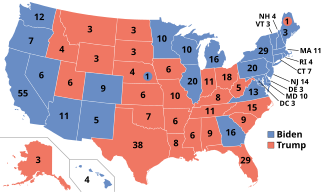

El mandato de Donald Trump como el 45.º presidente de los Estados Unidos comenzó con su toma de posesión el 20 de enero de 2017 y terminó el 20 de enero de 2021. Trump, un republicano de la ciudad de Nueva York , asumió el cargo tras su victoria en el Colegio Electoral sobre la candidata demócrata Hillary Clinton en las elecciones presidenciales de 2016 , en las que perdió el voto popular ante Clinton por casi tres millones de votos. Tras su toma de posesión, se convirtió en el primer presidente en la historia de Estados Unidos sin cargos públicos previos ni antecedentes militares . Trump hizo una cantidad sin precedentes de declaraciones falsas o engañosas durante su campaña y presidencia. Su presidencia terminó tras su derrota en las elecciones presidenciales de 2020 ante el exvicepresidente demócrata Joe Biden , después de un mandato en el cargo.

Trump no tuvo éxito en sus esfuerzos por derogar la Ley de Atención Médica Asequible , pero rescindió el mandato individual . Buscó recortes sustanciales del gasto en los principales programas de bienestar, incluidos Medicare y Medicaid . Trump firmó la Ley de Reducción de Impuestos y Empleos de 2017 y una derogación parcial de la Ley Dodd-Frank . Designó a Neil Gorsuch , Brett Kavanaugh y Amy Coney Barrett para la Corte Suprema . Trump revocó numerosas regulaciones ambientales , se retiró del Acuerdo de París sobre el cambio climático y firmó la Ley Great American Outdoors , pero luego emitió una Orden Ejecutiva que socavó su impacto. Firmó la Ley del Primer Paso . Promulgó aranceles , lo que desencadenó aranceles de represalia de China , Canadá, México y la Unión Europea. Se retiró de las negociaciones de la Asociación Transpacífica y firmó el Acuerdo Estados Unidos-México-Canadá , un sucesor del Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte con cambios modestos. El déficit federal aumentó significativamente bajo el gobierno de Trump debido al aumento del gasto y los recortes de impuestos.

Trump implementó una controvertida política de separación familiar para los migrantes detenidos en la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México, a partir de 2018. Su demanda de financiación federal para un muro fronterizo resultó en el cierre gubernamental más largo de la historia de Estados Unidos . Desplegó fuerzas policiales federales en respuesta a los disturbios raciales en 2020. La política exterior de " Estados Unidos primero " de Trump se caracterizó por acciones unilaterales, sin tener en cuenta las normas tradicionales y los aliados. Su administración implementó una importante venta de armas a Arabia Saudita ; negó la entrada a Estados Unidos a ciudadanos de varios países de mayoría musulmana ; reconoció a Jerusalén como la capital de Israel ; y negoció los Acuerdos de Abraham , una serie de acuerdos de normalización entre Israel y varios estados árabes . Trump retiró las tropas estadounidenses del norte de Siria, lo que permitió a Turquía ocupar el área . Su administración hizo un trato condicional con los talibanes para retirar las tropas estadounidenses de Afganistán en 2021. Trump se reunió con el líder de Corea del Norte, Kim Jong Un , tres veces. Retiró a Estados Unidos del acuerdo nuclear con Irán y posteriormente intensificó las tensiones en el Golfo Pérsico al ordenar el asesinato del general Qasem Soleimani .

La investigación del fiscal especial Robert Mueller (2017-2019) concluyó que Rusia interfirió para favorecer la candidatura de Trump y que si bien la evidencia prevaleciente "no estableció que los miembros de la campaña de Trump conspiraran o coordinaran con el gobierno ruso", se produjeron posibles obstrucciones a la justicia durante el curso de esa investigación. Trump intentó presionar a Ucrania para que anunciara investigaciones sobre su rival político Joe Biden, lo que desencadenó su primer impeachment por parte de la Cámara de Representantes el 18 de diciembre de 2019, pero fue absuelto por el Senado el 5 de febrero de 2020. Trump reaccionó lentamente a la pandemia de COVID-19 , ignoró o contradijo muchas recomendaciones de los funcionarios de salud en sus mensajes y promovió información errónea sobre tratamientos no probados y la disponibilidad de pruebas.

Tras su derrota en las elecciones presidenciales de 2020 ante Biden, Trump se negó a reconocer su derrota e inició una extensa campaña para anular los resultados , denunciando un fraude electoral generalizado . El 6 de enero de 2021, durante un mitin en la Elipse , Trump instó a sus partidarios a marchar hacia el Capitolio , donde el Congreso estaba contando los votos electorales para formalizar la victoria de Biden. Una turba de partidarios de Trump irrumpió en el Capitolio , suspendiendo el recuento y provocando la evacuación del vicepresidente Mike Pence y otros miembros del Congreso. El 13 de enero, la Cámara de Representantes votó a favor de acusar a Trump por segunda vez sin precedentes por incitación a la insurrección , pero luego fue absuelto nuevamente por el Senado el 13 de febrero, después de que ya había dejado el cargo.

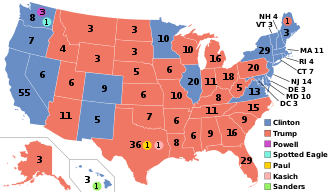

El 16 de junio de 2015, Donald Trump anunció oficialmente su candidatura a la nominación republicana en las elecciones presidenciales de 2016. En mayo de 2016, Trump consiguió la nominación al ganar la mayoría de los delegados. Trump eligió al gobernador de Indiana, Mike Pence , como su compañero de fórmula y ambos fueron nominados oficialmente como candidatos republicanos en la Convención Nacional Republicana de 2016 .

Con el mandato del presidente demócrata Barack Obama limitado, los demócratas nominaron a la exsecretaria de Estado Hillary Clinton de Nueva York para presidenta y al senador Tim Kaine de Virginia para vicepresidente. El 9 de noviembre de 2016, Trump ganó las elecciones presidenciales con 304 votos electorales en comparación con los 227 de Clinton, aunque Clinton ganó una pluralidad del voto popular a nivel nacional, recibiendo casi 2,9 millones de votos más que Trump. Trump se convirtió así en la quinta persona en ganar la presidencia mientras perdía el voto popular . [1] En las elecciones concurrentes al Congreso , los republicanos mantuvieron sus mayorías tanto en la Cámara de Representantes como en el Senado , y el presidente de la Cámara de Representantes Paul Ryan y el líder de la mayoría del Senado Mitch McConnell permanecieron en sus puestos.

.jpg/440px-President_Barack_Obama_meets_with_Donald_Trump_in_the_Oval_Office_(cropped).jpg)

El período de transición presidencial comenzó después de la victoria de Trump en las elecciones presidenciales estadounidenses de 2016 , aunque Trump había elegido a Bill Hagerty para comenzar a planificar la transición en agosto de 2016. Durante el período de transición, Trump anunció nominaciones para su gabinete y administración .

Trump asumió el cargo el 20 de enero de 2017, sucediendo a Barack Obama . Fue juramentado por el presidente de la Corte Suprema, John Roberts . [2] En su discurso inaugural de diecisiete minutos, Trump pintó un panorama sombrío de los Estados Unidos contemporáneos, prometiendo poner fin a la "masacre estadounidense" causada por el crimen urbano y diciendo que la "riqueza, la fuerza y la confianza de los Estados Unidos se han disipado" por los empleos perdidos en el extranjero. [3] Declaró que su estrategia sería " Estados Unidos primero ". [2] La protesta de un solo día más grande en la historia de los Estados Unidos, la Marcha de las Mujeres , tuvo lugar el día después de su toma de posesión y fue impulsada por la oposición a Trump y sus políticas y puntos de vista. [4]

La administración Trump se caracterizó por una rotación récord, en particular entre el personal de la Casa Blanca. A principios de 2018, el 43% de los puestos de alto nivel de la Casa Blanca habían sido renovados. [5] La administración tuvo una tasa de rotación más alta en los primeros dos años y medio que la de los cinco presidentes anteriores durante todo su mandato. [6]

En octubre de 2019, uno de cada 14 designados políticos de Trump eran ex lobistas; en menos de tres años de su presidencia, Trump había designado a más de cuatro veces más lobistas que su predecesor Barack Obama en el transcurso de sus primeros seis años en el cargo. [7]

El gabinete de Trump incluyó al senador estadounidense de Alabama Jeff Sessions como fiscal general , [8] al banquero Steve Mnuchin como secretario del Tesoro , [9] al general retirado del Cuerpo de Marines James Mattis como secretario de Defensa , [10] y al director ejecutivo de ExxonMobil, Rex Tillerson, como secretario de Estado . [11] Trump también incorporó a políticos que se le habían opuesto durante la campaña presidencial, como el neurocirujano Ben Carson como secretario de Vivienda y Desarrollo Urbano , [12] y la gobernadora de Carolina del Sur, Nikki Haley, como embajadora ante las Naciones Unidas . [13]

Días después de las elecciones presidenciales, Trump eligió al presidente del RNC, Reince Priebus, como su jefe de gabinete . [14] Trump eligió a Sessions para el puesto de fiscal general. [15]

En febrero de 2017, Trump anunció formalmente la estructura de su gabinete, elevando al Director de Inteligencia Nacional y al Director de la Agencia Central de Inteligencia al nivel de gabinete. El Presidente del Consejo de Asesores Económicos , que Obama había agregado al gabinete en 2009, fue removido del gabinete. El gabinete de Trump estaba compuesto por 24 miembros, más que Obama (23) o George W. Bush (21). [16]

El 13 de febrero de 2017, Trump despidió a Michael Flynn del puesto de asesor de seguridad nacional con el argumento de que había mentido al vicepresidente Pence sobre sus comunicaciones con el embajador ruso Sergey Kislyak ; Flynn luego se declaró culpable de mentirle al Buró Federal de Investigaciones (FBI) sobre sus contactos con Rusia. [17] Flynn fue despedido en medio de la controversia en curso sobre la interferencia rusa en las elecciones de 2016 y las acusaciones de que el equipo electoral de Trump coludió con agentes rusos.

En julio de 2017, John F. Kelly , quien se había desempeñado como secretario de Seguridad Nacional , reemplazó a Priebus como jefe de gabinete. [18] En septiembre de 2017, Tom Price renunció como secretario de HHS en medio de críticas por su uso de aviones chárter privados para viajes personales. [19] Kirstjen Nielsen sucedió a Kelly como secretaria en diciembre de 2017. [20] El secretario de Estado Rex Tillerson fue despedido a través de un tuit en marzo de 2018; Trump nombró a Mike Pompeo para reemplazar a Tillerson y a Gina Haspel para suceder a Pompeo como directora de la CIA. [21] A raíz de una serie de escándalos, Scott Pruitt renunció como administrador de la Agencia de Protección Ambiental (EPA) en julio de 2018. [22] El secretario de Defensa, Jim Mattis , informó a Trump de su renuncia luego del abrupto anuncio de Trump el 19 de diciembre de 2018 de que las 2000 tropas estadounidenses restantes en Siria serían retiradas, en contra de las recomendaciones de sus asesores militares y civiles. [23]

Trump despidió a numerosos inspectores generales de agencias, incluidos aquellos que investigaban a la administración Trump y a colaboradores cercanos de Trump. En 2020, despidió a cinco inspectores generales en dos meses. El Washington Post escribió: "Por primera vez desde que se creó el sistema tras el escándalo de Watergate, los inspectores generales se encuentran bajo ataque sistemático por parte del presidente, poniendo en riesgo la supervisión independiente del gasto y las operaciones federales". [24]

El 9 de mayo de 2017, Trump despidió al director del FBI, James Comey , diciendo que había aceptado las recomendaciones del fiscal general Sessions y del fiscal general adjunto Rod Rosenstein de despedir a Comey. La recomendación de Sessions se basó en la de Rosenstein, mientras que Rosenstein escribió que Comey debería ser despedido por su manejo de la conclusión de la investigación del FBI sobre la controversia del correo electrónico de Hillary Clinton . [25] El 10 de mayo, Trump se reunió con el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores ruso , Serguéi Lavrov, y el embajador ruso , Serguéi Kislyak . Basándose en las notas de la Casa Blanca de la reunión , Trump les dijo a los rusos: "Acabo de despedir al jefe del FBI. Estaba loco, un verdadero loco ... Enfrenté una gran presión debido a Rusia. Eso se ha ido". [26] El 11 de mayo, Trump dijo en una entrevista en video: "... independientemente de la recomendación, iba a despedir a Comey ... de hecho, cuando decidí hacerlo, me dije a mí mismo, dije, ya saben, esta cosa de Rusia con Trump y Rusia es una historia inventada". [27] El 18 de mayo, Rosenstein dijo a los miembros del Senado de los EE. UU. que recomendó el despido de Comey sabiendo que Trump ya había decidido despedirlo. [28] Después del despido de Comey, los eventos se compararon con los de la " Masacre del sábado por la noche " durante la administración de Richard Nixon y hubo un debate sobre si Trump había provocado una crisis constitucional , ya que había despedido al hombre que lideraba una investigación sobre los asociados de Trump. [29] Las declaraciones de Trump plantearon preocupaciones de posible obstrucción de la justicia. [30] En el memorando de Comey sobre una reunión de febrero de 2017 con Trump , Comey dijo que Trump intentó persuadirlo de abortar la investigación sobre Flynn. [31]

.jpg/440px-President_Trump_Nominates_Judge_Amy_Coney_Barrett_for_Associate_Justice_of_the_U.S._Supreme_Court_(50397909157).jpg)

Después de que los republicanos ganaran el control del Senado de los EE. UU. en 2014, solo el 28,6 por ciento de los nominados judiciales fueron confirmados, "el porcentaje más bajo de confirmaciones de 1977 a 2018". [32] Al final de la presidencia de Obama, 105 puestos de jueces estaban vacantes. [33] Los republicanos del Senado, liderados por el líder de la mayoría del Senado Mitch McConnell , priorizaron la confirmación de los designados judiciales de Trump, y lo hicieron rápidamente. [34] Para noviembre de 2018, Trump había nombrado a 29 jueces para los tribunales de apelaciones de EE. UU ., más que cualquier presidente moderno en los primeros dos años de un mandato presidencial. [35]

Trump finalmente nombró a 226 jueces federales del Artículo III y 260 jueces federales en total. [36] Sus designados, que generalmente estaban afiliados a la conservadora Sociedad Federalista , desplazaron el poder judicial hacia la derecha . [37] Un tercio de los designados por Trump tenían menos de 45 años cuando fueron nombrados, una edad mucho mayor que bajo presidentes anteriores. [37] Los nominados judiciales de Trump tenían menos probabilidades de ser mujeres o de minorías étnicas que los de la administración anterior. [38] [39] De los nombramientos judiciales de Trump para los tribunales de apelaciones de Estados Unidos (tribunales de circuito), dos tercios fueron hombres blancos, en comparación con el 31% de los nominados de Obama y el 63% de los nominados de George W. Bush. [37] [40]

Trump hizo tres nominaciones a la Corte Suprema : Neil Gorsuch , Brett Kavanaugh y Amy Coney Barrett :

Los propios empleados, subordinados y aliados de Trump frecuentemente caracterizaron a Trump como infantil. [47] Trump supuestamente evitó leer documentos informativos detallados, incluido el Informe diario del presidente , a favor de recibir informes orales. [48] [49] Los informadores de inteligencia supuestamente repitieron el nombre y el título del presidente para mantener su atención. [50] [51] También se sabía que adquiría información viendo hasta ocho horas de televisión cada día, sobre todo programas de Fox News como Fox & Friends y Hannity , cuyos puntos de conversación de transmisión Trump a veces repetía en declaraciones públicas, particularmente en tuits de madrugada. [52] [53] [54] Trump supuestamente expresó enojo si los análisis de inteligencia contradecían sus creencias o declaraciones públicas, y dos informadores afirmaron que habían recibido instrucciones de sus superiores de no proporcionar a Trump información que contradijera sus declaraciones públicas. [51]

Según se informa, Trump había fomentado el caos como técnica de gestión, lo que resultó en una baja moral y confusión política entre su personal. [55] [56] Trump demostró ser incapaz de comprometerse de manera efectiva durante el 115.º Congreso de los EE. UU ., lo que llevó a un estancamiento gubernamental significativo y pocos logros legislativos notables a pesar del control republicano de ambas cámaras del Congreso. [57] La historiadora presidencial Doris Kearns Goodwin encontró que Trump carecía de varios rasgos de un líder eficaz, entre ellos "humildad, reconocer errores, asumir la culpa y aprender de los errores, empatía, resiliencia, colaboración, conectar con la gente y controlar las emociones improductivas". [58]

En enero de 2018, Axios informó que el horario laboral de Trump era típicamente de 11:00 a. m. a 6:00 p. m. (un inicio más tardío y un final más temprano en comparación con el comienzo de su presidencia) y que estaba celebrando menos reuniones durante su horario laboral para adaptarse al deseo de Trump de tener más tiempo libre no estructurado (etiquetado como "tiempo ejecutivo"). [59] En 2019, Axios publicó el horario de Trump desde el 7 de noviembre de 2018 hasta el 1 de febrero de 2019, y calculó que alrededor del sesenta por ciento del tiempo entre las 8:00 a. m. y las 5:00 p. m. era "tiempo ejecutivo". [60]

La cantidad y la escala de las declaraciones de Trump en discursos públicos, comentarios y tuits identificados como falsos por académicos, verificadores de hechos y comentaristas se caracterizaron como sin precedentes para un presidente estadounidense, [64] [65] e incluso sin precedentes en la política estadounidense. [66] The New Yorker calificó las falsedades como una parte distintiva de su identidad política, [67] y también han sido descritas por la asesora política republicana Amanda Carpenter como una táctica de manipulación psicológica . [68] Su Casa Blanca había rechazado la idea de la verdad objetiva , [69] y su campaña y presidencia han sido descritas como " posverdad ", [70] así como hiperorwellianas . [ 71] La firma retórica de Trump incluía ignorar datos de instituciones federales que eran incompatibles con sus argumentos; citar rumores, evidencia anecdótica y afirmaciones cuestionables en medios partidistas; negar la realidad (incluidas sus propias declaraciones); y distraer cuando se exponían falsedades. [72]

Durante el primer año de la presidencia de Trump, el equipo de verificación de hechos del Washington Post escribió que Trump era "el político más cuestionado en cuanto a hechos" con el que se había "encontrado jamás ... el ritmo y el volumen de las declaraciones erróneas del presidente significa que no podemos seguirle el ritmo". [73] El Post descubrió que, como presidente, Trump hizo más de 30.000 afirmaciones falsas o engañosas, aumentando de un promedio de seis al día en su primer año como presidente a 39 afirmaciones al día en su último año. [74] Las afirmaciones falsas o engañosas más comunes de Trump se referían a la economía y el empleo, su propuesta de muro fronterizo y su legislación fiscal; [75] también había hecho declaraciones falsas sobre administraciones anteriores, [75] así como otros temas, incluidos el crimen, el terrorismo, la inmigración, Rusia y la investigación de Mueller, la investigación de Ucrania , la inmigración y la pandemia de COVID-19 . [61] Los altos funcionarios de la administración también habían dado regularmente declaraciones falsas, engañosas o torturadas a los medios de comunicación, [76] [77] lo que dificultaba que los medios de comunicación tomaran en serio las declaraciones oficiales. [76]

Poco antes de que Trump consiguiera la nominación republicana de 2016, The New York Times informó que "expertos legales de todo el espectro político dicen" que la retórica de Trump reflejaba "una cosmovisión constitucional que muestra desprecio por la Primera Enmienda , la separación de poderes y el estado de derecho ", y agregó que "muchos académicos legales conservadores y libertarios advierten que elegir al Sr. Trump es una receta para una crisis constitucional ". [78] Los politólogos advirtieron que la retórica y las acciones del candidato Trump imitaban las de otros políticos que finalmente se volvieron autoritarios una vez en el cargo. [79] Algunos académicos han concluido que durante el mandato de Trump como presidente y en gran parte debido a sus acciones y retórica, Estados Unidos ha experimentado un retroceso democrático . [80] [81] Muchos republicanos prominentes han expresado preocupaciones similares de que el desprecio percibido de Trump por el estado de derecho traicionó los principios conservadores. [82] [83] [84] [85]

Durante los primeros dos años de su presidencia, Trump buscó repetidamente influenciar al Departamento de Justicia para que investigara a Clinton, [86] [87] al Comité Nacional Demócrata , [88] y Comey. [89] Repitió persistentemente una variedad de acusaciones, al menos algunas de las cuales ya habían sido investigadas o desacreditadas. [90] [91] En la primavera de 2018, Trump le dijo al abogado de la Casa Blanca, Don McGahn, que quería ordenar al Departamento de Justicia que procesara a Clinton y Comey, pero McGahn le advirtió a Trump que tal acción constituiría abuso de poder e invitaría a un posible juicio político . [92] En mayo de 2018, Trump exigió que el Departamento de Justicia investigara "si el FBI/DOJ se infiltró o vigiló la Campaña de Trump con fines políticos", que el Departamento de Justicia remitió a su inspector general . [93] Aunque no es ilegal que un presidente ejerza influencia sobre el Departamento de Justicia para abrir una investigación, los presidentes han evitado asiduamente hacerlo para evitar percepciones de interferencia política. [93] [94]

Sessions se resistió a varias demandas de Trump y sus aliados para que se investigaran a los oponentes políticos, lo que provocó que Trump expresara repetidamente su frustración, diciendo en un momento dado: "No tengo un fiscal general". [95] Mientras criticaba la investigación del fiscal especial en julio de 2019, Trump afirmó falsamente que la Constitución garantiza que "tengo el derecho de hacer lo que quiera como presidente". [96] Trump había sugerido o promovido en múltiples ocasiones opiniones sobre extender su presidencia más allá de los límites normales de mandato. [97] [98]

Trump criticó con frecuencia la independencia del poder judicial por interferir injustamente en la capacidad de su administración para decidir políticas. [99] En noviembre de 2018, en una reprimenda extraordinaria a un presidente en funciones, Roberts criticó la caracterización que hizo Trump de un juez que había dictaminado en contra de sus políticas como un "juez de Obama", y agregó: "Eso no es ley". [100] En octubre de 2020, veinte ex fiscales estadounidenses republicanos , entre ellos designados por cada presidente republicano desde Eisenhower, caracterizaron a Trump como "una amenaza para el estado de derecho en nuestro país". Greg Brower , que trabajó en la administración Trump, afirmó: "Está claro que el presidente Trump ve al Departamento de Justicia y al FBI como su propio bufete de abogados y agencia de investigación personal". [101]

.jpg/440px-President_Trump's_First_100_Days-_45_(33573172373).jpg)

.jpg/440px-President_Trump_in_Iowa_(48051727941).jpg)

Al principio de su presidencia, Trump desarrolló una relación muy polémica con los medios de comunicación, refiriéndose repetidamente a ellos como los " medios de noticias falsas " y "el enemigo del pueblo ". [102] Como candidato, Trump había rechazado credenciales de prensa por publicaciones ofensivas, pero dijo que no lo haría si era elegido. [103] Trump, tanto en privado como en público, reflexionó sobre la posibilidad de quitarles las credenciales de prensa de la Casa Blanca a los periodistas críticos . [104] Al mismo tiempo, la Casa Blanca de Trump dio pases de prensa temporales a medios de comunicación marginales de extrema derecha pro-Trump, como InfoWars y The Gateway Pundit , que son conocidos por publicar engaños y teorías conspirativas . [104] [105] [106]

En su primer día en el cargo, Trump acusó falsamente a los periodistas de subestimar el tamaño de la multitud en su toma de posesión y calificó a los medios de comunicación como "uno de los seres humanos más deshonestos de la Tierra". Las afirmaciones de Trump fueron defendidas notablemente por el secretario de prensa Sean Spicer , quien afirmó que la multitud de la toma de posesión había sido la más grande de la historia, una afirmación refutada por fotografías. [107] La asesora principal de Trump, Kellyanne Conway, defendió a Spicer cuando se le preguntó sobre la falsedad, diciendo que era un " hecho alternativo ", no una falsedad. [108]

La administración frecuentemente buscó castigar y bloquear el acceso a los reporteros que publicaban historias sobre la administración. [109] [110] [111] [112] Trump criticó frecuentemente al medio de comunicación de derecha Fox News por no apoyarlo lo suficiente, [113] amenazando con prestar su apoyo a alternativas a Fox News de la derecha. [114] El 16 de agosto de 2018, el Senado aprobó por unanimidad una resolución que afirmaba que "la prensa no es el enemigo del pueblo". [115]

Se ha estudiado la relación entre Trump, los medios de comunicación y las noticias falsas. Un estudio concluyó que entre el 7 de octubre y el 14 de noviembre de 2016, mientras que uno de cada cuatro estadounidenses visitó un sitio web de noticias falsas , "los partidarios de Trump visitaron la mayoría de los sitios web de noticias falsas, que eran abrumadoramente pro-Trump" y "casi 6 de cada 10 visitas a sitios web de noticias falsas provenían del 10% de las personas con las dietas de información en línea más conservadoras". [116] [117] Brendan Nyhan , uno de los autores del estudio, dijo en una entrevista: "La gente recibió mucha más información errónea de Donald Trump que de los sitios web de noticias falsas". [118]

.jpg/440px-19_03_2019_Declaração_à_imprensa_(47423243351).jpg)

En octubre de 2018, Trump elogió al representante estadounidense Greg Gianforte por agredir al periodista político Ben Jacobs en 2017. [120] Según los analistas, el incidente marcó la primera vez que el presidente "elogia abierta y directamente un acto violento contra un periodista en suelo estadounidense". [121] Más tarde ese mes, cuando CNN y demócratas prominentes fueron atacados con bombas por correo , Trump inicialmente condenó los intentos de bomba, pero poco después culpó a los "medios de comunicación dominantes a los que me refiero como noticias falsas" por causar "una parte muy grande de la ira que vemos hoy en nuestra sociedad". [122]

El Departamento de Justicia de Trump obtuvo mediante orden judicial los registros telefónicos o metadatos de correo electrónico de 2017 de periodistas de CNN, The New York Times , The Washington Post , BuzzFeed y Politico como parte de las investigaciones sobre filtraciones de información clasificada. [123]

Trump continuó usando Twitter después de la campaña presidencial. Continuó tuiteando personalmente desde @realDonaldTrump , su cuenta personal, mientras que su personal tuiteaba en su nombre usando la cuenta oficial @POTUS . Su uso de Twitter fue poco convencional para un presidente, con sus tuits iniciando controversias y convirtiéndose en noticias por derecho propio. [124] Algunos académicos se han referido a su tiempo en el cargo como la "primera presidencia verdadera de Twitter". [125] La administración Trump describió los tuits de Trump como "declaraciones oficiales del presidente de los Estados Unidos". [126] La jueza federal Naomi Reice Buchwald dictaminó en 2018 que el bloqueo de Trump a otros usuarios de Twitter debido a opiniones políticas opuestas violaba la Primera Enmienda y que debía desbloquearlos. [127] El fallo fue confirmado en apelación. [128] [129]

Sus tuits han sido reportados como imprudentes, impulsivos, vengativos y acosadores , a menudo hechos tarde en la noche o en las primeras horas de la mañana. [130] [131] [132] Sus tuits sobre una prohibición musulmana fueron utilizados con éxito contra su administración para detener dos versiones de restricciones de viaje de algunos países de mayoría musulmana. [133] Ha utilizado Twitter para amenazar e intimidar a sus oponentes políticos y posibles aliados políticos necesarios para aprobar proyectos de ley. [134] Muchos tuits parecen estar basados en historias que Trump ha visto en los medios, incluidos sitios web de noticias de extrema derecha como Breitbart y programas de televisión como Fox & Friends . [135] [136]

Trump usó Twitter para atacar a los jueces federales que fallaron en su contra en casos judiciales [137] y para criticar a funcionarios dentro de su propia administración, incluido el entonces Secretario de Estado Rex Tillerson , el entonces Asesor de Seguridad Nacional H. R. McMaster , el Fiscal General Adjunto Rod Rosenstein y, en varias ocasiones, el Fiscal General Jeff Sessions. [138] Tillerson fue finalmente despedido a través de un tuit de Trump. [139] Trump también tuiteó que su Departamento de Justicia es parte del "estado profundo" estadounidense ; [140] que "hubo tremendas filtraciones, mentiras y corrupción en los niveles más altos del FBI, los Departamentos de Justicia y Estado " ; [138] y que la investigación del fiscal especial es una " ¡CAZA DE BRUJAS !" [141] En agosto de 2018, Trump usó Twitter para escribir que el Fiscal General Jeff Sessions "debería detener" la investigación del fiscal especial de inmediato; también se refirió a ella como "amañada" y a sus investigadores como parciales. [142]

Luego de revisar minuciosamente los tweets recientes de la cuenta @realDonaldTrump y el contexto que los rodea, hemos suspendido permanentemente la cuenta debido al riesgo de una mayor incitación a la violencia.

8 de enero de 2021 [143]

En febrero de 2020, Trump tuiteó críticas a la sentencia propuesta por los fiscales para el ex asistente de Trump, Roger Stone . Unas horas más tarde, el Departamento de Justicia reemplazó la sentencia propuesta por los fiscales con una propuesta más leve. Esto dio la apariencia de interferencia presidencial en un caso penal y provocó una fuerte reacción negativa. Los cuatro fiscales originales se retiraron del caso; más de mil ex abogados del Departamento de Justicia firmaron una carta condenando la acción. [144] [145] El 10 de julio, Trump conmutó la sentencia de Stone días antes de que tuviera que presentarse en prisión. [146]

En respuesta a las protestas de mediados de 2020 por George Floyd , algunas de las cuales resultaron en saqueos, [147] Trump tuiteó el 25 de mayo que "cuando comienzan los saqueos, comienzan los disparos". No mucho después, Twitter restringió el tuit por violar la política de la empresa sobre la promoción de la violencia. [148] El 28 de mayo, Trump firmó una orden ejecutiva que buscaba limitar las protecciones legales de las empresas de redes sociales. [149]

El 8 de enero de 2021, Twitter anunció que había suspendido permanentemente la cuenta personal de Trump "debido al riesgo de una mayor incitación a la violencia" tras el ataque al Capitolio . [150] Trump anunció en su último tuit antes de la suspensión que no asistiría a la toma de posesión de Joe Biden . [151] Otras plataformas de redes sociales como Facebook , Snapchat , YouTube y otras también suspendieron los perfiles oficiales de Donald Trump. [152] [153]

.jpg/440px-Photo_of_the_Day_4_26_17_(33770181373).jpg)

Debido a los aranceles comerciales de Trump combinados con precios deprimidos de las materias primas, los agricultores estadounidenses enfrentaron la peor crisis en décadas. [154] Trump proporcionó a los agricultores $ 12 mil millones en pagos directos en julio de 2018 para mitigar los impactos negativos de sus aranceles, aumentando los pagos en $ 14.5 mil millones en mayo de 2019 después de que las conversaciones comerciales con China terminaran sin acuerdo. [155] La mayor parte de la ayuda de la administración se destinó a las granjas más grandes. [156] Politico informó en mayo de 2019 que algunos economistas del Departamento de Agricultura de los Estados Unidos estaban siendo castigados por presentar análisis que mostraban que los agricultores estaban siendo perjudicados por las políticas comerciales e impositivas de Trump, y seis economistas con más de 50 años de experiencia combinada en el Servicio renunciaron el mismo día. [157] El presupuesto fiscal 2020 de Trump propuso un recorte del 15% de la financiación para el Departamento de Agricultura, calificando los subsidios agrícolas de "demasiado generosos". [154]

La administración revocó una norma de la Oficina de Protección Financiera del Consumidor (CFPB) que había facilitado a los consumidores afectados presentar demandas colectivas contra los bancos; Associated Press calificó la revocación como una victoria para los bancos de Wall Street. [158] Bajo el mandato de Mick Mulvaney , la CFPB redujo la aplicación de las normas que protegían a los consumidores de los prestamistas depredadores de día de pago . [159] [160] Trump descartó una norma propuesta por la administración Obama que exigía a las aerolíneas que revelaran las tarifas de equipaje. [161] Trump redujo la aplicación de las regulaciones contra las aerolíneas; las multas impuestas por la administración en 2017 fueron menos de la mitad de lo que hizo la administración Obama el año anterior. [162]

El New York Times resumió el "enfoque general de la administración Trump para la aplicación de la ley" como "tomar medidas enérgicas contra el crimen violento", "no regular los departamentos de policía que lo combaten" y revisar "los programas que la administración Obama utilizó para aliviar las tensiones entre las comunidades y la policía". [163] Trump revocó la prohibición de proporcionar equipo militar federal a los departamentos de policía locales [164] y restableció el uso de la confiscación de activos civiles . [165] La administración declaró que ya no investigaría a los departamentos de policía ni publicaría sus deficiencias en los informes, una política promulgada previamente bajo la administración Obama. Más tarde, Trump afirmó falsamente que la administración Obama nunca intentó reformar la policía. [166] [167]

En diciembre de 2017, Sessions y el Departamento de Justicia anularon una directriz de 2016 que aconsejaba a los tribunales no imponer multas y honorarios elevados a los acusados pobres. [168]

.jpg/440px-The_36th_Annual_National_Peace_Officers'_Memorial_Service_(34535435862).jpg)

A pesar de la retórica pro-policía de Trump, su plan presupuestario de 2019 propuso recortes de casi el cincuenta por ciento al Programa de Contratación de COPS , que proporciona fondos a las agencias policiales estatales y locales para ayudar a contratar agentes de policía comunitarios. [169] Trump pareció defender la brutalidad policial en un discurso de julio de 2017 a los agentes de policía, lo que provocó críticas de las agencias policiales. [170] En 2020, el Inspector General del Departamento de Justicia criticó a la administración Trump por reducir la supervisión policial y erosionar la confianza pública en la aplicación de la ley. [171]

En diciembre de 2018, Trump firmó la Ley del Primer Paso , un proyecto de ley bipartidista de reforma de la justicia penal que buscaba rehabilitar a los presos y reducir la reincidencia, en particular ampliando los programas de capacitación laboral y liberación temprana, y reduciendo las sentencias mínimas obligatorias para los delincuentes no violentos relacionados con las drogas. [172]

El número de procesamientos de traficantes sexuales de menores ha mostrado una tendencia decreciente bajo la administración Trump en relación con el segundo mandato de la administración Obama. [173] [174] Bajo la administración Trump, la SEC presentó la menor cantidad de casos de tráfico de información privilegiada desde la administración Reagan. [175]

Durante su presidencia, Trump indultó o conmutó las sentencias de 237 personas. [176] La mayoría de los indultados tenían conexiones personales o políticas con Trump. [177] Un número significativo había sido condenado por fraude o corrupción pública. [178] Trump eludió el proceso típico de clemencia, no tomando ninguna medida sobre más de diez mil solicitudes pendientes, utilizando el poder de indulto principalmente en "figuras públicas cuyos casos resonaron con él dadas sus propias quejas con los investigadores". [179]

En mayo de 2017, en una desviación de la política del Departamento de Justicia bajo Obama de reducir las largas sentencias de cárcel por delitos menores de drogas y en contra de un creciente consenso bipartidista, la administración ordenó a los fiscales federales que buscaran la sentencia máxima para los delitos de drogas . [180] En una medida de enero de 2018 que creó incertidumbre con respecto a la legalidad de la marihuana recreativa y medicinal, Sessions rescindió una política federal que había prohibido a los funcionarios encargados de hacer cumplir la ley federal aplicar agresivamente la ley federal de cannabis en los estados donde la droga es legal. [181] La decisión de la administración contradijo la declaración del entonces candidato Trump de que la legalización de la marihuana debería ser "dependiente de los estados". [182] Ese mismo mes, el VA dijo que no investigaría el cannabis como un posible tratamiento contra el TEPT y el dolor crónico; las organizaciones de veteranos habían presionado para que se realizara un estudio de este tipo. [183] En diciembre de 2018, Trump firmó la Ley de Mejora de la Agricultura de 2018 , que incluía la desclasificación de ciertos productos de cannabis, lo que llevó a un aumento del Delta-8 legal , una medida que se asemejaba a la legalización. [184]

Entre julio de 2020 [185] y el final del mandato de Trump, el gobierno federal ejecutó a trece personas; las primeras ejecuciones desde 2002. [186] En este período, Trump supervisó más ejecuciones federales que cualquier presidente en los 120 años anteriores. [186]

Tres huracanes azotaron Estados Unidos en agosto y septiembre de 2017: Harvey en el sureste de Texas, Irma en la costa del Golfo de Florida y María en Puerto Rico. Trump firmó una ley de 15 mil millones de dólares en ayuda para Harvey e Irma, y luego 18.67 mil millones de dólares para los tres. [187] La administración fue criticada por su respuesta tardía a la crisis humanitaria en Puerto Rico. [188] Los políticos de ambos partidos habían pedido ayuda inmediata para Puerto Rico y criticaron a Trump por centrarse en una disputa con la Liga Nacional de Fútbol . [189] Trump no hizo comentarios sobre Puerto Rico durante varios días mientras se desarrollaba la crisis. [190] Según The Washington Post , la Casa Blanca no sintió una sensación de urgencia hasta que "las imágenes de la destrucción total y la desesperación, y las críticas a la respuesta de la administración, comenzaron a aparecer en la televisión". [191] Trump desestimó las críticas y dijo que la distribución de los suministros necesarios estaba "yendo bien". El Washington Post señaló que "en el terreno en Puerto Rico, nada podría estar más lejos de la verdad". [191] Trump también criticó a los funcionarios de Puerto Rico. [192] Un análisis de BMJ concluyó que el gobierno federal respondió mucho más rápidamente y en mayor escala al huracán en Texas y Florida que en Puerto Rico, a pesar de que el huracán en Puerto Rico fue más severo. [187] Una investigación del Inspector General de HUD de 2021 concluyó que la administración Trump erigió obstáculos burocráticos que paralizaron aproximadamente $20 mil millones en ayuda por el huracán para Puerto Rico. [193]

En el momento de la salida de FEMA de Puerto Rico, un tercio de los residentes de Puerto Rico todavía carecían de electricidad y algunos lugares carecían de agua corriente. [194] Un estudio del New England Journal of Medicine estimó que el número de muertes relacionadas con huracanes durante el período del 20 de septiembre al 31 de diciembre de 2017 fue de alrededor de 4600 (rango 793-8498) [195] La tasa de mortalidad oficial debido a María informada por el Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico es de 2975; la cifra se basó en una investigación independiente de la Universidad George Washington encargada por el gobernador de Puerto Rico. [196] Trump afirmó falsamente que la tasa de mortalidad oficial estaba equivocada y dijo que los demócratas estaban tratando de hacerlo "verse lo peor posible". [197]

Trump culpó engañosamente de los destructivos incendios forestales de 2018 en California a la "mala" y "grave" gestión de los bosques por parte de California, diciendo que no había otra razón para estos incendios forestales. Los incendios en cuestión no eran "incendios forestales"; la mayor parte del bosque era propiedad de agencias federales; y el cambio climático contribuyó en parte a los incendios. [198]

En septiembre de 2020, los peores incendios forestales de la historia de California llevaron a Trump a visitar el estado. En una reunión informativa con funcionarios estatales, Trump dijo que era necesaria la asistencia federal y volvió a afirmar sin fundamento que la falta de forestación , no el cambio climático, es la causa subyacente de los incendios. [199]

Las políticas económicas de Trump se han centrado en la reducción de impuestos, la desregulación y el proteccionismo comercial. Trump se mantuvo o intensificó las posiciones tradicionales de política económica republicana que beneficiaban a los intereses corporativos o a los ricos, con la excepción de sus políticas proteccionistas comerciales. [205] El gasto deficitario , combinado con recortes de impuestos para los ricos, provocó que la deuda nacional de Estados Unidos aumentara drásticamente. [206] [207] [208] [209]

Una de las primeras acciones de Trump fue suspender indefinidamente un recorte en las tasas de las hipotecas aseguradas por el gobierno federal implementado por la administración Obama, que les ahorraba a las personas con puntajes de crédito más bajos alrededor de $500 por año en un préstamo típico. [210] Al asumir el cargo, Trump detuvo las negociaciones comerciales con la Unión Europea sobre la Asociación Transatlántica de Comercio e Inversión , que había estado en marcha desde 2013. [211]

La administración propuso cambios al Programa de Asistencia Nutricional Suplementaria (cupones de alimentos), que de implementarse harían que millones de personas perdieran el acceso a los cupones de alimentos y limitarían la cantidad de beneficios para los beneficiarios restantes. [212]

Durante su mandato, Trump buscó repetidamente intervenir en la economía para afectar a empresas e industrias específicas. [213] Trump trató de obligar a los operadores de la red eléctrica a comprar carbón y energía nuclear, y buscó aranceles a los metales para proteger a los productores nacionales de metales. [213] Trump también atacó públicamente a Boeing y Lockheed Martin , haciendo caer sus acciones. [214] Trump criticó repetidamente a Amazon y abogó por medidas que dañarían a la empresa, como poner fin a un acuerdo entre Amazon y el Servicio Postal de los Estados Unidos (USPS) y aumentar los impuestos a Amazon. [215] [216] Trump expresó su oposición a la fusión entre Time Warner (la empresa matriz de CNN) y AT&T . [217]

La campaña de Trump se basó en una política de reducción del déficit comercial de Estados Unidos, en particular con China. [218] El déficit comercial general aumentó durante la presidencia de Trump. [219] El déficit de bienes con China alcanzó un máximo histórico por segundo año consecutivo en 2018. [220]

Un estudio de 2021, que utilizó el método de control sintético , no encontró evidencia de que Trump haya tenido un impacto en la economía estadounidense durante su mandato. [221] Un análisis realizado por Bloomberg News al final del segundo año de mandato de Trump encontró que su economía ocupó el sexto lugar entre los últimos siete presidentes, según catorce métricas de actividad económica y desempeño financiero. [222] Trump caracterizó repetida y falsamente a la economía durante su presidencia como la mejor en la historia de Estados Unidos. [223]

_(cropped).jpg/440px-Boeing_787-10_rollout_with_President_Trump_(32335755473)_(cropped).jpg)

En febrero de 2020, en medio de la pandemia de COVID-19 , Estados Unidos entró en recesión . [224] [225]

En septiembre de 2017, Trump propuso la reforma fiscal federal más radical en muchos años. [226] Trump firmó la legislación fiscal el 22 de diciembre de 2017, después de que fuera aprobada por el Congreso en votaciones partidarias. [227] [228] [229] El proyecto de ley fiscal fue la primera legislación importante firmada por Trump. [230] El proyecto de ley de 1,5 billones de dólares redujo la tasa impositiva federal corporativa del 35% al 21%, [228] su punto más bajo desde 1939. [229] El proyecto de ley también redujo la tasa impositiva individual, reduciendo la tasa máxima del 39,6% al 37%, aunque estos recortes de impuestos individuales expiran después de 2025; [228] como resultado, "para 2027, cada grupo de ingresos que gane menos de $75,000 vería un aumento impositivo neto". [230] El proyecto de ley duplicó la exención del impuesto al patrimonio (a $22 millones para parejas casadas); y permitió a los propietarios de empresas de transferencia deducir el 20% de los ingresos comerciales. [228] El proyecto de ley duplicó la deducción estándar al tiempo que eliminó muchas deducciones detalladas , [230] incluida la deducción por impuestos estatales y locales. [228] El proyecto de ley también repitió el mandato de seguro médico individual contenido en la Ley de Atención Médica Asequible . [230]

Según The New York Times , el plan resultaría en una "enorme ganancia inesperada" para los muy ricos, pero no beneficiaría a los que están en el tercio inferior de la distribución del ingreso. [226] El Centro de Política Fiscal no partidista estimó que el 0,1% y el 1% más ricos serían los que más se beneficiarían en cantidades brutas en dólares y en términos porcentuales del plan fiscal, ganando un 10,2% y un 8,5% más de ingresos después de impuestos respectivamente. [231] Los hogares de clase media ganarían en promedio un 1,2% más después de impuestos, pero el 13,5% de los hogares de clase media verían aumentar su carga fiscal. [231] El quinto más pobre de los estadounidenses ganaría un 0,5% más. [231] El secretario del Tesoro, Steven Mnuchin, argumentó que el recorte del impuesto sobre la renta corporativa beneficiaría más a los trabajadores, mientras que el Comité Conjunto sobre Tributación no partidista , la Oficina de Presupuesto del Congreso y muchos economistas estimaron que los propietarios de capital se beneficiarían mucho más que los trabajadores. [232] Una estimación preliminar del Comité para un Presupuesto Federal Responsable concluyó que el plan fiscal añadiría más de 2 billones de dólares a la deuda federal en la próxima década, [233] mientras que el Centro de Política Fiscal concluyó que añadiría 2,4 billones de dólares a la deuda. [231] Un análisis del Servicio de Investigación del Congreso de 2019 concluyó que los recortes de impuestos tuvieron un efecto de crecimiento "relativamente pequeño (si es que hubo alguno) en el primer año" sobre la economía. [234] Un análisis de 2019 del Comité para un Presupuesto Federal Responsable concluyó que las políticas de Trump añadirán 4,1 billones de dólares a la deuda nacional entre 2017 y 2029. Se prevé que la Ley de Empleos y Reducción de Impuestos de 2017 genere una deuda de alrededor de 1,8 billones de dólares. [235]

.jpg/440px-President_Donald_J._Trump_at_the_G20_Summit_(44300765490).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Signing_Ceremony_Phase_One_Trade_Deal_Between_the_U.S._&_China_(49391434906).jpg)

En marzo de 2018, Trump impuso aranceles a los paneles solares y las lavadoras del 30 al 50%. [236] En marzo de 2018, impuso aranceles al acero (25%) y al aluminio (10%) de la mayoría de los países, [237] [238] que cubrían aproximadamente el 4,1% de las importaciones estadounidenses. [239] El 1 de junio de 2018, esto se extendió a la Unión Europea , Canadá y México . [238] En movimientos separados, la administración Trump estableció y aumentó los aranceles a los bienes importados de China , lo que llevó a una guerra comercial . [240] Los aranceles enfurecieron a los socios comerciales, quienes implementaron aranceles de represalia sobre los bienes estadounidenses, [241] y afectaron negativamente el ingreso real y el PIB. [242] Un análisis de la CNBC concluyó que Trump "aplicó aranceles equivalentes a uno de los mayores aumentos de impuestos en décadas", mientras que los análisis de la Tax Foundation y el Tax Policy Center concluyeron que los aranceles podrían acabar con los beneficios de la Ley de Reducción de Impuestos y Empleos de 2017 para muchos hogares. [243] [244] Los dos países llegaron a un acuerdo de tregua de "fase uno" en enero de 2020. La mayor parte de los aranceles se mantuvieron vigentes hasta que se reanudaron las conversaciones después de las elecciones de 2020. Trump proporcionó 28.000 millones de dólares en ayuda en efectivo a los agricultores afectados por la guerra comercial. [245] [246] [247] Los estudios han descubierto que los aranceles también afectaron negativamente a los candidatos republicanos en las elecciones. [248] Un análisis publicado por The Wall Street Journal en octubre de 2020 concluyó que la guerra comercial no logró el objetivo principal de revivir la industria manufacturera estadounidense, ni resultó en la relocalización de la producción fabril. [249]

Tres semanas después de que el senador republicano Chuck Grassley , presidente del Comité de Finanzas del Senado , escribiera un artículo de opinión en el Wall Street Journal en abril de 2019 titulado "Los aranceles de Trump terminan o su acuerdo comercial muere", afirmando que "el Congreso no aprobará el T-MEC mientras los electores paguen el precio de las represalias mexicanas y canadienses", Trump levantó los aranceles al acero y al aluminio en México y Canadá. [250] Dos semanas después, Trump anunció inesperadamente que impondría un arancel del 5% a todas las importaciones de México el 10 de junio, aumentando al 10% el 1 de julio, y en otro 5% cada mes durante tres meses, "hasta que los inmigrantes ilegales que pasan por México y entran a nuestro país, DEJEN DE TRAER". [251] Grassley comentó la medida como un "mal uso de la autoridad arancelaria presidencial y contrario a la intención del Congreso". [252] Ese mismo día, la administración Trump inició formalmente el proceso para buscar la aprobación del Congreso del T-MEC. [253] El principal asesor comercial de Trump, el Representante Comercial de Estados Unidos Robert Lighthizer , se opuso a los nuevos aranceles mexicanos por temor a que pondrían en peligro la aprobación del T-MEC. [254] El secretario del Tesoro Steven Mnuchin y el asesor principal de Trump Jared Kushner también se opusieron a la acción. Grassley, cuyo comité es fundamental para la aprobación del T-MEC, no fue informado con antelación del sorpresivo anuncio de Trump. [255] El 7 de junio, Trump anunció que los aranceles serían "suspendidos indefinidamente" después de que México aceptara tomar medidas, incluido el despliegue de su Guardia Nacional en todo el país y a lo largo de su frontera sur. [256] El New York Times informó al día siguiente que México había aceptado la mayoría de las acciones meses antes. [257]

Como candidato presidencial en 2016, Trump se comprometió a retirarse del Acuerdo Transpacífico , un acuerdo comercial con once naciones de la Cuenca del Pacífico que Estados Unidos había firmado a principios de ese año. China no era parte del acuerdo, que tenía como objetivo permitir a Estados Unidos guiar las relaciones comerciales en la región. Afirmó incorrectamente que el acuerdo era defectuoso porque contenía una "puerta trasera" que permitiría a China ingresar al acuerdo más tarde. Trump anunció la retirada estadounidense del acuerdo días después de asumir el cargo. Tras la retirada estadounidense, los socios restantes lo rebautizaron como Acuerdo Integral y Progresivo para la Asociación Transpacífica . En septiembre de 2021, China solicitó formalmente unirse a ese acuerdo en un esfuerzo por reemplazar a Estados Unidos como su centro; el Global Times, administrado por el estado chino , dijo que la medida "consolidaría el liderazgo del país en el comercio global" y dejaría a Estados Unidos "cada vez más aislado". [258] [259]

Trump nombró a Betsy DeVos como su Secretaria de Educación. Su nominación fue confirmada en una votación de 50-50 en el Senado, y se le pidió al vicepresidente Pence que desempatara el voto (la primera vez que un vicepresidente emitía un voto de desempate en una nominación del Gabinete). [260] Los demócratas se opusieron a DeVos por considerar que no estaba calificada, mientras que los republicanos la apoyaron debido a su fuerte apoyo a la libertad de elección de escuelas . [260]

En 2017, Trump revocó un memorando de la administración Obama que brindaba protección a las personas en mora con los préstamos estudiantiles . [261] El Departamento de Educación de los Estados Unidos canceló los acuerdos con la Oficina de Protección Financiera del Consumidor (CFPB) para vigilar el fraude en los préstamos estudiantiles. [262] La administración rescindió una regulación que restringía la financiación federal a las universidades con fines de lucro que no pudieran demostrar que los graduados universitarios tenían una relación deuda-ingresos razonable después de ingresar al mercado laboral. [263] Seth Frotman, el defensor del pueblo de préstamos estudiantiles de la CFPB, renunció, acusando a la administración Trump de socavar el trabajo de la CFPB para proteger a los prestatarios estudiantiles. [264] DeVos marginó a una unidad de investigación dentro del Departamento de Educación que, bajo el mandato de Obama, investigó las actividades depredadoras de las universidades con fines de lucro. Una investigación iniciada durante el gobierno de Obama sobre las prácticas de DeVry Education Group , que opera universidades con fines de lucro, se detuvo a principios de 2017, y el ex decano de DeVry fue nombrado supervisor de la unidad de investigación más tarde ese verano. DeVry pagó una multa de 100 millones de dólares en 2016 por estafar a los estudiantes. [265]

En 2017, la administración revirtió una directriz de la administración Obama sobre cómo las escuelas y universidades deberían combatir el acoso sexual y la violencia sexual . [266] [267]

En vísperas de las elecciones intermedias de 2018, Politico calificó de “inconstantes” los esfuerzos de la administración Trump para combatir la propaganda electoral. Al mismo tiempo, las agencias de inteligencia estadounidenses advirtieron sobre “campañas en curso” de Rusia, China e Irán para influir en las elecciones estadounidenses. [268]

El " Plan de Energía América Primero " de la administración no mencionó la energía renovable y en su lugar se centró en los combustibles fósiles . [269] La administración promulgó aranceles del 30% sobre los paneles solares importados . La industria de energía solar estadounidense depende en gran medida de piezas extranjeras (el 80% de las piezas se fabrican en el extranjero); como resultado, los aranceles podrían aumentar los costos de la energía solar , reducir la innovación y reducir los empleos en la industria, que en 2017 empleó casi cuatro veces más trabajadores estadounidenses que la industria del carbón. [270] [271] La administración revirtió las normas establecidas para hacer que las bombillas de uso común sean más eficientes energéticamente. [272]

Trump anuló una norma que requería que las empresas de petróleo, gas y minería revelaran cuánto pagaban a los gobiernos extranjeros, [273] y se retiró de la Iniciativa Internacional para la Transparencia de las Industrias Extractivas (EITI) que requería la divulgación de los pagos de las empresas de petróleo, gas y minería a los gobiernos. [274]

En 2017, Trump ordenó la revocación de una prohibición de la era Obama sobre nuevas concesiones de petróleo y gas en el Océano Ártico y áreas ambientalmente sensibles de la costa del Atlántico Norte , en la Plataforma Continental Exterior . [275] La orden de Trump fue detenida por un tribunal federal, que dictaminó en 2019 que excedía ilegalmente su autoridad. [275] Trump también revocó la Regla de Control de Pozos de 2016, una regulación de seguridad adoptada después del derrame de petróleo de Deepwater Horizon ; esta acción es objeto de impugnaciones legales por parte de grupos ambientalistas. [276] [277] [278]

En enero de 2018, la administración destacó a Florida para la exención del plan de perforación en alta mar de la administración. La medida generó controversia porque se produjo después de que el gobernador de Florida, Rick Scott , que estaba considerando postularse al Senado en 2018 , se quejara del plan. La medida planteó cuestiones éticas sobre la apariencia de "favoritismo transaccional" porque Trump posee un complejo turístico costero en Florida y debido al estatus del estado como un " estado clave " crucial en las elecciones presidenciales de 2020. [279] Otros estados buscaron exenciones de perforación en alta mar similares, [280] y se produjeron litigios. [281] [282]

A pesar de la retórica sobre el impulso a la industria del carbón, la capacidad de generación de electricidad a partir de carbón disminuyó más rápido durante la presidencia de Trump que durante cualquier mandato presidencial anterior, cayendo un 15% con la paralización de 145 unidades de combustión de carbón en 75 centrales eléctricas. Se estima que el 20% de la electricidad se generaría a partir de carbón en 2020, en comparación con el 31% en 2017. [283]

En octubre de 2020, la administración había revocado 72 regulaciones ambientales y estaba en proceso de revertir otras 27. [284] Un estudio de 2018 del American Journal of Public Health encontró que en los primeros seis meses de Trump en el cargo, la Agencia de Protección Ambiental de los Estados Unidos adoptó una actitud pro-empresarial diferente a la de cualquier administración anterior, ya que "se alejó del interés público y favoreció explícitamente los intereses de las industrias reguladas". [285]

Los análisis de los datos de aplicación de la EPA mostraron que la administración Trump presentó menos casos contra los contaminadores, buscó un total menor de sanciones civiles e hizo menos solicitudes a las empresas para modernizar las instalaciones para frenar la contaminación que las administraciones de Obama y Bush. Según The New York Times , "documentos internos confidenciales de la EPA muestran que la desaceleración de la aplicación coincide con importantes cambios de política ordenados por el equipo del Sr. Pruitt después de las súplicas de los ejecutivos de la industria del petróleo y el gas". [286] En 2018, la administración remitió el menor número de casos de contaminación para procesamiento penal en 30 años. [287] Dos años después de la presidencia de Trump, The New York Times escribió que había "desatado un retroceso regulatorio, presionado y aplaudido por la industria, con poco paralelo en el último medio siglo". [288] En junio de 2018, David Cutler y Francesca Dominici de la Universidad de Harvard estimaron de manera conservadora que las modificaciones de la administración Trump a las normas ambientales podrían resultar en más de 80.000 muertes adicionales en Estados Unidos y enfermedades respiratorias generalizadas. [289] En agosto de 2018, el propio análisis de la administración mostró que la flexibilización de las normas sobre las plantas de carbón podría causar hasta 1.400 muertes prematuras y 15.000 nuevos casos de problemas respiratorios. [290] Entre 2016 y 2018, la contaminación del aire aumentó un 5,5%, revirtiendo una tendencia de siete años en la que la contaminación del aire había disminuido un 25%. [291]

Todas las referencias al cambio climático fueron eliminadas del sitio web de la Casa Blanca, con la única excepción de mencionar la intención de Trump de eliminar las políticas de cambio climático de la administración Obama . [292] La EPA eliminó el material sobre el cambio climático de su sitio web, incluidos datos climáticos detallados . [293] En junio de 2017, Trump anunció la retirada de Estados Unidos del Acuerdo de París , un acuerdo sobre el cambio climático de 2015 alcanzado por 200 naciones para reducir las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero . [294] En diciembre de 2017, Trump, que había calificado repetidamente el consenso científico sobre el clima como un "engaño" antes de convertirse en presidente, insinuó falsamente que el clima frío significaba que el cambio climático no estaba ocurriendo. [295] A través de una orden ejecutiva, Trump revirtió múltiples políticas de la administración Obama destinadas a abordar el cambio climático, como una moratoria sobre el arrendamiento federal de carbón, el Plan de Acción Climática Presidencial y la orientación para las agencias federales sobre cómo tener en cuenta el cambio climático durante las revisiones de acciones de la Ley de Política Ambiental Nacional . Trump también ordenó revisiones y posiblemente modificaciones a varias directivas, como el Plan de Energía Limpia (CPP), la estimación del " costo social de las emisiones de carbono", los estándares de emisión de dióxido de carbono para nuevas plantas de carbón , los estándares de emisiones de metano de la extracción de petróleo y gas natural , así como cualquier regulación que inhiba la producción energética nacional. [296] La administración revocó las regulaciones que requerían que el gobierno federal tuviera en cuenta el cambio climático y el aumento del nivel del mar al construir infraestructura. [297] La EPA disolvió un panel de 20 expertos sobre contaminación que asesoraba a la EPA sobre los niveles de umbral apropiados para establecer para los estándares de calidad del aire. [298]

.jpg/440px-Scott_Pruitt_official_portrait_(cropped).jpg)

La administración ha buscado repetidamente reducir el presupuesto de la EPA. [299] La administración invalidó la Regla de Protección de Arroyos , que limitaba el vertido de aguas residuales tóxicas que contenían metales, como arsénico y mercurio, en vías fluviales públicas, [300] regulaciones sobre cenizas de carbón (residuos cancerígenos sobrantes producidos por plantas de carbón), [301] y una orden ejecutiva de la era Obama sobre protecciones para océanos, costas y lagos promulgada en respuesta al derrame de petróleo de Deepwater Horizon . [302] La administración se negó a actuar sobre las recomendaciones de los científicos de la EPA que instan a una mayor regulación de la contaminación por partículas . [303]

La administración revocó importantes protecciones de la Ley de Agua Limpia , restringiendo la definición de las " aguas de los Estados Unidos " bajo protección federal. [304] Los estudios de la EPA de la era Obama sugieren que hasta dos tercios de los arroyos de agua dulce interiores de California perderían protecciones bajo el cambio de regla. [305] La EPA buscó derogar una regulación que requería que las compañías de petróleo y gas restringieran las emisiones de metano , un potente gas de efecto invernadero . [306] La EPA revocó los estándares de eficiencia de combustible de automóviles introducidos en 2012. [307] La EPA otorgó un vacío legal que permite a un pequeño grupo de compañías de camiones eludir las reglas de emisiones y producir camiones planeadores que emiten entre 40 y 55 veces más contaminantes del aire que otros camiones nuevos. [308] La EPA rechazó una prohibición del pesticida tóxico clorpirifos ; un tribunal federal luego ordenó a la EPA prohibir el clorpirifos, porque la propia investigación extensa de la EPA mostró que causaba efectos adversos para la salud en los niños. [288] La administración redujo la prohibición del uso del solvente cloruro de metileno , [309] y levantó una norma que requería que las grandes granjas informaran sobre la contaminación emitida por los desechos animales. [310]

La administración suspendió la financiación de varios estudios de investigación medioambiental , [311] [312] un programa multimillonario que distribuía subvenciones para la investigación de los efectos de la exposición a sustancias químicas en los niños [313] [314] y una línea de investigación de 10 millones de dólares al año para el Sistema de Monitoreo de Carbono de la NASA . [315] incluido un intento fallido de eliminar aspectos del programa de ciencia climática de la NASA . [315]

La EPA aceleró el proceso de aprobación de nuevos productos químicos e hizo menos estricto el proceso de evaluación de la seguridad de esos productos; los científicos de la EPA expresaron su preocupación por el hecho de que se estaba comprometiendo la capacidad de la agencia para detener los productos químicos peligrosos. [316] [317] Los correos electrónicos internos mostraron que los ayudantes de Pruitt impidieron la publicación de un estudio de salud que mostraba que algunos productos químicos tóxicos ponen en peligro a los seres humanos en niveles mucho más bajos que los que la EPA había caracterizado previamente como seguros. [318] Uno de esos productos químicos estaba presente en grandes cantidades alrededor de varias bases militares, incluidas las aguas subterráneas. [318] La no divulgación del estudio y la demora en el conocimiento público de los hallazgos pueden haber impedido que el gobierno actualizara la infraestructura en las bases y a las personas que vivían cerca de las bases para evitar el agua del grifo. [318]

La administración debilitó la aplicación de la Ley de Especies en Peligro de Extinción , facilitando el inicio de proyectos de minería, perforación y construcción en áreas con especies en peligro de extinción y amenazadas. [319] [320] La administración ha desalentado activamente a los gobiernos locales y a las empresas a emprender esfuerzos de preservación. [320]

La administración redujo drásticamente el tamaño de dos monumentos nacionales en Utah en aproximadamente dos millones de acres, lo que la convirtió en la mayor reducción de protecciones de tierras públicas en la historia de Estados Unidos. [321] Poco después, el secretario del Interior Ryan Zinke abogó por reducir el tamaño de cuatro monumentos nacionales adicionales y cambiar la forma en que se gestionaban seis monumentos adicionales. [322] En 2019, la administración aceleró el proceso de revisiones ambientales para la perforación de petróleo y gas en el Ártico; los expertos dijeron que la aceleración hizo que las revisiones fueran menos completas y confiables. [323] Según Politico , la administración aceleró el proceso en caso de que se eligiera una administración demócrata en 2020, lo que habría detenido nuevos arrendamientos de petróleo y gas en el Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre del Ártico . [323] La administración buscó abrir más de 180.000 acres del Bosque Nacional Tongass en Alaska, el más grande del país, para la tala. [324]

En abril de 2018, Pruitt anunció un cambio de política que prohíbe a los reguladores de la EPA considerar la investigación científica a menos que los datos brutos de la investigación se hagan públicos. Esto limitaría el uso por parte de los reguladores de la EPA de gran parte de la investigación ambiental, dado que los participantes en muchos de esos estudios proporcionan información sanitaria personal que se mantiene confidencial. [325] La EPA citó dos informes bipartidistas y varios estudios no partidistas sobre el uso de la ciencia en el gobierno para defender la decisión. Sin embargo, los autores de esos informes descartaron que la EPA siguiera sus instrucciones, y un autor dijo: "No adoptan ninguna de nuestras recomendaciones y van en una dirección opuesta, completamente diferente. No adoptan ninguna de las recomendaciones de ninguna de las fuentes que citan". [326]

En julio de 2020, Trump intentó debilitar la Ley Nacional de Política Ambiental al limitar la revisión pública para acelerar la concesión de permisos. [327] En agosto de 2020, Trump firmó la Ley Great American Outdoors para financiar completamente el Fondo de Conservación de Tierras y Aguas . Tenía la intención de oponerse al proyecto de ley y vaciar el fondo hasta que los senadores republicanos, temerosos de perder sus candidaturas a la reelección, y la mayoría del Senado cambiaran de opinión. [328] [329]

La administración impuso muchas menos sanciones financieras contra los bancos y las grandes empresas acusadas de malas prácticas que la administración Obama. [330]

En las primeras seis semanas de su mandato, Trump suspendió –o en algunos casos, revocó– más de 90 regulaciones. [331] A principios de 2017, Trump firmó una orden ejecutiva que ordenaba a las agencias federales recortar dos regulaciones existentes por cada nueva (sin aumentar el gasto en regulaciones). [332] Una revisión de Bloomberg BNA de septiembre de 2017 encontró que debido a la redacción poco clara de la orden y la gran proporción de regulaciones que exime, la orden había tenido poco efecto desde que se firmó. [333] La OMB de Trump publicó un análisis en febrero de 2018 que indicaba que los beneficios económicos de las regulaciones superan significativamente los costos económicos. [334] La administración ordenó que se eliminara un tercio de los comités asesores gubernamentales para las agencias federales, excepto los comités que evalúan la seguridad de los productos de consumo o los comités que aprueban las subvenciones de investigación. [335]

Trump ordenó una congelación de las contrataciones de personal civil en todo el gobierno durante cuatro meses al comienzo de su mandato (excluyendo al personal militar, de seguridad nacional, de seguridad pública y a las oficinas de los nuevos designados presidenciales). [336] Dijo que no tenía intención de cubrir muchos de los puestos gubernamentales que todavía estaban vacantes, ya que los consideraba innecesarios; [337] había casi 2.000 puestos gubernamentales vacantes. [338]

La administración puso fin al requisito de que las organizaciones sin fines de lucro, incluidos los grupos de defensa política que recaudan el llamado dinero oscuro , revelen los nombres de los grandes donantes al IRS ; el Senado votó para revocar el cambio de regla de la administración. [339]

La administración prohibió los bump stocks después de que dichos dispositivos fueran utilizados por el pistolero que perpetró el tiroteo de Las Vegas de 2017. [ 340] A raíz de varios tiroteos masivos durante la administración Trump, incluidos los tiroteos de agosto de 2019 en El Paso, Texas , y Dayton, Ohio , Trump pidió a los estados que implementaran leyes de bandera roja para retirar las armas de "aquellos que se considere que representan un grave riesgo para la seguridad pública". [341] En noviembre de 2019, abandonó la idea de las leyes de bandera roja. [342] Trump derogó una regulación que prohibía la posesión de armas a aproximadamente 75.000 personas que recibieron cheques de la Seguridad Social debido a enfermedades mentales y que se consideraban no aptas para manejar sus asuntos financieros. [343] La administración puso fin a la participación de Estados Unidos en el Tratado sobre el Comercio de Armas de la ONU para frenar el comercio internacional de armas convencionales con países que tienen malos antecedentes en materia de derechos humanos. [344]

.jpg/440px-Alex_Azar_official_portrait_(cropped).jpg)

La Ley de Atención Médica Asequible de 2010 (también conocida como "Obamacare" o ACA) provocó una importante oposición del Partido Republicano desde su inicio, y Trump pidió la derogación de la ley durante la campaña electoral de 2016. [346] Al asumir el cargo, Trump prometió aprobar un proyecto de ley de atención médica que cubriría a todos y daría como resultado un seguro mejor y menos costoso. [347] [42] A lo largo de su presidencia, Trump afirmó repetidamente que su administración y los republicanos en el Congreso apoyaban las protecciones para las personas con condiciones preexistentes; sin embargo, los verificadores de hechos notaron que la administración apoyó los intentos tanto en el Congreso como en los tribunales de revertir la ACA (y sus protecciones para las condiciones preexistentes ). [348] [349] [350] [351]

Los republicanos del Congreso hicieron dos esfuerzos serios para derogar la ACA. Primero, en marzo de 2017, Trump respaldó la Ley de Atención Médica Estadounidense (AHCA) , un proyecto de ley republicano para derogar y reemplazar la ACA. [352] La oposición de varios republicanos de la Cámara, tanto moderados como conservadores, llevó a la derrota de esta versión del proyecto de ley. [352] En segundo lugar, en mayo de 2017, la Cámara votó por un estrecho margen a favor de una nueva versión de la AHCA para derogar la ACA, enviando el proyecto de ley al Senado para su deliberación. [352] Durante las siguientes semanas, el Senado hizo varios intentos de crear un proyecto de ley de derogación; sin embargo, todas las propuestas fueron finalmente rechazadas en una serie de votaciones del Senado a fines de julio. [352] El mandato individual fue derogado en diciembre de 2017 por la Ley de Reducción de Impuestos y Empleos . En mayo de 2018, la Oficina de Presupuesto del Congreso estimó que la derogación del mandato individual aumentaría el número de personas sin seguro en ocho millones y que las primas de seguro de salud individuales habían aumentado un diez por ciento entre 2017 y 2018. [353] Posteriormente, la administración se puso del lado de una demanda para revocar la ACA, incluidas las protecciones para las personas con condiciones preexistentes. [354]

Trump repeatedly expressed a desire to "let Obamacare fail",[355] and the Trump administration undermined Obamacare through various actions.[356] The open enrollment period was cut from twelve weeks to six, the advertising budget for enrollment was cut by 90%, and organizations helping people shop for coverage got 39% less money.[357][358][359] The CBO found that ACA enrollment at health care exchanges would be lower than its previous forecasts due to the Trump administration's undermining of the ACA.[357] A 2019 study found that enrollment into the ACA during the Trump administration's first year was nearly thirty percent lower than during 2016.[360] The CBO found that insurance premiums would rise sharply in 2018 due to the Trump administration's refusal to commit to continuing paying ACA subsidies, which added uncertainty to the insurance market and led insurers to raise premiums for fear they will not get subsidized.[357]

The administration ended subsidy payments to health insurance companies, in a move expected to raise premiums in 2018 for middle-class families by an average of about twenty percent nationwide and cost the federal government nearly $200 billion more than it saved over a ten-year period.[361] The administration made it easier for businesses to use health insurance plans not covered by several of the ACA's protections, including for preexisting conditions,[349] and allowed organizations not to cover birth control.[362] In justifying the action, the administration made false claims about the health harms of contraceptives.[363]

The administration proposed substantial spending cuts to Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security Disability Insurance. Trump had previously vowed to protect Medicare and Medicaid.[364][365] The administration reduced enforcement of penalties against nursing homes that harm residents.[366] As a candidate and throughout his presidency, Trump said he would cut the costs of pharmaceuticals. During his first seven months in office, there were 96 price hikes for every drug price cut.[367] Abandoning a promise he made as candidate, Trump announced he would not allow Medicare to use its bargaining power to negotiate lower drug prices.[368]

Trump reinstated the Mexico City policy, also known as the global gag rule, prohibiting funding to foreign non-governmental organizations that perform abortions as a method of family planning in other countries.[369] The administration implemented a policy restricting taxpayer dollars given to family planning facilities that mention abortion to patients, provide abortion referrals, or share space with abortion providers.[370][371] As a result, Planned Parenthood, which provides Title X birth control services to 1.5 million women, withdrew from the program.[372] Throughout his presidency, Trump pressed for a ban on late-term abortions and made frequent false claims about them.[373][374][375]

In 2018, the administration prohibited scientists at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) from acquiring new fetal tissue for research,[376] and a year later stopped all medical research by government scientists that used fetal tissue.[377]

The administration geared HHS funding towards abstinence education programs for teens rather than the comprehensive sexual education programs the Obama administration funded.[378]

Trump's Supreme Court nominees, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett voted to overturn Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization. Trump took credit for the decision, which threw abortion rights back to the states.[379]

Trump nominated Tom Marino to become the nation's drug czar but the nomination was withdrawn after an investigation found he had been the chief architect of a bill that crippled the enforcement powers of the Drug Enforcement Administration and worsened the opioid crisis.[380]

Kellyanne Conway led White House efforts to combat the opioid epidemic; Conway had no experience or expertise on matters of public health, substance abuse, or law enforcement.[381] Conway sidelined drug experts and opted instead for the use of political staff. Politico wrote in 2018 that the administration's "main response" to the opioid crisis "so far has been to call for a border wall and to promise a 'just say no' campaign".[381]

In October 2017, the administration declared a 90-day public health emergency over the opioid epidemic and pledged to urgently mobilize the federal government in response to the crisis. On January 11, 2018, twelve days before the declaration ran out, Politico noted that "beyond drawing more attention to the crisis, virtually nothing of consequence has been done."[382] The administration had not proposed any new resources or spending, had not started the promised advertising campaign to spread awareness about addiction, and had yet to fill key public health and drug positions in the administration.[382] One of the top officials at the Office of National Drug Control Policy, which is tasked with multi-billion-dollar anti-drug initiatives and curbing the opioid epidemic, was a 24-year old campaign staffer from the Trump 2016 campaign who lied on his CV and whose stepfather went to jail for manufacturing illegal drugs; after the administration was contacted about the official's qualifications and CV, the administration gave him a job with different tasks.[383]