Somalia , oficialmente la República Federal de Somalia , es el país más oriental de África continental . El país está situado en el Cuerno de África y limita con Etiopía al oeste, Yibuti [14] al noroeste, Kenia al suroeste, el Golfo de Adén al norte y el Océano Índico al este. Somalia tiene la costa más larga del continente africano. [15] Somalia tiene una población estimada de 18,1 millones, [16] [17] [18] de los cuales 2,7 millones viven en la capital y ciudad más grande, Mogadiscio . Alrededor del 85% de sus residentes son étnicos somalíes y los idiomas oficiales del país son el somalí y el árabe , aunque el primero es el idioma principal. Somalia tiene vínculos históricos y religiosos con el mundo árabe . [19] Como tal, la gente en Somalia es musulmana , [20] la mayoría de ellos sunitas . [21]

En la antigüedad, Somalia era un importante centro comercial. [22] [23] Durante la Edad Media, varios imperios somalíes poderosos dominaron el comercio regional, incluido el Sultanato de Ajuran , el Sultanato de Adal , el Imamato de Awsame y el Sultanato de Geledi . A fines del siglo XIX, los sultanatos somalíes fueron colonizados por los imperios italiano y británico , [24] [25] [26] quienes fusionaron todos estos territorios tribales en dos colonias : Somalilandia italiana y Somalilandia británica . [27] [28] En 1960, los dos territorios se unieron para formar la República Somalí independiente bajo un gobierno civil. [29] Siad Barre del Consejo Supremo Revolucionario (SRC) tomó el poder en 1969 y estableció la República Democrática Somalí , intentando brutalmente aplastar la Guerra de Independencia de Somalilandia en el norte del país. [30] El SRC se derrumbó en 1991 con el inicio de la Guerra Civil Somalí . [31] El Gobierno Nacional de Transición de Somalia (GNT) se estableció en 2000, seguido por la formación del Gobierno Federal de Transición de Somalia (GFT) en 2004, que restableció las Fuerzas Armadas Somalíes . [1] [32]

En 2006, con una intervención etíope apoyada por Estados Unidos , el TFG asumió el control de la mayoría de las zonas de conflicto del sur de la nación de la recién formada Unión de Tribunales Islámicos (UCI). Posteriormente, la UCI se dividió en grupos más radicales, incluido el grupo yihadista al-Shabaab , que luchó contra el TFG y sus aliados de la AMISOM por el control de la región. [1] A mediados de 2012, los insurgentes habían perdido la mayor parte del territorio que habían tomado, y comenzó una búsqueda de instituciones democráticas más permanentes. [33] A pesar de esto, los insurgentes aún controlan gran parte del centro y sur de Somalia, [34] [35] y ejercen influencia en las áreas controladas por el gobierno, [35] con la ciudad de Jilib actuando como la capital de facto para los insurgentes. [34] [36] Se aprobó una nueva constitución provisional en agosto de 2012, [37] [38] reformando Somalia como una federación . [39] Ese mismo mes se formó el Gobierno Federal de Somalia [40] y comenzó un período de reconstrucción en Mogadiscio, a pesar de que Al Shabaab llevaba a cabo con frecuencia ataques allí . [33] [41]

Somalia se encuentra entre los países menos desarrollados del mundo, como lo demuestra su clasificación en métricas como el PIB per cápita , [42] el Índice de Desarrollo Humano , [43] y el Índice de Estados Frágiles . [44] Ha mantenido una economía informal basada principalmente en el ganado, las remesas de los somalíes que trabajan en el extranjero y las telecomunicaciones. [45] Es miembro de las Naciones Unidas , [46] la Liga Árabe , [47] la Unión Africana , [48] el Movimiento de Países No Alineados , [49] la Comunidad de África Oriental , [50] y la Organización de Cooperación Islámica . [51]

Es probable que Somalia fuera una de las primeras tierras en las que se asentaron los primeros seres humanos debido a su ubicación. Los cazadores-recolectores que luego migrarían fuera de África probablemente se establecieron aquí antes de sus migraciones. [52] Durante la Edad de Piedra, las culturas Doian y Hargeisan florecieron aquí. [53] [54] [55] [52] [56] [57] La evidencia más antigua de costumbres funerarias en el Cuerno de África proviene de cementerios en Somalia que datan del cuarto milenio a. C. [58] Los instrumentos de piedra del sitio de Jalelo en el norte también fueron caracterizados en 1909 como artefactos importantes que demuestran la universalidad arqueológica durante el Paleolítico entre Oriente y Occidente. [59]

Según los lingüistas, las primeras poblaciones de habla afroasiática llegaron a la región durante el período Neolítico posterior desde el urheimat ("patria original") propuesto por la familia en el valle del Nilo , [60] o el Cercano Oriente . [61]

El complejo de Laas Geel , en las afueras de Hargeisa, en el noroeste de Somalia, data de hace aproximadamente 5000 años y tiene arte rupestre que representa tanto animales salvajes como vacas decoradas. [62] Otras pinturas rupestres se encuentran en la región norteña de Dhambalin , que presenta una de las representaciones más antiguas conocidas de un cazador a caballo. El arte rupestre data de entre 1000 y 3000 a. C. [63] [64] Además, entre las ciudades de Las Khorey y El Ayo , en el norte de Somalia, se encuentra Karinhegane , el sitio de numerosas pinturas rupestres, que en conjunto se han estimado en alrededor de 2500 años de antigüedad. [65] [66]

Las antiguas estructuras piramidales , los mausoleos , las ciudades en ruinas y los muros de piedra, como el Muro de Wargaade , son evidencia de una antigua civilización que una vez prosperó en la península somalí. [67] [68] Esta civilización disfrutó de una relación comercial con el antiguo Egipto y la Grecia micénica desde el segundo milenio a. C., lo que respalda la hipótesis de que Somalia o las regiones adyacentes eran la ubicación de la antigua Tierra de Punt . [67] [69] Los puntitas nativos de la región comerciaban mirra , especias, oro, ébano, ganado de cuernos cortos, marfil e incienso con los egipcios, fenicios, babilonios, indios, chinos y romanos a través de sus puertos comerciales. Una expedición egipcia enviada a Punt por la reina Hatshepsut de la dinastía XVIII está registrada en los relieves del templo de Deir el-Bahari , durante el reinado del rey puntita Parahu y la reina Ati. [67]

En la era clásica , los macrobianos , que pueden haber sido antepasados de los somalíes, establecieron un poderoso reino que gobernó grandes partes de la actual Somalia. Eran famosos por su longevidad y riqueza, y se decía que eran los "hombres más altos y guapos de todos". [70] Los macrobianos eran pastores guerreros y navegantes. Según el relato de Heródoto, el emperador persa Cambises II , tras su conquista de Egipto en el 525 a. C., envió embajadores a Macrobia, trayendo regalos de lujo para el rey macrobiano para tentar su sumisión. El gobernante macrobiano, que fue elegido en función de su estatura y belleza, respondió en cambio con un desafío a su homólogo persa en forma de un arco sin tensar: si los persas lograban tensarlo, tendrían derecho a invadir su país; pero hasta entonces, debían agradecer a los dioses que los macrobianos nunca decidieran invadir su imperio. [70] [71] Los macrobianos eran una potencia regional famosa por su arquitectura avanzada y su riqueza en oro , que era tan abundante que encadenaban a sus prisioneros con cadenas de oro. [71] Se cree que el camello fue domesticado en la región del Cuerno de África en algún momento entre el segundo y el tercer milenio a. C. Desde allí, se extendió a Egipto y al Magreb . [72]

Durante el período clásico, las ciudades-estado bárbaras de Mosylon , Opone , Mundus , Isis , Malao , Avalites , Essina , Nikon y Sarapion desarrollaron una lucrativa red comercial, conectándose con comerciantes del Egipto ptolemaico , la antigua Grecia , Fenicia , la Persia parta , Saba , el reino nabateo y el Imperio romano . Utilizaban la antigua embarcación marítima somalí conocida como beden para transportar su carga.

Después de la conquista romana del Imperio nabateo y la presencia naval romana en Adén para frenar la piratería, los comerciantes árabes y somalíes acordaron con los romanos prohibir a los barcos indios comerciar en las ciudades portuarias libres de la península arábiga [73] para proteger los intereses de los comerciantes somalíes y árabes en el lucrativo comercio entre los mares Rojo y Mediterráneo. [74] Sin embargo, los comerciantes indios continuaron comerciando en las ciudades portuarias de la península somalí, que estaba libre de la interferencia romana. [75] Durante siglos, los comerciantes indios trajeron grandes cantidades de canela a Somalia y Arabia desde Ceilán y las Islas de las Especias . Se dice que la fuente de la canela y otras especias ha sido el secreto mejor guardado de los comerciantes árabes y somalíes en su comercio con el mundo romano y griego; los romanos y los griegos creían que la fuente había sido la península somalí. [76] El acuerdo colusorio entre comerciantes somalíes y árabes infló el precio de la canela india y china en el norte de África, Oriente Próximo y Europa, e hizo del comercio de la canela un generador de ingresos muy rentable, especialmente para los comerciantes somalíes. [74]

El Islam fue introducido en la zona tempranamente por los primeros musulmanes de La Meca que huyeron de la persecución durante la primera Hégira, con Masjid al-Qiblatayn en Zeila siendo construida antes de la Qiblah hacia La Meca . Es una de las mezquitas más antiguas de África. [77] A finales del siglo IX, Al-Yaqubi escribió que los musulmanes vivían a lo largo de la costa norte de Somalia. [3] También mencionó que el Reino Adal tenía su capital en la ciudad. [3] [78] Según León Africano , el Sultanato Adal estaba gobernado por dinastías somalíes locales y su reino abarcaba el área geográfica entre Bab el Mandeb y Cabo Guardafui. Por lo tanto, estaba flanqueado al sur por el Imperio Ajuran y al oeste por el Imperio Abisinio . [79]

A lo largo de la Edad Media, los inmigrantes árabes llegaron a Somalilandia, una experiencia histórica que más tarde daría lugar a las historias legendarias sobre jeques musulmanes como Daarood e Ishaaq bin Ahmed (los supuestos antepasados de los clanes Darod e Isaaq , respectivamente) que viajaron desde Arabia a Somalia y se casaron con miembros del clan local Dir . [80]

En 1332, el rey de Adal, con base en Zeila, fue asesinado en una campaña militar destinada a detener la marcha del emperador abisinio Amda Seyon I hacia la ciudad. [81] Cuando el último sultán de Ifat, Sa'ad ad-Din II , también fue asesinado por el emperador Dawit I en Zeila en 1410, sus hijos escaparon a Yemen, antes de regresar en 1415. [82] A principios del siglo XV, la capital de Adal se trasladó más al interior, a la ciudad de Dakkar , donde Sabr ad-Din II , el hijo mayor de Sa'ad ad-Din II, estableció una nueva base después de su regreso de Yemen. [83] [84]

El cuartel general de Adal fue trasladado nuevamente al siglo siguiente, esta vez al sur, a Harar . Desde esta nueva capital, Adal organizó un ejército eficaz dirigido por el imán Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmad "Gurey" o "Gran"; ambos significan "el zurdo") y su general más cercano, Garad Hirabu "Emir de los somalíes" , que invadió el imperio abisinio. [84] Esta campaña del siglo XVI se conoce históricamente como la conquista de Abisinia ( Futuh al-Habash ). Durante la guerra, el imán Ahmad fue pionero en el uso de cañones suministrados por el Imperio otomano, que importó a través de Zeila y desplegó contra las fuerzas abisinias y sus aliados portugueses liderados por Cristóvão da Gama . [85]

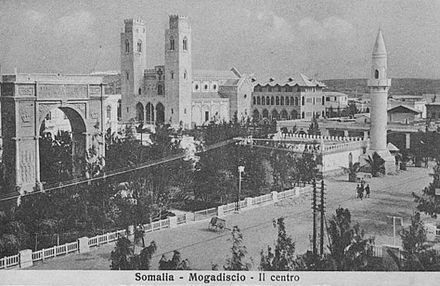

Durante el período del Sultanato de Ajuran , las ciudades-estado y repúblicas de Merca , Mogadiscio , Barawa , Hobyo y sus respectivos puertos florecieron y tuvieron un lucrativo comercio exterior con barcos que navegaban hacia y desde Arabia, India, Venecia , [86] Persia, Egipto, Portugal y lugares tan lejanos como China. Vasco da Gama , que pasó por Mogadiscio en el siglo XV, señaló que era una ciudad grande con casas de varios pisos de altura y grandes palacios en su centro, además de muchas mezquitas con minaretes cilíndricos. [87] Los Harla , un grupo camítico temprano de alta estatura que habitó partes de Somalia, Tchertcher y otras áreas en el Cuerno de África, también erigieron varios túmulos . [88] Se cree que estos albañiles fueron antepasados de los somalíes étnicos. [89]

En el siglo XVI, Duarte Barbosa señaló que muchos barcos del Reino de Cambaya en la actual India navegaban hacia Mogadiscio con telas y especias, por lo que recibían a cambio oro, cera y marfil. Barbosa también destacó la abundancia de carne, trigo, cebada, caballos y frutas en los mercados costeros, lo que generaba una enorme riqueza para los comerciantes. [90] Mogadiscio, el centro de una próspera industria textil conocida como toob benadir (especializada para los mercados de Egipto, entre otros lugares [91] ), junto con Merca y Barawa, también sirvió como parada de tránsito para los comerciantes swahili de Mombasa y Malindi y para el comercio de oro de Kilwa . [92] Los comerciantes judíos de Ormuz llevaban sus textiles y frutas indias a la costa somalí a cambio de grano y madera. [93]

Las relaciones comerciales se establecieron con Malaca en el siglo XV, [94] siendo las telas, el ámbar gris y la porcelana los principales productos del comercio. [95] Se exportaron jirafas, cebras e incienso al Imperio Ming de China, que estableció a los comerciantes somalíes como líderes en el comercio entre el este de Asia y el Cuerno de África. [96] Los comerciantes hindúes de Surat y los comerciantes del sudeste africano de Pate , tratando de eludir tanto el bloqueo portugués de la India (y más tarde la interferencia omaní), utilizaron los puertos somalíes de Merca y Barawa (que estaban fuera de la jurisdicción directa de las dos potencias) para realizar su comercio con seguridad y sin interferencias. [97]

A principios del período moderno , comenzaron a florecer en Somalia los estados sucesores del sultanato de Adal y el sultanato de Ajuran , entre ellos el Imamato de Hiraab , el sultanato de Isaaq dirigido por la dinastía Guled , [98] [99] el sultanato de Habr Yunis dirigido por la dinastía Ainanshe , [24] el sultanato de Geledi (dinastía Gobroon), el sultanato de Majeerteen (Migiurtinia) y el sultanato de Hobyo (Obbia). Continuaron la tradición de construcción de castillos y comercio marítimo establecida por los imperios somalíes anteriores.

El sultán Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim , tercer sultán de la Casa de Gobroon, inició la edad de oro de la dinastía Gobroon. Su ejército salió victorioso durante la Jihad Bardheere, que restauró la estabilidad en la región y revitalizó el comercio de marfil de África Oriental . También mantuvo relaciones cordiales y recibió regalos de los gobernantes de reinos vecinos y lejanos como los sultanes de Omán, Witu y Yemen.

El hijo del sultán Ibrahim, Ahmed Yusuf, lo sucedió como una de las figuras más importantes del África oriental del siglo XIX, recibiendo tributos de los gobernadores omaníes y creando alianzas con importantes familias musulmanas de la costa oriental de África.

En Somalilandia , el Sultanato Isaaq se estableció en 1750. El Sultanato Isaaq fue un reino somalí que gobernó partes del Cuerno de África durante los siglos XVIII y XIX. [98] Se extendió por los territorios del clan Isaaq , descendientes del clan Banu Hashim , [100] en la actual Somalilandia y Etiopía . El sultanato fue gobernado por la rama Rer Guled establecida por el primer sultán, el sultán Guled Abdi , del clan Eidagale . [101] [102] [103] Según la tradición oral, antes de la dinastía Guled, la familia del clan Isaaq estaba gobernada por una dinastía de la rama Tolje'lo a partir de, descendientes de Ahmed apodado Tol Je'lo, el hijo mayor de la esposa Harari del jeque Ishaaq . Hubo ocho gobernantes Tolje'lo en total, comenzando con Boqor Harun ( somalí : Boqor Haaruun ) que gobernó el Sultanato Isaaq durante siglos a partir del siglo XIII. [104] [105] El último gobernante Tolje'lo, Garad Dhuh Barar ( somalí : Dhuux Baraar ), fue derrocado por una coalición de clanes Isaaq. El otrora fuerte clan Tolje'lo se dispersó y se refugió entre los Habr Awal con quienes aún viven en su mayoría. [106] [107]

A finales del siglo XIX, tras la Conferencia de Berlín de 1884, las potencias europeas iniciaron la lucha por África . Ese año, se declaró un protectorado británico sobre parte de Somalia, en la costa africana frente a Yemen del Sur. [108] Inicialmente, esta región estaba bajo el control de la Oficina de la India, y por lo tanto administrada como parte del Imperio indio; en 1898 pasó a manos de Londres. [108] En 1889, el protectorado y más tarde la colonia de la Somalia italiana fue establecida oficialmente por Italia a través de varios tratados firmados con varios jefes y sultanes; [109] El sultán Yusuf Ali Kenadid envió por primera vez una solicitud a Italia a finales de diciembre de 1888 para convertir su sultanato de Hobyo en un protectorado italiano antes de firmar un tratado más tarde en 1889. [110]

El movimiento derviche rechazó con éxito al Imperio británico cuatro veces y lo obligó a retirarse a la región costera. [111] Los darawiish derrotaron a las potencias coloniales italiana, británica y abisinia en numerosas ocasiones, en particular, la victoria de 1903 en Cagaarweyne comandada por Suleiman Aden Galaydh , [112] obligando al Imperio británico a retirarse a la región costera a principios de la década de 1900. [113] Los derviches fueron finalmente derrotados en 1920 por el poder aéreo británico. [114]

El amanecer del fascismo a principios de la década de 1920 anunció un cambio de estrategia para Italia, ya que los sultanatos del noreste pronto se verían obligados a quedar dentro de los límites de La Grande Somalia (" Gran Somalia ") según el plan de la Italia fascista. Con la llegada del gobernador Cesare Maria De Vecchi el 15 de diciembre de 1923, las cosas comenzaron a cambiar para esa parte de Somalilandia conocida como Somalilandia italiana . El último trozo de tierra adquirido por Italia en Somalia fue Oltre Giuba , la actual región de Jubaland , en 1925. [110]

Los italianos comenzaron proyectos de infraestructura local, incluyendo la construcción de hospitales, granjas y escuelas. [115] La Italia fascista , bajo Benito Mussolini , atacó Abisinia (Etiopía) en 1935, con el objetivo de colonizarla. La invasión fue condenada por la Liga de las Naciones , pero poco se hizo para detenerla o para liberar la Etiopía ocupada. En 1936, la Somalia italiana se integró en el África Oriental Italiana , junto con Eritrea y Etiopía, como la Gobernación de Somalia . El 3 de agosto de 1940, las tropas italianas, incluidas las unidades coloniales somalíes, cruzaron desde Etiopía para invadir la Somalia británica , y el 14 de agosto, lograron tomar Berbera de los británicos. [ cita requerida ]

En enero de 1941 , una fuerza británica, que incluía tropas de varios países africanos, lanzó la campaña desde Kenia para liberar la Somalia británica y la Etiopía ocupada por Italia y conquistar la Somalia italiana. En febrero, la mayor parte de la Somalia italiana había sido capturada y, en marzo, la Somalia británica fue recuperada del mar. Las fuerzas del Imperio británico que operaban en Somalilandia comprendían las tres divisiones de tropas sudafricanas, africanas occidentales y africanas orientales. Contaban con la asistencia de fuerzas somalíes lideradas por Abdulahi Hassan, con la participación destacada de somalíes de los clanes Isaaq , Dhulbahante y Warsangali . El número de somalíes italianos comenzó a disminuir después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, y en 1960 quedaban menos de 10 000. [116]

Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Gran Bretaña mantuvo el control de la Somalilandia británica y la Somalilandia italiana como protectorados. En 1945, durante la Conferencia de Potsdam , las Naciones Unidas otorgaron a Italia la tutela de la Somalilandia italiana como Territorio en Fideicomiso de Somalilandia , con la condición propuesta por primera vez por la Liga de la Juventud Somalí (SYL) y otras organizaciones políticas somalíes nacientes, como Hizbia Digil Mirifle Somali (HDMS) y la Liga Nacional Somalí (SNL), de que Somalia lograra la independencia en un plazo de diez años. [117] [118] La Somalilandia británica siguió siendo un protectorado de Gran Bretaña hasta 1960. [116]

En la medida en que Italia poseía el territorio por mandato de las Naciones Unidas, las disposiciones de tutela dieron a los somalíes la oportunidad de adquirir experiencia en la educación política y el autogobierno occidentales. Se trataba de ventajas que la Somalia británica, que iba a ser incorporada al nuevo Estado somalí, no tenía. Aunque en la década de 1950 los funcionarios coloniales británicos intentaron, mediante diversas iniciativas de desarrollo administrativo, compensar la negligencia anterior, el protectorado se estancó en el desarrollo político administrativo. La disparidad entre los dos territorios en materia de desarrollo económico y experiencia política causaría posteriormente serias dificultades para la integración de las dos partes. [119]

Mientras tanto, en 1948, bajo la presión de sus aliados de la Segunda Guerra Mundial y para consternación de los somalíes, [120] los británicos devolvieron Haud (una importante zona de pastoreo somalí que presumiblemente estaba protegida por los tratados británicos con los somalíes en 1884 y 1886) y la región somalí a Etiopía, con base en un tratado que firmaron en 1897 en el que los británicos cedieron territorio somalí al emperador etíope Menelik a cambio de su ayuda contra posibles avances de los franceses. [121]

Gran Bretaña incluyó la cláusula condicional de que los residentes somalíes conservarían su autonomía, pero Etiopía inmediatamente reclamó la soberanía sobre la zona. Esto provocó un intento fallido de Gran Bretaña en 1956 de recomprar las tierras somalíes que había entregado. [117] Gran Bretaña también concedió la administración del Distrito Fronterizo Norte (NFD), habitado casi exclusivamente por somalíes, a los nacionalistas kenianos. [122] [123] Esto se produjo a pesar de un plebiscito en el que, según una comisión colonial británica, casi todos los somalíes étnicos del territorio estaban a favor de unirse a la recién formada República Somalí. [124]

En 1958, en vísperas de la independencia de Somalia en 1960, se celebró un referéndum en el vecino Yibuti (entonces conocido como Somalia Francesa ) para decidir si Somalia se unía a la República de Somalia o permanecía con Francia. El referéndum resultó a favor de una asociación continua con Francia, en gran medida debido al voto afirmativo combinado del considerable grupo étnico afar y de los europeos residentes. [125] También hubo un fraude electoral generalizado, ya que los franceses expulsaron a miles de somalíes antes de que el referéndum llegara a las urnas. [126]

La mayoría de los que votaron "no" eran somalíes que estaban firmemente a favor de unirse a una Somalia unida, como había propuesto Mahmoud Harbi , vicepresidente del Consejo de Gobierno. Harbi murió en un accidente aéreo dos años después. [125] Yibuti finalmente obtuvo la independencia de Francia en 1977, y Hassan Gouled Aptidon , un somalí que había hecho campaña por el "sí" en el referéndum de 1976, finalmente se convirtió en el primer presidente de Yibuti (1977-1999). [125]

El 1 de julio de 1960, cinco días después de que el antiguo protectorado británico de Somalilandia obtuviera la independencia como Estado de Somalilandia, el territorio se unió al Territorio en Fideicomiso de Somalilandia para formar la República Somalí , [127] aunque dentro de los límites establecidos por Italia y Gran Bretaña. [128] [129] Abdullahi Issa y Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal formaron un gobierno con otros miembros de los gobiernos de tutela y protectorado, con Abdulcadir Muhammed Aden como Presidente de la Asamblea Nacional Somalí , Aden Abdullah Osman Daar como Presidente de la República Somalí y Abdirashid Ali Shermarke como Primer Ministro (que más tarde se convertiría en presidente de 1967 a 1969). El 20 de julio de 1961 y a través de un referéndum popular , fue ratificada popularmente por el pueblo de Somalia bajo tutela italiana. La mayoría de la gente del antiguo Protectorado de Somalilandia no participó en el referéndum, aunque solo un pequeño número de somalilandeses que participaron en el referéndum votaron en contra de la nueva constitución , [130] que se redactó por primera vez en 1960. [29] En 1967, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal se convirtió en Primer Ministro, cargo para el que fue designado por Shermarke. Egal más tarde se convertiría en el Presidente de la región autónoma de Somalilandia en el noroeste de Somalia.

El 15 de octubre de 1969, mientras visitaba la ciudad norteña de Las Anod , el entonces presidente de Somalia, Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, fue asesinado a tiros por uno de sus propios guardaespaldas. Su asesinato fue rápidamente seguido por un golpe de estado militar el 21 de octubre de 1969, en el que el ejército somalí tomó el poder sin encontrar oposición armada, esencialmente una toma de poder sin derramamiento de sangre. El golpe fue encabezado por el mayor general Mohamed Siad Barre , que en ese momento comandaba el ejército. [131]

Junto a Barre, el Consejo Supremo Revolucionario (SRC) que asumió el poder tras el asesinato del presidente Sharmarke estaba dirigido por el general de brigada Mohamed Ainanshe Guled , el teniente coronel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye y el jefe de policía Jama Korshel . Kediye ostentaba oficialmente el título de "Padre de la Revolución", y Barre poco después se convirtió en el jefe del SRC. [132] Posteriormente, el SRC rebautizó al país como República Democrática Somalí, [133] [134] disolvió el parlamento y la Corte Suprema y suspendió la constitución. [135]

El ejército revolucionario puso en marcha programas de obras públicas a gran escala e implementó con éxito una campaña de alfabetización urbana y rural , que ayudó a aumentar drásticamente la tasa de alfabetización. Además de un programa de nacionalización de la industria y la tierra, la política exterior del nuevo régimen hizo hincapié en los vínculos tradicionales y religiosos de Somalia con el mundo árabe , y finalmente se unió a la Liga Árabe en febrero de 1974. [136] Ese mismo año, Barre también se desempeñó como presidente de la Organización de la Unidad Africana (OUA), predecesora de la Unión Africana (UA). [137]

En julio de 1976, el SRC de Barre se disolvió y estableció en su lugar el Partido Socialista Revolucionario Somalí (SRSP), un gobierno de partido único basado en el socialismo científico y los principios islámicos. El SRSP fue un intento de reconciliar la ideología oficial del estado con la religión oficial del estado adaptando los preceptos marxistas a las circunstancias locales. Se hizo hincapié en los principios musulmanes de progreso social, igualdad y justicia, que el gobierno argumentó que formaban el núcleo del socialismo científico y su propio acento en la autosuficiencia, la participación pública y el control popular, así como la propiedad directa de los medios de producción. Si bien el SRSP alentó la inversión privada en una escala limitada, la dirección general de la administración fue esencialmente comunista . [135]

En julio de 1977, estalló la Guerra de Ogadén después de que el gobierno de Barre utilizara un alegato de unidad nacional para justificar una incorporación agresiva de la región de Ogadén de Etiopía, habitada predominantemente por somalíes , a una Gran Somalia pansomalí , junto con las ricas tierras agrícolas del sureste de Etiopía, infraestructura y áreas estratégicamente importantes hasta el norte de Yibuti. [138] En la primera semana del conflicto, las fuerzas armadas somalíes tomaron el sur y el centro de Ogadén y durante la mayor parte de la guerra, el ejército somalí obtuvo victorias continuas sobre el ejército etíope y los siguió hasta Sidamo . En septiembre de 1977, Somalia controlaba el 90% de Ogadén y capturó ciudades estratégicas como Jijiga y ejerció una fuerte presión sobre Dire Dawa , amenazando la ruta del tren desde esta última ciudad a Yibuti. Después del asedio de Harar, una intervención soviética masiva sin precedentes, compuesta por 20.000 soldados cubanos y varios miles de expertos soviéticos, acudió en ayuda del régimen comunista etíope del Derg . En 1978, las tropas somalíes fueron finalmente expulsadas de Ogadén. Este cambio en el apoyo de la Unión Soviética motivó al gobierno de Barre a buscar aliados en otros lugares. Finalmente, se decidió por el archirrival de los soviéticos en la Guerra Fría , Estados Unidos , que había estado cortejando al gobierno somalí durante algún tiempo. La amistad inicial de Somalia con la Unión Soviética y la posterior asociación con Estados Unidos le permitieron construir el ejército más grande de África. [139]

En 1979 se promulgó una nueva constitución en virtud de la cual se celebraron elecciones para una Asamblea Popular. Sin embargo, el politburó del Partido Socialista Revolucionario Somalí de Barre siguió gobernando. [134] En octubre de 1980, el SRSP se disolvió y se restableció el Consejo Revolucionario Supremo en su lugar. [135] Para entonces, el gobierno de Barre se había vuelto cada vez más impopular. Muchos somalíes se habían desilusionado con la vida bajo la dictadura militar.

El régimen se debilitó aún más en la década de 1980, cuando la Guerra Fría se acercaba a su fin y la importancia estratégica de Somalia disminuyó. El gobierno se volvió cada vez más autoritario y los movimientos de resistencia , alentados por Etiopía, surgieron en todo el país, lo que finalmente llevó a la Guerra Civil Somalí . Entre los grupos de milicias se encontraban el Frente Democrático de Salvación Somalí (SSDF), el Congreso Somalí Unido (USC), el Movimiento Nacional Somalí (SNM) y el Movimiento Patriótico Somalí (SPM), junto con las oposiciones políticas no violentas del Movimiento Democrático Somalí (SDM), la Alianza Democrática Somalí (SDA) y el Grupo del Manifiesto Somalí (SMG).

A medida que la autoridad moral del gobierno de Barre se fue erosionando gradualmente, muchos somalíes se desilusionaron con la vida bajo el régimen militar. A mediados de la década de 1980, los movimientos de resistencia apoyados por la administración comunista etíope del Derg habían surgido en todo el país. Barre respondió ordenando medidas punitivas contra quienes percibía que apoyaban localmente a las guerrillas, especialmente en las regiones del norte. La represión incluyó el bombardeo de ciudades, entre las que se encontraba el centro administrativo noroccidental de Hargeisa , un bastión del Movimiento Nacional Somalí (SNM), entre las zonas atacadas en 1988. [141] [142]

La represión iniciada por el gobierno de Barre se extendió más allá de los bombardeos iniciales en el norte y abarcó varias regiones del país. Esta reproducción de estrategias agresivas destinadas a sofocar la descendencia y retener la autoridad sobre la población fue un sello distintivo de las acciones represivas del gobierno en el sur. Uno de los casos más notables ocurrió en 1991, cuando el régimen de Barre inició un despiadado asalto aéreo que provocó la muerte de numerosas personas inocentes en la ciudad de Beledwene , situada en el sur de Somalia. [143] La crueldad y la magnitud de esta atrocidad pusieron de relieve hasta qué punto estaba dispuesto a llegar el gobierno para aplastar cualquier tipo de oposición o resistencia, mostrando un flagrante desprecio por los derechos humanos y el valor de la vida humana. [144]

Otro ejemplo notable de las políticas represivas de Barre ocurrió en la ciudad de Baidoa , que se ganó el apodo de "la ciudad de la muerte" debido a los trágicos acontecimientos que se desarrollaron allí durante la hambruna y la guerra civil . [145] Vale la pena señalar que cientos de miles de personas perdieron la vida como consecuencia de las estrategias gubernamentales dirigidas específicamente a la comunidad Rahanweyn que reside en estas áreas. [146]

En 1990, en la capital, Mogadiscio, se prohibió a los residentes reunirse en público en grupos de más de tres o cuatro personas. La escasez de combustible, la inflación y la devaluación de la moneda afectaron a la economía. En el centro de la ciudad existía un floreciente mercado negro, ya que los bancos sufrían escasez de moneda local para el cambio. Se introdujeron severas normas de control de cambio para impedir la exportación de divisas. Aunque no se impusieron restricciones de viaje a los extranjeros, se prohibió fotografiar muchos lugares. Durante el día, en Mogadiscio, la aparición de fuerzas militares gubernamentales era extremadamente rara. Sin embargo, las supuestas operaciones nocturnas de las autoridades gubernamentales incluían "desapariciones" de personas de sus hogares. [147]

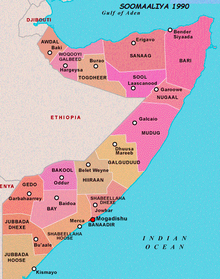

En 1991, la administración de Barre fue derrocada por una coalición de grupos de oposición basados en clanes, respaldados por el régimen de Derg que entonces gobernaba Etiopía y Libia . [148] Después de una reunión del Movimiento Nacional Somalí y los ancianos de los clanes del norte, la antigua parte británica del norte del país declaró su independencia como la República de Somalilandia en mayo de 1991. Aunque de facto es independiente y relativamente estable en comparación con el tumultuoso sur, no ha sido reconocida por ningún gobierno extranjero. [149] [150]

Muchos de los grupos de oposición comenzaron posteriormente a competir por la influencia en el vacío de poder que siguió al derrocamiento del régimen de Barre. En el sur, las facciones armadas lideradas por los comandantes de la USC, el general Mohamed Farah Aidid y Ali Mahdi Mohamed , en particular, se enfrentaron mientras cada uno buscaba ejercer autoridad sobre la capital. [152] En 1991, se celebró una conferencia internacional de varias fases sobre Somalia en el vecino Yibuti [153] Debido a la legitimidad otorgada a Muhammad por la conferencia de Yibuti, posteriormente fue reconocido por la comunidad internacional como el nuevo Presidente de Somalia. [153] No pudo ejercer su autoridad más allá de partes de la capital. En cambio, el poder se disputó con otros líderes de facciones en la mitad sur de Somalia y con entidades subnacionales autónomas en el norte. [154] La Conferencia de Djibouti fue seguida por dos acuerdos fallidos de reconciliación nacional y desarme, que fueron firmados por 15 actores políticos: un acuerdo para celebrar una Reunión Preparatoria Informal sobre Reconciliación Nacional y el Acuerdo de Addis Abeba de 1993, alcanzado en la Conferencia de Reconciliación Nacional. [ cita requerida ]

A principios de la década de 1990, debido a la prolongada falta de una autoridad central permanente, Somalia empezó a ser caracterizada como un " Estado fallido ". [155] [156] [157]

.jpg/440px-Abdullahi_Yusuf_Ahmed_(28-03-2006).jpg)

El Gobierno Nacional de Transición (GNT) se estableció en abril-mayo de 2000 en la Conferencia Nacional de Paz de Somalia (SNPC) celebrada en Arta, Yibuti. Abdiqasim Salad Hassan fue elegido presidente del nuevo Gobierno Nacional de Transición (GNT), una administración provisional formada para guiar a Somalia hacia su tercer gobierno republicano permanente. [158] Los problemas internos del GNT llevaron a la sustitución del Primer Ministro cuatro veces en tres años, y a la quiebra declarada del órgano administrativo en diciembre de 2003. Su mandato terminó al mismo tiempo. [159]

El 10 de octubre de 2004, los legisladores eligieron a Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed como el primer Presidente del Gobierno Federal de Transición (GFT), sucesor del Gobierno Nacional de Transición. [160] El GFT fue la segunda administración interina cuyo objetivo era restaurar las instituciones nacionales en Somalia después del colapso en 1991 del régimen de Siad Barre y la consiguiente guerra civil. [161]

El Gobierno Federal de Transición (GFT) fue el gobierno internacionalmente reconocido de Somalia hasta el 20 de agosto de 2012, cuando su mandato terminó oficialmente. [40] Fue establecido como una de las Instituciones Federales de Transición (IFT) de gobierno según se define en la Carta Federal de Transición (CFT) adoptada en noviembre de 2004 por el Parlamento Federal de Transición (PFT). El Gobierno Federal de Transición comprendía oficialmente el poder ejecutivo del gobierno, y el PFT actuaba como poder legislativo . El gobierno estaba encabezado por el Presidente de Somalia , a quien el gabinete reportaba a través del Primer Ministro . Sin embargo, también se utilizó como un término general para referirse a los tres poderes colectivamente. [ cita requerida ]

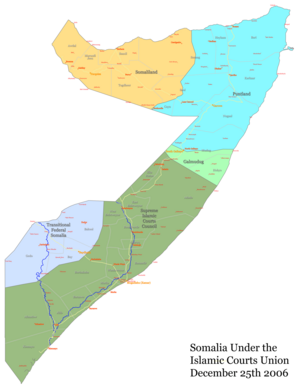

En 2006, la Unión de Tribunales Islámicos (UTI) asumió el control de gran parte de la zona sur del país durante seis meses e impuso la ley sharia . Altos funcionarios de la ONU se han referido a este breve período como una "época dorada" en la historia de la política somalí. [162] [163]

El Gobierno Federal de Transición trató de restablecer su autoridad y, con la ayuda de tropas etíopes , fuerzas de paz de la Unión Africana y apoyo aéreo de los Estados Unidos, expulsó a la UTI y consolidó su gobierno. [164] El 8 de enero de 2007, el Presidente del GFT, Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed, entró en Mogadiscio con el apoyo militar etíope por primera vez desde que fue elegido para el cargo. El gobierno se trasladó entonces a Villa Somalia en la capital desde su ubicación provisional en Baidoa . Esto marcó la primera vez desde la caída del régimen de Siad Barre en 1991 que el gobierno federal controlaba la mayor parte del país. [165]

Al-Shabaab se opuso a la presencia militar etíope en Somalia y continuó la insurgencia contra el Gobierno Federal de Transición. A lo largo de 2007 y 2008, Al-Shabaab obtuvo victorias militares, tomando el control de ciudades y puertos clave tanto en el centro como en el sur de Somalia. En enero de 2009, Al-Shabaab y otras milicias habían obligado a las tropas etíopes a retirarse, dejando atrás una fuerza de mantenimiento de la paz de la Unión Africana mal equipada para ayudar a las tropas del Gobierno Federal de Transición. [166]

Debido a la falta de financiación y recursos humanos, un embargo de armas que dificultaba el restablecimiento de una fuerza de seguridad nacional y la indiferencia general de la comunidad internacional, Yusuf se vio obligado a desplegar miles de tropas de Puntlandia a Mogadiscio para sostener la batalla contra los elementos insurgentes en la parte sur del país. El apoyo financiero para esta iniciativa lo proporcionó el gobierno de la región autónoma, lo que dejó pocos ingresos para las propias fuerzas de seguridad de Puntlandia y los empleados públicos, lo que dejó al territorio vulnerable a la piratería y los ataques terroristas. [167] [168]

El 29 de diciembre de 2008, Yusuf anunció ante un parlamento unido en Baidoa su dimisión como Presidente de Somalia. En su discurso, que fue transmitido por la radio nacional, Yusuf expresó su pesar por no haber logrado poner fin al conflicto que había asolado el país durante diecisiete años, como se le había encomendado a su gobierno. [169] También culpó a la comunidad internacional por no haber apoyado al gobierno y dijo que el presidente del parlamento lo sucedería en el cargo de conformidad con la Carta del Gobierno Federal de Transición . [170]

Entre el 31 de mayo y el 9 de junio de 2008, representantes del gobierno federal de Somalia y de la Alianza para la Reliberación de Somalia (ARS) participaron en conversaciones de paz en Yibuti, con la mediación del ex enviado especial de las Naciones Unidas a Somalia, Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah . La conferencia concluyó con la firma de un acuerdo que exigía la retirada de las tropas etíopes a cambio del cese de la confrontación armada. Posteriormente, el Parlamento se amplió a 550 escaños para dar cabida a los miembros de la ARS, que luego eligió al jeque Sharif Sheikh Ahmed como presidente. [1]

Con la ayuda de un pequeño equipo de tropas de la Unión Africana, el GFT inició una contraofensiva en febrero de 2009 para asumir el control total de la mitad sur del país. Para consolidar su gobierno, el GFT formó una alianza con la Unión de Tribunales Islámicos, otros miembros de la Alianza para la Reliberación de Somalia y Ahlu Sunna Waljama'a , una milicia sufí moderada. [171] Además, Al-Shabaab y Hizbul Islam, los dos principales grupos islamistas en la oposición, comenzaron a luchar entre sí a mediados de 2009. [172] Como tregua, en marzo de 2009, el GFT anunció que volvería a implementar la sharia como sistema judicial oficial de la nación. [173] Sin embargo, el conflicto continuó en las partes sur y central del país. En cuestión de meses, el GFT había pasado de controlar alrededor del 70% de las zonas de conflicto del centro-sur de Somalia a perder el control de más del 80% del territorio en disputa ante los insurgentes islamistas. [165]

En octubre de 2011, comenzó una operación coordinada, la Operación Linda Nchi , entre los ejércitos somalíes y kenianos y fuerzas multinacionales contra Al-Shabaab en el sur de Somalia. [174] [175] Para septiembre de 2012, las fuerzas somalíes, kenianas y raskamboni habían logrado capturar el último bastión importante de Al-Shabaab, el puerto sureño de Kismayo. [176] En julio de 2012, se lanzaron tres operaciones de la Unión Europea para colaborar con Somalia: EUTM Somalia , la Operación Atalanta de la Fuerza Naval de la UE en Somalia frente al Cuerno de África y la EUCAP Nestor. [177]

Como parte de la "Hoja de ruta para el fin de la transición" oficial, un proceso político que proporcionó puntos de referencia claros que conducían a la formación de instituciones democráticas permanentes en Somalia, el mandato provisional del Gobierno Federal de Transición finalizó el 20 de agosto de 2012. [33] Al mismo tiempo se inauguró el Parlamento Federal de Somalia . [40]

El Gobierno Federal de Somalia , el primer gobierno central permanente del país desde el inicio de la guerra civil, se estableció en agosto de 2012. En agosto de 2014, se lanzó la Operación Océano Índico dirigida por el gobierno somalí contra los focos controlados por los insurgentes en el campo. [178]

Somalia limita al oeste con Etiopía , al norte con el golfo de Adén , al este con el mar de Somalia y el canal de Guardafui , y al suroeste con Kenia . Con una superficie de 637.657 kilómetros cuadrados, el terreno de Somalia se compone principalmente de mesetas , llanuras y tierras altas . [179] Su costa tiene más de 3.333 kilómetros de longitud, la más larga de África continental. [180] Se ha descrito como si tuviera una forma aproximada "como la de un número siete inclinado". [181]

En el extremo norte, las escarpadas cadenas montañosas de este a oeste de Ogo se encuentran a diferentes distancias de la costa del Golfo de Adén. Las condiciones cálidas prevalecen durante todo el año, junto con vientos monzónicos periódicos y lluvias irregulares. [182] La geología sugiere la presencia de valiosos depósitos minerales. Somalia está separada de Seychelles por el mar de Somalia y está separada de Socotra por el canal de Guardafui .

Somalia está dividida oficialmente en dieciocho regiones ( gobollada , singular gobol ), [1] que a su vez se subdividen en distritos. Las regiones son:

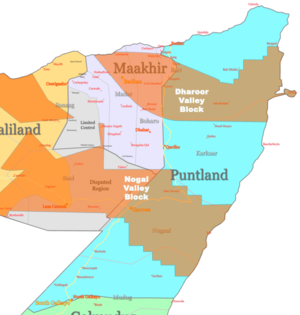

El norte de Somalia está dividido de facto entre las regiones autónomas de Puntlandia (que se considera un estado autónomo ), Somalilandia (un estado autodeclarado pero no reconocido ) y el recién creado estado de Khatumo en Somalia . En el centro de Somalia, Galmudug es otra entidad regional que surgió justo al sur de Puntlandia. Jubalandia , en el extremo sur, es una cuarta región autónoma dentro de la federación. [1] En 2014, también se estableció un nuevo estado del suroeste . [185] En abril de 2015, también se lanzó una conferencia de formación para un nuevo estado de Hirshabelle . [186]

El Parlamento Federal tiene la tarea de seleccionar el número definitivo y los límites de los estados regionales autónomos (oficialmente Estados miembros federales ) dentro de la República Federal de Somalia. [187] [188]

Somalia limita al suroeste con Kenia, al norte con el golfo de Adén , al este con el canal de Guardafui y el océano Índico, y al oeste con Etiopía. El país limita con Yibuti . Se encuentra entre las latitudes 2°S y 12°N , y las longitudes 41° y 52°E . Estratégicamente situado en la desembocadura de la puerta de Bab el Mandeb al mar Rojo y al canal de Suez , el país ocupa la punta de una región que, debido a su parecido en el mapa con el cuerno de un rinoceronte , se conoce comúnmente como el Cuerno de África. [1] [189]

Somalia tiene la línea costera más larga del continente africano, [190] con un litoral que se extiende a lo largo de 3.333 kilómetros (2.071 millas). Su terreno se compone principalmente de mesetas , llanuras y tierras altas . La nación tiene una superficie total de 637.657 kilómetros cuadrados (246.201 millas cuadradas) de los cuales constituyen tierra, con 10.320 kilómetros cuadrados (3.980 millas cuadradas) de agua. Los límites terrestres de Somalia se extienden a unos 2.340 kilómetros (1.450 millas); 58 kilómetros (36 millas) de los cuales se comparten con Yibuti, 682 kilómetros (424 millas) con Kenia y 1.626 kilómetros (1.010 millas) con Etiopía. Sus reclamaciones marítimas incluyen aguas territoriales de 200 millas náuticas (370 km; 230 millas). [1]

Somalia tiene varias islas y archipiélagos en su costa, incluidas las islas Bajuni y el archipiélago Saad ad-Din : ver islas de Somalia .

Somalia contiene siete ecorregiones terrestres: bosques montañosos de Etiopía , mosaico forestal costero del norte de Zanzíbar-Inhambane , matorrales y matorrales de acacia y commiphora de Somalia , pastizales y matorrales xéricos de Etiopía , pastizales y matorrales de hobyo , bosques xéricos montañosos de Somalia y manglares de África oriental . [191]

En el norte, una llanura semidesértica cubierta de matorrales conocida como Guban se extiende paralela al litoral del Golfo de Adén . Con una anchura de doce kilómetros en el oeste y tan solo dos kilómetros en el este, la llanura está atravesada por cursos de agua que son esencialmente lechos de arena seca, excepto durante las estaciones lluviosas. Cuando llegan las lluvias, los arbustos bajos y las matas de hierba de Guban se transforman en una vegetación exuberante. [189] Esta franja costera forma parte de la ecorregión de pastizales y matorrales xerófilos de Etiopía .

Cal Madow es una cadena montañosa en la parte noreste del país. Se extiende desde varios kilómetros al oeste de la ciudad de Bosaso hasta el noroeste de Erigavo , y cuenta con el pico más alto de Somalia , Shimbiris , que se encuentra a una altitud de unos 2416 metros (7927 pies). [1] Las escarpadas cordilleras de este a oeste de las montañas Karkaar también se encuentran en el interior del litoral del Golfo de Adén. [189] En las regiones centrales, las cadenas montañosas del norte del país dan paso a mesetas poco profundas y cursos de agua típicamente secos que se conocen localmente como Ogo . La meseta occidental de Ogo, a su vez, se fusiona gradualmente con Haud , una importante zona de pastoreo para el ganado. [189]

Somalia tiene sólo dos ríos permanentes, el Jubba y el Shabele , ambos con origen en las tierras altas de Etiopía . Estos ríos fluyen principalmente hacia el sur, y el río Jubba desemboca en el océano Índico en Kismayo . El río Shabele, al parecer, solía desembocar en el mar cerca de Merca , pero ahora llega a un punto justo al suroeste de Mogadiscio. Después de eso, se compone de pantanos y tramos secos antes de desaparecer finalmente en el terreno desértico al este de Jilib , cerca del río Jubba. [189]

Somalia es un país semiárido con alrededor del 1,64% de tierra cultivable . [1] Las primeras organizaciones ambientales locales fueron Ecoterra Somalia y la Sociedad Ecológica Somalí, las cuales ayudaron a promover la conciencia sobre las preocupaciones ecológicas y movilizaron programas ambientales en todos los sectores gubernamentales, así como en la sociedad civil. A partir de 1971, el gobierno de Siad Barre introdujo una campaña masiva de plantación de árboles a escala nacional para detener el avance de miles de acres de dunas de arena impulsadas por el viento que amenazaban con engullir ciudades, carreteras y tierras de cultivo. [192] Para 1988, se habían tratado 265 hectáreas de las 336 hectáreas proyectadas, con 39 sitios de reserva de pastizales y 36 sitios de plantación forestal establecidos. [189] En 1986, Ecoterra International estableció el Centro de Rescate, Investigación y Monitoreo de Vida Silvestre, con el objetivo de sensibilizar al público sobre cuestiones ecológicas. Este esfuerzo educativo condujo en 1989 a la llamada "propuesta de Somalia" y a la decisión del gobierno somalí de adherirse a la Convención sobre el Comercio Internacional de Especies Amenazadas de Fauna y Flora Silvestres (CITES), que estableció por primera vez una prohibición mundial del comercio de marfil de elefante .

.jpg/440px-Aerial_views_of_Kismayo_06_(8071381265).jpg)

Más tarde, Fatima Jibrell , una destacada activista medioambiental somalí, organizó una exitosa campaña para conservar los bosques antiguos de acacias en la parte nororiental de Somalia. [193] Estos árboles, que pueden vivir 500 años, se talaban para fabricar carbón, muy demandado en la península Arábiga, donde las tribus beduinas de la región creen que la acacia es sagrada. [193] [194] [195] Sin embargo, aunque se trata de un combustible relativamente barato que satisface las necesidades de los usuarios, la producción de carbón vegetal suele conducir a la deforestación y la desertificación . [195] Como forma de abordar este problema, Jibrell y la Organización de Ayuda y Desarrollo del Cuerno de África (Horn Relief; ahora Adeso ), una organización de la que fue fundadora y directora ejecutiva, capacitaron a un grupo de adolescentes para educar al público sobre el daño permanente que puede crear la producción de carbón vegetal. En 1999, Horn Relief coordinó una marcha por la paz en la región nororiental de Puntland, en Somalia, para poner fin a las llamadas "guerras del carbón". Como resultado de los esfuerzos de cabildeo y educación de Jibrell, en 2000 el gobierno de Puntland prohibió la exportación de carbón. Desde entonces, el gobierno también ha aplicado la prohibición, lo que, según se informa, ha provocado una caída del 80% en las exportaciones del producto. [196] Jibrell recibió el Premio Ambiental Goldman en 2002 por sus esfuerzos contra la degradación ambiental y la desertificación. [196] En 2008, también ganó el Premio de la National Geographic Society / Fundación Buffett por Liderazgo en Conservación. [197]

Tras el enorme tsunami de diciembre de 2004 , también han surgido acusaciones de que, tras el estallido de la guerra civil somalí a finales de los años 1980, la extensa y remota costa de Somalia se utilizó como vertedero de residuos tóxicos. Se cree que las enormes olas que azotaron el norte de Somalia después del tsunami levantaron toneladas de residuos nucleares y tóxicos que podrían haber sido vertidos ilegalmente en el país por empresas extranjeras. [198]

El Partido Verde Europeo hizo caso omiso de estas revelaciones presentando ante la prensa y el Parlamento Europeo en Estrasburgo copias de contratos firmados por dos empresas europeas —la firma suiza italiana Achair Partners y un corredor de residuos italiano , Progresso— y representantes del entonces presidente de Somalia, el líder de la facción Ali Mahdi Mohamed, para aceptar 10 millones de toneladas de residuos tóxicos a cambio de 80 millones de dólares (en aquel entonces unos 60 millones de libras esterlinas). [198]

Según informes del Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente (PNUMA), los desechos han provocado un número mucho mayor de casos de infecciones respiratorias, úlceras y hemorragias bucales, hemorragias abdominales e infecciones cutáneas inusuales entre muchos habitantes de las zonas que rodean las ciudades nororientales de Hobyo y Benadir , en la costa del océano Índico, enfermedades que coinciden con las causadas por la radiación. El PNUMA añade que la situación a lo largo de la costa somalí plantea un peligro ambiental muy grave no sólo en Somalia, sino también en la subregión de África oriental. [198]

Debido a la proximidad de Somalia al ecuador , no hay mucha variación estacional en su clima. Las condiciones cálidas prevalecen durante todo el año junto con vientos monzónicos periódicos y lluvias irregulares. Las temperaturas máximas diarias medias varían de 30 a 40 °C (86 a 104 °F), excepto en elevaciones más altas a lo largo de la costa este, donde se pueden sentir los efectos de una corriente fría marina. En Mogadiscio, por ejemplo, las temperaturas máximas promedio por la tarde varían de 28 a 32 °C (82 a 90 °F) en abril. Algunas de las temperaturas medias anuales más altas del mundo se han registrado en el país; Berbera , en la costa noroeste, tiene una temperatura máxima por la tarde que promedia más de 38 °C (100 °F) de junio a septiembre. A nivel nacional, las temperaturas mínimas diarias promedio suelen variar de aproximadamente 15 a 30 °C (59 a 86 °F). [189] La mayor variedad climática se da en el norte de Somalia, donde las temperaturas a veces superan los 45 °C (113 °F) en julio en las llanuras litorales y caen por debajo del punto de congelación durante diciembre en las tierras altas. [182] [189] En esta región, la humedad relativa varía de aproximadamente el 40% a media tarde al 85% por la noche, cambiando un poco según la estación. [189] A diferencia de los climas de la mayoría de los demás países en esta latitud, las condiciones en Somalia varían de áridas en las regiones nororiental y central a semiáridas en el noroeste y el sur. En el noreste, la precipitación anual es inferior a 100 mm (4 pulgadas); en las mesetas centrales, es de aproximadamente 200 a 300 mm (8 a 12 pulgadas). Sin embargo, las partes noroccidental y suroccidental de la nación reciben considerablemente más lluvia, con un promedio de 510 a 610 mm (20 a 24 pulgadas) cayendo por año. Aunque las regiones costeras son cálidas y húmedas durante todo el año, el interior suele ser seco y caluroso. [189]

Existen cuatro estaciones principales en torno a las cuales gira la vida agrícola y pastoral, y estas están dictadas por los cambios en los patrones de viento. De diciembre a marzo se extiende la Jilal , la estación seca más dura del año. La principal estación lluviosa, conocida como Gu , dura de abril a junio. Este período se caracteriza por los monzones del suroeste, que rejuvenecen las tierras de pastoreo, especialmente la meseta central, y transforman brevemente el desierto en una exuberante vegetación. De julio a septiembre se extiende la segunda estación seca, la Xagaa (pronunciada "Hagaa"). El Dayr , que es la estación lluviosa más corta, dura de octubre a diciembre. [189] Los períodos tangambili que intervienen entre los dos monzones (octubre-noviembre y marzo-mayo) son cálidos y húmedos. [189]

Somalia contiene una variedad de mamíferos debido a su diversidad geográfica y climática. La vida silvestre que aún se encuentra presente incluye guepardos , leones , jirafas reticuladas , babuinos , servales , elefantes , jabalíes , gacelas , cabras montesas , kudús , dik-diks , oribis , asnos salvajes somalíes , reedbucks y cebras de Grévy , musarañas elefantes , damanes de roca , topos dorados y antílopes . También tiene una gran población de camellos dromedarios . [199]

Somalia es el hogar de alrededor de 727 especies de aves. De ellas, ocho son endémicas, una ha sido introducida por los seres humanos y una es rara o accidental. Catorce especies están amenazadas a nivel mundial. Las especies de aves que se encuentran exclusivamente en el país incluyen la paloma somalí , Alaemon hamertoni (Alaudidae), la abubilla menor, Heteromirafra archeri (Alaudidae), la alondra de Archer, Mirafra ashi , la alondra de Ash, Mirafra somalica (Alaudidae), la alondra somalí, Spizocorys obbiensis (Alaudidae), la alondra de Obbia, Carduelis johannis (Fringillidae) y el pardillo de Warsangli. [200]

Las aguas territoriales de Somalia son zonas de pesca privilegiadas para especies marinas altamente migratorias, como el atún. Una plataforma continental estrecha pero productiva contiene varias especies de peces demersales y crustáceos . [201] Las especies de peces que se encuentran exclusivamente en la nación incluyen Cirrhitichthys randalli ( Cirrhitidae ), Symphurus fuscus ( Cynoglossidae ), Parapercis simulata OC ( Pinguipedidae ), Cociella somaliensis OC ( Platycephalidae ) y Pseudochromis melanotus ( Pseudochromidae ).

Existen aproximadamente 235 especies de reptiles. De ellas, casi la mitad vive en las zonas del norte. Entre los reptiles endémicos de Somalia se encuentran la víbora de escamas de sierra de Hughes , la culebra de liga del sur de Somalia, un corredor ( Platyceps messanai ), una serpiente de diadema ( Spalerosophis josephscorteccii ), la boa de arena somalí , el lagarto gusano anguloso , un lagarto de cola espinosa ( Uromastyx macfadyeni ), el agama de Lanza, un geco ( Hemidactylus granchii ), el geco semáforo somalí y un lagarto de arena ( Mesalina o Eremias ). Una serpiente colúbrida ( Aprosdoketophis andreonei ) y el eslizón de Haacke-Greer ( Haackgreerius miopus ) son especies endémicas. [202]

Somalia es una república democrática representativa parlamentaria . El Presidente de Somalia es el jefe de Estado y comandante en jefe de las Fuerzas Armadas de Somalia y elige a un Primer Ministro para que actúe como jefe de gobierno . [203]

El Parlamento Federal de Somalia es el parlamento nacional de Somalia. La Asamblea Legislativa Nacional, bicameral, está formada por la Cámara del Pueblo (cámara baja) y el Senado (cámara alta), cuyos miembros son elegidos para ejercer mandatos de cuatro años. El Parlamento elige al Presidente, al Presidente del Parlamento y a los Vicepresidentes. También tiene autoridad para aprobar y vetar leyes. [204]

_(cropped).jpg/440px-UNPOS_CONFERENCE_SEPT_5th_and_6th,_Mogadishu_Somalia_(6129246599)_(cropped).jpg)

El poder judicial de Somalia está definido por la Constitución Provisional de la República Federal de Somalia. Adoptada el 1 de agosto de 2012 por una Asamblea Constitucional Nacional en Mogadiscio [205] [206], el documento fue elaborado por un comité de especialistas presidido por el abogado y Presidente del Parlamento Federal, Mohamed Osman Jawari [207] . Proporciona la base jurídica para la existencia de la República Federal y la fuente de la autoridad jurídica [208] .

La estructura de los tribunales nacionales está organizada en tres niveles: el Tribunal Constitucional, los tribunales del Gobierno Federal y los tribunales de los Estados . Una Comisión del Servicio Judicial, integrada por nueve miembros, nombra a cualquier miembro del poder judicial del nivel federal. También selecciona y presenta a los posibles jueces del Tribunal Constitucional a la Cámara del Pueblo del Parlamento Federal para su aprobación. Si recibe la aprobación, el Presidente nombra al candidato como juez del Tribunal Constitucional. El Tribunal Constitucional, integrado por cinco miembros, decide sobre cuestiones relativas a la constitución, además de sobre diversos asuntos federales y subnacionales. [208]

El derecho somalí se nutre de una mezcla de tres sistemas diferentes: el derecho civil , el derecho islámico y el derecho consuetudinario . [209]

Según los índices de democracia V-Dem de 2023, Somalia es el quinto país menos democrático de África . [210]

Después del colapso de Somalia en 1991 , no hubo relaciones ni ningún contacto entre el gobierno de Somalilandia , que se declaró un país, y el gobierno de Somalia . [211] [212]

.jpg/440px-2015_01_25_Turkish_President_Visit_to_Somalia-1_(16176887607).jpg)

Las relaciones exteriores de Somalia están a cargo del Presidente como jefe de Estado, el Primer Ministro como jefe de Gobierno y el Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores federal . [208]

De conformidad con el artículo 54 de la Constitución nacional, la asignación de poderes y recursos entre el Gobierno Federal y los Estados miembros federales constituyentes de la República Federal de Somalia será negociada y acordada por el Gobierno Federal y los Estados miembros federales, excepto en asuntos relacionados con asuntos exteriores, defensa nacional, ciudadanía e inmigración y política monetaria. El artículo 53 también estipula que el Gobierno Federal consultará a los Estados miembros federales sobre cuestiones importantes relacionadas con los acuerdos internacionales, incluidas las negociaciones sobre comercio exterior, finanzas y tratados. [208] El Gobierno Federal mantiene relaciones bilaterales con varios otros gobiernos centrales de la comunidad internacional. Entre ellos se encuentran Djibouti , Etiopía , Egipto , los Emiratos Árabes Unidos , el Yemen , Turquía , Italia , el Reino Unido , Dinamarca , Francia , los Estados Unidos , la República Popular China , el Japón , la Federación de Rusia y Corea del Sur .

Además, Somalia cuenta con varias misiones diplomáticas en el extranjero. Asimismo, existen varias embajadas y consulados extranjeros en la capital, Mogadiscio, y en otros lugares del país.

Somalia también es miembro de muchas organizaciones internacionales, como las Naciones Unidas , la Unión Africana y la Liga Árabe . Fue miembro fundador de la Organización de Cooperación Islámica en 1969. [213] Otras membresías incluyen el Banco Africano de Desarrollo , la Comunidad de África Oriental , el Grupo de los 77 , la Autoridad Intergubernamental para el Desarrollo , el Banco Internacional de Reconstrucción y Fomento , la Organización de Aviación Civil Internacional , la Asociación Internacional de Fomento , la Corporación Financiera Internacional , el Movimiento de Países No Alineados , la Federación Sindical Mundial y la Organización Meteorológica Mundial .

Las Fuerzas Armadas Somalíes (FAS) son las fuerzas militares de la República Federal de Somalia. [214] Encabezadas por el Presidente como Comandante en Jefe, tienen el mandato constitucional de garantizar la soberanía, la independencia y la integridad territorial de la nación. [208]

Las Fuerzas Armadas Somalíes estaban formadas inicialmente por el Ejército , la Armada , la Fuerza Aérea , la Fuerza de Policía y el Servicio de Seguridad Nacional . [215] En el período posterior a la independencia, se convirtió en uno de los ejércitos más grandes del continente. [139] El posterior estallido de la guerra civil en 1991 condujo a la disolución del Ejército Nacional Somalí. [216]

En 2004 se puso en marcha el proceso gradual de reconstitución del ejército con la creación del Gobierno Federal de Transición (GFT). Las Fuerzas Armadas somalíes están ahora supervisadas por el Ministerio de Defensa del Gobierno Federal de Somalia, creado a mediados de 2012. En enero de 2013, el Gobierno federal somalí reabrió también el servicio nacional de inteligencia en Mogadiscio, rebautizándolo como Agencia Nacional de Inteligencia y Seguridad (NISA). [217] Los gobiernos regionales de Somalilandia y Puntlandia mantienen sus propias fuerzas de seguridad y policía.

En Somalia, las relaciones sexuales entre personas del mismo sexo, tanto entre hombres como entre mujeres, se castigan con la muerte . [218] El 3 de octubre de 2020, un investigador de derechos humanos de la ONU expresó su preocupación por el retroceso del gobierno somalí en sus compromisos en materia de derechos humanos. [219]

Según la CIA y el Banco Central de Somalia , a pesar de experimentar disturbios civiles, Somalia ha mantenido una economía informal saludable , basada principalmente en la ganadería , las empresas de remesas / transferencia de dinero y las telecomunicaciones . [1] [45] Debido a la escasez de estadísticas gubernamentales formales y la reciente guerra civil , es difícil medir el tamaño o el crecimiento de la economía. Para 1994, la CIA estimó el PIB en $ 3.3 mil millones. [220] En 2001, se estimó en $ 4.1 mil millones. [221] Para 2009, la CIA estimó que el PIB había crecido a $ 5.731 mil millones, con una tasa de crecimiento real proyectada del 2,6%. [1] Según un informe de la Cámara de Comercio Británica de 2007 , el sector privado también creció, particularmente en el sector de servicios. A diferencia del período anterior a la guerra civil, cuando la mayoría de los servicios y el sector industrial estaban a cargo del gobierno , ha habido una inversión privada sustancial, aunque no medida, en actividades comerciales; Esto ha sido financiado en gran medida por la diáspora somalí e incluye comercio y marketing, servicios de transferencia de dinero, transporte, comunicaciones, equipos de pesca, aerolíneas, telecomunicaciones, educación, salud, construcción y hoteles. [222] El economista libertario Peter Leeson atribuye esta mayor actividad económica a la ley consuetudinaria somalí (conocida como Xeer ), que, según él, proporciona un entorno estable para realizar negocios. [223]

Según el Banco Central de Somalia, el PIB per cápita del país en 2012 [update]es de 226 dólares, una ligera reducción en términos reales respecto de 1990. Alrededor del 43% de la población vive con menos de 1 dólar estadounidense al día, y alrededor del 24% de ellos vive en zonas urbanas y el 54% en zonas rurales. [45]

La economía de Somalia se compone de una producción tradicional y otra moderna, con una transición gradual hacia técnicas industriales modernas. Somalia tiene la mayor población de camellos del mundo. [224] Según el Banco Central de Somalia, alrededor del 80% de la población son pastores nómadas o seminómadas, que crían cabras, ovejas, camellos y ganado vacuno. Los nómadas también recogen resinas y gomas para complementar sus ingresos. [45]

Agriculture is the most important economic sector of Somalia. It accounts for about 65% of the GDP and employs 65% of the workforce.[222] Livestock contributes about 40% to GDP and more than 50% of export earnings.[1] Other principal exports include fish, charcoal and bananas; sugar, sorghum and corn are products for the domestic market.[1] According to the Central Bank of Somalia, imports of goods total about $460 million per year, surpassing aggregate imports prior to the start of the civil war in 1991. Exports, which total about $270 million annually, have also surpassed pre-war aggregate export levels. Somalia has a trade deficit of about $190 million per year, but this is exceeded by remittances sent by Somalis in the diaspora, estimated to be about $1 billion.[45]

With the advantage of being located near the Arabian Peninsula, Somali traders have increasingly begun to challenge Australia's traditional dominance over the Gulf Arab livestock and meat market, offering quality animals at very low prices. In response, Gulf Arab states have started to make strategic investments in the country, with Saudi Arabia building livestock export infrastructure and the United Arab Emirates purchasing large farmlands.[225] Somalia is also a major world supplier of frankincense and myrrh.[226]

The modest industrial sector, based on the processing of agricultural products, accounts for 10% of Somalia's GDP.[1] According to the Somali Chamber of Commerce and Industry, over six private airline firms also offer commercial flights to both domestic and international locations, including Daallo Airlines, Jubba Airways, African Express Airways, East Africa 540, Central Air and Hajara.[227] In 2008, the Puntland government signed a multimillion-dollar deal with Dubai's Lootah Group, a regional industrial group operating in the Middle East and Africa. According to the agreement, the first phase of the investment is worth Dhs 170 m and will see a set of new companies established to operate, manage and build Bosaso's free trade zone and sea and airport facilities. The Bosaso Airport Company is slated to develop the airport complex to meet international standards, including a new 3,400 m (11,200 ft) runway, main and auxiliary buildings, taxi and apron areas, and security perimeters.[228]

Prior to the outbreak of the civil war in 1991, the roughly 53 state-owned small, medium and large manufacturing firms were foundering, with the ensuing conflict destroying many of the remaining industries. However, primarily as a result of substantial local investment by the Somali diaspora, many of these small-scale plants have re-opened and newer ones have been created. The latter include fish-canning and meat-processing plants in the northern regions, as well as about 25 factories in the Mogadishu area, which manufacture pasta, mineral water, confections, plastic bags, fabric, hides and skins, detergent and soap, aluminium, foam mattresses and pillows, fishing boats, carry out packaging, and stone processing.[229] In 2004, an $8.3 million Coca-Cola bottling plant also opened in the city, with investors hailing from various constituencies in Somalia.[230] Foreign investment also included multinationals including General Motors and Dole Fruit.[231]

The Central Bank of Somalia is the official monetary authority of Somalia.[45] In terms of financial management, it is in the process of assuming the task of both formulating and implementing monetary policy.[232]

Owing to a lack of confidence in the local currency, the US dollar is widely accepted as a medium of exchange alongside the Somali shilling. Dollarization notwithstanding, the large issuance of the Somali shilling has increasingly fuelled price hikes, especially for low value transactions. According to the Central Bank, this inflationary environment is expected to come to an end as soon as the bank assumes full control of monetary policy and replaces the presently circulating currency introduced by the private sector.[232]

Although Somalia has had no central monetary authority for more than 15 years between the outbreak of the civil war in 1991 and the subsequent re-establishment of the Central Bank of Somalia in 2009, the nation's payment system is fairly advanced primarily due to the widespread existence of private money transfer operators (MTO) that have acted as informal banking networks.[233]

These remittance firms (hawalas) have become a large industry in Somalia, with an estimated US$1.6 billion annually remitted to the region by Somalis in the diaspora via money transfer companies.[1] Most are members of the Somali Money Transfer Association (SOMTA), an umbrella organization that regulates the community's money transfer sector, or its predecessor, the Somali Financial Services Association (SFSA).[234][235] The largest of the Somali MTOs is Dahabshiil, a Somali-owned firm employing more than 2,000 people across 144 countries with branches in London and Dubai.[235]

With a significant improvement in local security, Somali expatriates began returning to the country for investment opportunities. Coupled with modest foreign investment, the inflow of funds have helped the Somali shilling increase considerably in value. By March 2014, the currency had appreciated by almost 60% against the U.S. dollar over the previous 12 months. The Somali shilling was the strongest among the 175 global currencies traded by Bloomberg, rising close to 50 percentage points higher than the next most robust global currency over the same period.[236]

The Somalia Stock Exchange (SSE) is the national bourse of Somalia. It was founded in 2012 to attract investment from both Somali-owned firms and global companies in order to accelerate the ongoing post-conflict reconstruction process in Somalia.[237]

The World Bank reports that electricity is now in large part supplied by local businesses.[222] Among these domestic firms is the Somali Energy Company, which performs generation, transmission and distribution of electric power.[238] In 2010, the nation produced 310 million kWh and consumed 288.3 million kWh of electricity, ranked 170th and 177th, respectively, according to the CIA.[1][needs update]

Somalia has reserves of several natural resources, including uranium, iron ore, tin, gypsum, bauxite, copper, salt and natural gas. The CIA reports that there are 5.663 billion cubic metres of proven natural gas reserves.[1]

The presence or extent of proven oil reserves in Somalia is uncertain. The CIA asserts that as of 2011[update] there are no proven reserves of oil in the country,[1] while UNCTAD suggests that most proven oil reserves in Somalia lie off its northwestern coast, in the Somaliland region.[239] An oil group listed in Sydney, Range Resources, estimates that the Puntland region in the northeast has the potential to produce 5 billion barrels (790×106 m3) to 10 billion barrels (1.6×109 m3) of oil,[240] compared to the 6.7 billion barrels of proven oil reserves in Sudan.[241] As a result of these developments, the Somalia Petroleum Corporation was established by the federal government.[242]

In the late 1960s, UN geologists also discovered major uranium deposits and other rare mineral reserves in Somalia. The find was the largest of its kind, with industry experts estimating that the amount of the deposits could amount to over 25% of the world's then known uranium reserves of 800,000 tons.[243] In 1984, the IUREP Orientation Phase Mission to Somalia reported that the country had 5,000 tons of uranium reasonably assured resources (RAR), 11,000 tons of uranium estimated additional resources (EAR) in calcrete deposits, as well as 0–150,000 tons of uranium speculative resources (SR) in sandstone and calcrete deposits.[244] Somalia evolved into a major world supplier of uranium, with American, UAE, Italian and Brazilian mineral companies vying for extraction rights. Link Natural Resources has a stake in the central region, and Kilimanjaro Capital has a stake in the 1,161,400 acres (470,002 ha) Amsas-Coriole-Afgoi (ACA) Block, which includes uranium exploration.[245]

The Trans-National Industrial Electricity and Gas Company is an energy conglomerate based in Mogadishu. It unites five major Somali companies from the trade, finance, security and telecommunications sectors, following a 2010 joint agreement signed in Istanbul to provide electricity and gas infrastructure in Somalia. With an initial investment budget of $1 billion, the company launched the Somalia Peace Dividend Project, a labour-intensive energy program aimed at facilitating local industrialization initiatives.

According to the Central Bank of Somalia, as the nation embarks on the path of reconstruction, the economy is expected not only to match its pre-civil war levels, but also to accelerate in growth and development due to Somalia's untapped natural resources.[45]

After the start of the civil war, various new telecommunications companies began to spring up and compete to provide missing infrastructure. Funded by Somali entrepreneurs and backed by expertise from China, South Korea and Europe, these nascent telecommunications firms offer affordable mobile phone and Internet services that are not available in many other parts of the continent. Customers can conduct money transfers (such as through the popular Dahabshiil) and other banking activities via mobile phones, as well as easily gain wireless Internet access.[246]

After forming partnerships with multinational corporations such as Sprint, ITT and Telenor, these firms now offer the cheapest and clearest phone calls in Africa.[247] These Somali telecommunication companies also provide services to every city and town in Somalia. There are presently around 25 mainlines per 1,000 persons, and the local availability of telephone lines (tele-density) is higher than in neighbouring countries; three times greater than in adjacent Ethiopia.[229] Prominent Somali telecommunications companies include Golis Telecom Group, Hormuud Telecom, Somafone, Nationlink, Netco, Telcom and Somali Telecom Group. Hormuud Telecom alone grosses about $40 million a year. Despite their rivalry, several of these companies signed an inter-connectivity deal in 2005 that allows them to set prices, maintain and expand their networks, and ensure that competition does not get out of control.[246]

The state-run Somali National Television is the principal national public service TV channel. After a twenty-year hiatus, the station was officially re-launched on 4 April 2011.[248] Its radio counterpart Radio Mogadishu also broadcasts from the capital. Somaliland National TV and Puntland TV and Radio air from the northern regions.

Additionally, Somalia has several private television and radio networks. Among these are Horn Cable Television and Universal TV.[1] The political Xog Doon and Xog Ogaal and Horyaal Sports broadsheets publish out of the capital. There are also a number of online media outlets covering local news,[249] including Garowe Online, Wardheernews, and Puntland Post.

The internet country code top-level domain (ccTLD) for Somalia is .so. It was officially relaunched on 1 November 2010 by .SO Registry, which is regulated by the nation's Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications.[250]

In November 2013, following a Memorandum of Understanding signed with Emirates Post in April of the year, the federal Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications officially reconstituted the Somali Postal Service (Somali Post).[251] In October 2014, the ministry also relaunched postal delivery from abroad.[252]

Somalia has a number of local attractions, consisting of historical sites, beaches, waterfalls, mountain ranges and national parks. The tourist industry is regulated by the national Ministry of Tourism. The autonomous Puntland and Somaliland regions maintain their own tourism offices.[253] The Somali Tourism Association (SOMTA) also provides consulting services from within the country on the national tourist industry.[254] As of March 2015, the Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife of the South West State announced that it is slated to establish additional game reserves and wildlife ranges.[255] The United States Government recommends travelers to not travel to Somalia.[256]

Notable sights include the Laas Geel caves containing Neolithic rock art; the Cal Madow, Golis Mountains and Ogo Mountains; the Iskushuban and Lamadaya waterfalls; and the Hargeisa National Park, Jilib National Park, Kismayo National Park and Lag Badana National Park.

Somalia's network of roads is 22,100 km (13,700 mi) long. As of 2000[update], 2,608 km (1,621 mi) streets are paved and 19,492 km (12,112 mi) are unpaved.[1] A 750 km (470 mi) highway connects major cities in the northern part of the country, such as Bosaso, Galkayo and Garowe, with towns in the south.[257]

The Somali Civil Aviation Authority (SOMCAA) is Somalia's national civil aviation authority body. After a long period of management by the Civil Aviation Caretaker Authority for Somalia (CACAS), SOMCAA is slated to re-assume control of Somalia's airspace by 31 December 2013.