World Wrestling Entertainment ( WWE ) es una promoción de lucha libre profesional estadounidense . Es propiedad y está operada por TKO Group Holdings , una subsidiaria de propiedad mayoritaria de Endeavor Group Holdings . [10] WWE, una empresa global integrada de medios y entretenimiento, también se ha diversificado en campos fuera de la lucha libre, incluido el cine , el fútbol y varias otras empresas comerciales. La empresa también está involucrada en la concesión de licencias de su propiedad intelectual a empresas para producir videojuegos y figuras de acción .

La promoción fue fundada en 1953 como Capitol Wrestling Corporation (CWC), un territorio del noreste de la National Wrestling Alliance (NWA). Después de una disputa, CWC dejó la NWA y se convirtió en la World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF) en abril de 1963. Después de reincorporarse a la NWA en 1971, la WWWF pasó a llamarse World Wrestling Federation (WWF) en 1979 antes de que la promoción abandonara la NWA definitivamente en 1983. En 2002, tras una disputa legal con el World Wildlife Fund , la WWF pasó a llamarse World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE). En 2011, la promoción dejó de llamarse World Wrestling Entertainment y comenzó a llamarse únicamente con las iniciales WWE . [11]

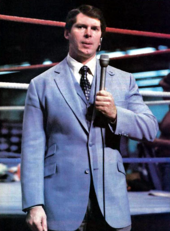

Antes de septiembre de 2023, el propietario mayoritario de la empresa era su presidente ejecutivo, el promotor de lucha libre de tercera generación Vince McMahon , quien conservaba una propiedad del 38,6% de las acciones en circulación de la empresa y el 81,1% del poder de voto. La entidad actual, que originalmente se llamaba Titan Sports, Inc. , se constituyó el 21 de febrero de 1980 en South Yarmouth, Massachusetts , pero se reincorporó bajo la Ley General de Corporaciones de Delaware en 1987. Adquirió Capitol Wrestling Corporation Ltd., la sociedad de cartera de la WWF, en 1982. Titan pasó a llamarse World Wrestling Federation Entertainment, Inc. en 1999, y luego World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc. en 2002. En 2023, su nombre legal se cambió a World Wrestling Entertainment, LLC . [12]

WWE es la promoción de lucha libre más grande del mundo. Su roster principal se divide en dos marcas de gira , Raw y SmackDown . Su marca de desarrollo , NXT , tiene su sede en el WWE Performance Center en Orlando, Florida . En general, la programación de la WWE está disponible en más de mil millones de hogares en todo el mundo en 30 idiomas. La sede mundial de la empresa se encuentra en Stamford, Connecticut , [13] con oficinas en Nueva York, Los Ángeles, Ciudad de México, Mumbai, Shanghái, Singapur, Dubái y Múnich. [14]

Al igual que en otras promociones de lucha libre profesional, los espectáculos de la WWE no son verdaderas competencias, sino espectáculos teatrales basados en el entretenimiento, con combates guiados por una historia , guionados y parcialmente coreografiados; sin embargo, los combates a menudo incluyen movimientos que pueden poner a los artistas en riesgo de lesiones, incluso la muerte, si no se realizan correctamente. El aspecto predeterminado de la lucha libre profesional fue reconocido públicamente por el entonces propietario de la WWE, Vince McMahon, en 1989 para evitar impuestos de las comisiones deportivas. La WWE comercializa su producto como entretenimiento deportivo , reconociendo las raíces de la lucha libre profesional en el deporte competitivo y el teatro dramático.

En 2023, WWE comenzó a explorar una posible venta de la empresa, en medio de un escándalo de mala conducta de los empleados que involucraba a McMahon que lo había llevado a renunciar como presidente y director ejecutivo, aunque regresó como presidente ejecutivo. [15] En abril de 2023, WWE hizo un trato con Endeavor Group Holdings, según el cual se fusionaría con Zuffa , la empresa matriz de la promoción de artes marciales mixtas Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) para formar TKO Group Holdings, una nueva empresa pública de propiedad mayoritaria de Endeavor, con McMahon como presidente ejecutivo de la nueva entidad y Nick Khan como presidente. La fusión se completó el 12 de septiembre de 2023. [16] En 2024, McMahon, que para entonces ya no era el accionista mayoritario de la WWE, terminó sus vínculos con la empresa en medio de un escándalo de tráfico sexual . [17]

Los orígenes de la WWE se remontan a la década de 1950, cuando el 7 de enero de 1953 se produjo el primer espectáculo bajo la Capitol Wrestling Corporation (CWC). Existe incertidumbre sobre quién fue el fundador de la CWC. Algunas fuentes afirman que fue Vincent J. McMahon , [18] [19] [20] mientras que otras fuentes citan al padre de McMahon, Jess McMahon, como fundador de la CWC. [21] [22] [23] La CWC más tarde se unió a la National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) y el famoso promotor neoyorquino Toots Mondt pronto se unió a la promoción.

Vincent J. McMahon y Toots Mondt tuvieron mucho éxito y pronto controlaron aproximadamente el 70% del poder de contratación de la NWA, en gran parte debido a su dominio en el densamente poblado noreste de los Estados Unidos . En 1963, McMahon y Mondt tuvieron una disputa con la NWA porque "Nature Boy" Buddy Rogers fue contratado para sostener el Campeonato Mundial Peso Pesado de la NWA . [24] Mondt y McMahon no solo eran promotores, sino que también actuaban como su manager y fueron acusados por otros promotores de la NWA de retener a Rogers haciendo defensas en sus ciudades en lugar de defender solo en las propias ciudades de Mondt y McMahon, manteniendo así un monopolio sobre el título mundial. En una situación ahora infame, la NWA envió al ex cinco veces campeón mundial y luchador legítimo Lou Thesz a Toronto para enfrentar a Rogers el 24 de enero de 1963. Thesz recuerda que esto no fue planeado y antes del combate recordó haberle dicho a Buddy "podemos hacer esto de la manera fácil o de la manera difícil". Rogers aceptó perder la caída y el título en un combate de una caída contra el tradicional enfrentamiento de dos de tres caídas que se defendía en la mayoría de los combates por el título mundial. Una vez que la noticia llegó a Mondt y McMahon, al principio simplemente ignoraron el cambio de título. Desde enero hasta abril de 1963, Rogers fue promovido como el Campeón Mundial de la NWA, o simplemente el Campeón Mundial de Peso Pesado, en su área. La World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF) no fue una creación inmediata después de la derrota de una caída de Rogers ante Thesz. Mondt y McMahon finalmente dejaron la NWA en protesta y formaron la WWWF en el proceso. Trajeron con ellos a Willie Gilzenberg , promotor de boxeo y lucha libre de larga data en Nueva Jersey. En abril de 1963, se creó el Campeonato Mundial de Peso Pesado de la WWWF , con la promoción afirmando que el campeón inaugural Rogers había ganado un torneo en Río de Janeiro el 25 de abril de 1963, derrotando al favorito de Capitol durante mucho tiempo Antonino Rocca en la final. En realidad, Rocca ya no estaba en la zona, ya que estaba trabajando para Jim Crockett Sr. en las Carolinas. Rogers también había sufrido lo que más tarde sería un ataque cardíaco que pondría fin a su carrera el 18 de abril en Akron, Ohio, y estaba en un hospital de Ohio durante el tiempo en que se llevó a cabo el supuesto torneo. [25] Rogers perdió el campeonato ante Bruno Sammartino un mes después, el 17 de mayo, y la promoción comenzó a construirse en torno a Sammartino poco después. [26]

En junio de 1963, Gilzenberg fue nombrado el primer presidente de la WWWF. [27] Mondt dejó la promoción a fines de la década de 1960 y, aunque la WWWF se había retirado previamente de la NWA, McMahon se reincorporó silenciosamente en 1971. La WWWF pasó a llamarse World Wrestling Federation (WWF) en 1979.

El hijo de Vincent J. McMahon, Vincent K. McMahon , y su esposa Linda , establecieron Titan Sports, Inc., en 1980 en South Yarmouth, Massachusetts y solicitaron marcas comerciales para las iniciales "WWF". [28] [29] La empresa se constituyó el 21 de febrero de 1980, en las oficinas del Cape Cod Coliseum , luego se trasladó al edificio en Holly Hill Lane en Greenwich, Connecticut .

El joven McMahon compró Capitol a su padre en 1982, tomando efectivamente el control de la compañía. La fecha real de la venta aún se desconoce, pero la fecha generalmente aceptada es el 6 de junio de 1982; sin embargo, es probable que esta fuera solo la fecha en la que se cerró el trato, pero no se concretó. En la televisión de la WWF, Capitol Wrestling Corporation mantuvo los derechos de autor y la propiedad más allá de la fecha de junio de 1982. La World Wrestling Federation no era propiedad exclusiva de Vincent J. McMahon, sino también de Gorilla Monsoon , Arnold Skaaland y Phil Zacko. El acuerdo entre los dos McMahon era una base de pago mensual, en la que si se omitía un solo pago, la propiedad volvería al mayor de los McMahon y sus socios comerciales. En un intento por cerrar el trato rápidamente, McMahon tomó varios préstamos y acuerdos con otros promotores y socios comerciales (incluida la promesa de un trabajo de por vida) para tomar la propiedad total en mayo o junio de 1983 por un total estimado de aproximadamente $1 millón con los tres socios comerciales recibiendo aproximadamente $815,000 entre ellos y Vincent J. McMahon recibiendo aproximadamente $185,000. [30] Buscando hacer de la WWF la principal promoción de lucha libre en el país, y eventualmente, en el mundo, comenzó un proceso de expansión que cambió fundamentalmente el negocio de la lucha libre. [31]

En la reunión anual de la NWA en 1983, los McMahon y el ex empleado de Capitol Jim Barnett se retiraron de la organización. [24] McMahon también trabajó para conseguir que la programación de la WWF se transmitiera por televisión sindicada en todo Estados Unidos. Esto enfureció a otros promotores y alteró los límites bien establecidos de las diferentes promociones de lucha libre, terminando finalmente con el sistema de territorios, que estaba en uso desde la fundación de la NWA en la década de 1940. Además, la empresa utilizó los ingresos generados por la publicidad, los acuerdos de televisión y las ventas de cintas para asegurar el talento de los promotores rivales. En una entrevista con Sports Illustrated , McMahon dijo: "En los viejos tiempos, había feudos de lucha libre en todo el país, cada uno con su propio pequeño señor a cargo. Cada pequeño señor respetaba los derechos de su vecino. No se permitían adquisiciones ni redadas. Había tal vez 30 de estos pequeños reinos en los EE. UU. y si no hubiera comprado a mi padre, todavía habría 30 de ellos, fragmentados y en dificultades. Yo, por supuesto, no tenía ninguna lealtad hacia esos pequeños señores". [31]

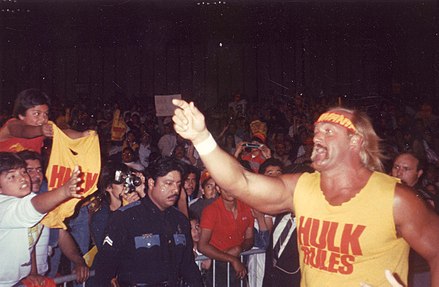

McMahon ganó tracción significativa cuando contrató al talento de la American Wrestling Association (AWA) Hulk Hogan , quien había alcanzado popularidad fuera de la lucha libre, en particular por su aparición en la película Rocky III . [32] McMahon contrató a Roddy Piper como rival de Hogan, y poco después a Jesse Ventura como locutor. Otros luchadores se unieron a la lista, como The Iron Sheik , Nikolai Volkoff , Junkyard Dog , Paul Orndorff , Greg Valentine y Ricky Steamboat , uniéndose a estrellas existentes como Jimmy Snuka , Don Muraco , Sgt. Slaughter y André the Giant . Muchos de los luchadores que luego se unirían a la WWF eran ex talentos de la AWA o NWA.

La WWF realizaría una gira nacional en una empresa que requeriría una gran inversión de capital, una que puso a la WWF al borde del colapso financiero. El futuro del experimento de McMahon dependía del éxito o el fracaso del concepto innovador de McMahon, WrestleMania . WrestleMania fue un gran éxito y fue (y todavía es) comercializado como el Super Bowl de la lucha libre profesional. El concepto de una supercartelera de lucha libre no era nada nuevo en América del Norte; la NWA había comenzado a realizar Starrcade unos años antes. Sin embargo, a los ojos de McMahon, lo que separaba a WrestleMania de otras supercarteleras era que estaba destinada a ser accesible para aquellos que no veían lucha libre. Invitó a celebridades como Mr. T , Muhammad Ali y Cyndi Lauper a participar en el evento, además de asegurar un acuerdo con MTV para brindar cobertura. El evento y la publicidad que lo rodeó llevaron al término Rock 'n' Wrestling Connection , debido a la promoción cruzada de la cultura popular y la lucha libre profesional.

El negocio de la WWF se expandió significativamente sobre los hombros de McMahon y su héroe babyface Hulk Hogan durante los siguientes años después de derrotar a The Iron Sheik en el Madison Square Garden el 23 de enero de 1984. [33] La introducción del Saturday Night's Main Event en NBC en 1985 marcó la primera vez que la lucha libre profesional se transmitió en la televisión en red desde la década de 1950, cuando la ahora extinta DuMont Television Network transmitió combates de Capitol Wrestling Corporation de Vincent J. McMahon. El "Wrestling Boom" de la década de 1980 alcanzó su punto máximo con el PPV WrestleMania III en el Pontiac Silverdome en 1987, que estableció un récord de asistencia de 93,173 para la WWF durante 29 años hasta 2016 . [34] Una revancha del evento principal de WrestleMania III entre el campeón de la WWF Hulk Hogan y André the Giant tuvo lugar en The Main Event I en 1988 y fue vista por 33 millones de personas, el combate de lucha libre más visto en la historia de la televisión norteamericana. [35]

En 1983, Titan trasladó sus oficinas a Stamford, Connecticut . Posteriormente, en 1987 se estableció una nueva Titan Sports, Inc. (originalmente WWF, Inc.) en Delaware y se consolidó con la entidad de Massachusetts en febrero de 1988. [36]

.jpg/440px-Shawn_Michaels_-_Birmingham_200997_(28).jpg)

La WWF fue golpeada con acusaciones de abuso y distribución de esteroides en 1992. Esto fue seguido por acusaciones de acoso sexual por parte de empleados de la WWF el año siguiente. [38] [39] McMahon finalmente fue exonerado, pero las acusaciones trajeron malas relaciones públicas para la WWF y una mala reputación en general. El juicio por esteroides le costó a la compañía aproximadamente $ 5 millones en un momento de ingresos récord bajos. Esto ayudó a llevar a muchos luchadores de la WWF a la promoción rival World Championship Wrestling (WCW), incluido el héroe babyface de la década de 1980 Hulk Hogan. Durante este período, la WWF promovió a luchadores de una edad más joven que comprendían "La Nueva Generación", con Bret Hart , Shawn Michaels , Diesel , Razor Ramon y The Undertaker , entre otros, en un esfuerzo por promover nuevos talentos al centro de atención.

En enero de 1993, la WWF estrenó su programa insignia de cable Monday Night Raw . WCW respondió en septiembre de 1995 con su propio programa de los lunes por la noche, Monday Nitro , que se emitió en el mismo horario que Raw . [40] Los dos programas intercambiarían victorias en la competencia de ratings resultante (conocida como la " Monday Night War ") hasta mediados de 1996. En ese momento, Nitro comenzó una dominación de los ratings de casi dos años que fue impulsada en gran medida por la introducción del Nuevo Orden Mundial (nWo), un grupo liderado por los ex luchadores de la WWF Hulk Hogan, Scott Hall (el ex Razor Ramon) y Kevin Nash (el ex Diesel). [41]

A medida que la Guerra de los Lunes por la Noche continuaba entre Raw Is War y Nitro de la WCW , la WWF se transformaría de un producto familiar a un producto más orientado a los adultos, conocido como la Era de la Actitud . La era fue encabezada por el vicepresidente de la WWF, Shane McMahon (hijo del propietario Vince McMahon) y el escritor principal, Vince Russo .

1997 terminó con McMahon enfrentando una controversia en la vida real luego de la controvertida salida de Bret Hart de la compañía, conocida como Montreal Screwjob . [43] Esto resultó ser uno de varios factores fundadores en el lanzamiento de la Era de la Actitud, así como en la creación del personaje en pantalla de McMahon, " Mr. McMahon ".

Antes del Montreal Screwjob, que tuvo lugar en Survivor Series de 1997 , la WWF contrató a ex talentos de la WCW, incluidos Stone Cold Steve Austin , Mankind y Vader . Austin fue incorporado lentamente como la nueva cara de la empresa a pesar de ser promocionado como un antihéroe , comenzando con su discurso " Austin 3:16 " poco después de derrotar a Jake Roberts en las finales del torneo de pago por visión King of the Ring en 1996. [44]

El 29 de abril de 1999, la WWF hizo su regreso a la televisión terrestre , transmitiendo un programa especial conocido como SmackDown! en la incipiente cadena UPN . El programa de los jueves por la noche se convirtió en una serie semanal el 26 de agosto de 1999, compitiendo directamente con el programa de los jueves por la noche de la WCW titulado Thunder en TBS .

En el verano de 1999, Titan Sports, Inc. pasó a llamarse World Wrestling Federation Entertainment, Inc. El 19 de octubre de 1999, World Wrestling Federation Entertainment, Inc. lanzó una oferta pública inicial como empresa que cotiza en bolsa, cotizando en la Bolsa de Valores de Nueva York (NYSE) con la emisión de acciones valoradas en ese momento en 172,5 millones de dólares. [45] La empresa cotiza en la NYSE bajo el símbolo WWE. [46]

En el otoño de 1999, la Attitude Era había cambiado el rumbo de la Monday Night War a favor de la WWF. Después de que Time Warner se fusionara con America Online (AOL), el control de Ted Turner sobre la WCW se redujo considerablemente. La compañía recién fusionada carecía de interés en la lucha libre profesional en su conjunto y decidió vender la WCW en su totalidad. Aunque Eric Bischoff , a quien Time Warner despidió como presidente de la WCW en octubre de 1999, estaba cerca de llegar a un acuerdo para comprar la compañía, en marzo de 2001 McMahon adquirió los derechos de las marcas registradas, la biblioteca de cintas, los contratos y otras propiedades de la WCW de AOL Time Warner por una cifra que se informó que rondaba los 7 millones de dólares. [47] Poco después de WrestleMania X-Seven , la WWF lanzó la historia Invasion, integrando la lista de talentos entrantes de la WCW y la Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW). Con esta compra, la WWF se convirtió ahora, con mucho, en la única promoción de lucha libre más grande de América del Norte y del mundo. Los activos de ECW, que habían quebrado después de declararse en quiebra en abril de 2001, fueron adquiridos por WWE en 2003. [48]

En 2000, la WWF, en colaboración con la cadena de televisión NBC , lanzó la XFL , una nueva liga de fútbol profesional que debutó en 2001. [49] La liga tuvo altos índices de audiencia durante las primeras semanas, pero el interés inicial disminuyó y sus índices de audiencia cayeron a niveles lamentablemente bajos (uno de sus juegos fue el programa de máxima audiencia con menor audiencia en la historia de la televisión estadounidense). NBC abandonó la empresa después de solo una temporada, pero McMahon tenía la intención de continuar solo. Sin embargo, después de no poder llegar a un acuerdo con UPN, McMahon cerró la XFL. [50] WWE mantuvo el control de la marca registrada XFL [51] [52] antes de que McMahon recuperara la marca XFL, esta vez bajo una empresa fantasma separada de WWE, en 2017 [53] con la intención de relanzar la XFL en 2020. [ 54]

El 24 de junio de 2002, en un episodio de Raw , Vince McMahon se refirió oficialmente al inicio de la siguiente era, llamada la era "Ruthless Aggression". [55] [56]

El 6 de mayo de 2002, la World Wrestling Federation (WWF) cambió tanto el nombre de su empresa como el nombre de su promoción de lucha libre a World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) después de que la empresa perdiera una demanda iniciada por el World Wildlife Fund sobre la marca registrada WWF. [57] [58] Aunque esto se debió principalmente a un fallo desfavorable en su disputa con el World Wildlife Fund con respecto a las siglas "WWF", la empresa señaló que esto le brindó la oportunidad de enfatizar su enfoque en el entretenimiento. [59]

En marzo de 2002, la WWE decidió crear dos listas separadas, con cada grupo de luchadores apareciendo en uno de sus programas principales, Raw y SmackDown!, debido a la sobreabundancia de talento que quedó de la historia de Invasion y la consiguiente absorción de los contratos de WCW y ECW. Esto se denominó como la " extensión de la marca ".

A partir de 2002, se llevó a cabo un sorteo casi todos los años para establecer las listas, con el primer borrador para determinar las listas divididas inaugurales y los borradores posteriores diseñados para actualizar las listas de cada programa. WWE expandió la división de marcas al relanzar ECW como una tercera marca el 26 de mayo de 2006. [60] Dos años después, WWE adaptó un formato más familiar y su programación recibió una clasificación TV-PG . [61] El programa final de ECW se emitió el 16 de febrero de 2010, después de lo cual fue reemplazado por NXT . [62] Durante este tiempo, muchos luchadores nuevos y jóvenes se unirían a la empresa, muchos de los cuales se convertirían en nombres familiares para los próximos años, como John Cena , Randy Orton , Brock Lesnar y Batista .

El 7 de abril de 2011, WWE, a través del sitio web corporativo de WWE, la empresa dejó de usar el nombre completo World Wrestling Entertainment y en adelante se refirió a sí misma únicamente como WWE, haciendo de este último un acrónimo huérfano . Se dijo que esto reflejaba la expansión global del entretenimiento de la WWE fuera del ring con el objetivo final de adquirir empresas de entretenimiento y centrarse en la televisión, los eventos en vivo y la producción cinematográfica. WWE señaló que su nuevo modelo de empresa se puso en marcha con el relanzamiento de Tough Enough , al ser un programa sin guion (contrariamente a la naturaleza con guion de la lucha libre profesional) y con el lanzamiento de WWE Network (en ese momento programado para lanzarse en 2012; luego se retrasó hasta 2014). Sin embargo, el nombre legal de la empresa sigue siendo World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc. [11]

A partir del episodio del 29 de agosto de 2011, Raw , conocido como Raw Supershow , presentó talentos tanto de Raw como de SmackDown (el epíteto "Supershow" se eliminaría el 23 de julio de 2012). [63] Los campeonatos que anteriormente eran exclusivos de un programa u otro estaban disponibles para que los luchadores de cualquier programa compitieran por ellos; el formato "Supershow" marcaría el final de la división de marcas, ya que toda la programación y los eventos en vivo (hasta julio de 2016) presentaban el roster completo de la WWE. [64]

En 2013, la empresa construyó el centro de entrenamiento y medicina deportiva WWE Performance Center en el este del condado de Orange, Florida, en asociación con la Full Sail University de Winter Park, Florida . El centro de entrenamiento está destinado al desarrollo profesional y atlético de los luchadores de la empresa. [65] Full Sail también es la base de operaciones de la marca NXT de la WWE , [66] que sirvió como territorio de desarrollo para la WWE. [67]

El 24 de febrero de 2014, WWE lanzó WWE Network , un servicio de transmisión over-the-top que presentaría contenido de archivo de la WWE y sus predecesores, todos pagos por visión (que también continuarían vendiéndose a través de proveedores de televisión) y programación original. [68] [69] [70]

A partir de 2015, la WWE comenzó a promocionar a Roman Reigns como su cara de la empresa desde que ganó el Royal Rumble Match de 2015 , en medio de una recepción mixta . En 2017, Roman Reigns se convirtió en su mayor vendedor de productos. [71]

El 25 de mayo de 2016, WWE relanzó la división de marcas, anunciada como la "Nueva Era". Posteriormente, Raw y SmackDown han presentado cada uno sus rosters, locutores, campeonatos y sets de ring/cuerdas únicos. Se llevó a cabo un draft para determinar qué luchadores aparecerían en qué programa. SmackDown también se trasladó de los jueves a los martes por la noche, que comenzaron el 19 de julio (la noche del draft antes mencionado), y se transmite en vivo en lugar del formato pregrabado anterior. [72]

Debido al regreso de la división de marcas, un nuevo Campeonato Mundial , llamado Campeonato Universal de la WWE , se introdujo en el evento SummerSlam del 21 de agosto de 2016 con Finn Bálor derrotando a Seth Rollins para convertirse en el Campeón Universal inaugural de la WWE. [73]

El 29 de noviembre de 2016, WWE presentó un nuevo programa específicamente para su división de peso crucero (luchadores de 205 libras y menos) llamado WWE 205 Live . [74] El programa se centra exclusivamente en aquellos luchadores que califican para la división. [75] [76] Los pesos crucero, que se convirtieron por primera vez en un elemento fijo en la WWE con el torneo Cruiserweight Classic , originalmente eran exclusivos de la marca Raw antes de conseguir su propia marca . [77]

El 15 de diciembre de 2016, la WWE estableció un nuevo Campeonato del Reino Unido de la WWE , y el campeón inaugural se decidió mediante un torneo de 16 hombres que se emitirá en WWE Network con luchadores del Reino Unido e Irlanda durante enero de 2017. El ejecutivo de la WWE Paul "Triple H" Levesque dijo que el plan final con el nuevo título y torneo era establecer una marca con sede en el Reino Unido con su propio programa de televisión semanal. [78] [79] Posteriormente, la WWE lanzó su marca con sede en el Reino Unido como una rama de NXT, NXT UK , en junio de 2018, con Johnny Saint como gerente general inaugural. [80]

A partir de septiembre de 2019, NXT tuvo un programa semanal en vivo de dos horas los miércoles por la noche en USA Network y WWE comenzó a promocionar NXT como su "tercera marca". [81] [82] Sin embargo, en 2021 NXT se trasladó a los martes por la noche, después de haber concedido las Wednesday Night Wars a la promoción rival All Elite Wrestling (AEW), y en septiembre de ese año fue reinstalado a su función original como marca de desarrollo para el roster principal (Raw y SmackDown), bajo el nombre "NXT 2.0".

En marzo de 2020, la WWE comenzó a verse afectada por el inicio estadounidense de la pandemia de COVID-19 . A mediados de marzo, tres de las cuatro principales ligas deportivas cerraron los vestuarios a los medios como medida de precaución. A medida que se introducían otras cancelaciones y aplazamientos deportivos, la WWE comenzó a filmar sus programas semanales en el Performance Center sin espectadores y con solo el personal esencial presente, comenzando con el episodio del 13 de marzo de SmackDown ; el episodio del 11 de marzo de NXT se había grabado en el Performance Center con fanáticos que pagaban, siendo así el último evento de la WWE en tener fanáticos con boletos presentes antes de que la pandemia entrara en pleno efecto. [83] [84] WrestleMania 36 estaba programado para llevarse a cabo el 5 de abril en el Raymond James Stadium en Tampa, pero el 16 de marzo se trasladó a Orlando para celebrarse a puerta cerrada. [85] [86] WrestleMania, así como Raw y SmackDown durante un período antes y después de WrestleMania, pasaron de transmisiones en vivo a un formato pregrabado. [87] NXT continuó transmitiéndose desde Full Sail University, pero con restricciones similares. [88] [89]

Las transmisiones en vivo regresaron el 13 de abril, y se mantuvieron los acuerdos existentes; WWE declaró a ESPN.com que "creemos que ahora es más importante que nunca brindar a las personas una distracción de estos tiempos difíciles", y que la programación de la compañía "reúne a las familias y brinda una sensación de esperanza, determinación y perseverancia". [88] [89] Posteriormente se informó que el gobernador de Florida, Ron DeSantis, había considerado a la WWE un negocio fundamental para la economía del estado y había agregado una excepción bajo la orden de quedarse en casa del estado para los empleados de una "producción profesional de deportes y medios" que está cerrada al público y tiene una audiencia nacional. [90] [91] La decisión fue recibida con críticas por parte de los medios de comunicación, y varios de ellos señalaron que las acciones de DeSantis ocurrieron el mismo día en que un comité de acción política pro- Donald Trump dirigido por Linda McMahon , quien anteriormente formaba parte del gabinete de Trump, se comprometió a gastar 18,5 millones de dólares en publicidad en Florida, y que, también el mismo día, Vince McMahon fue nombrado parte de un grupo asesor creado por Trump para diseñar una estrategia para relanzar la economía estadounidense. [92] [93] [94] [95]

El 15 de abril, la WWE inició una serie de recortes y despidos en respuesta a la pandemia, incluido el despido de varios artistas ( Karl Anderson , Kurt Angle , Aiden English , EC3 , Epico , Luke Gallows , Curt Hawkins , No Way Jose , Sarah Logan , Mike Kanellis , Maria Kanellis , Primo , Erick Rowan , Rusev , Lio Rush , Zack Ryder , Heath Slater y Eric Young ), tres productores ( Dave Finlay , Shane Helms y Lance Storm ), el árbitro Mike Chioda y varios aprendices y personal del NXT/Performance Center. Los ejecutivos de la WWE también sufrieron un recorte salarial y la compañía también suspendió la construcción de su nueva sede durante al menos seis meses. [96] Los despidos provocaron una reacción significativa por parte de los fanáticos; y Business Insider los llamó "furiosos". Tanto los fanáticos como varios medios de comunicación señalaron que, si bien la WWE afirmó que estas acciones eran "necesarias debido al impacto económico de la pandemia del coronavirus", la WWE también afirmó tener "recursos financieros sustanciales. El efectivo disponible y la capacidad de endeudamiento actualmente suman aproximadamente $ 0.5 mil millones". DeSantis afirmó que la WWE era "esencial", lo que significaba que la pérdida de ingresos de la empresa sería limitada. [92] [97]

En agosto de 2020, la WWE se mudó del Performance Center al Amway Center de Orlando para una residencia a largo plazo, transmitiendo episodios de Raw , SmackDown y PPV a través de una experiencia de visualización virtual para fanáticos llamada WWE ThunderDome . Dentro del ThunderDome, se utilizaron drones, láseres, pirotecnia, humo y proyecciones para mejorar las entradas de los luchadores a un nivel similar al de las producciones de PPV antes de la pandemia. Se instalaron casi 1000 paneles LED para permitir filas y filas de fanáticos virtuales. Los fanáticos podían asistir virtualmente a los eventos de forma gratuita, aunque tenían que reservar su asiento virtual con anticipación. [99] [100] [101] Durante este tiempo, Roman Reigns comenzó su histórico reinado del título mundial con el Campeonato Universal de la WWE , que eventualmente superaría los 1000 días; siendo el reinado del título mundial más largo en la WWE desde Hulk Hogan de 1984 a 1988. La WWE permaneció en el Amway Center hasta principios de diciembre antes de trasladar el ThunderDome al Tropicana Field en San Petersburgo, Florida . [102] [103] El ThunderDome se trasladó al Yuengling Center , ubicado en el campus de la Universidad del Sur de Florida en Tampa, a partir del episodio del 12 de abril de 2021 de Raw . [104] [105] En octubre de 2020, los eventos de NXT se trasladaron de Full Sail University al Performance Center en una configuración similar denominada Capitol Wrestling Center. Tenía muchas de las mismas características que el ThunderDome, pero con una pequeña multitud de fanáticos en vivo seleccionados incluidos, además de los fanáticos virtuales. El nombre también es un homenaje al predecesor de la WWE, Capitol Wrestling Corporation. [106] [107] El 21 de mayo, la WWE volvió a traer a los fans a tiempo completo, comenzando con una gira por 25 ciudades, poniendo así fin a la residencia en el ThunderDome. El episodio del 16 de julio de SmackDown dio inicio al regreso de la WWE a las giras, y tuvo lugar en el Toyota Center en Houston, Texas.

En enero de 2021, WWE trasladó WrestleMania 37 , que originalmente se iba a celebrar en Inglewood, California , el 28 de marzo, al Raymond James Stadium en Tampa, Florida (la ubicación original de WrestleMania 36) como un evento de dos noches el 10 y 11 de abril, con aficionados presentes, aunque con una capacidad limitada. [108] Este fue el primer evento de la WWE durante la pandemia en tener aficionados con entradas presentes con un máximo de 25.000 espectadores por noche con los protocolos COVID-19 establecidos. [109] También en esta época, la WWE Network en los Estados Unidos pasó a ser distribuida exclusivamente por Peacock el 18 de marzo de 2021 (antes de Fastlane y WrestleMania 37). La fusión de la WWE Network y Peacock no afectó al servicio fuera de los Estados Unidos. [110] El traslado a Peacock recibió algunas críticas de los fanáticos, particularmente debido a la fuerte política de censura de Peacock, la compañía comenzó a eliminar algunos de los contenidos que se consideraban momentos icónicos de la Attitude Era que Peacock consideraba inapropiados, estos contenidos archivados ya no estarían disponibles en ninguna de las plataformas autorizadas de la WWE. [111] [112] En medio de las críticas, en abril de 2021, el ejecutivo de la WWE, Triple H, defendió el traslado de la WWE a Peacock. [113]

NXT se trasladó a un horario de martes por la noche en 2021 y se reinició como NXT 2.0 más tarde ese año, restableciendo su función original como marca de desarrollo. El Performance Center se convirtió en la base de operaciones permanente de NXT, reemplazando a Full Sail. Se reanudaron las multitudes de capacidad máxima y el nombre de Capitol Wrestling Center se eliminó gradualmente. [114] En febrero de 2022, la marca 205 Live se disolvió y el programa 205 Live fue reemplazado por un nuevo programa de NXT llamado Level Up . [115]

El 24 de febrero de 2022, WWE lanzó una asociación con On Location, una empresa conocida por brindar experiencias de hospitalidad premium para eventos destacados. A través de la asociación, los espectadores tendrán acceso a paquetes de hospitalidad para los cinco eventos más importantes de la WWE, incluidos WrestleMania, SummerSlam, Royal Rumble, Survivor Series y Money in the Bank. Money in the Bank de 2022 fue el primer evento de la WWE en ofrecer paquetes de hospitalidad premium. Estos paquetes de boletos y viajes incluyen asientos de primera, ofertas de hospitalidad premium y encuentros con luchadores y leyendas actuales de la WWE. [116]

El 17 de junio de 2022, en medio de una investigación de la Junta Directiva de la WWE sobre el supuesto "dinero para el silencio" pagado a un ex empleado por Vince McMahon después de una aventura, el Sr. McMahon renunció como presidente y director ejecutivo de la WWE y fue reemplazado por su hija, Stephanie McMahon, como presidenta interina de la WWE. [117] [118] A pesar del cambio, Vince McMahon salió en WWE SmackDown , esa noche abriendo el programa con un breve discurso, cuyos aspectos más destacados "entonces, ahora, para siempre y lo más importante juntos" fueron citados por varios medios de comunicación como Vince haciéndole saber a la gente que todavía estaba en control creativo detrás de escena. [119] [120] El 22 de julio de 2022, Vince McMahon se retiró oficialmente, declarando en Twitter: "A los 77 años, es hora de que me retire. Gracias, Universo WWE. Entonces. Ahora. Para siempre. Juntos". [121] Tras el retiro de Vince, Stephanie McMahon fue nombrada oficialmente presidenta, mientras que ella y Nick Khan fueron nombrados codirectores ejecutivos de la WWE. [122] Triple H asumiría el cargo de jefe creativo, mientras retomaría su puesto como vicepresidente ejecutivo de relaciones con el talento y luego sería ascendido a director de contenido. [123] [124] Los comentaristas han destacado la importancia del retiro de McMahon, diciendo que marcó el inicio histórico de un nuevo período en la historia de la WWE. [125] [126] [127] [128] [129] [130] [131] El evento SummerSlam 2022 celebrado el 30 de julio de 2022 fue el primer evento de pago por visión de la WWE que se celebró bajo el liderazgo de Stephanie McMahon y Triple H. [132] [133]

El 18 de agosto de 2022, el miembro del Salón de la Fama de la WWE, Shawn Michaels, fue ascendido a Vicepresidente Creativo de Desarrollo de Talentos de la WWE. [134] El 6 de septiembre de 2022, WWE anunció el ascenso de Paul 'Triple H' Levesque a Director de Contenido . [135] El 6 de enero de 2023, Vince McMahon anunció sus intenciones de regresar a la empresa antes de las negociaciones de los derechos de los medios. Los derechos mediáticos de la WWE con Fox y USA Network expirarán en 2024. [136] Ese mismo mes, JP Morgan fue contratado para manejar una posible venta de la empresa, con empresas como Comcast (propietarios de NBCUniversal y socios de la WWE desde hace mucho tiempo), Fox Corp (emisora de SmackDown ), Disney (propietarios de ESPN ), Warner Bros. Discovery (emisores de la promoción rival AEW), Netflix , Amazon , Endeavor Group Holdings (propietarios de UFC ) y Liberty Media en la especulación para comprar la empresa [137] con CAA y el Fondo de Inversión Pública de Arabia Saudita también en la lista. [138] El 10 de enero de 2023, Stephanie McMahon renunció como presidenta y codirectora ejecutiva. [139] El mismo día, Vince McMahon asumió el papel de presidente ejecutivo de la WWE, mientras que Nick Khan se convirtió en el único director ejecutivo de la WWE. [140]

El 3 de abril de 2023, WWE y Endeavor llegaron a un acuerdo según el cual WWE se fusionaría con la empresa matriz de UFC, Endeavor, para formar una nueva empresa, que saldría a bolsa en la Bolsa de Valores de Nueva York (NYSE) bajo el símbolo " TKO ". Endeavor tendrá una participación del 51% en "TKO", y los accionistas de WWE tendrán una participación del 49%, [141] valorando a WWE en $ 9.1 mil millones. [142] [143] Esto marcó la primera vez que WWE no ha sido controlada mayoritariamente por la familia McMahon . [144] Vince McMahon se desempeñará como presidente ejecutivo de la nueva entidad, el CEO de Endeavor, Ari Emanuel, se convertirá en CEO, con Mark Shapiro como presidente y director de operaciones. Emanuel no asumirá ningún rol creativo y se espera que el jefe creativo de WWE, Paul Levesque, permanezca en su puesto, [145] y Nick Khan se convertirá en presidente de WWE después de la fusión (no muy diferente del papel de Dana White como presidente de UFC). [143] [142] [146] [145] El acuerdo además le otorgó a McMahon un mandato vitalicio como presidente ejecutivo, el derecho a nominar a cinco representantes de la WWE en la junta de 11 miembros, así como derechos de veto sobre ciertas acciones de la nueva compañía. [147] Además, McMahon será dueño del 34% de la nueva compañía, con un interés de voto del 16%. [148]

Emanuel afirmó que esta fusión "uniría a dos empresas líderes en el ámbito del deporte y el entretenimiento" y proporcionaría "sinergias operativas significativas". [143] Vince McMahon afirmó que "las empresas familiares tienen que evolucionar por todas las razones correctas", y que "dado el increíble trabajo que Ari y Endeavor han hecho para hacer crecer la marca UFC (casi duplicando sus ingresos en los últimos siete años) y el inmenso éxito que ya hemos tenido al asociarnos con su equipo en una serie de emprendimientos, creo que este es sin duda el mejor resultado para nuestros accionistas y otras partes interesadas". [142]

La fusión entre WWE y UFC en TKO Group Holdings (TKO) se completó el 12 de septiembre de 2023. [149] Aunque el nombre legal de la empresa siguió siendo World Wrestling Entertainment, LLC, permaneció unida a UFC como parte de la nueva entidad "TKO". Como parte del acuerdo, WWE y UFC siguieron siendo divisiones separadas de la nueva entidad que presentaba lucha libre profesional y artes marciales mixtas respectivamente. [150] [151] El primer programa de la WWE bajo el régimen Endeavor fue el episodio del 12 de septiembre de 2023 de NXT que abrió con Ilja Dragunov derrotando a Wes Lee en un combate individual, y en el evento principal Becky Lynch derrotó a Tiffany Stratton para ganar el Campeonato Femenino de NXT. [152] El primer PPV de la WWE bajo TKO fue NXT No Mercy el 30 de septiembre de 2023. [153] El popular luchador CM Punk regresó a la WWE a fines de 2023 y en su primer combate a su regreso derrotó a Dominik Mysterio en el WWE MSG Show el 26 de diciembre de 2023. [154]

El 23 de enero de 2024, Dwayne Johnson , también conocido como "The Rock", se unió a la junta directiva de TKO Group Holdings . [155] [156] [157] Tres días después, el 26 de enero, Vince McMahon renunció una vez más debido a más acusaciones de conducta sexual inapropiada, y Ari Emanuel obtuvo un mayor control como nuevo presidente de TKO. [158]

El 1 de abril de 2024, Triple H declaró que la WWE había entrado en "otra era". [159] Al día siguiente, antes de WrestleMania XL , la empresa matriz de TKO, Endeavor, fue privatizada por su mayor inversor, Silver Lake, un año después de los tres años de funcionamiento de Endeavor como empresa pública donde Endeavor compró la WWE un año antes. [160] [161] El 3 de abril, el luchador de la WWE Cody Rhodes acuñó el término "Era del Renacimiento" para el período. [162] En WrestleMania XL, la WWE debutaría oficialmente con una nueva introducción de firma antes del primer combate del evento. Paul "Triple H" Levesque presentaría a los fanáticos presentes, "Bienvenidos a un nuevo tiempo, bienvenidos a una nueva era", [163] y en la segunda noche de WrestleMania, Stephanie McMahon reiteraría esto, refiriéndose a ella como la "era Paul Levesque". [164] El 7 de abril, en el evento principal de la segunda y última noche del evento, Cody Rhodes derrotó a Roman Reigns para ganar el Campeonato Universal Indiscutible de la WWE . [165]

El 4 de mayo de 2024, WWE celebró Backlash France , su primer evento de pago por visión en Francia . [166] El 23 de enero de 2024, WWE anunció que WWE Raw se trasladará al servicio de transmisión Netflix en enero de 2025.

Nota: Las tablas con una columna de "Días recomendados" significan que la WWE reconoce oficialmente un número diferente de días que un luchador ha tenido un título, generalmente debido a que un evento se transmite con retraso .

Los colores y símbolos indican la marca local de los campeones.

Crudo

Bofetada

Abierto

Estos títulos están disponibles para las tres marcas: Raw, SmackDown y NXT.

La WWE contrata a la mayoría de sus talentos con contratos exclusivos, lo que significa que los talentos pueden aparecer o actuar solo en la programación y los eventos de la WWE. No se les permite aparecer o actuar para otra promoción a menos que se hagan arreglos especiales de antemano. La WWE mantiene estrictamente en privado el salario, la duración del empleo, los beneficios y todos los demás detalles contractuales de todos los luchadores. [184]

La WWE clasifica a sus luchadores profesionales como contratistas independientes y no como empleados. Un estudio de la revista de derecho de la Universidad de Louisville concluyó que, tras aplicar la prueba de 20 factores del Servicio de Impuestos Internos (IRS), 16 factores "indican claramente que los luchadores son empleados". Sin embargo, como resultado de que la WWE los denomine contratistas independientes, "se les niegan innumerables beneficios a los que de otro modo tendrían derecho". [185]

En diciembre de 2021, la WWE reveló un nuevo contrato de reclutamiento para atletas que actualmente asisten a la universidad. Los contratos de nombre, imagen y semejanza aprobados por la NCAA son denominados por la WWE "acuerdos de siguiente línea". [186]

El 19 de octubre de 1999, WWF, que anteriormente había sido propiedad de la empresa matriz Titan Sports, lanzó una oferta pública inicial como una empresa que cotiza en bolsa, cotizando en la Bolsa de Valores de Nueva York (NYSE) con la emisión de acciones valoradas en ese momento en $ 172,5 millones. [45] La empresa ha cotizado en la NYSE desde su lanzamiento bajo el símbolo de cotización WWE. [46]

La empresa se ha promocionado activamente como una empresa que cotiza en bolsa a través de presentaciones en conferencias de inversores y otras iniciativas de relaciones con inversores. [187] En junio de 2003, la empresa comenzó a pagar un dividendo sobre sus acciones de 0,04 dólares por acción. [188] En junio de 2011, la empresa redujo su dividendo de 0,36 dólares a 0,12 dólares. [189] En 2014, las preocupaciones sobre la viabilidad de la empresa provocaron amplias fluctuaciones en el precio de sus acciones. [190]

Durante los años 1980 y 1990, se pensaba que George Zahorian distribuía rutinariamente esteroides y otras drogas a los luchadores de la WWF, supuestamente con la aprobación del dueño de la WWF Vince McMahon. [191] [ ¿ Fuente poco confiable? ] En 1993, McMahon fue acusado en un tribunal federal después de que la controversia de los esteroides envolviera a la promoción, lo que lo obligó a ceder temporalmente el control de la WWF a su esposa Linda. [192] El caso fue a juicio en 1994, donde el propio McMahon fue acusado de distribuir esteroides a sus luchadores. [193] Un testigo de cargo notable fue Nailz (nombre real: Kevin Wacholz), un ex luchador de la WWF que había sido despedido después de una confrontación violenta con McMahon. Nailz testificó que McMahon le había ordenado usar esteroides, pero su credibilidad fue puesta en duda durante su testimonio, ya que declaró repetidamente que "odiaba" a McMahon. [194] [195] El jurado más tarde absolvió a McMahon de los cargos y él reanudó su papel en las operaciones diarias de la WWF. [196]

A principios de los años 1990, Mel Phillips, anunciador del ring y jefe del equipo de ring de la WWF, fue acusado de abusar sexualmente de varios "ring boys", niños menores de edad que trabajaban como parte del equipo de ring de la WWF. [197] En 1992, Phillips fue despedido de la WWF. [197] Phillips había sido despedido temporalmente de la WWF en 1988 por conducta sexual inapropiada, pero fue traído de regreso ese mismo año. [197]

El 29 de octubre de 2020, Business Insider informó que Vince McMahon y su esposa Linda estaban al tanto de las acusaciones contra Phillips, pero deliberadamente hicieron la vista gorda . Según las solicitudes de la Ley de Libertad de Información para los registros judiciales sobre el escándalo del chico del ring, Vince, bajo juramento, declaró que era consciente de que Phillips había tomado un "interés peculiar y antinatural en los niños", pero se negó a tomar medidas contra él. [197] Un testimonio adicional reveló que Vince, después de traer a Phillips de regreso a la WWF en 1988, le había hecho prometer a Phillips que "dejaría de perseguir niños". [197] Business Insider también informó que, bajo la directiva de Vince y Linda McMahon, la WWF comenzó una campaña para desacreditar a Tom Cole, uno de los niños que había acusado a Phillips de conducta sexual inapropiada, y a la familia de Cole. [197] En respuesta al informe de Business Insider , Jerry McDevitt, abogado de la WWE, afirmó que las acusaciones contra Phillips estaban relacionadas con su inusual "fetiche por los pies", pero no incluían "nada que se aproximara a las formas convencionales de abuso sexual como la violación, la sodomía, etc." [197] Además, describió las afirmaciones de que los McMahon sabían sobre las acusaciones contra Phillips pero se negaron a tomar medidas y continuaron empleándolo con la condición de que "dejara de perseguir niños" como "extravagantes" y "una difamación clásica". [197]

Tom Cole murió en febrero de 2021. [198]

En 1996, Titan Sports, la empresa matriz de la World Wrestling Federation, demandó a World Championship Wrestling (WCW) por la WCW, insinuando que Scott Hall y Kevin Nash (Razor Ramon y Diesel) estaban invadiendo la WCW en nombre de la WWF. Esto dio lugar a una serie de demandas presentadas por ambas empresas a medida que la Monday Night War se calentaba. La demanda se prolongó durante años y terminó con un acuerdo en 2000. Uno de los términos le dio a la WWF el derecho a ofertar por los activos de la WCW si la empresa se liquidaba. AOL Time Warner, la entonces empresa matriz de la WCW, canceló los programas de televisión de la WCW en marzo de 2001 y vendió los activos de la empresa a la WWF. [199] [ ¿ Fuente poco fiable? ]

El 23 de mayo de 2012, Total Nonstop Action Wrestling (TNA) demandó al ex empleado Brian Wittenstein y a la WWE. La demanda alegó que Wittenstein violó un acuerdo de confidencialidad y compartió información confidencial con la WWE, lo que representó una ventaja comparativa en la negociación con talentos de lucha libre bajo contrato con TNA. Posteriormente fue contratado por la WWE, después de lo cual TNA afirmó que Wittenstein violó el acuerdo al descargar secretos comerciales confidenciales de TNA y proporcionar esa información a la WWE. Aunque la WWE despidió a Wittenstein y alertó a los funcionarios de TNA sobre la divulgación de la información, TNA afirmó que la WWE tuvo acceso a la información durante tres semanas antes de la divulgación y, en este tiempo, la WWE utilizó información contractual secreta e intentó robar su talento en violación de la Ley de Secretos Comerciales Uniformes de Tennessee . [200] La demanda fue retirada formalmente sin perjuicio por el demandante, TNA, el 15 de enero de 2013, bajo un "Aviso de Desistimiento Voluntario" que no ofrece ninguna resolución sobre los méritos de la demanda y permite a TNA potencialmente volver a presentarla en una fecha posterior. [201]

El 11 de enero de 2022, Major League Wrestling (MLW) presentó una demanda antimonopolio contra la WWE, acusándola de interferir en acuerdos de televisión y transmisión y de robar talentos. A través de la demanda, se reveló que un acuerdo de transmisión con Tubi , propiedad de Fox Corporation, se rescindió debido a que WWE supuestamente amenazó con retirar su programación de la cadena de transmisión hermana Fox . La demanda también alega que WWE presionó a Vice TV para que se retirara de las negociaciones con MLW. [202] [203]

El 23 de mayo de 1999, Owen Hart cayó y murió en Kansas City, Missouri durante el evento PPV Over the Edge en un truco que salió mal. WWF rompió el kayfabe al hacer que el comentarista de televisión Jim Ross le dijera repetidamente a quienes miraban en vivo en PPV que lo que acababa de suceder no era un ángulo o una historia de lucha libre y que Hart estaba gravemente herido, enfatizando la gravedad de la situación. [204] Si bien se hicieron varios intentos de reanimarlo, murió a causa de sus heridas. Más tarde se reveló que la causa de la muerte fue una hemorragia interna por traumatismo contundente . La gerencia de WWF eligió polémicamente continuar con el evento. [205] Más tarde, Jim Ross reveló la muerte de Hart a los espectadores en casa durante el PPV, pero no a la multitud en la arena. [206] Si bien el programa continuó, nunca fue lanzado comercialmente por WWF Home Video . En 2014, quince años después de su muerte, WWE Network transmitió el evento por primera vez. Antes del inicio se muestra una pequeña fotografía en homenaje que informa a los fans que Hart murió durante la transmisión original. Todas las imágenes de Hart fueron editadas y eliminadas del evento. La declaración dice: "En memoria de Owen Hart 7 de mayo de 1965 - 23 de mayo de 1999, quien falleció accidentalmente durante esta transmisión". [207] Cuatro semanas después del evento, la familia Hart demandó a la WWF por lo peligrosa y mal planificada que fue la maniobra, y porque el sistema de arnés era defectuoso. [208] Después de más de un año y medio en el caso, se llegó a un acuerdo el 2 de noviembre de 2000, por el que la WWF le dio a la familia Hart 18 millones de dólares. [209] [210] [211]

En abril de 2000, USA Networks, Inc. , la empresa matriz de USA Network , había presentado una demanda contra World Wrestling Federation Entertainment Inc. en un intento por mantener Raw is War y toda la programación de la WWF después de que la WWF abriera una guerra de ofertas un mes antes. [212] La oferta propuesta por Viacom incluía una inversión de capital de $30 millones a $50 millones en la empresa y la transmisión en transmisión, vallas publicitarias y radio de ambos combates de lucha libre junto con la entonces lanzada XFL .

El 27 de junio de 2000, la Corte Suprema de Delaware falló a favor de la WWF. [213] Al día siguiente, Viacom ganó los derechos de toda la programación de la WWF por $12.6 millones, incluyendo Raw is War en TNN/Spike TV , un renovado Sunday Night Heat en MTV y retuvo SmackDown! en UPN después de la fusión con CBS en 1999. La demanda se centró en la afirmación de USA de que no tenía que igualar cada aspecto de una oferta de Viacom para satisfacer una cláusula de derecho de primera negativa en su contrato que permitía que su acuerdo con la WWF continuara. [214] [215] [216] En 2005, la programación de la WWE (excluyendo SmackDown! ) regresó a USA Network (ahora propiedad de NBCUniversal ) y mantiene su relación hasta el día de hoy. [217]

En 1994, Titan Sports había llegado a un acuerdo con el Fondo Mundial para la Naturaleza (también conocido como WWF), una organización ambientalista, en relación con el uso por parte de Titan del acrónimo "WWF", que ambas organizaciones habían estado utilizando desde al menos marzo de 1979. Según el acuerdo, Titan había acordado dejar de utilizar el acrónimo escrito "WWF" en relación con su promoción de lucha libre, y minimizar (aunque no eliminar) los usos hablados de "WWF" en sus transmisiones, particularmente en comentarios con guión. A cambio, el grupo ambientalista (y sus afiliados nacionales) acordaron abandonar cualquier litigio pendiente contra Titan, y acordaron no impugnar el uso por parte de Titan del nombre completo "World Wrestling Federation" o el logotipo vigente en ese momento de la promoción. [218]

En 2000, el Fondo Mundial para la Naturaleza demandó a World Wrestling Federation Entertainment Inc. en el Reino Unido, alegando varias violaciones del acuerdo de 1994. [219] El Tribunal de Apelación estuvo de acuerdo en que la empresa de promoción había violado el acuerdo de 1994, particularmente en lo que respecta a la comercialización. El último evento televisado que comercializó el logotipo de WWF fue el pago por visión con sede en el Reino Unido Insurrextion 2002. El 5 de mayo de 2002, la empresa lanzó su campaña de marketing "Get The F Out" y cambió todas las referencias en su sitio web de "WWF" a "WWE", al tiempo que cambiaba la URL de WWF.com a WWE.com . [59] Al día siguiente, el cambio de nombre oficial de World Wrestling Federation Entertainment, Inc. a World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc., se publicitó en un comunicado de prensa y durante una transmisión de Raw , desde el Hartford Civic Center .

Tras el cambio de nombre, el uso del logo "scratch" de la WWF quedó prohibido en todas las propiedades de la WWE. Además, las referencias anteriores a la marca registrada y las iniciales de la WWF en "circunstancias específicas" fueron censuradas. [220] A pesar del litigio, a la WWE todavía se le permitió el uso del logo original de la WWF, que se utilizó desde 1979 hasta 1994 y que había sido explícitamente exento en virtud del acuerdo de 1994, así como el logo similar "New WWF Generation", que se utilizó desde 1994 hasta 1998. Además, la empresa todavía podía hacer uso de los nombres completos de "World Wrestling Federation" y "World Wrestling Federation Entertainment" sin consecuencias. En 2003, la WWE ganó una decisión limitada para continuar comercializando ciertos videojuegos clásicos de THQ y Jakks Pacific que contenían el logo "scratch" de la WWF. [221] Sin embargo, el empaque de esos juegos tenía todas las referencias a la WWF reemplazadas por la WWE.

A partir del episodio número 1000 de Raw en julio de 2012, el logotipo "scratch" de la WWF ya no está censurado en las imágenes de archivo debido a que la WWE llegó a un nuevo acuerdo con el Fondo Mundial para la Naturaleza. [222] Además, la F en las iniciales de la WWF ya no está censurada cuando se habla o se escribe en texto sin formato en las imágenes de archivo. Desde entonces, se han agregado combates completos y otros segmentos con las iniciales de la WWF y el logotipo "scratch" al sitio web de la WWE y a WWE Classics on Demand y, finalmente, al servicio WWE Network . Esto también incluye los lanzamientos de WWE Home Video desde octubre de 2012, comenzando con el relanzamiento de Brock Lesnar: Here Comes The Pain . [223] Aunque las iniciales y el logotipo de la WWF ya no están censurados en las imágenes de archivo, la WWE no puede usar las iniciales o el logotipo de la WWF en ninguna imagen, empaque o publicidad nueva y original. [224]

Harry "Slash" Grivas y Roderick Kohn presentaron una demanda contra la WWE en junio de 2003 debido a que la música se usaba para su programación y DVD sin consentimiento ni pago. También afirmaron una violación de los derechos de la música original utilizada por ECW que la WWE había estado usando durante la historia de Invasion de 2001. El caso se resolvió para ambas partes con un acuerdo que vio a la WWE comprar el catálogo directamente en enero de 2005. [225]

En 1993, Jim Hellwig , conocido en la WWF como "The Ultimate Warrior", cambió legalmente su nombre al monónimo Warrior. [226] [227] Este nombre de una sola palabra aparece en todos los documentos legales pertenecientes a Warrior, y sus hijos llevan el nombre de Warrior como su apellido legal. [228] Warrior y la WWF participaron en una serie de demandas y acciones legales en 1996 y 1998, [229] donde ambas partes buscaron una declaración de que eran dueños de los personajes, Warrior y Ultimate Warrior, tanto bajo contrato como por la ley de derechos de autor. El tribunal dictaminó que Warrior tenía derecho legal a usar el truco, el vestuario, los diseños de pintura facial y los gestos del personaje "Warrior". [230]

El 27 de septiembre de 2005, la WWE lanzó un documental en DVD centrado en la carrera de lucha libre retrospectiva de Warrior, titulado The Self-Destruction of the Ultimate Warrior . El DVD presentaba clips de sus feudos y combates más notables junto con comentarios de estrellas de la WWE pasadas y presentes (la mayoría de los cuales son poco favorecedores). El DVD ha provocado cierta controversia debido a las acusaciones de difamación de Warrior por parte de la WWE en su contra. Originalmente, se le pidió a Warrior que ayudara con la producción del DVD, pero como se negó a trabajar con la WWE, hubo cierta animosidad resultante entre Warrior y la WWE debido a que Warrior afirmó que la WWE tenía prejuicios. [231] En enero de 2006, Warrior presentó otra demanda contra la WWE en un tribunal de Arizona por la representación de su carrera de lucha libre en el DVD The Self-Destruction of the Ultimate Warrior . [232] El 18 de septiembre de 2009, la demanda de Warrior en Arizona fue desestimada.

Warrior returned to WWE to be inducted into the Hall of Fame. During his induction, he mentioned that WWE should create an award to honor those behind the scenes called the Jimmy Miranda Award, named after a long time WWE employee who died. Warrior died three days after being inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame. WWE decided to create the Warrior Award, an award for people "who embodied the spirit of the Ultimate Warrior." The award was later given to Connor Michalek (a child who died from cancer), Joan Lunden (a journalist who was diagnosed with cancer), and Eric LeGrand (a former college football player who became a quadriplegic after an in-game injury). In October 2017, WWE used the tagline "Unleash Your Warrior" when promoting Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Since Warrior's death, WWE has been accused of whitewashing and ignoring Warrior's bigoted and controversial past comments.[233] Pro Wrestling Torch described Warrior in real-life having made public "vile, bigoted, hateful, judgmental comments", citing as an example that regarding Bobby Heenan's cancer diagnosis, Warrior said, "Karma is just a beautiful thing to behold."[234] Vice wrote that "completely whitewashing his past and elevating his likeness to a bland symbol of corporate altruism is shockingly tone-deaf, especially for a company that's at least outwardly trying to appear progressive, inclusive and diverse."[233]

Under Section 9.13(a) of WWE's booking contract, commonly known as the "morals clause", the company has a zero-tolerance policy involving domestic violence, child abuse and sexual assault. Upon arrest and conviction for such crimes, a WWE talent shall be immediately suspended and their contract terminated.[235]

Starting in 2014, numerous former WWE talent filed multiple lawsuits against WWE alleging that WWE did not protect and hid information from their talent about concussions and CTE. The former talent claimed physical and mental health issues as a result of physical trauma they experience in WWE. The lawsuits were filed by attorney Konstantine Kyros. US District Judge Vanessa Lynne Bryant dismissed many of the lawsuits in September 2018.[258] In September 2020, the lawsuits were dismissed by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.[259] The Supreme Court of the United States subsequently declined to hear the case in April 2021.[260]

The events promoted in Saudi Arabia by WWE have been subjected to criticism due to allegations of sportswashing. WWE has been accused of contributing to Saudi Arabia's discrimination of LGBT people and women by holding events in the country.[261][262]

WWE's relation with Saudi Arabia has been condemned by activist groups such as Code Pink and several politicians.[263][264][265][266]

Prior to her death on May 15, 2019, former WWE wrestler Ashley Massaro alleged that she was sexually assaulted at a US military base during a 2006 WWE tour of Kuwait by a man posing as a doctor, and that WWE officials persuaded her to not report it to the appropriate authorities as they did not want it to affect the company's relationship with the military.[267] WWE officials would later claim they had no knowledge of Massaro's alleged sexual assault.

After her death, an affidavit by Massaro describing the sexual assault allegations in detail was subsequently released by the law firm that represented her.[268] In response, WWE said that their executives had not been previously informed of the allegations described in the affidavit.[269] Despite previous denials from WWE about having knowledge of her allegation, in February 2024 an attorney representing former WWE Head of Talent Relations John Laurinaitis stated that: "most upper level management at sometime became aware of the [Massaro] allegations and ensured all proper WWE protocols were followed, including privacy for the alleged victim."[270] That month, Vice News reported that the Naval Criminal Investigative Service had investigated Massaro's allegations from June 2019 to January 2020, although no further information about the investigation other than its existence is known.[271] A further report by Vice News revealed that Massaro had accused Vince McMahon of "preying on female WWE wrestlers" and that she believed he had tried to sabotage her wrestling career after she rejected an advance from him.[272]

One of the first allegations against Vince McMahon was made on April 3, 1992, when Rita Chatterton, a former referee noted for her stint as Rita Marie in the WWF in the 1980s and for being the first female referee in the WWF (possibly in professional wrestling history),[273] made an appearance on Geraldo Rivera's show Now It Can Be Told. She claimed that on July 16, 1986, McMahon tried to force her to perform oral sex on him in his limousine; when she refused, he raped her.[274] Former wrestler Leonard Inzitari has corroborated Chatterton's allegation.[275] Several years later, on February 1, 2006, McMahon was accused of sexual harassment by a worker at a tanning bar in Boca Raton, Florida.[276] At first, the charge appeared to be discredited because McMahon was in Miami for the 2006 Royal Rumble at the time. It was soon clarified that the alleged incident was reported to police on the day of the Rumble, but actually took place the day before.[277] On March 25, it was reported that no charges would be filed against McMahon as a result of the investigation.[278] Both Chatterton and a separate tanning spa worker who alleged that McMahon sexually assaulted her in California in 2011 filed civil sex abuse lawsuits against him in late 2022.[279] McMahon would agree to pay Chatterton an undisclosed multimillion-dollar legal settlement.[280]

In 2014, activist investor Emmanuel Lemelson stated that he believed the company had made material misrepresentations in its financial reporting[281][282] and called for new leadership or a sale of the company.[283] Lemelson's analysis was credited with an $800 million drop in the market capitalization of the stock.[284][285][286]

In April 2022, the WWE board began investigating a $3 million hush-money settlement that McMahon paid over an alleged affair with a former employee of the company. The investigation also revealed other nondisclosure agreements related to misconduct claims by other women in the company against McMahon and executive John Laurinaitis, totaling $12 million.[287][288][289] This eventually led to McMahon retiring from all of his positions on July 22, 2022, and a change in leadership of the WWE for the first time since 1982;[290][291][292] he would later return to the company in January 2023 as executive chairman.[280]

The company would eventually report $19.6 million in unrecorded payments made by Vince McMahon between 2006 and 2022.[293]

In January 2024, McMahon's history of having a role with the WWE ended amid new allegation by ex-WWE employee Janel Grant.[294] Grant accused McMahon and John Laurinaitis of not only sexually assaulting her, but also sex trafficking.[17][294] The allegation also led to Slim Jim pausing its sponsorship of WWE events.[17]

WWE uses a variety of special terms in promoting their product, such as describing the wrestling industry as sports entertainment. The fan base is referred to as the "WWE Universe" for the main roster shows, while for NXT shows, they are also referred to as the "NXT Universe". Main roster wrestlers are designated "WWE Superstars", while those in NXT are also referred to as "NXT Superstars". Retired wrestlers are described as "WWE Legends", while those who have been inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame are called "Hall of Famers".[295]

On February 24, 2014, WWE launched WWE Network, an over-the-top subscription streaming service[68][69][70] The service, which was initially proposed as a linear pay television service,[296][297] carries all WWE pay-per-view events, original programming (including in-ring programs, as well as documentary and reality programming highlighting the promotion and its history), and access to WWE library content such as classic pay-per-views and television episodes from WWE and other promotions that it had acquired.[298] The service reached 1,000,000 subscribers on January 27, 2015, in less than one year of its launch, with WWE claiming that it was thus "the fastest-growing digital subscription service ever".[299]

In May 2014, WWE and NBCUniversal agreed to a new contract that would see both Raw and SmackDown continue on NBC owned networks the USA Network and Syfy.[300] In January 2016, SmackDown would change networks to the USA Network. The contract with NBCUniversal expires in 2019.[301] On November 17, 2016, WWE and Sky Deutschland signed a multi-year agreement to distribute WWE's premier pay-per-view events and broadcast Raw and SmackDown Live on SKY Sports starting in April 2017.[302] On April 10, 2017, WWE and DAZN, made Raw and SmackDown available live in Japan with Japanese commentary.[303] On April 27, 2017, WWE and TV5, reached a new agreement to broadcast one-hour editions of SmackDown.[304] On May 12, 2017, WWE and Saran Media, reached a new multi-year agreement to televise Raw and SmackDown.[305] On July 10, 2017, WWE and AB 1, extended their partnership into its 18th year with a new, multi-year agreement to broadcast WWE programming.[306] On July 20, 2017, WWE and SuperSport, reached a new, multi-year agreement to broadcast WWE programming live for the first time in more than 50 countries.[307] On August 1, 2017, WWE and Foxtel, extend their partnership into its 18th year with a new agreement to broadcast WWE programming.[308] On August 8, 2017, WWE and Canal 1, a new agreement to broadcast One-hour editions of Raw and SmackDown.[309] On August 16, 2017, WWE and Nine Network reached a broadcast agreement to air weekly one-hour versions of Raw and SmackDown.[310] On August 24, 2017, WWE and Flow reached a multi-year agreement to televise WWE's flagship programmes Raw and SmackDown.[311] On September 7, 2017, WWE and TVA Sports reached a multi-year agreement to air a weekly, one-hour only edition of Raw, in French in Canada.[311] On October 24, 2017, WWE and Sport TV reached a multi-year agreement to air Raw and SmackDown.[312] On December 15, 2017, WWE and IB SPORTS, they will extend their partnership with a new agreement to broadcast WWE programming live for the first time in South Korea.[313] On December 18, 2017, WWE and SPS HD, reached an agreement to broadcast Raw and SmackDown on SPS Sports for the first time in Mongolia.[314]

On December 13, 2017, WWE and Facebook introduced a new Internet in-ring series called WWE Mixed Match Challenge that will stream live in the U.S. exclusively on Facebook Watch. Premiering on January 16, 2018, the 12-episode series will feature wrestlers from both the Raw and SmackDown rosters competing in a single-elimination mixed tag-team tournament to win $100,000 to support the charity of their choice. Each episode will be 20 minutes long and will air at 10 p.m. ET/7 p.m. PT.[315]

Starting on March 18, 2021 (ahead of Fastlane and WrestleMania 37), the WWE Network in the United States became exclusively distributed by Peacock. The merger of the WWE Network and Peacock did not affect the service outside of the United States.[110]

On September 9, 2022, WWE reached a new multi-year partnership deal with The Foxtel Group,[316] which allowed Foxtel to be the exclusive distributor of WWE in Australia, starting in early December 2022, allowing all pay-per-view events and original programming to be available on a dedicated WWE channel, Foxtel Now, and on Binge, with no additional cost to Foxtel and Binge users.

As announced on, January 23, 2024, Netflix will exclusively broadcast WWE's flagship weekly wrestling show Raw starting in January 2025 in the United States, Latin America, Canada and the United Kingdom. Netflix will also be the exclusive home of all WWE content outside of the U.S., which will include documentaries, original series, SmackDown, NXT and Premium Live Events such as WrestleMania, SummerSlam and the Royal Rumble.[317][318][319]

In March 2015, WWE joined forces with Authentic Brands Group to relaunch Tapout, formerly a major MMA-related clothing line, as a more general "lifestyle fitness" brand. The apparel, for men and women, was first released in spring of 2016. WWE markets the brand through various products, including beverages, supplements, and gyms.[350] WWE will hold a 50% stake in the brand, and so will advertise it regularly across all its platforms, hoping to give it one billion impressions a month, and take some of the fitness market from Under Armour. WWE wrestlers and staff have been shown wearing various Tapout gear since the venture began.[351]

Though an infrequent occurrence, during its history WWE has worked with other wrestling promotions in collaborative efforts.

During the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s, WWE had working relationships with the Japanese New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW), Universal Wrestling Federation (UWF), Universal Lucha Libre (FULL), and the Mexican Universal Wrestling Association (UWA). These working relationships led to the creations of the WWF World Martial Arts, Light Heavyweight and Intercontinental Tag Team championships.[352][353][354][355]

During the period of 1992–1996, WWE had talent exchange agreements with the United States and Japanese independent companies Smokey Mountain Wrestling (SMW),[356][357] Super World of Sports (SWS),[358] WAR,[359] and the United States Wrestling Association (USWA).[360]

In 1997, the company did business with Mexico's AAA promotion, bringing in a number of AAA wrestlers for the Royal Rumble event and namesake match.[361][362]

In 1997, WWE would also do business with Japan's Michinoku Pro Wrestling (MPW), bringing in MPW talent to compete in the company's light heavyweight division and in their 1997 Light Heavyweight Championship tournament.[363]

From 1997 to 1998, WWE partnered with the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA), with WWE hosting NWA matches on its programming. These matches were presented as part of "an invasion" of WWE by NWA wrestlers.

In 2015, WWE entered a partnership with Evolve – a U.S. independent promotion that WWE used as a scouting group for potential signees for the NXT brand.[364] In 2020, WWE would purchase Evolve for an undisclosed amount.[365]

In 2016, WWE partnered with England's Progress Wrestling with Progress hosting qualifying matches for WWE's Cruiserweight Classic.[366] In 2017, Progress talent would participate in the WWE United Kingdom Championship Tournament[367] and at WWE's WrestleMania Axxess events.[368] Three years later in 2020, Progress programming began airing on the WWE Network.

In 2017, WWE partnered with Scotland's Insane Championship Wrestling (ICW) with some ICW talent appearing in the WWE United Kingdom Championship Tournament and at WWE's WrestleMania Axxess events.[368] In 2017, WWE explored a deal to bring ICW programming onto the WWE Network[369] – ICW programming began airing on the WWE Network in 2020.

In 2018, WWE partnered with Germany's Westside Xtreme Wrestling (wXw).[370] In October 2018, WWE hosted German tryouts at the wXw Wrestling Academy.[371] In 2020, wXw programming began airing on the WWE Network.

In February 2023, WWE (specifically their NXT brand) launched a partnership with the Texas-based independent promotion Reality of Wrestling (ROW), which is owned by WWE Hall of Famer and NXT commentator Booker T.[372]

In December 2023, WWE launched a partnership with All Japan Pro Wrestling (AJPW).[373][374] In early 2024, WWE expanded their partnership with AJPW, with NXT wrestler Charlie Dempsey going to Japan to challenge for AJPW's Triple Crown Heavyweight Championship which marked the first match under the new collaboration.[375]

In 2024, WWE launched partnerships with Total Nonstop Action Wrestling (TNA),[376] Dream Star Fighting Marigold (Marigold),[377] Pro Wrestling Noah (NOAH), and Game Changer Wrestling (GCW).

Throughout the company's history, WWE has had past arrangements with independent companies from the contiguous United States (such as Ohio Valley Wrestling) and Puerto Rico (such as the International Wrestling Association) with the companies serving as developmental territories.[378]

The World Wrestling Federation had a drug-testing policy in place as early as 1987, initially run by an in-house administrator. In 1991, wrestlers were subjected to independent testing for anabolic steroids for the first time.[379] The independent testing was ceased in 1996, being deemed too expensive as the company was going through financial duress at the time as a result of their competitors, World Championship Wrestling, being so overwhelmingly more popular and hurting the federation's business.[380]

The Talent Wellness Program is a comprehensive drug, alcohol, and cardiac screening program initiated in February 2006, three months after the sudden death of one of their highest-profile and most popular talents, Eddie Guerrero, who died at 38-years-old.[381] The policy tests for recreational drug use and abuse of prescription medication, including anabolic steroids.[381] Under the guidelines of the policy, talent is also tested annually for pre-existing or developing cardiac issues. The drug testing is handled by Aegis Sciences Corporation; the cardiac evaluations are handled by New York Cardiology Associates P.C.[381] The Wellness Policy requires that all talent "under contract to WWE who regularly perform in-ring services as a professional sports entertainer" undergo testing; however, part-time competitors are exempt from testing.[382]

After the double-murder and suicide committed by one of its performers, Chris Benoit, with a possible link to steroid abuse encouraged by WWE, the United States House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform requested that WWE turn over any material regarding its talent wellness policy.[383]

In August 2007, WWE and its contracted performers defended the program in the wake of several busts of illegal pharmacy that linked WWE performers to steroid purchases even after the policy was put into place. Ten professional wrestlers were suspended for violating the Wellness Policy after reports emerged they were all customers of Signature Pharmacy in Orlando, Florida. According to a statement attributed to WWE attorney Jerry McDevitt, an eleventh wrestler was later added to the suspension list.[384][385][386]

On September 13, 2010, WWE updated their list of banned substances to include muscle relaxers.[387]

...with WWE surviving the merger as a direct, wholly owned subsidiary of [TKO Group Holdings]

He Inaugurated his promotion on January 7, 1953, ... .

McMahon formed a company he called the Capitol Wrestling Corporation, and presented his first regular wrestling show under the Capitol banner on January 7, 1953

On January 7, 1953, he put on the first-ever Capitol Wrestling Corporation event

From the time Vince, Sr. took over Capitol Wrestling Corporation from his father, the company continued to flourish in the northeastern United States.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)Speed was invoked but never defined (see the help page).{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)And then, in June, Jamal was released by WWE stemming from an incident at a night club, leaving Rosey on his own.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link){{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)Until Great Sasuke allegedly told Japanese reporters that he was going to win the WWE Light Heavyweight Championship and refuse to defend it in the USA and threatened to only defend it in Japan. The WWE immediately fired The Great Sasuke and moved on to put their new championship around the waist of the young Taka Michinoku. One would have to speculate that this hurt WWE's new relationship with Michinoku Pro