La Segunda Enmienda ( Enmienda II ) a la Constitución de los Estados Unidos protege el derecho a poseer y portar armas . Fue ratificada el 15 de diciembre de 1791, junto con otros nueve artículos de la Carta de Derechos . [1] [2] [3] En District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), la Corte Suprema afirmó por primera vez que el derecho pertenece a los individuos, para la autodefensa en el hogar, [4] [5] [6] [7] al tiempo que también incluyó, como dicta , que el derecho no es ilimitado y no excluye la existencia de ciertas prohibiciones de larga data como las que prohíben "la posesión de armas de fuego por delincuentes y enfermos mentales" o restricciones sobre "el porte de armas peligrosas e inusuales". [8] [9] En McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010) la Corte Suprema dictaminó que los gobiernos estatales y locales están limitados en la misma medida que el gobierno federal a infringir este derecho. [10] [11] New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen (2022) aseguró el derecho a portar armas en espacios públicos con excepciones razonables.

La Segunda Enmienda se basó parcialmente en el derecho a poseer y portar armas en el derecho consuetudinario inglés y fue influenciada por la Declaración de Derechos inglesa de 1689. Sir William Blackstone describió este derecho como un derecho auxiliar, que apoyaba los derechos naturales de autodefensa y resistencia a la opresión, y el deber cívico de actuar en concierto en defensa del estado. [12] Si bien James Monroe y John Adams apoyaron la ratificación de la Constitución, su redactor más influyente fue James Madison . En Federalist No. 46 , Madison escribió cómo un ejército federal podría ser mantenido bajo control por la milicia, "un ejército permanente ... se enfrentaría [a] la milicia". Argumentó que los gobiernos estatales "podrían repeler el peligro" de un ejército federal, "bien puede dudarse de que una milicia en tales circunstancias pueda ser conquistada alguna vez por tal proporción de tropas regulares". Contrastó el gobierno federal de los Estados Unidos con los reinos europeos, a los que describió como "temerosos de confiar armas al pueblo", y aseguró que "la existencia de gobiernos subordinados ... forma una barrera contra las empresas de la ambición". [13] [14]

En enero de 1788, Delaware, Pensilvania, Nueva Jersey, Georgia y Connecticut ratificaron la Constitución sin insistir en que se hicieran enmiendas. Se propusieron varias enmiendas, pero no se adoptaron en el momento en que se ratificó la Constitución. Por ejemplo, la convención de Pensilvania debatió quince enmiendas, una de las cuales se refería al derecho del pueblo a estar armado y otra al de la milicia. La convención de Massachusetts también ratificó la Constitución con una lista adjunta de enmiendas propuestas. Al final, la convención de ratificación quedó tan dividida entre los que estaban a favor y los que estaban en contra de la Constitución que los federalistas aceptaron la Declaración de Derechos para asegurar la ratificación. En Estados Unidos contra Cruikshank (1876), la Corte Suprema dictaminó que "el derecho a portar armas no está garantizado por la Constitución; tampoco depende en modo alguno de ese instrumento para su existencia. La Segunda Enmienda [ sic ] no significa más que no debe ser infringida por el Congreso, y no tiene otro efecto que restringir los poderes del Gobierno Nacional". [15] En el caso de Estados Unidos contra Miller (1939), la Corte Suprema dictaminó que la Segunda Enmienda no protegía los tipos de armas que no tuvieran una "relación razonable con la preservación o la eficiencia de una milicia bien regulada". [16] [17]

En el siglo XXI, la enmienda ha sido objeto de una renovada investigación académica e interés judicial . [17] En District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), la Corte Suprema dictó una decisión histórica que sostuvo que la enmienda protege el derecho de un individuo a tener un arma para defensa propia. [18] [19] Esta fue la primera vez que la Corte dictaminó que la Segunda Enmienda garantiza el derecho de un individuo a poseer un arma. [20] [21] [19] En McDonald v. Chicago (2010), la Corte Suprema aclaró que la Cláusula del Debido Proceso de la Decimocuarta Enmienda incorporó la Segunda Enmienda contra los gobiernos estatales y locales. [22] En Caetano v. Massachusetts (2016), la Corte Suprema reiteró sus fallos anteriores de que "la Segunda Enmienda se extiende, prima facie, a todos los instrumentos que constituyen armas transportables, incluso aquellos que no existían en el momento de la fundación" y que su protección no se limita a "solo aquellas armas útiles en la guerra". Además de afirmar el derecho a portar armas de fuego en público, NYSRPA v. Bruen (2022) creó una nueva prueba según la cual las leyes que buscan limitar los derechos de la Segunda Enmienda deben basarse en la historia y la tradición de los derechos de armas, aunque la prueba se perfeccionó para centrarse en analogías similares y principios generales en lugar de coincidencias estrictas del pasado en United States v. Rahimi (2024). El debate entre varias organizaciones sobre el control de armas y los derechos de armas continúa. [23]

Existen varias versiones del texto de la Segunda Enmienda, cada una con diferencias en el uso de mayúsculas y puntuación. Existen diferencias entre la versión aprobada por el Congreso y publicada y las versiones ratificadas por los estados. [24] [25] [26] [27] Estas diferencias han sido el foco de debate en relación con el significado de la enmienda, en particular en relación con la importancia de lo que los tribunales han llamado la cláusula introductoria. [28] [29]

El original manuscrito final de la Declaración de Derechos tal como fue aprobada por el Congreso, con el resto del original preparado por el escriba William Lambert , se conserva en los Archivos Nacionales . [30] Esta es la versión ratificada por Delaware [31] y utilizada por la Corte Suprema en el caso Distrito de Columbia v. Heller : [32]

Siendo necesaria una milicia bien organizada para la seguridad de un Estado libre, no se violará el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas.

Algunas versiones ratificadas por los estados, como la de Maryland, omitieron la primera o la última coma: [31] [33] [25]

Siendo necesaria una milicia bien organizada para la seguridad de un Estado libre, no se violará el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas.

Las actas de ratificación de Nueva York, Pensilvania, Rhode Island y Carolina del Sur contenían sólo una coma, pero con diferencias en el uso de mayúsculas. La ley de Pensilvania establece: [34] [35] [36]

Siendo necesaria una milicia bien organizada para la seguridad de un Estado libre, no se violará el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas.

El acta de ratificación de Nueva Jersey no tiene comas: [31]

Siendo necesaria una milicia bien organizada para la seguridad de un Estado libre, no se violará el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas.

El derecho de los protestantes a portar armas en la historia inglesa se considera en el derecho consuetudinario inglés como un derecho auxiliar subordinado a los derechos primarios a la seguridad personal, la libertad personal y la propiedad privada. Según Sir William Blackstone , "El ... último derecho auxiliar del súbdito ... es el de tener armas para su defensa, adecuadas a su condición y grado, y tal como lo permite la ley. Lo cual está ... declarado por ... estatuto, y es de hecho una concesión pública, con las debidas restricciones, del derecho natural de resistencia y autoconservación, cuando las sanciones de la sociedad y las leyes se consideran insuficientes para restringir la violencia de la opresión". [37]

La Carta de Derechos inglesa de 1689 surgió de un período tempestuoso en la política inglesa durante el cual dos cuestiones fueron fuentes importantes de conflicto: la autoridad del rey para gobernar sin el consentimiento del Parlamento y el papel de los católicos en un país con una mayoría firmemente protestante. Finalmente, el católico Jacobo II fue derrocado en la Revolución Gloriosa , y sus sucesores, los protestantes Guillermo III y María II , aceptaron las condiciones que se codificaron en la ley. Una de las cuestiones que resolvió la ley fue la autoridad del rey para desarmar a sus súbditos, después de que Jacobo II hubiera desarmado a muchos protestantes que eran "sospechosos o conocidos" de desagradar al gobierno, [38] y habían discutido con el Parlamento sobre su deseo de mantener un ejército permanente. [a] El proyecto de ley afirma que está actuando para restaurar "derechos antiguos" pisoteados por Jacobo II, aunque algunos han argumentado que la Carta de Derechos inglesa creó un nuevo derecho a tener armas, que se desarrolló a partir de un deber de tener armas. [39] En el caso District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), la Corte Suprema no aceptó esta opinión, señalando que el derecho inglés en el momento de la aprobación de la Carta de Derechos Inglesa era "claramente un derecho individual, que no tenía nada que ver con el servicio en la milicia" y que era un derecho a no ser desarmado por la Corona y no era la concesión de un nuevo derecho a tener armas. [40]

El texto de la Carta de Derechos inglesa de 1689 incluye un lenguaje que protege el derecho de los protestantes contra el desarme por parte de la Corona , al afirmar: "Que los súbditos que son protestantes pueden tener armas para su defensa adecuadas a sus condiciones y según lo permita la ley". [41] También contenía un texto que aspiraba a vincular a los parlamentos futuros, aunque bajo la ley constitucional inglesa ningún parlamento puede vincular a ningún parlamento posterior. [42]

La declaración de la Carta de Derechos inglesa relativa al derecho a portar armas se cita a menudo sólo en el pasaje en el que está escrita como se indica más arriba y no en su contexto completo. En su contexto completo está claro que el proyecto de ley afirmaba el derecho de los ciudadanos protestantes a no ser desarmados por el rey sin el consentimiento del Parlamento y simplemente restauraba a los protestantes derechos que el rey anterior había eliminado brevemente e ilegalmente. En su contexto completo dice: [41]

Considerando que el difunto Rey Jaime II, con la ayuda de diversos consejeros, jueces y ministros malvados empleados por él, intentó subvertir y extirpar la religión protestante y las leyes y libertades de este reino (lista de agravios incluida) ... al hacer que varios buenos súbditos protestantes fueran desarmados al mismo tiempo que los papistas estaban armados y empleados en contra de la ley, (Recitado sobre el cambio de monarca) ... entonces los dichos Lores espirituales y temporales y los Comunes, de conformidad con sus respectivas cartas y elecciones, estando ahora reunidos en un pleno y libre representante de esta nación, tomando en su más seria consideración los mejores medios para alcanzar los fines antes mencionados, Doe en primer lugar (como sus antepasados en casos similares han hecho habitualmente) para reivindicar y afirmar sus antiguos derechos y libertades, declara (lista de derechos incluida) ... que los súbditos que son protestantes pueden tener armas para su defensa adecuadas a sus condiciones y según lo permita la ley.

El vínculo histórico entre la Carta de Derechos inglesa y la Segunda Enmienda, que codifican un derecho existente y no crean uno nuevo, ha sido reconocido por la Corte Suprema de Estados Unidos. [b] [c]

La Carta de Derechos inglesa incluye la condición de que las armas deben ser las "permitidas por la ley". Esto ha sido así antes y después de la aprobación de la Ley. Si bien no anuló las restricciones anteriores sobre la posesión de armas para la caza, está sujeta al derecho parlamentario de derogar implícita o explícitamente las disposiciones anteriores. [43]

Hay algunas diferencias de opinión sobre cuán revolucionarios fueron realmente los acontecimientos de 1688-89, y varios comentaristas señalan que las disposiciones de la Carta de Derechos inglesa no representaban leyes nuevas, sino que más bien establecían derechos existentes. Mark Thompson escribió que, aparte de determinar la sucesión, la Carta de Derechos inglesa hizo "poco más que establecer ciertos puntos de las leyes existentes y simplemente aseguró a los ingleses los derechos de los que ya estaban en posesión [ sic ]". [44] Antes y después de la Carta de Derechos inglesa, el gobierno siempre podía desarmar a cualquier individuo o clase de individuos que considerara peligroso para la paz del reino. [45] En 1765, Sir William Blackstone escribió los Comentarios sobre las leyes de Inglaterra, describiendo el derecho a tener armas en Inglaterra durante el siglo XVIII como un derecho auxiliar subordinado del súbdito que "también fue declarado" en la Carta de Derechos inglesa. [37] [46] [47] [48]

El quinto y último derecho auxiliar del súbdito, que mencionaré ahora, es el de tener armas para su defensa, adecuadas a su condición y grado, y las que le permita la ley. Lo cual también se declara en el mismo estatuto 1 W. & M. st.2. c.2. y es, en verdad, una concesión pública, con las debidas restricciones, del derecho natural de resistencia y autoconservación, cuando las sanciones de la sociedad y las leyes se consideran insuficientes para restringir la violencia de la opresión .

Aunque no hay duda de que los autores de la Segunda Enmienda estuvieron muy influidos por la Carta de Derechos inglesa, es una cuestión de interpretación si su intención era preservar el poder de regular las armas para los estados por encima del gobierno federal (como el Parlamento inglés se había reservado para sí mismo contra el monarca) o si su intención era crear un nuevo derecho similar al derecho de los demás incluido en la Constitución (como decidió la Corte Suprema en Heller ). Algunos en los Estados Unidos han preferido el argumento de los "derechos" argumentando que la Carta de Derechos inglesa había otorgado un derecho. La necesidad de tener armas para la autodefensa no estaba realmente en cuestión. Los pueblos de todo el mundo desde tiempos inmemoriales se habían armado para la protección de sí mismos y de los demás, y a medida que comenzaron a aparecer naciones organizadas, estos acuerdos se habían extendido a la protección del estado. Por ejemplo, la Assize of Arms del rey Enrique II y el Estatuto de Winchester de 1285. Véase: "La historia de la policía en Occidente, la responsabilidad colectiva en los primeros tiempos anglosajones". Encyclopædia Britannica (edición en línea). Archivado desde el original el 7 de junio de 2009.</ref> Sin un ejército regular ni una fuerza policial, había sido el deber de ciertos hombres mantener la guardia y la vigilancia durante la noche y enfrentarse y capturar a las personas sospechosas. Cada súbdito tenía la obligación de proteger la paz del rey y ayudar a reprimir los disturbios. [49]

En 1757, el Parlamento de Gran Bretaña creó "Una ley para un mejor ordenamiento de las fuerzas de la milicia en los diversos condados de esa parte de Gran Bretaña llamada Inglaterra". [50] Esta ley declaró que "una milicia bien ordenada y bien disciplinada es esencialmente necesaria para la seguridad, la paz y la prosperidad de este reino", y que las leyes de milicia actuales para la regulación de la milicia eran defectuosas e ineficaces. Influenciado por esta ley, en 1775 Timothy Pickering creó "Un plan fácil de disciplina para una milicia". [51] Muy inhibido por los eventos que rodearon a Salem, Massachusetts , donde se imprimió el plan, Pickering presentó el escrito a George Washington . [52] El 1 de mayo de 1776, el Consejo de la Bahía de Massachusetts resolvió que la disciplina de Pickering, una modificación de la ley de 1757, fuera la disciplina de su milicia. [53] El 29 de marzo de 1779, para los miembros del Ejército Continental esto fue reemplazado por las Regulaciones de Von Steuben para el Orden y Disciplina de las Tropas de los Estados Unidos . [54] Con la ratificación de la Segunda Enmienda, después del 8 de mayo de 1792, toda la Milicia de los Estados Unidos, salvo dos declaraciones, estaría regulada por la Disciplina de Von Steuben. [55]

El rey Carlos I autorizó el uso de armas para especial defensa y seguridad, en tierra y en el mar, contra:

La Compañía Militar de Massachusetts ya había pedido municiones antes de que se firmara la autorización. Los primeros estadounidenses tenían otros usos para las armas, además de los que el rey Carlos tenía en mente: [d] [e] [ 58] [59] [60] [61] [62] [63]

No se sabe cuál de estas consideraciones se consideró más importante y finalmente se expresó en la Segunda Enmienda. Algunos de estos propósitos se mencionaron explícitamente en las primeras constituciones estatales; por ejemplo, la Constitución de Pensilvania de 1776 afirmó que "el pueblo tiene derecho a portar armas para su propia defensa y la del estado". [70]

Durante el período prerrevolucionario de la década de 1760, la milicia colonial establecida estaba compuesta por colonos, incluidos muchos que eran leales al gobierno británico . A medida que se desarrolló el desafío y la oposición al gobierno británico, la desconfianza hacia estos leales en la milicia se generalizó entre los colonos conocidos como patriotas , que favorecían la independencia del gobierno británico. Como resultado, algunos patriotas crearon sus propias milicias que excluían a los leales y luego buscaron abastecer armerías independientes para sus milicias. En respuesta a esta acumulación de armas, el Parlamento británico estableció un embargo de armas de fuego, piezas y municiones contra las colonias estadounidenses [71] que en algunos casos llegó a denominarse " alarmas de pólvora" . El rey Jorge III también comenzó a desarmar a las personas que se encontraban en las áreas más rebeldes en las décadas de 1760 y 1770. [72]

Los esfuerzos británicos y leales para desarmar los arsenales de la milicia patriota colonial en las primeras fases de la Revolución estadounidense dieron como resultado que los colonos patriotas protestaran citando la Declaración de Derechos , el resumen de Blackstone de la Declaración de Derechos, sus propias leyes de milicia y los derechos de derecho consuetudinario a la legítima defensa . [73] Si bien la política británica en las primeras fases de la Revolución claramente apuntaba a prevenir la acción coordinada de la milicia patriota, algunos han argumentado que no hay evidencia de que los británicos buscaran restringir el derecho tradicional de derecho consuetudinario a la legítima defensa. [73] Patrick J. Charles disputa estas afirmaciones citando un desarme similar por parte de los patriotas y desafiando la interpretación de Blackstone de esos académicos. [74]

El derecho de los colonos a las armas y a la rebelión contra la opresión fue afirmado, por ejemplo, en un editorial de un periódico prerrevolucionario en 1769, en el que se objetaba la supresión por parte de la Corona de la oposición colonial a las Leyes de Townshend : [73] [75]

Todavía se multiplican ante nosotros los ejemplos de la conducta licenciosa y escandalosa de los conservadores militares de la paz, algunos de los cuales son de tal naturaleza y han sido llevados a tales extremos que deben servir para demostrar plenamente que una votación tardía de esta ciudad, instando a sus habitantes a proveerse de armas para su defensa, fue una medida tan prudente como legal: siempre se debe temer este tipo de violencias por parte de las tropas militares cuando están acuarteladas en el cuerpo de una ciudad populosa; pero más especialmente, cuando se les hace creer que son necesarias para amedrentar un espíritu de rebelión, que injuriosamente se dice que existe en ella. Es un derecho natural que el pueblo se ha reservado, confirmado por la Declaración de Derechos, el de tener armas para su propia defensa; y como observa el Sr. Blackstone, se debe hacer uso de él cuando las sanciones de la sociedad y la ley se consideran insuficientes para restringir la violencia de la opresión.

Las fuerzas armadas que ganaron la Revolución estadounidense consistieron en el Ejército Continental permanente creado por el Congreso Continental , junto con el ejército regular francés y las fuerzas navales y varias unidades de milicias estatales y regionales. En la oposición, las fuerzas británicas consistieron en una mezcla del Ejército británico permanente , la milicia leal y los mercenarios de Hesse . Después de la Revolución, Estados Unidos fue gobernado por los Artículos de la Confederación . Los federalistas argumentaron que este gobierno tenía una división de poder inviable entre el Congreso y los estados, lo que causó debilidad militar, ya que el ejército permanente se redujo a tan solo 80 hombres. [76] Consideraron que era malo que no hubiera una represión militar federal efectiva contra una rebelión fiscal armada en el oeste de Massachusetts conocida como la Rebelión de Shays . [77] Los antifederalistas, por otro lado, tomaron el lado del gobierno limitado y simpatizaron con los rebeldes, muchos de los cuales eran ex soldados de la Guerra de la Independencia. Posteriormente, la Convención Constitucional propuso en 1787 otorgar al Congreso poder exclusivo para crear y mantener un ejército y una marina permanentes de tamaño ilimitado. [78] [79] Los antifederalistas se opusieron al cambio de poder de los estados al gobierno federal, pero a medida que la adopción de la Constitución se hizo cada vez más probable, cambiaron su estrategia para establecer una declaración de derechos que pondría algunos límites al poder federal. [80]

Los académicos modernos Thomas B. McAffee y Michael J. Quinlan han afirmado que James Madison "no inventó el derecho a poseer y portar armas cuando redactó la Segunda Enmienda; el derecho ya existía tanto en el derecho consuetudinario como en las primeras constituciones estatales". [81] Por el contrario, el historiador Jack Rakove sugiere que la intención de Madison al redactar la Segunda Enmienda era dar garantías a los antifederalistas moderados de que las milicias no serían desarmadas. [82]

Un aspecto del debate sobre el control de armas es el conflicto entre las leyes de control de armas y el derecho a rebelarse contra gobiernos injustos. Blackstone, en sus Comentarios, aludió a este derecho a rebelarse como el derecho natural de resistencia y autopreservación, que debe utilizarse sólo como último recurso, ejercible cuando "las sanciones de la sociedad y las leyes se consideren insuficientes para frenar la violencia de la opresión". [37] Algunos creen que los redactores de la Carta de Derechos buscaron equilibrar no sólo el poder político, sino también el poder militar, entre el pueblo, los estados y la nación, [83] como explicó Alexander Hamilton en su ensayo " Sobre la milicia ", publicado en 1788: [83] [84]

... será posible contar con un excelente cuerpo de milicianos bien entrenados, listos para entrar en acción siempre que la defensa del Estado lo requiera. Esto no sólo disminuirá la necesidad de establecimientos militares, sino que, si en algún momento las circunstancias obligaran al Gobierno a formar un ejército de cualquier magnitud, ese ejército nunca podrá ser formidable para las libertades del pueblo mientras haya un gran cuerpo de ciudadanos, poco o nada inferiores a ellos en disciplina y en el uso de las armas, que estén listos para defender sus propios derechos y los de sus conciudadanos. Este me parece el único sustituto que puede idearse para un ejército permanente y la mejor seguridad posible contra él, si llegara a existir.

En 1789 se debatió si "el pueblo" luchaba contra la tiranía gubernamental (como lo describieron los antifederalistas) o si "el pueblo" corría el riesgo de un gobierno de masas (como lo describieron los federalistas) en relación con la cada vez más violenta Revolución Francesa . [85] Durante los debates sobre la ratificación de la Constitución, un temor generalizado era la posibilidad de que el gobierno federal tomara el control militar de los estados, lo que podría suceder si el Congreso aprobaba leyes que prohibieran a los estados armar a los ciudadanos, [f] o que prohibieran a los ciudadanos armarse a sí mismos. [73] Aunque se ha argumentado que los estados perdieron el poder de armar a sus ciudadanos cuando el poder de armar a la milicia fue transferido de los estados al gobierno federal por el Artículo I, Sección 8 de la Constitución, el derecho individual a armarse fue retenido y fortalecido por las Leyes de Milicia de 1792 y la ley similar de 1795. [86] [87]

Más recientemente, algunos han propuesto lo que se ha llamado la teoría insurreccional de la Segunda Enmienda, según la cual todo ciudadano tiene derecho a tomar las armas contra su gobierno si lo considera ilegítimo. Esta interpretación ha sido expresada por organizaciones como la Asociación Nacional del Rifle de Estados Unidos (NRA) [88] y por varias personas, incluidos algunos funcionarios electos. [89] Sin embargo, el congresista Jamie Raskin ha argumentado que no hay base en el derecho constitucional ni en la erudición para esta opinión. [90] Señala que esto no sólo representa una lectura errónea del texto de la Enmienda tal como está redactada, sino que viola otros elementos de la Constitución. [90]

En marzo de 1785, los delegados de Virginia y Maryland se reunieron en la Conferencia de Mount Vernon para idear un remedio a las ineficiencias de los Artículos de la Confederación. Al año siguiente, en una reunión en Annapolis, Maryland , 12 delegados de cinco estados ( Nueva Jersey , Nueva York , Pensilvania , Delaware y Virginia ) se reunieron y elaboraron una lista de problemas con el modelo de gobierno actual. Al concluir, los delegados programaron una reunión de seguimiento en Filadelfia , Pensilvania, para mayo de 1787 para presentar soluciones a estos problemas, como la ausencia de: [105] [106]

Pronto se hizo evidente que la solución a estos tres problemas requería transferir el control de las milicias de los estados al Congreso federal y darle el poder de formar un ejército permanente. [107] El Artículo 1, Sección 8 de la Constitución codificó estos cambios al permitir que el Congreso provea para la defensa común y el bienestar general de los Estados Unidos haciendo lo siguiente: [108]

Algunos representantes desconfiaban de las propuestas de ampliar los poderes federales, porque les preocupaban los riesgos inherentes a la centralización del poder. Los federalistas , incluido James Madison , argumentaron inicialmente que una carta de derechos era innecesaria, suficientemente confiados en que el gobierno federal nunca podría reunir un ejército permanente lo suficientemente poderoso como para vencer a una milicia. [109] El federalista Noah Webster argumentó que una población armada no tendría problemas para resistir la amenaza potencial a la libertad de un ejército permanente. [110] [111] Los antifederalistas , por otro lado, abogaron por enmendar la Constitución con derechos claramente definidos y enumerados que proporcionaran restricciones más explícitas al nuevo gobierno. Muchos antifederalistas temían que el nuevo gobierno federal optara por desarmar a las milicias estatales. Los federalistas respondieron que al enumerar solo ciertos derechos, los derechos no enumerados podrían perder protección. Los federalistas se dieron cuenta de que no había suficiente apoyo para ratificar la Constitución sin una carta de derechos y, por lo tanto, prometieron apoyar la enmienda de la Constitución para agregar una carta de derechos después de la adopción de la Constitución. Este compromiso convenció a suficientes antifederalistas para que votaran a favor de la Constitución, lo que permitió su ratificación. [112] La Constitución fue declarada ratificada el 21 de junio de 1788, cuando nueve de los trece estados originales la habían ratificado. Los cuatro estados restantes siguieron su ejemplo más tarde, aunque los dos últimos estados, Carolina del Norte y Rhode Island, ratificaron solo después de que el Congreso hubiera aprobado la Declaración de Derechos y la hubiera enviado a los estados para su ratificación. [113] James Madison redactó lo que finalmente se convirtió en la Declaración de Derechos, que fue propuesta por el primer Congreso el 8 de junio de 1789 y adoptada el 15 de diciembre de 1791.

El debate en torno a la ratificación de la Constitución es de importancia práctica, en particular para los partidarios de las teorías jurídicas originalistas y estrictamente constructivistas . En el contexto de esas teorías jurídicas y en otros ámbitos, es importante entender el lenguaje de la Constitución en términos de lo que ese lenguaje significaba para quienes la escribieron y ratificaron. [114]

Robert Whitehill , un delegado de Pensilvania, intentó aclarar el proyecto de Constitución con una declaración de derechos que otorgaba explícitamente a los individuos el derecho a cazar en sus propias tierras durante la temporada, [115] aunque el lenguaje de Whitehill nunca fue debatido. [116]

La nueva Constitución suscitó una oposición sustancial porque trasladaba el poder de armar a las milicias estatales de los estados al gobierno federal. Esto creó el temor de que el gobierno federal, al descuidar el mantenimiento de la milicia, pudiera disponer de una fuerza militar abrumadora gracias a su poder para mantener un ejército y una marina permanentes, lo que llevaría a una confrontación con los estados, invadiendo los poderes reservados de los estados e incluso participando en un golpe militar. El artículo VI de los Artículos de la Confederación establece: [117] [118]

Ningún Estado mantendrá en tiempo de paz ningún buque de guerra, excepto en el número que los Estados Unidos, reunidos en Congreso, consideren necesario para la defensa de dicho Estado o de su comercio; ni ningún Estado mantendrá en tiempo de paz ningún cuerpo de fuerzas, excepto en el número que, a juicio de los Estados Unidos, reunidos en Congreso, se considere necesario para guarnecer los fuertes necesarios para la defensa de dicho Estado; pero cada Estado mantendrá siempre una milicia bien regulada y disciplinada, suficientemente armada y pertrechada, y proporcionará y tendrá constantemente lista para su uso, en almacenes públicos, una cantidad debida de piezas de campaña y tiendas de campaña, y una cantidad apropiada de armas, municiones y equipo de campamento.

En cambio, el Artículo I, Sección 8, Cláusula 16 de la Constitución de los Estados Unidos establece: [119]

Para organizar, armar y disciplinar a la milicia, y para gobernar la parte de ella que pueda emplearse al servicio de los Estados Unidos, reservando a los estados respectivamente el nombramiento de los oficiales y la autoridad para entrenar a la milicia de acuerdo con la disciplina prescrita por el Congreso.

Una de las bases del pensamiento político estadounidense durante el período revolucionario fue la preocupación por la corrupción política y la tiranía gubernamental. Incluso los federalistas, al defenderse de sus oponentes que los acusaban de crear un régimen opresivo, tuvieron cuidado de reconocer los riesgos de la tiranía. En ese contexto, los redactores de la Constitución vieron el derecho personal a portar armas como un posible freno a la tiranía. Theodore Sedgwick de Massachusetts expresó este sentimiento al declarar que es "una idea quimérica suponer que un país como este podría ser esclavizado ... ¿Es posible ... que se pueda formar un ejército con el propósito de esclavizarse a sí mismos o a sus hermanos? O, si se forma, ¿podrían someter a una nación de hombres libres, que saben apreciar la libertad y que tienen armas en sus manos?" [120] Noah Webster argumentó de manera similar: [13] [121]

Antes de que un ejército permanente pueda gobernar, el pueblo debe estar desarmado, como ocurre en casi todos los reinos de Europa. El poder supremo en América no puede imponer leyes injustas por la espada, porque todo el pueblo está armado y constituye una fuerza superior a cualquier grupo de tropas regulares que pueda, bajo cualquier pretexto, reclutarse en los Estados Unidos.

George Mason también defendió la importancia de la milicia y el derecho a portar armas recordando a sus compatriotas los esfuerzos del gobierno británico "para desarmar al pueblo; que era la mejor y más eficaz manera de esclavizarlo ... desmantelando y descuidando totalmente la milicia". También aclaró que, según la práctica imperante, la milicia incluía a todas las personas, ricas y pobres. "¿Quiénes son la milicia? Ahora están formadas por todo el pueblo, excepto unos pocos funcionarios públicos". Como todos eran miembros de la milicia, todos disfrutaban del derecho a portar armas individualmente para servir en ella. [13] [122]

Escribiendo después de la ratificación de la Constitución, pero antes de la elección del primer Congreso, James Monroe incluyó "el derecho a poseer y portar armas" en una lista de "derechos humanos" básicos, que propuso que se añadieran a la Constitución. [123]

Patrick Henry defendió en la convención de ratificación de Virginia el 5 de junio de 1788 el doble derecho a las armas y a la resistencia a la opresión: [124]

Guardad con celosa atención la libertad pública. Sospechad de todo aquel que se acerque a esa joya. Desgraciadamente, nada podrá preservarla excepto la fuerza pura y simple. Cuando renunciáis a ella, estáis inevitablemente arruinados.

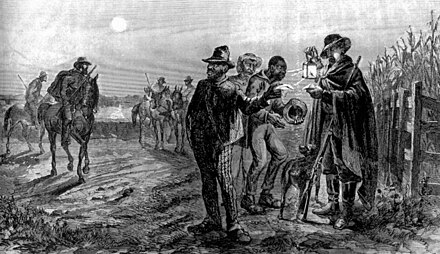

En los estados esclavistas , la milicia estaba disponible para operaciones militares, pero su función más importante era la de vigilar a los esclavos. [125] [126] Según el Dr. Carl T. Bogus , Profesor de Derecho de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Roger Williams en Rhode Island, [125] la Segunda Enmienda fue escrita para asegurar a los estados del Sur que el Congreso no socavaría el sistema esclavista utilizando su recién adquirida autoridad constitucional sobre la milicia para desarmar a la milicia estatal y, de ese modo, destruir el principal instrumento de control de esclavos del Sur. [127] En su análisis minucioso de los escritos de James Madison , Bogus describe la obsesión del Sur con las milicias durante el proceso de ratificación: [127]

La milicia siguió siendo el principal medio de proteger el orden social y preservar el control blanco sobre una enorme población negra. Cualquier cosa que pudiera debilitar este sistema representaba la más grave de las amenazas.

Esta preocupación quedó claramente expresada en 1788 [127] por el esclavista Patrick Henry : [125]

Si un país es invadido, un estado puede ir a la guerra, pero no puede reprimir insurrecciones [según esta nueva Constitución]. Si se produjera una insurrección de esclavos, no se puede decir que el país haya sido invadido. Por lo tanto, no pueden reprimirla sin la interposición del Congreso... El Congreso, y sólo el Congreso [según esta nueva Constitución; adición no mencionada en la fuente], puede convocar a la milicia.

Por lo tanto, Bogus argumenta que, en un compromiso con los estados esclavistas, y para asegurar a Patrick Henry, George Mason y otros propietarios de esclavos de que podrían mantener sus milicias de control de esclavos independientes del gobierno federal, James Madison (también propietario de esclavos) reformuló la Segunda Enmienda en su forma actual "con el propósito específico de asegurar a los estados del Sur, y particularmente a sus electores en Virginia, que el gobierno federal no socavaría su seguridad contra la insurrección de esclavos desarmando a la milicia". [127]

El historiador legal Paul Finkelman sostiene que este escenario es inverosímil. [68] Henry y Mason eran enemigos políticos de Madison, y ninguno de los dos estaba en el Congreso en el momento en que Madison redactó la Declaración de Derechos; además, Patrick Henry argumentó en contra de la ratificación tanto de la Constitución como de la Segunda Enmienda, y fue la oposición de Henry la que llevó al estado natal de Patrick, Virginia, a ser el último en ratificarla. [68]

La mayoría de los hombres blancos sureños de entre 18 y 45 años debían servir en " patrullas de esclavos ", que eran grupos organizados de hombres blancos que imponía disciplina a los negros esclavizados. [128] Bogus escribe con respecto a las leyes de Georgia aprobadas en 1755 y 1757 en este contexto: "Los estatutos de Georgia exigían que las patrullas, bajo la dirección de oficiales de milicia comisionados, examinaran cada plantación cada mes y las autorizaban a registrar 'todas las casas de negros en busca de armas y municiones ofensivas' y a detener y dar veinte latigazos a cualquier esclavo que se encontrara fuera de los terrenos de la plantación". [129] [130] [ fuente no confiable ]

Finkelman reconoce que James Madison "redactó una enmienda para proteger el derecho de los estados a mantener sus milicias", pero insiste en que "la enmienda no tenía nada que ver con los poderes policiales estatales, que eran la base de las patrullas de esclavos". [68]

En primer lugar, los dueños de esclavos temían que los esclavos negros pudieran emanciparse mediante el servicio militar. Unos años antes, había existido un precedente cuando Lord Dunmore ofreció la libertad a los esclavos que escaparon y se unieron a sus fuerzas con la leyenda "Libertad para los esclavos" cosida en las solapas de los bolsillos de sus chaquetas. [131] Los esclavos liberados también sirvieron en el ejército del general Washington .

En segundo lugar, también temían mucho "una ruinosa rebelión de esclavos en la que sus familias serían masacradas y sus propiedades destruidas". Cuando Virginia ratificó la Declaración de Derechos el 15 de diciembre de 1791, la Revolución Haitiana , una rebelión de esclavos exitosa, estaba en marcha. Por lo tanto, el esclavista y principal redactor de la Enmienda, James Madison , vinculó deliberadamente el derecho a portar armas a la membresía en una milicia , porque solo los blancos podían unirse a las milicias en el Sur. [132]

En 1776, Thomas Jefferson había presentado un proyecto de constitución para Virginia que decía que "a ningún hombre libre se le prohibirá jamás el uso de armas dentro de sus propias tierras o tenencias". Según Picadio, esta versión fue rechazada porque "habría otorgado a los negros libres el derecho constitucional a tener armas de fuego". [133]

La propuesta inicial de James Madison para una declaración de derechos se llevó a la Cámara de Representantes el 8 de junio de 1789, durante la primera sesión del Congreso. El pasaje propuesto inicialmente en relación con las armas era el siguiente: [134]

No se violará el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas; una milicia bien armada y bien organizada es la mejor seguridad de un país libre; pero ninguna persona religiosamente escrupulosa en cuanto a portar armas será obligada a prestar el servicio militar en persona.

El 21 de julio, Madison volvió a plantear la cuestión de su proyecto de ley y propuso que se creara un comité selecto para que informara sobre él. La Cámara votó a favor de la moción de Madison, [135] y la Carta de Derechos entró en el comité para su revisión. El comité devolvió a la Cámara una versión reformulada de la Segunda Enmienda el 28 de julio. [136] El 17 de agosto, esa versión fue leída en el Diario : [137]

Siendo una milicia bien organizada, compuesta por el cuerpo del pueblo, la mejor seguridad de un Estado libre, no se violará el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas; pero ninguna persona religiosamente escrupulosa será obligada a portar armas.

A fines de agosto de 1789, la Cámara de Representantes debatió y modificó la Segunda Enmienda. Estos debates giraron principalmente en torno al riesgo de una "mala administración del gobierno" al utilizar la cláusula de "escrupulosidad religiosa" para destruir a la milicia, tal como las fuerzas británicas habían intentado destruir a la milicia patriota al comienzo de la Revolución estadounidense . Estas preocupaciones se abordaron modificando la cláusula final y, el 24 de agosto, la Cámara de Representantes envió la siguiente versión al Senado:

Siendo una milicia bien organizada, compuesta del cuerpo del pueblo, la mejor seguridad de un estado libre, no se violará el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas; pero nadie que tenga escrúpulos religiosos en cuanto a portar armas será obligado a prestar el servicio militar en persona.

Al día siguiente, 25 de agosto, el Senado recibió la enmienda de la Cámara y la ingresó en el Diario del Senado. Sin embargo, el escribano del Senado agregó una coma antes de "no se infringirá" y cambió el punto y coma que separa esa frase de la parte de exención religiosa por una coma: [138]

Siendo una milicia bien organizada, compuesta del cuerpo del pueblo, la mejor seguridad de un estado libre, el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas no será violado, pero nadie que tenga escrúpulos religiosos en cuanto a portar armas será obligado a prestar el servicio militar en persona.

En ese momento, el derecho propuesto a poseer y portar armas se encontraba en una enmienda separada, en lugar de estar en una enmienda única junto con otros derechos propuestos, como el derecho al debido proceso. Como explicó un representante, este cambio permitió que cada enmienda "fuera aprobada por los estados de manera distinta". [139] El 4 de septiembre, el Senado votó para cambiar el lenguaje de la Segunda Enmienda eliminando la definición de milicia y eliminando la cláusula de objetor de conciencia: [140]

Una milicia bien organizada, siendo la mejor seguridad de un estado libre, no deberá violarse el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas.

El Senado volvió a tratar esta enmienda por última vez el 9 de septiembre. Una propuesta para insertar las palabras "para la defensa común" junto a las palabras "llevar armas" fue rechazada. Se aprobó una moción para reemplazar las palabras "lo mejor" e insertar en su lugar "necesario para". [141] El Senado modificó entonces ligeramente el texto para que se leyera como el cuarto artículo y votó por devolver la Declaración de Derechos a la Cámara. La versión final del Senado fue enmendada para que se leyera como sigue:

Siendo necesaria una milicia bien organizada para la seguridad de un estado libre, no se violará el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas.

La Cámara votó el 21 de septiembre de 1789 para aceptar los cambios realizados por el Senado.

La Resolución Conjunta original aprobada por el Congreso el 25 de septiembre de 1789, que se exhibe permanentemente en la Rotonda, dice lo siguiente: [142]

Siendo necesaria una milicia bien organizada para la seguridad de un Estado libre, no se violará el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas.

El 15 de diciembre de 1791 se adoptó la Declaración de Derechos (las primeras diez enmiendas a la Constitución), que fue ratificada por tres cuartas partes de los estados, y fue ratificada en grupo por los catorce estados que existían en ese momento, excepto Connecticut, Massachusetts y Georgia, que añadieron ratificaciones en 1939. [143]

Durante las dos primeras décadas posteriores a la ratificación de la Segunda Enmienda, la oposición pública a los ejércitos permanentes, tanto entre los antifederalistas como entre los federalistas, persistió y se manifestó localmente como una renuencia general a crear una fuerza policial armada profesional, y en su lugar se confió en los alguaciles del condado, los agentes de policía y los serenos para hacer cumplir las ordenanzas locales. [71] Aunque a veces se compensaban, a menudo estos puestos no eran remunerados: se desempeñaban como una cuestión de deber cívico. En estas primeras décadas, los agentes de la ley rara vez estaban armados con armas de fuego, y utilizaban porras como sus únicas armas defensivas. [71] En emergencias graves, un posse comitatus , una compañía de milicia o un grupo de vigilantes asumían las funciones de aplicación de la ley; era más probable que estos individuos estuvieran armados con armas de fuego que el alguacil local. [71]

El 8 de mayo de 1792, el Congreso aprobó "[u]na ley para proveer de manera más eficaz a la Defensa Nacional, estableciendo una Milicia Uniforme en todos los Estados Unidos" que requería: [144]

[C]ada uno y todo ciudadano varón blanco, libre y físicamente apto, de los respectivos Estados, residente en los mismos, que sea o vaya a ser mayor de dieciocho años, y menor de cuarenta y cinco años (excepto como se exceptúa a continuación) deberá, individual y respectivamente, ser alistado en la milicia ... [y] todo ciudadano así alistado y notificado, deberá, dentro de los seis meses siguientes, proveerse de un buen mosquete o escopeta , una bayoneta y un cinturón suficientes, dos pedernales de repuesto y una mochila, una bolsa con una caja en su interior para contener no menos de veinticuatro cartuchos, adecuados al calibre de su mosquete o escopeta, cada cartucho para contener una cantidad apropiada de pólvora y bala; o de un buen rifle, mochila, bolsa de perdigones y cuerno de pólvora, veinte balas adecuadas al calibre de su rifle, y un cuarto de libra de pólvora; y deberá presentarse así armado, equipado y provisto, cuando sea llamado a hacer ejercicio o a prestar servicio, excepto que cuando sea llamado en días de empresa sólo para hacer ejercicio, podrá presentarse sin mochila.

La ley también dio instrucciones específicas a los fabricantes de armas nacionales "que a partir de los cinco años siguientes a la aprobación de esta ley, los mosquetes para armar a la milicia como se requiere en la presente deberán tener un calibre suficiente para balas de la dieciochoava parte de una libra". [144] En la práctica, la adquisición y el mantenimiento privados de rifles y mosquetes que cumplieran las especificaciones y estuvieran disponibles para el servicio de la milicia resultaron problemáticos; las estimaciones de cumplimiento oscilaban entre el 10 y el 65 por ciento. [145] El cumplimiento de las disposiciones de inscripción también fue deficiente. Además de las exenciones otorgadas por la ley para los funcionarios de aduanas y sus empleados, los funcionarios de correos y los conductores de diligencias empleados en el cuidado y transporte del correo estadounidense, los barqueros, los inspectores de exportaciones, los pilotos, los marineros mercantes y aquellos desplegados en el mar en servicio activo; las legislaturas estatales otorgaron numerosas exenciones en virtud de la Sección 2 de la Ley, incluidas exenciones para: clérigos, objetores de conciencia, maestros, estudiantes y jurados. Aunque algunos hombres blancos sanos seguían disponibles para el servicio, muchos simplemente no se presentaban a cumplir con su deber en la milicia. Las sanciones por no presentarse se aplicaban de forma esporádica y selectiva. [146] No se menciona ninguna de ellas en la legislación. [144]

La primera prueba del sistema de milicias se produjo en julio de 1794, cuando un grupo de granjeros descontentos de Pensilvania se rebeló contra los recaudadores de impuestos federales, a quienes consideraban herramientas ilegítimas del poder tiránico. [147] Los intentos de los cuatro estados vecinos de formar una milicia para la nacionalización con el fin de reprimir la insurrección resultaron insuficientes. Cuando los funcionarios recurrieron al reclutamiento de hombres, se enfrentaron a una resistencia enconada. Los soldados que se incorporaron consistieron principalmente en reclutas o sustitutos pagados, así como en reclutas pobres atraídos por las bonificaciones por alistamiento. Los oficiales, sin embargo, eran de mayor calidad, respondían por un sentido del deber cívico y el patriotismo, y en general eran críticos con la tropa. [71] La mayoría de los 13.000 soldados carecían del armamento necesario; el departamento de guerra proporcionó armas a casi dos tercios de ellos. [71] En octubre, el presidente George Washington y el general Harry Lee marcharon contra los 7.000 rebeldes que se rindieron sin luchar. El episodio provocó críticas a la milicia ciudadana e inspiró llamamientos a favor de una milicia universal. El secretario de Guerra Henry Knox y el vicepresidente John Adams habían presionado al Congreso para que estableciera armerías federales para almacenar armas importadas y fomentar la producción nacional. [71] Posteriormente, el Congreso aprobó "[u]na ley para la construcción y reparación de arsenales y polvorines" el 2 de abril de 1794, dos meses antes de la insurrección. [148] Sin embargo, la milicia siguió deteriorándose y veinte años después, su mala condición contribuyó a varias pérdidas en la Guerra de 1812 , incluido el saqueo de Washington, DC, y el incendio de la Casa Blanca en 1814. [146]

En el siglo XX, el Congreso aprobó la Ley de Milicias de 1903. La ley definió a la milicia como todo varón físicamente apto de entre 18 y 44 años que fuera ciudadano o tuviera intención de convertirse en ciudadano. La ley dividió a la milicia en la Guardia Nacional de los Estados Unidos y la Milicia de Reserva no organizada. [149] [150]

La ley federal sigue definiendo a la milicia como todos los varones sanos de 17 a 44 años de edad que sean ciudadanos o tengan intención de convertirse en ciudadanos, y las ciudadanas que sean miembros de la Guardia Nacional. La milicia se divide en la milicia organizada, que consta de la Guardia Nacional y la Milicia Naval , y la milicia no organizada. [151]

En mayo de 1788, el autor seudónimo " Federal Farmer " (se presume que su verdadera identidad es Richard Henry Lee o Melancton Smith ) escribió en Cartas adicionales de The Federal Farmer #169 o Carta XVIII con respecto a la definición de "milicia":

Una milicia, cuando está debidamente formada, está formada en realidad por el propio pueblo y hace que las tropas regulares sean en gran medida innecesarias.

En junio de 1788, George Mason se dirigió a la Convención Ratificadora de Virginia con respecto a una "milicia":

Un digno miembro ha preguntado quiénes son las milicias de este país, si no son el pueblo, y si no vamos a ser protegidos del destino de los alemanes, prusianos, etc. por nuestra representación. Yo pregunto quiénes son las milicias. Ahora están formadas por todo el pueblo, excepto unos pocos funcionarios públicos. Pero no puedo decir quiénes serán las milicias del futuro. Si ese documento que está sobre la mesa no se modifica, la milicia del futuro puede no estar formada por todas las clases, altas y bajas, ricas y pobres, sino que puede limitarse a las clases bajas y medias del pueblo, excluyendo a las clases altas del pueblo. Si alguna vez llegamos a ver ese día, se pueden esperar los castigos más ignominiosos y fuertes multas. Bajo el gobierno actual, todos los rangos del pueblo están sujetos al deber de milicia.

En 1792, Tench Coxe planteó el siguiente punto en un comentario sobre la Segunda Enmienda: [152] [153] [154]

Como los gobernantes civiles, al no tener debidamente en cuenta sus deberes para con el pueblo, pueden intentar tiranizar, y como las fuerzas militares que deben movilizarse ocasionalmente para defender nuestro país pueden pervertir su poder en perjuicio de sus conciudadanos, el pueblo queda confirmado por el artículo siguiente en su derecho a poseer y portar sus armas privadas.

El primer comentario publicado sobre la Segunda Enmienda por un importante teórico constitucional fue el de St. George Tucker , quien anotó una edición de cinco volúmenes de los Comentarios sobre las leyes de Inglaterra de Sir William Blackstone , una referencia legal fundamental para los primeros abogados estadounidenses publicada en 1803. [155] [156] Tucker escribió: [157]

Siendo necesaria una milicia bien organizada para la seguridad de un estado libre, no se deberá infringir el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas. Enmiendas al artículo 4 de la CUS. Esto puede considerarse como el verdadero paladio de la libertad ... El derecho de legítima defensa es la primera ley de la naturaleza: en la mayoría de los gobiernos los gobernantes se han esforzado por confinar este derecho dentro de los límites más estrechos posibles. Dondequiera que se mantengan ejércitos permanentes y se prohíba el derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas, bajo cualquier color o pretexto, la libertad, si no está ya aniquilada, está al borde de la destrucción. En Inglaterra, el pueblo ha sido desarmado, en general, bajo el pretexto engañoso de preservar el juego: un señuelo infalible para atraer a la aristocracia terrateniente a apoyar cualquier medida, bajo esa máscara, aunque calculada para fines muy diferentes. Es cierto que, a primera vista, su declaración de derechos parece contrarrestar esta política, pero el derecho a portar armas está limitado a los protestantes, y las palabras adecuadas a su condición y grado se han interpretado para autorizar la prohibición de tener un arma u otro instrumento para la destrucción de animales de caza a cualquier granjero, comerciante de bajo nivel o cualquier otra persona no calificada para matar animales de caza, de modo que ni un solo hombre de cada quinientos puede tener un arma en su casa sin estar sujeto a una sanción.

En las notas a pie de página 40 y 41 de los Comentarios , Tucker afirmó que el derecho a portar armas bajo la Segunda Enmienda no estaba sujeto a las restricciones que formaban parte de la ley inglesa: "El derecho del pueblo a poseer y portar armas no será infringido. Enmiendas al Art. 4 de la CUS, y esto sin ninguna calificación en cuanto a su condición o grado, como es el caso en el gobierno británico" y "quienquiera que examine las leyes forestales y de caza en el código británico, percibirá fácilmente que el derecho a poseer armas es efectivamente quitado al pueblo de Inglaterra". El propio Blackstone también comentó sobre las leyes de caza inglesas, Vol. II, p. 412, "que la prevención de insurrecciones populares y la resistencia al gobierno desarmando a la mayor parte del pueblo, es una razón más a menudo pensada que declarada por los creadores de las leyes forestales y de caza". [155] Blackstone analizó el derecho de legítima defensa en una sección separada de su tratado sobre el derecho consuetudinario de los delitos. Las anotaciones de Tucker para esta última sección no mencionaron la Segunda Enmienda, pero citaron las obras canónicas de juristas ingleses como Hawkins . [g]

Además, Tucker criticó la Declaración de Derechos inglesa por limitar la posesión de armas a los muy ricos, dejando a la población efectivamente desarmada, y expresó la esperanza de que los estadounidenses "nunca dejen de considerar el derecho a poseer y portar armas como la garantía más segura de su libertad". [155]

El comentario de Tucker fue pronto seguido, en 1825, por el de William Rawle en su texto de referencia Una visión de la Constitución de los Estados Unidos de América . Al igual que Tucker, Rawle condenó el "código arbitrario de Inglaterra para la preservación de la caza", describiendo a ese país como uno que "se jacta tanto de su libertad", pero que otorga un derecho "sólo a los súbditos protestantes" que "describe cautelosamente como el de portar armas para su defensa" y reserva para "[una] proporción muy pequeña del pueblo[.]" [158]. En contraste, Rawle caracteriza la segunda cláusula de la Segunda Enmienda, a la que llama cláusula corolaria, como una prohibición general contra ese abuso caprichoso del poder gubernamental.

Hablando de la Segunda Enmienda en general, Rawle escribió: [159] [160] [161]

La prohibición es general. Ninguna cláusula de la Constitución podría, por ninguna regla de interpretación, concebirse para otorgar al Congreso el poder de desarmar al pueblo. Un intento tan flagrante sólo podría ser realizado bajo algún pretexto general por una legislatura estatal. Pero si, en una búsqueda ciega de poder desmesurado, cualquiera de los dos lo intentara, se podría apelar a esta enmienda como restricción para ambos.

Rawle, mucho antes de que los tribunales reconocieran formalmente el concepto de incorporación o de que el Congreso redactara la Decimocuarta Enmienda , sostuvo que los ciudadanos podían apelar a la Segunda Enmienda si el gobierno estatal o federal intentaba desarmarlos. Sin embargo, advirtió que "este derecho [a portar armas] no debe ... ser abusado para perturbar la paz pública" y, parafraseando a Coke , observó: "Una reunión de personas con armas, con un propósito ilegal, es un delito procesable, e incluso el porte de armas en el extranjero por un solo individuo, acompañado de circunstancias que den motivos justos para temer que se proponga hacer un uso ilegal de ellas, sería causa suficiente para exigirle que dé garantías de paz". [158]

Joseph Story articuló en sus influyentes Comentarios sobre la Constitución [162] la visión ortodoxa de la Segunda Enmienda, que él consideraba como el significado claro de la enmienda: [163] [164]

El derecho de los ciudadanos a poseer y portar armas ha sido considerado con justicia como el paladio de las libertades de una república, ya que ofrece un fuerte freno moral contra las usurpaciones y el poder arbitrario de los gobernantes y, por lo general, incluso si estos tienen éxito en la primera instancia, permitirá al pueblo resistirlos y triunfar sobre ellos. Y, sin embargo, aunque esta verdad parecería tan clara y la importancia de una milicia bien regulada parecería tan innegable, no se puede ocultar que entre el pueblo estadounidense hay una creciente indiferencia hacia cualquier sistema de disciplina de milicia y una fuerte disposición, por la conciencia de sus cargas, a librarse de todas las regulaciones. Es difícil ver cómo es posible mantener al pueblo debidamente armado sin algún tipo de organización. Ciertamente, existe un peligro no pequeño de que la indiferencia pueda conducir al disgusto y el disgusto al desprecio y, de ese modo, socavar gradualmente toda la protección prevista por esta cláusula de nuestra Carta Nacional de Derechos.

Story describe a la milicia como la "defensa natural de un país libre", tanto contra enemigos extranjeros, como contra revueltas internas y contra la usurpación de los gobernantes. El libro considera a la milicia como un "control moral" contra la usurpación y el uso arbitrario del poder, al tiempo que expresa su consternación por la creciente indiferencia del pueblo estadounidense ante el mantenimiento de una milicia tan organizada, que podría llevar a socavar la protección de la Segunda Enmienda. [164]

El abolicionista Lysander Spooner , al comentar sobre las declaraciones de derechos, afirmó que el objeto de todas las declaraciones de derechos es afirmar los derechos de los individuos contra el gobierno y que el derecho de la Segunda Enmienda a poseer y portar armas era en apoyo del derecho a resistir la opresión del gobierno, ya que la única seguridad contra la tiranía del gobierno radica en la resistencia forzosa a la injusticia, ya que la injusticia ciertamente será ejecutada, a menos que se resista por la fuerza. [165] La teoría de Spooner proporcionó la base intelectual para John Brown y otros abolicionistas radicales que creían que armar a los esclavos no solo estaba moralmente justificado, sino que era totalmente coherente con la Segunda Enmienda. [166] Lysander Spooner trazó una conexión expresa entre este derecho y la Segunda Enmienda, quien comentó que un "derecho de resistencia" está protegido tanto por el derecho a juicio por jurado como por la Segunda Enmienda. [167]

El debate en el Congreso sobre la propuesta de Decimocuarta Enmienda se centró en lo que los estados del Sur estaban haciendo para perjudicar a los esclavos recién liberados, incluido el desarme de los antiguos esclavos. [168]

En 1867, el juez Timothy Farrar publicó su Manual de la Constitución de los Estados Unidos de América , que fue escrito cuando la Decimocuarta Enmienda estaba "en proceso de adopción por las legislaturas estatales": [154] [169]

Los Estados son reconocidos como gobiernos y, cuando sus propias constituciones lo permiten, pueden hacer lo que les plazca, siempre que no interfieran con la Constitución y las leyes de los Estados Unidos, ni con los derechos civiles o naturales del pueblo reconocidos por ellas y mantenidos en conformidad con ellas. El derecho de toda persona a la "vida, la libertad y la propiedad", a "poseer y portar armas", al "recurso de hábeas corpus", al "juicio por jurado" y otros varios, están reconocidos y garantizados por la Constitución de los Estados Unidos, y no pueden ser violados por individuos ni siquiera por el propio gobierno.

El juez Thomas M. Cooley , quizás el erudito constitucional más leído del siglo XIX, escribió extensamente sobre esta enmienda, [170] [171] y explicó en 1880 cómo la Segunda Enmienda protegía el "derecho del pueblo": [172]

De la fraseología de esta disposición se podría deducir que el derecho a poseer y portar armas sólo estaba garantizado a la milicia, pero ésta sería una interpretación que no se justificaría por la intención. La milicia, como se ha explicado en otra parte, está formada por aquellas personas que, según la ley, están obligadas a cumplir con el deber militar y son nombradas oficiales y alistadas para el servicio cuando se las convoca. Pero la ley puede prever el alistamiento de todos los que sean aptos para cumplir con el deber militar, o sólo de un pequeño número, o puede omitir totalmente cualquier disposición; y si el derecho se limitara a los alistados, el propósito de esta garantía podría verse frustrado por completo por la acción o la negligencia del gobierno que se pretendía mantener bajo control. El significado de la disposición es, sin duda, que el pueblo, del que debe tomarse la milicia, tendrá derecho a poseer y portar armas; y no necesita permiso ni regulación legal para ello. Pero esto permite al gobierno tener una milicia bien regulada, porque portar armas implica algo más que el mero hecho de poseer; implica el aprendizaje de su manejo y uso, de manera que quienes los poseen estén dispuestos a su uso eficiente; en otras palabras, implica el derecho a reunirse para la disciplina voluntaria en las armas, observando al hacerlo las leyes del orden público.

Hasta finales del siglo XX, hubo pocos comentarios académicos sobre la Segunda Enmienda. [173] En la segunda mitad del siglo XX, hubo un debate considerable sobre si la Segunda Enmienda protegía un derecho individual o un derecho colectivo . [174] El debate se centró en si la cláusula introductoria ("Una milicia bien regulada es necesaria para la seguridad de un Estado libre") declaraba el único propósito de la enmienda o simplemente anunciaba el propósito de introducir la cláusula operativa ("el derecho del Pueblo a poseer y portar armas no será infringido"). Los académicos propusieron tres modelos teóricos en competencia sobre cómo debería interpretarse la cláusula introductoria. [175]

El primero, conocido como el modelo de los " derechos de los estados " o "derecho colectivo", sostenía que la Segunda Enmienda no se aplica a los individuos; más bien, reconoce el derecho de cada estado a armar a su milicia. Según este enfoque, los ciudadanos "no tienen derecho a tener o portar armas, pero los estados tienen un derecho colectivo a tener la Guardia Nacional". [154] Los defensores de los modelos de derechos colectivos argumentaron que la Segunda Enmienda fue escrita para impedir que el gobierno federal desarmara a las milicias estatales, en lugar de garantizar un derecho individual a poseer armas de fuego. [176] Antes de 2001, todas las decisiones de los tribunales de circuito que interpretaban la Segunda Enmienda respaldaban el modelo del "derecho colectivo". [177] [178] Sin embargo, a partir de la opinión del Quinto Circuito en el caso Estados Unidos contra Emerson en 2001, algunos tribunales de circuito reconocieron que la Segunda Enmienda protege el derecho individual a portar armas. [179] [180]

El segundo, conocido como el "modelo sofisticado de derecho colectivo", sostenía que la Segunda Enmienda reconoce algunos derechos individuales limitados. Sin embargo, este derecho individual sólo puede ser ejercido por miembros que participen activamente en una milicia estatal organizada y funcional. [181] [176] Algunos académicos han sostenido que el "modelo sofisticado de derechos colectivos" es, de hecho, el equivalente funcional del "modelo de derechos colectivos". [182] Otros comentaristas han observado que antes de Emerson , cinco tribunales de circuito respaldaron específicamente el "modelo sofisticado de derecho colectivo". [183]

El tercero, conocido como el "modelo estándar", sostenía que la Segunda Enmienda reconocía el derecho personal de los individuos a poseer y portar armas. [154] Los partidarios de este modelo argumentaban que "aunque la primera cláusula puede describir un propósito general para la enmienda, la segunda cláusula es determinante y, por lo tanto, la enmienda confiere un derecho individual 'del pueblo' a poseer y portar armas". [184] Además, los académicos que favorecían este modelo argumentaban que la "ausencia de milicias de la era fundadora mencionadas en el preámbulo de la Enmienda no la convierte en 'letra muerta' porque el preámbulo es una 'declaración filosófica' que protege a las milicias y es solo uno de los múltiples 'propósitos cívicos' para los que se promulgó la Enmienda". [185]

En ambos modelos de derecho colectivo, la frase inicial se consideraba esencial como condición previa para la cláusula principal. [186] Estas interpretaciones sostenían que se trataba de una estructura gramatical común durante esa época [187] y que esta gramática dictaba que la Segunda Enmienda protegía un derecho colectivo a las armas de fuego en la medida necesaria para el deber de la milicia. [188] Sin embargo, en el modelo estándar, se creía que la frase inicial era preliminar o ampliatoria de la cláusula operativa. La frase inicial estaba pensada como un ejemplo no exclusivo, una de las muchas razones para la enmienda. [46] Esta interpretación es coherente con la posición de que la Segunda Enmienda protege un derecho individual modificado. [189]

La cuestión de un derecho colectivo frente a un derecho individual se fue resolviendo progresivamente a favor del modelo de derechos individuales, comenzando con el fallo del Quinto Circuito en Estados Unidos v. Emerson (2001), junto con los fallos de la Corte Suprema en Distrito de Columbia v. Heller (2008), y McDonald v. Chicago (2010). En Heller , la Corte Suprema resolvió cualquier división restante del circuito al dictaminar que la Segunda Enmienda protege un derecho individual. [190] Aunque la Segunda Enmienda es la única enmienda constitucional con una cláusula introductoria, tales construcciones lingüísticas se utilizaron ampliamente en otros lugares a fines del siglo XVIII. [191]

Warren E. Burger , un republicano conservador designado presidente de la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos por el presidente Richard Nixon, escribió en 1990 después de su jubilación: [192]

The Constitution of the United States, in its Second Amendment, guarantees a "right of the people to keep and bear arms". However, the meaning of this clause cannot be understood except by looking to the purpose, the setting and the objectives of the draftsmen ... People of that day were apprehensive about the new "monster" national government presented to them, and this helps explain the language and purpose of the Second Amendment ... We see that the need for a state militia was the predicate of the "right" guaranteed; in short, it was declared "necessary" in order to have a state military force to protect the security of the state.

And in 1991, Burger stated:[193]

If I were writing the Bill of Rights now, there wouldn't be any such thing as the Second Amendment ... that a well regulated militia being necessary for the defense of the state, the peoples' rights to bear arms. This has been the subject of one of the greatest pieces of fraud – I repeat the word 'fraud' – on the American public by special interest groups that I have ever seen in my lifetime.

In a 1992 opinion piece, six former American attorneys general wrote:[194]

For more than 200 years, the federal courts have unanimously determined that the Second Amendment concerns only the arming of the people in service to an organized state militia; it does not guarantee immediate access to guns for private purposes. The nation can no longer afford to let the gun lobby's distortion of the Constitution cripple every reasonable attempt to implement an effective national policy toward guns and crime.

Research by Robert Spitzer found that every law journal article discussing the Second Amendment through 1959 "reflected the Second Amendment affects citizens only in connection with citizen service in a government organized and regulated militia." Only beginning in 1960 did law journal articles begin to advocate an "individualist" view of gun ownership rights.[195][196] The opposite of this "individualist" view of gun ownership rights is the "collective-right" theory, according to which the amendment protects a collective right of states to maintain militias or an individual right to keep and bear arms in connection with service in a militia (for this view see for example the quote of Justice John Paul Stevens in the Meaning of "well regulated militia" section below).[197] In his book, Six Amendments: How and Why We Should Change the Constitution, Justice John Paul Stevens for example submits the following revised Second Amendment: "A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms when serving in the militia shall not be infringed."[198]

An early use of the phrase "well-regulated militia" may be found in Andrew Fletcher's 1698 A Discourse of Government with Relation to Militias, as well as the phrase "ordinary and ill-regulated militia".[199] Fletcher meant "regular" in the sense of regular military, and advocated the universal conscription and regular training of men of fighting age. Jefferson thought well of Fletcher, commenting that "the political principles of that patriot were worthy the purest periods of the British constitution. They are those which were in vigour."[200]

The term "regulated" means "disciplined" or "trained".[201] In Heller, the U.S. Supreme Court stated that "[t]he adjective 'well-regulated' implies nothing more than the imposition of proper discipline and training."[202]

In the year before the drafting of the Second Amendment, in Federalist No. 29 ("On the Militia"), Alexander Hamilton wrote the following about "organizing", "disciplining", "arming", and "training" of the militia as specified in the enumerated powers:[84]

If a well regulated militia be the most natural defence of a free country, it ought certainly to be under the regulation and at the disposal of that body which is constituted the guardian of the national security ... confiding the regulation of the militia to the direction of the national authority ... [but] reserving to the states ... the authority of training the militia ... A tolerable expertness in military movements is a business that requires time and practice. It is not a day, or even a week, that will suffice for the attainment of it. To oblige the great body of the yeomanry, and of the other classes of the citizens, to be under arms for the purpose of going through military exercises and evolutions, as often as might be necessary to acquire the degree of perfection which would entitle them to the character of a well-regulated militia, would be a real grievance to the people, and a serious public inconvenience and loss ... Little more can reasonably be aimed at, with respect to the People at large, than to have them properly armed and equipped; and in order to see that this be not neglected, it will be necessary to assemble them once or twice in the course of a year.

Justice Scalia, writing for the Court in Heller:[203]

In Nunn v. State, 1 Ga. 243, 251 (1846), the Georgia Supreme Court construed the Second Amendment as protecting the 'natural right of self-defence' and therefore struck down a ban on carrying pistols openly. Its opinion perfectly captured the way in which the operative clause of the Second Amendment furthers the purpose announced in the prefatory clause, in continuity with the English right". ... Nor is the right involved in this discussion less comprehensive or valuable: "The right of the people to bear arms shall not be infringed." The right of the whole people, old and young, men, women and boys, and not militia only, to keep and bear arms of every description, not such merely as are used by the militia, shall not be infringed, curtailed, or broken in upon, in the smallest degree; and all this for the important end to be attained: the rearing up and qualifying a well-regulated militia, so vitally necessary to the security of a free State. Our opinion is, that any law, State or Federal, is repugnant to the Constitution, and void, which contravenes this right, originally belonging to our forefathers, trampled under foot by Charles I. and his two wicked sons and successors, reestablished by the revolution of 1688, conveyed to this land of liberty by the colonists, and finally incorporated conspicuously in our own Magna Charta [sic]! And Lexington, Concord, Camden, River Raisin, Sandusky, and the laurel-crowned field of New Orleans, plead eloquently for this interpretation! And the acquisition of Texas may be considered the full fruits of this great constitutional right.

Justice Stevens in dissent:[197]

When each word in the text is given full effect, the Amendment is most naturally read to secure to the people a right to use and possess arms in conjunction with service in a well-regulated militia. So far as appears, no more than that was contemplated by its drafters or is encompassed within its terms. Even if the meaning of the text were genuinely susceptible to more than one interpretation, the burden would remain on those advocating a departure from the purpose identified in the preamble and from settled law to come forward with persuasive new arguments or evidence. The textual analysis offered by respondent and embraced by the Court falls far short of sustaining that heavy burden. And the Court's emphatic reliance on the claim "that the Second Amendment ... codified a pre-existing right," ante, at 19 [refers to p. 19 of the opinion], is of course beside the point because the right to keep and bear arms for service in a state militia was also a pre-existing right.

Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the majority in Heller, stated:

Nowhere else in the Constitution does a "right" attributed to "the people" refer to anything other than an individual right. What is more, in all six other provisions of the Constitution that mention "the people", the term unambiguously refers to all members of the political community, not an unspecified subset. This contrasts markedly with the phrase "the militia" in the prefatory clause. As we will describe below, the "militia" in colonial America consisted of a subset of "the people" – those who were male, able bodied, and within a certain age range. Reading the Second Amendment as protecting only the right to "keep and bear Arms" in an organized militia therefore fits poorly with the operative clause's description of the holder of that right as "the people".[204]

Scalia further specifies who holds this right:[205]

[The Second Amendment] surely elevates above all other interests the right of law-abiding, responsible citizens to use arms in defense of hearth and home.

An earlier case, United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez (1990), dealt with nonresident aliens and the Fourth Amendment, but led to a discussion of who are "the People" when referred to elsewhere in the Constitution:[206]

The Second Amendment protects "the right of the people to keep and bear Arms", and the Ninth and Tenth Amendments provide that certain rights and powers are retained by and reserved to "the people" ... While this textual exegesis is by no means conclusive, it suggests that "the people" protected by the Fourth Amendment, and by the First and Second Amendments, and to whom rights and powers are reserved in the Ninth and Tenth Amendments, refers to a class of persons who are part of a national community or who have otherwise developed sufficient connection with this country to be considered part of that community.

According to the majority in Heller, there were several different reasons for this amendment, and protecting militias was only one of them; if protecting militias had been the only reason then the amendment could have instead referred to "the right of the militia to keep and bear arms" instead of "the right of the people to keep and bear arms".[207][208]

In Heller the majority rejected the view that the term "to bear arms" implies only the military use of arms:[204]

Before addressing the verbs "keep" and "bear", we interpret their object: "Arms". The term was applied, then as now, to weapons that were not specifically designed for military use and were not employed in a military capacity. Thus, the most natural reading of "keep Arms" in the Second Amendment is to "have weapons". At the time of the founding, as now, to "bear" meant to "carry". In numerous instances, "bear arms" was unambiguously used to refer to the carrying of weapons outside of an organized militia. Nine state constitutional provisions written in the 18th century or the first two decades of the 19th, which enshrined a right of citizens "bear arms in defense of themselves and the state" again, in the most analogous linguistic context – that "bear arms" was not limited to the carrying of arms in a militia. The phrase "bear Arms" also had at the time of the founding an idiomatic meaning that was significantly different from its natural meaning: "to serve as a soldier, do military service, fight" or "to wage war". But it unequivocally bore that idiomatic meaning only when followed by the preposition "against". Every example given by petitioners' amici for the idiomatic meaning of "bear arms" from the founding period either includes the preposition "against" or is not clearly idiomatic. In any event, the meaning of "bear arms" that petitioners and Justice Stevens propose is not even the (sometimes) idiomatic meaning. Rather, they manufacture a hybrid definition, whereby "bear arms" connotes the actual carrying of arms (and therefore is not really an idiom) but only in the service of an organized militia. No dictionary has ever adopted that definition, and we have been apprised of no source that indicates that it carried that meaning at the time of the founding. Worse still, the phrase "keep and bear Arms" would be incoherent. The word "Arms" would have two different meanings at once: "weapons" (as the object of "keep") and (as the object of "bear") one-half of an idiom. It would be rather like saying "He filled and kicked the bucket" to mean "He filled the bucket and died."

In a dissent, joined by justices Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer, Justice Stevens said:[209]