El Metro de Washington , a menudo abreviado como Metro y formalmente como Metrorail , [4] es un sistema de tránsito rápido que presta servicio en el área metropolitana de Washington en los Estados Unidos. Es administrado por la Autoridad de Tránsito del Área Metropolitana de Washington (WMATA), que también opera el servicio Metrobus bajo el nombre de Metro. [5] Inaugurada en 1976, la red ahora incluye seis líneas, 98 estaciones y 129 millas (208 km) de ruta . [6] [7]

Metro presta servicio a Washington, DC , así como a varias jurisdicciones en los estados de Maryland y Virginia . En Maryland, Metro brinda servicio a los condados de Montgomery y Prince George ; en Virginia, a los condados de Arlington , Fairfax y Loudoun , y a la ciudad independiente de Alexandria . La expansión más reciente del sistema , que es la construcción de una nueva estación (y la alteración de la línea), que da servicio a Potomac Yard , se inauguró el 19 de mayo de 2023. Opera principalmente como un metro de nivel profundo en partes más densamente pobladas del área metropolitana de DC (incluida la mayor parte del propio Distrito), mientras que la mayoría de las vías suburbanas están a nivel de la superficie o elevadas . La escalera mecánica de un solo nivel más larga del hemisferio occidental, con una extensión de 230 pies (70 m), se encuentra en la estación Wheaton de nivel profundo de Metro . [8]

En 2023, el sistema tuvo una cantidad de pasajeros de 136,303,200, o aproximadamente 576,300 por día laborable a partir del segundo trimestre de 2024, lo que lo convierte en el segundo sistema de tránsito rápido ferroviario pesado más transitado en los Estados Unidos, en número de viajes de pasajeros, después del metro de la ciudad de Nueva York , y el sexto más transitado en América del Norte. [9] En junio de 2008, Metro estableció un récord de pasajeros mensual con 19,729,641 viajes, o 798,456 por día laborable. [10] Las tarifas varían según la distancia recorrida, la hora del día y el tipo de tarjeta utilizada por el pasajero. Los pasajeros entran y salen del sistema usando una tarjeta de proximidad llamada SmarTrip .

Durante la década de 1950, se hicieron planes para un sistema masivo de autopistas en Washington, DC Harland Bartholomew , quien presidió la Comisión Nacional de Planificación de la Capital , pensó que un sistema de tránsito ferroviario nunca sería autosuficiente debido a los usos de tierra de baja densidad y la disminución general del uso del transporte público. [11] Pero el plan encontró una feroz oposición y se modificó para incluir un sistema Capital Beltway más radiales de línea ferroviaria. Beltway recibió financiación completa junto con financiación adicional del proyecto del sistema de autopistas Inner Loop que se reasignó parcialmente a la construcción del sistema de metro. [12]

En 1960, el gobierno federal creó la Agencia Nacional de Transporte de la Capital para desarrollar un sistema ferroviario rápido. [13] En 1966, el gobierno federal, el Distrito de Columbia, Virginia y Maryland aprobaron un proyecto de ley para crear la WMATA, [6] y la NCTA le transfirió el poder de planificación del sistema. [14] [15] Un mapa de propuesta inicial de 1967 era más extenso que lo que finalmente se aprobó, y la terminal occidental de la Línea Roja estaba en Germantown en lugar de Shady Grove . [16]

El 1 de marzo de 1968, la WMATA aprobó los planes para un sistema regional de 156,4 km (97,2 millas). El plan consistía en un sistema regional central, que incluía las cinco líneas originales del metro, así como varias ampliaciones futuras, muchas de las cuales no se construyeron. [17] La primera estación experimental del metro se construyó sobre el suelo en mayo de 1968 por un coste de 69.000 dólares. Tenía unas dimensiones de 19,5 m × 9,1 m × 5,2 m (64 x 30 x 17 pies) y estaba destinada a probar las técnicas de construcción, la iluminación y la acústica antes de los esfuerzos de construcción a gran escala. [18]

La construcción comenzó después de una ceremonia inaugural el 9 de diciembre de 1969, cuando el Secretario de Transporte John A. Volpe , el alcalde de distrito Walter Washington y el gobernador de Maryland Marvin Mandel arrojaron la primera palada de tierra en Judiciary Square. [19]

La primera parte del sistema se inauguró el 27 de marzo de 1976, con 4,6 millas (7,4 km) disponibles en la Línea Roja con cinco estaciones desde Rhode Island Avenue hasta Farragut North , todas en Washington, DC [20] [21] Todos los viajes fueron gratuitos ese día, y el primer tren partió de la parada de Rhode Island Avenue con funcionarios de Metro e invitados especiales, y el segundo con miembros del público en general. [22] El condado de Arlington, Virginia, se vinculó al sistema el 1 de julio de 1977; [23] el condado de Montgomery, Maryland , el 6 de febrero de 1978; [24] el condado de Prince George, Maryland , el 17 de noviembre de 1978; [25] y el condado de Fairfax, Virginia , y Alexandria, Virginia , el 17 de diciembre de 1983. [6] [26] Metro llegó al condado de Loudoun el 15 de noviembre de 2022. Las estaciones subterráneas se construyeron con arcos de hormigón tipo catedral, resaltados por una iluminación suave e indirecta. [27] El nombre Metro fue sugerido por Massimo Vignelli , quien diseñó la señalización para el sistema, así como para el metro de la ciudad de Nueva York . [28]

El sistema de 103 millas (166 km) y 83 estaciones se completó con la apertura del segmento de la Línea Verde hasta Branch Avenue el 13 de enero de 2001. Sin embargo, esto no significó el final del crecimiento del sistema. Una extensión de 3,22 millas (5,18 km) de la Línea Azul hasta Morgan Boulevard y Downtown Largo se inauguró el 18 de diciembre de 2004. La primera estación de relleno , New York Ave–Florida Ave–Gallaudet University (ahora NoMa–Gallaudet U ) en la Línea Roja entre Union Station y Rhode Island Avenue , se inauguró el 20 de noviembre de 2004. La construcción comenzó en marzo de 2009 para una extensión al Aeropuerto Dulles que se construirá en dos fases. [29] La primera fase, cinco estaciones que conectan East Falls Church con Tysons Corner y Wiehle Avenue en Reston, se inauguró el 26 de julio de 2014. [30] La segunda fase hasta Ashburn se inauguró el 15 de noviembre de 2022, después de muchos retrasos. La segunda estación de relleno, Potomac Yard en las líneas Azul y Amarilla entre Braddock Road y National Airport , se inauguró el 19 de mayo de 2023. [31]

La construcción del metro requirió miles de millones de dólares federales, originalmente provistos por el Congreso bajo la autoridad de la Ley de Transporte de la Capital Nacional de 1969. [32] El costo fue pagado con un 67% de dinero federal y un 33% de dinero local. Esta ley fue enmendada el 3 de enero de 1980, por la Enmienda de Transporte de la Capital Nacional de 1979 (también conocida como la Ley Stark-Harris), [33] que autorizó una financiación adicional de $1.7 mil millones para permitir la finalización de 89,5 millas (144,0 km) del sistema según lo previsto en los términos de un acuerdo de subvención de financiación completa ejecutado con WMATA en julio de 1986, que exigía que el 20% se pagara con fondos locales. El 15 de noviembre de 1990, las Enmiendas de Transporte de la Capital Nacional de 1990 [34] autorizaron $1.3 mil millones adicionales en fondos federales para la construcción de las 13,5 millas (21,7 km) restantes del sistema de 103 millas (166 km), completadas mediante la ejecución de acuerdos de subvención de financiación completa, con una proporción de contrapartida federal del 63% y local del 37%. [35]

En febrero de 2006, los funcionarios del Metro eligieron a Randi Miller, empleada de un concesionario de automóviles de Woodbridge, Virginia , para grabar nuevos anuncios de "puertas que se abren", "puertas que se cierran" y "por favor, manténgase alejado de las puertas, gracias" después de ganar un concurso abierto para reemplazar los mensajes grabados por Sandy Carroll en 1996. El concurso "Puertas que se cierran" atrajo a 1.259 concursantes de todo el país. [36]

Con el paso de los años, la falta de inversión en el Metro provocó su colapso y se produjeron varios incidentes fatales en el Metro de Washington debido a la mala gestión y a una infraestructura deteriorada. En 2016, según The Washington Post , las tasas de puntualidad habían caído al 84% y el servicio del Metro se interrumpía con frecuencia durante las horas pico debido a una combinación de fallas en el equipo, el material rodante, las vías y las señales. [37] WMATA no recibió fondos específicos de las tres jurisdicciones a las que prestaba servicios, Maryland, Virginia y DC, hasta 2018. [38]

En un intento por abordar las percepciones negativas sobre su desempeño, en 2016, WMATA anunció una iniciativa llamada "Back2Good", centrada en abordar una amplia gama de preocupaciones de los pasajeros, desde mejorar la seguridad hasta agregar acceso a Internet a las estaciones y túneles de trenes. [39]

En mayo de 2018, Metro anunció una renovación extensiva de las plataformas en 20 estaciones de todo el sistema, que abarcan todas las líneas excepto la Silver Line. Las líneas Azul y Amarilla al sur del Aeropuerto Nacional estuvieron cerradas del 25 de mayo al 9 de septiembre de 2019, en lo que sería el cierre de línea más largo en la historia de Metro. [40] [41] Se repararían estaciones adicionales entre 2020 y 2022, pero las líneas correspondientes no se cerrarían por completo. El proyecto costaría entre $300 y $400 millones y sería el primer proyecto importante de Metro desde su construcción. [42] [43]

En marzo de 2022, Metro anunció que a partir del 10 de septiembre de 2022 suspendería todo el servicio en la Línea Amarilla durante siete a ocho meses para completar las reparaciones y el trabajo de reconstrucción en su puente sobre el río Potomac y su túnel que conduce a la estación en L'Enfant Plaza . [44] Metro declaró que este era el primer trabajo significativo que habían experimentado el túnel y el puente desde que se construyeron por primera vez hace más de cuarenta años. [44] El servicio en la Línea Amarilla se reanudó el 7 de mayo de 2023, pero con su terminal noreste truncada desde Greenbelt hasta Mount Vernon Square . [45]

La siguiente es una lista de fechas de apertura de segmentos de vías y estaciones de relleno en el Metro de Washington. Las entradas en las columnas "desde" y "hasta" corresponden a los límites de la extensión o estación que se inauguró en la fecha especificada, no a las terminales de las líneas. [8] : 3 [46]

El 31 de diciembre de 2006, comenzó un programa piloto de 18 meses para extender el servicio de la Línea Amarilla hasta Fort Totten sobre las vías existentes de la Línea Verde. [48] [49] Esta extensión se hizo permanente más tarde. [50] A partir del 18 de junio de 2012, la Línea Amarilla se extendió nuevamente a lo largo de las vías existentes como parte del programa Rush+, con una extensión hasta Greenbelt en el extremo norte y con varios trenes desviados a Franconia–Springfield en el extremo sur. Estas extensiones Rush+ se interrumpieron el 25 de junio de 2017. [51]

Además de expandir el sistema, Metro amplió el horario de funcionamiento durante los primeros 40 años. Aunque originalmente abrió con un servicio solo de lunes a viernes de 6 a. m. a 8 p. m., los documentos financieros previos a la apertura asumieron que eventualmente operaría de 5 a. m. a 1 a. m. siete días a la semana. Nunca funcionó exactamente en ese horario, pero el horario se expandió, a veces más allá de eso. [52] El 25 de septiembre de 1978, Metro extendió su horario de cierre de lunes a viernes de 8 p. m. a medianoche y 5 días después comenzó el servicio de los sábados de 8 a. m. a medianoche. [53] [54] Metrorail inició el servicio de domingo de 10 a. m. a 6 p. m. el 2 de septiembre de 1979, y el 29 de junio de 1986, el horario de cierre del domingo se retrasó a medianoche. [55] El Metro comenzó a abrir a las 5:30 am, media hora antes, los días laborables a partir del 1 de julio de 1988. [56] El 5 de noviembre de 1999, el servicio de fin de semana se extendió a la 1:00 am, y el 30 de junio de 2000, se amplió a las 2:00 am [57] [58] El 5 de julio de 2003, el horario de fin de semana se extendió nuevamente con el sistema abriendo una hora antes, a las 7:00 am y cerrando una hora más tarde a las 3:00 am [59] El 27 de septiembre de 2004, Metro volvió a adelantar el horario de apertura de los días laborables media hora antes, esta vez a las 5 am [60]

En 2016, Metro comenzó a reducir temporalmente las horas de servicio para permitir más mantenimiento. El 3 de junio de 2016, terminaron el servicio nocturno de fin de semana y Metrorail cerró a la medianoche. [61] Los horarios se ajustaron nuevamente el año siguiente a partir del 25 de junio de 2017, con el servicio entre semana terminando media hora antes a las 11:30 p. m.; el servicio dominical se redujo para comenzar una hora más tarde, a las 8 a. m., y terminar una hora antes a las 11 p. m.; y el servicio nocturno se restableció parcialmente a la 1 a. m. El cronograma de servicio fue aprobado hasta junio de 2019. [62]

El 29 de enero de 2020, Metro anunció que activaría sus planes de respuesta a la pandemia en preparación para la inminente pandemia de COVID-19 , que sería declarada pandemia por la Organización Mundial de la Salud el 11 de marzo. En ese momento, Metro anunció que reduciría su horario de servicio de 5:00 a. m. a 9:00 p. m. de lunes a viernes y de 8:00 a. m. a 9:00 p. m. los fines de semana a partir del 16 de marzo para adaptarse a la limpieza de trenes y trabajos adicionales en las vías. [63] A partir de 2022, se han restablecido los horarios de servicio anteriores a COVID con los horarios de servicio dominicales anteriores a 2016. [64]

El mayor número de pasajeros en un solo día se registró el día de la primera investidura de Barack Obama , el 20 de enero de 2009, con 1,12 millones de pasajeros. Se rompió el récord anterior, establecido el día anterior, de 866.681 pasajeros. [65] Junio de 2008 estableció varios récords de pasajeros: el récord de pasajeros de un solo mes de 19.729.641 pasajeros en total, el récord de mayor promedio de pasajeros en un día laborable con 1.044.400 viajes entre semana, tuvo cinco de los diez días de mayor número de pasajeros y tuvo 12 días laborables en los que los pasajeros superaron los 800.000 viajes. [10] El récord del domingo de 616.324 viajes se estableció el 18 de enero de 2009, durante los eventos previos a la investidura de Obama, el día en que los Obama llegaron a Washington y ofrecieron un concierto en las escaleras del Monumento a Lincoln. Se rompió el récord establecido el 4 de julio de 1999. [66]

El 21 de enero de 2017, la Marcha de las Mujeres de 2017 estableció un récord histórico en cuanto a cantidad de pasajeros en sábado, con 1 001 616 viajes. [67] El récord anterior se estableció el 30 de octubre de 2010, con 825 437 viajes durante la manifestación para restaurar la cordura y/o el miedo . [68] Antes de 2010, el récord se había establecido el 8 de junio de 1991, con 786 358 viajes durante la manifestación Tormenta del Desierto. [69]

[70] [71]

Muchas estaciones de metro fueron diseñadas por el arquitecto de Chicago Harry Weese y son ejemplos de la arquitectura moderna de finales del siglo XX . Con su uso intensivo de hormigón visto y motivos de diseño repetitivos, las estaciones de metro muestran aspectos del diseño brutalista . Las estaciones también reflejan la influencia de la arquitectura neoclásica de Washington en sus bóvedas de techo artesonado generales . Weese trabajó con el diseñador de iluminación Bill Lam, con sede en Cambridge, Massachusetts, en la iluminación indirecta utilizada en todo el sistema. [72] [73] Todas las estaciones brutalistas originales de Metro se encuentran en el centro de Washington, DC , y los corredores urbanos vecinos de Arlington, Virginia , mientras que las estaciones más nuevas incorporan diseños simplificados y rentables. [74]

En 2007, el diseño de las estaciones con techo abovedado del Metro fue votado como el número 106 en la lista de " Arquitectura favorita de Estados Unidos " compilada por el Instituto Americano de Arquitectos (AIA), y fue el único diseño brutalista en ganar un lugar entre los 150 seleccionados por esta encuesta pública. [75]

En enero de 2014, la AIA anunció que entregaría su Premio de los Veinticinco Años al sistema de metro de Washington por "un diseño arquitectónico de importancia duradera" que "ha resistido la prueba del tiempo al encarnar la excelencia arquitectónica durante 25 a 35 años". El anuncio citó el papel clave de Weese, quien concibió e implementó un "kit de diseño común de piezas", que continúa guiando la construcción de nuevas estaciones de metro más de un cuarto de siglo después, aunque con diseños modificados ligeramente por razones de costo. [76]

A partir de 2003, se agregaron marquesinas a las salidas existentes de las estaciones subterráneas debido al desgaste que sufrían las escaleras mecánicas por la exposición a los elementos. [77]

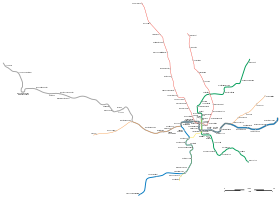

Desde su apertura en 1976, la red de metro ha crecido hasta incluir seis líneas, 98 estaciones y 129 millas (208 km) de ruta. [78] La red ferroviaria está diseñada según un paradigma de distribución radial , con líneas ferroviarias que corren entre el centro de Washington y sus suburbios cercanos. El sistema utiliza ampliamente la interconexión: ejecutar más de un servicio en la misma vía. Hay seis líneas operativas. [78] El mapa oficial del sistema fue diseñado por el destacado diseñador gráfico Lance Wyman [79] y Bill Cannan mientras eran socios en la firma de diseño Wyman & Cannan en la ciudad de Nueva York. [80]

Aproximadamente 80 km (50 millas) de vías del Metro son subterráneas, al igual que 47 de las 98 estaciones. Las vías corren subterráneas principalmente dentro del Distrito y los suburbios de alta densidad. Las vías de superficie representan aproximadamente 74 km (46 millas) del total, y las vías aéreas representan 14 km (9 millas). [78] El sistema opera en un ancho de vía de 4 pies 8 pulgadas (1,2 m).+1 ⁄ 4 pulg .(1429 mm), que es1⁄4pulg. (6,4 mm) más angosto que4 pies 8 pulg.+Ancho de vía estándar de 1 ⁄ 2 pulgada(1435 mm),pero dentro de la tolerancia delos ferrocarriles de ancho estándar.[81]

Anteriormente, el tiempo mínimo para viajar a través de 97 estaciones utilizando solo transporte público era de 8 horas y 54 minutos, un récord establecido por el bloguero de viajes Lucas Wall el 16 de noviembre de 2022, el primer día completo en que la Fase 2 de la Silver Line estuvo en operación de pasajeros. [82] Este récord fue batido por una estudiante llamada Claire Aguayo, quien lo hizo en 8 horas y 36 minutos el 23 de enero de 2023. [83] Ambos recorridos fueron antes de que se abriera la estación Potomac Yard el 19 de mayo de 2023, por lo que ya no están vigentes.

Para obtener ingresos, la WMATA ha comenzado a permitir negocios minoristas en estaciones de metro. La WMATA ha autorizado máquinas expendedoras de alquiler de DVD y taquillas para los recorridos en tranvía por el casco antiguo y está buscando inquilinos minoristas adicionales. [84]

Metro depende en gran medida de las tarifas de pasajeros y de la financiación apropiada de los gobiernos de Maryland , Virginia y Washington DC , que están representados en la junta directiva de Metro. En 2018, Maryland, Virginia y Washington, DC, acordaron contribuir con $500 millones anuales al presupuesto de capital de Metro. [38] Hasta entonces, el sistema no tenía un flujo de ingresos dedicado como los sistemas de transporte masivo de otras ciudades. Los críticos alegan que esto ha contribuido a la historia reciente de Metro de problemas de mantenimiento y seguridad. [86] [37]

Para el año fiscal 2019, la tasa estimada de recuperación de tarifas (ingresos por tarifas divididos por gastos operativos) fue del 62 por ciento, según el presupuesto aprobado por WMATA. [87]

.JPG/440px-Gallery_Place_(WMATA_station).JPG)

Hay 40 estaciones en el Distrito de Columbia, 15 en el condado de Prince George, 13 en el condado de Fairfax, 11 en el condado de Montgomery, 11 en el condado de Arlington, 5 en la ciudad de Alexandria y 3 en el condado de Loudoun. [78] La estación más reciente se inauguró el 19 de mayo de 2023, una estación de relleno en Potomac Yard . [31] A 196 pies (60 m) debajo de la superficie, la estación Forest Glen en la Línea Roja es la más profunda del sistema. No hay escaleras mecánicas; los ascensores de alta velocidad tardan 20 segundos en viajar desde la calle hasta el andén de la estación. La estación Wheaton , una parada al norte de la estación Forest Glen, tiene la escalera mecánica continua más larga de los EE. UU. y del hemisferio occidental , a 230 pies (70 m). [78] [88] La estación Rosslyn es la estación más profunda de la Línea Naranja/Azul/Plata, a 117 pies (36 m) por debajo del nivel de la calle. La estación cuenta con la segunda escalera mecánica continua más larga del sistema de metro, a 194 pies (59 m); un viaje en escalera mecánica entre los niveles de la calle y el entrepiso lleva casi dos minutos. [89]

El sistema no está centrado en ninguna estación en particular, sino que Metro Center está en la intersección de las líneas Roja, Naranja, Azul y Plateada. [90] La estación también es la ubicación de la oficina de ventas principal de WMATA, que cerró en 2022. Metro ha designado otras cinco "estaciones centrales" que tienen un alto volumen de pasajeros, entre ellas: [91] Gallery Place , estación de transferencia para las líneas Roja, Verde y Amarilla; L'Enfant Plaza , estación de transferencia para las líneas Naranja, Azul, Plateada, Verde y Amarilla; Union Station , la estación más concurrida por abordajes de pasajeros; [90] Farragut North ; y Farragut West .

Para hacer frente a la gran cantidad de pasajeros en las estaciones de transferencia, Metro está estudiando la posibilidad de construir conexiones peatonales entre las estaciones de transferencia centrales cercanas. Por ejemplo, un paso de 750 pies (230 m) entre las estaciones Metro Center y Gallery Place permitiría a los pasajeros hacer transbordo entre las líneas Naranja/Azul/Plata y Amarilla/Verde sin tener que ir a una parada en la Línea Roja o tomar un pequeño desvío a través de L'Enfant Plaza. Otro túnel entre las estaciones Farragut West y Farragut North permitiría transbordos entre las líneas Roja y Naranja/Azul/Plata, disminuyendo la demanda de transbordo en Metro Center en un estimado de 11%. [91] El túnel peatonal Farragut aún no se ha implementado físicamente, pero se agregó en forma virtual a partir del 28 de octubre de 2011: el sistema SmarTrip ahora interpreta una salida de una estación Farragut y una entrada a la otra como parte de un solo viaje, lo que permite a los titulares de tarjetas hacer transbordo a pie sin tener que pagar una segunda tarifa completa. [92]

La flota de Metro consta de 1.216 vagones, cada uno de 75 pies (22,86 m) de largo, con 1.208 en servicio de ingresos activos a mayo de 2024. Aunque las reglas de operación actualmente limitan los trenes a 59 mph (95 km/h) (excepto en la línea Verde, donde pueden ir hasta 65 mph (105 km/h)), [94] todos los trenes tienen una velocidad máxima de 75 mph (121 km/h), y un promedio de 33 mph (53 km/h), incluidas las paradas. [78] Todos los vagones funcionan como pares casados (numerados consecutivamente par-impar con una cabina en cada extremo del par excepto los vagones de la serie 7000), con sistemas compartidos en todo el par. [95]

En la tabla "Vagones activos", la fuente en negrita representa los vagones que están actualmente en servicio, mientras que la fuente normal representa los vagones que están temporalmente fuera de servicio.

El material rodante del Metro se adquirió en siete fases y cada versión de coche está identificada con un número de serie distinto.

El pedido original de 300 vagones (todos ellos retirados el 1 de julio de 2017) [100] fue fabricado por Rohr Industries , con entrega final en 1978. [104] Estos vagones están numerados del 1000 al 1299 y fueron rehabilitados a mediados de la década de 1990.

Breda Costruzioni Ferroviarie (Breda) fabricó el segundo pedido de 76 vagones entregados en 1983 y 1984. [104] Estos vagones, numerados del 2000 al 2075, fueron rehabilitados a principios de la década de 2000 por Alstom en Hornell, Nueva York . [105] Todos los vagones de la serie 2000 fueron retirados el 10 de mayo de 2024. [106]

Un tercer pedido de 290 coches, también procedentes de Breda, se entregó entre 1984 y 1988. [104] Estos coches están numerados del 3000 al 3289 y fueron rehabilitados por Alstom a mediados de la década de 2000. [105]

Un cuarto pedido de 100 automóviles de Breda, numerados del 4000 al 4099, se entregó entre 1991 y 1994. [104] Todos los automóviles de la serie 4000 se retiraron el 1 de julio de 2017. [98]

Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles (CAF) de España fabricó un quinto pedido de 192 vagones, numerados del 5000 al 5191, que se entregaron entre 2001 y 2004. [104] La mayoría de los vagones de la serie 5000 se retiraron en octubre de 2018 y los últimos en la primavera de 2019. [101]

Un sexto pedido de 184 vagones de Alstom Transportation, están numerados del 6000 al 6183 y fueron entregados entre 2005 y 2007. [104] Los vagones tienen carrocerías construidas en Barcelona , España, y el ensamblaje se completa en Hornell, Nueva York. [107]

Los vagones de la serie 7000, construidos por Kawasaki Heavy Industries Rolling Stock Company de Kobe, Japón, fueron entregados para pruebas in situ durante el invierno de 2013-2014 y entraron en servicio por primera vez el 14 de abril de 2015 en la Línea Azul. Los vagones se diferencian de los modelos anteriores en que, si bien siguen funcionando como pares casados, se elimina la cabina de un vagón, lo que lo convierte en un vagón B. Este diseño permite una mayor capacidad de pasajeros, la eliminación de equipos redundantes, una mayor eficiencia energética y menores costos de mantenimiento. La investigación de la Junta Nacional de Seguridad del Transporte del accidente fatal del 22 de junio de 2009 la llevó a concluir que los vagones de la serie 1000 no son seguros y no pueden proteger a los pasajeros en caso de choque. Como resultado, el 26 de julio de 2010, Metro votó a favor de comprar 300 vagones de la serie 7000, que reemplazaron a los vagones restantes de la serie 1000. [108] [109] También se ordenaron 128 vagones adicionales de la serie 7000 para prestar servicio en la Silver Line hasta el aeropuerto de Dulles (64 para cada fase). En abril de 2013, Metro realizó otro pedido de 100 vagones de la serie 7000, que reemplazaron a todos los vagones de la serie 4000. [110] El 13 de julio de 2015, WMATA utilizó su última opción y compró 220 vagones adicionales de la serie 7000 para la expansión de la flota y para reemplazar los vagones de la serie 5000, lo que elevó el número total de pedidos a 748 vagones. El 26 de febrero de 2020, WMATA aceptó la entrega del último vagón de la serie 7000. [111]

Los vagones de la serie 8000 serán construidos por Hitachi Rail. [112] [113] Si bien estos vagones tendrían una apariencia similar a la serie 7000, la serie 8000 incluiría más características como "puertas inteligentes" que detectan obstrucciones, cámaras de seguridad de alta definición, más espacio entre asientos, pasillos más anchos y pisos antideslizantes. [113] En septiembre de 2018, Metro emitió una solicitud de propuestas a los fabricantes para 256 vagones con opciones para un total de hasta 800. [114] El primer pedido reemplazaría el equipo de las series 2000 y 3000, mientras que las opciones, si se seleccionan, permitirían a la agencia aumentar la capacidad y retirar la serie 6000. [114]

Durante el funcionamiento normal de los trenes de pasajeros en las vías de pago, estos están diseñados para ser controlados por un sistema integrado de Operación Automática de Trenes (ATO) y Control Automático de Trenes (ATC) que acelera y frena los trenes automáticamente sin la intervención del operador. Todos los trenes siguen contando con operadores que abren y cierran las puertas, hacen anuncios en las estaciones y supervisan los trenes. El sistema fue diseñado para que un operador pudiera operar manualmente un tren cuando fuera necesario. [115]

Desde junio de 2009, cuando dos trenes de la Línea Roja chocaron y mataron a nueve personas debido en parte a fallas en el sistema ATC, todos los trenes de Metro han sido operados manualmente. [116] El estado actual de la operación manual ha llevado a un servicio muy degradado, con nuevos requisitos manuales como bloqueos absolutos, restricciones de velocidad y paradas al final de la plataforma que conducen a un aumento de los intervalos entre trenes, un mayor tiempo de espera y un peor rendimiento a tiempo. [117] Metro originalmente planeó que todos los trenes fueran automatizados nuevamente para 2017, [118] pero esos planes se archivaron a principios de 2017 para centrarse en problemas de seguridad e infraestructura más urgentes. [119] En marzo de 2023, Metro anunció planes para volver a automatizar el sistema para diciembre de ese año, [120] pero anunció en septiembre que estos planes se retrasarían hasta 2024. [121]

Las puertas de los trenes fueron diseñadas originalmente para abrirse y cerrarse automáticamente y se volverían a abrir si un objeto las bloqueaba, de forma muy similar a las puertas de los ascensores. Casi inmediatamente después de que se inaugurara el sistema en 1976, Metro se dio cuenta de que estas características no conducían a un funcionamiento seguro o eficiente y las desactivó. Metro comenzó a probar la reinstalación de la apertura automática de las puertas de los trenes en marzo de 2019, citando demoras y posibles errores humanos. [122] Si una puerta intenta cerrarse y encuentra una obstrucción, el operador debe volver a abrirla. En octubre de 2023, la apertura automática de las puertas de los trenes, en la que las puertas del tren se abren automáticamente al descender, se restableció en un número limitado de trenes de la Línea Roja. Los operadores deben cerrar manualmente las puertas después de que se abran. WMATA afirma que la apertura automática de puertas proporciona un beneficio de seguridad, ya que elimina el posible error humano que provoca que las puertas se abran del lado equivocado y una reducción del tiempo de espera antes de que se abran las puertas, lo que mejora la experiencia del cliente y los tiempos de permanencia en la estación. [123]

El Metrorail comienza a prestar servicio a las 5 a. m. de lunes a viernes, a las 7 a. m. los sábados y domingos; finaliza a la medianoche de lunes a jueves, a la 1:00 a. m. los viernes y sábados, y a la medianoche los domingos, aunque los últimos trenes salen de las estaciones finales en dirección a la ciudad aproximadamente media hora antes de estos horarios. [124] [125] Antes de la pandemia, los trenes circulaban con mayor frecuencia durante las horas pico en todas las líneas, con intervalos de paso programados en las horas pico de 4 minutos en la Línea Roja y de 8 minutos en todas las demás líneas. Los intervalos eran mucho más largos durante el mediodía y la noche de los días laborables y los fines de semana durante todo el día. Los intervalos de paso de seis minutos al mediodía se basaban en una combinación de dos líneas de Metrorail (Naranja/Azul y Amarilla/Verde), ya que cada ruta podía pasar cada 12 minutos; en el caso de la Línea Roja, todos los demás trenes con destino a Glenmont terminaban en Silver Spring. El servicio nocturno y de fin de semana variaba entre 8 y 20 minutos, y los trenes generalmente se programaban solo cada 15 a 20 minutos. [126]

Otros truncamientos del servicio también ocurren en el sistema solo durante el servicio de hora pico. En la Línea Roja, todos los trenes con destino a Shady Grove terminaban en Grosvenor–Strathmore hasta diciembre de 2018, [127] además de las terminaciones alternas en Silver Spring mencionadas anteriormente. Para la Línea Amarilla , todos los trenes que no sean Rush+ con destino a Greenbelt y todos los trenes normales con destino a Fort Totten terminan en Mount Vernon Square . Estos se instituyeron principalmente debido a un suministro limitado de vagones de ferrocarril y las ubicaciones de las vías de bolsillo en todo el sistema. Sin embargo, a partir de julio de 2019, ambos truncamientos del servicio de la Línea Roja han terminado, y a partir de abril de 2019, la Línea Amarilla sirvió a Greenbelt en todo momento. Cuando la Línea Amarilla reabrió el 7 de mayo de 2023, luego de un importante trabajo de mantenimiento, se restableció el retorno a Mount Vernon Square en todo momento, lo que no ha sucedido desde 2006.

Hasta 1999, Metro finalizaba el servicio a medianoche todas las noches y el servicio de fin de semana comenzaba a las 8 a. m. Ese año, WMATA comenzó a ofrecer un servicio nocturno los viernes y sábados hasta la 1 a. m. En 2007, con el apoyo de las empresas, se había retrasado ese horario de cierre hasta las 3 a. m. [128] y se aplicaban tarifas pico para las entradas después de la medianoche. En 2011, se plantearon planes para poner fin al servicio nocturno debido a los costos, pero los pasajeros se resistieron. [129] WMATA suspendió temporalmente el servicio ferroviario nocturno el 30 de mayo de 2016, para que Metro pudiera llevar a cabo un amplio programa de rehabilitación de vías en un esfuerzo por mejorar la confiabilidad del sistema. [130] [131]

El 25 de junio de 2017, Metro redujo su horario de funcionamiento y cerró a las 23:30 horas de lunes a jueves, a la 1 de la mañana los viernes y sábados, y a las 23 horas los domingos, [132] [133] y los últimos trenes salieron de las estaciones finales en dirección a la estación de llegada aproximadamente media hora antes de estos horarios. [134] A partir de 2022, se han restablecido los horarios de servicio anteriores a 2017. [64]

Metro opera patrones de servicio especiales en días festivos y cuando los eventos en Washington pueden requerir un servicio adicional. Las actividades del Día de la Independencia requieren que Metro ajuste el servicio para brindar capacidad adicional hacia y desde el National Mall . [135] WMATA realiza ajustes similares durante otros eventos, como las inauguraciones presidenciales . Debido a preocupaciones de seguridad relacionadas con el ataque al Capitolio de los Estados Unidos del 6 de enero , varias estaciones de Metro se cerraron para la inauguración de 2021. Metro ha modificado el servicio y ha utilizado algunas estaciones como entradas o salidas solo para ayudar a controlar la congestión. [136]

En 2012, WMATA anunció un servicio mejorado en horas pico que se implementó el 18 de junio de 2012, bajo el nombre de "Rush+" (o "Rush Plus"). El servicio Rush Plus se brindaba solo durante las horas pico: de 6:30 a 9:00 a. m. y de 3:30 a 6:00 p. m., de lunes a viernes.

El realineamiento de Rush+ tenía como objetivo liberar espacio en el Portal Rosslyn (el túnel entre Rosslyn y Foggy Bottom), que ya funciona a plena capacidad. Cuando comenzó el servicio de la Silver Line, esos trenes pasarían por el túnel, por lo que algunos de los trenes de la Blue Line que iban al centro de Largo se desviaron por el puente Fenwick para convertirse en trenes de la Yellow Line que recorren toda la Green Line hasta Greenbelt . Algunos trenes de la Yellow Line que iban hacia el sur se desviaron por la Blue Line hasta Franconia–Springfield (en lugar de la terminal normal de la Yellow Line en Huntington ). Hasta el inicio del servicio de la Silver Line, la capacidad sobrante del Rosslyn Tunn era utilizada por trenes adicionales de la Orange Line que viajaban por la Blue Line hasta Largo (en lugar de la terminal normal de la Orange Line en New Carrollton ). Rush+ tuvo el efecto adicional de ofrecer a un mayor número de pasajeros viajes sin transbordo, aunque aumentó considerablemente los intervalos de tiempo para la parte de la Blue Line que va entre Pentagon y Rosslyn . En mayo de 2017, Metro anunció que el servicio Yellow Rush+ se eliminaría a partir del 25 de junio de 2017. [137]

Los intervalos se han alargado como resultado de la pandemia de COVID-19 en Washington, DC , a partir de principios de 2020. El servicio casi anterior a la pandemia se restableció en ocasiones hasta octubre de 2021, pero debido al descarrilamiento de la serie 7000 cerca del cementerio de Arlington y la posterior retirada de todos los vagones de la serie 7000 del servicio (que constituían el 60% de la flota de WMATA), los intervalos se alargaron de nuevo a cada 15 minutos en la Línea Roja y cada 30 minutos en todas las demás líneas a partir del 19 de octubre de 2021. [138]

Desde entonces, con el regreso de más vagones de la serie 7000, los intervalos de paso se han ido recuperando gradualmente hasta alcanzar niveles casi previos a la pandemia, y el número de pasajeros también ha aumentado. A partir de julio de 2023, varias líneas son más frecuentes que antes durante las horas de menor actividad de los días laborables, los fines de semana y las noches. La Línea Roja ahora funciona cada 6 minutos durante todo el día de los días laborables en toda su longitud, y cada 8 minutos durante todo el día los fines de semana (antes funcionaba cada 12 minutos los días laborables fuera de las horas punta y los sábados, y cada 15 minutos los domingos). Las líneas Verde y Amarilla ahora funcionan cada 8 minutos durante todo el día, en lugar de hacerlo solo durante las horas punta (antes de la pandemia, ambas líneas funcionaban cada 12-15 minutos fuera de las horas punta y los fines de semana, y cada 15-20 minutos por las noches), aunque esta última ahora regresa en Mount Vernon Square en lugar de continuar hasta Greenbelt. La Línea Naranja ahora funciona cada 10 minutos todos los días antes de las 9:30 p. m. (aún no alcanza el intervalo máximo de 8 minutos antes de la pandemia, pero es una mejora con respecto a cada 12 a 15 minutos fuera de horas punta y los fines de semana, y cada 15 a 20 minutos por las noches). Todas las líneas funcionan constantemente cada 12 minutos o menos los domingos antes de las 9:30 p. m., una gran mejora con respecto a los intervalos de 15 minutos todo el día los domingos en todas las líneas excepto la Línea Roja, y cada 15 minutos o más después de las 9:30 p. m. todos los días, una gran mejora con respecto a los intervalos de 20 minutos en las horas de la tarde en todas las líneas excepto la Línea Roja. La Línea Roja solía funcionar cada 15 a 18 minutos durante las tardes, pero ahora funciona cada 10.

Avances al 23 de febrero de 2024. [139]

Intervalos de servicio a partir del 26 de junio de 2023. [139] [140] Vienna y Dunn Loring estuvieron cerradas hasta el 17 de julio. Con su reapertura, el servicio será igual al servicio actual de West Falls Church a East Falls Church.

En el año 2000 se instaló un sistema de visualización de información para pasajeros (PIDS) en todas las estaciones de Metrorail. Las pantallas están ubicadas en todas las plataformas de las vías y en las entradas del entrepiso de las estaciones. Proporcionan información en tiempo real sobre la llegada de los próximos trenes, incluida la línea, el destino, la cantidad de vagones en el tren y el tiempo de espera estimado. Las pantallas también muestran información sobre trenes retrasados, anuncios de emergencia y otros boletines. [141] Las señales se actualizaron en 2013 para reflejar mejor los horarios de Rush Plus y Silver Line, y para priorizar la información sobre la llegada del próximo tren sobre otros anuncios. [142] Se instalaron nuevas señales PIDS digitales en las seis estaciones al sur del Aeropuerto Nacional en el verano de 2019 como parte del Proyecto de Mejora de la Plataforma. [143]

WMATA también proporciona información actual sobre trenes e información relacionada a los clientes con navegadores web convencionales , así como a los usuarios de teléfonos inteligentes y otros dispositivos móviles. [144] En 2010, Metro comenzó a compartir sus datos PIDS con desarrolladores de software externos, para su uso en la creación de aplicaciones adicionales en tiempo real para dispositivos móviles. Hay aplicaciones gratuitas disponibles para el público en las principales plataformas de software de dispositivos móviles ( iOS , Android , Windows Phone , Palm ). [145] [146] WMATA también comenzó a proporcionar información de trenes en tiempo real por teléfono en 2010. [147]

Los pasajeros entran y salen del sistema utilizando una tarjeta de valor almacenado en forma de tarjeta de proximidad conocida como SmarTrip . La tarifa se deduce del saldo de la tarjeta al salir. [148] Las tarjetas SmarTrip se pueden comprar en las máquinas expendedoras de las estaciones, en línea o en puntos de venta minorista, y pueden almacenar hasta $300 en valor. Metro también acepta CharmCard de Baltimore, un sistema de tarjeta de pago sin contacto similar.

Las tarifas del metro varían según la distancia recorrida y la hora del día en que se ingresa. Las tarifas (vigentes a partir de 2024) varían de $2.25 a $6.75, dependiendo de la distancia recorrida durante los días de semana antes de las 9:30 p. m. y de $2.25 a $2.50 los fines de semana o después de las 9:30 p. m. de los días de semana en el momento de ingresar. Hay tarifas con descuento del 50% al 100% disponibles para niños en edad escolar de DC, [149] beneficiarios de SNAP en Maryland, Virginia y Washington DC, [150] personas con discapacidades , [151] [152] y personas mayores . [152] Las tarifas de estacionamiento en las estaciones de metro varían de $3.00 a $5.20 los días de semana para pasajeros; las tarifas para no pasajeros varían de $3.00 a $10.00. El estacionamiento es gratuito los sábados, domingos y feriados federales. [153]

Desde el 25 de junio de 2017, cuando se produjo el primer aumento de tarifas en tres años, las tarifas de tren en temporada alta aumentaron 10 centavos, con un mínimo de $2,25 y un máximo de $6,00 para un viaje de ida. Las tarifas fuera de temporada alta aumentaron 25 centavos, con un mínimo de $2,00 y un máximo de $3,85, al igual que las tarifas de autobús. [154] [155] [156] [133] Se puso a disposición un nuevo pase de tren/autobús ilimitado de un día por $14,75, [133] que actualmente está disponible por $13,50. [157]

El 24 de junio de 2024, WMATA anunció otro aumento de tarifas que entraría en vigencia el 30 de junio de 2024, con un aumento general del 12,5 % para la mayoría de los servicios. De los aumentos de tarifas, la tarifa ferroviaria durante los días hábiles aumentó a un rango de $2,25 a $6,75, mientras que la tarifa fija de $2,00 durante las horas nocturnas (después de las 9:30) y los fines de semana se reemplazó a un rango de $2,25 a $2,50 dependiendo de la distancia recorrida. [158]

Los pasajeros pueden comprar pases en las máquinas expendedoras de tarjetas de viaje. Los pases se cargan en las mismas tarjetas SmarTrip que el valor almacenado, pero otorgan a los pasajeros viajes ilimitados dentro del sistema durante un período de tiempo determinado. El período de validez comienza con el primer uso. Actualmente se venden cuatro tipos de pases: [157] [159]

In addition, Metro sells the Monthly Unlimited Pass, formerly called SelectPass, available for purchase online only by registered SmarTrip cardholders, valid for trips up to a specified value for a specific calendar month, with the balance being deducted from the card's cash value similarly to the Short Trip Pass.[160] The pass is priced based on 18 days of round-trip travel.[161]

Users can add value to any farecard. Riders pay an exit fare based on time of day and distance traveled. Trips may include segments on multiple lines under one fare as long as the rider does not exit the faregates, with the exception of the "Farragut Crossing" out-of-station interchange between the Farragut West and Farragut North stations. At Farragut Crossing, riders may exit from one station and reenter at the other within 30 minutes on a single fare. When making a trip that uses Metrobus and Metrorail, a $2.25 discount is available when using a SmarTrip card when transferring from Metrobus to Metrorail, and Transfers from Metrorail to Metrobus are free; Transfers must be done within 2 hours.[162][92]When entering and exiting at the same station, users are normally charged a minimum fare ($2.25). However, since July 1, 2016, users have had a 15-minute grace period to exit the station; those who do so will receive a rebate of the amount paid as an autoload to their SmarTrip card.[163][164]

Students at District of Columbia schools (public, charter, private, and parochial) ride both Metrobus and Metrorail for free.[165]

The contract for Metro's fare collection system was awarded in 1975 to Cubic Transportation Systems.[166] Electronic fare collection using paper magnetic stripe cards started on July 1, 1977, a little more than a year after the first stations opened. Prior to electronic fare collection, exact change fareboxes were used.[167] Metro's historic paper farecard system is also shared by Bay Area Rapid Transit, which Cubic won a contract for in 1974.[166] Any remaining value stored on the paper cards was printed on the card at each exit, and passes were printed with the expiration date.

Several adjustments were made to shift the availability of passes from paper tickets to SmarTrip cards in 2012 and 2013. In May 2014 Metro announced plans to retrofit more than 500 fare vending machines throughout the system to dispense SmarTrip cards, rather than paper fare cards, and eventually eliminate magnetic fare cards entirely.[168] This was completed in early December 2015 when the last paper farecard was sold.[169] The faregates stopped accepting paper farecards on March 6, 2016,[170][171] and the last day for trading in farecards to transfer the value to SmarTrip was June 30, 2016.[171]

Metro planners designed the system with passenger safety and order maintenance as primary considerations. The open vaulted ceiling design of stations and the limited obstructions on platforms allow few opportunities to conceal criminal activity. Station platforms are built away from station walls to limit vandalism and provide for diffused lighting of the station from recessed lights. Metro's attempts to reduce crime, combined with how the station environments were designed with crime prevention in mind,[172] have contributed to Metro being among the safest and cleanest subway systems in the United States.[173] There are nearly 6,000 video surveillance cameras used across the system to enhance security.[174]

Metro is patrolled by its own police force, which is charged with ensuring the safety of passengers and employees. Transit Police officers patrol the Metro and Metrobus systems, and they have jurisdiction and arrest powers throughout the 1,500-square-mile (3,900 km2) Metro service area for crimes that occur on or against transit authority facilities, or within 150 feet (46 m) of a Metrobus stop. The Metro Transit Police Department is one of two U.S. police agencies that has local police authority in three "state"-level jurisdictions (Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia), the U.S. Park Police being the other.[175]

Each city and county in the Metro service area has similar ordinances that regulate or prohibit vending on Metro-owned property, and which prohibit riders from eating, drinking, or smoking in Metro trains, buses, and stations; the Transit Police have a reputation for enforcing these laws rigorously. One widely publicized incident occurred in October 2000 when police arrested 12-year-old Ansche Hedgepeth for eating french fries in the Tenleytown–AU station.[176] In a 2004 opinion by John Roberts, now Chief Justice of the United States, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Hedgepeth's arrest.[177] By then WMATA had answered negative publicity by adopting a policy of first issuing warnings to juveniles, and arresting them only after three violations within a year.

Metro's zero tolerance policy on food, trash and other sources of disorder embodies the "broken windows" philosophy of crime reduction. This philosophy also extends to the use of station restroom facilities. A longstanding policy, intended to curb unlawful and unwanted activity, has been to only allow employees to use Metro restrooms.[173] One widely publicized example of this was when a pregnant woman was denied access to the bathroom by a station manager at the Shady Grove station.[178] Metro now allows the use of restrooms by passengers who gain a station manager's permission, except during periods of heightened terror alerts.[179][180]

On January 22, 2019, the D.C. Council voted 11–2 to override Mayor Muriel Bowser's veto of the Fare Evasion Decriminalization Act, setting the penalty for fare evasion at a $50 civil fine, a reduction from the previous criminal penalty of a fine up to $300 and 10 days in jail.[181]

On October 27, 2008, the Metro Transit Police Department announced plans to immediately begin random searches of backpacks, purses, and other bags. Transit police would search riders at random before boarding a bus or entering a station. It also explained its intent to stop anyone acting suspiciously.[182] Metro claims that "Legal authority to inspect packages brought into the Metro system has been established by the court system on similar types of inspections in mass transit properties, airports, military facilities and courthouses."[183] Metro Transit Police Chief Michael Taborn stated that, if someone were to turn around and simply enter the system through another escalator or elevator, Metro has "a plan to address suspicious behavior".[184] Security expert Bruce Schneier characterized the plan as "security theater against a movie plot threat" and does not believe random bag searches actually improve security.[185]

The Metro Riders' Advisory Council recommended to WMATA's board of directors that Metro hold at least one public meeting regarding the search program. As of December 2008[update], Metro had not conducted a single bag search.[186]

In 2010 Metro once again announced that it would implement random bag searches, and conducted the first such searches on December 21, 2010.[187] The searches consist of swabbing bags and packages for explosive residue, and X-raying or opening any packages which turned up positive. On the first day of searches, at least one false positive for explosives was produced, which Metro officials indicated could occur for a variety of reasons including if a passenger had recently been in contact with firearms or been to a firing range.[188] The D.C. Bill of Rights Coalition and the Montgomery County Civil Rights Coalition circulated a petition against random bag searches, taking the position that the practice violates the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution and would not improve security.[189] On January 3, 2011, Metro held a public forum for the searches at a Metro Riders' Advisory Council meeting, at which more than 50 riders spoke out, most of them in opposition to the searches. However at the meeting Metro officials called random bag inspections a "success" and claimed that few riders had complained.[190]

After a prolonged absence, as of February 2017[update], bag searches have resumed at random stations throughout the Washington Metro area.[citation needed]

Several collisions have occurred on Washington Metro, resulting in injuries and fatalities, along with numerous derailments with few or no injuries. WMATA has been criticized for disregarding safety warnings and advice from experts. The Tri-State Oversight Committee oversaw WMATA, but had no regulatory authority. Metro's safety department is usually in charge of investigating incidents, but could not require other Metro departments to implement its recommendations.[191] Following several safety lapses, the Federal Transit Administration assumed oversight at WMATA.[192]

During the Blizzard of 1996, on January 6, a Metro operator was killed when a train failed to stop at the Shady Grove station. The four-car train overran the station platform and struck an unoccupied train that was awaiting assignment. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation found that the crash was a result of a failure in the train's computer-controlled braking system. The NTSB recommended that Metro grant train operators the ability to manually control the braking system, even in inclement weather, and recommended that Metro prohibit parked rail cars on tracks used by incoming outbound trains.[193]

On November 3, 2004, an out-of-service Red Line train rolled backwards into the Woodley Park station, hitting an in-service train stopped at the platform. The rear car (1077) was telescoped by the first car of the standing train (4018). No one died, 20 people were injured.[194] A 14-month investigation concluded that the train operator was most likely not alert as the train rolled backwards into the station. Safety officials estimated that had the train been full, at least 79 people would have died. The train operator was dismissed and Metro officials agreed to add rollback protection to more than 300 rail cars.[195]

On June 22, 2009, at 5:02 pm, two trains on the Red Line collided. A southbound train heading toward Shady Grove stopped on the track short of the Fort Totten station and another southbound train collided with its rear. The front car of the moving train (1079) was telescoped by the rear car of the standing train (5066),[196] and passengers were trapped. Nine people died and more than 70 were injured, dozens of whom were described as "walking wounded".[197] Red Line service was suspended between the Fort Totten and Takoma stations, and New Hampshire Avenue was closed.[198][199] One of the dead was the operator of the train that collided with the stopped train.

On November 29, 2009, at 4:27 am, two trains collided at the West Falls Church train yard. One train pulled in and collided with the back of the other train. No customers were aboard, and only minor injuries to the operators and cleaning staff were reported. However, three cars (1106, 1171, and 3216) were believed to be damaged beyond repair.[200]

On January 13, 1982, a train derailed at a malfunctioning crossover switch south of the Federal Triangle station. In attempting to restore the train to the rails, supervisors failed to notice that another car had also derailed. The other rail car slid off the track and hit a tunnel support, killing three people and injuring 25 in its first fatal crash. Coincidentally, this crash occurred about 30 minutes after Air Florida Flight 90 crashed into the nearby 14th Street Bridge during a major snowstorm.[6]

On January 20, 2003, during construction of a new canopy at the National Airport station, Metro began running trains through the center track even though it had not been constructed for standard operations, and a Blue Line train derailed at the switch. No injuries resulted but the crash delayed construction by a number of weeks.[201]

On January 7, 2007, a Green Line train carrying approximately 120 people derailed near the Mount Vernon Square station in downtown Washington. Trains were single-tracking at the time, and the derailment of the fifth car occurred where the train was switching from the south to northbound track. The crash injured at least 18 people and prompted the rescue of 60 people from a tunnel.[202] At least one person had a serious but non-life-threatening injury. The incident was one of a series of five derailments involving 5000-series cars, with four of those occurring on side tracks and not involving passengers.[203]

On June 9, 2008, an Orange Line train (2000-series) derailed between the Rosslyn and Court House stations.[204][205]

On March 27, 2009, a Red Line train derailed just before 4:30 pm just south of Bethesda station causing delays but no injuries. A second train was sent to move the first train but it too derailed when it was about 600 feet (180 m) from the first train.[206]

On February 12, 2010, a Red Line train derailed at about 10:13 am as it left the Farragut North station in downtown Washington. After leaving the station, the train entered the pocket track north of the station. As it continued, an automatic derailer at the end of the pocket track intentionally derailed the train as a safety measure. If the train had continued moving forward on the pocket track, it would have entered the path of an oncoming train. The wheels of the first two cars in the six-car, White-Flint-bound train were forced off the tracks, stopping the train. Almost all of the estimated 345 passengers were evacuated from the damaged train by 11:50 am and the NTSB arrived on the scene by noon. Two minor injuries were reported, and a third passenger was taken to George Washington University Hospital.[207] The NTSB ruled the crash was due to the train operator's failure to follow standard procedures and WMATA management for failure to provide proper supervision of the train operator which resulted in the incomplete configuration of the train identification and destination codes leading to the routing of the train into the pocket track.[208]

On April 24, 2012, around 7:15 pm, a Blue Line train bound for Franconia–Springfield derailed near Rosslyn. No injuries were reported.[209]

On July 6, 2012, around 4:45 pm, a Green Line train bound for downtown Washington, D.C., and Branch Avenue derailed near West Hyattsville. No injuries were reported. A heat kink, due to the hot weather, was identified as the probable cause of the accident.[210]

On August 6, 2015, a non-passenger train derailed outside the Smithsonian station. The track condition that caused the derailment had been detected a month earlier but was not repaired.[211]

On July 29, 2016, a Silver Line train heading in the direction of Wiehle–Reston East station derailed outside East Falls Church station. Service was suspended between Ballston and West Falls Church and McLean stations on the Orange and Silver Lines.[212]

On September 1, 2016, Metro announced the derailment of an empty six-car train in the Alexandria Rail Yard. No injuries or service interruptions were reported and an investigation is ongoing.[213]

On January 15, 2018, a Red Line train derailed between the Farragut North and Metro Center stations. No injuries were reported. This was the first derailment of the new 7000-series trains.[214]

On July 7, 2020, a 7000-series Red line train derailed one wheelset on departure from Silver Spring around 11:20 in the morning.

On October 12, 2021, a 7000-series Blue Line train derailed outside the Arlington Cemetery station. This forced the evacuation of all 187 passengers on board with no reported injuries.[215] Cause of the derailment was initially stated to be an axle not up to specifications and resulted in sidelining the entire 7000-series fleet of trains, approximately 60% of WMATA's current trains through Friday, October 29, 2021, for further inspection.[216] On October 28, 2021, WMATA announced that the system would continue running at a reduced capacity through November 15, 2021, as further investigation took place.[215] The inspection determined a defect causes the car's wheels to be pushed outward. As of July 2022, the system was still running without most 7000-series cars. Workers manually inspect wheels on eight trains daily to catch the defect before it becomes problematic; the remaining cars are out of service pending an automated fix.[217]

On July 13, 2009, WMATA adopted a "zero tolerance" policy for train or bus operators found to be texting or using other hand-held devices while on the job. This new and stricter policy came after investigations of several mass-transit accidents in the U.S. found that operators were texting at the time of the accident. The policy change was announced the day after a passenger of a Metro train videotaped the operator texting while operating the train.[218]

During the early evening rush on January 12, 2015, a Yellow Line train stopped in the tunnel. It filled with smoke just after departing L'Enfant Plaza for Pentagon due to "an electrical arcing event" ahead in the tunnel. Everyone on board was evacuated; 84 people were taken to hospitals, and one died.[219]

On March 14, 2016, an electrified rail caught fire between McPherson Square and Farragut West, causing significant disruptions on the Blue, Orange, and Silver lines. Two days later, the entire Metro system was shut down so its electric rail power grid could be inspected.[220]

As of 2008, WMATA expects an average of one million riders daily by 2030. The need to increase capacity has renewed plans to add 220 cars to the system and reroute trains to alleviate congestion at the busiest stations.[221] Population growth in the region has also revived efforts to extend service, build new stations, and construct additional lines.

The original plan called for ten future extensions on top of the core system. The Red Line would have been extended from the Rockville station northwest to Germantown, Maryland. The Green Line would have been lengthened northward from Greenbelt to Laurel, Maryland, and southward from Branch Avenue to Brandywine, Maryland. The Blue Line initially consisted of a southwestern branch to Backlick Road and Burke, Virginia, which was never built. The Orange Line would have extended westward through Northern Virginia past the Vienna station to Centreville or Haymarket, and northeastward past New Carrollton to Bowie, Maryland. Alternatively, the Blue Line would have been extended east past Downtown Largo to Bowie. The future Silver Line was also included in this proposal.[17]

In 2001, officials considered realigning the Blue Line between Rosslyn and Stadium–Armory stations by building a bridge or tunnel from Virginia to a new station in Georgetown. Blue Line trains share a single tunnel with Orange Line and Silver Line trains to cross the Potomac River. The current tunnel limits service in each direction, creating a choke point.[222] The proposal was later rejected due to cost,[223] but Metro again started considering a similar scenario in 2011.[224]

In 2005 the Department of Defense announced that it would be shifting 18,000 jobs to Fort Belvoir in Virginia and at least 5,000 jobs to Fort Meade in Maryland by 2012, as part of that year's Base Realignment and Closure plan. In anticipation of such a move, local officials and the military proposed extending the Blue and Green Lines to service each base. The proposed extension of the Green Line could cost $100 million per mile ($60 million per kilometer), and a light rail extension to Fort Belvoir was estimated to cost up to $800 million. Neither proposal has established timelines for planning or construction.[225][226]

The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) announced on January 18, 2008, that it and the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT) had begun work on a draft environmental impact statement (EIS) for the I-66 corridor in Fairfax and Prince William counties. According to VDOT the EIS, officially named the I-66 Multimodal Transportation and Environment Study, would focus on improving mobility along I-66 from the Capital Beltway (I-495) interchange in Fairfax County to the interchange with U.S. Route 15 in Prince William County. The EIS also allegedly includes a four-station extension of the Orange Line past Vienna. The extension would continue to run in the I-66 median and would have stations at Chain Bridge Road, Fair Oaks, Stringfellow Road and Centreville near Virginia Route 28 and U.S. Route 29.[227] In its final report published June 8, 2012, the study and analysis revealed that an "extension would have a minimal impact on Metrorail ridership and volumes on study area roadways inside the Beltway and would therefore not relieve congestion in the study corridor."[228]

In 2011 Metro began studying the needs of the system through 2040. WMATA subsequently published a study on the alternatives, none of which were funded for planning or construction.[224][229] New Metro rail lines and extensions under consideration as part of this long-term plan included:

In September 2021, a report on the capacity improvements of Blue/Orange/Silver lines proposed four alternative extensions for the system:

All four alternatives use the same central segment layout from Rosslyn to Union Station through Georgetown.[231] NBC4 Washington further reported on the proposed loop in December 2022. At the time, there was a crowding problem at the Rosslyn station, and this expansion could be the solution to solve this crowding problem. A final design was published in July 2023.[233]

Before construction on Metro began, a proposed station was put forward for the Kennedy Center. Congress had already approved the construction of a station on the Orange/Blue/Silver Lines at 23rd and H Streets, near George Washington University, at the site of what is now Foggy Bottom station. According to a Washington Post article from February 1966, rerouting the line to accommodate a station under the center would cost an estimated $12.3 million.[234] The National Capital Transportation Agency's administrator at the time, Walter J. McCarter, suggested that the Center "may wish to enhance the relationship to the station by constructing a pleasant, above-ground walkway from the station to the Center," referring to the then soon-to-be-built Foggy Bottom station. Rep. William B. Widnall, Republican of New Jersey, used it as an opportunity to push for moving the center to a central, downtown location.[235]

The 2011 Metro transit-needs study identified five additional sites where infill stations could be built. These included Kansas Avenue and Montgomery College on the Red Line, respectively in Northwest D.C. and Rockville, Maryland; Oklahoma Avenue on the Blue, Orange, and Silver Lines near the D.C. Armory in Northeast D.C.; Eisenhower Valley on the Blue Line in Alexandria, Virginia; and the St. Elizabeths Hospital campus on the Green Line in Southeast D.C.[229]: 11

A number of light rail and urban streetcar projects are under construction or have been proposed to extend or supplement service provided by Metro. The Purple Line, a light rail system, operated by the Maryland Transit Administration, is under construction as of 2023 and is scheduled to open in late 2027.[236] The project was originally envisioned as a circular heavy rail line connecting the outer stations on each branch of the Metrorail system, in a pattern roughly mirroring the Capital Beltway.[237] The current project will run between the Bethesda and New Carrollton stations by way of Silver Spring and College Park. The Purple Line will connect both branches of the Red Line to the Green and Orange Lines, and would decrease the travel time between suburban Metro stations.[236][238]

The Corridor Cities Transitway (CCT) is a proposed 15-mile (24 km) bus rapid transit line that would link Clarksburg, Maryland, in northern Montgomery County with the Shady Grove station on the Red Line.[239] Assuming that the anticipated federal, state, and local government funds are provided, construction of the first 9 miles (14 km) of the system would begin in 2018.[240]

In 2005, a Maryland lawmaker proposed a light rail system to connect areas of Southern Maryland, especially the rapidly growing area around the town of Waldorf, to the Branch Avenue station on the Green Line.[241]

The District of Columbia Department of Transportation is building the new DC Streetcar system to improve transit connectivity within the District. A tram line to connect Bolling Air Force Base to the Anacostia station and was originally expected to open in 2010. Streetcar routes have been proposed in the Atlas District, Capitol Hill, and the K Street corridor.[242] After seven years of construction, the Atlas District route, known as the H/Benning Street route, opened on February 27, 2016.[243]

In 2013, the Georgetown Business Improvement District proposed a gondola lift between Georgetown and Rosslyn as an alternative to placing a Metro stop at Georgetown in its 2013–2028 economic plans.[244] Washington, D.C., and Arlington County have been conducting feasibility studies for it since 2016.[244]

The Washington Metro has often appeared in movies and television shows set in Washington. However, due to fees and expenses required to film in the Metro, scenes of the Metro in film are often not of the Metro itself, but of other stand-in subway stations that are made to represent the Metro.[245]

The vaulted ceilings of the Metro have become a cultural signifier of Washington, D.C., and are often seen in photographs and other art depicting the city.[246]

What do I need to know to build near Metro property? Metro reviews designs and monitors construction of projects adjacent to Metrorail and Metrobus property...

Percentage calculated from figures in pages 12 and 41 . $635.4 mil./$1022.9 mil = 62%.

Replace all 366 of the 2000 and the 3000 Series rail cars with new 8000 Series rail cars.

1975 Cubic wins $54 million contract to provide system for Washington D.C.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)extension would have a minimal impact on Metrorail ridership and volumes on study area roadways inside the Beltway and would therefore not relieve congestion in the study corridor.