El comunismo (del latín communis , 'común, universal') [1] [2] es una ideología sociopolítica , filosófica y económica dentro del movimiento socialista , [1] cuyo objetivo es la creación de una sociedad comunista , un orden socioeconómico centrado en la propiedad común de los medios de producción , distribución e intercambio que asigna productos a todos en la sociedad en función de las necesidades. [3] [4] [5] Una sociedad comunista implicaría la ausencia de propiedad privada y clases sociales , [1] y, en última instancia, dinero [6] y el estado (o estado nacional ). [7] [8] [9]

Los comunistas a menudo buscan un estado voluntario de autogobierno, pero no están de acuerdo sobre los medios para lograr este fin. Esto refleja una distinción entre un enfoque socialista más libertario de comunización , espontaneidad revolucionaria y autogestión de los trabajadores , y un enfoque vanguardista más autoritario o impulsado por el partido comunista a través del desarrollo de un estado socialista , seguido por la desaparición del estado . [10] Como una de las principales ideologías en el espectro político , los partidos y movimientos comunistas han sido descritos como de izquierda radical o extrema izquierda. [11] [12] [nota 1]

A lo largo de la historia se han desarrollado variantes del comunismo , incluido el comunismo anarquista , las escuelas de pensamiento marxistas y el comunismo religioso , entre otros. El comunismo abarca una variedad de escuelas de pensamiento, que en términos generales incluyen el marxismo , el leninismo y el comunismo libertario , así como las ideologías políticas agrupadas en torno a ellas. Todas estas diferentes ideologías generalmente comparten el análisis de que el orden actual de la sociedad se deriva del capitalismo , su sistema económico y modo de producción , que en este sistema hay dos clases sociales principales, que la relación entre estas dos clases es explotadora y que esta situación solo puede resolverse en última instancia a través de una revolución social . [20] [nota 2] Las dos clases son el proletariado , que constituye la mayoría de la población dentro de la sociedad y debe vender su fuerza de trabajo para sobrevivir, y la burguesía , una pequeña minoría que obtiene ganancias al emplear a la clase trabajadora a través de la propiedad privada de los medios de producción. [22] Según este análisis, una revolución comunista pondría a la clase obrera en el poder, [23] y a su vez establecería la propiedad común, elemento primordial en la transformación de la sociedad hacia un modo de producción comunista . [24] [25] [26]

El comunismo en su forma moderna surgió del movimiento socialista en Francia en el siglo XVIII , tras la Revolución Francesa . La crítica a la idea de la propiedad privada en la Era de la Ilustración del siglo XVIII a través de pensadores como Gabriel Bonnot de Mably , Jean Meslier , Étienne-Gabriel Morelly , Henri de Saint-Simon y Jean-Jacques Rousseau en Francia. [27] Durante la agitación de la Revolución Francesa , el comunismo surgió como una doctrina política bajo los auspicios de François-Noël Babeuf , Nicolas Restif de la Bretonne y Sylvain Maréchal , todos ellos pueden considerarse los progenitores del comunismo moderno, según James H. Billington . [28] [1] En el siglo XX, varios gobiernos aparentemente comunistas que defendían el marxismo-leninismo y sus variantes llegaron al poder, [29] [nota 3] primero en la Unión Soviética con la Revolución rusa de 1917, y luego en partes de Europa del Este, Asia y algunas otras regiones después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial . [35] Como uno de los muchos tipos de socialismo , el comunismo se convirtió en la tendencia política dominante, junto con la socialdemocracia , dentro del movimiento socialista internacional a principios de la década de 1920. [36]

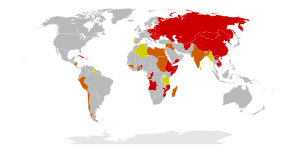

Durante la mayor parte del siglo XX, alrededor de un tercio de la población mundial vivió bajo gobiernos comunistas. Estos gobiernos se caracterizaron por el gobierno de un solo partido por un partido comunista, el rechazo de la propiedad privada y el capitalismo, el control estatal de la actividad económica y los medios de comunicación , las restricciones a la libertad de religión y la supresión de la oposición y el disenso. Con la disolución de la Unión Soviética en 1991, varios gobiernos previamente comunistas repudiaron o abolieron el gobierno comunista por completo. [1] [37] [38] Después, solo quedó un pequeño número de gobiernos nominalmente comunistas, como China , [39] Cuba , Laos , Corea del Norte , [nota 4] y Vietnam . [46] Con la excepción de Corea del Norte, todos estos estados han comenzado a permitir una mayor competencia económica manteniendo el gobierno de un solo partido. [1] El declive del comunismo a fines del siglo XX se ha atribuido a las ineficiencias inherentes de las economías comunistas y la tendencia general de los gobiernos comunistas hacia el autoritarismo y la burocracia . [1] [46] [47]

Si bien el surgimiento de la Unión Soviética como el primer estado nominalmente comunista del mundo condujo a la asociación generalizada del comunismo con el modelo económico soviético , varios académicos postulan que en la práctica el modelo funcionó como una forma de capitalismo de Estado . [48] [49] La memoria pública de los estados comunistas del siglo XX ha sido descrita como un campo de batalla entre el anticomunismo y el anticomunismo . [50] Muchos autores han escrito sobre asesinatos en masa bajo regímenes comunistas y tasas de mortalidad , [nota 5] como el exceso de mortalidad en la Unión Soviética bajo Joseph Stalin , [nota 6] que siguen siendo temas controvertidos, polarizados y debatidos en la academia, la historiografía y la política cuando se habla del comunismo y el legado de los estados comunistas. [68] [69]

El término comunismo deriva de la palabra francesa communisme , una combinación de la palabra de raíz latina communis (que literalmente significa común ) y el sufijo isme ( un acto, práctica o proceso de hacer algo ) . [70] [71] Semánticamente, communis puede traducirse como "de o para la comunidad", mientras que isme es un sufijo que indica la abstracción en un estado, condición, acción o doctrina . El comunismo puede interpretarse como "el estado de ser de o para la comunidad"; esta constitución semántica ha llevado a numerosos usos de la palabra en su evolución. Antes de asociarse con su concepción más moderna de una organización económica y política, inicialmente se utilizó para designar varias situaciones sociales. Después de 1848, el comunismo pasó a asociarse principalmente con el marxismo , más específicamente encarnado en El Manifiesto Comunista , que proponía un tipo particular de comunismo. [1] [72]

Uno de los primeros usos de la palabra en su sentido moderno se encuentra en una carta enviada por Victor d'Hupay a Nicolas Restif de la Bretonne alrededor de 1785, en la que d'Hupay se describe a sí mismo como un autor comunista ("autor comunista"). [73] En 1793, Restif utilizó por primera vez el término "comunismo" para describir un orden social basado en el igualitarismo y la propiedad común de la propiedad. [74] Restif continuaría utilizando el término con frecuencia en sus escritos y fue el primero en describir el comunismo como una forma de gobierno . [75] A John Goodwyn Barmby se le atribuye el primer uso de comunismo en inglés, alrededor de 1840. [70]

Desde la década de 1840, el término comunismo se ha distinguido habitualmente del socialismo . La definición y el uso modernos del término socialismo se establecieron en la década de 1860, pasando a predominar sobre términos alternativos como asociacionismo ( fourierismo ), mutualismo o cooperativismo , que anteriormente se habían utilizado como sinónimos. Mientras tanto, el término comunismo cayó en desuso durante este período. [76]

Una distinción temprana entre comunismo y socialismo fue que el último apuntaba solo a socializar la producción , mientras que el primero apuntaba a socializar tanto la producción como el consumo (en la forma de acceso común a los bienes finales ). [5] Esta distinción se puede observar en el comunismo de Marx, donde la distribución de productos se basa en el principio de " a cada uno según sus necesidades ", en contraste con un principio socialista de " a cada uno según su contribución ". [25] El socialismo ha sido descrito como una filosofía que busca la justicia distributiva, y el comunismo como un subconjunto del socialismo que prefiere la igualdad económica como su forma de justicia distributiva. [77]

En la Europa del siglo XIX, el uso de los términos comunismo y socialismo finalmente coincidió con la actitud cultural de los partidarios y oponentes hacia la religión . En la cristiandad europea , se creía que el comunismo era la forma de vida atea . En la Inglaterra protestante , el comunismo era demasiado similar fonéticamente al rito de comunión católico romano , por lo que los ateos ingleses se autodenominaban socialistas. [78] Friedrich Engels afirmó que en 1848, en el momento en que se publicó por primera vez El manifiesto comunista , [79] el socialismo era respetable en el continente, mientras que el comunismo no lo era; los owenistas en Inglaterra y los fourieristas en Francia eran considerados socialistas respetables, mientras que los movimientos de la clase trabajadora que "proclamaban la necesidad de un cambio social total" se autodenominaban comunistas . Esta última rama del socialismo produjo la obra comunista de Étienne Cabet en Francia y Wilhelm Weitling en Alemania. [80] Mientras que los demócratas liberales veían las revoluciones de 1848 como una revolución democrática , que a largo plazo aseguraba la libertad, la igualdad y la fraternidad , los marxistas denunciaban 1848 como una traición a los ideales de la clase trabajadora por parte de una burguesía indiferente a las demandas legítimas del proletariado . [81]

En 1888, los marxistas emplearon el término socialismo en lugar de comunismo , que había llegado a considerarse un sinónimo anticuado del primero. No fue hasta 1917, con la Revolución de Octubre , que el socialismo pasó a usarse para referirse a una etapa distinta entre el capitalismo y el comunismo. Esta etapa intermedia fue un concepto introducido por Vladimir Lenin como un medio para defender la toma del poder por los bolcheviques contra la crítica marxista tradicional de que las fuerzas productivas de Rusia no estaban lo suficientemente desarrolladas para la revolución socialista . [24] Una distinción entre comunista y socialista como descriptores de ideologías políticas surgió en 1918 después de que el Partido Obrero Socialdemócrata Ruso se rebautizara como Partido Comunista de la Unión Soviética , lo que resultó en que el adjetivo comunista se usara para referirse a los socialistas que apoyaban la política y las teorías del bolchevismo, el leninismo y, más tarde, en la década de 1920, las del marxismo-leninismo . [82] A pesar de este uso común, los partidos comunistas también continuaron describiéndose como socialistas dedicados al socialismo. [76]

Según The Oxford Handbook of Karl Marx , «Marx utilizó muchos términos para referirse a una sociedad postcapitalista: humanismo positivo, socialismo, comunismo, reino de la individualidad libre, libre asociación de productores, etc. Utilizó estos términos de manera completamente intercambiable. La noción de que «socialismo» y «comunismo» son etapas históricas distintas es ajena a su obra y solo entró en el léxico del marxismo después de su muerte». [83] Según la Encyclopædia Britannica , «exactamente en qué se diferencia el comunismo del socialismo ha sido durante mucho tiempo un tema de debate, pero la distinción se basa en gran medida en la adhesión de los comunistas al socialismo revolucionario de Karl Marx». [1]

En los Estados Unidos, el término comunismo se usa ampliamente como un término peyorativo como parte de un pánico rojo , al igual que el socialismo , y principalmente en referencia al socialismo autoritario y los estados comunistas . El surgimiento de la Unión Soviética como el primer estado nominalmente comunista del mundo llevó a la asociación generalizada del término con el marxismo-leninismo y el modelo de planificación económica de tipo soviético . [1] [84] [85] En su ensayo "Judging Nazism and Communism", [86] Martin Malia define una categoría de "comunismo genérico" como cualquier movimiento de partido político comunista liderado por intelectuales ; este término general permite agrupar regímenes tan diferentes como el industrialismo soviético radical y el antiurbanismo de los Jemeres Rojos . [87] Según Alexander Dallin , la idea de agrupar diferentes países, como Afganistán y Hungría , no tiene una explicación adecuada. [88]

Si bien los historiadores, politólogos y medios de comunicación occidentales utilizan el término Estado comunista para referirse a países gobernados por partidos comunistas, estos estados socialistas no se describen a sí mismos como comunistas ni afirman haber alcanzado el comunismo; se refieren a sí mismos como un estado socialista que está en proceso de construir el comunismo. [89] Los términos utilizados por los estados comunistas incluyen estados nacional-democráticos , democráticos populares , de orientación socialista y de trabajadores y campesinos . [90]

Según Richard Pipes , [91] la idea de una sociedad igualitaria y sin clases surgió por primera vez en la antigua Grecia . Desde el siglo XX, la antigua Roma ha sido examinada en este contexto, así como pensadores como Aristóteles , Cicerón , Demóstenes , Platón y Tácito . Platón, en particular, ha sido considerado como un posible teórico comunista o socialista, [92] o como el primer autor en considerar seriamente el comunismo. [93] El movimiento Mazdak del siglo V en Persia (actual Irán) ha sido descrito como comunista por desafiar los enormes privilegios de las clases nobles y el clero , criticar la institución de la propiedad privada y esforzarse por crear una sociedad igualitaria. [94] [95] En un momento u otro, existieron varias pequeñas comunidades comunistas, generalmente bajo la inspiración de textos religiosos . [53]

En la Iglesia cristiana medieval , algunas comunidades monásticas y órdenes religiosas compartían sus tierras y otras propiedades. Las sectas consideradas heréticas, como los valdenses, predicaban una forma temprana de comunismo cristiano . [96] [97] Como resumen los historiadores Janzen Rod y Max Stanton, los huteritas creían en la estricta adhesión a los principios bíblicos, la disciplina eclesiástica y practicaban una forma de comunismo. En sus palabras, los huteritas "establecieron en sus comunidades un riguroso sistema de Ordnungen, que eran códigos de reglas y regulaciones que gobernaban todos los aspectos de la vida y aseguraban una perspectiva unificada. Como sistema económico, el comunismo era atractivo para muchos de los campesinos que apoyaban la revolución social en la Europa central del siglo XVI". [98] Este vínculo fue resaltado en uno de los primeros escritos de Karl Marx ; Marx afirmó que "así como Cristo es el intermediario a quien el hombre descarga toda su divinidad, todos sus vínculos religiosos, así también el Estado es el mediador al que transfiere toda su impiedad, toda su libertad humana". [99] Thomas Müntzer lideró un gran movimiento comunista anabaptista durante la Guerra de los Campesinos Alemanes , que Friedrich Engels analizó en su obra de 1850 La guerra campesina en Alemania . El ethos comunista marxista que apunta a la unidad refleja la enseñanza universalista cristiana de que la humanidad es una y que solo hay un dios que no discrimina entre las personas. [100]

El pensamiento comunista también se remonta a las obras del escritor inglés del siglo XVI Thomas More . [101] En su tratado de 1516 titulado Utopía , Moro retrató una sociedad basada en la propiedad común , cuyos gobernantes la administraban mediante la aplicación de la razón y la virtud . [102] El teórico comunista marxista Karl Kautsky , quien popularizó el comunismo marxista en Europa occidental más que cualquier otro pensador aparte de Engels, publicó Thomas More and His Utopía , una obra sobre Moro, cuyas ideas podrían considerarse como "el anticipo del socialismo moderno" según Kautsky. Durante la Revolución de Octubre en Rusia, Vladimir Lenin sugirió que se dedicara un monumento a Moro, junto con otros importantes pensadores occidentales. [103]

En el siglo XVII, el pensamiento comunista resurgió en Inglaterra, donde un grupo religioso puritano conocido como los Diggers abogó por la abolición de la propiedad privada de la tierra. En su obra Cromwell and Communism (Cromwell y el comunismo) de 1895 , [104] Eduard Bernstein afirmó que varios grupos durante la Guerra Civil Inglesa (especialmente los Diggers) defendieron claros ideales comunistas y agraristas y que la actitud de Oliver Cromwell hacia estos grupos era, en el mejor de los casos, ambivalente y a menudo hostil. [105] [106] La crítica a la idea de la propiedad privada continuó hasta la Era de la Ilustración del siglo XVIII a través de pensadores como Gabriel Bonnot de Mably , Jean Meslier , Étienne-Gabriel Morelly y Jean-Jacques Rousseau en Francia. [107] Durante la agitación de la Revolución Francesa , el comunismo surgió como doctrina política bajo los auspicios de François-Noël Babeuf , Nicolas Restif de la Bretonne y Sylvain Maréchal , todos ellos pueden considerarse los progenitores del comunismo moderno, según James H. Billington . [28]

A principios del siglo XIX, varios reformadores sociales fundaron comunidades basadas en la propiedad común. A diferencia de muchas comunidades comunistas anteriores, reemplazaron el énfasis religioso con una base racional y filantrópica. [108] Entre ellos se destacan Robert Owen , quien fundó New Harmony, Indiana , en 1825, y Charles Fourier , cuyos seguidores organizaron otros asentamientos en los Estados Unidos, como Brook Farm en 1841. [1] En su forma moderna, el comunismo surgió del movimiento socialista en la Europa del siglo XIX. A medida que avanzaba la Revolución Industrial , los críticos socialistas culparon al capitalismo por la miseria del proletariado , una nueva clase de trabajadores de fábricas urbanas que trabajaban en condiciones a menudo peligrosas. Los principales entre estos críticos fueron Marx y su asociado Engels. En 1848, Marx y Engels ofrecieron una nueva definición de comunismo y popularizaron el término en su famoso panfleto El Manifiesto Comunista . [1]

En 1917, la Revolución de Octubre en Rusia sentó las condiciones para el ascenso al poder estatal de los bolcheviques de Vladimir Lenin , que fue la primera vez que un partido declaradamente comunista alcanzó esa posición. La revolución transfirió el poder al Congreso Panruso de los Soviets en el que los bolcheviques tenían mayoría. [109] [110] [111] El evento generó una gran cantidad de debates prácticos y teóricos dentro del movimiento marxista, ya que Marx afirmó que el socialismo y el comunismo se construirían sobre los cimientos establecidos por el desarrollo capitalista más avanzado; sin embargo, el Imperio ruso era uno de los países más pobres de Europa con un campesinado enorme, en gran parte analfabeto, y una minoría de trabajadores industriales. Marx advirtió contra los intentos de "transformar mi bosquejo histórico de la génesis del capitalismo en Europa occidental en una teoría histórico-filosófica del arche générale impuesto por el destino a cada pueblo, cualesquiera sean las circunstancias históricas en las que se encuentre", [112] y afirmó que Rusia podría ser capaz de saltarse la etapa del gobierno burgués a través de la Obshchina . [113] [nota 7] Los mencheviques moderados (minoría) se opusieron al plan de los bolcheviques (mayoría) de Lenin para la revolución socialista antes de que el modo de producción capitalista estuviera más plenamente desarrollado. El exitoso ascenso de los bolcheviques al poder se basó en lemas como "Paz, pan y tierra", que aprovecharon el deseo público masivo de poner fin a la participación rusa en la Primera Guerra Mundial , la demanda de los campesinos de una reforma agraria y el apoyo popular a los soviets . [117] 50.000 trabajadores habían aprobado una resolución a favor de la demanda bolchevique de transferencia del poder a los soviets . [118] [119] El gobierno de Lenin también instituyó una serie de medidas progresistas como la educación universal , la atención sanitaria y la igualdad de derechos para las mujeres . [120] [121] [122] La etapa inicial de la Revolución de Octubre que implicó el asalto a Petrogrado ocurrió en gran medida sin víctimas humanas . [123] [124] [125] [ página necesaria ]

En noviembre de 1917, el Gobierno Provisional Ruso había quedado ampliamente desacreditado por su fracaso en retirarse de la Primera Guerra Mundial, implementar la reforma agraria o convocar a la Asamblea Constituyente Rusa para redactar una constitución, dejando a los soviets en control de facto del país. Los bolcheviques pasaron a entregar el poder al Segundo Congreso Panruso de los Soviets de Diputados Obreros y Soldados en la Revolución de Octubre; después de unas semanas de deliberación, los socialistas revolucionarios de izquierda formaron un gobierno de coalición con los bolcheviques desde noviembre de 1917 hasta julio de 1918, mientras que la facción de derecha del Partido Socialista Revolucionario boicoteó los soviets y denunció la Revolución de Octubre como un golpe ilegal . En la elección de la Asamblea Constituyente Rusa de 1917 , los partidos socialistas sumaron más del 70% de los votos. Los bolcheviques fueron claros ganadores en los centros urbanos, y se llevaron alrededor de dos tercios de los votos de los soldados en el Frente Occidental, obteniendo el 23,3% de los votos; los socialrevolucionarios terminaron primeros gracias al apoyo del campesinado rural del país, que en su mayoría eran votantes de una sola cuestión , siendo esa cuestión la reforma agraria, obteniendo el 37,6%, mientras que el Bloque Socialista Ucraniano terminó en un distante tercer lugar con el 12,7%, y los mencheviques obtuvieron un decepcionante cuarto lugar con el 3,0%. [126]

La mayoría de los escaños del Partido Socialista Revolucionario fueron para la facción de derecha. Citando padrones electorales obsoletos, que no reconocían la división del partido, y los conflictos de la asamblea con el Congreso de los Soviets, el gobierno bolchevique-socialistas revolucionarios de izquierda movió la mano para disolver la Asamblea Constituyente en enero de 1918. El Proyecto de Decreto sobre la Disolución de la Asamblea Constituyente fue emitido por el Comité Ejecutivo Central de la Unión Soviética , un comité dominado por Lenin, quien previamente había apoyado un sistema multipartidista de elecciones libres. Después de la derrota bolchevique, Lenin comenzó a referirse a la asamblea como una "forma engañosa de parlamentarismo democrático-burgués". [126] Algunos argumentaron que este fue el comienzo del desarrollo del vanguardismo como un partido-élite jerárquico que controla la sociedad, [127] lo que resultó en una división entre el anarquismo y el marxismo , y el comunismo leninista asumiendo la posición dominante durante la mayor parte del siglo XX, excluyendo corrientes socialistas rivales. [128]

Otros comunistas y marxistas, especialmente socialdemócratas que favorecían el desarrollo de la democracia liberal como requisito previo al socialismo , fueron críticos con los bolcheviques desde el principio debido a que Rusia era vista como demasiado atrasada para una revolución socialista . [24] El comunismo de consejos y el comunismo de izquierda , inspirados en la Revolución alemana de 1918-1919 y la amplia ola revolucionaria proletaria , surgieron en respuesta a los acontecimientos en Rusia y son críticos con los estados constitucionalmente socialistas autoproclamados . Algunos partidos de izquierda, como el Partido Socialista de Gran Bretaña , se jactaron de haber llamado a los bolcheviques, y por extensión a aquellos estados comunistas que siguieron o se inspiraron en el modelo de desarrollo bolchevique soviético, establecer el capitalismo de Estado a fines de 1917, como lo describirían durante el siglo XX varios académicos, economistas y otros académicos, [48] o una economía de comando . [129] [130] [131] Antes de que el camino soviético de desarrollo fuera conocido como socialismo , en referencia a la teoría de dos etapas , los comunistas no hacían una distinción importante entre el modo de producción socialista y el comunismo; [83] es consistente con, y ayudó a informar, los conceptos tempranos del socialismo en los que la ley del valor ya no dirige la actividad económica. Las relaciones monetarias en forma de valor de cambio , ganancia , interés y trabajo asalariado no funcionarían ni se aplicarían al socialismo marxista. [26]

Mientras que Joseph Stalin afirmó que la ley del valor todavía se aplicaría al socialismo y que la Unión Soviética era socialista bajo esta nueva definición, que fue seguida por otros líderes comunistas, muchos otros comunistas mantienen la definición original y afirman que los estados comunistas nunca establecieron el socialismo en este sentido. Lenin describió sus políticas como capitalismo de Estado, pero las vio como necesarias para el desarrollo del socialismo, que los críticos de izquierda dicen que nunca se estableció, mientras que algunos marxistas-leninistas afirman que se estableció solo durante la era de Stalin y la era de Mao , y luego se convirtió en estados capitalistas gobernados por revisionistas ; otros afirman que la China maoísta siempre fue capitalista de Estado y defienden a la República Popular Socialista de Albania como el único estado socialista después de la Unión Soviética bajo Stalin, [132] [133] quien primero declaró haber logrado el socialismo con la Constitución de la Unión Soviética de 1936. [ 134]

El comunismo de guerra fue el primer sistema adoptado por los bolcheviques durante la Guerra Civil Rusa como resultado de los muchos desafíos. [135] A pesar del comunismo en el nombre, no tenía nada que ver con el comunismo, con una estricta disciplina para los trabajadores, acciones de huelga prohibidas, deberes laborales obligatorios y control de estilo militar, y ha sido descrito como un simple control autoritario por parte de los bolcheviques para mantener el poder y el control en las regiones soviéticas, en lugar de cualquier ideología política coherente . [136] La Unión Soviética se estableció en 1922. Antes de la amplia prohibición en 1921, había varias facciones en el Partido Comunista, más prominentemente entre ellas la Oposición de Izquierda , la Oposición de Derecha y la Oposición Obrera , que debatían sobre el camino de desarrollo a seguir. Las oposiciones de izquierda y de los trabajadores fueron más críticas con el desarrollo del capitalismo de estado y los trabajadores en particular criticaron la burocratización y el desarrollo desde arriba, mientras que la Oposición de Derecha apoyó más el desarrollo del capitalismo de estado y abogó por la Nueva Política Económica . [135] Siguiendo el centralismo democrático de Lenin , los partidos leninistas se organizaron sobre una base jerárquica, con células activas de miembros como base amplia. Estaban compuestos solo por cuadros de élite aprobados por miembros superiores del partido como confiables y completamente sujetos a la disciplina del partido . [137] El trotskismo superó a los comunistas de izquierda como la principal corriente comunista disidente, mientras que los comunismos más libertarios , que se remontan a la corriente marxista libertaria del comunismo de consejos, siguieron siendo comunismos disidentes importantes fuera de la Unión Soviética. Siguiendo el centralismo democrático de Lenin , los partidos leninistas se organizaron sobre una base jerárquica, con células activas de miembros como base amplia. Estaban compuestos únicamente por cuadros de élite aprobados por los miembros superiores del partido como confiables y completamente sujetos a la disciplina del partido . La Gran Purga de 1936-1938 fue el intento de Joseph Stalin de destruir cualquier posible oposición dentro del Partido Comunista de la Unión Soviética . En los juicios de Moscú , muchos viejos bolcheviques que habían desempeñado papeles destacados durante la Revolución rusa o en el gobierno soviético de Lenin después, incluido Lev Kamenev ,Grigory Zinoviev , Alexei Rykov y Nikolai Bukharin fueron acusados, se declararon culpables de conspiración contra la Unión Soviética y fueron ejecutados. [138] [137]

La devastación de la Segunda Guerra Mundial dio lugar a un programa de recuperación masivo que implicó la reconstrucción de plantas industriales, viviendas y transporte, así como la desmovilización y migración de millones de soldados y civiles. En medio de esta agitación durante el invierno de 1946-1947, la Unión Soviética experimentó la peor hambruna natural del siglo XX. [139] No hubo una oposición seria a Stalin mientras la policía secreta continuaba enviando posibles sospechosos al gulag . Las relaciones con Estados Unidos y Gran Bretaña pasaron de amistosas a hostiles, ya que denunciaron los controles políticos de Stalin sobre Europa del Este y su Bloqueo de Berlín . En 1947, había comenzado la Guerra Fría . El propio Stalin creía que el capitalismo era una cáscara vacía y se desmoronaría bajo una mayor presión no militar ejercida a través de representantes en países como Italia. Subestimó enormemente la fuerza económica de Occidente y, en lugar de triunfar, vio a Occidente construir alianzas diseñadas para detener o contener permanentemente la expansión soviética. A principios de 1950, Stalin dio el visto bueno a la invasión de Corea del Norte a Corea del Sur , esperando una guerra corta. Quedó atónito cuando los estadounidenses entraron y derrotaron a los norcoreanos, poniéndolos casi en la frontera soviética. Stalin apoyó la entrada de China en la Guerra de Corea , que obligó a los estadounidenses a retroceder a las fronteras anteriores a la guerra, pero que aumentó las tensiones. Estados Unidos decidió movilizar su economía para una larga contienda con los soviéticos, construyó la bomba de hidrógeno y fortaleció la alianza de la OTAN que cubría Europa occidental . [140]

Según Gorlizki y Khlevniuk, el objetivo constante y primordial de Stalin después de 1945 fue consolidar el estatus de superpotencia de la nación y, frente a su creciente decrepitud física, mantener su propio control del poder total. Stalin creó un sistema de liderazgo que reflejaba los estilos históricos zaristas de paternalismo y represión, pero que también era bastante moderno. En la cima, la lealtad personal a Stalin contaba para todo. Stalin también creó comités poderosos, elevó a especialistas más jóvenes y comenzó a realizar importantes innovaciones institucionales. A pesar de la persecución, los lugartenientes de Stalin cultivaron normas informales y entendimientos mutuos que proporcionaron las bases para el gobierno colectivo después de su muerte. [139]

Para la mayoría de los occidentales y los rusos anticomunistas , Stalin es visto de forma abrumadoramente negativa como un asesino en masa ; para un número significativo de rusos y georgianos, es considerado un gran estadista y constructor del Estado. [141]

Después de la Guerra Civil China , Mao Zedong y el Partido Comunista Chino llegaron al poder en 1949 mientras el gobierno nacionalista encabezado por el Kuomintang huía a la isla de Taiwán. En 1950-1953, China participó en una guerra no declarada a gran escala con los Estados Unidos, Corea del Sur y las fuerzas de las Naciones Unidas en la Guerra de Corea . Si bien la guerra terminó en un punto muerto militar, le dio a Mao la oportunidad de identificar y purgar a los elementos en China que parecían apoyar al capitalismo. Al principio, hubo una estrecha cooperación con Stalin, quien envió expertos técnicos para ayudar al proceso de industrialización siguiendo la línea del modelo soviético de la década de 1930. [142] Después de la muerte de Stalin en 1953, las relaciones con Moscú se deterioraron: Mao pensó que los sucesores de Stalin habían traicionado el ideal comunista. Mao acusó al líder soviético Nikita Khrushchev de ser el líder de una "camarilla revisionista" que se había vuelto contra el marxismo y el leninismo y ahora estaba preparando el escenario para la restauración del capitalismo. [143] En 1960, las dos naciones estaban enfrentadas. Ambas comenzaron a forjar alianzas con partidarios comunistas de todo el mundo, dividiendo así el movimiento mundial en dos bandos hostiles. [144]

Mao Zedong y su principal colaborador, Deng Xiaoping, rechazaron el modelo soviético de rápida urbanización y lanzaron el Gran Salto Adelante entre 1957 y 1961 con el objetivo de industrializar China de la noche a la mañana, utilizando como base las aldeas campesinas en lugar de las grandes ciudades. [145] La propiedad privada de la tierra terminó y los campesinos trabajaron en grandes granjas colectivas a las que se les ordenó que iniciaran operaciones de industria pesada, como fábricas de acero. Se construyeron plantas en lugares remotos, debido a la falta de expertos técnicos, gerentes, transporte o instalaciones necesarias. La industrialización fracasó y el resultado principal fue una caída abrupta e inesperada de la producción agrícola, que llevó a una hambruna masiva y millones de muertes. Los años del Gran Salto Adelante, de hecho, vieron una regresión económica, siendo 1958 a 1961 los únicos años entre 1953 y 1983 en los que la economía de China experimentó un crecimiento negativo. El economista político Dwight Perkins sostiene: "Enormes cantidades de inversión produjeron sólo modestos aumentos en la producción o ninguno en absoluto... En resumen, el Gran Salto fue un desastre muy costoso". [146] Deng, encargado de rescatar la economía, adoptó políticas pragmáticas que desagradaron al idealista Mao. Durante un tiempo, Mao estuvo en la sombra, pero volvió al centro de la escena y purgó a Deng y sus aliados en la Revolución Cultural (1966-1976). [147]

La Revolución Cultural fue una convulsión que tuvo como blanco a intelectuales y líderes del partido desde 1966 hasta 1976. El objetivo de Mao era purificar el comunismo eliminando a los procapitalistas y tradicionalistas mediante la imposición de la ortodoxia maoísta dentro del Partido Comunista Chino . El movimiento paralizó a China políticamente y debilitó al país económica, cultural e intelectualmente durante años. Millones de personas fueron acusadas, humilladas, despojadas del poder y encarceladas, asesinadas o, más a menudo, enviadas a trabajar como jornaleros agrícolas. Mao insistió en que aquellos a los que etiquetaba como revisionistas fueran eliminados mediante una lucha de clases violenta . Los dos militantes más destacados fueron el mariscal Lin Biao del ejército y la esposa de Mao, Jiang Qing . La juventud china respondió al llamado de Mao formando grupos de Guardias Rojos en todo el país. El movimiento se extendió al ejército, a los trabajadores urbanos y a la propia dirección del Partido Comunista. Resultó en luchas faccionales generalizadas en todos los ámbitos de la vida. En la cúpula dirigente, esto condujo a una purga masiva de altos funcionarios acusados de seguir un " camino capitalista ", sobre todo Liu Shaoqi y Deng Xiaoping . Durante el mismo período, el culto a la personalidad de Mao alcanzó proporciones inmensas. Después de la muerte de Mao en 1976, los supervivientes fueron rehabilitados y muchos volvieron al poder. [148] [ página requerida ]

El gobierno de Mao fue responsable de un gran número de muertes, con estimaciones que van desde 40 a 80 millones de víctimas por hambruna, persecución, trabajo en prisión y ejecuciones masivas. [149] [150] [151] [152] Mao también ha sido elogiado por transformar a China de una semicolonia a una potencia mundial líder, con una alfabetización muy avanzada, derechos de la mujer, atención médica básica, educación primaria y esperanza de vida. [153] [154] [155] [156]

Su papel principal en la Segunda Guerra Mundial vio el surgimiento de la Unión Soviética industrializada como una superpotencia . [157] [158] Los gobiernos marxista-leninistas inspirados en la Unión Soviética tomaron el poder con la asistencia soviética en Bulgaria , Checoslovaquia , Alemania del Este , Polonia , Hungría y Rumania . También se creó un gobierno marxista-leninista bajo Josip Broz Tito en Yugoslavia ; las políticas independientes de Tito llevaron a la división de Tito-Stalin y la expulsión de Yugoslavia del Cominform en 1948, y el titoísmo fue tildado de desviacionista . Albania también se convirtió en un estado marxista-leninista independiente después de la división albano-soviética en 1960, [132] [133] como resultado de una disputa ideológica entre Enver Hoxha , un estalinista, y el gobierno soviético de Nikita Khrushchev , quien promulgó un período de desestalinización y reanudó las relaciones diplomáticas con Yugoslavia en 1976. [159] El Partido Comunista de China, dirigido por Mao Zedong, estableció la República Popular China , que seguiría su propio camino ideológico de desarrollo después de la división chino-soviética . [160] El comunismo fue visto como un rival y una amenaza para el capitalismo occidental durante la mayor parte del siglo XX. [161]

En Europa occidental, los partidos comunistas formaron parte de varios gobiernos de posguerra, e incluso cuando la Guerra Fría obligó a muchos de esos países a sacarlos del gobierno, como en Italia, siguieron siendo parte del proceso liberal-democrático . [162] [163] También hubo muchos avances en el marxismo libertario, especialmente durante la década de 1960 con la Nueva Izquierda . [164] En las décadas de 1960 y 1970, muchos partidos comunistas occidentales habían criticado muchas de las acciones de los estados comunistas, se habían distanciado de ellos y habían desarrollado un camino democrático hacia el socialismo , que se conoció como eurocomunismo . [162] Este desarrollo fue criticado por los partidarios más ortodoxos de la Unión Soviética por equivaler a la socialdemocracia . [165]

Desde 1957, los comunistas han sido elegidos con frecuencia para ocupar el poder en el estado indio de Kerala . [166]

En 1959, los revolucionarios comunistas cubanos derrocaron al gobierno anterior de Cuba bajo el dictador Fulgencio Batista . El líder de la Revolución cubana, Fidel Castro , gobernó Cuba desde 1959 hasta 2008. [167]

Con la caída del Pacto de Varsovia tras las Revoluciones de 1989 , que condujeron a la caída de la mayor parte del antiguo Bloque del Este , la Unión Soviética se disolvió el 26 de diciembre de 1991. Fue resultado de la declaración número 142-Н del Soviet de las Repúblicas del Soviet Supremo de la Unión Soviética . [168] La declaración reconoció la independencia de las antiguas repúblicas soviéticas y creó la Comunidad de Estados Independientes , aunque cinco de los firmantes la ratificaron mucho más tarde o no lo hicieron en absoluto. El día anterior, el presidente soviético Mijaíl Gorbachov (el octavo y último líder de la Unión Soviética ) dimitió, declaró extinto su cargo y entregó sus poderes, incluido el control del Cheget , al presidente ruso Borís Yeltsin . Esa tarde a las 7:32, la bandera soviética fue bajada del Kremlin por última vez y sustituida por la bandera rusa prerrevolucionaria . Anteriormente, de agosto a diciembre de 1991, todas las repúblicas individuales, incluida la propia Rusia, se habían separado de la unión. La semana anterior a la disolución formal de la unión, once repúblicas firmaron el Protocolo de Alma-Ata , que estableció formalmente la Comunidad de Estados Independientes , y declararon que la Unión Soviética había dejado de existir. [169] [170]

A partir de 2023, los estados controlados por partidos marxistas-leninistas bajo un sistema de partido único incluyen la República Popular China, la República de Cuba , la República Democrática Popular Lao y la República Socialista de Vietnam . [nota 4] Los partidos comunistas, o sus partidos descendientes, siguen siendo políticamente importantes en varios otros países. Con la disolución de la Unión Soviética y la caída del comunismo , hubo una división entre los comunistas de línea dura, a veces denominados en los medios de comunicación como neoestalinistas , que seguían comprometidos con el marxismo-leninismo ortodoxo , y aquellos, como La Izquierda en Alemania, que trabajan dentro del proceso liberal-democrático por un camino democrático al socialismo; [171] otros partidos comunistas gobernantes se acercaron a los partidos socialdemócratas y socialdemócratas democráticos . [172] Fuera de los estados comunistas, los partidos comunistas reformados han liderado o han sido parte de gobiernos de izquierda o coaliciones regionales, incluso en el antiguo Bloque del Este. En Nepal, los comunistas ( CPN UML y Partido Comunista de Nepal ) fueron parte de la 1.ª Asamblea Constituyente Nepalesa , que abolió la monarquía en 2008 y convirtió al país en una república federal liberal-democrática, y han compartido democráticamente el poder con otros comunistas, marxistas-leninistas y maoístas ( CPN Maoísta ), socialdemócratas ( Congreso Nepalí ) y otros como parte de su Democracia Popular Multipartidaria . [173] [174] El Partido Comunista de la Federación Rusa tiene algunos partidarios, pero es reformista más que revolucionario, y tiene como objetivo reducir las desigualdades de la economía de mercado de Rusia. [1]

Las reformas económicas chinas se iniciaron en 1978 bajo el liderazgo de Deng Xiaoping , y desde entonces China ha logrado reducir la tasa de pobreza del 53% en la era de Mao a sólo el 8% en 2001. [175] Después de perder los subsidios y el apoyo soviéticos, Vietnam y Cuba han atraído más inversión extranjera a sus países, y sus economías se han vuelto más orientadas al mercado. [1] Corea del Norte, el último país comunista que todavía practica el comunismo al estilo soviético, es a la vez represivo y aislacionista. [1]

El pensamiento y la teoría política comunistas son diversos, pero comparten varios elementos centrales. [a] Las formas dominantes del comunismo se basan en el marxismo o el leninismo , pero también existen versiones no marxistas del comunismo, como el anarcocomunismo y el comunismo cristiano , que siguen estando parcialmente influenciadas por las teorías marxistas, como el marxismo libertario y el marxismo humanista en particular. Los elementos comunes incluyen ser teórico en lugar de ideológico, identificar a los partidos políticos no por ideología sino por clase e interés económico, e identificarse con el proletariado. Según los comunistas, el proletariado puede evitar el desempleo masivo solo si se derroca al capitalismo; en el corto plazo, los comunistas orientados al Estado favorecen la propiedad estatal de las alturas dominantes de la economía como un medio para defender al proletariado de la presión capitalista. Algunos comunistas se distinguen de otros marxistas en ver a los campesinos y pequeños propietarios como posibles aliados en su objetivo de acortar la abolición del capitalismo. [177]

Para el comunismo leninista, tales objetivos, incluidos los intereses proletarios a corto plazo para mejorar sus condiciones políticas y materiales, solo pueden lograrse a través del vanguardismo , una forma elitista de socialismo desde arriba que se basa en el análisis teórico para identificar los intereses proletarios en lugar de consultar a los propios proletarios, [177] como lo defienden los comunistas libertarios . [10] Cuando participan en elecciones, la principal tarea de los comunistas leninistas es la de educar a los votantes en lo que se consideran sus verdaderos intereses en lugar de responder a la expresión de interés de los propios votantes. Cuando han obtenido el control del estado, la principal tarea de los comunistas leninistas fue evitar que otros partidos políticos engañen al proletariado, por ejemplo, presentando sus propios candidatos independientes. Este enfoque vanguardista proviene de sus compromisos con el centralismo democrático en el que los comunistas solo pueden ser cuadros, es decir, miembros del partido que son revolucionarios profesionales a tiempo completo, como lo concibió Vladimir Lenin . [177]

El marxismo es un método de análisis socioeconómico que utiliza una interpretación materialista del desarrollo histórico, mejor conocida como materialismo histórico , para comprender las relaciones de clase social y el conflicto social y una perspectiva dialéctica para ver la transformación social . Tiene su origen en las obras de los filósofos alemanes del siglo XIX Karl Marx y Friedrich Engels . Como el marxismo se ha desarrollado con el tiempo en varias ramas y escuelas de pensamiento , no existe una teoría marxista única y definitiva . [178] El marxismo se considera a sí mismo como la encarnación del socialismo científico , pero no modela una sociedad ideal basada en el diseño de intelectuales , por lo que el comunismo es visto como un estado de cosas que se establecerá en base a cualquier diseño inteligente; más bien, es un intento no idealista de comprender la historia material y la sociedad, por lo que el comunismo es la expresión de un movimiento real, con parámetros que se derivan de la vida real. [179]

Según la teoría marxista, el conflicto de clases surge en las sociedades capitalistas debido a las contradicciones entre los intereses materiales del proletariado oprimido y explotado –una clase de trabajadores asalariados empleados para producir bienes y servicios– y la burguesía –la clase dominante que posee los medios de producción y extrae su riqueza mediante la apropiación del producto excedente producido por el proletariado en forma de ganancia– . Esta lucha de clases que comúnmente se expresa como la revuelta de las fuerzas productivas de una sociedad contra sus relaciones de producción , resulta en un período de crisis de corto plazo a medida que la burguesía lucha por gestionar la intensificación de la alienación del trabajo que experimenta el proletariado, aunque con diversos grados de conciencia de clase . En períodos de crisis profunda, la resistencia de los oprimidos puede culminar en una revolución proletaria que, de ser victoriosa, conduce al establecimiento del modo de producción socialista basado en la propiedad social de los medios de producción, “ a cada cual según su contribución ”, y la producción para el uso . A medida que las fuerzas productivas siguieron avanzando, la sociedad comunista , es decir, una sociedad humana sin clases, sin Estado, basada en la propiedad común , sigue la máxima " De cada uno según su capacidad, a cada uno según sus necesidades ". [83]

Aunque se origina en las obras de Marx y Engels, el marxismo se ha desarrollado en muchas ramas y escuelas de pensamiento diferentes, con el resultado de que ahora no hay una única teoría marxista definitiva. [178] Diferentes escuelas marxistas ponen un mayor énfasis en ciertos aspectos del marxismo clásico mientras rechazan o modifican otros aspectos. Muchas escuelas de pensamiento han tratado de combinar conceptos marxistas y no marxistas, lo que luego ha llevado a conclusiones contradictorias. [180] Existe un movimiento hacia el reconocimiento de que el materialismo histórico y el materialismo dialéctico siguen siendo los aspectos fundamentales de todas las escuelas de pensamiento marxistas . [95] El marxismo-leninismo y sus ramificaciones son las más conocidas de ellas y han sido una fuerza impulsora en las relaciones internacionales durante la mayor parte del siglo XX. [181]

El marxismo clásico son las teorías económicas, filosóficas y sociológicas expuestas por Marx y Engels en contraste con desarrollos posteriores en el marxismo, especialmente el leninismo y el marxismo-leninismo. [182] El marxismo ortodoxo es el cuerpo de pensamiento marxista que surgió después de la muerte de Marx y que se convirtió en la filosofía oficial del movimiento socialista representado en la Segunda Internacional hasta la Primera Guerra Mundial en 1914. El marxismo ortodoxo tiene como objetivo simplificar, codificar y sistematizar el método y la teoría marxistas aclarando las ambigüedades y contradicciones percibidas del marxismo clásico. La filosofía del marxismo ortodoxo incluye la comprensión de que el desarrollo material (avances en la tecnología en las fuerzas productivas ) es el agente principal del cambio en la estructura de la sociedad y de las relaciones sociales humanas y que los sistemas sociales y sus relaciones (por ejemplo, el feudalismo , el capitalismo , etc.) se vuelven contradictorios e ineficientes a medida que se desarrollan las fuerzas productivas, lo que da como resultado alguna forma de revolución social que surge en respuesta a las crecientes contradicciones. Este cambio revolucionario es el vehículo para cambios fundamentales en toda la sociedad y en última instancia conduce al surgimiento de nuevos sistemas económicos . [183] Como término, el marxismo ortodoxo representa los métodos del materialismo histórico y del materialismo dialéctico, y no los aspectos normativos inherentes al marxismo clásico, sin implicar una adhesión dogmática a los resultados de las investigaciones de Marx. [184]

En la raíz del marxismo está el materialismo histórico, la concepción materialista de la historia que sostiene que la característica clave de los sistemas económicos a través de la historia ha sido el modo de producción y que el cambio entre modos de producción ha sido desencadenado por la lucha de clases. Según este análisis, la Revolución Industrial condujo al mundo hacia el nuevo modo de producción capitalista . Antes del capitalismo, ciertas clases trabajadoras tenían la propiedad de los instrumentos utilizados en la producción; sin embargo, debido a que la maquinaria era mucho más eficiente, esta propiedad perdió valor y la gran mayoría de los trabajadores solo podía sobrevivir vendiendo su trabajo para hacer uso de la maquinaria de otra persona y hacer que alguien más se beneficiara. En consecuencia, el capitalismo dividió el mundo en dos clases principales, a saber, el proletariado y la burguesía . Estas clases son directamente antagónicas ya que esta última posee la propiedad privada de los medios de producción , obteniendo ganancias a través del plusvalor generado por el proletariado, que no tiene la propiedad de los medios de producción y, por lo tanto, no tiene otra opción que vender su trabajo a la burguesía. [185]

Según la concepción materialista de la historia, es a través de la promoción de sus propios intereses materiales que la burguesía ascendente dentro del feudalismo tomó el poder y abolió, de todas las relaciones de propiedad privada, solo el privilegio feudal, eliminando así la existencia de la clase dominante feudal . Este fue otro elemento clave detrás de la consolidación del capitalismo como el nuevo modo de producción, la expresión final de las relaciones de clase y propiedad que ha llevado a una expansión masiva de la producción. Es solo en el capitalismo que la propiedad privada en sí puede ser abolida. [186] De manera similar, el proletariado tomaría el poder político, aboliría la propiedad burguesa a través de la propiedad común de los medios de producción, aboliendo así a la burguesía, aboliendo en última instancia al proletariado mismo y conduciendo al mundo al comunismo como un nuevo modo de producción . Entre el capitalismo y el comunismo, está la dictadura del proletariado ; Es la derrota del Estado burgués , pero no todavía del modo de producción capitalista, y al mismo tiempo el único elemento que pone en el campo de la posibilidad la superación de este modo de producción. Esta dictadura , basada en el modelo de la Comuna de París [187] , debe ser el Estado más democrático en el que todo el poder público sea elegido y revocable sobre la base del sufragio universal . [188]

La crítica de la economía política es una forma de crítica social que rechaza las diversas categorías y estructuras sociales que constituyen el discurso dominante sobre las formas y modalidades de asignación de recursos y distribución del ingreso en la economía. Los comunistas, como Marx y Engels, son descritos como destacados críticos de la economía política. [189] [190] [191] La crítica rechaza el uso que hacen los economistas de lo que sus defensores creen que son axiomas poco realistas , supuestos históricos defectuosos y el uso normativo de varias narrativas descriptivas. [192] Rechazan lo que describen como la tendencia de los economistas dominantes a postular la economía como una categoría social a priori . [193] Quienes se dedican a la crítica de la economía tienden a rechazar la visión de que la economía y sus categorías deben entenderse como algo transhistórico . [194] [195] Se la ve simplemente como uno de los muchos tipos de formas históricamente específicas de distribuir los recursos. Argumentan que es un modo relativamente nuevo de distribución de recursos, que surgió junto con la modernidad. [196] [197] [198]

Los críticos de la economía critican el estatus dado de la economía en sí, y no pretenden crear teorías sobre cómo administrar las economías. [199] [200] Los críticos de la economía comúnmente ven lo que se conoce más comúnmente como la economía como un conjunto de conceptos metafísicos , así como prácticas sociales y normativas, en lugar de ser el resultado de leyes económicas evidentes o proclamadas. [193] También tienden a considerar las opiniones que son comunes dentro del campo de la economía como defectuosas, o simplemente como pseudociencia . [201] [202] En el siglo XXI, hay múltiples críticas a la economía política; lo que tienen en común es la crítica de lo que los críticos de la economía política tienden a ver como dogma , es decir, afirmaciones de la economía como una categoría social necesaria y transhistórica. [203]

La economía marxista y sus defensores consideran que el capitalismo es económicamente insostenible e incapaz de mejorar el nivel de vida de la población debido a su necesidad de compensar la caída de las tasas de ganancia mediante la reducción de los salarios de los empleados, los beneficios sociales y la búsqueda de agresiones militares. El modo de producción comunista sucedería al capitalismo como el nuevo modo de producción de la humanidad a través de la revolución de los trabajadores . Según la teoría marxista de la crisis , el comunismo no es una inevitabilidad sino una necesidad económica. [204]

Un concepto importante en el marxismo es la socialización, es decir, la propiedad social , versus la nacionalización . La nacionalización es la propiedad estatal , mientras que la socialización es el control y la gestión de la propiedad por parte de la sociedad. El marxismo considera esta última como su objetivo y considera la nacionalización como una cuestión táctica, ya que la propiedad estatal todavía está en el ámbito del modo de producción capitalista . En palabras de Friedrich Engels , "la transformación ... en propiedad estatal no elimina la naturaleza capitalista de las fuerzas productivas. ... La propiedad estatal de las fuerzas productivas no es la solución del conflicto, pero ocultas en ella están las condiciones técnicas que forman los elementos de esa solución". [b] Esto ha llevado a los grupos y tendencias marxistas críticos del modelo soviético a etiquetar a los estados basados en la nacionalización, como la Unión Soviética, como capitalistas de Estado , una visión que también comparten varios académicos. [48] [129] [131]

Sobre todo, establecerá una constitución democrática y, a través de ella, el dominio directo o indirecto del proletariado.

Mientras que los marxistas proponen reemplazar el Estado burgués por un semiestado proletario a través de la revolución ( dictadura del proletariado ), que eventualmente desaparecería, los anarquistas advierten que el Estado debe ser abolido junto con el capitalismo. No obstante, los resultados finales deseados, una sociedad comunal sin Estado , son los mismos. [216]

Karl Marx criticó al liberalismo por no ser lo suficientemente democrático y encontró que la situación social desigual de los trabajadores durante la Revolución Industrial socavó la capacidad democrática de los ciudadanos. [217] Los marxistas difieren en sus posiciones hacia la democracia. [218] [219]

Algunos sostienen que la toma de decisiones democrática coherente con el marxismo debería incluir la votación sobre cómo debe organizarse el trabajo excedente . [221]La controversia sobre el legado de Marx hoy gira en gran medida en torno a su ambigua relación con la democracia.

—Robert Meister [220]

Queremos lograr un nuevo y mejor orden social: en esta nueva y mejor sociedad no debe haber ni ricos ni pobres; todos tendrán que trabajar. No un puñado de ricos, sino todos los trabajadores deben disfrutar de los frutos de su trabajo común. Las máquinas y otros adelantos deben servir para facilitar el trabajo de todos y no para permitir que unos pocos se enriquezcan a costa de millones y decenas de millones de personas. Esta nueva y mejor sociedad se llama sociedad socialista. Las enseñanzas sobre esta sociedad se llaman "socialismo".

Vladimir Lenin, A los pobres del campo (1903) [222]

El leninismo es una ideología política desarrollada por el revolucionario marxista ruso Vladimir Lenin que propone el establecimiento de la dictadura del proletariado , dirigida por un partido revolucionario de vanguardia , como preludio político al establecimiento del comunismo. La función del partido de vanguardia leninista es proporcionar a las clases trabajadoras la conciencia política (educación y organización) y el liderazgo revolucionario necesarios para deponer al capitalismo en el Imperio ruso (1721-1917). [223]

La dirección revolucionaria leninista se basa en el Manifiesto Comunista (1848), que identifica al Partido Comunista como "la sección más avanzada y resuelta de los partidos de la clase obrera de cada país; la sección que impulsa a todos los demás". Como partido de vanguardia, los bolcheviques veían la historia a través del marco teórico del materialismo dialéctico , que sancionaba el compromiso político con el derrocamiento exitoso del capitalismo y luego con la institución del socialismo ; y como gobierno nacional revolucionario, para realizar la transición socioeconómica por todos los medios. [224] [ cita completa requerida ]

El marxismo-leninismo es una ideología política desarrollada por Iósif Stalin . [225] Según sus defensores, se basa en el marxismo y el leninismo . Describe la ideología política específica que Stalin implementó en el Partido Comunista de la Unión Soviética y a escala global en la Comintern . No hay un acuerdo definitivo entre los historiadores sobre si Stalin realmente siguió los principios de Marx y Lenin. [226] También contiene aspectos que según algunos son desviaciones del marxismo, como el socialismo en un solo país . [227] [228] El marxismo-leninismo fue la ideología oficial de los partidos comunistas del siglo XX (incluido el trotskista ), y se desarrolló después de la muerte de Lenin; sus tres principios eran el materialismo dialéctico , el papel dirigente del partido comunista a través del centralismo democrático y una economía planificada con industrialización y colectivización agrícola . El marxismo-leninismo es engañoso porque Marx y Lenin nunca aprobaron ni apoyaron la creación de un -ismo después de ellos, y es revelador porque, al ser popularizado después de la muerte de Lenin por Stalin, contenía esos tres principios doctrinales e institucionalizados que se convirtieron en un modelo para los regímenes posteriores de tipo soviético; su influencia global, habiendo cubierto en su apogeo al menos un tercio de la población mundial, ha hecho del marxismo-leninismo una etiqueta conveniente para el bloque comunista como un orden ideológico dinámico. [229] [c]

Durante la Guerra Fría, el marxismo-leninismo fue la ideología del movimiento comunista más claramente visible y es la ideología más prominente asociada con el comunismo. [181] [nota 8] El socialfascismo fue una teoría apoyada por el Comintern y los partidos comunistas afiliados durante la década de 1930, que sostenía que la socialdemocracia era una variante del fascismo porque se interponía en el camino de una dictadura del proletariado , además de un modelo económico corporativista compartido. [231] En ese momento, los líderes del Comintern, como Stalin y Rajani Palme Dutt , afirmaron que la sociedad capitalista había entrado en el Tercer Período en el que una revolución del proletariado era inminente pero podía ser prevenida por los socialdemócratas y otras fuerzas fascistas . [231] [232] El término socialfascista se usó peyorativamente para describir a los partidos socialdemócratas, anti-Comintern y partidos socialistas progresistas y disidentes dentro de los afiliados del Comintern durante el período de entreguerras . La teoría del fascismo social fue defendida enérgicamente por el Partido Comunista de Alemania , que estuvo en gran medida controlado y financiado por el liderazgo soviético desde 1928. [232]

Dentro del marxismo-leninismo, el antirrevisionismo es una postura que surgió en la década de 1950 en oposición a las reformas y al deshielo de Jruschov del líder soviético Nikita Jruschov . Mientras que Jruschov perseguía una interpretación que difería de la de Stalin, los antirrevisionistas dentro del movimiento comunista internacional se mantuvieron fieles al legado ideológico de Stalin y criticaron a la Unión Soviética bajo Jruschov y sus sucesores como capitalista de Estado y socialimperialista debido a sus esperanzas de lograr la paz con los Estados Unidos. El término estalinismo también se utiliza para describir estas posturas, pero a menudo no lo utilizan sus partidarios, que opinan que Stalin practicaba el marxismo y el leninismo ortodoxos. Debido a que las diferentes tendencias políticas rastrean las raíces históricas del revisionismo en diferentes épocas y líderes, hoy en día existe un desacuerdo significativo sobre lo que constituye el antirrevisionismo. Los grupos modernos que se describen a sí mismos como antirrevisionistas se dividen en varias categorías. Algunos defienden las obras de Stalin y Mao Zedong y otros las obras de Stalin, mientras que rechazan a Mao y tienden universalmente a oponerse al trotskismo . Otros rechazan tanto a Stalin como a Mao, y rastrean sus raíces ideológicas hasta Marx y Lenin. Además, otros grupos defienden a varios líderes históricos menos conocidos, como Enver Hoxha , quien también rompió con Mao durante la división chino-albanesa . [132] [133] El socialimperialismo fue un término utilizado por Mao para criticar a la Unión Soviética post-Stalin. Mao afirmó que la Unión Soviética se había convertido en una potencia imperialista mientras mantenía una fachada socialista . [233] Hoxha estuvo de acuerdo con Mao en este análisis, antes de usar más tarde la expresión para condenar también la teoría de los tres mundos de Mao . [234]

El estalinismo representa el estilo de gobierno de Stalin en oposición al marxismo-leninismo, el sistema socioeconómico y la ideología política implementada por Stalin en la Unión Soviética, y luego adaptada por otros estados basados en el modelo ideológico soviético , como la planificación central , la nacionalización y el estado de partido único, junto con la propiedad pública de los medios de producción , la industrialización acelerada , el desarrollo proactivo de las fuerzas productivas de la sociedad (investigación y desarrollo) y los recursos naturales nacionalizados . El marxismo-leninismo permaneció después de la desestalinización, mientras que el estalinismo no. En las últimas cartas antes de su muerte, Lenin advirtió sobre el peligro de la personalidad de Stalin e instó al gobierno soviético a reemplazarlo. [95] Hasta la muerte de Joseph Stalin en 1953, el Partido Comunista Soviético se refirió a su propia ideología como marxismo-leninismo-estalinismo . [177]

El marxismo-leninismo ha sido criticado por otras tendencias comunistas y marxistas, que afirman que los estados marxistas-leninistas no establecieron el socialismo sino más bien el capitalismo de Estado . [48] [129] [131] Según el marxismo, la dictadura del proletariado representa el gobierno de la mayoría (democracia) en lugar de un partido, hasta el punto de que el cofundador del marxismo, Friedrich Engels , describió su "forma específica" como la república democrática . [235] Según Engels, la propiedad estatal por sí misma es propiedad privada de naturaleza capitalista, [b] a menos que el proletariado tenga el control del poder político, en cuyo caso forma propiedad pública. [e] Si el proletariado estaba realmente en control de los estados marxistas-leninistas es un tema de debate entre el marxismo-leninismo y otras tendencias comunistas. Para estas tendencias, el marxismo-leninismo no es ni marxismo ni leninismo ni la unión de ambos, sino más bien un término artificial creado para justificar la distorsión ideológica de Stalin, [236] introducido a la fuerza en el Partido Comunista de la Unión Soviética y en la Comintern. En la Unión Soviética, esta lucha contra el marxismo-leninismo estuvo representada por el trotskismo , que se describe a sí mismo como una tendencia marxista y leninista. [237]

El trotskismo, desarrollado por León Trotsky en oposición al estalinismo , [238] es una tendencia marxista y leninista que apoya la teoría de la revolución permanente y la revolución mundial en lugar de la teoría de las dos etapas y el socialismo en un solo país de Stalin . Apoyó otra revolución comunista en la Unión Soviética y el internacionalismo proletario . [239]

En lugar de representar la dictadura del proletariado , Trotsky sostenía que la Unión Soviética se había convertido en un estado obrero degenerado bajo el liderazgo de Stalin en el que las relaciones de clase habían resurgido bajo una nueva forma. La política de Trotsky difería marcadamente de las de Stalin y Mao, sobre todo en que declaraba la necesidad de una revolución proletaria internacional –en lugar del socialismo en un solo país– y el apoyo a una verdadera dictadura del proletariado basada en principios democráticos. En su lucha contra Stalin por el poder en la Unión Soviética, Trotsky y sus partidarios se organizaron en la Oposición de Izquierda [240] , cuya plataforma se conocería como trotskismo [238] .

En particular, Trotsky abogó por una forma descentralizada de planificación económica , [241] la democratización soviética de masas , [242] la representación electa de los partidos socialistas soviéticos , [243] [244] la táctica de un frente unido contra los partidos de extrema derecha, [245] la autonomía cultural para los movimientos artísticos, [246] la colectivización voluntaria , [247] [248] un programa de transición [249] y el internacionalismo socialista . [250]

Trotsky tenía el apoyo de muchos intelectuales del partido , pero esto se vio eclipsado por el enorme aparato que incluía a la GPU y los cuadros del partido que estaban a disposición de Stalin. [251] Stalin finalmente logró obtener el control del régimen soviético y los intentos trotskistas de eliminar a Stalin del poder resultaron en el exilio de Trotsky de la Unión Soviética en 1929. Mientras estaba en el exilio, Trotsky continuó su campaña contra Stalin, fundando en 1938 la Cuarta Internacional , un rival trotskista del Comintern. [252] [253] [254] En agosto de 1940, Trotsky fue asesinado en la Ciudad de México por orden de Stalin. Las corrientes trotskistas incluyen el trotskismo ortodoxo , el tercer campo , el posadismo y el pablismo . [255] [256]

La plataforma económica de una economía planificada combinada con una auténtica democracia obrera, tal como la propugnó originalmente Trotsky, ha constituido el programa de la Cuarta Internacional y del movimiento trotskista moderno. [257]

El maoísmo es la teoría derivada de las enseñanzas del líder político chino Mao Zedong . Desarrollada desde la década de 1950 hasta la reforma económica china de Deng Xiaoping en la década de 1970, se aplicó ampliamente como la ideología política y militar rectora del Partido Comunista de China y como la teoría que guía los movimientos revolucionarios en todo el mundo. Una diferencia clave entre el maoísmo y otras formas de marxismo-leninismo es que los campesinos deben ser el baluarte de la energía revolucionaria que lidera la clase trabajadora. [258] Tres valores maoístas comunes son el populismo revolucionario , ser práctico y la dialéctica . [259]

La síntesis del marxismo-leninismo-maoísmo, [f] que se basa en las dos teorías individuales como la adaptación china del marxismo-leninismo, no ocurrió durante la vida de Mao. Después de la desestalinización , el marxismo-leninismo se mantuvo en la Unión Soviética , mientras que ciertas tendencias antirrevisionistas como el hoxhaísmo y el maoísmo afirmaron que se habían desviado de su concepto original. Se aplicaron diferentes políticas en Albania y China, que se distanciaron más de la Unión Soviética. A partir de la década de 1960, los grupos que se autodenominaban maoístas , o los que defendían el maoísmo, no estaban unificados en torno a una comprensión común del maoísmo, sino que tenían sus propias interpretaciones particulares de las obras políticas, filosóficas, económicas y militares de Mao. Sus partidarios afirman que, como etapa superior unificada y coherente del marxismo, no se consolidó hasta la década de 1980, siendo formalizado por primera vez por Sendero Luminoso en 1982. [260] A través de la experiencia de la guerra popular librada por el partido, Sendero Luminoso pudo postular al maoísmo como el desarrollo más nuevo del marxismo. [260]

El eurocomunismo fue una tendencia revisionista de los años 1970 y 1980 dentro de varios partidos comunistas de Europa occidental, que afirmaban desarrollar una teoría y una práctica de transformación social más relevantes para su región. Especialmente prominente dentro del Partido Comunista Francés , el Partido Comunista Italiano y el Partido Comunista de España , los comunistas de esta naturaleza buscaron socavar la influencia de la Unión Soviética y su Partido Comunista de toda la Unión (bolcheviques) durante la Guerra Fría . [162] Los eurocomunistas tendían a tener un mayor apego a la libertad y la democracia que sus contrapartes marxistas-leninistas. [261] Enrico Berlinguer , secretario general del principal partido comunista de Italia, fue ampliamente considerado el padre del eurocomunismo. [262]

El marxismo libertario es una amplia gama de filosofías económicas y políticas que enfatizan los aspectos antiautoritarios del marxismo . Las primeras corrientes del marxismo libertario, conocidas como comunismo de izquierda , [263] surgieron en oposición al marxismo-leninismo [264] y sus derivados como el estalinismo y el maoísmo , así como el trotskismo . [265] El marxismo libertario también es crítico de las posiciones reformistas como las sostenidas por los socialdemócratas . [266] Las corrientes marxistas libertarias a menudo se basan en las obras posteriores de Marx y Engels, específicamente los Grundrisse y La guerra civil en Francia , [267] enfatizando la creencia marxista en la capacidad de la clase trabajadora para forjar su propio destino sin la necesidad de un partido revolucionario o estado que medie o ayude a su liberación. [268] Junto con el anarquismo , el marxismo libertario es uno de los principales derivados del socialismo libertario . [269]

Además del comunismo de izquierda, el marxismo libertario incluye corrientes como el autonomismo , la comunización , el comunismo de consejos , el deleonismo , la tendencia Johnson-Forest , el letrismo , el situacionismo luxemburguista , el socialismo o barbarie , Solidaridad , el Movimiento Socialista Mundial y el obrerismo , así como partes del freudomarxismo y la Nueva Izquierda . [270] Además, el marxismo libertario a menudo ha tenido una fuerte influencia tanto en los anarquistas posizquierdistas como en los sociales . Entre los teóricos notables del marxismo libertario se incluyen Antonie Pannekoek , Raya Dunayevskaya , Cornelius Castoriadis , Maurice Brinton , Daniel Guérin y Yanis Varoufakis , [271] este último afirma que el propio Marx era un marxista libertario. [272]

El comunismo de consejos es un movimiento que se originó en Alemania y los Países Bajos en la década de 1920, [273] cuya organización principal fue el Partido Comunista de los Trabajadores de Alemania . Continúa hoy como una posición teórica y activista tanto dentro del marxismo libertario como del socialismo libertario . [274] El principio central del comunismo de consejos es que el gobierno y la economía deben ser administrados por consejos de trabajadores , que están compuestos por delegados elegidos en los lugares de trabajo y revocables en cualquier momento. Los comunistas de consejos se oponen a la naturaleza autoritaria y antidemocrática percibida de la planificación central y del socialismo de estado , etiquetado como capitalismo de estado , y a la idea de un partido revolucionario, [275] [276] ya que los comunistas de consejos creen que una revolución liderada por un partido necesariamente produciría una dictadura de partido . Los comunistas de consejos apoyan una democracia obrera, producida a través de una federación de consejos de trabajadores.

A diferencia de la socialdemocracia y el comunismo leninista , el argumento central del comunismo de consejos es que los consejos obreros democráticos que surgen en las fábricas y municipios son las formas naturales de las organizaciones de la clase obrera y del poder gubernamental. [277] [278] Esta visión se opone tanto a las ideologías reformistas [279] como a las comunistas leninistas [275] , que enfatizan respectivamente el gobierno parlamentario e institucional mediante la aplicación de reformas sociales por un lado, y los partidos de vanguardia y el centralismo democrático participativo por el otro. [279] [275]

El comunismo de izquierda es el conjunto de puntos de vista comunistas sostenidos por la izquierda comunista, que critica las ideas y prácticas políticas defendidas, en particular tras la serie de revoluciones que pusieron fin a la Primera Guerra Mundial por los bolcheviques y los socialdemócratas . [280] Los comunistas de izquierda afirman posiciones que consideran más auténticamente marxistas y proletarias que las opiniones del marxismo-leninismo defendidas por la Internacional Comunista después de su primer congreso (marzo de 1919) y durante su segundo congreso (julio-agosto de 1920). [264] [281] [282]

Los comunistas de izquierda representan una gama de movimientos políticos distintos de los marxistas-leninistas , a quienes en gran medida consideran simplemente el ala izquierda del capital , de los anarcocomunistas , algunos de los cuales consideran socialistas internacionalistas , y de varias otras tendencias socialistas revolucionarias, como los deleonistas , a quienes tienden a ver como socialistas internacionalistas solo en casos limitados. [283] El bordiguismo es una corriente comunista de izquierda leninista que lleva el nombre de Amadeo Bordiga , quien ha sido descrito como "más leninista que Lenin", y se consideraba leninista. [284]

El anarcocomunismo es una teoría libertaria del anarquismo y el comunismo que aboga por la abolición del Estado , la propiedad privada y el capitalismo en favor de la propiedad común de los medios de producción ; [285] [286] la democracia directa ; y una red horizontal de asociaciones voluntarias y consejos de trabajadores con producción y consumo basados en el principio rector, " De cada uno según su capacidad, a cada uno según su necesidad ". [287] [288] El anarcocomunismo se diferencia del marxismo en que rechaza su visión sobre la necesidad de una fase de socialismo de estado previa al establecimiento del comunismo. Peter Kropotkin , el principal teórico del anarcocomunismo, afirmó que una sociedad revolucionaria debería "transformarse inmediatamente en una sociedad comunista", que debería pasar inmediatamente a lo que Marx había considerado como la "fase más avanzada, completa, del comunismo". [289] De esta manera, se intenta evitar la reaparición de las divisiones de clase y la necesidad de que un Estado esté en control. [289]

Algunas formas de anarcocomunismo, como el anarquismo insurreccional , son egoístas y están fuertemente influenciadas por el individualismo radical , [290] [291] [292] creyendo que el comunismo anarquista no requiere de una naturaleza comunitaria en absoluto. La mayoría de los anarcocomunistas ven el comunismo anarquista como una forma de reconciliar la oposición entre el individuo y la sociedad. [g] [293] [294]

El comunismo cristiano es una teoría teológica y política basada en la visión de que las enseñanzas de Jesucristo obligan a los cristianos a apoyar el comunismo religioso como el sistema social ideal . [53] Aunque no hay un acuerdo universal sobre las fechas exactas en que comenzaron las ideas y prácticas comunistas en el cristianismo, muchos comunistas cristianos afirman que la evidencia de la Biblia sugiere que los primeros cristianos, incluidos los apóstoles en el Nuevo Testamento , establecieron su propia pequeña sociedad comunista en los años posteriores a la muerte y resurrección de Jesús. [295]

Muchos defensores del comunismo cristiano afirman que fue enseñado por Jesús y practicado por los mismos apóstoles, [296] un argumento con el que los historiadores y otros, incluido el antropólogo Roman A. Montero, [297] eruditos como Ernest Renan , [298] [299] y teólogos como Charles Ellicott y Donald Guthrie , [300] [301] generalmente están de acuerdo. [53] [302] El comunismo cristiano goza de cierto apoyo en Rusia. El músico ruso Yegor Letov era un comunista cristiano declarado, y en una entrevista de 1995 fue citado diciendo: "El comunismo es el Reino de Dios en la Tierra". [303]

Emily Morris, del University College de Londres, escribió que debido a que los escritos de Karl Marx han inspirado muchos movimientos, incluida la Revolución rusa de 1917 , el comunismo "comúnmente se confunde con el sistema político y económico que se desarrolló en la Unión Soviética" después de la revolución. [72] [h] Morris también escribió que el comunismo de estilo soviético "no 'funcionó'" debido a "un sistema económico y político demasiado centralizado, opresivo, burocrático y rígido". [72] El historiador Andrzej Paczkowski resumió el comunismo como "una ideología que parecía claramente lo opuesto, que se basaba en el deseo secular de la humanidad de lograr la igualdad y la justicia social, y que prometía un gran salto hacia la libertad". [60] En contraste, el economista austro-estadounidense Ludwig von Mises argumentó que al abolir los mercados libres, los funcionarios comunistas no tendrían el sistema de precios necesario para guiar su producción planificada. [304]