La Guerra del Yom Kippur , también conocida como la Guerra del Ramadán , la Guerra de Octubre , [70] la Guerra Árabe-Israelí de 1973 o la Cuarta Guerra Árabe-Israelí , se libró del 6 al 25 de octubre de 1973 entre Israel y una coalición de estados árabes liderada por Egipto y Siria . La mayor parte de los combates ocurrieron en la península del Sinaí y los Altos del Golán , territorios ocupados por Israel en 1967. También hubo algunos combates en Egipto y el norte de Israel . [71] [72] [ página requerida ] Egipto pretendía asegurar un punto de apoyo en la orilla oriental del Canal de Suez y utilizarlo para negociar la devolución de la península del Sinaí . [73]

La guerra comenzó el 6 de octubre de 1973, cuando la coalición árabe lanzó un ataque sorpresa contra Israel durante el día sagrado judío de Yom Kippur , que coincidió con el décimo día del Ramadán . [74] Estados Unidos y la Unión Soviética se involucraron en esfuerzos masivos de reabastecimiento para sus aliados (Israel y los estados árabes, respectivamente), [75] [76] [77] lo que aumentó las tensiones entre las dos superpotencias. [78]

Las fuerzas egipcias y sirias cruzaron sus respectivas líneas de alto el fuego con Israel, avanzando hacia el Sinaí y los Altos del Golán. Las fuerzas egipcias cruzaron el Canal de Suez en la Operación Badr y avanzaron hacia el Sinaí, mientras que las fuerzas sirias ganaron territorio en los Altos del Golán. Después de tres días, Israel detuvo el avance egipcio y rechazó a los sirios. Israel luego lanzó una contraofensiva en Siria, bombardeando las afueras de Damasco . Las fuerzas egipcias intentaron avanzar más hacia el Sinaí, pero fueron rechazadas, y las fuerzas israelíes cruzaron el Canal de Suez, avanzando hacia la Ciudad de Suez. [79] [80] El 22 de octubre, un alto el fuego mediado por la ONU se rompió, y ambas partes se acusaron mutuamente de violaciones. Para el 24 de octubre, Israel había rodeado al Tercer Ejército egipcio y la Ciudad de Suez, acercándose a 100 kilómetros (62 millas) de El Cairo. Egipto repelió con éxito nuevos avances israelíes en las batallas de Ismailia y Suez . Se impuso un segundo alto el fuego el 25 de octubre, poniendo fin oficialmente a la guerra.

La Guerra de Yom Kippur tuvo consecuencias significativas. El mundo árabe, humillado por la derrota de 1967, se sintió psicológicamente reivindicado por sus primeros éxitos en 1973. Mientras tanto, Israel, a pesar de los logros en el campo de batalla, reconoció que el futuro dominio militar era incierto. Estos cambios contribuyeron al proceso de paz entre israelíes y palestinos , que condujo a los Acuerdos de Camp David de 1978 , cuando Israel devolvió la península del Sinaí a Egipto, y al tratado de paz entre Egipto e Israel , la primera vez que un país árabe reconoció a Israel . Egipto se alejó de la Unión Soviética y finalmente abandonó el Bloque del Este .

La guerra fue parte del conflicto árabe-israelí , una disputa en curso que ha incluido muchas batallas y guerras desde la fundación del Estado de Israel en 1948. Durante la Guerra de los Seis Días de 1967, Israel había capturado la península del Sinaí de Egipto, aproximadamente la mitad de los Altos del Golán de Siria y los territorios de Cisjordania que habían estado en poder de Jordania desde 1948. [ 81]

El 19 de junio de 1967, poco después de la Guerra de los Seis Días, el gobierno israelí votó a favor de devolver el Sinaí a Egipto y los Altos del Golán a Siria a cambio de un acuerdo de paz permanente y la desmilitarización de los territorios devueltos. [82] [83] [84] Esta decisión no se hizo pública en ese momento, ni se comunicó a ningún estado árabe. El ministro de Asuntos Exteriores israelí, Abba Eban, ha dicho que se había comunicado, pero no parece haber ninguna prueba sólida que corrobore su afirmación; Israel no hizo ninguna propuesta formal de paz, ni directa ni indirectamente. [85] A los estadounidenses, que fueron informados por Eban de la decisión del Gabinete, no se les pidió que la comunicaran a El Cairo y Damasco como propuestas de paz oficiales, ni se les dio indicaciones de que Israel esperaba una respuesta. [86] [87] Eban rechazó la perspectiva de una paz mediada, insistiendo en la necesidad de negociaciones directas con los gobiernos árabes. [88]

La posición árabe, tal como se manifestó en septiembre de 1967 en la Cumbre Árabe de Jartum , fue la de rechazar cualquier acuerdo pacífico con el Estado de Israel. Los ocho Estados participantes —Egipto, Siria, Jordania, Líbano, Irak, Argelia, Kuwait y Sudán— aprobaron una resolución que más tarde se conocería como los “tres noes”: no habría paz, ni reconocimiento, ni negociación con Israel. Antes de eso, el rey Hussein de Jordania había declarado que no podía descartar la posibilidad de una “paz real y permanente” entre Israel y los Estados árabes. [89]

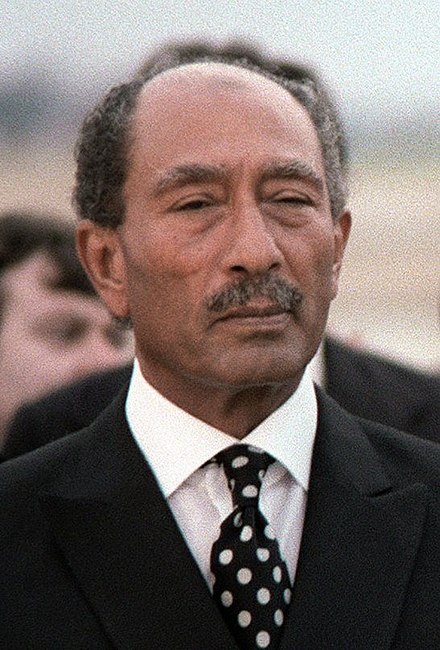

Las hostilidades armadas continuaron en una escala limitada después de la Guerra de los Seis Días y se intensificaron hasta convertirse en la Guerra de Desgaste , un intento de desgastar la posición israelí mediante una presión a largo plazo. [90] En diciembre de 1970, el presidente egipcio Anwar Sadat había señalado en una entrevista con The New York Times que, a cambio de una retirada total de la península del Sinaí, estaba dispuesto "a reconocer los derechos de Israel como un estado independiente según lo definido por el Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas ". [91] El 4 de febrero de 1971, Sadat pronunció un discurso ante la Asamblea Nacional egipcia en el que esbozó una propuesta según la cual Israel se retiraría del Canal de Suez y de la península del Sinaí junto con otros territorios árabes ocupados. [92]

Cuatro días después, el 8 de febrero de 1971, el diplomático sueco Gunnar Jarring propuso una iniciativa similar. Egipto respondió aceptando gran parte de las propuestas de Jarring, aunque difería en varios temas, por ejemplo en lo que respecta a la Franja de Gaza , y expresó su voluntad de alcanzar un acuerdo si también aplicaba las disposiciones de la Resolución 242 del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas . Esta fue la primera vez que un gobierno árabe había declarado públicamente su disposición a firmar un acuerdo de paz con Israel. [91]

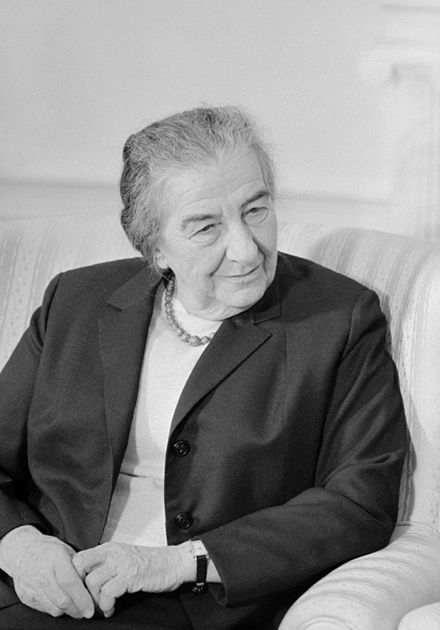

La primera ministra israelí, Golda Meir, reaccionó a la propuesta formando un comité para examinarla y examinar posibles concesiones. Cuando el comité concluyó por unanimidad que los intereses de Israel se verían favorecidos por una retirada total a las líneas internacionalmente reconocidas que dividen a Israel de Egipto y Siria, la devolución de la Franja de Gaza y, según la opinión mayoritaria, la devolución de la mayor parte de Cisjordania y Jerusalén Oriental, Meir se enfadó y archivó el documento. [93]

Estados Unidos se enfureció por la fría respuesta israelí a la propuesta de Egipto, y el secretario de Estado adjunto para Asuntos del Cercano Oriente, Joseph Sisco, informó al embajador israelí Yitzhak Rabin que "Israel sería considerado responsable de rechazar la mejor oportunidad de alcanzar la paz desde la creación del Estado". Israel respondió al plan de Jarring el 26 de febrero describiendo su disposición a hacer algún tipo de retirada, al tiempo que declaraba que no tenía intención de volver a las líneas anteriores al 5 de junio de 1967. [ 94] Al explicar la respuesta, Eban dijo al Knesset que las líneas anteriores al 5 de junio de 1967 "no pueden asegurar a Israel contra la agresión". [95] Jarring estaba decepcionado y culpó a Israel por negarse a aceptar una retirada completa de la península del Sinaí. [94]

Estados Unidos consideraba a Israel un aliado en la Guerra Fría y había estado suministrando suministros al ejército israelí desde los años 1960. El asesor de seguridad nacional estadounidense, Henry Kissinger, creía que el equilibrio de poder regional dependía del mantenimiento del dominio militar de Israel sobre los países árabes y que una victoria árabe en la región fortalecería la influencia soviética. La posición de Gran Bretaña, por otra parte, era que la guerra entre árabes e israelíes sólo podría evitarse mediante la aplicación de la Resolución 242 del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas y el retorno a las fronteras anteriores a 1967. [96]

Sadat también tenía importantes preocupaciones internas que lo impulsaban a querer la guerra. "Los tres años desde que Sadat asumió el poder... fueron los más desmoralizadores en la historia de Egipto... Una economía desecada se sumó al desaliento de la nación. La guerra era una opción desesperada". [97] Casi un año antes de la guerra, en una reunión el 24 de octubre de 1972, con su Consejo Supremo de las Fuerzas Armadas , Sadat declaró su intención de ir a la guerra con Israel incluso sin el apoyo soviético adecuado. [98]

En febrero de 1973, Sadat hizo una propuesta final de paz que habría incluido la retirada israelí de la península del Sinaí, que comunicó a Kissinger a través de su asesor Mohammad Hafez Ismail , y que Kissinger le comunicó a Meir. Meir rechazó la propuesta de paz a pesar de saber que la única alternativa plausible era ir a la guerra con Egipto. [99]

Cuatro meses antes de que estallara la guerra, Kissinger hizo una oferta a Ismail, el emisario de Sadat. Kissinger proponía devolver la península del Sinaí al control egipcio y una retirada israelí de todo el Sinaí, salvo algunos puntos estratégicos. Ismail dijo que volvería con la respuesta de Sadat, pero nunca lo hizo. Sadat ya estaba decidido a ir a la guerra. Sólo una garantía estadounidense de que Estados Unidos cumpliría con todo el programa árabe en un breve período de tiempo podría haber disuadido a Sadat. [100]

Sadat declaró que Egipto estaba dispuesto a "sacrificar un millón de soldados egipcios" para recuperar el territorio perdido. [101] Desde finales de 1972, Egipto inició un esfuerzo concentrado para aumentar sus fuerzas, recibiendo aviones de combate MiG-21 , misiles antiaéreos SA-2 , SA-3 , SA-6 y SA-7 , tanques T-55 y T-62 , armas antitanque RPG-7 y el misil antitanque guiado AT-3 Sagger de la Unión Soviética y mejorando sus tácticas militares, basadas en las doctrinas soviéticas del campo de batalla. Los generales políticos, que habían sido en gran parte responsables de la derrota en 1967, fueron reemplazados por otros competentes. [102]

Los soviéticos no tenían muy buenas perspectivas de que Sadat tuviera éxito en una guerra. Advirtieron que cualquier intento de cruzar el fortificado Canal de Suez provocaría enormes pérdidas. Tanto los soviéticos como los estadounidenses buscaban en ese momento una distensión y no tenían ningún interés en ver desestabilizado Oriente Medio. En una reunión de junio de 1973 con el presidente estadounidense Richard Nixon , el líder soviético Leonid Brezhnev había propuesto que Israel se retirara a su frontera de 1967. Brezhnev dijo que si Israel no lo hacía, "tendremos dificultades para evitar que la situación militar se agrave", una indicación de que la Unión Soviética no había podido frenar los planes de Sadat. [103]

Entre mayo y agosto de 1973, el ejército egipcio realizó ejercicios militares cerca de la frontera, y Ashraf Marwan advirtió erróneamente que Egipto y Siria lanzarían un ataque sorpresa a mediados de mayo. El ejército israelí se movilizó con su Alerta Azul y Blanca, en respuesta tanto a las advertencias como a los ejercicios, a un costo considerable. Estos ejercicios llevaron a algunos israelíes a desestimar los preparativos de guerra reales -y la advertencia de Marwan justo antes de que se lanzara el ataque- como otro ejercicio. [104]

En la semana previa al Yom Kippur , el ejército egipcio realizó un ejercicio de entrenamiento de una semana junto al Canal de Suez. La inteligencia israelí, al detectar grandes movimientos de tropas hacia el canal, los descartó como simples ejercicios de entrenamiento. También se detectaron movimientos de tropas sirias hacia la frontera, así como la cancelación de permisos y un llamado a filas de reservas en el ejército sirio. Estas actividades se consideraron desconcertantes pero no una amenaza porque la inteligencia israelí sugirió que no atacarían sin Egipto, y Egipto no atacaría hasta que llegara el armamento que querían. A pesar de esta creencia, Israel envió refuerzos a los Altos del Golán. Estas fuerzas resultaron fundamentales durante los primeros días de la guerra. [104] : 190–191, 208

Del 27 al 30 de septiembre, el ejército egipcio convocó a dos grupos de reservistas para participar en estos ejercicios. Dos días antes del estallido de la guerra, el 4 de octubre, el mando egipcio anunció públicamente la desmovilización de una parte de los reservistas convocados el 27 de septiembre para calmar las sospechas israelíes. Se desmovilizaron alrededor de 20.000 soldados y, posteriormente, a algunos de ellos se les dio permiso para realizar la Umrah (peregrinación) a La Meca. [105]

Según el general egipcio El-Gamasy, "por iniciativa del personal de operaciones, revisamos la situación sobre el terreno y desarrollamos un marco para la operación ofensiva planificada. Estudiamos las características técnicas del Canal de Suez, el reflujo y el flujo de las mareas, la velocidad de las corrientes y su dirección, las horas de oscuridad y de luz de la luna, las condiciones meteorológicas y las condiciones relacionadas en el Mediterráneo y el mar Rojo". [74] Explicó además diciendo: "El sábado 6 de octubre de 1973 (10 de Ramadán de 1393) fue el día elegido para la opción de septiembre-octubre. Las condiciones para un cruce eran buenas, era un día de ayuno en Israel, y la luna en ese día, 10 de Ramadán, brilló desde el atardecer hasta la medianoche". [74] La guerra coincidió ese año con el mes musulmán de Ramadán , cuando muchos soldados musulmanes ayunan . Por otra parte, el hecho de que el ataque se lanzara en Yom Kippur puede haber ayudado a Israel a reunir más fácilmente reservas desde sus hogares y sinagogas porque los caminos y las líneas de comunicación estaban en gran parte abiertos, lo que facilitó la movilización y el transporte de los militares. [106]

A pesar de negarse a participar, el rey Hussein de Jordania "se había reunido con Sadat y Assad en Alejandría dos semanas antes. Dadas las sospechas mutuas que prevalecían entre los líderes árabes, era poco probable que le hubieran comunicado ningún plan de guerra específico. Pero era probable que Sadat y Assad hubieran planteado la perspectiva de una guerra contra Israel en términos más generales para tantear la posibilidad de que Jordania se uniera a ella". [107]

En la noche del 25 de septiembre, Hussein voló en secreto a Tel Aviv para advertir a Meir de un inminente ataque sirio. “¿Van a ir a la guerra sin los egipcios?”, preguntó la señora Meir. El rey dijo que no lo creía. “Creo que ellos [Egipto] cooperarían”. [ 108 ] Esta advertencia fue ignorada y la inteligencia israelí indicó que Hussein no había dicho nada que no se supiera ya. A lo largo de septiembre, Israel recibió once advertencias de guerra de fuentes bien situadas. Sin embargo, el director general del Mossad , Zvi Zamir, siguió insistiendo en que la guerra no era una opción árabe, incluso después de la advertencia de Hussein. [109] Zamir comentaría más tarde que “simplemente no los creíamos capaces [de la guerra]”. [109]

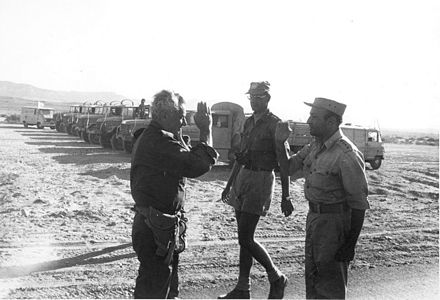

El día antes de la guerra, el general Ariel Sharon recibió fotografías aéreas y otros datos de inteligencia de parte de Yehoshua Saguy , su oficial de inteligencia divisional. Sharon se dio cuenta de que la concentración de fuerzas egipcias a lo largo del canal superaba con creces todo lo observado durante los ejercicios de entrenamiento, y que los egipcios habían acumulado todo su equipo de cruce a lo largo del canal. Entonces llamó al general Shmuel Gonen , quien lo había reemplazado como jefe del Comando Sur, y le expresó su certeza de que la guerra era inminente. [110]

La preocupación de Zamir aumentó el 4 y 5 de octubre, cuando se detectaron más señales de un ataque inminente. Los asesores soviéticos y sus familias abandonaron Egipto y Siria, aviones de transporte que se pensaba que estaban cargados con equipo militar aterrizaron en El Cairo y Damasco , y fotografías aéreas revelaron que las concentraciones egipcias y sirias de tanques, infantería y misiles tierra-aire (SAM) estaban en un nivel sin precedentes. Según documentos desclasificados de la Comisión Agranat , el general de brigada Yisrael Lior (secretario/agregado militar de Meir) afirmó que el Mossad sabía por Marwan que se iba a producir un ataque bajo la apariencia de un ejercicio militar una semana antes de que ocurriera, pero el proceso de pasar la información a la oficina del primer ministro fracasó. [111]

En la noche del 5 al 6 de octubre, Marwan informó incorrectamente a Zamir que un ataque conjunto sirio-egipcio se llevaría a cabo al atardecer. [112] Fue esta advertencia en particular, combinada con una gran cantidad de otras advertencias, lo que finalmente impulsó al Alto Mando israelí a entrar en acción. Apenas horas antes de que comenzara el ataque, se dieron órdenes de un llamamiento parcial a las reservas israelíes . [113]

La primera ministra Golda Meir, el ministro de Defensa Moshe Dayan y el jefe del Estado Mayor David Elazar se reunieron a las 8:05 am de la mañana del Yom Kippur, seis horas antes de que comenzara la guerra. [114] Elazar propuso una movilización de toda la fuerza aérea y cuatro divisiones blindadas, o entre 100.000 y 120.000 tropas, mientras que Dayan favoreció una movilización de la fuerza aérea y dos divisiones blindadas, o alrededor de 70.000 tropas. Meir eligió la propuesta de Elazar. [115] Elazar argumentó a favor de un ataque preventivo contra los aeródromos sirios al mediodía, los misiles sirios a las 3:00 pm y las fuerzas terrestres sirias a las 5:00 pm:

Cuando terminaron las presentaciones, la primera ministra dudó un momento, pero luego tomó una decisión clara: no habría ningún ataque preventivo. Israel podría necesitar pronto la ayuda estadounidense y era imperativo que no se le culpara de iniciar la guerra. "Si atacamos primero, no recibiremos ayuda de nadie", dijo. [114]

Antes de la guerra, Kissinger y Nixon advirtieron constantemente a Meir que no debía ser responsable de iniciar una guerra en Oriente Medio, [116] y el 6 de octubre de 1973, Kissinger envió otro despacho desaconsejando un ataque preventivo. [117] [118] Israel dependía totalmente de los Estados Unidos para el reabastecimiento militar y era sensible a cualquier cosa que pudiera poner en peligro esa relación. A las 10:15 am, Meir se reunió con el embajador estadounidense Kenneth Keating para informarle que Israel no tenía la intención de iniciar una guerra preventivamente y pidió que los esfuerzos estadounidenses se dirigieran a prevenir la guerra. [78] [119]

Kissinger instó a los soviéticos a utilizar su influencia para impedir la guerra, se puso en contacto con Egipto para comunicarle a Israel el mensaje de no tomar medidas preventivas y envió mensajes a otros gobiernos árabes para conseguir su ayuda en favor de la moderación. Estos últimos esfuerzos fueron inútiles. [120] Según Kissinger, si Israel hubiera atacado primero, no habría recibido "ni un clavo". [121] [122]

Los egipcios se habían preparado para un asalto a través del canal y desplegaron cinco divisiones con un total de 100.000 soldados, 1.350 tanques y 2.000 cañones y morteros pesados para el ataque. Frente a ellos estaban 450 soldados de la Brigada de Jerusalén , distribuidos en 16 fuertes a lo largo del canal. Había 290 tanques israelíes en todo el Sinaí, divididos en tres brigadas blindadas, [123] de las cuales sólo una estaba desplegada cerca del canal cuando comenzaron las hostilidades. [124]

El 6 de octubre se establecieron grandes cabezas de puente en la orilla este. Las fuerzas blindadas israelíes lanzaron contraataques del 6 al 8 de octubre, pero a menudo fueron fragmentados y no contaban con el apoyo adecuado y fueron rechazados principalmente por los egipcios que utilizaban misiles antitanque portátiles. Entre el 9 y el 12 de octubre, la respuesta estadounidense fue un llamamiento a un alto el fuego en el lugar. [125] Las unidades egipcias generalmente no avanzaban más allá de una franja poco profunda por miedo a perder la protección de sus baterías SAM, que estaban situadas en la orilla oeste del canal. En la Guerra de los Seis Días, la Fuerza Aérea israelí había bombardeado a los indefensos ejércitos árabes; esta vez, Egipto había fortificado fuertemente su lado de las líneas de alto el fuego con baterías SAM proporcionadas por la Unión Soviética. [126] [127]

El 9 de octubre, las FDI decidieron concentrar sus reservas y aumentar sus suministros mientras los egipcios permanecían a la defensiva estratégica. Nixon y Kissinger se abstuvieron de reabastecer a gran escala armas a Israel. A falta de suministros, el gobierno israelí aceptó a regañadientes un alto el fuego que entró en vigor el 12 de octubre, pero Sadat se negó a hacerlo. [128] Los soviéticos iniciaron un puente aéreo de armas a Siria y Egipto. El interés global de Estados Unidos era demostrar que las armas soviéticas no podían dictar el resultado de la lucha, abasteciendo a Israel. Con un puente aéreo en pleno apogeo, Washington estaba dispuesto a esperar hasta que el éxito israelí en el campo de batalla pudiera persuadir a los árabes y a los soviéticos de poner fin a la lucha. [129]

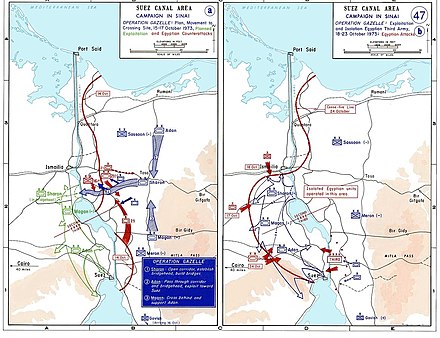

Los israelíes decidieron contraatacar cuando los blindados egipcios intentaron expandir la cabeza de puente más allá del paraguas protector de los misiles antiaéreos. La respuesta, llamada en código Operación Gazelle , se lanzó el 15 de octubre. Las fuerzas de las FDI encabezadas por la división de Ariel Sharon atravesaron el corredor de Tasa y cruzaron el Canal de Suez al norte del Gran Lago Amargo . Después de intensos combates, las FDI avanzaron hacia El Cairo y avanzaron hacia el sur por la orilla este del Gran Lago Amargo y en la extensión sur del canal hasta el puerto de Suez . [130] El avance israelí hacia El Cairo se detuvo con un nuevo alto el fuego el 24 de octubre. [ cita requerida ]

Anticipándose a un rápido contraataque blindado israelí con tres divisiones blindadas, [131] los egipcios habían armado su fuerza de asalto con un gran número de armas antitanque portátiles : granadas propulsadas por cohetes y los menos numerosos pero más avanzados misiles guiados Sagger , que resultaron devastadores para los primeros contraataques blindados israelíes. Cada una de las cinco divisiones de infantería que iban a cruzar el canal había sido equipada con cohetes RPG-7 y granadas RPG-43 y reforzada con un batallón de misiles guiados antitanque, ya que no tendrían ningún apoyo blindado durante casi 12 horas. [132] Además, los egipcios habían construido rampas separadas en los puntos de cruce, que alcanzaban una altura de hasta 21 metros (69 pies) para contrarrestar el muro de arena israelí, proporcionar fuego de cobertura para la infantería atacante y contrarrestar los primeros contraataques blindados israelíes. [133]

El ejército egipcio se esforzó mucho por encontrar una forma rápida y eficaz de abrir una brecha en las defensas israelíes . Los israelíes habían construido grandes muros de arena de 18 metros de alto con una pendiente de 60 grados y reforzados con hormigón en la línea de flotación. Los ingenieros egipcios experimentaron inicialmente con cargas explosivas y excavadoras para despejar los obstáculos, antes de que un oficial subalterno propusiera utilizar cañones de agua a alta presión. La idea se puso a prueba y se comprobó que era acertada, y se importaron varios cañones de agua a alta presión de Gran Bretaña y Alemania del Este. Los cañones de agua abrieron una brecha en los muros de arena de manera eficaz utilizando agua del canal. [134]

A las 14:00 horas del 6 de octubre, comenzó la Operación Badr con un gran ataque aéreo. Más de 200 aviones egipcios llevaron a cabo ataques simultáneos contra tres bases aéreas, baterías de misiles Hawk , tres centros de mando, posiciones de artillería y varias instalaciones de radar. [135] Los aeródromos de Refidim y Bir Tamada quedaron temporalmente fuera de servicio y se infligieron daños a una batería Hawk en Ophir. El asalto aéreo se acompañó de un bombardeo de más de 2.000 piezas de artillería durante un período de 53 minutos contra la línea Bar Lev y los puestos de mando y bases de concentración de la retaguardia. [136]

El autor Andrew McGregor afirmó que el éxito del primer ataque anuló la necesidad de un segundo ataque planeado. [137] [138] [139] Egipto reconoció la pérdida de cinco aviones durante el ataque. Kenneth Pollack escribió que 18 aviones egipcios fueron derribados y que estas pérdidas provocaron la cancelación de la segunda oleada planificada. [140] En un enfrentamiento notable durante este período, un par de F-4E Phantoms israelíes desafiaron a 28 MiG egipcios sobre Sharm el-Sheikh y en media hora, derribaron siete u ocho MiG sin pérdidas. [141] [142] Uno de los pilotos egipcios muertos fue el capitán Atef Sadat , medio hermano del presidente Sadat. [143]

Simultáneamente, 14 bombarderos egipcios Tupolev Tu-16 atacaron objetivos israelíes en el Sinaí con misiles Kelt , mientras que otros dos Tupolev egipcios dispararon dos misiles Kelt contra una estación de radar en el centro de Israel. [141] Un misil fue derribado por un caza israelí Mirage que patrullaba, y el segundo cayó al mar. El ataque fue un intento de advertir a Israel de que Egipto podría tomar represalias si bombardeaba objetivos en las profundidades del territorio egipcio. [144]

Al amparo del bombardeo de artillería inicial, la fuerza de asalto egipcia de 32.000 infantes comenzó a cruzar el canal en doce oleadas en cinco zonas de cruce separadas, desde las 14:05 hasta las 17:30, en lo que se conoció como El Cruce . [145] Los egipcios impidieron que las fuerzas israelíes reforzaran la Línea Bar Lev y procedieron a atacar las fortificaciones israelíes. Mientras tanto, los ingenieros cruzaron para abrir una brecha en el muro de arena. [146] [147] La Fuerza Aérea israelí llevó a cabo operaciones de interdicción aérea para tratar de evitar que se erigieran los puentes, pero sufrió pérdidas por parte de las baterías SAM egipcias. Los ataques aéreos fueron ineficaces en general, ya que el diseño seccional de los puentes permitió reparaciones rápidas cuando eran alcanzados. [148]

A pesar de la feroz resistencia, la brigada de reserva israelí que guarnecía los fuertes de Bar-Lev fue abrumada. Según Shazly, en seis horas, quince puntos fuertes habían sido capturados mientras las fuerzas egipcias avanzaban varios kilómetros hacia el Sinaí. El relato de Shazly fue cuestionado por Kenneth Pollack, quien señaló que en su mayor parte, los fuertes solo cayeron ante repetidos asaltos de fuerzas superiores o asedios prolongados durante muchos días. [149] La fortificación más septentrional de la Línea Bar Lev, cuyo nombre en código era " Fuerte Budapest ", resistió repetidos asaltos y permaneció en manos israelíes durante toda la guerra. Una vez que se colocaron los puentes, la infantería adicional con las armas antitanque portátiles y sin retroceso restantes comenzó a cruzar el canal, mientras que los primeros tanques egipcios comenzaron a cruzar a las 20:30. [150]

Los egipcios también intentaron desembarcar varias unidades de comandos transportadas por helicópteros en varias zonas del Sinaí para obstaculizar la llegada de las reservas israelíes. Este intento resultó desastroso, ya que los israelíes derribaron hasta 20 helicópteros, lo que provocó numerosas bajas. [151] [152] El mayor general israelí (en reserva) Chaim Herzog estimó que las pérdidas de helicópteros egipcios ascendieron a 14. [153] Otras fuentes afirman que "varios" helicópteros fueron derribados con "pérdida total de vidas" y que los pocos comandos que lograron pasar fueron ineficaces y no representaron más que una "molestia". [154] Kenneth Pollack afirmó que, a pesar de sus grandes pérdidas, los comandos egipcios lucharon excepcionalmente duro y crearon un pánico considerable, lo que llevó a los israelíes a tomar precauciones que obstaculizaron su capacidad de concentrarse en detener el asalto a través del canal. [155]

Las fuerzas egipcias avanzaron aproximadamente de 4 a 5 kilómetros ( 2+1 ⁄ 2 a 3 millas) en el desierto del Sinaí con dos ejércitos (ambos del tamaño de un cuerpo de ejército según los estándares occidentales, incluida la 2.ª División de Infantería en el Segundo Ejército del norte). A la mañana siguiente, unos 850 tanques habían cruzado el canal. [136] En su relato de la guerra, Saad El Shazly señaló que para la mañana del 7 de octubre, los egipcios habían perdido 280 soldados y 20 tanques, aunque este relato es discutido. [156] [157]

La mayoría de los soldados israelíes que defendían la Línea Bar Lev resultaron heridos y unos 200 fueron hechos prisioneros. [42] [158] [159] En los días siguientes, algunos defensores de la Línea Bar Lev lograron romper el cerco egipcio y regresar a sus líneas o fueron rescatados durante posteriores contraataques israelíes. Durante los días siguientes, la IAF desempeñó un papel mínimo en los combates, en gran medida porque era necesaria para hacer frente al ataque sirio simultáneo, y en última instancia más amenazador, en los Altos del Golán. [160]

Las fuerzas egipcias consolidaron entonces sus posiciones iniciales. El 7 de octubre, las cabezas de puente se ampliaron otros 4 km ( 2 millas) .+1 ⁄ 2 milla), al mismo tiempo que rechazaba los contraataques israelíes. En el norte, la 18. a División egipcia atacó la ciudad de El-Qantarah el-Sharqiyya , enfrentándose a las fuerzas israelíes en la ciudad y sus alrededores. La lucha allí se llevó a cabo a corta distancia, y a veces fue cuerpo a cuerpo. Los egipcios se vieron obligados a despejar la ciudad edificio por edificio. Al anochecer, la mayor parte de la ciudad estaba en manos egipcias. El-Qantarah estaba completamente despejada a la mañana siguiente. [161]

Mientras tanto, los comandos egipcios lanzados desde el aire el 6 de octubre comenzaron a encontrarse con reservas israelíes a la mañana siguiente. Ambos bandos sufrieron grandes pérdidas, pero los comandos tuvieron éxito en ocasiones en retrasar el movimiento de las reservas israelíes al frente. Estas operaciones especiales a menudo llevaron a confusión y ansiedad entre los comandantes israelíes, quienes elogiaron a los comandos egipcios. [162] [163] Esta opinión fue contradicha por otra fuente que afirmó que pocos comandos lograron alcanzar sus objetivos y que, por lo general, no eran más que una molestia. [164] Según Abraham Rabinovich , solo los comandos cerca de Baluza y los que bloquearon el camino a Fort Budapest tuvieron un éxito mensurable. De los 1.700 comandos egipcios insertados detrás de las líneas israelíes durante la guerra, 740 murieron (muchos en helicópteros derribados) y 330 fueron hechos prisioneros. [165]

El 7 de octubre, David Elazar visitó a Shmuel Gonen, comandante del Comando Sur de Israel —que había asumido el cargo sólo tres meses antes tras el retiro de Ariel Sharon— y se reunió con los comandantes israelíes. Los israelíes planeaban un contraataque cauteloso para el día siguiente por parte de la 162 División Blindada de Avraham Adan . [166] El mismo día, la IAF llevó a cabo la Operación Tagar , con el objetivo de neutralizar las bases de la Fuerza Aérea egipcia y su escudo de defensa antimisiles. [167] [168]

Siete bases aéreas egipcias resultaron dañadas, con la pérdida de dos A-4 Skyhawks y sus pilotos. Otros dos ataques planeados fueron cancelados debido a la creciente necesidad de poder aéreo en el frente sirio. La IAF llevó a cabo ataques aéreos adicionales contra las fuerzas egipcias en la orilla este del canal, supuestamente infligiendo grandes pérdidas. Los aviones israelíes habían llevado a cabo cientos de salidas contra objetivos egipcios al día siguiente, pero el escudo SAM egipcio infligió grandes pérdidas. Las pérdidas de aeronaves de la IAF ascendieron a tres aviones por cada 200 salidas, una tasa insostenible. Los israelíes respondieron ideando rápidamente nuevas tácticas para frustrar las defensas aéreas egipcias. [167] [168]

El 8 de octubre, después de que Elazar se marchara, Gonen cambió los planes basándose en informes de campo excesivamente optimistas. La división de Adan estaba compuesta por tres brigadas con un total de 183 tanques. Una de las brigadas todavía estaba en camino hacia la zona y participaría en el ataque al mediodía, junto con una brigada de infantería mecanizada de apoyo con 44 tanques adicionales. [169] [170] El contraataque israelí se dirigió hacia los puntos fuertes de Bar Lev, frente a la ciudad de Ismailia , contra la infantería egipcia atrincherada. En una serie de ataques mal coordinados que se encontraron con una dura resistencia de los tanques egipcios, la artillería y la infantería armada con cohetes antitanque, los israelíes fueron rechazados con grandes pérdidas. [171]

Un ataque israelí inicial con unos 25 tanques atravesó las primeras tropas egipcias y logró llegar a 800 metros del canal antes de ser atacados con fuego fulminante. Los israelíes perdieron 18 tanques en cuestión de minutos y la mayoría de los comandantes murieron o resultaron heridos. A esto le siguió un segundo ataque por parte de elementos de dos brigadas israelíes, que tenían problemas de comunicación y coordinación. Los egipcios permitieron que los israelíes avanzaran y luego los rodearon en una zona de aniquilación preparada antes de abrir fuego, aniquilando a la mayor parte de la fuerza israelí en 13 minutos. Los egipcios destruyeron más de 50 tanques israelíes y capturaron ocho intactos. [171]

Esa tarde, las fuerzas egipcias avanzaron una vez más para profundizar sus cabezas de puente, y como resultado, los israelíes perdieron varias posiciones estratégicas. Los ataques israelíes posteriores para recuperar el terreno perdido resultaron inútiles. [171] Hacia el anochecer, un contraataque egipcio fue rechazado con la pérdida de 50 tanques egipcios por la 143 División Blindada israelí, que estaba dirigida por Ariel Sharon, quien había sido reinstalado como comandante de división al comienzo de la guerra. Gawrych, citando fuentes egipcias, documentó las pérdidas de tanques egipcios hasta el 13 de octubre en 240. [172]

Según Herzog, el 9 de octubre las líneas del frente se habían estabilizado. Los egipcios no pudieron seguir avanzando y los ataques blindados egipcios del 9 y el 10 de octubre fueron rechazados con grandes pérdidas. [173] Sin embargo, esta afirmación fue cuestionada por Shazly, quien afirmó que los egipcios continuaron avanzando y mejorando sus posiciones hasta bien entrado el 10 de octubre. Señaló un enfrentamiento, en el que participaron elementos de la 1.ª Brigada de Infantería, adscrita a la 19.ª División, que capturaron Aaiún Mousa, al sur de Suez. [174]

La 1.ª Brigada Mecanizada egipcia lanzó un ataque fallido hacia el sur a lo largo del Golfo de Suez en dirección a Ras Sudar . Al abandonar la seguridad del paraguas SAM, la fuerza fue atacada por aviones israelíes y sufrió grandes pérdidas. [174] [175]

Entre el 10 y el 13 de octubre, ambas partes se abstuvieron de realizar acciones a gran escala y la situación se mantuvo relativamente estable. Ambas partes lanzaron ataques a pequeña escala y los egipcios utilizaron helicópteros para desembarcar comandos detrás de las líneas israelíes. Algunos helicópteros egipcios fueron derribados y las fuerzas de comando que lograron aterrizar fueron rápidamente destruidas por las tropas israelíes. En un enfrentamiento clave el 13 de octubre, se detuvo una incursión egipcia particularmente grande y murieron cerca de cien comandos egipcios. [110]

El 14 de octubre se produjo un enfrentamiento conocido ahora como la Batalla del Sinaí . En preparación para el ataque, helicópteros egipcios desplegaban 100 comandos cerca de la carretera lateral para interrumpir la retaguardia israelí. Una unidad de reconocimiento israelí los sometió rápidamente, matando a 60 y tomando numerosos prisioneros. Todavía heridos por las extensas pérdidas que habían sufrido sus comandos el primer día de la guerra, los egipcios no pudieron o no quisieron implementar otras operaciones de comando que se habían planeado en conjunción con el ataque blindado. [176]

El general Shazly se opuso firmemente a cualquier avance hacia el este que dejara a sus tanques sin una cobertura aérea adecuada. Su decisión fue desestimada por el general Ismail y Sadat, cuyos objetivos eran apoderarse de los estratégicos pasos de Mitla y Gidi y del centro neurálgico israelí en Refidim, con lo que esperaban aliviar la presión sobre los sirios (que para entonces estaban a la defensiva) al obligar a Israel a trasladar divisiones del Golán al Sinaí. [177] [178]

Se ordenó al 2.º y 3.º Ejércitos que atacaran hacia el este en seis ataques simultáneos sobre un frente amplio, dejando atrás cinco divisiones de infantería para mantener las cabezas de puente. Las fuerzas atacantes, compuestas por entre 800 y 1.000 tanques, no tendrían cobertura de misiles antiaéreos, por lo que se encargó a la Fuerza Aérea Egipcia (EAF) su defensa contra los ataques aéreos israelíes. Las unidades blindadas y mecanizadas iniciaron el ataque el 14 de octubre con apoyo de artillería. Se enfrentaron a entre 700 y 750 tanques israelíes. [179] [180]

En este caso, el avance blindado egipcio sufrió graves pérdidas. En lugar de concentrar sus fuerzas de maniobra, a excepción del avance del wadi , las unidades egipcias lanzaron ataques frontales contra las defensas israelíes que esperaban. [181] Al menos 250 tanques egipcios y unos 200 vehículos blindados fueron destruidos. [182] [183] [184] [185] Las bajas egipcias superaron las 1.000. [185] Menos de 40 tanques israelíes fueron alcanzados, y todos ellos, menos seis, fueron reparados por equipos de mantenimiento israelíes y devueltos al servicio, [183] mientras que las bajas israelíes ascendieron a 665. [186]

Kenneth Pollack atribuyó el éxito de una incursión de un comando israelí a principios del 14 de octubre contra un sitio de interceptación de señales egipcio en Jebel Ataqah, lo que perturbó gravemente el mando y control egipcios y contribuyó a su desintegración durante el enfrentamiento. [187] La inteligencia israelí también había detectado señales de que los egipcios se estaban preparando para un importante avance blindado ya el 12 de octubre. [188]

En ese momento, el general Sharon abogó por un cruce inmediato en Deversoir, en el extremo norte del Gran Lago Amargo. Antes, el 9 de octubre, una fuerza de reconocimiento adscrita a la Brigada del coronel Amnon Reshef había detectado una brecha entre el Segundo y el Tercer Ejército egipcio en ese sector. [180] Según el general Gamasy, la brecha había sido descubierta por un avión espía estadounidense SR-71 . [189]

Los israelíes siguieron el fallido ataque egipcio del 14 de octubre con un contraataque multidivisional a través de la brecha entre el Segundo y el Tercer Ejército egipcios. La 143.ª División de Sharon, ahora reforzada con una brigada de paracaidistas comandada por el coronel Danny Matt , recibió la tarea de establecer cabezas de puente en las orillas este y oeste del canal. Las 162.ª y 252.ª Divisiones Blindadas, comandadas por los generales Avraham Adan y Kalman Magen, respectivamente, cruzarían entonces la brecha hacia la orilla oeste del canal y girarían hacia el sur, rodeando al Tercer Ejército. [190]

En la noche del 15 de octubre, 750 paracaidistas del coronel Matt cruzaron el canal en botes inflables. [191] Pronto se les unieron tanques, transportados en balsas motorizadas, e infantería adicional. La fuerza no encontró resistencia al principio y se dispersó en grupos de asalto, atacando convoyes de suministros, emplazamientos de misiles antiaéreos, centros logísticos y cualquier otra cosa de valor militar, dando prioridad a los misiles antiaéreos. Los ataques a los emplazamientos de misiles antiaéreos abrieron un agujero en la pantalla antiaérea egipcia y permitieron a la IAF atacar objetivos terrestres egipcios de forma más agresiva. [192]

En la noche del 15 de octubre, 20 tanques israelíes y siete vehículos blindados bajo el mando del coronel Haim Erez cruzaron el canal y penetraron 12 kilómetros (7,5 millas) en Egipto, tomando a los egipcios por sorpresa. Durante las primeras 24 horas, la fuerza de Erez atacó sitios de misiles SAM y columnas militares con impunidad, incluida una importante incursión en bases de misiles egipcias el 16 de octubre, en la que se destruyeron tres bases de misiles egipcias, junto con varios tanques, sin pérdidas israelíes. En la mañana del 17 de octubre, la fuerza fue atacada por la 23.ª Brigada Blindada egipcia, pero logró rechazar el ataque. En ese momento, los sirios ya no representaban una amenaza creíble y los israelíes pudieron trasladar su poder aéreo al sur en apoyo de la ofensiva. [193] La combinación de un paraguas SAM egipcio debilitado y una mayor concentración de cazabombarderos israelíes significó que la IAF fue capaz de aumentar en gran medida las salidas contra objetivos militares egipcios, incluidos convoyes, blindados y aeródromos. Los puentes egipcios que cruzan el canal resultaron dañados por los ataques aéreos y de artillería israelíes. [1]

Los aviones israelíes comenzaron a atacar los emplazamientos de misiles SAM y los radares egipcios, lo que llevó al general Ismail a retirar gran parte del equipo de defensa aérea de los egipcios. Esto, a su vez, dio a la IAF una libertad aún mayor para operar en el espacio aéreo egipcio. Los aviones israelíes también atacaron y destruyeron cables de comunicación subterráneos en Banha , en el delta del Nilo , obligando a los egipcios a transmitir mensajes selectivos por radio, que podían ser interceptados. Aparte de los cables en Banha, Israel se abstuvo de atacar la infraestructura económica y estratégica tras una amenaza egipcia de tomar represalias contra las ciudades israelíes con misiles Scud . Los aviones israelíes bombardearon las baterías egipcias Scud en Port Said varias veces. [1] [194]

La Fuerza Aérea egipcia intentó interceptar las salidas de la IAF y atacar a las fuerzas terrestres israelíes, pero sufrió grandes pérdidas en combates aéreos y por las defensas aéreas israelíes, al tiempo que infligía pérdidas a aviones ligeros. Las batallas aéreas más duras tuvieron lugar sobre el norte del delta del Nilo, donde los israelíes intentaron repetidamente destruir las bases aéreas egipcias. [1] [194] Aunque los israelíes tendían a salir victoriosos en las batallas aéreas, una notable excepción fue la batalla aérea de Mansoura , cuando una incursión israelí contra las bases aéreas egipcias de Tanta y Mansoura fue rechazada por aviones de combate egipcios. [195]

A pesar del éxito que los israelíes estaban teniendo en la orilla oeste, los generales Bar-Lev y Elazar ordenaron a Sharon que se concentrara en asegurar la cabeza de puente en la orilla este. Se le ordenó que despejara los caminos que conducían al canal, así como una posición conocida como la Granja China , justo al norte de Deversoir, el punto de cruce israelí. Sharon se opuso y solicitó permiso para expandir y salir de la cabeza de puente en la orilla oeste, argumentando que tal maniobra causaría el colapso de las fuerzas egipcias en la orilla este. Pero el alto mando israelí insistió, creyendo que hasta que la orilla este estuviera segura, las fuerzas en la orilla oeste podrían ser aisladas. Sharon fue desautorizado por sus superiores y cedió. [196]

El 16 de octubre, envió a la brigada de Amnon Reshef a atacar la granja china. Otras fuerzas de las FDI atacaron a las fuerzas egipcias atrincheradas que dominaban los caminos hacia el canal. Después de tres días de combates encarnizados y cuerpo a cuerpo, los israelíes lograron desalojar a las fuerzas egipcias, numéricamente superiores. Los israelíes perdieron alrededor de 300 muertos, 1.000 heridos y 56 tanques. Los egipcios sufrieron más bajas, incluidos 118 tanques destruidos y 15 capturados. [197] [198] [199] [200] [201] [202]

Mientras tanto, los egipcios no comprendieron la extensión y magnitud del cruce israelí, ni apreciaron su intención y propósito. Esto se debió en parte a los intentos de los comandantes de campo egipcios de ocultar los informes sobre el cruce israelí [203] y en parte a la falsa suposición de que el cruce del canal era simplemente una distracción para una importante ofensiva de las FDI dirigida al flanco derecho del Segundo Ejército. [204] En consecuencia, el 16 de octubre, el general Shazly ordenó a la 21.ª División Blindada que atacara hacia el sur y a la 25.ª Brigada Blindada Independiente equipada con T-62 que atacara hacia el norte en una acción de pinza para eliminar la amenaza percibida para el Segundo Ejército. [205]

Los egipcios no lograron explorar la zona y no sabían que, para entonces, la 162.ª División Blindada de Adán se encontraba en las inmediaciones. Además, la 21.ª y la 25.ª no lograron coordinar sus ataques, lo que permitió que la división del general Adán se enfrentara a cada fuerza por separado. Adán concentró primero su ataque en la 21.ª División Blindada, destruyendo entre 50 y 60 tanques egipcios y obligando al resto a retirarse. Luego giró hacia el sur y tendió una emboscada a la 25.ª Brigada Blindada Independiente, destruyendo 86 de sus 96 tanques y todos sus vehículos blindados, mientras perdía tres tanques. [205]

La artillería egipcia bombardeó el puente israelí sobre el canal en la mañana del 17 de octubre, logrando varios impactos. La Fuerza Aérea egipcia lanzó repetidos ataques, algunos con hasta 20 aviones, para destruir el puente y las balsas, dañando el puente. Los egipcios tuvieron que cerrar sus bases de misiles antiaéreos durante estos ataques, lo que permitió que los cazas israelíes interceptaran a los egipcios. Los egipcios perdieron 16 aviones y siete helicópteros, mientras que los israelíes perdieron seis aviones. [206]

El puente resultó dañado y el cuartel general de los paracaidistas israelíes, que se encontraba cerca del puente, también fue alcanzado; su comandante y su adjunto resultaron heridos. Durante la noche, el puente fue reparado, pero sólo un puñado de fuerzas israelíes logró cruzar. Según Chaim Herzog, los egipcios continuaron atacando la cabeza de puente hasta el alto el fuego, utilizando artillería y morteros para disparar decenas de miles de proyectiles en la zona del cruce. Los aviones egipcios intentaron bombardear el puente todos los días y los helicópteros lanzaron misiones suicidas, intentando lanzar barriles de napalm sobre el puente y la cabeza de puente. [1]

Los puentes sufrieron múltiples daños y tuvieron que ser reparados por la noche. Los ataques causaron numerosas bajas y muchos tanques se hundieron cuando sus balsas fueron alcanzadas. Los comandos egipcios y los hombres rana con apoyo blindado lanzaron un ataque terrestre contra la cabeza de puente, que fue rechazado con la pérdida de 10 tanques. Dos contraataques egipcios posteriores también fueron rechazados. [1]

Tras el fracaso de los contraataques del 17 de octubre, el Estado Mayor egipcio empezó a darse cuenta poco a poco de la magnitud de la ofensiva israelí. A primera hora del 18 de octubre, los soviéticos mostraron a Sadat imágenes satelitales de las fuerzas israelíes que operaban en la ribera occidental. Alarmado, Sadat envió a Shazly al frente para evaluar la situación de primera mano. Ya no confiaba en que sus comandantes de campo le proporcionaran informes precisos. [207] Shazly confirmó que los israelíes tenían al menos una división en la ribera occidental y estaban ampliando su cabeza de puente. Abogó por retirar la mayor parte de los blindados egipcios de la ribera oriental para hacer frente a la creciente amenaza israelí en la ribera occidental. Sadat rechazó esta recomendación de plano e incluso amenazó a Shazly con un tribunal militar. [208] Ahmad Ismail Ali recomendó que Sadat impulsara un alto el fuego para evitar que los israelíes explotaran sus éxitos. [207]

Las fuerzas israelíes ya estaban cruzando el canal en dos puentes, uno de ellos de diseño israelí, y en balsas motorizadas. Los ingenieros israelíes, bajo el mando del general de brigada Dan Even habían trabajado bajo el intenso fuego egipcio para levantar los puentes, y más de 100 personas murieron y cientos más resultaron heridas. [209] El cruce fue difícil debido al fuego de artillería egipcio, aunque a las 4:00 am, dos de las brigadas de Adán estaban en la orilla oeste del canal. En la mañana del 18 de octubre, las fuerzas de Sharon en la orilla oeste lanzaron una ofensiva hacia Ismailia, haciendo retroceder lentamente a la brigada de paracaidistas egipcia que ocupaba la muralla de arena hacia el norte para ampliar la cabeza de puente. [1] [210] Algunas de sus unidades intentaron avanzar hacia el oeste, pero fueron detenidas en el cruce de caminos de Nefalia. La división de Adán avanzó hacia el sur en dirección a la ciudad de Suez, mientras que la división de Magen avanzó hacia el oeste en dirección a El Cairo y hacia el sur en dirección a Adabiya. [211] [212]

El 19 de octubre, una de las brigadas de Sharon continuó empujando a los paracaidistas egipcios hacia el norte, en dirección a Ismailia, hasta que los israelíes estuvieron a 8 o 10 km de la ciudad. Sharon esperaba apoderarse de la ciudad y, de ese modo, cortar las líneas logísticas y de suministro de la mayor parte del Segundo Ejército egipcio. La segunda brigada de Sharon comenzó a cruzar el canal. Los elementos de vanguardia de la brigada se trasladaron al campamento de Abu Sultan, desde donde se trasladaron al norte para tomar Orcha, una base logística egipcia defendida por un batallón de comandos. Los soldados de infantería israelíes despejaron las trincheras y los búnkeres, a menudo enzarzándose en combates cuerpo a cuerpo, mientras los tanques se movían junto a ellos y disparaban contra las secciones de trincheras que se encontraban al frente. La posición fue asegurada antes del anochecer. Más de 300 egipcios murieron y 50 fueron hechos prisioneros, mientras que los israelíes perdieron 16 muertos. [213]

La caída de Orcha provocó el colapso de la línea defensiva egipcia, lo que permitió que más tropas israelíes llegaran a la muralla de arena. Allí pudieron disparar en apoyo de las tropas israelíes que se encontraban frente a Missouri Ridge, una posición ocupada por Egipto en la línea Bar-Lev que podía representar una amenaza para el cruce israelí. El mismo día, los paracaidistas israelíes que participaban en el avance de Sharon hicieron retroceder a los egipcios lo suficiente como para que los puentes israelíes quedaran fuera de la vista de los observadores de la artillería egipcia, aunque los egipcios continuaron bombardeando la zona. [213]

Mientras los israelíes avanzaban hacia Ismailia, los egipcios libraron una batalla que los detuvo, retirándose a posiciones defensivas más al norte, a medida que se veían sometidos a una presión cada vez mayor por la ofensiva terrestre israelí, junto con los ataques aéreos. El 21 de octubre, una de las brigadas de Sharon ocupaba las afueras de la ciudad, pero se enfrentaba a una feroz resistencia de los paracaidistas y comandos egipcios. El mismo día, la última unidad restante de Sharon en la orilla este atacó Missouri Ridge. Shmuel Gonen había exigido que Sharon capturara la posición, y Sharon había ordenado el ataque a regañadientes. El asalto fue precedido por un ataque aéreo que provocó la huida de cientos de soldados egipcios y el atrincheramiento de miles de otros. [214] [215]

Un batallón israelí atacó desde el sur, destruyendo 20 tanques e invadiendo posiciones de infantería antes de ser detenido por misiles Sagger y campos minados. Otro batallón atacó desde el suroeste e infligió fuertes pérdidas a los egipcios, pero su avance se detuvo después de que ocho tanques fueran destruidos. Los soldados israelíes supervivientes lograron contener un asalto de infantería egipcia mientras perdían dos soldados antes de rendirse. Dos de los soldados israelíes lograron esconderse y escapar de vuelta a las líneas israelíes. Los israelíes lograron ocupar un tercio de la cordillera de Missouri. El ministro de Defensa, Moshe Dayan, anuló las órdenes de los superiores de Sharon de continuar el ataque. [214] [215] Sin embargo, los israelíes continuaron expandiendo sus posiciones en la orilla este. Según los israelíes, la cabeza de puente de las FDI tenía 40 km (25 millas) de ancho y 32 km (20 millas) de profundidad a finales del 21 de octubre. [216]

El 22 de octubre, los defensores egipcios de Ismailia ocupaban su última línea de defensa. Alrededor de las 10:00 horas, los israelíes reanudaron el ataque, avanzando hacia Jebel Mariam, Abu 'Atwa y Nefisha. Los paracaidistas en Jebel Mariam se enzarzaron en intensos combates pero, gracias a su posición ventajosa, pudieron repeler el ataque a última hora de la tarde. Mientras tanto, los israelíes concentraron el fuego de artillería y mortero contra las posiciones de Sa'iqa en Abu 'Atwa y Nefisha. Al mediodía, elementos israelíes de avanzada se enfrentaron a una unidad de reconocimiento de Sa'iqa y los israelíes perdieron dos tanques y un semioruga. A la 1:00 horas, una compañía de paracaidistas israelíes atacó Abu 'Atwa sin explorar primero el terreno, y fue emboscada y aniquilada. El ataque terminó después de que los paracaidistas sufrieran más de cincuenta bajas y perdieran cuatro tanques.

Al mismo tiempo, dos compañías de tanques y una infantería mecanizada atacaron Nefisha, apoyadas por un apoyo aéreo cercano. El batallón de comandos egipcios Sa'iqa a cargo de Nefisha logró repeler el ataque después de un combate prolongado y duro que se redujo a distancias muy cortas. Los israelíes perdieron tres tanques, dos semiorugas y una gran cantidad de hombres. Por su parte, los comandos Sa'iqa en Nefisha perdieron 24 muertos, incluidos cuatro oficiales, y 42 heridos, incluidos tres oficiales. Edgar O'Ballance menciona un contraataque de los Sa'iqa que tuvo lugar durante la tarde y que hizo retroceder a algunas de las tropas de Sharon a lo largo del canal Sweetwater. [217] El ataque israelí había sido completamente derrotado. [218] [219]

Las fuerzas israelíes no lograron llegar a Ismailia y rodear la ciudad. El avance israelí sobre Ismailia fue detenido a 10 km (6 mi) al sur de la ciudad. Las FDI no lograron cortar los suministros al Segundo Ejército egipcio ni ocupar Ismailia . Los egipcios registraron una victoria táctica y estratégica en la defensa de Ismailia, deteniendo un cerco de sus grandes fuerzas en la orilla este del Canal de Suez y asegurando que sus líneas de suministro permanecieran abiertas.

En el frente norte, los israelíes también atacaron Port Said, enfrentándose a tropas egipcias y una unidad tunecina de 900 hombres, que libraron una batalla defensiva. [220] El gobierno egipcio afirmó que la ciudad fue bombardeada repetidamente por aviones israelíes y que cientos de civiles murieron o resultaron heridos. [221]

Adán y Magen avanzaron hacia el sur, derrotando decisivamente a los egipcios en una serie de enfrentamientos, aunque a menudo encontraron una determinada resistencia egipcia, y ambos bandos sufrieron grandes bajas. [210] Adán avanzó hacia el área del Canal de Sweetwater, planeando irrumpir en el desierto circundante y atacar las colinas de Geneifa, donde se ubicaban muchos sitios de SAM. Las tres brigadas blindadas de Adán se desplegaron, una avanzando a través de las colinas de Geneifa, otra a lo largo de una carretera paralela al sur de ellas y la tercera avanzando hacia Mina. Las brigadas de Adán encontraron resistencia de las fuerzas egipcias atrincheradas en el cinturón verde del área del Canal de Sweetwater . Las otras brigadas de Adán también fueron detenidas por una línea de campamentos e instalaciones militares egipcias. Adán también fue acosado por la Fuerza Aérea egipcia. [222]

Los israelíes avanzaron lentamente, eludiendo las posiciones egipcias siempre que fue posible. Después de que se les negara el apoyo aéreo debido a la presencia de dos baterías SAM que habían sido traídas al frente, Adan envió dos brigadas para atacarlos. Las brigadas se deslizaron más allá de la infantería egipcia atrincherada, alejándose del cinturón verde por más de 8 km (5 mi), y lucharon contra múltiples contraataques egipcios. Desde una distancia de 4 km ( 2+1 ⁄ 2 mi), bombardearon y destruyeron los SAM, lo que permitió a la IAF proporcionar a Adan apoyo aéreo cercano. [222] Las tropas de Adan avanzaron a través del cinturón verde y se abrieron paso hasta las colinas de Geneifa, enfrentándose con tropas egipcias, kuwaitíes y palestinas dispersas. Los israelíes se enfrentaron con una unidad blindada egipcia en Mitzeneft y destruyeron múltiples sitios SAM. Adan también capturó el aeropuerto Fayid , que posteriormente fue preparado por tripulaciones israelíes para servir como base de suministro y para sacar en avión a los soldados heridos. [223]

Dieciséis kilómetros al oeste del Lago Amargo, la brigada del coronel Natke Nir arrolló a una brigada de artillería egipcia que había estado participando en el bombardeo de la cabeza de puente israelí. Decenas de artilleros egipcios murieron y muchos más fueron hechos prisioneros. Dos soldados israelíes también murieron, incluido el hijo del general Moshe Gidron . Mientras tanto, la división de Magen se movió hacia el oeste y luego hacia el sur, cubriendo el flanco de Adán y finalmente moviéndose al sur de la ciudad de Suez hasta el Golfo de Suez. [224]

El 22 de octubre, el Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas aprobó (por 14 votos a favor y 0 en contra) la Resolución 338 , en la que se pedía un alto el fuego, negociado en gran medida entre los Estados Unidos y la Unión Soviética. En ella se pedía a los beligerantes que cesaran de inmediato toda actividad militar. El alto el fuego debía entrar en vigor 12 horas después, a las 18:52 horas, hora israelí. [225] Como era de noche, era imposible que la vigilancia por satélite determinara dónde estaban las líneas del frente cuando se suponía que terminarían los combates. [226] El Secretario de Estado de los Estados Unidos, Henry Kissinger, le comunicó al Primer Ministro Meir que no se opondría a una acción ofensiva durante la noche anterior a la entrada en vigor del alto el fuego. [227]

Varios minutos antes de que entrara en vigor el alto el fuego, fuerzas egipcias o personal soviético en Egipto dispararon tres misiles Scud contra objetivos israelíes. Este fue el primer uso en combate de misiles Scud. Un Scud tuvo como objetivo el puerto de Arish y dos la cabeza de puente israelí en el Canal de Suez. Uno alcanzó un convoy de suministros israelí y mató a siete soldados. [228] Cuando llegó el momento del alto el fuego, la división de Sharon no había logrado capturar Ismailia ni cortar las líneas de suministro del Segundo Ejército, pero las fuerzas israelíes estaban a solo unos cientos de metros de su objetivo en el sur: la última carretera que unía El Cairo y Suez. [229]

El avance de Adán hacia el sur había dejado a las unidades israelíes y egipcias dispersas por todo el campo de batalla, sin líneas claras entre ellas. Mientras las unidades egipcias e israelíes trataban de reagruparse, estallaron tiroteos regulares. Durante la noche, Elazar informó que los egipcios estaban atacando en un intento de recuperar tierra en varios lugares, y que nueve tanques israelíes habían sido destruidos. Pidió permiso a Dayan para responder a los ataques y Dayan aceptó. Israel luego reanudó su avance hacia el sur. [230]

No está claro qué bando disparó primero [231], pero los comandantes de campo israelíes utilizaron las escaramuzas como justificación para reanudar los ataques. Cuando Sadat protestó por las supuestas violaciones de la tregua por parte de Israel, Israel dijo que las tropas egipcias habían disparado primero. William B. Quandt señaló que, independientemente de quién disparó primero tras el alto el fuego, fue el ejército israelí el que avanzó más allá de las líneas de alto el fuego del 22 de octubre. [232]

El 23 de octubre, Adán reanudó su ataque. [233] Las tropas israelíes terminaron su avance hacia el sur, capturaron la última carretera auxiliar al sur del puerto de Suez y rodearon al Tercer Ejército egipcio al este del Canal de Suez. [234] Los israelíes transportaron entonces enormes cantidades de equipo militar a través del canal, lo que según Egipto violaba el alto el fuego. [231] Los aviones egipcios lanzaron repetidos ataques en apoyo del Tercer Ejército, a veces en grupos de hasta 30 aviones, pero sufrieron graves pérdidas. [10]

Los blindados y paracaidistas israelíes también entraron en Suez en un intento de capturar la ciudad, pero fracasaron tras ser confrontados por soldados egipcios y fuerzas de milicias locales reclutadas apresuradamente. Fueron rodeados y la columna blindada fue emboscada y severamente golpeada, mientras que los paracaidistas fueron objeto de un intenso fuego y muchos de ellos quedaron atrapados dentro de un edificio local. La columna blindada y parte de la fuerza de infantería fueron evacuadas durante el día, mientras que el principal contingente de la fuerza de paracaidistas finalmente logró salir corriendo de la ciudad y regresar a las líneas israelíes. Los israelíes habían perdido 80 muertos y 120 heridos, con mínimas bajas egipcias, sin ninguna ganancia táctica. Israel realizó dos sondas más en Suez, una el 25 y otra el 28, pero ambas fueron rechazadas. [233] [235] [236]

Kissinger se enteró del cerco del Tercer Ejército poco después. [237] Kissinger consideró que la situación presentaba a los Estados Unidos una tremenda oportunidad y que Egipto dependía de los Estados Unidos para impedir que Israel destruyera su ejército atrapado. La posición podría ser aprovechada más tarde para permitir que los Estados Unidos mediaran en la disputa y alejaran a Egipto de la influencia soviética. Como resultado, los Estados Unidos ejercieron una enorme presión sobre los israelíes para que se abstuvieran de destruir el ejército atrapado, incluso amenazando con apoyar una resolución de la ONU que exigiera que los israelíes se retiraran a sus posiciones del 22 de octubre si no permitían que llegaran al ejército suministros no militares. En una llamada telefónica con el embajador israelí Simcha Dinitz , Kissinger le dijo al embajador que la destrucción del Tercer Ejército egipcio "es una opción que no existe". [238]

El gobierno israelí también tenía sus propias motivaciones para no destruir el Tercer Ejército. Entre ellas, la posibilidad de utilizar al Tercer Ejército cercado como moneda de cambio para poner fin al bloqueo egipcio del estrecho de Bab-el-Mandel en el Mar Rojo y negociar una repatriación de los prisioneros de guerra israelíes capturados por Egipto. El estado de agotamiento de las FDI, la posibilidad de que humillar a Egipto destruyendo el Tercer Ejército haría que Sadat se volviera más belicoso y poco dispuesto a cesar las hostilidades, y los intensos temores de Israel de que la Unión Soviética interviniera militarmente en caso de que el Tercer Ejército fuera destruido fueron razones adicionales para que Israel decidiera finalmente no destruirlo. [239]

A pesar de estar rodeado, el Tercer Ejército logró mantener su integridad de combate al este del canal y mantener sus posiciones defensivas, para sorpresa de muchos. [240] Según Trevor N. Dupuy , los israelíes, los soviéticos y los estadounidenses sobreestimaron la vulnerabilidad del Tercer Ejército en ese momento. No estaba al borde del colapso, y escribió que si bien una renovada ofensiva israelí probablemente lo superaría, esto no era una certeza. [241]

David T. Buckwalter coincide en que, a pesar del aislamiento del Tercer Ejército, no estaba claro si los israelíes podrían haber protegido a sus fuerzas en la orilla oeste del canal de un determinado asalto egipcio y aún así mantener una fuerza suficiente a lo largo del resto del frente. [242] Esta evaluación fue cuestionada por Patrick Seale , quien afirmó que el Tercer Ejército estaba "al borde del colapso". [243] La posición de Seale fue apoyada por PR Kumaraswamy, quien escribió que la intensa presión estadounidense impidió que los israelíes aniquilaran al Tercer Ejército varado. [244]

Herzog señaló que, dada la situación desesperada del Tercer Ejército, en términos de verse privado de todo suministro y de la reafirmación de la superioridad aérea israelí, la destrucción del Tercer Ejército era inevitable y podría haberse logrado en un período muy breve. [245] El propio Shazly describió la difícil situación del Tercer Ejército como "desesperada" y clasificó su cerco como una "catástrofe demasiado grande para ocultarla". [246] Señaló además que "el destino del Tercer Ejército egipcio estaba en manos de Israel. Una vez que el Tercer Ejército estuvo rodeado por tropas israelíes, cada pedazo de pan que se enviaba a nuestros hombres se pagaba con el cumplimiento de las demandas israelíes". [247]

Poco antes de que entrara en vigor el alto el fuego, un batallón de tanques israelí avanzó hacia Adabiya y la tomó con el apoyo de la Armada israelí . Se tomaron unos 1.500 prisioneros egipcios y unos cien soldados egipcios se reunieron justo al sur de Adabiya, donde resistieron a los israelíes. Los israelíes también llevaron a cabo su tercera y última incursión en Suez. Consiguieron algunos avances, pero no lograron entrar en el centro de la ciudad. Como resultado, la ciudad quedó dividida por la calle principal, con los egipcios manteniendo el centro de la ciudad y los israelíes controlando las afueras, las instalaciones portuarias y la refinería de petróleo, rodeando de manera efectiva a los defensores egipcios. [1] [248]

En la mañana del 26 de octubre, el Tercer Ejército egipcio violó el alto el fuego al intentar abrirse paso entre las fuerzas israelíes que lo rodeaban. El ataque fue repelido por las fuerzas aéreas y terrestres israelíes. [249] Los egipcios también lograron avances menores en los ataques contra las fuerzas de Sharon en la zona de Ismailia. [1] Los israelíes reaccionaron bombardeando y atacando con artillería objetivos prioritarios en Egipto, incluidos puestos de mando y reservas de agua. [250] El frente estaba más tranquilo en el sector del Segundo Ejército en la zona norte del canal, donde ambos bandos en general respetaron el alto el fuego. [1]

Aunque la mayor parte de los combates más intensos terminaron el 28 de octubre, no se detuvieron hasta el 18 de enero de 1974. El Ministro de Defensa israelí, Moshe Dayan, declaró que:

El alto el fuego existía en el papel, pero el fuego continuo a lo largo del frente no era la única característica de la situación entre el 24 de octubre de 1973 y el 18 de enero de 1974. Este período intermedio también contenía la posibilidad siempre presente de una reanudación de la guerra a gran escala. Había tres variantes sobre cómo podría estallar, dos egipcias y una israelí. Un plan egipcio era atacar a las unidades israelíes al oeste del canal desde la dirección de El Cairo. El otro era cortar la cabeza de puente israelí del canal mediante una unión del Segundo y Tercer Ejércitos en la orilla este. Ambos planes se basaban en bombardeos masivos de artillería sobre las fuerzas israelíes, que no estaban bien fortificadas y que sufrirían grandes bajas. Por lo tanto, se pensó que Israel se retiraría de la orilla oeste, ya que era más sensible al tema de las vidas de los soldados. Egipto, en ese momento, tenía un total de 1.700 tanques de primera línea en ambos lados del frente del canal, 700 en la orilla este y 1.000 en la orilla oeste. También en la orilla oeste, en la segunda línea, había 600 tanques adicionales para la defensa de El Cairo. Tenía unas 2.000 piezas de artillería, unos 500 aviones operativos y al menos 130 baterías de misiles SAM posicionadas alrededor de nuestras fuerzas de modo de negarnos apoyo aéreo. [251]

Las FDI reconocieron la pérdida de 14 soldados durante este período de posguerra. Las pérdidas egipcias fueron mayores, especialmente en el sector controlado por Ariel Sharon, quien ordenó a sus tropas responder con una potencia de fuego masiva a cualquier provocación egipcia. [252] Se produjeron algunas batallas aéreas y los israelíes también derribaron varios helicópteros que intentaban reabastecer al Tercer Ejército. [11]

Al final de la guerra, los israelíes habían avanzado hasta posiciones a unos 101 kilómetros de la capital de Egipto, El Cairo, y ocupaban 1.600 kilómetros cuadrados al oeste del Canal de Suez. [253] También habían cortado la carretera El Cairo-Suez y rodeado la mayor parte del Tercer Ejército de Egipto. Los israelíes también habían tomado muchos prisioneros después de que los soldados egipcios, incluidos muchos oficiales, comenzaran a rendirse en masa hacia el final de la guerra. [254] Los egipcios tenían una estrecha franja en la orilla este del canal, ocupando unos 1.200 kilómetros cuadrados del Sinaí. [254] Una fuente estimó que los egipcios tenían 70.000 hombres, 720 tanques y 994 piezas de artillería en la orilla este del canal. [255] Sin embargo, entre 30.000 y 45.000 de ellos estaban ahora rodeados por los israelíes. [256] [257]

A pesar de los éxitos tácticos de Israel al oeste del canal, el ejército egipcio se reformó y se organizó. En consecuencia, según Gamasy , la posición militar israelí se volvió "debilitada" por diferentes razones:

En primer lugar, Israel contaba ahora con una gran fuerza (unas seis o siete brigadas) en una zona de tierra muy limitada, rodeada por todos lados por barreras naturales o artificiales, o por las fuerzas egipcias. Esto lo colocaba en una posición débil. Además, existían dificultades para abastecer a esta fuerza, para evacuarla, en las largas líneas de comunicación y en el desgaste diario de hombres y equipo. En segundo lugar, para proteger a estas tropas, el mando israelí tuvo que asignar otras fuerzas (cuatro o cinco brigadas) para defender las entradas a la brecha en Deversoir. En tercer lugar, para inmovilizar las cabezas de puente egipcias en el Sinaí, el mando israelí tuvo que asignar diez brigadas para hacer frente a las cabezas de puente del Segundo y Tercer Ejército. Además, se hizo necesario mantener las reservas estratégicas en su máximo estado de alerta. Así pues, Israel se vio obligado a mantener su fuerza armada -y en consecuencia al país- movilizado durante un largo período, al menos hasta que la guerra llegara a su fin, porque el alto el fuego no marcó el fin de la guerra. No hay duda de que esto estaba en total conflicto con sus teorías militares. [258]

Egypt wished to end the war when it realized that the IDF canal crossing offensive could result in a catastrophe.[259] The Egyptians' besieged Third Army could not hold on without supply.[36][247] The Israeli Army advanced to 100 km from Cairo, which worried Egypt.[36] The Israeli army had open terrain and no opposition to advance further to Cairo; had they done so, Sadat's rule might have ended.[260]

In the Golan Heights, the Syrians attacked two Israeli armored brigades, an infantry brigade, two paratrooper battalions and eleven artillery batteries with five divisions (the 7th, 9th and 5th, with the 1st and 3rd in reserve) and 188 batteries. At the onset of the battle, the Israeli brigades of some 3,000 troops, 180 tanks and 60 artillery pieces faced off against three infantry divisions with large armor components comprising 28,000 Syrian troops, 800 tanks and 600 artillery pieces. In addition, the Syrians deployed two armored divisions from the second day onwards.[45][261][262]

To fight the opening phase of a possible battle, before reserves arrived, Israeli high command had, conforming to the original plan, allocated a single armored brigade, the 188th, accepting a disparity in tank numbers of eighteen to one.[263] When the warning by King Hussein of an imminent Syrian attack was conveyed, Elazar at first only assigned two additional tank companies from 7th Armored Brigade: "We'll have one hundred tanks against their eight hundred. That ought to be enough".[264] Eventually, his deputy, Israel Tal, ordered the entire 7th Armored Brigade to be brought up.[265]

Efforts had been made to improve the Israeli defensive position. The "Purple Line" ran along a series of low dormant volcanic cones, "tels", in the north and deep ravines in the south. It was covered by a continuous tank ditch, bunker complexes and dense minefields. Directly west of this line a series of tank ramps were constructed: earthen platforms on which a Centurion tank could position itself with only its upper turret and gun visible, offering a substantial advantage when duelling the fully exposed enemy tanks.[266]

The Syrians began their attack at 14:00 with an airstrike by about a hundred aircraft and a fifty-minute artillery barrage. The two forward infantry brigades, with an organic tank battalion, of each of the three infantry divisions then crossed the cease-fire lines, bypassing United Nations observer posts. They were covered by mobile anti-aircraft batteries, and equipped with bulldozers to fill-in anti-tank ditches, bridge-layer tanks to overcome obstacles and mine-clearance vehicles. These engineering vehicles were priority targets for Israeli tank gunners and took heavy losses, but Syrian infantry at points demolished the tank ditch, allowing their armor to cross.[267]

At 14:45, two hundred men from the Syrian 82nd Paratrooper Battalion descended on foot from Mount Hermon and around 17:00 took the Israeli observation base on the southern slope, with its advanced surveillance equipment. A small force dropped by four helicopters simultaneously placed itself on the access road south of the base.[268] Specialised intelligence personnel were captured. Made to believe that Israel had fallen, they disclosed much sensitive information.[269] A first Israeli attempt on 8 October to retake the base from the south was ambushed and beaten off with heavy losses.[270]

During the afternoon 7th Armored Brigade was still kept in reserve and the 188th Armored Brigade held the frontline with only two tank battalions, the 74th in the north and the 53rd in the south.[271] The northern battalion waged an exemplary defensive battle against the forward brigades of the Syrian 7th Infantry Division, destroying fifty-nine Syrian tanks for minimal losses.[272] The southern battalion destroyed a similar number, but facing four Syrian tank battalions from two divisions had a dozen of its own tanks knocked out.[273] At bunker complex 111, opposite Kudne in Syria, the defending company beat off "determined" and "bravely" pressed attacks by the Syrian 9th Infantry Division; by nightfall it was reduced to three tanks, with only sixty-nine anti-tank rounds between them.[274] Further successful resistance by the southern battalion was contingent on reinforcements.[273]

Direct operational command of the Golan had at first been given to the 188 AB commander, Yitzhak Ben-Shoham, who ordered the 7th AB to concentrate at Wasset.[275] The 7th AB commander, Avigdor Ben-Gal, resented obeying an officer of equal rank and went to the Northern Command headquarters at Nafah, announcing he would place his force in the northern sector at the "Quneitra Gap", a pass south of the Hermonit peak and the main access to the Golan Heights from the east. Northern Command was in the process of moving their headquarters to Safed in Galilee and the senior staff officers were absent at this moment, having expected the Syrian attack to start at 18:00. Operations officer Lieutenant-Colonel Uri Simhoni therefore improvised an allocation of the tactical reserves, thereby largely deciding the course of the battle.[276]

The Armored School Centurion Tank Battalion (71st TB) was kept in general reserve. The 77th Tank Battalion of 7th AB was sent to Quneitra. Two companies of the 75th Mechanised Infantry Battalion, arrived in the morning, of the same brigade were sent to the southern sector. Also 82nd TB had to reinforce the south. However, Ben-Gal had split off a company of this battalion to serve as a reserve for his own brigade.[277] Another company, soon after arriving in the south, was ambushed by an infiltrated Syrian commando force armed with Sagger missiles and almost entirely wiped out.[278] As a result, effective reinforcement of the southern Golan sector was limited to just a single tank company.[279]

At 16:00, Yitzhak Hofi, head Northern Command, shortly visited Nafah and split command of the Golan front: the north would be the responsibility of 7th AB, to which 53rd TB would be transferred. Command of 188th AB would be limited to the south, taking over 82nd TB.[280] The first wave of the Syrian offensive had failed to penetrate, but at nightfall a second, larger, wave was launched. For this purpose each of the three infantry divisions, also committing their organic mechanised brigade with forty tanks, had been reinforced by an armored brigade of about ninety tanks. Two of these brigades were to attack the northern sector, four the southern sector.[281]

Over four days of fighting, the 7th Armored Brigade in the north under Avigdor Ben-Gal managed to hold the rocky hill line defending the northern flank of their headquarters in Nafah, inflicting heavy losses on the Syrians. During the night of 6/7 October it beat off an attack of the Syrian 78th Armoured Brigade, attached to the 7th Infantry Division.[283] On 7 October, 7th AB had to send part of its reserves to the collapsing southern sector. Replenishment from the Nafah matériel stock became impossible. Syrian High Command, understanding that forcing the Quneitra Gap would ensure a total victory on the Golan, decided to commit its strategic armored reserves.[284]

During the night of 7/8 October, the independent 81st Armored Brigade, equipped with modern T-62's and part of the presidential guard, attacked but was beaten off.[284] After this fight, the Israeli brigade would refer to the gap as the "Valley of Tears".[285] Syrian Brigadier-General Omar Abrash, commander of the 7th Infantry Division, was killed on 8 October when his command tank was hit as he was preparing an attempt by 121st Mechanised Brigade to bypass the gap through a more southern route.[286]

Having practiced on the Golan Heights numerous times, Israeli gunners made effective use of mobile artillery.[267] During night attacks, however, the Syrian tanks had the advantage of active-illumination infrared night-vision equipment, which was not a standard Israeli equipment. Instead, some Israeli tanks were fitted with large xenon searchlights which were useful in illuminating and locating enemy positions, troops and vehicles. The close distances during night engagements, negated the usual Israeli superiority in long-range duels. 77th Tank Battalion commander Avigdor Kahalani in the Quneitra Gap generally managed to hold a second tank ramp line.[267]