En febrero y marzo de 2014, Rusia invadió la península de Crimea , parte de Ucrania , y luego se la anexó . Esto ocurrió en el relativo vacío de poder [34] que siguió inmediatamente a la Revolución de la Dignidad y marcó el comienzo de la guerra ruso-ucraniana .

Los acontecimientos en Kiev que derrocaron al presidente ucraniano Viktor Yanukovich el 22 de febrero de 2014 provocaron manifestaciones prorrusas en Crimea contra el gobierno ucraniano entrante . Al mismo tiempo, el presidente ruso Vladimir Putin discutió los acontecimientos ucranianos con los jefes de seguridad, señalando que "debemos comenzar a trabajar para devolver Crimea a Rusia". El 27 de febrero, fuerzas especiales rusas sin insignia [35] tomaron lugares estratégicos en Crimea. [36] [37] Aunque Rusia negó inicialmente su participación militar, [38] Putin admitió más tarde que se desplegaron tropas para "apoyar a las fuerzas de autodefensa de Crimea". [39] Cuando las tropas rusas ocuparon el parlamento de Crimea , destituyó al gobierno de Crimea , instaló el gobierno prorruso de Aksyonov y anunció un referéndum sobre el estatus de Crimea . El referéndum se celebró bajo ocupación rusa y, según las autoridades instaladas por Rusia, el resultado fue abrumadoramente a favor de unirse a Rusia. Al día siguiente, el 17 de marzo de 2014, las autoridades de Crimea declararon su independencia y solicitaron unirse a Rusia. [40] [41] Rusia incorporó formalmente a Crimea el 18 de marzo de 2014 como la República de Crimea y la ciudad federal de Sebastopol . [42] [39] Tras la anexión, [43] Rusia aumentó su presencia militar en la península y advirtió contra cualquier intervención externa. [44]

Ucrania y muchos otros países condenaron la anexión y la consideraron una violación del derecho internacional y de los acuerdos rusos que salvaguardan la integridad territorial de Ucrania. La anexión llevó a los demás miembros del G8 a suspender a Rusia del grupo [45] e introducir sanciones . La Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas también rechazó el referéndum y la anexión, adoptando una resolución que afirmaba la "integridad territorial de Ucrania dentro de sus fronteras internacionalmente reconocidas", [46] [47] y se refería a la acción rusa como una "ocupación temporal". [48]

El gobierno ruso se opone a la etiqueta de "anexión", y Putin defiende el referéndum por considerar que cumple con el principio de autodeterminación de los pueblos. [49] [50]

Los nombres de la anexión de Crimea varían. En Ucrania, la anexión se conoce como la ocupación temporal de la República Autónoma de Crimea y Sebastopol por Rusia ( ucranio : тимчасова окупація Автономної Республіки Крим і Севастополя Росією , romanizado : tymchasova okupatsiia Avtonomnoi Respubliky K rym i Sevastopolia Rosiieiu ), la ocupación ilegal de la República Autónoma de Crimea , caída de Crimea y invasión de Crimea . [51] [52] [53] [54]

En la Federación de Rusia, también se conoce como la adhesión de Crimea a la Federación de Rusia ( ruso : присоединение Крыма к Российской Федерации , romanizado : prisoyedineniye Kryma k Rossiyskoy Federatsii ), el regreso de Crimea ( ruso : возвращение Крыма ro , manizado : vozvrashcheniye Kryma ), y la reunificación de Crimea . [55] [56]

Crimea fue parte del Kanato de Crimea desde 1441 hasta que fue anexada por el Imperio ruso en 1783 por decreto de Catalina la Grande . [57] [58] [59]

Tras la caída del imperio ruso en 1917, durante las primeras etapas de la guerra civil rusa, hubo una serie de gobiernos independientes de corta duración ( República Popular de Crimea , Gobierno Regional de Crimea , RSS de Crimea ). A estos les siguieron los gobiernos de la Rusia Blanca ( Comando General de las Fuerzas Armadas del Sur de Rusia y, más tarde, Gobierno del Sur de Rusia ).

En octubre de 1921, la RSFSR rusa bolchevique obtuvo el control de la península e instituyó la República Socialista Soviética Autónoma de Crimea como miembro de la Federación Rusa. Al año siguiente, Crimea se unió a la Unión Soviética como parte de Rusia (la RSFSR ).

Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial y la deportación de todos los tártaros de Crimea autóctonos por parte del gobierno soviético en 1944 , la República Socialista Soviética Autónoma de Crimea fue despojada de su autonomía en 1946 y degradada a la condición de óblast de la República Socialista Soviética Federativa Soviética de Rusia. En 1954, el óblast de Crimea fue transferido de la República Socialista Soviética Federativa Soviética de Rusia a la República Socialista Soviética de Ucrania por decreto del Presidium del Sóviet Supremo de la Unión Soviética para conmemorar el 300 aniversario de la unión de Ucrania con Rusia . [60] [61] En 1989, bajo la perestroika de Gorbachov , [62] el Sóviet Supremo declaró que la deportación de los tártaros de Crimea bajo Stalin había sido ilegal [63] y se permitió que el grupo étnico mayoritariamente musulmán regresara a Crimea. [64]

En 1990, el Soviet del óblast de Crimea propuso la restauración de la República Socialista Soviética Autónoma de Crimea. [65] El óblast llevó a cabo un referéndum en 1991, en el que se preguntaba si Crimea debía ser elevada a signataria del Nuevo Tratado de la Unión (es decir, convertirse en una república de la unión por sí misma). Sin embargo, para entonces, la disolución de la Unión Soviética ya estaba en marcha. La República Socialista Soviética de Crimea fue restaurada durante menos de un año como parte de la República Socialista Soviética de Ucrania antes de la restauración de la independencia de Ucrania . [66] La recién independizada Ucrania mantuvo el estatus autónomo de Crimea , [67] mientras que el Consejo Supremo de Crimea afirmó la "soberanía" de la península como parte de Ucrania. [68] [69]

El enfrentamiento entre el gobierno de Ucrania y Crimea se deterioró entre 1992 y 1995. En mayo de 1992, el parlamento regional declaró una "república de Crimea" independiente. [70] En junio de 1992, las partes llegaron a un compromiso, según el cual Crimea tendría una autonomía considerable pero seguiría siendo parte de Ucrania. [71] Yuri Meshkov , un líder del movimiento ruso, fue elegido presidente de Crimea en 1994 y su partido ganó la mayoría en las elecciones parlamentarias regionales del mismo año. El movimiento prorruso se vio debilitado por desacuerdos internos y en marzo de 1995 el gobierno ucraniano ganó la partida. El cargo de presidente electo de Crimea fue abolido y se instaló un jefe de región leal en lugar de Meshkov; la constitución de 1992 y varias leyes locales fueron derogadas. [70] Según Gwendolyn Sasse, el conflicto se desactivó debido a la población multiétnica de Crimea, las fracturas dentro del movimiento prorruso, la política de Kiev de evitar la escalada y la falta de apoyo activo de Rusia. [70]

Durante la década de 1990, la disputa por el control de la Flota del Mar Negro y las instalaciones navales de Crimea fueron fuente de tensiones entre Rusia y Ucrania. En 1992, Vladimir Lukin , entonces presidente del Comité de Asuntos Exteriores de la Duma rusa , sugirió que para presionar a Ucrania para que renunciara a su reclamo sobre la Flota del Mar Negro, Rusia debería cuestionar el control ucraniano sobre Crimea. [72] En 1998, el Tratado de Partición dividió la flota y le dio a Rusia una base naval en Sebastopol, y el Tratado de Amistad reconoció la inviolabilidad de las fronteras existentes. Sin embargo, en 2003 resurgieron los problemas del conflicto de la isla de Tuzla sobre la frontera marítima.

En septiembre de 2008, el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores de Ucrania, Volodymyr Ohryzko, acusó a Rusia de dar pasaportes rusos a la población de Crimea, y lo describió como un "problema real", dada la política declarada de Rusia de intervención militar en el extranjero para proteger a los ciudadanos rusos. [73]

El 24 de agosto de 2009, los residentes de etnia rusa realizaron manifestaciones antiucranianas en Crimea. Sergei Tsekov (del Bloque Ruso [74] y entonces vicepresidente del parlamento de Crimea [75] ) dijo entonces que esperaba que Rusia tratara a Crimea de la misma manera que había tratado a Osetia del Sur y Abjasia . [76] Crimea está poblada por una mayoría étnicamente rusa y una minoría tanto de ucranianos como de tártaros de Crimea, y por lo tanto posee demográficamente una de las poblaciones étnicamente rusas más grandes de Ucrania. [77]

En 2010, algunos analistas ya especulaban con la posibilidad de que el gobierno ruso tuviera planes irredentistas . Taras Kuzio afirmó que “Rusia tiene aún más dificultades para reconocer la soberanía de Ucrania sobre Crimea y el puerto de Sebastopol, como lo demuestra la opinión pública rusa, las declaraciones de políticos, incluidos los miembros del partido gobernante Rusia Unida, los expertos y los periodistas”. [78] En 2011, William Varettoni escribió que “Rusia quiere anexionarse Crimea y simplemente está esperando la oportunidad adecuada, probablemente con el pretexto de defender a sus hermanos rusos en el extranjero”. [79]

El movimiento de protesta Euromaidán comenzó en Kiev a finales de noviembre de 2013 después de que el presidente Viktor Yanukovych , del Partido de las Regiones , no firmara el Acuerdo de Asociación entre Ucrania y la Unión Europea . [80] Yanukovych ganó [81] las elecciones presidenciales de 2010 con un fuerte apoyo de los votantes de la República Autónoma de Crimea y el sur y este de Ucrania . El gobierno autónomo de Crimea apoyó firmemente a Yanukovych y condenó las protestas, diciendo que estaban "amenazando la estabilidad política en el país". El parlamento autónomo de Crimea dijo que apoyaba la decisión del gobierno de suspender las negociaciones sobre el acuerdo de asociación pendiente e instó a los crimeos a "fortalecer los lazos amistosos con las regiones rusas". [82] [83] [84]

El 4 de febrero de 2014, el Presidium del Consejo Supremo "prometió" considerar la posibilidad de celebrar un referéndum sobre el estatus de la península. El presidente Vladimir Klychnikov pidió que se apelara al gobierno ruso para "garantizar la preservación de la autonomía de Crimea". [85] [86] [¿ Importancia? ] El Servicio de Seguridad de Ucrania (SBU) respondió abriendo una causa penal para investigar la posible "subversión" de la integridad territorial de Ucrania. [87] El 20 de febrero de 2014, durante una visita a Moscú , el presidente del Consejo Supremo de Crimea, Vladimir Konstantinov, declaró que la transferencia de Crimea en 1954 de la República Socialista Federativa Soviética de Rusia a la República Socialista Soviética de Ucrania había sido un error. [85]

Las protestas de Euromaidán llegaron a su punto álgido a finales de febrero de 2014, y Yanukovych y muchos de sus ministros huyeron de la capital el 22 de febrero. [88] Tras su huida, los partidos de la oposición y los desertores del Partido de las Regiones reunieron un quórum parlamentario en la Verjovna Rada (el parlamento ucraniano) y votaron el 22 de febrero para destituir a Yanukovych de su cargo con el argumento de que no podía cumplir con sus obligaciones. [89] [90] [91] Arseniy Yatsenyuk fue designado por la Rada para servir como jefe de un gobierno provisional hasta que pudieran celebrarse nuevas elecciones presidenciales y parlamentarias. Este nuevo gobierno fue reconocido internacionalmente. El gobierno ruso y la propaganda han descrito estos acontecimientos como un " golpe de Estado " y han dicho que el gobierno interino era ilegítimo, [92] [93] [94] [95] mientras que los investigadores consideran que la posterior anexión de Crimea fue un verdadero golpe militar , porque el ejército ruso tomó el parlamento de Crimea y los edificios gubernamentales e instigó el reemplazo de su gobierno por representantes rusos. [96] [97] [98] [99] [100]

La Revolución de la Dignidad de febrero de 2014 , que derrocó al presidente ucraniano Viktor Yanukovych , desató una crisis política en Crimea, que inicialmente se manifestó en manifestaciones contra el nuevo gobierno interino ucraniano [101] , pero que rápidamente se intensificó. En enero de 2014, el ayuntamiento de Sebastopol ya había pedido la formación de unidades de "milicia popular" para "garantizar una defensa firme" de la ciudad contra el "extremismo". [102]

El 20 de febrero, varios autobuses con matrícula de Crimea fueron detenidos en un puesto de control pro-Maidan en una ciudad de la provincia de Cherkasy . Sus pasajeros fueron intimidados violentamente y algunos autobuses fueron quemados. Este incidente fue posteriormente utilizado por la propaganda rusa, que hizo afirmaciones sin fundamento de que los pasajeros habían sido asesinados de forma espantosa. [103]

Los miembros de la Verjovna Rada de Crimea convocaron una reunión extraordinaria para el 21 de febrero. En respuesta al sentimiento separatista ruso, el Servicio de Seguridad de Ucrania (SBU) dijo que "utilizaría medidas severas para evitar cualquier acción que menoscabe la integridad territorial y la soberanía de Ucrania". [nota 2] [ aclaración necesaria ] El partido con el mayor número de escaños en el parlamento de Crimea (80 de 100), el Partido de las Regiones del presidente ucraniano Viktor Yanukovych , no discutió la secesión de Crimea y apoyó un acuerdo entre el presidente Yanukovych [81] y los activistas de Euromaidán para poner fin a los disturbios que se produjeron el mismo día en Kiev . [105] [106]

Rusia estaba preocupada de que el nuevo gobierno, abiertamente comprometido con unas relaciones más estrechas con Occidente, pusiera en peligro sus posiciones estratégicas en Crimea. El 22 y 23 de febrero [nota 3] , el presidente ruso Vladimir Putin [107] convocó una reunión que duró toda la noche con los jefes de los servicios de seguridad para discutir la liberación del depuesto presidente ucraniano, Viktor Yanukovych, y al final de esa reunión Putin había señalado que "debemos empezar a trabajar para devolver Crimea a Rusia". [8] [9] Después de eso, el GRU y el FSB comenzaron a negociar acuerdos con simpatizantes locales para garantizar que cuando comenzara la operación hubiera "grupos de autodefensa locales" bien armados en las calles para brindar apoyo. [11] : 11 El 23 de febrero se celebraron manifestaciones prorrusas en la ciudad crimea de Sebastopol.

El primer ministro de Crimea, Anatolii Mohyliov, dijo que su gobierno reconocía al nuevo gobierno provisional en Kiev, y que el gobierno autónomo de Crimea llevaría a cabo todas las leyes aprobadas por el parlamento ucraniano. [108] En Simferopol , tras una manifestación prorrusa el día anterior en la que los manifestantes habían reemplazado la bandera ucraniana sobre el parlamento por una bandera rusa, [109] se celebró una manifestación pro-Euromaidán de entre 5.000 y 15.000 personas en apoyo del nuevo gobierno y exigiendo la dimisión del parlamento de Crimea; los asistentes ondearon banderas ucranianas, tártaras y de la Unión Europea. [110] Mientras tanto, en Sebastopol, miles protestaron contra el nuevo gobierno ucraniano, votaron a favor de establecer una administración paralela y crearon escuadrones de defensa civil con el apoyo del club de motociclistas rusos Night Wolves . Los manifestantes ondearon banderas rusas, corearon "¡Putin es nuestro presidente!" y dijeron que se negarían a pagar más impuestos al estado ucraniano. [111] [112] También se alega que se vieron convoyes militares rusos en la zona. [112]

En Kerch , manifestantes prorrusos intentaron retirar la bandera ucraniana de lo alto del ayuntamiento y reemplazarla con la bandera de Rusia. Más de 200 personas asistieron, ondeando banderas rusas, naranjas y negras de San Jorge y del partido Unidad Rusa . El alcalde Oleh Osadchy intentó dispersar a la multitud y la policía finalmente llegó para defender la bandera. El alcalde dijo "Este es el territorio de Ucrania, Crimea. Aquí hay una bandera de Crimea", pero fue acusado de traición y se produjo una pelea por el asta de la bandera. [113] El 24 de febrero, más manifestantes se manifestaron fuera de la administración de la ciudad-estado de Sebastopol. [114] Los manifestantes prorrusos acompañados por neocosacos exigieron la elección de un ciudadano ruso como alcalde e izaron banderas rusas alrededor de la administración de la ciudad; también repartieron folletos para inscribirse en una milicia de autodefensa, advirtiendo que "la Europlaga Azul - Parda está llamando a la puerta". [115]

Volodymyr Yatsuba , jefe de la administración de Sebastopol, anunció su renuncia, citando la "decisión de los habitantes de la ciudad" tomada en una manifestación prorrusa, y aunque la administración interina de la ciudad inicialmente se inclinó hacia el reconocimiento del nuevo gobierno ucraniano, [116] la presión continua de los activistas prorrusos obligó a las autoridades locales a ceder. [117] En consecuencia, el Ayuntamiento de Sebastopol eligió ilegalmente a Alexei Chaly , un ciudadano ruso, como alcalde. Según la ley de Ucrania, no era posible que Sebastopol eligiera un alcalde, ya que el presidente de la Administración Estatal de la Ciudad de Sebastopol , designado por el presidente de Ucrania , funciona como su alcalde. [118] Mil manifestantes presentes corearon "Un alcalde ruso para una ciudad rusa". [119]

El 25 de febrero, varios cientos de manifestantes prorrusos bloquearon el parlamento de Crimea exigiendo el no reconocimiento del gobierno central de Ucrania y un referéndum sobre el estatus de Crimea. [120] [121] [122] El mismo día, la multitud se reunió nuevamente afuera del ayuntamiento de Sebastopol el martes cuando se difundieron rumores de que las fuerzas de seguridad podrían arrestar a Chaly, pero el jefe de policía Alexander Goncharov dijo que sus oficiales se negarían a cumplir las "órdenes criminales" emitidas por Kiev. Viktor Neganov, un asesor del ministro del Interior con base en Sebastopol, condenó los eventos en la ciudad como un golpe de Estado. "Chaly representa los intereses del Kremlin, que probablemente dio su aprobación tácita", dijo. El presidente de la Administración Estatal de la Ciudad de Sebastopol, Vladimir Yatsuba, fue abucheado y molestado el 23 de febrero, cuando dijo en una manifestación prorrusa que Crimea era parte de Ucrania. Dimitió al día siguiente. [119] En Simferopol, el edificio de la Administración Estatal Regional fue bloqueado por cientos de manifestantes, incluidos neocosacos, que exigían un referéndum de separación; la manifestación fue organizada por el Frente de Crimea . [123]

El 26 de febrero, cerca del edificio de la Verjovna Rada de Crimea, entre 4.000 y 5.000 tártaros de Crimea y partidarios del movimiento Euromaidán -Crimea se enfrentaron a 600-700 partidarios de organizaciones prorrusas y del Partido de la Unidad Rusa . [124] Los líderes tártaros organizaron la manifestación para bloquear la sesión del parlamento de Crimea que está "haciendo todo lo posible para ejecutar los planes de separación de Crimea de Ucrania". [125] El presidente del Consejo Supremo, Vladimir Konstantinov, dijo que el parlamento de Crimea no consideraría la separación de Ucrania y que los informes anteriores de que el parlamento celebraría un debate sobre el asunto eran provocaciones. [126] [127] Los tártaros crearon grupos de autodefensa, alentaron la colaboración con rusos, ucranianos y personas de otras nacionalidades, y pidieron la protección de iglesias, mezquitas, sinagogas y otros lugares importantes. [128] Al anochecer, los tártaros de Crimea se habían ido; varios cientos de partidarios de la Unidad Rusa continuaron su marcha. [129]

El ministro de Asuntos Internos en funciones del nuevo gobierno ucraniano, Arsen Avakov, encargó a las fuerzas de seguridad de Crimea que no provocaran conflictos y que hicieran todo lo necesario para evitar enfrentamientos con las fuerzas prorrusas; y añadió: "Creo que de esa manera -a través del diálogo- lograremos mucho más que con enfrentamientos". [130] El nuevo jefe del Servicio de Seguridad de Ucrania (SBU) , Valentyn Nalyvaichenko, solicitó que las Naciones Unidas proporcionaran un seguimiento permanente de la situación de seguridad en Crimea. [131] Las tropas rusas tomaron el control de la ruta principal a Sebastopol por orden del presidente ruso Vladimir Putin . Se instaló un puesto de control militar, con una bandera rusa y vehículos militares rusos, en la carretera principal entre la ciudad y Simferopol . [132]

El 27 de febrero, fuerzas rusas sin identificar, en cooperación con paramilitares nacionalistas locales, tomaron la República Autónoma de Crimea y Sebastopol , y fuerzas especiales rusas [133] tomaron el edificio del Consejo Supremo de Crimea y el edificio del Consejo de Ministros en Simferopol . [134] Se izaron banderas rusas sobre estos edificios [135] y se erigieron barricadas en el exterior de ellos. [136] Las fuerzas prorrusas también ocuparon varias localidades en el óblast de Jersón en el istmo de Arabat , que geográficamente es parte de Crimea.

Mientras los " hombrecitos verdes " ocupaban el edificio del parlamento de Crimea, el parlamento celebró una sesión de emergencia. [137] [138] Votó para poner fin al gobierno de Crimea y reemplazar al primer ministro Anatolii Mohyliov por Sergey Aksyonov . [139] Aksyonov pertenecía al partido Unidad Rusa , que recibió el 4% de los votos en las últimas elecciones. [138] Según la Constitución de Ucrania , el primer ministro de Crimea es designado por el Consejo Supremo de Crimea en consulta con el presidente de Ucrania . [140] [141] Tanto Aksyonov como el presidente Vladimir Konstantinov declararon que consideraban a Viktor Yanukovych como el presidente de iure de Ucrania , a través del cual podían pedir ayuda a Rusia. [142]

El parlamento también votó a favor de celebrar un referéndum sobre una mayor autonomía, previsto para el 25 de mayo. Las tropas habían cortado todas las comunicaciones del edificio y se llevaron los teléfonos de los parlamentarios cuando entraron. [137] [138] No se permitió que los periodistas independientes entraran en el edificio mientras se celebraban las votaciones. [138] Algunos parlamentarios dijeron que estaban siendo amenazados y que se había emitido el voto por ellos y otros parlamentarios, aunque no estaban en la cámara. [138] Interfax-Ucrania informó de que "es imposible averiguar si todos los 64 miembros de la legislatura de 100 miembros que estaban registrados como presentes cuando se votaron las dos decisiones o si alguien más utilizó las tarjetas de votación de plástico de algunos de ellos", porque debido a la ocupación armada del parlamento no estaba claro cuántos parlamentarios estaban presentes. [143]

La jefa del departamento de información y análisis del parlamento, Olha Sulnikova, había llamado por teléfono desde el interior del edificio parlamentario a los periodistas y les había dicho que 61 de los 64 diputados registrados habían votado a favor de la resolución del referéndum y 55 a favor de la resolución de destituir al gobierno. [143] El separatista de la República Popular de Donetsk, Igor Girkin, dijo en enero de 2015 que los miembros del parlamento de Crimea fueron retenidos a punta de pistola y obligados a apoyar la anexión. [144] Estas acciones fueron inmediatamente declaradas ilegales por el gobierno interino ucraniano. [145]

Ese mismo día, más tropas con uniformes sin distintivos, asistidas esta vez por lo que parecía ser la policía antidisturbios local Berkut (así como por tropas rusas de la 31.ª Brigada de Asalto Aerotransportada Separada vestidas con uniformes Berkut), [146] establecieron puestos de control de seguridad en el istmo de Perekop y la península de Chonhar , que separan Crimea del continente ucraniano. [136] [147] [148] [149] [150] En cuestión de horas, Ucrania había quedado aislada de Crimea. Poco después, los canales de televisión ucranianos dejaron de estar disponibles para los espectadores crimeos, y algunos de ellos fueron reemplazados por estaciones rusas.

El 1 de marzo de 2014, Aksyonov dijo que ejercería el control de todas las instalaciones militares y de seguridad ucranianas en la península. También pidió a Putin "asistencia para garantizar la paz y la tranquilidad" en Crimea. [151] Putin recibió rápidamente la autorización del Consejo de la Federación de Rusia para una intervención militar rusa en Ucrania hasta que "la situación política y social en el país se normalice". [152] [153] La rápida maniobra de Putin provocó protestas de algunos intelectuales rusos y manifestaciones en Moscú contra una campaña militar rusa en Crimea. El 2 de marzo, las tropas rusas que se desplazaban desde la base naval del país en Sebastopol y eran reforzadas por tropas, blindados y helicópteros de la Rusia continental ejercían un control completo sobre la península de Crimea. [154] [155] [156] Las tropas rusas operaron en Crimea sin insignias. El 3 de marzo bloquearon la Base Naval del Sur .

El 4 de marzo, el Estado Mayor ucraniano dijo que había unidades de la 18.ª Brigada de Fusileros Motorizados , la 31.ª Brigada de Asalto Aéreo y la 22.ª Brigada Spetsnaz desplegadas y operando en Crimea, en lugar de personal de la Flota del Mar Negro rusa , lo que violaba los acuerdos internacionales firmados por Ucrania y Rusia. [157] [158] En una conferencia de prensa el mismo día, el presidente ruso Vladimir Putin dijo que Rusia no tenía planes de anexionarse Crimea. [159] También dijo que no tenía planes de invadir Ucrania, pero que podría intervenir si los rusos en Ucrania se veían amenazados. [159] Esto fue parte de un patrón de negaciones públicas de la operación militar rusa en curso. [159]

Numerosos informes de prensa y declaraciones de los gobiernos ucraniano y extranjero señalaron la identidad de las tropas sin identificación como soldados rusos, pero los funcionarios rusos ocultaron la identidad de sus fuerzas, afirmando que eran unidades locales de "autodefensa" sobre las que no tenían autoridad. [38] Tan tarde como el 17 de abril, el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores ruso, Serguéi Lavrov, dijo que no había "tropas rusas excesivas" en Ucrania. [160] En la misma conferencia de prensa, Putin dijo sobre la península que "sólo los propios ciudadanos, en condiciones de libre expresión de voluntad y su seguridad pueden determinar su futuro". [161] Putin reconoció más tarde que había ordenado "trabajar para devolver Crimea a Rusia" ya en febrero. [39] También reconoció que a principios de marzo se celebraron "encuestas de opinión secretas" en Crimea, que, según él, informaron de un apoyo popular abrumador a la incorporación de Crimea a Rusia. [162]

Rusia finalmente admitió la presencia de sus tropas. [163] El ministro de Defensa, Sergey Shoygu, dijo que las acciones militares del país en Crimea fueron realizadas por fuerzas de la Flota del Mar Negro y estaban justificadas por la "amenaza a las vidas de los civiles de Crimea " y el peligro de "toma de control de la infraestructura militar rusa por extremistas ". [164] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ] Ucrania se quejó de que al aumentar su presencia de tropas en Crimea, Rusia violó el acuerdo bajo el cual estableció su sede de la Flota del Mar Negro en Sebastopol [165] y violó la soberanía del país . [166] Estados Unidos y el Reino Unido acusaron a Rusia de romper los términos del Memorando de Budapest sobre Garantías de Seguridad , por el cual Rusia, Estados Unidos y el Reino Unido habían reafirmado su obligación de abstenerse de la amenaza o el uso de la fuerza contra la integridad territorial o la independencia política de Ucrania. [167] El gobierno ruso dijo que el Memorando de Budapest [168] no se aplicaba debido a "circunstancias resultantes de la acción de factores políticos o socioeconómicos internos". [169] En marzo de 2015, el almirante retirado ruso Igor Kasatonov declaró que, según su información, el despliegue de tropas rusas en Crimea incluyó seis desembarcos de helicópteros y tres desembarcos de un IL-76 con 500 personas. [170] [171]

Las obligaciones entre Rusia y Ucrania en materia de integridad territorial y la prohibición del uso de la fuerza están establecidas en una serie de acuerdos multilaterales o bilaterales de los que Rusia y Ucrania son signatarios. [172] [173] [167] [174]

Vladimir Putin dijo que las tropas rusas en la península de Crimea tenían como objetivo "garantizar las condiciones adecuadas para que el pueblo de Crimea pueda expresar libremente su voluntad", [175] mientras que Ucrania y otras naciones argumentan que dicha intervención es una violación de la soberanía de Ucrania . [166]

En el Memorándum de Budapest sobre Garantías de Seguridad de 1994 [168] Rusia estuvo entre los que afirmaron respetar la integridad territorial de Ucrania (incluida Crimea) y abstenerse de la amenaza o el uso de la fuerza contra la integridad territorial o la independencia política de Ucrania. [167] [174] El Tratado de Amistad entre Rusia y Ucrania de 1997,[176] La cooperación y la asociación reafirmaron nuevamente la inviolabilidad de las fronteras entre ambos estados, [174] y exigieron a las fuerzas rusas en Crimea que respeten la soberanía de Ucrania, honren su legislación y no interfieran en los asuntos internos del país. [177]

El Tratado de Partición ruso-ucraniano sobre el estatuto y las condiciones de la Flota del Mar Negro, firmado en 1997 y prorrogado en 2010, determinó el estatuto de la presencia militar rusa en Crimea y restringió sus operaciones [174], incluido el requisito de mostrar sus "tarjetas de identificación militar" al cruzar la frontera internacional y que las operaciones más allá de los sitios de despliegue designados se permitieran solo después de la coordinación con Ucrania. [177] Según Ucrania, el uso de estaciones de navegación y los movimientos de tropas estaban cubiertos indebidamente por el tratado y fueron violados muchas veces, así como las decisiones judiciales relacionadas. Los movimientos de tropas de febrero se realizaron en "total desprecio" del tratado. [178] [nota 4]

Según la Constitución de Rusia, la admisión de nuevos sujetos federales se rige por la ley constitucional federal (art. 65.2). [180] Esta ley, aprobada en 2001, establece que la admisión de un Estado extranjero o de una parte de él en Rusia se basará en un acuerdo mutuo entre la Federación Rusa y el Estado en cuestión y se llevará a cabo de conformidad con un tratado internacional entre los dos países; además, debe ser iniciada por el Estado en cuestión, no por su subdivisión o por Rusia. [181]

El 28 de febrero de 2014, el diputado ruso Serguéi Mironov , junto con otros miembros de la Duma, presentó un proyecto de ley para modificar el procedimiento de Rusia para la incorporación de sujetos federales. Según el proyecto de ley, la adhesión podría ser iniciada por una subdivisión de un país, siempre que haya "ausencia de un gobierno estatal soberano eficiente en un estado extranjero"; la solicitud podría ser presentada por los órganos de la subdivisión por sí mismos o sobre la base de un referéndum celebrado en la subdivisión de conformidad con la legislación nacional correspondiente. [182]

El 11 de marzo de 2014, tanto el Consejo Supremo de Crimea como el Ayuntamiento de Sebastopol adoptaron una declaración de independencia , en la que se manifestaba su intención de declarar la independencia y solicitar la adhesión total a Rusia si la opción prorrusa recibía la mayoría de los votos durante el referéndum programado sobre el estatus. La declaración se refería directamente al precedente de independencia de Kosovo , por el cual la Provincia Autónoma de Kosovo y Metohija, de población albanesa , declaró su independencia del aliado de Rusia, Serbia, como la República de Kosovo en 2008, una acción unilateral a la que Rusia se opuso firmemente . El gobierno ruso utilizó el precedente de la independencia de Kosovo como justificación legal para la anexión de Crimea [183] [184] [185] [186] Muchos analistas vieron la declaración de Crimea como un esfuerzo abierto para allanar el camino para la anexión de Crimea por parte de Rusia [187] y rechazaron la justificación del precedente de Kosovo por parte de Rusia por ser diferente en comparación con los eventos de Crimea, [188] [189] comparando la anexión con el anschluss de Austria y los Sudetes checoslovacos por parte de la Alemania nazi . [ 190 ] [ 191]

Los planes declarados por las autoridades de Crimea de declarar la independencia de Ucrania hicieron innecesaria la ley Mironov. El 20 de marzo de 2014, dos días después de la firma del tratado de adhesión, el proyecto de ley fue retirado por sus promotores. [192] [ se necesita una fuente no primaria ]

En su reunión de los días 21 y 22 de marzo, la Comisión de Venecia del Consejo de Europa declaró que el proyecto de ley Mironov violaba "en particular, los principios de integridad territorial, soberanía nacional, no intervención en los asuntos internos de otro Estado y pacta sunt servanda " y, por lo tanto, era incompatible con el derecho internacional . [193] [194]

El 27 de febrero de 2014, tras la toma de su edificio y la sustitución de los funcionarios electos ucranianos por actores controlados por Rusia por fuerzas especiales rusas, [195] el Consejo Supremo de Crimea votó a favor de celebrar un referéndum el 25 de mayo, con la pregunta inicial de si Crimea debería mejorar su autonomía dentro de Ucrania. [196] [ se necesita una fuente no primaria ] La fecha del referéndum se trasladó posteriormente del 25 de mayo al 30 de marzo. [197] Un tribunal ucraniano declaró que el referéndum era ilegal. [198]

El 6 de marzo, el Consejo Supremo trasladó la fecha del referéndum al 16 de marzo y modificó su alcance para plantear una nueva cuestión: si Crimea debería solicitar unirse a Rusia como sujeto federal o restablecer la constitución de Crimea de 1992 dentro de Ucrania, que el gobierno ucraniano había invalidado previamente. Este referéndum, a diferencia de uno anunciado anteriormente, no contenía ninguna opción para mantener el statu quo de gobierno bajo la constitución de 1998. [199] El presidente interino de Ucrania, Oleksandr Turchynov , declaró que "Las autoridades de Crimea son totalmente ilegítimas, tanto el parlamento como el gobierno. Se ven obligadas a trabajar bajo el cañón de una pistola y todas sus decisiones están dictadas por el miedo y son ilegales". [200]

El 14 de marzo, el Tribunal Constitucional de Ucrania consideró inconstitucional el referéndum sobre el estatuto de Crimea [201] y, un día después, la Verjovna Rada disolvió formalmente el parlamento de Crimea [ 41] . Ante la inminente celebración de un referéndum, Rusia concentró tropas cerca de la frontera oriental de Ucrania [202] , probablemente para amenazar con una escalada y obstaculizar la respuesta de Ucrania.

El referéndum se celebró a pesar de la oposición del gobierno ucraniano. Los resultados oficiales informaron que alrededor del 95,5% de los votantes participantes en Crimea (la participación fue del 83%) estaban a favor de separarse de Ucrania y unirse a Rusia. [49] [203] [204] La mayoría de los tártaros de Crimea boicotearon el referéndum. [205] Un informe de Evgeny Bobrov, miembro del Consejo de Derechos Humanos del Presidente ruso , sugirió que los resultados oficiales estaban inflados y que entre el 50 y el 60% de los crimeos votaron por la reunificación con Rusia, con una participación del 30-50%, lo que significa que entre el 15% y el 30% de los crimeos con derecho a voto votaron por la anexión rusa (el apoyo fue mayor en Sebastopol, administrativamente separada). [195] [40] [206] [207] Según una encuesta realizada por Pew Research Center en 2014, el 54% de los residentes de Crimea apoyaban el derecho de las regiones a separarse, el 91% creía que el referéndum fue libre y justo y el 88% creía que el gobierno de Kiev debería reconocer los resultados de la votación. [208]

Los medios por los cuales se llevó a cabo el referéndum fueron ampliamente criticados por los gobiernos extranjeros [209] y en la prensa ucraniana e internacional, con informes de que cualquier persona con pasaporte ruso, independientemente de su residencia en Crimea, pudo votar. [210] La OSCE se negó a enviar observadores al referéndum, afirmando que la invitación debería haber venido de un estado miembro de la OSCE en cuestión (es decir, Ucrania), en lugar de las autoridades locales. [211] Rusia invitó a un grupo de observadores de varios partidos políticos europeos de extrema derecha alineados con Putin, quienes declararon que el referéndum se llevó a cabo de manera libre y justa. [212] [213]

La República de Crimea duró poco. El 17 de marzo, tras el anuncio oficial de los resultados del referéndum , el Consejo Supremo de Crimea declaró la independencia formal de la República de Crimea, que comprendía los territorios tanto de la República Autónoma de Crimea como de la ciudad de Sebastopol , a la que se le concedió un estatus especial dentro de la república separatista. [214] El parlamento de Crimea declaró la "derogación parcial" de las leyes ucranianas y comenzó a nacionalizar la propiedad privada y estatal ucraniana ubicada en la península de Crimea, incluidos los puertos ucranianos [215] y la propiedad de Chornomornaftogaz . [216] El parlamento también solicitó formalmente que el gobierno ruso admitiera a la república separatista en Rusia, [217] y Sebastopol pidió ser admitida como una "ciudad de importancia federal". [218] El mismo día, el Consejo Supremo de facto se rebautizó como Consejo Estatal de Crimea , [219] declaró el rublo ruso como moneda oficial junto con la grivna , [220] y en junio el rublo ruso se convirtió en la única forma de curso legal. [221]

Putin reconoció oficialmente a la República de Crimea «como un estado soberano e independiente» mediante decreto del 17 de marzo. [222] [223]

El 21 de marzo la República de Crimea se convirtió en un sujeto federal de Rusia.

El Tratado de Adhesión de la República de Crimea a Rusia fue firmado entre representantes de la República de Crimea (incluida Sebastopol, con la que el resto de Crimea se unificó brevemente) y la Federación Rusa el 18 de marzo de 2014 para establecer los términos para la admisión inmediata de la República de Crimea y Sebastopol como sujetos federales de Rusia y parte de la Federación Rusa. [224] [225] [nota 5] El 19 de marzo, el Tribunal Constitucional ruso decidió que el tratado cumple con la Constitución de Rusia. [227] El tratado fue ratificado por la Asamblea Federal y el Consejo de la Federación el 21 de marzo. [228] Ilya Ponomarev de Una Rusia Justa fue el único miembro de la Duma Estatal que votó en contra del tratado. [229] La República de Crimea y la ciudad federal de Sebastopol se convirtieron en los 84.º y 85.º sujetos federales de Rusia . [230]

Durante un incidente controvertido ocurrido en Simferopol el 18 de marzo, algunas fuentes ucranianas afirmaron que hombres armados que, según se informó, pertenecían a fuerzas especiales rusas supuestamente irrumpieron en la base. Esto fue desmentido por las autoridades rusas, que posteriormente anunciaron la detención de un presunto francotirador ucraniano en relación con los asesinatos [231] , pero luego negaron que se hubiera producido la detención [232] .

Las dos víctimas tuvieron un funeral conjunto al que asistieron las autoridades de Crimea y Ucrania, y tanto el soldado ucraniano como el "voluntario de autodefensa" paramilitar ruso fueron llorados juntos. [233] En marzo de 2014, el incidente estaba siendo investigado tanto por las autoridades de Crimea como por el ejército ucraniano. [234] [235]

En respuesta a los disparos, el entonces ministro de defensa de Ucrania, Igor Tenyukh, autorizó a las tropas ucranianas estacionadas en Crimea a utilizar la fuerza letal en situaciones que pusieran en peligro la vida. Esto aumentó el riesgo de derramamiento de sangre durante cualquier toma de instalaciones militares ucranianas, pero las operaciones rusas posteriores para apoderarse de las bases militares y los barcos ucranianos restantes en Crimea no provocaron nuevas muertes, aunque se utilizaron armas y varias personas resultaron heridas. Las unidades rusas que participaron en tales operaciones recibieron órdenes de evitar el uso de la fuerza letal cuando fuera posible. La moral entre las tropas ucranianas, que durante tres semanas estuvieron bloqueadas dentro de sus recintos sin ninguna ayuda del gobierno ucraniano, era muy baja, y la gran mayoría de ellas no ofrecieron ninguna resistencia real. [236]

El 24 de marzo, el gobierno ucraniano ordenó la retirada total de todas sus fuerzas armadas de Crimea. [237] Aproximadamente el 50% de los soldados ucranianos en Crimea habían desertado al ejército ruso. [238] [239] El 26 de marzo, las últimas bases militares ucranianas y los barcos de la Armada ucraniana fueron capturados por tropas rusas . [240]

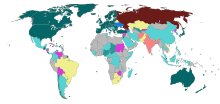

El 27 de marzo, la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas adoptó una resolución no vinculante que declaró inválido el referéndum de Crimea y el cambio de estatus posterior, por 100 votos a favor y 11 en contra, con 58 abstenciones y 24 ausentes. [241] [242]

Crimea y Sebastopol cambiaron a la hora de Moscú a las 22 horas del 29 de marzo. [243] [244]

El 31 de marzo, Rusia denunció unilateralmente el Pacto de Járkov [245] y el Tratado de Partición sobre el Estatuto y las Condiciones de la Flota del Mar Negro . [246] Putin citó "la adhesión de la República de Crimea y Sebastopol a Rusia" y el "fin práctico de las relaciones de arrendamiento " resultante como su razón para la denuncia. [247] El mismo día, firmó un decreto que rehabilitaba formalmente a los tártaros de Crimea , que fueron expulsados de sus tierras en 1944, y a las comunidades minoritarias armenia, alemana, griega y búlgara de la región que Stalin también ordenó eliminar en la década de 1940.

También el 31 de marzo de 2014, el primer ministro ruso , Dmitri Medvédev, anunció una serie de programas destinados a incorporar rápidamente el territorio de Crimea a la economía y la infraestructura de Rusia . Medvédev anunció la creación de un nuevo ministerio para asuntos de Crimea y ordenó a los principales ministros de Rusia que se unieron a él allí que hicieran de la elaboración de un plan de desarrollo su máxima prioridad. [248] El 3 de abril de 2014, la República de Crimea y la ciudad de Sebastopol pasaron a formar parte del Distrito Militar del Sur de Rusia . [ cita requerida ] El 7 de mayo de 2015, Crimea cambió su sistema de código telefónico del sistema numérico ucraniano al sistema numérico ruso . [249]

El 11 de abril, la Constitución de la República de Crimea y la Carta de la Ciudad de Sebastopol fueron aprobadas por sus respectivas legislaturas, [250] [251] entrando en vigor al día siguiente; además, los nuevos sujetos federales fueron enumerados en una revisión recién publicada de la Constitución rusa. [252] [253]

El 14 de abril, Vladimir Putin anunció que abriría una cuenta sólo en rublos en el Banco Rossiya y lo convertiría en el banco principal en la recién anexada Crimea, además de darle el derecho a realizar pagos en el mercado mayorista de electricidad de Rusia, valuado en 36 mil millones de dólares, lo que le proporcionó al banco 112 millones de dólares anuales sólo en comisiones. [254]

Rusia retiró sus fuerzas del sur de Jersón en diciembre de 2014. [255]

En julio de 2015, el primer ministro ruso, Dmitri Medvédev , declaró que Crimea había sido plenamente integrada en Rusia. [256] Hasta 2016, estos nuevos sujetos estaban agrupados en el Distrito Federal de Crimea .

El 8 de agosto de 2016, Ucrania informó que Rusia había aumentado su presencia militar a lo largo de la línea de demarcación. [257] En respuesta a esta acumulación militar, Ucrania también desplegó más tropas y recursos más cerca de la frontera con Crimea. [258] El Pentágono ha restado importancia a una invasión rusa de Ucrania, calificando a las tropas rusas a lo largo de la frontera como un ejercicio militar regular. [259] El 10 de agosto, Rusia afirmó que dos militares murieron en enfrentamientos con comandos ucranianos, y que militares ucranianos habían sido capturados con un total de 40 kg de explosivos en su posesión. [260] Ucrania negó que el incidente hubiera tenido lugar. [261]

Según fuentes rusas, el FSB ruso detuvo a "saboteadores ucranianos" y "terroristas" cerca de Armiansk. El tiroteo que siguió dejó un oficial del FSB y un sospechoso muertos. Varias personas fueron detenidas, entre ellas Yevhen Panov, a quien las fuentes rusas describen como un oficial de inteligencia militar ucraniano y líder del grupo de sabotaje. El grupo supuestamente estaba planeando ataques terroristas contra infraestructura importante en Armiansk, Crimea. [262] [263]

Los medios de comunicación ucranianos informaron de que Panov era un voluntario militar que luchaba en el este del país, aunque más recientemente se le ha asociado con una organización benéfica. Rusia también afirmó que la supuesta infiltración fronteriza estuvo acompañada de "fuego intenso" desde territorio ucraniano, lo que resultó en la muerte de un soldado ruso. [262] [263] El gobierno ucraniano calificó las acusaciones rusas de "cínicas" y "sin sentido" y argumentó que, dado que Crimea era territorio ucraniano, era Rusia la que "ha estado financiando generosamente y apoyando activamente el terrorismo en territorio ucraniano". [264]

En 2017, una encuesta realizada por el Centro de Estudios de Europa del Este e Internacionales mostró que el 85% de los encuestados tártaros no crimeos creían que, si se celebraba de nuevo el referéndum, los resultados serían los mismos o "sólo marginalmente diferentes". Crimea estaba plenamente integrada en la esfera mediática rusa y los vínculos con el resto de Ucrania eran prácticamente inexistentes. [265] [266]

El 26 de noviembre de 2018, los legisladores del Parlamento de Ucrania apoyaron por abrumadora mayoría la imposición de la ley marcial en las regiones costeras de Ucrania y en las que limitan con Rusia en respuesta a los disparos y la captura de buques de guerra ucranianos por parte de Rusia cerca de la península de Crimea un día antes. Un total de 276 legisladores en Kiev respaldaron la medida, que entró en vigor el 28 de noviembre de 2018 y finalizó el 26 de diciembre. [267] [268]

El 28 de diciembre de 2018, Rusia completó una valla de seguridad de alta tecnología que marca la frontera de facto entre Crimea y Ucrania. [269]

En 2021, Ucrania lanzó la Plataforma de Crimea , una iniciativa diplomática destinada a proteger los derechos de los habitantes de Crimea y, en última instancia, revertir la anexión de Crimea. [270]

Inicialmente, después de la anexión, los salarios aumentaron, especialmente los de los empleados del gobierno [ cita requerida ] . Esto pronto fue compensado por el aumento de los precios causado por la depreciación del rublo . Los salarios se redujeron entre un 30% y un 70% después de que se estableciera la autoridad rusa [ cita requerida ] . El turismo, anteriormente la principal industria de Crimea, sufrió en particular, cayendo un 50% desde 2014 en 2015. [271] [272] Los rendimientos agrícolas de Crimea también se vieron significativamente afectados por la anexión [ cita requerida ] . Ucrania cortó los suministros de agua a través del Canal del Norte de Crimea , que suministra el 85% del agua dulce de Crimea, [ verificación fallida ] causando que la cosecha de arroz de 2014 fracasara y dañando en gran medida los cultivos de maíz y soja . [273] La anexión tuvo una influencia negativa en los rusos que trabajaban en Ucrania y los ucranianos que trabajaban en Rusia. [274]

El número de turistas que visitaron Crimea en la temporada 2014 fue menor que en los años anteriores debido a una combinación de "sanciones occidentales", objeciones éticas de los ucranianos y la dificultad de llegar allí para los rusos. [275] El gobierno ruso intentó estimular el flujo de turistas subvencionando vacaciones en la península para niños y empleados estatales de toda Rusia [276] [277] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ] que funcionó principalmente para los hoteles estatales. En 2015, un total de 3 millones de turistas visitaron Crimea según datos oficiales, mientras que antes de la anexión eran alrededor de 5,5 millones en promedio. La escasez se atribuye principalmente a la interrupción del flujo de turistas desde Ucrania. Los hoteles y restaurantes también están experimentando problemas para encontrar suficientes trabajadores temporeros, que en los años anteriores llegaban en su mayoría desde Ucrania. Los turistas que visitaban hoteles estatales se quejaban principalmente del bajo nivel de las habitaciones e instalaciones, algunas de ellas aún sin reparar desde la época soviética. [278]

Según el periódico alemán Die Welt , la anexión de Crimea es económicamente desventajosa para la Federación Rusa. Rusia tendrá que gastar miles de millones de euros al año para pagar salarios y pensiones. Además, Rusia tendrá que emprender proyectos costosos para conectar Crimea al sistema de suministro de agua y energía rusos porque Crimea no tiene conexión terrestre con Rusia y en la actualidad (2014) obtiene agua, gas y electricidad de Ucrania continental. Esto requirió la construcción de un puente y un gasoducto a través del estrecho de Kerch . Además, Novinite afirma que un experto ucraniano le dijo a Die Welt que Crimea "no podrá atraer turistas". [279]

La entonces primera viceministra de Finanzas de la Federación Rusa, Tatiana Nesterenko, dijo que la decisión de anexar Crimea fue tomada exclusivamente por Vladimir Putin, sin consultar al Ministerio de Finanzas de Rusia. [280]

El periódico económico ruso Kommersant opina que Rusia no obtendrá ningún beneficio económico de la "entrada" a Crimea, que no está muy desarrollada industrialmente, tiene sólo unas pocas grandes fábricas y cuyo producto bruto anual es de sólo 4.000 millones de dólares . El periódico también afirma que todo lo que llegue de Rusia tendrá que ser traído por mar, que el aumento de los costes de transporte se traducirá en un aumento de los precios de todo y que, para evitar un descenso del nivel de vida, Rusia tendrá que subvencionar a la población de Crimea durante unos meses. En total, Kommersant estima que el coste de la integración de Crimea a Rusia será de 30.000 millones de dólares durante la próxima década, es decir, 3.000 millones de dólares al año. [281]

Los expertos occidentales en petróleo [¿ quiénes? ] estiman que la toma de Crimea por parte de Rusia, y el control asociado de un área del Mar Negro más de tres veces su superficie terrestre, le da acceso a reservas de petróleo y gas que potencialmente valen billones de dólares. [282] También priva a Ucrania de sus posibilidades de independencia energética. La adquisición de Moscú puede alterar la ruta a lo largo de la cual se construiría el gasoducto South Stream , ahorrándole a Rusia dinero, tiempo y desafíos de ingeniería [ cita requerida ] . También permitiría a Rusia evitar construir en aguas territoriales turcas, lo cual era necesario en la ruta original para evitar el territorio ucraniano. [283] Sin embargo, este gasoducto fue cancelado más tarde a favor de TurkStream .

_01.jpg/440px-Opening_of_the_Crimean_bridge_(2018-05-15)_01.jpg)

El Servicio Federal Ruso de Comunicaciones (Roskomnadzor) advirtió sobre un período de transición ya que los operadores rusos tienen que cambiar la capacidad de numeración y los suscriptores. El código del país será reemplazado del ucraniano +380 al ruso +7 . Los códigos en Crimea comienzan con 65 , pero en la zona "7" el 6 se le da a Kazajstán que comparte la antigua Unión Soviética +7 con Rusia, por lo que los códigos de ciudad tienen que cambiar. El regulador asignó el código de marcación 869 a Sebastopol y el resto de la península recibió un código 365. [284] En el momento de la unificación con Rusia, los operadores telefónicos y los proveedores de servicios de Internet en Crimea y Sebastopol están conectados al mundo exterior a través del territorio de Ucrania. [285] El ministro de Comunicaciones de Rusia, Nikolai Nikiforov, anunció en su cuenta de Twitter que los códigos postales en Crimea ahora tendrán seis cifras: al número de cinco dígitos existente se agregará el número dos al principio. Por ejemplo, el código postal de Simferopol 95000 pasará a ser 295000. [286]

En la zona que hoy forma la frontera entre Crimea y Ucrania se extrajeron del mar los lagos salados que constituyen las fronteras naturales, y en la lengua de tierra que quedó se crearon extensiones de tierra de nadie con alambres a ambos lados. [287] A principios de junio de ese año, el Primer Ministro Dmitry Medvedev firmó una resolución gubernamental No. 961 [288] de fecha 5 de junio de 2014 por la que se establecían puestos de control aéreos, marítimos, por carretera y por ferrocarril. Las decisiones adoptadas crean una base jurídica para el funcionamiento de un sistema de puestos de control en la frontera estatal rusa en la República de Crimea y Sebastopol. [289] [ fuente de terceros necesaria ]

En el año siguiente a la anexión, hombres armados tomaron posesión de varios negocios de Crimea, incluidos bancos, hoteles, astilleros, granjas, gasolineras, una panadería , una lechería y el estudio cinematográfico Yalta. [290] [291] [292] Los medios rusos han señalado esta tendencia como un "regreso a los años 90", que se percibe como un período de anarquía y gobierno de pandillas en Rusia. [293]

Después de 2014, el gobierno ruso realizó fuertes inversiones en la infraestructura de la península: reparó carreteras, modernizó hospitales y construyó el puente de Crimea que une la península con el continente ruso. Se emprendió el desarrollo de nuevas fuentes de agua, con enormes dificultades, para reemplazar las fuentes ucranianas cerradas. [294] En 2015, el Comité de Investigación de Rusia anunció una serie de casos de robo y corrupción en proyectos de infraestructura en Crimea, por ejemplo, gastos que excedieron los costos reales contabilizados por un factor de tres. Varios funcionarios rusos también fueron arrestados por corrupción, incluido el jefe de la inspección fiscal federal. [295]

(Según cifras oficiales ucranianas de febrero de 2016), después de la anexión de Crimea por parte de Rusia, el 10% del personal del Servicio de Seguridad de Ucrania abandonó Crimea, acompañado por 6.000 de los 20.300 efectivos del ejército ucraniano anterior a la anexión . [296]

Como consecuencia del controvertido estatus político de Crimea, los operadores móviles rusos nunca ampliaron sus operaciones en Crimea y todos los servicios móviles se ofrecen sobre la base de "roaming interno", lo que provocó una gran controversia dentro de Rusia. Sin embargo, las empresas de telecomunicaciones argumentaron que ampliar la cobertura a Crimea las pondría en riesgo de sanciones occidentales y, como resultado, perderían el acceso a equipos y software clave, ninguno de los cuales se produce localmente. [297] [298]

Los primeros cinco años de ocupación de Crimea le costaron a Rusia más de 20.000 millones de dólares, aproximadamente el equivalente a dos años de todo el presupuesto de educación de Rusia. [299]

Según las Naciones Unidas y varias ONG, Rusia es responsable de múltiples abusos de los derechos humanos , incluida la tortura, la detención arbitraria, las desapariciones forzadas y los casos de discriminación, incluida la persecución de los tártaros de Crimea en Crimea desde la anexión ilegal. [300] [301] La Oficina de Derechos Humanos de la ONU ha documentado múltiples violaciones de los derechos humanos en Crimea, señalando que la minoría tártara de Crimea se ha visto afectada desproporcionadamente. [302] [303] En diciembre de 2016, la Asamblea General de la ONU votó una resolución sobre los derechos humanos en la Crimea ocupada. Instó a la Federación de Rusia "a adoptar todas las medidas necesarias para poner fin de inmediato a todos los abusos contra los residentes de Crimea, en particular las medidas y prácticas discriminatorias denunciadas, las detenciones arbitrarias, la tortura y otros tratos crueles, inhumanos o degradantes, y a revocar toda la legislación discriminatoria". También instó a Rusia a "liberar de inmediato a los ciudadanos ucranianos que fueron detenidos ilegalmente y juzgados sin tener en cuenta las normas elementales de justicia". [304]

Tras la anexión, las autoridades rusas prohibieron las organizaciones tártaras de Crimea, presentaron cargos penales contra los dirigentes y periodistas tártaros y atacaron a la población tártara. El Atlantic Council ha descrito esto como una práctica de castigo colectivo y, por lo tanto, como un crimen de guerra prohibido por el derecho internacional humanitario y la Convención de Ginebra . [305] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ]

En marzo de 2014, Human Rights Watch informó que activistas y periodistas pro-ucranianos habían sido atacados, secuestrados y torturados por grupos de "autodefensa". [306] Algunos crimeos simplemente fueron "desaparecidos" sin explicación alguna. [307]

El 9 de mayo de 2014 entró en vigor la nueva enmienda " antiextremista " del Código Penal de Rusia , aprobada en diciembre de 2013. El artículo 280.1 tipifica como delito en Rusia la incitación a violar la integridad territorial de la Federación Rusa [308] (incluidos los llamamientos a la secesión de Crimea de Rusia [309] ), punible con una multa de 300 mil rublos o prisión de hasta 3 años. Si tales declaraciones se hacen en los medios de comunicación públicos o en Internet, la pena puede ser trabajos forzados de hasta 480 horas o prisión de hasta cinco años. [308]

Según un informe publicado en el sitio web del Presidente del Consejo de Rusia sobre Sociedad Civil y Derechos Humanos, dirigido por el gobierno ruso, los tártaros que se oponían al gobierno ruso han sido perseguidos, se ha impuesto una ley rusa que restringe la libertad de expresión y las nuevas autoridades rusas "liquidaron" la iglesia ortodoxa del Patriarcado de Kiev en la península. [310] [40] La estación de televisión tártara de Crimea también fue clausurada por las autoridades rusas. [307]

El 16 de mayo, las nuevas autoridades rusas de Crimea prohibieron las conmemoraciones anuales del aniversario de la deportación de los tártaros de Crimea por Stalin en 1944, citando como motivo la "posibilidad de provocación por parte de extremistas". [311] Anteriormente, cuando Crimea estaba controlada por Ucrania, estas conmemoraciones se habían celebrado todos los años. Las autoridades de Crimea instaladas por Rusia también prohibieron la entrada a Crimea a Mustafa Dzhemilev , activista de derechos humanos, disidente soviético, miembro del parlamento ucraniano y ex presidente del Mejlis de los tártaros de Crimea. [312] Además, el Mejlis informó de que agentes del Servicio Federal de Seguridad de Rusia (FSB) allanaron viviendas tártaras esa misma semana, con el pretexto de "sospecha de actividad terrorista". [313] La comunidad tártara acabó celebrando manifestaciones conmemorativas desafiando la prohibición. [312] [313] En respuesta, las autoridades rusas volaron helicópteros sobre las manifestaciones en un intento de dispersarlas. [314]

En mayo de 2015, un activista local, Alexander Kostenko, fue condenado a cuatro años de prisión en una colonia penal. Su abogado, Dmitry Sotnikov, dijo que el caso era falso y que su cliente había sido golpeado y privado de comida. La fiscal de Crimea, Natalia Poklonskaya, acusó a Kostenko de hacer gestos nazis durante las protestas de Maidán y que estaban juzgando "no sólo [a Kostenko], sino la idea misma del fascismo y el nazismo, que están tratando de levantar cabeza una vez más". Sotnikov respondió que "hay casos falsos en Rusia, pero rara vez tanta humillación y daño físico. Se está torturando a una persona viva por una idea política, para poder jactarse de haber vencido al fascismo". [315] En junio de 2015, Razom publicó un informe que recopilaba los abusos de los derechos humanos en Crimea. [316] [317] En su informe anual de 2016, el Consejo de Europa no mencionó los abusos de los derechos humanos en Crimea porque Rusia no había permitido la entrada de sus observadores. [318]

En febrero de 2016, el defensor de los derechos humanos Emir-Usein Kuku , de Crimea, fue detenido y acusado de pertenecer a la organización islamista Hizb ut-Tahrir , aunque niega cualquier implicación en dicha organización. Amnistía Internacional ha pedido su liberación inmediata. [319] [320]

El 24 de mayo de 2014, Ervin Ibragimov, ex miembro del Consejo Municipal de Bakhchysarai y miembro del Congreso Mundial de Tártaros de Crimea, desapareció. Las imágenes de una cámara de vigilancia de una tienda cercana documentan que Ibragimov fue detenido por un grupo de hombres y que habló brevemente con ellos antes de ser obligado a subir a su camioneta. [321] Según el Grupo de Protección de los Derechos Humanos de Járkov, las autoridades rusas se niegan a investigar la desaparición de Ibragimov. [322]

En mayo de 2018, las autoridades rusas encarcelaron a Server Mustafayev , fundador y coordinador del movimiento de derechos humanos Solidaridad con Crimea, y lo acusaron de “pertenencia a una organización terrorista”. Amnistía Internacional y Front Line Defenders exigen su liberación inmediata. [323] [324]

El 12 de junio de 2018, Ucrania presentó un memorando de unos 90 kg, que consta de 17.500 páginas de texto en 29 volúmenes, ante la Corte Internacional de Justicia de las Naciones Unidas sobre la discriminación racial por parte de las autoridades rusas en la Crimea ocupada y la financiación estatal del terrorismo por parte de la Federación de Rusia en el Donbás . [325] [326]

Entre 2015 y 2019, más de 134.000 personas que vivían en Crimea solicitaron y obtuvieron pasaportes ucranianos. [327]

Antes de la ocupación rusa, el apoyo a la anexión a Rusia era del 23% en una encuesta de 2013, por debajo del 33% en 2011. [328] Una encuesta conjunta de la agencia gubernamental estadounidense Broadcasting Board of Governors y la firma de encuestas Gallup se llevó a cabo durante abril de 2014. [329] Se encuestó a 500 residentes de Crimea. La encuesta encontró que el 82,8% de los encuestados creía que los resultados del referéndum sobre el estatus de Crimea reflejaban las opiniones de la mayoría de los residentes de Crimea, mientras que el 6,7% dijo que no. El 73,9% de los encuestados dijo que pensaba que la anexión tendría un impacto positivo en sus vidas, mientras que el 5,5% dijo que no lo tendría. El 13,6% dijo que no sabía. [329]

Una encuesta exhaustiva publicada el 8 de mayo de 2014 por el Pew Research Centre sondeó las opiniones locales sobre la anexión. [330] A pesar de las críticas internacionales al referéndum del 16 de marzo sobre el estatus de Crimea , el 91% de los crimeos encuestados pensó que la votación fue libre y justa, y el 88% dijo que el gobierno ucraniano debería reconocer los resultados. [330]

En una encuesta realizada en 2019 por la empresa rusa FOM, el 72% de los residentes de Crimea encuestados afirmó que sus vidas habían mejorado desde la anexión. Al mismo tiempo, solo el 39% de los rusos que viven en el continente afirmó que la anexión fue beneficiosa para el país en su conjunto, lo que marca una caída significativa respecto del 67% en 2015. [331]

Aunque el gobierno ruso citó activamente las encuestas de opinión locales para argumentar que la anexión era legítima (es decir, apoyada por la población del territorio en cuestión), [332] [333] algunos autores han advertido contra el uso de encuestas sobre identidades y apoyo a la anexión realizadas en el "ambiente político opresivo" de Crimea en manos de Rusia. [334] [335]

Inmediatamente después de la firma del tratado de adhesión en marzo, el Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores de Ucrania convocó al Director Provisional de Rusia en Ucrania para presentar una nota verbal de protesta contra el reconocimiento por parte de Rusia de la República de Crimea y su posterior anexión. [336] Dos días después, la Verjovna Rada condenó el tratado [337] y calificó las acciones de Rusia de "grave violación del derecho internacional ". La Rada hizo un llamamiento a la comunidad internacional para que evitara el reconocimiento de la "llamada República de Crimea" o la anexión de Crimea y Sebastopol por parte de Rusia como nuevos sujetos federales.

El 15 de abril de 2014, la Verjovna Rada declaró que la República Autónoma de Crimea y Sebastopol estaban bajo " ocupación provisional " por parte del ejército ruso [338] e impuso restricciones de viaje a los ucranianos que visitaran Crimea. [339] Los territorios también fueron considerados "partes inalienables de Ucrania" sujetas a la ley ucraniana. Entre otras cosas, la ley especial aprobada por la Rada restringió los movimientos de ciudadanos extranjeros hacia y desde la península de Crimea y prohibió ciertos tipos de emprendimientos. [340] La ley también prohibió la actividad de los órganos gubernamentales formados en violación de la ley ucraniana y calificó sus actos como nulos y sin valor . [341] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ]

Las autoridades ucranianas redujeron considerablemente el volumen de agua que fluye hacia Crimea a través del Canal del Norte de Crimea debido a la enorme deuda por el agua suministrada el año anterior, lo que amenaza la viabilidad de los cultivos agrícolas de la península, que dependen en gran medida del riego. [343] [344]

El 11 de marzo de 2014, el Consejo Nacional de Radiodifusión y Televisión de Ucrania ordenó a todos los operadores de cable que dejaran de transmitir varios canales rusos, incluidas las versiones internacionales de las principales estaciones controladas por el Estado, Rusia-1 , Canal Uno y NTV, así como el canal de noticias Rusia-24 . [345]

En marzo de 2014, los activistas comenzaron a organizar flash mobs en supermercados para instar a los clientes a no comprar productos rusos y a boicotear las gasolineras , los bancos y los conciertos rusos. En abril de 2014, algunos cines de Kiev, Lviv y Odesa comenzaron a prohibir películas rusas . [346]

El 2 de diciembre de 2014, Ucrania creó un Ministerio de Política de Información , uno de cuyos objetivos era, según el primer ministro de Información, Yuriy Stets , contrarrestar la "agresión informativa rusa". [347]

En diciembre de 2014, Ucrania suspendió todos los servicios de trenes y autobuses a Crimea. [348]

El 16 de septiembre de 2015, el Parlamento ucraniano votó a favor de la ley que fija el 20 de febrero de 2014 como fecha oficial de la ocupación temporal rusa de la península de Crimea. [349] [350] El 7 de octubre de 2015, el presidente de Ucrania firmó la ley para que entrara en vigor. [351]

El Ministerio de Territorios Temporalmente Ocupados y Desplazados Internos fue establecido por el gobierno ucraniano el 20 de abril de 2016 para gestionar las partes ocupadas de las regiones de Donetsk, Luhansk y Crimea afectadas por la intervención militar rusa de 2014. [352] En 2015, el número de desplazados internos registrados en Ucrania que habían huido de Crimea ocupada por Rusia era de 50.000. [353]

.jpg/440px-Марш_за_мир_и_свободу_(2).jpg)

En una encuesta publicada el 24 de febrero de 2014 por el Centro de Investigación de Opinión Pública de Rusia , de propiedad estatal , sólo el 15% de los rusos encuestados respondió "sí" a la pregunta: "¿Debe Rusia reaccionar al derrocamiento de las autoridades legalmente elegidas en Ucrania?" [354]

El Comité de la Duma Estatal para Asuntos de la Comunidad de Estados Independientes , encabezado por Leonid Slutsky , visitó Simferópol el 25 de febrero de 2014 y dijo: "Si el parlamento de la autonomía de Crimea o sus residentes expresan el deseo de unirse a la Federación Rusa, Rusia estará preparada para considerar este tipo de solicitud. Examinaremos la situación y lo haremos rápidamente". [355] También declararon que en caso de un referéndum para que la región de Crimea se uniera a la Federación Rusa, considerarían sus resultados "muy rápidamente". [356] Más tarde, Slutsky anunció que la prensa de Crimea lo había entendido mal y que aún no se había tomado ninguna decisión sobre la simplificación del proceso de adquisición de la ciudadanía rusa para las personas en Crimea. [357] También agregó que si "los ciudadanos rusos están en peligro, comprendan que no nos mantendremos al margen". [358] El 25 de febrero, en una reunión con políticos de Crimea, declaró que Viktor Yanukovych seguía siendo el presidente legítimo de Ucrania. [359] Ese mismo día, la Duma rusa anunció que estaba determinando medidas para que los rusos en Ucrania que "no querían separarse del mundo ruso" pudieran adquirir la ciudadanía rusa. [360]

El 26 de febrero, el presidente ruso, Vladimir Putin, ordenó que las Fuerzas Armadas rusas se pusieran en "alerta en el Distrito Militar Occidental, así como en las unidades estacionadas en el Comando del Distrito Militar Central del 2º Ejército involucradas en la defensa aeroespacial, tropas aerotransportadas y transporte militar de largo alcance". A pesar de las especulaciones de los medios de comunicación de que esto era una reacción a los acontecimientos en Ucrania, el Ministro de Defensa ruso , Sergei Shoigu, dijo que era por razones independientes de los disturbios en Ucrania. [361] El 27 de febrero de 2014, el gobierno ruso desestimó las acusaciones de que estaba violando los acuerdos básicos sobre la Flota del Mar Negro : "Todos los movimientos de vehículos blindados se llevan a cabo en pleno cumplimiento de los acuerdos básicos y no requieren ninguna aprobación". [362]

El 27 de febrero, los órganos gubernamentales rusos presentaron el nuevo proyecto de ley sobre la concesión de la ciudadanía. [363]

El Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores de Rusia hizo un llamamiento a Occidente y, en particular, a la OTAN para que "abandonen las declaraciones provocadoras y respeten el estatuto neutral de Ucrania". [364] En su declaración, el ministerio afirma que el acuerdo sobre la solución de la crisis , que se firmó el 21 de febrero y que fue presenciado por los ministerios de Asuntos Exteriores de Alemania, Polonia y Francia, hasta la fecha no se ha aplicado [364] ( Vladimir Lukin de Rusia no lo ha firmado [365] ).

El 28 de febrero, según ITAR-TASS , el Ministerio de Transporte ruso interrumpió las conversaciones con Ucrania en relación con el proyecto del Puente de Crimea . [366] Sin embargo, el 3 de marzo , Dmitry Medvedev , entonces Primer Ministro de Rusia , firmó un decreto creando una subsidiaria de Carreteras Rusas ( Avtodor ) para construir un puente en una ubicación no especificada a lo largo del Estrecho de Kerch. [367] [368] [369]

En las redes sociales rusas, hubo un movimiento para reunir a voluntarios que sirvieron en el ejército ruso para ir a Ucrania. [370]

El 28 de febrero, el Presidente Putin declaró en conversaciones telefónicas con dirigentes clave de la UE que era de "extrema importancia no permitir una mayor escalada de violencia y la necesidad de una rápida normalización de la situación en Ucrania". [371] Ya el 19 de febrero el Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores ruso se había referido a la revolución de Euromaidán como la " revolución marrón ". [372] [373]

El 2 de marzo, en Moscú, unas 27.000 personas se manifestaron en apoyo de la decisión del gobierno ruso de intervenir en Ucrania. [374] Las manifestaciones recibieron considerable atención en la televisión estatal rusa y fueron aprobadas oficialmente por el gobierno. [374]

Mientras tanto, el 1 de marzo, cinco personas que estaban haciendo piquetes junto al edificio del Consejo de la Federación contra la invasión de Ucrania fueron detenidas. [375] Al día siguiente, unas 200 personas protestaron en el edificio del Ministerio de Defensa ruso en Moscú contra la intervención militar rusa. [376] Unas 500 personas también se reunieron para protestar en la plaza Manezhnaya de Moscú, y el mismo número de personas en la plaza de San Isaac de San Petersburgo. [377] El 2 de marzo, unos once manifestantes se manifestaron en Ekaterimburgo contra la intervención rusa, algunos envueltos en la bandera ucraniana. [378] También se celebraron protestas en Cheliábinsk el mismo día. [379] El músico de rock Andrey Makarevich también se opuso a la intervención militar y escribió: "¿Queréis una guerra con Ucrania? No será como la de Abjasia : la gente de Maidán se ha endurecido y sabe por qué lucha: por su país, por su independencia... Tenemos que vivir con ellos. Seguir siendo vecinos y, preferiblemente, en amistad. Pero ellos son los que deciden cómo quieren vivir". [380] El profesor del Departamento de Filosofía del Instituto Estatal de Relaciones Internacionales de Moscú, Andrey Zubov, fue despedido por su artículo en Vedomosti , en el que criticaba la intervención militar rusa. [381]

El 2 de marzo, un residente de Moscú protestó contra la intervención rusa sosteniendo una pancarta que decía "Alto a la guerra", pero fue inmediatamente acosado por los transeúntes. La policía procedió entonces a arrestarlo. Una mujer se presentó con una acusación inventada contra él, de golpear a un niño; sin embargo, su afirmación, debido a la falta de una víctima y obviamente falsa, fue ignorada por la policía. [382] Andrei Zubov, profesor del Instituto Estatal de Relaciones Internacionales de Moscú, que comparó las acciones rusas en Crimea con la anexión de Austria por la Alemania nazi en 1938 , fue amenazado. Alexander Chuyev, el líder del partido pro-Kremlin Spravedlivaya Rossiya, también se opuso a la intervención rusa en Ucrania. Boris Akunin , un popular escritor ruso, predijo que las acciones de Rusia conducirían al aislamiento político y económico. [382]

President Putin's approval rating among the Russian public increased by nearly 10% since the crisis began, up to 71.6%, the highest in three years, according to a poll conducted by the All-Russian Center for Public Opinion Research, released on 19 March.[384][385] Additionally, the same poll showed that more than 90% of Russians supported unification with the Crimean Republic.[384] According to a 2021 study in the American Political Science Review, "three quarters of those who rallied to Putin after Russia annexed Crimea were engaging in at least some form of dissembling and that this rallying developed as a rapid cascade, with social media joining television in fueling perceptions this was socially desirable".[386]

On 4 March, at a press conference in Novo-Ogaryovo, President Putin expressed his view on the situation that if a revolution took place in Ukraine, it would be a new country with which Russia had not concluded any treaties.[387] He offered an analogy with the events of 1917 in Russia, when as a result of the revolution the Russian Empire fell apart and a new state was created.[387] However, he stated Ukraine would still have to honour its debts.

.jpg/440px-Celebrating_Victory_Day_and_the_70th_anniversary_of_Sevastopol’s_liberation_(2493-24).jpg)

Russian politicians speculated that there were already 143,000 Ukrainian refugees in Russia.[388] The Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs refuted those claims of refugee increases in Russia.[389] At a briefing on 4 March 2014, the director of the department of information policy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine Yevhen Perebiynis said that Russia was misinforming its own citizens as well as the entire international community to justify its own actions in the Crimea.[390]

On 5 March, an anchor of the Russian-controlled TV channel RT America, Abby Martin, criticized her employer's biased coverage of the military invervention.[391][392] Also on 5 March 2014, another RT America anchor, Liz Wahl, of the network's Washington, DC bureau, resigned on air, explaining that she could not be "part of a network that whitewashes the actions of Putin" and citing her Hungarian ancestry and the memory of the Soviet repression of the Hungarian Uprising as a factor in her decision.[393]

In early March, Igor Andreyev, a 75-year-old survivor of the Siege of Leningrad, attended an anti-war rally against the Russian intervention in Crimea and was holding a sign that read "Peace to the World". The riot police arrested him, and a local pro-government lawyer then accused him of being a supporter of "fascism". The retiree, who lived on a 6,500-ruble monthly pension, was fined 10,000 rubles.[394]

Prominent dissident Mikhail Khodorkovsky said that Crimea should stay within Ukraine with broader autonomy.[395]

Tatarstan, a republic within Russia populated by Volga Tatars, has sought to alleviate concerns about the treatment of Tatars by Russia, as Tatarstan is an oil-rich and economically successful republic in Russia.[396] On 5 March, President of Tatarstan Rustam Minnikhanov signed an agreement on co-operation between Tatarstan and the Aksyonov government in Crimea that implied collaboration between ten government institutions as well as significant financial aid to Crimea from Tatarstan businesses.[396] On 11 March, Minnikhanov was in Crimea on his second visit and attended as a guest in the Crimean parliament chamber during the vote on the declaration of sovereignty pending 16 March referendum.[396] The Tatarstan's Mufti Kamil Samigullin invited Crimean Tatars to study in madrasas in Kazan, and declared support for their "brothers in faith and blood".[396] Mustafa Dzhemilev, a former leader of the Crimean Tatar Majlis, believed that forces that were suspected to be Russian forces should leave the Crimean Peninsula,[396] and asked the UN Security Council to send peacekeepers into the region.[397]

On 15 March, thousands of protesters (estimates varying from 3,000 by official sources up to 50,000 claimed by the opposition) in Moscow marched against Russian involvement in Ukraine, many waving Ukrainian flags.[398] At the same time, a pro-government (and pro-referendum) rally occurred across the street, counting in the thousands as well (officials claiming 27,000 with the opposition claiming about 10,000).

In February 2015, the leading independent Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta obtained documents,[399] allegedly written by oligarch Konstantin Malofeev and others, which provided the Russian government with a strategy in the event of Viktor Yanukovych's removal from power and the break-up of Ukraine, which were considered likely. The documents outline plans for annexation of Crimea and the eastern portions of the country, closely describing the events that actually followed after Yanukovych's fall. The documents also describe plans for a public relations campaign that would seek to justify Russian actions.[400][401][402]

In June 2015 Mikhail Kasyanov stated that all Russian Duma decisions on Crimea annexation were illegal from the international point of view and the annexation was provoked by false accusations of discrimination of Russian nationals in Ukraine.[403]

As of January 2019, Arkady Rotenberg through his Stroygazmontazh LLC and his companies building the Crimean Bridge along with Nikolai Shamalov and Yuri Kovalchuk through their Rossiya Bank have become the most important investors in Russia's development of the annexed Crimea.[404]