Una causa próxima es un evento que está más cerca de algún resultado observado o es inmediatamente responsable de causarlo . Esto existe en contraste con una causa última de nivel superior (o causa distal ) que generalmente se considera la razón "real" por la que ocurrió algo.

El concepto se utiliza en muchos campos de la investigación y el análisis, incluida la ciencia de datos y la etología .

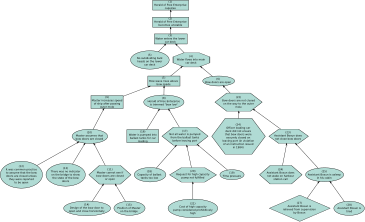

En la mayoría de las situaciones, una causa última puede ser en sí misma una causa próxima en comparación con una causa última adicional. Por lo tanto, podemos continuar el ejemplo anterior de la siguiente manera:

Aunque el comportamiento en estos dos ejemplos es el mismo, las explicaciones se basan en diferentes conjuntos de factores que incorporan factores evolutivos versus fisiológicos.

Estos se pueden dividir aún más, por ejemplo, las causas próximas pueden darse en términos de movimientos musculares locales o en términos de biología del desarrollo (consulte las cuatro preguntas de Tinbergen ).

In analytic philosophy, notions of cause adequacy are employed in the causal model. In order to explain the genuine cause of an effect, one would have to satisfy adequacy conditions, which include, among others, the ability to distinguish between:

One famous example of the importance of this is the Duhem–Quine thesis, which demonstrates that it is impossible to test a hypothesis in isolation, because an empirical test of the hypothesis requires one or more background assumptions. One way to solve this issue is to employ contrastive explanations. Several philosophers of science, such as Lipton, argue that contrastive explanations are able to detect genuine causes.[1] An example of a contrastive explanation is a cohort study that includes a control group, where one can determine the cause from observing two otherwise identical samples. This view also circumvents the problem of infinite regression of "why" questions that proximate causes create.

Sociologists use the related pair of terms "proximal causation" and "distal causation".

Proximal causation: explanation of human social behaviour by considering the immediate factors, such as symbolic interaction, understanding (Verstehen), and individual milieu that influence that behaviour. Most sociologists recognize that proximal causality is the first type of power humans experience; however, while factors such as family relationships may initially be meaningful, they are not as permanent, underlying, or determining as other factors such as institutions and social networks (Naiman 2008: 5).

Distal causation: explanation of human social behaviour by considering the larger context in which individuals carry out their actions. Proponents of the distal view of power argue that power operates at a more abstract level in the society as a whole (e.g. between economic classes) and that "all of us are affected by both types of power throughout our lives" (ibid). Thus, while individuals occupy roles and statuses relative to each other, it is the social structure and institutions in which these exist that are the ultimate cause of behaviour. A human biography can only be told in relation to the social structure, yet it also must be told in relation to unique individual experiences in order to reveal the complete picture (Mills 1959).