas registran una creencia aparentemente extendida en el mundo clásico de que el dios adorado por el pueblo judío , Yahvé , era identificable como Dioniso o Liber a través de su identificación con Sabacio. Tácito, Lido, Cornelio Labeo y Plutarco hicieron esta asociación, o la discutieron como una creencia existente (aunque algunos, como Tácito, la mencionaron específicamente para rechazarla). Según Plutarco, una de las razones de la identificación es que se decía que los judíos saludaban a su dios con las palabras "Euoe" y "Sabi", un grito típicamente asociado con la adoración de Sabacio. Según el erudito Sean M. McDonough , es posible que las fuentes de Plutarco hubieran confundido el grito de "Iao Sabaoth" (típicamente usado por los hablantes griegos en referencia a Yahvé) con el grito sabaziano de "Euoe Saboe", originando la confusión y combinación de las dos deidades. El grito de "Sabi" también podría haberse mezclado con el término judío "shabbat", lo que se suma a la evidencia que los antiguos vieron de que Yahvé y Dionisio/Sabacio eran la misma deidad. Para reforzar aún más esta conexión, habrían sido las monedas utilizadas por los Macabeos que incluían imágenes vinculadas al culto a Dionisio, como uvas, hojas de parra y copas. Sin embargo, la creencia de que el dios judío era idéntico a Dionisio/Sabacio estaba lo suficientemente extendida como para que una moneda del 55 a. C. que representaba a un rey arrodillado fuera etiquetada como "Baco del Judaísmo" ( BACCHIVS IVDAEVS ), y en el 139 a. C. el pretor Cornelio Escipión Hispalo deportara a los judíos por intentar "infectar las costumbres romanas con el culto a Júpiter Sabazio". [215]

En el mundo antiguo existían diversos relatos y tradiciones sobre la ascendencia, el nacimiento y la vida de Dioniso en la Tierra, complicadas por sus varios renacimientos. Hacia el siglo I a. C., algunos mitógrafos habían intentado armonizar los diversos relatos del nacimiento de Dioniso en una única narración que incluía no solo múltiples nacimientos, sino dos o tres manifestaciones distintas del dios en la Tierra a lo largo de la historia en diferentes vidas. El historiador Diodoro Sículo dijo que según "algunos escritores de mitos" había dos dioses llamados Dioniso, uno mayor, que era hijo de Zeus y Perséfone, [217] pero que "el más joven también heredó las hazañas del mayor, y así los hombres de tiempos posteriores, al no ser conscientes de la verdad y engañados por la identidad de sus nombres, pensaron que había habido un solo Dioniso". [218] También dijo que se pensaba que Dionisio "tenía dos formas... la antigua tenía una barba larga, porque todos los hombres en los primeros tiempos usaban barbas largas, y el más joven tenía el pelo largo, era juvenil, afeminado y joven". [219] [220]

Aunque la variada genealogía de Dioniso se menciona en muchas obras de la literatura clásica, solo unas pocas contienen los mitos narrativos reales que rodean los eventos de sus múltiples nacimientos. Estos incluyen la Bibliotheca historica del siglo I a. C. del historiador griego Diodoro , que describe el nacimiento y los hechos de las tres encarnaciones de Dioniso; [221] la breve narración del nacimiento dada por el autor romano del siglo I d. C. Higinio , que describe un doble nacimiento para Dioniso; y un relato más largo en forma de la epopeya del poeta griego Nono Dionysiaca , que analiza tres encarnaciones de Dioniso similares al relato de Diodoro, pero que se centra en la vida del tercer Dioniso, nacido de Zeus y Sémele.

Aunque Diodoro menciona algunas tradiciones que afirman que existió un Dioniso indio o egipcio más antiguo que inventó el vino, no se dan narraciones de su nacimiento o vida entre los mortales, y la mayoría de las tradiciones atribuyen la invención del vino y los viajes a través de la India al último Dioniso. Según Diodoro, Dioniso era originalmente hijo de Zeus y Perséfone (o alternativamente, Zeus y Deméter ). Este es el mismo Dioniso con cuernos descrito por Higinio y Nono en relatos posteriores, y el Dioniso adorado por los órficos, que fue desmembrado por los Titanes y luego renació. Nono llama a este Dioniso Zagreo , mientras que Diodoro dice que también se lo considera idéntico a Sabacio . [222] Sin embargo, a diferencia de Higinio y Nono, Diodoro no proporciona una narrativa de nacimiento para esta encarnación del dios. Fue este Dioniso quien se dice que enseñó a los mortales cómo usar bueyes para arar los campos, en lugar de hacerlo a mano. Se dice que sus adoradores lo honraron por esto representándolo con cuernos. [222]

El poeta griego Nonnus narra el nacimiento de Dioniso en su epopeya de finales del siglo IV o principios del V d. C., Dionysiaca . En ella, describe cómo Zeus "intentó hacer crecer un nuevo Dioniso, una copia con forma de toro del Dioniso anterior", que era el dios egipcio Osiris (Dionysiaca 4). [224] Zeus tomó la forma de una serpiente (" drakon ") y "violó la virginidad de la soltera Perséfonea". Según Nonnus, aunque Perséfone era "la consorte del rey del inframundo vestido de negro", permaneció virgen y su madre la había escondido en una cueva para evitar a los muchos dioses que eran sus pretendientes, porque "todos los que habitaban en el Olimpo estaban hechizados por esta muchacha, rivales en el amor por la doncella casadera". (Dionysiaca 5) [225] Después de su unión con Zeus, el vientre de Perséfone "se hinchó de fruto vivo", y dio a luz a un bebé con cuernos, llamado Zagreo. Zagreo, a pesar de su infancia, pudo subir al trono de Zeus y blandir sus rayos, marcándolo como heredero de Zeus. Hera vio esto y alertó a los Titanes, quienes se untaron las caras con tiza y tendieron una emboscada al infante Zagreo "mientras contemplaba su rostro cambiante reflejado en un espejo". Lo atacaron. Sin embargo, según Nonnus, "donde sus miembros habían sido cortados a trozos por el acero del Titán, el final de su vida fue el comienzo de una nueva vida como Dioniso". Comenzó a cambiar a muchas formas diferentes en las que devolvió el ataque, incluido Zeus, Cronos , un bebé y "un joven loco con la flor del primer plumón marcando su barbilla redondeada con negro". Zeus se transformó en varios animales para atacar a los Titanes reunidos, entre ellos un león, un caballo salvaje, una serpiente cornuda, un tigre y, finalmente, un toro. Hera intervino, matando al toro con un grito, y los Titanes finalmente lo masacraron y lo cortaron en pedazos. Zeus atacó a los Titanes y los hizo encarcelar en el Tártaro . Esto hizo que la madre de los Titanes, Gea , sufriera, y sus síntomas se vieron en todo el mundo, lo que resultó en incendios e inundaciones, y mares hirvientes. Zeus se apiadó de ella y, para enfriar la tierra ardiente, provocó grandes lluvias que inundaron el mundo . (Dionisíacas 6) [226]

En la tradición órfica, Dioniso era, en parte, un dios asociado con el inframundo. Como resultado, los órficos lo consideraban hijo de Perséfone, y creían que había sido desmembrado por los Titanes y luego había renacido. La primera evidencia de este mito del desmembramiento y renacimiento de Dioniso proviene del siglo I a. C., en las obras de Filodemo y Diodoro Sículo . [227] Más tarde, neoplatónicos como Damascio y Olimpiodoro añadieron una serie de elementos adicionales al mito, incluido el castigo de los Titanes por su acto, su destrucción por un rayo de su mano y el posterior nacimiento de la humanidad de sus cenizas; sin embargo, si alguno de estos elementos era parte del mito original es tema de debate entre los académicos. [228] El desmembramiento de Dioniso (el sparagmos ) a menudo se ha considerado el mito más importante del orfismo. [229]

Muchas fuentes modernas identifican a este «Dionisio órfico» con el dios Zagreo , aunque este nombre no parece haber sido utilizado por ninguno de los antiguos órficos, que simplemente lo llamaban Dioniso. [230] Según se ha reconstruido a partir de varias fuentes antiguas, la historia, generalmente dada por los eruditos modernos, es la siguiente: [231] Zeus tuvo relaciones sexuales con Perséfone en forma de serpiente, produciendo a Dioniso. El niño fue llevado al monte Ida , donde, como el niño Zeus, fue custodiado por los bailarines Curetes . Zeus pretendía que Dioniso fuera su sucesor como gobernante del cosmos, pero una Hera celosa incitó a los Titanes a matar al niño. Damascio afirma que los Titanes se burlaron de él, quienes le dieron un tallo de hinojo ( tirso ) en lugar de su cetro legítimo. [232]

Diodoro relata que Dioniso es hijo de Zeus y Deméter, la diosa de la agricultura, y que la narración de su nacimiento es una alegoría del poder generativo de los dioses en acción en la naturaleza. [233] Cuando los "Hijos de Gea" (es decir, los Titanes) cocieron a Dioniso después de su nacimiento, Deméter reunió sus restos, lo que permitió su renacimiento. Diodoro señaló el simbolismo que este mito tenía para sus seguidores: Dioniso, dios de la vid, nació de los dioses de la lluvia y la tierra. Fue despedazado y cocido por los hijos de Gea, o "nacido de la tierra", que simboliza el proceso de cosecha y elaboración del vino. Así como los restos de las vides desnudas son devueltos a la tierra para restaurar su fecundidad, los restos del joven Dioniso fueron devueltos a Deméter, lo que le permitió nacer de nuevo. [222]

El relato del nacimiento dado por Cayo Julio Higinio ( c. 64 a. C. - 17 d. C.) en Fábulas 167, coincide con la tradición órfica de que Liber (Dionisio) era originalmente hijo de Júpiter (Zeus) y Proserpina (Perséfone). Higinio escribe que Liber fue despedazado por los Titanes, por lo que Júpiter tomó los fragmentos de su corazón y los puso en una bebida que le dio a Sémele , la hija de Harmonía y Cadmo , rey y fundador de Tebas . Esto dio como resultado que Sémele quedara embarazada. Juno se le apareció a Sémele en la forma de su nodriza, Beroe, y le dijo: "Hija, pídele a Júpiter que venga a ti como viene a Juno, para que puedas saber qué placer es dormir con un dios". Cuando Sémele le pidió a Júpiter que lo hiciera, fue asesinada por un rayo. Entonces Júpiter sacó al infante Liber de su vientre y lo puso al cuidado de Niso. Higinio afirma que "por esta razón se le llama Dioniso, y también el que tiene dos madres" ( dimētōr ). [234]

Nonnus describe cómo, cuando la vida se rejuvenecía después del diluvio, faltaba la fiesta en ausencia de Dioniso. "Las estaciones , esas hijas de la lichtgang, aún sin alegría, trenzaban guirnaldas para los dioses hechas de hierba de pradera. Porque faltaba el vino. Sin Baco para inspirar la danza, su gracia estaba sólo a medias y era completamente inútil; encantaba sólo los ojos de la compañía, cuando el bailarín que giraba en círculos se movía en giros y vueltas con un tumulto de pasos, teniendo sólo gestos de aprobación por palabras, mano por boca, dedos por voz". Zeus declaró que enviaría a su hijo Dioniso para enseñar a los mortales cómo cultivar uvas y hacer vino, para aliviar su trabajo, guerra y sufrimiento. Después de convertirse en protector de la humanidad, Zeus promete que Dioniso lucharía en la tierra, pero sería recibido "por el aire brillante superior para brillar junto a Zeus y compartir los cursos de las estrellas" (Dionysiaca 7). [235]

.jpg/440px-Sebastiano_Ricci_-_Dionysus_(1695).jpg)

La princesa mortal Sémele tuvo entonces un sueño en el que Zeus destruía un árbol frutal con un rayo, pero no dañaba la fruta. Envió un pájaro para que le trajera una de las frutas y se la cosió en el muslo, para que fuera a la vez madre y padre del nuevo Dioniso. Ella vio la figura de un hombre con forma de toro emerger de su muslo, y entonces se dio cuenta de que ella misma había sido el árbol. Su padre Cadmo, temeroso del sueño profético, ordenó a Sémele que hiciera sacrificios a Zeus. Zeus se acercó a Sémele en su cama, adornada con varios símbolos de Dioniso. Se transformó en una serpiente, y "Zeus hizo largos cortejos y gritó "¡Euoi!" como si el lagar estuviera cerca, ya que engendró a su hijo que amaría el grito". Inmediatamente, la cama y las habitaciones de Sémele se cubrieron de vides y flores, y la tierra rió. Zeus habló entonces a Sémele, le reveló su verdadera identidad y le dijo que fuera feliz: «Darás a luz un hijo que no morirá, y a ti te llamaré inmortal. ¡Feliz mujer! Has concebido un hijo que hará olvidar a los mortales sus problemas, darás alegría a los dioses y a los hombres» (Dionisíacas 7). [236]

Durante su embarazo, Sémele se regocijó al saber que su hijo sería divino. Se vistió con guirnaldas de flores y coronas de hiedra, y corría descalza a los prados y bosques para retozar cada vez que oía música. Hera sintió envidia y temió que Zeus la reemplazara por Sémele como reina del Olimpo. Fue a ver a Sémele disfrazada de una anciana que había sido nodriza de Cadmo. Hizo que Sémele sintiera celos de la atención que Zeus le daba a Hera, en comparación con su breve relación, y la provocó a pedirle a Zeus que se presentara ante ella en su plena divinidad. Sémele rezó a Zeus para que se mostrara. Zeus respondió a sus oraciones, pero le advirtió que ningún otro mortal lo había visto nunca mientras sostenía sus rayos. Sémele extendió la mano para tocarlos y fue quemada hasta convertirse en cenizas. (Dionisíacas 8). [237] Pero el infante Dioniso sobrevivió, y Zeus lo rescató de las llamas, cosiéndolo en su muslo. «Así, el muslo redondeado en el parto se convirtió en hembra, y el niño nació demasiado pronto, pero no como lo haría una madre, pues había pasado del vientre de una madre al de un padre» (Dionisíaca 9). Al nacer, tenía un par de cuernos en forma de media luna. Las estaciones lo coronaron con hiedra y flores, y envolvieron serpientes cornudas alrededor de sus propios cuernos. [238]

An alternate birth narrative is given by Diodorus from the Egyptian tradition. In it, Dionysus is the son of Ammon, who Diodorus regards both as the creator god and a quasi-historical king of Libya. Ammon had married the goddess Rhea, but he had an affair with Amaltheia, who bore Dionysus. Ammon feared Rhea's wrath if she were to discover the child, so he took the infant Dionysus to Nysa (Dionysus' traditional childhood home). Ammon brought Dionysus into a cave where he was to be cared for by Nysa, a daughter of the hero Aristaeus.[222] Dionysus grew famous due to his skill in the arts, his beauty, and his strength. It was said that he discovered the art of winemaking during his boyhood. His fame brought him to the attention of Rhea, who was furious with Ammon for his deception. She attempted to bring Dionysus under her own power but, unable to do so, she left Ammon and married Cronus.[222]

Even in antiquity, the account of Dionysus' birth to a mortal woman led some to argue that he had been a historical figure who became deified over time, a suggestion of Euhemerism (an explanation of mythic events having roots in mortal history) often applied to demi-gods. The 4th-century Roman emperor and philosopher Julian encountered examples of this belief, and wrote arguments against it. In his letter To the Cynic Heracleios, Julian wrote "I have heard many people say that Dionysus was a mortal man because he was born of Semele and that he became a god through his knowledge of theurgy and the Mysteries, and like our lord Heracles for his royal virtue was translated to Olympus by his father Zeus." However, to Julian, the myth of Dionysus's birth (and that of Heracles) stood as an allegory for a deeper spiritual truth. The birth of Dionysus, Julian argues, was "no birth but a divine manifestation" to Semele, who foresaw that a physical manifestation of the god Dionysus would soon appear. However, Semele was impatient for the god to come, and began revealing his mysteries too early; for her transgression, she was struck down by Zeus. When Zeus decided it was time to impose a new order on humanity, for it to "pass from the nomadic to a more civilized mode of life", he sent his son Dionysus from India as a god made visible, spreading his worship and giving the vine as a symbol of his manifestation among mortals. In Julian's interpretation, the Greeks "called Semele the mother of Dionysus because of the prediction that she had made, but also because the god honored her as having been the first prophetess of his advent while it was yet to be." The allegorical myth of the birth of Dionysus, per Julian, was developed to express both the history of these events and encapsulate the truth of his birth outside the generative processes of the mortal world, but entering into it, though his true birth was directly from Zeus along into the intelligible realm.[13]

According to Nonnus, Zeus gave the infant Dionysus to the care of Hermes. Hermes gave Dionysus to the Lamides, or daughters of Lamos, who were river nymphs. But Hera drove the Lamides mad and caused them to attack Dionysus, who was rescued by Hermes. Hermes next brought the infant to Ino for fostering by her attendant Mystis, who taught him the rites of the mysteries (Dionysiaca 9). In Apollodorus' account, Hermes instructed Ino to raise Dionysus as a girl, to hide him from Hera's wrath.[239] However, Hera found him, and vowed to destroy the house with a flood; however, Hermes again rescued Dionysus, this time bringing him to the mountains of Lydia. Hermes adopted the form of Phanes, most ancient of the gods, and so Hera bowed before him and let him pass. Hermes gave the infant to the goddess Rhea, who cared for him through his adolescence.[238]

Another version is that Dionysus was taken to the rain-nymphs of Nysa, who nourished his infancy and childhood, and for their care Zeus rewarded them by placing them as the Hyades among the stars (see Hyades star cluster). In yet another version of the myth, he is raised by his cousin Macris on the island of Euboea.[240]

Dionysus in Greek mythology is a god of foreign origin, and while Mount Nysa is a mythological location, it is invariably set far away to the east or to the south. The Homeric Hymn 1 to Dionysus places it "far from Phoenicia, near to the Egyptian stream".[241] Others placed it in Anatolia, or in Libya ("away in the west beside a great ocean"), in Ethiopia (Herodotus), or Arabia (Diodorus Siculus).[242]According to Herodotus:

As it is, the Greek story has it that no sooner was Dionysus born than Zeus sewed him up in his thigh and carried him away to Nysa in Ethiopia beyond Egypt; and as for Pan, the Greeks do not know what became of him after his birth. It is therefore plain to me that the Greeks learned the names of these two gods later than the names of all the others, and trace the birth of both to the time when they gained the knowledge.

— Herodotus, Histories 2.146.2

The Bibliotheca seems to be following Pherecydes, who relates how the infant Dionysus, god of the grapevine, was nursed by the rain-nymphs, the Hyades at Nysa. Young Dionysus was also said to have been one of the many famous pupils of the centaur Chiron. According to Ptolemy Chennus in the Library of Photius, "Dionysus was loved by Chiron, from whom he learned chants and dances, the bacchic rites and initiations."[243]

When Dionysus grew up, he discovered the culture of the vine and the mode of extracting its precious juice, being the first to do so;[244] but Hera struck him with madness, and drove him forth a wanderer through various parts of the earth. In Phrygia the goddess Cybele, better known to the Greeks as Rhea, cured him and taught him her religious rites, and he set out on a progress through Asia teaching the people the cultivation of the vine. The most famous part of his wanderings is his expedition to India, which is said to have lasted several years. According to a legend, when Alexander the Great reached a city called Nysa near the Indus river, the locals said that their city was founded by Dionysus in the distant past and their city was dedicated to the god Dionysus.[245] These travels took something of the form of military conquests; according to Diodorus Siculus he conquered the whole world except for Britain and Ethiopia.[246]

Another myth according to Nonnus involves Ampelus, a satyr, who was loved by Dionysus. As related by Ovid, Ampelus became the constellation Vindemitor, or the "grape-gatherer":[247]

... not so will the Grape-gatherer escape thee. The origin of that constellation also can be briefly told. 'Tis said that the unshorn Ampelus, son of a nymph and a satyr, was loved by Bacchus on the Ismarian hills. Upon him the god bestowed a vine that trailed from an elm's leafy boughs, and still the vine takes from the boy its name. While he rashly culled the gaudy grapes upon a branch, he tumbled down; Liber bore the lost youth to the stars."

Another story of Ampelus was related by Nonnus: in an accident foreseen by Dionysus, the youth was killed while riding a bull maddened by the sting of a gadfly sent by Selene, the goddess of the Moon. The Fates granted Ampelus a second life as a vine, from which Dionysus squeezed the first wine.[248]

Returning in triumph to Greece after his travels in Asia, Dionysus came to be considered the founder of the triumphal procession. He undertook efforts to introduce his religion into Greece, but was opposed by rulers who feared it, on account of the disorders and madness it brought with it.

In one myth, adapted in Euripides' play The Bacchae, Dionysus returns to his birthplace, Thebes, which is ruled by his cousin Pentheus. Pentheus, as well as his mother Agave and his aunts Ino and Autonoe, disbelieve Dionysus' divine birth. Despite the warnings of the blind prophet Tiresias, they deny his worship and denounce him for inspiring the women of Thebes to madness.

Dionysus uses his divine powers to drive Pentheus insane, then invites him to spy on the ecstatic rituals of the Maenads, in the woods of Mount Cithaeron. Pentheus, hoping to witness a sexual orgy, hides himself in a tree. The Maenads spot him; maddened by Dionysus, they take him to be a mountain-dwelling lion and attack him with their bare hands. Pentheus' aunts and his mother Agave are among them, and they rip him limb from limb. Agave mounts his head on a pike and takes the trophy to her father Cadmus.

Euripides' description of this sparagmos was as follows:

"But she was foaming at the mouth, her eyes rolled all around; her mind was mindless now. Held by the god, she paid the man no heed. She grabbed his left arm just below the elbow: wedging her foot against the victim's ribs she ripped his shoulder off – not by mere force; the god made easy everything they touch. On his right arm worked Ino, ripping flesh; Autonoë and the mob of maenads griped him, screaming as one. While he had breath, he cried, but they were whooping victory calls. One took an arm, a foot another, boot and all. They stripped his torso bare, staining their nails with blood, then tossed balls of flesh around. Pentheus' body lies in fragments now: on the hard rocks, and mingled with the leaves buried in the woodland, hard to find. His mother stumbled across his head: poor head! She grabbed it, and fixed it on her thrysus, like a lions's, to wave in joyful triumph at her hunt."[250]

The madness passes. Dionysus arrives in his true, divine form, banishes Agave and her sisters, and transforms Cadmus and his wife Harmonia into serpents. Only Tiresias is spared.[251]

In the Iliad, when King Lycurgus of Thrace heard that Dionysus was in his kingdom, he imprisoned Dionysus' followers, the Maenads. Dionysus fled and took refuge with Thetis, and sent a drought which stirred the people to revolt. The god then drove King Lycurgus insane and had him slice his own son into pieces with an axe in the belief that he was a patch of ivy, a plant holy to Dionysus. An oracle then claimed that the land would stay dry and barren as long as Lycurgus lived, and his people had him drawn and quartered. Appeased by the king's death, Dionysus lifted the curse.[252][253] In an alternative version, sometimes depicted in art, Lycurgus tries to kill Ambrosia, a follower of Dionysus, who was transformed into a vine that twined around the enraged king and slowly strangled him.[254]

The Homeric Hymn 7 to Dionysus recounts how, while he sat on the seashore, some sailors spotted him, believing him a prince. They attempted to kidnap him and sail away to sell him for ransom or into slavery. No rope would bind him. The god turned into a fierce lion and unleashed a bear on board, killing all in his path. Those who jumped ship were mercifully turned into dolphins. The only survivor was the helmsman, Acoetes, who recognized the god and tried to stop his sailors from the start.[255]

In a similar story, Dionysus hired a Tyrrhenian pirate ship to sail from Icaria to Naxos. When he was aboard, they sailed not to Naxos but to Asia, intending to sell him as a slave. This time the god turned the mast and oars into snakes, and filled the vessel with ivy and the sound of flutes so that the sailors went mad and, leaping into the sea, were turned into dolphins. In Ovid's Metamorphoses, Bacchus begins this story as a young child found by the pirates but transforms to a divine adult when on board.

Many of the myths involve Dionysus defending his godhead against skeptics. Malcolm Bull notes that "It is a measure of Bacchus's ambiguous position in classical mythology that he, unlike the other Olympians, had to use a boat to travel to and from the islands with which he is associated".[256] Paola Corrente notes that in many sources, the incident with the pirates happens towards the end of Dionysus' time among mortals. In that sense, it serves as final proof of his divinity and is often followed by his descent into Hades to retrieve his mother, both of whom can then ascend into heaven to live alongside the other Olympian gods.[17]

Pausanias, in book II of his Description of Greece, describes two variant traditions regarding Dionysus' katabasis, or descent into the underworld. Both describe how Dionysus entered into the afterlife to rescue his mother Semele, and bring her to her rightful place on Olympus. To do so, he had to contend with the hell dog Cerberus, which was restrained for him by Heracles. After retrieving Semele, Dionysus emerged with her from the unfathomable waters of a lagoon on the coast of the Argolid near the prehistoric site of Lerna, according to the local tradition.[259] This mythic event was commemorated with a yearly nighttime festival, the details of which were held secret by the local religion. According to Paola Corrente, the emergence of Dionysus from the waters of the lagoon may signify a form of rebirth for both him and Semele as they reemerged from the underworld.[17][260] A variant of this myth forms the basis of Aristophanes' comedy The Frogs.[17]

According to the Christian writer Clement of Alexandria, Dionysus was guided in his journey by Prosymnus or Polymnus, who requested, as his reward, to be Dionysus' lover. Prosymnus died before Dionysus could honor his pledge, so to satisfy Prosymnus' shade, Dionysus fashioned a phallus from a fig branch and penetrated himself with it at Prosymnus' tomb.[261][262] This story survives in full only in Christian sources, whose aim was to discredit pagan mythology, but it appears to have also served to explain the origin of secret objects used by the Dionysian Mysteries.[263]

This same myth of Dionysus' descent to the underworld is related by both Diodorus Siculus in his first century BC work Bibliotheca historica, and Pseudo-Apollodorus in the third book of his first century AD work Bibliotheca. In the latter, Apollodorus tells how after having been hidden away from Hera's wrath, Dionysus traveled the world opposing those who denied his godhood, finally proving it when he transformed his pirate captors into dolphins. After this, the culmination of his life on earth was his descent to retrieve his mother from the underworld. He renamed his mother Thyone, and ascended with her to heaven, where she became a goddess.[264] In this variant of the myth, it is implied that Dionysus must prove his godhood to mortals and then also legitimize his place on Olympus by proving his lineage and elevating his mother to divine status, before taking his place among the Olympic gods.[17]

Dionysus discovered that his old school master and foster father, Silenus, had gone missing. The old man had wandered away drunk, and was found by some peasants who carried him to their king Midas (alternatively, he passed out in Midas' rose garden). The king recognized him hospitably, feasting him for ten days and nights while Silenus entertained with stories and songs. On the eleventh day, Midas brought Silenus back to Dionysus. Dionysus offered the king his choice of reward.

Midas asked that whatever he might touch would turn to gold. Dionysus consented, though was sorry that he had not made a better choice. Midas rejoiced in his new power, which he hastened to put to the test. He touched and turned to gold an oak twig and a stone, but his joy vanished when he found that his bread, meat, and wine also turned to gold. Later, when his daughter embraced him, she too turned to gold.

The horrified king strove to divest the Midas Touch, and he prayed to Dionysus to save him from starvation. The god consented, telling Midas to wash in the river Pactolus. As he did so, the power passed into them, and the river sands turned gold: this etiological myth explained the gold sands of the Pactolus.

When Theseus abandoned Ariadne sleeping on Naxos, Dionysus found and married her. They had a son named Oenopion, but she committed suicide or was killed by Perseus. In some variants, Dionysus had her crown put into the heavens as the constellation Corona; in others, he descended into Hades to restore her to the gods on Olympus. Another account claims Dionysus ordered Theseus to abandon Ariadne on the island of Naxos, for Dionysus had seen her as Theseus carried her onto the ship and had decided to marry her.[citation needed] Psalacantha, a nymph, promised to help Dionysus court Ariadne in exchange for his sexual favours; but Dionysus refused, so Psalacantha advised Ariadne against going with him. For this Dionysus turned her into the plant with the same name.[265]

Dionysus fell in love with a nymph named Nicaea, in some versions by Eros' binding. Nicaea however was a sworn virgin and scorned his attempts to court her. So one day, while she was away, he replaced the water in the spring from which she used to drink with wine. Intoxicated, Nicaea passed out, and Dionysus raped her in her sleep. When she woke up and realized what had happened, she sought him out to harm him, but she never found him. She gave birth to his sons Telete, Satyrus, and others. Dionysus named the ancient city of Nicaea after her.[266]

In Nonnus's Dionysiaca, Eros made Dionysus fall in love with Aura, a virgin companion of Artemis, as part of a ploy to punish Aura for having insulted Artemis. Dionysus used the same trick as with Nicaea to get her fall asleep, tied her up, and then raped her. Aura tried to kill herself, with little success. When she gave birth to twin sons by Dionysus, Iacchus and another boy, she ate one twin before drowning herself in the Sangarius river.[267]

Also in the Dionysiaca, Nonnus relates how Dionysus fell in love with a handsome satyr named Ampelos, who was killed by Selene due to him challenging her. On his death, Dionysus changed him into the first grapevine.[268]

A third descent by Dionysus to Hades is invented by Aristophanes in his comedy The Frogs. Dionysus, as patron of the Athenian dramatic festival, the Dionysia, wants to bring back to life one of the great tragedians. After a poetry slam, Aeschylus is chosen in preference to Euripides.

When Hephaestus bound Hera to a magical chair, Dionysus got him drunk and brought him back to Olympus after he passed out.[citation needed]

Callirrhoe was a Calydonian woman who scorned Coresus, a priest of Dionysus, who threatened to afflict all the women of Calydon with insanity (see Maenad). The priest was ordered to sacrifice Callirhoe but he killed himself instead. Callirhoe threw herself into a well which was later named after her.[citation needed]

Dionysus also sent a fox that was fated never to be caught in Thebes. Creon, king of Thebes, sent Amphitryon to catch and kill the fox. Amphitryon obtained from Cephalus the dog that his wife Procris had received from Minos, which was fated to catch whatever it pursued.[citation needed]

Another account about Dionysus's parentage indicates that he is the son of Zeus and Gê (Gaia), also named Themelê (foundation), corrupted into Semele.[269][270]

Hyginus relates that Dionysus once gave human speech to a donkey. The donkey then proceeded to challenge Priapus in a contest about which between them had the better penis; the donkey lost. Priapus killed the donkey, but Dionysus placed him among the stars, above the Crab.[271][272]

The earliest cult images of Dionysus show a mature male, bearded and robed. He holds a fennel staff, tipped with a pine-cone and known as a thyrsus. Later images show him as a beardless, sensuous, naked or half-naked androgynous youth: the literature describes him as womanly or "man-womanish".[284] In its fully developed form, his central cult imagery shows his triumphant, disorderly arrival or return, as if from some place beyond the borders of the known and civilized. His procession (thiasus) is made up of wild female followers (maenads) and bearded satyrs with erect penises; some are armed with the thyrsus, some dance or play music. The god himself is drawn in a chariot, usually by exotic beasts such as lions or tigers, and is sometimes attended by a bearded, drunken Silenus. This procession is presumed to be the cult model for the followers of his Dionysian Mysteries. Dionysus is represented by city religions as the protector of those who do not belong to conventional society and he thus symbolizes the chaotic, dangerous and unexpected, everything which escapes human reason and which can only be attributed to the unforeseeable action of the gods.[285]

Dionysus was a god of resurrection and he was strongly linked to the bull. In a cult hymn from Olympia, at a festival for Hera, Dionysus is invited to come as a bull; "with bull-foot raging". Walter Burkert relates, "Quite frequently [Dionysus] is portrayed with bull horns, and in Kyzikos he has a tauromorphic image", and refers also to an archaic myth in which Dionysus is slaughtered as a bull calf and impiously eaten by the Titans.[286]

The snake and phallus were symbols of Dionysus in ancient Greece, and of Bacchus in Greece and Rome.[287][288][289] There is a procession called the phallophoria, in which villagers would parade through the streets carrying phallic images or pulling phallic representations on carts. He typically wears a panther or leopard skin and carries a thyrsus. His iconography sometimes includes maenads, who wear wreaths of ivy and serpents around their hair or neck.[290][291][292]