La Segunda Guerra Bóer ( afrikaans : Tweede Vryheidsoorlog , lit. ' Segunda Guerra de la Libertad ' , 11 de octubre de 1899 - 31 de mayo de 1902), también conocida como Guerra de los Bóers , Guerra de Transvaal , [8] Guerra Anglo-Bóer o Guerra Sudafricana , fue un conflicto librado entre el Imperio Británico y las dos repúblicas Bóer (la República Sudafricana y el Estado Libre de Orange ) por la influencia del Imperio en el sur de África .

La fiebre del oro de Witwatersrand provocó una gran afluencia de " extranjeros " a la República Sudafricana, en su mayoría británicos de la Colonia del Cabo . No se les permitía votar y se los consideraba "visitantes no deseados", por lo que protestaron ante las autoridades británicas en el Cabo. Las negociaciones fracasaron en la Conferencia de Bloemfontein en junio de 1899. El conflicto estalló en octubre cuando los irregulares y la milicia bóer atacaron los asentamientos coloniales británicos. Los bóeres sitiaron Ladysmith , Kimberley y Mafeking y obtuvieron victorias en Colenso , Magersfontein y Stormberg . Un número cada vez mayor de soldados del ejército británico fueron llevados a Sudáfrica y lanzaron ataques infructuosos contra los bóeres.

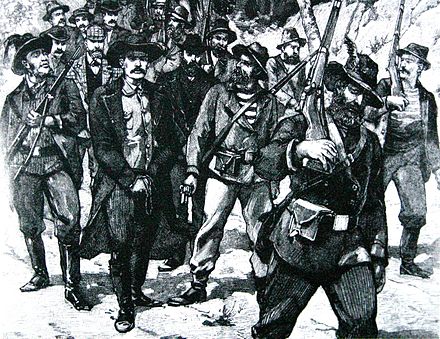

Sin embargo, la suerte británica cambió cuando su comandante, el general Redvers Buller , fue reemplazado por Lord Roberts y Lord Kitchener , quienes aliviaron las ciudades asediadas e invadieron las repúblicas bóer a principios de 1900 al frente de una fuerza expedicionaria de 180.000 hombres. Los bóeres, conscientes de que no podían resistir una fuerza tan grande, se abstuvieron de luchar en batallas campales , lo que permitió a los británicos ocupar ambas repúblicas y sus capitales, Pretoria y Bloemfontein . [9] [10] [11] Los políticos bóer, incluido el presidente de la República Sudafricana Paul Kruger , huyeron o se escondieron; el Imperio británico anexó oficialmente las dos repúblicas en 1900. En Gran Bretaña, el ministerio conservador dirigido por Lord Salisbury intentó capitalizar los éxitos militares británicos convocando una elección general anticipada , apodada por los observadores contemporáneos como una " elección caqui ". Sin embargo, los combatientes bóeres se refugiaron en las colinas y lanzaron una campaña de guerrillas, conocida como bittereinders . Liderados por generales como Louis Botha , Jan Smuts , Christiaan de Wet y Koos de la Rey , los guerrilleros bóeres utilizaron ataques relámpago y emboscadas contra los británicos durante dos años. [12] [13]

La campaña de guerrillas resultó difícil de derrotar para los británicos, debido a la falta de familiaridad con las tácticas de guerrilla y al amplio apoyo a las guerrillas entre los civiles. En respuesta a los fracasos en derrotar a las guerrillas, el alto mando británico ordenó políticas de tierra arrasada como parte de una campaña de contrainsurgencia a gran escala y de múltiples frentes ; se construyó una red de redes , fortines , puntos fuertes y cercas de alambre de púas , que virtualmente dividió las repúblicas ocupadas. Más de 100.000 civiles bóeres, en su mayoría mujeres y niños, fueron reubicados a la fuerza en campos de concentración , donde murieron 26.000, principalmente por hambre y enfermedad. Los africanos negros fueron internados en campos de concentración para evitar que abastecieran a los bóers; murieron 20.000. [14] La infantería montada británica fue desplegada para rastrear a las guerrillas, lo que provocó escaramuzas a pequeña escala . Pocos combatientes de ambos bandos murieron en acción , y la mayoría de las bajas murieron por enfermedad. Kitchener ofreció generosas condiciones de rendición a los líderes bóer restantes para poner fin al conflicto. Ansiosos por asegurar que sus compañeros bóers fueran liberados de los campos, la mayoría de los comandantes bóer aceptaron los términos británicos en el Tratado de Vereeniging , rindiéndose en mayo de 1902. [15] [16] Las antiguas repúblicas se transformaron en las colonias británicas de Transvaal y el río Orange , y en 1910 se fusionaron con las colonias de Natal y el Cabo para formar la Unión de Sudáfrica , un dominio autónomo dentro del Imperio Británico. [17]

Los esfuerzos expedicionarios británicos fueron ayudados significativamente por fuerzas coloniales de la Colonia del Cabo, Natal, Rodesia , [18] y muchos voluntarios del Imperio Británico en todo el mundo, particularmente Australia , Canadá , India y Nueva Zelanda . Los reclutas africanos negros contribuyeron cada vez más al esfuerzo bélico británico. La opinión pública internacional simpatizaba con los bóers y era hostil a los británicos . Incluso dentro del Reino Unido, existía una oposición significativa a la guerra . Como resultado, la causa bóer atrajo a miles de voluntarios de países neutrales , incluido el Imperio alemán, Estados Unidos, Rusia e incluso algunas partes del Imperio Británico como Australia e Irlanda. [19] Algunos consideran que la guerra fue el comienzo del cuestionamiento de la apariencia de dominio global impenetrable del Imperio Británico, debido a la sorprendente duración de la guerra y las pérdidas imprevistas sufridas por los británicos. [20] En enero de 1901 se abrió un juicio por crímenes de guerra británicos cometidos durante la guerra, incluidos los asesinatos de civiles y prisioneros.

La guerra tuvo tres fases. En la primera, los bóers lanzaron ataques preventivos en territorio británico en Natal y la Colonia del Cabo , sitiando las guarniciones británicas de Ladysmith , Mafeking y Kimberley . Luego, los bóers obtuvieron una serie de victorias tácticas en Stormberg , Magersfontein , Colenso y Spion Kop .

En la segunda fase, después de que el número de tropas británicas aumentara considerablemente bajo el mando de Lord Roberts , los británicos lanzaron otra ofensiva en 1900 para aliviar los asedios, esta vez logrando éxito. Después de que Natal y la Colonia del Cabo estuvieran seguras, el ejército británico pudo invadir el Transvaal, y la capital de la república, Pretoria , fue finalmente capturada en junio de 1900.

En la tercera y última fase, que comenzó en marzo de 1900 y duró dos años más, los bóers llevaron a cabo una dura guerra de guerrillas, atacando columnas de tropas británicas, emplazamientos telegráficos, ferrocarriles y depósitos de almacenamiento. Para negar suministros a las guerrillas bóeres, los británicos, ahora bajo el liderazgo de Lord Kitchener , adoptaron una política de tierra quemada . Despejaron vastas áreas, destruyeron granjas bóeres y trasladaron a los civiles a campos de concentración. [21] : 439–495

Algunos sectores de la prensa y el gobierno británicos esperaban que la campaña terminara en unos meses, y la prolongada guerra gradualmente se volvió menos popular, especialmente después de las revelaciones sobre las condiciones en los campos de concentración (donde hasta 26.000 mujeres y niños afrikáneres murieron de enfermedades y desnutrición). Las fuerzas bóer finalmente se rindieron el sábado 31 de mayo de 1902, con 54 de los 60 delegados del Transvaal y el Estado Libre de Orange votando para aceptar los términos del tratado de paz. [22] : 97 Esto se conoció como el Tratado de Vereeniging , y bajo sus disposiciones, las dos repúblicas fueron absorbidas por el Imperio Británico, con la promesa de autogobierno en el futuro. Esta promesa se cumplió con la creación de la Unión de Sudáfrica en 1910.

La guerra tuvo un efecto duradero en la región y en la política interna británica. Para Gran Bretaña, la Segunda Guerra de los Bóers fue el conflicto más largo, más costoso (£211 millones, £19.9 mil millones a precios de 2022) y el más sangriento entre 1815 y 1914, [21] : xv duró tres meses más y resultó en más bajas británicas en combate que la Guerra de Crimea (1853-1856). Las enfermedades se cobraron un mayor número de víctimas en la Guerra de Crimea, cobrándose 17.580 británicos. [23]

El conflicto se conoce comúnmente simplemente como "la Guerra de los Bóers" porque la Primera Guerra de los Bóers (diciembre de 1880 a marzo de 1881) fue un conflicto mucho más pequeño. Boer (que significa "granjero") es el nombre común de los sudafricanos blancos de habla afrikáans descendientes de los colonos originales de la Compañía Holandesa de las Indias Orientales en el Cabo de Buena Esperanza . Entre algunos sudafricanos, se la conoce como la (Segunda) Guerra Anglo-Bóer. En afrikáans , se la puede llamar (en orden de frecuencia) ' Tweede Vryheidsoorlog ("Segunda Guerra de la Libertad"), ' Tweede Boereoorlog ("Segunda Guerra de los Bóers"), Anglo-Boereoorlog ("Guerra Anglo-Bóer") o Engelse oorlog ("Guerra Inglesa"). [24]

En Sudáfrica , se la denomina oficialmente Guerra Sudafricana . [25] De hecho, según un informe de la BBC de 2011 , "la mayoría de los académicos prefieren llamar a la guerra de 1899-1902 la Guerra Sudafricana, reconociendo así que todos los sudafricanos, blancos y negros, se vieron afectados por la guerra y que muchos fueron participantes". [26]

Los orígenes de la guerra fueron complejos y se derivaron de más de un siglo de conflicto entre los bóers y Gran Bretaña. Sin embargo, de importancia inmediata fue la cuestión de quién controlaría y se beneficiaría más de las muy lucrativas minas de oro de Witwatersrand [21] : xxi descubiertas por Jan Gerrit Bantjes en junio de 1884.

El primer asentamiento europeo en Sudáfrica fue fundado en el Cabo de Buena Esperanza en 1652, y posteriormente administrado como parte de la Colonia Holandesa del Cabo . [27] El Cabo fue gobernado por la Compañía Holandesa de las Indias Orientales, hasta su quiebra a fines del siglo XVIII, y luego fue gobernado directamente por los Países Bajos . [28] Como resultado de la agitación política en los Países Bajos, los británicos ocuparon el Cabo tres veces durante las Guerras Napoleónicas , y la ocupación se volvió permanente después de que las fuerzas británicas derrotaran a los holandeses en la Batalla de Blaauwberg en 1806. [29] En ese momento, la colonia albergaba a unos 26.000 colonos asentados bajo el dominio holandés. [30] Una mayoría relativa representaba a antiguas familias holandesas traídas al Cabo a fines del siglo XVII y principios del XVIII; sin embargo, cerca de una cuarta parte de este grupo demográfico era de origen alemán y una sexta parte de ascendencia hugonote francesa . [31] Las divisiones se dieron más probablemente en función de criterios socioeconómicos que étnicos. En términos generales, los colonos incluían varios subgrupos distintos, entre ellos los bóers . [32] Los bóers eran agricultores itinerantes que vivían en las fronteras de la colonia, en busca de mejores pastos para su ganado. [28] Muchos estaban insatisfechos con aspectos de la administración británica, en particular con la abolición de la esclavitud por parte de Gran Bretaña el 1 de diciembre de 1834. Los bóers que utilizaban trabajos forzados no habrían podido cobrar una compensación por sus esclavos. [33] Entre 1836 y 1852, muchos optaron por emigrar lejos del dominio británico en lo que se conoció como la Gran Marcha . [29]

Alrededor de 15.000 bóers nómadas partieron de la Colonia del Cabo y siguieron la costa oriental hacia Natal . Después de que Gran Bretaña se anexionara Natal en 1843, viajaron más al norte hacia el vasto interior oriental de Sudáfrica. Allí, establecieron dos repúblicas bóer independientes: la República Sudafricana (1852; también conocida como la República de Transvaal) y el Estado Libre de Orange (1854). Gran Bretaña reconoció las dos repúblicas bóer en 1852 y 1854, pero el intento británico de anexión del Transvaal en 1877 condujo a la Primera Guerra Bóer en 1880-1881. Después de que Gran Bretaña sufriera derrotas, particularmente en la Batalla de la Colina de Majuba (1881), se restableció la independencia de las dos repúblicas, sujeta a ciertas condiciones. Sin embargo, las relaciones siguieron siendo tensas.

En 1866, se descubrieron diamantes en Kimberley , lo que provocó una fiebre de diamantes y una afluencia masiva de extranjeros a las fronteras del Estado Libre de Orange. Luego, en junio de 1884, Jan Gerrit Bantjes descubrió oro en la zona de Witwatersrand de la República Sudafricana . El oro convirtió al Transvaal en la nación más rica del sur de África; sin embargo, el país no tenía ni la mano de obra ni la base industrial para desarrollar el recurso por sí solo. Como resultado, el Transvaal aceptó de mala gana la inmigración de uitlanders (extranjeros), principalmente hombres de habla inglesa de Gran Bretaña, que llegaron a la región de los bóers en busca de fortuna y empleo. Como resultado, el número de uitlanders en el Transvaal amenazó con superar el número de bóers, lo que precipitó enfrentamientos entre los colonos bóers y los recién llegados no bóers.

Las ideas expansionistas de Gran Bretaña (especialmente propagadas por Cecil Rhodes ) así como las disputas sobre los derechos políticos y económicos de los uitlanders llevaron al fracaso de la incursión de Jameson en 1895. El Dr. Leander Starr Jameson , quien dirigió la incursión, tenía la intención de alentar un levantamiento de los uitlanders en Johannesburgo . Sin embargo, los uitlanders no tomaron las armas en apoyo, y las fuerzas del gobierno de Transvaal rodearon la columna y capturaron a los hombres de Jameson antes de que pudieran llegar a Johannesburgo. [21] : 1–5

A medida que las tensiones se intensificaban, se realizaron maniobras políticas y negociaciones para intentar llegar a un acuerdo sobre las cuestiones de los derechos de los uitlanders dentro de la República Sudafricana, el control de la industria minera del oro y el deseo de Gran Bretaña de incorporar el Transvaal y el Estado Libre de Orange a una federación bajo control británico. Dados los orígenes británicos de la mayoría de los uitlanders y la afluencia constante de nuevos uitlanders a Johannesburgo, los bóers reconocieron que conceder plenos derechos de voto a los uitlanders acabaría provocando la pérdida del control étnico bóer en la República Sudafricana.

Las negociaciones de junio de 1899 en Bloemfontein fracasaron, y en septiembre de 1899 el secretario colonial británico Joseph Chamberlain exigió plenos derechos de voto y representación para los uitlanders que residían en el Transvaal. Paul Kruger , presidente de la República Sudafricana, emitió un ultimátum el 9 de octubre de 1899, dando al gobierno británico 48 horas para retirar todas sus tropas de las fronteras tanto del Transvaal como del Estado Libre de Orange, en cuyo caso el Transvaal, aliado del Estado Libre de Orange, declararía la guerra al gobierno británico . (De hecho, Kruger había ordenado comandos a la frontera de Natal a principios de septiembre, y Gran Bretaña solo tenía tropas en ciudades de guarnición lejos de la frontera). [34] El gobierno británico rechazó el ultimátum de la República Sudafricana, y la República Sudafricana y el Estado Libre de Orange declararon la guerra a Gran Bretaña. [34]

En el siglo XIX, la parte sur del continente africano estuvo dominada por una serie de luchas para crear en su interior un único estado unificado. En 1868, Gran Bretaña se anexó Basutolandia , en las montañas Drakensberg , tras una apelación de Moshoeshoe I , el rey del pueblo sotho , que buscaba la protección británica contra los bóers. Si bien la Conferencia de Berlín de 1884-1885 pretendía trazar límites entre las posesiones africanas de las potencias europeas, también preparó el terreno para otras luchas. Gran Bretaña intentó anexarse primero la República Sudafricana en 1880 y luego, en 1899, tanto la República Sudafricana como el Estado Libre de Orange.

En la década de 1880, Bechuanalandia (la actual Botsuana ) se convirtió en objeto de una disputa entre los alemanes al oeste, los bóers al este y la colonia británica del Cabo al sur. Aunque Bechuanalandia no tenía valor económico, la " ruta de los misioneros " pasaba por ella hacia territorios más al norte. Después de que los alemanes se anexaran Damaralandia y Namaqualandia (la actual Namibia ) en 1884, Gran Bretaña se anexionó Bechuanalandia en 1885.

En la Primera Guerra Bóer de 1880-1881, los bóers de la República de Transvaal demostraron ser hábiles combatientes al resistir el intento de anexión de Gran Bretaña, lo que provocó una serie de derrotas británicas. El gobierno británico de William Ewart Gladstone no estaba dispuesto a verse envuelto en una guerra lejana, que requería un refuerzo sustancial de tropas y gastos, a cambio de lo que en ese momento se percibía como un beneficio mínimo. Un armisticio puso fin a la guerra y, posteriormente, se firmó un tratado de paz con el presidente de Transvaal, Paul Kruger.

En junio de 1884, los intereses imperiales británicos se vieron envueltos en el descubrimiento por parte de Jan Gerrit Bantjes de lo que resultaría ser el mayor depósito de mineral aurífero del mundo en un afloramiento sobre una gran cresta a unos 69 km (43 mi) al sur de la capital bóer, Pretoria. La cresta era conocida localmente como "Witwatersrand" (cresta de aguas blancas, una divisoria de aguas). La fiebre del oro en Transvaal atrajo a miles de británicos y otros buscadores y colonos de todo el mundo y del otro lado de la frontera desde la Colonia del Cabo, que había estado bajo control británico desde 1806.

La ciudad de Johannesburgo surgió casi de la noche a la mañana como un barrio de chabolas . Los uitlanders (extranjeros, forasteros blancos) llegaron en masa y se establecieron alrededor de las minas. La afluencia fue tan rápida que los uitlanders pronto superaron en número a los bóers en Johannesburgo y a lo largo del Rand, aunque siguieron siendo una minoría en el Transvaal. Los bóers, nerviosos y resentidos por la creciente presencia de los uitlanders, trataron de contener su influencia exigiendo largos períodos de residencia antes de poder obtener el derecho a voto; imponiendo impuestos a la industria del oro; e introduciendo controles mediante licencias, aranceles y requisitos administrativos. Entre las cuestiones que dieron lugar a tensiones entre el gobierno del Transvaal por un lado y los uitlanders y los intereses británicos por el otro, se encontraban:

Los intereses imperiales británicos se alarmaron cuando en 1894-1895 Kruger propuso construir un ferrocarril a través del África Oriental Portuguesa hasta la bahía de Delagoa , evitando los puertos controlados por los británicos en Natal y Ciudad del Cabo y evitando los aranceles británicos. [38] En ese momento, el primer ministro de la Colonia del Cabo era Cecil Rhodes, un hombre impulsado por una visión de un África controlada por los británicos que se extendiera desde el Cabo hasta El Cairo . Ciertos representantes autoproclamados de los uitlanders y propietarios de minas británicos se sintieron cada vez más frustrados y enojados por sus tratos con el gobierno de Transvaal. Se formó un Comité de Reforma (Transvaal) para representar a los uitlanders.

En 1895, se urdió un plan para tomar Johannesburgo y acabar con el control del gobierno de Transvaal con la connivencia del primer ministro de El Cabo, Rhodes, y el magnate del oro de Johannesburgo, Alfred Beit . Una columna de 600 hombres armados fue conducida a través de la frontera desde Bechuanalandia hacia Johannesburgo por Jameson, el administrador en Rhodesia de la Compañía Británica de Sudáfrica , de la que Cecil Rhodes era el presidente. La columna, formada principalmente por policías de Rodesia y Bechuanalandia de la Compañía Británica de Sudáfrica , estaba equipada con ametralladoras Maxim y algunas piezas de artillería.

El plan era hacer una carrera de tres días hasta Johannesburgo y provocar un levantamiento de los uitlanders expatriados, principalmente británicos, organizado por el Comité de Reforma de Johannesburgo , antes de que los comandos bóeres pudieran movilizarse. Sin embargo, las autoridades de Transvaal habían recibido avisos previos de la incursión de Jameson y la rastrearon desde el momento en que cruzó la frontera. Cuatro días después, la columna cansada y desanimada fue rodeada cerca de Krugersdorp , a la vista de Johannesburgo. Después de una breve escaramuza en la que la columna perdió 65 muertos y heridos, mientras que los bóeres perdieron solo un hombre, los hombres de Jameson se rindieron y fueron arrestados por los bóeres. [21] : 1–5

El fallido ataque tuvo repercusiones en todo el sur de África y en Europa. En Rhodesia, la partida de tantos policías permitió que los pueblos matabele y mashona se alzaran contra la Compañía Británica de Sudáfrica. La rebelión, conocida como la Segunda Guerra Matabele , fue reprimida a un alto precio.

Unos días después de la incursión, el káiser alemán envió un telegrama, conocido históricamente como "el telegrama Kruger ", felicitando al presidente Kruger y al gobierno de la República Sudafricana por su éxito. Cuando el texto de este telegrama fue revelado en la prensa británica, generó una tormenta de sentimiento antialemán. En el equipaje de la columna que invadió, para gran vergüenza de Gran Bretaña, los bóers encontraron telegramas de Cecil Rhodes y los otros conspiradores en Johannesburgo. Chamberlain había aprobado los planes de Rhodes de enviar ayuda armada en caso de un levantamiento en Johannesburgo, pero rápidamente condenó la incursión. Rhodes fue severamente censurado en la investigación de El Cabo y en la investigación parlamentaria de Londres y se vio obligado a dimitir como primer ministro de El Cabo y como presidente de la Compañía Británica de Sudáfrica, por haber patrocinado el fallido golpe de estado .

El gobierno bóer entregó a sus prisioneros a los británicos para que los juzgaran. Jameson fue juzgado en Inglaterra, donde la prensa británica y la sociedad londinense, inflamadas por el sentimiento antibóer y antialemán y en un frenesí de chovinismo, lo ensalzaron y lo trataron como a un héroe. Aunque fue sentenciado a 15 meses de prisión (que cumplió en Holloway ), Jameson fue recompensado más tarde con su nombramiento como primer ministro de la Colonia del Cabo (1904-1908) y finalmente fue ungido como uno de los fundadores de la Unión Sudafricana. Por conspirar con Jameson, los miembros uitlander del Comité de Reforma (Transvaal) fueron juzgados en los tribunales de Transvaal y declarados culpables de alta traición. Los cuatro líderes fueron condenados a muerte en la horca, pero al día siguiente esta sentencia fue conmutada por 15 años de prisión. En junio de 1896, los demás miembros del comité fueron liberados tras el pago de una multa de 2.000 libras cada uno, que Cecil Rhodes pagó en su totalidad. Un miembro del Comité de Reforma, Frederick Gray, se suicidó en la cárcel de Pretoria el 16 de mayo. Su muerte contribuyó a suavizar la actitud del gobierno de Transvaal hacia los prisioneros supervivientes.

Jan C. Smuts escribió en 1906:

"La incursión de Jameson fue la verdadera declaración de guerra... Y eso es así a pesar de los cuatro años de tregua que siguieron... [los] agresores consolidaron su alianza... los defensores, por otra parte, se prepararon en silencio y con tristeza para lo inevitable". [21] : 9

La incursión de Jameson alejó a muchos afrikaners del Cabo de Gran Bretaña y unió a los bóers de Transvaal en torno al presidente Kruger y su gobierno. También tuvo el efecto de unir a Transvaal y al Estado Libre de Orange (liderado por el presidente Martinus Theunis Steyn ) en oposición al imperialismo británico. En 1897, las dos repúblicas firmaron un pacto militar.

En conflictos anteriores, el arma más común de los bóers era la Westley Richards británica de retrocarga con bloque descendente. En su libro The First Boer War (La primera guerra de los bóers ), Joseph Lehmann ofrece este comentario: "Al emplear principalmente la Westley Richards de retrocarga de gran calidad (calibre 45, cartucho de papel, cápsula de percusión reemplazable en la boquilla manualmente), hicieron que fuera extremadamente peligroso para los británicos exponerse en el horizonte". [39]

.jpg/440px-Rifle,_bolt_action_(AM_1930.61-17).jpg)

Kruger reequipó al ejército de Transvaal, importando 37.000 de los últimos fusiles Mauser Modelo 1895 de 7x57 mm suministrados por Alemania, [40] y entre 40 y 50 millones de cartuchos de munición. [41] [22] : 80 Algunos comandos utilizaron el Martini-Henry Mark III, porque se habían comprado miles de estos. Desafortunadamente, la gran bocanada de humo blanco después del disparo delató la posición del tirador. [42] [43] Aproximadamente 7.000 fusiles Guedes 1885 también se habían comprado unos años antes, y también se utilizaron durante las hostilidades. [42]

A medida que avanzaba la guerra, algunos comandos dependían de los fusiles británicos capturados, como el Lee-Metford y el Enfield . [40] [26] De hecho, cuando se acabó la munición para los Mauser, los bóers dependieron principalmente de los Lee-Metford capturados. [44] [45]

Independientemente del rifle, pocos bóers usaban bayonetas. [46] [33]

Los bóers también adquirieron la mejor artillería Krupp alemana moderna de Europa. En octubre de 1899, la artillería estatal de Transvaal contaba con 73 cañones pesados, incluidos cuatro cañones de fortaleza Creusot de 155 mm [47] y 25 de los cañones Maxim Nordenfeldt de 37 mm [22] . : 80 El Maxim de los bóers, más grande que los Maxim británicos, [48] era un "cañón automático" de gran calibre, alimentado por cinta y refrigerado por agua que disparaba munición explosiva (munición sin humo) a 450 disparos por minuto. Se lo conoció como "Pom Pom". [49]

Además de las armas, las tácticas utilizadas por los bóers fueron importantes. Como afirma una fuente moderna, "los soldados bóers... eran expertos en la guerra de guerrillas, algo que los británicos tenían dificultades para contrarrestar". [50]

El ejército de Transvaal se transformó: en dos semanas se movilizaron unos 25.000 hombres equipados con fusiles y artillería modernos. Sin embargo, la victoria del presidente Kruger en el incidente de Jameson Raid no resolvió el problema fundamental de encontrar una fórmula para conciliar a los uitlanders sin renunciar a la independencia de Transvaal.

El fracaso en la obtención de derechos mejorados para los uitlanders (notablemente el impuesto a la dinamita de los yacimientos de oro) se convirtió en un pretexto para la guerra y una justificación para una gran acumulación militar en la Colonia del Cabo. El caso de la guerra fue desarrollado y defendido hasta en las colonias australianas. [51] El gobernador de la Colonia del Cabo, Sir Alfred Milner ; Rhodes; Chamberlain; y los propietarios de sindicatos mineros como Beit, Barney Barnato y Lionel Phillips , favorecieron la anexión de las repúblicas bóer. Confiados en que los bóers serían derrotados rápidamente, planearon y organizaron una guerra corta, citando las quejas de los uitlanders como la motivación para el conflicto. En contraste, la influencia del partido de la guerra dentro del gobierno británico fue limitada. El primer ministro del Reino Unido, Lord Salisbury , despreciaba el chovinismo y a los chovinistas. [52] También estaba inseguro de las habilidades del ejército británico. A pesar de sus reservas morales y prácticas, Salisbury llevó al Reino Unido a la guerra para preservar el prestigio del Imperio Británico y sentir un sentido de obligación hacia los sudafricanos británicos. [e] Salisbury también detestaba el trato que los bóers daban a los africanos nativos, refiriéndose a la Convención de Londres de 1884 (tras la derrota de Gran Bretaña en la primera guerra), como un acuerdo "realmente en interés de la esclavitud". [53] : 7 [53] : 6 Salisbury no estaba solo en esta preocupación. Roger Casement , que ya estaba en camino de convertirse en un nacionalista irlandés, estaba sin embargo feliz de reunir información para los británicos contra los bóers debido a su crueldad hacia los africanos. [54]

El gobierno británico hizo caso omiso del consejo de sus generales (incluido Wolseley) y se negó a enviar refuerzos sustanciales a Sudáfrica antes de que estallara la guerra. El Secretario de Estado para la Guerra, Lansdowne, no creía que los bóers se estuvieran preparando para la guerra y que si Gran Bretaña enviaba grandes cantidades de tropas a la región, adoptaría una postura demasiado agresiva y posiblemente haría fracasar un acuerdo negociado, o incluso alentaría un ataque bóer. [55]

Steyn, del Estado Libre de Orange, invitó a Milner y Kruger a asistir a una conferencia en Bloemfontein . La conferencia comenzó el 30 de mayo de 1899, pero las negociaciones fracasaron rápidamente, ya que Kruger no tenía intención de otorgar concesiones significativas, [56] : 91 y Milner no tenía intención de aceptar sus tácticas dilatorias habituales. [57]

El 9 de octubre de 1899, después de convencer al Estado Libre de Orange para que se uniera a él y movilizar sus fuerzas, Kruger emitió un ultimátum que le daba a Gran Bretaña 48 horas para retirar todas sus tropas de la frontera de Transvaal (a pesar del hecho de que las únicas tropas regulares del ejército británico en cualquier lugar cerca de la frontera de cualquiera de las repúblicas eran 4 compañías de los Leales Lancs del Norte , que habían sido desplegados para defender Kimberley. [58] : 14 ) De lo contrario, Transvaal, aliado con el Estado Libre de Orange, declararía la guerra.

La noticia del ultimátum llegó a Londres el día en que expiró. Las principales reacciones fueron la indignación y las risas. El editor del Times supuestamente se rió a carcajadas cuando lo leyó, diciendo que "un documento oficial rara vez es divertido y útil, pero este era ambas cosas". El Times denunció el ultimátum como una "farsa extravagante" y The Globe denunció a este "pequeño Estado farsante". La mayoría de los editoriales fueron similares al del Daily Telegraph , que declaró: "Por supuesto, solo puede haber una respuesta a este desafío grotesco. ¡Kruger ha pedido la guerra y la guerra debe tenerla!" [ cita requerida ]

Estas opiniones estaban lejos de las del gobierno británico y de las de los miembros del ejército. Para la mayoría de los observadores sensatos, la reforma del ejército había sido un asunto de preocupación acuciante desde la década de 1870, constantemente postergada porque el público británico no quería el gasto de un ejército más grande y más profesional y porque un gran ejército nacional no era políticamente bien recibido. Lord Salisbury, el Primer Ministro, tuvo que decirle a una sorprendida Reina Victoria que "no tenemos un ejército capaz de enfrentarse ni siquiera a una potencia continental de segunda clase". [53] : 4

Cuando la guerra con las repúblicas bóeres era inminente en septiembre de 1899, se movilizó una fuerza de campo, conocida como el Cuerpo de Ejército (a veces 1.er Cuerpo de Ejército), y se envió a Ciudad del Cabo. Era "aproximadamente el equivalente al I Cuerpo de Ejército del esquema de movilización existente" y se puso bajo el mando del general Sir Redvers Buller , oficial general comandante en jefe del Comando de Aldershot . [59] En Sudáfrica, el cuerpo nunca operó como tal y las divisiones 1.ª , 2.ª y 3.ª estaban ampliamente dispersas.

El 11 de octubre de 1899 se declaró la guerra con una ofensiva bóer en las zonas de Natal y la Colonia del Cabo, bajo control británico. Los bóers contaban con unos 33.000 soldados y superaban decisivamente en número a los británicos, que sólo podían trasladar 13.000 tropas a la línea del frente. [60] Los bóers no tuvieron problemas con la movilización, ya que los bóers, ferozmente independientes, no contaban con unidades regulares del ejército, aparte de la Staatsartillerie (en holandés, "Artillería del Estado") de ambas repúblicas. Al igual que en la Primera Guerra Bóer, dado que la mayoría de los bóers eran miembros de milicias civiles, ninguno había adoptado uniformes o insignias. Sólo los miembros de la Staatsartillerie llevaban uniformes de color verde claro.

Cuando se cernía el peligro, todos los burgueses (ciudadanos) de un distrito formaban una unidad militar llamada comando y elegían oficiales. Un funcionario a tiempo completo llamado Veldkornet llevaba listas de revista pero no tenía poderes disciplinarios. Cada hombre traía su propia arma, normalmente un rifle de caza, y su propio caballo. A los que no podían permitirse un arma las autoridades les daban una. [22] : 80 Los presidentes del Transvaal y del Estado Libre de Orange simplemente firmaban decretos para concentrarse en una semana, y los comandos podían reunir entre 30.000 y 40.000 hombres. [21] : 56 Sin embargo, el bóer medio no tenía sed de guerra. Muchos no esperaban luchar contra sus compañeros cristianos y, en general, contra sus compañeros protestantes. Muchos pueden haber tenido una idea demasiado optimista de lo que implicaría la guerra, imaginando que la victoria podría lograrse tan rápida y fácilmente como lo había sido en la Primera Guerra Anglo-Bóer. [22] : 74 Muchos, incluidos muchos generales, también tenían la sensación de que su causa era santa y justa, y bendecida por Dios. [22] : 179

Pronto se hizo evidente que las fuerzas bóeres representaban un grave desafío táctico para las fuerzas británicas. Lo que los bóeres presentaban era un enfoque móvil e innovador de la guerra, basado en sus experiencias de la Primera Guerra Bóer. Los bóeres promedio que componían sus comandos eran granjeros que habían pasado casi toda su vida laboral a caballo, tanto como granjeros como cazadores. Dependían de la olla, el caballo y el rifle; también eran hábiles acechadores y tiradores. Como cazadores, habían aprendido a disparar desde una posición a cubierto , boca abajo y a hacer que el primer disparo contara, sabiendo que si fallaban, la presa o bien se habría ido hace mucho tiempo o podría atacar y potencialmente matarlos.

En las reuniones comunitarias, el tiro al blanco era un deporte importante; practicaban el tiro a objetivos, como huevos de gallina posados en postes a 100 metros de distancia. Formaban una infantería montada experta , que utilizaba cada trozo de cobertura desde el que podían lanzar un fuego destructivo utilizando modernos rifles Mauser sin humo . En preparación para las hostilidades, los bóers habían adquirido alrededor de cien de los últimos cañones de campaña Krupp , todos tirados por caballos y dispersos entre los diversos grupos Kommando y varios cañones de asedio Le Creusot "Long Tom". La habilidad de los bóers para adaptarse y convertirse en artilleros de primera clase demuestra que eran un adversario versátil. [21] : 30 El Transvaal también tenía un servicio de inteligencia que se extendía por toda Sudáfrica y de cuya extensión y eficiencia los británicos aún desconocían. [22] : 81

Los bóers atacaron primero el 12 de octubre en la batalla de Kraaipan , un ataque que anunció la invasión de la Colonia del Cabo y Natal entre octubre de 1899 y enero de 1900. [58] : 20 Con velocidad y sorpresa, los bóers avanzaron rápidamente hacia la guarnición británica en Ladysmith y las más pequeñas en Mafeking y Kimberley. La rápida movilización bóer resultó en éxitos militares tempranos contra las fuerzas británicas dispersas. Sir George Stuart White , al mando de la división británica en Ladysmith , permitió imprudentemente que el mayor general Penn Symons lanzara una brigada hacia la ciudad minera de carbón de Dundee (también reportada como Glencoe), que estaba rodeada de colinas. Este se convirtió en el sitio del primer enfrentamiento importante de la guerra, la batalla de Talana Hill . Los cañones bóer comenzaron a bombardear el campamento británico desde la cima de Talana Hill al amanecer del 20 de octubre. Penn Symons contraatacó inmediatamente: su infantería expulsó a los bóers de la colina, lo que provocó la pérdida de 446 bajas británicas, incluido Penn Symons.

Otra fuerza bóer ocupó Elandslaagte, que se encontraba entre Ladysmith y Dundee. Los británicos, bajo el mando del mayor general John French y el coronel Ian Hamilton, atacaron para despejar la línea de comunicaciones con Dundee. La batalla de Elandslaagte resultante fue una clara victoria táctica británica, [58] : 29 pero Sir George White temía que más bóers estuvieran a punto de atacar su posición principal y ordenó una retirada caótica de Elandslaagte, desperdiciando cualquier ventaja obtenida. El destacamento de Dundee se vio obligado a realizar una agotadora retirada campo a través para reunirse con la fuerza principal de White. Cuando los bóers rodearon Ladysmith y abrieron fuego contra la ciudad con armas de asedio, White ordenó una importante salida contra sus posiciones. [58] : 33 El resultado fue un desastre, con 140 hombres muertos y más de 1.000 capturados. Comenzó el asedio de Ladysmith: iba a durar varios meses.

Mientras tanto, al noroeste, en Mafeking, en la frontera con Transvaal, el coronel Robert Baden-Powell había reclutado dos regimientos de fuerzas locales que sumaban unos 1.200 hombres para atacar y crear distracciones si las cosas iban mal más al sur. Como nudo ferroviario, Mafeking proporcionaba buenas instalaciones de suministro y era el lugar obvio para que Baden-Powell se fortificara en preparación para tales ataques. Sin embargo, en lugar de ser el agresor, Baden-Powell se vio obligado a defender Mafeking cuando 6.000 bóeres, comandados por Piet Cronjé , intentaron un asalto decidido a la ciudad. Esto rápidamente se convirtió en un asunto desganado, con los bóers dispuestos a matar de hambre la fortaleza hasta que se rindiera. Así, el 13 de octubre, comenzó el asedio de 217 días de Mafeking.

Por último, a más de 360 kilómetros (220 millas) al sur de Mafeking se encontraba la ciudad minera de diamantes de Kimberley, que también fue asediada. Aunque no era importante desde el punto de vista militar, representaba un enclave del imperialismo británico en las fronteras del Estado Libre de Orange y, por lo tanto, era un objetivo importante de los bóers. A principios de noviembre, unos 7.500 bóers comenzaron su asedio, nuevamente satisfechos con matar de hambre a la ciudad hasta que se rindiera. A pesar del bombardeo bóer, los 40.000 habitantes, de los cuales solo 5.000 estaban armados, estaban poco amenazados, porque la ciudad estaba bien provista de provisiones. La guarnición estaba comandada por el teniente coronel Robert Kekewich , aunque Rhodes también era una figura destacada en las defensas de la ciudad.

La vida en el asedio se cobró su precio tanto para los soldados defensores como para los civiles en las ciudades de Mafeking, Ladysmith y Kimberley, ya que la comida empezó a escasear después de unas semanas. En Mafeking, Sol Plaatje escribió: "Vi por primera vez que la carne de caballo era tratada como alimento humano". Las ciudades asediadas también tuvieron que lidiar con constantes bombardeos de artillería, lo que convirtió las calles en un lugar peligroso. Cerca del final del asedio de Kimberley, se esperaba que los bóers intensificaran su bombardeo, por lo que Rhodes colocó un cartel animando a la gente a bajar a los pozos de la mina de Kimberley para protegerse. Los habitantes del pueblo entraron en pánico y acudieron a los pozos de la mina constantemente durante un período de 12 horas. Aunque el bombardeo nunca se produjo, esto no hizo nada para disminuir la angustia de los ansiosos civiles. Los habitantes más adinerados, incluido Cecil Rhodes, se refugiaron en el Sanatorio, donde se encuentra actualmente el Museo McGregor ; Los residentes más pobres, especialmente la población negra, no tenían ningún refugio contra los bombardeos.

En retrospectiva, la decisión de los bóers de comprometerse con asedios ( Sitzkrieg ) fue un error y una de las mejores ilustraciones de su falta de visión estratégica [ ¿según quién? ] [ cita requerida ] . Históricamente, tuvo poco a su favor. De los siete asedios de la Primera Guerra Bóer, los bóers no habían prevalecido en ninguno. Más importante aún, devolvió la iniciativa a los británicos y les dio tiempo para recuperarse, lo que hicieron. En términos generales, durante toda la campaña, los bóers fueron demasiado defensivos y pasivos, desperdiciando las oportunidades que tuvieron para la victoria. Sin embargo, esa pasividad también testificó el hecho de que no tenían ningún deseo de conquistar territorio británico, sino solo preservar su capacidad de gobernar en su propio territorio. [22] : 82–85

El 31 de octubre de 1899, el general Sir Redvers Henry Buller , un comandante muy respetado, llegó a Sudáfrica con el Cuerpo de Ejército, compuesto por las divisiones 1.ª, 2.ª y 3.ª. Buller originalmente pretendía una ofensiva directamente a lo largo de la línea ferroviaria que conducía desde Ciudad del Cabo a través de Bloemfontein hasta Pretoria. Al descubrir a su llegada que las tropas británicas que ya estaban en Sudáfrica estaban bajo asedio, dividió su cuerpo de ejército en destacamentos para aliviar las guarniciones asediadas. Una división, dirigida por el teniente general Lord Methuen , debía seguir el Ferrocarril Occidental hacia el norte y aliviar Kimberley y Mafeking. Una fuerza más pequeña de unos 3.000, dirigida por el mayor general William Gatacre , debía avanzar hacia el norte hacia el cruce ferroviario en Stormberg y asegurar el Distrito de Cape Midlands de las incursiones bóeres y las rebeliones locales de los habitantes bóeres. Buller dirigió la mayor parte del cuerpo de ejército para aliviar Ladysmith hacia el este.

Los resultados iniciales de esta ofensiva fueron dispares: Methuen ganó varias escaramuzas sangrientas en la batalla de Belmont el 23 de noviembre, la batalla de Graspan el 25 de noviembre y en un enfrentamiento más grande, la batalla del río Modder , el 28 de noviembre, que resultó en pérdidas británicas de 71 muertos y más de 400 heridos. Los comandantes británicos habían sido entrenados con las lecciones de la guerra de Crimea y eran expertos en maniobras de batallón y regimiento, con columnas que maniobraban en selvas, desiertos y regiones montañosas. Lo que los generales británicos no lograron comprender fue el impacto del fuego destructivo desde posiciones de trinchera y la movilidad de las incursiones de caballería. Las tropas británicas fueron a la guerra con lo que demostrarían ser tácticas anticuadas, y en algunos casos armas anticuadas, contra las móviles fuerzas bóer con el fuego destructivo de sus modernos Mauser, los últimos cañones de campaña Krupp y sus novedosas tácticas. [61]

La mitad de diciembre fue desastrosa para el ejército británico. En un período conocido como la Semana Negra (del 10 al 15 de diciembre de 1899), los británicos sufrieron derrotas en cada uno de los tres frentes. El 10 de diciembre, el general Gatacre intentó recuperar el cruce ferroviario de Stormberg, a unos 80 kilómetros (50 millas) al sur del río Orange . El ataque de Gatacre estuvo marcado por errores administrativos y tácticos y la batalla de Stormberg terminó con una derrota británica, con 135 muertos y heridos y dos cañones y más de 600 soldados capturados.

En la batalla de Magersfontein , el 11 de diciembre, los 14.000 soldados británicos de Methuen intentaron capturar una posición bóer en un ataque al amanecer para liberar a Kimberley. Esto también resultó en un desastre cuando la Brigada de las Tierras Altas quedó atrapada por el fuego preciso de los bóeres. Después de sufrir un calor y una sed intensos durante nueve horas, finalmente se retiraron en una retirada indisciplinada. Los comandantes bóer, Koos de la Rey y Cronjé, habían ordenado que se cavaran trincheras en un lugar poco convencional para engañar a los británicos y dar a sus fusileros un mayor alcance de tiro. El plan funcionó, y esta táctica ayudó a escribir la doctrina de la supremacía de la posición defensiva, utilizando armas pequeñas modernas y fortificaciones de trincheras. [62] [ cita requerida ] Los británicos perdieron 120 muertos y 690 heridos y se les impidió liberar a Kimberley y Mafeking. Un soldado británico dijo de la derrota:

Así fue el día para nuestro regimiento

. Teme la venganza que tomaremos.

Pagamos caro el error

. El error de un general de salón.

¿Por qué no nos informaron sobre las trincheras?

¿Por qué no nos informaron sobre el alambre de púas?

¿Por qué nos hicieron marchar en columna?

Que Tommy Atkins pregunte...— Soldado Smith [f]

El punto más bajo de la Semana Negra fue la Batalla de Colenso el 15 de diciembre, donde 21.000 tropas británicas, comandadas por Buller, intentaron cruzar el río Tugela para relevar a Ladysmith, donde les esperaban 8.000 bóers de Transvaal bajo el mando de Louis Botha . Mediante una combinación de artillería y fuego de fusilería preciso y un mejor uso del terreno, los bóers repelieron todos los intentos británicos de cruzar el río. Después de que sus primeros ataques fracasaran, Buller interrumpió la batalla y ordenó la retirada, abandonando a muchos hombres heridos, varias unidades aisladas y diez cañones de campaña para que fueran capturados por los hombres de Botha. Las fuerzas de Buller perdieron 145 hombres muertos y 1.200 desaparecidos o heridos y los bóers sufrieron solo 40 bajas, incluidos 8 muertos. [53] : 12

El gobierno británico se tomó muy mal estas derrotas y, como los asedios aún continuaban, se vio obligado a enviar dos divisiones más y un gran número de voluntarios coloniales. En enero de 1900, esta se convertiría en la fuerza más grande que Gran Bretaña había enviado nunca al extranjero, con unos 180.000 hombres y se buscaban más refuerzos. [11]

Mientras esperaba a que llegaran los refuerzos, Buller intentó de nuevo liberar a Ladysmith cruzando el río Tugela al oeste de Colenso . El subordinado de Buller, el mayor general Charles Warren , cruzó el río con éxito, pero se encontró con una nueva posición defensiva centrada en una colina prominente conocida como Spion Kop. En la batalla de Spion Kop, las tropas británicas capturaron la cumbre por sorpresa durante las primeras horas del 24 de enero de 1900, pero cuando se disipó la niebla matinal, se dieron cuenta demasiado tarde de que los emplazamientos de los cañones bóer en las colinas circundantes los habían pasado por alto. El resto del día resultó en un desastre causado por la mala comunicación entre Buller y sus comandantes. Entre ellos emitieron órdenes contradictorias, por un lado ordenando a los hombres que abandonaran la colina, mientras que otros oficiales ordenaron nuevos refuerzos para defenderla. El resultado fue 350 hombres muertos y casi 1.000 heridos y una retirada a través del río Tugela hacia territorio británico. Hubo casi 300 bajas bóer.

Buller atacó nuevamente a Louis Botha el 5 de febrero en Vaal Krantz y fue nuevamente derrotado. Buller se retiró pronto cuando pareció que los británicos quedarían aislados en una cabeza de puente expuesta al otro lado del río Tugela, por lo que algunos de sus oficiales lo apodaron "Sir Reverse".

Al tomar el mando en persona en Natal, Buller había dejado que la dirección general de la guerra se desviara. Debido a las preocupaciones sobre su desempeño y los informes negativos desde el campo, fue reemplazado como comandante en jefe por Roberts. Roberts reunió rápidamente un equipo completamente nuevo para el personal del cuartel general y eligió a militares de todas partes: Kitchener (Jefe del Estado Mayor) de Sudán; Frederick Russell Burnham (Jefe de Scouts), el scout estadounidense, de Klondike; George Henderson de la Escuela Superior del Estado Mayor; Neville Bowles Chamberlain de Afganistán; y William Nicholson (Secretario Militar) de Calcuta. [ cita requerida ] Al igual que Buller, Roberts primero tenía la intención de atacar directamente a lo largo de la vía férrea Ciudad del Cabo-Pretoria pero, nuevamente como Buller, se vio obligado a relevar a las guarniciones asediadas. Dejando a Buller al mando en Natal, Roberts concentró su fuerza principal cerca del río Orange y a lo largo del Ferrocarril Occidental detrás de la fuerza de Methuen en el río Modder y se preparó para hacer un amplio movimiento de flanqueo para relevar a Kimberley.

Excepto en Natal, la guerra se había estancado. Aparte de un único intento de asaltar Ladysmith, los bóers no hicieron ningún intento de capturar las ciudades asediadas. En las Midlands del Cabo, los bóers no aprovecharon la derrota británica en Stormberg y se les impidió capturar el nudo ferroviario en Colesberg . En el verano seco, el pasto en el veld se secó, debilitando los caballos y bueyes de tiro de los bóers, y muchas familias bóers se unieron a sus hombres en las líneas de asedio y los laagers (campamentos), obstaculizando fatalmente el ejército de Cronjé.

Roberts lanzó su ataque principal el 10 de febrero de 1900 y, aunque se vio obstaculizado por una larga ruta de suministro, logró flanquear a los bóers que defendían Magersfontein . El 14 de febrero, una división de caballería al mando de French lanzó un gran ataque para liberar a Kimberley. Aunque se encontró con un intenso fuego, una carga de caballería en masa dividió las defensas bóer el 15 de febrero, abriendo el camino para que los franceses entraran en Kimberley esa noche, poniendo fin a su asedio de 124 días.

Mientras tanto, Roberts persiguió a la fuerza de 7.000 hombres de Piet Cronjé, que había abandonado Magersfontein para dirigirse a Bloemfontein. La caballería del general French recibió órdenes de ayudar en la persecución, embarcándose en un avance épico de 50 km (31 millas) hacia Paardeberg, donde Cronjé intentaba cruzar el río Modder. En la batalla de Paardeberg, del 18 al 27 de febrero, Roberts rodeó al ejército bóer de Cronjé en retirada. El 17 de febrero, un movimiento de pinza en el que participaron tanto la caballería de French como la principal fuerza británica intentó tomar la posición atrincherada, pero los ataques frontales no estaban coordinados y, por lo tanto, fueron rechazados por los bóers. Finalmente, Roberts recurrió a bombardear a Cronjé para someterlo. Tardó diez días, y cuando las tropas británicas utilizaron el contaminado río Modder como suministro de agua, la fiebre tifoidea mató a muchos soldados. El general Cronjé se vio obligado a rendirse en Surrender Hill con 4.000 hombres.

En Natal, la batalla de las Alturas de Tugela , que comenzó el 14 de febrero, fue el cuarto intento de Buller de liberar a Ladysmith. Las pérdidas que habían sufrido las tropas de Buller lo convencieron de adoptar tácticas bóer "en la línea de fuego: avanzar en pequeñas acometidas, cubiertos por el fuego de fusilería desde atrás; utilizar el apoyo táctico de la artillería; y sobre todo, utilizar el terreno, haciendo que la roca y la tierra trabajen para ellos como lo hacían para el enemigo". A pesar de los refuerzos, su avance fue dolorosamente lento contra una dura oposición. Sin embargo, el 26 de febrero, después de mucha deliberación, Buller utilizó todas sus fuerzas en un ataque total por primera vez y finalmente logró forzar un cruce del Tugela para derrotar a las fuerzas de Botha, superadas en número, al norte de Colenso. Después de un asedio que duró 118 días, el alivio de Ladysmith se efectuó, al día siguiente de la rendición de Cronjé, pero con un costo total de 7.000 bajas británicas. Las tropas de Buller marcharon hacia Ladysmith el 28 de febrero. [63]

Después de una sucesión de derrotas, los bóers se dieron cuenta de que contra un número tan abrumador de tropas, tenían pocas posibilidades de derrotar a los británicos y se desmoralizaron. Roberts avanzó entonces hacia el Estado Libre de Orange desde el oeste, poniendo en fuga a los bóers en la batalla de Poplar Grove y capturando Bloemfontein, la capital, sin oposición el 13 de marzo, mientras los defensores bóers escapaban y se dispersaban. Mientras tanto, destacó una pequeña fuerza para relevar a Baden-Powell. El relevo de Mafeking el 18 de mayo de 1900 provocó celebraciones desenfrenadas en Gran Bretaña, el origen de la palabra del argot eduardiano "mafficking". El 28 de mayo, el Estado Libre de Orange fue anexado y rebautizado como Colonia del Río Orange.

Después de verse obligado a retrasarse durante varias semanas en Bloemfontein por la escasez de suministros, un brote de fiebre tifoidea en Paardeberg y una mala atención médica, Roberts finalmente reanudó su avance. [64] Se vio obligado a detenerse nuevamente en Kroonstad durante 10 días, una vez más debido al colapso de sus sistemas médicos y de suministro, pero finalmente capturó Johannesburgo el 31 de mayo y la capital del Transvaal, Pretoria, el 5 de junio. El primero en llegar a Pretoria fue el teniente William Watson de los Fusileros Montados de Nueva Gales del Sur, quien persuadió a los bóers para que entregaran la capital. [65] Antes de la guerra, los bóers habían construido varios fuertes al sur de Pretoria, pero la artillería había sido retirada de los fuertes para su uso en el campo de batalla, y en caso de que así fuera, abandonaron Pretoria sin luchar. Habiendo ganado las ciudades principales, Roberts declaró el fin de la guerra el 3 de septiembre de 1900; y la República Sudafricana fue anexionada formalmente.

Los observadores británicos creían que la guerra estaba prácticamente terminada tras la captura de las dos capitales. Sin embargo, los bóers se habían reunido antes en la nueva capital temporal del Estado Libre de Orange, Kroonstad , y habían planeado una campaña de guerrillas para atacar las líneas de suministro y comunicación británicas. El primer enfrentamiento de esta nueva forma de guerra tuvo lugar en el puesto de Sanna el 31 de marzo, donde 1.500 bóers bajo el mando de Christiaan de Wet atacaron las obras hidráulicas de Bloemfontein a unos 37 kilómetros (23 millas) al este de la ciudad y tendieron una emboscada a un convoy fuertemente escoltado, lo que provocó 155 bajas británicas y la captura de siete cañones, 117 carros y 428 tropas británicas. [66]

Tras la caída de Pretoria, una de las últimas batallas formales fue la de Diamond Hill , entre el 11 y el 12 de junio, donde Roberts intentó expulsar a los restos del ejército de campaña bóer al mando de Botha más allá de la distancia de ataque de Pretoria. Aunque Roberts expulsó a los bóers de la colina, Botha no lo consideró una derrota, ya que infligió 162 bajas a los británicos mientras que él solo sufrió alrededor de 50 bajas.

El período de preparación de la guerra dio paso en gran medida a una guerra de guerrillas móvil, pero quedaba una operación final. El presidente Kruger y lo que quedaba del gobierno de Transvaal se habían retirado al este de Transvaal. Roberts, junto con tropas de Natal bajo el mando de Buller, avanzó contra ellos y rompió su última posición defensiva en Bergendal el 26 de agosto. Mientras Roberts y Buller seguían por la línea ferroviaria hacia Komatipoort , Kruger buscó asilo en el África Oriental Portuguesa (actual Mozambique ). Algunos bóers desanimados hicieron lo mismo y los británicos reunieron mucho material de guerra. Sin embargo, el núcleo de los combatientes bóer bajo el mando de Botha se abrió paso fácilmente a través de las montañas Drakensberg hacia el altiplano de Transvaal después de cabalgar hacia el norte a través del bushveld.

Mientras el ejército de Roberts ocupaba Pretoria, los combatientes bóeres del Estado Libre de Orange se retiraron a la cuenca de Brandwater , una zona fértil en el sureste de la República. Esto sólo ofrecía un refugio temporal, ya que los pasos de montaña que conducían a ella podían ser ocupados por los británicos, atrapando a los bóeres. Una fuerza al mando del general Archibald Hunter partió de Bloemfontein para lograrlo en julio de 1900. El núcleo duro de los bóeres del Estado Libre bajo el mando de De Wet, acompañado por el presidente Steyn, abandonó la cuenca pronto. Los que quedaron cayeron en la confusión y la mayoría no logró escapar antes de que Hunter los atrapara. 4.500 bóeres se rindieron y se capturó gran parte del equipo, pero al igual que con la ofensiva de Roberts contra Kruger al mismo tiempo, estas pérdidas tuvieron relativamente poca importancia, ya que el núcleo duro de los ejércitos bóer y sus líderes más decididos y activos permanecieron en libertad.

Desde la cuenca, Christiaan de Wet se dirigió al oeste. Aunque acosado por las columnas británicas, logró cruzar el Vaal hacia el Transvaal occidental, para permitir que Steyn viajara a reunirse con sus líderes. Había mucha simpatía por los bóers en la Europa continental. En octubre, el presidente Kruger y miembros del gobierno del Transvaal abandonaron el África Oriental Portuguesa en el buque de guerra holandés De Gelderland , enviado por la reina Guillermina de los Países Bajos . Sin embargo, la esposa de Paul Kruger estaba demasiado enferma para viajar y permaneció en Sudáfrica, donde murió el 20 de julio de 1901 sin volver a ver a su marido. El presidente Kruger fue primero a Marsella y luego a los Países Bajos, donde permaneció un tiempo antes de trasladarse finalmente a Clarens, Suiza , donde murió en el exilio el 14 de julio de 1904.

El primer grupo considerable de prisioneros de guerra bóeres capturados por los británicos consistió en aquellos capturados en la batalla de Elandslaagte el 21 de octubre de 1899. Inicialmente, estos prisioneros de guerra fueron retenidos en buques de transporte de tropas en Simons Bay hasta que se completaron los campos de prisioneros de guerra en Ciudad del Cabo y Simonstown . En total, se establecerían seis campos de prisioneros de guerra en Sudáfrica durante la guerra. [67] A medida que aumentaba el número, los británicos decidieron que no querían que se mantuvieran en la zona. La captura de 4000 prisioneros de guerra en febrero de 1900 fue un evento clave, que hizo que los británicos se dieran cuenta de que no podían acomodar a todos los prisioneros de guerra en Sudáfrica. [68] Los británicos temían que pudieran ser liberados por lugareños comprensivos. Además, ya tenían problemas para abastecer a sus propias tropas en Sudáfrica y no querían la carga adicional de enviar suministros para los prisioneros de guerra. Por lo tanto, Gran Bretaña decidió enviar muchos prisioneros de guerra al extranjero.

En consecuencia, se establecieron alrededor de 31 campos de prisioneros de guerra en colonias británicas en ultramar durante la guerra. [67] Los primeros campos en el extranjero (fuera del continente africano) se abrieron en Santa Elena , que finalmente recibió a unos 5.000 prisioneros de guerra. [69] Alrededor de 5.000 prisioneros de guerra fueron enviados a Ceilán . [70] Otros prisioneros de guerra fueron enviados a Bermudas y la India . [68]

En total, casi 26.000 prisioneros de guerra fueron enviados al extranjero. [71]

El 15 de marzo de 1900, Lord Roberts proclamó una amnistía para todos los burgueses , excepto los líderes, quienes hicieron un juramento de neutralidad y regresaron tranquilamente a sus hogares. [72] Se estima que entre 12.000 y 14.000 burgueses tomaron este juramento entre marzo y junio de 1900. [73]

En septiembre de 1900, los británicos tenían el control nominal de ambas repúblicas, con excepción de la parte norte del Transvaal. Sin embargo, pronto descubrieron que solo controlaban el territorio que sus columnas ocupaban físicamente. A pesar de la pérdida de sus dos capitales y la mitad de su ejército, los comandantes bóer adoptaron tácticas de guerra de guerrillas , principalmente realizando incursiones contra vías férreas y objetivos de recursos y suministros, todo ello con el objetivo de interrumpir la capacidad operativa del ejército británico. Evitaron las batallas campales y las bajas fueron escasas.

Cada unidad de comando bóer era enviada al distrito en el que se habían reclutado sus miembros, lo que significaba que podían contar con el apoyo local y el conocimiento personal del terreno y de las ciudades dentro del distrito, lo que les permitía vivir de la tierra. Sus órdenes eran simplemente actuar contra los británicos siempre que fuera posible. Sus tácticas eran atacar rápido y con fuerza causando el mayor daño posible al enemigo, y luego retirarse y desaparecer antes de que pudieran llegar los refuerzos enemigos. Las grandes distancias de las repúblicas permitían a los comandos bóer una considerable libertad para moverse e hicieron que fuera casi imposible para los 250.000 soldados británicos controlar el territorio de manera efectiva utilizando solo columnas. Tan pronto como una columna británica abandonaba una ciudad o distrito, el control británico de esa área se desvanecía. Los comandos bóer fueron especialmente eficaces durante la fase inicial de guerrilla de la guerra porque Roberts había asumido que la guerra terminaría con la captura de las capitales bóer y la dispersión de los principales ejércitos bóer. Por lo tanto, muchas tropas británicas fueron reubicadas fuera del área y reemplazadas por contingentes de menor calidad de Yeomanry Imperial y cuerpos irregulares reclutados localmente.

A finales de mayo de 1900, los primeros éxitos de la estrategia guerrillera bóer se produjeron en Lindley (donde se rindieron 500 soldados de la Yeomanry) y en Heilbron (donde un gran convoy y su escolta fueron capturados) y otras escaramuzas que resultaron en 1.500 bajas británicas en menos de diez días. En diciembre de 1900, De la Rey y Christiaan Beyers atacaron y destrozaron una brigada británica en Nooitgedacht , infligiendo más de 650 bajas. Como resultado de estos y otros éxitos bóeres, los británicos, liderados por Lord Kitchener, organizaron tres extensas búsquedas de Christiaan de Wet , pero sin éxito. Sin embargo, las incursiones bóer en los campamentos del ejército británico y otros objetivos fueron esporádicas y mal planificadas, y la naturaleza misma de la guerra de guerrillas bóer en sí no tenía prácticamente objetivos generales a largo plazo, con la excepción de simplemente hostigar a los británicos. Esto condujo a un patrón desorganizado de enfrentamientos dispersos entre los británicos y los bóeres en toda la región.

Los británicos se vieron obligados a revisar rápidamente sus tácticas. Se concentraron en restringir la libertad de movimiento de los comandos bóer y privarlos del apoyo local. Las líneas ferroviarias habían proporcionado vías vitales de comunicación y suministro, y a medida que los británicos avanzaban por Sudáfrica, habían utilizado trenes blindados y habían establecido fortificaciones en puntos clave. [74] Ahora construyeron fortines adicionales (cada uno de ellos albergaba entre seis y ocho soldados) y los fortificaron para proteger las rutas de suministro contra los invasores bóer . Finalmente, se construyeron unos 8.000 de estos fortines en las dos repúblicas sudafricanas, que se extendían desde las ciudades más grandes a lo largo de las rutas principales. Cada fortín costaba entre 800 y 1.000 libras esterlinas y tardaban unos tres meses en construirse. A pesar del gasto, demostraron ser muy eficaces; ni un solo puente en el que se había situado un fortín y había personal fue volado. [74]

El sistema de fortines requería una enorme cantidad de tropas para guarnecerlo. Más de 50.000 soldados británicos, o 50 batallones, participaban en tareas de fortín, más que los aproximadamente 30.000 bóers que estaban en el campo durante la fase guerrillera. Además, se utilizaron hasta 16.000 africanos como guardias armados y para patrullar la línea por la noche. [74] El ejército unió los fortines con vallas de alambre de púas para dividir el amplio veld en áreas más pequeñas. Se organizaron campañas de "Nuevo Modelo" bajo las cuales una línea continua de tropas podía barrer una zona de veld delimitada por líneas de fortines, a diferencia de la ineficaz limpieza del campo que se hacía anteriormente con columnas dispersas.

Los británicos también pusieron en práctica una política de tierra quemada, en virtud de la cual atacaron todo lo que pudiera dar sustento a las guerrillas bóer en las zonas controladas, con el fin de dificultarles la supervivencia. Mientras las tropas británicas arrasaban el campo, destruyeron sistemáticamente los cultivos, quemaron casas y granjas e internaron a hombres, mujeres, niños y trabajadores bóeres y africanos en campos de concentración. Por último, los británicos también establecieron sus propias columnas de asalto montadas en apoyo de las columnas de barrido. Estas se utilizaron para seguir rápidamente y acosar implacablemente a los bóers con el fin de retrasarlos y cortarles la huida, mientras las unidades de barrido los alcanzaban. Muchas de las aproximadamente 90 columnas móviles formadas por los británicos para participar en tales ofensivas eran una mezcla de tropas británicas y coloniales, pero también tenían una gran minoría de africanos armados. Se ha estimado que el número total de africanos armados que servían en estas columnas era de 20.000.

El ejército británico también hizo uso de auxiliares bóeres que habían sido persuadidos a cambiar de bando y alistarse como " Scouts Nacionales ". Bajo el mando del general Andries Cronjé (1849-1923), los Scouts Nacionales eran despreciados como miembros de la coalición , pero llegaron a representar una quinta parte de los combatientes afrikáneres al final de la guerra. [75]

Los británicos utilizaron trenes blindados durante toda la guerra para enviar fuerzas de reacción rápida mucho más rápidamente a los incidentes (como los ataques bóer a fortines y columnas) o para dejarlas por delante de las columnas bóer en retirada.

Entre los burgueses que habían dejado de luchar, se decidió formar comités de paz para persuadir a los que todavía luchaban a que desistieran. En diciembre de 1900, Lord Kitchener autorizó la creación de un comité central de paz burgués en Pretoria. A finales de 1900, unos treinta enviados fueron enviados a los distintos distritos para formar comités de paz locales con el fin de persuadir a los burgueses a que abandonaran la lucha. Algunos líderes anteriores de los bóers, como los generales Piet de Wet y Andries Cronjé, participaron en la organización. Meyer de Kock fue el único emisario de un comité de paz que fue condenado por alta traición y ejecutado por un pelotón de fusilamiento. [76]

Algunos burgueses se unieron a los británicos en su lucha contra los bóers. Al final de las hostilidades en mayo de 1902, había no menos de 5.464 burgueses trabajando para los británicos. [77]

After having conferred with the Transvaal leaders, de Wet returned to the Orange Free State, where he inspired a series of successful attacks and raids in the western part of the country, though he suffered a rare defeat at Bothaville in November 1900. Many Boers who had earlier returned to their farms and towns, sometimes after being given formal parole by the British, took up arms again. In late January 1901, De Wet led a renewed invasion of Cape Colony. This was less successful, because there was no general uprising among the Cape Boers, and De Wet's men were hampered by bad weather and relentlessly pursued by British forces. They narrowly escaped across the Orange River.

From then until the final days of the war, De Wet remained comparatively quiet, rarely attacking British army camps and columns partly because the Orange Free State was effectively left desolate by British sweeps. In late 1901, De Wet overran an isolated British detachment at Groenkop, inflicting heavy casualties. This prompted Kitchener to launch the first of the "New Model" drives against him. De Wet escaped the first such drive but lost 300 of his fighters. This was a severe loss, and a portent of further attrition, although the subsequent attempts to round up De Wet were badly handled, and De Wet's forces avoided capture.

The Boer commandos in the Western Transvaal were very active after September 1901. Several battles of importance were fought there between September 1901 and March 1902. At Moedwil on 30 September 1901 and again at Driefontein on 24 October, General Koos De La Rey's forces attacked British camps and outposts but were forced to withdraw after the British offered strong resistance.

From late 1901 to early 1902, a time of relative quiet descended on the western Transvaal. February 1902 saw the next major battle in that region. On 25 February, De La Rey attacked a British column under Lieutenant-Colonel S. B. von Donop at Ysterspruit near Wolmaransstad. De La Rey succeeded in capturing many men and a large amount of ammunition. The Boer attacks prompted Lord Methuen, the British second-in-command after Kitchener, to move his column from Vryburg to Klerksdorp to deal with De La Rey. On the morning of 7 March 1902, the Boers attacked the rear guard of Methuen's moving column at Tweebosch. Confusion reigned in British ranks and Methuen was wounded and captured by the Boers.

The Boer victories in the west led to stronger action by the British. In the second half of March 1902, large British reinforcements were sent to the Western Transvaal under the direction of Ian Hamilton. The opportunity the British were waiting for arose on 11 April 1902 at Rooiwal, where a commando led by General Jan Kemp and Commandant Potgieter attacked a superior force under Kekewich. The British soldiers were well positioned on the hillside and inflicted severe casualties on the Boers charging on horseback over a large distance, beating them back. This was the end of the war in the Western Transvaal and also the last major battle of the war.

Two Boer forces fought in this area, one under Botha in the south east and a second under Ben Viljoen in the north east around Lydenburg. Botha's forces were particularly active, raiding railways and British supply convoys, and even mounting a renewed invasion of Natal in September 1901. After defeating British mounted infantry in the Battle of Blood River Poort near Dundee, Botha was forced to withdraw by heavy rains that made movement difficult and crippled his horses. Back on the Transvaal territory around his home district of Vryheid, Botha attacked a British raiding column at Bakenlaagte, using an effective mounted charge. One of the most active British units was effectively destroyed in this engagement. This made Botha's forces the target of increasingly large scorched earth drives by British forces, in which the British made particular use of native scouts and informers. Eventually, Botha had to abandon the high veld and retreat to a narrow enclave bordering Swaziland.

To the north, Ben Viljoen grew steadily less active. His forces mounted comparatively few attacks and as a result, the Boer enclave around Lydenburg was largely unmolested. Viljoen was eventually captured.

In parts of Cape Colony, particularly the Cape Midlands District where Boers formed a majority of the white inhabitants, the British had always feared a general uprising against them. In fact, no such uprising ever took place, even in the early days of the war when Boer armies had advanced across the Orange. The cautious conduct of some of the elderly Orange Free State generals had been one factor that discouraged the Cape Boers from siding with the Boer republics. Nevertheless, there was widespread pro-Boer sympathy. Some of the Cape Dutch volunteered to help the British, but a much larger number volunteered to help the other side. The political factor was more important than the military: the Cape Dutch, according to Milner 90 percent of whom favoured the rebels, controlled the provincial legislature, and it's authorities forbade the British Army to burn farms or to force Boer civilians into concentration camps.[78] The British had more limited options to suppress the insurgency in the Cape Colony as result.

After he escaped across the Orange in March 1901, de Wet had left forces under Cape rebels Kritzinger and Gideon Scheepers to maintain a guerrilla campaign in the Cape Midlands. The campaign here was one of the least chivalrous of the war, with intimidation by both sides of each other's civilian sympathisers. In one of many skirmishes, Commandant Johannes Lötter's small commando was tracked down by a much-superior British column and wiped out at Groenkloof. Several captured Boers, including Lotter and Scheepers, who was captured when he fell ill with appendicitis, were executed by the British for treason or for capital crimes such as the murder of British prisoners or of unarmed civilians. Some of the executions took place in public, to deter further disaffection.

Fresh Boer forces under Jan Christiaan Smuts, joined by the surviving rebels under Kritzinger, made another attack on the Cape in September 1901. They suffered severe hardships and were hard pressed by British columns, but eventually rescued themselves by routing some of their pursuers at the Battle of Elands River and capturing their equipment. From then until the end of the war, Smuts increased his forces from among Cape rebels until they numbered 3,000. However, no general uprising took place, and the situation in the Cape remained stalemated.

In January 1902, Boer leader Manie Maritz was implicated in the Leliefontein massacre in the far Northern Cape.

While no other government actively supported the Boer cause, individuals from several countries volunteered and formed Foreign Volunteer Units. These primarily came from Europe, particularly the Netherlands, Germany and Sweden-Norway. Other countries such as France, Italy, Ireland (then part of the United Kingdom), and restive areas of the Russian Empire, including Poland and Georgia, also formed smaller volunteer corps. Finns fought in the Scandinavian Corps. Two volunteers, George Henri Anne-Marie Victor de Villebois-Mareuil of France and Yevgeny Maximov of Russia, became veggeneraals (fighting generals) of the South African Republic.[79]

Towards the end of the war in the early months of 1902, British tactics of containment, denial, and harassment finally began to yield results against the Boer guerrillas. The sourcing and co-ordination of intelligence became increasingly efficient with regular reporting from observers in the blockhouses, from units patrolling the fences and conducting "sweeper" operations, and from native Africans in rural areas who increasingly supplied intelligence, as the Scorched Earth policy took effect and they found themselves competing with the Boers for food supplies. Kitchener's forces at last began to seriously affect the Boers' fighting strength and freedom of manoeuvre, and made it harder for the Boers and their families to survive. Despite this success, almost half the Boer fighting strength, around 15,000 men, were still in the field fighting by May 1902. However, Kitchener's tactics were very costly: Britain was running out of time, patience, and money needed for the war.[80]

The British offered terms of peace on various occasions, notably in March 1901, but were rejected by Botha and the "Bitter-enders" among the Boers. They pledged to fight until the bitter end and rejected the demand for compromise made by the "Hands-uppers". Their reasons included hatred of the British, loyalty to their dead comrades, solidarity with fellow commandos, an intense desire for independence, religious arguments, and fear of captivity or punishment. On the other hand, their women and children were dying nearly every day in prison camps and independence seemed more and more impossible.[81]

The last of the Boers finally surrendered in May 1902 and the war ended with the Treaty of Vereeniging signed on 31 May 1902. After a period of obstinacy, the British reneged and offered the Boers generous terms of conditional surrender in order to bring the war to a victorious conclusion. The Boers were given £3,000,000 for reconstruction and were promised eventual limited self-government, which was granted in 1906 and 1907. The treaty ended the existence of the Transvaal and Orange Free State as independent Boer republics and placed them within the British Empire. The Union of South Africa was established as a dominion of the British Empire in 1910.

The policy on both sides was to minimise the role of nonwhites, but the need for manpower continuously stretched those resolves. At the battle of Spion Kop in Ladysmith, Mohandas K. Gandhi with 300 free burgher Indians and 800 indentured Indian labourers started the Ambulance Corps serving the British side. As the war raged across African farms and their homes were destroyed, many became refugees and they, like the Boers, moved to the towns where the British hastily created internment camps. Subsequently, the British scorched earth policies were applied to both Boers and Africans. Although most black Africans were not considered by the British to be hostile, many tens of thousands were also forcibly removed from Boer areas and also placed in concentration camps.[citation needed] Africans were held separately from Boer internees.[citation needed] Eventually there were a total of 64 tented camps for Africans. Conditions were as bad as in the camps for the Boers, but even though, after the Fawcett Commission report, conditions improved in the Boer camps, "improvements were much slower in coming to the black camps"; 20,000 died there.[82]

The Boers and the British both feared the consequences of arming Africans. The memories of the Zulu and other tribal conflicts were still fresh, and they recognised that whoever won would have to deal with the consequences of a mass militarisation of the tribes. There was therefore an unwritten agreement that this war would be a "white man's war."[citation needed] At the outset, British officials instructed all white magistrates in the Natal Colony to appeal to Zulu amakhosi (chiefs) to remain neutral, and President Kruger sent emissaries asking them to stay out of it. However, in some cases there were old scores to be settled, and some Africans, such as the Swazis, were eager to enter the war with the specific aim of reclaiming land won by the Boers.[citation needed] As the war went on there was greater involvement of Africans, and in particular large numbers became embroiled in the conflict on the British side, either voluntarily or involuntarily. By the end of the war, many Africans had been armed and had shown conspicuous gallantry in roles such as scouts, messengers, watchmen in blockhouses, and auxiliaries.[citation needed]

And there were more flash points outside of the war. On 6 May 1902 at Holkrantz in the southeastern Transvaal, a Zulu faction had their cattle stolen and their women and children tortured by the Boers as a punishment for assisting the British. The local Boer officer then sent an insulting message to the tribe, challenging them to take back their cattle. The Zulus attacked at night, and in a mutual bloodbath, the Boers lost 56 killed and 3 wounded, while the Africans suffered 52 killed and 48 wounded.[21]: 601

About 10,000 black men were attached to Boer units where they performed camp duties; a handful unofficially fought in combat. The British Army employed over 14,000 Africans as wagon drivers. Even more had combatant roles as spies, guides, and eventually as soldiers. By 1902 there were about 30,000 armed Africans in the British Army.[83]

The term "concentration camp" was used to describe camps operated by the British in South Africa during this conflict in the years 1900–1902, and the term grew in prominence during this period.