BBC Television Shakespeare es una serie de adaptaciones televisivas británicas de las obras de William Shakespeare , creada por Cedric Messina y emitida por BBC Television . Transmitida en el Reino Unido desde el 3 de diciembre de 1978 hasta el 27 de abril de 1985, la serie abarcó siete temporadas y treinta y siete episodios.

El desarrollo comenzó en 1975, cuando Messina vio que los terrenos del Castillo de Glamis serían un lugar perfecto para una adaptación de Como gustéis de Shakespeare para la serie Obra del mes . Sin embargo, al regresar a Londres, había llegado a imaginar una serie entera dedicada exclusivamente a las obras dramáticas de Shakespeare. Cuando se encontró con una respuesta poco entusiasta de los jefes de departamento de la BBC, Messina pasó por alto los canales habituales y llevó su idea directamente a la cima de la jerarquía de la BBC, que dio luz verde al programa. Experimentando problemas financieros, logísticos y creativos en los primeros días de producción, Messina perseveró y se desempeñó como productor ejecutivo durante dos años. Cuando fue reemplazado por Jonathan Miller al comienzo de la tercera temporada, el programa experimentó una especie de renacimiento creativo a medida que se relajaban las restricciones sobre las interpretaciones de las obras por parte de los directores, una política que continuó bajo Shaun Sutton , quien asumió como productor ejecutivo durante las temporadas cinco, seis y siete. Al final de su recorrido, la serie había demostrado ser un éxito tanto de audiencia como financiero.

Inicialmente, las adaptaciones recibieron críticas generalmente negativas, aunque la recepción mejoró un poco a medida que avanzaba la serie y se permitió a los directores más libertad, lo que llevó a que las interpretaciones se volvieran más atrevidas. Varios episodios ahora se tienen en alta estima, en particular algunas de las obras tradicionalmente menos conocidas y menos representadas. El conjunto completo es una colección popular, y varios episodios representan la única producción no teatral de la obra en particular actualmente disponible en DVD. A partir del 26 de mayo de 2020, las 37 obras están disponibles para transmitir en América del Norte a través de BritBox . [1]

El concepto de la serie se originó en 1975 con Cedric Messina , un productor de la BBC que se especializaba en producciones televisivas de clásicos teatrales, mientras se encontraba en el Castillo de Glamis en Angus , Escocia, filmando una adaptación de El pequeño ministro de JM Barrie para la serie Play of the Month de la BBC . [2] Durante su tiempo en el set, Messina se dio cuenta de que los terrenos del castillo serían una ubicación perfecta para una adaptación de Como gustéis de Shakespeare . Sin embargo, cuando regresó a Londres, su idea había crecido considerablemente y ahora imaginaba una serie completa dedicada exclusivamente a la obra dramática de Shakespeare; una serie que adaptaría las treinta y siete obras de Shakespeare. [3]

Sin embargo, casi inmediatamente después de presentar la idea a sus colegas, Messina comenzó a encontrar problemas. Había anticipado que todos en la BBC estarían entusiasmados con el concepto, pero esto no resultó así. En particular, la división de Drama/Obras de teatro consideró que la serie no podría ser un éxito financiero sin ventas internacionales, lo que no veían como probable. Además, argumentaron que Shakespeare en televisión rara vez funcionaba, y pensaron que simplemente no había necesidad de hacer las treinta y siete obras, ya que muchas eran oscuras y no encontrarían audiencia entre el público en general, incluso en Inglaterra. Decepcionado por su falta de entusiasmo, Messina pasó por encima de los jefes de departamento, enviando su propuesta directamente al Director de Programas, Alasdair Milne y al Director General, Ian Trethowan , a quienes les gustó la idea. [4] Aunque todavía había reservas dentro de la BBC, y aunque la decisión de Messina de pasar por alto la jerarquía aceptada no sería olvidada, con el apoyo de Milne y Trethowan, la serie recibió luz verde, con su abrumador alcance defendido como parte de su atractivo; "Fue un gran proyecto, nadie más podía hacerlo, nadie más lo haría, pero debía hacerse". [5] Varios meses después de la producción, el periodista Henry Fenwick escribió que el proyecto era "gloriosamente británico, gloriosamente BBC". [6]

La BBC había proyectado muchas adaptaciones de Shakespeare antes, y en 1978, las únicas obras que no habían mostrado en adaptaciones hechas específicamente para televisión eran Enrique VIII , Pericles , Timón de Atenas , Tito Andrónico y Los dos hidalgos de Verona . [7] Sin embargo, a pesar de este nivel de experiencia, nunca habían producido nada a la escala de la Serie de Shakespeare . Las producciones shakespearianas hechas exclusivamente para televisión habían comenzado el 5 de febrero de 1937 con la transmisión en vivo del Acto 3, Escena 2 de Como gustéis , dirigida por Robert Atkins y protagonizada por Margaretta Scott como Rosalind e Ion Swinley como Orlando . [8] Más tarde esa noche, se transmitió la escena del cortejo de Enrique V , dirigida por George More O'Ferrall y protagonizada por Henry Oscar como Henry e Yvonne Arnaud como Katherine . [9] O'Ferrall supervisaría numerosas transmisiones de extractos de Shakespeare a lo largo de 1937, incluido el discurso fúnebre de Marco Antonio de Julio César , con Henry Oscar como Antonio (11 de febrero), [10] varias escenas entre Benedicto y Beatriz de Mucho ruido y pocas nueces , con Henry Oscar y Margaretta Scott (también el 11 de febrero), [11] varias escenas entre Macbeth y Lady Macbeth de Macbeth , protagonizada por Laurence Olivier y Judith Anderson (25 de marzo), [12] y una versión muy truncada de Otelo , protagonizada por Baliol Holloway como Otelo , Celia Johnson como Desdemona y DA Clarke-Smith como Yago (14 de diciembre). [13]

Otras producciones de 1937 incluyeron dos proyecciones diferentes de escenas de El sueño de una noche de verano ; una dirigida por Dallas Bower , protagonizada por Patricia Hilliard como Titania y Hay Petrie como Nick Bottom (18 de febrero), [14] la otra un extracto de la producción de Stephen Thomas en Regent's Park , protagonizada por Alexander Knox como Oberon y Thea Holme como Titania, emitida como parte de las celebraciones por el cumpleaños de Shakespeare (23 de abril). [14] 1937 también vio la transmisión de la escena de cortejo de Ricardo III , dirigida por Stephen Thomas, y protagonizada por Ernest Milton como Ricardo y Beatrix Lehmann como Lady Anne (9 de abril). [15] En 1938, tuvo lugar la primera transmisión completa de una obra de Shakespeare; la producción de vestuario moderno de Dallas Bower de Julio César en el Shakespeare Memorial Theatre , protagonizada por DA Clark-Smith como Marco Antonio y Ernest Milton como César (24 de julio). [16] Al año siguiente se produjo la primera producción de largometraje hecha para televisión; La tempestad , también dirigida por Bower y protagonizada por John Abbott como Próspero y Peggy Ashcroft como Miranda (5 de febrero). [13] La gran mayoría de estas transmisiones se emitieron en vivo y terminaron con el inicio de la guerra en 1939. Ninguna de ellas sobrevive ahora.

Después de la guerra, las adaptaciones de Shakespeare se proyectaron con mucha menos frecuencia y tendieron a ser producciones más "significativas" hechas específicamente para televisión. En 1947, por ejemplo, O'Ferrall dirigió una adaptación en dos partes de Hamlet , protagonizada por John Byron como Hamlet , Sebastian Shaw como Claudio y Margaret Rawlings como Gertrude (5 y 15 de diciembre). [17] Otras producciones de posguerra incluyeron Richard II , dirigida por Royston Morley y protagonizada por Alan Wheatley como Richard y Clement McCallin como Bolingbroke (29 de octubre de 1950); [18] Henry V , nuevamente dirigida por Morley y protagonizada por Clement McCallin como Henry y Olaf Pooley como El Delfín (22 de abril de 1951); [19] una producción original del Sunday Night Theatre de La fierecilla domada , dirigida por Desmond Davis y protagonizada por Margaret Johnston como Katherina y Stanley Baker como Petruchio (20 de abril de 1952); [20] una versión televisiva de la producción de la Elizabethan Theatre Company de John Barton de Henry V , protagonizada por Colin George como Henry y Michael David como El Delfín (19 de mayo de 1953); [21] una presentación en vivo del Sunday Night Theatre de la producción musical de Lionel Harris de The Comedy of Errors , protagonizada por David Pool como Antipholus de Éfeso y Paul Hansard como Antipholus de Siracusa (16 de mayo de 1954); [22] y The Life of Henry the Fifth , el programa inaugural de la nueva serie World Theatre de la BBC, dirigida por Peter Dews y protagonizada por John Neville como Henry y John Wood como El Delfín (29 de diciembre de 1957). [19]

También hubo cuatro adaptaciones de Shakespeare hechas para televisión en varias partes durante las décadas de 1950 y 1960; tres específicamente concebidas como producciones de televisión, una una adaptación televisiva de una producción teatral. La primera fue The Life and Death of Sir John Falstaff (1959). Producida y dirigida por Ronald Eyre , y protagonizada por Roger Livesey como Falstaff , la serie tomó todas las escenas de Falstaff de Henriad y las adaptó en siete episodios de treinta minutos. [23] La segunda fue An Age of Kings (1960). Producida por Peter Dews y dirigida por Michael Hayes , el programa comprendía quince episodios de entre sesenta y ochenta minutos cada uno, que adaptaban las ocho obras históricas secuenciales de Shakespeare ( Ricardo II , 1 Enrique IV , 2 Enrique IV , Enrique V , 1 Enrique VI , 2 Enrique VI , 3 Enrique VI y Ricardo III ). [24] [25] La tercera fue The Spread of the Eagle (1963), dirigida y producida por Dews. Con nueve episodios de sesenta minutos, la serie adaptó las obras romanas, en orden cronológico de los eventos de la vida real representados; Coriolano , Julio César y Antonio y Cleopatra . [26] La cuarta serie no fue una producción televisiva original, sino una "reinvención" hecha para televisión de una producción teatral; The Wars of the Roses , que se proyectó en 1965 y 1966. The Wars of the Roses fue una adaptación en tres partes de la primera tetralogía histórica de Shakespeare ( 1 Enrique VI , 2 Enrique VI , 3 Enrique VI y Ricardo III ) que se había presentado con gran éxito crítico y comercial en el Royal Shakespeare Theatre en 1963, adaptada por John Barton y dirigida por Barton y Peter Hall . Al final de su recorrido, la producción se volvió a montar para la televisión, filmada en el escenario real del Royal Shakespeare Theatre, utilizando el mismo decorado que la producción teatral, pero no durante las representaciones en vivo. Dirigida para televisión por Michael Hayes y Robin Midgley , se emitió originalmente en 1965 como una serie de tres partes, tal como se habían representado las obras (las tres partes se llamaron Enrique VI , Eduardo IV y Ricardo III ). Debido a la popularidad de la transmisión de 1965, la serie se volvió a proyectar en 1966, pero las tres obras se dividieron en diez episodios de cincuenta minutos cada uno.[27] [28]

Aunque An Age of Kings , que fue la producción shakespeariana más cara y ambiciosa hasta ese momento, fue un éxito crítico y comercial, The Spread of the Eagle no lo fue, y después, la BBC decidió volver a producciones de menor escala con menos riesgo financiero. [29] En 1964, por ejemplo, proyectaron una actuación en vivo de la producción de Clifford Williams de la Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) de La comedia de las equivocaciones desde el Teatro Aldwych , protagonizada por Ian Richardson como Antífolo de Éfeso y Alec McCowen como Antífolo de Siracusa. [30] 1964 también vio la transmisión de Hamlet en Elsinore , dirigida por Philip Saville y producida por Peter Luke . Protagonizada por Christopher Plummer como Hamlet, Robert Shaw como Claudio y June Tobin como Gertrudis, toda la obra se filmó en locaciones en Helsingør en el verdadero Castillo de Elsinore . [31] En 1970, proyectaron La tragedia de Ricardo II , extraída de la producción de gira de Richard Cottrell , y protagonizada por Ian McKellen como Ricardo y Timothy West como Bolingbroke. [32]

Además, la serie Obra del Mes había proyectado varias adaptaciones de Shakespeare a lo largo de los años: Romeo y Julieta (1967), La tempestad (1968), Julio César (1969), Macbeth (1970), El sueño de una noche de verano (1971), El mercader de Venecia (1972), El rey Lear (1975) y Trabajos de amor perdidos (1975).

El proyecto BBC Television Shakespeare fue el compromiso más ambicioso con Shakespeare jamás realizado por una compañía de producción de cine o televisión. Tan grande era el proyecto que la BBC no podía financiarlo sola, requiriendo un socio norteamericano que pudiera garantizar el acceso al mercado de los Estados Unidos, considerado esencial para que la serie recuperara sus costos. En sus esfuerzos por obtener esta financiación, la BBC tuvo algo de buena suerte inicial. El editor de guiones de Cedric Messina, Alan Shallcross , era primo de Denham Challender, director ejecutivo de la sucursal de Nueva York de Morgan Guaranty Trust . Challender sabía que Morgan estaba buscando financiar un esfuerzo de arte público, y sugirió la serie de Shakespeare a sus superiores. Morgan se puso en contacto con la BBC y rápidamente se llegó a un acuerdo. [5] Sin embargo, Morgan solo estaba dispuesto a invertir alrededor de un tercio de lo que se necesitaba (aproximadamente £ 1,5 millones / $ 3,6 millones). Asegurar el resto de la financiación necesaria le llevó a la BBC considerablemente más tiempo: casi tres años.

Exxon fue el siguiente en invertir, ofreciendo otro tercio del presupuesto en 1976. [33] Al año siguiente, Time Life , el distribuidor estadounidense de la BBC, fue contactado por la Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) sobre una posible inversión en el proyecto. Sin embargo, debido a que CPB utilizó fondos públicos, su interés en la serie llamó la atención de los sindicatos y profesionales del teatro estadounidenses, que se opusieron a la idea de que el dinero estadounidense subvencionara la programación británica. La Federación Estadounidense de Artistas de Televisión y Radio (AFTRA) y la Federación Estadounidense del Trabajo y Congreso de Organizaciones Industriales (AFL-CIO) comenzaron a presionar a CPB para que no invirtiera en la serie. Joseph Papp , director del Festival de Shakespeare de Nueva York , estaba particularmente horrorizado, argumentando que la televisión estadounidense podía hacer todo el canon para la televisión con la misma facilidad que la BBC, e instando públicamente a CPB a no invertir. [34] Sin embargo, antes de que la situación llegara a un punto crítico, se encontró el tercer inversor necesario, Metropolitan Life . [33] Su inversión significó que con los 5,5 millones de dólares invertidos por la BBC, más el dinero de Morgan y Exxon, el proyecto quedó totalmente financiado. [7]

La complejidad de esta financiación se indica en los créditos de apertura generales de la proyección estadounidense de cada episodio: "La serie es posible gracias a subvenciones de Exxon, Metropolitan Life y Morgan Bank. Es una coproducción de BBC-TV y Time/Life, presentada para el Servicio Público de Radiodifusión por WNET /Thirteen, Nueva York". Según Jac Venza , productor ejecutivo de WNET, "fue una de las pocas veces que conseguimos que tres financiadores corporativos independientes aceptaran financiar algo seis años después. Eso fue en sí mismo una especie de hazaña extraordinaria". [35]

Una de las primeras decisiones de Messina con respecto a la serie fue contratar a un asesor literario: el profesor John Wilders del Worcester College de Oxford . Wilders inicialmente quería que los espectáculos funcionaran a partir de textos completamente nuevos reeditados de los diversos cuartos , octavos y folios específicamente para las producciones, pero cuando el tiempo necesario para esto resultó poco práctico, Wilders decidió en cambio utilizar la edición de 1951 de Peter Alexander de las Obras completas como la "biblia" de la serie. [36]

En un principio, Messina imaginó que la serie tendría seis temporadas de seis episodios cada una, con el plan de adaptar las tres obras de Enrique VI en un episodio de dos partes. Sin embargo, esta idea fue rápidamente rechazada, ya que se consideró que era un compromiso inaceptable y, en su lugar, se decidió simplemente tener una temporada con siete episodios. Inicialmente, Messina jugó con la idea de filmar las obras en el orden cronológico de su composición , pero este plan fue abandonado porque se consideró que hacerlo requeriría que la serie comenzara con una serie de obras relativamente poco conocidas, sin mencionar el hecho de que no hay una cronología definitiva. [36] En cambio, Messina, Wilders y Shallcross decidieron que la primera temporada comprendería algunas de las comedias más conocidas ( Mucho ruido y pocas nueces y Como gustéis ) y tragedias ( Romeo y Julieta y Julio César ). Medida por medida fue seleccionada como la obra "oscura" de la temporada, y El rey Ricardo II se incluyó para comenzar la secuencia de ocho partes de obras históricas . Cuando la producción del episodio inaugural, Much Ado About Nothing , fue abandonada después de haber sido filmado, fue reemplazado por The Famous History of the Life of King Henry the Eight como el sexto episodio de la temporada. [36]

Sin embargo, casi inmediatamente, el concepto de la octología histórica se topó con problemas. Messina había querido filmar las ocho obras históricas secuenciales en orden cronológico de los eventos que representaban, con un reparto vinculado y el mismo director para las ocho adaptaciones ( David Giles ), con la secuencia distribuida a lo largo de toda la carrera de seis temporadas. [37] Sin embargo, durante las primeras etapas de planificación de King Richard the Second y The First Part of King Henry the Fourth, el plan para el reparto vinculado se vino abajo, cuando se descubrió que aunque Jon Finch (Henry Bolingbroke en Richard ) podía regresar como Enrique IV, Jeremy Bulloch como Hotspur y David Swift como el conde de Northumberland no podían hacerlo, y los papeles tendrían que ser reeditados, socavando así el concepto de filmar las obras como una secuencia. [38] Finalmente, durante la primera temporada, King Richard the Second , aunque todavía dirigida por Giles, fue tratada como una pieza independiente, mientras que The First Part of King Henry the Fourth , The Second Part of King Henry the Fourth y The Life of Henry the Fift (todas también dirigidas por Giles) fueron tratadas como una trilogía durante la segunda temporada, con un reparto vinculado entre ellas. Además, en un intento de establecer una conexión con Richard de la primera temporada , Jon Finch regresó como Henry IV, y The First Part of King Henry the Fourth se inauguró con el asesinato de Richard de la obra anterior. El segundo conjunto de cuatro obras fue dirigido por Jane Howell como una unidad, con un escenario común y un reparto vinculado, y se emitió durante la quinta temporada.

.jpg/440px-James_Earl_Jones_(8516667383).jpg)

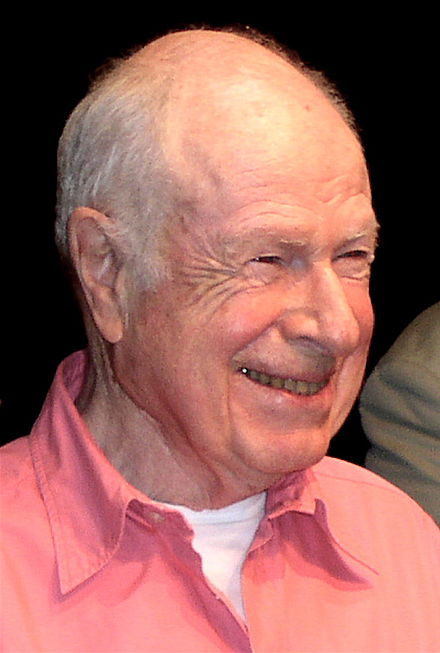

Otra idea inicial, que nunca se materializó, fue el concepto de formar una única compañía de actores de repertorio para representar las treinta y siete obras. Sin embargo, la RSC no estaba especialmente contenta con esta idea, ya que se veía a sí misma como el repertorio nacional. Antes de que el plan pudiera ponerse en práctica, la Asociación de Actores Británicos de Equity bloqueó la propuesta, argumentando que la mayor cantidad posible de sus miembros debería tener la oportunidad de aparecer en la serie. [34] También escribieron en su contrato con la BBC que solo podían ser elegidos actores británicos e irlandeses. Durante la planificación de la segunda temporada, cuando se enteraron de que Messina estaba tratando de elegir a James Earl Jones como Otelo , Equity amenazó con hacer que sus miembros se declararan en huelga, paralizando así la serie. Esto obligó a Messina a abandonar el casting de Jones, y Otelo se retrasó hasta una temporada posterior. [34]

El concepto estético inicial de Messina para la serie era el realismo , especialmente en términos de los decorados, que debían ser lo más representativos posibles. Esto se basaba en lo que Messina sabía de los espectadores de televisión y sus expectativas. Su opinión, apoyada por muchos de sus empleados, era que la mayoría de los espectadores no serían aficionados habituales al teatro que responderían a la estilización o la innovación. Hablando del decorado de Romeo y Julieta , Henry Fenwick señala que

Tanto Rakoff [el director] como Messina estaban convencidos de que la obra debía representarse de la forma más natural posible. "Hay que ver un salón de baile , un balcón, el jardín, la plaza", insistió Messina. "Para captar la atención del público, hay que hacerlo de la forma más realista posible", subraya Rakoff. "Le estás pidiendo al público que haga algo increíble; el medio más real del mundo es la televisión; están viendo las noticias a las nueve en punto y ven sangre real y de repente les decimos: 'Venid a ver nuestra violencia simulada'. He hecho producciones estilizadas antes, y el público tarda muchísimo tiempo en entenderte. Podrías hacer Romeo y Julieta con cortinas blancas o negras, pero creo que alejarías a muchos espectadores potenciales. Me hubiera encantado intentar hacer Romeo al aire libre en algún pueblo de Verona". [39]

De hecho, dos de los episodios de la primera temporada se grabaron en locaciones: Como gustéis, en el castillo de Glamis y sus alrededores, y La famosa historia de la vida del rey Enrique VIII, en tres castillos diferentes de Kent.

Sin embargo, a pesar de la insistencia en el realismo, ambos episodios iniciales, Romeo y Julieta y El rey Ricardo II , presentaban decorados obviamente falsos, recién construidos y destinados a un estudio, que fueron muy criticados por los críticos por no lograr ninguna sensación de realidad vivida; "tal semirealismo desmiente repetidamente la verosimilitud que era su objetivo". [40] Las críticas mordaces de los primeros decorados llevaron a la serie a adoptar un enfoque aún más realista en futuras adaptaciones, especialmente en producciones como La duodécima noche , Las alegres comadres de Windsor y Cimbelino , todas las cuales presentan "una verosimilitud de estudio creíble de exteriores, de lugares que funcionan como si estuvieran filmando en el lugar en lugar de en un escenario o estudio algo realista". [40] Sin embargo, no todos eran fanáticos de la estética realista más extrema. John Wilders, por ejemplo, prefería el "falso realismo" de las primeras obras, que consideraba "mucho más satisfactorias que el trabajo en exteriores porque la artificialidad deliberada de la escenografía funciona en armonía con las convenciones de las obras. Desafortunadamente, puede crear la impresión de que hemos intentado construir decorados realistas pero hemos fracasado por falta de habilidad o dinero". [41] Esta es exactamente la impresión que había creado y fue la razón por la que los episodios posteriores presentaron decorados mucho más elaborados, y por la que el realismo había sido desechado como el enfoque estilístico predominante en la época de Hamlet, príncipe de Dinamarca al final de la segunda temporada. Cuando Jonathan Miller asumió como productor al comienzo de la tercera temporada, el realismo dejó de ser una prioridad.

Antes de la proyección del primer episodio, la publicidad de la serie en el Reino Unido fue extensa, y prácticamente todos los departamentos de la BBC participaron. Una vez que la serie había comenzado, un aspecto importante de la campaña publicitaria consistió en vistas previas de cada episodio para la prensa antes de su transmisión pública, para que pudieran aparecer críticas antes de que se emitiera el episodio; la idea era que las buenas críticas podrían hacer que la gente lo viera que de otra manera no lo haría. Otros "eventos" publicitarios incluyeron una fiesta para celebrar el comienzo de la tercera temporada, en The George Inn, Southwark , cerca del sitio del Globe Theatre , y una fiesta similar al comienzo de la sexta temporada, en el castillo de Glamis, a la que asistieron Ian Hogg , Alan Howard , Joss Ackland , Tyler Butterworth , Wendy Hiller , Patrick Ryecart y Cyril Cusack , todos ellos presentes para las entrevistas de los numerosos periodistas invitados. [42]

Otro aspecto importante de la labor de promoción fue el material educativo complementario. Por ejemplo, la BBC encargó a su división de libros que publicara los guiones de cada episodio, preparados por el editor de guiones Alan Shallcross (temporadas 1 y 2) y David Snodin (temporadas 3 y 4) y editados por John Wilders. Cada publicación incluía una introducción general de Wilders, un ensayo sobre la producción en sí de Henry Fenwick, entrevistas con el reparto y el equipo técnico, fotografías, un glosario y anotaciones sobre las alteraciones textuales de Shallcross y, posteriormente, de Snodin, con explicaciones de por qué se habían realizado determinados cortes.

Además de los guiones comentados publicados, la BBC también produjo dos programas complementarios diseñados para ayudar a los espectadores a involucrarse con las obras en un nivel más académico: la serie de radio Prefaces to Shakespeare y la serie de televisión Shakespeare in Perspective . Prefaces era una serie de programas de treinta minutos centrados en la historia de las representaciones de cada obra, con comentarios proporcionados por un actor que había interpretado la obra en el pasado. El actor discutiría la historia general del escenario, así como sus propias experiencias trabajando en la obra, y cada episodio se emitiría en BBC Radio 4 una a tres noches antes de la proyección del episodio real en BBC 2. [ 43]

El suplemento televisivo, Shakespeare in Perspective , era un programa más educativo en general, con cada episodio de veinticinco minutos que trataba varios aspectos de la producción, presentado por varias figuras conocidas, que, en general, no estaban involucradas en Shakespeare per se . [44] Emitido en BBC 2 la noche anterior a la transmisión del programa en sí, la intención principal de la serie era "ilustrar una nueva audiencia para Shakespeare en televisión, atraer gente a las obras y darles algo de material de fondo. [Los presentadores] resumieron las historias de las obras, proporcionaron un marco histórico, cuando fue posible, y ofrecieron algunos pensamientos originales que podrían intrigar a aquellos que ya estaban familiarizados con el texto". [45] El nivel de erudición se midió deliberadamente para los exámenes de nivel O y A , y los presentadores escribían sus propios guiones. Sin embargo, la serie a menudo tuvo problemas. Para el programa sobre Hamlet, príncipe de Dinamarca , por ejemplo, cuando el equipo apareció para filmar, el presentador simplemente declaró: "Esta es una de las obras más tontas jamás escritas, y no tengo nada que decir al respecto". Esto dio lugar a un programa organizado apresuradamente y presentado por Clive James . [46]

Sin embargo, el mayor problema de Shakespeare en perspectiva , y el que se comentaba con más frecuencia en las reseñas, era que el presentador de cada episodio no había visto la producción sobre la que estaba hablando y, a menudo, había una disparidad entre sus comentarios y la interpretación que ofrecía el espectáculo. Por ejemplo, los comentarios del poeta Stephen Spender sobre El cuento de invierno como una obra de gran belleza que celebra los ciclos de la naturaleza parecían estar en desacuerdo con la producción semiestilizada de un solo escenario de Jane Howell, donde se utilizó un árbol solitario para representar el cambio de estaciones. El ejemplo más comentado de esta disparidad fue en relación con Cymbeline , que fue presentada por el dramaturgo y guionista Dennis Potter . En su reseña para The Observer tanto de la producción como del espectáculo Perspective , Julian Barnes escribió: "Es comprensible que haya varios estadios que separen la mano izquierda de la derecha de la BBC. Sin embargo, sólo en raras ocasiones presenciamos un cameo de incomprensión entre manos como el que ocurrió la semana pasada dentro de su ciclo de Shakespeare: la mano derecha agarrando un martillo y clavando bruscamente la mano izquierda al brazo de la silla". Barnes señala que, claramente, Potter no había visto el espectáculo cuando grabó su comentario. Tenía razón; Potter's Perspective se había grabado antes de que Cymbeline se hubiera filmado. Según Barnes,

Potter fue descubierto por primera vez acechando entre las rocas cubiertas de musgo y las grutas resonantes del Bosque de Dean , un telón de fondo adecuado, explicó, para presentar una obra llena de "los paisajes pétreos y misteriosos tanto de mi propia infancia como de todos nuestros recuerdos plagados de cuentos de hadas ". Nos instó a entrar tranquilamente en el mundo de los sueños: "Regresa con tu mente a las tardes oscuras de la infancia. Tus párpados están caídos [...] la casa cálida y acogedora se está preparando para irse a la deriva, sin anclas, hacia la noche [...] el reino de érase una vez". Megalitos y memoria, helechos y hadas : tal era el mundo de Cymbeline . Elijah Moshinsky , el director, obviamente no se había enterado. Las hadas estaban descartadas; las rocas estaban descartadas; los paisajes pétreos y misteriosos podían ser olvidados. La antigua Gran Bretaña, durante el reinado de César Augusto , se convirtió en una corte pretenciosa del siglo XVII, con guiños a Rembrandt , Van Dyck y (cuando Helen Mirren fue captada con cierta luz y cierto vestido) a Vermeer . El cuento de hadas que el señor Potter había prometido se convirtió en una obra de intriga cortesana y pasión moderna: una especie de recorte de Otelo . [47]

En los EE. UU., la BBC contrató a Stone/Hallinan Associates para manejar la publicidad. Sin embargo, debido a que el programa se transmitió en la televisión pública , muchos periódicos y revistas estadounidenses no lo cubrieron. [48] Para lanzar el programa en los EE. UU., se realizó una recepción en la Casa Blanca , a la que asistió Rosalynn Carter , seguida de un almuerzo en la Biblioteca Folger Shakespeare . El representante principal fue Anthony Quayle , quien había sido elegido como Falstaff para los episodios de la segunda temporada de Enrique IV . También ayudó que, a diferencia de muchos de los otros actores que aparecieron en los primeros episodios, Quayle era muy conocido en los EE. UU. También asistieron Richard Pasco , Celia Johnson, Patrick Ryecart y Helen Mirren. James Earl Jones inicialmente estaba programado para aparecer, en previsión de la producción de la segunda temporada de Otelo , pero en el momento de la recepción, Messina se vio obligada a abandonar su elección. [49] En las semanas previas al estreno, Stone/Hallinan envió dossiers de prensa para cada episodio, mientras que Exxon produjo comerciales de radio y televisión, MetLife celebró jornadas de puertas abiertas sobre Shakespeare en su oficina central y envió carteles y guías para el espectador para cada episodio. [50]

En los EE. UU., WNET planeó una serie de programas de treinta minutos para que actuaran como introducciones generales a cada episodio. Esto creó una especie de circo mediático cuando (medio) en broma le preguntaron a Joseph Papp si estaría interesado en presentarlo. [51] Sin embargo, finalmente abandonaron la idea y simplemente transmitieron los episodios de Shakespeare en perspectiva de la BBC . En términos de publicidad radial, en 1979, National Public Radio (NPR) transmitió Shakespeare Festival ; una serie de óperas y programas musicales basados en las obras de Shakespeare, así como un docudrama de dos horas , William Shakespeare: A Portrait in Sound , escrito y dirigido por William Luce , y protagonizado por Julie Harris y David Warner . También transmitieron una serie de conferencias desde el Lincoln Center , con Samuel Schoenbaum , Maynard Mack y Daniel Seltzer . Además, la estación de NPR WQED-FM transmitió introducciones de media hora a cada obra la semana anterior a la transmisión televisiva del episodio. Sin embargo, cuando los primeros episodios del programa no lograron el tipo de índices de audiencia que se habían esperado inicialmente, la financiación para la publicidad se agotó rápidamente; un programa de variedades de Shakespeare planeado para PBS en 1981, protagonizado por Charlton Heston , Robin Williams , Richard Chamberlain y Chita Rivera , no logró encontrar un patrocinador y fue cancelado. [52] Shakespeare: The Globe and the World de la Biblioteca Folger Shakespeare , una exhibición itinerante multimedia , tuvo más éxito y viajó a ciudades de todo el país durante las dos primeras temporadas del programa. [53]

De la misma forma que los esfuerzos promocionales de la BBC en el Reino Unido se centraron, al menos parcialmente, en la educación, también lo hizo la publicidad en Estados Unidos, donde los patrocinadores gastaron tanto en el material educativo como en la financiación de la serie en sí. La tarea de gestionar el programa de difusión educativa en Estados Unidos se encargó a Tel-Ed, una filial de Stone/Hallinan. Los esfuerzos educativos se centraron en la enseñanza media y secundaria, que es cuando los estudiantes estadounidenses conocen por primera vez a Shakespeare. Tel-Ed tenía un triple objetivo: familiarizar a los estudiantes con más obras (la mayoría de las escuelas enseñaban solo Romeo y Julieta , Julio César y Macbeth ), animar a los estudiantes a disfrutar de Shakespeare y que se enseñara Shakespeare con más frecuencia. El objetivo de Tel-Ed era poner toda la serie a disposición de todas las escuelas secundarias de Estados Unidos. Durante la primera temporada, enviaron 36.000 paquetes educativos a los departamentos de inglés y recibieron 18.000 solicitudes de información adicional. [53] El aspecto educativo de la serie fue considerado un éxito tal que cuando el programa salió del aire en 1985, Morgan Bank continuó con los esfuerzos educativos, creando The Shakespeare Hour en 1986. El concepto del programa era que los episodios de BBC Television Shakespeare se presentarían específicamente como herramientas educativas. Planificada como un programa de tres años con cinco episodios por año durante una temporada de quince semanas, la serie agruparía las obras temáticamente. Walter Matthau fue contratado como presentador, y cada episodio presentó material documental intercalado con extensos clips de las propias producciones de la BBC. También se publicó un libro con la transcripción completa de cada episodio; The Shakespeare Hour: A Companion to the PBS-TV Series , editado por Edward Quinn. En total, la primera temporada costó $650,000, pero todos esperaban que fuera un éxito. Cubriendo el tema del amor, utilizó El sueño de una noche de verano , La duodécima noche , Bien está lo que bien acaba , Medida por medida y El rey Lear . Sin embargo, el programa obtuvo muy malos índices de audiencia y fue cancelado al final de la primera temporada. La segunda temporada estaba programada para cubrir el poder ( El rey Ricardo II , La primera parte del rey Enrique IV , La tragedia de Ricardo III , La fierecilla domada , Macbeth y Julio César ), y la tercera se centraría en la venganza ( El mercader de Venecia , Hamlet, príncipe de Dinamarca , El cuento de invierno , La tempestad y Otelo ).[54]

El alcance de la serie significó que desde el principio, la programación fue una preocupación importante. Todo el mundo sabía que lograr buenos índices de audiencia para treinta y siete episodios a lo largo de seis años no iba a ser fácil, y para garantizar que esto pudiera lograrse, la BBC fue (al principio) rigurosa con la programación del programa. Cada una de las seis temporadas se emitiría en dos secciones: tres emisiones semanales a fines del invierno, seguidas de un breve descanso y luego tres emisiones semanales a principios de la primavera. Esto se hizo para maximizar el marketing en el período previo a la Navidad y luego capitalizar el período tradicionalmente tranquilo a principios de la primavera. [55] La primera temporada siguió este modelo a la perfección, con emisiones en 1978 el 3 de diciembre ( Romeo y Julieta ), el 10 de diciembre ( El rey Ricardo II ) y el 17 de diciembre ( Medida por medida ), y en 1979 el 11 de febrero ( Como gustéis ), el 18 de febrero ( Julio César ) y el 25 de febrero ( La famosa historia de la vida del rey Enrique VIII ). Todos los episodios se emitieron en BBC 2 un domingo, y todos comenzaron a las ocho en punto, con un intervalo de cinco minutos alrededor de las nueve para las noticias de la 2 y un informe meteorológico. La segunda temporada comenzó con el mismo sistema, con producciones en 1979 el 9 de diciembre ( La primera parte del rey Enrique IV ), el 16 de diciembre ( La segunda parte del rey Enrique IV ) y el 23 de diciembre ( La vida de Enrique V ). Sin embargo, el cronograma comenzó a tener problemas. El cuarto episodio, Duodécima noche , se emitió el domingo 6 de enero de 1980, pero el quinto episodio, La tempestad , no se emitió hasta el miércoles 27 de febrero, y el sexto, Hamlet, príncipe de Dinamarca (que se había retrasado debido al horario de Derek Jacobi ) no se emitió hasta el domingo 25 de mayo.

Entrando en la tercera temporada, bajo la producción de Jonathan Miller, la programación, como comentaron muchos críticos en ese momento, parecía nada menos que aleatoria. El episodio uno de la tercera temporada ( La fierecilla domada ) se emitió el miércoles 23 de octubre de 1980. El episodio siguiente ( El mercader de Venecia ) se emitió el miércoles 17 de diciembre, seguido de Todo está bien el domingo 4 de enero de 1981, El cuento de invierno el domingo 8 de febrero, Timón de Atenas el jueves 16 de abril y Antonio y Cleopatra el viernes 8 de mayo. La segunda temporada de Miller como productor (la cuarta temporada de la serie) fue aún más errática, con solo tres episodios apareciendo durante toda la temporada: Otelo el domingo 4 de octubre de 1981, Troilo y Crésida el sábado 7 de noviembre y El sueño de una noche de verano el domingo 13 de diciembre. El siguiente grupo de episodios no se emitió hasta la quinta temporada en septiembre de 1982, bajo la producción de Shaun Sutton . La programación de Sutton, en todo caso, fue incluso más aleatoria que la de Miller; la quinta temporada comenzó con El rey Lear el domingo 19 de septiembre, pero no se siguió hasta Las alegres comadres de Windsor el martes 28 de diciembre. La primera tetralogía histórica regularizó temporalmente la programación y se emitió los domingos sucesivos; 2, 9, 16 y 23 de enero de 1983. La sexta temporada comenzó con Cymbeline el domingo 10 de julio, pero el segundo episodio no siguió hasta el sábado 5 de noviembre ( Macbeth ). La comedia de las equivocaciones se emitió el sábado 24 de diciembre, seguida solo tres días después por Los dos hidalgos de Verona el martes 27 de diciembre, con La tragedia de Coriolano cerrando la temporada el sábado 21 de abril de 1984. La séptima temporada se emitió íntegramente los sábados; La vida y muerte del rey Juan el 24 de noviembre, Pericles, príncipe de Tiro el 8 de diciembre, Mucho ruido y pocas nueces el 22 de diciembre, Trabajos de amor perdidos el 5 de enero de 1985 y, finalmente, Tito Andrónico el 27 de abril.

La programación estadounidense era aún más compleja. En el Reino Unido, cada episodio podía empezar en cualquier momento y durar lo que quisiera sin mayores problemas, porque los programas no se recortan para encajar en los espacios, sino que los espacios se organizan para encajar en los programas. En Estados Unidos, sin embargo, la televisión funcionaba con franjas horarias muy rígidas; un programa no podía durar, digamos, 138 minutos, sino que debía durar 120 o 150 minutos para encajar en el espacio existente. Además, mientras que la BBC incluía un intermedio de cinco minutos aproximadamente a la mitad de cada programa, la PBS tenía que tener un intermedio cada sesenta minutos. Varios de los programas de la primera temporada dejaron "huecos" en los espacios de tiempo estadounidenses de casi veinte minutos, que tenían que llenarse con algo. En las temporadas uno y dos, cualquier hueco significativo al final de un programa se llenaba con música renacentista interpretada por Waverly Consort . Cuando Jonathan Miller asumió como productor al final de la segunda temporada, WNET sugirió algo diferente; Cada episodio debía tener una introducción de dos minutos, seguida de entrevistas con el director y un miembro del elenco al final del episodio, que se editarían para que tuvieran la duración necesaria para llenar los huecos. [56] Sin embargo, al llegar a la quinta temporada, WNET no tenía dinero para grabar más introducciones o entrevistas, y la única alternativa era cortar los episodios para que se ajustaran a los espacios de tiempo, para gran disgusto de la BBC. Las producciones que causaron más problemas fueron la serie Enrique VI / Ricardo III de Jane Howell . Con un total de catorce horas, WNET sintió que emitir los programas en cuatro segmentos consecutivos no funcionaría. Primero, cambiaron el horario para emitir los episodios el domingo por la tarde en lugar de la proyección habitual del lunes por la noche, luego dividieron las tres obras de Enrique VI en dos partes cada una. Finalmente, cortaron un total de 77 minutos de las tres producciones (35 fueron tomados de La tercera parte de Enrique VI solo). Para ayudar a recortar la primera parte de Enrique VI , se eliminaron muchos diálogos iniciales y, en su lugar, se agregó una introducción con voz en off grabada, irónicamente, por James Earl Jones, que informaba a los espectadores de la historia de fondo necesaria. Sin embargo, La tragedia de Ricardo III (la más larga de las cuatro) se emitió como una sola pieza, con solo 3 minutos cortados. [57]

Como los inversores estadounidenses habían invertido tanto dinero en el proyecto, los patrocinadores pudieron incluir en el contrato unas directrices estéticas. Sin embargo, como la mayoría de estas directrices se ajustaban de todos modos a la visión de Messina de la serie ("hacer versiones televisivas sólidas y básicas de las obras de Shakespeare para llegar a una amplia audiencia televisiva y mejorar la enseñanza de Shakespeare"), [58] no crearon grandes problemas. La más importante de estas estipulaciones era que las producciones debían ser interpretaciones "tradicionales" de las obras ambientadas en la época de Shakespeare (1564 a 1616) o en el período de los acontecimientos representados (como la antigua Roma para Julio César o alrededor de 1400 para Ricardo II ). También se impuso una duración máxima de dos horas y media, aunque pronto se descartó cuando quedó claro que las grandes tragedias, en particular, sufrirían si se truncaban demasiado. La solución inicial fue dividir las obras más largas en dos secciones y proyectarlas en noches separadas, pero esta idea también fue descartada y se acordó que, para las obras más importantes, la duración no era una cuestión demasiado importante. [59]

Sin embargo, la restricción relativa a las interpretaciones conservadoras y tradicionales no era negociable. Los financistas estaban preocupados principalmente por los índices de audiencia, y las restricciones funcionaron con ese fin, asegurando que las obras tuvieran "la máxima aceptabilidad para el público más amplio posible". Sin embargo, por más práctica que fuera esta estipulación, tales decisiones "demuestran que se dedicó mucha más atención a los asuntos financieros que a las cuestiones interpretativas o estéticas a la hora de planificar la serie". [60] Sin embargo, el propio Messina no tuvo ningún problema con ninguna de estas restricciones, ya que se ajustaban a su visión inicial: "no hemos hecho nada demasiado sensacionalista en el rodaje, no hay rodajes artificiosos en absoluto. Todas son, a falta de una palabra mejor, producciones sencillas". [61]

Estas restricciones tuvieron un origen práctico, pero pronto tuvieron consecuencias estéticas;

Los patrocinadores simplemente propusieron difundir ampliamente las obras para beneficio cultural y educativo. Esperaban que mucha gente pudiera ver a Shakespeare representado por primera vez en la serie televisada, un punto que Messina enfatizó repetidamente; otros sin duda recitarían las líneas junto con los actores [...] En consecuencia, las expectativas y los criterios de juicio serían virtualmente inexistentes o bastante altos [...] ¿Importaba lo buenas que fueran las producciones siempre que fueran "aceptables" según ciertos estándares -cuota de audiencia, recepción crítica o ventas en el extranjero-? Sin embargo, ser aceptable no siempre es sinónimo de ser bueno, e inicialmente, el objetivo parece haber sido el primero, con algunas incursiones en el segundo. [62]

En parte debido a este credo estético, la serie rápidamente desarrolló una reputación de ser excesivamente convencional. Como resultado, cuando Miller más tarde intentó persuadir a directores célebres como Peter Brook , Ingmar Bergman , William Gaskill y John Dexter para que dirigieran adaptaciones, fracasó. [63] Al revisar las dos primeras temporadas de la serie para Critical Quarterly , en un artículo titulado "BBC Television's Dull Shakespeares", Martin Banham citó un extracto publicitario escrito por Messina en el que afirmó: "no ha habido ningún intento de estilización, no hay trucos; ningún adorno para confundir al estudiante". Banham opinó que algunas de las mejores producciones teatrales recientes han sido extremadamente "efectistas" en el sentido de "aventureras", mientras que los dos primeros episodios de la serie eran simplemente "poco imaginativos" y estaban más preocupados por la "belleza" visual que por la calidad dramática. [64]

A la luz de tales críticas sobre la naturaleza conservadora de las primeras producciones, Jac Venza defendió las restricciones, señalando que la BBC tenía como objetivo hacer programas con una larga vida útil; no eran una compañía de teatro que producía una sola serie de obras para un público ya familiarizado con esas obras, que valoraría la novedad y la innovación. Estaban haciendo adaptaciones televisivas de obras para un público que en su gran mayoría no estaría familiarizado con la mayor parte del material. Venza señaló que muchos de los críticos que atacaron con más vehemencia la naturaleza tradicional y conservadora del programa eran aquellos que eran asistentes habituales al teatro y/o estudiosos de Shakespeare, y que esencialmente estaban pidiendo algo que la BBC nunca tuvo la intención de producir. Querían llegar a una amplia audiencia y hacer que más gente se interesara en Shakespeare y, como tal, la novedad y la experimentación no formaban parte del plan, una decisión que Venza califica de "muy sensata". [65]

Desafortunadamente para todos los involucrados en la serie, la producción tuvo el peor comienzo posible. El episodio inaugural iba a ser Much Ado About Nothing , dirigido por Donald McWhinnie y protagonizado por Penelope Keith y Michael York . [66] El episodio fue filmado (con un costo de £ 250,000), editado e incluso anunciado públicamente como la apertura de la serie antes de que de repente fuera retirado de la programación y reemplazado por Romeo & Juliet (que se suponía que saldría al aire como el segundo episodio). La BBC no dio razones para esta decisión, aunque los informes periodísticos iniciales sugirieron que el episodio no había sido abandonado, simplemente se había pospuesto para nuevas grabaciones, debido al "acento muy marcado" de un actor no especificado y las preocupaciones de que el público estadounidense no pudiera entender el diálogo. [67] Sin embargo, a medida que pasaba el tiempo y no se materializaban nuevas grabaciones, la prensa comenzó a especular que el programa había sido cancelado por completo y que sería reemplazado en una fecha posterior por una adaptación completamente nueva, que de hecho fue lo que sucedió. [68] La prensa también señaló que el hecho de que la producción nunca se exhibiera en Gran Bretaña desmintió cualquier sugerencia de que la causa principal del abandono fuera el acento. De hecho, hay evidencia que sugiere que la gerencia de la BBC simplemente consideró que la producción fue un fracaso. [69] Este problema, que ocurrió al comienzo mismo de la serie, tendría repercusiones duraderas;

La causa real del problema aparentemente se originó en la política interna, una lucha interna centrada en Messina más que en el programa, su director o los actores, una lucha que dejó cicatrices duraderas. Si bien Messina fue el hombre que planificó la serie, parecía que no era el hombre para producirla. Fue parte de demasiadas luchas de poder; demasiados directores no trabajaron para él; procedió con demasiados hábitos de producción tradicionales. La batalla por Much Ado fue en realidad una batalla por el poder y la producción; una vez que Messina perdió y el programa fue cancelado, su mandato como productor se vio comprometido. [70]

Otro de los primeros problemas que tuvo Messina fue que la campaña publicitaria estadounidense para el espectáculo había promocionado las producciones como adaptaciones "definitivas" de las obras de Shakespeare, lo que provocó muchas críticas de profesionales del teatro, cineastas y académicos. La afirmación de que el espectáculo incluiría producciones "definitivas" fue planteada y atacada con frecuencia por los medios estadounidenses durante sus siete años de emisión, especialmente cuando un episodio no estaba a la altura de las expectativas. [71]

Desde un punto de vista práctico, durante su mandato como productor, Messina no se involucró demasiado en la grabación de cada episodio. Si bien escogió al director, ayudó en el casting principal, asistió a algunos ensayos, visitó el set de vez en cuando y ocasionalmente observó la edición, el director fue responsable de las decisiones estéticas más importantes: ubicación y movimiento de la cámara, diseño de producción, vestuario, música y edición. [72]

El legado de Messina en relación con la BBC Television Shakespeare puede verse mejor como algo así como un conjunto de contradicciones: "lo que los primeros años en Messina le costaron a la serie en tensiones, alienaciones y falta de ideas nuevas o de una planificación técnica/estética vigorosa, nunca se recuperaría. El hecho de que tengamos la serie televisada de Shakespeare se debe enteramente a Messina; el hecho de que tengamos la serie de Shakespeare que tenemos y quizás no una mejor, más emocionante, también se debe en gran parte a Messina". [63]

Durante el mandato de Messina como productor, debido a las restricciones de los financieros, las adaptaciones tendieron a ser conservadoras, pero cuando Jonathan Miller tomó el mando al comienzo de la tercera temporada, renovó por completo las cosas. En un nivel superficial, por ejemplo, instituyó una nueva secuencia de título y reemplazó la música de William Walton con una pieza recién compuesta por Stephen Oliver . Sin embargo, los cambios de Miller fueron mucho más profundos. Mientras que Messina había favorecido un enfoque basado en el realismo, que sirvió para simplificar los textos para audiencias no familiarizadas con Shakespeare, Miller estaba en contra de cualquier tipo de dilución estética o intelectual. La teoría de Messina se basaba en sus muchos años de experiencia en televisión y, según Martin Wiggins, fue exactamente la falta de tal experiencia de Miller lo que llevó a su revisión estética del programa; Miller provenía de

Fuera de la tradición de la BBC de investigación minuciosa y verosimilitud histórica precisa [...] el enfoque de Messina había tratado las obras en términos realistas como eventos que habían tenido lugar una vez y que podían representarse literalmente en la pantalla. Miller las veía como productos de una imaginación creativa, artefactos por derecho propio que se podían realizar en una producción utilizando los materiales visuales y conceptuales de su período. Esto condujo a una reevaluación importante de las pautas de producción originales. [38]

Susan Willis señala algo similar: "en lugar de hacer lo que solía hacer la BBC, Miller vio la serie como un medio para examinar los límites del drama televisado, para ver lo que el medio podía hacer; era una aventura imaginativa y creativa". [63] Miller era en muchos sentidos el polo opuesto de Messina;

Si bien las producciones de Messina se ambientaban predominantemente en los períodos históricos a los que se hacía referencia, las de Miller eran insistentemente renacentistas en cuanto a vestimenta y actitud. Si se suponía que la televisión debía basarse en el realismo, Miller llevó las producciones directamente a las artes visuales de la época. Si la mayoría de las producciones anteriores habían sido visualmente cinematográficas, Miller enfatizó lo teatral. Si las interpretaciones anteriores eran básicamente sólidas y directas, Miller alentó interpretaciones más fuertes y nítidas, que fueran contrarias a la corriente principal, vívidas y no siempre convencionales. [73]

El propio Miller afirmó: "Creo que es muy poco inteligente intentar representar en la pantalla de televisión algo que Shakespeare no tenía en mente cuando escribió esas líneas. Hay que encontrar algún equivalente del escenario sin muebles para el que Shakespeare escribió sin, de hecho, reproducir necesariamente una versión del teatro Globe. Porque no hay forma de poder hacer eso [...] Los detalles que se introduzcan deben recordar a la audiencia la imaginación del siglo XVI". [74] Para Miller, la mejor manera de hacerlo era utilizando el trabajo de artistas famosos como inspiración visual y puntos de referencia;

El trabajo del director, además de trabajar con actores y conseguir interpretaciones sutiles y enérgicas, es actuar como presidente de una facultad de historia y de una facultad de historia del arte. He aquí un escritor que estaba inmerso en los temas y nociones de su tiempo. La única manera de liberar esa imaginación es sumergirse en los temas en los que él estaba inmerso. Y la única manera de hacerlo es mirando las imágenes que reflejan el mundo visual del que él formaba parte y familiarizándose con los problemas políticos y sociales que le preocupaban, tratando, de alguna manera, de identificarse con el mundo que era suyo. [74]

Sobre este tema, Susan Willis escribe:

Miller tenía una visión de Shakespeare como un dramaturgo isabelino/jacobino , como un hombre de su tiempo en cuanto a perspectiva social, histórica y filosófica. Las producciones que dirigió el propio Miller reflejan esta creencia con mayor claridad, por supuesto, pero también evocó esa conciencia en los demás directores. Si bien no había una única "firma" estilística para las obras bajo la producción de Miller, había más bien una actitudinal. Todo era reflexivo para el artista renacentista, pensaba Miller, sobre todo las referencias históricas, y así Antonio de Roma , Cleopatra de Egipto y tanto Timón como Teseo de Atenas adoptan un estilo y una apariencia familiares de finales del siglo XVI y principios del XVII. [75]

Como lo indica, Miller adoptó una política visual y de diseño de decorados y vestuario inspirados en grandes pinturas de la época en la que se escribieron las obras, aunque el estilo estaba dominado por los artistas post-shakesperianos del siglo XVII Vermeer y Rembrandt. En este sentido, "el arte no sólo proporciona una apariencia en las producciones de Miller; proporcionaba un modo de ser, una fragancia del aire que se respiraba en ese mundo, un clima intelectual además de un espacio físico". [76] Esta política permitió a otros directores estampar más de su propio credo estético en las producciones de lo que había sido posible bajo Messina. Según el propio Miller,

Cuando la BBC empezó a imaginar la serie, existía la idea de un Shakespeare "auténtico": algo que debía ser manipulado lo menos posible, de modo que se pudiera presentar a un público inocente a Shakespeare tal como podría haber sido antes de que apareciera en escena el director, tan imaginativo. Creo que se trataba de un error: la versión hipotética que consideraban auténtica era en realidad algo que se recordaba de treinta años antes y, en sí misma, presumiblemente muy diferente de lo que se representó en la producción inaugural hace cuatrocientos años. [77] Pensé que era mucho mejor reconocer la creatividad abierta de cualquier producción de Shakespeare, ya que no hay manera de regresar a una versión auténtica del Globe Theatre [...] Hay todo tipo de significados imprevisibles que podrían asociarse a la obra, simplemente en virtud del hecho de que ha sobrevivido en un período con el que el autor no estaba familiarizado, y por lo tanto es capaz de tocar acordes en la imaginación de una audiencia moderna que no podrían haber sido tocados en una audiencia cuando se representó por primera vez [...] las personas que realmente inauguraron la serie parecían notoriamente desinformadas con lo que había sucedido con Shakespeare, no conocían el trabajo académico y en realidad tenían una hostilidad anticuada del mundo del espectáculo hacia el mundo académico [...] No obstante, estaba limitado por ciertos requisitos contractuales que se habían establecido antes de que entrara en escena con los patrocinadores estadounidenses: sin embargo, hay todo tipo de formas de despellejar a ese tipo de gato, e incluso con el requisito de que tenía que poner las cosas en el llamado traje tradicional, había libertades que ellos no podían prever y que yo podía tomar. [77]

Hablando más directamente, Elijah Moshinsky evaluó la contribución de Miller a la serie al argumentar que "fue solo el nombramiento de Miller lo que sacó a la serie de su caída artística". [78] Hablando de las restricciones de EE. UU., Miller afirmó que "la instrucción era 'nada de trucos de mono', pero creo que los trucos de mono son al menos el 50 por ciento de lo que es dirigir de manera interesante [...] El hecho es que los trucos de mono solo son trucos de mono cuando no funcionan. Un truco de mono que funciona es un golpe de genialidad. Si comienzas con una ordenanza bastante completa y autonegativa de "nada de trucos de mono", entonces realmente estás muy encadenado". [79] De manera similar, hablando después de haber dejado de ser productor al final de la cuarta temporada, Miller afirmó: "Hice lo que quería hacer [...] Los patrocinadores insistieron en que era algo tradicional, que no molestaba a la gente con un entorno extraño. Y dije, vale, está bien, pero los molestaré con interpretaciones extrañas". [80] Miller no estaba interesado en la tradición escénica; no creó un Antonio heroico, una fierecilla ridícula o una Crésida desvergonzada . Su Otelo tenía poco que ver con la raza y su Lear era más un hombre de familia que un titán real. El propio Miller habló de su aversión por las "representaciones canónicas", afirmando: "Creo que hay una conspiración en el teatro para perpetuar ciertos prototipos en la creencia de que contienen la verdad secreta de los personajes en cuestión. Esta colusión entre actores y directores solo se rompe mediante una innovación exitosa que interrumpe el modo predominante". [81]

El primer episodio filmado bajo la producción de Miller fue Antonio y Cleopatra (aunque el primero en emitirse sería La fierecilla domada ), y fue en este episodio, que también dirigió, donde introdujo sus políticas de diseño, ya que se propuso "impregnar el diseño con la visión renacentista del mundo antiguo, ya que observó que el Renacimiento veía el mundo clásico en términos de sí mismo, con una conciencia contemporánea más que arqueológica; trataban temas clásicos pero siempre los vestían anacrónicamente con prendas renacentistas". [76]

Sin embargo, aunque Miller creó una nueva sensación de libertad estética, no se podía llevar esta libertad demasiado lejos. Por ejemplo, cuando contrató a Michael Bogdanov para dirigir Timón de Atenas , Bogdanov propuso una producción con vestuario moderno y temática oriental . Los financieros se negaron a aprobar la idea y Miller tuvo que insistir en que Bogdanov se mantuviera dentro de las pautas estéticas. Esto llevó a Bogdanov a dimitir y a que Miller asumiera la dirección. [82] Un aspecto de la producción de Messina que Miller sí reprodujo fue la tendencia a no involucrarse demasiado en el rodaje real de las producciones que no dirigía. Después de designar a un director y elegir un reparto, hacía sugerencias y estaba disponible para responder preguntas, pero creía que "el trabajo del productor es hacer que las condiciones sean lo más favorables y amistosas posibles, de modo que la imaginación [de los directores] tenga la mejor oportunidad posible de funcionar". [79]

Mientras que la BBC había buscado a un forastero que inyectara nuevas ideas al proyecto al comienzo de la tercera temporada, volvieron a buscar a alguien que llevara la serie a una conclusión: Shaun Sutton. Miller había rejuvenecido la serie estéticamente y sus producciones habían salvado su reputación ante los críticos, pero el programa se había retrasado, con Miller supervisando solo nueve episodios en lugar de doce durante sus dos años de producción. Sutton fue contratado para asegurarse de que el programa se completara sin sobrepasar demasiado el cronograma. Oficialmente, Sutton produjo las temporadas cinco, seis y siete, pero de hecho, asumió la producción a mitad de la filmación de la tetralogía Enrique VI / Ricardo III , que se filmó desde septiembre de 1981 hasta abril de 1982 y se emitió durante la quinta temporada a principios de 1983. Miller produjo La primera parte de Enrique VI y La segunda parte de Enrique VI , Sutton produjo La tercera parte de Enrique VI y La tragedia de Ricardo III . Sutton también produjo El rey Lear , dirigida por Miller, que se filmó en marzo y abril de 1982 y se emitió como la primera temporada de la quinta temporada en octubre de 1982. Como tal, a diferencia de la transición de Messina a Miller, la transición de Miller a Sutton fue prácticamente imperceptible.

Al comienzo de la sexta temporada, Sutton siguió los pasos de Miller al alterar la apertura del programa. Mantuvo la secuencia de títulos de Miller, pero eliminó la música de inicio de Stephen Oliver y, en su lugar, la música compuesta específicamente para cada episodio sirvió como música de inicio para ese episodio (excepto Los dos caballeros de Verona , que no tenía música original, por lo que se utilizó la música de inicio de Oliver de las temporadas 3 a 5).

Cuando se le preguntó cómo se sentía sobre el tiempo de Messina como productor, Sutton respondió simplemente "Pensé que el enfoque era un poco ordinario y que podríamos hacerlo mejor". [83] Sutton también continuó con la tendencia de Messina y Miller de dejar que los directores siguieran con el trabajo;

En todo drama hay tres cosas que importan: el guión, el director y el reparto. Si las tres cosas son buenas, no importa si lo haces en decorados de cartón o con una iluminación moderada; en televisión, a veces, ni siquiera importa si está mal filmado [...] Los guiones son la base de todo, más que la forma en que los presentas. Escritores, directores, actores; si esos tres son buenos, puedes hacerlo en la parte trasera de un carrito. [84]

El proyecto fue el trabajo de jubilación de Sutton después de doce años como jefe de BBC Drama y tenía órdenes estrictas de cerrar la serie, algo que hizo con éxito, con la emisión de Titus Andronicus aproximadamente doce meses después de lo que la serie había sido inicialmente programada para terminar.

La apuesta de Messina en 1978 finalmente resultó exitosa, ya que la serie fue un éxito financiero y en 1982 ya estaba dando ganancias. Esto se debió principalmente a las ventas a los mercados extranjeros, con muchos más países que exhibieron la serie de lo que se esperaba inicialmente; además del Reino Unido y los EE. UU., el programa se emitió en Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Bahréin, Barbados, Bélgica, Bután, Bulgaria, Canadá, Chile, China, Colombia, Checoslovaquia, Dubai, Egipto, Francia, Grecia, Honduras, Hong Kong, Hungría, India, Irak, Irlanda, Italia, Jamaica, Japón, Jordania, Kenia, Corea, Líbano, Malasia, México, Países Bajos, Nueva Zelanda, Panamá, Perú, Filipinas, Polonia, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Qatar, Rumania, Arabia Saudita, Singapur, España, Sri Lanka, Taiwán, Tailandia, Trinidad y Tobago, Turquía, Venezuela, Alemania Occidental y Yugoslavia. [85]

En 1985, Cecil Smith, escribiendo para el diario Los Angeles Times , señaló que «la serie ha sido objeto de silbidos críticos en ambos lados del Atlántico, tratada de forma miserable por muchas estaciones de PBS y, a menudo, ignorada o condenada como aburrida, aburrida, aburrida». [86] Los primeros episodios, en particular, recibieron críticas. Hablando de Romeo y Julieta , Clive James escribió en The Observer : «Verona parecía haber sido construida sobre un terreno muy plano, como el suelo de un estudio de televisión. El hecho de que esta artificialidad fuera medio aceptada, medio negada, te decía que no estabas en Verona en absoluto, sino en esa ciudad semiabstracta, semiconcreta y totalmente poco interesante que los estudiantes conocen como Messina». [87] También hablando de Romeo y Julieta , Richard Last del Daily Telegraph predijo que «el Shakespeare de la BBC Television será, por encima de todo, estilísticamente seguro. La tradición y la consolidación, en lugar de la aventura o la experimentación, serán las piedras de toque». [88]

En su reseña de la primera temporada para The Daily Telegraph , Sean Day-Lewis afirmó que Romeo y Julieta , Como gustéis y Julio César no tuvieron éxito, mientras que El rey Ricardo II , Medida por medida y La famosa historia de la vida del rey Enrique VIII sí lo tuvieron. Sin embargo, incluso en los fracasos, encontró cualidades y, como tal, "no ha sido un mal comienzo, dado que algunos directores son nuevos en los problemas de traducir a Shakespeare a la televisión". [89]

En una reseña de la producción de la segunda temporada de La tempestad para The Times Literary Supplement , Stanley Reynolds opinó que, si bien "hay muy poco que los puristas puedan criticar [...] lo más condenatorio que se puede decir de ella es que no hay nada que haga que la sangre se encienda hasta los arrebatos de ira o que genere la alegría eléctrica de una nueva experiencia. Lo que obtuvimos fue algo más del horrible sabor medio de la BBC". [90]

Cuando la serie se acercaba a su fin, Andrew Rissik de Literary Review escribió: "Ahora que la BBC está terminando su Shakespeare con Tito Andrónico , debe ser evidente que toda la aventura ha sido imprudente y equivocada [...] Las primeras producciones de Messina fueron torpes y poco específicas, mal filmadas en lo principal y con un reparto mediocre. Las producciones de Miller fueron una clara mejora; su estilo visual era preciso y distintivo y el reparto, en general, inteligentemente realizado [...] Pero la serie no ha sido un éxito". [91] Hablando más sin rodeos, Michael Bogdanov calificó la serie como "el mayor perjuicio para Shakespeare en los últimos 25 años". [92]

Elenco

Rebecca Saire tenía tan solo catorce años cuando se filmó la producción, una edad inusualmente joven para una actriz que interpreta a Julieta, aunque el personaje tiene tan solo trece años. En entrevistas con la prensa previas a la transmisión, Saire criticó al director Alvin Rakoff, afirmando que en su interpretación, Julieta es demasiado infantil y asexual. Esto horrorizó a los productores de la serie, quienes cancelaron varias entrevistas programadas con la actriz en el período previo a la transmisión. [93]

El episodio Prefaces to Shakespeare de Romeo & Juliet fue presentado por Peggy Ashcroft , quien había interpretado a Julieta en una producción de la Oxford University Dramatic Society de 1932 dirigida por John Gielgud. El episodio Shakespeare in Perspective fue presentado por la académica feminista y periodista Germaine Greer .

Elenco

Este episodio se repitió el 12 de diciembre de 1979 en el Reino Unido y el 19 de marzo de 1980 en los EE. UU., como introducción a la trilogía Enrique IV / Enrique V. El episodio Shakespeare en perspectiva que presentó al rey Ricardo II fue presentado por el historiador Paul Johnson , quien argumentó que la Henriada hizo avanzar mucho el mito Tudor , algo que también argumentó Graham Holderness , quien vio la presentación de la BBC de la Henriada como "una ilustración de la violación del 'orden' social natural por la deposición de un rey legítimo". [94]

El director David Giles filmó el episodio de tal manera que creó una metáfora visual de la posición de Richard en relación con la corte . Al principio de la producción, se lo ve constantemente por encima del resto de los personajes, especialmente en lo alto de las escaleras, pero siempre desciende al mismo nivel que todos los demás y, a menudo, termina por debajo de ellos. A medida que avanza el episodio, su posicionamiento por encima de los personajes se vuelve cada vez menos frecuente. [95] Un movimiento interpretativo de Giles que fue especialmente bien recibido por los críticos fue su división del largo soliloquio de la celda de prisión de Richard en varias secciones, que se desvanecen de una a otra, lo que sugiere un paso del tiempo y un proceso de pensamiento continuo que se desarrolla lentamente. [96]

El episodio de Prefaces to Shakespeare para King Richard the Second fue presentado por Ian Richardson , quien había protagonizado una producción de RSC de 1974 dirigida por John Barton, en la que había alternado los papeles de Richard y Bolingbroke con el actor Richard Pasco .

Elenco

La producción se filmó en el castillo de Glamis en Escocia, una de las dos únicas producciones filmadas en locaciones, siendo la otra The Famous History of the Life of Henry the Eight . Sin embargo, el rodaje en locaciones recibió una respuesta tibia tanto de los críticos como de la propia gente de la BBC, con el consenso general de que el mundo natural en el episodio abrumaba a los actores y la historia. [97] El director Basil Coleman inicialmente sintió que la obra debería filmarse en el transcurso de un año, con el cambio de estaciones de invierno a verano marcando el cambio ideológico en los personajes, pero se vio obligado a filmar completamente en mayo, a pesar de que la obra comienza en invierno. Esto, a su vez, significó que la dureza del bosque descrito en el texto fue reemplazada por una vegetación exuberante, que era claramente inofensiva, y el "tiempo en el bosque de los personajes parecía ser más una expedición de campamento de lujo que un exilio". [97]

El episodio de Prefacios de Shakespeare para Como gustéis fue presentado por Janet Suzman , quien había interpretado a Rosalind en una producción de la RSC de 1967 dirigida por George Rylands . El episodio de Shakespeare en perspectiva fue presentado por la novelista Brigid Brophy .

Elenco

El director Herbert Wise consideró que Julio César debería estar ambientada en la época isabelina , pero en lugar de ello, en aras del realismo, la situó en un entorno romano . [98] Wise argumentó que la obra "no es realmente una obra romana. Es una obra isabelina y es una visión de Roma desde un punto de vista isabelino". En cuanto a ambientar la obra en la época de Shakespeare, Wise afirmó que "no creo que eso sea adecuado para el público al que nos vamos a dirigir. No se trata de un público de teatro hastiado que ve la obra por enésima vez: para ellos sería un enfoque interesante y podría arrojar nueva luz sobre la obra. Pero para un público que, en su mayoría, no habrá visto la obra antes, creo que sólo sería confuso". [99]

El episodio Prefaces to Shakespeare de Julio César fue presentado por Ronald Pickup , quien había interpretado a Octavio César en una producción del Royal Court Theatre de 1964 dirigida por Lindsay Anderson , y a Casio en una producción del National Theatre de 1977 dirigida por John Schlesinger . El episodio Shakespeare en perspectiva fue presentado por el comentarista político Jonathan Dimbleby .

Cast

The role of the Duke was originally offered to Alec Guinness. After he turned it down, the role was offered to a further thirty-one actors before Kenneth Colley accepted the part.[100]

Director Desmond Davis based the brothel in the play on a traditional Western saloon and the prison on a typical horror film dungeon.[101] The set for the episode was a 360-degree set backed by a cyclorama, which allowed actors to move from location to location without cutting – actors could walk through the streets of Vienna by circumnavigating the studio eight times.[102] For the interview scenes, Davis decided to link them aesthetically and shot both in the same manner; Angelo was shot upwards from waist level to make him look large, Isabella was shot from further away so more background was visible in her shots, making her appear smaller. Gradually, the shots then move towards each other's style so that, by the end of the scene, they are both shot in the same framing.[103]

The Prefaces to Shakespeare episode for Measure for Measure was presented by Judi Dench, who had played Isabella in a 1962 RSC production directed by Peter Hall. The Shakespeare in Perspective episode was presented by barrister and author Sir John Mortimer.

Cast

The second of only two episodes shot on location, after As You Like It. Whereas the location shooting in that episode was heavily criticised as taking away from the play, here, the location work was celebrated.[97] The episode was shot at Leeds Castle, Penshurst Place and Hever Castle, in the actual rooms in which some of the real events took place.[104] Director Kevin Billington felt that location shooting was essential to the production; "I wanted to get away from the idea that this is some kind of fancy pageant. I wanted to feel the reality. I wanted great stone walls [...] We shot at Hever Castle, where Anne Bullen lived; at Penhurst, which was Buckingham's place; and at Leeds Castle, where Henry was with Anne Bullen."[105] Shooting on location had several benefits; the camera could be set up in such a way as to show ceilings, which cannot be done when shooting in a TV studio, as rooms are ceilingless to facilitate lighting. The episode was shot in winter, and on occasions, characters' breath can be seen, which was also impossible to achieve in studio. However, because of the cost, logistics and planning required for shooting on location, Messina decided that all subsequent productions would be done in-studio, a decision which did not go down well with several of the directors lined up for work on the second season.

This episode was not originally supposed to be part of the first season, but was moved forward in the schedule to replace the abandoned production of Much Ado About Nothing.[36] It was repeated on 22 June 1981.

The Prefaces to Shakespeare episode for The Famous History of the Life of King Henry the Eight was presented by Donald Sinden, who had played Henry in a 1969 RCS production directed by Trevor Nunn. The Shakespeare in Perspective episode was presented by novelist and literary scholar Anthony Burgess.

Cast

The week prior to the screening of this episode in both the UK and the US, the first-season episode King Richard the Second was repeated as a lead-in to the trilogy. The episode also began with Richard's death scene from the previous play.

The Prefaces to Shakespeare episode for The First Part of King Henry the Fourth was presented by Michael Redgrave who had played Hotspur in a 1951 RSC production directed by Anthony Quayle. The Shakespeare in Perspective episode was presented by musician, art historian and critic George Melly.

Cast

This episode starts with a reprise of the death of Richard, followed by an excerpt from the first-season episode King Richard the Second. Rumour's opening soliloquy is then heard in voice-over, played over scenes from the previous week's The First Part of King Henry the Fourth; Henry's lamentation that he has not been able to visit the Holy Land, and the death of Hotspur at the hands of Prince Hal. With over a quarter of the lines from the Folio text cut, this production had more material omitted than any other in the entire series.[106]

The Prefaces to Shakespeare episode for The Second Part of King Henry the Fourth was presented by Anthony Quayle who portrayed Falstaff in the BBC adaptation, and had also played the role several times on-stage, included a celebrated 1951 RSC production, which he directed with Michael Redgrave. The Shakespeare in Perspective episode was presented by psychologist Fred Emery.

Cast

Director John Giles and production designer Don Homfray both felt this episode should look different from the two Henry IV plays. While they had been focused on rooms and domestic interiors, Henry V was focused on large open spaces. As such, because they could not shoot on location, and because creating realistic reproductions of such spaces in a studio was not possible, they decided on a more stylised approach to production design than had hitherto been seen in the series. Ironically, the finished product looked more realistic than either of them had anticipated or desired.[107]

Dennis Channon won Best Lighting at the 1980 BAFTAs for his work on this episode. The episode was repeated on Saint George's Day (23 April) in 1980.

The Prefaces to Shakespeare episode for The Life of Henry the Fift was presented by Robert Hardy who had played Henry V in the 1960 BBC television series An Age of Kings. The Shakespeare in Perspective episode was presented by politician Alun Gwynne Jones.

Cast

Director John Gorrie interpreted Twelfth Night as an English country house comedy, and incorporated influences ranging from Luigi Pirandello's play Il Gioco delle Parti to ITV's Upstairs, Downstairs.[108] Gorrie also set the play during the English Civil War in the hopes the use of cavaliers and roundheads would help focus the dramatisation of the conflict between festivity and Puritanism.[38] Gorrie wanted the episode to be as realistic as possible, and in designing Olivia's house, made sure that the geography of the building was practical. He then shot the episode in such a way that the audience becomes aware of the logical geography, often shooting characters entering and exiting doorways into rooms and corridors.[109]

The Prefaces to Shakespeare episode for Twelfth Night was presented by Dorothy Tutin who had played Viola in a 1958 RSC production directed by Peter Hall. The Shakespeare in Perspective episode was presented by painter and poet David Jones.

Cast

The episode used a 360-degree set, which allowed actors to move from the beach to the cliff to the orchard without edits. The orchard was composed of real apple trees.[110] The visual effects seen in this episode were not developed for use here. They had been developed for Top of the Pops and Doctor Who.[108] John Gielgud was originally cast as Prospero, but contractual conflicts delayed the production, and by the time Messina had sorted them out, Gielgud was unavailable.[111]

The Prefaces to Shakespeare episode for The Tempest was presented by Michael Hordern who portrayed Prospero in the BBC adaptation. The Shakespeare in Perspective episode was presented by philosopher Laurens van der Post.

Cast