Sídney es la capital del estado de Nueva Gales del Sur y la ciudad más poblada de Australia . Ubicada en la costa este de Australia, la metrópolis rodea el puerto de Sídney y se extiende unos 80 km (50 mi) desde el océano Pacífico en el este hasta las Montañas Azules en el oeste, y unos 80 km (50 mi) desde el Parque Nacional Ku-ring-gai Chase y el río Hawkesbury en el norte y noroeste, hasta el Parque Nacional Real y Macarthur en el sur y suroeste. [5] El Gran Sídney consta de 658 suburbios, distribuidos en 33 áreas de gobierno local. Los residentes de la ciudad son conocidos coloquialmente como "Sydneysiders". [6] La población estimada en junio de 2023 era de 5.450.496, [1] lo que representa aproximadamente el 66% de la población del estado. [7] Los apodos de la ciudad incluyen "Ciudad Esmeralda" y "Ciudad del Puerto". [8]

Los aborígenes australianos han habitado la región del Gran Sídney durante al menos 30.000 años, y sus grabados y sitios culturales son comunes. Los custodios tradicionales de la tierra en la que se encuentra la moderna Sídney son los clanes de los pueblos Darug , Dharawal y Eora . [9] Durante su primer viaje al Pacífico en 1770, James Cook cartografió la costa oriental de Australia, llegando a tierra en Botany Bay . En 1788, la Primera Flota de convictos , liderada por Arthur Phillip , fundó Sídney como colonia penal británica , el primer asentamiento europeo en Australia. [10] Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Sídney experimentó una migración masiva y para 2021 más del 40 por ciento de la población nació en el extranjero. Los países extranjeros de nacimiento con mayor representación son China continental, India, Reino Unido, Vietnam y Filipinas. [11]

A pesar de ser una de las ciudades más caras del mundo, [12] [13] Sídney se clasifica frecuentemente entre las diez ciudades más habitables . [14] [15] [16] Está clasificada como una ciudad Alfa por la Red de Investigación de Globalización y Ciudades del Mundo , lo que indica su influencia en la región y en todo el mundo. [17] [18] Clasificada en el undécimo lugar en el mundo por oportunidades económicas, [19] Sídney tiene una economía de mercado avanzada con fortalezas en educación, finanzas, manufactura y turismo . [20] [21] La Universidad de Sídney y la Universidad de Nueva Gales del Sur están clasificadas en el puesto 19 en el mundo. [22]

Sydney ha sido sede de importantes eventos deportivos internacionales, como los Juegos Olímpicos de Verano de 2000. La ciudad se encuentra entre las quince más visitadas, [23] con millones de turistas que vienen cada año a ver los monumentos de la ciudad. [24] La ciudad tiene más de 1.000.000 ha (2.500.000 acres) de reservas naturales y parques , [25] y sus características naturales notables incluyen el Puerto de Sydney y el Parque Nacional Real . El Puente del Puerto de Sydney y la Ópera de Sydney , declarada Patrimonio de la Humanidad, son importantes atracciones turísticas. La Estación Central es el centro de las redes de trenes suburbanos, metro y tren ligero de Sydney y de los servicios de larga distancia. El principal aeropuerto de pasajeros que da servicio a la ciudad es el Aeropuerto Kingsford Smith , uno de los aeropuertos en funcionamiento continuo más antiguos del mundo. [26]

En 1788, el capitán Arthur Phillip , el primer gobernador de Nueva Gales del Sur, nombró Sydney Cove a la ensenada donde se estableció el primer asentamiento británico en honor al ministro del Interior Thomas Townshend, primer vizconde de Sydney . [27] Los habitantes aborígenes llamaban Warrane a la ensenada . [28] Phillip consideró nombrar el asentamiento Albion , pero este nombre nunca se usó oficialmente. [27] En 1790, Phillip y otros funcionarios llamaban regularmente Sydney al municipio. [29] Sydney fue declarada ciudad en 1842. [30]

El clan Gadigal (Cadigal), cuyo territorio se extiende a lo largo de la costa sur de Port Jackson desde South Head hasta Darling Harbour , son los propietarios tradicionales de la tierra en la que se estableció inicialmente el asentamiento británico y llaman a su territorio Gadi ( Cadi ). Los nombres de los clanes aborígenes dentro de la región de Sydney a menudo se formaban agregando el sufijo "-gal" a una palabra que denota el nombre de su territorio, un lugar específico en su territorio, una fuente de alimento o un tótem. El Gran Sydney cubre las tierras tradicionales de 28 clanes aborígenes conocidos. [31]

Las primeras personas que habitaron la zona conocida hoy como Sídney fueron aborígenes australianos que habían migrado desde el sudeste asiático a través del norte de Australia. [32] Los guijarros en escamas encontrados en los sedimentos de grava del oeste de Sídney podrían indicar ocupación humana desde hace 45.000 a 50.000 años, [33] mientras que la datación por radiocarbono ha mostrado evidencia de actividad humana en la región desde hace unos 30.000 años. [34] Antes de la llegada de los británicos, había entre 4.000 y 8.000 aborígenes en la región metropolitana de Sídney. [35] [9]

Los habitantes subsistían de la pesca, la caza y la recolección de plantas y mariscos. La dieta de los clanes costeros dependía más de los mariscos, mientras que los clanes del interior comían más animales y plantas del bosque. Los clanes tenían equipos y armas distintivos, hechos principalmente de piedra, madera, materiales vegetales, huesos y conchas. También diferían en sus decoraciones corporales, peinados, canciones y bailes. Los clanes aborígenes tenían una rica vida ceremonial, parte de un sistema de creencias centrado en seres ancestrales, totémicos y sobrenaturales. Personas de diferentes clanes y grupos lingüísticos se reunían para participar en ceremonias de iniciación y otras ceremonias. Estas ocasiones fomentaban el comercio, los matrimonios y las alianzas entre clanes. [36]

Los primeros colonos británicos registraron la palabra " Eora " como un término aborigen que significa "gente" o "de este lugar". [37] [9] Los clanes de la zona de Sydney ocupaban tierras con límites tradicionales. Sin embargo, existe un debate sobre a qué grupo o nación pertenecían estos clanes y el alcance de las diferencias en el idioma y los ritos. Los grupos principales eran el pueblo costero Eora, los Dharug (Darug) que ocupaban el área interior desde Parramatta hasta las Montañas Azules, y el pueblo Dharawal al sur de Botany Bay. [9] Las lenguas Darginung y Gundungurra se hablaban en los márgenes del área de Sydney. [38]

El primer encuentro entre aborígenes y exploradores británicos se produjo el 29 de abril de 1770, cuando el teniente James Cook desembarcó en Botany Bay (Kamay [41] ) y se encontró con el clan Gweagal . [42] Dos hombres de Gweagal se opusieron al grupo de desembarco y uno recibió un disparo y resultó herido. [43] [44] Cook y su tripulación permanecieron en Botany Bay durante una semana, recogiendo agua, madera, forraje y especímenes botánicos y explorando el área circundante. Cook intentó establecer relaciones con la población aborigen sin éxito. [45]

Gran Bretaña había enviado convictos a sus colonias americanas durante la mayor parte del siglo XVIII, y la pérdida de estas colonias en 1783 fue el impulso para establecer una colonia penal en Botany Bay. Los defensores de la colonización también señalaron la importancia estratégica de una nueva base en la región de Asia y el Pacífico y su potencial para proporcionar madera y lino muy necesarios para la marina. [46]

La primera flota de 11 barcos bajo el mando del capitán Arthur Phillip llegó a Botany Bay en enero de 1788. Estaba compuesta por más de mil colonos, incluidos 736 convictos. [47] La flota pronto se trasladó a Port Jackson, un puerto más adecuado , donde se estableció un asentamiento en Sydney Cove el 26 de enero de 1788. [48] El gobernador Phillip proclamó formalmente la colonia de Nueva Gales del Sur el 7 de febrero de 1788. Sydney Cove ofrecía un suministro de agua dulce y un puerto seguro, que Philip describió como "el mejor puerto del mundo... Aquí pueden navegar mil velas de línea con la más perfecta seguridad". [49]

El asentamiento fue planeado para ser una colonia penal autosuficiente basada en la agricultura de subsistencia. El comercio y la construcción naval fueron prohibidos para mantener a los convictos aislados. Sin embargo, el suelo alrededor del asentamiento resultó pobre y las primeras cosechas fracasaron, lo que llevó a varios años de hambre y racionamiento estricto. La crisis alimentaria se alivió con la llegada de la Segunda Flota a mediados de 1790 y la Tercera Flota en 1791. [50] Los ex convictos recibieron pequeñas concesiones de tierra, y las granjas gubernamentales y privadas se extendieron a las tierras más fértiles alrededor de Parramatta , Windsor y Camden en la llanura de Cumberland . En 1804, la colonia era autosuficiente en alimentos. [51]

Una epidemia de viruela en abril de 1789 mató a aproximadamente la mitad de la población indígena de la región. [9] [52] En noviembre de 1790, Bennelong dirigió a un grupo de sobrevivientes de los clanes de Sydney al asentamiento, estableciendo una presencia continua de aborígenes australianos en la Sydney colonizada. [53]

Phillip no había recibido instrucciones para el desarrollo urbano, pero en julio de 1788 presentó un plan para la nueva ciudad en Sydney Cove . Incluía una amplia avenida central, una casa de gobierno permanente, tribunales de justicia, un hospital y otros edificios públicos, pero no preveía almacenes, tiendas u otros edificios comerciales. Phillip ignoró rápidamente su propio plan y el desarrollo no planificado se convirtió en una característica de la topografía de Sydney. [54] [55]

Después de la partida de Phillip en diciembre de 1792, los oficiales militares de la colonia comenzaron a adquirir tierras e importar bienes de consumo de los barcos visitantes. Los ex convictos se dedicaron al comercio y abrieron pequeños negocios. Los soldados y los ex convictos construyeron casas en tierras de la Corona, con o sin permiso oficial, en lo que ahora se llamaba comúnmente la ciudad de Sydney. El gobernador William Bligh (1806-08) impuso restricciones al comercio y ordenó la demolición de edificios erigidos en tierras de la Corona, incluidos algunos propiedad de oficiales militares en servicio y pasados. El conflicto resultante culminó en la Rebelión del Ron de 1808, en la que Bligh fue depuesto por el Cuerpo de Nueva Gales del Sur . [56] [57]

El gobernador Lachlan Macquarie (1810-1821) desempeñó un papel destacado en el desarrollo de Sídney y Nueva Gales del Sur, estableciendo un banco, una moneda y un hospital. Contrató a un planificador para diseñar el trazado de las calles de Sídney y encargó la construcción de carreteras, muelles, iglesias y edificios públicos. La carretera Parramatta , que unía Sídney y Parramatta, se inauguró en 1811, [58] y en 1815 se completó una carretera que atravesaba las Montañas Azules , abriendo el camino a la agricultura y el pastoreo a gran escala al oeste de la Gran Cordillera Divisoria . [59] [60]

Tras la marcha de Macquarie, la política oficial fomentó la emigración de colonos británicos libres a Nueva Gales del Sur. La inmigración a la colonia aumentó de 900 colonos libres en 1826-30 a 29.000 en 1836-40, muchos de los cuales se asentaron en Sídney. [61] [62] En la década de 1840, Sídney exhibía una división geográfica entre los residentes pobres y de clase trabajadora que vivían al oeste del Tank Stream en zonas como The Rocks , y los residentes más adinerados que vivían al este. [62] Los colonos libres, los residentes nacidos libres y los ex convictos representaban ahora la gran mayoría de la población de Sídney, lo que llevó a una creciente agitación pública por un gobierno responsable y el fin del transporte. El transporte a Nueva Gales del Sur cesó en 1840. [63]

.jpg/440px-Castle_Hill_Rebellion_(1804).jpg)

En 1804, los convictos irlandeses lideraron a unos 300 rebeldes en la Rebelión de Castle Hill , un intento de marchar sobre Sídney, apoderarse de un barco y navegar hacia la libertad. [64] Mal armados y con su líder Philip Cunningham capturado, el cuerpo principal de insurgentes fue derrotado por unos 100 soldados y voluntarios en Rouse Hill . Al menos 39 convictos murieron en el levantamiento y las ejecuciones posteriores. [65] [66]

A medida que la colonia se extendía a las tierras más fértiles alrededor del río Hawkesbury , al noroeste de Sídney, el conflicto entre los colonos y el pueblo Darug se intensificó, alcanzando un pico entre 1794 y 1810. Bandas de Darug, lideradas por Pemulwuy y más tarde por su hijo Tedbury , quemaron cultivos, mataron ganado y asaltaron las tiendas de los colonos en un patrón de resistencia que se repetiría a medida que se expandía la frontera colonial . Se estableció una guarnición militar en Hawkesbury en 1795. El número de muertos entre 1794 y 1800 fue de 26 colonos y hasta 200 Darug. [67] [68]

El conflicto estalló nuevamente entre 1814 y 1816 con la expansión de la colonia hacia el territorio de Dharawal, en la región de Nepean, al suroeste de Sydney. Tras la muerte de varios colonos, el gobernador Macquarie envió tres destacamentos militares a las tierras de Dharawal, lo que culminó en la masacre de Appin (abril de 1816), en la que murieron al menos 14 aborígenes. [69] [70]

El Consejo Legislativo de Nueva Gales del Sur se convirtió en un organismo semielegido en 1842. Sydney fue declarada ciudad el mismo año y se estableció un consejo de gobierno, elegido con un sufragio de propiedad restrictivo. [63]

El descubrimiento de oro en Nueva Gales del Sur y Victoria en 1851 causó inicialmente trastornos económicos a medida que los hombres se mudaban a los yacimientos de oro. Melbourne pronto superó a Sydney como la ciudad más grande de Australia, lo que llevó a una rivalidad duradera entre las dos. Sin embargo, el aumento de la inmigración desde el extranjero y la riqueza de las exportaciones de oro aumentaron la demanda de viviendas, bienes de consumo, servicios y comodidades urbanas. [71] El gobierno de Nueva Gales del Sur también estimuló el crecimiento invirtiendo fuertemente en ferrocarriles, tranvías, carreteras, puertos, telégrafos, escuelas y servicios urbanos. [72] La población de Sydney y sus suburbios creció de 95.600 en 1861 a 386.900 en 1891. [73] La ciudad desarrolló muchas de sus características características. La creciente población se apiñó en hileras de casas adosadas en calles estrechas. Abundaron los nuevos edificios públicos de arenisca, incluidos los de la Universidad de Sídney (1854-1861), [74] el Museo Australiano (1858-1866), [75] el Ayuntamiento (1868-1888), [76] y la Oficina General de Correos (1866-1892). [77] Se erigieron elaborados palacios de café y hoteles. [78] Se prohibió bañarse durante el día en las playas de Sídney, pero el baño segregado en baños oceánicos designados era popular. [79]

La sequía, la paralización de las obras públicas y una crisis financiera llevaron a una depresión económica en Sydney durante la mayor parte de la década de 1890. Mientras tanto, el primer ministro de Nueva Gales del Sur con sede en Sydney, George Reid , se convirtió en una figura clave en el proceso de federación. [80]

_from_Union_Line_Building_(incorporating_the_Bjelke-Petersen_School_of_Physical_culture),_corner_Jamieson_Street),_n.d._by_(5955844045).jpg/440px-thumbnail.jpg)

Cuando las seis colonias se federaron el 1 de enero de 1901, Sydney se convirtió en la capital del estado de Nueva Gales del Sur. La propagación de la peste bubónica en 1900 impulsó al gobierno estatal a modernizar los muelles y demoler los barrios marginales del centro de la ciudad. El estallido de la Primera Guerra Mundial en 1914 hizo que más hombres de Sydney se ofrecieran como voluntarios para las fuerzas armadas de lo que las autoridades de la Commonwealth podían procesar, y ayudó a reducir el desempleo. A los que regresaron de la guerra en 1918 se les prometieron "hogares dignos de héroes" en nuevos suburbios como Daceyville y Matraville. Los "suburbios de jardines" y los desarrollos industriales y residenciales mixtos también crecieron a lo largo de los corredores ferroviarios y tranviarios. [62] La población alcanzó el millón en 1926, después de que Sydney recuperara su posición como la ciudad más poblada de Australia. [81] El gobierno creó puestos de trabajo con proyectos públicos masivos como la electrificación de la red ferroviaria de Sydney y la construcción del Puente del Puerto de Sydney. [82]

La Gran Depresión de los años 30 afectó más a Sydney que la región de Nueva Gales del Sur o Melbourne. [83] La construcción de edificios nuevos casi se paralizó y, en 1933, la tasa de desempleo de los trabajadores varones era del 28 por ciento, pero superior al 40 por ciento en zonas de clase trabajadora como Alexandria y Redfern. Muchas familias fueron desalojadas de sus hogares y crecieron barrios marginales a lo largo de la costa de Sydney y Botany Bay, siendo el más grande "Happy Valley" en La Perouse . [84] La Depresión también exacerbó las divisiones políticas. En marzo de 1932, cuando el primer ministro laborista populista Jack Lang intentó abrir el Puente del Puerto de Sydney, fue eclipsado por Francis de Groot , de la ultraderechista Nueva Guardia , que cortó la cinta con un sable. [85]

En enero de 1938, Sydney celebró los Juegos del Imperio y el sesquicentenario de la colonización europea en Australia. Un periodista escribió: "Playas doradas. Hombres y doncellas bronceados por el sol... Villas con tejados rojos en terrazas sobre las aguas azules del puerto... Incluso Melbourne parece una ciudad gris y majestuosa del norte de Europa comparada con los esplendores subtropicales de Sydney". Un congreso de los "aborígenes de Australia" declaró el 26 de enero " Día de luto " por "la toma de nuestro país por parte de los blancos". [86]

Con el estallido de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en 1939, Sídney experimentó un auge en el desarrollo industrial. El desempleo prácticamente desapareció y las mujeres pasaron a ocupar puestos de trabajo que antes estaban reservados para los hombres. Sídney fue atacada por submarinos japoneses en mayo y junio de 1942 con 21 muertos. Las familias construyeron refugios antiaéreos y realizaron simulacros. [87] Los establecimientos militares en respuesta a la Segunda Guerra Mundial en Australia incluyeron el Sistema de Túneles de Garden Island , el único complejo de guerra de túneles en Sídney, y los sistemas de fortificación militar declarados patrimonio Bradleys Head Fortification Complex y Middle Head Fortifications , que formaban parte de un sistema de defensa total para el puerto de Sídney . [88]

La inmigración y el baby boom de posguerra provocaron un rápido aumento de la población de Sídney y la expansión de las viviendas de baja densidad en los suburbios de toda la llanura de Cumberland. Los inmigrantes, en su mayoría de Gran Bretaña y Europa continental, y sus hijos representaron más de las tres cuartas partes del crecimiento de la población de Sídney entre 1947 y 1971. [89] El recién creado Consejo del Condado de Cumberland supervisó los desarrollos residenciales de baja densidad, los más grandes en Green Valley y Mount Druitt . Los centros residenciales más antiguos, como Parramatta, Bankstown y Liverpool, se convirtieron en suburbios de la metrópolis. [90] La industria manufacturera, protegida por altos aranceles, empleó a más de un tercio de la fuerza laboral desde 1945 hasta la década de 1960. Sin embargo, a medida que avanzaba el largo auge económico de posguerra, las industrias minoristas y de servicios se convirtieron en la principal fuente de nuevos empleos. [91]

Se estima que un millón de espectadores, la mayor parte de la población de la ciudad, vieron a la reina Isabel II desembarcar en 1954 en Farm Cove, donde el capitán Phillip había izado la Union Jack 165 años antes, iniciando su gira real australiana . Fue la primera vez que un monarca reinante pisó suelo australiano. [92]

El creciente desarrollo de edificios de gran altura en Sídney y la expansión de los suburbios más allá del "cinturón verde" previsto por los planificadores de la década de 1950 dieron lugar a protestas comunitarias. A principios de la década de 1970, los sindicatos y los grupos de acción de los residentes impusieron prohibiciones verdes a los proyectos de desarrollo en áreas históricas como The Rocks. Los gobiernos federales, estatales y locales introdujeron una legislación medioambiental y patrimonial. [62] La Ópera de Sídney también fue controvertida por su coste y las disputas entre el arquitecto Jørn Utzon y los funcionarios del gobierno. Sin embargo, poco después de su inauguración en 1973 se convirtió en una importante atracción turística y símbolo de la ciudad. [93] La reducción progresiva de la protección arancelaria a partir de 1974 inició la transformación de Sídney de un centro manufacturero a una "ciudad mundial". [94] A partir de la década de 1980, la inmigración extranjera creció rápidamente, y Asia , Oriente Medio y África se convirtieron en las principales fuentes. En 2021, la población de Sídney superaba los 5,2 millones, y el 40% de la población había nacido en el extranjero. China y la India superaron a Inglaterra como los principales países de origen de residentes nacidos en el extranjero. [95]

Sídney es una cuenca costera con el mar de Tasmania al este, las Montañas Azules al oeste, el río Hawkesbury al norte y la meseta de Woronora al sur.

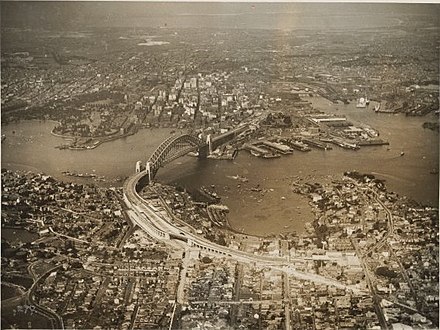

Sydney se extiende a lo largo de dos regiones geográficas. La llanura de Cumberland se encuentra al sur y al oeste del puerto y es relativamente plana. La meseta de Hornsby se encuentra al norte y está atravesada por valles escarpados. Las zonas planas del sur fueron las primeras en desarrollarse; no fue hasta la construcción del puente del puerto de Sydney que las zonas del norte se poblaron más. Se pueden encontrar setenta playas de surf a lo largo de su costa, siendo Bondi Beach la más famosa.

El río Nepean rodea el borde occidental de la ciudad y se convierte en el río Hawkesbury antes de llegar a Broken Bay . La mayoría de las reservas de agua de Sídney se encuentran en los afluentes del río Nepean. El río Parramatta es principalmente industrial y drena una gran zona de los suburbios occidentales de Sídney hacia Port Jackson. Las partes meridionales de la ciudad son drenadas por el río Georges y el río Cooks hacia Botany Bay.

No existe una única definición de los límites de Sídney. La definición del Estándar de Geografía Estadística Australiana de Gran Sídney cubre 12.369 km2 ( 4.776 millas cuadradas) e incluye las áreas de gobierno local de Central Coast en el norte, Hawkesbury en el noroeste, Blue Mountains en el oeste, Sutherland Shire en el sur y Wollondilly en el suroeste. [96] El área de gobierno local de la ciudad de Sídney cubre aproximadamente 26 kilómetros cuadrados desde Garden Island en el este hasta Bicentennial Park en el oeste, y al sur hasta los suburbios de Alexandria y Rosebery . [97]

Sydney está formada principalmente por rocas del Triásico con algunos diques ígneos recientes y cuellos volcánicos (que se encuentran típicamente en la intrusión de dolerita Prospect , al oeste de Sydney). [98] La cuenca de Sydney se formó a principios del período Triásico. [99] La arena que se convertiría en la arenisca de hoy se depositó hace entre 360 y 200 millones de años. La arenisca tiene lentes de esquisto y lechos de ríos fósiles. [99]

La biorregión de la cuenca de Sídney incluye características costeras de acantilados, playas y estuarios. Los valles fluviales profundos conocidos como rías fueron tallados durante el período Triásico en la arenisca de Hawkesbury de la región costera. El aumento del nivel del mar entre 18.000 y 6.000 años atrás inundó las rías para formar estuarios y puertos profundos. [99] Port Jackson, mejor conocido como el puerto de Sídney, es una de esas rías . [100] Sídney presenta dos tipos principales de suelo: suelos arenosos (que se originan en la arenisca de Hawkesbury) y arcilla (que provienen de lutitas y rocas volcánicas ), aunque algunos suelos pueden ser una mezcla de los dos. [101]

Directamente sobre la arenisca Hawkesbury más antigua se encuentra la pizarra Wianamatta , una formación geológica que se encuentra en el oeste de Sydney y que se depositó en conexión con un gran delta fluvial durante el Triásico Medio . La pizarra Wianamatta generalmente comprende rocas sedimentarias de grano fino como pizarras, lutitas , piedras de hierro , limolitas y laminitas , con unidades de arenisca menos comunes. [102] El Grupo Wianamatta está formado por la pizarra Bringelly , la arenisca Minchinbury y la pizarra Ashfield . [103]

Las comunidades vegetales más frecuentes en la región de Sydney son los bosques herbáceos (es decir, las sabanas ) [104] y algunas zonas de bosques esclerófilos secos , [105] que consisten en eucaliptos , casuarinas , melaleucas , corymbias y angophoras , con arbustos (normalmente acacias , callistemons , grevilleas y banksias ) y una hierba semicontinua en el sotobosque . [106] Las plantas de esta comunidad tienden a tener hojas ásperas y puntiagudas debido a la baja fertilidad del suelo . Sydney también presenta algunas áreas de bosques esclerófilos húmedos en las áreas más húmedas y elevadas del norte y el noreste . Estos bosques se definen por copas de árboles altos y rectos con un sotobosque húmedo de arbustos de hojas suaves, helechos arborescentes y hierbas. [107]

La comunidad vegetal predominante en Sydney es el bosque de la llanura de Cumberland en el oeste de Sydney ( Cumberland Plain ), [108] seguido por el bosque de trementina y corteza de hierro de Sydney en el oeste interior y el norte de Sydney , [109] el matorral de Banksia de los suburbios orientales en la costa y el bosque alto de eucalipto azul escasamente presente en la costa norte, todos los cuales están en peligro crítico de extinción. [110] [111] La ciudad también incluye el bosque de la cima de la cresta de arenisca de Sydney que se encuentra en el Parque Nacional Ku-ring-gai Chase en la meseta de Hornsby al norte. [112]

Sydney es el hogar de docenas de especies de aves , [113] que comúnmente incluyen el cuervo australiano , la urraca australiana , la paloma crestada , el minero ruidoso y el currawong pío . Las especies de aves introducidas que se encuentran ubicuamente en Sydney son el miná común , el estornino pinto , el gorrión doméstico y la paloma moteada . [114] Las especies de reptiles también son numerosas e incluyen predominantemente eslizones . [115] [116] Sydney tiene algunas especies de mamíferos y arañas , como el zorro volador de cabeza gris y el zorro de Sydney , respectivamente, [117] [118] y tiene una gran diversidad de especies marinas que habitan su puerto y playas. [119]

Según la clasificación de Köppen-Geiger , Sídney tiene un clima subtropical húmedo ( Cfa ) [120] con veranos "cálidos, a veces calurosos" e inviernos "generalmente templados", [121] [122] [123] a "fríos". [124] El Niño-Oscilación del Sur , el Dipolo del Océano Índico y el Modo Anular del Sur [125] [126] desempeñan un papel importante en la determinación de los patrones climáticos de Sídney: sequía e incendios forestales por un lado, y tormentas e inundaciones por el otro, asociados con las fases opuestas de la oscilación en Australia . El clima se modera por la proximidad al océano, y se registran temperaturas más extremas en los suburbios occidentales del interior. [127]

En la principal estación meteorológica de Sídney, en Observatory Hill , las temperaturas extremas han oscilado entre los 45,8 °C (114,4 °F) del 18 de enero de 2013 y los 2,1 °C (35,8 °F) del 22 de junio de 1932. [128] [129] [130] En promedio, 14,9 días al año tienen temperaturas iguales o superiores a 30 °C (86 °F) en el distrito comercial central (CBD). [127] En contraste, el área metropolitana tiene un promedio de entre 35 y 65 días, dependiendo del suburbio. [131] El día más caluroso en el área metropolitana ocurrió en Penrith el 4 de enero de 2020, donde se registró una máxima de 48,9 °C (120,0 °F). [132] La temperatura media anual del mar oscila entre los 18,5 °C (65,3 °F) en septiembre y los 23,7 °C (74,7 °F) en febrero. [133] Sídney tiene una media de 7,2 horas de sol al día [134] y 109,5 días despejados al año. [4] Debido a su ubicación en el interior, en el oeste de Sídney se registran heladas a primera hora de la mañana unas cuantas veces en invierno. El otoño y la primavera son estaciones de transición, y la primavera muestra una mayor variación de temperatura que el otoño. [135]

Sydney experimenta un efecto de isla de calor urbano . [136] Esto hace que ciertas partes de la ciudad sean más vulnerables al calor extremo, incluidos los suburbios costeros. [136] [137] A fines de la primavera y el verano, las temperaturas superiores a 35 °C (95 °F) no son infrecuentes, [138] aunque las condiciones cálidas y secas generalmente terminan con un Buster del sur , [139] un poderoso viento del sur que trae vientos huracanados y una rápida caída de la temperatura. [140] Dado que Sydney está a sotavento de la Gran Cordillera Divisoria , ocasionalmente experimenta vientos foehn secos del oeste, típicamente en invierno y principios de la primavera (que son la razón de sus temperaturas máximas cálidas). [141] [142] [143] Los vientos del oeste son intensos cuando los Rugientes Cuarenta (o el Modo Anular del Sur ) se desplazan hacia el sureste de Australia, [144] donde pueden dañar hogares y afectar los vuelos , además de hacer que la temperatura parezca más fría de lo que realmente es . [145] [146]

Las precipitaciones tienen una variabilidad moderada a baja y han sido históricamente bastante uniformes durante todo el año, aunque en los últimos años han sido más predominantes en verano y erráticas. [147] [148] [149] [150] Las precipitaciones suelen ser más altas en verano hasta otoño, [122] y más bajas a fines del invierno hasta principios de la primavera. [125] [151] [127] [152] A fines del otoño y el invierno, las bajas temperaturas de la costa este pueden traer grandes cantidades de lluvia, especialmente en el CBD. [153] En la estación cálida , los nordestes negros suelen ser la causa de eventos de fuertes lluvias, aunque otras formas de áreas de baja presión , incluidos los restos de ex ciclones , también pueden traer fuertes diluvios y tormentas eléctricas vespertinas. [154] [155] La última vez que se informó de nevadas fue en 1836, aunque muchos confundieron una caída de granizo blando en la costa norte superior con nieve en julio de 2008. [ 156 ] En 2009, las condiciones secas trajeron una severa tormenta de polvo hacia la ciudad . [157] [158]

La Comisión del Gran Sídney divide a Sídney en tres "ciudades" y cinco "distritos" en función de las 33 áreas locales de gobierno del área metropolitana. La "metrópolis de tres ciudades" comprende Eastern Harbour City , Central River City y Western Parkland City . [164] La Oficina Australiana de Estadísticas también incluye a la ciudad de Central Coast (la antigua Gosford City y Wyong Shire) como parte del Gran Sídney para los recuentos de población, [165] sumando 330.000 personas. [166]

El CBD se extiende unos 3 km (1,9 mi) al sur de Sydney Cove . Está bordeado por Farm Cove dentro del Royal Botanic Garden al este y Darling Harbour al oeste. Los suburbios que rodean el CBD incluyen Woolloomooloo y Potts Point al este, Surry Hills y Darlinghurst al sur, Pyrmont y Ultimo al oeste, y Millers Point y The Rocks al norte. La mayoría de estos suburbios miden menos de 1 km2 ( 0,4 millas cuadradas) de área. El CBD de Sídney se caracteriza por calles y vías estrechas, creadas en sus inicios de convictos. [167]

Existen varias localidades, distintas de los suburbios, en todo el interior de Sídney. Central y Circular Quay son centros de transporte con intercambiadores de ferry, tren y autobús. Chinatown , Darling Harbour y Kings Cross son lugares importantes para la cultura, el turismo y la recreación. Strand Arcade , ubicada entre Pitt Street Mall y George Street , es una galería comercial histórica de estilo victoriano . Inaugurada el 1 de abril de 1892, sus frentes de tiendas son una réplica exacta de las fachadas comerciales internas originales. [168] Westfield Sydney , ubicado debajo de la Sydney Tower , es el centro comercial más grande por área en Sídney. [169]

Desde finales del siglo XX, ha habido una tendencia a la gentrificación entre los suburbios interiores de Sydney. Pyrmont, ubicado en el puerto, fue reurbanizado de un centro de envío y comercio internacional a un área de viviendas de alta densidad , alojamiento turístico y juegos de azar. [170] Originalmente ubicado bastante fuera de la ciudad, Darlinghurst es la ubicación de la histórica Darlinghurst Gaol , la fabricación y la vivienda mixta. Durante un período fue conocido como un área de prostitución . La vivienda estilo terraza se ha conservado en gran medida y Darlinghurst ha experimentado una gentrificación significativa desde la década de 1980. [171] [172] [173]

Green Square es una antigua zona industrial de Waterloo que está en proceso de renovación urbana por valor de 8.000 millones de dólares. En el límite del puerto de la ciudad, el suburbio histórico y los muelles de Millers Point se están construyendo como la nueva zona de Barangaroo . [174] [175] El suburbio de Paddington es conocido por sus casas adosadas restauradas , Victoria Barracks y sus tiendas, incluidos los mercados semanales de Oxford Street. [176]

.jpg/440px-Newtown_NSW,_Cnr_King_Street_&_Enmore_Road,_2019_(cropped).jpg)

El Inner West generalmente incluye el Inner West Council , el municipio de Burwood , el municipio de Strathfield y la ciudad de Canada Bay . Estos se extienden hasta unos 11 km al oeste del CBD. Históricamente, especialmente antes de la construcción del Harbour Bridge, [177] los suburbios exteriores del Inner West, como Strathfield, eran la ubicación de las fincas "rurales" para las élites de la colonia. Por el contrario, los suburbios interiores del Inner West, al estar cerca del transporte y la industria, históricamente han albergado a trabajadores industriales de clase trabajadora. Estas áreas han sufrido una gentrificación a fines del siglo XX y muchas partes ahora son suburbios residenciales muy valorados. [178] A partir de 2021, un suburbio del Inner West (Strathfield) seguía siendo uno de los 20 códigos postales más caros de Australia por precio medio de la vivienda (los demás estaban todos en el área metropolitana de Sídney, todos en el norte de Sídney o en los suburbios del este). [179] La Universidad de Sydney se encuentra en esta zona, así como la Universidad Tecnológica de Sydney y un campus de la Universidad Católica Australiana . El puente Anzac cruza la bahía Johnstons y conecta Rozelle con Pyrmont y la ciudad, formando parte del distribuidor occidental .

Hoy en día, el Inner West es bien conocido por ser la ubicación de centros comerciales con aires cosmopolitas, como los centros comerciales "Little Italy" de Leichardt, Five Dock y Haberfield, [180] "Little Portugal" en Petersham, [181] "Little Korea" en Strathfield [182] o "Little Shanghai" en Ashfield. [183] Los centros comerciales a gran escala de la zona incluyen Westfield Burwood , DFO Homebush y Birkenhead Point Outlet Centre . Hay una gran comunidad cosmopolita y un centro de vida nocturna en King Street en Newtown .

La zona cuenta con servicio de las líneas ferroviarias T1 , T2 y T3 , incluida la línea suburbana principal , que fue la primera que se construyó en Nueva Gales del Sur. La estación de tren de Strathfield es un centro ferroviario secundario dentro de Sídney y una estación principal en las líneas suburbana y norte . Se construyó en 1876. [184] El futuro Sydney Metro West también conectará esta zona con la ciudad y Parramatta. La zona también cuenta con servicio de los servicios fluviales Parramatta de Sydney Ferries , [185] numerosas rutas de autobús y ciclovías. [186]

Bellevue_Hill_from_Point_Piper.jpg/440px-(1)Bellevue_Hill_from_Point_Piper.jpg)

Los suburbios orientales abarcan el municipio de Woollahra , la ciudad de Randwick , el consejo municipal de Waverley y partes del consejo de Bayside . Incluyen algunas de las áreas más ricas y favorecidas del país, y algunas calles se encuentran entre las más caras del mundo. En 2014, Wolseley Road , Point Piper , tenía un precio máximo de $ 20,900 por metro cuadrado, lo que la convierte en la novena calle más cara del mundo. [188] Más del 75% de los vecindarios en el distrito electoral de Wentworth se encuentran dentro del decil superior de ventaja SEIFA, lo que lo convierte en el área menos desfavorecida del país. [189] En 2021, de los 20 códigos postales más caros de Australia por precio medio de la vivienda, nueve estaban en los suburbios orientales. [179]

Los principales lugares de interés incluyen Bondi Beach , que se agregó a la Lista del Patrimonio Nacional de Australia en 2008; [190] y Bondi Junction , que cuenta con un centro comercial Westfield y una fuerza laboral de oficina estimada en 6400 para 2035, [191] así como una estación de tren en la línea T4 Eastern Suburbs . El suburbio de Randwick contiene el hipódromo de Randwick , el Royal Hospital for Women , el Prince of Wales Hospital , el Sydney Children's Hospital y el campus de Kensington de la Universidad de Nueva Gales del Sur . [192]

La construcción del tren ligero del CBD y el sureste se completó en abril de 2020. [193] El proyecto tiene como objetivo proporcionar servicios de tranvía confiables y de alta capacidad a los residentes de la ciudad y el sureste.

Los principales centros comerciales de la zona incluyen Westfield Bondi Junction y Westfield Eastgardens .

El distrito sur de Sídney incluye los suburbios de las áreas de gobierno local del Consejo del río Georges (conocidos colectivamente como St George ) y el condado de Sutherland (conocido coloquialmente como "El Condado"), en las orillas del sur del río Georges .

La península de Kurnell , cerca de Botany Bay, es el sitio del primer desembarco en la costa este realizado por James Cook en 1770. La Perouse , un suburbio histórico que lleva el nombre del navegante francés Jean-François de Galaup, conde de Lapérouse , es famoso por su antiguo puesto militar en Bare Island y el Parque Nacional de Botany Bay .

El suburbio de Cronulla , en el sur de Sídney, está cerca del Parque Nacional Real, el parque nacional más antiguo de Australia. Hurstville, un gran suburbio con edificios comerciales y residenciales de gran altura que dominan el horizonte, se ha convertido en un centro de negocios para los suburbios del sur. [194]

' Northern Sydney ' también puede incluir los suburbios de Upper North Shore , Lower North Shore y Northern Beaches .

Los suburbios del norte incluyen varios lugares emblemáticos: la Universidad Macquarie , el puente Gladesville , el puente Ryde , el centro Macquarie y el Curzon Hall en Marsfield . Esta zona incluye suburbios en las áreas de gobierno local de Hornsby Shire , el ayuntamiento de Ku-ring-gai , la ciudad de Ryde , el municipio de Hunter's Hill y partes de la ciudad de Parramatta .

La costa norte incluye los centros comerciales de North Sydney y Chatswood. North Sydney en sí consiste en un gran centro comercial, que contiene la segunda mayor concentración de edificios de gran altura en Sydney después del CBD. North Sydney está dominado por la publicidad, el marketing y los oficios asociados, con muchas grandes corporaciones que tienen oficinas.

El área de las Playas del Norte incluye Manly , uno de los destinos vacacionales más populares de Sídney durante gran parte de los siglos XIX y XX. La región también cuenta con Sydney Heads , una serie de promontorios que forman la entrada al puerto de Sídney. El área de las Playas del Norte se extiende al sur hasta la entrada de Port Jackson (puerto de Sídney), al oeste hasta Middle Harbour y al norte hasta la entrada de Broken Bay . El censo australiano de 2011 determinó que las Playas del Norte eran el distrito más blanco y monoétnico de Australia, en contraste con sus vecinos más diversos, North Shore y Central Coast . [195]

A fines de 2021, la mitad de los 20 códigos postales más caros de Australia (según el precio medio de la vivienda) se encontraban en el norte de Sídney, incluidos cuatro en las Playas del Norte, dos en la Costa Norte Inferior, tres en la Costa Norte Superior y uno a caballo entre Hunters Hill y Woolwich . [179]

El distrito de Hills generalmente se refiere a los suburbios en el noroeste de Sydney, incluidas las áreas de gobierno local de The Hills Shire , partes del Ayuntamiento de la ciudad de Parramatta y Hornsby Shire . Los suburbios y localidades reales que se consideran que están en el distrito de Hills pueden ser algo amorfos. Por ejemplo, la Sociedad Histórica del Distrito de Hills restringe su definición al área de gobierno local de Hills Shire, pero su área de estudio se extiende desde Parramatta hasta Hawkesbury. La región se llama así por su topografía comparativamente montañosa característica a medida que la llanura de Cumberland se eleva, uniéndose a la meseta de Hornsby. Windsor y Old Windsor Roads son la segunda y tercera carreteras, respectivamente, construidas en Australia. [196]

Los suburbios occidentales más grandes abarcan las áreas de Parramatta, el sexto distrito comercial más grande de Australia, establecido el mismo año que la colonia portuaria, [197] Bankstown , Liverpool, Penrith y Fairfield . Con una superficie de 5800 km² ( 2200 millas cuadradas) y una población estimada en 2017 de 2 288 554, el oeste de Sídney tiene los suburbios más multiculturales del país: Cabramatta se ha ganado el apodo de " Pequeño Saigón " debido a su población vietnamita , Fairfield ha sido llamada "Pequeña Asiria " por su población asiria predominante y Harris Park es conocido como " Pequeña India " con su pluralidad de población india e hindú . [198] [199] [200] [201] La población es predominantemente de origen obrero , con un empleo principal en las industrias pesadas y el comercio vocacional . [202] Toongabbie es conocido por ser el tercer asentamiento continental (después de Sydney y Parramatta) establecido después de que comenzara la colonización británica en 1788, aunque el sitio del asentamiento en realidad está en el suburbio separado de Old Toongabbie . [203]

El suburbio occidental de Prospect , en la ciudad de Blacktown , es el hogar de Raging Waters , un parque acuático operado por Parques Reunidos . [204] Auburn Botanic Gardens , un jardín botánico en Auburn , atrae a miles de visitantes cada año, incluidos muchos de fuera de Australia. [205] El gran oeste también incluye Sydney Olympic Park , un suburbio creado para albergar los Juegos Olímpicos de Verano de 2000, y Sydney Motorsport Park , un circuito en Eastern Creek . [206] Prospect Hill , una cresta históricamente significativa en el oeste y la única área en Sydney con actividad volcánica antigua , [207] también está incluida en el Registro de Patrimonio Estatal. [208]

Al noroeste, Featherdale Wildlife Park , un zoológico en Doonside , cerca de Blacktown , es una importante atracción turística . [209] El Zoológico de Sídney , inaugurado en 2019, es otro zoológico destacado situado en Bungaribee . [210] Establecida en 1799, la Old Government House , una casa museo histórica y lugar turístico en Parramatta, fue incluida en la Lista del Patrimonio Nacional de Australia el 1 de agosto de 2007 y en la Lista del Patrimonio Mundial en 2010 (como parte de los 11 sitios penales que constituyen los Sitios de Convictos de Australia ), lo que la convierte en el único sitio en el gran oeste de Sídney que aparece en dichas listas. [211] La casa es el edificio público más antiguo que aún se conserva en Australia. [212]

Más al suroeste se encuentra la región de Macarthur y la ciudad de Campbelltown , un importante centro de población que hasta la década de 1990 se consideraba una región separada de Sídney. Macarthur Square , un complejo comercial en Campbelltown, se ha convertido en uno de los complejos comerciales más grandes de Sídney. [213] El suroeste también cuenta con el embalse de Bankstown , el embalse elevado más antiguo construido en hormigón armado que todavía está en uso y está incluido en el Registro del Patrimonio Estatal. [214] El suroeste alberga uno de los árboles más antiguos de Sídney, el roble Bland , que fue plantado en la década de 1840 por William Bland en Carramar . [215]

Las primeras estructuras de la colonia se construyeron siguiendo los estándares mínimos. El gobernador Macquarie estableció objetivos ambiciosos para el diseño de nuevos proyectos de construcción. La ciudad ahora cuenta con un edificio declarado patrimonio mundial, varios edificios declarados patrimonio nacional y docenas de edificios declarados patrimonio de la Commonwealth como evidencia de la supervivencia de los ideales de Macquarie. [217] [218] [219]

En 1814, el gobernador llamó a un convicto llamado Francis Greenway para diseñar el faro de Macquarie . [220] El diseño clásico del faro le valió a Greenway un indulto de Macquarie en 1818 e introdujo una cultura de arquitectura refinada que permanece hasta el día de hoy. [221] Greenway diseñó el cuartel de Hyde Park en 1819 y la iglesia de St James de estilo georgiano en 1824. [222] [223] La arquitectura de inspiración gótica se hizo más popular a partir de la década de 1830. La Elizabeth Bay House de John Verge y la iglesia de St Philip de 1856 se construyeron en estilo neogótico junto con la Casa de Gobierno de Edward Blore de 1845. [224] [225] La Casa Kirribilli, terminada en 1858, y la Catedral de San Andrés, la catedral más antigua de Australia, [226] son ejemplos raros de construcción gótica victoriana . [224] [227]

Desde finales de la década de 1850 hubo un cambio hacia la arquitectura clásica. Mortimer Lewis diseñó el Museo Australiano en 1857. [228] La Oficina General de Correos , completada en 1891 en estilo clásico libre victoriano , fue diseñada por James Barnet . [229] Barnet también supervisó la reconstrucción de 1883 del faro Macquarie de Greenway. [220] [221] La Aduana se construyó en 1844. [230] El Ayuntamiento de estilo neoclásico y Segundo Imperio francés se completó en 1889. [231] [232] Los diseños románicos ganaron popularidad a partir de principios de la década de 1890. El Sydney Technical College se completó en 1893 utilizando enfoques tanto del Renacimiento románico como de la Reina Ana . [233] El edificio Queen Victoria fue diseñado en estilo Renacimiento románico por George McRae ; Terminado en 1898, [234] alberga 200 tiendas en sus tres plantas. [235]

A medida que la riqueza del asentamiento aumentó y Sydney se convirtió en una metrópolis después de la Federación en 1901, sus edificios se hicieron más altos. La primera torre de Sydney fue Culwulla Chambers, que alcanzó los 50 m (160 pies) y contaba con 12 pisos. El Commercial Traveller's Club, construido en 1908, tenía una altura similar, 10 pisos. Fue construido con una capa de piedra de ladrillo y demolido en 1972. [236] Esto anunció un cambio en el paisaje urbano de Sydney y con el levantamiento de las restricciones de altura en la década de 1960, se produjo un aumento de la construcción de edificios de gran altura. [237]

La Gran Depresión tuvo una influencia tangible en la arquitectura de Sídney. Las nuevas estructuras se volvieron más sobrias y con mucha menos ornamentación. La proeza arquitectónica más notable de este período es el Puente del Puerto. Su arco de acero fue diseñado por John Bradfield y se terminó en 1932. Un total de 39.000 toneladas de acero estructural cubren los 503 m (1.650 pies) entre Milsons Point y Dawes Point . [238] [239]

La arquitectura moderna e internacional llegó a Sídney a partir de la década de 1940. Desde su finalización en 1973, la Ópera de la ciudad se ha convertido en Patrimonio de la Humanidad y una de las piezas de diseño moderno más famosas del mundo. Jørn Utzon recibió el Premio Pritzker en 2003 por su trabajo en la Ópera. [240] Sídney alberga el primer edificio de Australia del reconocido arquitecto canadiense-estadounidense Frank Gehry , el Dr Chau Chak Wing Building (2015). Una entrada desde The Goods Line , un sendero peatonal y antigua línea ferroviaria, se encuentra en el límite este del sitio.

Los edificios contemporáneos en el CBD incluyen Citigroup Centre , [241] Aurora Place , [242] Chifley Tower , [243] [244] el edificio del Reserve Bank , [245] Deutsche Bank Place , [246] MLC Centre , [247] y Capita Centre . [248] La estructura más alta es Sydney Tower , diseñada por Donald Crone y terminada en 1981. [249] Debido a la proximidad del Aeropuerto de Sídney , se impuso una restricción de altura máxima, que ahora se encuentra en 330 metros (1083 pies). [250] Las prohibiciones verdes y las superposiciones patrimoniales han estado en vigor al menos desde 1977 para proteger el patrimonio de Sídney después de las controvertidas demoliciones en la década de 1970. [251]

Sydney supera los precios inmobiliarios de Nueva York y París, con algunos de los más caros del mundo. [252] [253] La ciudad sigue siendo el mercado inmobiliario más caro de Australia, con un precio medio de la vivienda de 1.142.212 dólares a diciembre de 2019 (más del 25 % más alto que el precio medio nacional de la vivienda). [254] Solo es superada por Hong Kong, con un coste medio de la propiedad 14 veces el salario anual de Sydney a diciembre de 2016. [255]

En 2016, había en Sídney 1,76 millones de viviendas, incluidas 925 000 (57 %) casas unifamiliares, 227 000 (14 %) casas adosadas adosadas y 456 000 (28 %) unidades y apartamentos. [256] Si bien las casas adosadas son comunes en las áreas del centro de la ciudad, las casas unifamiliares dominan el paisaje en los suburbios exteriores. Debido a las presiones ambientales y económicas, se ha observado una tendencia hacia una mayor densidad de viviendas, con un aumento del 30 % en el número de apartamentos entre 1996 y 2006. [257] La vivienda pública en Sídney está gestionada por el Gobierno de Nueva Gales del Sur . [258] Los suburbios con grandes concentraciones de vivienda pública incluyen Claymore , Macquarie Fields , Waterloo y Mount Druitt .

En Sydney se puede encontrar una variedad de estilos de viviendas patrimoniales. Las casas adosadas se encuentran en los suburbios interiores como Paddington , The Rocks , Potts Point y Balmain , muchas de las cuales han sido objeto de gentrificación . [259] [260] Estas casas adosadas, particularmente las de los suburbios como The Rocks, fueron históricamente el hogar de los mineros y trabajadores de Sydney. En la actualidad, las casas adosadas constituyen algunas de las propiedades inmobiliarias más valiosas de la ciudad. [261] Las grandes mansiones sobrevivientes de la era victoriana se encuentran principalmente en los suburbios más antiguos, como Double Bay , Darling Point , Rose Bay y Strathfield . [262]

Las casas de la Federación , construidas alrededor de la época de la Federación en 1901, están ubicadas en una gran cantidad de suburbios que se desarrollaron gracias a la llegada de los ferrocarriles a fines del siglo XIX, como Penshurst y Turramurra , y en "suburbios de jardín" planificados a gran escala como Haberfield . Las cabañas de los trabajadores se encuentran en Surry Hills , Redfern y Balmain. Los bungalows de California son comunes en Ashfield , Concord y Beecroft . Las casas modernas más grandes se encuentran predominantemente en los suburbios exteriores, como Stanhope Gardens , Kellyville Ridge , Bella Vista al noroeste, Bossley Park , Abbotsbury y Cecil Hills al oeste, y Hoxton Park , Harrington Park y Oran Park al suroeste. [263]

El Memorial de la Guerra de Anzac en Hyde Park es un monumento público dedicado a la Fuerza Imperial Australiana de la Primera Guerra Mundial .

El Real Jardín Botánico es el espacio verde más emblemático de la región y alberga actividades científicas y de ocio. [264] Hay 15 parques separados bajo la administración de la ciudad. [265] Los parques dentro del centro de la ciudad incluyen Hyde Park , The Domain y Prince Alfred Park.

.jpg/440px-Centennial_Park_NSW_2021,_Australia_-_panoramio_(7).jpg)

Centennial Parklands es el parque más grande de la ciudad de Sydney, con una extensión de 189 ha (470 acres).

Los suburbios interiores incluyen Centennial Park y Moore Park en el este (ambos dentro del área de gobierno local de la ciudad de Sídney), mientras que los suburbios exteriores contienen Sydney Park y Royal National Park en el sur, Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park en el norte y Western Sydney Parklands en el oeste, que es uno de los parques urbanos más grandes del mundo. El Royal National Park fue proclamado en 1879 y con 13.200 ha (51 millas cuadradas) es el segundo parque nacional más antiguo del mundo. [267]

Hyde Park es el parque más antiguo del país. [269] El parque más grande del área metropolitana de Sídney es el Parque Nacional Ku-ring-gai Chase, establecido en 1894 con una superficie de 15.400 ha (59 millas cuadradas). [270] Es reconocido por sus registros bien conservados de habitación indígena: más de 800 grabados rupestres, dibujos rupestres y basureros. [271]

El área ahora conocida como The Domain fue reservada por el gobernador Arthur Phillip en 1788 como su reserva privada. [272] Bajo las órdenes de Macquarie, la tierra al norte inmediato de The Domain se convirtió en el Jardín Botánico Real en 1816. Esto los convierte en el jardín botánico más antiguo de Australia. [272] Los jardines albergan investigaciones científicas con colecciones de herbario, una biblioteca y laboratorios. [273] Los dos parques tienen un área total de 64 ha (0,2 millas cuadradas) con 8.900 especies de plantas individuales y reciben más de 3,5 millones de visitas anuales. [274]

Al sur de The Domain se encuentra Hyde Park, el parque público más antiguo de Australia, que mide 16,2 ha (0,1 millas cuadradas). [275] Su ubicación se utilizó tanto para la relajación como para el pastoreo de animales desde los primeros días de la colonia. [276] Macquarie lo dedicó en 1810 para la "recreación y diversión de los habitantes de la ciudad" y lo nombró en honor a Hyde Park en Londres .

Los investigadores de la Universidad de Loughborough han clasificado a Sydney entre las diez ciudades más importantes del mundo que están altamente integradas en la economía global. [278] El Índice de Poder Económico Global clasifica a Sydney en el undécimo lugar del mundo. [279] El Índice de Ciudades Globales la reconoce como el decimocuarto lugar del mundo en términos de participación global. [280] Hay una concentración significativa de bancos extranjeros y corporaciones multinacionales en Sydney y la ciudad se promociona como la capital financiera de Australia y uno de los principales centros financieros de Asia Pacífico . [281] [282]

La teoría económica predominante durante los primeros días coloniales era el mercantilismo , como lo fue en la mayor parte de Europa occidental. [283] La economía tuvo dificultades al principio debido a las dificultades para cultivar la tierra y la falta de un sistema monetario estable. El gobernador Macquarie creó dos monedas de cada dólar de plata español en circulación. [283] La economía era de naturaleza capitalista en la década de 1840 a medida que aumentaba la proporción de colonos libres, florecían las industrias marítima y de la lana y se restringían los poderes de la Compañía de las Indias Orientales . [283]

El trigo, el oro y otros minerales se convirtieron en industrias de exportación hacia finales del siglo XIX. [283] A partir de la década de 1870, comenzó a fluir un capital significativo a la ciudad para financiar carreteras, ferrocarriles, puentes, muelles, juzgados, escuelas y hospitales. Las políticas proteccionistas posteriores a la federación permitieron la creación de una industria manufacturera que se convirtió en el mayor empleador de la ciudad en la década de 1920. [283] Estas mismas políticas ayudaron a aliviar los efectos de la Gran Depresión durante la cual la tasa de desempleo en Nueva Gales del Sur alcanzó un máximo del 32%. [283] A partir de la década de 1960, Parramatta ganó reconocimiento como el segundo CBD de la ciudad y las finanzas y el turismo se convirtieron en industrias importantes y fuentes de empleo. [283]

El producto interno bruto nominal de Sídney fue de 400,9 mil millones de dólares australianos y de 80 000 dólares australianos per cápita [284] en 2015. [285] [282] Su producto interno bruto fue de 337 mil millones de dólares australianos en 2013, el más alto de Australia. [285] La industria de servicios financieros y de seguros representa el 18,1% del producto bruto, por delante de los servicios profesionales con el 9% y la industria manufacturera con el 7,2%. Los sectores creativo y tecnológico también son industrias de enfoque para la ciudad de Sídney y representaron el 9% y el 11% de su producción económica en 2012. [286] [287]

En 2011, había 451.000 empresas radicadas en Sídney, incluidas el 48% de las 500 empresas más importantes de Australia y dos tercios de las sedes regionales de corporaciones multinacionales. [288] Las empresas globales se sienten atraídas por la ciudad en parte porque su zona horaria abarca el cierre de negocios en América del Norte y la apertura de negocios en Europa. La mayoría de las empresas extranjeras en Sídney mantienen importantes funciones de ventas y servicios, pero comparativamente menos capacidades de producción, investigación y desarrollo. [289] Hay 283 empresas multinacionales con oficinas regionales en Sídney. [290]

Sydney ha sido clasificada entre la decimoquinta y la quinta ciudad más cara del mundo y es la ciudad más cara de Australia. [292] De las 15 categorías medidas únicamente por UBS en 2012, los trabajadores reciben los séptimos niveles salariales más altos de 77 ciudades del mundo. [292] Los residentes trabajadores de Sydney trabajan un promedio de 1.846 horas al año con 15 días de licencia. [292]

La fuerza laboral de la región del Gran Sídney en 2016 era de 2.272.722 con una tasa de participación del 61,6%. [293] Comprendía un 61,2% de trabajadores a tiempo completo, un 30,9% de trabajadores a tiempo parcial y un 6,0% de personas desempleadas. [256] [294] Las ocupaciones más importantes informadas son profesionales, empleados administrativos y de oficina, gerentes, técnicos y trabajadores de oficios, y trabajadores de servicios comunitarios y personales. [256] Las industrias más grandes por empleo en el Gran Sídney son la atención médica y la asistencia social (11,6%), los servicios profesionales (9,8%), el comercio minorista (9,3%), la construcción (8,2%), la educación y la capacitación (8,0%), los servicios de alojamiento y alimentación (6,7%) y los servicios financieros y de seguros (6,6%). [2] Las industrias de servicios profesionales y servicios financieros y de seguros representan el 25,4% del empleo dentro de la ciudad de Sídney. [295]

En 2016, el 57,6% de los residentes en edad laboral tenían un ingreso semanal de menos de $1000 y el 14,4% tenían un ingreso semanal de $1750 o más. [296] El ingreso semanal medio para el mismo período fue de $719 para individuos, $1988 para familias y $1750 para hogares. [297]

El desempleo en la ciudad de Sídney fue en promedio del 4,6% durante la década hasta 2013, mucho menor que la tasa actual de desempleo en el oeste de Sídney, del 7,3%. [282] [298] El oeste de Sídney sigue luchando por crear empleos para satisfacer su crecimiento demográfico a pesar del desarrollo de centros comerciales como Parramatta. Cada día, unos 200.000 viajeros viajan desde el oeste de Sídney hasta el centro comercial central y los suburbios del este y el norte de la ciudad. [298]

Antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la propiedad de una vivienda en Sydney era menos común que el alquiler, pero esta tendencia se ha revertido desde entonces. [257] Los precios medios de las viviendas han aumentado una media del 8,6% anual desde 1970. [299] [300] El precio medio de la vivienda en marzo de 2014 era de 630.000 dólares. [301] La causa principal del aumento de los precios es el aumento del coste de la tierra y su escasez. [302] El 31,6% de las viviendas de Sydney se alquilan, el 30,4% son de propiedad absoluta y el 34,8% son de propiedad hipotecada. [256] El 11,8% de los hipotecados en 2011 tenían cuotas mensuales de préstamos inferiores a 1.000 dólares y el 82,9% tenían cuotas mensuales de 1.000 dólares o más. [2] El 44,9% de los inquilinos durante el mismo período tenían un alquiler semanal de menos de $350, mientras que el 51,7% tenía un alquiler semanal de $350 o más. El alquiler semanal medio en Sydney en 2011 fue de $450. [2]

Commonwealth_Bank_Martin_Place.jpg/440px-(1)Commonwealth_Bank_Martin_Place.jpg)

En 1817, Macquarie otorgó una carta fundacional para fundar el primer banco de Australia, el Banco de Nueva Gales del Sur . [303] A lo largo del siglo XIX se abrieron nuevos bancos privados, pero el sistema financiero era inestable. Los colapsos bancarios eran frecuentes y en 1893 se alcanzó un punto crítico cuando quebraron 12 bancos. [303]

El Banco de Nueva Gales del Sur existe hasta el día de hoy como Westpac . [304] El Commonwealth Bank of Australia se formó en Sydney en 1911 y comenzó a emitir billetes respaldados por los recursos de la nación. Fue reemplazado en esta función en 1959 por el Banco de la Reserva de Australia , también con sede en Sydney. [303] La Bolsa de Valores de Australia comenzó a operar en 1987 y, con una capitalización de mercado de $1,6 billones, ahora es una de las diez bolsas más grandes del mundo. [305]

La industria de servicios financieros y de seguros ahora constituye el 43% del producto económico de la ciudad de Sídney. [281] Sídney representa la mitad del sector financiero de Australia y ha sido promovida por sucesivos gobiernos de la Commonwealth como el principal centro financiero de Asia Pacífico . [20] [21] [306] En el Índice de Centros Financieros Globales de 2017 , Sídney fue clasificada como el octavo centro financiero más competitivo del mundo. [307]

En 1985, el Gobierno Federal concedió 16 licencias bancarias a bancos extranjeros y ahora 40 de los 43 bancos extranjeros que operan en Australia tienen su sede en Sídney, entre ellos el Banco Popular de China , el Bank of America , Citigroup , UBS , Mizuho Bank , el Bank of China , el Banco Santander , el Credit Suisse , Standard Chartered , State Street , HSBC , Deutsche Bank , Barclays , Royal Bank of Canada , Société Générale , Royal Bank of Scotland , Sumitomo Mitsui , ING Group , BNP Paribas e Investec . [281] [303] [308] [309]

Sydney ha sido una ciudad manufacturera desde la década de 1920. Para 1961, la industria representaba el 39% de todo el empleo y para 1970 más del 30% de todos los empleos manufactureros australianos estaban en Sydney. [310] Su estatus ha disminuido en las últimas décadas, representando el 12,6% del empleo en 2001 y el 8,5% en 2011. [2] [310] Entre 1970 y 1985 hubo una pérdida de 180.000 empleos manufactureros. [310] A pesar de esto, Sydney todavía superó a Melbourne como el centro manufacturero más grande de Australia en la década de 2010, [311] con una producción manufacturera de $ 21,7 mil millones en 2013. [312] Los observadores han acreditado el enfoque de Sydney en el mercado interno y la fabricación de alta tecnología por su resistencia frente al alto dólar australiano de principios de la década de 2010. [312] El polígono industrial Smithfield-Wetherill Park, en el oeste de Sydney, es el más grande del hemisferio sur y el centro de fabricación y distribución de la región. [313]

.jpg/440px-2021-04-30_Darling_Harbour_panorama_(cropped).jpg)

Sídney es una puerta de entrada a Australia para muchos visitantes internacionales y se encuentra entre las sesenta ciudades más visitadas del mundo. [314] Ha recibido más de 2,8 millones de visitantes internacionales en 2013, o casi la mitad de todas las visitas internacionales a Australia. Estos visitantes pasaron 59 millones de noches en la ciudad y gastaron un total de 5.900 millones de dólares. [24] Los países de origen en orden descendente fueron China, Nueva Zelanda, el Reino Unido, los Estados Unidos, Corea del Sur, Japón, Singapur, Alemania, Hong Kong y la India. [315]

The city also received 8.3 million domestic overnight visitors in 2013 who spent a total of $6 billion.[315] 26,700 workers in the City of Sydney were directly employed by tourism in 2011.[316] There were 480,000 visitors and 27,500 people staying overnight each day in 2012.[316] On average, the tourism industry contributes $36 million to the city's economy per day.[316]

Popular destinations include the Sydney Opera House, the Sydney Harbour Bridge, Watsons Bay, The Rocks, Sydney Tower, Darling Harbour, the Royal Botanic Garden, the Australian Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Queen Victoria Building, Sea Life Sydney Aquarium, Taronga Zoo, Bondi Beach, Luna Park and Sydney Olympic Park.[317]

Major developmental projects designed to increase Sydney's tourism sector include a casino and hotel at Barangaroo and the redevelopment of East Darling Harbour, which involves a new exhibition and convention centre, now Australia's largest.[318][319][320]

Sydney is the highest-ranking city in the world for international students. More than 50,000 international students study at the city's universities and a further 50,000 study at its vocational and English language schools.[280][321] International education contributes $1.6 billion to the local economy and creates demand for 4,000 local jobs each year.[322]

In 2023, Sydney was ranked the least affordable city to buy a house in Australia and the second least affordable city in the world, after Hong Kong,[323] with the average Sydney house price in late 2023 costing A$1.59 million, and the average unit price costing A$795,000.[324] As of early 2024, Sydney is often described in the media as having a housing shortage, or suffering a housing crisis.[325][326]

The population of Sydney in 1788 was less than 1,000.[328] With convict transportation it almost tripled in ten years to 2,953.[329] For each decade since 1961 the population has increased by more than 250,000.[330] The 2021 census recorded the population of Greater Sydney as 5,231,150.[1] The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) projects the population will grow to between 8 and 8.9 million by 2061, but that Melbourne will replace Sydney as Australia's most populous city by 2030.[331][332] The four most densely populated suburbs in Australia are located in Sydney with each having more than 13,000 residents per square kilometre (33,700 residents per square mile).[333] Between 1971 and 2018, Sydney experienced a net loss of 716,832 people to the rest of Australia, but its population grew due to overseas arrivals and a healthy birth rate.[334]

The median age of Sydney residents is 37 and 14.8% of people are 65 or older.[256] 48.6% of Sydney's population is married whilst 36.7% have never been married.[256] 49.0% of families are couples with children, 34.4% are couples without children, and 14.8% are single-parent families.[256]

Most immigrants to Sydney between 1840 and 1930 were British, Irish or Chinese. At the 2021 census, the most common ancestries were:[11]

At the 2021 census, 40.5% of Sydney's population was born overseas. Foreign countries of birth with the greatest representation are Mainland China, India, England, Vietnam, Philippines and New Zealand.[11]

At the 2021 census, 1.7% of Sydney's population identified as being Indigenous — Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders.[N 3][337]

42% of households in Sydney use a language other than English, with the most common being Mandarin (5%), Arabic (4.2%), Cantonese (2.8%), Vietnamese (2.2%) and Hindi (1.5%).[337]

In 2021, Christianity was the largest religious affiliation at 46%, the largest denominations of which were Catholicism at 23.1% and Anglicanism at 9.2%. 30.3% of Sydney residents identified as having no religion. The most common non-Christian religious affiliations were Islam (6.3%), Hinduism (4.8%), Buddhism (3.8%), Sikhism (0.7%), and Judaism (0.7%). About 500 people identified with traditional Aboriginal religions.[11]

The Church of England was the only recognised church before Governor Macquarie appointed official Catholic chaplains in 1820.[338] Macquarie also ordered the construction of churches such as St Matthew's, St Luke's, St James's, and St Andrew's. Religious groups, alongside secular institutions, have played a significant role in education, health and charitable services throughout Sydney's history.[339]

Crime in Sydney is low, with The Independent ranking Sydney as the fifth safest city in the world in 2019.[340] However, drug use is a significant problem. Methamphetamine is heavily consumed compared to other countries, while heroin is less common.[341] One of the biggest crime-related issues in recent times was the introduction of lockout laws in February 2014,[342] in an attempt to curb alcohol-fuelled violence. Patrons could not enter clubs or bars in the inner-city after 1:30am, and last drinks were called at 3am. The lockout laws were removed in January 2020.[343]

Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park is rich in Indigenous Australian heritage, containing around 1,500 pieces of Aboriginal rock art – the largest cluster of Indigenous sites in Australia. The park's indigenous sites include petroglyphs, art sites, burial sites, caves, marriage areas, birthing areas, midden sites, and tool manufacturing locations, which are dated to be around 5,000 years old. The inhabitants of the area were the Garigal people.[344][345] Other rock art sites exist in the Sydney region, such as in Terrey Hills and Bondi, although the locations of most are not publicised to prevent damage by vandalism, and to retain their quality, as they are still regarded as sacred sites by Indigenous Australians.[346]

The Australian Museum opened in Sydney in 1827 with the purpose of collecting and displaying the natural wealth of the colony.[347] It remains Australia's oldest natural history museum. In 1995 the Museum of Sydney opened on the site of the first Government House. It recounts the story of the city's development.[348] Other museums include the Powerhouse Museum and the Australian National Maritime Museum.[349][350]

The State Library of New South Wales holds the oldest library collections in Australia, being established as the Australian Subscription Library in 1826.[351] The Royal Society of New South Wales, formed in 1866, encourages "studies and investigations in science, art, literature, and philosophy". It is based in a terrace house in Darlington owned by the University of Sydney.[352] The Sydney Observatory building was constructed in 1859 and used for astronomy and meteorology research until 1982 before being converted into a museum.[353]

The Museum of Contemporary Art was opened in 1991 and occupies an Art Deco building in Circular Quay. Its collection was founded in the 1940s by artist and art collector John Power and has been maintained by the University of Sydney.[354] Sydney's other significant art institution is the Art Gallery of New South Wales which coordinates the Archibald Prize for portraiture.[355] Sydney is also home to contemporary art gallery Artspace, housed in the historic Gunnery Building in Woolloomooloo, fronting Sydney Harbour.[356]

Sydney's first commercial theatre opened in 1832 and nine more had commenced performances by the late 1920s. The live medium lost much of its popularity to the cinema during the Great Depression before experiencing a revival after World War II.[357] Prominent theatres in the city today include State Theatre, Theatre Royal, Sydney Theatre, The Wharf Theatre, and Capitol Theatre. Sydney Theatre Company maintains a roster of local, classical, and international plays. It occasionally features Australian theatre icons such as David Williamson, Hugo Weaving, and Geoffrey Rush. The city's other prominent theatre companies are New Theatre, Belvoir, and Griffin Theatre Company. Sydney is also home to Event Cinemas' first theatre, which opened on George St in 1913, under its former Greater Union brand; the theatre currently operates, and is regarded as one of Australia's busiest cinema locations.

The Sydney Opera House is the home of Opera Australia and Sydney Symphony. It has staged over 100,000 performances and received 100 million visitors since opening in 1973.[240] Two other important performance venues in Sydney are Town Hall and the City Recital Hall. The Sydney Conservatorium of Music is located adjacent to the Royal Botanic Garden and serves the Australian music community through education and its biannual Australian Music Examinations Board exams.[358]

Many writers have originated in and set their work in Sydney. Others have visited the city and commented on it. Some of them are commemorated in the Sydney Writers Walk at Circular Quay. The city was the headquarters for Australia's first published newspaper, the Sydney Gazette.[359] Watkin Tench's A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay (1789) and A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson in New South Wales (1793) have remained the best-known accounts of life in early Sydney.[360] Since the infancy of the establishment, much of the literature set in Sydney were concerned with life in the city's slums and working-class communities, notably William Lane's The Working Man's Paradise (1892), Christina Stead's Seven Poor Men of Sydney (1934) and Ruth Park's The Harp in the South (1948).[361] The first Australian-born female novelist, Louisa Atkinson, set several novels in Sydney.[362] Contemporary writers, such as Elizabeth Harrower, were born in the city and set most of their work there–Harrower's debut novel Down in the City (1957) was mostly set in a King's Cross apartment.[363][364][365] Well known contemporary novels set in the city include Melina Marchetta's Looking for Alibrandi (1992), Peter Carey's 30 Days in Sydney: A Wildly Distorted Account (1999), J. M. Coetzee's Diary of a Bad Year (2007) and Kate Grenville's The Secret River (2010). The Sydney Writers' Festival is held annually between April and May.[366]

Filmmaking in Sydney was prolific until the 1920s when spoken films were introduced and American productions gained dominance.[367] The Australian New Wave saw a resurgence in film production, with many notable features shot in the city between the 1970s and 80s, helmed by directors such as Bruce Beresford, Peter Weir and Gillian Armstrong.[368] Fox Studios Australia commenced production in Sydney in 1998. Successful films shot in Sydney since then include The Matrix, Lantana, Mission: Impossible 2, Moulin Rouge!, Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, Australia, Superman Returns, and The Great Gatsby. The National Institute of Dramatic Art is based in Sydney and has several famous alumni such as Mel Gibson, Judy Davis, Baz Luhrmann, Cate Blanchett, Hugo Weaving and Jacqueline Mckenzie.[369]

Sydney hosts several festivals throughout the year. The city's New Year's Eve celebrations are the largest in Australia.[370] The Royal Easter Show is held every year at Sydney Olympic Park. Sydney Festival is Australia's largest arts festival.[371] The travelling rock music festival Big Day Out originated in Sydney. The city's two largest film festivals are Sydney Film Festival and Tropfest. Vivid Sydney is an annual outdoor exhibition of art installations, light projections, and music. In 2015, Sydney was ranked the 13th top fashion capital in the world.[372] It hosts the Australian Fashion Week in autumn. Sydney Mardi Gras has commenced each February since 1979.

Sydney's Chinatown has had numerous locations since the 1850s. It moved from George Street to Campbell Street to its current setting in Dixon Street in 1980.[373] Little Italy is located in Stanley Street.[283]

Restaurants, bars and nightclubs can be found in the entertainment hubs in the Sydney CBD (Darling Harbour, Barangaroo, The Rocks and George Street), Oxford Street, Surry Hills, Newtown and Parramatta.[374][375] Kings Cross was previously considered the red-light district. The Star is the city's casino and is situated next to Darling Harbour while the new Crown Sydney resort is in nearby Barangaroo.[376]

The Sydney Morning Herald is Australia's oldest newspaper still in print; it has been published continuously since 1831.[377] Its competitor is The Daily Telegraph, in print since 1879.[378] Both papers have Sunday tabloid editions called The Sun-Herald and The Sunday Telegraph respectively. The Bulletin was founded in Sydney in 1880 and became Australia's longest running magazine. It closed after 128 years of continuous publication.[379] Sydney heralded Australia's first newspaper, the Sydney Gazette, published until 1842.

Each of Australia's three commercial television networks and two public broadcasters is headquartered in Sydney. Nine's offices and news studios are in North Sydney, Ten is based in Pyrmont, and Seven is based in South Eveleigh in Redfern.[380][381][382][383] The Australian Broadcasting Corporation is located in Ultimo,[384] and the Special Broadcasting Service is based in Artarmon.[385] Multiple digital channels have been provided by all five networks since 2000. Foxtel is based in North Ryde and sells subscription cable television to most of the urban area.[386] Sydney's first radio stations commenced broadcasting in the 1920s. Radio has managed to survive despite the introduction of television and the Internet.[387] 2UE was founded in 1925 and under the ownership of Nine Entertainment is the oldest station still broadcasting.[387] Competing stations include the more popular 2GB, ABC Radio Sydney, KIIS 106.5, Triple M, Nova 96.9 and 2Day FM.[388]

Sydney's earliest migrants brought with them a passion for sport but were restricted by the lack of facilities and equipment. The first organised sports were boxing, wrestling, and horse racing from 1810 in Hyde Park.[389] Horse racing remains popular and events such as the Golden Slipper Stakes attract widespread attention. The first cricket club was formed in 1826 and matches were played within Hyde Park throughout the 1830s and 1840s.[389] Cricket is a favoured sport in summer and big matches have been held at the Sydney Cricket Ground since 1878. The New South Wales Blues compete in the Sheffield Shield league and the Sydney Sixers and Sydney Thunder contest the national Big Bash Twenty20 competition.