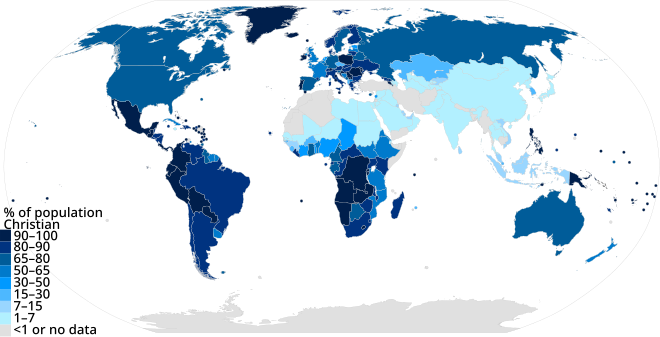

El cristianismo es una religión monoteísta abrahámica , que profesa que Jesucristo resucitó de entre los muertos y es el Hijo de Dios , [8] [9] [10] [nota 2] cuya venida como el Mesías fue profetizada en la Biblia hebrea (llamada Antiguo Testamento en el cristianismo) y narrada en el Nuevo Testamento . Es la religión más grande y extendida del mundo con más de 2.4 mil millones de seguidores, que comprenden alrededor del 31,2% de la población mundial . [11] Se estima que sus seguidores, conocidos como cristianos , constituyen la mayoría de la población en 157 países y territorios .

El cristianismo sigue siendo culturalmente diverso en sus ramas occidental y oriental , y doctrinalmente diverso en lo que respecta a la justificación y la naturaleza de la salvación , la eclesiología , la ordenación y la cristología . Los credos de varias denominaciones cristianas generalmente tienen en común a Jesús como el Hijo de Dios [nota 2] —el Logos encarnado— que ministró , sufrió y murió en una cruz , pero resucitó de entre los muertos para la salvación de la humanidad; y se lo conoce como el evangelio , que significa las "buenas noticias". Los cuatro evangelios canónicos de Mateo , Marcos , Lucas y Juan describen la vida y las enseñanzas de Jesús tal como se conservan en la tradición cristiana primitiva, con el Antiguo Testamento como el trasfondo respetado de los evangelios.

El cristianismo comenzó en el siglo I , después de la muerte de Jesús, como una secta judía con influencia helenística en la provincia romana de Judea . Los discípulos de Jesús difundieron su fe por el área del Mediterráneo oriental , a pesar de una persecución significativa . La inclusión de los gentiles llevó al cristianismo a separarse lentamente del judaísmo (siglo II). El emperador Constantino I despenalizó el cristianismo en el Imperio romano mediante el Edicto de Milán (313), convocando más tarde el Concilio de Nicea (325) donde el cristianismo primitivo se consolidó en lo que se convertiría en la religión estatal del Imperio romano (380). La Iglesia de Oriente y la Ortodoxia Oriental se dividieron por diferencias en la cristología (siglo V), mientras que la Iglesia Ortodoxa Oriental y la Iglesia Católica se separaron en el Cisma Este-Oeste (1054). El protestantismo se dividió en numerosas denominaciones de la Iglesia Católica en la era de la Reforma (siglo XVI). Después de la Era de los Descubrimientos (siglos XV-XVII), el cristianismo se expandió por todo el mundo a través del trabajo misionero , la evangelización , la inmigración y el comercio extensivo. El cristianismo jugó un papel destacado en el desarrollo de la civilización occidental , particularmente en Europa desde la Antigüedad tardía y la Edad Media . [12] [13] [14]

Las seis ramas principales del cristianismo son el catolicismo romano (1.300 millones de personas), el protestantismo (1.170 millones), [nota 3] [16] [17] [18] la ortodoxia oriental (230 millones), la ortodoxia oriental (60 millones), el restauracionismo (35 millones), [nota 4] y la Iglesia de Oriente (600.000). [21] Las comunidades eclesiásticas más pequeñas se cuentan por miles a pesar de los esfuerzos por la unidad ( ecumenismo ). En Occidente , el cristianismo sigue siendo la religión dominante incluso con un descenso en la adhesión , con aproximadamente el 70% de esa población identificándose como cristiana. El cristianismo está creciendo en África y Asia , los continentes más poblados del mundo. Los cristianos siguen siendo muy perseguidos en muchas regiones del mundo, particularmente en Oriente Medio , el norte de África , el este de Asia y el sur de Asia .

Los primeros cristianos judíos se referían a sí mismos como 'El Camino' ( griego koiné : τῆς ὁδοῦ , romanizado: tês hodoû ), probablemente proveniente de Isaías 40:3 , "preparad el camino del Señor". [nota 5] Según Hechos 11:26 , el término "cristiano" ( Χρῑστῐᾱνός , Khrīstiānós ), que significa "seguidores de Cristo" en referencia a los discípulos de Jesús , fue utilizado por primera vez en la ciudad de Antioquía por los habitantes no judíos allí. [27] El primer uso registrado del término "cristianismo" ( Χρῑστῐᾱνισμός , Khrīstiānismós ) fue por Ignacio de Antioquía alrededor del año 100 d . C. [28] El nombre Jesús proviene del griego : Ἰησοῦς Iēsous , probablemente del hebreo / arameo : יֵשׁוּעַ Yēšūaʿ.

El cristianismo se desarrolló durante el siglo I d. C. como una secta cristiana judía con influencia helenística [29] del judaísmo del Segundo Templo . [30] [31] Una comunidad cristiana judía primitiva se fundó en Jerusalén bajo el liderazgo de los Pilares de la Iglesia , a saber, Santiago el Justo , el hermano de Jesús, Pedro y Juan. [32]

El cristianismo judío pronto atrajo a los gentiles temerosos de Dios, lo que planteó un problema para su perspectiva religiosa judía , que insistía en la estricta observancia de los mandamientos judíos. El apóstol Pablo resolvió esto insistiendo en que la salvación por la fe en Cristo y la participación en su muerte y resurrección por medio del bautismo eran suficientes. [33] Al principio persiguió a los primeros cristianos, pero después de una experiencia de conversión predicó a los gentiles y se considera que tuvo un efecto formativo en la identidad cristiana emergente como separada del judaísmo. Finalmente, su alejamiento de las costumbres judías daría como resultado el establecimiento del cristianismo como una religión independiente. [34]

A este período formativo le siguieron los primeros obispos , a quienes los cristianos consideran los sucesores de los apóstoles de Cristo . A partir del año 150, los maestros cristianos comenzaron a producir obras teológicas y apologéticas destinadas a defender la fe. Estos autores son conocidos como los Padres de la Iglesia , y el estudio de ellos se llama patrística . Entre los primeros Padres notables se encuentran Ignacio de Antioquía , Policarpo , Justino Mártir , Ireneo , Tertuliano , Clemente de Alejandría y Orígenes .

La persecución de los cristianos se produjo de forma intermitente y en pequeña escala por parte de las autoridades tanto judías como romanas , y la acción romana comenzó en la época del Gran Incendio de Roma en el año 64 d. C. Entre los ejemplos de las primeras ejecuciones bajo la autoridad judía reportadas en el Nuevo Testamento se incluyen las muertes de San Esteban [35] y Santiago, hijo de Zebedeo . [36] La persecución de Decio fue el primer conflicto a nivel imperial, [37] cuando el edicto de Decio en el año 250 d. C. exigió que todos en el Imperio Romano (excepto los judíos) realizaran un sacrificio a los dioses romanos. La persecución de Diocleciano, que comenzó en el año 303 d. C., también fue particularmente severa. La persecución romana terminó en el año 313 d. C. con el Edicto de Milán .

Mientras el cristianismo proto-ortodoxo se estaba volviendo dominante, también existían al mismo tiempo sectas heterodoxas, que sostenían creencias radicalmente diferentes. El cristianismo gnóstico desarrolló una doctrina duoteísta basada en la ilusión y la iluminación en lugar del perdón de los pecados. Con solo unas pocas escrituras que se superponían con el canon ortodoxo en desarrollo, la mayoría de los textos gnósticos y los evangelios gnósticos finalmente fueron considerados heréticos y suprimidos por los cristianos convencionales. Una división gradual del cristianismo gentil dejó a los cristianos judíos que seguían siguiendo la Ley de Moisés , incluidas prácticas como la circuncisión. Para el siglo V, ellos y los evangelios judeo-cristianos serían suprimidos en gran medida por las sectas dominantes tanto en el judaísmo como en el cristianismo.

El cristianismo se extendió a los pueblos de habla aramea a lo largo de la costa mediterránea y también a las partes interiores del Imperio romano y más allá de eso al Imperio parto y el posterior Imperio sasánida , incluida Mesopotamia , que fue dominada en diferentes momentos y en diversos grados por estos imperios. [39] La presencia del cristianismo en África comenzó a mediados del siglo I en Egipto y hacia fines del siglo II en la región alrededor de Cartago . Se afirma que Marcos el Evangelista inició la Iglesia de Alejandría alrededor del 43 d. C.; varias iglesias posteriores afirman esto como su propio legado, incluida la Iglesia Ortodoxa Copta . [40] [41] [42] Los africanos importantes que influyeron en el desarrollo temprano del cristianismo incluyen a Tertuliano , Clemente de Alejandría , Orígenes de Alejandría , Cipriano , Atanasio y Agustín de Hipona .

El rey Tiridates III hizo del cristianismo la religión estatal de Armenia a principios del siglo IV d. C., convirtiendo a Armenia en el primer estado oficialmente cristiano. [43] [44] No era una religión completamente nueva en Armenia, ya que había penetrado en el país al menos desde el siglo III, pero es posible que haya estado presente incluso antes. [45]

Constantino I fue expuesto al cristianismo en su juventud, y a lo largo de su vida su apoyo a la religión fue creciendo, culminando con el bautismo en su lecho de muerte. [46] Durante su reinado, la persecución de los cristianos sancionada por el estado terminó con el Edicto de Tolerancia en 311 y el Edicto de Milán en 313. En ese momento, el cristianismo todavía era una creencia minoritaria, que comprendía quizás solo el 5% de la población romana. [47] Influenciado por su consejero Mardonio , el sobrino de Constantino, Juliano, intentó sin éxito suprimir el cristianismo. [48] El 27 de febrero de 380, Teodosio I , Graciano y Valentiniano II establecieron el cristianismo niceno como la iglesia estatal del Imperio romano . [49] Tan pronto como se conectó con el estado, el cristianismo se enriqueció; la Iglesia solicitó donaciones de los ricos y ahora podía poseer tierras. [50]

Constantino también fue instrumental en la convocatoria del Primer Concilio de Nicea en 325, que buscó abordar el arrianismo y formuló el Credo de Nicea, que todavía se usa en el catolicismo , la ortodoxia oriental , el luteranismo , el anglicanismo y muchas otras iglesias protestantes . [51] [52] Nicea fue el primero de una serie de concilios ecuménicos , que definieron formalmente elementos críticos de la teología de la Iglesia, en particular en lo concerniente a la cristología . [53] La Iglesia de Oriente no aceptó el tercero y los siguientes concilios ecuménicos y todavía hoy está separada por sus sucesores ( Iglesia Asiria de Oriente ).

En términos de prosperidad y vida cultural, el Imperio bizantino fue uno de los puntos culminantes de la historia y la civilización cristianas , [54] y Constantinopla siguió siendo la ciudad líder del mundo cristiano en tamaño, riqueza y cultura. [55] Hubo un renovado interés en la filosofía griega clásica , así como un aumento en la producción literaria en griego vernáculo. [56] El arte y la literatura bizantinos ocuparon un lugar preeminente en Europa, y el impacto cultural del arte bizantino en Occidente durante este período fue enorme y de importancia duradera. [57] El posterior ascenso del Islam en el norte de África redujo el tamaño y el número de congregaciones cristianas, dejando en gran número solo a la Iglesia copta en Egipto, la Iglesia ortodoxa etíope Tewahedo en el Cuerno de África y la Iglesia nubia en Sudán (Nobatia, Makuria y Alodia).

Con la decadencia y caída del Imperio Romano en Occidente , el papado se convirtió en un actor político, visible por primera vez en los tratos diplomáticos del Papa León con los hunos y los vándalos . [58] La iglesia también entró en un largo período de actividad misionera y expansión entre las diversas tribus. Mientras que los arrianistas instituyeron la pena de muerte para los paganos practicantes (véase la Masacre de Verden , por ejemplo), el catolicismo también se extendió entre los húngaros , los germánicos , [58] los celtas , los bálticos y algunos pueblos eslavos .

Alrededor del año 500, el cristianismo se integró completamente en la cultura bizantina y del Reino de Italia [59] y Benito de Nursia estableció su Regla Monástica , estableciendo un sistema de regulaciones para la fundación y el funcionamiento de los monasterios . [58] El monacato se convirtió en una fuerza poderosa en toda Europa, [58] y dio lugar a muchos de los primeros centros de aprendizaje, más famosos en Irlanda , Escocia y la Galia , contribuyendo al Renacimiento carolingio del siglo IX.

En el siglo VII, los musulmanes conquistaron Siria (incluida Jerusalén ), el norte de África y España, convirtiendo a una parte de la población cristiana al islam , incluidas algunas de las poblaciones cristianas de la Arabia preislámica , y colocando al resto bajo un estatus legal separado . Parte del éxito de los musulmanes se debió al agotamiento del Imperio bizantino en su conflicto de décadas con Persia . [60] A partir del siglo VIII, con el ascenso de los líderes carolingios , el papado buscó un mayor apoyo político en el reino franco . [61]

La Edad Media trajo consigo grandes cambios en la Iglesia. [62] [63] [64] [65] El Papa Gregorio Magno reformó radicalmente la estructura y la administración eclesiástica. [66] A principios del siglo VIII, la iconoclasia se convirtió en un tema divisivo, cuando fue patrocinada por los emperadores bizantinos . El Segundo Concilio Ecuménico de Nicea (787) finalmente se pronunció a favor de los iconos. [67] A principios del siglo X, el monacato cristiano occidental se rejuveneció aún más a través del liderazgo del gran monasterio benedictino de Cluny . [68]

En Occidente, a partir del siglo XI, algunas escuelas catedralicias más antiguas se convirtieron en universidades (véase, por ejemplo, la Universidad de Oxford , la Universidad de París y la Universidad de Bolonia ). Anteriormente, la educación superior había sido el dominio de las escuelas catedralicias cristianas o escuelas monásticas ( Scholae monasticae ), dirigidas por monjes y monjas . La evidencia de tales escuelas se remonta al siglo VI d. C. [69] Estas nuevas universidades ampliaron el plan de estudios para incluir programas académicos para clérigos, abogados, funcionarios públicos y médicos. [70] La universidad se considera generalmente como una institución que tiene su origen en el entorno cristiano medieval . [71] [72] [73]

Junto con el surgimiento de las "nuevas ciudades" en toda Europa, se fundaron órdenes mendicantes , que sacaron la vida religiosa consagrada del monasterio y la llevaron al nuevo entorno urbano. Los dos principales movimientos mendicantes fueron los franciscanos [74] y los dominicos [75], fundados por Francisco de Asís y Domingo , respectivamente. Ambas órdenes hicieron contribuciones significativas al desarrollo de las grandes universidades de Europa. Otra nueva orden fue la cisterciense , cuyos grandes monasterios aislados encabezaron la colonización de antiguas áreas silvestres. En este período, la construcción de iglesias y la arquitectura eclesiástica alcanzaron nuevas alturas, culminando en las órdenes de arquitectura románica y gótica y la construcción de las grandes catedrales europeas. [76]

El nacionalismo cristiano surgió durante esta era en la que los cristianos sintieron el deseo de recuperar tierras en las que históricamente había florecido el cristianismo. [77] A partir de 1095, bajo el pontificado de Urbano II , se lanzó la Primera Cruzada . [78] Se trató de una serie de campañas militares en Tierra Santa y otros lugares, iniciadas en respuesta a las súplicas del emperador bizantino Alejo I de ayuda contra la expansión turca . Las Cruzadas finalmente no lograron sofocar la agresión islámica e incluso contribuyeron a la enemistad cristiana con el saqueo de Constantinopla durante la Cuarta Cruzada . [79]

La Iglesia cristiana experimentó un conflicto interno entre los siglos VII y XIII que resultó en un cisma entre la rama de la Iglesia latina del cristianismo occidental , la actual Iglesia católica, y una rama oriental , en gran parte griega (la Iglesia ortodoxa oriental ). Las dos partes discreparon en una serie de cuestiones administrativas, litúrgicas y doctrinales, siendo la más destacada la oposición ortodoxa oriental a la supremacía papal . [80] [81] El Segundo Concilio de Lyon (1274) y el Concilio de Florencia (1439) intentaron reunificar las iglesias, pero en ambos casos, los ortodoxos orientales se negaron a implementar las decisiones, y las dos iglesias principales permanecen en cisma hasta el día de hoy. Sin embargo, la Iglesia católica ha logrado la unión con varias iglesias orientales más pequeñas .

En el siglo XIII, un nuevo énfasis en el sufrimiento de Jesús, ejemplificado por la predicación de los franciscanos, tuvo como consecuencia que los fieles se dirigieran hacia los judíos, a quienes los cristianos habían culpado de la muerte de Jesús . La limitada tolerancia del cristianismo hacia los judíos no era nueva (Agustín de Hipona dijo que no se debía permitir que los judíos disfrutaran de la ciudadanía que los cristianos daban por sentada), pero la creciente antipatía hacia los judíos fue un factor que llevó a la expulsión de los judíos de Inglaterra en 1290 , la primera de muchas expulsiones de ese tipo en Europa. [82] [83]

A partir de 1184 aproximadamente, después de la cruzada contra la herejía cátara , [84] se establecieron varias instituciones, conocidas ampliamente como la Inquisición , con el objetivo de suprimir la herejía y asegurar la unidad religiosa y doctrinal dentro del cristianismo a través de la conversión y el procesamiento. [85]

El Renacimiento del siglo XV trajo consigo un renovado interés por el saber antiguo y clásico. Durante la Reforma , Martín Lutero publicó en 1517 las Noventa y cinco tesis contra la venta de indulgencias . [86] Las copias impresas pronto se difundieron por toda Europa. En 1521, el Edicto de Worms condenó y excomulgó a Lutero y a sus seguidores, lo que dio lugar al cisma de la cristiandad occidental en varias ramas. [87]

Otros reformadores como Zwinglio , Ecolampadio , Calvino , Knox y Arminio criticaron aún más la enseñanza y el culto católicos. Estos desafíos se convirtieron en el movimiento llamado protestantismo , que repudió la primacía del papa , el papel de la tradición, los siete sacramentos y otras doctrinas y prácticas. [86] La Reforma en Inglaterra comenzó en 1534, cuando el rey Enrique VIII se declaró a sí mismo cabeza de la Iglesia de Inglaterra . A partir de 1536, se disolvieron los monasterios de toda Inglaterra, Gales e Irlanda . [88]

Thomas Müntzer , Andreas Karlstadt y otros teólogos percibieron que tanto la Iglesia católica como las confesiones de la Reforma Magistral estaban corrompidas. Su actividad provocó la Reforma Radical , que dio origen a varias denominaciones anabaptistas .

En parte como respuesta a la Reforma protestante, la Iglesia católica emprendió un importante proceso de reforma y renovación, conocido como la Contrarreforma o Reforma Católica. [92] El Concilio de Trento aclaró y reafirmó la doctrina católica. Durante los siglos siguientes, la competencia entre el catolicismo y el protestantismo se vio profundamente enredada con las luchas políticas entre los estados europeos. [93]

Mientras tanto, el descubrimiento de América por Cristóbal Colón en 1492 desencadenó una nueva oleada de actividad misionera. En parte por el celo misionero, pero bajo el impulso de la expansión colonial de las potencias europeas, el cristianismo se extendió a las Américas, Oceanía, Asia oriental y África subsahariana.

En toda Europa, la división causada por la Reforma condujo a brotes de violencia religiosa y al establecimiento de iglesias estatales separadas en Europa. El luteranismo se extendió a las partes norte, central y oriental de la actual Alemania, Livonia y Escandinavia. El anglicanismo se estableció en Inglaterra en 1534. El calvinismo y sus variedades, como el presbiterianismo , se introdujeron en Escocia, los Países Bajos, Hungría, Suiza y Francia. El arminianismo ganó seguidores en los Países Bajos y Frisia . En última instancia, estas diferencias llevaron al estallido de conflictos en los que la religión jugó un factor clave. La Guerra de los Treinta Años , la Guerra Civil Inglesa y las Guerras de Religión Francesas son ejemplos destacados. Estos eventos intensificaron el debate cristiano sobre la persecución y la tolerancia . [94]

En el resurgimiento del neoplatonismo, los humanistas renacentistas no rechazaron el cristianismo; todo lo contrario, muchas de las mayores obras del Renacimiento estaban dedicadas a él, y la Iglesia Católica patrocinó muchas obras de arte renacentista . [95] Gran parte, si no la mayor parte, del nuevo arte fue encargado por la Iglesia o en dedicación a ella. [95] Algunos eruditos e historiadores atribuyen al cristianismo haber contribuido al surgimiento de la Revolución científica . [96] Muchas figuras históricas conocidas que influyeron en la ciencia occidental se consideraban cristianas, como Nicolás Copérnico , [97] Galileo Galilei , [98] Johannes Kepler , [99] Isaac Newton [100] y Robert Boyle . [101]

En la era conocida como la Gran Divergencia , cuando en Occidente, la Era de la Ilustración y la revolución científica trajeron grandes cambios sociales, el cristianismo se enfrentó a diversas formas de escepticismo y a ciertas ideologías políticas modernas , como versiones del socialismo y el liberalismo . [102] Los eventos variaron desde el mero anticlericalismo hasta estallidos violentos contra el cristianismo, como la descristianización de Francia durante la Revolución Francesa , [103] la Guerra Civil Española y ciertos movimientos marxistas , especialmente la Revolución Rusa y la persecución de los cristianos en la Unión Soviética bajo el ateísmo de Estado . [104] [105] [106] [107]

Especialmente apremiante en Europa fue la formación de estados nacionales después de la era napoleónica . En todos los países europeos, diferentes denominaciones cristianas se encontraron en competencia en mayor o menor medida entre sí y con el estado. Las variables fueron los tamaños relativos de las denominaciones y la orientación religiosa, política e ideológica de los estados. Urs Altermatt de la Universidad de Friburgo , observando específicamente el catolicismo en Europa, identifica cuatro modelos para las naciones europeas. En países tradicionalmente de mayoría católica como Bélgica, España y Austria, hasta cierto punto, las comunidades religiosas y nacionales son más o menos idénticas. La simbiosis y separación cultural se encuentran en Polonia, la República de Irlanda y Suiza, todos países con denominaciones en competencia. La competencia se encuentra en Alemania, los Países Bajos y nuevamente Suiza, todos países con poblaciones católicas minoritarias, que en mayor o menor medida se identificaban con la nación. Finalmente, la separación entre la religión (nuevamente, específicamente el catolicismo) y el estado se encuentra en gran medida en Francia e Italia, países donde el estado se opuso activamente a la autoridad de la Iglesia Católica. [108]

Los factores combinados de la formación de los estados nacionales y del ultramontanismo , especialmente en Alemania y los Países Bajos, pero también en Inglaterra en un grado mucho menor, [109] obligaron a menudo a las iglesias, organizaciones y creyentes católicos a elegir entre las demandas nacionales del estado y la autoridad de la Iglesia, específicamente el papado. Este conflicto llegó a su punto álgido en el Primer Concilio Vaticano , y en Alemania conduciría directamente al Kulturkampf . [110]

El compromiso cristiano en Europa disminuyó a medida que la modernidad y el secularismo cobraron fuerza, [111] particularmente en la República Checa y Estonia , [112] mientras que los compromisos religiosos en Estados Unidos han sido generalmente altos en comparación con Europa. Los cambios en el cristianismo mundial durante el último siglo han sido significativos, desde 1900, el cristianismo se ha extendido rápidamente en el Sur Global y los países del Tercer Mundo. [113] El final del siglo XX ha mostrado el cambio de la adhesión cristiana al Tercer Mundo y al Hemisferio Sur en general, [114] [115] con Occidente ya no siendo el principal abanderado del cristianismo. Aproximadamente entre el 7 y el 10% de los árabes son cristianos , [116] más frecuentes en Egipto, Siria y Líbano .

Aunque los cristianos de todo el mundo comparten convicciones básicas, existen diferencias de interpretaciones y opiniones sobre la Biblia y las tradiciones sagradas en las que se basa el cristianismo. [117]

Las declaraciones doctrinales concisas o confesiones de creencias religiosas se conocen como credos . Comenzaron como fórmulas bautismales y luego se ampliaron durante las controversias cristológicas de los siglos IV y V para convertirse en declaraciones de fe. " Jesús es el Señor " es el credo más antiguo del cristianismo y continúa utilizándose, como en el caso del Consejo Mundial de Iglesias . [118]

El Credo de los Apóstoles es la declaración más ampliamente aceptada de los artículos de la fe cristiana. Es utilizado por varias denominaciones cristianas tanto con fines litúrgicos como catequéticos , más visiblemente por las iglesias litúrgicas de tradición cristiana occidental , incluyendo la Iglesia latina de la Iglesia católica , el luteranismo , el anglicanismo y la ortodoxia de rito occidental . También lo utilizan los presbiterianos , los metodistas y los congregacionalistas .

Este credo en particular se desarrolló entre los siglos II y IX. Sus doctrinas centrales son las de la Trinidad y Dios el Creador . Cada una de las doctrinas que se encuentran en este credo se puede rastrear hasta afirmaciones vigentes en el período apostólico . El credo aparentemente se utilizó como un resumen de la doctrina cristiana para los candidatos al bautismo en las iglesias de Roma. [119] Sus puntos incluyen:

El Credo de Nicea fue formulado, en gran medida como respuesta al arrianismo , en los Concilios de Nicea y Constantinopla en 325 y 381 respectivamente, [120] [121] y ratificado como el credo universal de la cristiandad por el Primer Concilio de Éfeso en 431. [122]

La Definición de Calcedonia , o Credo de Calcedonia, desarrollado en el Concilio de Calcedonia en 451, [123] aunque rechazado por los ortodoxos orientales , [124] enseñó que Cristo "debe ser reconocido en dos naturalezas, inconfundiblemente, inmutablemente, indivisiblemente, inseparablemente": una divina y una humana, y que ambas naturalezas, aunque perfectas en sí mismas, están sin embargo también perfectamente unidas en una persona . [125]

El Credo Atanasiano , recibido en la Iglesia occidental como teniendo el mismo estatus que el Niceno y el Calcedoniano, dice: "Adoramos a un solo Dios en Trinidad, y a la Trinidad en Unidad; sin confundir las Personas ni dividir la Sustancia ". [126]

La mayoría de los cristianos ( católicos , ortodoxos orientales , protestantes y no católicos ) aceptan el uso de credos y suscriben al menos uno de los credos mencionados anteriormente. [52]

Ciertos protestantes evangélicos , aunque no todos, rechazan los credos como declaraciones definitivas de fe, aun cuando están de acuerdo con parte o la totalidad de la esencia de los credos. También rechazan los credos grupos con raíces en el Movimiento de Restauración , como la Iglesia Cristiana (Discípulos de Cristo) , la Iglesia Cristiana Evangélica en Canadá y las Iglesias de Cristo . [127] [128] : 14–15 [129] : 123

El principio central del cristianismo es la creencia en Jesús como el Hijo de Dios [nota 2] y el Mesías (Cristo). [130] [131] Los cristianos creen que Jesús, como el Mesías, fue ungido por Dios como salvador de la humanidad y sostienen que la venida de Jesús fue el cumplimiento de las profecías mesiánicas del Antiguo Testamento . El concepto cristiano de mesías difiere significativamente del concepto judío contemporáneo . La creencia cristiana central es que a través de la creencia y la aceptación de la muerte y resurrección de Jesús , los humanos pecadores pueden reconciliarse con Dios y, por lo tanto, se les ofrece la salvación y la promesa de la vida eterna . [132]

Aunque ha habido muchas disputas teológicas sobre la naturaleza de Jesús durante los primeros siglos de la historia cristiana, en general, los cristianos creen que Jesús es Dios encarnado y " verdadero Dios y verdadero hombre " (o ambos, completamente divino y completamente humano). Jesús, habiéndose convertido en completamente humano , sufrió los dolores y las tentaciones de un hombre mortal, pero no pecó . Como completamente Dios, resucitó a la vida nuevamente. Según el Nuevo Testamento , resucitó de entre los muertos, [133] ascendió al cielo, está sentado a la diestra del Padre, [134] y finalmente regresará [135] para cumplir el resto de la profecía mesiánica , incluida la resurrección de los muertos , el Juicio Final y el establecimiento final del Reino de Dios .

Según los evangelios canónicos de Mateo y Lucas , Jesús fue concebido por el Espíritu Santo y nació de la Virgen María . Poco de la infancia de Jesús está registrada en los evangelios canónicos, aunque los evangelios de la infancia eran populares en la antigüedad. [136] En comparación, su edad adulta, especialmente la semana antes de su muerte, está bien documentada en los evangelios contenidos en el Nuevo Testamento , porque se cree que esa parte de su vida es la más importante. Los relatos bíblicos del ministerio de Jesús incluyen: su bautismo , milagros , predicación, enseñanza y hechos.

Los cristianos consideran que la resurrección de Jesús es la piedra angular de su fe (ver 1 Corintios 15 ) y el evento más importante de la historia. [137] Entre las creencias cristianas, la muerte y la resurrección de Jesús son dos eventos centrales en los que se basa gran parte de la doctrina y la teología cristianas. [138] Según el Nuevo Testamento, Jesús fue crucificado , murió una muerte física, fue enterrado dentro de una tumba y resucitó de entre los muertos tres días después. [139]

El Nuevo Testamento menciona varias apariciones de Jesús posteriores a su resurrección en diferentes ocasiones a sus doce apóstoles y discípulos , incluyendo "más de quinientos hermanos a la vez", [140] antes de la ascensión de Jesús al cielo. La muerte y resurrección de Jesús son conmemoradas por los cristianos en todos los servicios de adoración, con especial énfasis durante la Semana Santa , que incluye el Viernes Santo y el Domingo de Pascua .

La muerte y resurrección de Jesús suelen considerarse los acontecimientos más importantes de la teología cristiana , en parte porque demuestran que Jesús tiene poder sobre la vida y la muerte y, por tanto, tiene la autoridad y el poder de dar a las personas la vida eterna . [141]

Las iglesias cristianas aceptan y enseñan el relato del Nuevo Testamento sobre la resurrección de Jesús con muy pocas excepciones. [142] Algunos eruditos modernos utilizan la creencia de los seguidores de Jesús en la resurrección como punto de partida para establecer la continuidad del Jesús histórico y la proclamación de la iglesia primitiva . [143] Algunos cristianos liberales no aceptan una resurrección corporal literal, [144] [145] viendo la historia como un mito ricamente simbólico y espiritualmente nutritivo . Las discusiones sobre las afirmaciones de muerte y resurrección ocurren en muchos debates religiosos y diálogos interreligiosos . [146] El apóstol Pablo , un cristiano primitivo convertido y misionero, escribió: "Si Cristo no resucitó, entonces toda nuestra predicación es vana, y vuestra confianza en Dios es vana". [147] [148]

"Porque de tal manera amó Dios al mundo, que ha dado a su Hijo unigénito, para que todo aquel que en él cree, no se pierda, mas tenga vida eterna".

— Juan 3:16, NVI [149]

_-_The_Law_and_the_Gospel.jpg/440px-Lucas_Cranach_(I)_-_The_Law_and_the_Gospel.jpg)

El apóstol Pablo , como los judíos y los paganos romanos de su tiempo, creía que el sacrificio puede traer nuevos lazos de parentesco, pureza y vida eterna. [150] Para Pablo, el sacrificio necesario era la muerte de Jesús: los gentiles que son «de Cristo» son, como Israel, descendientes de Abraham y «herederos según la promesa» [151] [152] El Dios que resucitó a Jesús de entre los muertos también daría nueva vida a los «cuerpos mortales» de los cristianos gentiles, que se habían convertido con Israel en «hijos de Dios», y por tanto ya no estaban «en la carne». [153] [150]

Las iglesias cristianas modernas tienden a preocuparse mucho más por cómo la humanidad puede ser salvada de una condición universal de pecado y muerte que por la cuestión de cómo tanto los judíos como los gentiles pueden estar en la familia de Dios. Según la teología ortodoxa oriental , basada en su comprensión de la expiación según lo propuesto por la teoría de la recapitulación de Ireneo , la muerte de Jesús es un rescate . Esto restaura la relación con Dios, que es amoroso y se acerca a la humanidad, y ofrece la posibilidad de la teosis cq divinización , convirtiéndose en el tipo de humanos que Dios quiere que la humanidad sea. Según la doctrina católica, la muerte de Jesús satisface la ira de Dios, despertada por la ofensa al honor de Dios causada por la pecaminosidad humana. La Iglesia Católica enseña que la salvación no ocurre sin la fidelidad por parte de los cristianos; los conversos deben vivir de acuerdo con los principios del amor y ordinariamente deben ser bautizados. [154] En la teología protestante, la muerte de Jesús es considerada como una pena sustitutiva que Él cargó por la deuda que la humanidad debía pagar cuando quebrantó la ley moral de Dios. [155]

Los cristianos difieren en sus puntos de vista sobre hasta qué punto la salvación de los individuos está predestinada por Dios. La teología reformada pone un énfasis distintivo en la gracia al enseñar que los individuos son completamente incapaces de auto-redención , pero que la gracia santificante es irresistible . [156] En contraste, los católicos , los cristianos ortodoxos y los protestantes arminianos creen que el ejercicio del libre albedrío es necesario para tener fe en Jesús. [157]

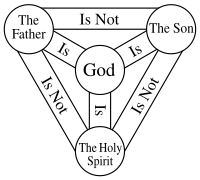

La Trinidad se refiere a la enseñanza de que el único Dios [159] comprende tres personas distintas, eternamente coexistentes: el Padre , el Hijo (encarnado en Jesucristo) y el Espíritu Santo . Juntas, a estas tres personas a veces se las llama la Deidad [160] [ 161] [162], aunque no hay un término único en uso en las Escrituras para denotar la Deidad unificada. [163] En palabras del Credo de Atanasio , una declaración temprana de la creencia cristiana, "el Padre es Dios, el Hijo es Dios y el Espíritu Santo es Dios, y sin embargo no hay tres dioses sino un solo Dios". [164] Son distintos entre sí: el Padre no tiene fuente, el Hijo es engendrado por el Padre y el Espíritu procede del Padre. Aunque distintas, las tres personas no pueden dividirse entre sí en ser o en operación. Aunque algunos cristianos también creen que Dios apareció como el Padre en el Antiguo Testamento , se acepta que apareció como el Hijo en el Nuevo Testamento y que seguirá manifestándose como el Espíritu Santo en el presente. Pero aún así, Dios siguió existiendo como tres personas en cada uno de estos tiempos. [165] Sin embargo, tradicionalmente existe la creencia de que fue el Hijo quien apareció en el Antiguo Testamento porque, por ejemplo, cuando se representa a la Trinidad en el arte , el Hijo normalmente tiene la apariencia distintiva, un halo cruciforme que identifica a Cristo, y en las representaciones del Jardín del Edén , esto anticipa una Encarnación que aún está por ocurrir. En algunos sarcófagos cristianos primitivos , el Logos se distingue con una barba, "lo que le permite parecer antiguo, incluso preexistente". [166]

La Trinidad es una doctrina esencial del cristianismo convencional. Desde antes de los tiempos del Credo Niceno (325), el cristianismo defendía [167] el misterio trino -la naturaleza de Dios- como una profesión normativa de fe. Según Roger E. Olson y Christopher Hall, a través de la oración, la meditación, el estudio y la práctica, la comunidad cristiana concluyó "que Dios debe existir como unidad y como trinidad", y codificó esto en el concilio ecuménico a fines del siglo IV. [168] [169]

Según esta doctrina, Dios no está dividido en el sentido de que cada persona tiene un tercio del todo; más bien, cada persona es considerada completamente Dios (véase Perichoresis ). La distinción radica en sus relaciones, siendo el Padre ingénito; el Hijo engendrado por el Padre; y el Espíritu Santo procede del Padre y (en la teología cristiana occidental ) del Hijo . Independientemente de esta aparente diferencia, las tres "personas" son eternas y omnipotentes . Otras religiones cristianas, incluido el unitarismo universalista , los testigos de Jehová y el mormonismo , no comparten esos puntos de vista sobre la Trinidad.

La palabra griega trias [170] [nota 6] aparece por primera vez en este sentido en las obras de Teófilo de Antioquía ; su texto dice: "de la Trinidad, de Dios, y de Su Palabra, y de Su Sabiduría". [174] El término puede haber estado en uso antes de esta época; su equivalente latino, [nota 6] trinitas , [172] aparece después con una referencia explícita al Padre, al Hijo y al Espíritu Santo, en Tertuliano . [175] [176] En el siglo siguiente, la palabra era de uso general. Se encuentra en muchos pasajes de Orígenes . [177]

El trinitarismo designa a los cristianos que creen en el concepto de la Trinidad . Casi todas las denominaciones e iglesias cristianas sostienen creencias trinitarias. Aunque las palabras "Trinidad" y "Trino" no aparecen en la Biblia, a partir del siglo III los teólogos desarrollaron el término y el concepto para facilitar la comprensión de las enseñanzas del Nuevo Testamento sobre Dios como Padre, Hijo y Espíritu Santo. Desde entonces, los teólogos cristianos han sido cuidadosos en enfatizar que la Trinidad no implica que haya tres dioses (la herejía antitrinitaria del triteísmo ), ni que cada hipóstasis de la Trinidad sea un tercio de un Dios infinito (parcialismo), ni que el Hijo y el Espíritu Santo sean seres creados por el Padre y subordinados a él ( arrianismo ). Más bien, la Trinidad se define como un solo Dios en tres personas. [178]

El no trinitarismo (o antitrinitarismo ) se refiere a la teología que rechaza la doctrina de la Trinidad. Varias visiones no trinitarias, como el adopcionismo o el modalismo , existieron en el cristianismo primitivo, lo que llevó a disputas sobre la cristología . [179] El no trinitarismo reapareció en el gnosticismo de los cátaros entre los siglos XI y XIII, entre los grupos con teología unitaria en la Reforma protestante del siglo XVI, [180] en la Ilustración del siglo XVIII , entre los grupos restauracionistas que surgieron durante el Segundo Gran Despertar del siglo XIX y, más recientemente, en las iglesias pentecostales unitarias .

El fin de las cosas, ya sea el fin de una vida individual, el fin de los tiempos o el fin del mundo, en términos generales, es la escatología cristiana; el estudio del destino de los humanos tal como se revela en la Biblia. Los temas principales de la escatología cristiana son la Tribulación , la muerte y el más allá (principalmente para los grupos evangélicos ) , el Milenio y el Rapto posterior , la Segunda Venida de Jesús, la Resurrección de los Muertos , el Cielo (para las ramas litúrgicas ) , el Purgatorio y el Infierno, el Juicio Final , el fin del mundo y los Nuevos Cielos y la Nueva Tierra .

Los cristianos creen que la segunda venida de Cristo ocurrirá al final de los tiempos , después de un período de severa persecución (la Gran Tribulación). Todos los que hayan muerto serán resucitados corporalmente de entre los muertos para el Juicio Final. Jesús establecerá plenamente el Reino de Dios en cumplimiento de las profecías bíblicas . [181] [182]

La mayoría de los cristianos creen que los seres humanos experimentan un juicio divino y son recompensados con la vida eterna o con la condenación eterna . Esto incluye el juicio general en la resurrección de los muertos , así como la creencia (sostenida por los católicos, [183] [184] los ortodoxos [185] [186] y la mayoría de los protestantes) en un juicio particular para el alma individual tras la muerte física.

En la rama católica del cristianismo, aquellos que mueren en estado de gracia, es decir, sin ningún pecado mortal que los separe de Dios, pero aún están imperfectamente purificados de los efectos del pecado, experimentan una purificación a través del estado intermedio del purgatorio para alcanzar la santidad necesaria para entrar en la presencia de Dios. [187] Aquellos que han alcanzado esta meta son llamados santos (del latín sanctus , "santo"). [188]

Algunos grupos cristianos, como los Adventistas del Séptimo Día, sostienen el mortalismo , la creencia de que el alma humana no es inmortal por naturaleza y que está inconsciente durante el estado intermedio entre la muerte corporal y la resurrección. Estos cristianos también sostienen el aniquilacionismo , la creencia de que después del juicio final, los malvados dejarán de existir en lugar de sufrir un tormento eterno. Los testigos de Jehová sostienen una opinión similar. [189]

.jpg/440px-Complete-church-midnight-mass_(3135957575).jpg)

Dependiendo de la denominación específica del cristianismo , las prácticas pueden incluir el bautismo , la Eucaristía (Santa Comunión o la Cena del Señor), la oración (incluido el Padre Nuestro ), la confesión , la confirmación , los ritos funerarios , los ritos matrimoniales y la educación religiosa de los niños. La mayoría de las denominaciones tienen clérigos ordenados que dirigen servicios de culto comunitarios regulares. [191]

Los ritos, rituales y ceremonias cristianas no se celebran en una única lengua sagrada. Muchas iglesias cristianas ritualistas distinguen entre lengua sagrada, lengua litúrgica y lengua vernácula. Las tres lenguas importantes en la era cristiana primitiva eran: el latín , el griego y el siríaco . [192] [193] [194]

Los servicios de adoración generalmente siguen un patrón o forma conocida como liturgia . [nota 7] Justino Mártir describió la liturgia cristiana del siglo II en su Primera Apología ( c. 150 ) al emperador Antonino Pío , y su descripción sigue siendo relevante para la estructura básica del culto litúrgico cristiano:

Y los domingos, todos los que viven en ciudades o en el campo se reúnen en un lugar, y se leen las memorias de los apóstoles o los escritos de los profetas, hasta que el tiempo lo permita; luego, cuando el lector ha terminado, el presidente instruye verbalmente y exhorta a la imitación de estas cosas buenas. Luego todos nos levantamos juntos y oramos, y, como dijimos antes, cuando nuestra oración ha terminado, se trae pan, vino y agua, y el presidente de la misma manera ofrece oraciones y acciones de gracias, según su capacidad, y el pueblo asiente, diciendo Amén ; y hay una distribución a cada uno, y una participación de aquello por lo que se han dado gracias, y a los que están ausentes se les envía una parte por los diáconos. Y los que están bien y dispuestos, dan lo que cada uno cree conveniente; y lo que se recoge se deposita en poder del presidente, quien socorre a los huérfanos y a las viudas y a los que, por enfermedad o por cualquier otra causa, están en necesidad, y a los que están encadenados y a los extranjeros que residen entre nosotros, y en una palabra, cuida de todos los que están en necesidad. [196]

Así, como describió Justino, los cristianos se reúnen para el culto comunitario típicamente el domingo, el día de la resurrección, aunque otras prácticas litúrgicas a menudo ocurren fuera de este contexto. Las lecturas de las Escrituras se extraen del Antiguo y Nuevo Testamento, pero especialmente de los evangelios. [nota 8] [197] La instrucción se da en base a estas lecturas, en forma de sermón u homilía . Hay una variedad de oraciones congregacionales , incluyendo acción de gracias, confesión e intercesión , que ocurren a lo largo del servicio y toman una variedad de formas incluyendo recitadas, responsivas, silenciosas o cantadas. [191] Se pueden cantar salmos , himnos , canciones de adoración y otra música de la iglesia . [198] [199] Los servicios pueden variar para eventos especiales como días festivos significativos . [200]

Casi todas las formas de culto incorporan la Eucaristía, que consiste en una comida. Se recrea de acuerdo con las instrucciones de Jesús en la Última Cena de que sus seguidores hagan en memoria de él, como cuando les dio pan a sus discípulos , diciendo: "Este es mi cuerpo", y les dio vino diciendo: "Esta es mi sangre". [201] En la iglesia primitiva , los cristianos y aquellos que aún no habían completado la iniciación se separaban para la parte eucarística del servicio. [202] Algunas denominaciones, como las iglesias luteranas confesionales, continúan practicando la " comunión cerrada ". [203] Ofrecen la comunión a quienes ya están unidos en esa denominación o, a veces, en una iglesia individual. Los católicos restringen aún más la participación a sus miembros que no están en estado de pecado mortal . [204] Muchas otras iglesias, como la Comunión Anglicana y las Iglesias Metodistas (como la Iglesia Metodista Libre y la Iglesia Metodista Unida ), practican la " comunión abierta ", ya que consideran la comunión como un medio para la unidad, más que un fin, e invitan a todos los cristianos creyentes a participar. [205] [206] [207]

Y este alimento se llama entre nosotros Eukharistia [la Eucaristía], de la cual no se permite participar a nadie sino al hombre que cree que las cosas que enseñamos son verdaderas, y que ha sido lavado con el lavamiento que es para la remisión de los pecados, y para la regeneración, y que vive de tal manera como Cristo ha ordenado. Porque no recibimos estos como pan común y bebida común; sino que de la misma manera que Jesucristo nuestro Salvador, habiéndose hecho carne por la Palabra de Dios, tuvo carne y sangre para nuestra salvación, así también se nos ha enseñado que el alimento que es bendecido por la oración de Su palabra, y del cual nuestra sangre y carne por transmutación se nutren, es la carne y la sangre de ese Jesús que se hizo carne.

Justino Mártir [196]

En la creencia y la práctica cristianas, un sacramento es un rito instituido por Cristo que confiere gracia y constituye un misterio sagrado . El término deriva de la palabra latina sacramentum , que se utilizó para traducir la palabra griega para misterio . Las opiniones sobre qué ritos son sacramentales y qué significa que un acto sea un sacramento varían entre las denominaciones y tradiciones cristianas. [208]

La definición funcional más convencional de un sacramento es que es un signo externo, instituido por Cristo, que transmite una gracia espiritual interna a través de Cristo. Los dos sacramentos más ampliamente aceptados son el Bautismo y la Eucaristía; sin embargo, la mayoría de los cristianos también reconocen cinco sacramentos adicionales: la Confirmación ( Crismación en la tradición oriental), el Orden Sagrado (u ordenación ), la Penitencia (o Confesión ), la Unción de los Enfermos y el Matrimonio (ver Puntos de vista cristianos sobre el matrimonio ). [208]

En conjunto, estos son los Siete Sacramentos reconocidos por las iglesias de la tradición de la Alta Iglesia , en particular la católica , la ortodoxa oriental , la ortodoxa oriental , la católica independiente , la antigua católica , algunos luteranos y los anglicanos . La mayoría de las demás denominaciones y tradiciones normalmente afirman solo el bautismo y la eucaristía como sacramentos, mientras que algunos grupos protestantes, como los cuáqueros, rechazan la teología sacramental. [208] Ciertas denominaciones del cristianismo, como los anabaptistas, utilizan el término " ordenanzas " para referirse a los ritos instituidos por Jesús para que los cristianos los observen. [209] Se han enseñado siete ordenanzas en muchas iglesias anabaptistas menonitas conservadoras , que incluyen "el bautismo, la comunión, el lavatorio de pies, el matrimonio, la unción con aceite, el beso santo y la oración de santificación". [190]

Además de esto, la Iglesia del Este tiene dos sacramentos adicionales en lugar de los sacramentos tradicionales del Matrimonio y la Unción de los Enfermos. Estos incluyen la Santa Levadura (Melka) y la señal de la cruz . [210] Las iglesias anabaptistas de los Hermanos de Schwarzenau , como la Iglesia de los Hermanos de Dunkard , observan la fiesta del ágape (fiesta del amor), un rito que también observan la Iglesia Morava y las Iglesias Metodistas . [211]

Los católicos, los cristianos orientales, los luteranos, los anglicanos y otras comunidades protestantes tradicionales enmarcan el culto en torno al año litúrgico . [212] El ciclo litúrgico divide el año en una serie de estaciones , cada una con sus énfasis teológicos y modos de oración, que pueden significarse por diferentes formas de decorar las iglesias, colores de los paramentos y vestimentas del clero, [213] lecturas de las Escrituras, temas para la predicación e incluso diferentes tradiciones y prácticas que a menudo se observan personalmente o en el hogar.

Los calendarios litúrgicos cristianos occidentales se basan en el ciclo del Rito Romano de la Iglesia Católica, [213] y los cristianos orientales utilizan calendarios análogos basados en el ciclo de sus respectivos ritos . Los calendarios reservan días festivos, como solemnidades que conmemoran un evento en la vida de Jesús, María o los santos , y períodos de ayuno , como la Cuaresma y otros eventos piadosos como la memoria , o festivales menores que conmemoran a los santos. Los grupos cristianos que no siguen una tradición litúrgica a menudo conservan ciertas celebraciones, como Navidad , Pascua y Pentecostés : estas son las celebraciones del nacimiento de Cristo, la resurrección y el descenso del Espíritu Santo sobre la Iglesia, respectivamente. Unas pocas denominaciones como los cristianos cuáqueros no hacen uso de un calendario litúrgico. [214]

La mayoría de las denominaciones cristianas no han practicado en general el aniconismo , [215] la evitación o prohibición de imágenes devocionales, aunque los primeros cristianos judíos , invocando la prohibición de la idolatría del Decálogo , evitaron las figuras en sus símbolos. [216]

La cruz , hoy uno de los símbolos más ampliamente reconocidos, fue utilizada por los cristianos desde los tiempos más remotos. [217] [218] Tertuliano, en su libro De Corona , cuenta cómo ya era una tradición para los cristianos trazar la señal de la cruz en sus frentes. [219] Aunque la cruz era conocida por los primeros cristianos, el crucifijo no apareció en uso hasta el siglo V. [220]

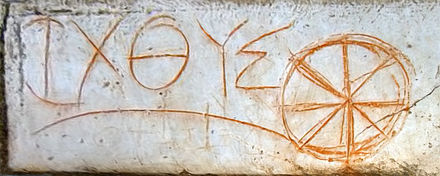

Entre los primeros símbolos cristianos, el del pez o Ichthys parece haber ocupado el primer lugar en importancia, como se ve en fuentes monumentales como tumbas de las primeras décadas del siglo II. [221] Su popularidad aparentemente surgió de la palabra griega ichthys (pez) que forma un acróstico para la frase griega Iesous Christos Theou Yios Soter (Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ), [nota 9] (Jesucristo, Hijo de Dios, Salvador), un resumen conciso de la fe cristiana. [221]

Otros símbolos cristianos importantes son el monograma del cristóbal Colón , la paloma y la rama de olivo (que representan al Espíritu Santo), el cordero sacrificial (que representa el sacrificio de Cristo), la vid (que simboliza la conexión del cristiano con Cristo) y muchos otros. Todos ellos derivan de pasajes del Nuevo Testamento. [220]

Algunas fuentes indican que los cristianos incluso utilizaban una rueda de ocho radios para simbolizar las cinco letras griegas colocadas una sobre otra, algo que se remonta a la época del Imperio Romano .

El bautismo es el acto ritual, con el uso del agua, por el cual una persona es admitida como miembro de la Iglesia . Las creencias sobre el bautismo varían entre las denominaciones. Las diferencias ocurren en primer lugar sobre si el acto tiene algún significado espiritual. Algunas, como las iglesias católica y ortodoxa oriental , así como luteranas y anglicanas, sostienen la doctrina de la regeneración bautismal , que afirma que el bautismo crea o fortalece la fe de una persona y está íntimamente vinculado a la salvación. Los bautistas y los hermanos de Plymouth ven el bautismo como un acto puramente simbólico, una declaración pública externa del cambio interno que ha tenido lugar en la persona, pero no como espiritualmente eficaz. En segundo lugar, hay diferencias de opinión sobre la metodología (o modo) del acto. Estos modos son: por inmersión ; si la inmersión es total, por sumersión ; por afusión (derramamiento); y por aspersión (rociamiento). Aquellos que sostienen el primer punto de vista también pueden adherirse a la tradición del bautismo infantil ; [222] [223] [224] [225] Todas las Iglesias ortodoxas practican el bautismo infantil y siempre bautizan por inmersión total repetida tres veces en el nombre del Padre, del Hijo y del Espíritu Santo. [226] [227] La Iglesia luterana y la Iglesia católica también practican el bautismo infantil, [228] [229] [230] generalmente por afusión, y utilizando la fórmula trinitaria . [231] Los cristianos anabaptistas practican el bautismo de creyentes , en el que un adulto elige recibir la ordenanza después de tomar la decisión de seguir a Jesús. [232] Las denominaciones anabaptistas como los menonitas , los amish y los huteritas utilizan el vertido como modo de administrar el bautismo de los creyentes, mientras que los anabaptistas de las tradiciones de los Hermanos Schwarzenau y los Hermanos del Río bautizan por inmersión . [233] [234] [235] [236]

"... 'Padre nuestro que estás en el cielo, santificado sea tu nombre. Venga tu reino. Hágase tu voluntad en la tierra como en el cielo. El pan nuestro de cada día, dánoslo hoy. Perdónanos nuestras deudas, como también nosotros perdonamos a nuestros deudores. No nos dejes caer en la tentación, mas líbranos del mal'".

— El Padre Nuestro , Mateo 6:9–13, NVI [237]

En el Evangelio de San Mateo , Jesús enseñó el Padre Nuestro , que ha sido considerado como un modelo para la oración cristiana. [238] El mandato para que los cristianos recen el Padre Nuestro tres veces al día fue dado en la Didaché y llegó a ser recitado por los cristianos a las 9 am, a las 12 pm y a las 3 pm. [239] [240]

En la Tradición Apostólica del siglo II , Hipólito instruyó a los cristianos a orar en siete momentos fijos de oración : "al levantarse, al encenderse la lámpara de la tarde, al acostarse, a medianoche" y "la tercera, sexta y novena hora del día, siendo horas asociadas con la Pasión de Cristo". [241] Las posiciones de oración, incluyendo arrodillarse, estar de pie y postraciones, se han utilizado para estos siete momentos fijos de oración desde los días de la Iglesia primitiva. [242] Los cristianos ortodoxos orientales utilizan breviarios como el Shehimo y el Agpeya para rezar estas horas canónicas mientras miran en la dirección de oración hacia el este . [243] [244]

La Tradición Apostólica ordenó que los cristianos usaran la señal de la cruz durante el exorcismo menor del bautismo , durante las abluciones antes de orar en horarios fijos de oración y en tiempos de tentación. [245]

La oración de intercesión es la oración que se ofrece en beneficio de otras personas. Hay muchas oraciones de intercesión registradas en la Biblia, incluidas las oraciones del apóstol Pedro en favor de personas enfermas [246] y las de los profetas del Antiguo Testamento en favor de otras personas [247] . En la Epístola de Santiago no se hace distinción entre la oración de intercesión ofrecida por los creyentes comunes y la del destacado profeta del Antiguo Testamento Elías [248] . La eficacia de la oración en el cristianismo se deriva del poder de Dios más que del estatus de quien ora [249] .

La iglesia antigua, tanto en el cristianismo oriental como en el occidental , desarrolló una tradición de pedir la intercesión de los santos (fallecidos) , y esta sigue siendo la práctica de la mayoría de las iglesias ortodoxas orientales , católicas y algunas luteranas y anglicanas . [250] Sin embargo, aparte de ciertos sectores dentro de las dos últimas denominaciones, otras iglesias de la Reforma protestante rechazaron la oración a los santos, en gran medida sobre la base de la única mediación de Cristo. [251] El reformador Huldrych Zwingli admitió que había ofrecido oraciones a los santos hasta que su lectura de la Biblia lo convenció de que esto era idólatra . [252]

Según el Catecismo de la Iglesia Católica : "La oración es la elevación de la mente y el corazón a Dios o la petición de bienes a Dios". [253] El Libro de Oración Común en la tradición anglicana es una guía que proporciona un orden establecido para los servicios, que contiene oraciones establecidas, lecturas de las Escrituras e himnos o salmos cantados. [254] Con frecuencia en el cristianismo occidental, al orar, las manos se colocan con las palmas juntas y hacia adelante como en la ceremonia de encomio feudal . En otras ocasiones se puede utilizar la antigua postura orans , con las palmas hacia arriba y los codos hacia adentro.

El cristianismo, al igual que otras religiones, tiene adeptos cuyas creencias e interpretaciones bíblicas varían. El cristianismo considera el canon bíblico , el Antiguo Testamento y el Nuevo Testamento , como la palabra inspirada de Dios. La visión tradicional de la inspiración es que Dios obró a través de autores humanos para que lo que ellos produjeron fuera lo que Dios deseaba comunicar. La palabra griega que se refiere a la inspiración en 2 Timoteo 3:16 es theopneustos , que literalmente significa "inspirada por Dios". [255]

Algunos creen que la inspiración divina hace que las Biblias actuales sean inerrantes . Otros afirman que la Biblia es inerrante en sus manuscritos originales, aunque ninguno de ellos se conserva. Y otros sostienen que solo una traducción en particular es inerrante, como la versión King James . [256] [257] [258] Otra visión estrechamente relacionada es la infalibilidad bíblica o inerrancia limitada, que afirma que la Biblia está libre de errores como guía para la salvación, pero puede incluir errores en cuestiones como la historia, la geografía o la ciencia.

El canon del Antiguo Testamento aceptado por las iglesias protestantes, que es solo el Tanaj (el canon de la Biblia hebrea ), es más corto que el aceptado por las iglesias ortodoxa y católica, que también incluyen los libros deuterocanónicos que aparecen en la Septuaginta , siendo el canon ortodoxo ligeramente más grande que el católico; [259] Los protestantes consideran a estos últimos como apócrifos , documentos históricos importantes que ayudan a informar la comprensión de las palabras, la gramática y la sintaxis utilizadas en el período histórico de su concepción. Algunas versiones de la Biblia incluyen una sección apócrifa separada entre el Antiguo Testamento y el Nuevo Testamento. [260] El Nuevo Testamento, escrito originalmente en griego koiné , contiene 27 libros en los que están de acuerdo todas las iglesias principales.

Algunas denominaciones tienen escrituras sagradas canónicas adicionales además de la Biblia, incluidas las obras canónicas del movimiento de los Santos de los Últimos Días y el Principio Divino en la Iglesia de la Unificación . [261]

En la antigüedad, se desarrollaron dos escuelas de exégesis en Alejandría y Antioquía . La interpretación alejandrina, ejemplificada por Orígenes , tendía a leer las Escrituras alegóricamente , mientras que la interpretación antioquena se adhería al sentido literal, sosteniendo que otros significados (llamados theoria ) solo podían aceptarse si se basaban en el significado literal. [262]

La teología católica distingue dos sentidos de la Escritura: el literal y el espiritual. [263]

El sentido literal de la comprensión de las Escrituras es el significado que transmiten las palabras de las Escrituras. El sentido espiritual se subdivide a su vez en:

En cuanto a la exégesis , siguiendo las reglas de la sana interpretación, la teología católica sostiene:

Muchos cristianos protestantes, como los luteranos [270] y los reformados, creen en la doctrina de la sola scriptura —que sostiene que la Biblia es una revelación autosuficiente, la autoridad final sobre toda la doctrina cristiana y que reveló toda la verdad necesaria para la salvación; [271] [272] otros cristianos protestantes, como los metodistas y los anglicanos, afirman la doctrina de la prima scriptura, que enseña que la Escritura es la fuente primaria de la doctrina cristiana, pero que "la tradición, la experiencia y la razón" pueden nutrir la religión cristiana siempre que estén en armonía con la Biblia. [271] [273] Los protestantes creen característicamente que los creyentes comunes pueden alcanzar una comprensión adecuada de la Escritura porque la Escritura misma es clara en su significado (o "perspicaz"). Martín Lutero creía que sin la ayuda de Dios, la Escritura estaría "envuelta en oscuridad". [274] Abogó por "una comprensión definida y simple de la Escritura". [274] Juan Calvino escribió: «Todos los que se niegan a seguir al Espíritu Santo como su guía, encuentran en la Escritura una luz clara». [275] Relacionado con esto está la «eficacia», que la Escritura es capaz de conducir a la gente a la fe; y la «suficiencia», que las Escrituras contienen todo lo que uno necesita saber para obtener la salvación y vivir una vida cristiana. [276]

Los protestantes enfatizan el significado que transmiten las palabras de la Escritura, el método histórico-gramatical . [277] El método histórico-gramatical o método gramatical-histórico es un esfuerzo en la hermenéutica bíblica para encontrar el significado original pretendido en el texto. [278] Este significado original pretendido del texto se extrae mediante el examen del pasaje a la luz de los aspectos gramaticales y sintácticos, el trasfondo histórico, el género literario, así como consideraciones teológicas (canónicas). [279] El método histórico-gramatical distingue entre el significado original y el significado del texto. El significado del texto incluye el uso o aplicación resultante del texto. El pasaje original se considera que tiene un solo significado o sentido. Como dijo Milton S. Terry : "Un principio fundamental en la exposición gramatical-histórica es que las palabras y oraciones pueden tener un solo significado en una y la misma conexión. En el momento en que descuidamos este principio, nos dejamos llevar por un mar de incertidumbre y conjeturas". [280] Técnicamente hablando, el método histórico-gramatical de interpretación es distinto de la determinación del significado del pasaje a la luz de esa interpretación. En conjunto, ambos definen el término hermenéutica (bíblica). [278] Algunos intérpretes protestantes hacen uso de la tipología . [281]

Con alrededor de 2.400 millones de seguidores según una estimación de 2020 del Pew Research Center , [282] [283] [11] [284] [285] [286] [287] dividido en tres ramas principales: católica, protestante y ortodoxa oriental, el cristianismo es la religión más grande del mundo . [288] Las altas tasas de natalidad y conversiones en el Sur global se citaron como las razones del crecimiento de la población cristiana. [289] [290] Durante los últimos cien años, la proporción cristiana se ha situado en torno al 33% de la población mundial. Esto enmascara un cambio importante en la demografía del cristianismo; los grandes aumentos en el mundo en desarrollo han ido acompañados de descensos sustanciales en el mundo desarrollado, principalmente en Europa occidental y América del Norte. [291] Según un estudio del Pew Research Center de 2015 , en las próximas cuatro décadas, el cristianismo seguirá siendo la religión más grande; y para 2050, se espera que la población cristiana supere los 3.000 millones. [292] : 60

.jpg/440px-Reabertura_Museu_de_Arte_Sacra_(18626301050).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Auto_de_Páscoa_-_IgrejaDaCidade_(crop).jpg)

Según algunos estudiosos, el cristianismo ocupa el primer lugar en ganancias netas a través de la conversión religiosa . [294] [295] Como porcentaje de cristianos, la Iglesia Católica y la Ortodoxia (tanto oriental como oriental ) están decayendo en algunas partes del mundo (aunque el catolicismo está creciendo en Asia, en África, vibrante en Europa del Este, etc.), mientras que los protestantes y otros cristianos están en aumento en el mundo en desarrollo. [296] [297] [298] El llamado protestantismo popular [nota 10] es una de las categorías religiosas de más rápido crecimiento en el mundo. [299] [300] [301] Sin embargo, el catolicismo también seguirá creciendo hasta alcanzar los 1.630 millones en 2050, según Todd Johnson del Centro para el Estudio del Cristianismo Global. [302] Solo África, en 2015, albergará a 230 millones de católicos africanos. [303] Y si en 2018 la ONU proyecta que la población de África llegará a 4.500 millones en 2100 (no 2.000 millones como se predijo en 2004), el catolicismo crecerá, al igual que otros grupos religiosos. [304] Según el Pew Research Center, se espera que África albergue a 1.100 millones de cristianos africanos en 2050. [292]

En 2010, el 87% de la población cristiana mundial vivía en países donde los cristianos son mayoría, mientras que el 13% de la población cristiana mundial vivía en países donde los cristianos son minoría. [1] El cristianismo es la religión predominante en Europa, América, Oceanía y África subsahariana. [1] También hay grandes comunidades cristianas en otras partes del mundo, como Asia Central , Oriente Medio y el norte de África , Asia Oriental , el Sudeste Asiático y el subcontinente indio . [1] En Asia, es la religión dominante en Armenia, Chipre, Georgia, Timor Oriental y Filipinas. [305] Sin embargo, está disminuyendo en algunas áreas, incluyendo el norte y el oeste de los Estados Unidos, [306] algunas áreas de Oceanía (Australia [307] y Nueva Zelanda [308] ), el norte de Europa (incluyendo Gran Bretaña, [309] Escandinavia y otros lugares), Francia, Alemania, Canadá, [310] y algunas partes de Asia (especialmente el Medio Oriente, debido a la emigración cristiana , [311] [312] [313] y Macao [314] ).

La población cristiana total no está disminuyendo en Brasil y el sur de los Estados Unidos, [315] sin embargo, el porcentaje de la población que se identifica como cristiana está en declive. Desde la caída del comunismo, la proporción de cristianos se ha mantenido en gran medida estable en Europa Central , excepto en la República Checa . [316] Por otro lado, el cristianismo está creciendo rápidamente tanto en números como en porcentajes en Europa del Este, [316] [293] China, [317] [288] otros países asiáticos , [288] [318] África subsahariana , [288] [319] América Latina , [288] África del Norte ( Magreb ), [320] [319] países del Consejo de Cooperación del Golfo , [288] y Oceanía. [319]

Despite a decline in adherence in the West, Christianity remains the dominant religion in the region, with about 70% of that population identifying as Christian.[1][321] Christianity remains the largest religion in Western Europe, where 71% of Western Europeans identified themselves as Christian in 2018.[322] A 2011 Pew Research Center survey found that 76% of Europeans, 73% in Oceania and about 86% in the Americas (90% in Latin America and 77% in North America) identified themselves as Christians.[288][1] By 2010 about 157 countries and territories in the world had Christian majorities.[288]

There are many charismatic movements that have become well established over large parts of the world, especially Africa, Latin America, and Asia.[323][324][325][326][327][1] Since 1900, primarily due to conversion, Protestantism has spread rapidly in Africa, Asia, Oceania, and Latin America.[328] From 1960 to 2000, the global growth of the number of reported Evangelical Protestants grew three times the world's population rate, and twice that of Islam.[329] According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey from the University of Melbourne, since the 1960s there has been a substantial increase in the number of conversions from Islam to Christianity, mostly to the Evangelical and Pentecostal forms.[330]A study conducted by St. Mary's University estimated about 10.2 million Muslim converts to Christianity in 2015;[320][331] according to the study significant numbers of Muslim converts to Christianity can be found in Afghanistan,[320][332] Azerbaijan,[320][332] Central Asia (including Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and other countries),[320][332] Indonesia,[320][332] Malaysia,[320][332] the Middle East (including Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey,[333] and other countries),[320][332] North Africa (including Algeria, Morocco,[334][335] and Tunisia[336]),[320][332] Sub-Saharan Africa,[320][332] and the Western World (including Albania, Belgium, France, Germany, Kosovo, the Netherlands, Russia, Scandinavia, United Kingdom, the United States, and other western countries).[320][332] It is also reported that Christianity is popular among people of different backgrounds in Africa and Asia; according to a report by the Singapore Management University, more people in Southeast Asia are converting to Christianity, many of them young and having a university degree.[318] According to scholar Juliette Koning and Heidi Dahles of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam there is a "rapid expansion" of Christianity in Singapore, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Indonesia, Malaysia, and South Korea.[318] According to scholar Terence Chong from the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, since the 1980s Christianity is expanding in China, Singapore,[337] Indonesia, Japan,[338][339] Malaysia, Taiwan, South Korea,[1] and Vietnam.[340]

In most countries in the developed world, church attendance among people who continue to identify themselves as Christians has been falling over the last few decades.[341] Some sources view this as part of a drift away from traditional membership institutions,[342] while others link it to signs of a decline in belief in the importance of religion in general.[343] Europe's Christian population, though in decline, still constitutes the largest geographical component of the religion.[344] According to data from the 2012 European Social Survey, around a third of European Christians say they attend services once a month or more.[345] Conversely, according to the World Values Survey, about more than two-thirds of Latin American Christians, and about 90% of African Christians (in Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa and Zimbabwe) said they attended church regularly.[345] According to a 2018 study by the Pew Research Center, Christians in Africa and Latin America and the United States have high levels of commitment to their faith.[346]

Christianity, in one form or another, is the sole state religion of the following nations: Argentina (Catholic),[347] Costa Rica (Catholic),[348] the Kingdom of Denmark (Lutheran),[349] England (Anglican),[350] Greece (Greek Orthodox),[351] Iceland (Lutheran),[352] Liechtenstein (Catholic),[353] Malta (Catholic),[354] Monaco (Catholic),[355] Norway (Lutheran),[356] Samoa,[357] Tonga (Methodist), Tuvalu (Reformed), and Vatican City (Catholic).[358]

There are numerous other countries, such as Cyprus, which although do not have an established church, still give official recognition and support to a specific Christian denomination.[359]

World Christianity by tradition in 2024 as per World Christian Database[361]

Christianity can be taxonomically divided into six main groups: Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Oriental Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodoxy, the Church of the East, and Restorationism.[362][363] A broader distinction that is sometimes drawn is between Eastern Christianity and Western Christianity, which has its origins in the East–West Schism (Great Schism) of the 11th century. Recently, neither Western nor Eastern World Christianity has also stood out, for example, in African-initiated churches. However, there are other present[364] and historical[365] Christian groups that do not fit neatly into one of these primary categories.

There is a diversity of doctrines and liturgical practices among groups calling themselves Christian. These groups may vary ecclesiologically in their views on a classification of Christian denominations.[366] The Nicene Creed (325), however, is typically accepted as authoritative by most Christians, including the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and major Protestant, such as Lutheran and Anglican denominations.[367]

The Catholic Church consists of those particular Churches, headed by bishops, in communion with the pope, the bishop of Rome, as its highest authority in matters of faith, morality, and church governance.[368][369] Like Eastern Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church, through apostolic succession, traces its origins to the Christian community founded by Jesus Christ.[370][371] Catholics maintain that the "one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church" founded by Jesus subsists fully in the Catholic Church, but also acknowledges other Christian churches and communities[372][373] and works towards reconciliation among all Christians.[372] The Catholic faith is detailed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.[374][375]

Of its seven sacraments, the Eucharist is the principal one, celebrated liturgically in the Mass.[376] The church teaches that through consecration by a priest, the sacrificial bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ. The Virgin Mary is venerated in the Catholic Church as Mother of God and Queen of Heaven, honoured in dogmas and devotions.[377] Its teaching includes Divine Mercy, sanctification through faith and evangelization of the Gospel as well as Catholic social teaching, which emphasizes voluntary support for the sick, the poor, and the afflicted through the corporal and spiritual works of mercy. The Catholic Church operates thousands of Catholic schools, universities, hospitals, and orphanages around the world, and is the largest non-government provider of education and health care in the world.[378] Among its other social services are numerous charitable and humanitarian organizations.

Canon law (Latin: jus canonicum)[379] is the system of laws and legal principles made and enforced by the hierarchical authorities of the Catholic Church to regulate its external organisation and government and to order and direct the activities of Catholics toward the mission of the church.[380] The canon law of the Latin Church was the first modern Western legal system,[381] and is the oldest continuously functioning legal system in the West.[382][383] while the distinctive traditions of Eastern Catholic canon law govern the 23 Eastern Catholic particular churches sui iuris.

As the world's oldest and largest continuously functioning international institution,[384] it has played a prominent role in the history and development of Western civilization.[385] The 2,834 sees[386] are grouped into 24 particular autonomous Churches (the largest of which being the Latin Church), each with its own distinct traditions regarding the liturgy and the administering of sacraments.[387] With more than 1.1 billion baptized members, the Catholic Church is the largest Christian church and represents 50.1%[1] of all Christians as well as 16.7% of the world's population.[388][389][390] Catholics live all over the world through missions, diaspora, and conversions.

.jpg/440px-Church_of_St._George,_Istanbul_(August_2010).jpg)

The Eastern Orthodox Church consists of those churches in communion with the patriarchal sees of the East, such as the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.[392] Like the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church also traces its heritage to the foundation of Christianity through apostolic succession and has an episcopal structure, though the autonomy of its component parts is emphasized, and most of them are national churches.

Eastern Orthodox theology is based on holy tradition which incorporates the dogmatic decrees of the seven Ecumenical Councils, the Scriptures, and the teaching of the Church Fathers. The church teaches that it is the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church established by Jesus Christ in his Great Commission,[393] and that its bishops are the successors of Christ's apostles.[394] It maintains that it practises the original Christian faith, as passed down by holy tradition. Its patriarchates, reminiscent of the pentarchy, and other autocephalous and autonomous churches reflect a variety of hierarchical organisation. It recognizes seven major sacraments, of which the Eucharist is the principal one, celebrated liturgically in synaxis. The church teaches that through consecration invoked by a priest, the sacrificial bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ. The Virgin Mary is venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church as the Theotokos, meaning God-bearer, and is honoured in devotions.

Eastern Orthodoxy is the second largest single denomination in Christianity, with an estimated 230 million adherents, although Protestants collectively outnumber them, substantially.[1][395] As one of the oldest surviving religious institutions in the world, the Eastern Orthodox Church has played a prominent role in the history and culture of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, the Caucasus, and the Near East.[396] The majority of Eastern Orthodox Christians live mainly in Southeast and Eastern Europe, Cyprus, Georgia, and parts of the Caucasus region, Siberia, and the Russian Far East. Over half of Eastern Orthodox Christians follow the Russian Orthodox Church, while the vast majority live within Russia.[397] There are also communities in the former Byzantine regions of Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean, and in the Middle East. Eastern Orthodox communities are also present in many other parts of the world, particularly North America, Western Europe, and Australia, formed through diaspora, conversions, and missionary activity.[398]

The Oriental Orthodox Churches (also called "Old Oriental" churches) are those eastern churches that recognize the first three ecumenical councils—Nicaea, Constantinople, and Ephesus—but reject the dogmatic definitions of the Council of Chalcedon and instead espouse a Miaphysite christology.

The Oriental Orthodox communion consists of six groups: Syriac Orthodox, Coptic Orthodox, Ethiopian Orthodox, Eritrean Orthodox, Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (India), and Armenian Apostolic churches.[399] These six churches, while being in communion with each other, are completely independent hierarchically.[400] These churches are generally not in communion with the Eastern Orthodox Church, with whom they are in dialogue for erecting a communion.[401] Together, they have about 62 million members worldwide.[402][403][404][405][395]

As some of the oldest religious institutions in the world, the Oriental Orthodox Churches have played a prominent role in the history and culture of Armenia, Egypt, Turkey, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan, Iran, Azerbaijan and parts of the Middle East and India.[406][407][408] An Eastern Christian body of autocephalous churches, its bishops are equal by virtue of episcopal ordination, and its doctrines can be summarized in that the churches recognize the validity of only the first three ecumenical councils.[409]