Al-Qaeda ( / æ l ˈ k aɪ ( ə ) d ə / (en árabe:القاعدة,romanizado: al-Qāʿidah,lit. 'la Base',IPA: [alˈqaː.ʕi.da]) es unaorganización militantepanislamistayihadistassunitas que se identifican a sí mismos como una vanguardia que encabeza unarevolución islamistapara unir almundo musulmáncalifato islámicosupranacional.[103][104]Su membresía está compuesta principalmente porárabes, pero también incluye personas de otros grupos étnicos.[105]Al Qaeda ha organizado ataques contra objetivos civiles, económicos y militares de los EE. UU. y sus aliados; como los atentadoscon bombas a la embajada de EE. UU. de 1998, elatentado con bombasal USSColey losataques del 11 de septiembre. La organización está designada comogrupo terroristaporla OTAN, elConsejo de Seguridad de la ONU, laUnión Europeay varios países de todo el mundo.

La organización fue fundada en una serie de reuniones celebradas en Peshawar durante 1988, a las que asistieron Abdullah Azzam , Osama bin Laden , Muhammad Atef , Ayman al-Zawahiri y otros veteranos de la guerra soviética-afgana . [106] Basándose en las redes de Maktab al-Khidamat , los miembros fundadores decidieron crear una organización llamada " Al-Qaeda " para servir como una "vanguardia" para la yihad . [106] [107] Cuando Saddam Hussein invadió y ocupó Kuwait en 1990, bin Laden ofreció apoyar a Arabia Saudita enviando a sus combatientes muyahidines . Su oferta fue rechazada por el gobierno saudí, que en su lugar buscó la ayuda de los Estados Unidos . El estacionamiento de tropas estadounidenses en la península Arábiga impulsó a bin Laden a declarar una yihad contra los gobernantes de Arabia Saudita, a quienes denunció como murtadd (apóstatas), y contra los Estados Unidos. Desde 1992, Al Qaeda estableció su sede en Sudán hasta que fue expulsada en 1996. Luego trasladó su base a Afganistán, gobernado por los talibanes , y más tarde se expandió a otras partes del mundo, principalmente en Oriente Medio y el sur de Asia . En 1996 y 1998, Bin Laden emitió dos fatwas que exigían la retirada de las tropas estadounidenses de Arabia Saudita.

En 1998, Al Qaeda llevó a cabo los atentados con bombas en las embajadas de Estados Unidos en Kenia y Tanzania , en los que murieron 224 personas. Estados Unidos respondió lanzando la Operación Alcance Infinito contra objetivos de Al Qaeda en Afganistán y Sudán. En 2001, Al Qaeda llevó a cabo los atentados del 11 de septiembre , que provocaron casi 3.000 muertes , consecuencias sanitarias a largo plazo para los residentes cercanos , daños a los mercados económicos mundiales , el desencadenamiento de cambios geopolíticos drásticos y la generación de una profunda influencia cultural en todo el mundo . Estados Unidos lanzó la guerra contra el terrorismo en respuesta e invadió Afganistán para derrocar a los talibanes y destruir a Al Qaeda. En 2003, una coalición liderada por Estados Unidos invadió Irak , derrocando al régimen baasista al que acusaron falsamente de tener vínculos con Al Qaeda. En 2004, Al Qaeda lanzó su rama regional iraquí . Después de perseguirlo durante casi una década , el ejército estadounidense mató a Bin Laden en Pakistán en mayo de 2011.

Los miembros de Al Qaeda creen que una alianza judeocristiana (liderada por Estados Unidos ) está librando una guerra contra el Islam y conspirando para destruirlo . [ 108] [109] Al Qaeda también se opone a las leyes creadas por el hombre y busca implementar la sharīʿah (ley islámica) en los países musulmanes. [110] Los combatientes de Al Qaeda suelen desplegar tácticas como ataques suicidas ( operaciones Inghimasi e Istishhadi ) que implican el bombardeo simultáneo de varios objetivos en zonas de batalla. [111] La rama iraquí de Al Qaeda , que luego se transformó en el Estado Islámico de Irak después de 2006, fue responsable de numerosos ataques sectarios contra los chiítas durante su insurgencia iraquí . [112] [113] Los ideólogos de Al Qaeda prevén la eliminación violenta de todas las influencias extranjeras y secularistas en los países musulmanes , que denuncia como desviaciones corruptas. [47] [114] [115] [116] Tras la muerte de Bin Laden en 2011, Al Qaeda juró vengar su asesinato. El grupo estuvo entonces dirigido por el egipcio Ayman al Zawahiri hasta que él también fue asesinado por Estados Unidos en 2022. A partir de 2021 [update], se informa que han sufrido un deterioro del mando central sobre sus operaciones regionales. [117]

Al Qaeda controla sólo indirectamente sus operaciones diarias. Su filosofía exige la centralización de la toma de decisiones, permitiendo al mismo tiempo la descentralización de la ejecución. [118] Los principales líderes de Al Qaeda han definido la ideología y la estrategia rectora de la organización, y también han articulado mensajes simples y fáciles de recibir. Al mismo tiempo, se dio autonomía a las organizaciones de nivel medio, pero tuvieron que consultar con la alta dirección antes de ataques y asesinatos a gran escala. La alta dirección incluía el consejo de la shura, así como comités de operaciones militares, finanzas e intercambio de información. A través de los comités de información de Al Qaeda, Zawahiri puso especial énfasis en la comunicación con sus grupos. [119] Sin embargo, después de la guerra contra el terrorismo , el liderazgo de Al Qaeda se ha aislado. Como resultado, el liderazgo se ha descentralizado y la organización se ha regionalizado en varios grupos de Al Qaeda. [120] [121]

El grupo estaba inicialmente dominado por egipcios y saudíes , con cierta participación de yemeníes y kuwaitíes . Con el tiempo, se ha convertido en una organización terrorista más internacional. Si bien su grupo principal originalmente compartía un origen en Egipto y la península Arábiga, desde entonces ha atraído a combatientes de otros grupos árabes, incluidos norteafricanos , jordanos , palestinos e iraquíes . En la década posterior a los ataques del 11 de septiembre, musulmanes de orígenes no árabes, como paquistaníes , afganos , turcos , kurdos y europeos conversos al Islam , también se han unido a la organización. [122]

Muchos analistas occidentales no creen que el movimiento yihadista global esté impulsado en todos los niveles por el liderazgo de Al Qaeda. Sin embargo, Bin Laden ejerció una considerable influencia ideológica sobre los movimientos islamistas revolucionarios en todo el mundo. Los expertos sostienen que Al Qaeda se ha fragmentado en una serie de movimientos regionales dispares y que estos grupos tienen poca conexión entre sí. [123]

Esta visión refleja el relato dado por Osama bin Laden en su entrevista de octubre de 2001 con Tayseer Allouni :

Este asunto no tiene que ver con ninguna persona en particular y ... no tiene que ver con la Organización Al Qaeda. Somos los hijos de una nación islámica, con el Profeta Muhammad como su líder, nuestro Señor es uno ... y todos los verdaderos creyentes [mu'mineen] son hermanos. Así que la situación no es como la presenta Occidente, que existe una "organización" con un nombre específico (como "Al Qaeda") y demás. Ese nombre en particular es muy antiguo. Nació sin ninguna intención por nuestra parte. El hermano Abu Ubaida ... creó una base militar para entrenar a los jóvenes para luchar contra el imperio soviético cruel, arrogante, brutal y terrorista ... Así que este lugar se llamó "La Base" ["Al Qaeda"], como una base de entrenamiento, así que este nombre creció y se convirtió. No estamos separados de esta nación. Somos hijos de una nación, y somos parte inseparable de ella, y desde esas manifestaciones públicas que se extendieron desde el lejano Oriente, desde Filipinas a Indonesia, a Malasia, a la India, a Pakistán, llegando a Mauritania ... y así discutimos la conciencia de esta nación. [124]

[update]Sin embargo, en 2010 Bruce Hoffman vio a Al Qaeda como una red cohesiva que estaba fuertemente dirigida desde las áreas tribales paquistaníes. [123]

.jpg/440px-Al-Qaida_crée_une_brigade_dirigée_par_des_Touaregs_(8246938011).jpg)

Al Qaeda tiene los siguientes afiliados directos:

Se cree que actualmente los siguientes son afiliados indirectos de Al Qaeda:

Entre los antiguos afiliados de Al Qaeda se incluyen los siguientes:

Osama bin Laden sirvió como emir de al-Qaeda desde la fundación de la organización en 1988 hasta su asesinato por las fuerzas estadounidenses el 1 de mayo de 2011. [134] Se alega que Atiyah Abd al-Rahman era el segundo al mando antes de su muerte el 22 de agosto de 2011. [135]

Bin Laden fue asesorado por un Consejo Shura , que consiste en miembros de alto rango de Al Qaeda. [119] Se estimó que el grupo estaba formado por entre 20 y 30 personas.

Ayman al-Zawahiri había sido el emir adjunto de Al Qaeda y asumió el papel de emir tras la muerte de Bin Laden. Al-Zawahiri reemplazó a Saif al-Adel , que había servido como comandante interino. [136]

El 5 de junio de 2012, funcionarios de inteligencia paquistaníes anunciaron que el supuesto sucesor de al-Rahman como segundo al mando, Abu Yahya al-Libi , había sido asesinado en Pakistán. [137]

Se alega que Nasir al-Wuhayshi se convirtió en el segundo al mando y gerente general de Al Qaeda en 2013. Fue al mismo tiempo el líder de Al Qaeda en la Península Arábiga (AQAP) hasta que fue asesinado por un ataque aéreo estadounidense en Yemen en junio de 2015. [138] Abu Khayr al-Masri , el supuesto sucesor de Wuhayshi como adjunto de Ayman al-Zawahiri, fue asesinado por un ataque aéreo estadounidense en Siria en febrero de 2017. [139] El siguiente supuesto líder número dos de Al Qaeda, Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah , fue asesinado por agentes israelíes. Su seudónimo era Abu Muhammad al-Masri, quien fue asesinado en noviembre de 2020 en Irán. Estuvo involucrado en los atentados de 1998 a las embajadas estadounidenses en Kenia y Tanzania. [140]

La red de Al Qaeda se construyó desde cero como una red conspirativa que se nutrió del liderazgo de una serie de nodos regionales. [141] La organización se dividió en varios comités, que incluyen:

Al-Zawahiri fue asesinado el 31 de julio de 2022 en un ataque con drones en Afganistán. [146] En febrero de 2023, un informe de las Naciones Unidas, basado en la inteligencia de los estados miembros, concluyó que el liderazgo de facto de Al Qaeda había pasado a Saif al-Adel , que operaba desde Irán. Adel, un ex oficial del ejército egipcio, se convirtió en instructor militar en los campamentos de Al Qaeda en la década de 1990 y era conocido por su participación en la batalla de Mogadiscio. El informe afirmó que Al Qaeda no podía declarar oficialmente el liderazgo de Al-Adel debido a las "sensibilidades políticas" del gobierno afgano al reconocer la muerte de Al-Zawahiri, así como debido a los desafíos "teológicos y operativos" que plantea la ubicación de Al-Adel en Irán . [147] [148]

La mayoría de los principales líderes y directores operativos de Al Qaeda eran veteranos que lucharon contra la invasión soviética de Afganistán en la década de 1980. Osama bin Laden y su adjunto, Ayman al-Zawahiri, eran los líderes que se consideraban los comandantes operativos de la organización. [149] Sin embargo, Al Qaeda no estaba dirigida operativamente por Ayman al-Zawahiri. Existen varios grupos operativos que consultan con el liderazgo en situaciones en las que se están preparando ataques. [119] "... Zawahiri no afirma tener un control jerárquico directo sobre la vasta estructura en red de Al Qaeda. El liderazgo central de Al Qaeda busca centralizar el mensaje y la estrategia de la organización en lugar de gestionar las operaciones diarias de sus franquicias. Pero se requiere que los afiliados formales consulten con el liderazgo central de Al Qaeda antes de llevar a cabo ataques a gran escala".</ref> Al-Qaeda central (AQC) es un conglomerado de comités de expertos, cada uno de los cuales supervisa tareas y objetivos distintos. Sus miembros están compuestos principalmente por líderes islamistas egipcios que participaron en la yihad afgana anticomunista . Los asisten cientos de operativos y comandantes islámicos de campo, con base en varias regiones del mundo musulmán . El liderazgo central asume el control del enfoque doctrinal y la campaña de propaganda general, mientras que los comandantes regionales fueron empoderados con independencia en la estrategia militar y las maniobras políticas. Esta novedosa jerarquía hizo posible que la organización lanzara ofensivas de amplio alcance. [150]

Cuando en 2005 se le preguntó sobre la posibilidad de que Al Qaeda tuviera una conexión con los atentados del 7 de julio de 2005 en Londres , el Comisionado de la Policía Metropolitana Sir Ian Blair dijo: "Al Qaeda no es una organización. Al Qaeda es una forma de trabajar ... pero esto tiene el sello de ese enfoque ... Al Qaeda claramente tiene la capacidad de proporcionar entrenamiento ... de proporcionar experiencia ... y creo que eso es lo que ha ocurrido aquí". [151] El 13 de agosto de 2005, el periódico The Independent informó que los terroristas del 7 de julio habían actuado independientemente de un cerebro de Al Qaeda. [152]

Nasser al-Bahri, que fue guardaespaldas de Osama bin Laden durante cuatro años en el período previo al 11 de septiembre, escribió en sus memorias una descripción muy detallada de cómo funcionaba el grupo en ese momento. Al-Bahri describió la estructura administrativa formal de Al Qaeda y su vasto arsenal. [153] Sin embargo, el autor Adam Curtis sostuvo que la idea de Al Qaeda como una organización formal es principalmente una invención estadounidense. Curtis sostuvo que el nombre "Al Qaeda" se hizo público por primera vez en el juicio de 2001 a Bin Laden y los cuatro hombres acusados de los atentados con bombas a la embajada estadounidense en África Oriental en 1998. Curtis escribió:

La realidad era que Bin Laden y Ayman al-Zawahiri se habían convertido en el foco de una asociación informal de militantes islamistas desilusionados que se sintieron atraídos por la nueva estrategia. Pero no había ninguna organización. Se trataba de militantes que en su mayoría planificaban sus propias operaciones y buscaban financiación y asistencia en Bin Laden. Él no era su comandante. Tampoco hay pruebas de que Bin Laden utilizara el término "al-Qaeda" para referirse al nombre de un grupo hasta después de los ataques del 11 de septiembre, cuando se dio cuenta de que ése era el término que le habían dado los estadounidenses. [154]

Durante el juicio de 2001, el Departamento de Justicia de los Estados Unidos necesitaba demostrar que Bin Laden era el líder de una organización criminal para poder acusarlo en ausencia bajo la Ley de Organizaciones Corruptas e Influenciadas por el Crimen Organizado. El nombre de la organización y los detalles de su estructura fueron proporcionados en el testimonio de Jamal al-Fadl , quien dijo que era un miembro fundador del grupo y un ex empleado de Bin Laden. [155] Varias fuentes han planteado preguntas sobre la fiabilidad del testimonio de al-Fadl debido a su historial de deshonestidad y porque lo estaba dando como parte de un acuerdo de culpabilidad después de ser condenado por conspirar para atacar establecimientos militares estadounidenses. [156] [157] Sam Schmidt, un abogado defensor que defendió a al-Fadl dijo:

Creo que hubo partes del testimonio de Al Fadl que eran falsas, para ayudar a sustentar la imagen de que él ayudó a los estadounidenses a unirse. Creo que mintió en una serie de testimonios específicos sobre una imagen unificada de lo que era esta organización. Hizo que Al Qaeda fuera la nueva mafia o los nuevos comunistas. Los hizo identificables como grupo y, por lo tanto, facilitó el procesamiento de cualquier persona asociada con Al Qaeda por cualquier acto o declaración hecha por Bin Laden. [154]

Se desconoce en gran medida el número de miembros del grupo que han recibido un entrenamiento militar adecuado y son capaces de comandar fuerzas insurgentes. Los documentos capturados en el allanamiento al complejo de Bin Laden en 2011 muestran que el núcleo de miembros de Al Qaeda en 2002 era de 170. [158] En 2006, se estimó que Al Qaeda tenía varios miles de comandantes integrados en 40 países. [159] En 2009 [update], se creía que no más de 200 a 300 miembros seguían siendo comandantes activos. [160]

Según el documental de la BBC de 2004 The Power of Nightmares , Al Qaeda estaba tan débilmente vinculada que era difícil decir que existía aparte de Bin Laden y una pequeña camarilla de colaboradores cercanos. La falta de un número significativo de miembros de Al Qaeda condenados, a pesar de un gran número de arrestos por cargos de terrorismo, fue citada por el documental como una razón para dudar de si existía una entidad generalizada que cumpliera con la descripción de Al Qaeda. [161] Los comandantes de Al Qaeda, así como sus agentes durmientes, se esconden en diferentes partes del mundo hasta el día de hoy. Son perseguidos principalmente por los servicios secretos estadounidenses e israelíes.

Según el autor Robert Cassidy, Al Qaeda mantiene dos fuerzas separadas que están desplegadas junto a los insurgentes en Irak y Pakistán. La primera, compuesta por decenas de miles de personas, fue "organizada, entrenada y equipada como fuerza de combate insurgente" en la guerra soviética-afgana. [159] La fuerza estaba compuesta principalmente por muyahidines extranjeros de Arabia Saudita y Yemen. Muchos de estos combatientes continuaron luchando en Bosnia y Somalia en el marco de la yihad global . Otro grupo, que contaba con 10.000 miembros en 2006, vive en Occidente y ha recibido entrenamiento de combate rudimentario. [159]

Otros analistas han descrito a las bases de Al Qaeda como "predominantemente árabes" en sus primeros años de funcionamiento, pero que la organización también incluye a "otros pueblos" a partir de 2007. [update][ 162] Se ha estimado que el 62 por ciento de los miembros de Al Qaeda tienen educación universitaria. [163] En 2011 y el año siguiente, los estadounidenses ajustaron cuentas con éxito con Osama bin Laden, Anwar al-Awlaki, el principal propagandista de la organización, y el comandante adjunto de Abu Yahya al-Libi. Las voces optimistas ya decían que se había acabado para Al Qaeda. Sin embargo, fue en esa época cuando la Primavera Árabe saludó a la región, cuya agitación afectó gravemente a las fuerzas regionales de Al Qaeda. Siete años después, Ayman al-Zawahiri se convirtió en posiblemente el líder número uno de la organización, implementando su estrategia con una coherencia sistemática. Decenas de miles de leales a Al Qaeda y organizaciones afines pudieron desafiar la estabilidad local y regional y atacar sin piedad a sus enemigos en Oriente Medio, África, el sur de Asia, el sudeste asiático, Europa y Rusia por igual. De hecho, desde el noroeste de África hasta el sur de Asia, Al Qaeda tenía más de dos docenas de aliados "basados en franquicias". El número de militantes de Al Qaeda se estimó en 20.000 sólo en Siria, y tenía 4.000 miembros en Yemen y unos 7.000 en Somalia. La guerra no había terminado. [54]

En 2001, Al Qaeda tenía alrededor de 20 células en funcionamiento y 70.000 insurgentes repartidos en sesenta países. [164] Según las últimas estimaciones, el número de soldados en servicio activo bajo su mando y milicias aliadas ha aumentado a aproximadamente 250.000 en 2018. [165]

Al Qaeda no suele desembolsar fondos para sus atentados y muy rara vez realiza transferencias bancarias. [166] En los años 1990, la financiación procedía en parte de la riqueza personal de Osama bin Laden. [167] Otras fuentes de ingresos incluían el tráfico de heroína y las donaciones de partidarios en Kuwait, Arabia Saudita y otros estados islámicos del Golfo . [167] Un cable diplomático filtrado en 2009 afirmaba que "la financiación del terrorismo procedente de Arabia Saudita sigue siendo una grave preocupación". [168]

Entre las primeras pruebas sobre el apoyo de Arabia Saudita a Al Qaeda se encontraba la llamada « Cadena de Oro », una lista de los primeros financiadores de Al Qaeda incautada durante una redada en Sarajevo en 2002 por la policía bosnia. [169] La lista escrita a mano fue validada por el desertor de Al Qaeda Jamal al-Fadl, e incluía los nombres tanto de los donantes como de los beneficiarios. [169] [66] El nombre de Osama bin Laden apareció siete veces entre los beneficiarios, mientras que 20 empresarios y políticos saudíes y del Golfo figuraban entre los donantes. [169] Entre los donantes notables se encontraban Adel Batterjee y Wael Hamza Julaidan . Batterjee fue designado como financista del terrorismo por el Departamento del Tesoro de los Estados Unidos en 2004, y Julaidan es reconocido como uno de los fundadores de Al Qaeda. [169]

Los documentos confiscados durante la redada de Bosnia en 2002 mostraron que Al Qaeda explotó ampliamente las organizaciones benéficas para canalizar apoyo financiero y material a sus agentes en todo el mundo. [170] Cabe destacar que esta actividad explotó a la Organización Internacional de Ayuda Islámica (IIRO) y la Liga Musulmana Mundial (MWL). La IIRO tenía vínculos con socios de Al Qaeda en todo el mundo, incluido el lugarteniente de Al Qaeda, Ayman al Zawahiri. El hermano de Zawahiri trabajaba para la IIRO en Albania y había reclutado activamente en nombre de Al Qaeda. [171] La MWL fue identificada abiertamente por el líder de Al Qaeda como una de las tres organizaciones benéficas de las que Al Qaeda dependía principalmente para obtener fuentes de financiación. [171]

Varios ciudadanos qataríes han sido acusados de financiar a Al Qaeda, entre ellos Abd Al-Rahman al-Nuaimi , ciudadano qatarí y activista de derechos humanos que fundó la organización no gubernamental (ONG) Alkarama , con sede en Suiza . El 18 de diciembre de 2013, el Departamento del Tesoro de Estados Unidos designó a Nuaimi como terrorista por sus actividades de apoyo a Al Qaeda. [172] El Departamento del Tesoro de Estados Unidos ha dicho que Nuaimi "ha facilitado un importante apoyo financiero a Al Qaeda en Irak y ha servido como interlocutor entre Al Qaeda en Irak y donantes con sede en Qatar". [172]

Nuaimi fue acusado de supervisar una transferencia mensual de 2 millones de dólares a Al Qaeda en Irak como parte de su papel como mediador entre los altos oficiales de Al Qaeda con base en Irak y los ciudadanos qataríes. [172] [173] Nuaimi supuestamente mantuvo relaciones con Abu-Khalid al-Suri, el principal enviado de Al Qaeda en Siria, quien procesó una transferencia de 600.000 dólares a Al Qaeda en 2013. [172] [173] También se sabe que Nuaimi está asociado con Abd al-Wahhab Muhammad 'Abd al-Rahman al-Humayqani, un político yemení y miembro fundador de Alkarama , que fue catalogado como Terrorista Global Especialmente Designado (SDGT) por el Tesoro de los Estados Unidos en 2013. [174] Las autoridades estadounidenses afirmaron que Humayqani explotó su papel en Alkarama para recaudar fondos en nombre de Al Qaeda en la Península Arábiga (AQAP). [172] [174] Nuaimi, figura destacada de AQAP, también fue acusado de facilitar el flujo de fondos a las filiales de AQAP con sede en Yemen. Nuaimi también fue acusado de invertir fondos en la organización benéfica dirigida por Humayqani para financiar en última instancia a AQAP. [172] Unos diez meses después de ser sancionado por el Tesoro de los Estados Unidos, a Nuaimi también se le prohibió hacer negocios en el Reino Unido. [175]

Otro ciudadano qatarí, Kalifa Mohammed Turki Subayi, fue sancionado por el Tesoro de los Estados Unidos el 5 de junio de 2008 por sus actividades como "financiero de Al Qaeda con base en el Golfo". El nombre de Subayi fue añadido a la Lista de Sanciones del Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU en 2008 bajo la acusación de proporcionar apoyo financiero y material a los altos mandos de Al Qaeda. [173] [176] Subayi presuntamente trasladó a reclutas de Al Qaeda a campos de entrenamiento con base en el sur de Asia. [173] [176] También apoyó económicamente a Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, un ciudadano paquistaní y alto oficial de Al Qaeda que se cree que es el cerebro detrás del ataque del 11 de septiembre según el Informe de la Comisión del 11-S . [177]

Los qataríes brindaron apoyo a Al Qaeda a través de la ONG más grande del país, Qatar Charity . El desertor de Al Qaeda Al Fadl, que fue miembro de Qatar Charity, testificó ante el tribunal que Abdullah Mohammed Yusef, quien se desempeñó como director de Qatar Charity, estaba afiliado a Al Qaeda y simultáneamente al Frente Islámico Nacional , un grupo político que dio refugio al líder de Al Qaeda, Osama Bin Laden, en Sudán a principios de la década de 1990. [66]

Se afirmó que en 1993 Osama bin Laden estaba utilizando organizaciones benéficas sunitas con sede en Oriente Medio para canalizar apoyo financiero a los agentes de Al Qaeda en el extranjero. Los mismos documentos también informan de la denuncia de Bin Laden de que el intento fallido de asesinato del presidente egipcio Hosni Mubarak había comprometido la capacidad de Al Qaeda de explotar las organizaciones benéficas para apoyar a sus agentes en la medida en que lo había hecho antes de 1995. [178]

Qatar financió las empresas de Al Qaeda a través de su antigua filial en Siria, Jabhat al Nusra. La financiación se canalizó principalmente a través de secuestros para pedir rescate. [179] El Consorcio Contra la Financiación del Terrorismo (CATF) informó que el país del Golfo ha financiado a Al Nusra desde 2013. [179] En 2017, Asharq Al-Awsat estimó que Qatar había desembolsado 25 millones de dólares en apoyo de Al Nusra a través de secuestros para pedir rescate. [180] Además, Qatar ha lanzado campañas de recaudación de fondos en nombre de Al Nusra. Al Nusra reconoció una campaña patrocinada por Qatar "como uno de los canales preferidos para las donaciones destinadas al grupo". [181] [182]

En el desacuerdo sobre si los objetivos de Al Qaeda son religiosos o políticos, Mark Sedgwick describe la estrategia de Al Qaeda como política en el corto plazo pero con objetivos finales que son religiosos. [183] El 11 de marzo de 2005, Al-Quds Al-Arabi publicó extractos del documento de Saif al-Adel "La estrategia de Al Qaeda hasta el año 2020". [8] [184] Abdel Bari Atwan resume esta estrategia como compuesta por cinco etapas para liberar a la Ummah de todas las formas de opresión:

Atwan señaló que, si bien el plan no es realista, "da que pensar que esto prácticamente describe la caída de la Unión Soviética ". [8]

Según Fouad Hussein , periodista y autor jordano que pasó un tiempo en prisión con Al-Zarqawi, la estrategia de Al Qaeda consta de siete fases y es similar al plan descrito en la Estrategia de Al Qaeda hasta el año 2020. Estas fases incluyen: [185]

Según la estrategia de siete fases, se prevé que la guerra dure menos de dos años.

Según Charles Lister, del Middle East Institute, y Katherine Zimmerman, del American Enterprise Institute , el nuevo modelo de Al Qaeda es "socializar las comunidades" y construir una amplia base territorial de operaciones con el apoyo de las comunidades locales, obteniendo además ingresos independientes de la financiación de los jeques. [186]

El nombre en inglés de la organización es una transliteración simplificada del sustantivo árabe al-qāʿidah ( القاعدة ), que significa "la fundación" o "la base". La inicial al- es el artículo definido árabe "el", de ahí "la base". [187] En árabe, al-Qaeda tiene cuatro sílabas ( /alˈqaː.ʕi.da/ ). Sin embargo, dado que dos de las consonantes árabes en el nombre no son fonemas que se encuentran en el idioma inglés, las pronunciaciones inglesas naturalizadas comunes incluyen / æ l ˈ k aɪ d ə / , / æ l ˈ k eɪ d ə / y / ˌ æ l k ɑː ˈ iː d ə / . El nombre de Al Qaeda también puede transliterarse como al-Qaida , al-Qa'ida o el-Qaida . [188]

El concepto doctrinal de " al-Qaeda " fue acuñado por primera vez por el erudito islamista palestino y líder yihadista Abdullah Azzam en un número de abril de 1988 de la revista Al-Jihad para describir una vanguardia de musulmanes comprometidos con la religión que libran la yihad armada en todo el mundo para liberar a los musulmanes oprimidos de los invasores extranjeros, establecer la sharia (ley islámica) en todo el mundo islámico derrocando a los gobiernos seculares gobernantes ; y así restaurar la destreza islámica del pasado. Esto se implementaría estableciendo un estado islámico que alimentaría generaciones de soldados musulmanes que atacarían perpetuamente a Estados Unidos y sus gobiernos aliados en el mundo musulmán. Azzam citó numerosos modelos históricos como ejemplos exitosos de su llamado, desde las primeras conquistas musulmanas del siglo VII hasta la reciente yihad afgana antisoviética de la década de 1980. [189] [190] [191] Según la visión del mundo de Azzam:

Ya es hora de pensar en un Estado que sea una base sólida para la distribución del credo (islámico) y una fortaleza para albergar a los predicadores del infierno de la Jahiliyyah [el período preislámico]. [191]

Bin Laden explicó el origen del término en una entrevista grabada en vídeo con el periodista de Al Jazeera Tayseer Alouni en octubre de 2001:

El nombre de Al Qaeda se creó hace mucho tiempo por pura casualidad. El difunto Abu Ebeida El-Banashiri estableció los campos de entrenamiento para nuestros muyahidines contra el terrorismo ruso. Solíamos llamar a ese campo de entrenamiento Al Qaeda. El nombre se mantuvo. [192]

Se ha afirmado que dos documentos confiscados en la oficina de Sarajevo de la Fundación Internacional de Beneficencia prueban que el nombre no fue simplemente adoptado por el movimiento muyahidín y que en agosto de 1988 se creó un grupo llamado Al Qaeda. Ambos documentos contienen actas de reuniones celebradas para establecer un nuevo grupo militar y contienen el término "Al Qaeda". [193]

El ex secretario de Asuntos Exteriores británico Robin Cook escribió que la palabra al-Qaeda debería traducirse como "la base de datos", porque originalmente se refería al archivo informático de los miles de militantes muyahidines que fueron reclutados y entrenados con la ayuda de la CIA para derrotar a los rusos. [194] En abril de 2002, el grupo asumió el nombre de Qa'idat al-Jihad ( قاعدة الجهاد qāʿidat al-jihād ), que significa "la base de la Yihad". Según Diaa Rashwan , esto fue "aparentemente como resultado de la fusión de la rama en el extranjero de al-Jihad de Egipto , que estaba dirigida por Ayman al-Zawahiri , con los grupos que Bin Laden puso bajo su control después de su regreso a Afganistán a mediados de la década de 1990". [195]

El movimiento militante panislamista de Al Qaeda se desarrolló en medio del auge de los movimientos revivalistas islámicos y yihadistas después de la Revolución iraní (1978-1979) y durante la Yihad afgana (1979-1989). Los escritos del erudito islamista egipcio e ideólogo revolucionario Sayyid Qutb inspiraron fuertemente a los líderes fundadores de Al Qaeda. [196] En las décadas de 1950 y 1960, Qutb predicó que debido a la falta de la ley sharia , el mundo musulmán ya no era musulmán y había vuelto a la ignorancia preislámica conocida como jahiliyyah . Para restaurar el Islam , Qutb argumentó que se necesitaba una vanguardia de musulmanes justos para establecer "verdaderos estados islámicos ", implementar la sharia y librar al mundo musulmán de cualquier influencia no musulmana. En opinión de Qutb, los enemigos del Islam incluían al " judaísmo mundial ", que "tramaba conspiraciones " y se oponía al Islam. [197] Qutb imaginó que esta vanguardia avanzaría para librar una yihad armada contra los regímenes tiránicos después de purificarse de las sociedades yahili más amplias y organizarse bajo un liderazgo islámico justo; que él veía como el modelo de los primeros musulmanes en el Estado Islámico de Medina bajo el liderazgo del profeta islámico Mahoma . Esta idea influiría directamente en muchas figuras islamistas como Abdullah Azzam y Osama bin Laden ; y se convirtió en la razón fundamental para la formulación del concepto de "al-Qaeda" en el futuro cercano. [198] Al esbozar su estrategia para derrocar los órdenes seculares existentes, Qutb argumentó en Milestones :

[Es necesario que] surja una comunidad musulmana que crea que " no hay deidad excepto Dios ", que se comprometa a no obedecer a nadie más que a Dios, negando toda otra autoridad y que cuestione la legalidad de cualquier ley que no esté basada en esta creencia... Debería entrar en el campo de batalla con la determinación de que su estrategia, su organización social y la relación entre sus individuos deben ser más firmes y más poderosas que el sistema jahili existente. [198] [199]

En palabras de Mohammed Jamal Khalifa , un amigo cercano de Bin Laden en la universidad:

El Islam es diferente de cualquier otra religión ; es una forma de vida. Nosotros [Khalifa y Bin Laden] intentábamos entender lo que el Islam tiene que decir sobre cómo comemos, con quién nos casamos, cómo hablamos. Leíamos a Sayyid Qutb. Fue él quien más influyó en nuestra generación. [200]

Qutb también influyó en Ayman al-Zawahiri . [201] El tío de Zawahiri y patriarca de la familia materna, Mafouz Azzam, fue alumno de Qutb, protegido, abogado personal y albacea de su patrimonio. Azzam fue una de las últimas personas que vio a Qutb con vida antes de su ejecución. [202] Zawahiri rindió homenaje a Qutb en su obra Caballeros bajo el estandarte del Profeta . [203]

Qutb sostuvo que muchos musulmanes no eran verdaderos musulmanes. Algunos musulmanes, sostuvo Qutb, eran apóstatas . Estos supuestos apóstatas incluían a líderes de países musulmanes, ya que no hicieron cumplir la ley sharia . [204] También sostuvo que Occidente se acerca al mundo musulmán con un "espíritu de cruzada"; a pesar del declive de los valores religiosos en la Europa del siglo XX. Según Qutb; las actitudes hostiles e imperialistas exhibidas por europeos y estadounidenses hacia los países musulmanes, su apoyo al sionismo, etc. reflejaban un odio amplificado a lo largo de milenios de guerras como las Cruzadas y nacieron de las perspectivas materialistas y utilitaristas romanas que veían el mundo en términos monetarios. [205]

La yihad afgana contra el gobierno prosoviético desarrolló aún más el movimiento yihadista salafista que inspiró a Al Qaeda. [206] Durante este período, Al Qaeda abrazó los ideales del militante revivalista musulmán indio Syed Ahmad Barelvi (fallecido en 1831), quien lideró un movimiento yihadista contra la India británica desde las fronteras de Afganistán y Khyber-Pakhtunkwa a principios del siglo XIX. Al Qaeda adoptó fácilmente las doctrinas de Sayyid Ahmad, como el regreso a la pureza de las primeras generaciones ( Salaf as-Salih ), la antipatía hacia las influencias occidentales y la restauración del poder político islámico. [207] [208] Según el periodista paquistaní Hussain Haqqani ,

El resurgimiento de la ideología de la yihad por parte de Sayyid Ahmed se convirtió en el prototipo de los movimientos militantes islámicos posteriores en el sur y centro de Asia y es también la principal influencia sobre la red yihadista de Al Qaeda y sus grupos asociados en la región. [207] [208]

El objetivo a largo plazo de Al Qaeda es unir al mundo musulmán bajo un estado islámico supranacional conocido como el Khilafah (Califato), encabezado por un califa electo descendiente de Ahl al-Bayt (la familia de Mahoma). Los objetivos inmediatos incluyen la expulsión de las tropas estadounidenses de la Península Arábiga, la realización de una yihad armada para derrocar a los gobiernos aliados de Estados Unidos en la región, etc. [209] [210]

Los siguientes son los objetivos y algunas de las políticas generales delineadas en la Carta Fundacional de Al Qaeda “ Estructura y Reglamentos de Al Qaeda ” emitida en las reuniones en Peshawar en 1988: [211] [209]

" Objetivos generales

i. Promover la concienciación sobre la yihad en el mundo islámico

. ii. Preparar y equipar a los cuadros para el mundo islámico mediante entrenamientos y participando en combates reales

. iii. Apoyar y patrocinar el movimiento de la yihad tanto como sea posible

. iv. Coordinar los movimientos de la yihad en todo el mundo en un esfuerzo por crear un movimiento de la yihad internacional unificado.Políticas generales

1. Compromiso completo con las reglas gobernantes y controles de la Shari'a en todas las creencias y acciones y de acuerdo con el libro [ Corán ] y la Sunna , así como por la interpretación de los eruditos de la nación que sirven en este dominio.

2. Compromiso con la Jihad como una lucha por la causa de Dios y como una agenda de cambio y prepararse para ella y aplicarla siempre que lo encontremos posible...

4. Nuestra posición con respecto a los tiranos del mundo, partidos seculares y nacionales y similares es no asociarnos con ellos, desacreditarlos y ser su enemigo constante hasta que crean solo en Dios. No estaremos de acuerdo con ellos en soluciones a medias y no hay manera de negociar con ellos o apaciguarlos

. 5. Nuestras relaciones con los movimientos y grupos yihadistas islámicos veraces es cooperar bajo el paraguas de la fe y la creencia y siempre intentaremos unirnos e integrarnos con ellos...

6. Mantendremos una relación de amor y afecto con los movimientos islámicos que no están alineados con la yihad...

7. Mantendremos una relación de respeto y amor con los eruditos activos...

9. Rechazaremos a los fanáticos regionales y perseguiremos la yihad en un país islámico según sea necesario y cuando sea posible.

10. Nos preocuparemos por el papel del pueblo musulmán en la yihad y trataremos de reclutarlos...

11. Mantendremos nuestra independencia económica y no dependeremos de otros para asegurar nuestros recursos.

12. El secreto es el ingrediente principal de nuestro trabajo, excepto lo que la necesidad considere necesario revelar.13. Nuestra política con la Yihad afgana es apoyar, asesorar y coordinar con los estamentos islámicos en los ámbitos de la Yihad de una manera que se ajuste a nuestras políticas.

— Estructura y estatutos de Al Qaeda, pág. 2, [211] [209]

Al Qaeda pretende establecer un estado islámico en el mundo árabe , siguiendo el modelo del califato de Rashidun , iniciando una yihad global contra la "Alianza Internacional Judía-Cruzada" liderada por los Estados Unidos, a la que ve como el "enemigo externo" y contra los gobiernos seculares en los países musulmanes , que se describen como "el enemigo interno apóstata". [212] Una vez que las influencias extranjeras y las autoridades gobernantes seculares sean eliminadas de los países musulmanes mediante la yihad , Al Qaeda apoya las elecciones para elegir a los gobernantes de sus propuestos estados islámicos . Esto se debe hacer a través de representantes de los consejos de liderazgo ( Shura ) que garantizarían la implementación de la Sharia (ley islámica). Sin embargo, se opone a las elecciones que instituyen parlamentos que facultan a los legisladores musulmanes y no musulmanes para colaborar en la elaboración de leyes de su propia elección. [213] En la segunda edición de su libro Knights Under the Banner of the Prophet , Ayman Al Zawahiri escribe:

Exigimos... el gobierno de un califato que guíe correctamente, que se establezca sobre la base de la soberanía de la sharia y no de los caprichos de la mayoría. Su ummah elige a sus gobernantes... Si se desvían, la ummah los hace rendir cuentas y los destituye. La ummah participa en la elaboración de las decisiones de ese gobierno y en la determinación de su dirección... [El estado califal] ordena lo correcto y prohíbe lo incorrecto y emprende la yihad para liberar las tierras musulmanas y liberar a toda la humanidad de toda opresión e ignorancia. [214]

Un tema recurrente en la ideología de Al Qaeda es el agravio perpetuo por la subyugación violenta de los disidentes islámicos por parte de los regímenes autoritarios y secularistas aliados de Occidente. Al Qaeda denuncia a estos gobiernos poscoloniales como un sistema dirigido por élites occidentalizadas diseñado para promover el neocolonialismo y mantener la hegemonía occidental sobre el mundo musulmán. El tema de agravio más destacado es la política exterior estadounidense en el mundo árabe ; especialmente su fuerte apoyo económico y militar a Israel . Otras preocupaciones de resentimiento incluyen la presencia de tropas de la OTAN para apoyar a los regímenes aliados; las injusticias cometidas contra los musulmanes en Cachemira , Chechenia , Xinjiang , Siria , Afganistán , Irak , etc. [215]

Abdel Bari Atwan escribió que:

Aunque la plataforma teológica de la dirigencia es esencialmente salafista, el paraguas de la organización es lo suficientemente amplio como para abarcar diversas escuelas de pensamiento y tendencias políticas. Al Qaeda cuenta entre sus miembros y partidarios con personas asociadas con el wahabismo , el shafismo , el malikismo y el hanafismo . Incluso hay algunos miembros de Al Qaeda cuyas creencias y prácticas están directamente en desacuerdo con el salafismo, como Yunis Khalis , uno de los líderes de los muyahidines afganos. Era un místico que visitaba las tumbas de los santos y buscaba sus bendiciones, prácticas hostiles a la escuela de pensamiento wahabí-salafista de Bin Laden. La única excepción a esta política panislámica es el chiismo . Al Qaeda parece oponerse implacablemente a él, ya que considera que el chiismo es una herejía. En Irak ha declarado abiertamente la guerra a las Brigadas Badr, que han cooperado plenamente con Estados Unidos, y ahora considera incluso a los civiles chiítas como objetivos legítimos de actos de violencia. [216]

Por otra parte, el profesor Peter Mandaville afirma que Al Qaeda sigue una política pragmática en la formación de sus filiales locales, con diversas células subcontratadas a miembros musulmanes chiítas y no musulmanes. La cadena de mando de arriba hacia abajo significa que cada unidad responde directamente a la dirección central, mientras que permanece ignorante de la presencia o las actividades de sus homólogos. Estas redes transnacionales de cadenas de suministro autónomas, financistas, milicias clandestinas y partidarios políticos se crearon durante la década de 1990, cuando el objetivo inmediato de Bin Laden era la expulsión de las tropas estadounidenses de la Península Arábiga . [217]

Bajo el liderazgo de Osama bin Laden y Ayman al-Zawahiri , la organización Al Qaeda adoptó la estrategia de atacar a civiles no combatientes de estados enemigos que atacaban indiscriminadamente a musulmanes. Después de los ataques del 11 de septiembre , Al Qaeda proporcionó una justificación para el asesinato de civiles no combatientes, titulada "Una declaración de Qaidat al-Jihad sobre los mandatos de los héroes y la legalidad de las operaciones en Nueva York y Washington". Según un par de críticos, Quintan Wiktorowicz y John Kaltner, proporciona "amplia justificación teológica para matar civiles en casi cualquier situación imaginable". [218]

Entre estas justificaciones se encuentra la de que Estados Unidos está liderando a Occidente en la guerra contra el Islam, de modo que los ataques contra Estados Unidos son una defensa del Islam y cualquier tratado o acuerdo entre los Estados de mayoría musulmana y los países occidentales que se viole con los ataques es nulo y sin valor. Según el tratado, varias condiciones permiten el asesinato de civiles, entre ellas:

Bajo el liderazgo de Sayf al-Adel , la estrategia de Al Qaeda ha experimentado una transformación y la organización ha renunciado oficialmente a la táctica de atacar objetivos civiles de los enemigos. En su libro Free Reading of 33 Strategies of War , publicado en 2023, Sayf al-Adel aconsejó a los combatientes islamistas que priorizaran los ataques a las fuerzas policiales, los soldados militares, los bienes estatales de los gobiernos enemigos, etc., que describió como objetivos aceptables en las operaciones militares. Afirmando que atacar a las mujeres y los niños de los enemigos es contrario a los valores islámicos, Sayf al-Adel preguntó: "Si atacamos al público en general, ¿cómo podemos esperar que su gente acepte nuestro llamado al Islam ?" [219]

Al Qaeda ha llevado a cabo un total de seis ataques importantes, cuatro de ellos en el marco de su yihad contra Estados Unidos. En cada caso, los líderes planearon el ataque con años de antelación, organizando el envío de armas y explosivos y utilizando sus empresas para proporcionar a sus agentes refugios e identidades falsas. [220]

Para evitar que el ex rey afgano Mohammed Zahir Shah regresara del exilio y posiblemente se convirtiera en jefe de un nuevo gobierno, Bin Laden instruyó a un portugués convertido al Islam , Paulo José de Almeida Santos, para que asesinara a Zahir Shah. El 4 de noviembre de 1991, Santos entró en la villa del rey en Roma haciéndose pasar por periodista y trató de apuñalarlo con una daga. Una lata de cigarrillos en el bolsillo del pecho del rey desvió la hoja y salvó la vida de Zahir Shah, aunque el rey también fue apuñalado varias veces en el cuello y fue llevado al hospital, recuperándose más tarde del ataque. Santos fue detenido por el general Abdul Wali, ex comandante del Ejército Real Afgano , y encarcelado durante 10 años en Italia. [221] [222]

El 29 de diciembre de 1992, Al Qaeda llevó a cabo los atentados con bombas en hoteles de Yemen de 1992. Dos bombas detonaron en Adén , Yemen. El primer objetivo fue el Hotel Movenpick y el segundo, el aparcamiento del Hotel Goldmohur. [223]

Los bombardeos fueron un intento de eliminar a los soldados estadounidenses que se dirigían a Somalia para participar en el esfuerzo internacional de ayuda contra la hambruna, la Operación Restaurar la Esperanza . Internamente, Al Qaeda consideró el bombardeo como una victoria que ahuyentó a los estadounidenses, pero en Estados Unidos, el ataque apenas se notó. Ningún soldado estadounidense murió porque no había soldados alojados en el hotel en el momento en que fue bombardeado, sin embargo, un turista australiano y un trabajador del hotel yemení murieron en el bombardeo. Otros siete, que en su mayoría eran yemeníes, resultaron gravemente heridos. [223] Se dice que los miembros de Al Qaeda, Mamdouh Mahmud Salim , designaron dos fatwas para justificar los asesinatos según la ley islámica. Salim se refirió a una famosa fatwa designada por Ibn Taymiyyah , un erudito del siglo XIII admirado por los wahabíes, que sancionaba la resistencia por cualquier medio durante las invasiones mongolas. [224] [ ¿ Fuente poco fiable? ]

En 1996, Bin Laden diseñó personalmente un complot para asesinar al presidente estadounidense Bill Clinton mientras éste se encontraba en Manila para la Cooperación Económica Asia-Pacífico . Sin embargo, agentes de inteligencia interceptaron un mensaje antes de que la caravana partiera y alertaron al Servicio Secreto de Estados Unidos . Los agentes descubrieron más tarde una bomba colocada debajo de un puente. [225]

El 7 de agosto de 1998, Al Qaeda bombardeó las embajadas de Estados Unidos en África Oriental , matando a 224 personas, entre ellas 12 estadounidenses. En represalia, una andanada de misiles de crucero lanzados por el ejército estadounidense devastó una base de Al Qaeda en Khost , Afganistán. La capacidad de la red salió indemne. A finales de 1999 y 2000, Al Qaeda planeó atentados para coincidir con el milenio , ideados por Abu Zubaydah y en los que participó Abu Qatada , que incluirían el bombardeo de lugares sagrados cristianos en Jordania, el bombardeo del Aeropuerto Internacional de Los Ángeles por Ahmed Ressam y el bombardeo del USS The Sullivans (DDG-68) .

El 12 de octubre de 2000, militantes de Al Qaeda en Yemen bombardearon el destructor de misiles USS Cole en un ataque suicida, matando a 17 militares estadounidenses y dañando el buque mientras se encontraba en alta mar. Inspirado por el éxito de un ataque tan descarado, el núcleo de mando de Al Qaeda comenzó a prepararse para un ataque contra los propios Estados Unidos.

Los ataques del 11 de septiembre en Estados Unidos perpetrados por Al Qaeda mataron a 2.996 personas: 2.507 civiles, 343 bomberos, 72 agentes de la ley, 55 militares y 19 secuestradores que cometieron asesinatos y suicidios. Dos aviones comerciales fueron estrellados deliberadamente contra las torres gemelas del World Trade Center, un tercero contra el Pentágono y un cuarto, que originalmente tenía como objetivo el Capitolio de los Estados Unidos o la Casa Blanca , se estrelló en un campo en Stonycreek Township, cerca de Shanksville, Pensilvania, después de que los pasajeros se rebelaran. Fue el ataque extranjero más mortífero en suelo estadounidense desde el ataque japonés a Pearl Harbor el 7 de diciembre de 1941, y hasta el día de hoy sigue siendo el ataque terrorista más mortífero de la historia de la humanidad.

Los ataques fueron llevados a cabo por Al Qaeda, actuando de acuerdo con la fatwa de 1998 emitida contra los EE. UU. y sus aliados por personas bajo el mando de Bin Laden, Al Zawahiri y otros. [30] La evidencia apunta a escuadrones suicidas liderados por el comandante militar de Al Qaeda, Mohamed Atta, como los culpables de los ataques, con Bin Laden, Ayman Al Zawahiri, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed y Hambali como los planificadores clave y parte del comando político y militar.

Los mensajes emitidos por Bin Laden después del 11 de septiembre de 2001 elogiaban los ataques y explicaban su motivación, al tiempo que negaban cualquier implicación. [226] Bin Laden apoyó firmemente los ataques identificando numerosas quejas de los musulmanes, como la percepción general de que Estados Unidos estaba oprimiendo activamente a los musulmanes. [227] En su " Carta al pueblo estadounidense " publicada en 2002, Osama Bin Laden afirmó:

¿Por qué luchamos y nos oponemos a ustedes? La respuesta es muy sencilla:

(1) Porque nos atacaron y continúan atacándonos. ....

El gobierno y la prensa estadounidenses todavía se niegan a responder a la pregunta: ¿Por qué nos atacaron en Nueva York y Washington?

Si Sharon es un hombre de paz a los ojos de Bush , entonces nosotros también somos hombres de paz. Estados Unidos no entiende el lenguaje de los modales y los principios, por eso nos dirigimos a él utilizando el lenguaje que entiende. [29] [228]

Bin Laden afirmó que Estados Unidos estaba masacrando a musulmanes en " Palestina , Chechenia , Cachemira e Irak " y que los musulmanes debían conservar el "derecho a atacar en represalia". También afirmó que los ataques del 11 de septiembre no estaban dirigidos contra personas, sino contra "iconos estadounidenses del poder militar y económico", a pesar de que planeaba atacar por la mañana, cuando la mayoría de las personas en los objetivos previstos estaban presentes y, por lo tanto, se generaba el máximo número de víctimas humanas. [229]

Más tarde se revelaron pruebas de que los objetivos originales del ataque podrían haber sido centrales nucleares en la costa este de Estados Unidos. Al Qaeda modificó posteriormente los objetivos, ya que se temía que un ataque de ese tipo "pudiera salirse de control". [230] [231]

Al Qaeda está considerado como un grupo terrorista por los siguientes países y organizaciones internacionales:

Inmediatamente después de los ataques del 11 de septiembre, el gobierno de Estados Unidos respondió y comenzó a preparar a sus fuerzas armadas para derrocar a los talibanes, que creía que estaban albergando a Al Qaeda. Estados Unidos ofreció al líder talibán, Mullah Omar, la oportunidad de entregar a Bin Laden y a sus principales colaboradores. Las primeras fuerzas que se enviaron a Afganistán fueron oficiales paramilitares de la División de Actividades Especiales (SAD) de la CIA .

Los talibanes se ofrecieron a entregar a Bin Laden a un país neutral para que fuera juzgado si Estados Unidos proporcionaba pruebas de su complicidad en los ataques. El presidente estadounidense George W. Bush respondió diciendo: "Sabemos que es culpable. Entréguenlo" [271] y el primer ministro británico Tony Blair advirtió al régimen talibán: "Entreguen a Bin Laden o entreguen el poder" [272] .

Poco después, Estados Unidos y sus aliados invadieron Afganistán y, junto con la Alianza del Norte de Afganistán, derrocaron al gobierno talibán como parte de la guerra en Afganistán . Como resultado de las fuerzas especiales y el apoyo aéreo de Estados Unidos a las fuerzas terrestres de la Alianza del Norte, se destruyeron varios campos de entrenamiento de los talibanes y de Al Qaeda , y se cree que gran parte de la estructura operativa de Al Qaeda quedó desbaratada. Después de ser expulsados de sus posiciones clave en la zona de Tora Bora en Afganistán, muchos combatientes de Al Qaeda intentaron reagruparse en la accidentada región de Gardez del país.

A principios de 2002, la capacidad operativa de Al Qaeda había sufrido un duro golpe y la invasión afgana parecía un éxito. No obstante, en Afganistán seguía habiendo una importante insurgencia talibán .

El debate sobre la naturaleza del papel de Al Qaeda en los ataques del 11 de septiembre continuó. El Departamento de Estado de los EE. UU. publicó una cinta de vídeo que mostraba a Bin Laden hablando con un pequeño grupo de asociados en algún lugar de Afganistán poco antes de que los talibanes fueran derrocados del poder. [273] Aunque un par de personas han cuestionado su autenticidad, [274] la cinta implica definitivamente a Bin Laden y Al Qaeda en los ataques del 11 de septiembre. La cinta fue emitida en muchos canales de televisión , con una traducción al inglés proporcionada por el Departamento de Defensa de los EE . UU . [275]

In September 2004, the 9/11 Commission officially concluded that the attacks were conceived and implemented by al-Qaeda operatives.[276] In October 2004, bin Laden appeared to claim responsibility for the attacks in a videotape released through Al Jazeera, saying he was inspired by Israeli attacks on high-rises in the 1982 invasion of Lebanon: "As I looked at those demolished towers in Lebanon, it entered my mind that we should punish the oppressor in kind and that we should destroy towers in America in order that they taste some of what we tasted and so that they be deterred from killing our women and children."[277]

By the end of 2004, the US government proclaimed that two-thirds of the most senior al-Qaeda figures from 2001 had been captured and interrogated by the CIA: Abu Zubaydah, Ramzi bin al-Shibh and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri in 2002;[278] Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in 2003;[279] and Saif al Islam el Masry in 2004.[280] Mohammed Atef and several others were killed. The West was criticized for not being able to handle al-Qaeda despite a decade of the war.[281]

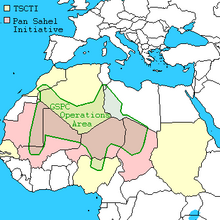

Al-Qaeda involvement in Africa has included a number of bombing attacks in North Africa, while supporting parties in civil wars in Eritrea and Somalia. From 1991 to 1996, bin Laden and other al-Qaeda leaders were based in Sudan.

Islamist rebels in the Sahara calling themselves al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb have stepped up their violence in recent years.[282][283][284] French officials say the rebels have no real links to the al-Qaeda leadership, but this has been disputed. It seems likely that bin Laden approved the group's name in late 2006, and the rebels "took on the al Qaeda franchise label", almost a year before the violence began to escalate.[285]

In Mali, the Ansar Dine faction was also reported as an ally of al-Qaeda in 2013.[286] The Ansar al Dine faction aligned themselves with the AQIM.[287]

In 2011, al-Qaeda's North African wing condemned Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi and declared support for the Anti-Gaddafi rebels.[288][289]

Following the Libyan Civil War, the removal of Gaddafi and the ensuing period of post-civil war violence in Libya, various Islamist militant groups affiliated with al-Qaeda were able to expand their operations in the region.[290] The 2012 Benghazi attack, which resulted in the death of US Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and three other Americans, is suspected of having been carried out by various Jihadist networks, such as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, Ansar al-Sharia and several other al-Qaeda affiliated groups.[291][292] The capture of Nazih Abdul-Hamed al-Ruqai, a senior al-Qaeda operative wanted by the United States for his involvement in the 1998 United States embassy bombings, on October 5, 2013, by US Navy Seals, FBI and CIA agents illustrates the importance the US and other Western allies have placed on North Africa.[293]

Prior to the September 11 attacks, al-Qaeda was present in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and its members were mostly veterans of the El Mudžahid detachment of the Bosnian Muslim Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Three al-Qaeda operatives carried out the Mostar car bombing in 1997. The operatives were closely linked to and financed by the Saudi High Commission for Relief of Bosnia and Herzegovina founded by then-prince King Salman of Saudi Arabia.[citation needed]

Before the 9/11 attacks and the US invasion of Afghanistan, westerners who had been recruits at al-Qaeda training camps were sought after by al-Qaeda's military wing. Language skills and knowledge of Western culture were generally found among recruits from Europe, such was the case with Mohamed Atta, an Egyptian national studying in Germany at the time of his training, and other members of the Hamburg Cell. Osama bin Laden and Mohammed Atef would later designate Atta as the ringleader of the 9/11 hijackers. Following the attacks, Western intelligence agencies determined that al-Qaeda cells operating in Europe had aided the hijackers with financing and communications with the central leadership based in Afghanistan.[177][294]

In 2003, Islamists carried out a series of bombings in Istanbul killing fifty-seven people and injuring seven hundred. Seventy-four people were charged by the Turkish authorities. Some had previously met bin Laden, and though they specifically declined to pledge allegiance to al-Qaeda they asked for its blessing and help.[295][296]

In 2009, three Londoners, Tanvir Hussain, Assad Sarwar and Ahmed Abdullah Ali, were convicted of conspiring to detonate bombs disguised as soft drinks on seven airplanes bound for Canada and the US. The MI5 investigation regarding the plot involved more than a year of surveillance work conducted by over two hundred officers.[297][298][299] British and US officials said the plot – unlike many similar homegrown European Islamic militant plots – was directly linked to al-Qaeda and guided by senior al-Qaeda members in Pakistan.[300][301]

In 2012, Russian Intelligence indicated that al-Qaeda had given a call for "forest jihad" and has been starting massive forest fires as part of a strategy of "thousand cuts".[302]

Following Yemeni unification in 1990, Wahhabi networks began moving missionaries into the country. Although it is unlikely bin Laden or Saudi al-Qaeda were directly involved, the personal connections they made would be established over the next decade and used in the USS Cole bombing.[303] Concerns grew over al-Qaeda's group in Yemen.[304]

In Iraq, al-Qaeda forces loosely associated with the leadership were embedded in the Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad group commanded by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Specializing in suicide operations, they have been a "key driver" of the Sunni insurgency.[305] Although they played a small part in the overall insurgency, between 30% and 42% of all suicide bombings which took place in the early years were claimed by Zarqawi's group.[306][307] Reports have indicated that oversights such as the failure to control access to the Qa'qaa munitions factory in Yusufiyah have allowed large quantities of munitions to fall into the hands of al-Qaida.[308] In November 2010, the militant group Islamic State of Iraq, which is linked to al-Qaeda in Iraq, threatened to "exterminate all Iraqi Christians".[309][310]

Al-Qaeda did not begin training Palestinians until the late 1990s.[311] Large groups such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad have rejected an alliance with al-Qaeda, fearing that al-Qaeda will co-opt their cells. This may have changed recently. The Israeli security and intelligence services believe al-Qaeda has managed to infiltrate operatives from the Occupied Territories into Israel, and is waiting for an opportunity to attack.[311]

As of 2015[update], Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey are openly supporting the Army of Conquest,[312][313] an umbrella rebel group fighting in the Syrian Civil War against the Syrian government that reportedly includes an al-Qaeda linked al-Nusra Front and another Salafi coalition known as Ahrar al-Sham.[314]

Bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri consider India to be a part of an alleged Crusader-Zionist-Hindu conspiracy against the Islamic world.[315] According to a 2005 report by the Congressional Research Service, bin Laden was involved in training militants for Jihad in Kashmir while living in Sudan in the early 1990s. By 2001, Kashmiri militant group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen had become a part of the al-Qaeda coalition.[316] According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), al-Qaeda was thought to have established bases in Pakistan administered Kashmir (in Azad Kashmir, and to some extent in Gilgit–Baltistan) during the 1999 Kargil War and continued to operate there with tacit approval of Pakistan's Intelligence services.[317]

Many of the militants active in Kashmir were trained in the same madrasahs as Taliban and al-Qaeda. Fazlur Rehman Khalil of Kashmiri militant group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen was a signatory of al-Qaeda's 1998 declaration of Jihad against America and its allies.[318] In a 'Letter to American People' (2002), bin Laden wrote that one of the reasons he was fighting America was because of its support to India on the Kashmir issue.[29] In November 2001, Kathmandu airport went on high alert after threats that bin Laden planned to hijack a plane and crash it into a target in New Delhi.[319] In 2002, US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, on a trip to Delhi, suggested that al-Qaeda was active in Kashmir though he did not have any evidence.[320][321] Rumsfeld proposed hi-tech ground sensors along the Line of Control to prevent militants from infiltrating into Indian-administered Kashmir.[321]An investigation in 2002 found evidence that al-Qaeda and its affiliates were prospering in Pakistan-administered Kashmir with tacit approval of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence.[322] In 2002, a special team of Special Air Service and Delta Force was sent into Indian-administered Kashmir to hunt for bin Laden after receiving reports that he was being sheltered by Kashmiri militant group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, which had been responsible for kidnapping western tourists in Kashmir in 1995.[323] Britain's highest-ranking al-Qaeda operative Rangzieb Ahmed had previously fought in Kashmir with the group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen and spent time in Indian prison after being captured in Kashmir.[324]

US officials believe al-Qaeda was helping organize attacks in Kashmir in order to provoke conflict between India and Pakistan.[325] Their strategy was to force Pakistan to move its troops to the border with India, thereby relieving pressure on al-Qaeda elements hiding in northwestern Pakistan.[326] In 2006 al-Qaeda claimed they had established a wing in Kashmir.[318][327] However Indian Army General H. S. Panag argued that the army had ruled out the presence of al-Qaeda in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir. Panag also said al-Qaeda had strong ties with Kashmiri militant groups Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed based in Pakistan.[328] It has been noted that Waziristan has become a battlefield for Kashmiri militants fighting NATO in support of al-Qaeda and Taliban.[329][330][331] Dhiren Barot, who wrote the Army of Madinah in Kashmir[332] and was an al-Qaeda operative convicted for involvement in the 2004 financial buildings plot, had received training in weapons and explosives at a militant training camp in Kashmir.[333]

Maulana Masood Azhar, the founder of Kashmiri group Jaish-e-Mohammed, is believed to have met bin Laden several times and received funding from him.[318] In 2002, Jaish-e-Mohammed organized the kidnapping and murder of Daniel Pearl in an operation run in conjunction with al-Qaeda and funded by bin Laden.[334] According to American counter-terrorism expert Bruce Riedel, al-Qaeda and Taliban were closely involved in the 1999 hijacking of Indian Airlines Flight 814 to Kandahar which led to the release of Maulana Masood Azhar and Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh from an Indian prison. This hijacking, Riedel said, was rightly described by then Indian Foreign Minister Jaswant Singh as a 'dress rehearsal' for September 11 attacks.[335] Bin Laden personally welcomed Azhar and threw a lavish party in his honor after his release.[336][337] Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, who had been in prison for his role in the 1994 kidnappings of Western tourists in India, went on to murder Daniel Pearl and was sentenced to death in Pakistan. Al-Qaeda operative Rashid Rauf, who was one of the accused in 2006 transatlantic aircraft plot, was related to Maulana Masood Azhar by marriage.[338]

Lashkar-e-Taiba, a Kashmiri militant group which is thought to be behind 2008 Mumbai attacks, is also known to have strong ties to senior al-Qaeda leaders living in Pakistan.[339] In late 2002, top al-Qaeda operative Abu Zubaydah was arrested while being sheltered by Lashkar-e-Taiba in a safe house in Faisalabad.[340] The FBI believes al-Qaeda and Lashkar have been 'intertwined' for a long time while the CIA has said that al-Qaeda funds Lashkar-e-Taiba.[340] Jean-Louis Bruguière told Reuters in 2009 that "Lashkar-e-Taiba is no longer a Pakistani movement with only a Kashmir political or military agenda. Lashkar-e-Taiba is a member of al-Qaeda."[341][342]

In a video released in 2008, American-born senior al-Qaeda operative Adam Yahiye Gadahn said that "victory in Kashmir has been delayed for years; it is the liberation of the jihad there from this interference which, Allah willing, will be the first step towards victory over the Hindu occupiers of that Islam land."[343]

In September 2009, a US drone strike reportedly killed Ilyas Kashmiri who was the chief of Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami, a Kashmiri militant group associated with al-Qaeda.[344] Kashmiri was described by Bruce Riedel as a 'prominent' al-Qaeda member[345] while others have described him as head of military operations for al-Qaeda.[346][347] Kashmiri was also charged by the US in a plot against Jyllands-Posten, the Danish newspaper which was at the center of Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy.[348] US officials also believe that Kashmiri was involved in the Camp Chapman attack against the CIA.[349] In January 2010, Indian authorities notified Britain of an al-Qaeda plot to hijack an Indian airlines or Air India plane and crash it into a British city. This information was uncovered from interrogation of Amjad Khwaja, an operative of Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami, who had been arrested in India.[350]

In January 2010, US Defense secretary Robert Gates, while on a visit to Pakistan, said that al-Qaeda was seeking to destabilize the region and planning to provoke a nuclear war between India and Pakistan.[351]

Al-Qaeda and its successors have migrated online to escape detection in an atmosphere of increased international vigilance. The group's use of the Internet has grown more sophisticated, with online activities that include financing, recruitment, networking, mobilization, publicity, and information dissemination, gathering and sharing.[352]

Abu Ayyub al-Masri's al-Qaeda movement in Iraq regularly releases short videos glorifying the activity of jihadist suicide bombers. In addition, both before and after the death of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi (the former leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq), the umbrella organization to which al-Qaeda in Iraq belongs, the Mujahideen Shura Council, has a regular presence on the Web.

The range of multimedia content includes guerrilla training clips, stills of victims about to be murdered, testimonials of suicide bombers, and videos that show participation in jihad through stylized portraits of mosques and musical scores. A website associated with al-Qaeda posted a video of captured American entrepreneur Nick Berg being decapitated in Iraq. Other decapitation videos and pictures, including those of Paul Johnson, Kim Sun-il (posted on websites),[353] and Daniel Pearl obtained by investigators, have taken place.[354]

In December 2004 an audio message claiming to be from bin Laden was posted directly to a website, rather than sending a copy to al Jazeera as he had done in the past. Al-Qaeda turned to the Internet for release of its videos in order to be certain they would be available unedited, rather than risk the possibility of al Jazeera editing out anything critical of the Saudi royal family.[355]

Alneda.com and Jehad.net were perhaps the most significant al-Qaeda websites. Alneda was initially taken down by American Jon Messner, but the operators resisted by shifting the site to various servers and strategically shifting content.[citation needed]

The US government charged a British information technology specialist, Babar Ahmad, with terrorist offences related to his operating a network of English-language al-Qaeda websites, such as Azzam.com. He was convicted and sentenced to 12+1⁄2 years in prison.[356][357][358]

In 2007, al-Qaeda released Mujahedeen Secrets, encryption software used for online and cellular communications. A later version, Mujahideen Secrets 2, was released in 2008.[359]

Al-Qaeda is believed to be operating a clandestine aviation network including "several Boeing 727 aircraft", turboprops and executive jets, according to a 2010 Reuters story. Based on a US Department of Homeland Security report, the story said al-Qaeda is possibly using aircraft to transport drugs and weapons from South America to various unstable countries in West Africa. A Boeing 727 can carry up to ten tons of cargo. The drugs eventually are smuggled to Europe for distribution and sale, and the weapons are used in conflicts in Africa and possibly elsewhere. Gunmen with links to al-Qaeda have been increasingly kidnapping Europeans for ransom. The profits from the drug and weapon sales, and kidnappings can, in turn, fund more militant activities.[360]

The following is a list of military conflicts in which al-Qaeda and its direct affiliates have taken part militarily.

Experts debate the notion that the al-Qaeda attacks were an indirect consequence of the American CIA's Operation Cyclone program to help the Afghan mujahideen. Robin Cook, British Foreign Secretary from 1997 to 2001, has written that al-Qaeda and bin Laden were "a product of a monumental miscalculation by western security agencies", and that "Al-Qaida, literally 'the database', was originally the computer file of the thousands of mujahideen who were recruited and trained with help from the CIA to defeat the Russians."[364]

Munir Akram, Permanent Representative of Pakistan to the United Nations from 2002 to 2008, wrote in a letter published in The New York Times on January 19, 2008:

The strategy to support the Afghans against Soviet military intervention was evolved by several intelligence agencies, including the C.I.A. and Inter-Services Intelligence, or ISI. After the Soviet withdrawal, the Western powers walked away from the region, leaving behind 40,000 militants imported from several countries to wage the anti-Soviet jihad. Pakistan was left to face the blowback of extremism, drugs and guns.[365]

CNN journalist Peter Bergen, Pakistani ISI Brigadier Mohammad Yousaf, and CIA operatives involved in the Afghan program, such as Vincent Cannistraro,[366] deny that the CIA or other American officials had contact with the foreign mujahideen or bin Laden, or that they armed, trained, coached or indoctrinated them. In his 2004 book Ghost Wars, Steve Coll writes that the CIA had contemplated providing direct support to the foreign mujahideen, but that the idea never moved beyond discussions.[367]

Bergen and others[who else?] argue that there was no need to recruit foreigners unfamiliar with the local language, customs or lay of the land since there were a quarter of a million local Afghans willing to fight.[367][failed verification] Bergen further argues that foreign mujahideen had no need for American funds since they received several million dollars per year from internal sources. Lastly, he argues that Americans could not have trained the foreign mujahideen because Pakistani officials would not allow more than a handful of them to operate in Pakistan and none in Afghanistan, and the Afghan Arabs were almost invariably militant Islamists reflexively hostile to Westerners whether or not the Westerners were helping the Muslim Afghans.

According to Bergen, who conducted the first television interview with bin Laden in 1997: the idea that "the CIA funded bin Laden or trained bin Laden ... [is] a folk myth. There's no evidence of this ... Bin Laden had his own money, he was anti-American and he was operating secretly and independently ... The real story here is the CIA didn't really have a clue about who this guy was until 1996 when they set up a unit to really start tracking him."[368]

Jason Burke also wrote:

Some of the $500 million the CIA poured into Afghanistan reached [Al-Zawahiri's] group. Al-Zawahiri has become a close aide of bin Laden ... Bin Laden was only loosely connected with the [Hezb-i-Islami faction of the mujahideen led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar], serving under another Hezb-i-Islami commander known as Engineer Machmud. However, bin Laden's Office of Services, set up to recruit overseas for the war, received some US cash.[369]

Anders Behring Breivik, the perpetrator of the 2011 Norway attacks, was inspired by al-Qaeda, calling it "the most successful revolutionary movement in the world." While admitting different aims, he sought to "create a European version of Al-Qaida."[370][371]

The appropriate response to offshoots is a subject of debate. A journalist reported in 2012 that a senior US military planner had asked: "Should we resort to drones and Special Operations raids every time some group raises the black banner of al Qaeda? How long can we continue to chase offshoots of offshoots around the world?"[372]

According to CNN journalists Peter Bergen and Paul Cruickshank, a number of "religious scholars, former fighters and militants" who previously supported Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) had turned against the al-Qaeda-supported Iraqi insurgency in 2008; due to ISI's indiscriminate attacks against civilians while targeting US-led coalition forces. American military analyst Bruce Riedel wrote in 2008 that "a wave of revulsion" arose against ISI, which enabled US-allied Sons of Iraq faction to turn various tribal leaders in the Anbar region against the Iraqi insurgency. In response, Bin Laden and Zawahiri issued public statements urging Muslims to rally behind ISI leadership and support the armed struggle against American forces.[373]

In November 2007, former Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) member Noman Benotman responded with a public, open letter of criticism to Ayman al-Zawahiri, after persuading the imprisoned senior leaders of his former group to enter into peace negotiations with the Libyan regime. While Ayman al-Zawahiri announced the affiliation of the group with al-Qaeda in November 2007, the Libyan government released 90 members of the group from prison several months after "they were said to have renounced violence."[374]

In 2007, on the anniversary of the September 11 attacks,[375] the Saudi sheikh Salman al-Ouda delivered a personal rebuke to bin Laden. Al-Ouda addressed al-Qaeda's leader on television asking him:

My brother Osama, how much blood has been spilt? How many innocent people, children, elderly, and women have been killed ... in the name of al-Qaeda? Will you be happy to meet God Almighty carrying the burden of these hundreds of thousands or millions [of victims] on your back?[376]

According to Pew polls, support for al-Qaeda had dropped in the Muslim world in the years before 2008.[377] In Saudi Arabia, only ten percent had a favorable view of al-Qaeda, according to a December 2007 poll by Terror Free Tomorrow, a Washington-based think tank.[378]

In 2007, the imprisoned Dr. Fadl, who was an influential Afghan Arab and former associate of Ayman al-Zawahiri, withdrew his support from al-Qaeda and criticized the organization in his book Wathiqat Tarshid Al-'Aml Al-Jihadi fi Misr w'Al-'Alam (English: Rationalizing Jihad in Egypt and the World). In response, Al-Zawahiri accused Dr. Fadl of promoting "an Islam without jihad" that aligns with Western interests and wrote a nearly two hundred pages long treatise, titled "The Exoneration" which appeared on the Internet in March 2008. In his treatise, Zawahiri justified military strikes against US targets as retaliatory attacks to defend Muslim community against American aggression.[375]

In an online town hall forum conducted in December 2007, Zawahiri denied that al-Qaeda deliberately targeted innocents and accused the American coalition of killing innocent people.[379] Although once associated with al-Qaeda, in September 2009 LIFG completed a new "code" for jihad, a 417-page religious document entitled "Corrective Studies". Given its credibility and the fact that several other prominent Jihadists in the Middle East have turned against al-Qaeda, the LIFG's reversal may be an important step toward staunching al-Qaeda's recruitment.[380]

Bilal Abdul Kareem, an American journalist based in Syria created a documentary about al-Shabab, al-Qaeda's affiliate in Somalia. The documentary included interviews with former members of the group who stated their reasons for leaving al-Shabab. The members made accusations of segregation, lack of religious awareness and internal corruption and favoritism. In response to Kareem, the Global Islamic Media Front condemned Kareem, called him a liar, and denied the accusations from the former fighters.[381]

In mid-2014 after the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant declared that they had restored the Caliphate, an audio statement was released by the then-spokesman of the group Abu Muhammad al-Adnani claiming that "the legality of all emirates, groups, states, and organizations, becomes null by the expansion of the Caliphate's authority." The speech included a religious refutation of al-Qaeda for being too lenient regarding Shiites and their refusal to recognize the authority Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, al-Adnani specifically noting: "It is not suitable for a state to give allegiance to an organization." He also recalled a past instance in which Osama bin Laden called on al-Qaeda members and supporters to give allegiance to Abu Omar al-Baghdadi when the group was still solely operating in Iraq, as the Islamic State of Iraq, and condemned Ayman al-Zawahiri for not making this same claim for Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Zawahiri was encouraging factionalism and division between former allies of ISIL such as the al-Nusra Front.[382][383]