King's College London (informalmente King's o KCL ) es una universidad pública de investigación ubicada en Londres , Inglaterra. King's fue establecida por carta real en 1829 bajo el patrocinio del rey Jorge IV y el duque de Wellington . [9] [10] En 1836, King's se convirtió en uno de los dos colegios fundadores de la Universidad de Londres . [11] Es una de las instituciones de nivel universitario más antiguas de Inglaterra . [12] [13] A fines del siglo XX, King's creció a través de una serie de fusiones, incluidas con Queen Elizabeth College y Chelsea College of Science and Technology (en 1985), el Instituto de Psiquiatría (en 1997), las Escuelas Médicas y Dentales Unidas de Guy's y St Thomas' Hospitals y la Escuela de Enfermería y Obstetricia Florence Nightingale (en 1998).

King's tiene cinco campus: su histórico Strand Campus en el centro de Londres, otros tres campus cercanos a la orilla del Támesis (Guy's, St Thomas' y Waterloo) y uno en Denmark Hill en el sur de Londres . También tiene presencia en Shrivenham , Oxfordshire , para su educación militar profesional, y otra en Newquay , Cornualles , donde se encuentra su centro de servicios de información. Sus actividades académicas están organizadas en nueve facultades, que se subdividen en numerosos departamentos, centros y divisiones de investigación. En 2022/23, King's tuvo un ingreso total de £ 1.230 millones, de los cuales £ 236,3 millones fueron de subvenciones y contratos de investigación. [4] Tiene la cuarta dotación más grande de cualquier universidad en el Reino Unido, y la más grande de todas en Londres. King's es la quinta universidad más grande del Reino Unido por matrícula total [6] y recibe más de 69.000 solicitudes de pregrado por año (36.000 nacionales y 33.000 internacionales). [14]

King's es miembro de organizaciones académicas que incluyen la Asociación de Universidades de la Commonwealth , la Asociación Universitaria Europea y el Grupo Russell . King's es el hogar del Centro MRC para Trastornos del Neurodesarrollo del Consejo de Investigación Médica y es miembro fundador del centro académico de ciencias de la salud King's Health Partners , el Instituto Francis Crick y MedCity . Es el centro europeo más grande para la enseñanza médica de grado y posgrado y la investigación biomédica, por número de estudiantes, [15] e incluye la primera escuela de enfermería del mundo, la Facultad de Enfermería y Obstetricia Florence Nightingale . [16] King's generalmente se considera parte del " triángulo dorado " de universidades ubicadas en las ciudades de Oxford, Cambridge y Londres. [17] King's a menudo ha tenido patrocinio real en virtud de su fundación, con la difunta reina Isabel II como patrona y su hijo, el rey Carlos III, asumiendo el patrocinio en mayo de 2024. [18] [19]

Entre los antiguos alumnos y el personal del King's se incluyen 14 premios Nobel ; contribuyentes al descubrimiento de la estructura del ADN , la hepatitis C , el genoma de la hepatitis D y el bosón de Higgs ; pioneros de la fertilización in vitro , la clonación de células madre y mamíferos y el movimiento moderno de cuidados paliativos ; e investigadores clave que hicieron avanzar el radar, la radio, la televisión y los teléfonos móviles. Entre los antiguos alumnos también se incluyen jefes de estado, gobiernos y organizaciones intergubernamentales; diecisiete miembros de la actual Cámara de los Comunes , dos Portavoces de la Cámara de los Comunes y trece miembros de la actual Cámara de los Lores ; y los ganadores de tres Oscar , tres Grammy , un Emmy , un Globo de Oro y un Premio Booker .

El King's College, llamado así para indicar el patrocinio del rey Jorge IV , fue fundado en 1829 (aunque las raíces de la escuela de medicina del King, St. Thomas, se remontan al siglo XVI con la primera enseñanza registrada en 1561) [3] en respuesta a la controversia teológica en torno a la fundación de la "Universidad de Londres" (que más tarde se convirtió en University College, Londres ) en 1826. [20] [21] La Universidad de Londres fue fundada, con el respaldo de utilitaristas , judíos y no conformistas , como una institución secular, destinada a educar "a la juventud de nuestra gente rica mediana entre las edades de 15 o 16 y 20 o más tarde" [22] dando su apodo, "la universidad sin Dios en Gower Street". [23] La necesidad de tal institución fue el resultado de la naturaleza religiosa y social de las universidades de Oxford y Cambridge, que entonces educaban únicamente a los hijos de anglicanos ricos . [24] La naturaleza secular de la Universidad de Londres ganó desaprobación; de hecho, "las tormentas de oposición que rugieron a su alrededor amenazaron con aplastar cada chispa de energía vital que quedaba". [25]

La creación del King's College como institución rival representó una respuesta Tory para reafirmar los valores educativos del orden establecido. [26] En términos más generales, King's fue una de las primeras de una serie de instituciones que surgieron a principios del siglo XIX como resultado de la Revolución Industrial y los grandes cambios sociales en Inglaterra después de las Guerras Napoleónicas . [27] En virtud de su fundación, King's ha disfrutado del patrocinio del monarca , el arzobispo de Canterbury como su visitante y durante el siglo XIX contó entre sus gobernadores oficiales con el Lord Canciller , el presidente de la Cámara de los Comunes y el Lord Mayor de Londres . [27]

El apoyo simultáneo de Arthur Wellesley, primer duque de Wellington (que también era primer ministro del Reino Unido en ese momento), a un King's College anglicano en Londres y a la Ley de Ayuda Católica Romana , que conduciría a la concesión de derechos civiles casi completos a los católicos, fue desafiado por George Finch-Hatton, décimo conde de Winchilsea , a principios de 1829. Winchilsea y sus partidarios deseaban que el King's estuviera sujeto a las Leyes de Prueba , como las universidades de Oxford , donde solo los miembros de la Iglesia de Inglaterra podían matricularse , y Cambridge , donde los no anglicanos podían matricularse pero no graduarse, [28] pero esta no era la intención de Wellington. [29]

Winchilsea y otros 150 colaboradores retiraron su apoyo al King's College de Londres en respuesta al apoyo de Wellington a la emancipación católica . En una carta a Wellington, acusó al duque de tener en mente "diseños insidiosos para la violación de nuestra libertad y la introducción del papado en todos los departamentos del Estado". [30] La carta provocó un furioso intercambio de correspondencia y Wellington acusó a Winchilsea de imputarle "motivos vergonzosos y criminales" por haber creado el King's College de Londres. Cuando Winchilsea se negó a retractarse de sus comentarios, Wellington -según su propia admisión, "no era partidario del duelo" y era un duelista novato- exigió una satisfacción en un duelo de armas: "Ahora pido a su señoría que me dé esa satisfacción por su conducta que un caballero tiene derecho a exigir, y que un caballero nunca se niega a dar". [31]

El resultado fue un duelo en Battersea Fields el 21 de marzo de 1829. [21] [32] Winchilsea no disparó, un plan que él y su segundo casi seguramente decidieron antes del duelo; Wellington apuntó y disparó desviado hacia la derecha. Los relatos difieren en cuanto a si Wellington falló a propósito. Wellington, conocido por su mala puntería, afirmó que sí, otros informes más comprensivos con Winchilsea afirmaron que había apuntado a matar. [33] El honor se salvó y Winchilsea le escribió a Wellington una disculpa. [30] El "Día del Duelo" todavía se celebra el primer jueves después del 21 de marzo de cada año, marcado por varios eventos en King's, incluidas recreaciones. [32] [34]

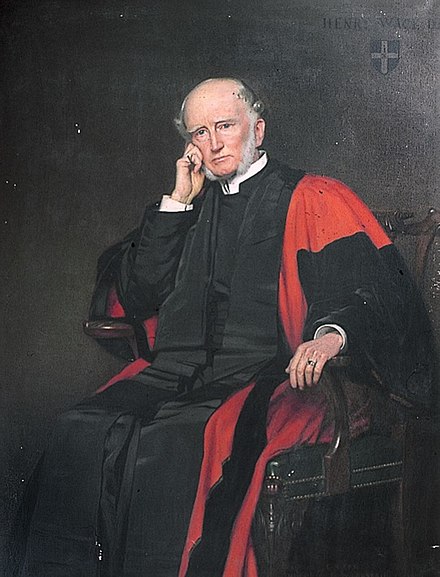

King's abrió sus puertas en octubre de 1831 con el clérigo William Otter designado como primer director y profesor de teología. [20] El arzobispo de Canterbury presidió la ceremonia de apertura, en la que Charles James Blomfield , obispo de Londres , pronunció un sermón en la capilla sobre el tema de combinar la instrucción religiosa con la cultura intelectual. A pesar de los intentos de hacer que King's fuera sólo para anglicanos, el prospecto inicial permitía que "los no conformistas de todo tipo ingresaran libremente al colegio". [35] William Howley : los gobernadores y los profesores, excepto los lingüistas, tenían que ser miembros de la Iglesia de Inglaterra, pero los estudiantes no, [36] aunque la asistencia a la capilla era obligatoria. [37]

King's se dividió en un departamento superior y un departamento junior, también conocido como King's College School , que originalmente estaba situado en el sótano del Strand Campus. [20] El departamento Junior comenzó con 85 alumnos y solo tres profesores, pero rápidamente creció a 500 en 1841, superando sus instalaciones y lo llevó a mudarse a Wimbledon en 1897, donde permanece hoy, aunque ya no está asociado con King's College London. [36] Dentro del departamento superior, la enseñanza se dividió en tres cursos: un curso general que comprendía teología, lenguas clásicas, matemáticas, literatura inglesa e historia; un curso de medicina; y materias diversas, como derecho, economía política e idiomas modernos, que no estaban relacionadas con ningún curso sistemático de estudio en ese momento y dependían para su continuidad del suministro de estudiantes ocasionales. [20] En 1833, el curso general se reorganizó, lo que llevó a la concesión del título de Asociado del King's College (AKC), la primera calificación emitida por King's. [20] El curso, que aborda cuestiones de ética y teología, todavía se imparte hoy en día a estudiantes y personal que cursan un curso opcional de tres años simultáneamente con sus estudios.

La fachada del río se completó en abril de 1835 con un coste de 7.100 libras esterlinas [38] , y su finalización fue una condición para que el King's College de Londres consiguiera el terreno de la Corona. [20] A diferencia de los de la escuela, el número de estudiantes del departamento superior se mantuvo casi estacionario durante los primeros cinco años de existencia de King's College. Durante este tiempo, la escuela de medicina se vio afectada por la ineficiencia y las lealtades divididas del personal, lo que llevó a una disminución constante de la asistencia. Uno de los nombramientos más importantes fue el de Charles Wheatstone como profesor de Filosofía experimental. [20]

En esa época, ni la King's, ni la "London University" ni las facultades de medicina de los hospitales de Londres podían otorgar títulos. En 1835, el gobierno anunció que establecería una junta examinadora para otorgar títulos, y que la "London University" y la King's se convertirían en colegios afiliados. Esta se convirtió en la Universidad de Londres en 1836, y la antigua "London University" pasó a llamarse University College, London (UCL). [24] Los primeros títulos de la Universidad de Londres se otorgaron a los estudiantes del King's College London en 1839. [39]

En 1840, el King 's College Hospital abrió su propio hospital en Portugal Street, cerca de Lincoln's Inn Fields , una zona compuesta por colonias superpobladas caracterizadas por la pobreza y la enfermedad. La administración del King's College Hospital fue posteriormente transferida a la corporación del hospital establecida por la Ley del King's College Hospital de 1851. El hospital se trasladó a nuevas instalaciones en Denmark Hill , Camberwell en 1913. El nombramiento en 1877 de Joseph Lister como profesor de cirugía clínica benefició enormemente a la escuela de medicina, y la introducción de los métodos quirúrgicos antisépticos de Lister le valió al hospital una reputación internacional. [20]

En 1845, King's estableció un Departamento Militar para entrenar a los oficiales del Ejército y de la Compañía Británica de las Indias Orientales , y en 1846 un Departamento Teológico para entrenar a los sacerdotes anglicanos. En 1855, King's fue pionero en las clases nocturnas en Londres; [36] el hecho de que King's otorgara a los estudiantes de las clases nocturnas certificados de asistencia a la universidad para permitirles presentarse a los exámenes de grado de la Universidad de Londres fue citado como un ejemplo de la inutilidad de estos certificados en la decisión de la Universidad de Londres de terminar con el sistema de colegios afiliados en 1858 y abrir sus exámenes a todos. [40]

ElLa Ley del King's College de Londres de 1882 (45 y 46 Vict.c. xiii) modificó la constitución. La ley eliminó la naturaleza propietaria del King's, cambiando el nombre de la corporación de "The Governors and Proprietors of King's College, London" a "King's College London" y anulando el estatuto de 1829 (aunque el King's permaneció incorporado bajo ese estatuto). La ley también cambió el King's College de Londres de una corporación (técnicamente) con fines de lucro a una corporación sin fines de lucro (nunca se habían pagado dividendos en más de 50 años de funcionamiento) y amplió los objetivos del King's para incluir la educación de las mujeres.[20][41]El Departamento de Damas del King's College de Londres se inauguró enKensington Squareen 1885, que más tarde, en 1902, se convirtió en el Departamento de Mujeres del King's College.[39]

ElLa Ley del King's College de Londres de 1903 (3.ª Edw. 7.c. xcii) abolió todas las pruebas religiosas restantes para el personal, excepto dentro del departamento de Teología. En 1910, el King's (con excepción del departamento de Teología) se fusionó con la Universidad de Londres bajo laLey de transferencia del King's College de Londres de 1908 (8.ª Edw. 7.c. xxxix), perdiendo su independencia jurídica.[42]

Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, la facultad de medicina se abrió a las mujeres por primera vez. [20] De 1916 a 1921, el Departamento de Italiano de la facultad estuvo dirigido por una mujer, Linetta de Castelvecchio . [43] El final de la guerra supuso una afluencia de estudiantes, lo que sobrecargó las instalaciones existentes hasta el punto de que algunas clases se impartían en la casa del director. [20]

Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, los edificios del King's College de Londres fueron utilizados por el Servicio Auxiliar de Bomberos , con varios miembros del personal del King's College, principalmente los entonces conocidos como sirvientes del colegio, que servían como vigilantes de incendios . Partes del edificio Strand, el cuadrilátero y el techo del ábside y las vidrieras de la capilla sufrieron daños por las bombas en el Blitz . [44] [45] Durante la reconstrucción de posguerra, las bóvedas debajo del cuadrilátero fueron reemplazadas por un laboratorio de dos pisos, que se inauguró en 1952, para los departamentos de Física e Ingeniería Civil y Eléctrica. [20]

Una de las piezas más famosas de investigación científica realizada en King's fueron las contribuciones cruciales al descubrimiento de la estructura de doble hélice del ADN en 1953 por Maurice Wilkins y Rosalind Franklin , junto con Raymond Gosling , Alex Stokes , Herbert Wilson y otros colegas de la División Randall de Biofísica Celular y Molecular en King's. [46] [47] [48]

En 1966, tras la publicación del Informe Robbins sobre la Educación Superior, se inició una importante reconstrucción de King's. En 1972 se inauguró un nuevo edificio frente al Strand, diseñado por ED Jefferiss Mathews. [36] En 1980, King's recuperó su independencia jurídica en virtud de una nueva Carta Real. En 1993, King's, junto con otros grandes colegios de la Universidad de Londres, obtuvo acceso directo a la financiación gubernamental (que anteriormente había sido a través de la universidad) y el derecho a otorgar títulos de la Universidad de Londres por sí misma. Esto contribuyó a que King's y los otros grandes colegios fueran considerados universidades de facto por derecho propio. [49]

El King's College de Londres sufrió varias fusiones con otras instituciones a finales del siglo XX, entre ellas la reincorporación en 1983 de la Escuela de Medicina y Odontología del King's College, que se había independizado del King's College Hospital en la fundación del Servicio Nacional de Salud en 1948, las fusiones con el Queen Elizabeth College y el Chelsea College en 1985, y el Instituto de Psiquiatría en 1997. En 1998, las Escuelas Médicas y Dentales Unidas de los Hospitales Guy's y St Thomas' se fusionaron con el King's para formar la Escuela de Educación Médica GKT . [36] [39] [50] [51] También en 1998, la escuela de formación original de Florence Nightingale para enfermeras se fusionó con el Departamento de Estudios de Enfermería del King's como la Escuela de Enfermería y Obstetricia Florence Nightingale . Ese mismo año, King's adquirió el antiguo edificio de la Oficina de Registro Público en Chancery Lane y lo convirtió, con un coste de 35 millones de libras, en la Biblioteca Maughan , que abrió sus puertas en 2002. [36]

En julio de 2006, el Consejo Privado otorgó al King's College de Londres poderes para otorgar títulos por derecho propio, en lugar de a través de la Universidad de Londres . [53] Este poder permaneció inactivo hasta 2007, cuando el King's anunció que todos los estudiantes que comenzaran cursos a partir de septiembre de 2007 recibirían títulos otorgados por el propio King's, en lugar de por la Universidad de Londres. Sin embargo, los nuevos certificados aún hacen referencia al hecho de que el King's es un colegio constituyente de la Universidad de Londres. [54] A todos los estudiantes actuales con al menos un año de estudio restante se les ofreció en agosto de 2007 la opción de elegir recibir un título de la Universidad de Londres o un título del King's. Los primeros títulos del King's se otorgaron en el verano de 2008. [55]

En abril de 2011, King's se convirtió en socio fundador del Centro de Investigación e Innovación Médica del Reino Unido, posteriormente rebautizado como Instituto Francis Crick , y destinó 40 millones de libras al proyecto. [56] El departamento de Química se reabrió en 2011 tras su cierre en 2003. [57] En febrero de 2012, Su Majestad la Reina inauguró oficialmente el ala este de Somerset House.

En septiembre de 2014, el King's College de Londres abrió la King's College London Mathematics School , una escuela gratuita de sexto grado ubicada en Lambeth que se especializa en matemáticas. [58] En octubre de 2014, Ed Byrne reemplazó a Rick Trainor como director del King's College de Londres, este último después de haber servido durante 10 años. En diciembre de 2014, King's anunció sus planes de cambiar su nombre a 'King's London'. [59] Se enfatizó que no había planes para cambiar el nombre legal de King's, y que el nombre 'King's London' fue diseñado para promover King's y resaltar el hecho de que King's es una universidad por derecho propio. [60] King's anunció que los planes de cambio de marca habían sido abandonados en enero de 2015. [61] [62]

En 2015, King's adquirió un contrato de arrendamiento de 50 años para el sitio de Aldwych Quarter que incorpora la histórica Bush House . Ha estado ocupado desde 2017. [63]

El campus de Strand es el campus fundador de King's y está ubicado en el Strand en la ciudad de Westminster , compartiendo su frente con el río Támesis . El campus original comprende el edificio King's de 1831, catalogado como de Grado I , diseñado por Sir Robert Smirke , y la capilla del King's College de Londres rediseñada en 1864 por Sir Gilbert Scott , con la posterior compra de gran parte de la adyacente Surrey Street (incluidos los edificios Norfolk y Chesham) desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial y el edificio Strand de 1972. El edificio Macadam de 1975 alberga la Unión de Estudiantes del Campus Strand y lleva el nombre del ex alumno de King's Sir Ivison Macadam , primer presidente de la Unión Nacional de Estudiantes .

El campus de Strand alberga las facultades de artes y ciencias de King's, incluidas las facultades de Artes y Humanidades , Derecho , Negocios, Ciencias Sociales y Políticas Públicas y Ciencias Naturales, Matemáticas e Ingeniería. También alberga la Oficina del Presidente y el Director.

Desde 2010, el campus se ha expandido rápidamente para incorporar el ala este de Somerset House y el edificio Virginia Woolf, junto a la LSE en Kingsway . También se ha expandido para incorporar Bush House , que anteriormente albergaba el BBC World Service .

Las estaciones de metro más cercanas son Temple , Charing Cross y Covent Garden .

El campus de Guy está situado cerca del Puente de Londres y el Shard en la orilla sur del Támesis y alberga la Facultad de Ciencias de la Vida y Medicina y el Instituto Dental. [64]

El campus recibe su nombre de Thomas Guy , el fundador y benefactor del Guy's Hospital establecido en 1726 en el distrito londinense de Southwark . Los edificios incluyen: el edificio Henriette Raphael, construido en 1902, el Museo Gordon de Patología , el edificio Hodgkin, Shepherd's House y Guy's Chapel. El sindicato de estudiantes tiene amplias instalaciones en el Guy's Campus, que incluyen salas de actividades, salas de reuniones junto con una cafetería para estudiantes; The Shed y un bar para estudiantes; Guy's Bar. El Guy's Campus está ubicado frente al Old Operating Theatre Museum , que era parte del antiguo St Thomas Hospital en Southwark.

Las estaciones de metro más cercanas son London Bridge y Borough .

El Campus de Waterloo está ubicado al otro lado del Puente de Waterloo desde el Campus de Strand, cerca del Centro Southbank en el distrito londinense de Lambeth y está formado por el edificio James Clerk Maxwell , el edificio Franklin - Wilkins y el edificio del ala del Puente de Waterloo.

Cornwall House, ahora el edificio Franklin-Wilkins, construido entre 1912 y 1915 fue originalmente la Oficina de Papelería de Su Majestad (responsable de los derechos de autor de la Corona y de los Archivos Nacionales ), pero fue requisado para su uso como hospital militar en 1915 durante la Primera Guerra Mundial. Se convirtió en el Hospital Militar King George y alojó a unos 1.800 pacientes en 63 salas. [65]

Actualmente es el edificio universitario más grande de Londres. El edificio fue adquirido por King's en la década de 1980 y se sometió a una amplia remodelación en 2000. [66] [67] El edificio lleva el nombre de Rosalind Franklin y Maurice Wilkins por sus importantes contribuciones al descubrimiento de la estructura del ADN. [66] Hoy es el hogar de:

El edificio adyacente James Clerk Maxwell alberga la Facultad de Enfermería, Obstetricia y Cuidados Paliativos de Florence Nightingale y muchas de las funciones de servicios profesionales centrales de la universidad. El edificio recibió su nombre en honor al físico matemático escocés James Clerk Maxwell , quien fue profesor de Filosofía Natural en King's de 1860 a 1865. [68]

La estación de metro más cercana es Waterloo .

El campus de St Thomas en el distrito londinense de Lambeth , frente a las Casas del Parlamento al otro lado del Támesis, alberga partes de la Escuela de Medicina y el Instituto Dental. El Museo Florence Nightingale también se encuentra aquí. [69] El museo está dedicado a Florence Nightingale, la fundadora de la Escuela de Formación Nightingale del Hospital St Thomas (ahora Facultad de Enfermería, Obstetricia y Cuidados Paliativos Florence Nightingale del King's). El Hospital St Thomas pasó a formar parte de la Escuela de Medicina del King's College de Londres en 1998. El Hospital St Thomas y el campus recibieron el nombre de St Thomas Becket . [70] El Departamento de Investigación de Gemelos ( TwinsUk ) del King's College de Londres se encuentra en el Hospital St. Thomas.

La estación de metro más cercana es Westminster .

El campus de Denmark Hill está situado en el sur de Londres, cerca de los límites del distrito londinense de Lambeth y el distrito londinense de Southwark en Camberwell , y es el único campus que no está situado en el río Támesis. El campus consta del King's College Hospital , el Maudsley Hospital y el Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience (IoPPN). Además del Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, aquí se encuentran partes del Dental Institute y la School of Medicine, y una gran residencia universitaria, King's College Hall. Otros edificios incluyen la biblioteca del campus conocida como Weston Education Centre (WEC), el James Black Centre, el Rayne Institute (hemato-oncología) y el Cicely Saunders Institute ( cuidados paliativos ). [71]

El Instituto de Neurociencia Clínica Maurice Wohl fue inaugurado por la Princesa Real en 2015 en el Campus de Denmark Hill. [72] Lleva el nombre del filántropo británico Maurice Wohl , quien tuvo una larga asociación con King's y apoyó muchos proyectos médicos. [73]

La estación de Overground más cercana es Denmark Hill .

Aunque no es un campus formal, King's mantiene una presencia académica y una propiedad en la Academia de Defensa del Reino Unido en Shrivenham , Oxfordshire . A través de su Departamento de Estudios de Defensa, King's ha brindado capacitación militar profesional a gran parte de las fuerzas armadas del Reino Unido a través del Joint Services Command and Staff College desde 2000 bajo contrato con el Ministerio de Defensa . [74]

Entre 1999 y 2010, más de la mitad de las actividades del King's College se trasladaron a edificios nuevos o reformados. [75] Los principales proyectos de este período incluyeron una renovación de 40 millones de libras de la antigua oficina de registros públicos para convertirse en la Biblioteca Maughan en 2002, una renovación de 40 millones de libras de los edificios del King's College entre 2004 y 2006, y la renovación del ala este de Somerset House entre 2009 (cuando la universidad consiguió un contrato de arrendamiento de 78 años) y 2012, y la finalización del Instituto de Cuidados Paliativos Cicely Saunders de 10 millones de libras en el campus de Denmark Hill. [76] Más recientemente, en 2016 se completó un desarrollo de 42 millones de libras para el Instituto de Neurociencia Clínica Maurice Wohl, [77] y en 2016 se construyó un pabellón deportivo en el campo de deportes Honor Oar Park. [78]

La remodelación del campus Strand ganó el premio Green Gown en 2007 por construcción sostenible. El premio reconoció la "reducción de las emisiones de carbono y de energía gracias a una remodelación sostenible del histórico South Range del King's Building". [79] King's también recibió el premio City Heritage Award en 2003 por la conversión de la biblioteca Maughan , catalogada como de Grado II* . [80]

En abril de 2012 se anunció una remodelación de 20 millones de libras del Strand Quadrangle entre el King's Building y Somerset House . [81] Esta remodelación se completó en 2022. Además de la creación de nuevos espacios sociales en el cuadrilátero, se remodeló el espacio debajo del cuadrilátero para proporcionar 3000 metros cuadrados de nuevos laboratorios y espacios de enseñanza para el departamento de ingeniería. [82]

En julio de 2015, King's adquirió contratos de arrendamiento para varios edificios en el barrio de Aldwych por un período inicial de 50 años. Estos edificios han estado ocupados desde 2017 y contienen departamentos académicos, espacios de aprendizaje y sociales e instalaciones para estudiantes. [83] El entonces presidente y director, Edward Byrne, dijo que la adquisición representó "un momento decisivo en la historia de King's, asegurando la posición de la universidad durante 50 años y más". [84]

Una remodelación de tres años del Strand dirigida por el Ayuntamiento de Westminster vio la creación de un espacio peatonal que unificó el área entre Bush House y el resto del Campus Strand, mejorando la seguridad y la accesibilidad, en lo que antes era una de las calles más congestionadas de la capital. [85]

King's también ha adquirido la propiedad absoluta del ala suroeste de Bush House, que actualmente se encuentra en desarrollo para su posible uso como nuevo centro de aprendizaje y se espera que esté terminado en 2026. [86]

El director del King's College de Londres es formalmente el presidente y director , actualmente Shitij Kapur , quien comenzó su mandato en junio de 2021, tras la jubilación de Sir Ed Byrne en enero de 2021.

El cargo de "Director y Presidente de la Facultad" está establecido por la carta real del Rey como "el principal funcionario académico y ejecutivo de la Facultad" [87] y los estatutos de la facultad requieren que el presidente y el director tengan la responsabilidad general ante el consejo de la facultad de "garantizar que se cumplan los objetivos de la Universidad y de mantener y promover la eficiencia, la disciplina y el buen orden de la Universidad". [88] El actual presidente y director, Shitji Kapoor, utiliza el título de "Vicerrector y Presidente". [89] Los funcionarios superiores actuales de la facultad incluyen tres vicepresidentes superiores, que cubren las áreas de: académico; salud y ciencias de la vida; y operaciones. También hay cinco vicepresidentes que cubren las áreas de: finanzas (también el director financiero de la facultad); educación y éxito estudiantil; internacional, compromiso y servicio; investigación e innovación; y personas y talento. [90]

El consejo universitario es el órgano de gobierno supremo del King's College de Londres establecido en virtud de la carta y los estatutos, y está compuesto por 21 miembros. Entre sus miembros se incluyen el presidente de la Unión de Estudiantes del King's College de Londres (KCLSU), como miembro estudiante; el director y presidente; hasta siete miembros más del personal; y hasta 12 miembros laicos que no deben ser empleados del King's. [91] Cuenta con el apoyo de una serie de comités permanentes. [92] Sir Christopher Geidt , ex secretario privado de Su Majestad la Reina Isabel II (el patrón del King's College de Londres en el momento en que asumió el papel de presidente) sucedió a Charles Wellesley, noveno duque de Wellington, como presidente del consejo desde el comienzo del año académico 2016; [93] [94] posteriormente se convirtió en Lord Geidt el 3 de noviembre de 2017. [95]

La actual decana del King's College de Londres es la reverenda Dra. Ellen Clark-King . [90] El cargo de decano lo establecen las ordenanzas del colegio y, según las ordenanzas aprobadas por el consejo del colegio en julio de 2022, tiene que ser un ministro ordenado de la Iglesia de Inglaterra . [96] Que el decano sea una persona ordenada es inusual entre las universidades británicas, pero refleja la fundación del King en la tradición de la Iglesia de Inglaterra en 1829. [97] El decano es "responsable de supervisar el desarrollo espiritual y el bienestar de todos los estudiantes y el personal". La Oficina del Decano coordina el programa de Asociación del King's College , la Capellanía del Colegio y el Coro del King's College de Londres, que incluye una serie de becas corales. [97] [98] Una de las funciones del decano es alentar y fomentar las vocaciones al sacerdocio de la Iglesia de Inglaterra . [99]

El arzobispo de Canterbury es el visitador del King's College de Londres por derecho de cargo debido a la fundación anglicana del King's. [100] El visitante actual es el Reverendísimo Justin Welby .

En el siglo XIX, el King's College de Londres tenía cinco departamentos: Teología, Literatura y Ciencias Generales, Ciencias Aplicadas, Medicina y Militares. [101] [102] El Departamento de Teología proporcionaba estudios de historia eclesiástica , teología pastoral y exégesis de testamentos. [102] Lenguas y literatura, historia, derecho y jurisprudencia, economía política, comercio, esgrima, matemáticas, zoología e historia natural se enseñaban dentro del Departamento de Literatura y Ciencias Generales, [102] y filosofía natural, geología, mineralogía y materias relacionadas con las artes se enseñaban dentro del Departamento de Ciencias Aplicadas. [102]

En 2017 [update], King's cuenta con nueve facultades académicas, que se subdividen en escuelas (para Ciencias Sociales y Políticas Públicas, Ciencias de la Vida y Medicina), departamentos, centros y divisiones de investigación. La última incorporación fue King's Business School, ubicada en Bush House , que abrió sus puertas en agosto de 2017. [103]

La Facultad está situada en el Strand, en el corazón del centro de Londres , en las proximidades de muchas instituciones culturales de renombre con las que la Facultad tiene estrechos vínculos, incluido el Museo Británico , el Shakespeare's Globe , la National Portrait Gallery , el Courtauld Institute of Art y la Biblioteca Británica . [104] En el QS World University Rankings 2024, King's ocupó el puesto 22 en el mundo y el 5 en el Reino Unido en Artes y Humanidades. [105]

La Facultad de Artes y Humanidades se formó en 1989 tras la fusión de las facultades de Artes, Música y Teología. [106] King's Arts & Humanities se distingue por representar una fortaleza excepcional tanto en las disciplinas más establecidas (como Filosofía, Clásicos, Teología, Inglés, Historia, Idiomas y Música) como por su calidad líder a nivel mundial en campos establecidos más recientemente (como Humanidades Digitales, Cine, Artes Liberales Interdisciplinarias y Cultura, Medios e Industrias Creativas). [107]

En 2023, la Facultad puso en marcha dos nuevos Institutos [108] – el Instituto de Futuros Digitales y el Instituto de Culturas Globales – para reunir proyectos existentes y promover una educación e investigación nuevas y originales, centrándose en el bienestar y el impacto social.

La Facultad de Odontología, Ciencias Orales y Craneofaciales (anteriormente Instituto Dental) es la escuela de odontología de King's y se centra en comprender las enfermedades, mejorar la salud y restaurar la función. [109] La Facultad ocupa el quinto lugar en el mundo en Odontología, según QS World University Rankings. [110] El instituto es el sucesor de la Escuela de Odontología del Guy's Hospital, la Escuela de Odontología del King's College Hospital, la Escuela de Cirugía Dental del Royal Dental Hospital of London y las Escuelas Médicas y Dentales Unidas de los Hospitales Guy's y St Thomas . Fue parte de la Escuela de Medicina y Odontología de King's hasta 2005, cuando la escuela de odontología se convirtió en el Instituto Dental y luego cambió de nombre en 2019.

En 1799 Joseph Fox comenzó a dar una serie de conferencias sobre cirugía dental en el Guy's Hospital, y fue nombrado cirujano dental en el mismo año. [111] Thomas Bell sucedió a Fox como cirujano dental en 1817 o 1825. [111] Frederick Newland-Pedley , quien fue nombrado cirujano dental asistente en el Guy's Hospital en 1885, abogó por el establecimiento de una escuela de odontología dentro del hospital, e inundó las dos escuelas de odontología de Londres, la Metropolitan School of Dental Science y la London School of Dental Surgery, con pacientes para demostrar que se necesitaba un hospital más. [111] En diciembre de 1888, se estableció la Escuela de Odontología del Guy's Hospital. [111] [112] La Guy's Hospital Dental School fue reconocida como una escuela de la Universidad de Londres en 1901. En la década de 1970, dado que hubo una disminución en la demanda de servicios dentales, el Departamento de Salud del Reino Unido sugirió que debería haber una disminución en el número de estudiantes de odontología de pregrado, así como la duración de todos los cursos. [111] En respuesta a las recomendaciones, la Royal Dental Hospital of London School of Dental Surgery se fusionó con la Guy's Hospital Dental School de las United Medical and Dental Schools of Guy's and St Thomas' Hospitals el 1 de agosto de 1983. [111]

El establecimiento de la Escuela de Odontología del King's College Hospital fue propuesto por el vizconde Hambleden en una reunión del Comité de Gestión del Hospital el 12 de abril de 1923. La escuela de odontología se inauguró el 12 de noviembre de 1923 en el King's College Hospital. [51] En virtud de la Ley Nacional de Salud de 1948, la Escuela de Medicina y Odontología del King's se separó de King's y se convirtió en una escuela independiente, pero la escuela volvió a fusionarse con King's en 1983. [51] La escuela se fusionó además con las Escuelas de Medicina y Odontología Unidas de los Hospitales Guy's y St Thomas' en 1998. [51]

La Facultad de Ciencias de la Vida y Medicina se creó como resultado de la fusión de la Escuela de Medicina con la Escuela de Ciencias Biomédicas en 2014. [113] En el QS World University Rankings 2024, King's ocupó el puesto 12 en el mundo y el 5 en el Reino Unido en Ciencias de la Vida y Medicina. [114]

Hay dos escuelas de educación en la Facultad de Ciencias de la Vida y Medicina: la Escuela de Educación Médica GKT es responsable de la educación médica y la formación de los estudiantes en el programa MBBS , y la Escuela de Educación en Biociencias es responsable de la educación y la formación en profesiones biomédicas y de la salud. [115] La facultad se divide a su vez en 7 escuelas, que incluyen Biociencias Básicas y Médicas, Ingeniería Biomédica y Ciencias de la Imagen, Cáncer y Ciencias Farmacéuticas, Medicina y Ciencias Cardiovasculares, Inmunología y Ciencias Microbianas, Ciencias del Curso de Vida y Ciencias de la Salud de la Población. [116]

El Instituto de Psiquiatría, Psicología y Neurociencia (IoPPN) es una facultad y una institución de investigación dedicada a descubrir qué causa las enfermedades mentales y las enfermedades del cerebro , y a ayudar a identificar nuevos tratamientos para las enfermedades. [117] El instituto es el mayor centro de investigación y educación de posgrado en psiquiatría, psicología y neurociencia en Europa. [118] Originalmente establecido en 1924 como la Escuela de Medicina del Hospital Maudsley, el instituto cambió su nombre a Instituto de Psiquiatría en 1948, se fusionó con King's College London en 1997 y pasó a llamarse IoPPN en 2014. [119] [120] En el QS World University Rankings 2024, King's ocupó el puesto 16 en el mundo en Psicología. [121]

La Escuela de Derecho Dickson Poon es la facultad de derecho de King's. La enseñanza del derecho se lleva impartiendo en King's desde 1831. [122] La Facultad de Derecho se fundó en 1909 y se convirtió en la Escuela de Derecho en 1991. [122] Entre las facultades de derecho más prestigiosas y selectivas del mundo, en 2024 se clasificó entre las 15 mejores a nivel mundial y la quinta en Europa y el Reino Unido según el QS World University Rankings. [123]

La escuela incluye varios centros y grupos de investigación que sirven como puntos focales para la actividad de investigación, incluido el Centro de Derecho Europeo (establecido en 1974), el Centro de Derecho Médico y Ética (establecido en 1978), el Centro de Derecho Constitucional Británico e Historia (establecido en 1988), el Centro de Derecho de la Construcción, el Centro de Tecnología, Ética y Derecho en la Sociedad, el Centro de Política, Filosofía y Derecho, el Instituto de Derecho Transnacional y el Comité de Derecho Fiduciario. [124]

La Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Matemáticas se estableció en 2010, tras la reorganización de la Escuela de Ciencias Físicas e Ingeniería. Fue renombrada en febrero de 2021 para incorporar el regreso de la ingeniería como disciplina principal. La facultad brinda educación e investigación en química, informática, física, matemáticas, ingeniería y telecomunicaciones. Física y Matemáticas se han estudiado en la universidad desde 1829 y 1830 respectivamente, y hay seis premios Nobel que fueron estudiantes o personal académico de la facultad. [125] En particular, su enseñanza de Física experimental es la más antigua de Inglaterra, habiendo fomentado las cátedras de James Clerk Maxwell , Harold A. Wilson , Charles Glover Barkla , Sir Owen Richardson , Sir Edward Appleton y Sir Charles Ellis , tres de los cuales se convirtieron en premios Nobel. [126]

La química se enseña en King's desde su fundación en 1829, y el medallista Copley John Frederic Daniell fue nombrado el primer profesor. [127] El Departamento de Química se vio obligado a cerrar en 2003 debido a una disminución en el número de estudiantes y la reducción de la financiación. [127] En 2012, se estableció un nuevo Departamento de Química y se lanzó una nueva licenciatura, Química con Biomedicina. [127] El nuevo departamento cubre áreas tradicionales de la química (química orgánica, inorgánica, física y computacional) y otras disciplinas académicas, incluida la biología celular y la física. [127]

El Departamento de Ingeniería se estableció en 1838, lo que lo convierte posiblemente en la escuela de ingeniería más antigua del Reino Unido. [128] Del mismo modo, la King's College Engineering Society es la sociedad más antigua de su tipo, ya que se fundó en 1847, seis días antes que la Institution of Mechanical Engineers . El Departamento de Ingeniería fue la escuela de ingeniería más grande del Reino Unido en 1893. [128] [129] La División de Ingeniería se cerró en 2013 y se reinstaló en 2019. [128] [130]

La Facultad de Enfermería y Obstetricia Florence Nightingale es una escuela para enfermeras y parteras. También lleva a cabo investigaciones en enfermería y ofrece programas de desarrollo profesional continuo y de posgrado. Anteriormente conocida como Nightingale Training School and Home for Nurses, la facultad fue fundada por Florence Nightingale en 1860 y es la primera escuela de enfermería del mundo en estar conectada de forma continua a un hospital y una escuela de medicina que prestan todos sus servicios. [131] [132] En el QS World University Rankings 2024, King's ocupó el segundo puesto en el mundo en Enfermería. [133]

La Escuela de Formación Nightingale se fusionó en 1996 con la Escuela de Obstetricia Olive Haydon y la Escuela de Enfermería Thomas Guy y Lewisham, y todo el personal y los estudiantes se integraron en King's en 1996. [132] [134]

La Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Políticas Públicas se estableció en 2001 y es uno de los centros universitarios más grandes centrados en la investigación orientada a políticas en el Reino Unido. [135] Tras una reestructuración en 2016, se dividió en cuatro escuelas:

El Departamento de Estudios de Guerra es único en el Reino Unido y cuenta con el apoyo de centros de investigación como el Centro King's para Comunicaciones Estratégicas, el Centro Liddell Hart para Archivos Militares y el Centro King's para Investigación de Salud Militar (KCMHR). [136]

Creado en 2002, el Centro del Rey para la Gestión de Riesgos (KCRM) realiza investigaciones internacionales relacionadas con la gestión de riesgos, la gobernanza y la comunicación, y apoya diversos proyectos, conferencias y becas académicas, facilitando la traducción de las investigaciones sobre riesgos en soluciones políticas pertinentes y prácticas. [137]

La facultad también alberga el Centro de Liderazgo Africano, el Instituto de Historia Británica Contemporánea y el Centro Asia Pacífico de Ciencias Sociales de Londres. [138]

.jpg/440px-Bush_House_30_Aldwych,_London_WC2B_4BG_(3).jpg)

La King's Business School se estableció en agosto de 2017 en Bush House . La Escuela de Administración y Negocios dentro de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Políticas Públicas se reformó para crear la King's Business School. [139] La escuela ocupó el segundo lugar en la clasificación de 2021 de The Complete University Guide en el Reino Unido para estudios de Negocios y Administración. [140]

Tras la ampliación de la escuela de negocios, se formaron cuatro centros de investigación de la siguiente manera: [141]

La King's Business School ofrece títulos de grado y posgrado. Ofrece programas en economía, administración, finanzas, emprendimiento, gestión de recursos humanos y marketing. Los cursos de administración de grado basan su plan de estudios en "la teoría empresarial moderna y la teoría y práctica de la gestión organizacional". Otros campos que se superponen con el contenido central que se enseña incluyen finanzas, contabilidad, economía, ciencias sociales, psicología y derecho. Los cursos de grado como Administración de Empresas cuentan con un alto porcentaje de estudiantes internacionales (81%) y una gran cohorte femenina, que comprende el 58% del cuerpo estudiantil. [142] [143]

En el año financiero que finalizó el 31 de julio de 2019, King's tuvo un ingreso total de £901,96 millones (2017/18 - £841,03 millones) y un gasto total de £1089,88 millones (2017/18 - £842,43 millones). [144] Las principales fuentes de ingresos incluyeron £393,79 millones de tasas de matrícula y contratos educativos (2017/18 - £342,25 millones), £194,68 millones de subvenciones y contratos de investigación (2017/18 - £194,42 millones), £128,30 millones de subvenciones del Consejo de Financiación (2017/18 - £123,89 millones) y £5,12 millones de ingresos por donaciones e inversiones (2017/18 - £6,19 millones). [144] Durante el año fiscal 2018/19, King's tuvo un gasto de capital de £78,9 millones (2017/18 – £133,7 millones). [144]

Al 31 de julio de 2019, King's tenía dotaciones totales de £258,07 millones (31 de julio de 2018: £233,46 millones) y activos netos totales de £791,58 millones (31 de julio de 2018: £945,86 millones). [144] King's tiene una calificación crediticia de AA de Standard & Poor's . [144] Su dotación total es la cuarta más alta entre las universidades del Reino Unido; solo detrás de Oxford , Cambridge y Edimburgo .

En 2013/14, King's tuvo el séptimo ingreso total más alto de todas las universidades británicas. [145] Para 2018/19, ahora es sexto después de superar el ingreso total de la Universidad de Edimburgo .

En octubre de 2010, King's lanzó una importante campaña de recaudación de fondos, "Preguntas del mundo | Las respuestas de King", liderada por el ex primer ministro británico John Major , con el objetivo de recaudar £500 millones para 2015. [146] Esta meta fue superada incluso antes de 2015 y King's aumentó posteriormente el objetivo a £600 millones. [147] Nuevamente cumplió y superó este nuevo objetivo al recaudar £610 millones. [148]

King's ha recibido numerosas subvenciones de la Fundación Bill y Melinda Gates para apoyar diversos proyectos de investigación en salud global y desarrollo global . [149]

El escudo de armas que aparece en la carta fundacional del King's College de Londres es el de Jorge IV. El escudo representa el escudo de armas real junto con un blasón de la Casa de Hannover , mientras que los soportes encarnan el lema del rey , sancte et sapienter . No se cree que haya sobrevivido correspondencia sobre la elección de este escudo de armas, ni en los archivos del King's ni en el College of Arms , y se han utilizado diversas adaptaciones no oficiales a lo largo de la historia del King's. El escudo de armas actual se desarrolló tras las fusiones con el Queen Elizabeth College y el Chelsea College en 1985 e incorpora aspectos de su heráldica. [8] El escudo de armas oficial, en terminología heráldica , es: [150]

Brazos:

O sobre un Azul Pálido entre dos Leones rampantes respetuosos de Gules, un Ancla de Oro encabezada por una Corona Real propiamente dicha sobre un Jefe de Plata, una Lámpara Antigua propiamente dicha inflamada de Oro entre dos Hogares Ardientes también propiamente dichos .

El escudo y los seguidores:

Sobre un Yelmo con una Corona de Oro y Azul Sobre un Libro apropiado elevándose desde una Corona de Oro el borde engastado con joyas dos de Azul (uno manifiesto) cuatro de Vert (dos manifiestos) y dos de Gules un medio León de Gules sosteniendo una Vara de Dexter una figura femenina vestida de Azul la capa forrada con cofia y mangas de Plata sosteniendo en la mano exterior una Cruz Larga botonadura de Oro y siniestra una figura masculina el Abrigo Largo de Azul adornado con Sable camisa apropiada de Plata sosteniendo en la mano interior un Libro apropiado .

Aunque la Escuela de Medicina del Hospital St Thomas y la Escuela de Medicina Guy se convirtieron en entidades legales separadas del Hospital St Thomas y del Hospital Guy en 1948, la tradición de utilizar los escudos y blasones de los hospitales continúa hoy en día. [151]

En 1949, la Escuela de Medicina del Hospital St Thomas obtuvo su propio escudo de armas. Sin embargo, el escudo de armas del Hospital St Thomas todavía se ha utilizado. [151] La Escuela de Medicina de Guy propuso solicitar su propio escudo de armas después de separarse del Hospital Guy, pero la escuela decidió continuar utilizando los brazos del Hospital Guy en 1954. [151] Las dos escuelas de medicina se fusionaron en 1982 y se convirtieron en las Escuelas Médicas y Dentales Unidas de los Hospitales Guy y St Thomas (UMDS). Simon Argles, secretario de la UMDS, dijo que debido al nombre de la escuela de medicina era más apropiado utilizar el escudo de armas del hospital. [151]

En 1998, la UMDS se fusionó con el King's College Hospital para convertirse en la Guy's, King's and St Thomas' School of Medicine. Los escudos de los hospitales Guy's y St Thomas' se utilizan junto con el escudo del King's en las publicaciones de las escuelas de medicina y los materiales de graduación. [151]

King's College London es una institución miembro y fue uno de los dos colegios fundadores de la Universidad federal de Londres . [152] En 1998, King's se unió al Grupo Russell , una asociación de 24 universidades públicas de investigación establecida en 1994. [153] King's también es miembro de la Red Institucional de Universidades de las Capitales de Europa (UNICA), una red de instituciones de educación superior con sede en capitales europeas, [154] y de la Asociación de Universidades de la Commonwealth (ACU), la Asociación Universitaria Europea (EUA) y Universities UK .

Por lo general, se considera que King's forma parte del " triángulo dorado ", una agrupación de universidades de investigación ubicadas en las ciudades inglesas de Cambridge, Oxford y Londres que generalmente también incluye las universidades de Cambridge y Oxford, el Imperial College de Londres, la London School of Economics y el University College de Londres. [168]

King's College London también es parte de King's Health Partners , un centro académico de ciencias de la salud que comprende Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust , King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust y el propio King's College London. [169] [170] [171] King's es un participante y uno de los miembros fundadores del Francis Crick Institute . [172] Además, lanzado en 2014, MedCity es la colaboración entre King's y las otras dos principales universidades científicas de Londres, Imperial College y University College London. [173]

En 2016, King's College London, junto con la Universidad Estatal de Arizona y la Universidad de Nueva Gales del Sur , formaron la PLuS Alliance , una alianza universitaria internacional para abordar los desafíos globales. [174] [175] King's también es el socio fundador de FutureLearn , una plataforma masiva de aprendizaje de cursos abiertos en línea fundada en diciembre de 2012.

King's ofrece titulaciones conjuntas con muchas universidades y otras instituciones, entre ellas la Universidad de Columbia , [176] la Universidad de París I , [176] la Universidad de Hong Kong , [176] la Universidad Nacional de Singapur , [177] la Real Academia de Música , [178] la Biblioteca Británica , [178] la Tate Modern , [178] el Shakespeare's Globe , [178] la Galería Nacional , [178] la Galería Nacional de Retratos [178] y el Museo Británico . [179] [180]

En el campo de las matemáticas , el King's College de Londres tiene una empresa conjunta con el Imperial College de Londres y el University College de Londres que gestiona la London School of Geometry and Number Theory (LSGNT), que es un centro de formación doctoral (CDT) financiado por el EPSRC. La LSGNT ofrece una amplia gama de proyectos de investigación de doctorado de cuatro años de duración en diferentes aspectos de la teoría de números, la geometría y la topología. [181]

Otra colaboración que el King's College London mantiene con el Imperial College London y el University College London es en el campo de la nanotecnología, donde las tres universidades gestionan conjuntamente el Centro de Nanotecnología de Londres (LCN). El LCN es un centro de investigación multidisciplinario en nanotecnología física y biomédica centrado en la explotación y comercialización de la investigación generada en los campos pertinentes.

El King's College de Londres se unió a la alianza de investigación en ingeniería y ciencias físicas del SES en 2016, que incluye a las universidades de Cambridge, Oxford y Southampton, el Imperial College de Londres, la Queen Mary University de Londres y el University College de Londres como miembros. [182] El King's College de Londres también es miembro del Centro Thomas Young , una alianza de grupos de investigación de Londres que trabajan en la teoría y simulación de materiales, junto con el Imperial College de Londres, el University College de Londres y la Queen Mary University de Londres. [183]

La universidad también es miembro del Grupo de Estudios Cinematográficos de la Universidad de Londres junto con otras instituciones de la Universidad de Londres. [184]

En 2018, King's ocupó el puesto 13.º en cuanto a calificación de ingreso promedio para estudiantes de pregrado entre todas las universidades del Reino Unido, y los nuevos estudiantes obtuvieron un promedio de 171 puntos UCAS. [191] En 2022, la universidad ofreció admisión al 39,3 % de sus postulantes, la octava más baja del país. [192]

El 24,4% de los estudiantes de grado de King's reciben educación privada , la decimocuarta proporción más alta entre las universidades británicas tradicionales. [193] En el año académico 2016-17, la universidad tenía una distribución por domicilio de 67:12:20 de estudiantes del Reino Unido: UE: no UE respectivamente con una proporción de mujeres a hombres de 62:37. [194]

Una solicitud de libertad de información en 2015 reveló que la universidad recibió 31.857 solicitudes de pregrado y realizó 13.302 ofertas en 2014-15. Esto resultó en una tasa de oferta del 41,8%, una tasa de rendimiento de las ofertas del 45,3% y una tasa de aceptación general del 18,9%. [195] En 2018, King's College London recibió 39.102 solicitudes de pregrado, con solo 4.728 plazas aceptadas, lo que significa una tasa de aceptación general del 12,1%. [196] La Facultad de Medicina recibió 1.764 solicitudes, solo se realizaron 39 ofertas, lo que resultó en una tasa de oferta de solo el 2,2%. Enfermería y obstetricia, fisioterapia y odontología clínica tuvieron las tasas de oferta más bajas del 14%, 16% y 17% respectivamente. [197]

El año académico de King se extiende desde el último lunes de septiembre hasta el primer viernes de junio. [198] Las distintas facultades y departamentos adoptan diferentes estructuras de semestres académicos. Por ejemplo, el año académico de la Escuela de Matemáticas y el Departamento de Estudios de Guerra se divide en tres semestres (otoño, primavera y verano); [199] [200] mientras que el año académico de la Facultad de Artes y Humanidades se desarrolla en dos semestres. [201]

Las ceremonias de graduación se llevan a cabo en enero (invierno) y junio o julio (verano). Las ceremonias para los estudiantes de la mayoría de las facultades se llevan a cabo en el Southbank Centre, junto al campus de Waterloo , a orillas del Támesis. Hasta 2018, las ceremonias se llevaron a cabo en el complejo artístico más grande de Europa, el Barbican Centre .

Debido a las raíces de la Escuela de Medicina de St Thomas, que se pueden rastrear hasta el Priorato de St Mary Overie , los estudiantes de la Escuela de Educación Médica GKT y de la Facultad de Ciencias Dentales, Orales y Craneofaciales se gradúan en la Catedral de Southwark, adyacente al Campus de Guy. [202]

Después de que se le concediera el poder de otorgar sus propios títulos independientemente de la Universidad de Londres en 2006, [53] los graduados comenzaron a usar la vestimenta académica del King's College de Londres en 2008. Desde entonces, los graduados del King's han usado vestidos diseñados por Vivienne Westwood . [203]

En 2022/23, King's tuvo un ingreso total por investigación de £236,3 millones, de los cuales £68,4 millones procedieron de consejos de investigación; £48,3 millones del gobierno central del Reino Unido; £12,1 millones de la industria del Reino Unido; £60,6 millones de organismos benéficos del Reino Unido; £22,5 millones de fuentes de la UE; £24,4 millones de otras fuentes. [4]

En el Research Excellence Framework (REF) de 2021, que evalúa la calidad de la investigación en las instituciones de educación superior del Reino Unido, King's ocupa el noveno puesto por GPA y el sexto por poder de investigación (la puntuación media de notas de una universidad, multiplicada por el número equivalente a tiempo completo de investigadores presentados). [204] King's presentó un total de 1.369 miembros del personal en 27 unidades de evaluación a la evaluación del Research Excellence Framework (REF) de 2014 (en comparación con los 1.172 presentados al Research Assessment Exercise (RAE 2008) de 2008). [205] En los resultados del REF, el 40% de la investigación presentada por King's se clasificó como 4*, el 45% como 3*, el 13% como 2* y el 2% como 1*, lo que arroja un GPA general de 3,23. [206] En las clasificaciones elaboradas por Times Higher Education basadas en los resultados del REF, King's ocupó el sexto lugar en general en cuanto a poder de investigación y el séptimo en cuanto a GPA (en comparación con el undécimo y el vigésimo segundo puesto, respectivamente, en las clasificaciones equivalentes de la RAE 2008). [206] Times Higher Education describió a King's como "posiblemente el mayor ganador" en REF2014 después de que subió 15 puestos en GPA, mientras que presentó a unas 200 personas más. [205]

La investigación médica en el King's College de Londres se distribuye en varias facultades, en particular la Facultad de Odontología, Ciencias Orales y Craneofaciales, la Facultad de Enfermería, Obstetricia y Cuidados Paliativos Florence Nightingale, y la Facultad de Ciencias de la Vida y Medicina. [207]

King's afirma ser el mayor centro de educación sanitaria de Europa. [15] La Facultad de Ciencias de la Vida y Medicina tiene tres hospitales docentes principales: Guy's Hospital , King's College Hospital y St Thomas' Hospital [208] , y un campus filial en Portsmouth administrado en colaboración con la Universidad de Portsmouth . [209] El King's College London Dental Institute era la escuela de odontología más grande de Europa en 2010. [update][ 210] La Escuela de Enfermería y Obstetricia Florence Nightingale, que pasó a formar parte de King's en 1993, es la escuela profesional de enfermería más antigua del mundo. [211]

King's es un importante centro de investigación biomédica. Es miembro fundador de King's Health Partners , uno de los mayores centros académicos de ciencias de la salud de Europa, con una facturación de más de 2.000 millones de libras y aproximadamente 25.000 empleados. [15] También alberga el Centro MRC para Trastornos del Neurodesarrollo del Consejo de Investigación Médica , [212] y forma parte de dos de los doce centros de investigación biomédica establecidos por el Instituto Nacional de Investigación en Salud y Atención (NIHR) en Inglaterra: el Centro de Investigación Biomédica del NIHR en Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust y King's College London, y el Centro de Investigación Biomédica del NIHR en South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust y King's College London. [213]

El Centro de Control de Drogas de King's se estableció en 1978 y es el único laboratorio antidopaje acreditado por la AMA en el Reino Unido y posee el contrato oficial del Reino Unido para realizar pruebas de dopaje a atletas del país. [214] En 1997, se convirtió en el primer laboratorio acreditado por el Comité Olímpico Internacional en cumplir con el estándar de calidad ISO/IEC 17025. [215] El centro fue la instalación antidopaje para los Juegos Olímpicos y Paralímpicos de Londres 2012. [216]

Las instalaciones de la biblioteca de King's están distribuidas en sus campus. Las colecciones abarcan más de un millón de libros impresos, así como miles de revistas y recursos electrónicos.

The Maughan Library is King's largest library and is housed in the Grade II* listed 19th century gothic former Public Record Office building situated on Chancery Lane at the Strand Campus. The building was designed by Sir James Pennethorne and is home to the books and journals of the Schools of Arts & Humanities, Law, Natural & Mathematical Sciences, and Social Science & Public Policy. It also houses the Special Collections and rare books. Inside the Library is the octagonal Round Reading Room, inspired by the reading room of the British Museum, and the former Rolls Chapel (renamed the Weston Room following a donation from the Garfield Weston Foundation) with its stained glass windows, mosaic floor and monuments, including a Renaissance terracotta figure by Pietro Torrigiano of Dr Yonge, Master of the Rolls, who died in 1516.

Additionally, King's students and staff have full access to Senate House Library, the central library for the University of London and the School of Advanced Study.[231] Undergraduate and postgraduate students also have reference access to libraries of other University of London institutions under the University of London Libraries Access Agreement.[232]

King's currently operates two museums: Gordon Museum of Pathology and Museum of Life Sciences. Opened in 1905 at Guy's Campus, the Gordon Museum is the largest medical museum in the United Kingdom,[233] and houses a collection of approximately 8000 pathological specimens, artefacts, models and paintings, including Astley Cooper's specimens and Sir Joseph Lister's antiseptic spray.[234] The Museum of Life Sciences was founded in 2009 adjacent to the Gordon Museum, and it houses historic biological and pharmaceutical collections from the constituent colleges of the modern King's College London.[235]

Between 1843 and 1927, the King George III Museum was a museum within King's College London which housed the collections of scientific instruments of George III and eminent nineteenth-century scientists (including Sir Charles Wheatstone and Charles Babbage). Due to space constraints within King's, much of the museum's collections were transferred on loan to the Science Museum in London or kept in King's College London Archives.[236]

The Anatomy Museum was a museum situated on the 6th floor of the King's Building at the Strand Campus. The Anatomy Theatre was built next door to the museum in 1927,[237] where anatomical dissections and demonstrations took place. The Anatomy Museum's collection includes casts of injuries, leather models, skins of various animals from Western Australia donated to the museum in 1846,[238] and casts of heads of John Bishop and Thomas Williams, the murderers in the Italian Boy's murder in 1831.[239] The last dissection in the Anatomy Theatre was performed in 1997.[237] The Anatomy Theatre and Museum was renovated and refurbished in 2009, and is now a facility for teaching, research and performance at King's.[240]

The Foyle Special Collections Library also houses a number of special collections, range in date from the 15th century to present, and in subject from human anatomy to Modern Greek poetry.[241] The Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) Historical Collection is the largest collection contains material from the former FCO Library. The collection was a working tool used by the British government to inform and influence foreign and colonial policy.[242] Transferred to King's in 2007, the FCO Historical Collection contains over 80,000 items including books, pamphlets, manuscript, and photographic material.[242] The Medical Collection include the historical library collections of the constituent medical schools and institutes of King's. The Rare Books Collection holds 12,000 printed books, including a 1483 Venice printing of Silius Italicus's Punica, first editions of Charles Dickens' novels, and the 1937 (first) edition of George Orwell's The Road to Wigan Pier.[243]

King's College London Archives holds the institution's records, which are among the richest higher education records in London.[244] King's archives collections include institutional archives of King's since 1828, archives of institutions and schools that were created by or have merged with King's, and records relating to the history of medicine. Founded in 1964, the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives holds the private papers of over 800 senior British defence personnel who held office since 1900.[245]

Science Gallery London is set to open in 2018 on the Guy's Campus.[246] It is a public science centre where 'art and science collide',[247] and is a part of Global Science Gallery Network.[246][248] A flagship project for 'Culture at King's College London', Science Gallery will include 2,000 m2 (21,528 sq ft) of public space and a newly landscaped Georgian courtyard.[247] There will be exhibition galleries, theatres, meeting spaces and a café; while unlike other science centre, it will have no permanent collection.[247] Daniel Glaser, the former Head of Engaging Science at Wellcome Trust, is Director of Science Gallery London.[247]

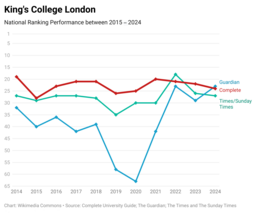

Among global university rankings, King's is ranked 40th equal by the 2025 QS World University Rankings, [255]38th equal by the 2024 world university rankings of the Times Higher Education, [256]36th equal by the 2024 U.S. News & World Report Best Global Universities Rankings,[257] 53rd by the 2024 Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU).[258]

According to the 2025 Complete University Guide, 16 subjects offered by King's rank within the top 10 nationally, including Health Studies (1st), Social Policy (2nd), Business & Management Studies (3rd), Anthropology (4th), Law (5th), Music (6th), Classics (6th), Economics (8th), Politics (8th), Communication & Media Studies (8th), Food Science (9th), Philosophy (9th), Dentistry (9th), Biological Sciences (10th), History (10th), and Computer Science (10th). [259] The Guardian University Guide 2021 ranks King's in the top ten in 6 subjects, including Psychology (2nd), Politics (5th), Law (6th), Anatomy & physiology (8th), Media & film studies (9th), and Philosophy (9th). The Times Higher Education ranks King's College London the top 20 universities in the world for Psychology (11th), and Clinical, pre-clinical & health (16th) in the 2021 World University Rankings by subject.[260] King's College London has had 24 of its subject-areas awarded the highest rating of 5 or 5* for research quality in the 2004 Research Assessment Exercise,[261] and in 2007 it received a good result in its audit by the Quality Assurance Agency.[261]

King's was ranked joint 14th overall in The Sunday Times 10-year (1998–2007) average ranking of British universities based on consistent league table performance.[262] In recent years, however, the university has performed less well in domestic league tables, being placed outside of the top 20 in all three major tables for 2016. The methodologies of these tables include student satisfaction scores with teaching and feedback as a significant input.[263][264] In common with most other London institutions, King's performs less well on the National Student Survey (NSS), ranking 133rd for student satisfaction (out of 160 institutes) in the 2015 survey.[265]

According to the 2015 Times and Sunday Times University Guide, their inclusion of student satisfaction scores, along with international guides including reputation scores from academics and employers, explains the disparity between King's ranking on their (domestic) table and global tables. They add that when the university is ranked according to student satisfaction scores from undergraduates on factors such as academic support, teaching, assessment and feedback, "King's ranks 106 out of 123 institutions", although "despite the iffy student satisfaction scores, students continue to apply here in their droves" with an average of 8.1 applicants per place available for 2014 entry.[266] However, although the Complete University Guide has used the results of the NSS since at least 2011,[267] King's retained a position in their top 20 until the 2015 tables (published 2014),[268] managing 19th on the 2014 tables despite ranking joint 102nd (out of 124) for student satisfaction.[269]

King's was ranked 7th in the UK for Graduate Employability in the Times Higher Education's Global Employability University Ranking 2023.[270] King’s was further recognised by the High Fliers' Graduate Market Report 2024 as one of the top universities targeted by leading UK employers. [271] This is reaffirmed by the Teaching Excellence Framework (2023) which gave King's a gold rating for student outcomes.[272]

In a survey by The New York Times assessing the most valued graduates by business leaders, King's College London graduates ranked 22nd in the world and 5th in the UK.[273] In the 2015 Global Employability University Survey of international recruiters, King's is ranked 43rd in the world and 7th in the UK.[274] King's was chosen as the 5th best UK university by major British employers in 2015.[275]

In 2014, King's ranked 5th amongst multidisciplinary UK universities for highest graduate starting salaries (i.e. graduates' average annual salary six months after graduation).[276] In a big data research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, University of Cambridge and Harvard University, it was revealed the top 10% of King's male graduates working in England were the 7th highest earning students 10 years after graduation in comparison to graduates of all Higher Education providers (both multi and uni-disciplinary universities) in the UK and the top 10% of its female graduates were the 9th highest earning students 10 years after graduation in the same study.[277] The Guardian University Guide 2017 named King's as the 6th best university in the country for graduate career prospects, with 84.3% of students finding graduate-level jobs within six months of graduation.[278]

In September 2010, the Sunday Times selected King's as the "University of the Year 2010–11".[279] King's was ranked as the 5th best university in the UK for the quality of graduates according to recruiters from the UK's major companies.[280]

The Associateship of King's College (AKC) is the original award of King's College, dating back to its foundation in 1829 and first awarded in 1835. It was designed to reflect the twin objectives of King's College's 1829 royal charter to maintain the connection between "sound religion and useful learning" and to teach the "doctrines and duties of Christianity".[281]

Today, the AKC is a modern tradition that offers an inclusive, research-led programme of lectures that gives students the opportunities to engage with religious, philosophical and ethical issues alongside their main degree course. Graduates of King's College London may be eligible to be elected as 'Associates' of King's College by the authority of King's College London council, delegated to the academic board. After election, they are entitled to use the post-nominal letters "AKC".[282]

The Fellowship of King's College (FKC) is the highest award that can be bestowed upon an individual by King's College London. The award of the fellowship is governed by a statute of King's College London and reflects distinguished service to King's by a member of staff, conspicuous service to King's, or the achievement of distinction by those who were at one time closely associated with King's College London.[283]

The proposal to establish a fellowship of King's was first considered in 1847.[284] John Allen, a former chaplain of King's, was the first FKC. Each fellow had to pay two guineas for the fellowship privilege initially, but the fee was ceased from 1850.[284] A wide variety of people were elected as fellows of King's, including former principal Alfred Barry, former King's student then professor Thorold Rogers, architect William Burges and ornithologist Robert Swinhoe.[284] The first women fellows were elected in 1904.[284] Lilian Faithfull, vice-principal of the King's Ladies' Department from 1894 to 1906, was one of the first women fellows.[284]

Founded in 1873,[285] King's College, London Union Society which later, in 1908, reorganised into King's College London Students' Union, better known by its acronym KCLSU, is the oldest students' union in London (University College London Union being founded in 1893)[286] and has a claim to being the oldest Students' Union in England.[287][288] Athletic Club was one of the nineteenth-century student societies at King's formed in 1884.[289] The union provides a wide range of activities and services, including over 50 sports clubs (which includes the boat club which rows on the River Thames and the rifle club which uses the college's shooting range located at the disused Aldwych tube station beneath the Strand Campus),[290] over 300 activity groups,[291] a wide range of volunteering opportunities, bars and cafes (The Shack, The Shed, The Vault and Guy's Bar), and a shop (The Union Shop). Between 1992 and 2013 the union operated a nightclub, Tutu's, named after alumnus Desmond Tutu.[292] The union also previously operated Waterfront Bar until 2018, when it was replaced by The Vault, and Philosophy Bar until 2020, which was closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic and financial difficulty.[293]

The former President of KCLSU, Sir Ivison Macadam, after whom the former students' union building on the Strand Campus (Macadam Building) is named, went on to be elected as the first president of the National Union of Students.[294]

"Reggie the Lion" (informally "Reggie") is the official mascot of the students' union. In total there are four Reggies in existence. The original can be found on display in the undercroft of the Union's Bush House base at the Strand Campus. A papier-mâché Reggie lives outside the Great Hall at the Strand Campus. The third Reggie, given as a gift by alumnus Willie Kwan, guards the entrance of Willies Common Room in Somerset House East Wing.[295] A small sterling silver incarnation is displayed during graduation ceremonies, which was presented to King's by former Halliburton Professor of Physiology, Robert John Stewart McDowall, in 1959.[296]

KCLSU Student Media won Student Media of the Year 2014 at the Ents Forum awards[297] and came in the top three student media outlets in the country at the NUS Awards 2014.[298]

Roar News is a tabloid newspaper for students at King's which is owned and funded by KCLSU. It is editorially independent of both the university and the students' union and its award-winning website is read by tens of thousands of people per month in over 100 countries.[299] In 2014 it had a successful awards season, scooping several national awards and commendations, including a Mind Media Award and Student Media of the Year.[298][300]

The radio station of KCLSU, KCL Radio, was founded in 2009 as a podcast producer. The first live broadcast of KCL Radio was in 2011 at the London Varsity.[301] In 2013, KCL Radio relaunched as a live station with more than 45 hours of live programming a week. The schedule of the radio station includes news, music, entertainment, debate, sport and live performance.[301]

Other King's student media groups include the student television station KingsTV, and the photographic society KCLSU PhotoSoc.[302]

There are over 60 sports clubs, many of which compete in the University of London and British Universities & Colleges (BUCS) leagues across the South East.[290] The annual Macadam Cup is a varsity match played between the sports teams of King's College London proper (KCL) and King's College London Medical School (KCLMS). King's students and staff have played an important part in the formation of the London Universities and Colleges Athletics.

Created in January 2013, King's Sport, a partnership between King's College London and KCLSU, manages all the sports activities and facilities of King's.[303][304] King's Sport runs three fitness centres at the Waterloo, Guy's and Strand Campuses which include various studio spaces. King's Sport also operates three sports grounds in New Malden, Honor Oak Park and Dulwich.[305] There are also on-campus sports facilities at Guy's, St Thomas's and Denmark Hill campuses.[306] King's students and staff can utilize Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust's fitness centre and swimming pool based within the Guy's and St Thomas' hospitals.[306][307]

In addition to sporting clubs, King's College London also boast 300 other societies and groups in a wide variety of activities.[291] The societies are categorised by fourteen main groups: Business, Finance & Entrepreneur Ship; Culture; Medical; Faith & Spirituality; Academic; Common Interest; Music & Performance; Fundraising; Political; Volunteering & Fundraising; Cultural; Arts & Creative; Media; Causes & Campaigning.

Following the 2010 student demonstrations against increased tuition fees, King's College London students founded London's first student-led think tank, King's Think Tank (formerly known as KCL Think Tank).[308] With a membership of more than 2000,[309][310] it is the largest organisation of its kind in Europe.[311] This student initiative organises lectures and discussions in seven different policy areas, and assists students in lobbying politicians, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other policymakers with their ideas. Every May, it produces a peer-reviewed journal of policy recommendations called The Spectrum.[312][313]

There are many music societies at King's including a cappella groups, orchestras, choir, musical theatre and jazz society.[314] King's has three orchestras: King's College London Symphony Orchestra (KCLSO), King's College London Chamber Orchestra and KCL Concert Orchestra.[314]

Founded in 1945, the Choir of King's College London, one of the most acclaimed university choirs in England,[315][316] consists of around 30 choral scholars.[317] The choir regularly broadcasts on BBC Radio 3 and Radio 4 and has made recordings mainly focus on 16th-century English and Spanish repertoire.[317]

All the King's Men is an all-male a cappella ensemble from King's College London. Founded in 2009, it become the first group outside of Oxford and Cambridge to win The Voice Festival UK in 2012.[318][319][better source needed]

American rock band Foo Fighters played their first UK gig at King's College London Students Union in 1995.[320] Pop singer Taylor Swift played her first UK gig at the Strand Campus in 2008.[321]