Vilna ( / ˈ v ɪ l n i ə s / VIL -nee-əs , lituano: [ˈvʲɪlʲnʲʊs] ), anteriormente conocida en español comoVilna, es la capital yla ciudad más grandedeLituaniay lasegunda ciudad más pobladade losestados bálticos. La población estimada de la ciudad en julio de 2024 era de 605 270 habitantes, y elárea urbana de Vilna(que se extiende más allá de los límites de la ciudad) tiene una población estimada de 708 627 habitantes.[15]

Vilna es conocida por la arquitectura de su casco antiguo , considerado uno de los más grandes y mejor conservados de Europa . La ciudad fue declarada Patrimonio de la Humanidad por la UNESCO en 1994. [16] [17] [18] [19] El estilo arquitectónico conocido como barroco de Vilna recibe su nombre de la ciudad, que es la ciudad barroca más oriental y la más grande de este estilo al norte de los Alpes . [20] [21]

La ciudad se destacó por su población multicultural durante la Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania , y fuentes contemporáneas la comparan con Babilonia . Antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial y el Holocausto , Vilna era uno de los centros judíos más importantes de Europa. Su influencia judía ha llevado a que se la llame "la Jerusalén de Lituania", y Napoleón la llamó "la Jerusalén del Norte" [22] cuando pasó por allí en 1812.

Vilna fue Capital Europea de la Cultura en 2009 junto con Linz en Austria. [23] En 2021, la ciudad fue nombrada una de las 25 Ciudades Globales del Futuro de fDi . [24] Vilna es considerada un centro financiero global, ocupando el puesto 76 a nivel mundial y el 29 en Europa en el Índice de Centros Financieros Globales . [25] Fue sede de la Cumbre de la OTAN de 2023. Vilna es miembro de Eurocities [26] y de la Unión de Capitales de la Unión Europea (UCEU). [27]

El nombre de Vilna proviene del río Vilnia , la palabra lituana para onda . [28] Su nombre ha tenido varias grafías derivadas en varios idiomas a lo largo de su historia; Vilna alguna vez fue común en inglés. Los nombres no lituanos más notables para la ciudad incluyen latín : Vilna , polaco : Wilno , bielorruso : Вiльня ( Vilnia ), ‹Ver Tfd› alemán : Wilna , letón : Viļņa , ucraniano : Вільно ( Vilno ), yiddish : ווילנע ( Vilne ). Un nombre ruso que data del Imperio ruso era Вильна ( Vilna ), [29] [30] aunque ahora se usa Вильнюс ( Vilnyus ). Los nombres Wilno , Wilna y Vilna se usaron en publicaciones en inglés, alemán, francés e italiano cuando la ciudad era la capital de la Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania y una ciudad importante en la Segunda República Polaca . El nombre Vilna todavía se usa en finés, portugués, español y hebreo : וילנה . Wilna todavía se usa en alemán con Vilnius .

.jpg/440px-Painting_depicting_the_Lithuanian_Grand_Duke_Gediminas'_dream_about_an_Iron_Wolf_(painted_by_Aleksander_Lesser_in_1835).jpg)

Según una leyenda registrada alrededor de 1530 , el Gran Duque Gediminas ( c. 1275-1341 ) estaba cazando en el bosque sagrado cerca del valle de Šventaragis (donde el Vilnia desemboca en el río Neris ). La exitosa caza del bisonte duró más de lo esperado y Gediminas decidió pasar la noche en el valle. Se quedó dormido y soñó con un enorme Lobo de Hierro en la cima de una colina, aullando fuerte. Al despertar, el Duque le pidió al krivis Lizdeika que interpretara el sueño. El sumo sacerdote le dijo:

Lo que está destinado al gobernante y al Estado de Lituania es lo siguiente: el Lobo de Hierro representa un castillo y una ciudad que usted establecerá en este sitio. Esta ciudad será la capital de las tierras lituanas y la residencia de sus gobernantes , y la gloria de sus hazañas se hará eco en todo el mundo.

Gediminas, obedeciendo a los dioses , construyó dos castillos: el Castillo Inferior en el valle y el Castillo Torcido en la Colina Calva . Trasladó allí su corte, la declaró su sede y capital permanente y desarrolló el área circundante hasta convertirla en una ciudad a la que llamó Vilna. [31] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ] [32]

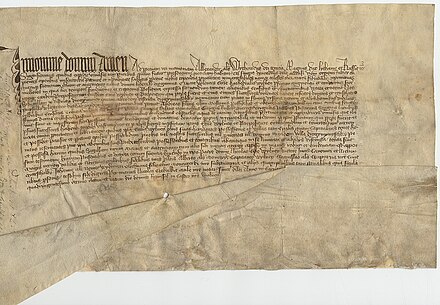

.jpg/440px-Transcript_of_Gediminas'_letter,_which_is_the_oldest_known_mentioning_of_Vilnius_in_written_sources_(25_January_1323).jpg)

La historia de Vilna se remonta a la Edad de Piedra . La ciudad ha estado gobernada por la Rusia imperial y soviética , la Francia napoleónica , la Alemania imperial y nazi , la Polonia de entreguerras y Lituania.

Inicialmente un asentamiento báltico, Vilna se volvió importante en el Gran Ducado de Lituania . La ciudad fue mencionada por primera vez en cartas del Gran Duque Gediminas, quien invitó a judíos y alemanes a establecerse y construyó un castillo de madera en una colina. Vilna se convirtió en ciudad en 1387, después de la cristianización de Lituania, y fue poblada por artesanos y comerciantes de una variedad de nacionalidades que se establecieron en la ciudad. Fue la capital del Gran Ducado (hasta 1795) y de la Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania . Vilna floreció bajo la mancomunidad, especialmente después del establecimiento de la Universidad de Vilna en 1579 por el rey Esteban Báthory . La ciudad se convirtió en un centro cultural y científico, atrayendo inmigrantes del este y el oeste. Tenía comunidades diversas, con poblaciones judías, ortodoxas y alemanas. La ciudad experimentó una serie de invasiones y ocupaciones, incluidas las de los Caballeros Teutónicos , Rusia y, más tarde, Alemania.

Bajo el dominio imperial ruso, Vilna se convirtió en la capital de la Gobernación de Vilna y vivió una serie de resurgimientos culturales durante los siglos XIX y principios del XX por parte de judíos, polacos, lituanos y bielorrusos. Después de la Primera Guerra Mundial , la ciudad experimentó un conflicto entre Polonia y Lituania que llevó a su ocupación por parte de Polonia antes de su anexión por parte de la Unión Soviética durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Después de esa guerra, Vilna se convirtió en la capital de la República Socialista Soviética de Lituania .

El 11 de marzo de 1990, el Consejo Supremo de la RSS de Lituania anunció su secesión de la Unión Soviética y su intención de restaurar una Lituania independiente. [33] El 9 de enero de 1991, la Unión Soviética envió tropas; esto culminó con el ataque del 13 de enero al Edificio de Radio y Televisión Estatal y la Torre de Televisión de Vilna , que mató a 14 civiles. [34] La Unión Soviética reconoció la independencia de Lituania en septiembre de 1991. [35] Según la Constitución de Lituania , "la capital del Estado de Lituania será la ciudad de Vilna, la capital histórica de Lituania desde hace mucho tiempo".

Vilna se ha convertido en una ciudad europea moderna. Su territorio se ha ampliado con tres actos desde 1990, incorporando áreas urbanas, pueblos, aldeas y la ciudad de Grigiškės . [36] [37] La mayoría de los edificios históricos han sido renovados y una zona comercial y de negocios se convirtió en el Nuevo Centro de la Ciudad , el principal distrito administrativo y comercial en el lado norte del río Neris. El área incluye espacios residenciales y comerciales modernos, con el edificio municipal y la Torre Europa de 148,3 m (487 pies) como sus edificios más destacados. La construcción de la sede de Swedbank indica la importancia de los bancos escandinavos en Vilna. El complejo Vilnius Business Harbour fue construido y ampliado. Se construyeron más de 75.000 apartamentos entre 1995 y 2018, lo que convirtió a la ciudad en un líder de la construcción en el Báltico.

Vilna fue seleccionada como Capital Europea de la Cultura 2009 junto con Linz , la capital de Alta Austria . [38] [39] La crisis financiera de 2007-2008 provocó una caída del turismo, lo que impidió la finalización de muchos proyectos; se hicieron acusaciones de corrupción e incompetencia; [40] [41] los aumentos de impuestos para la actividad cultural llevaron a protestas, [42] y las condiciones económicas provocaron disturbios. [43] El 28 y 29 de noviembre de 2013, Vilna fue sede de la cumbre de la Asociación Oriental en el Palacio de los Grandes Duques de Lituania . Participaron muchos presidentes, primeros ministros y funcionarios de alto rango europeos. [44] En 2015, Remigijus Šimašius se convirtió en el primer alcalde elegido directamente de la ciudad. [45] La cumbre de la OTAN de 2023 se celebró en Vilna. [46]

Vilna se encuentra en la confluencia de los ríos Vilnia y Neris en el sureste de Lituania. Varios países dicen que el punto medio geográfico de Europa está dentro de su territorio. El punto medio depende de la definición de extensión europea, y el Libro Guinness de los récords mundiales reconoce un punto cerca de Vilna como el centro continental. [47] Después de una reestimación de los límites europeos en 1989, Jean-George Affholder del Institut Géographique National (Instituto Geográfico Nacional Francés) determinó que su centro geográfico estaba en 54°54′N 25°19′E / 54.900, -25.317 (Purnuškės (centro de gravedad)) . [48] El método utilizado para calcular el punto fue el centro de gravedad de la figura geométrica europea , y se encuentra cerca del pueblo de Girija (a 26 kilómetros de Vilnius). En 2004 se construyó allí un monumento del escultor Gediminas Jokūbonis, una columna de granito blanco coronada por una corona de estrellas. [47]

Vilna se encuentra a 312 km (194 mi) del mar Báltico y de Klaipėda , el principal puerto marítimo de Lituania . Está conectada por carretera con otras ciudades importantes de Lituania, como Kaunas (a 102 km o 63 mi), Šiauliai (a 214 km o 133 mi) y Panevėžys (a 135 km o 84 mi).

Vilna tiene una superficie de 402 km2 . Los edificios cubren el 29,1 por ciento de la ciudad; los espacios verdes cubren el 68,8 por ciento y el agua cubre el 2,1 por ciento. [49] La ciudad tiene ocho reservas naturales : Reserva geomorfológica de las laderas de Vokės Senslėnio, Reserva geomorfológica de Aukštagiris, Reserva geomorfológica de Valakupių Klonio, Reserva hidrográfica de Veržuva, Reserva hidrográfica de Vokė, Reserva paisajística aguas arriba de Cedronas, Reserva paisajística de Tapeliai y Reserva geomorfológica de las laderas de Šeškinė. [50]

Vilna tiene un clima continental húmedo ( clasificación climática de Köppen Dfb ), [51] con registros de temperatura desde 1777. [52] La temperatura media anual es de 7,3 °C (45 °F); la temperatura media de enero es de -3,9 °C (25 °F), y la media de julio es de 18,7 °C (66 °F). La precipitación media anual es de 691 mm (27,20 in). Las temperaturas en la ciudad han aumentado significativamente durante los últimos 30 años, un cambio que el Servicio Hidrometeorológico de Lituania atribuye al calentamiento global inducido por el hombre . [53]

Los días de verano son cálidos y calurosos, especialmente en julio y agosto, con temperaturas diurnas superiores a los 30 °C (86 °F) durante las olas de calor periódicas. Los bares, restaurantes y cafés al aire libre son muy concurridos durante el día.

Los inviernos pueden ser muy fríos, aunque ocasionalmente se dan temperaturas superiores a 0 °C (32 °F). Se registran temperaturas inferiores a -25 °C (-13 °F) cada dos años. Los ríos de Vilna se congelan en inviernos particularmente fríos, y los lagos que rodean la ciudad casi siempre están congelados de diciembre a marzo, e incluso en abril, en los años más extremos. El Servicio Hidrometeorológico de Lituania, con sede en Vilna, monitorea el clima del país. [54]

.jpg/440px-Tombstone_for_Leonas_Sapiega01(js).jpg)

Vilna fue un centro artístico del Gran Ducado de Lituania, que atraía a artistas de toda Europa. Las obras de arte góticas tempranas más antiguas que sobreviven (siglo XIV) son pinturas dedicadas a iglesias y liturgias , como frescos en las criptas de la Catedral de Vilna y himnarios decorados . Las pinturas murales del siglo XVI se encuentran en la Iglesia de San Francisco y San Bernardo y en la Iglesia de San Nicolás de la ciudad . [60] Esculturas policromadas de madera gótica decoran los altares de las iglesias. Algunos sellos góticos de los siglos XIV y XV todavía existen, incluidos los de Kęstutis , Vitautas el Grande y Segismundo II Augusto . [61]

La escultura renacentista apareció a principios del siglo XVI, principalmente por los escultores italianos Bernardinus Zanobi da Gianotti, Giovani Cini y Giovanni Maria Padovano. Durante el Renacimiento, las lápidas con retratos y las medallas eran valoradas; ejemplos de ello son las tumbas de mármol de Albertas Goštautas (1548) y Paweł Holszański (1555) de Bernardino de Gianotis en la Catedral de Vilna. La escultura italiana se caracteriza por su tratamiento naturalista de las formas y proporciones precisas. Los escultores locales adoptaron el esquema iconográfico de las tumbas renacentistas; sus obras, como la tumba de Lew Sapieha ( c. 1633 ) en la Iglesia de San Miguel , son estilizadas. [61] Durante este período, los pintores locales y de Europa occidental crearon composiciones religiosas y mitológicas y retratos con características del gótico tardío y el barroco; han sobrevivido libros de oraciones ilustrados, ilustraciones y miniaturas. [60]

Durante el Barroco de finales del siglo XVI , se desarrolló la pintura mural. La mayoría de los palacios e iglesias estaban decorados con frescos con colores brillantes, ángulos sofisticados y dramatismo. La pintura secular (retratos figurativos, imaginativos, epitafios, escenas de batallas y eventos políticamente importantes en un estilo detallado y realista) también se difundió en esta época. [60] Las esculturas barrocas dominaron la arquitectura sacra : lápidas con retratos esculpidos y esculturas decorativas en madera, mármol y estuco . Escultores italianos como GP Perti, GM Galli y AS Capone, figuras clave en el desarrollo de la escultura en el gran ducado del siglo XVII, fueron comisionados por la nobleza lituana . Sus obras ejemplifican el barroco maduro, con formas expresivas y sensualidad. Los escultores locales enfatizaron los rasgos decorativos barrocos, con menos expresión y emoción. [61]

La pintura lituana estuvo influenciada por la Escuela de Arte de Vilna durante finales del siglo XVIII y XIX, que introdujo el arte clásico y romántico . Los pintores hicieron prácticas en el extranjero, principalmente en Italia. Comenzaron las composiciones alegóricas, mitológicas, paisajes y retratos de representantes de varios círculos de la sociedad, y prevalecieron los temas históricos. Los pintores clásicos más conocidos de la época son Franciszek Smaglewicz, Jan Rustem , Józef Oleszkiew, Daniel Kondratowicz , Józef Peszka y Wincenty Smokowski . Los artistas románticos fueron Jan Rustem, Jan Krzysztof Damel , Wincenty Dmochowski y Kanuty Rusiecki . [60] Después del cierre de la Universidad de Vilna en 1832, la Escuela de Arte de Vilna continuó influyendo en el arte lituano. [62]

La Sociedad de Arte Lituana fue fundada en 1907 por Petras Rimša , Antanas Žmuidzinavičius y Antanas Jaroševičius , y la Sociedad de Arte de Vilna fue fundada al año siguiente. [63] [64] Entre los artistas se encontraban Jonas Šileika, Justinas Vienožinskis , Jonas Mackevičius (1872) , Vytautas Kairiūkštis y Vytautas Pranas Bičiūnas , que emplearon el simbolismo , el realismo , el Art Nouveau y el modernismo de Europa occidental . [60] El realismo socialista se introdujo después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial , con pinturas de propaganda , obras históricas y domésticas, naturalezas muertas , paisajes, retratos y esculturas. [60] [61] Los pintores de finales del siglo XX y XXI son Žygimantas Augustinas, Eglė Ridikaitė, Eglė Gineitytė, Patricija Jurkšaitytė, Jurga Barilaitė y Solomonas Teitelbaumas. [60]

El barrio de Užupis , cerca del casco antiguo, un barrio degradado durante la era soviética, alberga artistas bohemios que gestionan numerosas galerías de arte y talleres. [65] En su plaza principal, una estatua de un ángel tocando una trompeta simboliza la libertad artística.

En 1995 se instaló en el distrito de Naujamiestis el primer monumento de bronce del mundo dedicado a Frank Zappa [66] . En 2015 se puso en marcha el proyecto Vilnius Talking Statues, en el que dieciocho estatuas repartidas por la ciudad interactúan con los visitantes a través de teléfonos inteligentes en varios idiomas. [67]

Vilna tiene una variedad de museos. [68] El Museo Nacional de Lituania , en el Palacio de los Grandes Duques de Lituania, la Torre de Gediminas y los arsenales del Complejo del Castillo de Vilna, tiene exhibiciones sobre la historia de Lituania y la cultura lituana. [69] [70] [71] El Museo de Artes Aplicadas y Diseño exhibe arte popular y religioso lituano, objetos del Palacio de los Grandes Duques de Lituania y ropa de los siglos XVIII al XX. [72] Otros museos son el Museo de Vilna, la Casa de Historias, el Museo del Patrimonio de la Iglesia, el Museo de Ocupaciones y Luchas por la Libertad , el Museo de la Lucha por la Libertad en la Torre de Televisión de Vilna , la Casa MK Čiurlionis, el Museo Samuel Bak, el Centro de Educación Civil, el Museo del Juguete, Vilnius (Museo de Ilusiones), el Museo de Energía y Tecnología, la Casa de los Signatarios, el Centro de Tolerancia, el Museo del Ferrocarril, el Museo del Dinero, la Casa-Museo Kazys Varnelis, el Museo del Molino de Agua de la Mansión Liubavas, el Museo de Vladislovas Sirokomlė, el Museo-Galería del Ámbar y el centro de información para visitantes Paneriai Memorial. [68] [73]

Vilna tiene varias galerías de arte. La colección de arte más grande de Lituania se encuentra en el Museo Nacional de Arte de Lituania . [74] La Galería de Imágenes de Vilna, en el casco antiguo de la ciudad, alberga una colección de arte lituano desde el siglo XVI hasta principios del siglo XX. [75] Al otro lado del Neris, la Galería Nacional de Arte tiene varias exposiciones de arte lituano del siglo XX. [76] El Centro de Arte Contemporáneo , el recinto de arte contemporáneo más grande de los Estados bálticos, tiene un espacio de exposición de 2.400 metros cuadrados (26.000 pies cuadrados). El centro desarrolla exposiciones internacionales y lituanas y presenta una variedad de programas públicos que incluyen conferencias, seminarios, actuaciones, proyecciones de películas y videos y música en vivo. [77] El 10 de noviembre de 2007, el cineasta de vanguardia Jonas Mekas inauguró el Centro de Artes Visuales Jonas Mekas ; Su exposición de estreno fue La vanguardia: del futurismo a Fluxus . [78] En 2018, el Museo MO abrió sus puertas como una iniciativa de los científicos y filántropos lituanos Danguolė y Viktoras Butkus. Su colección de 5000 piezas modernas incluye importantes obras de arte lituanas desde la década de 1950 hasta la actualidad. [79]

Alrededor de 1520, Francysk Skaryna (autor de la primera Biblia rutena ) estableció la primera imprenta de Europa del Este en Vilna. Skaryna preparó y publicó el Pequeño libro del viajero (en ruteno: Малая подорожная книжка ), el primer libro impreso del Gran Ducado de Lituania, en 1522. Tres años más tarde, imprimió los Hechos y las Epístolas de los Apóstoles (el Apóstol ). [80]

La Imprenta de la Academia de Vilna fue fundada en 1575 por el noble lituano Mikołaj Krzysztof "el Huérfano" Radziwiłł como imprenta de la Academia de Vilna , delegando su gestión a los jesuitas . Publicó su primer libro, Pro Sacratissima Eucharistia contra haeresim Zwinglianam de Piotr Skarga , en mayo de 1576. La imprenta fue financiada por la nobleza lituana y la iglesia. [81] En 1805, Józef Zawadzki compró la imprenta y fundó la imprenta Józef Zawadzki . En funcionamiento continuo hasta 1939, publicó libros en varios idiomas; [82] El primer libro de poesía de Adam Mickiewicz se publicó en 1822. [83]

Mikalojus Daukša tradujo y publicó un catecismo del teólogo jesuita español Jacobo Ledesma en 1595, el primer libro impreso en lengua lituana en el Gran Ducado de Lituania. También tradujo y publicó la Postilla Catholica de Jakub Wujek en 1599. [84]

Muchos escritores nacieron en Vilnius, vivieron allí o son alumnos de la Universidad de Vilnius; Entre ellos se encuentran Konstantinas Sirvydas , Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski , Antoni Gorecki , Józef Ignacy Kraszewski , Antoni Edward Odyniec , Michał Józef Römer , Adam Mickiewicz, Władysław Syrokomla , Józef Mackiewicz , Romain Gary , Juliusz Słowacki , Simonas Daukantas , Mykolas Bir. žiška , Petras Cvirka , Kazys Bradūnas , premio Nobel Czesław Miłosz ). [85] Las exalumnas de la Academia de Artes de Vilna también se han sumado a los escritores contemporáneos aclamados internacionalmente como Jurga Ivanauskaitė , Undinė Radzevičiūtė y Kristina Sabaliauskaitė . La primera consideración del Primer Estatuto de Lituania tuvo lugar en 1522 en el Seimas del Gran Ducado de Lituania. El código fue redactado bajo la dirección del Gran Canciller de Lituania Albertas Goštautas de acuerdo con el derecho consuetudinario , la legislación y el derecho canónico y romano . Es la primera codificación de la ley secular de Europa . [86] Albertas Goštautas apoyó el uso del lituano en la literatura. y protegió a autores lituanos (incluidos Abraomas Kulvietis y Miguel el Lituano ) que criticaron el uso del antiguo eslavo eclesiástico y llamaron a los refugiados viejos creyentes en De moribus tartarorum, lituanorum et moscorum . [87]

Desde el siglo XVI, la Métrica lituana se conserva en el Castillo Inferior y está bajo la custodia del Canciller del Estado . Debido al deterioro de los libros, el Gran Canciller Lew Sapieha ordenó que se volvieran a copiar en 1594; la copia continuó hasta 1607. Los libros copiados fueron inventariados, revisados y trasladados a un edificio separado en Vilna; los libros más antiguos permanecieron en el Castillo de Vilna. Según datos de 1983, 665 libros permanecen en microfilm en el Archivo Histórico Estatal de Lituania en Vilna. [88]

Más de 200 azulejos y placas conmemorativas de escritores que vivieron y trabajaron en Vilna y autores extranjeros relacionados con Vilna y Lituania adornan las paredes de la calle Literatų (en lituano: Literatų gatvė ) en el casco antiguo, destacando la historia de la literatura lituana. [89] El Instituto de Literatura y Folklore de Lituania y la Unión de Escritores de Lituania se encuentran en la ciudad. [90] [91] La feria del libro de Vilna se celebra anualmente en LITEXPO , el centro de exposiciones más grande del Báltico. [92]

.jpg/440px-Billboard_of_the_first_cinema_screening_in_Vilnius_(1897).jpg)

La primera sesión de cine público en Vilna se celebró en el Jardín Botánico (actualmente Jardín Bernardinai ) en julio de 1896. Se celebró después de las sesiones de cine de 1895 de Auguste y Louis Lumière en París. La sesión en Vilna mostró las películas documentales de los hermanos Lumière . Las primeras películas mostradas fueron educativas, filmadas fuera de Vilna (en la India y África) y presentaban otras culturas. La película de Georges Méliès , Viaje a la Luna , se mostró por primera vez en el cine de la plaza Lukiškės en 1902; fue el primer largometraje mostrado en Vilna. [93]

El primer cine de Vilna, Iliuzija (Ilusión), abrió sus puertas en 1905 en la calle Didžioji 60. [ 94 ] Los primeros cines, similares a los teatros, tenían palcos con asientos más caros. Como las primeras películas eran mudas, las proyecciones se acompañaban de actuaciones orquestales. Las proyecciones de cine a veces se combinaban con representaciones teatrales y espectáculos de ilusionismo. [93]

El 4 de junio de 1924, el magistrado de Vilna estableció un cine de 1200 asientos en el ayuntamiento ( en polaco : Miejski kinematograf , Cine de la ciudad) para proporcionar educación cultural a estudiantes y adultos. En 1926, se vendieron 502.261 entradas; 24.242 entradas se entregaron a niños internados, 778 a turistas y 8.385 a soldados. En 1939, las autoridades lituanas lo rebautizaron como Milda. El último gobierno de la ciudad se lo entregó al Comisariado del Pueblo de Educación, que estableció la Sociedad Filarmónica Nacional Lituana al año siguiente. [94]

En 1965 se inauguró en Vilna el cine más moderno de Lituania (Lietuva); recibía más de 1,84 millones de visitantes al año y obtenía unos beneficios anuales de más de un millón de rublos . Tras su reconstrucción, contaba con una de las pantallas más grandes de Europa: 200 metros cuadrados (2200 pies cuadrados). [94] Cerrado en 2002, fue demolido en 2017 y sustituido por el Museo MO. [95] Kino Pavasaris es el festival de cine más grande de la ciudad. [96] El Centro de Cine de Lituania ( en lituano : Lietuvos kino centras ), encargado de promover el desarrollo y la competitividad de la industria cinematográfica lituana, se encuentra en Vilna. [97]

.jpg/440px-Libretto_of_the_first_opera_staged_in_Vilnius_(1636).jpg)

Los músicos actuaban en el palacio de los grandes duques de Lituania ya en el siglo XIV, ya que la hija del gran duque Gediminas, Aldona de Lituania, era conocida por su entusiasmo por la música. Aldona trajo músicos y cantantes de la corte a Cracovia después de casarse con el rey Casimiro III el Grande . [99] Durante el siglo XVI, compositores como Wacław de Szamotuły , Jan Brant, Heinrich Finck , Cyprian Bazylik , Alessandro Pesenti, Luca Marenzio y Michelagnolo Galilei vivieron en Vilna; la ciudad también fue el hogar del virtuoso laudista Bálint Bakfark . Uno de los primeros músicos locales en fuentes escritas fue Steponas Vilnietis (Stephanus de Vylna). El primer libro de texto de música lituana, El arte y la práctica de la música ( en latín : Ars et praxis musica ), fue publicado en Vilna por Žygimantas Liauksminas en 1667. [100]

Los artistas italianos produjeron la primera ópera de Lituania el 4 de septiembre de 1636 en el Palacio de los Grandes Duques, por encargo del Gran Duque Władysław IV Vasa . [101] Las óperas se producen en el Teatro Nacional de Ópera y Ballet de Lituania y en la Ópera de la Ciudad de Vilna . [102]

La Sociedad Filarmónica Nacional de Lituania, la organización de conciertos estatal más grande y antigua del país, produce conciertos en vivo y giras en Lituania y en el extranjero. [103] La Orquesta Sinfónica Estatal de Lituania , fundada por Gintaras Rinkevičius , actúa en Vilna. [104]

La música coral es popular en Lituania, y Vilnius tiene tres coros laureados (Brevis, Jauna Muzika y el Coro de Cámara del Conservatorio) en el Gran Premio Europeo de Canto Coral . [105] El Festival de Canto y Danza de Lituania en Vilnius se ha presentado cada cuatro años desde 1990 para unos 30.000 cantantes y bailarines folclóricos en el Parque Vingis . [106] En 2008, el festival y sus homólogos letones y estonios fueron designados como Obra Maestra del Patrimonio Oral e Inmaterial de la Humanidad de la UNESCO . [107]

La escena del jazz está muy activa en Vilna; en 1970-71, el trío Ganelin/Tarasov/Chekasin fundó la Escuela de Jazz de Vilna. [108] El Festival de Jazz de Vilna se celebra anualmente.

El Gatvės muzikos diena (Día de la Música Callejera) anual reúne a músicos en las calles de la ciudad. [109] Vilna es el lugar de nacimiento de los cantantes Mariana Korvelytė – Moravskienė, Paulina Rivoli , Danielius Dolskis , Vytautas Kernagis , Algirdas Kaušpėdas , Andrius Mamontovas , Nomeda Kazlaus y Asmik Grigorian ); los compositores César Cui , Felix Yaniewicz , Maximilian Steinberg , Vytautas Miškinis y Onutė Narbutaitė ); la directora Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla ) y los músicos Antoni Radziwiłł , Jascha Heifetz , Clara Rockmore y Romas Lileikis ).

Fue la ciudad natal de los compositores del siglo XVIII Michał Kazimierz Ogiński , Johann David Holland (colega de C. Bach ), Maciej Radziwiłł y Michał Kleofas Ogiński . La Vilna del siglo XIX era conocida por la cantante Kristina Gerhardi Frank, amiga íntima de Mozart y Haydn (que protagonizó el estreno de La Creación de Haydn ), el virtuoso de la guitarra de mediados del siglo XIX Marek Konrad Sokołowski y el compositor Stanisław Moniuszko . La mujer más rica de Vilna a principios del siglo XIX fue la cantante Maria de Neri. A principios del siglo XX, Vilna fue la ciudad natal de Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis , Mikas Petrauskas y Juozas Tallat-Kelpša . Entre los músicos de finales del siglo XX y principios del XXI se encuentran Vyacheslav Ganelin , Petras Vyšniauskas , Petras Geniušas , Mūza Rubackytė , Alanas Chošnau y Marijonas Mikutavičius .

La Academia Lituana de Música y Teatro , con sede en la Avenida Gediminas , también se encuentra en el Palacio Slushko en Antakalnis . Entre los cantantes que han impartido conferencias en la academia se incluyen los tenores Kipras Petrauskas y Virgilijus Noreika . [110]

Los espectáculos de los grandes duques lituanos en el castillo, las visitas de los soberanos al extranjero y las reuniones con los invitados tenían elementos teatrales. Durante la estancia de Segismundo III Vasa en Vilna a principios del siglo XVII, los actores ingleses actuaban en el palacio. Władysław IV Vasa fundó un teatro de ópera profesional en el Castillo Inferior en 1635, donde se representaban dramas per musica del italiano Virgilio Puccitelli. Las representaciones tenían una escenografía básica y lujosa. [111]

Entre los siglos XVI y XVIII existió un teatro escolar jesuita, cuya primera representación ( Hércules de S. Tucci) se produjo en 1570 en Vilna. En el teatro prevalecía la estética barroca, que también tenía retrospectivas medievales , elementos renacentistas, motivos rococó y una función educativa. Las representaciones se hacían en latín, pero se incluían elementos de la lengua lituana y algunas de las obras tenían temas lituanos ( obras dedicadas a Algirdas , Mindaugas, Vytautas y otros gobernantes lituanos). [112] [113]

En 1785, Wojciech Bogusławski fundó el Teatro Municipal de Vilna, el primer teatro público de la ciudad. El teatro, que inicialmente estaba en el Palacio Oskierka, se trasladó al Palacio Radziwiłł y al Ayuntamiento de Vilna . Las obras se representaban en polaco hasta 1845, de 1845 a 1864 en polaco y ruso, y después de 1864 en ruso. Tras el levantamiento de la prohibición del idioma lituano, las obras también se representaban en lituano. El teatro cerró en 1914. [114]

Durante el período de entreguerras (cuando la ciudad era parte de Polonia), Vilna era conocida por la compañía y el instituto experimentales Reduta, dirigidos por Juliusz Osterwa . [115] La Compañía Teatral Amateur Lituana de Vilna (en lituano: Vilniaus lietuvių scenos mėgėjų kuopa ), fundada en 1930 y rebautizada como Teatro Lituano de Vilna, actuaba en la región. En 1945, se fusionó con el Teatro Dramático Nacional de Lituania . [113]

Tras la ocupación soviética de Lituania en 1940, el teatro se convirtió en un medio de difusión de la ideología soviética. Las representaciones incorporaron el realismo socialista y se representaron numerosas obras revolucionarias de autores rusos. Se creó una Comisión de Repertorio dependiente del Ministerio de Cultura para dirigir los teatros, controlar el repertorio y permitir (o prohibir) las representaciones. [113]

El teatro cambió después de la independencia de Lituania. [113] La Ópera de la Ciudad de Vilna, de carácter independiente, combina el arte clásico y el contemporáneo. El Teatro Dramático Nacional de Lituania, el Pequeño Teatro Estatal de Vilna, el Teatro Juvenil Estatal y varias compañías teatrales privadas (entre ellas, el Teatro de la Ciudad de Vilna/OKT y el Teatro de Danza Anželika Cholina) presentan obras clásicas, modernas y lituanas dirigidas por destacados directores lituanos y extranjeros. También hay un Teatro Antiguo de Vilna en idioma ruso . [116]

Según las memorias del arquitecto Bolesław Podczaszyński, publicadas en enero de 1853 en la Gazeta Warszawska , la fotografía lituana comenzó con el daguerrotipo realizado en el verano de 1839 del reconstruido Palacio Verkiai por François Marcillac (gobernador de los hijos del duque Ludwig Wittgenstein ). [117] La desfavorable situación política del país obstaculizó el desarrollo de nuevas tecnologías y actividades culturales. El primer taller de daguerrotipos y retratos conocido en Vilna fue inaugurado en 1843 por C. Ziegler, y los talleres funcionaron en Lituania hasta 1859. Uno de los fotógrafos más conocidos fue K. Neupert, de Noruega . [117]

En la década de 1860, con la difusión del proceso de colodión , se utilizaron negativos de vidrio y papel de albúmina en lugar de placas de daguerrotipo. Los retratos fotográficos en formatos estándar se generalizaron y se establecieron talleres de fotografía comercial en Vilna y otras ciudades lituanas. Las primeras fotografías de paisajes y arquitectura fueron realizadas por los fotógrafos de Vilna Abdonas Korzonas y Albert Swieykowski, quienes recopilaron el Álbum de Vilna de 32 imágenes (el primer conjunto de fotografías de Lituania). En 1862, se aprobaron las Regulaciones Provisionales de Censura que regulaban las actividades de las instituciones fotográficas, supervisadas por la Junta Central de Prensa del Ministerio del Interior. Aquellos que fotografiaron a los rebeldes en el Levantamiento de Enero fueron castigados; A. Korzonas fue deportado a Siberia . Otros fotógrafos destacados del siglo XIX fueron Stanisław Filibert Fleury (un pionero de la fotografía estereoscópica ), [118] Aleksander Władysław Strauss y Józef Czechowicz. [117]

El segundo fotoheliógrafo del mundo se instaló en 1865 en el Observatorio Astronómico de la Universidad de Vilna y fotografió las manchas solares . [117] Un sistema sin precedentes de fotografía de la dinámica solar comenzó en 1868 en Vilna. [119] Jan Bułhak fundó el primer club de fotografía del país en Vilna en 1927. [120] En 1952, la revista Švyturys organizó la primera exposición de fotografía de la ciudad. [117]

En la actual Lituania se han producido herramientas de hierro, armas, joyas de latón , vidrio y plata desde el siglo I. [122] La cerámica , los productos de madera y el tejido se generalizaron en los siglos II y IV. Durante la era feudal , las artesanías domésticas eran componentes de una economía de subsistencia . Durante los siglos XIII y XIV, las artesanías se convirtieron en una rama de la economía separada de la agricultura. Los grandes duques de Lituania promovieron el desarrollo de la artesanía en las ciudades, y predominaron el tejido, la fabricación de calzado, la confección de pieles y otras artesanías. Con la introducción de artesanos extranjeros a principios del siglo XIV, el desarrollo de la artesanía se aceleró; la artesanía y el comercio estimularon el crecimiento de Vilna y otras ciudades lituanas. En los siglos XIV y XV, las artesanías se especializaron (especialmente la producción de herramientas, artículos para el hogar, telas, ropa, armas y joyas); se establecieron talleres que capacitaban y defendían los intereses de los artesanos. La producción de cristalería fina comenzó, se desarrolló la orfebrería y el nivel de la cerámica y el tejido aumentó durante el siglo XVI, y los Estatutos de Lituania de 1529 y 1588 identifican 25 artesanías. [122] Los orfebres europeos trabajaban en el Taller de Orfebrería de Vilna (establecido en 1495), que controlaba el comercio de metales preciosos y piedras preciosas y servía a las regiones de Daugava y Dnieper , la Iglesia Católica , el Gran Duque, la nobleza y la gente de la ciudad. [123] La Casa de la Moneda de Vilna , la principal casa de la moneda del Gran Ducado de Lituania, acuñó el denario lituano , chelines , groschen , táleros , ducados y otras monedas desde 1387 hasta 1666. [124]

La artesanía decayó en la segunda mitad del siglo XVII debido a la guerra ruso-polaca , y la mayoría de los bienes eran importados y vendidos por nobles lituanos y polacos. Resurgió entre la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII y la primera mitad del siglo XIX, siendo Vilna el mayor centro artesanal de Lituania. Después de la abolición de la servidumbre , se establecieron escuelas de artesanía en las ciudades lituanas; la artesanía ha prevalecido en la fabricación de ropa , la orfebrería, la carpintería, el procesamiento de alimentos y otros campos. Bajo la ocupación soviética, los artesanos trabajaron en artels hasta 1960 y luego en cosechadoras . Después de la independencia, la artesanía fue producida por pequeñas y medianas empresas. [122]

Vilna, una ciudad multicultural , fue cambiando su lengua a lo largo de los siglos. La lengua hablada predominante en la Lituania medieval era el lituano. Sin embargo, no tenía tradición literaria y no se utilizaba por escrito, salvo en textos religiosos como el Padrenuestro y el Ave María . [125] [87] Vitautas el Grande hablaba en lituano con Jogaila , cuyo hijo Casimiro IV Jagellón también hablaba lituano. [126] [127] [128] San Casimiro , el santo patrón de Lituania, sabía lituano, polaco, alemán y latín. [129] El historiador bizantino del siglo XV Laonikos Chalkokondyles informó que los lituanos tenían una lengua distinta. [130] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ]

El ruteno se utilizó después de la incorporación de la Rus de Kiev , formando la base del ucraniano y bielorruso del siglo XIX . El ruteno escrito surgió de la interacción del antiguo eslavo oriental con los dialectos rutenos, convirtiéndose en el idioma principal de la cancillería del Gran Ducado de Lituania en los siglos XIV y XV y mantuvo su predominio hasta mediados del siglo XVII. [125] [131]

El latín y el polaco también se utilizaban ampliamente en la cancillería; el polaco sustituyó al ruteno en las fuentes escritas y al lituano en el uso público durante la segunda mitad del siglo XVII. Los primeros documentos estatales en lituano aparecieron en el Gran Ducado de Lituania al final de su existencia. [125]

En la corte de Vilna de Segismundo II Augusto , el último Gran Duque de Lituania antes de la Unión de Lublin , se hablaban polaco y lituano. [133] En 1552, Segismundo ordenó que las órdenes del Magistrado de Vilna se anunciaran en lituano, polaco y ruteno. [134] Minorías como los judíos , los tártaros lipka y los caraítas de Crimea eran gobernadas por el Gran Duque de Lituania, y sus idiomas solo se usaban entre ellos. [135] Según el artículo 14 de la constitución lituana, el lituano es el idioma oficial ; sin embargo, a veces se proporciona asistencia de intérprete . [136]

Según el historiador Antanas Čaplinskas , las esposas de los comerciantes y artesanos llevaban anillos decorados con piedras preciosas. Los inventarios de propiedades de los siglos XVI y XVII enumeran chaquetas largas de mangas anchas (conocidas como kontusz ), żupans decorados con piel y cinturones de kontush . [137] Los botones , hechos de perla , coral , diamantes de talla brillante y esmeraldas , estaban decorados con diamantes y esmalte. [137] Las delias y los dólmanes eran populares entre los habitantes de las ciudades y los nobles. [138]

Los ciudadanos ricos que vestían ropas lujosas despertaron la envidia de la nobleza lituana, que exigió leyes que regularan la vestimenta. El Estatuto de Lituania de 1588 limitaba a los ciudadanos a dos anillos, y los judíos no podían llevar cadenas de oro ni broches . [137] El Sejm de la Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania impuso restricciones más amplias , al adoptar la Ley de Ahorro de 1613 que prohibía a los ciudadanos no nobles llevar pieles caras en público. [137] El pago de una tasa eliminó posteriormente las limitaciones. [137]

A finales del siglo XVIII, casi todos los hombres se afeitaban, llevaban el pelo corto y vestían fracs y chalecos abiertos de color azul, verde o negro con pantalones blancos o amarillo claro; [138] la ropa de las mujeres imitaba los estilos de Europa occidental. A principios del siglo XX, la ropa siguió las tendencias de la moda de Europa occidental. El Instituto Estatal de Arte de Lituania introdujo los estudios de diseño de ropa y en 1961 se fundó la Casa Modelo de Vilna (que popularizó la indumentaria y el calzado). [139]

El desfile de moda anual de primavera de Vilnius, Mados infekcija (Infección de moda), el más grande de Lituania , comenzó en 1999. [140] El diseñador de ropa lituano Juozas Statkevičius suele presentar sus desfiles en la ciudad. [141]

Las fiestas católicas como Navidad , Pascua y la víspera de San Juan se celebran ampliamente. [142] El 16 de febrero (aniversario del Acta de Independencia de Lituania) y el 11 de marzo (aniversario del Acta de Restablecimiento del Estado de Lituania ), tienen lugar eventos festivos y religiosos en Vilna. [143] [144] En la noche del 12 de enero, se encienden hogueras para conmemorar los Eventos de Enero. [145]

La Kaziuko mugė (Feria de San Casimiro), que se celebra anualmente en los mercados y calles de la ciudad el domingo más cercano al 4 de marzo (la festividad de San Casimiro ), atrae a muchos visitantes y artesanos lituanos y extranjeros. Las palmas de Pascua (en lituano: Verbos ) son un símbolo de la feria. [146] Los Días de la Capital (en lituano: Sostinės dienos ), el festival de música y cultura más grande de Vilna, se celebra del 30 de agosto al 1 de septiembre. [147] El río Vilna se tiñe de verde cada año para el Día de San Patricio . [148] Durante la Noche de la Cultura de Vilna , artistas y organizaciones culturales organizan eventos y actuaciones por toda la ciudad. [149]

Antes de que en 1378 se concedieran los derechos de Magdeburgo a Vilna, la ciudad estaba gobernada por vicerregentes . Más tarde, el gobierno pasó a manos de un magistrado o de un consejo municipal, subordinado al gobernante. En tiempos de guerra, lo dirigía un voivoda . [150] La sede del gobierno estaba en el Ayuntamiento de Vilna. [151]

El magistrado era responsable de la economía de la ciudad: recaudaba impuestos, supervisaba el tesoro y acumulaba reservas de grano para evitar la hambruna durante las hambrunas o las guerras. Era notario en transacciones y testamentos, juez en conflictos relacionados con la construcción y la renovación, y se ocupaba de los artesanos; los estatutos relacionados con los talleres eran aprobados por el gobernante, pero Segismundo II Augusto dio esta responsabilidad a los magistrados en 1552. Desde una sentencia de 1522 de Segismundo I el Viejo , los magistrados de Vilna tenían que proteger la ciudad y sus residentes con 24 guardias armados. Durante la guerra, la vigilancia nocturna estaba a cargo del magistrado, el obispo y los hombres del castillo. [150] [152]

El administrador principal de la ciudad era un vaitas católico (un vicegerente del Gran Duque de Lituania), [153] la mayoría de los cuales estaban comenzando sus carreras en la magistratura y presidían las reuniones del consejo de la ciudad. Él juzgaba casos criminales , con el derecho de imponer la pena capital. Originalmente examinaban casos solos, pero dos suolininkai también comenzaron a examinar casos importantes en el siglo XVI. En ese momento, el consejo de la ciudad estaba formado por 12 burgomaestres y 24 consejeros; la mitad eran católicos, la otra mitad ortodoxos ). Los miembros eran elegidos por ciudadanos ricos, comerciantes y ancianos de los talleres. Los burgomaestres eran nombramientos vitalicios; al morir, se elegía a otro miembro del consejo con la misma religión. En 1536, Segismundo I el Viejo firmó un edicto que prohibía a los parientes cercanos formar parte del consejo y exigía el acuerdo previo de los ciudadanos sobre nuevos impuestos, obligaciones y regulaciones. [150]

Bajo el Imperio ruso, el consejo municipal fue reemplazado por una duma municipal . [154] Vilna fue la capital de la Gobernación de Lituania de 1797 a 1801, la Gobernación General de Vilna de 1794 a 1912 y la Gobernación de Vilna de 1795 a 1915. [155] [156] Después de la ocupación soviética de Lituania , Vilna fue la capital de la República Socialista Soviética de Lituania . [154]

El Ayuntamiento de Vilna es el órgano representativo de autogobierno de uno de los 60 municipios de Lituania . Además de Vilna propiamente dicha, incluye la ciudad de Grigiškės , así como los pueblos y zonas rurales de la circunscripción de Grigiškės . [ cita requerida ]

El Consejo Municipal de la Ciudad de Vilna , establecido en 1990, [154] es elegido por períodos de cuatro años y los candidatos son nominados por partidos políticos y comités. [157] A partir de las elecciones de 2011, se permiten candidatos independientes. [158] Su órgano ejecutivo es la Administración Municipal de la Ciudad de Vilna .

Antes de 2015, los alcaldes eran designados por el consejo. [159] A partir de ese año, los alcaldes eran elegidos en un sistema de dos vueltas . [159] Remigijus Šimašius fue el primer alcalde elegido directamente de la ciudad. [160]

Los distritos municipales son una división administrativa estatal. Los 21 distritos municipales se basan en barrios:

Municipio del distrito de Vilna (lituano: Vilniaus rajono savivaldybė ), uno de los municipios más grandes del país, cubre 2.129 kilómetros cuadrados (822 millas cuadradas) y tiene 23 ancianos . Hay más de 1.000 pueblos y cinco ciudades ( Nemenčinė , Bezdonys , Maišiagala , Mickūnai y Šumskas ) en el distrito. Limita con Bielorrusia y los distritos de Švenčionys , Moletai , Širvintos , Elektrėnai , Trakai y Šalčininkai . [164]

El distrito tiene una población multinacional, de la cual el 52 por ciento son polacos , el 33 por ciento lituanos y el resto rusos , bielorrusos y otras nacionalidades (incluidos ucranianos ). Tiene una población de más de 100.000 habitantes; el 95 por ciento vive en aldeas y el cinco por ciento en ciudades. [164] El distrito de Vilna tiene el terreno más alto de Lituania, con las colinas Aukštojas , Juozapinė y Kruopinė a más de 290 metros (950 pies) sobre el nivel del mar . [164]

En el distrito se celebra el Domingo de Ramos y las palmas de Pascua de Vilna ( verbos ) se hacen con flores y hierbas secas. [165] La fabricación de palmas se remonta a la época de San Casimiro. [164]

El castillo de Medininkai , el molino de la mansión Liubavas y la mansión Bareikiškės son los monumentos históricos más conocidos del distrito. [164] De 1769 a 1795, el voivodato de Vilna rodeó a la República independiente de Paulava . El microestado , conocido por sus valores ilustrados , tenía su propio presidente, parlamento campesino , ejército y leyes. [166]

Con su gran población polaca, el Consejo Municipal del Distrito de Vilna está compuesto principalmente por miembros del partido Acción Electoral de los Polacos en Lituania . [167] Su alcalde es Robert Duchniewicz de la Unión Socialdemócrata Lituana . [168]

.jpg/440px-Baltijas_Asamblejas_31.sesija_Viļņā_(8169464170).jpg)

Vilna es la sede del gobierno nacional de Lituania . Los dos principales funcionarios del país tienen sus oficinas en Vilna. El presidente reside en el Palacio Presidencial en la Plaza Daukanto , [169] y la sede del primer ministro está en la oficina del Gobierno de Lituania en la Avenida Gediminas. [170] Según la ley, el presidente tiene una residencia en el distrito Turniškės de Vilna, cerca del Neris. [171] [172] El primer ministro también tiene derecho a una residencia en el distrito Turniškės durante su mandato. [173] Los ministerios del gobierno están ubicados por toda la ciudad, muchos en el casco antiguo. [174]

El Seimas del Gran Ducado de Lituania se reunía principalmente en Vilna. [175] El Seimas actual se reúne en el Palacio del Seimas en la Avenida Gediminas. [176]

Los tribunales superiores de Lituania se encuentran en Vilna. El Tribunal Supremo de Lituania (en lituano: Lietuvos Aukščiausiasis Teismas ), que revisa los casos penales y civiles, se encuentra en la calle Gynėjų. [177] El Tribunal Administrativo Supremo de Lituania (en lituano: Lietuvos vyriausiasis administracinis teismas ), que decide los litigios contra los organismos públicos, se encuentra en la calle Žygimantų. [178] El Tribunal Constitucional de Lituania (en lituano: Lietuvos Respublikos Konstitucinis Teismas ), un órgano consultivo con autoridad sobre la constitucionalidad de las leyes, se reúne en el Palacio del Tribunal Constitucional en la Avenida Gediminas. [179] El Tribunal Lituano , el tribunal de apelación más alto para la nobleza del Gran Ducado de Lituania y establecido por Stephen Báthory en 1581, estuvo en Vilna hasta la Tercera Partición de Polonia en 1795. [180]

La seguridad en Vilnius es principalmente responsabilidad de la Vilniaus apskrities vyriausiasis policijos komisariatas , la oficina de policía más alta de la ciudad, y de las oficinas de policía locales. Sus principales responsabilidades son garantizar el orden público y la seguridad, informar e investigar delitos penales y controlar el tráfico. [181] En 2016, la ciudad tenía 1.500 agentes de policía. [182] El Servicio de Seguridad Pública es responsable de la pronta restauración del orden público en situaciones especiales y de garantizar la protección de importantes objetos estatales y sujetos escoltados. [183]

El Cuerpo de Bomberos de Vilna (Vilniaus apskrities priešgaisrinė gelbėjimo valdyba) es el principal órgano de gobierno de los bomberos de Vilna . [184] Hubo 1.287 incendios en los primeros nueve meses de 2018, que mataron a seis personas e hirieron a 16. [185]

Vilniaus greitosios medicinos pagalbos stotis es responsable de los servicios médicos de emergencia en la ciudad, y el número de teléfono del EMS es 033. [186] Establecido en 1902, es una de las instituciones EMS más antiguas de Europa del Este. [187] Muchos médicos y otro personal recibieron medallas por su ayuda a las víctimas de los acontecimientos de enero de 1991. [187] El número común para contactar con los servicios de emergencia en Vilnius y otras partes de Lituania es 112. [188]

El casco antiguo cubre unos 3,6 km² ( 1,4 millas cuadradas), y su historia se remonta al Neolítico . Las colinas glaciares fueron ocupadas intermitentemente, y se construyó un castillo de madera en la confluencia de Neris y Vilnia alrededor del año 1000 d. C. para fortificar la colina de Gedimino . El asentamiento se convirtió en una ciudad en el siglo XIII, cuando los pueblos paganos del Báltico fueron invadidos por los europeos occidentales durante la Cruzada lituana . Alrededor de 1323 (las primeras fuentes escritas sobre Vilnia), era la capital del Gran Ducado de Lituania y tenía algunos edificios de ladrillo. En el siglo XV, el ducado se extendía desde el Báltico hasta el Mar Negro (principalmente las actuales Bielorrusia, Ucrania y Rusia). El centro histórico consta de tres castillos (Superior, Inferior y Curvo) y el área anteriormente rodeada por la Muralla de Vilna . Es principalmente circular, centrado en el sitio del castillo original. Las calles son pequeñas y estrechas, y más tarde se construyeron grandes plazas. [21] La calle Pilies , la arteria principal, une el Palacio de los Grandes Duques de Lituania con el Ayuntamiento de Vilna. Otras calles están bordeadas por los palacios de los señores feudales y terratenientes, iglesias, tiendas y talleres de artesanos.

Los edificios históricos presentan arquitectura gótica , [190] renacentista , [191] barroca [192] y clásica . [193] La variedad de iglesias conservadas y antiguos palacios de la nobleza lituana ejemplifica el patrimonio multicultural de Vilna. [21] [194]

Los lituanos y otros dieron forma al desarrollo de la capital, con influencias occidentales y orientales. Lituania fue cristianizada en 1387, pero la ortodoxia oriental y la creciente importancia del judaísmo llevaron a la construcción de la Catedral Ortodoxa de la Theotokos y la Gran Sinagoga de Vilna . [21]

Los desastres dieron lugar a reconstrucciones de edificios en estilo barroco de Vilna , que más tarde influyó en el Gran Ducado de Lituania. [21] [20] Artistas como Matteo Castelli y Pietro Perti ) del actual cantón de Ticino fueron los preferidos por el Gran Duque y la nobleza local, y diseñaron la Capilla de San Casimiro . [195] El lituano Laurynas Gucevičius fue un destacado arquitecto clásico en la ciudad. [196]

El casco antiguo de 352 hectáreas (870 acres) fue designado Patrimonio de la Humanidad por la UNESCO en 1994. El centro histórico de Vilna se caracteriza por mantener su trazado de calles medievales sin lagunas significativas. Algunos lugares fueron dañados durante las ocupaciones y guerras de Lituania, incluida la Plaza de la Catedral (demolida en 1795) y una plaza al este de la Iglesia de Todos los Santos donde se encontraba el Convento de los Carmelitas Descalzos con la Iglesia barroca de San José el Desposado del vicecanciller Stefan Pac (ambas demolidas por el zar) . La Gran Sinagoga y parte de los edificios de la calle Vokiečių fueron demolidos después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. [21]

Vilnius tiene una superficie de 401 kilómetros cuadrados, de los cuales una quinta parte está urbanizada y el resto son espacios verdes y agua. La ciudad es conocida como una de las capitales más "verdes" de Europa. [197]

En las criptas de la catedral de Vilna están enterrados notables católicos lituanos. El gran duque Alejandro Jagellón , la reina Isabel de Austria , Bárbara Radziwiłł y el corazón del gran duque Vladislao IV Vasa están enterrados en el mausoleo real. Estas criptas tienen uno de los frescos más antiguos del país, pintado a finales del siglo XIV o principios del XV después de que Lituania fuera cristianizada. [198]

El casco antiguo de Vilna (en lituano: Vilniaus senamiestis ), con calles medievales pavimentadas con piedra, y Užupis tienen viviendas prestigiosas, con apartamentos con vistas a iglesias icónicas y monumentos urbanos (en particular la Torre Gediminas ), patios interiores cerrados, techos altos, áticos, diseños no estándar e interiores lujosos; [199] Los pisos en estos barrios pueden costar millones de euros . [200] Sin embargo, los atascos, el estacionamiento caro, la contaminación del aire, los altos costos de mantenimiento y las limitaciones en la renovación también alientan a los vilnianos ricos a comprar o construir casas privadas en partes periféricas de la ciudad, como Balsiai, Bajorai , Pavilnys, Kalnėnai y Pilaitė o el cercano Municipio del Distrito de Vilna . [199] Alrededor de 21.000 residentes viven en el casco antiguo y 7.000 en Užupis. [201]

Valakampiai y Turniškės son barrios prestigiosos, con casas privadas en grandes terrenos rodeados de bosques de pinos a los que se puede acceder fácilmente desde el centro de la ciudad. Allí viven personas adineradas y jefes de estado (como el presidente), y la mayoría de las casas privadas más grandes cuestan millones de euros. [199] [202] Parte del barrio de Žvėrynas tiene lujosas casas privadas cerca del parque Vingis, pero también tiene edificios de apartamentos de la era soviética y casas de madera en mal estado. [201] [199]

Los barrios que rodean el casco antiguo (Antakalnis, Žirmūnai, Naujamiestis y Žvėrynas) tienen una variedad de apartamentos y espacios verdes, y son populares entre los residentes de clase media . Las personas más ricas viven en una construcción nueva o en apartamentos renovados de la era soviética. [199] El gobierno apoya la renovación y reembolsa el 30 por ciento o más del costo. [203] Sin embargo, los residentes más pobres y los jubilados de bajos ingresos fomentan el regionalismo . [204] [205]

Los barrios más alejados, como Lazdynai, Karoliniškės, Viršuliškės, Šeškinė , Justiniškės, Pašilaičiai, Fabijoniškės y Naujininkai , tienen viviendas más asequibles. Sus desventajas son un viaje más largo, edificios de gran altura de la era soviética sin renovar , congestión del tráfico y escasez de plazas de aparcamiento cerca de los apartamentos más antiguos. [199] [206]

.jpg/440px-Vilnia,_Śnipiški,_Jezuicki._Вільня,_Сьніпішкі,_Езуіцкі_(L._Bichebois,_1848-49).jpg)

La zona de Šnipiškės recibió importantes inversiones durante la década de 2010. La zona fue mencionada por primera vez en 1536, cuando el Gran Duque Segismundo I el Viejo ordenó a Ulrich Hosius construir un puente de madera sobre el río Neris y se desarrolló un suburbio alrededor del puente. Ese siglo, el magistrado de Vilna construyó un edificio para mensajeros moscovitas y tártaros al norte de Šnipiškės. [207] La iglesia jesuita de San Rafael Arcángel y el monasterio y las viviendas para los habitantes ricos y de clase media de la ciudad se construyeron en Šnipiškės durante el siglo XVIII. Los artesanos vivían en las afueras, donde se construyeron una fábrica de pipas, aserraderos y una pequeña fábrica de dulces. El barrio de Skansenas, de 8 hectáreas (20 acres), al oeste del mercado de Kalvarijų, [208] tiene casas de madera de finales del siglo XIX. Cerca de allí se construyó Piromontas [209] en la misma época.

Durante la década de 1960, Šnipiškės pasó a llamarse Nuevo Centro de la Ciudad . Tenía la primera zona peatonal de la ciudad y una serie de edificios, incluido el centro comercial más grande del país, un gran hotel, un planetario, un museo y varios ministerios de la República Socialista Soviética de Lituania, construidos antes de 1990. [210] [211] [212] [213] [214] Šnipiškės al norte de la avenida Konstitucijos estuvo subdesarrollado hasta principios de la década de 2000, cuando el nuevo edificio del municipio de la ciudad de Vilna impulsó la construcción de la Plaza Europa con un centro comercial, un edificio de oficinas de 33 pisos y un edificio de apartamentos de 27 pisos. El antiguo Museo de la Revolución se convirtió en la Galería Nacional de Arte a fines de la década de 2000. [215]

Según los economistas, el número de transacciones y el índice de asequibilidad de la vivienda alcanzaron máximos históricos en 2019 debido al aumento de los ingresos de los residentes de la ciudad y la desaceleración del aumento de los precios de los pisos. [216] Una cuarta parte de los residentes de entre 26 y 35 años todavía vive en casas propiedad de sus padres u otros familiares, sin embargo, el porcentaje más alto se da en los estados bálticos. [217]

En la antigua Vilkpėdė se encontraron restos de un asentamiento magdaleniense que datan de alrededor del año 10000 a. C. Kairėnai, Pūčkoriai y Naujoji Vilnia tuvieron grandes asentamientos durante el primer milenio d. C. [218] La zona más densamente poblada era la confluencia de los ríos Neris y Vilnia, que tenía granjas fortificadas. [218]

Según algunos historiadores, Vilna podría haber sido una ciudad durante la época del Reino de Lituania : el rey Mindaugas no vivió allí de forma permanente, sin embargo, es posible que haya construido allí la primera iglesia católica de Lituania para su coronación . Sin embargo, está bien establecido que Vilna existió como ciudad durante los tiempos de Traidenis y Vytenis . La primera mención en las fuentes históricas como capital es en 1323 en las cartas a las ciudades occidentales de Gediminas .

Se convirtió en una ciudad multicultural, con fuentes del siglo XIV que señalan que consistía en una Gran Ciudad (Lituana) y una Ciudad Rutena . En el siglo XVI, comerciantes alemanes , artesanos, judíos y tártaros también se habían establecido en Vilna. Durante la Reforma y la Contrarreforma de los siglos XVI y XVII , la población de habla polaca de la ciudad comenzó a crecer; a mediados del siglo XVII, la mayoría de los escritos estaban en polaco. [218] La ciudad también estaba habitada por un gran número de artesanos italianos y suizos y, en general, todas las naciones europeas estaban representadas en cierta medida (entre ellas, profesores y estudiantes universitarios de Vilna, entre los que había franceses , españoles , suecos e incluso algunos croatas como Tomaš Zdelarius, músicos del Palacio de los Grandes Duques de Lituania o servidores militares como el húngaro Gáspár Bekes ). Debido a que muchas naciones habitaban la ciudad, en los siglos XVI al XVIII fue conocida y apodada en fuentes occidentales como la Babilonia de Europa. [4]

Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el número de lituanos étnicos en Vilna se recuperó; sin embargo, la lituanización fue reemplazada por la sovietización . [219] [220] Después de la independencia en 1990, la población étnicamente lituana de Vilna aumentó al 63,2 por ciento en 2011 y al 67,44 por ciento en 2021. [221] [222] [223]

Evolución demográfica de Vilna entre 1766 y 2024:

Vilna es el centro económico de Lituania, con un PIB per cápita en el área metropolitana de casi 30 000 € . [233] El presupuesto de la ciudad alcanzó los 1000 millones de € en 2022. [234] En el primer trimestre de 2024, el salario mensual medio en Vilna fue de 2478,7 € (bruto) y 1513,5 € (neto). [235]

Lithuania's economic growth has been uneven, with GDP per capita at nearly 110 percent of the EU average in Vilnius but from 42 to 77 percent in other regions. The country's convergence is fuelled by two regions (Vilnius and Kaunas County) which produce 42 and 20 percent of the national GDP, respectively. From 2014 to 2016, the Vilnius region grew by 4.6 percent.[237]

The supply of new housing in Vilnius and its suburbs has reached post-recession highs, and the stock of unsold apartments in Lithuania's three largest cities has begun to increase since the beginning of 2017. Demand for housing is strong, fuelled by rising wages, benign financial conditions and positive expectations. In the first half of 2018, the number of monthly transactions was the highest since its 2007–2008 peak.[238] Most foreign direct investment and productive public investment in Lithuania is concentrated on Vilnius and Kaunas.[239] Vilnius Industrial Park, 18.5 kilometres from the city, is intended for commercial and industrial use.[240]

Vilnius resident Tito Livio Burattini published Misura universale in 1675, in which he first suggested the term metre as a unit of length.[241] The Vilnius University Astronomical Observatory, established in 1753 at the initiative of Thomas Zebrowski, was one of Europe's first observatories and the first in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[242] Marcin Odlanicki Poczobutt led the reconstruction of the observatory, designed by Marcin Knackfus, from 1770 to 1772. Poczobutt began his astronomical observations in 1773, recording them in the journal (French: Cahiers des observations), and created the constellation Taurus Poniatovii.[243] Jean-Emmanuel Gilibert established the Botanical Garden of Vilnius University in 1781 with over 2,000 plants, and provided the first herbariums, collections of stuffed animals and birds, fossil plants, animal remains, and a collection of minerals to Vilnius University.,[244] The observatory published the Russian Empire's first exact sciences journal, the Journal of Mathematical Sciences (Russian: Вестник математических наук), after the Third Partition of Poland.[119]

Sunrise Valley Science and Technology Park (Lithuanian: Saulėtekio slėnio mokslo ir technologijų parkas) is a non-profit organization which was founded in 2003. Over 20,000 students study in the Vilnius University and Vilnius Gediminas Technical University facilities in Sunrise Valley, and 5,000 scientists conduct research in its science centres.[245]

The Centre for Physical Sciences and Technology (Lithuanian: Fizinių ir technologijos mokslų centras, FTMC) is the country's largest scientific research institution, specialising in laser technology, optoelectronics, nuclear physics, organic chemistry, bio and nanotechnology, electrochemical materials science, and electronics. The centre was created in 2010 with the merger of the institutes of chemistry, physics and semiconductor physics in Vilnius and the Textile institute in Kaunas.[246] With 250 laboratories (24 open to the public), it can accommodate over 700 researchers and students.[247] The centre has a PhD program and hosts annual conferences of PhD students and young researchers.[248] FTMC is the founder and sole shareholder of the Science and Technology Park of Institute of Physics in Savanorių Avenue, which assists companies with research and development.[249]

Vilnius University's Laser Research Centre (Lithuanian: Vilniaus universiteto Lazerinių tyrimų centras) is one of five departments in the university's Faculty of Physics, which prepares physicists, laser physicists and laser-technology specialists. The department conducts research in laser physics, nonlinear optics, optical-component characterization, biophotonics and laser microtechnology.[250] Lithuania has over 50 percent of the world's market share in ultrashort pulses lasers produced by Vilnius-based companies.[251] A laser system was produced in 2019 for the Extreme Light Infrastructure laboratory in Szeged which produces high-intensity, ultra-short pulses with a peak power up to 1,000 times that of the most powerful nuclear power plant in the United States.[251] Corning Inc. bought a glass-cutting licence from the Vilnius-based laser company Altechna and for manufacturing Gorilla Glass.[252]

The Vilnius University Life Sciences Centre (Lithuanian: Vilniaus universiteto Gyvybės mokslų centras) is a scientific research centre which consists of three institutes: the Institute of Biochemistry, Institute of Biosciences, and Institute of Biotechnology. The centre was opened in 2016 and has 800 students, 120 PhD students, 200 teaching staff, and open-access scientific laboratories with advanced equipment.[253] It has a technology business incubator for small and medium businesses in the life sciences or related fields.[254] Vilnius Gediminas Technical University has three research centres at Sunrise Valley: the Civil Engineering Research Centre, Technology Centre for Building Information and Digital Modelling, and Competence Centre of Intermodal Transport and Logistics.[255]

The Lithuanian Centre for Social Sciences (Lithuanian: Lietuvos socialinių mokslų centras), which cooperates with the Lithuanian government, produces and disseminates scientific information in the fields of economics, sociology and law to implement public policy.[256] Santara Valley (Lithuanian: Santaros slėnis) is a science and research facility which focuses on medicine, biopharmaceutical and bioinformatics.[257] The Vilnius University Faculty of Medicine Science Centre was scheduled for completion in Santara Valley in 2021.[258]

Vilnius University rector Jonas Kubilius, known for probabilistic number theory, the Kubilius model, the Theorem of Kubilius and Turán–Kubilius inequality, successfully resisted attempts to Russify Vilnius University.[259] Vilnius' Marija Gimbutas was the first to formulate the Kurgan hypothesis. In 1963, Vytautas Straižys and his colleagues created the Vilnius photometric system used in astronomy.[260] Kavli Prize laureate Virginijus Šikšnys invented CRISPR-Cas9 genetic editing.[261]

Vilnius is attractive for foreign companies because of its qualified employees and good infrastructure.[262] Several schools are preparing skilled specialists, including the Vilnius University Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics and Vilnius Gediminas Technical University Faculty of Fundamental Sciences.[263][264] Information technology jobs are well-paid.[265] The 2018 output of the Lituanian IT sector was €2.296 billion, much of which was created in Vilnius.[266]

Vilnius Tech Park in Sapieha Park, the largest IT startup hub in the Baltic and Nordic countries, unites international startups, technology companies, accelerators, and incubators.[267] fDi Intelligence ranked Vilnius number one city on its 2019 Tech Start-up FDI Attraction Index.[268]

Vilnius had the world's fastest internet speed in 2011[269] and, despite its fall in the rankings, remains one of the world's fastest.[270] Vilnius Airport has one of Europe's fastest airport Wi-Fi speeds.[271] The National Cyber Security Centre of Lithuania was established in Vilnius to address internet attacks on Lithuanian government organizations.[272]

Bebras, an international informatics and IT contest, has been held annually for pupils in grades three through 12 since 2004.[273] Since 2017, computer programming is taught in primary schools.[274]

Vilnius is a popular fintech hub due to Lithuania's flexible e-money licence regulations.[275] The Bank of Lithuania granted an e-money licence in 2018 to Vilnius-based Google Payment Lithuania.[276] The startup Revolut also has an e-money licence and headquarters in Vilnius, and began moving its clients to the Lithuanian company Revolut Payments in 2019.[277] On 23 January 2019, Europe's first international blockchain centre opened in Vilnius.[278]

Vilnius is Lithuania's financial centre. The Ministry of Finance in Vilnius is responsible for an effective public financial policy to ensure the country's economic growth.[279] The Bank of Lithuania fosters a reliable financial system and ensures sustainable economic growth.[280] The Nasdaq Vilnius stock exchange is in The K29 business centre.[281]

The National Audit Office of Lithuania (Lithuanian: Lietuvos Respublikos valstybės kontrolė) helps the government manage public funds and property,[282] and the State Tax Inspectorate (Lithuanian: Valstybinė mokesčių inspekcija) is responsible for collecting and refunding taxes.[283]

In 2023, 13 banks held a bank or specialised-bank licence; six banks are foreign-bank branches. Most of the Lithuanian financial system consists of capital banks of Nordic countries.[284] The two largest banks registered in Lithuania (SEB bankas and Swedbank) are supervised by the European Central Bank and the Bank of Lithuania.[285]

Primary and lower secondary education is mandatory in Lithuania. Children begin pre-primary education at age six, education is compulsory until age 16. Primary and secondary education is free, but there are also private schools in Vilnius. The country's educational system is governed by the Ministry of Education, Science and Sports, headquartered in Vilnius.[286]

Cathedral School of Vilnius, first mentioned in a 1397 source, is the earliest known Lithuanian school.[218] Vilnius Vytautas the Great Gymnasium, established in 1915, is the first Lithuanian gymnasium in eastern Lithuania.[287] In 2018, the city had 120 schools (not including preschools) with 61,123 pupils and 4,955 teachers.[288] Four out of five best rated schools in Lithuania are in Vilnius, and the Vilnius Lyceum is number one.[289]

Ethnic minorities in Lithuania have their own schools. Vilnius has seven elementary schools, eight primary schools, two progymnasiums and 12 gymnasiums for minority children, with lessons in minority languages. In 2017, 4,658 Poles and 9,274 Russians studied in their languages in the city.[290] Vilnius has 11 vocational schools.[291]

The National M. K. Čiurlionis School of Art is the country's only 12-year art school. The Vilnius Justinas Vienožinskis Art School is another art school in Vilnius.

Most school graduates in Vilnius later study at universities or colleges. According to the OECD, 57.5 percent of 25– to 34-year-olds in Lithuania had a tertiary education in 2021.[292]Vilnius has nine international schools, including the International School of Vilnius, Vilnius International French Lyceum, British International School of Vilnius, and American International School of Vilnius.[293]

On 14 October 1773, the Commission of National Education (Lithuanian: Edukacinė komisija) was created by the Sejm of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Grand Duke Stanisław August Poniatowski, who supervised schools and Vilnius University in the Commonwealth. Because of its authority and autonomy, it is considered Europe's first ministry of education and an example of the Enlightenment in the Commonwealth.[294]

Vilnius has a number of universities, the largest and oldest of which is Vilnius University.[295] With its main campus in the Old Town, it has been ranked among the top 500 universities in the world by QS World University Rankings.[296] The university participates in projects with UNESCO and NATO. It has master's programs in English and Russian,[297] and programs in cooperation with other universities throughout Europe. The university has 14 faculties.[295]

Other universities include Mykolas Romeris University,[298] Vilnius Gediminas Technical University[299] and the Lithuanian University of Educational Sciences, which merged with Vytautas Magnus University in 2018.[300] Specialized tertiary schools with university status include the General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania, the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre, and the Vilnius Academy of Arts. The museum associated with the Vilnius Academy of Arts contains about 12,000 artworks.[301]

The Vilnius city municipality central library (Lithuanian: Vilniaus miesto savivaldybės centrinė biblioteka) operates public libraries in the city.[303] It has 16 branches, one (Saulutė) dedicated to children's literature.[304] Many libraries offer free computer literacy courses.[305] The public libraries require a free LIBIS (integrated information system of Lithuanian libraries) card.[306]

The Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania (Lithuanian: Lietuvos nacionalinė Martyno Mažvydo biblioteka) in Gediminas Avenue, founded in 1919, collects, organizes and preserves Lithuania's written cultural heritage, collects Lithuanian and foreign documents relevant to research and Lithuania's educational and cultural needs, and provides library services to the public.[307] By 1 July 2019, its electronic catalog had 1,140,708 bibliographic records.[308]

The Wroblewski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences (Lithuanian: Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka) is open to all.[309] The library had 3,733,514 volumes by 1 January 2015, and 12,274 registered users.[309]

Every Lithuanian university and college has a library for students, professors and alumni. The National Open Access Scientific Communication and Information Center of Vilnius University (Lithuanian: Vilniaus universiteto bibliotekos Mokslinės komunikacijos ir informacijos centras) in Saulėtekis Valley opened in 2013 and has over 800 workplaces in an area of 14,043.61 m2 (151,164.2 sq ft).[310][311] Central Vilnius University Library,[312] Vilnius Gediminas Technical University Library, Mykolas Romeris University Library, ISM University of Management and Economics Library, European Humanities University Library, and Kazimieras Simonavičius University Library are on their respective campuses in Vilnius.[313]

By the 17th century, Vilnius was known as a city of numerous religions. In 1600, Samuel Lewkenor's book about cities with universities was published in London;[315] According to Lewkenor, Vilnius' population included Catholics, Orthodox, followers of John Calvin and Martin Luther, Jews and Tartar Muslims.[page needed]

During that century, Vilnius had a reputation as a city unrivaled in Europe for its number and variety of churches. Robert Morden wrote in Geography Rectified or a Description of the World that no other city in the world could surpass Vilnius in the number of churches and temples except, perhaps, Amsterdam.[316][317]

Vilnius is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vilnius, housing major church institutions and the archdiocesan Vilnius Cathedral. A number of Christian beatified people, martyrs, servants of God and saints are associated with the city. They include the Franciscan martyrs of Vilnius, the Orthodox martyrs Anthony, John, and Eustathius, Saint Casimir, Josaphat Kuntsevych, Andrew Bobola, Raphael Kalinowski, Faustina Kowalska, and Jurgis Matulaitis-Matulevičius. There are a number of Roman Catholic churches in the city, small monasteries, and religious schools. Church architecture includes Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque and neoclassical styles, with examples of each in the Old Town. Eastern Rite Catholicism has also had a presence in Vilnius since the Union of Brest. The Baroque Basilian Gate is part of an Eastern Rite monastery.

.jpg/440px-Russian_Orthodox_Church_of_The_Holy_Mother_of_God_Vilnius_(5990381200).jpg)

Vilnius has had an Eastern Orthodox presence since the 12th century, and the Russian Orthodox Monastery of the Holy Spirit is near the [Gate of Dawn. St. Paraskeva's Orthodox Church in the Old Town was the site of the 1705 baptism of Hannibal, the great-grandfather of Alexander Pushkin, by Tsar Peter the Great. Many Old Believers, who split from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1667, settled in Lithuania; a Supreme Council of Old Believers is based in Vilnius. The Orthodox Church of St. Constantine and St. Michael was built in 1913. A number of Protestant and other Christian denominations[319] are represented in Vilnius, notably Lutheran Evangelicals and Baptists.

Lithuania's pre-Christian religion, centred on the forces of nature and personified by deities such as Perkūnas (the thunder god), is experiencing increased interest. Romuva established a Vilnius branch in 1991.[320]

Known as "Yerushalayim D'Lita" (the Jerusalem of Lithuania), Vilnius had been a world centre for Torah study and had a large Jewish population since the 18th century. A major scholar of Judaism and the Kabbalah was Rabbi Eliyahu Kremer, known as the Vilna Gaon, whose writings significantly influence Orthodox Jews. The Vilna Shas, the most widely used version of the Talmud, was published in the city in 1886.[321] Jewish life in Vilnius was destroyed during the Holocaust, and a memorial stone dedicated to victims of Nazi genocide is in the centre of the former Jewish Ghetto on present-day Mėsinių Street. The Vilna Gaon Museum of Jewish History is dedicated to the history of Lithuanian Jewish life. The site of Vilnius's largest synagogue, built in the early 1630s and destroyed by Nazi Germany during its occupation of Lithuania, was found by ground-penetrating radar in June 2015.[322] Archaeologists began excavating the site in 2016, and that work continues as of July 2024.[323]

The Karaites are a Jewish sect who migrated to Lithuania from the Crimea. Small in numbers, they have become more prominent since Lithuanian independence and have restored their kenesas (including the Vilnius Kenesa).[324]

It is safe to say that I have been in Vilnius all my life, at least since I became conscious. I was in Vilnius with thoughts and heart – one could say [my] whole being. And so it stayed – and in Rome.

— Pope John Paul II at the Dominican Church of the Holy Spirit during his 1993 visit to Lithuania[325]

Since the 1387 Christianization of Lithuania, Vilnius has become a centre of Christianity in the country and a pilgrimage site. The Vilnius Pilgrimage Centre (Lithuanian: Vilniaus piligrimų centras) coordinates pilgrimages, assists with their preparation, and performs pilgrimage pastoral care.[326] A number of places in Vilnius are associated with miracles or mark events significant to Christians, and the Chapel of the Gate of Dawn is visited by thousands of Christian pilgrims annually. The gates were initially part of the defensive Wall of Vilnius; they were given to the Carmelites in the 16th century, who installed a chapel in the gates with a 17th-century Catholic painting: Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn. The painting was later decorated with gold-plated silver and is associated with miracles and a legend.[327]

The Sanctuary of the Divine Mercy is a pilgrimage site which has a Divine Mercy image. Vilnius was the birthplace of the Divine Mercy devotion when Saint Faustina Kowalska began her mission under the guidance of Michał Sopoćko, her spiritual director. The first Divine Mercy image was painted in 1934 by Eugeniusz Kazimirowski under the supervision of Kowalska, and it hangs in the Divine Mercy Sanctuary in Vilnius. Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament takes place in the shrine around the clock.[327] The House of St. Faustina, in Antakalnis' V. Grybo Street, is open to pilgrims.[328]