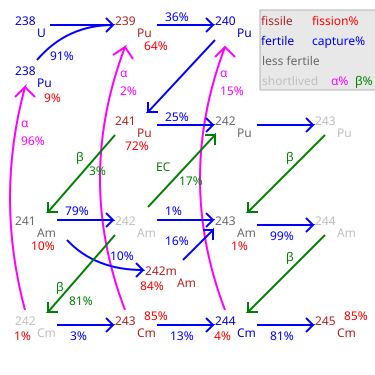

A breeder reactor is a nuclear reactor that generates more fissile material than it consumes.[1] These reactors can be fueled with more-commonly available isotopes of uranium and thorium, such as uranium-238 and thorium-232, as opposed to the rare uranium-235 which is used in conventional reactors. These materials are called fertile materials since they can be bred into fuel by these breeder reactors.

Breeder reactors achieve this because their neutron economy is high enough to create more fissile fuel than they use. These extra neutrons are absorbed by the fertile material that is loaded into the reactor along with fissile fuel. This irradiated fertile material in turn transmutes into fissile material which can undergo fission reactions.

Breeders were at first found attractive because they made more complete use of uranium fuel than light-water reactors, but interest declined after the 1960s as more uranium reserves were found[2] and new methods of uranium enrichment reduced fuel costs.

Many types of breeder reactor are possible:

A "breeder" is simply a nuclear reactor designed for very high neutron economy with an associated conversion rate higher than 1.0. In principle, almost any reactor design could be tweaked to become a breeder. For example, the light-water reactor, a heavily moderated thermal design, evolved into the fast reactor[3] concept, using light water in a low-density supercritical form to increase the neutron economy enough to allow breeding.

Aside from water-cooled, there are many other types of breeder reactor currently envisioned as possible. These include molten-salt cooled, gas cooled, and liquid-metal cooled designs in many variations. Almost any of these basic design types may be fueled by uranium, plutonium, many minor actinides, or thorium, and they may be designed for many different goals, such as creating more fissile fuel, long-term steady-state operation, or active burning of nuclear wastes.

Extant reactor designs are sometimes divided into two broad categories based upon their neutron spectrum, which generally separates those designed to use primarily uranium and transuranics from those designed to use thorium and avoid transuranics. These designs are:

All current large-scale FBR power stations were liquid metal fast breeder reactors (LMFBR) cooled by liquid sodium. These have been of one of two designs:[1]: 43

There are only two commercially operating breeder reactors as of 2017[update]: the BN-600 reactor, at 560 MWe, and the BN-800 reactor, at 880 MWe. Both are Russian sodium-cooled reactors. The designs use liquid metal as the primary coolant, to transfer heat from the core to steam used to power the electricity generating turbines. FBRs have been built cooled by liquid metals other than sodium—some early FBRs used mercury; other experimental reactors have used a sodium-potassium alloy. Both have the advantage that they are liquids at room temperature, which is convenient for experimental rigs but less important for pilot or full-scale power stations.

Three of the proposed generation IV reactor types are FBRs:[4]

FBRs usually use a mixed oxide fuel core of up to 20% plutonium dioxide (PuO2) and at least 80% uranium dioxide (UO2). Another fuel option is metal alloys, typically a blend of uranium, plutonium, and zirconium (used because it is "transparent" to neutrons). Enriched uranium can be used on its own.

Many designs surround the reactor core in a blanket of tubes that contain non-fissile uranium-238, which, by capturing fast neutrons from the reaction in the core, converts to fissile plutonium-239 (as is some of the uranium in the core), which is then reprocessed and used as nuclear fuel. Other FBR designs rely on the geometry of the fuel (which also contains uranium-238), arranged to attain sufficient fast neutron capture. The plutonium-239 (or the fissile uranium-235) fissile cross-section is much smaller in a fast spectrum than in a thermal spectrum, as is the ratio between the 239Pu/235U fission cross-section and the 238U absorption cross-section. This increases the concentration of 239Pu/235U needed to sustain a chain reaction, as well as the ratio of breeding to fission.[5]On the other hand, a fast reactor needs no moderator to slow down the neutrons at all, taking advantage of the fast neutrons producing a greater number of neutrons per fission than slow neutrons. For this reason ordinary liquid water, being a moderator and neutron absorber, is an undesirable primary coolant for fast reactors. Because large amounts of water in the core are required to cool the reactor, the yield of neutrons and therefore breeding of 239Pu are strongly affected. Theoretical work has been done on reduced moderation water reactors, which may have a sufficiently fast spectrum to provide a breeding ratio slightly over 1. This would likely result in an unacceptable power derating and high costs in a liquid-water-cooled reactor, but the supercritical water coolant of the supercritical water reactor (SCWR) has sufficient heat capacity to allow adequate cooling with less water, making a fast-spectrum water-cooled reactor a practical possibility.[3]

The type of coolants, temperatures, and fast neutron spectrum puts the fuel cladding material (normally austenitic stainless or ferritic-martensitic steels) under extreme conditions. The understanding of the radiation damage, coolant interactions, stresses, and temperatures are necessary for the safe operation of any reactor core. All materials used to date in sodium-cooled fast reactors have known limits.[6] Oxide dispersion-strengthened alloy steel is viewed as the long-term radiation resistant fuel-cladding material that can overcome the shortcomings of today's material choices.

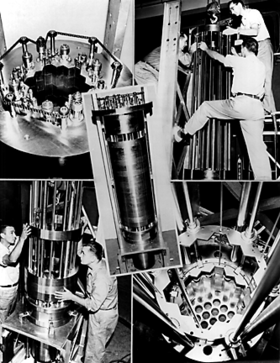

One design of fast neutron reactor, specifically conceived to address the waste disposal and plutonium issues, was the integral fast reactor (IFR, also known as an integral fast breeder reactor, although the original reactor was designed to not breed a net surplus of fissile material).[7][8]

To solve the waste disposal problem, the IFR had an on-site electrowinning fuel-reprocessing unit that recycled the uranium and all the transuranics (not just plutonium) via electroplating, leaving just short-half-life fission products in the waste. Some of these fission products could later be separated for industrial or medical uses and the rest sent to a waste repository. The IFR pyroprocessing system uses molten cadmium cathodes and electrorefiners to reprocess metallic fuel directly on-site at the reactor.[9] Such systems co-mingle all the minor actinides with both uranium and plutonium. The systems are compact and self-contained, so that no plutonium-containing material needs to be transported away from the site of the breeder reactor. Breeder reactors incorporating such technology would most likely be designed with breeding ratios very close to 1.00, so that after an initial loading of enriched uranium and/or plutonium fuel, the reactor would then be refueled only with small deliveries of natural uranium. A quantity of natural uranium equivalent to a block about the size of a milk crate delivered once per month would be all the fuel such a 1 gigawatt reactor would need.[10] Such self-contained breeders are currently envisioned as the final self-contained and self-supporting ultimate goal of nuclear reactor designers.[11][5] The project was canceled in 1994 by United States Secretary of Energy Hazel O'Leary.[12][13]

The first fast reactor built and operated was the Los Alamos Plutonium Fast Reactor ("Clementine") in Los Alamos, NM.[14] Clementine was fueled by Ga-stabilized delta-phase Pu and cooled with mercury. It contained a 'window' of Th-232 in anticipation of breeding experiments, but no reports were made available regarding this feature.

Another proposed fast reactor is a fast molten salt reactor, in which the molten salt's moderating properties are insignificant. This is typically achieved by replacing the light metal fluorides (e.g. LiF, BeF2) in the salt carrier with heavier metal chlorides (e.g., KCl, RbCl, ZrCl4).

Several prototype FBRs have been built, ranging in electrical output from a few light bulbs' equivalent (EBR-I, 1951) to over 1,000 MWe. As of 2006, the technology is not economically competitive to thermal reactor technology, but India, Japan, China, South Korea, and Russia are all committing substantial research funds to further development of fast breeder reactors, anticipating that rising uranium prices will change this in the long term. Germany, in contrast, abandoned the technology due to safety concerns. The SNR-300 fast breeder reactor was finished after 19 years despite cost overruns summing up to a total of €3.6 billion, only to then be abandoned.[15]

The advanced heavy-water reactor is one of the few proposed large-scale uses of thorium.[16] India is developing this technology, motivated by substantial thorium reserves; almost a third of the world's thorium reserves are in India, which lacks significant uranium reserves.

The third and final core of the Shippingport Atomic Power Station 60 MWe reactor was a light water thorium breeder, which began operating in 1977.[17] It used pellets made of thorium dioxide and uranium-233 oxide; initially, the U-233 content of the pellets was 5–6% in the seed region, 1.5–3% in the blanket region, and none in the reflector region. It operated at 236 MWt, generating 60 MWe, and ultimately produced over 2.1 billion kilowatt hours of electricity. After five years, the core was removed and found to contain nearly 1.4% more fissile material than when it was installed, demonstrating that breeding from thorium had occurred.[18][19]

A liquid fluoride thorium reactor is also planned as a thorium thermal breeder. Liquid-fluoride reactors may have attractive features, such as inherent safety, no need to manufacture fuel rods, and possibly simpler reprocessing of the liquid fuel. This concept was first investigated at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory Molten-Salt Reactor Experiment in the 1960s. From 2012 it became the subject of renewed interest worldwide.[20]

Breeder reactors could, in principle, extract almost all of the energy contained in uranium or thorium, decreasing fuel requirements by a factor of 100 compared to widely used once-through light water reactors, which extract less than 1% of the energy in the actinide metal (uranium or thorium) mined from the earth.[11] The high fuel-efficiency of breeder reactors could greatly reduce concerns about fuel supply, energy used in mining, and storage of radioactive waste. With seawater uranium extraction (currently too expensive to be economical), there is enough fuel for breeder reactors to satisfy the world's energy needs for 5 billion years at 1983's total energy consumption rate, thus making nuclear energy effectively a renewable energy.[21][22] In addition to seawater, the average crustal granite rocks contain significant quantities of uranium and thorium that with breeder reactors can supply abundant energy for the remaining lifespan of the sun on the main sequence of stellar evolution.[23]