Rhode Island ( / ˌ r oʊ d -/ , pronunciado "road")[6][7]es unestadoen laNueva Inglaterradelnoreste los Estados Unidos. Limita conConnecticutal oeste;Massachusettsal norte y al este; y elocéano Atlánticoal sur a través deRhode Island SoundyBlock Island Sound; y comparte una pequeñafrontera marítimaconNueva York, al este deLong Island.[8]Rhode Island es elestado más pequeño de EE. UU. por áreay elséptimo menos poblado, con un poco menos de 1,1 millones de residentesen 2020;[9]pero ha crecido en cadarecuento decenaldesde 1790 y es elsegundo estado más densamente poblado, después deNueva Jersey. El estado toma su nombre dela isla homónima, aunque casi toda su superficie terrestre está en el continente.Providencees su capital y ciudad más poblada.

Los nativos americanos vivían alrededor de la bahía de Narragansett antes de que los colonos ingleses comenzaran a llegar a principios del siglo XVII. [10] Rhode Island fue única entre las Trece Colonias Británicas al haber sido fundada por un refugiado, Roger Williams , que huyó de la persecución religiosa en la Colonia de la Bahía de Massachusetts para establecer un refugio para la libertad religiosa. Fundó Providence en 1636 en tierras compradas a tribus locales, creando el primer asentamiento en América del Norte con un gobierno explícitamente secular. [10] La Colonia de Rhode Island y las Plantaciones de Providence posteriormente se convirtieron en un destino para disidentes religiosos y políticos y marginados sociales, lo que le valió el apodo de "Isla de los Pícaros". [11]

Rhode Island fue la primera colonia en convocar un Congreso Continental , en 1774, y la primera en renunciar a su lealtad a la Corona británica , el 4 de mayo de 1776. [12] Después de la Revolución estadounidense , durante la cual estuvo fuertemente ocupada y disputada, Rhode Island se convirtió en el cuarto estado en ratificar los Artículos de la Confederación , el 9 de febrero de 1778. [13] Debido a que sus ciudadanos favorecían un gobierno central más débil, boicoteó la convención de 1787 que había redactado la Constitución de los Estados Unidos , [14] que inicialmente se negó a ratificar; [15] finalmente la ratificó el 29 de mayo de 1790, el último de los 13 estados originales en hacerlo. [16] [17]

El estado se llamó oficialmente Estado de Rhode Island y Plantaciones de Providence desde la era colonial, pero pasó a ser conocido comúnmente como "Rhode Island". En noviembre de 2020, los votantes del estado aprobaron una enmienda a la constitución estatal que elimina formalmente "y Plantaciones de Providence" de su nombre completo. [18] Su apodo oficial es "Estado del Océano", una referencia a sus 400 millas (640 km) de costa y las grandes bahías y ensenadas que constituyen aproximadamente el 14% de su área. [19]

A pesar de su nombre, la mayor parte de Rhode Island se encuentra en el continente estadounidense. Su nombre oficial fue Estado de Rhode Island y Plantaciones de Providence desde su inicio en 1636 hasta 2020, y se menciona de esa manera en la Constitución de los Estados Unidos . [20] Este nombre se derivó de la fusión de asentamientos coloniales alrededor de la bahía de Narragansett, y fuera de la jurisdicción de la colonia de Plymouth. Los asentamientos de Rhode Island ( Newport y Portsmouth ) estaban en Rhode Island, también conocida como isla Aquidneck . [b] [21] Las Plantaciones de Providence se referían a asentamientos en el continente de Providence y Warwick . [22]

No está claro cómo la isla llegó a llamarse Rhode Island , pero dos eventos históricos pueden haber sido influyentes:

El primer uso documentado del nombre "Rhode Island" para Aquidneck fue en 1637 por Roger Williams. El nombre se aplicó oficialmente a la isla en 1644 con estas palabras: "A partir de ahora Aquethneck se llamará Isla de Rodes o Rhode Island". El nombre "Isla de Rodes" se utiliza en un documento legal en fecha tan tardía como 1646. [27] [28] Los mapas holandeses de 1659 llaman a la isla "Isla Roja" ( Roodt Eylandt ). [29]

El primer asentamiento inglés en Rhode Island fue la ciudad de Providence, que los Narragansett otorgaron a Roger Williams en 1636. [ cita requerida ] En ese momento, Williams no obtuvo permiso de la corona inglesa, ya que creía que los ingleses no tenían ningún reclamo legítimo sobre el territorio de Narragansett y Wampanoag . [30] [ verificación necesaria ] Williams viajó a Londres en 1643, durante la Guerra Civil Inglesa, para obtener el reconocimiento legal de los nuevos asentamientos. Se otorgó una patente para "la incorporación de las Plantaciones de Providence en la Bahía de Narragansett en Nueva Inglaterra" por el comité parlamentario sobre Plantaciones Extranjeras . [31] Después de la Guerra Civil Inglesa, se otorgó una Carta Real en 1663, dando a la colonia un nombre oficial de "Gobernador y Compañía de la Colonia Inglesa de Rhode Island y Plantaciones de Providence, en Nueva Inglaterra, en América". [32] Después de la Revolución Americana , en 1790 el nuevo estado se incorporó como el "Estado de Rhode Island y Plantaciones de Providence". Sin embargo, por conveniencia, el estado pasó a ser conocido simplemente como "Rhode Island".

La palabra plantación en el nombre del estado se convirtió en un tema controvertido durante el siglo XX y la creciente conciencia de la esclavitud y su papel en la historia temprana de Rhode Island. La Asamblea General votó en 2009 para celebrar un referéndum en noviembre de 2010 para eliminar "y Providence Plantations" del nombre oficial. Los defensores de la eliminación de plantación argumentaron que la palabra simbolizaba un legado de privación de derechos para muchos habitantes de Rhode Island, así como la proliferación de la esclavitud en las colonias y en los Estados Unidos poscoloniales. Los defensores de mantener el nombre argumentaron que plantación era simplemente un sinónimo arcaico de colonia y no guardaba relación con la esclavitud. La gente votó abrumadoramente (78% a 22%) para mantener todo el nombre original. [33]

En junio de 2020, el senador estatal Harold Metts presentó una resolución para otro referéndum sobre el tema, diciendo: "Cualquiera que sea el significado del término 'plantaciones' en el contexto de la historia de Rhode Island, conlleva una connotación horrible cuando se considera la historia trágica y racista de nuestra nación". [34] La gobernadora Gina Raimondo emitió una orden ejecutiva para eliminar la frase de una variedad de documentos oficiales y sitios web estatales. [35] En julio, en medio de las protestas de George Floyd y los llamados a nivel nacional para abordar el "racismo sistémico", la resolución que remitía la cuestión a los votantes fue aprobada por ambas cámaras de la Asamblea General de Rhode Island : 69-1 en la Cámara de Representantes , [36] y 35-0 en el Senado . [37] El cambio fue luego aprobado por los votantes 52,8% a 47,2% como parte de las elecciones de Estados Unidos de 2020 , entrando en vigor en noviembre de 2020 tras la certificación de los resultados. [18] [38]

Al comienzo de la colonización europea, lo que ahora es Rhode Island estaba habitado principalmente por cinco tribus nativas americanas: la mayor parte del territorio del estado estaba habitado por los narragansett , las tierras fronterizas del este estaban ocupadas por los wampanoag , la costa suroeste por los niantic , las tierras fronterizas del oeste por los pequot y las tierras fronterizas del norte por los nipmuc . [39] [ ¿ Fuente autoeditada? ] [40] En 1636, Roger Williams fue desterrado de la Colonia de la Bahía de Massachusetts por sus opiniones religiosas, y se instaló en la parte superior de la Bahía de Narragansett en tierras vendidas o donadas por Narragansett sachem Canonicus . Llamó al sitio Providencia, "teniendo un sentido de la providencia misericordiosa de Dios hacia mí en mi angustia", [41] y se convirtió en un lugar de libertad religiosa donde todos eran bienvenidos.

En 1638 (después de consultar con Williams), Anne Hutchinson , William Coddington , John Clarke , Philip Sherman y otros disidentes religiosos recibieron permiso para establecerse en la isla Aquidneck (también conocida como Rhode Island), por parte de los Narragansett Sachems Canonicus y Miantonomi . Se les dieron algunos artículos a cambio de su generosidad. Sin embargo, como Roger Williams dejó en claro en una carta a John Winthrop en junio de 1638: "Señor, en lo que respecta a las islas Prudence y... Aquedenick... ninguna de ellas se vendió adecuadamente, ya que mil brazas no habrían comprado ninguna de las dos, por extraños. La verdad es que no se exigió ni un centavo por ninguna de ellas, y lo que se pagó fue solo una gratificación, aunque elegí, para mayor seguridad y forma, llamarlo venta". [42] Este asentamiento primero se llamó Pocasset y luego cambió en 1639 a Portsmouth . La ciudad estaba gobernada por el Pacto de Portsmouth . La parte sur de la isla se convirtió en el asentamiento separado de Newport después de desacuerdos entre los fundadores.

En 1642, Samuel Gorton compró tierras en Shawomet a los Narragansett, lo que precipitó una disputa con la Colonia de la Bahía de Massachusetts. En 1644, Providence, Portsmouth y Newport se unieron para lograr su independencia común como la Colonia de Rhode Island y las Plantaciones de Providence , gobernadas por un consejo electo y un "presidente". Gorton recibió una carta separada para su asentamiento en 1648, a la que llamó Warwick en honor a su patrón. [43]

Metacomet era el líder de guerra de la tribu Wampanoag , a quien los colonos llamaban Rey Felipe. Invadieron y quemaron varias de las ciudades de la zona durante la Guerra del Rey Felipe (1675-1676), incluida Providence, que fue atacada dos veces. [41] Una fuerza de la milicia de Massachusetts, Connecticut y Plymouth bajo el mando del general Josiah Winslow invadió y destruyó la aldea indígena fortificada de Narragansett en el Gran Pantano en South Kingstown, Rhode Island , el 19 de diciembre de 1675. [44] En una de las acciones finales de la guerra, un indio asociado con Benjamin Church mató al Rey Felipe en Bristol, Rhode Island . [45]

La colonia se fusionó con el Dominio de Nueva Inglaterra en 1686, cuando el rey Jaime II intentó imponer la autoridad real sobre las colonias autónomas de la América del Norte británica , pero la colonia recuperó su independencia bajo la Carta Real después de la Revolución Gloriosa de 1688. Los esclavos se introdujeron en Rhode Island en esta época, aunque no hay registro de ninguna ley que legalizara la tenencia de esclavos. La colonia prosperó más tarde gracias al comercio de esclavos, destilando ron para venderlo en África como parte de un rentable comercio triangular de esclavos y azúcar con el Caribe. [47] El cuerpo legislativo de Rhode Island aprobó una ley en 1652 que abolía la tenencia de esclavos (la primera colonia británica en hacerlo), pero este edicto nunca se aplicó y Rhode Island continuó estando muy involucrada en el comercio de esclavos durante la era posterior a la revolución. [48] En 1774, la población esclava de Rhode Island era el 6,3% del total (casi el doble de la proporción de otras colonias de Nueva Inglaterra ). [49] [50]

La Universidad Brown fue fundada en 1764 como la universidad de la colonia británica de Rhode Island y las plantaciones de Providence. Fue una de las nueve universidades coloniales a las que se les concedió la carta antes de la Revolución estadounidense y fue la primera universidad de Estados Unidos en aceptar estudiantes independientemente de su afiliación religiosa. [51]

_(cropped).jpg/440px-Destruction_of_the_schooner_Gaspé_in_the_waters_of_Rhode_Island_1772_(NYPL_b12349146-422875)_(cropped).jpg)

La tradición de independencia y disidencia de Rhode Island le dio un papel destacado en la Revolución estadounidense . Aproximadamente a las 2 a. m. del 10 de junio de 1772, una banda de residentes de Providence atacó la goleta de ingresos encallada HMS Gaspée , quemándola hasta la línea de flotación por hacer cumplir regulaciones comerciales impopulares dentro de la bahía de Narragansett. [52] Rhode Island fue la primera de las trece colonias en renunciar a su lealtad a la Corona británica el 4 de mayo de 1776. [53] También fue la última de las trece colonias en ratificar la Constitución de los Estados Unidos el 29 de mayo de 1790, y solo bajo la amenaza de fuertes aranceles comerciales de las otras ex colonias y después de que se dieron garantías de que una Declaración de Derechos se convertiría en parte de la Constitución. [54]

Durante la Revolución, los británicos ocuparon Newport en diciembre de 1776. Una fuerza combinada franco-estadounidense luchó para expulsarlos de la isla Aquidneck. Portsmouth fue el sitio de la primera unidad militar afroamericana, el 1.er Regimiento de Rhode Island , que luchó por los EE. UU. en la fallida Batalla de Rhode Island del 29 de agosto de 1778. [55] Un mes antes, la aparición de una flota francesa frente a Newport hizo que los británicos hundieran algunos de sus propios barcos en un intento de bloquear el puerto. Los británicos abandonaron Newport en octubre de 1779, concentrando sus fuerzas en la ciudad de Nueva York. Una expedición de 5500 tropas francesas al mando del conde Rochambeau llegó a Newport por mar el 10 de julio de 1780. [56] La célebre marcha a Yorktown, Virginia , en 1781 terminó con la derrota de los británicos en el Sitio de Yorktown y la Batalla de Chesapeake .

Rhode Island también estuvo muy involucrado en la Revolución Industrial , que comenzó en Estados Unidos en 1787 cuando Thomas Somers reprodujo planos de máquinas textiles que importó de Inglaterra. Ayudó a producir la fábrica de algodón Beverly , en la que se interesó Moses Brown de Providence. Moses Brown se asoció con Samuel Slater y ayudó a crear la segunda fábrica de algodón en Estados Unidos, una fábrica textil impulsada por agua. La Revolución Industrial trasladó a un gran número de trabajadores a las ciudades. Con la carta colonial de 1663 todavía en vigor, el voto estaba restringido a los terratenientes que poseían al menos $ 134 en propiedades. En el momento de la revolución, el 80% de los hombres blancos en Rhode Island podían votar; en 1840, solo el 40% todavía eran elegibles. [57] La carta distribuyó los escaños legislativos de manera equitativa entre las ciudades del estado, sobrerrepresentando las áreas rurales y subrepresentando los centros industriales en crecimiento. Además, la carta prohibía a los ciudadanos sin tierras presentar demandas civiles sin el respaldo de un terrateniente. [58] Periódicamente se presentaban en la legislatura proyectos de ley para ampliar el sufragio, pero invariablemente eran rechazados.

En 1841, activistas liderados por Thomas W. Dorr organizaron una convención extralegal para redactar una constitución estatal, [59] argumentando que el gobierno de la carta violaba la Cláusula de Garantía en el Artículo Cuatro, Sección Cuatro de la Constitución de los Estados Unidos . En 1842, el gobierno de la carta y los partidarios de Dorr celebraron elecciones separadas, y dos gobiernos rivales reclamaron la soberanía sobre el estado. Los partidarios de Dorr lideraron una rebelión armada contra el gobierno de la carta, y Dorr fue arrestado y encarcelado por traición contra el estado. [60]

En respuesta, la legislatura redactó una constitución estatal que reemplazó los requisitos de propiedad para los ciudadanos nacidos en Estados Unidos con un impuesto electoral de $1 , equivalente a $32 en 2023. En una elección fuertemente boicoteada en noviembre de 1842, los votantes aprobaron la constitución. [ cita requerida ] Los votantes también se negaron a limitar el cambio a los hombres "blancos", lo que volvió a otorgar el derecho al voto a los hombres negros (los hombres negros que cumplían con los requisitos de propiedad habían podido votar en Rhode Island hasta 1822). La constitución también puso fin a la esclavitud. Los inmigrantes siguieron sujetos al requisito de propiedad, privando efectivamente del derecho al voto a muchos irlandeses-estadounidenses y manteniendo la subrepresentación urbana. [61] [62] En 1849, en Luther v. Borden , la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos se negó a pronunciarse sobre la cuestión constitucional planteada en la rebelión de Dorr, sosteniendo que era una cuestión política fuera de su jurisdicción.

A principios del siglo XIX, Rhode Island sufrió un brote de tuberculosis que provocó una histeria pública sobre el vampirismo . [63] [64]

Durante la Guerra Civil estadounidense , Rhode Island fue el primer estado de la Unión en enviar tropas en respuesta a la solicitud de ayuda del presidente Lincoln a los estados. Rhode Island proporcionó 25.236 hombres combatientes, de los cuales 1.685 murieron. [ cita requerida ] En el frente interno, Rhode Island y los demás estados del norte utilizaron su capacidad industrial para suministrar al Ejército de la Unión los materiales que necesitaba para ganar la guerra. La Academia Naval de los Estados Unidos se trasladó a Rhode Island temporalmente durante la guerra.

En 1866, Rhode Island abolió la segregación racial en las escuelas públicas de todo el estado. [65]

Los 50 años posteriores a la Guerra Civil fueron una época de prosperidad y opulencia que el autor William G. McLoughlin llama "la era dorada de Rhode Island". Rhode Island fue un centro de la Edad Dorada y proporcionó un hogar o casa de verano a muchos de los industriales más destacados del país. Esta fue una época de crecimiento en las fábricas textiles y la manufactura y trajo una afluencia de inmigrantes para cubrir esos puestos de trabajo, lo que trajo consigo el crecimiento de la población y la urbanización. En Newport , los industriales más ricos de Nueva York crearon un refugio de verano para socializar y construir grandes mansiones . Miles de inmigrantes francocanadienses, italianos, irlandeses y portugueses llegaron para cubrir puestos de trabajo en las fábricas textiles y manufactureras de Providence, Pawtucket, Central Falls y Woonsocket. [66]

Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, Rhode Island proporcionó 28.817 soldados, de los cuales 612 murieron. Después de la guerra, el estado se vio duramente afectado por la gripe española . [67]

En las décadas de 1920 y 1930, la zona rural de Rhode Island vio un aumento en la membresía del Ku Klux Klan , en gran medida como reacción a las grandes oleadas de inmigrantes que se mudaban al estado. Se cree que el Klan es responsable de la quema de la Escuela Industrial Watchman en Scituate , que era una escuela para niños afroamericanos. [68]

Desde la Gran Depresión , el Partido Demócrata de Rhode Island ha dominado la política local. Rhode Island cuenta con un seguro médico integral para niños de bajos ingresos y una amplia red de seguridad social . Sin embargo, muchas áreas urbanas aún tienen una alta tasa de pobreza infantil. Debido a la afluencia de residentes de Boston , el aumento de los costos de la vivienda ha provocado que haya más personas sin hogar en Rhode Island. [69]

El 350 aniversario de la fundación de Rhode Island se celebró con un concierto gratuito celebrado en la pista del Aeropuerto Estatal de Quonset el 31 de agosto de 1986. Entre los artistas que actuaron se encontraban Chuck Berry , Tommy James y el cabeza de cartel Bob Hope .

Rhode Island cubre un área de 1034 millas cuadradas (2678 km 2 ) [2] dentro de la región de Nueva Inglaterra del noreste de los Estados Unidos y limita al norte y al este con Massachusetts, al oeste con Connecticut y al sur con Rhode Island Sound y el océano Atlántico. [19] Comparte una estrecha frontera marítima con el estado de Nueva York entre Block Island y Long Island . La elevación media del estado es de 200 pies (61 m). Tiene solo 37 millas (60 km) de ancho y 48 millas (77 km) de largo, sin embargo, el estado tiene una costa de marea en la bahía de Narragansett y el océano Atlántico de 384 millas (618 km). [70]

Rhode Island es conocido como el Estado del Océano y tiene varias playas frente al mar . Es mayormente plano sin montañas reales, y el punto natural más alto del estado es Jerimoth Hill , a 812 pies (247 m) sobre el nivel del mar. [71] El estado tiene dos regiones naturales distintas. El este de Rhode Island contiene las tierras bajas de la bahía de Narragansett, mientras que el oeste de Rhode Island forma parte de las tierras altas de Nueva Inglaterra. Los bosques de Rhode Island son parte de la ecorregión de bosques costeros del noreste . [72]

La bahía de Narragansett es una característica importante de la topografía del estado. Hay más de 30 islas dentro de la bahía; la más grande es la isla Aquidneck , que alberga los municipios de Newport, Middletown y Portsmouth. La segunda isla más grande es Conanicut y la tercera es Prudence . La isla Block se encuentra a unas 12 millas (19 km) de la costa sur del continente y separa el estrecho de Block Island y el océano Atlántico propiamente dicho. [73] [74]

Un tipo raro de roca llamada cumberlandita se encuentra solo en Rhode Island (específicamente, en la ciudad de Cumberland ) y es la roca estatal. Inicialmente, había dos depósitos conocidos del mineral, pero es un mineral de hierro, y uno de los depósitos fue extraído extensivamente por su contenido ferroso. [75] [d]

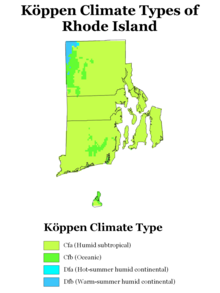

La mayor parte de Rhode Island tiene un clima continental húmedo , con veranos cálidos e inviernos fríos. Las porciones costeras del sur del estado son la amplia zona de transición hacia climas subtropicales, con veranos cálidos e inviernos fríos con una mezcla de lluvia y nieve. Block Island tiene un clima oceánico . La temperatura más alta registrada en Rhode Island fue de 104 °F (40 °C), registrada el 2 de agosto de 1975, en Providence. [77] La temperatura más baja registrada en Rhode Island fue de -23 °F (-31 °C) el 5 de febrero de 1996, en Greene . [78] Las temperaturas medias mensuales varían desde una máxima de 83 °F (28 °C) hasta una mínima de 20 °F (-7 °C). [79]

Rhode Island es vulnerable a tormentas tropicales y huracanes debido a su ubicación en Nueva Inglaterra, y recibe la peor parte de muchas tormentas que destruyen la costa este. Los huracanes que han causado daños importantes en el estado incluyen el huracán de Nueva Inglaterra de 1938 , el huracán Carol (1954), el huracán Donna (1960) y el huracán Bob (1991).

Rhode Island está dividido en cinco condados , pero no tiene gobiernos de condado. El estado entero está dividido en 39 municipios, que se encargan de todos los asuntos del gobierno local.

En Rhode Island hay 8 ciudades y 31 pueblos. Los principales centros de población actuales son el resultado de factores históricos; el desarrollo se produjo predominantemente a lo largo de los ríos Blackstone , Seekonk y Providence con la llegada del molino impulsado por agua. Providence es la base de una gran área metropolitana.

Los 19 municipios más grandes del estado clasificados por población son: [80]

Algunas de las ciudades y pueblos de Rhode Island están divididos en aldeas, al igual que muchos otros estados de Nueva Inglaterra. Entre las aldeas más notables se encuentran Kingston, en la ciudad de South Kingstown, que alberga la Universidad de Rhode Island; Wickford, en la ciudad de North Kingstown, sede de un festival internacional de arte anual; y Wakefield , donde se encuentra el Ayuntamiento de la ciudad de South Kingstown. [81]

El edificio del capitolio estatal está construido en mármol blanco georgiano. En su parte superior se encuentra la cuarta cúpula de mármol autoportante más grande del mundo. [82] Alberga la Carta de Rhode Island otorgada por el rey Carlos II en 1663, la Carta de la Universidad Brown y otros tesoros estatales.

La Primera Iglesia Bautista de Providencia es la iglesia bautista más antigua de América, fundada por Roger Williams en 1638.

La primera oficina de correos totalmente automatizada del país se encuentra en Providence. Hay muchas mansiones históricas en la ciudad costera de Newport, incluidas The Breakers , Marble House y Belcourt Castle . También está la Sinagoga Touro , inaugurada el 2 de diciembre de 1763, considerada por los lugareños como la primera sinagoga de los Estados Unidos (consulte a continuación la información sobre la reivindicación de la ciudad de Nueva York) y que todavía está en funcionamiento. La sinagoga muestra las libertades religiosas establecidas por Roger Williams, así como una arquitectura impresionante en una mezcla del estilo colonial clásico y sefardí. El Newport Casino es un complejo de edificios declarado Monumento Histórico Nacional que alberga el Salón Internacional de la Fama del Tenis y cuenta con un activo club de tenis con cancha de césped.

La ruta panorámica 1A (conocida localmente como Ocean Road) se encuentra en Narragansett . " The Towers " también se encuentra en Narragansett y cuenta con un gran arco de piedra. Alguna vez fue la entrada a un famoso casino de Narragansett que se incendió en 1900. The Towers ahora sirve como lugar de eventos y alberga a la Cámara de Comercio local, que opera un centro de información turística.

Se ha planteado la hipótesis de que la Torre Newport es de origen vikingo , aunque la mayoría de los expertos creen que era un molino de viento de la época colonial. [83]

El 29 de mayo de 2014, el gobernador Lincoln D. Chafee anunció que Rhode Island era uno de los ocho estados que habían publicado un plan de acción colaborativo para poner 3,3 millones de vehículos de cero emisiones en sus carreteras para 2025. El objetivo del plan es reducir las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero y de esmog. El plan promueve los vehículos de cero emisiones y las inversiones en la infraestructura para apoyarlos. [85]

En 2014, Rhode Island recibió subvenciones por valor de 2.711.685 dólares de la Agencia de Protección Ambiental para limpiar zonas industriales abandonadas en ocho lugares. Las subvenciones proporcionaron a las comunidades fondos para evaluar, limpiar y rehabilitar propiedades contaminadas, impulsar las economías locales y generar empleos, al tiempo que se protege la salud pública y el medio ambiente. [86]

En 2013, se creó el programa "Lots of Hope" en la ciudad de Providence para centrarse en aumentar los espacios verdes de la ciudad y la producción local de alimentos, mejorar los barrios urbanos, promover estilos de vida saludables y mejorar la sostenibilidad ambiental. Con el apoyo de una subvención de 100.000 dólares, el programa se asociará con la ciudad de Providence, el Southside Community Land Trust y la Rhode Island Foundation para convertir los terrenos baldíos de propiedad municipal en granjas urbanas productivas. [87]

En 2012, Rhode Island aprobó el proyecto de ley S2277/H7412, "Ley relativa a la salud y la seguridad: objetivos de limpieza ambiental para las escuelas", conocido informalmente como el proyecto de ley de ubicación de escuelas. Patrocinado por el senador Juan Pichardo y el representante Scott Slater , y promulgado por el gobernador, convirtió a Rhode Island en el primer estado de los EE. UU. en prohibir la construcción de escuelas en sitios contaminados donde los vapores tóxicos pueden afectar potencialmente la calidad del aire interior. También crea un proceso de participación pública siempre que una ciudad o pueblo considere construir una escuela en cualquier otro tipo de sitio contaminado. [88]

ElEl Atlas de plantas invasoras de Nueva Inglaterra monitorea las malezas invasoras en toda Nueva Inglaterra. [89]

En el censo de EE. UU. de 2020 , la población de Rhode Island era de 1.097.379. El centro de población de Rhode Island se encuentra en el condado de Providence , en la ciudad de Cranston . [91] Se puede ver un corredor de población desde el área de Providence, que se extiende hacia el noroeste siguiendo el río Blackstone hasta Woonsocket , donde los molinos del siglo XIX impulsaron la industria y el desarrollo.

Según el Informe Anual de Evaluación de Personas sin Hogar de 2022 del HUD , se estima que había 1.577 personas sin hogar en Rhode Island. [92] [93]

Según el censo de 2020, el 71,3% de la población era blanca (68,7% blanca no hispana ), el 5,7% era negra o afroamericana, el 0,7% indígena americana y nativa de Alaska, el 3,6% asiática, el 0,0% nativa hawaiana y de otras islas del Pacífico, el 9,4% de alguna otra raza y el 9,3% de dos o más razas. El 16,6% de la población total era de origen hispano o latino (pueden ser de cualquier raza). [94]

De las personas que residen en Rhode Island, el 58,7% nació en Rhode Island, el 26,6% nació en un estado diferente, el 2,0% nació en Puerto Rico, áreas insulares de EE. UU. o nació en el extranjero de padres estadounidenses, y el 12,6% nació en el extranjero. [100]

Según la Oficina del Censo de los Estados Unidos, en 2015 [update], Rhode Island tenía una población estimada de 1.056.298 habitantes, lo que supone un aumento de 1.125, o 0,10%, respecto del año anterior y un aumento de 3.731, o 0,35%, desde el año 2010. Esto incluye un aumento natural desde el último censo de 15.220 personas (es decir, 66.973 nacimientos menos 51.753 muertes) y un aumento debido a la migración neta de 14.001 personas al estado. La inmigración desde fuera de los Estados Unidos resultó en un aumento neto de 18.965 personas, y la migración dentro del país produjo una disminución neta de 4.964 personas. En 2018, los principales países de origen de los inmigrantes de Rhode Island fueron República Dominicana , Guatemala , Portugal , Cabo Verde e India . [101]

Los hispanos en el estado representan el 12,8% de la población, predominantemente dominicana, puertorriqueña y guatemalteca. [102] Rhode Island tiene el porcentaje más alto de dominicanos estadounidenses en el país con un 5,1% según las últimas estimaciones, lo que coloca al estado en la sexta comunidad dominicana más grande del país. [96]

Según el censo de Estados Unidos de 2000 , el 84% de la población de 5 años o más hablaba solo inglés americano , mientras que el 8,07% hablaba español en casa, el 3,80% portugués, el 1,96% francés, el 1,39% italiano y el 0,78% hablaba otros idiomas en casa. [103]

El grupo étnico más numeroso del estado, los blancos no hispanos, ha disminuido del 96,1% en 1970 al 76,5% en 2011. [102] [104] En 2011, el 40,3% de los niños de Rhode Island menores de un año pertenecían a grupos raciales o étnicos minoritarios, lo que significa que tenían al menos un padre que no era blanco no hispano. [105]

El 6,1% de la población de Rhode Island tenía menos de 5 años, el 23,6% menos de 18 años y el 14,5% tenía 65 años o más. Las mujeres representaban aproximadamente el 52% de la población.

Según la Encuesta sobre la comunidad estadounidense de 2010-2015 , los grupos de ascendencia más numerosos eran los irlandeses (18,3 %), los italianos (18,0 %), los ingleses (10,5 %), los franceses (10,4 %) y los portugueses (9,3 %). [100] Rhode Island tiene algunos de los porcentajes más altos de estadounidenses de origen irlandés y estadounidense de origen italiano. [106] Los estadounidenses de origen italiano constituyen una pluralidad en el centro y el sur del condado de Providence y los estadounidenses francocanadienses forman una gran parte del norte del condado de Providence. Los estadounidenses de origen irlandés tienen una fuerte presencia en los condados de Newport y Kent. Los estadounidenses de ascendencia inglesa todavía tienen presencia en el estado también, especialmente en el condado de Washington , y a menudo se les conoce como " yanquis del pantano ".

Rhode Island tiene una notable comunidad lusófona, con un mayor porcentaje de estadounidenses de ascendencia portuguesa que cualquier otro estado, incluidos los estadounidenses de origen portugués y los estadounidenses de Cabo Verde . Además, el estado también tiene el mayor porcentaje de inmigrantes liberianos , con más de 15.000 residentes en el estado. [107] Los inmigrantes africanos, incluidos los de Cabo Verde y Liberia, forman comunidades significativas y en crecimiento en Rhode Island. Rhode Island es uno de los pocos estados donde las personas negras de origen extranjero reciente superan en número a las personas negras de origen estadounidense multigeneracional (afroamericanos). [106] Rhode Island también tiene una comunidad asiática considerable. Hay una tribu reconocida federalmente en Rhode Island, la tribu india Narragansett.

Aunque Rhode Island tiene la superficie terrestre más pequeña de los 50 estados, tiene la segunda densidad de población más alta , después de la de Nueva Jersey.

Una encuesta de Pew sobre la autoidentificación religiosa de los residentes de Rhode Island en 2014 mostró la siguiente distribución de afiliaciones: católicos 42%, protestantes 30%, judíos 1%, testigos de Jehová 2%, budismo 1%, mormonismo 1%, hinduismo 1% y no religiosos 20%. [118] Las denominaciones cristianas más grandes en 2010 fueron la Iglesia Católica con 456.598 seguidores, la Iglesia Episcopal con 19.377, las Iglesias Bautistas Americanas de EE. UU. con 15.220 y la Iglesia Metodista Unida con 6.901 seguidores. [119]

Según un estudio realizado en 2000, Rhode Island ha tenido la mayor proporción de residentes católicos de todos los estados, [120] debido principalmente a la gran inmigración irlandesa, italiana y francocanadiense en el pasado; recientemente, también se han establecido en el estado importantes comunidades portuguesas y varias comunidades hispanas o latinas. Aunque tiene el porcentaje general de católicos más alto de todos los estados, ninguno de los condados de Rhode Island se encuentra entre los 10 más católicos de los Estados Unidos, ya que los católicos están distribuidos uniformemente en todo el estado.

Según el Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), en 2020, el 67% de la población era cristiana, repartida entre el protestantismo evangélico y tradicional , y el catolicismo romano. [121] En 2022, el Public Religion Research Institute reveló que el 72% de la población era cristiana. [122]

La comunidad judía de Rhode Island, centrada en la zona de Providence, surgió durante una ola de inmigración judía predominantemente de shtetls de Europa del Este entre 1880 y 1920. La presencia de la sinagoga Touro en Newport, la sinagoga más antigua que aún existe en los Estados Unidos, pone de relieve que estos inmigrantes de segunda ola no crearon la primera comunidad judía de Rhode Island; una ola comparativamente más pequeña de judíos españoles y portugueses inmigró a Newport durante la era colonial. En 2022, constituían el 2% de la población del estado. [122]

Desde 2014, los no afiliados a ninguna religión representaban el 20% de la población, aunque un estudio independiente del Instituto de Investigación de Religión Pública determinó que los irreligiosos aumentaron al 29% de la población adulta. [121] En 2022, los no afiliados a ninguna religión disminuyeron al 24% de la población. [122]

En la actualidad, muchos habitantes de Rhode Island se identifican como nativos americanos únicamente (6.058 personas en el censo de 2010 y 7.385 en 2020) o nativos americanos en combinación con una o más razas (8.336 personas en el censo de 2010 y 15.972 en 2020). [123] Muchos habitantes de Rhode Island también declararon pertenecer a tribus en el censo de 2010, las más numerosas de las cuales eran los narragansett (2.820 personas), los cherokee (987), los wampanoag (559) y los pequot (424). Otras tribus incluían a los iroqueses (278), los micmac (101), los abenaki (100), los nipmuc (99) y más. [124]

La economía de Rhode Island tenía una base colonial en la pesca.

El valle del río Blackstone contribuyó de manera importante a la Revolución Industrial estadounidense . Fue en Pawtucket donde Samuel Slater estableció Slater Mill en 1793, [126] utilizando la energía hidráulica del río Blackstone para alimentar su fábrica de algodón . Durante un tiempo, Rhode Island fue uno de los líderes en textiles. Sin embargo, con la Gran Depresión , la mayoría de las fábricas textiles se trasladaron a los estados del sur de EE. UU. La industria textil todavía constituye una parte de la economía de Rhode Island, pero no tiene el mismo poder.

Otras industrias importantes en el pasado de Rhode Island incluyeron la fabricación de herramientas, la bisutería y la platería . Un subproducto interesante de la historia industrial de Rhode Island es la cantidad de fábricas abandonadas, muchas de las cuales ahora son condominios, museos, oficinas y viviendas para personas de bajos ingresos y personas mayores. Hoy, gran parte de la economía de Rhode Island se basa en los servicios, en particular la atención médica y la educación, y todavía en la fabricación en cierta medida. [127] La historia náutica del estado continúa en el siglo XXI en forma de construcción de submarinos nucleares .

Según la Encuesta sobre Comunidades Estadounidenses de 2013, Rhode Island tiene los maestros de escuela primaria mejor pagados del país, con un salario promedio de $75,028 (ajustado a la inflación). [128]

La sede de Citizens Financial Group , el decimocuarto banco más grande de los Estados Unidos, está en Providence . [129] Las empresas Fortune 500 CVS Caremark y Textron tienen su sede en Woonsocket y Providence, respectivamente. FM Global , GTECH Corporation , Hasbro , American Power Conversion , Nortek y Amica Mutual Insurance son todas empresas Fortune 1000 con sede en Rhode Island. [130]

La producción estatal bruta total de Rhode Island en 2000 fue de $46,18 mil millones (ajustada a la inflación), lo que lo colocó en el puesto 45 del país. Su ingreso personal per cápita en 2000 fue de $41,484 (ajustado a la inflación), el 16.º del país. Rhode Island tiene el nivel más bajo de consumo de energía per cápita de todos los estados. [131] [132] [133] Además, Rhode Island está clasificado como el quinto estado más eficiente energéticamente del país. [134] [135] En diciembre de 2012, la tasa de desempleo del estado era del 10,2%. [136] Esta tasa se ha reducido gradualmente hasta el 3,5% en noviembre de 2019, pero la pandemia del coronavirus llevó la tasa de desempleo a un máximo del 18,1% en abril de 2020. Desde entonces, se ha reducido al 10,5% en septiembre de 2020 y se prevé que siga disminuyendo hasta el 7% en octubre de 2020. [137] [138]

Los servicios de salud son la industria más grande de Rhode Island. En segundo lugar se encuentra el turismo, que sustenta 39.000 puestos de trabajo, con ventas relacionadas con el turismo de 4.560 millones de dólares (ajustadas a la inflación) en el año 2000. La tercera industria más grande es la manufactura. [139] Sus productos industriales son la construcción de submarinos, la construcción naval, la bisutería, los productos metálicos fabricados, el equipo eléctrico, la maquinaria y la construcción de barcos. Los productos agrícolas de Rhode Island son el material de vivero, las verduras, los productos lácteos y los huevos. El producto individual más grande es la leche , que en 2017 totalizó 4.563.000 dólares en ventas. [140]

Los impuestos de Rhode Island eran considerablemente más altos que los de los estados vecinos, [141] porque el impuesto a la renta de Rhode Island se basaba en el 25% del pago de impuestos federales a la renta del contribuyente. [142] El exgobernador Donald Carcieri afirmó que la tasa impositiva más alta tenía un efecto inhibidor sobre el crecimiento empresarial en el estado y pidió reducciones para aumentar la competitividad del entorno empresarial del estado. En 2010, la Asamblea General de Rhode Island aprobó una nueva estructura de impuestos a la renta estatal que el gobernador Carcieri convirtió en ley el 9 de junio de 2010. [143] La reforma del impuesto a la renta ha hecho que Rhode Island sea competitivo con otros estados de Nueva Inglaterra al reducir su tasa impositiva máxima al 5,99% y reducir el número de tramos impositivos a tres. [144] El primer impuesto a la renta del estado se promulgó en 1971. [145]

A partir de marzo de 2011 [update], los empleadores más importantes de Rhode Island (excluidos los empleados de los municipios) son: [146]

La Autoridad de Tránsito Público de Rhode Island (RIPTA) opera el transporte de autobuses interurbanos y dentro de la ciudad en todo el estado desde sus centros en Kennedy Plaza en Providence, Pawtucket y Newport . Las rutas de autobús de RIPTA brindan servicio a 38 de las 39 ciudades y pueblos de Rhode Island. ( New Shoreham en Block Island no recibe servicio). RIPTA opera 58 rutas, incluido el servicio de tranvía diurno (que utiliza réplicas de autobuses estilo tranvía) en Providence y Newport.

Desde 2000 hasta 2008, RIPTA ofreció un servicio de ferry estacional que unía Providence y Newport (ya conectadas por autopista) financiado con dinero de subvención del Departamento de Transporte de los Estados Unidos . Aunque el servicio era popular entre los residentes y los turistas, RIPTA no pudo continuar después de que terminara la financiación federal. El servicio se interrumpió a partir de 2010. [update][ 148] El servicio se reanudó en 2016 y ha tenido éxito. El ferry privado Block Island [149] une Block Island con Newport y Narragansett con un servicio de ferry tradicional y rápido, mientras que el ferry Prudence Island [150] conecta Bristol con Prudence Island . Los servicios de ferry privados también unen varias comunidades de Rhode Island con puertos en Connecticut , Massachusetts y Nueva York.

La línea Providence/Stoughton del tren de cercanías MBTA une Providence y el aeropuerto TF Green con la estación sur de Boston , con una parada intermedia en Pawtucket/Central Falls y varias estaciones en Massachusetts. La línea se extendió más tarde hacia el sur hasta Wickford Junction , y el servicio comenzó el 23 de abril de 2012. El estado espera extender la línea MBTA hasta Kingston y Westerly , así como explorar la posibilidad de extender la línea Shore Line East de Connecticut hasta el aeropuerto TF Green. [151] El Acela Express de Amtrak para en la estación Providence (la única parada de Acela en Rhode Island), uniendo Providence con otras ciudades en el Corredor Noreste . El servicio regional del noreste de Amtrak hace paradas en la estación Providence , Kingston y Westerly .

El aeropuerto principal de Rhode Island para transporte de pasajeros y carga es el Aeropuerto TF Green en Warwick , aunque los habitantes de Rhode Island que desean viajar internacionalmente en vuelos directos y aquellos que buscan una mayor disponibilidad de vuelos y destinos a menudo vuelan a través del Aeropuerto Internacional Logan en Boston.

La Interestatal 95 (I-95) corre de suroeste a noreste a través del estado, conectando Rhode Island con otros estados a lo largo de la Costa Este . La I-295 funciona como una circunvalación parcial que rodea Providence al oeste. La I-195 proporciona una conexión de autopista de acceso limitado desde Providence (y Connecticut y Nueva York a través de la I-95) a Cape Cod. Inicialmente construida como el enlace más oriental en la extensión (ahora cancelada) de la I-84 desde Hartford, Connecticut , una parte de la Ruta 6 de EE. UU. (US 6) a través del norte de Rhode Island es de acceso limitado y conecta la I-295 con el centro de Providence.

Varias autopistas de Rhode Island extienden la red de autopistas de acceso limitado del estado. La Ruta 4 es una importante autopista de norte a sur que une Providence y Warwick (a través de la I-95) con comunidades suburbanas y de playa a lo largo de la bahía de Narragansett . La Ruta 10 es un conector urbano que une el centro de Providence con Cranston y Johnston . La Ruta 37 es una importante autopista de este a oeste que pasa por Cranston y Warwick y une la I-95 con la I-295. La Ruta 99 une Woonsocket con Providence (a través de la Ruta 146 ). La Ruta 146 pasa por el Valle Blackstone , uniendo Providence y la I-95 con Worcester, Massachusetts y la autopista de peaje de Massachusetts . La Ruta 403 une la Ruta 4 con Quonset Point .

Varios puentes cruzan la bahía Narragansett y conectan la isla Aquidneck y la isla Conanicut con el continente, entre los que destacan el puente Claiborne Pell Newport y el puente Jamestown-Verrazano .

The East Bay Bike Path stretches from Providence to Bristol along the eastern shore of Narragansett Bay, while the Blackstone River Bikeway will eventually link Providence and Worcester. In 2011, Rhode Island completed work on a marked on-road bicycle path through Pawtucket and Providence, connecting the East Bay Bike Path with the Blackstone River Bikeway, completing a 33.5 miles (54 km) bicycle route through the eastern side of the state.[152] The William C. O'Neill Bike Path (commonly known as the South County Bike Path) is an 8 mi (13 km) path through South Kingstown and Narragansett. The 19 mi (31 km) Washington Secondary Bike Path stretches from Cranston to Coventry, and the 2 mi (3.2 km) Ten Mile River Greenway path runs through East Providence and Pawtucket.

In late 2019, the Rhode Island Public Transit Authority released a draft of the Rhode Island Transit Master Plan, documenting and describing a variety of proposed improvements and additions to be made to the state's public transit network by 2040. Several different proposals were offered and still under consideration as of December 2020,[153] including implementation of a bus rapid transit system, express bus routes, expansion of Amtrak and MBTA services throughout the state, and construction of a new light rail network through downtown Providence.[153][154]

Rhode Island has several colleges and universities:

Some Rhode Islanders speak with the distinctive, non-rhotic, traditional Rhode Island accent linguists describe as a cross between New York City and Boston accents (e.g., "water" sounds like "watuh" [ˈwɔəɾə]).[156] Many Rhode Islanders distinguish a strong aw sound [ɔə] (i.e., resist the cot–caught merger of Boston) much like one might hear in New Jersey or New York City; for example, the word coffee is pronounced [ˈkʰɔəfi].[157] Rhode Islanders sometimes refer to drinking fountains as "bubblers", milkshakes as "cabinets", and overstuffed foot-long sandwiches (of whatever kind) as "grinders".[158]

Rhode Island, like the rest of New England, has a tradition of clam chowder. Both the white New England and the red Manhattan varieties are popular, but there is also a unique clear-broth chowder known as Rhode Island Clam Chowder available in many restaurants. A culinary tradition in Rhode Island is the clam cake (also known as a clam fritter outside of Rhode Island), a deep fried ball of buttery dough with chopped bits of clam inside. They are sold by the half-dozen or dozen in most seafood restaurants around the state, and the quintessential summer meal in Rhode Island is chowder and clam cakes.

The quahog is a large local clam usually used in a chowder. It is also ground and mixed with stuffing or spicy minced sausage, and then baked in its shell to form a stuffie. Calamari (squid) is sliced into rings and fried as an appetizer in most Italian restaurants, typically served Sicilian-style with sliced banana peppers and marinara sauce on the side. (In 2014, calamari became the official state appetizer.[159]) Clams Casino originated in Rhode Island, invented by Julius Keller, the maître d' in the original Casino next to the seaside Towers in Narragansett.[160] Clams Casino resemble the beloved stuffed quahog but are generally made with the smaller littleneck or cherrystone clam and are unique in their use of bacon as a topping.

The official state drink of Rhode Island is coffee milk,[161] a beverage created by mixing milk with coffee syrup. This unique syrup was invented in the state and is sold in almost all Rhode Island supermarkets, as well as its bordering states. Johnnycakes have been a Rhode Island staple since Colonial times, made with corn meal and water then pan-fried much like pancakes.

Submarine sandwiches are called grinders throughout Rhode Island, and the Italian grinder, made with cold cuts such as ham, prosciutto, capicola, salami, and Provolone cheese, is especially popular. Linguiça or chouriço is a spicy Portuguese sausage often served with peppers and eaten with hearty bread.

The Farrelly brothers and Seth MacFarlane depict Rhode Island in popular culture, often making comedic parodies of the state. MacFarlane's television series Family Guy is based in a fictional Rhode Island city named Quahog, and notable local events and celebrities are regularly lampooned. Peter Griffin is seen working at the Pawtucket brewery, and other state locations are mentioned.

The 1956 film High Society (starring Bing Crosby, Grace Kelly, and Frank Sinatra) was set in Newport, Rhode Island.

The 1974 film adaptation of The Great Gatsby was also filmed in Newport.

Jacqueline Bouvier and John F. Kennedy were married at St. Mary's church in Newport. Their reception took place at Hammersmith Farm, the Bouvier summer home in Newport.

Cartoonist Don Bousquet, a state icon, has made a career out of Rhode Island culture, drawing Rhode Island-themed gags in The Providence Journal and Yankee magazine. These cartoons have been reprinted in the Quahog series of paperbacks (I Brake for Quahogs, Beware of the Quahog, and The Quahog Walks Among Us.) Bousquet has also collaborated with humorist and Providence Journal columnist Mark Patinkin on two books: The Rhode Island Dictionary and The Rhode Island Handbook.

The 1998 film Meet Joe Black was filmed at Aldrich Mansion in the Warwick Neck area of Warwick.

Body of Proof's first season was filmed entirely in Rhode Island.[162] The show premiered on March 29, 2011.[163]

The 2007 Steve Carell and Dane Cook film Dan in Real Life was filmed in various coastal towns in the state. The sunset scene with the entire family on the beach takes place at Napatree Point.

Jersey Shore star Pauly D filmed part of his spin-off The Pauly D Project in his hometown of Johnston.

The Comedy Central cable television series Another Period is set in Newport during the Gilded Age.

Rhode Island has been the first in a number of initiatives. The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations enacted the first law prohibiting slavery in America on May 18, 1652.[164]

The first act of armed rebellion in America against the British Crown was the boarding and burning of the Revenue Schooner HMS Gaspée in Narragansett Bay on June 10, 1772. The idea of a Continental Congress was first proposed at a town meeting in Providence on May 17, 1774. Rhode Island elected the first delegates (Stephen Hopkins and Samuel Ward) to the Continental Congress on June 15, 1774. The Rhode Island General Assembly created the first standing army in the colonies (1,500 men) on April 22, 1775. On June 15, 1775, the first naval engagement took place in the American Revolution between an American sloop commanded by Capt. Abraham Whipple and an armed tender of the British Frigate Rose. The tender was chased aground and captured. Later in June, the General Assembly created the American Navy when it commissioned the sloops Katy and Washington, armed with 24 guns and commanded by Abraham Whipple who was promoted to Commodore. Rhode Island was the first Colony to declare independence from Britain on May 4, 1776.[164]

Slater Mill in Pawtucket was the first commercially successful cotton-spinning mill with a fully mechanized power system in America and was the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution in the US.[165] The oldest Fourth of July parade in the country is still held annually in Bristol, Rhode Island. The first Baptist church in America was founded in Providence in 1638.[166] Ann Smith Franklin of the Newport Mercury was the first female newspaper editor in America (August 22, 1762).[164] Touro Synagogue is the oldest synagogue in America, founded in Newport in 1763.[164]

Pelham Street in Newport was the first in America to be illuminated by gaslight in 1806.[164] The first strike in the United States in which women participated occurred in Pawtucket in 1824.[164] Watch Hill has the nation's oldest flying horses carousel that has been in continuous operation since 1850.[164] The motion picture machine was patented in Providence on April 23, 1867.[164] The first lunch wagon in America was introduced in Providence in 1872.[164] The first nine-hole golf course in America was completed in Newport in 1890.[164] The first state health laboratory was established in Providence on September 1, 1894.[164] The Rhode Island State House was the first building with an all-marble dome to be built in the United States (1895–1901).[164] The first automobile race on a track was held in Cranston on September 7, 1896.[164] The first automobile parade was held in Newport on September 7, 1899, on the grounds of Belcourt Castle.[164]

Rhode Island is nicknamed "The Ocean State", and the nautical nature of Rhode Island's geography pervades its culture. Newport Harbor, in particular, holds many pleasure boats. In the lobby of T. F. Green, the state's main airport, is a large life-sized sailboat,[167] and the state's license plates depict an ocean wave or a sailboat.[168]

The large number of beaches in Washington County lures many Rhode Islanders south for summer vacation.[169]

The state constitution protects shore access, including swimming and gathering of seaweed.[170][171] The 1982 Rhode Island Supreme Court decision in State v. Ibbison[172][173] defines the end of private land as the mean high tide line, which is difficult to determine in day-to-day activities, and has resulted in beach access conflicts.[174] Underfunding of the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council has resulted in lax enforcement against encroachment on public access and building of illegal structures.[175]

The state was notorious for organized crime activity from the 1950s into the 1990s when the Patriarca crime family held sway over most of New England from its Providence headquarters.

Rhode Islanders developed a unique style of architecture in the 17th century called the stone-ender.[176]

Rhode Island is the only state to still celebrate Victory over Japan Day, which is officially named "Victory Day" but is sometimes referred to as "VJ Day".[177] It is celebrated on the second Monday in August.[178]

Nibbles Woodaway, more commonly referred to as "The Big Blue Bug", is a 58-foot-long termite mascot for a Providence extermination business. Since its construction in 1980, it has been featured in several movies and television shows, and has come to be recognized as a cultural landmark by many locals.[179] In more recent times, the Big Blue Bug has been given a mask to remind locals and visitors to mask-up during the COVID-19 pandemic.[180]

Rhode Island is currently home to two professional minor league teams, one being the Providence Bruins ice hockey team of the American Hockey League, who are a top-level minor league affiliate of the Boston Bruins. They play in the Amica Mutual Pavilion in Providence and won the AHL's Calder Cup during the 1998–99 AHL season. The other is Rhode Island FC, a soccer team that began competing in the second tier USL Championship in 2024 at Beirne Stadium located within Bryant University, awaiting the completion of the soccer-specific Tidewater Stadium in Pawtucket in time for the 2025 season.

The Pawtucket Red Sox baseball team was a Triple-A International League affiliate of the Boston Red Sox from 1973 to 2020. They played at McCoy Stadium in Pawtucket and had won four league titles, the Governors' Cup, in 1973, 1984, 2012, and 2014. McCoy Stadium also has the distinction of being home to the longest professional baseball game ever played – 33 innings.

The Providence Reds were a hockey team that played in the Canadian-American Hockey League (CAHL) from 1926 to 1936, and the American Hockey League (AHL) from 1936 to 1977, the last season of which they played as the Rhode Island Reds. The team won the Calder Cup in 1938, 1940, 1949, and 1956. The Reds played at the Rhode Island Auditorium, on North Main Street in Providence, Rhode Island from 1926 through 1972, when the team affiliated with the New York Rangers and moved into the newly built Providence Civic Center. The team name came from the state bird, a rooster known as the Rhode Island Red. They moved to New York in 1977, then to Connecticut in 1997, and are now called the Hartford Wolf Pack.

The Reds are the oldest continuously operating minor-league hockey franchise in North America, having fielded a team in one form or another since 1926 in the CAHL. It is also the only AHL franchise to have never missed a season. The AHL returned to Providence in 1992 in the form of the Providence Bruins.

Before the great expansion of athletic teams all over the country, Providence and Rhode Island in general played a great role in supporting teams. The Providence Grays won the first World Championship in baseball history in 1884. The team played their home games at the old Messer Street Field in Providence. The Grays played in the National League from 1878 to 1885. They defeated the New York Metropolitans of the American Association in a best of five-game series at the Polo Grounds in New York. Providence won three straight games to become the first champions in major league baseball history. Babe Ruth played for the minor league Providence Grays of 1914 and hit his only official minor league home run for them before the Grays' parent club, the Boston Red Stockings, recalled him.

Rhode Island has deep history with the sport of soccer where the sport was played as early as 1886 when the state's first organized league would be founded, known as the Rhode Island Football Association (RIFA). One of their teams, the Pawtucket Free Wanderers, would establish themselves as a regional power and win the American Cup in 1893. The first championship game of the U.S. Open Cup was also held in 1914 in Pawtucket's Coates Field to a crowd of 10,000. Later, a team known as Pawtucket Rangers F.C. would win the 1941 edition of the U.S. Open Cup (then National Challenge Cup). The Rhode Island Oceaneers would later be founded, and went on to win the 1974 American Soccer League championship. Other former semiprofessional soccer teams of the modern era include the Rhode Island Stingrays of the USL Premier Development League, and the Rhode Island Reds of the National Premier Soccer League, with both leagues regarded as the fourth tier of American soccer.

The now-defunct professional football team known as the Providence Steamrollers won the 1928 NFL title. They played in a 10,000 person stadium called the Cycledrome.[181] An unrelated basketball team also known as the Providence Steamrollers played in the Basketball Association of America, which would become the National Basketball Association.

Rhode Island's only rugby league team was the Rhode Island Rebellion, a semi-professional team that was a founding member of the USA Rugby League, which was at the time the top competition in the United States for the sport of rugby league.[182][183] The Rebellion played their home games at Classical High School in Providence.[184]

There are four NCAA Division I schools in Rhode Island. All four schools compete in different conferences. The Brown University Bears compete in the Ivy League, the Bryant University Bulldogs compete in the America East Conference, the Providence College Friars compete in the Big East Conference, and the University of Rhode Island Rams compete in the Atlantic 10 Conference. Three of the schools' football teams compete in the Football Championship Subdivision, the second-highest level of college football in the United States. Brown plays FCS football in the Ivy League, Bryant plays FCS football in the Big South Conference before that league merges its football operations with those of the Ohio Valley Conference in 2023, and Rhode Island plays FCS football in CAA Football, the technically separate football league of the Colonial Athletic Association. All four Division I schools in the state compete in an intrastate all-sports competition known as the Ocean State Cup, with Bryant winning the most recent cup in 2011–12 academic year.

From 1930 to 1983, America's Cup races were sailed off Newport, and the extreme-sport X Games and Gravity Games were founded and hosted in the state's capital city.

The International Tennis Hall of Fame is in Newport at the Newport Casino, site of the first U.S. National Championships in 1881. The Hall of Fame and Museum were established in 1954 by Jimmy Van Alen as "a shrine to the ideals of the game".[185][186]

Rhode Island is also home to the headquarters of the governing body for youth rugby league in the United States, the American Youth Rugby League Association or AYRLA. The AYRLA has started the first-ever Rugby League youth competition in Providence Middle Schools, a program at the RI Training School, in addition to starting the first High School Competition in the US in Providence Public High School.[187]

The capital of Rhode Island is Providence. The state's governor is Daniel McKee (D), and the lieutenant governor is Sabina Matos (D). Gina Raimondo became Rhode Island's first female governor with a plurality of the vote in the November 2014 state elections.[189] Its United States senators are Jack Reed (D) and Sheldon Whitehouse (D). Rhode Island's two United States representatives are Gabe Amo (D-1) and Seth Magaziner (D-2). See congressional districts map. Rhode Island is one of a few states that do not have an official governor's residence. See List of Rhode Island Governors.

The state legislature is the Rhode Island General Assembly, consisting of the 75-member House of Representatives and the 38-member Senate. The Democratic Party dominates both houses of the bicameral body; the Republican Party's presence is minor in the state government, with Republicans holding a handful of seats in both the Senate and House of Representatives.

Rhode Island's population barely crosses the threshold beyond the minimum of three for additional votes in both the federal House of Representatives and Electoral College; it is well represented relative to its population, with the eighth-highest number of electoral votes and second-highest number of House Representatives per resident. Based on its area, Rhode Island has the highest density of electoral votes of any state.[191]

Federally, Rhode Island is a reliably Democratic state during presidential elections, usually supporting the Democratic presidential nominee. The state voted for the Republican presidential candidate until 1908. Since then, it has voted for the Republican nominee for president seven times, and the Democratic nominee 17 times. The last 16 presidential elections in Rhode Island have resulted in the Democratic Party winning the Ocean State's Electoral College votes 12 times. In the 1980 presidential election, Rhode Island was one of six states to vote against Republican Ronald Reagan. Reagan was the last Republican to win any of the state's counties in a Presidential election until Donald Trump won Kent County in 2016. In 1988, George H. W. Bush won over 40% of the state's popular vote, something no Republican has done since.

Rhode Island was the Democrats' leading state in 1960, 1964, 1968, 1988 and 2000, and second-best in 1968, 1972, 1996, and 2004. Rhode Island's most one-sided Presidential election result was in 1964, with over 80% of Rhode Island's votes going for Lyndon B. Johnson. In 2004, Rhode Island gave John Kerry more than a 20-percentage-point margin of victory (the third-highest of any state), with 59.4% of its vote. All but three of Rhode Island's 39 cities and towns voted for the Democratic candidate. The exceptions were East Greenwich, West Greenwich, and Scituate.[192] In 2008, Rhode Island gave Barack Obama a 28-percentage-point margin of victory (the third-highest of any state), with 63% of its vote. All but one of Rhode Island's 39 cities and towns voted for the Democratic candidate (the exception being Scituate).[193]

In a 2020 study, Rhode Island was ranked as the 19th easiest state for citizens to vote in.[194]

Rhode Island is one of 21 states that have abolished capital punishment; it was second do so, just after Michigan, and carried out its last execution in the 1840s. Rhode Island was the second to last state to make prostitution illegal. Until November 2009 Rhode Island law made prostitution legal provided it took place indoors.[196] In a 2009 study Rhode Island was listed as the 9th safest state in the country.[197]

In 2011, Rhode Island became the third state in the United States to pass legislation to allow the use of medical marijuana. On May 25, 2022, Rhode Island fully legalized recreational use of marijuana, becoming the nineteenth state to do so.[198] Additionally, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed legislation that allowed civil unions which Governor Lincoln Chafee signed into law on July 2, 2011. Rhode Island became the eighth state to fully recognize either same-sex marriage or civil unions.[199] Same-sex marriage became legal on May 2, 2013, and took effect August 1.[200]

Rhode Island has some of the highest taxes in the country, particularly its property taxes, ranking seventh in local and state taxes, and sixth in real estate taxes.[141]

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)41°42′N 71°30′W / 41.7°N 71.5°W / 41.7; -71.5 (State of Rhode Island)