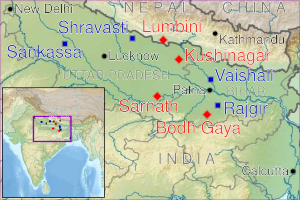

Siddhartha Gautama , [e] más comúnmente conocido como el Buda ('el despierto'), [4] [f] [g] fue un asceta errante y maestro religioso que vivió en el sur de Asia (las estribaciones del Himalaya del actual Nepal y la llanura oriental del Ganges del norte de la India ), durante el siglo VI o V a. C. [5] [6] [7] [c] y fundó el budismo . Según las leyendas budistas, nació en Lumbini , en lo que hoy es Nepal , [b] de padres reales del clan Shakya , pero renunció a su vida familiar para vivir como un asceta errante. [8] [h] Después de llevar una vida de mendicidad , ascetismo y meditación, alcanzó el nirvana en Bodh Gaya en lo que hoy es la India . Luego, el Buda vagó por la llanura indogangética inferior , enseñando y construyendo una orden monástica . La tradición budista sostiene que murió en Kushinagar y alcanzó el parinirvana ("liberación final de la existencia condicionada" [9] ). [i]

Según la tradición budista, el Buda enseñó un Camino Medio entre la indulgencia sensual y el ascetismo severo, [10] que conduce a la liberación de la ignorancia , el anhelo , el renacimiento y el sufrimiento . Sus enseñanzas fundamentales se resumen en las Cuatro Nobles Verdades y el Noble Óctuple Sendero , un entrenamiento de la mente que incluye el entrenamiento ético y la bondad hacia los demás , y prácticas meditativas como la restricción de los sentidos , la atención plena y dhyana (meditación propiamente dicha). Otro elemento clave de sus enseñanzas son los conceptos de los cinco skandhas y el origen dependiente , que describen cómo todos los dharmas (tanto los estados mentales como las "cosas" concretas) surgen y dejan de existir, dependiendo de otros dharmas , careciendo de existencia por sí mismos ( svabhava ).

Un par de siglos después de su muerte, llegó a ser conocido por el título de Buda , que significa 'Despierto' o 'Iluminado'. [11] Sus enseñanzas fueron compiladas por la comunidad budista en el Vinaya , sus códigos para la práctica monástica y el Sutta Piṭaka , una compilación de enseñanzas basadas en sus discursos. Estos se transmitieron en dialectos indoarios medios a través de una tradición oral . [12] [13] Las generaciones posteriores compusieron textos adicionales, como tratados sistemáticos conocidos como Abhidharma , biografías de Buda, colecciones de historias sobre sus vidas pasadas conocidas como cuentos Jataka y discursos adicionales, es decir, los sutras Mahayana . [14] [15]

El budismo se extendió más allá del subcontinente indio y evolucionó hacia una variedad de tradiciones y prácticas. Buda es reconocido en otras tradiciones religiosas, como el hinduismo , donde se lo considera un avatar de Visnú . Su legado no solo está encapsulado en instituciones religiosas, sino también en la iconografía y el arte inspirados en su vida y enseñanzas, que van desde símbolos anicónicos hasta representaciones icónicas en varios estilos culturales.

.jpg/440px-Tapa_Shotor_seated_Buddha_(Niche_V1).jpg)

Según Donald López Jr., "... se le solía conocer como Buda o Sakyamuni en China, Corea, Japón y el Tíbet, y como Buda Gotama o Samana Gotama ('el asceta Gotama') en Sri Lanka y el sudeste asiático". [16]

Buda , "el Despierto" o "el Iluminado", [11] [17] [f] es la forma masculina de budh (बुध्), "despertar, estar despierto, observar, prestar atención, atender, aprender, tomar conciencia de, saber, volver a ser consciente", [18] "despertar" [19] [20] " 'abrirse' (como lo hace una flor)", [20] "aquel que ha despertado del sueño profundo de la ignorancia y ha abierto su conciencia para abarcar todos los objetos del conocimiento". [20] No es un nombre personal, sino un título para aquellos que han alcanzado el bodhi (despertar, iluminación). [19] Buddhi , el poder de "formar y retener conceptos, razonar, discernir, juzgar, comprender, entender", [18] es la facultad que discierne la verdad ( satya ) de la falsedad.

El nombre de su clan era Gautama (Pali: Gotama). Su nombre de pila, "Siddhārtha" (la forma sánscrita; la traducción pali es "Siddhattha"; en tibetano es "Don grub"; en chino "Xidaduo"; en japonés "Shiddatta/Shittatta"; en coreano "Siltalta") significa "El que logra su objetivo". [21] El nombre del clan de Gautama significa "descendiente de Gotama", "Gotama" significa "el que tiene más luz", [22] y proviene del hecho de que los clanes Kshatriya adoptaron los nombres de sus sacerdotes domésticos. [23] [24]

Aunque el término "Buda" se utiliza en los Agamas y el Canon Pali, los registros escritos más antiguos que se conservan del término "Buda" son de mediados del siglo III a. C., cuando varios edictos de Ashoka (que reinó c. 269-232 a. C.) mencionan al Buda y al budismo. [25] [26] La inscripción del pilar de Lumbini de Ashoka conmemora la peregrinación del Emperador a Lumbini como el lugar de nacimiento del Buda, llamándolo el Buda Shakyamuni j] ( escritura Brahmi : 𑀩𑀼𑀥 𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀻 Bu-dha Sa-kya-mu-nī , "Buda, sabio de los Shakyas"). [27]

Śākyamuni, Sakyamuni o Shakyamuni ( sánscrito : शाक्यमुनि , [ɕaːkjɐmʊnɪ] ) significa "Sabio de los Shakyas ". [28]

Tathāgata ( en pali : [tɐˈtʰaːɡɐtɐ] ) es un término que Buda usó comúnmente para referirse a sí mismo o a otros Budas en el Canon Pali . [29] El significado exacto del término es desconocido, pero a menudo se piensa que significa "uno que se ha ido" ( tathā-gata ), "uno que ha venido" ( tathā-āgata ), o a veces "uno que no se ha ido" ( tathā-agata ). Esto se interpreta como que el Tathāgata está más allá de todo ir y venir, más allá de todos los fenómenos transitorios . [30] Un tathāgata es "inmensurable", "inescrutable", "difícil de comprender" y "no aprehendido". [31]

Una lista de otros epítetos se ve comúnmente junta en los textos canónicos y describe algunas de sus cualidades perfeccionadas: [32]

El Canon Pali también contiene otros numerosos títulos y epítetos para el Buda, incluyendo: Todo lo ve, Sabio que todo lo trasciende, Toro entre los hombres, El líder de la caravana, Disipador de la oscuridad, El Ojo, El primero de los aurigas, El primero de los que pueden cruzar, Rey del Dharma ( Dharmaraja ), Pariente del Sol, Ayudante del Mundo ( Lokanatha ), León ( Siha ), Señor del Dhamma, De excelente sabiduría ( Varapañña ), Radiante, Portador de la antorcha de la humanidad, Doctor y cirujano insuperable, Victorioso en la batalla y Portador del poder. [34] Otro epíteto, utilizado en inscripciones en todo el sur y sudeste de Asia, es Maha sramana , "gran sramana " (asceta, renunciante).

Basándose en evidencias filológicas , el indólogo y experto en pali Oskar von Hinüber afirma que algunos de los suttas pali han conservado topónimos, sintaxis y datos históricos muy arcaicos de épocas cercanas a la vida del Buda, incluido el Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta , que contiene un relato detallado de los últimos días del Buda. Hinüber propone una fecha de composición no posterior al 350-320 a. C. para este texto, lo que permitiría una "memoria histórica verdadera" de los acontecimientos ocurridos aproximadamente 60 años antes si se acepta la Cronología breve de la vida del Buda (pero también señala que un texto de este tipo fue concebido originalmente más como una hagiografía que como un registro histórico exacto de los acontecimientos). [35] [36]

John S. Strong considera que ciertos fragmentos biográficos en los textos canónicos conservados en pali, así como en chino, tibetano y sánscrito, son el material más antiguo. Entre ellos se incluyen textos como el «Discurso sobre la noble búsqueda» ( Ariyapariyesanā-sutta ) y sus paralelos en otros idiomas. [37]

No se encontraron registros escritos sobre Gautama de su vida o de los uno o dos siglos posteriores. [25] [26] [41] Pero desde mediados del siglo III a. C., varios edictos de Ashoka (que reinó c. 268 a 232 a. C.) mencionan al Buda y al budismo. [25] [26] En particular, la inscripción del pilar de Lumbini de Ashoka conmemora la peregrinación del Emperador a Lumbini como el lugar de nacimiento del Buda, llamándolo el Buda Shakyamuni ( escritura Brahmi : 𑀩𑀼𑀥 𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀻 Bu-dha Sa-kya-mu-nī , "Buda, sabio de los Shakyas"). [k] [38] [39] Otro de sus edictos ( Edicto Minor Rock No. 3 ) menciona los títulos de varios textos Dhamma (en el budismo, "dhamma" es otra palabra para "dharma"), [42] estableciendo la existencia de una tradición budista escrita al menos en la época de la era Maurya . Estos textos pueden ser los precursores del Canon Pāli . [43] [44] [l]

"Sakamuni" también se menciona en un relieve de Bharhut , fechado alrededor del año 100 a. C. , en relación con su iluminación y el árbol Bodhi , con la inscripción Bhagavato Sakamunino Bodho ("La iluminación del Bendito Sakamuni"). [45] [46]

Los manuscritos budistas más antiguos que se conservan son los textos budistas Gandhāran , encontrados en Gandhara (que corresponde al noroeste de Pakistán y el este de Afganistán modernos) y escritos en Gāndhārī , datan del siglo I a. C. al siglo III d. C. [47]

Las fuentes canónicas tempranas incluyen el Ariyapariyesana Sutta ( MN 26), el Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta ( DN 16), el Mahāsaccaka-sutta (MN 36), el Mahapadana Sutta (DN 14) y el Achariyabhuta Sutta (MN 123), que incluyen relatos selectivos que pueden ser más antiguos, pero no son biografías completas. Los cuentos Jātaka vuelven a contar vidas anteriores de Gautama como bodhisattva , y la primera colección de estos puede fecharse entre los textos budistas más antiguos. [48] Tanto el Mahāpadāna Sutta como el Achariyabhuta Sutta relatan eventos milagrosos que rodearon el nacimiento de Gautama, como el descenso del bodhisattva desde el Cielo Tuṣita al vientre de su madre.

Las fuentes que presentan un cuadro completo de la vida de Siddhārtha Gautama son una variedad de biografías tradicionales diferentes, y a veces contradictorias, de una fecha posterior. Estas incluyen el Buddhacarita , el Lalitavistara Sūtra , el Mahāvastu y el Nidānakathā . [49] De estos, el Buddhacarita [50] [51] [52] es la biografía completa más antigua, un poema épico escrito por el poeta Aśvaghoṣa en el siglo I d. C. [53] El Lalitavistara Sūtra es la siguiente biografía más antigua, una biografía Mahāyāna / Sarvāstivāda que data del siglo III d. C. [54]

El Mahāvastu de la tradición Mahāsāṃghika Lokottaravāda es otra biografía importante, compuesta de forma incremental hasta quizás el siglo IV d. C. [54] La biografía Dharmaguptaka del Buda es la más exhaustiva y se titula Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra , [55] y varias traducciones chinas de esta datan entre los siglos III y VI d. C. El Nidānakathā es de la tradición Theravada en Sri Lanka y fue compuesto en el siglo V por Buddhaghoṣa . [56]

Los estudiosos dudan en hacer afirmaciones sobre los hechos históricos de la vida de Buda. La mayoría de ellos aceptan que Buda vivió, enseñó y fundó una orden monástica durante el Mahajanapada y durante el reinado de Bimbisara (su amigo, protector y gobernante del imperio Magadha ); y murió durante los primeros años del reinado de Ajatashatru (quien fue el sucesor de Bimbisara), lo que lo convierte en un contemporáneo más joven de Mahavira , el tirthankara jainista . [57] [58]

Hay menos consenso sobre la veracidad de muchos detalles contenidos en las biografías tradicionales, [59] [60] ya que "los eruditos budistas [...] en su mayoría han dejado de intentar comprender a la persona histórica". [61] Las primeras versiones de textos biográficos budistas que tenemos ya contienen muchos elementos sobrenaturales, míticos o legendarios. En el siglo XIX, algunos eruditos simplemente los omitieron de sus relatos de la vida, de modo que "la imagen proyectada era la de un Buda que era un maestro racional y socrático, una gran persona tal vez, pero un ser humano más o menos común". Los eruditos más recientes tienden a ver a estos desmitificadores como remitificadores, "creando un Buda que les atraía, al elidir uno que no lo hacía". [62]

Las fechas del nacimiento y la muerte de Gautama son inciertas. En la tradición budista oriental de China, Vietnam, Corea y Japón, la fecha tradicional de la muerte de Buda fue el 949 a. C. [1] , pero según el sistema Ka-tan de la tradición Kalachakra , la muerte de Buda fue alrededor del 833 a. C. [63]

Los textos budistas presentan dos cronologías que se han utilizado para fechar la vida de Buda. [64] La "cronología larga", de las crónicas de Sri Lanka, afirma que Buda nació 298 años antes de la coronación de Asoka y murió 218 años antes de la coronación, por lo que su vida útil fue de unos 80 años. Según estas crónicas, Asoka fue coronado en el año 326 a. C., lo que da la vida útil de Buda entre el 624 y el 544 a. C., y son las fechas aceptadas en Sri Lanka y el sudeste asiático. [64] Alternativamente, la mayoría de los eruditos que también aceptan la cronología larga pero fechan la coronación de Asoka alrededor del 268 a. C. (basándose en la evidencia griega) sitúan la vida útil de Buda más tarde, entre el 566 y el 486 a. C. [64]

Sin embargo, la "cronología breve" de fuentes indias y sus traducciones al chino y al tibetano sitúan el nacimiento del Buda 180 años antes de la coronación de Asoka y su muerte 100 años antes de la coronación, es decir, unos 80 años. Según las fuentes griegas, la coronación de Asoka se produjo en el año 268 a. C., lo que sitúa la vida del Buda incluso más tarde, entre el 448 y el 368 a. C. [64]

La mayoría de los historiadores de principios del siglo XX utilizan las fechas más tempranas de 563-483 a. C., que difieren de la cronología larga basada en la evidencia griega en solo tres años. [1] [65] Más recientemente, hay intentos de poner su muerte a medio camino entre el 480 a. C. de la cronología larga y el 360 a. C. de la cronología corta, es decir, alrededor del 410 a. C. En un simposio sobre esta cuestión celebrado en 1988, [66] [67] [68] la mayoría de los que presentaron fechas dieron fechas dentro de los 20 años antes y después del 400 a. C. para la muerte de Buda. [1] [69] [c] [74] Sin embargo, estas cronologías alternativas no han sido aceptadas por todos los historiadores. [75] [76] [m]

La datación de Bimbisara y Ajatashatru también depende de la cronología larga o corta. En la cronología larga, Bimbisara reinó c. 558 - c. 492 a. C. , y murió 492 a. C., [81] [82] mientras que Ajatashatru reinó c. 492 - c. 460 a. C. [ 83] En la cronología corta Bimbisara reinó c. 400 a. C. , [84] [n] mientras que Ajatashatru murió entre c. 380 a. C. y 330 a. C. [84] Según el historiador KTS Sarao , un defensor de la cronología corta en la que la vida del Buda fue c.477-397 a. C., se puede estimar que Bimbisara reinó c.457-405 a. C., y Ajatashatru reinó c.405-373 a. C. [85]

Según la tradición budista, el Buda Shakyamuni era un Shakya , una etnia subhimalaya y un clan de la región nororiental del subcontinente indio. [b] [o] La comunidad Shakya estaba en la periferia, tanto geográfica como culturalmente, del subcontinente indio oriental en el siglo V a. C. [86] La comunidad, aunque se puede describir como una pequeña república, probablemente era una oligarquía , con su padre como jefe u oligarca electo. [86] Los Shakyas eran ampliamente considerados como no védicos (y, por lo tanto, impuros) en los textos brahmínicos ; sus orígenes siguen siendo especulativos y debatidos. [87] Bronkhorst denomina a esta cultura, que creció junto con Aryavarta sin verse afectada por el florecimiento del brahmanismo, como Gran Magadha . [88]

La tribu de origen de Buda, los Shakyas, parece haber tenido prácticas religiosas no védicas que persisten en el budismo, como la veneración de árboles y bosques sagrados, y el culto a los espíritus de los árboles (yakkhas) y a los seres serpiente (nagas). También parece que construyeron túmulos funerarios llamados stupas. [87] La veneración de los árboles sigue siendo importante en el budismo actual, en particular en la práctica de venerar los árboles Bodhi. Del mismo modo, los yakkas y los nagas han seguido siendo figuras importantes en las prácticas religiosas y la mitología budistas. [87]

La vida del Buda coincidió con el florecimiento de influyentes escuelas de pensamiento śramaṇa como el Ājīvika , el Cārvāka , el jainismo y el ajñana . [89] El Brahmajala Sutta registra sesenta y dos de esas escuelas de pensamiento. En este contexto, un śramaṇa se refiere a alguien que trabaja, se esfuerza o se esfuerza (por algún propósito superior o religioso). También fue la era de pensadores influyentes como Mahavira , [90] Pūraṇa Kassapa , Makkhali Gosāla , Ajita Kesakambalī , Pakudha Kaccāyana y Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta , como se registra en el Samaññaphala Sutta , con cuyos puntos de vista el Buda debe haber estado familiarizado. [91] [92] [p]

Śāriputra y Moggallāna , dos de los discípulos más destacados del Buda, fueron anteriormente los discípulos más destacados de Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, el escéptico. [94] El canon pali con frecuencia representa a Buda participando en debates con los seguidores de escuelas de pensamiento rivales. Hay evidencia filológica que sugiere que los dos maestros, Alara Kalama y Uddaka Rāmaputta , fueron figuras históricas y probablemente enseñaron a Buda dos formas diferentes de técnicas de meditación. [95] Por lo tanto, Buda fue solo uno de los muchos filósofos śramaṇa de esa época. [96] En una era donde la santidad de la persona se juzgaba por su nivel de ascetismo, [97] Buda fue un reformista dentro del movimiento śramaṇa, en lugar de un reaccionario contra el brahmanismo védico. [98]

Coningham y Young señalan que tanto los jainistas como los budistas usaban estupas, mientras que se pueden encontrar santuarios de árboles tanto en el budismo como en el hinduismo. [99]

El auge del budismo coincidió con la segunda urbanización , en la que se pobló la cuenca del Ganges y crecieron las ciudades, en las que prevaleció el igualitarismo . Según Thapar, las enseñanzas de Buda fueron "también una respuesta a los cambios históricos de la época, entre los que se encontraban el surgimiento del Estado y el crecimiento de los centros urbanos". [100] Aunque los mendicantes budistas renunciaron a la sociedad, vivían cerca de los pueblos y las ciudades, y dependían de laicos para recibir limosnas. [100]

Según Dyson, la cuenca del Ganges fue colonizada desde el noroeste y el sureste, así como desde el interior, "[uniéndose] en lo que ahora es Bihar (la ubicación de Pataliputra )". [101] La cuenca del Ganges estaba densamente arbolada, y la población creció cuando se deforestaron y cultivaron nuevas áreas. [101] La sociedad de la cuenca media del Ganges se encontraba en "la periferia de la influencia cultural aria", [102] y difería significativamente de la sociedad aria de la cuenca occidental del Ganges. [103] [104] Según Stein y Burton, "[l]os dioses del culto sacrificial brahmánico no fueron rechazados tanto como ignorados por los budistas y sus contemporáneos". [103] El jainismo y el budismo se opusieron a la estratificación social del brahmanismo, y su igualitarismo prevaleció en las ciudades de la cuenca media del Ganges. [102] Esto "permitió a los jainistas y budistas dedicarse al comercio más fácilmente que los brahmanes, quienes estaban obligados a seguir estrictas prohibiciones de casta". [105]

En los primeros textos budistas, los nikāyas y āgamas , el Buda no es representado como poseedor de omnisciencia ( sabbaññu ) [108] ni tampoco como un ser eterno y trascendente ( lokottara ). Según Bhikkhu Analayo , las ideas de la omnisciencia del Buda (junto con una creciente tendencia a deificarlo a él y a su biografía) se encuentran solo más tarde, en los sutras Mahayana y comentarios o textos Pali posteriores como el Mahāvastu . [108] En el Sandaka Sutta , el discípulo del Buda, Ananda, esboza un argumento contra las afirmaciones de los maestros que dicen que lo saben todo [109] mientras que en el Tevijjavacchagotta Sutta el propio Buda afirma que nunca ha afirmado ser omnisciente, sino que afirmó tener los "conocimientos superiores" ( abhijñā ). [110] El material biográfico más antiguo de los Pali Nikayas se centra en la vida del Buda como śramaṇa, su búsqueda de la iluminación bajo la dirección de varios maestros como Alara Kalama y su carrera de cuarenta y cinco años como maestro. [111]

Las biografías tradicionales de Gautama a menudo incluyen numerosos milagros, presagios y eventos sobrenaturales. El carácter del Buda en estas biografías tradicionales es a menudo el de un ser completamente trascendente (Skt. lokottara ) y perfecto que no está afectado por el mundo mundano. En el Mahāvastu , a lo largo de muchas vidas, se dice que Gautama desarrolló habilidades supramundanas que incluyen: un nacimiento sin dolor concebido sin relaciones sexuales; no necesitar dormir, comer, tomar medicamentos o bañarse, aunque lo hacía "en conformidad con el mundo"; omnisciencia y la capacidad de "suprimir el karma". [112] Como señaló Andrew Skilton, el Buda fue descrito a menudo como sobrehumano, incluidas descripciones de él con las 32 marcas mayores y 80 menores de un "gran hombre", y la idea de que el Buda podría vivir tanto como un eón si lo deseaba (ver DN 16). [113]

Los antiguos indios no se preocupaban en general por las cronologías, sino que se centraban más en la filosofía. Los textos budistas reflejan esta tendencia, proporcionando una imagen más clara de lo que Gautama pudo haber enseñado que de las fechas de los acontecimientos de su vida. Estos textos contienen descripciones de la cultura y la vida cotidiana de la antigua India que pueden corroborarse a partir de las escrituras jainistas , y hacen que la época de Buda sea el período más antiguo de la historia de la India del que existen relatos significativos. [114] La autora británica Karen Armstrong escribe que, aunque hay muy poca información que pueda considerarse históricamente sólida, podemos estar razonablemente seguros de que Siddhārtha Gautama existió como figura histórica. [115] Michael Carrithers va más allá, afirmando que el esquema más general de "nacimiento, madurez, renuncia, búsqueda, despertar y liberación, enseñanza, muerte" debe ser cierto. [116]

Biografías legendarias como la Pali Buddhavaṃsa y la sánscrita Jātakamālā describen la carrera del Buda (al que se hace referencia como " bodhisattva " antes de su despertar) como una carrera que abarca cientos de vidas antes de su último nacimiento como Gautama. Muchas de estas vidas anteriores están narradas en los Jatakas , que constan de 547 historias. [117] [118] El formato de un Jataka generalmente comienza contando una historia en el presente que luego se explica con una historia de la vida anterior de alguien. [119]

Además de imbuir el pasado prebudista con una profunda historia kármica, los Jatakas también sirven para explicar el camino del bodhisattva (el futuro Buda) hacia la Budeidad. [120] En biografías como la Buddhavaṃsa , este camino se describe como largo y arduo, y toma "cuatro eras incalculables" ( asamkheyyas ). [121]

En estas biografías legendarias, el bodhisattva pasa por muchos nacimientos diferentes (animales y humanos), se inspira en su encuentro con budas pasados y luego hace una serie de resoluciones o votos ( pranidhana ) para convertirse en un buda él mismo. Luego comienza a recibir predicciones de budas pasados. [122] Una de las más populares de estas historias es su encuentro con el buda Dipankara , quien le da al bodhisattva una predicción de la futura budeidad. [123]

Otro tema que se encuentra en el Comentario Pali Jataka ( Jātakaṭṭhakathā ) y el sánscrito Jātakamālā es cómo el futuro Buda tuvo que practicar varias "perfecciones" ( pāramitā ) para alcanzar la Budeidad. [124] Los Jatakas también describen a veces acciones negativas realizadas en vidas anteriores por el bodhisattva, lo que explica las dificultades que experimentó en su vida final como Gautama. [125]

Según la tradición budista, Gautama nació en Lumbini , [126] [128] hoy en Nepal, [q] y se crió en Kapilavastu . [129] [r] Se desconoce el sitio exacto del antiguo Kapilavastu. [131] Puede haber sido Piprahwa , Uttar Pradesh, en la actual India, [132] o Tilaurakot , en el actual Nepal. [133] Ambos lugares pertenecían al territorio Sakya y están ubicados a solo 24 kilómetros (15 millas) de distancia. [133] [b]

A mediados del siglo III a. C., el emperador Ashoka determinó que Lumbini era el lugar de nacimiento de Gautama y por ello instaló allí un pilar con la inscripción: "... aquí es donde nació el Buda, el sabio de los Śākyas ( Śākyamuni )." [134]

Según biografías posteriores como el Mahavastu y el Lalitavistara , su madre, Maya (Māyādevī), la esposa de Suddhodana, era una princesa de Devdaha , la antigua capital del Reino Koliya (lo que ahora es el Distrito Rupandehi de Nepal ). La leyenda dice que, la noche en que Siddhartha fue concebido, la reina Maya soñó que un elefante blanco con seis colmillos blancos entró en su costado derecho, [135] [136] y diez meses después [137] nació Siddhartha. Como era la tradición Shakya, cuando su madre, la reina Maya, quedó embarazada, dejó Kapilavastu para ir al reino de su padre para dar a luz.

Se dice que su hijo nació en el camino, en Lumbini, en un jardín bajo un árbol de sal . Las primeras fuentes budistas afirman que Buda nació en una familia aristocrática Kshatriya (Pali: khattiya ) llamada Gotama (Sánscrito: Gautama), que formaba parte de los Shakyas , una tribu de cultivadores de arroz que vivían cerca de la frontera moderna de India y Nepal. [138] [130] [139] [s] Su padre Śuddhodana era "un jefe electo del clan Shakya ", [7] cuya capital era Kapilavastu, y que luego fue anexada por el creciente Reino de Kosala durante la vida de Buda.

Los primeros textos budistas contienen muy poca información sobre el nacimiento y la juventud de Gotama Buddha. [141] [142] Biografías posteriores desarrollaron una narrativa dramática sobre la vida del joven Gotama como príncipe y sus problemas existenciales. [143] Representan a su padre Śuddhodana como un monarca hereditario de la Suryavansha (dinastía solar) de Ikṣvāku (Pāli: Okkāka). Esto es poco probable, ya que muchos erudhodana piensa que Śuddhodana era simplemente un aristócrata Shakya ( khattiya ), y que la república Shakya no era una monarquía hereditaria. [144] [145] [146] La forma de gobierno gaṇasaṅgha más igualitaria , como alternativa política a las monarquías indias, puede haber influido en el desarrollo de las sanghas budistas y jainistas śramánicas , [t] donde las monarquías tendían hacia el brahmanismo védico . [147]

El día del nacimiento, la iluminación y la muerte de Buda se celebra ampliamente en los países Theravada como Vesak y el día en que fue concebido como Poson . [148] El cumpleaños de Buda se llama Buda Purnima en Nepal, Bangladesh e India, ya que se cree que nació en un día de luna llena.

Según leyendas biográficas posteriores, durante las celebraciones del nacimiento, el vidente eremita Asita viajó desde su morada en la montaña, analizó al niño en busca de las "32 marcas de un gran hombre" y luego anunció que se convertiría en un gran rey ( chakravartin ) o en un gran líder religioso. [149] [150] Suddhodana celebró una ceremonia de nombramiento el quinto día e invitó a ocho eruditos brahmanes a leer el futuro. Todos dieron predicciones similares. [149] Kondañña , el más joven, y más tarde el primer arhat aparte de Buda, tenía fama de ser el único que predijo inequívocamente que Siddhartha se convertiría en Buda . [151]

Los primeros textos sugieren que Gautama no estaba familiarizado con las enseñanzas religiosas dominantes de su tiempo hasta que partió en su búsqueda religiosa, que se dice que estuvo motivada por la preocupación existencial por la condición humana. [152] Según los primeros textos budistas de varias escuelas y numerosos relatos postcanónicos , Gautama tenía una esposa, Yasodhara , y un hijo, llamado Rāhula . [153] Además de esto, el Buda en los primeros textos informa que "viví una vida malcriada, muy malcriada, monjes (en la casa de mis padres)". [154]

Las biografías legendarias como Lalitavistara también cuentan historias de la gran habilidad marcial del joven Gotama, que fue puesta a prueba en varias competiciones contra otros jóvenes shakyanos. [155]

Mientras que las fuentes más antiguas simplemente describen a Gotama buscando una meta espiritual más elevada y convirtiéndose en un asceta o śramaṇa después de desilusionarse con la vida laica, las biografías legendarias posteriores cuentan una historia dramática más elaborada sobre cómo se convirtió en mendicante. [143] [156]

Los primeros relatos de la búsqueda espiritual del Buda se encuentran en textos como el Pali Ariyapariyesanā-sutta ("El discurso sobre la noble búsqueda", MN 26) y su paralelo chino en MĀ 204. [157] Estos textos informan que lo que llevó a la renuncia de Gautama fue el pensamiento de que su vida estaba sujeta a la vejez, la enfermedad y la muerte y que podría haber algo mejor. [158] Los primeros textos también describen la explicación del Buda para convertirse en un sramana de la siguiente manera: "La vida familiar, este lugar de impureza, es estrecha; la vida samana es el aire libre. No es fácil para un jefe de familia llevar la vida santa perfecta, absolutamente pura y perfecta". [159] MN 26, MĀ 204, el Dharmaguptaka Vinaya y el Mahāvastu coinciden en que su madre y su padre se opusieron a su decisión y "lloraron con lágrimas en los ojos" cuando decidió irse. [160] [161]

Las biografías legendarias también cuentan la historia de cómo Gautama dejó su palacio para ver el mundo exterior por primera vez y cómo se sorprendió por su encuentro con el sufrimiento humano. [162] [163] Estas representan al padre de Gautama protegiéndolo de las enseñanzas religiosas y del conocimiento del sufrimiento humano , para que se convirtiera en un gran rey en lugar de un gran líder religioso. [164] En el Nidanakatha (siglo V d.C.), se dice que Gautama vio a un anciano. Cuando su auriga Chandaka le explicó que todas las personas envejecen, el príncipe realizó más viajes fuera del palacio. En estos se encontró con un hombre enfermo, un cadáver en descomposición y un asceta que lo inspiró. [165] [166] [167] Esta historia de las " cuatro visiones " parece estar adaptada de un relato anterior en el Digha Nikaya (DN 14.2) que en cambio describe la vida joven de un Buda anterior, Vipassi . [167]

Las biografías legendarias describen la salida de Gautama de su palacio de la siguiente manera. Poco después de ver las cuatro vistas, Gautama se despertó por la noche y vio a sus sirvientas acostadas en poses poco atractivas, parecidas a cadáveres, lo que lo sorprendió. [168] Por lo tanto, descubrió lo que más tarde comprendería más profundamente durante su iluminación : dukkha ("permanecer inestable", "insatisfacción" [169] [170] [171] [172] ) y el fin de dukkha . [173] Conmovido por todas las cosas que había experimentado, decidió abandonar el palacio en mitad de la noche contra la voluntad de su padre, para vivir la vida de un asceta errante. [165]

Acompañado por Chandaka y montado en su caballo Kanthaka , Gautama abandona el palacio, dejando atrás a su hijo Rahula y a Yaśodhara . [174] Viajó hasta el río Anomiya y se cortó el pelo. Dejando atrás a su sirviente y a su caballo, se adentró en el bosque y se puso allí la túnica de un monje , [175] aunque en otras versiones de la historia, recibió la túnica de una deidad de Brahma en Anomiya. [176]

Según las biografías legendarias, cuando el asceta Gautama fue por primera vez a Rajagaha (actual Rajgir ) a pedir limosna en las calles, el rey Bimbisara de Magadha se enteró de su búsqueda y le ofreció una parte de su reino. Gautama rechazó la oferta, pero prometió visitar su reino primero, cuando alcanzara la iluminación. [177] [178]

Majjhima Nikaya 4 menciona que Gautama vivió en "matorrales remotos de la jungla" durante sus años de esfuerzo espiritual y tuvo que superar el miedo que sentía mientras vivía en los bosques. [180] Los textos Nikaya narran que el asceta Gautama practicó con dos maestros de meditación yóguica . [181] [182] Según el Ariyapariyesanā-sutta (MN 26) y su paralelo chino en MĀ 204, después de haber dominado la enseñanza de Ārāḍa Kālāma ( Pali : Alara Kalama ), quien enseñó un logro de meditación llamado "la esfera de la nada", Ārāḍa le pidió que se convirtiera en un líder igualitario de su comunidad espiritual. [183] [184]

Gautama se sintió insatisfecho con la práctica porque "no conduce a la repulsión, al desapasionamiento, a la cesación, a la calma, al conocimiento, al despertar, al Nibbana", y continuó su camino para convertirse en estudiante de Udraka Rāmaputra ( Pali : Udaka Ramaputta ). [185] [186] Con él, alcanzó altos niveles de conciencia meditativa (llamada "La Esfera de Ni Percepción ni No Percepción") y nuevamente se le pidió que se uniera a su maestro. Pero, una vez más, no estuvo satisfecho por las mismas razones que antes, y siguió adelante. [187]

Según algunos sutras, después de dejar a sus maestros de meditación, Gautama practicó técnicas ascéticas. [188] [u] Las técnicas ascéticas descritas en los primeros textos incluyen una ingesta mínima de alimentos, diferentes formas de control de la respiración y un fuerte control mental. Los textos informan que se volvió tan demacrado que sus huesos se hicieron visibles a través de su piel. [190] El Mahāsaccaka-sutta y la mayoría de sus paralelos coinciden en que después de llevar el ascetismo a sus extremos, Gautama se dio cuenta de que esto no lo había ayudado a alcanzar el nirvana y que necesitaba recuperar fuerzas para perseguir su objetivo. [191] Una historia popular cuenta cómo aceptó leche y arroz con leche de una muchacha de la aldea llamada Sujata . [192]

Según el 身毛喜豎經, [v] su ruptura con el ascetismo llevó a sus cinco compañeros a abandonarlo, ya que creían que había abandonado su búsqueda y se había vuelto indisciplinado. En este punto, Gautama recordó una experiencia previa de dhyana ("meditación") que tuvo cuando era niño sentado bajo un árbol mientras su padre trabajaba. [191] Este recuerdo lo lleva a comprender que dhyana es el camino hacia la liberación , y los textos luego describen al Buda logrando los cuatro dhyanas, seguidos de los "tres conocimientos superiores" ( tevijja ), [w] culminando en la comprensión completa de las Cuatro Nobles Verdades , alcanzando así la liberación del samsara , el ciclo interminable de renacimientos. [194] [195] [196] [197] [x]

Según el Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (SN 56), [198] el Tathagata , el término que Gautama usa con más frecuencia para referirse a sí mismo, realizó "el Camino Medio ", un camino de moderación que se aleja de los extremos de la autocomplacencia y la automortificación, o el Noble Óctuple Sendero . [198] En siglos posteriores, Gautama llegó a ser conocido como el Buda o "El Despierto". El título indica que, a diferencia de la mayoría de las personas que están "dormidas", se entiende que un Buda ha "despertado" a la verdadera naturaleza de la realidad y ve el mundo "tal como es" ( yatha-bhutam ). [11] Un Buda ha alcanzado la liberación ( vimutti ), también llamada Nirvana, que se considera como la extinción de los "fuegos" del deseo, el odio y la ignorancia, que mantienen en marcha el ciclo del sufrimiento y el renacimiento. [199]

Tras su decisión de abandonar a sus maestros de meditación, MĀ 204 y otros textos tempranos paralelos informan que Gautama se sentó con la determinación de no levantarse hasta haber alcanzado el despertar completo ( sammā-sambodhi ); el Ariyapariyesanā-sutta no menciona el "despertar completo", sino solo que alcanzó el nirvana. [200] En la tradición budista, se dice que este evento ocurrió bajo un árbol pipal , conocido como "el árbol Bodhi ", en Bodh Gaya , Bihar. [201]

Según varios textos del Canon Pali, el Buda se sentó durante siete días bajo el árbol bodhi "sintiendo la dicha de la liberación". [202] Los textos Pali también informan que continuó meditando y contemplando varios aspectos del Dharma mientras vivía junto al río Nairañjanā , como el Origen Dependiente , las Cinco Facultades Espirituales y el sufrimiento ( dukkha ). [203]

Las biografías legendarias como Mahavastu , Nidanakatha y Lalitavistara describen un intento de Mara , el gobernante del reino del deseo, de impedir el nirvana de Buda. Lo hace enviando a sus hijas a seducir a Buda, afirmando su superioridad y atacándolo con ejércitos de monstruos. [204] Sin embargo, Buda no se inmuta e invoca a la tierra (o en algunas versiones de la leyenda, a la diosa de la tierra ) como testigo de su superioridad tocando el suelo antes de entrar en meditación. [205] También se describen otros milagros y eventos mágicos.

Según MN 26, inmediatamente después de su despertar, el Buda dudó sobre si debía o no enseñar el Dharma a otros. Le preocupaba que los humanos estuvieran dominados por la ignorancia, la codicia y el odio, por lo que les resultaría difícil reconocer el camino, que es "sutil, profundo y difícil de captar". Sin embargo, el dios Brahmā Sahampati lo convenció, argumentando que al menos algunos "con un poco de polvo en los ojos" lo entenderían. El Buda cedió y aceptó enseñar. Según Anālayo, el paralelo chino a MN 26, MĀ 204, no contiene esta historia, pero este evento sí aparece en otros textos paralelos, como en un discurso de Ekottarika-āgama , en el Catusparisat-sūtra y en el Lalitavistara . [200]

Según MN 26 y MĀ 204, después de decidir enseñar, el Buda inicialmente tenía la intención de visitar a sus antiguos maestros, Alara Kalama y Udaka Ramaputta , para enseñarles sus ideas, pero ellos ya habían muerto, por lo que decidió visitar a sus cinco antiguos compañeros. [206] Tanto MN 26 como MĀ 204 informan que en su camino a Vārānasī (Benarés), se encontró con otro vagabundo, un asceta Ājīvika llamado Upaka en MN 26. El Buda proclamó que había alcanzado el despertar completo, pero Upaka no estaba convencido y "tomó un camino diferente". [207]

MN 26 y MĀ 204 continúan con el Buda llegando al Parque de los Ciervos (Sarnath) ( Mrigadāva , también llamado Rishipatana , "sitio donde cayeron las cenizas de los ascetas") [208] cerca de Vārānasī, donde se encontró con el grupo de cinco ascetas y pudo convencerlos de que efectivamente había alcanzado el despertar completo. [209] Según MĀ 204 (pero no MN 26), así como el Theravāda Vinaya, un texto Ekottarika-āgama , el Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, el Mahīśāsaka Vinaya y el Mahāvastu , el Buda luego les enseñó el "primer sermón", también conocido como el "sermón de Benarés", [208] es decir, la enseñanza del "noble óctuple sendero como el camino medio alejado de los dos extremos de la indulgencia sensual y la automortificación". [209] El texto Pali relata que después del primer sermón, el asceta Koṇḍañña (Kaundinya) se convirtió en el primer arahant (ser liberado) y el primer bhikkhu o monástico budista. [210] El Buda luego continuó enseñando a los otros ascetas y formaron la primera saṅgha , la compañía de monjes budistas. [t]

Varias fuentes como el Mahāvastu, el Mahākhandhaka del Theravāda Vinaya y el Catusparisat-sūtra también mencionan que el Buda les enseñó su segundo discurso, sobre la característica del "no-ser" ( Anātmalakṣaṇa Sūtra ), en este momento [211] o cinco días después. [208] Después de escuchar este segundo sermón, los cuatro ascetas restantes también alcanzaron el estado de arahant. [208]

El Vinaya Theravāda y el Catusparisat-sūtra también hablan de la conversión de Yasa , un maestro de gremio local, y de sus amigos y familiares, que fueron algunos de los primeros laicos en convertirse y entrar en la comunidad budista. [212] [208] A esto le siguió la conversión de tres hermanos llamados Kassapa, que trajeron consigo a quinientos conversos que anteriormente habían sido «ascetas de pelo enmarañado», y cuya práctica espiritual estaba relacionada con los sacrificios de fuego. [213] [214] Según el Vinaya Theravāda, el Buda se detuvo entonces en la colina Gayasisa cerca de Gaya y pronunció su tercer discurso, el Ādittapariyāya Sutta (El discurso sobre el fuego), [215] en el que enseñó que todo en el mundo está inflamado por las pasiones y que solo aquellos que siguen el Óctuple Sendero pueden liberarse. [208]

Al final de la temporada de lluvias, cuando la comunidad del Buda había crecido hasta alrededor de sesenta monjes despertados, les ordenó que deambularan por su cuenta, enseñaran y ordenaran a personas en la comunidad, para el "bienestar y beneficio" del mundo. [216] [208]

Se dice que durante los 40 o 45 años restantes de su vida, Buda viajó por la llanura del Ganges , en lo que hoy es Uttar Pradesh , Bihar y el sur de Nepal, enseñando a una amplia gama de personas: desde nobles hasta sirvientes, ascetas y jefes de familia, asesinos como Angulimala y caníbales como Alavaka. [217] [156] [218] Según Schumann, los viajes del Buda abarcaron desde " Kosambi en el Yamuna (25 km al suroeste de Allahabad )", hasta Campa (40 km al este de Bhagalpur )" y desde "Kapilavatthu (95 km al noroeste de Gorakhpur ) hasta Uruvela (al sur de Gaya)". Esto cubre un área de 600 por 300 km. [219] Su sangha [t] disfrutó del patrocinio de los reyes de Kosala y Magadha y, por lo tanto, pasó mucho tiempo en sus respectivas capitales, Savatthi y Rajagaha . [219]

Aunque el idioma del Buda sigue siendo desconocido, es probable que enseñara en uno o más de una variedad de dialectos indoarios medios estrechamente relacionados , de los cuales el pali puede ser una estandarización.

La Sangha viajaba durante todo el año, excepto durante los cuatro meses de la temporada de lluvias de Vassa , cuando los ascetas de todas las religiones rara vez viajaban. Una de las razones era que era más difícil hacerlo sin causar daño a la flora y la vida animal. [220] La salud de los ascetas también podría haber sido una preocupación. [221] En esta época del año, la Sangha se retiraba a monasterios, parques públicos o bosques, donde la gente acudía a ellos.

El primer vassana se celebró en Varanasi cuando se formó la sangha. Según los textos pali, poco después de la formación de la sangha, el Buda viajó a Rajagaha , capital de Magadha , y se reunió con el rey Bimbisara , quien regaló un parque de bambú a la sangha. [222]

La sangha del Buda continuó creciendo durante sus viajes iniciales al norte de la India. Los primeros textos cuentan la historia de cómo los principales discípulos del Buda , Sāriputta y Mahāmoggallāna , quienes eran estudiantes del sramana escéptico Sañjaya Belaṭṭhiputta , fueron convertidos por Assaji . [223] [224] También cuentan cómo el hijo del Buda, Rahula , se unió a su padre como bhikkhu cuando el Buda visitó su antiguo hogar, Kapilavastu. [225] Con el tiempo, otros shakyanos se unieron a la orden como bhikkhus, como el primo del Buda, Ananda , Anuruddha , Upali el barbero, el medio hermano del Buda, Nanda , y Devadatta . [226] [227] Mientras tanto, el padre del Buda, Suddhodana, escuchó las enseñanzas de su hijo, se convirtió al budismo y entró en la corriente .

Los textos antiguos también mencionan a un importante discípulo laico, el comerciante Anāthapiṇḍika , que se convirtió en un firme partidario laico del Buda desde el principio. Se dice que donó el bosque de Jeta ( Jetavana ) a la sangha a un gran costo (el Vinaya Theravada habla de miles de monedas de oro). [228] [229]

La formación de una orden paralela de monjas ( bhikkhunī ) fue otra parte importante del crecimiento de la comunidad del Buda. Como se señala en el estudio comparativo de Anālayo sobre este tema, existen varias versiones de este evento descritas en los diferentes textos budistas primitivos. [y]

Según todas las versiones principales analizadas por Anālayo, Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī , la madrastra de Buda, es inicialmente rechazada por el Buda después de solicitar la ordenación para ella y algunas otras mujeres. Mahāprajāpatī y sus seguidores se afeitan el cabello, se visten con túnicas y comienzan a seguir al Buda en sus viajes. Finalmente, Ānanda convence al Buda de que le conceda la ordenación a Mahāprajāpatī si acepta ocho condiciones llamadas gurudharmas que se centran en la relación entre la nueva orden de monjas y los monjes. [231]

Según Anālayo, el único argumento común a todas las versiones que Ananda utiliza para convencer al Buda es que las mujeres tienen la misma capacidad para alcanzar todas las etapas del despertar. [232] Anālayo también señala que algunos eruditos modernos han cuestionado la autenticidad de los ocho gurudharmas en su forma actual debido a varias inconsistencias. Sostiene que la historicidad de las listas actuales de ocho es dudosa, pero que pueden haberse basado en mandatos anteriores del Buda. [233] [234]

Anālayo señala que varios pasajes indican que la razón por la que el Buda vaciló en ordenar mujeres fue el peligro que la vida de una sramana errante representaba para las mujeres que no estaban bajo la protección de sus familiares masculinos, como los peligros de agresión sexual y secuestro. Debido a esto, los mandatos del gurudharma pueden haber sido una manera de colocar "la orden recién fundada de monjas en una relación con sus contrapartes masculinas que se asemejara lo más posible a la protección que una mujer laica podía esperar de sus parientes masculinos". [235]

.jpg/440px-Indian_Museum_Sculpture_-_Ajatasattu_worships_the_Buddha_(9217704485).jpg)

Según JS Strong, después de los primeros 20 años de su carrera docente, el Buda parece haberse establecido lentamente en Sravasti, la capital del Reino de Kosala, pasando la mayor parte de sus últimos años en esta ciudad. [229]

A medida que la sangha [t] fue creciendo, surgió la necesidad de un conjunto estandarizado de reglas monásticas y el Buda parece haber desarrollado un conjunto de regulaciones para la sangha. Estas se conservan en varios textos llamados " Pratimoksa ", que eran recitados por la comunidad cada quince días. El Pratimoksa incluye preceptos éticos generales, así como reglas sobre los elementos esenciales de la vida monástica, como los cuencos y las túnicas. [236]

En sus últimos años, la fama del Buda creció y fue invitado a importantes eventos reales, como la inauguración de la nueva sala del consejo de los Shakyas (como se ve en MN 53) y la inauguración de un nuevo palacio por el príncipe Bodhi (como se representa en MN 85). [237] Los primeros textos también hablan de cómo durante la vejez del Buda, el reino de Magadha fue usurpado por un nuevo rey, Ajatashatru , que derrocó a su padre Bimbisara . Según el Samaññaphala Sutta, el nuevo rey habló con diferentes maestros ascéticos y finalmente se refugió en el Buda. [238] Sin embargo, las fuentes jainistas también afirman su lealtad, y es probable que apoyara a varios grupos religiosos, no solo exclusivamente a la sangha del Buda. [239]

A medida que el Buda continuó viajando y enseñando, también entró en contacto con miembros de otras sectas śrāmana. Hay evidencia de los textos tempranos de que el Buda se encontró con algunas de estas figuras y criticó sus doctrinas. El Samaññaphala Sutta identifica seis de esas sectas. [240]

Los textos antiguos también describen al anciano Buda sufriendo de dolor de espalda. Varios textos lo describen delegando enseñanzas a sus discípulos principales, ya que su cuerpo necesitaba ahora más descanso. [241] Sin embargo, el Buda continuó enseñando hasta bien entrada su vejez.

Uno de los acontecimientos más preocupantes durante la vejez del Buda fue el cisma de Devadatta . Las primeras fuentes hablan de cómo el primo del Buda, Devadatta, intentó asumir el liderazgo de la orden y luego abandonó la sangha con varios monjes budistas y formó una secta rival. Se dice que esta secta fue apoyada por el rey Ajatashatru. [242] [243] Los textos Pali describen a Devadatta conspirando para matar al Buda, pero todos estos planes fracasan. [244] Describen al Buda enviando a sus dos discípulos principales (Sariputta y Moggallana) a esta comunidad cismática para convencer a los monjes que se fueron con Devadatta de que regresaran. [245]

Todos los principales textos budistas vinaya tempranos describen a Devadatta como una figura divisiva que intentó dividir a la comunidad budista, pero no se ponen de acuerdo sobre en qué cuestiones discrepaba con el Buda. Los textos de Sthavira generalmente se centran en "cinco puntos" que se consideran prácticas ascéticas excesivas, mientras que el Mahāsaṅghika Vinaya habla de un desacuerdo más amplio, en el que Devadatta altera los discursos y la disciplina monástica. [246]

Casi al mismo tiempo que el cisma de Devadatta, también hubo una guerra entre el reino de Magadha de Ajatashatru y Kosala, liderado por un anciano rey Pasenadi. [247] Ajatashatru parece haber resultado victorioso, un giro de los acontecimientos que, según se informa, el Buda lamentó. [248]

.jpg/440px-040_Ananda_worships_Buddha_(25595318747).jpg)

La narración principal de los últimos días del Buda, su muerte y los acontecimientos posteriores a su muerte se encuentra en el Mahaparinibbana Sutta (DN 16) y sus diversos paralelos en sánscrito, chino y tibetano. [249] Según Anālayo, estos incluyen el Dirgha Agama 2 chino, "fragmentos sánscritos del Mahaparinirvanasutra" y "tres discursos preservados como traducciones individuales en chino". [250]

El sutta Mahaparinibbana describe el último año del Buda como un tiempo de guerra. Comienza con la decisión de Ajatashatru de declarar la guerra a la Liga Vajjika , lo que lo lleva a enviar un ministro para pedirle consejo al Buda. [251] El Buda responde diciendo que se puede esperar que los Vajjikas prosperen siempre que hagan siete cosas, y luego aplica estos siete principios a la Sangha budista, [t] mostrando que está preocupado por su bienestar futuro.

El Buda dice que la Sangha prosperará siempre que “celebrara asambleas regulares y frecuentes, se reuniera en armonía, no cambiara las reglas de entrenamiento, honrara a sus superiores que fueron ordenados antes que ellos, no cayeran presa de los deseos mundanos, permanecieran devotos a las ermitas del bosque y preservaran su atención personal”. Luego da una lista adicional de virtudes importantes que debe mantener la Sangha. [252]

Los primeros textos describen cómo los dos discípulos principales del Buda, Sariputta y Moggallana, murieron justo antes de la muerte del Buda. [253] El Mahaparinibbana describe al Buda como alguien que enfermó durante los últimos meses de su vida, pero que inicialmente se recuperó. Lo describe como alguien que afirma que no puede promover a nadie para que sea su sucesor. Cuando Ananda le pidió esto, el Mahaparinibbana registra su respuesta de la siguiente manera: [254]

Ananda, ¿por qué la Orden de monjes espera esto de mí? He enseñado el Dhamma, sin hacer distinción entre lo "interior" y lo "exterior": el Tathagata no tiene el "puño del maestro" (en el que se retienen ciertas verdades). Si hay alguien que piensa: "Me haré cargo de la Orden", o "la Orden está bajo mi liderazgo", esa persona tendría que hacer arreglos con respecto a la Orden. El Tathagata no piensa en esos términos. ¿Por qué debería el Tathagata hacer arreglos con respecto a la Orden? Ahora soy viejo, estoy agotado... He llegado al término de la vida, estoy cumpliendo ochenta años de edad. Así como un carro viejo se hace andar sujetándolo con correas, así el cuerpo del Tathagata se mantiene andando al ser vendado... Por lo tanto, Ananda, debéis vivir como islas para vosotros mismos, siendo vuestro propio refugio, sin buscar ningún otro refugio; con el Dhamma como una isla, con el Dhamma como su refugio, sin buscar ningún otro refugio... Aquellos monjes que en mi tiempo o después viven así, buscando una isla y un refugio en sí mismos y en el Dhamma y en ningún otro lugar, estos celosos son verdaderamente mis monjes y superarán la oscuridad (del renacimiento).

,_Gandhara,_3rd_or_4th_century_AD,_gray_schist_-_John_and_Mable_Ringling_Museum_of_Art_-_Sarasota,_FL_-_DSC00665.jpg/440px-Dying_Buddha_(Mahaparinirvana),_Gandhara,_3rd_or_4th_century_AD,_gray_schist_-_John_and_Mable_Ringling_Museum_of_Art_-_Sarasota,_FL_-_DSC00665.jpg)

Después de viajar y enseñar un poco más, el Buda comió su última comida, que había recibido como ofrenda de un herrero llamado Cunda . Al caer gravemente enfermo, el Buda le ordenó a su asistente Ānanda que convenciera a Cunda de que la comida que había comido en su casa no tenía nada que ver con su muerte y que su comida sería una fuente del mayor mérito, ya que proporcionaba la última comida para un Buda. [255] Bhikkhu Mettanando y Oskar von Hinüber sostienen que el Buda murió de un infarto mesentérico , un síntoma de vejez, en lugar de una intoxicación alimentaria. [256] [257]

El contenido preciso de la última comida de Buda no está claro debido a las diferentes tradiciones escriturales y a la ambigüedad en la traducción de ciertos términos significativos. La tradición Theravada generalmente cree que a Buda se le ofreció algún tipo de carne de cerdo, mientras que la tradición Mahayana cree que Buda consumió algún tipo de trufa u otro hongo. Esto puede reflejar las diferentes opiniones tradicionales sobre el vegetarianismo budista y los preceptos para monjes y monjas. [258] Los eruditos modernos también están en desacuerdo sobre este tema, argumentando tanto a favor de la carne de cerdo como de algún tipo de planta u hongo que a los cerdos les gusta comer. [z] Cualquiera sea el caso, ninguna de las fuentes que mencionan la última comida atribuye la enfermedad de Buda a la comida en sí. [259]

Según el sutta Mahaparinibbana, después de la comida con Cunda, el Buda y sus compañeros continuaron viajando hasta que estuvo demasiado débil para continuar y tuvo que detenerse en Kushinagar , donde Ānanda tenía un lugar de descanso preparado en un bosque de árboles Sala. [260] [261] Después de anunciar a la sangha en general que pronto moriría al Nirvana final, el Buda ordenó personalmente a un último novicio en la orden. Su nombre era Subhadda. [260] Luego repitió sus instrucciones finales a la sangha, que era que el Dhamma y el Vinaya serían sus maestros después de su muerte. Luego preguntó si alguien tenía alguna duda sobre la enseñanza, pero nadie la tenía. [262] Se dice que las últimas palabras del Buda fueron: “Todos los saṅkhāras se desintegran. Esfuérzate por alcanzar la meta con diligencia ( appamāda )” (Pali: 'vayadhammā saṅkhārā appamādena sampādethā'). [263] [264]

Luego entró en su meditación final y murió, alcanzando lo que se conoce como parinirvana (nirvana final; en lugar de que una persona renazca, "los cinco agregados de fenómenos físicos y mentales que constituyen un ser dejan de ocurrir" [265] ). El Mahaparinibbana informa que en su meditación final entró en los cuatro dhyanas consecutivamente, luego en los cuatro logros inmateriales y finalmente en la morada meditativa conocida como nirodha-samāpatti, antes de regresar al cuarto dhyana justo en el momento de la muerte. [266] [261]

Según el sutta Mahaparinibbana, los Mallians de Kushinagar pasaron los días posteriores a la muerte del Buda honrando su cuerpo con flores, música y aromas. [267] La sangha [t] esperó hasta que el eminente anciano Mahākassapa llegara para presentar sus respetos antes de cremar el cuerpo. [268]

El cuerpo del Buda fue luego incinerado y los restos, incluidos sus huesos, se conservaron como reliquias y se distribuyeron entre varios reinos del norte de la India como Magadha, Shakya y Koliya . [269] Estas reliquias se colocaron en monumentos o montículos llamados stupas , una práctica funeraria común en ese momento. Siglos más tarde serían exhumadas y consagradas por Ashoka en muchas nuevas stupas alrededor del reino Maurya . [270] [271] Muchas leyendas sobrenaturales rodean la historia de las supuestas reliquias, ya que acompañaron la propagación del budismo y dieron legitimidad a los gobernantes.

Según diversas fuentes budistas, el Primer Concilio Budista se celebró poco después de la muerte del Buda para recopilar, recitar y memorizar las enseñanzas. Mahākassapa fue elegido por la Sangha para ser el presidente del concilio. Sin embargo, la historicidad de los relatos tradicionales del primer concilio es cuestionada por los eruditos modernos. [272]

,_part_31_-_BL_Or._14915.jpg/440px-Fragmentary_Buddhist_text_-_Gandhara_birchbark_scrolls_(1st_C),_part_31_-_BL_Or._14915.jpg)

Una serie de enseñanzas y prácticas se consideran esenciales para el budismo, incluyendo: el samyojana (cadenas, grilletes o ataduras), es decir, los sankharas ("formaciones"), los kleshas ( estados mentales malsanos), incluyendo los tres venenos , y los āsavas ("influjo, cáncer"), que perpetúan saṃsāra , el ciclo repetido del devenir; las seis bases de los sentidos y los cinco agregados , que describen el proceso desde el contacto sensorial hasta la conciencia que conduce a esta esclavitud a saṃsāra ; el origen dependiente , que describe este proceso, y su reversión, en detalle; y el Camino Medio , con las Cuatro Nobles Verdades y el Noble Óctuple Sendero , que prescribe cómo se puede revertir esta esclavitud.

Según N. Ross Reat, los textos Theravada Pali y el Śālistamba Sūtra de la escuela Mahasamghika comparten estas enseñanzas y prácticas básicas. [273] Bhikkhu Analayo concluye que el Theravada Majjhima Nikaya y el Sarvastivada Madhyama Agama contienen en su mayoría las mismas doctrinas principales. [274] Asimismo, Richard Salomon ha escrito que las doctrinas que se encuentran en los Manuscritos de Gandharan son "consistentes con el budismo no Mahayana, que sobrevive hoy en la escuela Theravada de Sri Lanka y el sudeste asiático, pero que en la antigüedad estaba representada por dieciocho escuelas separadas". [275]

Todos los seres tienen samyojana (cadenas, grilletes o ataduras) profundamente arraigados , es decir, los sankharas (formaciones), kleshas (estados mentales malsanos), incluidos los tres venenos , y āsavas (influjo, cáncer), que perpetúan saṃsāra , el ciclo repetido de devenir y renacimiento . Según los suttas pali, el Buda afirmó que "este saṃsāra no tiene un comienzo descubrible. No se discierne un primer punto de los seres que vagan y deambulan obstaculizados por la ignorancia y encadenados por el anhelo". [ 276] En el sutta Dutiyalokadhammasutta (AN 8:6) el Buda explica cómo "ocho vientos mundanos" "mantienen al mundo girando [...] Ganancia y pérdida, fama y descrédito, alabanza y culpa, placer y dolor". Luego explica cómo la diferencia entre una persona noble ( arya ) y un mundano sin instrucción es que una persona noble reflexiona y comprende la impermanencia de estas condiciones. [277]

Este ciclo de devenir se caracteriza por el dukkha , [278] comúnmente denominado “sufrimiento”, aunque el dukkha se traduce más acertadamente como “insatisfacción” o “malestar”. Es la insatisfacción y el malestar que acompañan a una vida dictada por respuestas automáticas y un egoísmo habitual, [279] [280] y las insatisfacciones de esperar una felicidad duradera de cosas que son impermanentes, inestables y, por lo tanto, poco fiables. [281] El objetivo noble último debería ser la liberación de este ciclo. [282]

El samsara está dictado por el karma , que es una ley natural impersonal, similar a cómo ciertas semillas producen ciertas plantas y frutos. [283] El karma no es la única causa de las condiciones de uno, ya que el Buda enumeró varias causas físicas y ambientales junto con el karma. [284] La enseñanza del Buda sobre el karma difería de la de los jainistas y los brahmanes, en que, en su opinión, el karma es principalmente intención mental (en oposición a la acción principalmente física o los actos rituales). [279] Se informa que el Buda dijo: "Por karma me refiero a intención". [285] Richard Gombrich resume la visión del Buda sobre el karma de la siguiente manera: "todos los pensamientos, palabras y acciones derivan su valor moral, positivo o negativo, de la intención detrás de ellos". [286]

El āyatana (seis bases sensoriales) y los cinco skandhas (agregados) describen cómo el contacto sensorial conduce al apego y al dukkha . Las seis bases sensoriales son el ojo y la vista, el oído y el sonido, la nariz y el olfato, la lengua y el gusto, el cuerpo y el tacto, y la mente y los pensamientos. Juntos crean la información a partir de la cual creamos nuestro mundo o realidad, "el todo". Este proceso tiene lugar a través de los cinco skandhas, "agregados", "grupos", "montones", cinco grupos de procesos físicos y mentales, [287] [288] a saber, forma (o imagen material, impresión) ( rupa ), sensaciones (o sentimientos, recibidos de la forma) ( vedana ), percepciones ( samjna ), actividad mental o formaciones ( sankhara ), conciencia ( vijnana ). [289] [290] [291] Forman parte de otras enseñanzas y listas budistas, como la del origen dependiente, y explican cómo la información sensorial conduce en última instancia a la esclavitud del samsara por las impurezas mentales.

En los textos antiguos, el proceso de surgimiento de dukkha se explica a través de la enseñanza del origen dependiente , [279] que dice que todo lo que existe u ocurre depende de factores condicionantes. [292] La formulación más básica del origen dependiente se da en los textos antiguos como: 'Siendo así, esto sucede' (Pali: evam sati idam hoti ). [293] Esto puede interpretarse como que ciertos fenómenos solo surgen cuando hay otros fenómenos presentes, por lo que su surgimiento es "dependiente" de otros fenómenos. [293]

El filósofo Mark Siderits ha esbozado la idea básica de la enseñanza del Buda sobre el Origen Dependiente de dukkha de la siguiente manera:

Dada la existencia de un conjunto de elementos psicofísicos (las partes que componen un ser sintiente) en pleno funcionamiento, la ignorancia sobre las tres características de la existencia sintiente —sufrimiento, impermanencia y no-yo— conducirá, en el curso de las interacciones normales con el entorno, a la apropiación (la identificación de ciertos elementos como «yo» y «mío»). Esto conduce a su vez a la formación de apegos, en forma de deseo y aversión, y al fortalecimiento de la ignorancia sobre la verdadera naturaleza de la existencia sintiente. Estos aseguran futuros renacimientos y, por lo tanto, futuras instancias de vejez, enfermedad y muerte, en un ciclo potencialmente interminable. [279]

En numerosos textos tempranos, este principio básico se amplía con una lista de fenómenos que se dice que son condicionalmente dependientes, [294] [aa] como resultado de elaboraciones posteriores, [295] [296] [297] [ab] incluyendo las cosmogenias védicas como base para los primeros cuatro enlaces. [298] [299] [300] [301] [302] [303] Según Boisvert, nidana 3-10 se correlacionan con los cinco skandhas. [304] Según Richard Gombrich, la lista de doce partes es una combinación de dos listas anteriores, la segunda lista comienza con tanha , "sed", la causa del sufrimiento como se describe en la segunda noble verdad". [305] Según Gombrich, las dos listas se combinaron, lo que resultó en contradicciones en su versión inversa. [305] [ac]

The Buddha saw his analysis of dependent origination as a "Middle Way" between "eternalism" (sassatavada, the idea that some essence exists eternally) and "annihilationism" (ucchedavada, the idea that we go completely out of existence at death).[279][293] in this view, persons are just a causal series of impermanent psycho-physical elements,[279] which are anatta, without an independent or permanent self.[292] The Buddha instead held that all things in the world of our experience are transient and that there is no unchanging part to a person.[306] According to Richard Gombrich, the Buddha's position is simply that "everything is process".[307]

The Buddha's arguments against an unchanging self rely on the scheme of the five skandhas, as can be seen in the Pali Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta (and its parallels in Gandhari and Chinese).[308][309][310] In the early texts the Buddha teaches that all five aggregates, including consciousness (viññana, which was held by Brahmins to be eternal), arise due to dependent origination.[311] Since they are all impermanent, one cannot regard any of the psycho-physical processes as an unchanging self.[312][279] Even mental processes such as consciousness and will (cetana) are seen as being dependently originated and impermanent and thus do not qualify as a self (atman).[279]

The Buddha saw the belief in a self as arising from our grasping at and identifying with the various changing phenomena, as well as from ignorance about how things really are.[313] Furthermore, the Buddha held that we experience suffering because we hold on to erroneous self views.[314][315] As Rupert Gethin explains, for the Buddha, a person is

... a complex flow of physical and mental phenomena, but peel away these phenomena and look behind them and one just does not find a constant self that one can call one's own. My sense of self is both logically and emotionally just a label that I impose on these physical and mental phenomena in consequence of their connectedness.[316]

Due to this view (termed ), the Buddha's teaching was opposed to all soul theories of his time, including the Jain theory of a "jiva" ("life monad") and the Brahmanical theories of atman (Pali: atta) and purusha. All of these theories held that there was an eternal unchanging essence to a person, which was separate from all changing experiences,[317] and which transmigrated from life to life.[318][319][279] The Buddha's anti-essentialist view still includes an understanding of continuity through rebirth, it is just the rebirth of a process (karma), not an essence like the atman.[320]

.jpg/440px-20160124_Sri_Lanka_3769_Polonnaruwa_sRGB_(25144212713).jpg)

The Buddha taught a path (marga) of training to undo the samyojana, kleshas and āsavas and attain vimutti (liberation).[279][321] This path taught by the Buddha is depicted in the early texts (most famously in the Pali Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta and its numerous parallel texts) as a "Middle Way" between sensual indulgence on one hand and mortification of the body on the other.[322]

A common presentation of the core structure of Buddha's teaching found in the early texts is that of the Four Noble Truths,[323] which refers to the Noble Eightfold Path.[324][ad] According to Gethin, another common summary of the path to awakening wisely used in the early texts is "abandoning the hindrances, practice of the four establishments of mindfulness and development of the awakening factors".[326]

According to Rupert Gethin, in the Nikayas and Agamas, the Buddha's path is mainly presented in a cumulative and gradual "step by step" process, such as that outlined in the Samaññaphala Sutta.[327][ae] Other early texts like the Upanisa sutta (SN 12.23), present the path as reversions of the process of Dependent Origination.[332][af]

Bhāvanā, cultivation of wholesome states, is central to the Buddha's path. Common practices to this goal, which are shared by most of these early presentations of the path, include sila (ethical training), restraint of the senses (indriyasamvara), sati (mindfulness) and sampajañña (clear awareness), and the practice of dhyana, the cumulative development of wholesome states[328] leading to a "state of perfect equanimity and awareness (upekkhā-sati-parisuddhi)".[334] Dhyana is preceded and supported by various aspects of the path such as sense restraint[335] and mindfulness, which is elaborated in the satipatthana-scheme, as taught in the Pali Satipatthana Sutta and the sixteen elements of Anapanasati, as taught in the Anapanasati Sutta.[ag]

.jpg/440px-Borobudur_-_Lalitavistara_-_071_W,_The_Bodhisattva_meets_with_Arada_Kalama_(11249495494).jpg)

In various texts, the Buddha is depicted as having studied under two named teachers, Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta. According to Alexander Wynne, these were yogis who taught doctrines and practices similar to those in the Upanishads.[336] According to Johannes Bronkhorst, the "meditation without breath and reduced intake of food" which the Buddha practiced before his awakening are forms of asceticism which are similar to Jain practices.[337]

According to Richard Gombrich, the Buddha's teachings on Karma and Rebirth are a development of pre-Buddhist themes that can be found in Jain and Brahmanical sources, like the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.[338] Likewise, samsara, the idea that we are trapped in cycles of rebirth and that we should seek liberation from them through non-harming (ahimsa) and spiritual practices, pre-dates the Buddha and was likely taught in early Jainism.[339] According to K.R. Norman, the Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence[ah] may also reflect Upanishadic or other influences .[340] The Buddhist practice called Brahma-vihara may have also originated from a Brahmanic term;[341] but its usage may have been common in the sramana traditions.[342]

One method to obtain information on the oldest core of Buddhism is to compare the oldest versions of the Pali Canon and other texts, such as the surviving portions of Sarvastivada, Mulasarvastivada, Mahisasaka, Dharmaguptaka,[343][344] and the Chinese Agamas.[345][346] The reliability of these sources, and the possibility of drawing out a core of oldest teachings, is a matter of dispute.[342][347][348][349] According to Lambert Schmithausen, there are three positions held by modern scholars of Buddhism with regard to the authenticity of the teachings contained in the Nikayas:[350]

Scholars such as Richard Gombrich, Akira Hirakawa, Alexander Wynne and A.K. Warder hold that these Early Buddhist Texts contain material that could possibly be traced to the Buddha.[349][355][158] Richard Gombrich argues that since the content of the earliest texts "presents such originality, intelligence, grandeur and—most relevantly—coherence...it is hard to see it as a composite work." Thus he concludes they are "the work of one genius".[356] Peter Harvey also agrees that "much" of the Pali Canon "must derive from his [the Buddha's] teachings".[357] Likewise, A. K. Warder has written that "there is no evidence to suggest that it [the shared teaching of the early schools] was formulated by anyone other than the Buddha and his immediate followers."[351] According to Alexander Wynne, "the internal evidence of the early Buddhist literature proves its historical authenticity."[358]

Other scholars of Buddhist studies have disagreed with the mostly positive view that the early Buddhist texts reflect the teachings of the historical Buddha, arguing that some teachings contained in the early texts are the authentic teachings of the Buddha, but not others. According to Tilmann Vetter, inconsistencies remain, and other methods must be applied to resolve those inconsistencies.[343][al] According to Tilmann Vetter, the earliest core of the Buddhist teachings is the meditative practice of dhyāna,[361][am] but "liberating insight" became an essential feature of the Buddhist tradition only at a later date.

He posits that the Fourth Noble Truths, the Eightfold path and Dependent Origination, which are commonly seen as essential to Buddhism, are later formulations which form part of the explanatory framework of this "liberating insight".[363] Lambert Schmithausen similarly argues that the mention of the four noble truths as constituting "liberating insight", which is attained after mastering the four dhyānas, is a later addition.[359] Johannes Bronkhorst also argues that the four truths may not have been formulated in earliest Buddhism, and did not serve in earliest Buddhism as a description of "liberating insight".[364]

Edward Conze argued that the attempts of European scholars to reconstruct the original teachings of the Buddha were "all mere guesswork".[365]

The early Buddhist texts depict the Buddha as promoting the life of a homeless and celibate "sramana", or mendicant, as the ideal way of life for the practice of the path.[366] He taught that mendicants or "beggars" (bhikkhus) were supposed to give up all possessions and to own just a begging bowl and three robes.[367] As part of the Buddha's monastic discipline, they were also supposed to rely on the wider lay community for the basic necessities (mainly food, clothing, and lodging).[368]

The Buddha's teachings on monastic discipline were preserved in the various Vinaya collections of the different early schools.[367]

Buddhist monastics, which included both monks and nuns, were supposed to beg for their food, were not allowed to store up food or eat after noon and they were not allowed to use gold, silver or any valuables.[369][370]

.jpg/440px-Indian_Museum_Sculpture_-_Buddha_meets_a_Brahmin_(9218121775).jpg)

According to Bronkhorst, "the bearers of [the Brahmanical] tradition, the Brahmins, did not occupy a dominant position in the area in which the Buddha preached his message."[104] Nevertheless, the Buddha was acquainted with Brahmanism, and in the early Buddhist Texts, the Buddha references Brahmanical devices. For example, in Samyutta Nikaya 111, Majjhima Nikaya 92 and Vinaya i 246 of the Pali Canon, the Buddha praises the Agnihotra as the foremost sacrifice and the Gayatri mantra as the foremost meter.[an] In general, the Buddha critiques the Brahmanical religion and social system on certain key points.

The Brahmin caste held that the Vedas were eternal revealed (sruti) texts. The Buddha, on the other hand, did not accept that these texts had any divine authority or value.[372]

The Buddha also did not see the Brahmanical rites and practices as useful for spiritual advancement. For example, in the Udāna, the Buddha points out that ritual bathing does not lead to purity: only "truth and morality" lead to purity.[ao] He especially critiqued animal sacrifice as taught in Vedas.[372] The Buddha contrasted his teachings, which were taught openly to all people, with that of the Brahmins', who kept their mantras secret.[ap]

The Buddha also critiqued the Brahmins' claims of superior birth and the idea that different castes and bloodlines were inherently pure or impure, noble or ignoble.[372]

In the Vasettha sutta the Buddha argues that the main difference among humans is not birth but their actions and occupations.[374] According to the Buddha, one is a "Brahmin" (i.e. divine, like Brahma) only to the extent that one has cultivated virtue.[aq] Because of this the early texts report that he proclaimed: "Not by birth one is a Brahman, not by birth one is a non-Brahman; – by moral action one is a Brahman"[372]

The Aggañña Sutta explains all classes or varnas can be good or bad and gives a sociological explanation for how they arose, against the Brahmanical idea that they are divinely ordained.[375] According to Kancha Ilaiah, the Buddha posed the first contract theory of society.[376] The Buddha's teaching then is a single universal moral law, one Dharma valid for everybody, which is opposed to the Brahmanic ethic founded on "one's own duty" (svadharma) which depends on caste.[372] Because of this, all castes including untouchables were welcome in the Buddhist order and when someone joined, they renounced all caste affiliation.[377][378]

The early texts depict the Buddha as giving a deflationary account of the importance of politics to human life. Politics is inevitable and is probably even necessary and helpful, but it is also a tremendous waste of time and effort, as well as being a prime temptation to allow ego to run rampant. Buddhist political theory denies that people have a moral duty to engage in politics except to a very minimal degree (pay the taxes, obey the laws, maybe vote in the elections), and it actively portrays engagement in politics and the pursuit of enlightenment as being conflicting paths in life.[379]

In the Aggañña Sutta, the Buddha teaches a history of how monarchy arose which according to Matthew J. Moore is "closely analogous to a social contract". The Aggañña Sutta also provides a social explanation of how different classes arose, in contrast to the Vedic views on social caste.[380]

Other early texts like the Cakkavatti-Sīhanāda Sutta and the Mahāsudassana Sutta focus on the figure of the righteous wheel turning leader (Cakkavatti). This ideal leader is one who promotes Dharma through his governance. He can only achieve his status through moral purity and must promote morality and Dharma to maintain his position. According to the Cakkavatti-Sīhanāda Sutta, the key duties of a Cakkavatti are: "establish guard, ward, and protection according to Dhamma for your own household, your troops, your nobles, and vassals, for Brahmins and householders, town and country folk, ascetics and Brahmins, for beasts and birds. let no crime prevail in your kingdom, and to those who are in need, give property."[380] The sutta explains the injunction to give to the needy by telling how a line of wheel-turning monarchs falls because they fail to give to the needy, and thus the kingdom falls into infighting as poverty increases, which then leads to stealing and violence.[ar]

In the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta, the Buddha outlines several principles that he promoted among the Vajjika tribal federation, which had a quasi-republican form of government. He taught them to "hold regular and frequent assemblies", live in harmony and maintain their traditions. The Buddha then goes on to promote a similar kind of republican style of government among the Buddhist Sangha, where all monks had equal rights to attend open meetings and there would be no single leader, since The Buddha also chose not to appoint one.[380] Some scholars have argued that this fact signals that the Buddha preferred a republican form of government, while others disagree with this position.[380]

As noted by Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Buddha as depicted in the Pali suttas does not exclusively teach a world-transcending goal, but also teaches laypersons how to achieve worldly happiness (sukha).[381]

According to Bodhi, the "most comprehensive" of the suttas that focus on how to live as a layperson is the Sigālovāda Sutta (DN 31). This sutta outlines how a layperson behaves towards six basic social relationships: "parents and children, teacher and pupils, husband and wife, friend and friend, employer and workers, lay follower and religious guides".[382] This Pali text also has parallels in Chinese and in Sanskrit fragments.[383][384]

In another sutta (Dīghajāṇu Sutta, AN 8.54) the Buddha teaches two types of happiness. First, there is the happiness visible in this very life. The Buddha states that four things lead to this happiness: "The accomplishment of persistent effort, the accomplishment of protection, good friendship, and balanced living."[385] Similarly, in several other suttas, the Buddha teaches on how to improve family relationships, particularly on the importance of filial love and gratitude as well as marital well-being.[386]

Regarding the happiness of the next life, the Buddha (in the Dīghajāṇu Sutta) states that the virtues which lead to a good rebirth are: faith (in the Buddha and the teachings), moral discipline, especially keeping the five precepts, generosity, and wisdom (knowledge of the arising and passing of things).[387]