¡Hola Mundo!

Mi interés en editar Wikipedia es la ilustración, así que déjame saber si deseas que se ilustre algún artículo sobre ciencia , tecnología , arquitectura o matemáticas . A continuación, se muestran algunos de mis trabajos hasta la fecha...

Después de un paseo en bote, les pregunté a mis invitados el clásico acertijo sobre los botes del Trinity College:

¿Qué concepto tienen todos los nombres en común?

(La respuesta está en Trinity College, Cambridge#Punt_names .)

De vuelta a casa, me sorprendió saber que no se mencionaba en el artículo , así que escribí una sección (por suerte, su nuevo barco, Charles , apareció en las noticias) y salí a hacer una sesión de fotos. Debí de tener un aspecto extraño al fotografiar solo los nombres a propósito.

Acertijo adicional: ¿Puedes decir cómo se relaciona cada nombre en la imagen con el concepto?

Como las imágenes híbridas me han cautivado durante años, me encantó encontrar una herramienta de inteligencia artificial que genera imágenes híbridas con una imagen inicial para la versión distante y un mensaje de texto para la versión cercana:

http://huggingface.co/spaces/AP123/IllusionDiffusion

Funciona mejor con caras reconocibles en alto contraste sobre un fondo simple.

Primero experimenté con imágenes famosas de Abraham Lincoln y el Che Guevara en escenas apropiadas antes de decidir que la Mona Lisa era la más relevante y reconocible a nivel internacional. También fue una suerte que la consigna "fotografía en color de una ciudad italiana en el Renacimiento" diera como resultado un paisaje ficticio estéticamente agradable. Para que el rostro se viera mejor, superpuse una copia tenue de la imagen de la semilla y retoqué manualmente los defectos.

Mi próximo paso podría ser encontrar un texto de Leonardo da Vinci , eliminar los espacios en blanco, reducir su tamaño y superponerlo en la imagen para crear tres niveles híbridos. ¿Alguna sugerencia sobre cómo crear cuatro niveles?

ACTUALIZACIÓN 24-09-2024: Hice una imagen híbrida con La joven de la perla de Vermeer .

Recientemente aprendí acerca de dos plantillas de tabla muy útiles:

Una limitación importante es que las tablas con varias filas de encabezado también deben tener activada la ordenación. Es una pena que no se puedan alinear los puntos decimales.

A modo de ejemplo, intente desplazarse por la página mientras observa la tabla de http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet a continuación.

Miserly-me quería introducir nuevos juegos a mi grupo de juegos de mesa, pero los juegos actuales son muy costosos.

Un amigo me contó sobre los juegos de imprimir y jugar (PnP) y se me ocurrió imprimirlos e insertarlos con naipes viejos en fundas para cartas de póquer de 64 mm × 89 mm.

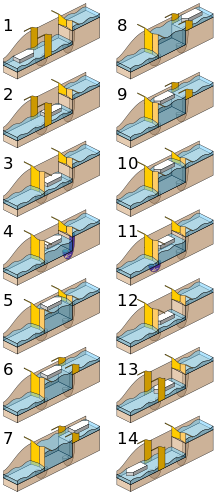

Aunque Sprawlopolis y Air, Land and Sea fueron divertidos, Palm Island fue mi favorito. Como no había mucho texto en las tarjetas, pensé que podía hacer un PDF A4 de una versión isomórfica con fondos de dominio público (para evitar problemas de derechos de autor) para ilustrar Wikipedia. Lo llamé Balmy Isle .

En lugar de utilizar software de diseño como LibreOffice Draw , decidí codificar cada página en SVG para poder instanciar programáticamente partes repetidas para lograr coherencia.

Como tenía pensado imprimir cada página en papel normal e insertar una tarjeta entre la parte delantera y la trasera, hice que las dos filas superiores se doblaran. Es una pena que el diseño de 3x3 impidiera este tratamiento en las filas inferiores. Una versión A2 con tarjetas de 6x6 lo permitiría.

Aunque librsvg no reconoció algunos de los emojis utilizados, siempre que aparecieran en mi navegador, pude imprimir cada página en formato PDF. Como no pude encontrar una forma de crear varias páginas al imprimir, incorporé un interruptor para seleccionar qué página mostrar. Al fusionar y optimizar las copias digitales, obtuve el archivo cargado.

commons:user:Emreszer se puso en contacto conmigo para traducir mi mapa delta-v al turco y aproveché la oportunidad para agregar mapas de bits al diagrama.

Las fotografías de los objetos celestes que encontré tenían fondos negros, lo que me pareció desagradable a la vista contra el fondo blanco del gráfico, así que modifiqué la animación de rotación de los planetas para que no giraran, pero tuvieran el efecto esférico. También agregué otros objetos, restauré el aplanamiento que no se ve bien en la animación SVG, lo cargué en Firefox, tomé una captura de pantalla, la modifiqué hasta obtener un tamaño adecuado y la incrusté en el archivo SVG, que recorta cada objeto y lo coloca en el lugar apropiado.

Creo que esto hace que sea más fácil localizar los objetos y hace que el cartel sea atractivo, ¿no crees? 😊

En 2011, encontré artículos sobre puntos estacionarios , puntos de inflexión , etc. que carecían de diagramas que mostraran cómo se relacionaban entre sí los gráficos de las derivadas subsiguientes de una función cúbica. Para mi ilustración, quería una función cuyos puntos especiales tuvieran coordenadas enteras distintas y cuyos valores especiales no fueran cero.

Con la ayuda de Álvaro Lozano-Robledo, encontré una familia de funciones con la gráfica más "pequeña". Aun así, los valores de y son mucho mayores que los de x . Para conseguir una visualización razonable, tuve que hacer la escala vertical 50 veces mayor que la horizontal.

Fue un tema de discordia durante 12 años hasta que me di cuenta este año de que podía relajar una condición y también mostrar el efecto de una raíz repetida. Usando un script de Python , encontré una función "pequeña" que satisfacía mis objetivos: (también es interesante que las distintas raíces sean 1, 2, 3 y 4).

Para solucionar el error T97233 de rsvg, decidí utilizar caracteres Unicode prediseñados para las variables (en cursiva) y los superíndices. Al proporcionar la factorización de cada función, también se muestra cómo se derivan sus raíces.

Gracias también a GalacticShoe por un algoritmo para dibujar exactamente un segmento polinomial cúbico con una curva Bézier cúbica :

Si y los puntos finales son , , los puntos de control son

¿Alguien puede mejorar la función o presentación?

Me encontré con las magníficas fotografías de Penang tomadas con drones por HundenvonPenang y le pedí una foto del abandonado Penang Mutiara Beach Resort y de la recientemente inaugurada Gurney Bay . Me atendió y también me sugirió que nos reuniéramos porque estaba de visita en Penang.

*angys* se unió a la conversación y decidimos encontrarnos en Chap Goh Meh . Caminamos por George Town en un recorrido fotográfico de la procesión de Tua Pek Kong y el lanzamiento de naranjas en la Explanada. Fue maravilloso conocer a estos dos amables y diligentes wikipedistas.

También me pusieron en contacto con un grupo local encabezado por Ultron90 y ayudé a organizar su evento WikiGap hoy. Como el tema es sobre las mujeres en Malasia, decidí empezar un artículo sobre la eminente geógrafa y activista medioambiental Dra. Kam Suan Pheng . ¡Echa un vistazo a su artículo !

Me encontré con una idea ingeniosa de TilmannR para generar un SVG estático a partir de uno con JavaScript, lo que permite a los ilustradores crear diseños o gráficos demasiado complejos para crearlos manualmente. Si bien anteriormente había generado SVG con Python y Perl, una gran ventaja del método de TilmannR es que los editores solo necesitan un editor de texto y un navegador web para regenerar el SVG para subirlo a Commons, lo que no permite la ejecución de ningún script.

Le sugerí a TilmannR que incrustara el script como comentario en el SVG mismo, de modo que la fuente nunca se separara del archivo. Finalmente, se nos ocurrió reemplazar

que produce un SVG válido, pasa el filtro de Commons y, sin embargo, permite restaurar fácilmente el script eliminando "!--" y "--". Una desventaja es que el script no puede contener --(por suerte, esto se puede solucionar a menudo -= 1en JavaScript). El script vuelca en un grupo SVG con id GENERATED_CONTENTel contenido generado y en uno con id GENERATOR_SCRIPTel script comentado.

Mi primer intento, File:Gabriel_horn_2d.svg, fue un éxito. TilmannR lo revisó amablemente y recomendó las mejores prácticas de JavaScript.

Luego intenté rehacer el archivo File:Template_map_of_U.S._states_and_District_of_Columbia.svg , que depende de mi cuenta de Google para ejecutar una hoja de cálculo de Google Sheets. Después de consultar Timeshifter , trasladé sus funciones al archivo File:Template_map_of_US_states_and_District_of_Columbia.svg mencionado anteriormente. Si bien puede llevar un tiempo documentar su uso, espero haber comentado el código con suficiente claridad para que terceros generen su propio mapa coroplético de los estados de EE. UU. y Washington DC.

En las últimas horas de 2023, decidí implementar una idea que había visto en http://jsfiddle.net/elin/7m3bL hace años. Descubrí que su autor, Eddie Lin, había usado mucho las sombras de caja CSS y me pregunté si podía hacer algo similar con las rutas en SVG.

Hay dos series de fuegos artificiales funcionando simultáneamente, y se genera uno nuevo tan pronto como termina el anterior. Tener dos ofrece el mejor equilibrio entre rendimiento y hacer que la escena sea más animada.

Cada conjunto de fuegos artificiales tiene dos animaciones:

Para cada explosión, la escala simula las partículas en expansión mientras que la traducción simula la gravedad, haciendo que la facilidad se acelere a través de su ciclo. El color comienza con blanco puro para simular altas temperaturas, transformándose en el color deseado. stroke_width comienza en 9999, combinado con la escala creciente y el color blanco que simula el destello de cada explosión, y disminuye a cero para simular partículas en descomposición.

La posición salta a uno de los diez puntos (el centro más un cuadrado mágico de 3x3) al comienzo de cada explosión. dasharray determina el espaciado de las partículas a lo largo de las trayectorias dadas, simulando cierta aleatoriedad en el movimiento de las partículas. Para la última explosión de una secuencia, aumentar rápidamente el espaciado simula un efecto de "pez volador".

Cada camino constaba inicialmente de tres elipses que se entrecruzaban. En la última subida, me di cuenta de que podía preescalar los caminos para variar el tamaño de las partículas. Para variar, también reemplacé uno de los caminos con dos estrellas que se entrecruzaban a diferentes escalas.

¡Las subidas de Pity Commons no pueden tener sonido, por lo que tendrás que disfrutar del espectáculo en silencio!

Hasta el próximo post... Feliz año nuevo!

Pensé en probar suerte con la pintura digital y me compré una tableta gráfica XP-PEN en una oferta del Prime Day .

Mientras visitábamos un castillo, un amigo y yo observamos que la escalera helicoidal (de caracol) que conducía al sótano giraba de una manera poco convencional. Un "dato curioso" me recordó que este tipo de escaleras suelen girar de manera que el poste dificulta que los invasores, que suelen ser diestros, puedan blandir un arma. Me pregunté si esta escalera en particular era diferente porque la entrada estaba por encima de la habitación y, por lo tanto, los invasores tendrían que bajar.

Sin embargo, decidí dibujar la disposición típica después de descubrir que en Wikipedia no había una imagen de ese tipo. Lamentablemente, más tarde me enteré de que ese "dato" era un mito. Aun así, aprender a pintar en Krita fue una buena experiencia.

Hace muchos años, unos amigos y yo compartimos un huevo escocés en un picnic. Uno de nosotros se acordó del problema del sándwich de jamón y reflexionó sobre cómo cortarlo de modo que cada mitad tuviera la misma cantidad de clara, yema y masa. Pensamos equivocadamente que podíamos encontrar el plano que contenía el centro de gravedad de cada componente antes de darnos cuenta de que el centro de gravedad nos daría la media en lugar de la mediana, ya que la media pondera cada partícula según la distancia desde el centro de gravedad.

En casa, escribí un script en Python para ver cómo las líneas en diferentes ángulos dividían una forma bidimensional arbitraria en dos áreas iguales. Con OpenCV, leyó las imágenes como mapas de bits de 1 bit y contó la cantidad de píxeles negros.

Para cada ángulo, llené completamente de blanco un lado de la línea y conté los píxeles negros restantes. Al mover progresivamente la línea con la búsqueda binaria hasta que quedaran aproximadamente la mitad de los píxeles negros, obtuve la bisectriz de ese ángulo.

Al repetir esto cada 5 grados en distintas formas se obtuvieron lugares interesantes con un número impar de cúspides, incluso para formas con partes no contiguas.

Mucho más recientemente, pensé que el artículo sobre el teorema del sándwich de jamón podría funcionar con una ilustración en 2D, así que adapté el guión para que funcionara con dos colores. Elegí un mapa de las Islas Británicas porque estaba dividido convenientemente en dos países (principales), uno de los cuales tenía dos partes significativas.

La salida de Irlanda y el Reino Unido se colocó en los canales rojo, azul y verde, respectivamente, de modo que Irlanda apareciera en verde y el Reino Unido en rosa. La bisectriz común se destacó en negro.

Aunque conocía el conjunto de Cantor desde hacía muchos años, me intrigó su representación radial en http://gist.github.com/curran/74cb4d255acf072633a2df0d9b9be7c3 y traté de recrearla.

La primera fila de la versión lineal habitual se convierte en un círculo, en realidad un anillo con un radio interior cero, ya que abarca los 360°. Las filas siguientes se convierten en anillos rotos que crecen hacia afuera. Diferentes tonos de gris distinguen los anillos. El hecho de que cada anillo comience y termine en la parte inferior de la figura hace que parezca un pájaro estilizado.

El SVG fue generado por un script de Python que genera el conjunto de Cantor como una lista anidada y dibuja los anillos (excepto el más interno) usando stroke-dasharray, sus valores finales incrementados para evitar espacios debido al redondeo.

¿Crees que la figura sería un buen logotipo para una sociedad de matemáticas?

Chris25689 me recordó amablemente que actualizara mi diagrama de la Pirámide del Tiempo , ya que hoy ocurrió un evento que ocurre una vez cada década.

Hace diez años, ya había colocado el bloque 2023 en el SVG, pero lo comenté, por lo que creí que era una cuestión sencilla de descomentarlo. Desafortunadamente, el texto se desbordó, por lo que tuve que ajustar el viewBox . Bueno, valió la pena intentarlo...

Imaginemos que tenemos 4 frutas de cada tipo. Las vamos a colocar en un cuadrado de 4x4 de manera que cada fila y columna tenga exactamente una de cada una. Este tipo de cuadrado se denomina cuadrado latino . Podemos añadir el requisito de que las diagonales también tengan una de cada una. Para lograrlo, se debe reflejar un patrón diferente en ambas direcciones. Esto se denomina cuadrado latino con diagonales completas.

Podríamos sustituir cada fruta por un número. Como cada fila, columna y diagonal tiene un número de cada uno, la suma de cada uno es obviamente la misma.

Los cuadrados mágicos normalmente tienen números diferentes, pero hay una forma ingeniosa de convertir nuestro cuadrado latino en uno. Primero, sustituyamos la fruta por los números del 0 al 3. Podemos copiar el cuadrado con los números multiplicados por 4. Refleje el cuadrado en una diagonal y añádalo al primero. Al sumar uno, los números comienzan desde uno.

Podemos utilizar este método para hacer cuadrados mágicos similares a uno del famoso matemático Srinivasa Ramanujan , que tenía su cumpleaños, el 22 de diciembre de 1887, en la fila superior.

Al dividir una fecha, como lo hizo él, en día, mes, siglo y año, podemos sustituir el día menos uno, etc. Estos se eligen de modo que cuando se suman los cuadrados, la fila superior es simplemente el día, mes, siglo y año.

Ahora tenemos un método para generar un cuadrado mágico para cualquier fecha. Por supuesto, si, por ejemplo, el mes es enero o febrero, obtenemos valores negativos. Algunos números también pueden repetirse, pero, en caso contrario, el cuadrado tiene otras propiedades de cuadrado mágico.

Desafortunadamente, no podemos hacer cuadrados mágicos de fechas de 3 por 3 de esta manera, ya que solo hay un cuadrado latino de 3 por 3, ignorando la rotación y la reflexión, y una de sus diagonales tiene el mismo número repetido.

Hace diez años le planteé a @Timwi un problema práctico :

Lo resolvió en poco tiempo, hice el gráfico y pasamos a otras cosas.

Hace unos meses, @Pruthviraya afirmó que él o ella y sus hijas lograron que cada color tuviera exactamente 22 constelaciones, siendo 88 casualmente un múltiplo de cuatro. Sin embargo, descubrí que su sugerencia hace que dos regiones adyacentes tengan el mismo color, ya que la trama se envuelve alrededor de los lados.

Busqué a Timwi nuevamente con la nueva restricción y esta vez la resolvió con un programa en C♯ (detalles en commons:File_talk:constellations,_equirectangular_plot.svg). Después de actualizar el script de Perl, volví a generar el SVG anterior con este intérprete de Perl en línea que permite la entrada y salida de archivos.

Es maravilloso reencontrarse con viejos amigos y volver a tratar viejos y divertidos problemas. ¡Gracias, Timwi !

Dejando atrás POV-Ray , comencé a renderizar animaciones usando Blender 3.3.1 .

Su simulación física resultó muy útil para esta animación GIF de esférico rodante . De lo contrario, habría sido una tarea ardua configurar fotogramas clave para modelar el curioso movimiento rodante. Sin embargo, me decepcionó que la animación comience lentamente y se acelere con el tiempo. Tal vez debería haberla dejado funcionar hasta que alcanzara un estado estable antes de "grabar" la acción.

Para la animación de la paradoja de rotación de la moneda , intenté usar un mapeo normal para hacer que la iluminación fuera más realista, pero como el mapa de textura ya tenía una iluminación fuerte aplicada, el efecto no fue el esperado.

Un problema con el uso de Blender es que la fuente no es texto y .blendlos archivos no están permitidos en Commons. Por lo tanto, no pude cargar la fuente para que los editores futuros trabajaran en ella. Como solución alternativa, codifiqué el .blendarchivo con Base64 y lo cargué en una página de discusión. ¿Conoce una mejor solución?

Me cautivó un truco en Britain's Got Talent (temporada 14): el actor lo llamó "péndulo armónico" y lo encontré por su nombre habitual: "onda de péndulo". Me sorprendió encontrar la Wikipedia en inglés sin un artículo, así que me propuse crear uno.

La animación SVG con CSS es un medio ideal para ilustrar el movimiento, por lo que hice algunas versiones, incluida una con frecuencias en proporciones de números primos sugeridas por @Jpgordon : aunque demuestra una agrupación inesperada, el patrón no es tan sorprendente como el original .

Utilicé la idea de la línea de tiempo para visualizar espacialmente la agrupación en el original. Es fascinante cómo el orden surge del caos en determinados momentos:

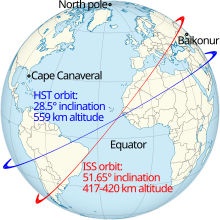

Luego pensé en el truco que utilicé en Archivo:Comparison_satellite_navigation_orbits.svg para agregar un reloj a la animación para mostrar en qué parte del ciclo ocurre la agrupación.

En cuanto al código, la animación utiliza la misma técnica de transformación de fotogramas clave que suelo emplear en SVG animados, pero con movimientos suaves de entrada y salida y alternancia para imitar el movimiento. Aunque no se trata exactamente de un movimiento armónico simple , los movimientos suaves de entrada y salida modelan los péndulos lo suficientemente bien.

El siguiente paso es construir aparatos físicos con pateadores electromagnéticos para que los péndulos oscilen indefinidamente. Aunque no creo que haga el mío con balas de cañón en llamas 😅

Me encontré con este archivo de 15 MB en commons:Category:Large_SVG_files y pensé que podría optimizarse mucho más en tamaño, así que me comuniqué con Sarang , un experto en minimizar SVG que me enseñó a hackear stroke-dasharray .

Mrmw lo redujo a unos 22 KB mucho más razonables. Pensé que se podía reducir aún más, ya que eran solo una colección de 61 elipses. Al comprender su construcción, hice exactamente eso y lo reduje a 7 KB.

Luego decidí usar un truco que uso para aproximar elipses a cualquier precisión requerida usando el comando de ruta de arco , por ejemplo

<ruta d= "M 0,3 a 4,3 0 1 0 0.1,0" /> es casi equivalente a

<elipse cx= "0" cy= "0" rx= "4" ry= "3" /> 0,1 se puede reducir arbitrariamente para aumentar la precisión, pero debe ser distinto de cero.

Sin embargo, para este diagrama, la mayoría de las elipse están rotadas, por lo que tuve que usar el parámetro de rotación y calcular uno de los puntos extremos en dirección x o y (para lo cual una tangente a la elipse es vertical u horizontal).

Como había escrito el código Python para hacer todo eso, decidí iterar a través de diferentes desplazamientos x e y para el centroide y ajustar el viewBox en consecuencia para minimizar el tamaño del archivo SVG. Aunque podría haber usado el descenso de gradiente, el espacio de búsqueda era lo suficientemente pequeño como para forzar la solución.

Me complació reducir el tamaño del archivo a 1901 bytes, el 0,01% del original, en general un desafío divertido en Code Golf ⛳

El miniproyecto de este mes comenzó con el llamado de Timeshifter al Laboratorio de Gráficos (posteriormente trasladado ) para encontrar una forma sencilla de generar un mapa coroplético de los estados de EE. UU. y DC.

Shyamal y yo propusimos varios enfoques. Me decidí por crear un SVG editable por humanos, complementado con una hoja de cálculo de Google Docs.

El método aprovecha el manejo de la opacidad de los elementos de SVG para realizar una interpolación lineal del color de cada elemento:

Supongamos que se desea tener un color que se encuentre en un 40 % del camino entre el naranja (que indica el valor mínimo) y el cian (que indica el valor máximo). Se puede dibujar el elemento en naranja con una opacidad del 100 % y, luego, el elemento nuevamente en cian con una opacidad del 40 %. En caso de que falten datos para algunos estados, primero se puede dibujar todo el mapa en gris y omitir los dos elementos anteriores para los estados en los que falten datos.

Para que la edición sea lo más sencilla posible, agregué una hoja de estilos para cambiar fácilmente los colores y los elementos de texto de diversas etiquetas que se usarán en la lógica comercial, y estructuré las partes editables por el usuario de la siguiente manera:

<style type= "text/css" > <!-- Los colores mínimos, máximos y los datos no disponibles se detallan a continuación -->

.min { fill:#ff6600; } .max { relleno:#99ffff; }.n_a { fill:#cccccc; } </style> <g id= "overlay" > <!-- Valor relativo de 0,00 (mín.) a 1,00 (máx.) y las cadenas de texto se dan a continuación; reemplace el valor href con "#XXX" si los datos no están disponibles --> <use xlink:href= "#AL2" fill-opacity= "0,185" /><text id= "AL" > 7,25 </text> <use xlink:href= "#AK2" fill-opacity= "0,502" /><text id= "AK" > 10,85 </text> ... <use xlink:href= "#WY2" fill-opacity= "0.000" /><text id= "WY" > 5,15 </text> <text id= "legend_min" > 5,15 </text> <text id= "legend_max" > 16,50 </text> <text id= "title" > Salarios mínimos estatales , en dólares. 1 de enero de 2023 </text> Todo esto fue empaquetado como Archivo:Plantilla de mapa de los estados de EE. UU. y el Distrito de Columbia.svg con estadísticas de urbanización como ejemplo de caso de uso.

Lo que quedaba era generar las opacidades adecuadas. Para ello, decidí utilizar Google Docs, ya que las hojas de cálculo son más conocidas para los profanos que Python y se pueden compartir fácilmente en línea. Timesplitter podía pegar los datos en https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1qBwH0oA5IklYobs-igbVc0k-WsoxWPSbG0cgmGEZeys/edit y copiar y pegar el código generado en el archivo SVG en Notepad++.

Después de mucho ir y venir, el producto final es el que se muestra arriba. Es hora de pasar a otra cosa...

Conseguí una placa base clonada de Lego y muchas placas 1×1 del mismo color, y pensé en hacer un mosaico de Lego. Como el tamaño estaba limitado a 50×50 piezas (en realidad 48×48, para dejar un borde de 1 píxel), la resolución es extremadamente limitada. Peor aún, tener un solo color significaba solo un bit de color.

Partiendo de una resolución de 16×16 e inspirado por el usuario de DeviantArt Erminest-DA , logré hacer una representación decente del personaje de anime de la izquierda. Para agregar una historia a la obra de arte, agregué la cita inspiradora compuesta por palabras de solo 2 letras: "Si tiene que ser, depende de mí (hacerlo)". Decidí que la cursiva lo haría más dinámico. Pensar en una fuente con esta resolución fue un buen desafío. Por último, la adición de una espada y un dragón ilustró visualmente la cita.

ACTUALIZACIÓN 8 DE MARZO DE 2023: En este hilo, TilmannR presentó una forma de usar la interpolación del vecino más cercano: envolver una imagen (con tamaño en píxeles en lugar de thumb) de la siguiente manera:

<div style= "image-rendering:pixelated;" > [[Archivo:50x50x1b.png|100px]] </div> Hace tiempo que siento curiosidad por los rompecabezas de desaparición . Como Wikipedia no tiene ningún artículo al respecto, después de reunir suficiente material, decidí convertirlo en un miniproyecto para la semana de Navidad.

La naturaleza de estos rompecabezas me permitió usar el truco del mouse over que descubrí para hacer SVG interactivos , como en el ejemplo de El ciclista que desaparece.

Aunque sé cómo funciona, todavía no he encontrado una fuente fiable que lo explique. Si alguien tiene alguna referencia, por favor háganmelo saber .

PD: Algo relacionado, también encontré una manera de explicar de manera más sencilla el rompecabezas del cuadrado faltante :

¡Simplemente utilice proporciones de Fibonacci más pequeñas: 1:2 y 2:3 !

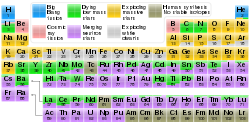

Me llevé una grata sorpresa al recibir un mensaje en el que me solicitaban una versión imprimible de mi infame tabla periódica de la nucleosíntesis.svg. El lector, que se hacía llamar Henk, aparentemente enseñaba física y quería un póster para colgar en su aula.

Honrado, decidí actualizar la descripción en commons:file:Nucleosynthesis_periodic_table.svg y formatearla bien debajo de la tabla periódica, también para hacer que la relación de aspecto sea más común para adaptarse a los tamaños de papel internacionales ISO 216 .

Para hacerlo, modifiqué el código SVG, lo abrí en Firefox, usé Imprimir > Microsoft Print to PDF y lo reduje con http://ilovepdf.com/compress_pdf usando "compresión extrema".

(Esto lo convierte en el segundo PDF que he subido a Commons, después de commons:file:Wikimania_2016_Dynamic_SVG_for_Wikimedia_projects.pdf – ¡en realidad una copia de seguridad de mi presentación de Wikimania 2016, en caso de que mi computadora portátil se estropee ! )

El mes pasado ocurrió algo curioso. Los aficionados a Among Us se enteraron de repente del diagrama con temática de parodia de Among Us que hice para ilustrar el teorema de Bayes , lo que dio lugar a una guerra de ediciones y una larga discusión .

De hecho, creo que el ejemplo de la probabilidad de que el personaje de un jugador sea un asesino dada su desconfianza es un uso magnífico y accesible del teorema, en comparación con las pruebas médicas.

El otro problema que se planteó fue que los íconos violaban los derechos de autor. No soy un experto en derechos de autor, pero al examinarlos en detalle con un miembro de la tripulación en el juego se observan diferencias intencionales. También evité cualquier terminología específica del juego.

Afortunadamente, el furor se calmó después de que la comunidad votó para mantener la imagen.

Hace muchos años, disfruté de un juego de simulación comercial llamado Taipan!. En un largo viaje en autobús desde Oxford, comencé a dibujar un mapa de estilo retro de sus puertos comerciales para su artículo.

Quería, en particular, bandas de tinte formadas por líneas paralelas y supuse que dibujando repetidamente las líneas de costa con un ancho de trazo decreciente en colores alternados lograría este efecto.

Luego se utilizaron efectos de filtro SVG para rellenar los mares con trazos horizontales cortos. Mientras jugaba con efectos de iluminación, encontré por casualidad una forma de simular líneas de contorno y relieve sombreado en la tierra.

Fue una lucha trabajar con las diferencias entre la representación de mi navegador y la de rsvg , pero el resultado general no se ve tan mal, ¿verdad ?

Encantado de que Cambridge tenga (aunque sea temporalmente) su propio modelo del Sistema Solar a escala 1:591 000 000 , actualicé mi sistema con SVG dinámicos incrustados.

Calculadora de modelos a escala del sistema solar

También subí posiblemente la escala más manejable, 1:10 000 000 000 como SVG independiente a Commons.

¡Esperamos que aparezcan más sistemas solares a gran escala en todo el mundo !

Después de dibujar con éxito el tablero de juego Risk como un gráfico con aristas rectilíneas y de 45°, decidí marcar el fin de la pandemia de COVID-19 con un nuevo dibujo del tablero de juego Pandemic .

Esta vez encontré draw.io, una aplicación web gratuita de dibujo vectorial que permite mover los vértices del gráfico mientras las aristas se mueven para adaptarse. No solo hizo que encontrar una disposición adecuada fuera mucho más eficiente, sino que el diagrama se podía exportar fácilmente, aunque lo redibujé con mi estilo preferido.

Desde que la vi por primera vez, la ilusión de Hollow-Face me fascinó. Primero hice un archivo STL que mostraba la ilusión, un buen ejercicio para aprender Blender . Conseguí encontrar un modelo CC-BY en Sketchfab y fue bastante fácil preparar las normales y reubicar el origen en Blender.

Luego, pensé que podía mejorar la animación GIF del artículo, así que continué con la creación de mi primera animación en Blender. En lugar de un archivo de video, decidí crear otro GIF, ya que tenía el problema de repetición con el reproductor de video en la sección siguiente.

Estoy muy satisfecho con el resultado. También hice uno que se mueve de izquierda a derecha para poder dedicarle más tiempo a la cara hueca. ¿Cuál prefieres?

¡Presentando mi primera contribución en video a Wiki[mp]edia !

Me sorprendió no encontrar ningún video del teorema de la raqueta de tenis en Wikimedia, así que decidí filmar tres demostraciones en mi patio trasero y hacer un video compuesto. Antes de filmar, cubrí con cinta la mitad de la raqueta para distinguir sus lados.

Después de extraer los fotogramas relevantes con FFmpeg , los recorté y los compuse con Python y OpenCV . Como la rotación ê 1 era mucho más rápida, repetí cada fotograma excepto el primero y el último. Invertí el orden de los fotogramas al final de la secuencia para que pudiera repetirse sin problemas. Finalmente, los exporté como video Ogg Theora con FFmpeg .

El vídeo se ve bien, aunque un poco borroso porque el enfoque automático de la cámara no logró enfocar la raqueta. También es un poco corto. Es una lástima que no haya podido encontrar una manera de hacer que el reproductor de vídeo reproduzca el clip en bucle. ¿Alguien tiene alguna idea?

ACTUALIZACIÓN 2022-05-04: Hice una animación GIF, Archivo:tennis_racket_theorem.gif que se ejecuta para siempre.

En cuanto a la hormiga sobre una cuerda de goma , se me ocurrió que las soluciones a los acertijos de cruce de ríos se pueden representar con líneas de tiempo . Son más útiles cuando se involucran unidades de tiempo, como el problema del puente y la antorcha y el acertijo de la cuerda quemada , pero también son beneficiosos cuando se muestran secuencias como en el problema de los misioneros y los caníbales y el problema del lobo, la cabra y el repollo .

El grupo Cambridge Wikimedian organizó una reunión en persona junto con Wikimania 2021. Pensé que sería apropiado realizar un recorrido fotográfico a pie por los monumentos catalogados cercanos después.

WikiShootMe identificó varias tumbas catalogadas en el cementerio de Mill Road . Aunque estaban cubiertas de vegetación, logré capturar la mayoría de ellas para Wikidata. También fue genial encontrarme con viejos compañeros de Wikidata después de un largo confinamiento por la pandemia.

Las listas de los países, islas y lagos más grandes a veces se ilustran con siluetas de cada objeto a escala. Si bien son útiles, se pierde el contexto porque faltan sus relaciones espaciales.

Me di cuenta de que la proyección Fuller o los mapas Dymaxion preservan sus posiciones relativas mientras mantienen aproximadamente la forma (conforme) y la escala (área igual), lo que permite comparar fácilmente las formas, tamaños y posiciones de estos objetos.

Después de encontrar mapas Dymaxion en blanco, creé estas tres visualizaciones. Lamentablemente, tuve que detener los diagramas de la isla y el país en el 30 para evitar que se llenaran demasiado, y el del lago en el 15, ya que el SVG original no tenía el lago Bangweulu.

En cuanto a SVG, no hay muchas novedades. Tuve que dividir algunas formas para obtener la parte relevante. El resto consiste simplemente en resaltar las formas adecuadas con CSS.

ACTUALIZACIÓN 2024-10-20: Estoy muy orgulloso de saber que el astronauta Chris Hadfield , mi héroe espacial, publicó sobre mi imagen 🥹

Después de crear el archivo File:Cambridge_University_colleges_timeline.svg , intenté crear uno para Oxford, pero no encontré suficiente información para llegar a ese punto. Me sorprendió gratamente que TSventon se pusiera en contacto conmigo y, a través de esta conversación , él o ella y Jonathan A Jones lograron descubrir suficientes datos para que el proyecto tuviera un nivel satisfactorio.

Me encontré con la magnífica habilidad de Sarang para reducir el tamaño de un archivo SVG a tan solo unos pocos cientos de bytes e intenté aplicar sus técnicas a algunos archivos SVG. El truco más impresionante es usar stroke-dasharray para dibujar líneas o formas repetidas, como esta figura, cuya fuente se encuentra a continuación:

<?xml version="1.0"?> <svg xmlns= "http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" viewBox= "0 0 8.05 8.05" fill= "ninguno" stroke= "#000" > <circle r= "99" fill= "#582" /> <path d= "M0,.5h7.5v1h-7v1h7v1h-7v1h7v1h-7v1h7v1h-7" stroke= "#feb" stroke-dasharray= "1" /> <path d= "M4,0v9M0,4h9" stroke-width= "9" stroke-dasharray= ".05,.95" /> <g stroke-width= ".5" stroke-dasharray= "0,2" stroke-linecap= "redondo" > <path d= "M1.5,.5h6v1h-7v1h8v3h-8m1,1h6v1h-7" ancho de trazo= ".6" /> <ruta d= "M1.5,.48h6v1h-7v1h7" trazo= "#c00" /> <ruta d= "M.5,5.48h7v1h-7v1h7" trazo= "#fff" /> </g> </svg> ¡Otro uso brillante de guiones SVG, además del tartán , las cadenas y los engranajes !

Alguien me preguntó en Template_talk:Generations_sidebar si podía simplificar mi imagen para que apareciera en Template:Generations_sidebar en tamaños pequeños. El SVG ya tenía internacionalización en catalán. En lugar de crear otra imagen, pensé en agregar otro "idioma" para ocultar detalles y hacer el texto más grande. lang=simple me pareció el "idioma" perfecto para este propósito. Para ocultar objetos, encontré que usar una etiqueta g en blanco era lo más sencillo:

< switch > < g systemLanguage = "simple" /> < use xlink : href = "#common_legend" /> </ switch > El cambio de tamaño de fuente se puede realizar mediante una clase CSS:

< switch > < text id = "gy-ca" transform = "translate(19720,-660)" dy = "0.7ex" systemLanguage = "ca" >< tspan class = "big" id = "trsvg27-ca" > Millennials ⧸ Generación Y </ tspan >< tspan x = "0" dy = "40" id = "trsvg28-ca" > ∗ 1981 – 96 </ tspan >/ text > < text id = "gy-simple" transform = "translate(19700,-660)" dy = "0.7ex" class = "simple" systemLanguage = "simple" >< tspan class = "big" id = "trsvg27" > Millennials </ tspan >< tspan x = "0" dy = "45" id = "trsvg28" > ∗ 1981 – 96 </ tspan ></ text > < text id = "gy" transform = "translate(19720,-660)" dy = "0.7ex" >< tspan class = "big" id = "trsvg27" > Millennials ⧸ Generación Y </ tspan >< tspan x = "0" dy = "40" id = "trsvg28" > ∗ 1981 – 96 </ tspan ></ text > </ switch > Una interacción reciente con David Eppstein me hizo interesarme en el daltonismo. La clasificación del daltonismo me enseñó que admitir la deuteranomalía, la protanomalía, la protanopía y la deuteranopía hace que mis diagramas sean accesibles para el 99,97 % de las personas con visión. Usando simulaciones de http://color-blindness.com/coblis-color-blindness-simulator, escribí un script de Python para crear una paleta de cuatro tonos (más gris) segura para la web que maximiza las diferencias para estos grupos y las personas con visión normal, y encontré el mejor compromiso

ACTUALIZACIÓN 19 DE SEPTIEMBRE DE 2021: Las pautas WCAG establecen 4,5 como la relación de contraste mínima para la clasificación AA para texto normal (o AAA para texto grande). Curiosamente, un color con una relación de alrededor de 4,6 con respecto al blanco también es de alrededor de 4,6 con respecto al negro. Por lo tanto, he encontrado 5 de esos colores que, en su mayoría, pueden distinguir las personas daltónicas y que se pueden representar con 3 dígitos hexadecimales:

Mientras depuraba un error de librsvg, aprendí sobre el uso de currentColor (sin distinción entre mayúsculas y minúsculas) para heredar colores en CSS.

Supongamos que tenemos algunos objetos de diferentes colores, pero el color de relleno de cada uno es el mismo que el color de su trazo , como en el caso de los puntos y las órbitas en este diagrama.

< style type = "text/css" > . toward { fill : #0000ff ; stroke : #0000ff ; } . forward { fill : #999999 ; stroke : #999999 ; } . orbit { fill : none ; } . object { stroke : none ; } </ style > < g class = "toward" > < use class = "orbit" xlink : href = "#orbit" /> < use class = "object" xlink : href = "#object" /> </ g > funciona pero repite los códigos de color, lo que posiblemente haga que se actualice una instancia pero no la otra. currentColor lo evita:

. hacia { color : #0000ff ; } . adelante { color : #999999 ; } . órbita { relleno : ninguno ; trazo : color actual ; } . objeto { relleno : color actual ; trazo : ninguno ; } En la parte superior del diagrama, un satélite en una órbita circular en el sentido de las agujas del reloj (punto amarillo) lanza objetos de masa insignificante:

Las elipses discontinuas son órbitas relativas a la Tierra. Las curvas continuas son perturbaciones relativas al satélite: en una órbita, (1) y (2) regresan al satélite después de haber realizado un bucle en el sentido de las agujas del reloj a cada lado del satélite. De manera poco intuitiva, (3) se aleja cada vez más en espiral hacia atrás, mientras que (4) se aleja en espiral hacia adelante.

SVG proporciona un útil filtro de mapa de desplazamiento que permite que una imagen sea "refractada" por otra. La escena submarina animada de la izquierda emplea la idea de [1] y [2], pero cambia el tono del mapa para evitar artefactos de ida y vuelta.

En lugar de animar un filtro, experimenté con la animación del objeto sobre el que se aplica un filtro que "convierte un cuadrado en un círculo", simulando una proyección ortográfica. Elegí nueve objetos astronómicos con texturas de commons:category:Solar_System_Scope. Cada textura se repitió y se desplazó horizontalmente a la velocidad correcta. Después de aplicar el filtro, calculado utilizando fórmulas de orthographic_map_projection#Mathematics , el resultado se recortó y se sombreó con una máscara, y se rotó a la inclinación axial correcta. Es una lástima que no pudiera imitar el aplanamiento, ya que Firefox generaba artefactos al intentar escalar imágenes filtradas.

Por último, con la ayuda de Wikipedia:SVG_help#Thumbnail_completely_black , agregué una textura sin distorsión que se oculta inmediatamente cuando comienza la animación, ya que el renderizador de miniaturas no reconoce feDisplacementMap.

La animación muestra que los gigantes gaseosos giran más rápido que los planetas terrestres, tanto que están sustancialmente aplanados. Venus, en el otro extremo, gira tan lentamente que tuve que conformarme con un compromiso de 10 000× de velocidad (y poner un marcador) para mostrar visiblemente el movimiento sin hacer que Júpiter y la Tierra giren demasiado rápido. También me parece interesante que Mercurio casi no tenga inclinación ni aplanamiento, pero su órbita está inclinada 7° respecto del plano de la eclíptica.

ACTUALIZACIÓN 20 DE JUNIO DE 2021: Al agregar la traducción al turco como lo solicitó Harald el Bardo , actualicé la clase dict2class en mi script generador de Python para trabajar de forma recursiva con diccionarios anidados :

clase dict2class ( dict ): def __getattr__ ( self , k ): devuelve dict2class ( self [ k ]) si esinstancia ( self [ k ], dict ) de lo contrario self [ k ]

La serendipia me llevó a este atractivo mapa 3D y me complació ver que su autor, Tom Patterson, lo había compartido generosamente junto con otros magníficos mapas de dominio público.

Subí sus tres versiones a Commons y nominé la versión en inglés como imagen destacada . Me alegra que varios otros editores y administradores hayan estado de acuerdo, y ahora es el mapa destacado más reciente .

Le envié un correo electrónico para felicitar al Sr. Patterson y le pregunté si podría estar interesado en hacer una en Challenger Deep o en la región de Tharsis . ¡Cruzo los dedos !

En los primeros días de la Web, a los desarrolladores web les encantaba usar imágenes de orbes vidriosos como viñetas en listas desordenadas. Un estilo que me gustaba era el efecto de orbe translúcido brillante de Apple , que se podía recrear usando dos degradados y un filtro (sin los cuales el "reflejo" es más nítido):

<filter id= "filter_blur" ><feGaussianBlur stdDeviation= "4" /></filter> <radialGradient id= "grad_sphere" cx= "50%" cy= "50%" r= "50%" fx= "50%" fy= "90%" > <stop offset= "0%" stop-color= "#000000" stop-opacity= "0" /> <stop offset= "99%" stop-color= "#000000" stop-opacity= "0.3" /> </radialGradient> <linearGradient id= "grad_highlight" x1= "0%" y1= "0%" x2= "0%" y2= "100%" > <stop offset= "10%" stop-color= "#ffffff" stop-opacity= "0.9" /> <stop offset= "99%" stop-color= "#ffffff" stop-opacity= "0" /> </linearGradient> <g id= "orbe" stroke= "ninguno" > <circle cx= "0" cy= "0" r= "100" /> <circle cx= "0" cy= "0" r= "100" fill= "url(#grad_sphere)" /> <ellipse cx= "0" cy= "-45" rx= "70" ry= "50" fill= "url(#grad_highlight)" filter= "url(#filter_blur)" /> </g> Como desde entonces he hecho varios diagramas con este efecto, decidí ponerlos en el orbe commons:category:SVG, análogo a commons:category:4-3-2_trimetric_projection.

El post de este mes trata sobre chistes y coincidencias matemáticas .

Curiosamente, 40.000 km (25.000 mi) aparece repetidamente en las estadísticas sobre la Tierra :

El radio de la órbita geoestacionaria , 42.164 kilómetros (26.199 millas), se encuentra dentro del 0,02% de la variación de la distancia de la Luna en un mes (la diferencia entre su apogeo y perigeo), 42.171 kilómetros (26.204 millas), y el 5% de error de la longitud del ecuador , 40.075 kilómetros (24.901 millas). De manera similar, la velocidad de escape de la Tierra es 40.270 km/h (25.020 mph).

Por otra parte, encuentro divertidos algunos razonamientos falaces, como la cancelación anómala antes mencionada que triunfa .

También resulta divertida esta verdadera observación:

Tuve la tentación de hacer que la densidad sea η – ordenando eta , la masa se convierte en comer pizza . Además, su peso es pizzagate – ¡aunque esta referencia podría quedar obsoleta muy pronto !

Me acordé de los "triángulos de fórmulas" que ideé para recordar fórmulas simples en la escuela y descubrí que en Wikipedia no había un diagrama que mostrara su uso, así que dibujé esto. Aunque es más conocido por la ley de Ohm, se puede aplicar a cualquier fórmula en la forma a = b · c · d · … (cada parámetro puede ser una función, pero se debe tomar la inversa del resto). Por lo tanto, dibujé un diagrama para estudiantes de física de secundaria a continuación. La selección exacta depende del programa de estudios, pero creo que he cubierto los más comunes.

En cuanto a los mnemónicos, hace poco descubrí uno para recordar el orden de los colores (ya sé que es Roy G Biv , pero ¿ en qué dirección?) en los espectros de refracción y difracción: R efracción reducida . Me costó encontrar un equivalente para difracción hasta que me di cuenta de lo siguiente: ¡ La difracción es diferente !

Parece que en el caso de los arcoíris ocurre lo contrario: se podría esperar que el rojo estuviera en el interior, pero hay un reflejo en las gotas de lluvia para los arcoíris primarios y dos para los secundarios . Un mnemónico adecuado es ¡R i m e r o d e arcoíris rojo !

Acabo de encontrar una forma de mejorar aún más los SVG como ayudas didácticas resaltando dos partes diferentes de un diagrama para compararlas usando solo CSS (SMIL permite resaltar cualquier cantidad de partes, pero el código es más difícil de manejar y había planes para desaprobar SMIL). En este gráfico de ejemplo, supongamos que un tutor desea señalar que la función vercosina es simplemente la función coseno más uno. En un dispositivo habilitado para mouse, puede hacer clic en el gráfico cos para resaltarlo (los demás gráficos se desvanecen) y luego pasar el mouse sobre el gráfico vercosina para que desaparezca y se coloque un brillo amarillo a su alrededor.

Mi método hackea los hipervínculos al vincularlos al mismo archivo mediante un ancla en blanco ( # ). Cuando se hace clic en un vínculo, su estado pasa a ser foco (en lugar de pasar el mouse sobre él cuando se pasa el mouse sobre él). A continuación se muestra la hoja de estilo: outline:none; oculta el contorno de un vínculo enfocado. Como antes, el brillo se logra con un filtro:

<style type= "text/css" >

.main:hover { opacidad de relleno: 0,2; opacidad de trazo: 0,2; } .active:hover { opacidad de relleno:1; opacidad de trazo:1; filtro:url(#filter_glow); }.active:focus { opacidad de relleno:1; opacidad de trazo:1; contorno:ninguno; }.nofade { opacidad de relleno: 1; opacidad de trazo: 1; } </style> <filter id= "filter_glow" > <feGaussianBlur en= "SourceAlpha" stdDeviation= "2" /> <feColorMatrix en= "blur" tipo= "matrix" valores= "0,0,0,0,1 0,0,0,0,1 0,0,0,0,0 0,0,0,2,0" /> <feBlend en= "SourceGraphic" /> </filter> Finalmente cada parte interactiva se define de la siguiente manera:

<a class="activo" xlink:href="#"> ... </a> Otro uso podría ser la revelación de información en varias etapas. Por ejemplo, un rompecabezas puede mostrar una pista al pasar el cursor sobre él y una respuesta al hacer clic. Me pregunto qué otros usos existen para este mecanismo...

Anteriormente había creado una serie de animaciones GIF visualizando series de Fourier y quería convertirlas en animaciones SVG, pero no sabía cómo hacer objetos animados anidados suaves; mi archivo:Rolling_circle_optical_illusion.svg era bastante desigual.

Cuando me encontré con la paradoja de la rotación de la moneda , le di otra oportunidad. Contiene dos animaciones: un círculo que rueda a lo largo de una línea y otra alrededor de otro círculo. Descubrí que anidar transformaciones sin ninguna otra transformación entre ellas funcionaba bien:

<g clase= "movimiento2" > <uso clase= "rot1" xlink:href= "#r" /> </g> ...<g clase= "rot2" > <g transformación= "traducir(0,-944)" > <uso clase= "rot1" xlink:href= "#r" /> </g> </g> donde move2 , rot1 y rot2 son animaciones CSS y r es el círculo a animar.

Tras el éxito, decidí abordar el problema de la transformada de Fourier. La parte más difícil fue sincronizar las animaciones. A diferencia de la animación en, por ejemplo, JavaScript, en la que se pueden especificar las rotaciones y traslaciones de cada fotograma, la animación CSS requiere especificar el período de cada animación. Los errores de redondeo se acumulan, por ejemplo, si el círculo A tiene un período de 1 s y el B de 0,33 s, mientras que inicialmente A parece girar 3 veces más rápido que B, después de 300 rotaciones, B se retrasará una rotación. Una solución que encontré fue hacer que todos los períodos sean fracciones de su mínimo común múltiplo . Los multiplicadores θ son 1, 3, 5 y 7. Además, para la figura combinada, necesitaba otro período para restar la rotación del círculo verde del círculo amarillo, etc., por lo tanto, un multiplicador efectivo de 2. Al ser coprimos, su MCM es 2 × 1 × 3 × 5 × 7 = 210. Por lo tanto, elegí 21 s para el círculo amarillo, lo que da 7 s, 4,2 s y 3 s para los otros círculos, y 10,5 s para la diferencia. (Sé que los quintos, por ejemplo, 4,2, no se pueden definir exactamente en binario (como 1/3 no puede estar en decimal), pero creo que el error es insignificante). ¡Después de mucho ensayo y error, funcionó !

ACTUALIZACIÓN 1 JUL 2020: Hice esta animación de engranajes planetarios...

ACTUALIZACIÓN 26 JUL 2020: ...y esta animación de funciones trigonométricas en un círculo unitario.

En 2012, dibujé el diagrama de la izquierda para ilustrar la interpolación lineal. Creo que hace que la fórmula quede mucho más clara. Durante ocho años, he buscado un equivalente para la interpolación cúbica. Después de consultar en la mesa de referencia de matemáticas y leer sobre el polinomio de Lagrange y el spline cúbico de Hermite , creo que finalmente lo encontré.

Aprendí que la interpolación cúbica no es única, ya que existe un grado de libertad sin restricciones: la interpolación polinómica analiza varios enfoques. Uno que me pareció adecuado para visualizar es el Catmull-Rom, que pasa por los cuatro puntos de control y, por lo tanto, se puede expresar utilizando polinomios de base de Lagrange. ¡Ese es un algoritmo que usaré en mi trabajo diario !

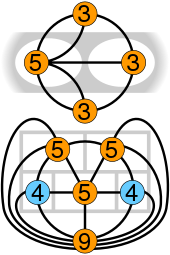

Una discusión sobre impresión 3D reavivó mi interés de siempre por los recorridos de Euler : cómo dibujar una trayectoria con un trazo continuo sin doblez. Muchos saben que la clave es tener dos o menos vértices con aristas impares.

En 2015, descubrí que los artículos sobre el camino euleriano , los siete puentes de Königsberg y el rompecabezas de las cinco habitaciones carecían de diagramas que mostraran realmente el recuento de aristas, así que dibujé este diagrama. Después de dibujar File:Eulerian_path_puzzles.svg , lo revisé y pensé que las aristas del vértice "9" estaban desordenadas. En ese momento, no podía decir qué era objetable. Me acabo de dar cuenta de que probablemente se trataba de los espacios entre las rutas que no aumentaban o disminuían monótonamente. Los volví a dibujar como a la derecha, haciendo que comenzaran casi paralelos y luego divergieran.

Un beneficio adicional es que parece un pequeño mamífero como un gato o un zorro, con orejas y bigotes 🐱

Me uní a una discusión en Commons_talk:SVG_Translate_tool sobre la herramienta SVG Translate. Ayudé a User:Ikonact a depurar por qué la herramienta no mostraba ninguna cadena para traducir en File:Corsica-geographic_map-en.svg y descubrí que tener una hoja de estilo con un selector de ID style (aquellos que comienzan con #) hace que la herramienta falle. Lo reporté como un error grave, ya que muchos SVG los usan. Para solucionar el problema, decidí cambiar id="main"a class="main"en mis nuevos.

Otro problema con la herramienta es que no actualiza la memoria caché de archivos, por lo que si se carga una nueva versión de un archivo, no la ve hasta varias horas después, lo que hace que sea muy difícil hacer algo . Recurrí a numerar secuencialmente las cargas, colocándolas bajo una categoría y solicitando que se eliminen y pidiendo a un administrador que las elimine.

Una de las cosas que más me resultó útil de la actividad fue aprender sobre el verificador SVG de Commons. Es muy útil poder ver la miniatura renderizada y descubrir errores SVG antes de subirla. Un truco es usarlo para renderizar un archivo PNG a partir de un SVG sin subirlo. Sé que puedo descargar herramientas para hacerlo, pero esto funciona desde cualquier computadora sin instalar nada .

Tuve una breve colaboración con @Juandamec: y @ Kirill Borisenko : sobre mi infografía de la línea de tiempo de las Siete Maravillas del Mundo Antiguo después de que amablemente la tradujeron al español y al ruso, respectivamente.

Al decidir convertirlo en un SVG multilingüe, no encontré una forma sencilla de ver los idiomas no predeterminados en un navegador antes de cargarlos. Una forma de hacerlo es instalar y cambiar el idioma del navegador y reiniciarlo, pero eso es un fastidio y afecta a toda la interfaz del navegador.

Por lo tanto, escribí un script en Python3 para extraer y escribir un archivo SVG monolingüe a partir de un archivo SVG multilingüe. Como no podía cargar un archivo Python, copié su código fuente en user:cmglee/extract_lang.py para que cualquiera pudiera copiarlo y pegarlo.

Mi primer uso fue para hackear la función multilingüe para crear un SVG que muestre los pasos para hacer un gráfico ternario , como el anterior. Lo bueno de esta técnica es que los editores pueden actualizar elementos comunes, por ejemplo, la cuadrícula y los ejes en un archivo en lugar de varios. Lamentablemente, la elección de códigos de idioma es limitada, por lo que elegí aa , ba , ca y da para hacer una secuencia razonable.

Acabo de descubrir (creo) una nueva aplicación para SVG interactivo sin JavaScript: un cuestionario que permite a los estudiantes aprender la ubicación de características geográficas, componentes de un sistema, etc. (básicamente, cualquier mapeo 1 a 1). Mi primer ejemplo se refiere a los estados de los EE. UU.

Me pregunto si alguien aquí conoce una forma elegante de implementar contadores sin JavaScript . En mi ejemplo, un estudiante podría comenzar con, digamos, tres vidas. Cada respuesta incorrecta (activada por el elemento "reset") descuenta una vida. Cuando se pierden todas las vidas, el juego termina. Una solución alternativa es tener tantos elementos de reinicio como vidas y eliminar los elementos a medida que se agotan las vidas. Sin embargo, eso generaría mucho código redundante :-(

Una versión menos estricta sólo cuenta el número de respuestas incorrectas y lo muestra al final cuando se han identificado todos los estados.

Como alternativa, podría implementar un temporizador que cuente la cantidad de segundos (como en mi demostración de transformación) pero que lo pause cuando se hayan identificado todos los estados, para mostrar cuánto tiempo le tomó al estudiante. Una solución alternativa es agregar onmousemove="document.getElementsByTagName('svg')[0].pauseAnimations();"la pantalla de victoria, pero:

on*atributos(Puedo hacer una versión en la que un cronómetro cuenta regresivamente hasta cero y el juego termina si el estudiante no logra identificar todos los estados a tiempo, como en mi juego de misiles, aunque un límite de tiempo puede frustrar a los estudiantes).

¿Podrías ayudarme?

Una de las ventajas de los vuelos es ver y fotografiar vistas aéreas. Un consejo que he encontrado es disparar lo más perpendicularmente posible a la ventana y evitar el turbulento escape. Para eliminar la neblina, utiliza la máscara rápida de GIMP para crear una selección de degradado de cerca a lejos y utiliza la herramienta Curvas para fijar los canales de color, especialmente el azul, y ajustar el brillo y el contraste. Reducir la saturación del color disminuye el tono amarillento de las nubes. Sin embargo, cuando el aire está despejado, los resultados son espectaculares.

El usuario:Drégigori me informó que el objeto transneptuniano Ultima Thule había sido renombrado Arrokoth. Mientras revisaba la actualización del usuario:Mrmw a file:interstellar_probes_trajectory.svg , pensé que al pasar el cursor sobre una sonda interestelar se deberían resaltar todos los objetos astronómicos con los que interactuaba, y viceversa. Al clasificar el objeto sobre el que se pasaba el cursor como activo y sus objetos asociados como asociados , me di cuenta de que cada grupo activo podría contener copias de los objetos asociados con pointer-events:none establecido, por ejemplo

<style type= "text/css" > #main:hover { opacidad de trazo: 0,05; opacidad de relleno: 0,05; } .nofade, .active:hover { opacidad de trazo: 1; opacidad de relleno: 1; } .nofade, .associated { eventos de puntero: ninguno; } ... </style> ...<g class= "activo" > <g class= "asociado" > <use xlink:href= "#p1" /> <!-- Pioneer 11 --> <use xlink:href= "#v1" /> <!-- Voyager 1 --> <use xlink:href= "#v2" /> <!-- Voyager 2 --> </g> <use xlink:href= "#s" /> <!-- Saturno --> </g> ...Hice este ejemplo de juguete para que los editores puedan reutilizar esta técnica y actualicé el archivo:interstellar_probes_trajectory.svg en consecuencia.

Este año, las autoridades del Scrabble inglés agregaron tres palabras de dos letras a la lista de palabras válidas :¡Qué extraño!,DE ACUERDOyZE– lo cual leí como "EL EWOK!" Para marcar la ocasión, hice esta tabla que muestra todas las palabras válidas de dos letras que comienzan y terminan con cada letra, anotando años de cambios (es una maravillaFilipinasentró).

Lamentablemente, todavía no hay ninguno conV☹ – Si alguno de ustedes alguna vez se vuelve famoso e inventa alguna tecnología o concepto que involucre visión, por favor, por favor, por favor, llámenlo unaVI☺

Commons:User:Cwtyler me envió un mensaje sobre una ilusión óptica de deriva periférica que hice hace cinco años; descubrió que los colores se desvanecen después de mirarla.

Curiosamente, la miniatura de Wikimedia no muestra lo que yo había pensado originalmente: debería haber parecido a la versión corregida que aparece a continuación. Cuando tuve problemas con un degradado lineal SVG que se transformaba incorrectamente para mi diagrama de sistemas de aterrizaje que aparece a continuación, User:Glrx me enseñó a agregarlo gradientUnits="userSpaceOnUse"para que librsvg coincida con los navegadores web modernos. El inconveniente es que los valores x e y no se pueden especificar en porcentajes.

Después de arreglar la miniatura, decidí generar una ilusión de desplazamiento periférico muy fuerte. Descubrí que el color es irrelevante: solo lo es la luminancia. Sorprendentemente, descubrí que si lo giro (por ejemplo, en mi teléfono) 45° en cualquier dirección, ¡el desplazamiento se detiene ! ¿Alguien puede explicar por qué?

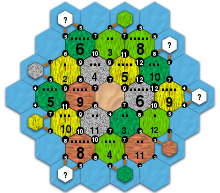

Continuando mi experimentación con filtros SVG, disfruté haciendo texturas para los tipos de terreno de Catan con feTurbulence :

Lamentablemente, la intensidad de la textura en Firefox y Chrome no coincide con la de la miniatura de Wikimedia (librsvg), las texturas con efectos de iluminación se atenúan y viceversa. Sin embargo, el gráfico muestra el mapa inicial de Catan Universe , siendo el punto principal la probabilidad relativa de que cada ubicación de asentamiento produzca productos. Parece un poco desequilibrado, la esquina noreste tiene varios 12 y el único puerto genérico está bordeado por dos hexágonos de terreno.

ACTUALIZACIÓN 17 NOV 2019: Un uso más real de las texturas SVG se encuentra en el archivo:Brooklyn_bridge_section.svg .

¡Saludos desde Estocolmo Wikimania 2019 !

Anteriormente me había esforzado por recordar a qué rotaciones se referían los lanzamientos de balanceo, cabeceo y guiñada , y me encontré con una regla mnemotécnica de un lanzador de béisbol haciendo un lanzamiento por encima de la cabeza . Como los lanzamientos de costado son más bien de guiñada, pensé en un lanzador de agua: ¡solo una rotación sensata evita derramar agua por todas partes ! A continuación, el balanceo es inequívoco cuando se aplica a un perro o un gato.

Por último, está yaw. Lamentablemente, un bostezo, o asentir con la cabeza para indicar que "sí", es más parecido a un tono. Entonces busqué palabras que rimaran con "yaw". "Draw" describe el movimiento del antebrazo de un artista. Pero la más clara es "door" (que rima en inglés británico, sin la "r" pronunciada: /dɔː/) –no la variedad garage, por supuesto. De ahí el dibujo...

No hay nada especial en el lado SVG, excepto tal vez el uso de transformaciones de escala y rotación , y el apilamiento de formas para hacer la flecha pseudo-3D.

Al actualizar este gráfico, pensé en sombrear los espacios entre los gráficos de los equipos que compiten para mostrar quién va en cabeza en cada momento, pero no se me ocurrió una forma elegante en SVG. Este año, se me ocurrió usar dos rutas de recorte : Al aplicar una ruta de recorte que selecciona la región por encima del gráfico A a la región por debajo del gráfico B, solo quedan las regiones por encima de A pero por debajo de B, y viceversa. La figura de la derecha explica los pasos visualmente. Para evitar superponer regiones, decidí hacerlo solo para los Blue Boats.

Para complementar las fechas que se muestran al pasar el cursor sobre un gráfico o la leyenda, hice que al pasar el cursor sobre una región en blanco se muestren los resultados del año más cercano. Me pregunto cómo puedo llamar la atención sobre el empate técnico en 1877...

Ian Furst me contactó para pedirme ayuda con un video en el que está trabajando . Quería una plantilla que mostrara el contorno de un cuerpo humano con varios síntomas superpuestos en las partes relevantes. Los editores pueden especificar fácilmente la combinación de síntomas que se muestran mediante Wikitext.

Después de pensarlo un poco, decidí crear una plantilla que envolviera template:Location mark+ . También aprendí sobre el uso de

{{#invoke:String|find|haystack|needle}}

Para comprobar si una cadena contiene otra. Se puede especificar cualquier combinación de los síntomas admitidos de la siguiente manera:

{{User:Cmglee/T symptoms man|Bieberitis|nausea,shortness_of_breath,tingling,muscle_weakness}}

Hubiera sido mucho mejor si SVG admitiera la capacidad de habilitar y deshabilitar sus partes sin JavaScript. Anteriormente, descubrí la capacidad de hackear la funcionalidad systemLanguage, pero con solo 443 idiomas admitidos, la libertad total para admitir las 2 n combinaciones permite solo n = 8 síntomas, a pesar de la asignación extremadamente poco intuitiva entre los códigos de idioma y las combinaciones. Debe haber una mejor manera...

Tuve una visita inesperada a la nueva mezquita de Cambridge. Me había fascinado su moderna arquitectura de madera desde que se inauguró y estaba dando un paseo al atardecer cuando decidí aventurarme a cruzar las puertas. Un caballero nos invitó a mi acompañante y a mí a entrar para unirnos a la ruptura del ayuno.

Fue una experiencia muy agradable conocer a la gente amable del lugar y hacer un breve recorrido por él. Ojalá la gente fuera civilizada entre sí como lo fue conmigo durante mi visita...

No hace falta decir que la arquitectura era realmente asombrosa, en particular los árboles abstractos y el árabe pixelado en los ladrillos. ¡Hay que volver de día !

Las bibliotecas públicas de Cambridge tienen horarios de apertura muy complicados, por lo que hice este gráfico para mostrar tanto cuándo abre cada biblioteca (columna de la izquierda) como para un día y hora determinados, qué bibliotecas están abiertas (columna de la derecha). Esto último es útil especialmente cuando de repente recuerdo que tengo un libro atrasado y necesito correr a una biblioteca abierta para devolverlo lo antes posible ∗ejem∗

Al hacerlo, actualicé mi función de Python 2 para leer y almacenar en caché páginas web, imágenes, etc.:

# do_refresh_cache = True import os , urllib2 , time def read_url ( url , headers = {}, path_cache = None , is_verbose = True ): if ( path_cache es None ): file_cache = os . path . basename ( url ) path_cache = os . path . join ( ' %s .cache' % ( os . path . splitext ( __file__ )[ 0 ]), file_cache if ( len ( file_cache ) > 0 ) else ' %s . htm' % ( os . path . basename ( url . rstrip ( '/' )))) if (( 'do_refresh_cache' en globals () y do_refresh_cache ) o ( no os . path . isfile ( path_cache ))): request = urllib2 . Request ( url , headers = headers ) try : html = urllib2 . urlopen ( request ) . read () except urllib2 . HTTPError as e : html = '' ; print ( e ) try : os . makedirs ( os.path.dirname ( path_cache ) ) excepto OSError : pasar con open ( path_cache , ' wb ' ) como f_html : f_html.write ( html ) if ( is_verbose ): print ( ' %s > %s ' % ( url , path_cache )) time . sleep ( 1 ) ## evitar error de límite de velocidad excedido else : with open ( path_cache ) as f_html : html = f_html . read () if ( is_verbose ): print ( '< %s ' % ( path_cache )) try : html = html . decode ( 'utf-8' ) except UnicodeDecodeError : pass return htmlEl recurso se almacena en caché en una ruta determinada [si no se especifica, el nombre base de la URL (si está en blanco, el nombre de la última carpeta en la URL seguido de .htm ) en una carpeta llamada el nombre del script de Python con la extensión reemplazada por cache ] de modo que las ejecuciones posteriores no necesiten recuperarlo nuevamente. Si la variable global do_refresh_cache es True , siempre se recupera. Se agrega un retraso de un segundo para evitar saturar el servidor web. Luego, el recurso se devuelve como una cadena Unicode.

El siguiente ejemplo obtiene la página de horarios de apertura de la biblioteca del Consejo del Condado de Cambridgeshire usando un encabezado falso simple. Descubrí que el servidor web rechaza las solicitudes sin un agente de usuario sensato . html_all se puede analizar según sea necesario con xml.etree.ElementTree o expresiones regulares .

url = 'http://cambridgeshire.gov.uk/residents/libraries-leisure-%26-culture/libraries/library-opening-hours/' headers = { 'User-Agent' : 'Mozilla' } html_all = read_url ( url , headers = headers )Espero hablar sobre esta y otras técnicas para generar SVG automáticamente usando Python en Wikimania 2019. ¡Cruzo los dedos !

Parece que hay cierta fascinación con mi antiguo archivo gráfico: Voyager_2_velocity_vs_distance_from_sun.svg ; aparece regularmente en lugares aleatorios de la Web. Pensé que sería genial tener también un mapa de las cinco sondas interestelares actuales , pero es sorprendentemente difícil de encontrar. Incluso la NASA solo tenía uno hasta principios de los años 90, antes del lanzamiento de New Horizons . Así que, con cierta dificultad, logré encontrar dos sitios que proporcionaban las coordenadas heliocéntricas de estas naves espaciales y los planetas para cada día durante un período de varias décadas: COHOWeb y Horizons On-Line Ephemeris System.

En un tránsito largo, escribí un script en Python para cotejar los datos en una tabla, para el primer día de cada mes. Luego actualicé mi script habitual, casi políglota, para trazar vistas ortográficas, con suerte mostrando claramente cada trayectoria, especialmente las ayudas gravitacionales .

¡Me pregunto si es el primer mapa que muestra las cinco sondas hasta la fecha !

ACTUALIZACIÓN DEL 22 DE ENERO DE 2019: Agregué Ultima Thule al gráfico. Supongo que eso es una ventaja de renderizar el SVG en Python: es fácil agregar nuevos cuerpos que New Horizons encuentre en el futuro.

Hacía tiempo que sabía que la relación entre los volúmenes de un cono, una esfera y un cilindro del mismo radio y altura era 1:2:3; Arquímedes consideró su descubrimiento de la relación 2:3 su obra maestra .

Por eso me quedé asombrado al descubrir por mi cuenta que la proporción de sus áreas superficiales totales, incluidas las tapas, era ϕ :2:3 (vale, Arquímedes descubrió el bit 2:3).* Es una aparición completamente inesperada de la proporción áurea , así que tuve que actualizar mi antiguo dibujo con mi hallazgo. Una ecuación con ϕ y π : ¿qué tan genial es eso?

* La superficie curva del cono se puede aplanar en un sector de radio r √5 (usando el teorema de Pitágoras) y longitud de arco 2 π r (la circunferencia del casquete). Como un círculo completo de radio r √5 tiene una circunferencia de 2 π r √5, nuestro sector subtiende 1/√5 de una revolución, dando un área de 1/√5 · π ( r √5)² = π r ²√5. Agrega la tapa y el área total es π r ²√5 + π r ² = √5 + 1/2 · 2 π r ² = ϕ · 2 π r ² .

PS Otra coincidencia es que las proporciones de los volúmenes y las áreas de superficie de la esfera y los cilindros son de 2:3. Como en el gráfico de la derecha, la proporción entre el área de superficie y el volumen de un objeto disminuye al aumentar la redondez y el volumen. Es curioso que, al pasar de la esfera al cilindro, la redondez disminuye mientras que el volumen aumenta exactamente al mismo ritmo, de modo que la proporción se mantiene .

Charles Matthews me convenció para que hablara sobre las imágenes en Wikidata en el taller de ayer. Después de una noche de estudio, me encontré con esta presentación improvisada que trata sobre

Magnus Manske amablemente participó, respondió preguntas y señaló errores en mi comprensión.

También mostré algunos de mis SVG SMIL: la animación del Reloj Corpus fue especialmente popular.

En definitiva, ¡un magnífico día de intercambio de conocimientos !

Los filtros SVG permiten efectos divertidos, como en la luz animada en la animación de nieve que aparece a continuación, pero también les encontré algunos usos prácticos. Los más simples pueden ser las sombras paralelas para hacer que las escenas pseudo-3D sean más realistas, como las sombras paralelas suaves en el gráfico del número de Platón. Para mantener el filtro lo más simple posible, se pueden hacer dos copias de los objetos; al aplicar el filtro a la copia inferior, las áreas opacas se vuelven negras y se difuminan:

<filtro id= "filter_blur" > <feGaussianBlur en= "OrigenAlfa" stdDeviation= "2" > </filtro> Por el contrario, se pueden difuminar y convertir en blancas las áreas opacas para crear un brillo alrededor de los objetos, como el texto, para que sea más fácil de leer. La etiqueta feColorMatrix colorea las áreas difuminadas de blanco y las hace menos transparentes, de modo que el contorno sea más nítido. La combinación con SourceGraphic evita la necesidad de tener dos copias del objeto:

<filter id= "filter_glow" > <feGaussianBlur en= "SourceAlpha" stdDeviation= "1" resultado= "desenfoque" /> <feColorMatrix en= "desenfoque" tipo= "matriz" valores= "0,0,0,0,1 0,0,0,0,1 0,0,0,0,1 0,0,0,8,0" resultado= "blanco" /> <feBlend en= "SourceGraphic" en2= "blanco" /> </filter> El último ejemplo es algo que quería hacer desde que publiqué esta pregunta sobre la aplicación de un contorno graduado a una forma, en particular el segundo caso. Un filtro lo resuelve de manera elegante; después de difuminar, el contorno se erosiona para poner en negrita el límite y luego se compone utilizando el operador out :

<filter id= "filter_outline" > <feGaussianBlur stdDeviation= "4" result= "blur" /> <feMorfología in= "blur" operator= "erose" radius= "4" result= "erose" /> < feOperador compuesto= "out" in= "SourceGraphic" in2= "erose" /> </filter> Esta imagen de una cancha de tenis libre muestra mi primer uso de las dos últimas técnicas, en las etiquetas de texto y los límites de los pabellones. ¡Diviértete con los filtros !

Esta pregunta me hizo reflexionar sobre la probabilidad de que aparezcan blasfemias en las cadenas Base64 que utilizo para incrustar mapas de bits en mis SVG. Como estimación de orden de magnitud, supongamos que la cadena consta solo de letras y no importa si se usan mayúsculas o minúsculas, una cadena aleatoria de cuatro letras tiene 1/26 4 ≈ 1/456 976 probabilidad de que coincida con una palabra de cuatro letras dada. Una cadena de 1 MB tiene alrededor de 1 millón de estas cadenas, por lo que espero alrededor de dos coincidencias. Hice una búsqueda sin distinción entre mayúsculas y minúsculas de la palabra F en mi archivo de 1,9 MB:Leonardo_da_Vinci_monument_in_Milan.svg (que tenía cadenas separadas, pero eso es lo suficientemente cercano) y de hecho obtuve tres instancias. ¡Espero que nadie se ofenda por mi SVG !

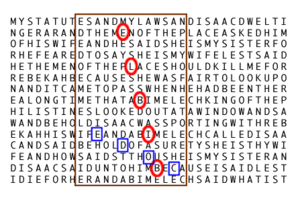

Me recordó a la locura de desacreditar el código bíblico en Cambridge alrededor de 2010. Al buscar el artículo, encontré que el PNG de la derecha era difícil de leer porque el texto estaba en mayúsculas y los "códigos" iban de abajo a la derecha a arriba a la izquierda. Pensé que podía hacerlo más legible y vectorizarlo al mismo tiempo: puse las palabras alternativas en negrita. Casualmente, en el caso correcto, solo la B inicial estaba en mayúscula. Pero el mejor cambio fue usar 21 columnas en lugar de 33; con el desplazamiento correcto, esto hizo que el "código" fuera de izquierda a derecha y no cruzado.

Como había escrito Python que realmente buscaba en el texto, decidí hacer una versión con marca local con "wiki" y "pedia" (no pude encontrar "wikipedia"). Genesis tenía muchas coincidencias, así que elegí una en la que estaban muy juntas. No pude evitar el cruce sin distorsionar demasiado los "códigos" o hacerlos de derecha a izquierda. Ver más abajo...

Acabo de enterarme del calendario juliano revisado, que mejora el calendario gregoriano . Su fórmula para decidir si un año centenario (número de año terminado en "00") es bisiesto no era obvia, así que decidí dibujar esta tabla, que deja claro que hay 2 años bisiestos cada 9 años centenarios, en comparación con 2 cada 8 en el gregoriano. Su diseñador dispuso inteligentemente los dos en el lapso actual de 900 años para que coincidieran con 2000 y 2400, lo que significa que los calendarios coincidirán perfectamente para los años 1601 a 2799, a pesar de la reforma del calendario gregoriano . ¡Eso debería ser suficiente por un tiempo !

El Wikitext en sí no es demasiado interesante, simplemente envuelve la tabla en un div que flota hacia la derecha para simular un cuadro de información. No pude usar la clase infobox porque las celdas de la tabla dejaron de estar alineadas al centro. También aprendí el uso de template:navbar para permitir que los editores editen plantillas más fácilmente y me divirtió la gran cantidad de plantillas de marcas de verificación y de cruces .

Me alegra mucho que Vincent Mia Edie Verheyen me haya contactado recientemente para pedirme ayuda con SVG interactivos y animados. ¡Finalmente encontré a alguien que comparte mi interés en los SVG dinámicos !

Descubrió que muchas técnicas CSS o SMIL aún no funcionan con Internet Explorer/Edge. La única interactividad fiable parece ser el desplazamiento del cursor, las sugerencias de herramientas, los hipervínculos y el cambio del puntero (cursor). Aparentemente, el selector :active también permite hacer clic, pero el usuario debe presionar el botón continuamente. Parece que la industria se ha pasado a JavaScript (no es una sorpresa en realidad) – ¿hay alguna esperanza de que Wikimedia permita al menos algo de Javascript en las cargas de archivos? :-(

De todos modos, me alegró aprender de Vincent sobre la etiqueta de símbolo , tal como se usa en este SVG animado. Puede hacer más que los objetos nombrados en defs que he estado usando, como escalar el objeto para que se ajuste a un ancho y alto determinados (conservando opcionalmente la relación de aspecto). También admite el atributo viewBox como la etiqueta svg . http://sarasoueidan.com/blog/structuring-grouping-referencing-in-svg/ tiene un tutorial.

Una limitación es que las partes del símbolo con coordenadas negativas se recortan. Una solución es agregar overflow="visible" , por ejemplo

<símbolo id= "cosas" desbordamiento= "visible" > <rect x= "-10" y= "-20" ancho= "30" alto= "40" /> </símbolo> <use xlink:href= "#cosas" x= "50" y= "60" /> Además, se puede mover el símbolo especificando los atributos x e y en la etiqueta de uso , donde antes podría haber usado transform=translate(50,60) . ¡Tres hurras por el intercambio de conocimiento bidireccional en Wikimedia !

He estado experimentando con STL durante el último mes. User:Romanski me recordó que la mayor parte de lo que he hecho, incluidos los fractales, ya se puede hacer con otras herramientas. Sin embargo, un área a la que creo que puedo contribuir son los modelos de elevación planetaria, como este. Para mí, un modelo 3D, particularmente uno físico, hace que la forma sea mucho más clara que un mapa topográfico, especialmente las características de las regiones polares. (Quizás una cosa que se pierde es que el hemisferio norte está significativamente más bajo que el sur). Es una pena que la mayoría de los visores STL, incluido el de Mediawiki, no admitan colores; eso definitivamente abriría un mundo completamente nuevo de posibilidades.

De todos modos, mirando el historial del archivo , se puede ver cómo evolucionó mi técnica:

Hice otros dos modelos con el método final:

El siguiente paso puede ser utilizar una red irregular triangulada , pero eso tendrá que esperar a otro día...

Como en la entrada del mes pasado que aparece a continuación, Wikipedia permite colecciones de imágenes que se ajustan al ancho del navegador mediante la etiqueta <gallery> . Sin embargo, mi lado asperger se enoja cuando solo hay una imagen solitaria en la última fila ☹

Me di cuenta de que, aunque no puedo controlar cuántas columnas habrá, sí puedo controlar cuántas imágenes hay en la galería, así que hice un pequeño script en Python para generar una tabla que resalte los números "buenos". Obviamente, es inevitable que quede uno cuando p = kc + 1 para cualquier entero k, pero ¿qué pasa con los demás números?

Además de los números altamente compuestos como 6, 12 y 60, existen números sorprendentemente "buenos" como 14, 38 y 44. Por otro lado, 10 y 36 son "malos" ya que dejan 1 resto con 3 y 5, respectivamente. Y los números posteriores a los altamente compuestos, como 13 y 25, son especialmente "malos"...

Como nota al pie, aprendí que en tipografía, una sola palabra en una línea al final de un párrafo se llama huérfana . ¡Parece que no soy el único al que le molesta !

Me encantó saber de Charles Matthews que Wikimedia Commons ahora permite cargar archivos 3D en formato STL , siempre y cuando admitiera color, transparencia, animación, etc.

Como en una vida pasada disfruté del modelado 3D, me dispuse a crear los modelos que se muestran a continuación utilizando scripts de Python. Como los archivos STL no permiten incrustar los scripts como comentarios, los agregué a las páginas de descripción de archivo. Lamentablemente, encontré artefactos en el visor de Wikimedia y, ocasionalmente, en la miniatura . He comprobado que la dirección de los vértices de las facetas es en sentido antihorario, las normales son sensatas y los polígonos no están duplicados. Parece que sucede más donde el poliedro es delgado. Todos estos poliedros se representan correctamente en http://viewstl.com. Veamos si se pueden arreglar...