Se sabe que la región de Macedonia estuvo habitada desde el Paleolítico .

Los primeros habitantes históricos de la región fueron los pelasgos , [1] los briges [1] y los tracios . Los pelasgos ocuparon Emathia y los briges ocuparon el norte de Epiro , [2] así como Macedonia , principalmente al oeste del río Axios y partes de Migdonia . Los tracios, en los primeros tiempos, ocuparon principalmente las partes orientales de Macedonia ( Migdonia , Crestonia , Bisaltia ). Los antiguos macedonios no aparecen en los primeros relatos históricos porque habían estado viviendo en los extremos meridionales de la región (las tierras altas de Orestia ) desde antes de la Edad Oscura . [3] [4] Las tribus macedonias posteriormente se trasladaron desde Orestis en el Alto Haliacmon debido a la presión de las Orestae . [a]

El nombre de la región de Macedonia ( griego : Μακεδονία , Makedonia ) deriva del nombre tribal de los antiguos macedonios ( griego : Μακεδώνες , Makedónes ). Según el historiador griego Heródoto , los Makednoi ( griego : Mακεδνοί ) eran una tribu dórica que se quedó atrás durante la gran migración hacia el sur de los griegos dóricos . [6] [ página requerida ] La palabra "Makednos" es cognada con la palabra griega dórica "Μάκος" Μakos ( forma ática Μήκος – "mékos"), que en griego significa "longitud". Los antiguos macedonios tomaron este nombre porque eran físicamente altos o porque se asentaron en las montañas. La última definición traduciría "macedonio" como "montañés".

Los macedonios ( griego : Μακεδόνες , Makedónes ) eran una antigua tribu que vivía en la llanura aluvial alrededor de los ríos Haliacmon y Axios inferior en la parte noreste de la Grecia continental . Esencialmente un pueblo griego antiguo , [7] se expandieron gradualmente desde su tierra natal a lo largo del valle de Haliacmon en el borde norte del mundo griego, absorbiendo o expulsando a las tribus vecinas no griegas, principalmente tracias e ilirias . [8] Hablaban macedonio antiguo , que era una lengua hermana del griego antiguo o un dialecto griego dórico , aunque la lengua de prestigio de la región fue al principio el griego ático y luego el griego koiné . [9] Sus creencias religiosas reflejaban las de otros griegos , siguiendo a las principales deidades del panteón griego , aunque los macedonios continuaron las prácticas funerarias arcaicas que habían cesado en otras partes de Grecia después del siglo VI a. C. Aparte de la monarquía, el núcleo de la sociedad macedonia era su nobleza. Al igual que la aristocracia de la vecina Tesalia , su riqueza se basaba en gran medida en el pastoreo de caballos y ganado .

Aunque compuesto por varios clanes, el reino de Macedonia , establecido alrededor del siglo VIII a. C., está principalmente asociado con la dinastía Argead y la tribu que lleva su nombre. La dinastía fue supuestamente fundada por Pérdicas I , descendiente del legendario Témeno de Argos , mientras que la región de Macedonia tal vez deriva su nombre de Makedon , una figura de la mitología griega . Tradicionalmente gobernados por familias independientes, los macedonios parecen haber aceptado el gobierno de Argead en la época de Alejandro I ( r. 498-454 a. C.– ). Bajo Filipo II ( r. 359-336 a. C.– ), a los macedonios se les atribuyen numerosas innovaciones militares , que ampliaron su territorio y aumentaron su control sobre otras áreas que se extendían hasta Tracia . Esta consolidación del territorio permitió las hazañas de Alejandro Magno ( r. 336–323 a. C.– ), la conquista del Imperio aqueménida , el establecimiento de los estados sucesores diádocos y la inauguración del período helenístico en Asia occidental , Grecia y el mundo mediterráneo en general . Los macedonios fueron finalmente conquistados por la República romana , que desmanteló la monarquía macedonia al final de la Tercera Guerra Macedónica (171–168 a. C.) y estableció la provincia romana de Macedonia después de la Cuarta Guerra Macedónica (150–148 a. C.).

Antes del reinado de Alejandro I , padre de Pérdicas II , los antiguos macedonios vivían principalmente en tierras adyacentes al Haliakmon , en el extremo sur de la moderna provincia griega de Macedonia . A Alejandro se le atribuye haber añadido a Macedonia muchas de las tierras que se convertirían en parte del territorio central macedonio: Pieria, Bottiaia , Migdonia y Eordaia (Thuc. 2.99). Antemo, Crestonia y Bisaltia también parecen haber sido añadidas durante su reinado (Thuc. 2.99). La mayoría de estas tierras estaban habitadas anteriormente por tribus tracias, y Tucídides registra cómo los tracios fueron empujados a las montañas cuando los macedonios adquirieron sus tierras. [ cita requerida ]

Generaciones después de Alejandro, Filipo II de Macedonia añadiría nuevas tierras a Macedonia , y también reduciría a potencias vecinas como los ilirios y los peonios, que lo habían atacado cuando se convirtió en rey, a pueblos semiautónomos. En la época de Filipo, los macedonios se expandieron y se establecieron en muchos de los nuevos territorios adyacentes, y Tracia hasta el Nesto fue colonizada por colonos macedonios. Sin embargo, Estrabón testifica que la mayor parte de la población que habitaba en la Alta Macedonia seguía siendo de ascendencia traco-iliria . El hijo de Filipo, Alejandro Magno, extendió el poder macedonio sobre ciudades-estado griegas clave, y sus campañas, tanto locales como en el extranjero, harían que el poder macedonio fuera supremo desde Grecia hasta Persia , Egipto y el borde de la India.

Después de este período hubo repetidas invasiones bárbaras de los Balcanes por parte de los celtas . [ cita requerida ]

Después de la derrota de Andrisco en 148 a. C., Macedonia se convirtió oficialmente en una provincia de la República romana en 146 a. C. La helenización de la población no griega aún no estaba completa en 146 a. C., y muchas de las tribus tracias e ilirias habían conservado sus lenguas. También es posible que todavía se hablara la antigua lengua macedonia, junto con la koiné , la lengua griega común de la era helenística . Desde un período temprano, la provincia romana de Macedonia incluía Epiro , Tesalia , partes de Tracia e Iliria , lo que hizo que la región de Macedonia perdiera permanentemente cualquier conexión con sus antiguas fronteras, y ahora sea el hogar de una mayor variedad de habitantes. [10]

A medida que el estado griego de Bizancio emergía gradualmente como un estado sucesor del Imperio Romano , Macedonia se convirtió en una de sus provincias más importantes, ya que estaba cerca de la capital del Imperio ( Constantinopla ) e incluía su segunda ciudad más grande ( Tesalónica ). Según los mapas bizantinos que fueron registrados por Ernest Honigmann, en el siglo VI d. C. había dos provincias que llevaban el nombre de "Macedonia" en las fronteras del Imperio [ cita requerida ] :

Macedonia fue devastada varias veces en los siglos IV y V por los ataques desoladores de los visigodos , hunos y vándalos . Estos hicieron poco por cambiar su composición étnica (la región estaba casi completamente poblada por griegos o pueblos helenizados en ese momento), pero dejaron gran parte de la región despoblada.

Más tarde, alrededor del año 800 d. C., la emperatriz Irene organizó una nueva provincia del Imperio bizantino, Macedonia , a partir del thema de Tracia. No tenía relación con la región histórica o geográfica de Macedonia, sino que estaba centrada en Tracia , incluida la zona desde Adrianópolis (la capital del thema) y el valle de Evros hacia el este a lo largo del mar de Mármara . No incluía ninguna parte de la antigua Macedonia , que (en la medida en que los bizantinos la controlaban) estaba en el thema de Tesalónica.

Aprovechando la desolación dejada por las tribus nómadas, los eslavos se asentaron en la península balcánica a partir del siglo VI d. C. [11] (véase también: Eslavos del sur ) . Ayudadas por los ávaros y por los búlgaros turcos , las tribus eslavas en el siglo VI iniciaron una invasión gradual en las tierras de Bizancio . Se infiltraron en Macedonia y llegaron tan al sur como Tesalia y el Peloponeso , estableciéndose en regiones aisladas que los bizantinos llamaron Sclavinias , hasta que fueron pacificadas gradualmente. Muchos eslavos vinieron a servir como soldados en los ejércitos bizantinos y se establecieron en otras partes del Imperio bizantino. Los colonos eslavos asimilaron a muchos [ cuantificar ] entre la población peonia, iliria y tracia romanizada y helenizada de Macedonia, pero los grupos de tribus que huyeron a las montañas permanecieron independientes. [12] [ página necesaria ] Muchos estudiosos consideran hoy que los actuales arrumanos (valacos), sarakatsani y albaneses tienen su origen en estas poblaciones montañosas. La interacción entre los pueblos indígenas romanizados y no romanizados y los eslavos dio lugar a similitudes lingüísticas que se reflejan en el búlgaro , albanés , rumano y macedonio modernos , todos ellos miembros del área lingüística de los Balcanes . Los eslavos también ocuparon el interior de Tesalónica, lanzando ataques consecutivos contra la ciudad en 584, 586, 609, 620 y 622 d. C., pero nunca la tomaron. Destacamentos de ávaros a menudo se unieron a los eslavos en sus ataques, pero los ávaros no formaron ningún asentamiento duradero en la región. Sin embargo, una rama de los búlgaros liderada por el kan Kuber se estableció en Macedonia occidental y Albania oriental alrededor de 680 d. C. y también participó en ataques a Bizancio junto con los eslavos . En esa época, varias etnias diferentes habitaban toda la región de Macedonia; los eslavos del sur formaban la mayoría absoluta en las franjas septentrionales de Macedonia [13] [14], mientras que los griegos dominaban las tierras altas del oeste de Macedonia, las llanuras centrales y la costa.

A principios del siglo IX, Bulgaria conquistó las tierras bizantinas del norte, incluidas Macedonia B y parte de Macedonia A. Esas regiones permanecieron bajo el dominio búlgaro durante dos siglos, hasta la destrucción de Bulgaria por el emperador bizantino Basilio II (apodado "el matador de búlgaros") en 1018. En los siglos XI y XII, se menciona por primera vez históricamente a dos grupos étnicos justo en las fronteras de Macedonia: los arvanitas en la actual Albania y los valacos (arrumanos) en Tesalia y Pindo. Los historiadores modernos están divididos en cuanto a si los albaneses llegaron a la zona en esa época (desde Dacia o Moesia) o si procedían de las poblaciones nativas tracias o ilirias no romanizadas.

También en el siglo XI, Bizancio instaló a varias decenas de miles de cristianos turcos de Asia Menor , conocidos como vardariotas , a lo largo del curso inferior del Vardar. También se introdujeron colonias de otras tribus turcas, como los uzes, los pechenegos y los cumanos, en varios períodos desde el siglo XI hasta el XIII. Todos ellos fueron finalmente helenizados o bulgarizados. Los romaníes , que migraron desde el norte de la India, llegaron a los Balcanes, incluida Macedonia, alrededor del siglo XIV, y algunos de ellos se establecieron allí. También se produjeron oleadas sucesivas de inmigración romaní en los siglos XV y XVI. (Véase también: Roma en la República de Macedonia )

En los siglos XIII y XIV, el Imperio bizantino, el Despotado de Epiro , los gobernantes de Tesalia y el Imperio búlgaro se disputaron el control de la región de Macedonia, pero el frecuente cambio de fronteras no dio lugar a grandes cambios de población. [ cita requerida ] En 1338, el Imperio serbio conquistó la zona, pero después de la batalla de Maritsa en 1371, la mayoría de los señores serbios de Macedonia reconocieron la soberanía otomana . Después de la conquista de Skopie por los turcos otomanos en 1392, la mayor parte de Macedonia se incorporó formalmente al Imperio otomano .

El período inicial del dominio otomano condujo a una despoblación de las llanuras y valles fluviales de Macedonia. La población cristiana huyó a las montañas. Los otomanos fueron traídos en gran parte desde Asia Menor y se establecieron en partes de la región. Las ciudades destruidas en Vardar Macedonia durante la conquista fueron renovadas, esta vez pobladas exclusivamente por musulmanes. El elemento otomano en Macedonia fue especialmente fuerte en los siglos XVII y XVIII, y los viajeros definieron a la mayoría de la población, especialmente la urbana, como musulmana. Sin embargo, la población otomana disminuyó drásticamente a fines del siglo XVIII y principios del siglo XIX debido a las incesantes guerras lideradas por el Imperio Otomano, la baja tasa de natalidad y el mayor número de muertes por las frecuentes epidemias de peste entre los musulmanes que entre los cristianos.

La guerra otomano-habsburgo (1683-1699), la posterior huida de una parte sustancial de la población serbia de Kosovo a Austria y las represalias y saqueos durante la contraofensiva otomana provocaron una afluencia de musulmanes albaneses a Kosovo, el norte y el noroeste de Macedonia. Estando en posición de poder, los musulmanes albaneses lograron expulsar a sus vecinos cristianos y conquistaron territorios adicionales en los siglos XVIII y XIX. Las presiones del gobierno central tras la primera guerra ruso-turca que terminó en 1774 y en la que los griegos otomanos estuvieron implicados como una "quinta columna" llevaron a la islamización superficial de varios miles de hablantes de griego en Macedonia occidental. Estos musulmanes griegos conservaron su idioma e identidad griegos, siguieron siendo criptocristianos y posteriormente fueron llamados Vallahades por los cristianos ortodoxos griegos locales porque aparentemente el único turcoárabe que alguna vez se molestaron en aprender fue cómo decir "wa-llahi" o "por Alá". [15] La destrucción y el abandono de la ciudad cristiana arrumana de Moscopole y otros asentamientos arrumanos importantes en la región del sur de Albania (Epiro-Macedonia) en la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII provocó una migración a gran escala de miles de arrumanos a las ciudades y pueblos de Macedonia occidental, sobre todo a Bitola , Krushevo y las regiones circundantes. Salónica también se convirtió en el hogar de una gran población judía después de las expulsiones de judíos por parte de España después de 1492. Los judíos más tarde formaron pequeñas colonias en otras ciudades macedonias, sobre todo Bitola y Serres .

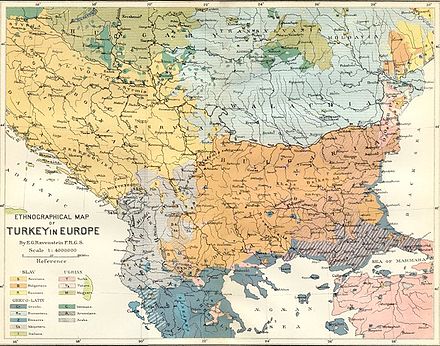

.jpg/440px-Balkans-ethnic_(1877).jpg)

El auge del nacionalismo europeo en el siglo XVIII condujo a la expansión de la idea helénica en Macedonia. Su pilar principal a lo largo de los siglos de dominio otomano había sido la población griega indígena de la Macedonia histórica. Sin embargo, bajo la influencia de las escuelas griegas y del Patriarcado de Constantinopla , comenzó a extenderse entre los demás súbditos ortodoxos del Imperio a medida que la población cristiana urbana de origen eslavo y albanés comenzó a verse cada vez más como griega. La lengua griega se convirtió en un símbolo de civilización y un medio básico de comunicación entre los no musulmanes. El proceso de helenización se reforzó aún más después de la abolición del Arzobispado búlgaro de Ohrid en 1767. Aunque con un clero predominantemente griego, el Arzobispado no cedió a la orden directa de Constantinopla y tuvo autonomía en muchos dominios vitales. Sin embargo, la pobreza del campesinado cristiano y la falta de una educación adecuada en las aldeas preservaron la diversidad lingüística del campo macedonio. La idea helénica alcanzó su apogeo durante la Guerra de Independencia griega (1821-1829), que recibió el apoyo activo de la población macedonia griega como parte de su lucha por la resurrección del Estado griego. Según el Istituto Geografiko de Agostini de Roma, en 1903 en los vilayatos de Selanik y Monastir el griego era la lengua dominante de instrucción en la región: [19]

Sin embargo, la independencia del reino griego asestó un golpe casi fatal a la idea helénica en Macedonia. La huida de la intelectualidad macedonia a la Grecia independiente y los cierres masivos de escuelas griegas por parte de las autoridades otomanas debilitaron la presencia helénica en la región durante un siglo, hasta la incorporación de la Macedonia histórica a Grecia tras las guerras de los Balcanes en 1913.

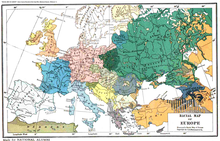

.jpg/440px-Europe_ethnic_map_1897_(hungarian).jpg)

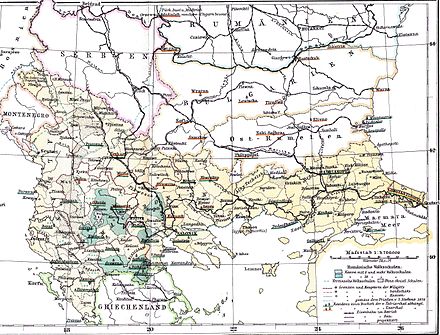

.jpg/440px-Balkans-ethnic_(1861).jpg)

La mayoría de la población de Macedonia fue descrita como búlgara durante los siglos XVI y XVII por historiadores y viajeros otomanos como Hoca Sadeddin Efendi , Mustafa Selaniki , Hadji Khalfa y Evliya Çelebi . Sin embargo, el nombre significaba bastante poco en vista de la opresión política por parte de los otomanos y la religiosa y cultural por parte del clero griego. El idioma búlgaro se conservó como medio cultural solo en un puñado de monasterios, y ascender en términos de estatus social para el búlgaro común generalmente significaba atravesar un proceso de helenización . Sin embargo, la liturgia eslava se conservó en los niveles inferiores del arzobispado búlgaro de Ohrid durante varios siglos hasta su abolición en 1767.

El creador de la historiografía búlgara moderna, Petar Bogdan Bakshev, en su primera obra " Descripción del reino búlgaro " de 1640, mencionó las fronteras geográficas y étnicas de Bulgaria y del pueblo búlgaro, incluida también " la mayor parte de Macedonia... hasta Ohrid, hasta las fronteras de Albania y Grecia... ". Hristofor Zhefarovich , un pintor del siglo XVIII nacido en Macedonia, tuvo una influencia crucial en el Renacimiento nacional búlgaro y afectó significativamente a toda la heráldica búlgara del siglo XIX, cuando se volvió más influyente entre todas las generaciones de ilustrados y revolucionarios búlgaros y dio forma a la idea de un símbolo nacional búlgaro moderno. En su testamento, señaló explícitamente que sus parientes eran "de nacionalidad búlgara" y de Dojran . Aunque la primera obra literaria en búlgaro moderno, Historia de los eslavos búlgaros, fue escrita por un monje búlgaro nacido en Macedonia, Paisio de Hilendar , en fecha tan temprana como 1762, la idea búlgara tardó casi un siglo en recuperar su predominio en la región. El avance búlgaro en Macedonia en el siglo XIX se vio facilitado por la superioridad numérica de los búlgaros tras la disminución de la población turca , así como por su mejor situación económica. Los búlgaros de Macedonia participaron activamente en la lucha por un patriarcado búlgaro independiente y por las escuelas búlgaras.

Los representantes de la intelectualidad escribían en una lengua que llamaban búlgaro y luchaban por una representación más uniforme de los dialectos búlgaros locales hablados en Macedonia en el búlgaro formal. El Exarcado búlgaro autónomo establecido en 1870 incluía el noroeste de Macedonia. Después de la abrumadora votación de los distritos de Ohrid y Skopje , creció hasta incluir toda la actual Macedonia de Vardar y Pirin en 1874. [20] Este proceso de resurgimiento nacional búlgaro en Macedonia, sin embargo, fue mucho menos exitoso en la Macedonia histórica, que junto a los eslavos tenía poblaciones compactas griegas y arrumanas . La idea helénica y el Patriarcado de Constantinopla conservaron gran parte de su influencia anterior entre los búlgaros locales y la llegada de la idea búlgara convirtió a la región en un campo de batalla entre los que debían lealtad al Patriarcado y los que debían lealtad al Exarcado, con líneas divisorias que a menudo separaban a la familia y los parientes. En la Conferencia de Constantinopla , celebrada en el período de diciembre de 1876 - enero de 1877, con la participación del Imperio Otomano y las 6 grandes potencias europeas , se decidió crear 2 vilayatos búlgaros autónomos - Oriental y Occidental - en los territorios europeos del Imperio Otomano, y en el segundo con capital Sofía incluía la mayor parte de la región de Macedonia, a pesar de que el Levantamiento de Abril de la primavera de 1876, que atrajo la atención internacional sobre la cuestión nacional búlgara, apenas estalló allí. [21]

[ cita requerida ]

Los etnógrafos y lingüistas europeos, hasta el Congreso de Berlín, solían considerar el búlgaro como la lengua de la población eslava de Macedonia . Los franceses Ami Boué en 1840 y Guillaume Lejean en 1861, los alemanes August Grisebach en 1841, J. Hahn en 1858 y 1863, August Heinrich Petermann en 1869 y Heinrich Kiepert en 1876, el eslovaco Pavel Jozef Šafárik en 1842 y los checos Karel Jaromír Erben en 1868 y F. Brodaska en 1869, los ingleses James Wyld en 1877 y Georgina Muir Mackenzie y Adeline Paulina Irby en 1863, los serbios Davidovitch en 1848, Constant Desjardins en 1853 y Stjepan Verković en 1860, los rusos Victor Grigorovich en 1848 Vikentij Makušev y Mikhail Mirkovich en 1867, así como En 1878, el austríaco Karl Sax publicó libros etnográficos o lingüísticos, o notas de viaje, en los que definía a la población eslava de Macedonia como búlgara. En 1844, el médico austríaco Josef Müller publicó notas de viaje en las que consideraba que la población eslava de Macedonia era serbia. En 1877, el francés F. Bianconi y el inglés Edward Stanford identificaron la región como predominantemente griega. Sostuvo que la población urbana de Macedonia era completamente griega, mientras que el campesinado era de origen mixto búlgaro-griego y tenía conciencia griega, pero aún no dominaba la lengua griega.

En Europa, los estados no nacionales clásicos fueron los imperios multiétnicos como el Imperio Otomano, gobernado por un sultán y cuya población pertenecía a muchos grupos étnicos, que hablaban muchos idiomas. La idea del estado-nación fue un énfasis creciente durante el siglo XIX, en los orígenes étnicos y raciales de las naciones. La característica más notable fue el grado en que los estados-nación utilizan el estado como un instrumento de unidad nacional , en la vida económica, social y cultural. Para el siglo XIX, los otomanos se habían quedado muy por detrás del resto de Europa en ciencia, tecnología e industria. En ese momento, los búlgaros habían iniciado una lucha decidida contra los clérigos griegos . Los líderes religiosos búlgaros se habían dado cuenta de que cualquier lucha adicional por los derechos de los búlgaros en el Imperio Otomano no podría tener éxito a menos que lograran obtener al menos algún grado de autonomía del Patriarcado de Constantinopla . La fundación del Exarcado Búlgaro en 1870, que incluía la mayor parte de Macedonia, mediante un firman del Sultán Abdülaziz, fue el resultado directo de la lucha de los ortodoxos búlgaros contra la dominación del Patriarcado griego de Constantinopla en las décadas de 1850 y 1860.

Posteriormente, en 1876, los búlgaros se rebelaron en el Levantamiento de Abril . El surgimiento de los sentimientos nacionales búlgaros estuvo estrechamente relacionado con el restablecimiento de la iglesia búlgara independiente. Este aumento de la conciencia nacional se conoció como el Renacimiento Nacional Búlgaro . Sin embargo, el levantamiento fue aplastado por los otomanos. Como resultado, en la Conferencia de Constantinopla de 1876, el carácter búlgaro predominante de los eslavos en Macedonia se reflejó en las fronteras de la futura Bulgaria autónoma tal como se trazaron allí. Las grandes potencias finalmente dieron su consentimiento a la variante, que excluía a Macedonia histórica y Tracia , y negaba a Bulgaria el acceso al mar Egeo , pero por lo demás incorporaba todas las demás regiones del Imperio Otomano habitadas por búlgaros. Sin embargo, en el último minuto, los otomanos rechazaron el plan con el apoyo secreto de Gran Bretaña. Con su reputación en juego, Rusia no tuvo otra opción que declarar la guerra a los otomanos en abril de 1877. El Tratado de San Stefano de 1878, que reflejaba el máximo deseado por la política expansionista rusa, dio a Bulgaria toda Macedonia excepto Salónica , la península de Calcídica y el valle del Aliakmon .

El Congreso de Berlín de ese mismo año redistribuyó al Imperio Otomano la mayor parte de los territorios búlgaros que el tratado anterior había otorgado al Principado de Bulgaria, incluida toda Macedonia. Como resultado, a finales de 1878 estalló el levantamiento de Kresna-Razlog , una revuelta búlgara fallida contra el dominio otomano en la región de Macedonia. Sin embargo, la decisión tomada en el Congreso de Berlín pronto convirtió la cuestión macedonia en "la manzana de la discordia constante" entre Serbia, Grecia y Bulgaria. El renacimiento nacional búlgaro en Macedonia no estuvo exento de oposición. Los griegos y los serbios también tenían ambiciones nacionales en la región y creían que podrían promoverse mediante una política de disimilación cultural y lingüística de los eslavos macedonios, que se lograría mediante la propaganda educativa y eclesiástica. No obstante, en la década de 1870 los búlgaros eran claramente el partido nacionalista dominante en Macedonia. Se esperaba ampliamente que los eslavos macedonios continuarían evolucionando como parte integral de la nación búlgara y que, en caso de la desaparición del Imperio otomano, Macedonia sería incluida en un estado sucesor búlgaro. El que estas previsiones resultaran falsas no se debió a ninguna peculiaridad intrínseca de los eslavos macedonios que los diferenciara de los búlgaros, sino a una serie de acontecimientos catastróficos que, a lo largo de un período de setenta años, desviaron el curso de la historia macedonia de su presunta tendencia. [22]

El nacionalismo serbio del siglo XIX consideraba a los serbios como el pueblo elegido para dirigir y unir a todos los eslavos del sur en un solo país, Yugoslavia (el país de los eslavos del sur). [ cita requerida ] La conciencia de las partes periféricas de la nación serbia creció, por lo tanto, los funcionarios y los amplios círculos de la población consideraban a los eslavos de Macedonia como "serbios del sur", a los musulmanes como "serbios islamizados" y a la parte de habla shtokavia de la población croata actual como "serbios católicos". [ cita requerida ] Pero, los intereses básicos de la política estatal serbia estaban dirigidos a la liberación de las regiones otomanas de Bosnia y Herzegovina y Kosovo; mientras que Macedonia y Vojvodina debían ser "liberadas más tarde". [ cita requerida ]

El Congreso de Berlín de 1878, que concedió Bosnia y Herzegovina a la ocupación y administración austrohúngaras mientras nominalmente era otomana, redirigió las ambiciones de Serbia hacia Macedonia y se lanzó una campaña de propaganda en el país y en el extranjero para demostrar el carácter serbio de la región. [ cita requerida ] Un astrónomo e historiador de Trieste , Spiridon Gopčević (también conocido como Leo Brenner), hizo una gran contribución a la causa serbia . [25] Gopčević publicó en 1889 la investigación etnográfica Macedonia y la antigua Serbia , que definía a más de tres cuartas partes de la población macedonia como serbia. [25] La población de Kosovo y el norte de Albania fue identificada como serbia o albanesa de origen serbio (serbios albanizados, llamados "arnautas") y los griegos a lo largo del Aliákmon como griegos de origen serbio (serbios helenizados). [ cita requerida ]

El trabajo de Gopčević fue desarrollado por dos eruditos serbios, el geógrafo Jovan Cvijić y el lingüista Aleksandar Belić . Menos extremistas que Gopčević, Cvijić y Belić afirmaron que solo los eslavos del norte de Macedonia eran serbios, mientras que los del sur de Macedonia eran identificados como "eslavos macedonios", una masa eslava amorfa que no era ni búlgara ni serbia, pero que podría convertirse en búlgara o serbia si los respectivos pueblos gobernaran la región. [26]

A finales del siglo XIX se estableció que la mayoría de la población de Macedonia central y meridional (vilaetos de Monastiri y Tesalónica) era predominantemente de etnia griega , mientras que las partes septentrionales de la región (vilaeto de Skopje) eran predominantemente eslavas. Los judíos y las comunidades otomanas estaban diseminadas por todas partes. Debido a la naturaleza poliétnica de Macedonia, los argumentos que Grecia utilizó para promover su reivindicación de toda la región fueron generalmente de carácter histórico y religioso. Los griegos vincularon sistemáticamente la nacionalidad a la lealtad al Patriarcado de Constantinopla. Los términos "griegos búlgaros", "albanófonos" y "valacófonos" se acuñaron para describir a la población que hablaba eslavo, albanés o valaco ( arrumano ). Los arrumanos también sufrieron presiones para que se disimilaran lingüísticamente a partir del siglo XVIII, cuando el misionero griego Cosmas de Etolia (1714-1779) alentó los esfuerzos de disimilación, enseñando que los arrumanos debían hablar griego porque, como él decía, "es la lengua de nuestra Iglesia" y estableció más de 100 escuelas griegas en el norte y el oeste de Grecia. La ofensiva del clero contra el uso del arrumano no se limitó en absoluto a cuestiones religiosas, sino que fue una herramienta ideada para convencer a los hablantes no griegos de que abandonaran lo que consideraban un idioma "sin valor" y adoptaran el habla griega superior: "Henos aquí, hermanos metsovianos , junto con aquellos que se están engañando a sí mismos con esta sórdida y vil lengua arrumana... perdónenme por llamarla lengua", "discurso repulsivo con una dicción repugnante". [27] [28]

Al igual que la propaganda serbia y búlgara, la griega se concentró inicialmente también en la educación. A principios del siglo XX, las escuelas griegas en Macedonia sumaban 927 con 1.397 profesores y 57.607 alumnos. A partir de la década de 1890, Grecia también comenzó a enviar grupos guerrilleros armados a Macedonia (véase La lucha griega por Macedonia ), especialmente después de la muerte de Pavlos Melas , que lucharon contra los destacamentos de la Organización Revolucionaria Interna de Macedonia (IMRO).

La causa griega predominó en la Macedonia histórica, donde contó con el apoyo de los griegos nativos y de una parte sustancial de las poblaciones eslava y arrumana. El apoyo a los griegos fue mucho menos pronunciado en Macedonia central, y sólo provino de una fracción de los arrumanos y eslavos locales; en las partes septentrionales de la región fue casi inexistente.

La propaganda búlgara volvió a cobrar importancia en la década de 1890, tanto en el ámbito de la educación como en el de las armas. A principios del siglo XX, había 785 escuelas búlgaras en Macedonia, con 1.250 profesores y 39.892 alumnos. El Exarcado Búlgaro tenía jurisdicción sobre siete diócesis (Skopje, Debar , Ohrid , Bitola , Nevrokop , Veles y Strumica ), es decir, toda la región de Vardar y Pirin de Macedonia y parte de Macedonia del Sur. El Comité Revolucionario Búlgaro-Macedonio-Adrianópolis (BMARC), fundado en 1893 como la única organización guerrillera creada por los habitantes locales, desarrolló rápidamente una amplia red de comités y agentes que se convirtió en un "estado dentro del estado" en gran parte de Macedonia. La organización cambió de nombre en varias ocasiones, pasando a llamarse IMRO en 1920. La IMRO luchó no sólo contra las autoridades otomanas, sino también contra los partidos proserbios y progriegos en Macedonia, aterrorizando a la población que los apoyaba.

El fracaso del levantamiento de Ilinden-Preobrazhenie en 1903 significó un segundo debilitamiento de la causa búlgara, que tuvo como consecuencia el cierre de escuelas y una nueva ola de emigración a Bulgaria. La IMRO también se debilitó y el número de grupos guerrilleros serbios y griegos en Macedonia aumentó sustancialmente. El Exarcado perdió las diócesis de Skopje y Debar en manos del Patriarcado serbio en 1902 y 1910, respectivamente. A pesar de esto, la causa búlgara conservó su posición dominante en Macedonia central y septentrional y también fue fuerte en Macedonia meridional.

La independencia de Bulgaria en 1908 tuvo el mismo efecto sobre la idea búlgara en Macedonia que la independencia de Grecia un siglo antes. Las consecuencias fueron el cierre de escuelas, la expulsión de los sacerdotes del exarcado búlgaro y la emigración de la mayoría de la joven intelectualidad macedonia. Esta primera emigración desencadenó un flujo constante de refugiados y emigrantes nacidos en Macedonia hacia Bulgaria. Su número ascendió a unos 100.000 en 1912.

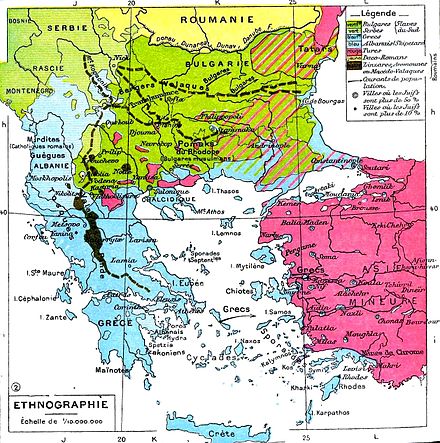

_-_Historische_alte_Landkarte_(Sammlerstück)_von_1924.jpg/440px-Ethnographic_Map_of_the_Balkans_(1912-1918)_-_Historische_alte_Landkarte_(Sammlerstück)_von_1924.jpg)

La ideología étnica macedonia durante la segunda mitad del siglo XIX estaba en sus inicios. Uno de los primeros testimonios conservados es un artículo titulado La cuestión macedonia, de Petko Slaveykov , publicado el 18 de enero de 1871 en el periódico "Macedonia" de Constantinopla . En este artículo, Petko Slaveykov escribe: "Hemos oído muchas veces de los macedonistas que no son búlgaros, sino más bien macedonios, descendientes de los antiguos macedonios". [29] En una carta escrita al exarca búlgaro en febrero de 1874, Petko Slaveykov informa de que el descontento con la situación actual "ha dado lugar entre los patriotas locales a la desastrosa idea de trabajar de forma independiente en el avance de su propio dialecto local y, lo que es más, de su propio liderazgo eclesiástico macedonio independiente". [30]

En 1875, Gjorgjija Pulevski publicó en Belgrado un libro llamado Diccionario de tres lenguas ( Rečnik od tri jezika ). El texto del Rečnik contiene declaraciones programáticas en las que Pulevski aboga por una nación y una lengua macedonias eslavas independientes. [31] Fue la primera obra que reivindicó públicamente que el macedonio era una lengua separada. [32] En 1880 publicó Slognica Rechovska en Sofía como un intento de gramática de la lengua de los eslavos que vivían en Macedonia. Aunque no tenía educación formal, Pulevski publicó varios libros más, incluidos tres diccionarios y una colección de canciones de Macedonia, costumbres y festividades.

La primera manifestación significativa del nacionalismo étnico macedonio fue el libro Sobre los asuntos macedonios ( Za Makedonskite Raboti ) publicado en Sofía en 1903 por Krste Misirkov . En el libro, Misirkov defendía que los eslavos de Macedonia debían tomar un camino separado de los búlgaros y de la lengua búlgara. Misirkov consideraba que el término "macedonio" debería utilizarse para definir a toda la población eslava de Macedonia, borrando la división existente entre griegos, búlgaros y serbios. También se defendía la adopción de una "lengua macedonia" separada como medio de unificación de los macedonios étnicos con la conciencia serbia, búlgara y griega. Sobre los asuntos macedonios fue escrito en el dialecto eslavo del sur hablado en Macedonia central ( Veles - Prilep - Bitola - Ohrid ). Este dialecto fue propuesto por Misirkov como base para la futura lengua y, como dice Misirkov, es un dialecto que se diferencia mucho de todas las demás lenguas vecinas (ya que el dialecto oriental se acercaba demasiado al búlgaro y el del norte demasiado al serbio). Misirkov llama a esta lengua macedonia.

Mientras Misirkov hablaba de la conciencia macedonia y de la lengua macedonia como una meta futura, describió la región más amplia de Macedonia a principios del siglo XX como habitada por búlgaros, griegos, serbios, turcos, albaneses, arrumanos y judíos. En cuanto a los propios macedonios étnicos, Misirkov sostuvo que se habían llamado a sí mismos búlgaros hasta la publicación del libro y que los observadores independientes siempre los llamaron así hasta 1878, cuando las opiniones serbias también comenzaron a obtener reconocimiento. También explicó que la razón de ello era que los eslavos locales eran aliados de los búlgaros en las guerras contra el Imperio bizantino y, debido a eso, los griegos bizantinos los rebautizaron como "búlgaros", de esa manera el término se convirtió en una identificación para los eslavos macedonios en el futuro. Misirkov rechazó más tarde las ideas de Sobre asuntos macedonios y se convirtió en un firme defensor de la causa búlgara. Volvió a la idea de la etnia macedonia de nuevo en la década de 1920. [33]

Otro destacado activista del renacimiento nacional étnico macedonio fue Dimitrija Čupovski, uno de los fundadores y presidente de la Sociedad Literaria Macedonia establecida en San Petersburgo en 1902. Durante el período 1913-14, Čupovski publicó el periódico Makedonski Golos' (Македонскi Голосъ) (que significa voz macedonia ) en el que él y otros miembros de la Colonia Macedonia de Petersburgo propagaban la existencia de un pueblo macedonio separado diferente de los griegos, búlgaros y serbios, y luchaban por popularizar la idea de un estado macedonio independiente.

Durante los años 1920 y 1930, la idea fue promovida por algunos de los miembros izquierdistas de la Organización Federativa Macedonia y más tarde IMRO (Unión), y también por algunos miembros del Partido Comunista de Yugoslavia . En 1934, la Comintern, en coordinación con IMRO (Unión), publicó una resolución sobre la cuestión macedonia en la que, por primera vez, una organización internacional autorizada reconoció la existencia de una nación macedonia separada y de un idioma macedonio . [34]

Las ideas de Misirkov, Pulevski y otros macedonios pasarían en gran medida desapercibidas hasta la Segunda Guerra Mundial , cuando fueron adoptadas por el movimiento de los partisanos macedonios que en 1944 creó la Asamblea Antifascista para la Liberación Nacional de Macedonia y proclamó un estado-nación macedonio de macedonios étnicos . Hicieron del macedonio el idioma oficial del estado macedonio, influyendo aún más en su codificación en 1945. [35] [36] El estado se incorporó más tarde a la República Federal Socialista de Yugoslavia . Los historiadores actuales de Macedonia del Norte afirman que la IMRO se dividió en dos facciones: la primera aspiraba a un estado étnico macedonio y la segunda creía en una Macedonia como parte de una entidad búlgara más amplia. Estas afirmaciones de los historiadores actuales de Macedonia del Norte de que los "autonomistas" en la IMRO defendían una posición macedonia son en gran medida infundadas. La IMRO se consideraba a sí misma –y era considerada por las autoridades otomanas, los grupos guerrilleros griegos, la prensa contemporánea en Europa e incluso por Misirkov– como una organización exclusivamente búlgara. [37]

Los intentos de influencia rumana entre los arrumanos y megleno-rumanos de Macedonia comenzaron a principios del siglo XIX y se basaron principalmente en criterios lingüísticos, así como en la reivindicación de un origen traco-romano común de los rumanos (dacorromanos) y los arrumanos y megleno-rumanos. [ cita requerida ] La primera escuela rumana en Macedonia se estableció en 1864. Finalmente, el número total de escuelas aumentó a 93 [38] a principios del siglo XX. La influencia rumana en el área tuvo cierto éxito en Bitola, Kruševo y en los pueblos arrumanos en los distritos de Bitola y Ohrid. [ cita requerida ] La mayoría de los arrumanos se consideran y se consideraban a sí mismos como un grupo étnico separado, y los rumanos ven a estas naciones como subgrupos de una etnia rumana más amplia. Sin embargo, algunos arrumanos se identifican como parte de la nación rumana. [ cita requerida ] En la actualidad, entre los grupos antirrumanos de arrumanos, particularmente en Grecia, estos actos se denominan "la propaganda rumana". [39]

.jpg/440px-Ethnographische_Karte_von_Makedonien_(1899).jpg)

Las fuentes independientes en Europa entre 1878 y 1918 tendían generalmente a considerar a la población eslava de Macedonia de dos maneras: como búlgaros y como eslavos macedonios. El erudito alemán Gustav Weigand fue uno de los representantes más destacados de la primera tendencia con los libros Etnografía de Macedonia (1924, escrito en 1919) y parcialmente con Los arrumanos (1905). El autor describió todos los grupos étnicos que vivían en Macedonia, mostró empíricamente la estrecha conexión entre los dialectos búlgaros occidentales y los dialectos macedonios y definió a estos últimos como búlgaros. La Comisión Internacional constituida por la Fundación Carnegie para la Paz Internacional en 1913 para investigar las causas y la conducta de las guerras de los Balcanes también se refirió a los eslavos de Macedonia como búlgaros en su informe publicado en 1914. La comisión tenía ocho miembros de Gran Bretaña, Francia, Austria-Hungría , Alemania, Rusia y los Estados Unidos.

El término "eslavos macedonios" fue utilizado por eruditos y publicistas con tres significados generales:

Un ejemplo del uso del primer significado del término fue, por ejemplo, el mapa etnográfico de los pueblos eslavos publicado en 1890 por el erudito ruso Zarjanko, en el que se identificaba a los eslavos de Macedonia como búlgaros. Tras una protesta oficial de Serbia, el mapa se reimprimió posteriormente identificándolos con el nombre políticamente correcto de "eslavos macedonios".

El término fue utilizado en un sentido completamente diferente por el periodista británico Henry Brailsford en Macedonia, sus razas y su futuro (1906). El libro contiene las impresiones de Brailford de una estancia de cinco meses en Macedonia poco después de la represión del Levantamiento de Ilinden y constituye un informe etnográfico. Brailford define el dialecto de Macedonia como no serbio ni búlgaro, aunque más cercano al segundo. Se opina que cualquier nación eslava podría "ganar" Macedonia si utiliza el tacto y los recursos necesarios, pero se afirma que los búlgaros ya lo han hecho. Brailsford utiliza como sinónimos los términos "eslavos macedonios" y "búlgaros", "lengua eslava" y "lengua búlgara". El capítulo sobre los eslavos macedonios/los búlgaros se titula "movimiento búlgaro", a los activistas de IMRO se les llama "macedonios bulgarófilos".

El tercer uso del término se puede observar entre los estudiosos de los países aliados (sobre todo Francia y el Reino Unido) después de 1915 y es aproximadamente igual a la definición dada por Cvijic (véase más arriba).

El nombre de "eslavos macedonios" empezó a aparecer en publicaciones a finales de la década de 1880 y principios de la de 1890. Aunque los éxitos de la propaganda serbia habían demostrado que la población eslava de Macedonia no era sólo búlgara, todavía no conseguían convencer de que esta población fuera, de hecho, serbia. El término "eslavos macedonios", que hasta finales del siglo XIX se utilizó raramente en comparación con el de "búlgaros", sirvió más para ocultar que para definir el carácter nacional de la población de Macedonia. Los académicos recurrían a él normalmente como resultado de la presión serbia o lo utilizaban como término general para los eslavos que habitaban Macedonia independientemente de sus afinidades étnicas. El político serbio Stojan Novaković propuso en 1887 emplear las ideas macedonistas como un medio para contrarrestar la influencia búlgara en Macedonia, promoviendo así los intereses serbios en la región. [41]

Sin embargo, a principios del siglo XX, el continuo esfuerzo de propaganda serbia y especialmente el trabajo de Cvijic habían logrado afianzar firmemente el concepto de los eslavos macedonios en la opinión pública europea, y el nombre se usó casi con tanta frecuencia como "búlgaros". Incluso investigadores pro-búlgaros como H. Henry Brailsford y N. Forbes argumentaron que los eslavos macedonios diferían tanto de los búlgaros como de los serbios. Sin embargo, prácticamente todos los académicos antes de 1915, incluidos los fuertemente pro-serbios como Robert William Seton-Watson , admitieron que las afinidades de la mayoría de ellos residían en la causa búlgara y los búlgaros y los clasificaron como tales. Incluso en 1914, el informe de la Comisión Carnegie afirma que los serbios y los griegos clasificaron a los eslavos de Macedonia como un grupo distinto "eslavo-macedonios" con fines políticos y este término es "un eufemismo político diseñado para ocultar la existencia de búlgaros en Macedonia ". [b]

La entrada de Bulgaria en la Primera Guerra Mundial del lado de las Potencias Centrales significó un cambio drástico en la forma en que la opinión pública europea veía a la población eslava de Macedonia. Para las Potencias Centrales, los eslavos de Macedonia se convirtieron en nada más que búlgaros, mientras que para los Aliados se convirtieron en cualquier cosa menos búlgaros. La victoria final de los Aliados en 1918 condujo a la victoria de la visión de la población eslava de Macedonia como eslavos macedonios, una masa eslava amorfa sin una conciencia nacional desarrollada. [ cita requerida ]

Durante la década de 1920, el Comintern desarrolló una nueva política para los Balcanes, sobre la colaboración entre los comunistas y el movimiento macedonio, y la creación de un movimiento macedonio unido. La idea de una nueva organización unificada fue apoyada por la Unión Soviética , que vio una oportunidad de utilizar este movimiento revolucionario bien desarrollado para difundir la revolución en los Balcanes y desestabilizar las monarquías balcánicas. En el llamado Manifiesto de Mayo del 6 de mayo de 1924 , por primera vez se presentaron los objetivos del movimiento de liberación eslavo macedonio unificado: independencia y unificación de la Macedonia dividida, lucha contra todas las monarquías balcánicas vecinas, formación de una Federación Comunista Balcánica y cooperación con la Unión Soviética . [ cita requerida ]

Más tarde, la Comintern publicó una resolución sobre el reconocimiento de la etnia macedonia . El texto de este documento fue preparado en el período del 20 de diciembre de 1933 al 7 de enero de 1934 por el Secretariado de los Balcanes de la Comintern. Fue aceptado por el Secretariado Político en Moscú el 11 de enero de 1934 y aprobado por el Comité Ejecutivo de la Comintern. La resolución fue publicada por primera vez en el número de abril de Makedonsko Delo bajo el título "La situación en Macedonia y las tareas de la IMRO (Unión) ".

Lo que impedía definir correctamente la nacionalidad de la población eslava de Macedonia era la aparente ligereza con la que esta población la consideraba. La existencia de una conciencia nacional macedonia separada antes de los años 1940 es discutida. [42] [43] Esta confusión es ilustrada por Robert Newman en 1935, quien relata haber descubierto en un pueblo de Vardar Macedonia [c] a dos hermanos, uno que se consideraba serbio y el otro búlgaro. En otro pueblo conoció a un hombre que había sido "campesino macedonio toda su vida", pero al que se le había llamado de forma variada turco, serbio y búlgaro. [44] Sin embargo, en ese período prevalecían sentimientos antiserbios y probúlgaros entre la población local. [45]

En Macedonia, a principios del siglo XX, la nacionalidad era una cuestión de convicciones políticas y de beneficios económicos, de lo que se consideraba políticamente correcto en un momento determinado y de qué grupo guerrillero armado había sido el último en visitar el hogar del encuestado. El proceso de helenización de finales del siglo XVIII y principios del XIX afectó sólo a un estrato limitado de la población, el resurgimiento búlgaro de mediados del siglo XIX fue demasiado breve para formar una conciencia búlgara sólida y los beneficios económicos que ofrecía la propaganda serbia eran demasiado tentadores para rechazarlos. No era raro que pueblos enteros cambiaran su nacionalidad de griega a búlgara y luego a serbia en pocos años o que se convirtieran en búlgaros en presencia de un agente comercial búlgaro y en serbios en presencia de un cónsul serbio. En varias ocasiones, se informó de que los campesinos habían respondido afirmativamente cuando se les preguntaba si eran búlgaros y de nuevo afirmativamente cuando se les preguntaba si eran serbios. Aunque esto ciertamente no puede ser válido para toda la población, muchos diplomáticos y viajeros rusos y occidentales definieron a los macedonios como carentes de una conciencia nacional "adecuada".

La base de los censos otomanos era el sistema millet . Las personas eran clasificadas en categorías étnicas según su afiliación religiosa. Así, todos los musulmanes sunitas eran clasificados como turcos, todos los miembros de la Iglesia Ortodoxa Griega como griegos, mientras que el resto se dividía entre las iglesias ortodoxa búlgara y serbia. [46] Todos los censos concluyeron que la provincia es de mayoría cristiana, entre los cuales predominan los búlgaros. [47]

Censo otomano de 1882 en Macedonia: [47]

Censo de 1895: [47]

Encuesta especial realizada en 1904 por Hilmi Pasha de los tres vilayatos macedonios de Selanik , Manastir y Kosovo [47] (648 mil seguidores del Patriarcado Ecuménico y 557 mil fieles del Exarcado Búlgaro , pero otros 250 mil del primero) habían sido identificados como hablantes de búlgaro. [48] [49] [50] [51] [52] La encuesta también se extiende a partes de los tres vilayatos que no son parte de la región de Macedonia, es decir, Sandžak , Kosovo , partes del este de Albania y Epiro .

Censo 1906: [47]

La edición de 1911 de la Enciclopedia Británica proporcionó las siguientes estimaciones estadísticas sobre la población de Macedonia: [14]

En total, 1.300.000 cristianos (casi exclusivamente ortodoxos), 800.000 musulmanes, 75.000 judíos, una población total de unos 2.200.000 habitantes para toda Macedonia.

Hay que tener en cuenta que una parte de la población de habla eslava del sur de Macedonia se consideraba étnicamente griega y un porcentaje menor, sobre todo en el norte de Macedonia, serbia. Todos los musulmanes (excepto los albaneses) tendían a considerarse y eran considerados turcos, independientemente de su lengua materna.

Los siguientes datos reflejan la población de la región más amplia de Macedonia tal como fue definida por los serbios y los búlgaros (Egeo, Vardar y Pirin), que corresponde aproximadamente a Manastir Vilayet , Salónica Vilayet y Kosovo Vilayet de la Macedonia otomana, que era significativamente más grande que la región tradicional conocida por los griegos.

Tras los grandes intercambios de población de la década de 1920, 380.000 turcos abandonaron Grecia y 538.253 griegos llegaron a Macedonia desde Asia Menor. Tras la firma del Tratado de Neuilly-sur-Seine en 1919, Grecia y Bulgaria acordaron un intercambio de población para la minoría búlgara restante en Macedonia. Ese mismo año, unos 66.000 búlgaros y otros eslavohablantes se marcharon a Bulgaria y Serbia, mientras que 58.709 griegos entraron en Grecia desde Bulgaria.

Según un informe de la Liga de Naciones de 1912, la composición nacional de la Macedonia griega en 1913 era de 42,6% griegos (513.000), 39,4% musulmanes (475.000; incluyendo Vallahades ), 9,9% búlgaros (119.000) y 8,1% otros (98.000). [53] [54] Según una encuesta de Carnegie basada en el mapa etnográfico de Macedonia del Sur, que representa la distribución étnica en vísperas de la guerra de los Balcanes de 1912, publicado en 1913 por el Sr. J. Ivanov, profesor de la Universidad de Sofía. [55] El número total de personas pertenecientes a las diversas nacionalidades en un territorio un poco más grande que la porción de la misma región cedida a los griegos por los turcos era de 1.042.029 habitantes, de los cuales 329.371 búlgaros, 314.854 turcos, 236.755 griegos, 68.206 judíos, 44.414 valacos, 25.302 gitanos, 15.108 albaneses y 8.019 misceláneos. [55]

Según un informe posterior de la Liga de Naciones, en el censo de 1928 la población estaba compuesta por 1.341.000 griegos (88,8%), 77.000 búlgaros (5%), 2.000 turcos y 91.000 otros, [56] [57] pero según fuentes de archivo griegas el número total de hablantes de eslavo puede haber sido de 200.000. [58]

The Balkan Wars (1912–1913) and World War I (1914–1918) left the region of Macedonia divided among Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Albania and resulted in significant changes in its ethnic composition. 51% of the region's territory went to Greece, 38% to Serbia and 10% to Bulgaria. At least several hundred thousand left their homes,[59] while the rest were also subjected to assimilation as all "liberators" after the Balkan War wanted to assimilate as many inhabitants as possible and colonize with settlers from their respective nation.[57] The Greeks become the largest population in the region. The formerly leading Muslim and Bulgarian communities were reduced either by deportation (through population exchange) or by change of identity.

The Slavic population was viewed as Slavophone Greeks and prepared to be reeducated in Greek. Any vestiges of Bulgarian and Slavic Macedonia in Greece have been eliminated from the Balkan Wars, continuing to the present.[60] The Greeks detested the Bulgarians (Slavs of Macedonia), considering them less than human "bears, practising systematic and inhumane methods of extermination and assimilation.[60] The use of Bulgarian language had been prohibited, for which the persecution by the police peaked, while during the regime of Metaxas a vigorous assimilation campaign was launched.[58] The civilians have been persecuted solely for identifying as Bulgarian with the slogans "If you want to be free, be Greek" "We shall cut your tongues to teach you to speak Greek." "become Greeks again, that being the condition of a peaceful life.""Are you Christians or Bulgarians?" "The voice of Alexander the Great calls to you from the tomb; do you not hear it? You sleep on and go on calling yourselves Bulgarians!" "Wast thou born at Sofia; there are no Bulgarians in Macedonia; the whole population is Greek." "He who goes to live in Bulgaria," was the reply to the protests, "is Bulgarian. No more Bulgarians in Greek Macedonia."[59][61] The remaining Bulgarians threatened by use of force were made to become Greeks and to sign a declaration stating that they had been Greek since ancient times, but by the influence of komitadji they became Bulgarians only fifteen years ago, but nevertheless there was no real change in consciousness.[59][61] In many villages people were put to prison and then were released after having proclaimed themselves Greeks.[62] The Slavic dialect was considered as being of lowest intelligence with the assumptions that it "consists" only a thousand words of vocabulary.[63] There are official records showing that children professing Bulgarian identity were also murdered for declining to profess Greek identity.[61]

After the Treaty of Bucharest, some 51% of the modern region that was known as Macedonia was won by the Greek state (also known as Aegean or Greek Macedonia). This was the only part of Macedonia that Greece was directly interested in. Greeks regarded this land as the only true region of Macedonia as it geographically corresponded to ancient Macedon and contained an ethnically Greek majority of population. Bulgarian and other non-Greek schools in southern (Greek) Macedonia were closed and Bulgarian teachers and priests were deported as early as the First Balkan War simultaneous to deportation of Greeks from Bulgaria. The bulk of the Slavic population of southeastern Macedonia fled to Bulgaria during the Second Balkan War or was resettled there in the 1920s by virtue of a population exchange agreement. The Slavic minority in Greek Macedonia, who were referred to by the Greek authorities as "Slavomacedonians", "Slavophone Greeks" and "Bulgarisants", were subjected to a gradual assimilation by the Greek majority. Their numbers were reduced by a large-scale emigration to North America in the 1920s and the 1930s and to Eastern Europe and Yugoslavia following the Greek Civil War (1944–1949). At the same time a number of Macedonian Greeks from Monastiri (modern Bitola) entered Greece.

The 1923 Compulsory population exchange between Greece and Turkey led to a radical change in the ethnic composition of Greek Macedonia. Some 380,000 Turks and other Muslims left the region and were replaced by 538,253 Greeks from Asia Minor and Eastern Thrace, including Pontic Greeks from northeastern Anatolia and Caucasus Greeks from the South Caucasus.

Greece was attacked and occupied by Nazi-led Axis during World War II. By the beginning of 1941 the whole of Greece was under a tripartite German, Italian and Bulgarian occupation. The Bulgarians were permitted to occupy western Thrace and parts of Greek Macedonia, where they persecuted and committed massacres and other atrocities against the Greek population. The once thriving Jewish community of Thessaloniki was decimated by the Nazis, who deported 60,000 of the city's Jews to the German death camps in Germany and German-occupied Poland. Large Jewish populations in the Bulgarian occupied zone were deported by the Bulgarian army and had an equal death rate to the German zone.

The Bulgarian Army occupied the whole of Eastern Macedonia and Western Thrace, where it was greeted from a part of a Slav-speakers as liberators.[64] Unlike Germany and Italy, Bulgaria officially annexed the occupied territories, which had long been a target of Bulgarian irridentism.[65] A massive campaign of "Bulgarisation" was launched, which saw all Greek officials deported. This campaign was successful especially in Eastern and later in Central Macedonia, when Bulgarians entered the area in 1943. All Slav-speakers there were regarded as Bulgarians. However it was not so effective in German-occupied Western Macedonia. A ban was placed on the use of the Greek language, the names of towns and places changed to the forms traditional in Bulgarian.

In addition, the Bulgarian government tried to alter the ethnic composition of the region, by expropriating land and houses from Greeks in favour of Bulgarian settlers. The same year, the German High Command approved the foundation of a Bulgarian military club in Thessaloníki. The Bulgarians organized supplying of food and provisions for the Slavic population in Central and Western Macedonia, aiming to gain the local population that was in the German and Italian occupied zones. The Bulgarian clubs soon started to gain support among parts of the population. Many Communist political prisoners were released with the intercession of Bulgarian Club in Thessaloniki, which had made representations to the German occupation authorities. They all declared Bulgarian ethnicity.[citation needed][66] In 1942, the Bulgarian club asked assistance from the High command in organizing armed units among the Slavic-speaking population in northern Greece. For this purpose, the Bulgarian army, under the approval of the German forces in the Balkans sent a handful of officers from the Bulgarian Army, to the zones occupied by the Italian and German troops to be attached to the German occupying forces as "liaison officers". All the Bulgarian officers brought into service were locally born Macedonians who had immigrated to Bulgaria with their families during the 1920s and 1930s as part of the Greek-Bulgarian Treaty of Neuilly which saw 90,000 Bulgarians migrating to Bulgaria from Greece.

With the help of Bulgarian officers several pro-Bulgarian and anti-Greek armed detachments (Ohrana) were organized in the Kastoria, Florina and Edessa districts of occupied Greek Macedonia in 1943. These were led by Bulgarian officers originally from Greek Macedonia; Andon Kalchev and Georgi Dimchev.[67] Ohrana (meaning Defense) was an autonomist pro-Bulgarian organization fighting for unification with Greater Bulgaria. Uhrana was supported from IMRO leader Ivan Mihaylov too. It was apparent that Mihailov had broader plans which envisaged the creation of a Macedonian state under a German control. It was also anticipated that the IMRO volunteers would form the core of the armed forces of a future Independent Macedonia in addition to providing administration and education in the Florina, Kastoria and Edessa districts. In the summer of 1944, Ohrana constituted some 12,000 fighters and volunteers from Bulgaria charged with protection of the local population. During 1944, whole Slavophone villages were armed by the occupation authorities and developed into the most formidable enemy of the Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS). Ohrana was dissolved in late 1944 after the German and Bulgarian withdrawal from Greece and Josip Broz Tito's Partisans movement hardly concealed its intention of expanding.[68] After World War II, many former "Ohranists" were convicted of a military crimes as collaborationists. It was from this period, after Bulgaria's conversion to communism, that some Slav-speakers in Greece who had referred to themselves as "Bulgarians" increasingly began to identify as "Macedonians".[69]

Following the defeat of the Axis powers and the evacuation of the Nazi occupation forces many members of the Ohrana joined the SNOF where they could still pursue their goal of secession. The advance of the Red Army into Bulgaria in September 1944, the withdrawal of the German armed forces from Greece in October, meant that the Bulgarian Army had to withdraw from Greek Macedonia and Thrace. A large proportion of Bulgarians and Slavic speakers emigrated there. In 1944 the declarations of Bulgarian nationality were estimated by the Greek authorities, on the basis of monthly returns, to have reached 16,000 in the districts of German-occupied Greek Macedonia,[71] but according to British sources, declarations of Bulgarian nationality throughout Western Macedonia reached 23,000.[72]

By 1945 World War II had ended and Greece was in open civil war. It has been estimated that after the end of World War II over 40,000 people fled from Greece to Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. To an extent the collaboration of the peasants with the Germans, Italians, Bulgarians or the Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS) was determined by the geopolitical position of each village. Depending upon whether their village was vulnerable to attack by the Greek communist guerrillas or the occupation forces, the peasants would opt to support the side in relation to which they were most vulnerable. In both cases, the attempt was to promise "freedom" (autonomy or independence) to the formerly persecuted Slavic minority as a means of gaining its support.[73]

The National Liberation Front (NOF) was organized by the political and military groups of the Slavic minority in Greece, active from 1945 to 1949. The interbellum was the time when part of them came to the conclusion that they are Macedonians. Greek hostility to the Slavic minority produced tensions that rose to separatism. After the recognition in 1934 from the Comintern of the Macedonian ethnicity, the Greek communists have also recognized Macedonian national identity. Soon after the first "free territories" were created it was decided that ethnic Macedonian schools would open in the area controlled by the DSE.[12] Books written in the ethnic Macedonian language were published, while ethnic Macedonians theatres and cultural organizations operated. Also within the NOF, a female organization, the Women's Antifascist Front (AFZH), and a youth organization, the National Liberation Front of Youth (ONOM), were formed.[13]

The creation of the ethnic Macedonian cultural institutions in the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE)-held territory, newspapers and books published by NOF, public speeches and the schools opened, helped the consolidation of the ethnic Macedonian conscience and identity among the population. According to information announced by Paskal Mitrovski on the I plenum of NOF in August 1948 – about 85% of the Slavic-speaking population in Greek Macedonia has ethnic Macedonian self-identity. The language that was thought in the schools was the official language of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia. About 20,000 young ethnic Macedonians learned to read and write using that language, and learned their own history.

From 1946 until the end of the Civil War in 1949, the NOF was loyal to Greece and was fighting for minimal human rights within the borders of a Greek republic. But in order to mobilize more ethnic Macedonians into the DSE it was declared on 31 January 1949 at the 5th Meeting of the KKE Central Committee that when the DSE took power in Greece there would be an independent Macedonian state, united in its geographical borders.[14] This new line of the KKE affected the mobilisation rate of ethnic Macedonians (which even earlier was considerably high), but did not manage, ultimately, to change the course of the war.

The government forces destroyed every village that was on their way, and expelled the civilian population.[citation needed] Leaving as a result of force or on their own accord (in order to escape oppression and retaliation), 50,000 people left Greece together with the retreating DSE forces. All of them were sent to Eastern Bloc countries.[15][16] It was not until the 1970s that some of them were allowed to come to the Socialist Republic of Macedonia. In the 1980s, the Greek parliament adopted the law of national reconciliation which allowed DSE members "of Greek origin" to repatriate to Greece, where they were given land. Ethnic Macedonian DSE remembers remained excluded from the terms of this legislation.[17]

On August 20, 2003, the Rainbow Party hosted a reception for the "child refugees", ethnic Macedonian children who fled their homes during the Greek Civil War who were permitted to enter Greece for a maximum of 20 days. Now elderly, this was the first time many of them saw their birthplaces and families in some 55 years. The reception included relatives of the refugees who are living in Greece and are members of Rainbow Party. However, many were refused entry by Greek border authorities because their passports listed the former names of their places of birth.

The present number of the "Slavophones" in Greece has been subject to much speculation with varying numbers. As Greece does not hold census based on self-determination and mother tongue, no official data is available. It should be noted, however, that the official Macedonian Slav party in Greece receives at an average only 1000 votes. For more information about the region and its population see Slavic speakers of Greek Macedonia.

After the Balkan Wars (1912–1913) the Slavs in Vardar Macedonia were regarded as southern Serbs and the language they spoke a southern Serbian dialect. Serbian rule ensured that all ethnic Macedonian symbolism and identity were henceforth proscribed, and only standard Serbian was permitted to be spoken by the locals of Macedonia. In addition, Serbia did not refer to its southern land as Macedonia, a legacy which remains in place today among some Serbian nationalists (e.g. the Serbian Radical Party). Despite their attempts of forceful assimilation, Serb colonists in Vardar Macedonia numbered only 100,000 by 1942, so there was not that colonization and expulsion as in Greek Macedonia.[57] Ethnic cleansing was unlikely in Serbia, Bulgarians were given to sign declaration for being Serbs since ancient times, those who refused to sign faced assimilation through terror, while Muslims faced similar discrimination.[59] However, in 1913 Bulgarian revolts broke out in Tikvesh, Negotino, Kavadarci, Vartash, Ohrid, Debar and Struga, and more than 260 villages were burnt down.[57] Serbian officials are documented to have buried alive three Bulgarian civilians from Pehčevo then.[74] Bulgarians were forced to sign a petition "Declare yourself a Serb or die."[60] 90,000 Serbian troops were deployed in Macedonia to keep down resistance from Serbianization, Serbian colonists were unsuccessfully encouraged to immigrate with the slogan "for the good of Serbs", but the Albanians and Turks to emigrate.[63] In the next centuries, a sense of a distinct Macedonian nation emerged partly as a result of the resistance of IMRO, despite it was split into one Macedonist and one pro-Bulgarian wing.[63] In 1918 the use of Bulgarian and Macedonian language was prohibited in Serbian Macedonia.[63]

The Bulgarian, Greek and Romanian schools were closed, the Bulgarian priests and all non-Serbian teachers were expelled. Bulgarian surname endings '-ov/-ev' were replaced with the typically Serbian ending '-ich' and the population which considered itself Bulgarian was heavily persecuted. The policy of Serbianization in the 1920s and 1930s clashed with popular pro-Bulgarian sentiment stirred by IMRO detachments infiltrating from Bulgaria, whereas local communists favoured the path of self-determination suggested by the Yugoslav Communist Party in the 1924 May Manifesto.

_1932.jpg/440px-Mitteleuropa_(ethnische_Karte)_1932.jpg)

In 1925, D. J. Footman, the British vice consul at Skopje, addressed a lengthy report for the Foreign Office. He wrote that "the majority of the inhabitants of Southern Serbia are Orthodox Christian Macedonians, ethnologically more akin to the Bulgarians than to the Serbs." He acknowledged that the Macedonians were better disposed toward Bulgaria because, Bulgarian education system in Macedonia in the time of the Turks, was widespread and effective; and because Macedonians at the time perceived Bulgarian culture and prestige to be higher than those of its neighbors. Moreover, large numbers of Macedonians educated in Bulgarian schools had sought refuge in Bulgaria before and especially after the partitions of 1913. "There is therefore now a large Macedonian element in Bulgaria, continued represented in all Government Departments and occupying high positions in the army and in the civil service...." He characterized this element as "Serbophobe, [it] mostly desires the incorporation of Macedonia in Bulgaria, and generally supports the IMRO." However, he also pointed to the existence of the tendency to seek an independent Macedonia with Salonica as its capital. "This movement also had adherents among the Macedonian colony in Bulgaria."[75]

Bulgarian troops were welcomed as liberators in 1941 but mistakes of the Bulgarian administration made a growing number of people resent their presence by 1944. It must also to be noted that the Bulgarian army during the annexation of the region, was partially recruited from the local population, which formed as much as 40%-60% of the soldiers in certain battalions.[76] Some recent data has announced that even the National Liberation War of Macedonia has resembled ethno-political motivated civil war.[77][78] After the war the region received the status of a constituent republic within Yugoslavia and in 1945 a separate, Macedonian language was codified. The population was declared Macedonian, a nationality different from both Serbs and Bulgarians. The decision was politically motivated and aimed at weakening the position of Serbia within Yugoslavia and of Bulgaria with regard to Yugoslavia. Surnames were again changed to include the ending '-ski', which was to emphasise the unique nature of the ethnic Macedonian population.

From the start of the new Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), accusations surfaced that new authorities in Macedonia were involved in retribution against people who did not support the formation of the new Yugoslav Macedonian republic. The numbers of dead "counter-revolutionaries" due to organized killings, however is unclear. Besides, many people went throughout the Labor camp of Goli Otok in the middle 1940s.[79] This chapter of the partisan's history was a taboo subject for conversation in the SFRY until the late 1980s, and as a result, decades of official silence created a reaction in the form of numerous data manipulations for nationalist communist propaganda purposes.[80]At the times of Croatian ruling-class of Yugoslavia, Vardar Banovina Province was turned into autonomous Macedonia with a majority of the population declaring on census as ethnic Macedonians, and a Macedonian language as the official, recognized as distinct from Serbo-Croatian. The capital was placed in a Torlakian-speaking region. Persecution of Bulgarian identity by the state continued, along with propaganda.

After the creation of Macedonian Republic the Presidium of ASNOM which was the highest political organ in Macedonia made several statements and actions that were de facto boycotting the decisions of AVNOJ. Instead of obeying the order of Tito's General Headquarters to send the main forces of the NOV of Macedonia to participate in the fighting in the Srem area for the final liberation of Yugoslavia, the cadre close to President Metodija Andonov – Cento gave serious thoughts whether it is better to order the preparation for an advance of the 100.000 armed men under his command toward northern Greece in order to "unify the Macedonian people" into one country.[81] Officers loyal to Chento's ideas made a mutiny in the garrison stationed on Skopje's fortress, but the mutiny was suppressed by armed intervention. A dozen officers were shot on place, others sentenced to life imprisonment. Also Chento and his close associates were trying to minimize the ties with Yugoslavia as far as possible and were constantly mentioning the unification of the Macedonian people into one state, which was against the decisions of AVNOJ.[82] Chento was even talking about the possibility to create an independent Macedonia backed by the US. The Yugoslav secret police made a decisive action and managed to arrest Metodija Andonov - Chento and his closest men and prevent his policies. Chento's place was taken by Lazar Kolishevski, who started fully implementing the pro-Yugoslav line.

Later the authorities organised frequent purges and trials of Macedonian people charged with autonomist deviation. Many of the former IMRO (United) government officials, were purged from their positions then isolated, arrested, imprisoned or executed on various (in many cases fabricated) charges including: pro-Bulgarian leanings, demands for greater or complete independence of Yugoslav Macedonia, forming of conspirative political groups or organisations, demands for greater democracy, etc. People as Panko Brashnarov, Pavel Shatev, Dimitar Vlahov and Venko Markovski were quickly ousted from the new government, and some of them assassinated. On the other hand, former IMRO-members, followers of Ivan Mihailov, were also persecuted by the Belgrade-controlled authorities on accusations of collaboration with the Bulgarian occupation. Metodi Shatorov's supporters in Vardar Macedonia, called Sharlisti, were systematically exterminated by the Yugoslav Communist Party (YCP) in the autumn of 1944, and repressed for their anti-Yugoslav and pro-Bulgarian political positions.

The encouragement and evolution of the culture of the Republic of Macedonia has had a far greater and more permanent impact on Macedonian nationalism than has any other aspect of Yugoslav policy. While development of national music, films and the graphic arts has been encouraged in the Republic of Macedonia, the greatest cultural effect has come from the codification of the Macedonian language and literature, the new Macedonian national interpretation of history and the establishment of a Macedonian Orthodox Church in 1967 by Central Committee of the Communist Party of Macedonia.[83]

The Bulgarian population in Pirin Macedonia remained Bulgarian after 1913. The "Macedonian question" became especially prominent after the Balkan wars in 1912–1913, followed from the withdraw of the Ottoman Empire and the subsequent division of the region of Macedonia between Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia. The Slav – speakers in Macedonia tended to be Christian peasants, but the majority of them were under the influence of the Bulgarian Exarchate and its education system, thus considered themselves as Bulgarians.[14][84][85] Moreover, Bulgarians in Bulgaria believed that most of the population of Macedonia was Bulgarian.[86] Before the Balkan Wars the regional Macedonian dialects were treated as Bulgarian and the Exarchate school system taught the locals in Bulgarian.[87] Following the Balkan wars the Bulgarian Exarchate activity in most of the region was discontinued. After World War I, the territory of the present-day North Macedonia came under the direct rule of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and was sometimes termed "Southern Serbia". Together with a portion of today's Serbia, it belonged officially to the newly formed Vardar Banovina. An intense program of Serbianization was implemented during the 1920s and 1930s when Belgrade enforced a Serbian cultural assimilation process on the region.[88] Between the two world wars in Vardar Banovina, the regional Macedonian dialects were declared as Serbian and the Serbian language was introduced in the schools and administration as official language. There was implemented a governmental policy of assassinations and assimilation. The Serbian administration in Vardar Banovina felt insecure and that provoked its brutal reprisals on the local peasant population.[89][90][91]Greece, like all other Balkan states, adopted restrictive policies towards its minorities, namely towards its Slavic population in its northern regions, due to its experiences with Bulgaria's wars, including the Second Balkan War, and the Bulgarian inclination of sections of its Slavic minority.

IMRO was a "state within the state" in the region in the 1920s using it to launch attacks in the Serbian and Greek parts of Macedonia. By that time IMRO had become a right-wing Bulgarian ultranationalist organization. According to IMRO statistics during the 1920s in the region of Yugoslav (Vardar) Macedonia operated 53 chetas (armed bands), 36 of which penetrated from Bulgaria, 12 were local and 5 entered from Albania. In the region of Greek (Aegean) Macedonia 24 chetas and 10 local reconnaissance detachments were active. Thousands local of Slavophone Macedonians were repressed by the Yugoslav and Greek authorities on suspicions of contacts with the revolutionary movement. The population in Pirin Macedonia was organized in a mass people's home guard. This militia was the only force, which resisted to the Greek army when general Pangalos launched a military campaign against Petrich District in 1925, speculatively called the War of the Stray Dog. IMRO's constant fratricidal killings and assassinations abroad provoked some within Bulgarian military after the coup of 19 May 1934 to take control and break the power of the organization. Meanwhile, the left-wing later did form the new organisation based on the principles of independence and unification of partitioned Macedonia. The new organisation which was an opponent to Ivan Mihailov's IMRO was called IMRO (United). It was founded in 1925 in Vienna. However, it did not have real popular support and remained active until 1936 and was funded by and closely linked to the Comintern and the Balkan Communist Federation. In 1934 the Comintern adopted resolution about the recognition of Macedonian nation and confirmed the project of the Balkan Communist Federation about creation of Balkan Federative Republic, including Macedonia.