Facebook es un servicio de redes sociales y medios sociales propiedad del conglomerado tecnológico estadounidense Meta . Creado en 2004 por Mark Zuckerberg con otros cuatro estudiantes y compañeros de habitación de Harvard College Eduardo Saverin , Andrew McCollum , Dustin Moskovitz y Chris Hughes , su nombre deriva de los directorios de Facebook que a menudo se les dan a los estudiantes universitarios estadounidenses. La membresía inicialmente se limitó a los estudiantes de Harvard, expandiéndose gradualmente a otras universidades de América del Norte. Desde 2006, Facebook permite que todos se registren a partir de los 13 años, excepto en el caso de un puñado de naciones, donde el límite de edad es de 14 años. [6] A diciembre de 2022 , Facebook afirmó tener casi 3 mil millones de usuarios activos mensuales. [7] A octubre de 2023, Facebook se clasificó como el tercer sitio web más visitado del mundo , con un 22,56% de su tráfico proveniente de los Estados Unidos. [8] [9] Fue la aplicación móvil más descargada de la década de 2010. [10][update]

Se puede acceder a Facebook desde dispositivos con conexión a Internet , como ordenadores personales , tabletas y teléfonos inteligentes . Tras registrarse, los usuarios pueden crear un perfil que revele información sobre sí mismos. Pueden publicar texto, fotos y multimedia que se comparten con cualquier otro usuario que haya aceptado ser su amigo o, con diferentes configuraciones de privacidad , de forma pública. Los usuarios también pueden comunicarse directamente entre sí con Messenger , unirse a grupos de intereses comunes y recibir notificaciones sobre las actividades de sus amigos de Facebook y las páginas que siguen.

Facebook, objeto de numerosas controversias , ha sido criticado a menudo por cuestiones como la privacidad del usuario (como con el escándalo de datos de Cambridge Analytica ), la manipulación política (como con las elecciones estadounidenses de 2016 ) y la vigilancia masiva. [11] Facebook también ha sido objeto de críticas por efectos psicológicos como la adicción y la baja autoestima , y varias controversias sobre contenido como noticias falsas , teorías de conspiración , violación de derechos de autor y discurso de odio . [12] Los comentaristas han acusado a Facebook de facilitar voluntariamente la difusión de dicho contenido, así como de exagerar su número de usuarios para atraer a los anunciantes. [13]

Zuckerberg creó un sitio web llamado "Facemash" en 2003 mientras asistía a la Universidad de Harvard . El sitio era comparable a Hot or Not y usaba "fotos compiladas de los libros de Facebook en línea de nueve casas, colocando dos al lado de la otra a la vez y pidiendo a los usuarios que eligieran a la persona 'más sexy'". [15] Facemash atrajo a 450 visitantes y 22.000 vistas de fotos en sus primeras cuatro horas. [16] El sitio fue enviado a varias listas de correo grupales del campus , pero fue cerrado unos días después por la administración de Harvard. Zuckerberg se enfrentó a la expulsión y fue acusado de violar la seguridad, violar los derechos de autor y violar la privacidad individual. Finalmente, los cargos fueron retirados. [15] Zuckerberg amplió este proyecto ese semestre al crear una herramienta de estudio social. Subió imágenes de arte, cada una acompañada de una sección de comentarios, a un sitio web que compartió con sus compañeros de clase. [17]

Un " facebook " es un directorio de estudiantes que incluye fotos e información personal. [16] En 2003, Harvard solo tenía una versión en papel [18] junto con directorios privados en línea. [15] [19] Zuckerberg le dijo a The Harvard Crimson : "Todo el mundo ha estado hablando mucho sobre un facebook universal dentro de Harvard... Creo que es una tontería que la Universidad tarde un par de años en hacerlo. Puedo hacerlo mejor que ellos y puedo hacerlo en una semana". [19] En enero de 2004, Zuckerberg codificó un nuevo sitio web, conocido como "TheFacebook", inspirado en un editorial de Crimson sobre Facemash, que decía: "Está claro que la tecnología necesaria para crear un sitio web centralizado está fácilmente disponible... los beneficios son muchos". Zuckerberg se reunió con el estudiante de Harvard Eduardo Saverin , y cada uno de ellos acordó invertir $1,000 ($1,613 en dólares de 2023 [20] ) en el sitio. [21] El 4 de febrero de 2004, Zuckerberg lanzó "TheFacebook", originalmente ubicado en thefacebook.com. [22]

Seis días después del lanzamiento del sitio, los estudiantes de último año de Harvard Cameron Winklevoss , Tyler Winklevoss y Divya Narendra acusaron a Zuckerberg de engañarlos intencionalmente haciéndoles creer que los ayudaría a construir una red social llamada HarvardConnection.com . Afirmaron que, en cambio, estaba usando sus ideas para construir un producto competidor. [23] Los tres se quejaron ante el Crimson y el periódico inició una investigación. Más tarde demandaron a Zuckerberg, llegando a un acuerdo en 2008 [24] por 1,2 millones de acciones (por un valor de 300 millones de dólares en la IPO de Facebook , o 398 millones de dólares en dólares de 2023 [20] ). [25]

La membresía estaba inicialmente restringida a los estudiantes de Harvard College . En un mes, más de la mitad de los estudiantes universitarios se habían registrado. [26] Dustin Moskovitz , Andrew McCollum y Chris Hughes se unieron a Zuckerberg para ayudar a administrar el crecimiento del sitio web. [27] En marzo de 2004, Facebook se expandió a Columbia , Stanford y Yale . [28] Luego estuvo disponible para todas las universidades de la Ivy League , la Universidad de Boston , la Universidad de Nueva York , el MIT y, sucesivamente, la mayoría de las universidades de los Estados Unidos y Canadá . [29] [30]

A mediados de 2004, el cofundador y empresario de Napster, Sean Parker —un asesor informal de Zuckerberg— se convirtió en presidente de la compañía. [31] En junio de 2004, la compañía se mudó a Palo Alto, California . [32] Sean Parker llamó a Reid Hoffman para financiar Facebook. Sin embargo, Reid Hoffman estaba demasiado ocupado lanzando LinkedIn , por lo que creó Facebook con el cofundador de PayPal, Peter Thiel , quien le dio a Facebook su primera inversión más tarde ese mes. [33] [34] En 2005, la compañía eliminó "the" de su nombre después de comprar el nombre de dominio Facebook.com por US$ 200.000 (US$ 312.012 en dólares de 2023 [20] ). [35] El dominio había pertenecido a AboutFace Corporation.

En mayo de 2005, Accel Partners invirtió 12,7 millones de dólares (19,8 millones de dólares en 2023 [20] ) en Facebook, y Jim Breyer [36] añadió 1 millón de dólares (1,56 millones de dólares en 2023 [20] ) de su propio dinero. En septiembre de 2005 se lanzó una versión del sitio para escuelas secundarias. [37] La elegibilidad se amplió para incluir a empleados de varias empresas, incluidas Apple Inc. y Microsoft . [38]

En mayo de 2006, Facebook contrató a su primera becaria, Julie Zhuo . [39] Después de un mes, Zhuo fue contratada como ingeniera a tiempo completo. [39] El 26 de septiembre de 2006, Facebook se abrió a todos los que tuvieran al menos 13 años con una dirección de correo electrónico válida . [40] [41] [42] A finales de 2007, Facebook tenía 100.000 páginas en las que las empresas se promocionaban. [43] Las páginas de organización comenzaron a implementarse en mayo de 2009. [44] El 24 de octubre de 2007, Microsoft anunció que había comprado una participación del 1,6% de Facebook por 240 millones de dólares (353 millones de dólares en dólares de 2023 ) [20] , lo que le dio a Facebook un valor implícito total de alrededor de 15 mil millones de dólares (22 mil millones de dólares en dólares de 2023 ) [20] ). La compra de Microsoft incluía los derechos para colocar anuncios internacionales. [45] [46]

En mayo de 2007, en la primera conferencia de desarrolladores f8, Facebook anunció el lanzamiento de la Plataforma de Desarrolladores de Facebook , que proporciona un marco para que los desarrolladores de software creen aplicaciones que interactúen con las características principales de Facebook . Para la segunda conferencia anual de desarrolladores f8, el 23 de julio de 2008, el número de aplicaciones en la plataforma había crecido a 33.000 y el número de desarrolladores registrados había superado los 400.000. [47]

El sitio web ganó premios como la ubicación en el "Top 100 Classic Websites" de PC Magazine en 2007, [48] y ganó el "People's Voice Award" de los Webby Awards en 2008. [49] A principios de 2008, Facebook comenzó a ser rentable en términos de EBITDA , pero aún no tenía un flujo de caja positivo. [50]

El 20 de julio de 2008, Facebook presentó "Facebook Beta", un rediseño significativo de su interfaz de usuario en redes seleccionadas. El Mini-Feed y el Muro se consolidaron, los perfiles se separaron en secciones con pestañas y se hizo un esfuerzo para crear una apariencia más limpia. [51] Facebook comenzó a migrar usuarios a la nueva versión en septiembre de 2008. [52] En julio de 2008, Facebook demandó a StudiVZ , una red social alemana que supuestamente era visual y funcionalmente similar a Facebook. [53] [54]

En octubre de 2008, Facebook anunció que su sede internacional se ubicaría en Dublín , Irlanda. [55] Un estudio de Compete.com de enero de 2009 clasificó a Facebook como el servicio de redes sociales más utilizado por usuarios activos mensuales en todo el mundo . [56] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ] China bloqueó Facebook en 2009 después de los disturbios de Ürümqi . [57]

En 2009, DST de Yuri Milner (que luego se dividió en DST Global y Mail.ru Group ), junto con el magnate de metales ruso uzbeko Alisher Usmanov , invirtieron $200 millones en Facebook cuando estaba valorada en $10 mil millones. [58] [59] [60] USM Holdings de Usmanov también adquirió una participación separada en otra ocasión. [61] [58] Según el New York Times en 2013, "Usmanov y otros inversores rusos en un momento poseían casi el 10 por ciento de Facebook, aunque los detalles precisos de sus participaciones de propiedad son difíciles de evaluar". [61] Más tarde, en 2017, los Paradise Papers revelaron que los préstamos del banco estatal ruso VTB y el vehículo de inversión de Gazprom financiaron parcialmente estas inversiones de 2009, aunque, según se informa, Milner no lo sabía en ese momento. [62] [63]

En mayo de 2009, Zuckerberg dijo sobre la inversión rusa de 200 millones de dólares: "Esta inversión es puramente un colchón para nosotros. No es algo que necesitáramos para llegar a un flujo de caja positivo". [64] En septiembre de 2009, Facebook alcanzó un flujo de caja positivo antes de lo previsto [65] [66] después de cerrar una brecha de aproximadamente 200 millones de dólares en rentabilidad operativa. [66]

En 2010, Facebook ganó el premio Crunchie "Mejor startup o producto en general" [67] por tercer año consecutivo. [68]

La compañía anunció 500 millones de usuarios en julio de 2010. [69] La mitad de los miembros del sitio usaban Facebook diariamente, durante un promedio de 34 minutos, mientras que 150 millones de usuarios accedían al sitio desde dispositivos móviles. Un representante de la compañía calificó el hito como una "revolución silenciosa". [70] En octubre de 2010 se introdujeron los grupos. [71] En noviembre de 2010, según SecondMarket Inc. (una bolsa de acciones de empresas privadas), el valor de Facebook era de 41 mil millones de dólares (57,3 mil millones de dólares en dólares de 2023 [20] ). La compañía había superado ligeramente a eBay para convertirse en la tercera empresa web estadounidense más grande después de Google y Amazon.com . [72] [73]

El 15 de noviembre de 2010, Facebook anunció que había adquirido el nombre de dominio fb.com de la American Farm Bureau Federation por una cantidad no revelada. El 11 de enero de 2011, la Farm Bureau reveló 8,5 millones de dólares (11,5 millones de dólares en 2023 [20] ) en "ingresos por ventas de dominios", lo que convirtió la adquisición de FB.com en una de las diez mayores ventas de dominios de la historia. [74]

En febrero de 2011, Facebook anunció planes para trasladar su sede al antiguo campus de Sun Microsystems en Menlo Park, California. [75] [76] En marzo de 2011, se informó que Facebook estaba eliminando unos 20.000 perfiles diariamente por infracciones como spam , contenido gráfico y uso por parte de menores de edad, como parte de sus esfuerzos por impulsar la ciberseguridad . [77] Las estadísticas mostraron que Facebook alcanzó un billón de páginas vistas en el mes de junio de 2011, lo que lo convirtió en el sitio web más visitado rastreado por DoubleClick . [78] [79] Según un estudio de Nielsen , Facebook se había convertido en 2011 en el segundo sitio web más visitado en los EE. UU. detrás de Google . [80] [81]

En marzo de 2012, Facebook anunció App Center, una tienda que vende aplicaciones que funcionan a través del sitio web. La tienda estaría disponible para iPhones , dispositivos Android y para usuarios de la web móvil. [82]

La oferta pública inicial de Facebook se produjo el 17 de mayo de 2012, con un precio por acción de 38 dólares estadounidenses (50 dólares de 2023 [20] ). La empresa estaba valorada en 104.000 millones de dólares (138.000 millones de dólares de 2023 [20] ), la mayor valoración hasta esa fecha. [83] [84] [85] La IPO recaudó 16 mil millones de dólares (21,2 mil millones de dólares en dólares de 2023 [20] ), la tercera más grande en la historia de Estados Unidos, después de Visa Inc. en 2008 y AT&T Wireless en 2000. [86] [87] Con base en sus ingresos de 2012 de 5 mil millones de dólares (6,64 mil millones de dólares en dólares de 2023 [20] ), Facebook se unió a la lista Fortune 500 por primera vez en mayo de 2013, en el puesto 462. [88] Las acciones establecieron un récord de primer día para el volumen de negociación de una IPO (460 millones de acciones). [89] La IPO fue controvertida dadas las caídas inmediatas de precios que siguieron, [90] [91] [92] [93] y fue objeto de demandas, [94] mientras que la SEC y la FINRA iniciaron investigaciones. [95]

Zuckerberg anunció a principios de octubre de 2012 que Facebook tenía mil millones de usuarios activos mensuales, [96] incluidos 600 millones de usuarios móviles, 219 mil millones de subidas de fotografías y 140 mil millones de conexiones de amigos. [97]

El 1 de octubre de 2012, Zuckerberg visitó al primer ministro ruso, Dmitry Medvedev , en Moscú para estimular la innovación en las redes sociales en Rusia e impulsar la posición de Facebook en el mercado ruso. [98] [99]

El 15 de enero de 2013, Facebook anunció Facebook Graph Search , que proporciona a los usuarios una "respuesta precisa", en lugar de un enlace a una respuesta aprovechando los datos presentes en su sitio. [100] Facebook enfatizó que la función sería "consciente de la privacidad", y devolvería resultados solo de contenido ya compartido con el usuario. [101] El 3 de abril de 2013, Facebook presentó Facebook Home , una capa de interfaz de usuario para dispositivos Android que ofrece una mayor integración con el sitio. HTC anunció HTC First , un teléfono con Home precargado. [102]

El 15 de abril de 2013, Facebook anunció una alianza en 19 estados con la Asociación Nacional de Fiscales Generales, para brindarles a los adolescentes y a los padres información sobre herramientas para administrar los perfiles de redes sociales. [103] El 19 de abril, Facebook modificó su logotipo para eliminar la línea azul tenue en la parte inferior del ícono "F". La letra F se acercó al borde del cuadro. [104]

Tras una campaña de 100 grupos de defensa de derechos, Facebook acordó actualizar su política sobre el discurso de odio. La campaña destacó el contenido que promueve la violencia doméstica y la violencia sexual contra las mujeres y provocó que 15 anunciantes se retiraran, entre ellos Nissan UK, House of Burlesque y Nationwide UK. La empresa declaró inicialmente que "si bien puede ser vulgar y ofensivo, el contenido desagradable por sí solo no viola nuestras políticas". [105] Tomó medidas el 29 de mayo. [106]

El 12 de junio, Facebook anunció que estaba introduciendo hashtags en los que se podía hacer clic para ayudar a los usuarios a seguir las discusiones de tendencia o buscar de qué están hablando otros sobre un tema. [107] El condado de San Mateo , California, se convirtió en el condado con mayores ingresos del país después del cuarto trimestre de 2012 gracias a Facebook. La Oficina de Estadísticas Laborales informó que el salario promedio era un 107% más alto que el año anterior, 168.000 dólares al año (222.961 dólares en dólares de 2023 [20] ), más del 50% más alto que el siguiente condado más alto, el condado de Nueva York (mejor conocido como Manhattan ), con aproximadamente 110.000 dólares al año (145.986 dólares en dólares de 2023 [20] ). [108]

Facebook se unió a la Alianza para una Internet Asequible (A4AI) en octubre, cuando se lanzó. La A4AI es una coalición de organizaciones públicas y privadas que incluye a Google , Intel y Microsoft. Liderada por Sir Tim Berners-Lee , la A4AI busca hacer que el acceso a Internet sea más asequible para facilitar el acceso en el mundo en desarrollo. [109]

La compañía celebró su décimo aniversario durante la semana del 3 de febrero de 2014. [110] En enero de 2014, más de mil millones de usuarios se conectaron a través de un dispositivo móvil. [111] En junio, los dispositivos móviles representaban el 62% de los ingresos por publicidad, un aumento del 21% respecto al año anterior. [112] En septiembre, la capitalización de mercado de Facebook había superado los 200 mil millones de dólares (257 mil millones de dólares en dólares de 2023 ) [20] ). [113] [114] [115]

Zuckerberg participó en una sesión de preguntas y respuestas en la Universidad Tsinghua en Pekín , China , el 23 de octubre, donde intentó conversar en mandarín. Zuckerberg recibió al político chino de visita Lu Wei , conocido como el "zar de Internet" por su influencia en la política en línea de China, el 8 de diciembre. [116] [117] [118]

A partir de 2015 [update], el algoritmo de Facebook fue revisado en un intento de filtrar contenido falso o engañoso, como noticias falsas y bulos. Dependía de los usuarios que marcaban una historia en consecuencia. Facebook sostuvo que el contenido satírico no debería ser interceptado. [119] Se acusó al algoritmo de mantener una " burbuja de filtros ", donde el material con el que el usuario no está de acuerdo [120] y las publicaciones con pocos "me gusta" serían despriorizadas. [121] En noviembre, Facebook extendió la licencia por paternidad de 4 semanas a 4 meses. [122]

El 12 de abril de 2016, Zuckerberg describió su visión de 10 años, que se basaba en tres pilares principales: inteligencia artificial , mayor conectividad global y realidad virtual y aumentada . [123] En julio, se presentó una demanda de mil millones de dólares contra la empresa alegando que permitió a Hamás usarla para realizar ataques que costaron la vida a cuatro personas. [124] Facebook publicó sus planos de la cámara Surround 360 en GitHub bajo una licencia de código abierto . [125] En septiembre, ganó un Emmy por su cortometraje animado "Henry". [126] En octubre, Facebook anunció una herramienta de comunicaciones de pago llamada Workplace que tiene como objetivo "conectar a todos" en el trabajo. Los usuarios pueden crear perfiles, ver actualizaciones de compañeros de trabajo en su fuente de noticias, transmitir videos en vivo y participar en chats grupales seguros. [127]

Tras las elecciones presidenciales estadounidenses de 2016 , Facebook anunció que combatiría las noticias falsas mediante el uso de verificadores de datos de sitios como FactCheck.org y Associated Press (AP), facilitando la denuncia de bulos a través del crowdsourcing y eliminando los incentivos financieros para los abusadores. [128]

El 17 de enero de 2017, la directora de operaciones de Facebook, Sheryl Sandberg, planeó abrir Station F, un campus de incubación de empresas emergentes en París , Francia . [130] En un ciclo de seis meses, Facebook se comprometió a trabajar allí con entre diez y quince empresas emergentes basadas en datos. [131] El 18 de abril, Facebook anunció el lanzamiento de la versión beta deFacebook Spaces en su conferencia anual de desarrolladores F8. [132] Facebook Spaces es una versión de realidad virtual de Facebook para las gafas Oculus VR. En un espacio virtual y compartido, los usuarios pueden acceder a una selección curada de fotos y videos de 360 grados usando su avatar, con el apoyo del controlador. Los usuarios pueden acceder a sus propias fotos y videos, junto con los medios compartidos en su canal de noticias. [133] En septiembre, Facebook anunció que gastaría hasta mil millones de dólares en programas originales para su plataforma Facebook Watch. [134] El 16 de octubre, adquirió la aplicación de cumplidos anónimos tbh , anunciando su intención de dejar la aplicación independiente. [135] [136] [137] [138]

En octubre de 2017, Facebook amplió su trabajo con Definers Public Affairs , una firma de relaciones públicas que originalmente había sido contratada para monitorear la cobertura de prensa de la compañía para abordar las preocupaciones principalmente relacionadas con la intromisión rusa , luego el mal manejo de los datos de los usuarios por parte de Cambridge Analytica , el discurso de odio en Facebook y los llamados a la regulación. [139] El portavoz de la compañía, Tim Miller, declaró que un objetivo para las empresas de tecnología debería ser "tener contenido positivo sobre su empresa y contenido negativo sobre su competidor". Definers afirmó que George Soros fue la fuerza detrás de lo que parecía ser un amplio movimiento anti-Facebook, y creó otros medios negativos, junto con America Rising , que fue recogido por organizaciones de medios más grandes como Breitbart News . [139] [140] Facebook cortó lazos con la agencia a fines de 2018, luego de la protesta pública por su asociación. [141] Las publicaciones originadas en la página de Facebook de Breitbart News , una organización de medios anteriormente afiliada a Cambridge Analytica, [142] estuvieron entre los contenidos políticos más compartidos en Facebook. [143] [144] [145] [146] [ citas excesivas ]

En mayo de 2018, en F8 , la compañía anunció que ofrecería su propio servicio de citas. Las acciones de su competidor Match Group cayeron un 22%. [147] Facebook Dating incluye funciones de privacidad y los amigos no pueden ver el perfil de citas de sus amigos. [148] En julio, los organismos de control del Reino Unido cobraron £500,000 a Facebook por no responder a las solicitudes de borrado de datos. [149] El 18 de julio, Facebook estableció una subsidiaria llamada Lianshu Science & Technology en la ciudad de Hangzhou , China, con $30 millones ($36.4 millones en dólares de 2023 [20] ) de capital. Todas sus acciones están en manos de Facebook Hong. [150] Luego se retiró la aprobación del registro de la subsidiaria, debido a un desacuerdo entre los funcionarios de la provincia de Zhejiang y la Administración del Ciberespacio de China . [151] El 26 de julio, Facebook se convirtió en la primera empresa en perder más de 100 mil millones de dólares (121 mil millones de dólares en 2023 [20] ) de capitalización de mercado en un día, cayendo de casi 630 mil millones de dólares a 510 mil millones de dólares después de informes de ventas decepcionantes. [152] [153] El 31 de julio, Facebook dijo que la compañía había eliminado 17 cuentas relacionadas con las elecciones intermedias de Estados Unidos de 2018. El 19 de septiembre, Facebook anunció que, para la distribución de noticias fuera de los Estados Unidos, trabajaría con organizaciones de promoción de la democracia financiadas por Estados Unidos , el Instituto Republicano Internacional y el Instituto Nacional Demócrata , que están vagamente afiliados a los partidos Republicano y Demócrata . [154] A través del Laboratorio de Investigación Forense Digital, Facebook se asocia con el Atlantic Council , un grupo de expertos afiliado a la OTAN . [154] En noviembre, Facebook lanzó pantallas inteligentes con las marcas Portal y Portal Plus (Portal+). Son compatibles con Alexa (servicio de asistente personal inteligente) de Amazon . Los dispositivos incluyen la función de chat de video con Facebook Messenger. [155] [156]

En agosto de 2018, se presentó una demanda en Oakland, California, alegando que Facebook creó cuentas falsas para inflar los datos de sus usuarios y atraer anunciantes en el proceso. [13]

En enero de 2019, se inició el desafío de los 10 años [157] pidiendo a los usuarios que publicaran una fotografía de ellos mismos de hace 10 años (2009) y una foto más reciente. [158]

Criticado por su papel en la vacilación ante las vacunas , Facebook anunció en marzo de 2019 que proporcionaría a los usuarios "información autorizada" sobre el tema de las vacunas. [159] Un estudio publicado en la revista Vaccine de anuncios publicados en los tres meses anteriores a ese encontró que el 54% de los anuncios antivacunas en Facebook fueron colocados por solo dos organizaciones financiadas por conocidos activistas antivacunas. [160] [161] El Children's Health Defense / World Mercury Project presidido por Robert F. Kennedy Jr. y Stop Mandatory Vaccination , dirigido por el activista Larry Cook, publicaron el 54% de los anuncios. Los anuncios a menudo estaban vinculados a productos comerciales, como remedios naturales y libros.

El 14 de marzo, el Huffington Post informó que la agencia de relaciones públicas de Facebook había pagado a alguien para modificar la página de Wikipedia de la directora de operaciones de Facebook, Sheryl Sandberg , así como para agregar una página para la directora global de relaciones públicas, Caryn Marooney. [162]

En marzo de 2019, el autor de los tiroteos en la mezquita de Christchurch en Nueva Zelanda utilizó Facebook para transmitir imágenes en vivo del ataque mientras se desarrollaba. Facebook tardó 29 minutos en detectar el video transmitido en vivo, que fue ocho minutos más largo de lo que tardó la policía en arrestar al pistolero. Alrededor de 1,3 millones de copias del video fueron bloqueadas de Facebook, pero se publicaron y compartieron 300.000 copias. Facebook ha prometido cambios en su plataforma; el portavoz Simon Dilner dijo a Radio New Zealand que podría haber hecho un mejor trabajo. Varias empresas, incluidos los bancos ANZ y ASB, han dejado de anunciarse en Facebook después de que la empresa fuera ampliamente condenada por el público. [163] Después del ataque, Facebook comenzó a bloquear contenido nacionalista blanco , supremacista blanco y separatista blanco , diciendo que no podían separarse significativamente. Anteriormente, Facebook solo había bloqueado contenido abiertamente supremacista. La política anterior había sido condenada por grupos de derechos civiles, que describieron estos movimientos como funcionalmente indistintos. [164] [165] A mediados de abril de 2019 se realizaron más prohibiciones, excluyendo a varias organizaciones británicas de extrema derecha y a personas asociadas de Facebook, y prohibiendo también elogiarlas o apoyarlas. [166] [167]

Moulavi Zahran Hashim, miembro del NTJ y un imán islamista radical que se cree que fue el cerebro de los atentados de Pascua de 2019 en Sri Lanka , predicó en una cuenta de Facebook pro- EIIL conocida como "Al-Ghuraba". [168] [169]

.jpg/440px-President_Trump_Meets_with_Mark_Zuckerberg_(48765678712).jpg)

El 2 de mayo de 2019, en F8, la compañía anunció su nueva visión con el lema "el futuro es privado". [170] Se presentó un rediseño del sitio web y la aplicación móvil, denominado "FB5". [171] El evento también presentó planes para mejorar los grupos, [172] una plataforma de citas, [173] cifrado de extremo a extremo en sus plataformas, [174] y permitir que los usuarios de Messenger se comuniquen directamente con los usuarios de WhatsApp e Instagram. [175] [176]

El 31 de julio de 2019, Facebook anunció una asociación con la Universidad de California en San Francisco para construir un dispositivo portátil no invasivo que permite a las personas escribir simplemente imaginándose hablando. [177]

El 13 de agosto de 2019, se reveló que Facebook había contratado a cientos de contratistas para crear y obtener transcripciones de los mensajes de audio de los usuarios. [178] [179] [180] Esto era especialmente común en Facebook Messenger, donde los contratistas escuchaban y transcribían con frecuencia los mensajes de voz de los usuarios. [180] Después de que Bloomberg News informara esto por primera vez , Facebook publicó una declaración confirmando que el informe era cierto, [179] pero también declaró que el programa de monitoreo ahora estaba suspendido. [179]

El 5 de septiembre de 2019, Facebook lanzó Facebook Dating en Estados Unidos . Esta nueva aplicación permite a los usuarios integrar sus publicaciones de Instagram en su perfil de citas. [181]

Facebook News, que presenta historias seleccionadas de organizaciones de noticias, se lanzó el 25 de octubre. [182] La decisión de Facebook de incluir al sitio web de extrema derecha Breitbart News como una "fuente confiable" fue recibida negativamente. [183] [184]

El 17 de noviembre de 2019, los datos bancarios de 29.000 empleados de Facebook fueron robados del coche de un trabajador de nóminas. Los datos estaban almacenados en discos duros sin cifrar e incluían números de cuentas bancarias, nombres de los empleados, los últimos cuatro dígitos de sus números de seguridad social, salarios, bonificaciones y detalles de sus acciones. La empresa no se dio cuenta de que faltaban los discos duros hasta el 20 de noviembre. Facebook confirmó que los discos contenían información de los empleados el 29 de noviembre. Los empleados no fueron notificados del robo hasta el 13 de diciembre de 2019. [185]

El 10 de marzo de 2020, Facebook nombró a dos nuevos directores, Tracey Travis y Nancy Killefer, para su junta directiva. [186]

En junio de 2020, varias empresas importantes, incluidas Adidas , Aviva , Coca-Cola , Ford , HP , InterContinental Hotels Group , Mars , Starbucks , Target y Unilever , anunciaron que pausarían los anuncios en Facebook durante julio en apoyo de la campaña Stop Hate For Profit , que afirmaba que la empresa no estaba haciendo lo suficiente para eliminar el contenido de odio. [187] La BBC señaló que era poco probable que esto afectara a la empresa, ya que la mayor parte de los ingresos publicitarios de Facebook provienen de pequeñas y medianas empresas. [188]

El 14 de agosto de 2020, Facebook comenzó a integrar el servicio de mensajería directa de Instagram con su propio Messenger para dispositivos iOS y Android . Después de la actualización, se dice que aparecerá una pantalla de actualización en la aplicación móvil de Instagram con el siguiente mensaje: "Hay una nueva forma de enviar mensajes en Instagram" con una lista de funciones adicionales. Como parte de la actualización, el ícono de DM habitual en la esquina superior derecha de Instagram será reemplazado por el logotipo de Facebook Messenger . [189]

El 15 de septiembre de 2020, Facebook lanzó un centro de información sobre ciencia climática para promover voces autorizadas sobre el cambio climático y brindar acceso a información "factual y actualizada" sobre la ciencia climática. Presentó hechos, cifras y datos de organizaciones, incluido el Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático (IPCC), la Oficina Meteorológica , el Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente (PNUMA), la Administración Nacional Oceánica y Atmosférica (NOAA) y la Organización Meteorológica Mundial (OMM), con publicaciones de noticias relevantes. [190]

Después de las elecciones presidenciales estadounidenses de 2020 , Facebook aumentó temporalmente el peso de la calidad del ecosistema en su algoritmo de suministro de noticias. [191]

La Comisión Federal de Comercio ( FTC, por sus siglas en inglés) y una coalición de varios estados demandaron a Facebook por monopolio ilegal y antimonopolio. La FTC y los estados solicitaron a los tribunales que obligaran a Facebook a vender sus filiales WhatsApp e Instagram . [192] [193] Las demandas fueron desestimadas por un juez federal el 28 de junio de 2021, quien declaró que no se habían presentado pruebas suficientes en la demanda para determinar que Facebook era un monopolio en este momento, aunque permitió a la FTC enmendar su caso para incluir pruebas adicionales. [194] En sus presentaciones enmendadas en agosto de 2021, la FTC afirmó que Facebook había sido un monopolio en el área de las redes sociales personales desde 2011, distinguiendo las actividades de Facebook de los servicios de redes sociales como TikTok que transmiten contenido sin limitar necesariamente ese mensaje a los destinatarios previstos. [195]

En respuesta al proyecto de ley propuesto en el Parlamento australiano para un Código de Negociación de Medios de Comunicación , el 17 de febrero de 2021 Facebook bloqueó a los usuarios australianos de compartir o ver contenido de noticias en su plataforma, así como páginas de algunos servicios gubernamentales, comunitarios, sindicales, de caridad, políticos y de emergencia. [196] El gobierno australiano criticó duramente la medida, diciendo que demostraba el "inmenso poder de mercado de estos gigantes sociales digitales". [197]

El 22 de febrero, Facebook dijo que había llegado a un acuerdo con el gobierno australiano por el cual los usuarios australianos podrían volver a recibir noticias en los próximos días. Como parte de este acuerdo, Facebook y Google pueden evitar el Código de Negociación de Medios de Comunicación adoptado el 25 de febrero si "llegan a un acuerdo comercial con una empresa de noticias que no esté incluida en el Código". [198] [199] [200]

Facebook ha sido acusado de eliminar y prohibir encubiertamente contenido que hablaba a favor de las protestas de los agricultores indios o en contra del gobierno de Narendra Modi . [201] [202] [203] Los empleados de Facebook con sede en la India corren el riesgo de ser arrestados. [204]

El 27 de febrero de 2021, Facebook anunció la aplicación Facebook BARS para raperos . [205]

El 29 de junio de 2021, Facebook anunció Bulletin , una plataforma para escritores independientes. [206] [207] A diferencia de competidores como Substack , Facebook no se quedaría con una parte de las tarifas de suscripción de los escritores que utilicen esa plataforma en su lanzamiento, como Malcolm Gladwell y Mitch Albom . Según el escritor de tecnología de The Washington Post, Will Oremus, la medida fue criticada por quienes la vieron como una táctica destinada por Facebook para obligar a esos competidores a salir del negocio. [208]

En octubre de 2021, el propietario Facebook, Inc. cambió el nombre de su empresa a Meta Platforms, Inc. , o simplemente "Meta", ya que cambia su enfoque hacia la construcción del " metaverso ". Este cambio no afecta el nombre del servicio de redes sociales Facebook en sí, sino que es similar a la creación de Alphabet como empresa matriz de Google en 2015. [209]

En noviembre de 2021, Facebook declaró que dejaría de orientar los anuncios en función de datos relacionados con la salud, la raza, la etnia, las creencias políticas, la religión y la orientación sexual. El cambio se producirá en enero y afectará a todas las aplicaciones propiedad de Meta Platforms. [210]

En febrero de 2022, los usuarios activos diarios de Facebook cayeron por primera vez en sus 18 años de historia. Según Meta, la empresa matriz de Facebook, los usuarios activos diarios cayeron a 1.929 millones en los tres meses que terminaron en diciembre, frente a los 1.930 millones del trimestre anterior. Además, la empresa advirtió que el crecimiento de los ingresos se desaceleraría debido a la competencia de TikTok y YouTube, así como a que los anunciantes recortaran el gasto. [211]

El 10 de marzo de 2022, Facebook anunció que flexibilizaría temporalmente las normas para permitir el discurso violento contra los "invasores rusos". [212] Rusia luego prohibió todos los servicios Meta, incluido Instagram . [213]

En septiembre de 2022, Jonathan Vanian, reportero de tecnología de la CNBC, escribió un artículo en CNBC.com sobre las recientes dificultades que estaba experimentando Facebook, escribiendo: "Los usuarios están abandonando la plataforma y los anunciantes están reduciendo su gasto, lo que deja a Meta preparada para informar su segunda caída consecutiva en los ingresos trimestrales". También citó las malas decisiones de liderazgo al dedicar recursos al metaverso, escribiendo: "El director ejecutivo Mark Zuckerberg pasa gran parte de su tiempo haciendo proselitismo del metaverso, que puede ser el futuro de la empresa, pero no representa prácticamente ninguno de sus ingresos a corto plazo y su construcción cuesta miles de millones de dólares al año". También detalló los relatos de los analistas que predicen una "espiral de muerte" para las acciones de Facebook a medida que los usuarios se van, las impresiones de anuncios aumentan y la empresa persigue los ingresos. [214]

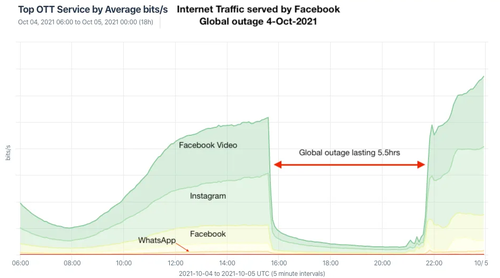

El 4 de octubre de 2021, Facebook sufrió su peor interrupción desde 2008. La interrupción tuvo alcance global y dejó fuera de servicio todas las propiedades de Facebook, incluidas Instagram y WhatsApp, desde aproximadamente las 15:39 UTC hasta las 22:05 UTC, y afectó a aproximadamente tres mil millones de usuarios. [215] [216] [217] Los expertos en seguridad identificaron el problema como una retirada de BGP de todas las rutas IP a sus servidores de nombre de dominio (DNS) , que en ese momento estaban alojados por ellos mismos. [218] [219] La interrupción también afectó a todos los sistemas de comunicaciones internas utilizados por los empleados de Facebook, lo que interrumpió los esfuerzos de restauración. [219]

La interrupción cortó las comunicaciones internas de Facebook, impidiendo que los empleados enviaran o recibieran correos electrónicos externos, accedieran al directorio corporativo y se autenticaran en algunos servicios de Google Docs y Zoom . [220] [221] La interrupción tuvo un gran impacto en las personas en el mundo en desarrollo , que dependen del programa " Free Basics " de Facebook, afectando la comunicación, los negocios y el trabajo humanitario. [222] [223] [224]

El director de tecnología de Facebook, Mike Schroepfer , escribió una disculpa después de que el tiempo de inactividad se extendió a varias horas, [225] [226] diciendo: "Los equipos están trabajando lo más rápido posible para depurar y restaurar lo más rápido posible". [227]

El 2 de noviembre de 2021, Facebook anunció que cerraría su tecnología de reconocimiento facial y eliminaría los datos de más de mil millones de usuarios. [228] Meta anunció más tarde planes para implementar la tecnología, así como otros sistemas biométricos, en sus futuros productos, como el metaverso . [229]

Según se informa, el cierre de la tecnología también detendrá el sistema de texto alternativo automatizado de Facebook, utilizado para transcribir medios en la plataforma para usuarios con discapacidad visual. [229]

En febrero de 2023, el director ejecutivo de Meta, Mark Zuckerberg, anunció que Meta comenzaría a vender insignias azules "verificadas" en Instagram y Facebook. [230]

Las publicaciones de Facebook pueden tener una cantidad ilimitada de caracteres. También pueden tener imágenes y videos.

Los usuarios pueden agregarse como "amigos" a otros usuarios, y ambas partes deben aceptar ser amigos. Las publicaciones se pueden modificar para que las vean todos (públicas), amigos, personas de un grupo determinado (grupo) o amigos seleccionados (privadas).

Los usuarios también pueden unirse a grupos. Los grupos están compuestos por personas con intereses compartidos. Por ejemplo, pueden asistir al mismo club deportivo, vivir en el mismo barrio, tener la misma raza de mascota o compartir un pasatiempo. Las publicaciones publicadas en un grupo solo pueden ser vistas por los miembros del grupo, a menos que se configuren como públicas.

Los usuarios también pueden comprar, vender o intercambiar cosas en Facebook Marketplace o en un grupo de Comprar, Intercambiar y Vender.

Los usuarios de Facebook también pueden anunciar eventos en Facebook. Los eventos anunciados pueden realizarse fuera de línea, en un sitio web que no sea Facebook o en Facebook.

El color principal del sitio es el azul, ya que Zuckerberg es daltónico entre el rojo y el verde , una constatación que se produjo después de una prueba realizada alrededor de 2007. [231] [232] Facebook se construyó inicialmente utilizando PHP , un lenguaje de programación popular diseñado para el desarrollo web. [233] PHP se utilizó para crear contenido dinámico y administrar datos en el lado del servidor de la aplicación de Facebook. Zuckerberg y los cofundadores eligieron PHP por su simplicidad y facilidad de uso, lo que les permitió desarrollar e implementar rápidamente la versión inicial de Facebook. A medida que Facebook creció en base de usuarios y funcionalidad, la empresa se encontró con desafíos de escalabilidad y rendimiento con PHP. En respuesta, los ingenieros de Facebook desarrollaron herramientas y tecnologías para optimizar el rendimiento de PHP. Una de las más significativas fue la creación de la máquina virtual HipHop ( HHVM ). Esto mejoró significativamente el rendimiento y la eficiencia de la ejecución del código PHP en los servidores de Facebook.

El sitio comenzó a cambiar de HTTP a HTTPS en enero de 2011. [234]

Facebook está desarrollado como una aplicación monolítica. Según una entrevista en 2012 con el ingeniero de desarrollo de Facebook Chuck Rossi, Facebook se compila en un blob binario de 1,5 GB que luego se distribuye a los servidores mediante un sistema de lanzamiento personalizado basado en BitTorrent . Rossi afirmó que lleva unos 15 minutos compilarlo y otros 15 minutos publicarlo en los servidores. El proceso de compilación y lanzamiento no tiene tiempo de inactividad. Los cambios en Facebook se implementan a diario. [235]

Facebook utilizó una plataforma combinada basada en HBase para almacenar datos en máquinas distribuidas. Mediante una arquitectura de seguimiento, los eventos se almacenan en archivos de registro y se realiza un seguimiento de los registros. El sistema recopila estos eventos y los escribe en el almacenamiento. Luego, la interfaz de usuario extrae los datos y los muestra a los usuarios. Facebook maneja las solicitudes como comportamiento AJAX . Estas solicitudes se escriben en un archivo de registro mediante Scribe (desarrollado por Facebook). [236]

Los datos se leen de estos archivos de registro mediante Ptail, una herramienta construida internamente para agregar datos de múltiples almacenes de Scribe. Sigue los archivos de registro y extrae los datos. Los datos de Ptail se separan en tres flujos y se envían a clústeres en diferentes centros de datos (impresión de complemento, impresiones de fuente de noticias, acciones (complemento + fuente de noticias)). Puma se utiliza para gestionar períodos de alto flujo de datos (entrada/salida o IO). Los datos se procesan en lotes para reducir la cantidad de veces que se necesitan leer y escribir en períodos de alta demanda. (Un artículo de moda genera muchas impresiones e impresiones de fuente de noticias que causan grandes sesgos de datos). Los lotes se toman cada 1,5 segundos, limitados por la memoria utilizada al crear una tabla hash . [236]

Los datos se envían luego en formato PHP. El backend está escrito en Java . Thrift se utiliza como formato de mensajería para que los programas PHP puedan consultar los servicios Java. Las soluciones de almacenamiento en caché muestran las páginas más rápidamente. Los datos se envían luego a los servidores de MapReduce donde se consultan a través de Hive. Esto sirve como copia de seguridad ya que los datos se pueden recuperar desde Hive. [236]

Facebook utiliza su propia red de distribución de contenido o "red de borde" bajo el dominio fbcdn.net para ofrecer datos estáticos. [237] [238] Hasta mediados de la década de 2010, Facebook también dependía de Akamai para los servicios de CDN. [239] [240] [241]

El 20 de marzo de 2014, Facebook anunció un nuevo lenguaje de programación de código abierto llamado Hack . Antes de su lanzamiento público, una gran parte de Facebook ya estaba funcionando y "probada en campo" utilizando el nuevo lenguaje. [242]

Cada usuario registrado en Facebook tiene un perfil personal que muestra sus publicaciones y contenido. [243] El formato de las páginas de usuario individuales fue renovado en septiembre de 2011 y se conoció como "Timeline", un feed cronológico de las historias de un usuario, [244] [245] incluyendo actualizaciones de estado, fotos, interacciones con aplicaciones y eventos. [246] El diseño permitía a los usuarios agregar una "foto de portada". [246] A los usuarios se les dieron más configuraciones de privacidad. [246] En 2007, Facebook lanzó Páginas de Facebook para que las marcas y celebridades interactuaran con sus bases de fans. [247] [248] 100,000 Páginas [ más explicación necesaria ] se lanzaron en noviembre. [249] En junio de 2009, Facebook introdujo una función de "Nombres de usuario", que permitía a los usuarios elegir un apodo único utilizado en la URL de su perfil personal, para compartir más fácilmente. [250] [251]

En febrero de 2014, Facebook amplió la configuración de género, añadiendo un campo de entrada personalizado que permite a los usuarios elegir entre una amplia gama de identidades de género. Los usuarios también pueden establecer qué conjunto de pronombres específicos de género se deben utilizar en referencia a ellos en todo el sitio. [252] [253] [254] En mayo de 2014, Facebook introdujo una función que permite a los usuarios solicitar información no revelada por otros usuarios en sus perfiles. Si un usuario no proporciona información clave, como ubicación, ciudad natal o estado civil, otros usuarios pueden utilizar un nuevo botón "preguntar" para enviar un mensaje preguntando sobre ese elemento al usuario con un solo clic. [255] [256]

El News Feed aparece en la página de inicio de cada usuario y destaca información que incluye cambios de perfil, próximos eventos y cumpleaños de amigos. [257] Esto permitió a los spammers y otros usuarios manipular estas funciones creando eventos ilegítimos o publicando cumpleaños falsos para atraer la atención a su perfil o causa. [258] Inicialmente, el News Feed causó insatisfacción entre los usuarios de Facebook; algunos se quejaron de que estaba demasiado desordenado y lleno de información no deseada, otros estaban preocupados de que hacía demasiado fácil para otros rastrear actividades individuales (como cambios de estado de relación, eventos y conversaciones con otros usuarios). [259] Zuckerberg se disculpó por el fracaso del sitio al no incluir funciones de privacidad adecuadas. Los usuarios luego obtuvieron el control sobre qué tipos de información se comparten automáticamente con los amigos. Los usuarios ahora pueden evitar que las categorías de amigos establecidas por el usuario vean actualizaciones sobre ciertos tipos de actividades, incluidos cambios de perfil, publicaciones en el muro y amigos recientemente agregados. [260]

El 23 de febrero de 2010, Facebook obtuvo una patente [261] sobre ciertos aspectos de su News Feed. La patente cubre los News Feeds en los que se proporcionan enlaces para que un usuario pueda participar en la actividad de otro usuario. [262] La clasificación y visualización de historias en el News Feed de un usuario está regida por el algoritmo EdgeRank . [263]

La aplicación Fotos permite a los usuarios subir álbumes y fotos. [264] Cada álbum puede contener 200 fotos. [265] La configuración de privacidad se aplica a álbumes individuales. Los usuarios pueden " etiquetar " o etiquetar a amigos en una foto. El amigo recibe una notificación sobre la etiqueta con un enlace a la foto. [266] Esta función de etiquetado de fotos fue desarrollada por Aaron Sittig, ahora director de estrategia de diseño en Facebook, y el ex ingeniero de Facebook Scott Marlette en 2006 y recién se le concedió una patente en 2011. [267] [268]

El 7 de junio de 2012, Facebook lanzó su Centro de aplicaciones para ayudar a los usuarios a encontrar juegos y otras aplicaciones. [269]

El 13 de mayo de 2015, Facebook, en asociación con importantes portales de noticias, lanzó "Artículos instantáneos" para proporcionar noticias en el servicio de noticias de Facebook sin salir del sitio. [270] [271]

En enero de 2017, Facebook lanzó Facebook Stories para iOS y Android en Irlanda. La función, que sigue el formato de las historias de Snapchat e Instagram, permite a los usuarios subir fotos y vídeos que aparecen sobre las noticias de amigos y seguidores y desaparecen después de 24 horas. [272]

El 11 de octubre de 2017, Facebook introdujo la función de publicaciones en 3D para permitir la carga de recursos interactivos en 3D. [273] El 11 de enero de 2018, Facebook anunció que cambiaría el News Feed para priorizar el contenido de amigos y familiares y restar importancia al contenido de las empresas de medios. [274]

En febrero de 2020, Facebook anunció que gastaría mil millones de dólares (1.180 millones de dólares en 2023 [20] ) para licenciar material de noticias de los editores durante los próximos tres años; una promesa que se produce en un momento en que la compañía está bajo el escrutinio de los gobiernos de todo el mundo por no pagar por el contenido de noticias que aparece en la plataforma. La promesa se sumaría a los 600 millones de dólares (706 millones de dólares en 2023 [20] ) pagados desde 2018 a través de acuerdos con empresas de noticias como The Guardian y Financial Times . [275] [276] [277]

En marzo y abril de 2021, en respuesta al anuncio de Apple de cambios en la política de Identificador para anunciantes de sus dispositivos iOS , que incluía la exigencia de que los desarrolladores de aplicaciones solicitaran directamente a los usuarios la posibilidad de realizar un seguimiento de forma voluntaria, Facebook compró anuncios en periódicos de página completa para intentar convencer a los usuarios de que permitieran el seguimiento, destacando los efectos que tienen los anuncios dirigidos en las pequeñas empresas. [278] Los esfuerzos de Facebook finalmente no tuvieron éxito, ya que Apple lanzó iOS 14.5 a fines de abril de 2021, que contiene la función para los usuarios en lo que se ha denominado "Transparencia de seguimiento de aplicaciones". Además, las estadísticas de Flurry Analytics, subsidiaria de Verizon Communications, muestran que el 96% de todos los usuarios de iOS en los Estados Unidos no permiten el seguimiento en absoluto, y solo el 12% de los usuarios de iOS en todo el mundo lo permiten, lo que algunos medios de comunicación consideran "la pesadilla de Facebook", entre términos similares. [279] [280] [281] [282] A pesar de la noticia, Facebook ha declarado que la nueva política y la actualización del software serían "manejables". [283]

El botón "Me gusta", estilizado como un ícono de "pulgar hacia arriba", se habilitó por primera vez el 9 de febrero de 2009, [284] y permite a los usuarios interactuar fácilmente con actualizaciones de estado, comentarios, fotos y videos, enlaces compartidos por amigos y anuncios. Una vez que un usuario hace clic, es más probable que el contenido designado aparezca en los feeds de noticias de los amigos . [285] [286] El botón muestra la cantidad de otros usuarios a quienes les ha gustado el contenido. [287] El botón Me gusta se extendió a los comentarios en junio de 2010. [288] En febrero de 2016, Facebook expandió Me gusta a "Reacciones", eligiendo entre cinco emociones predefinidas, que incluyen "Amor", "Jaja", "Guau", "Triste" o "Enojado". [289] [290] [291] [292] A fines de abril de 2020, durante la pandemia de COVID-19 , se agregó una nueva reacción de "Cuidado". [293]

Facebook Messenger es un servicio de mensajería instantánea y una aplicación de software. Comenzó como Facebook Chat en 2008, [294] se renovó en 2010 [295] y finalmente se convirtió en una aplicación móvil independiente en agosto de 2011, aunque sigue siendo parte de la página del usuario en los navegadores. [296]

Como complemento a las conversaciones habituales, Messenger permite a los usuarios realizar llamadas de voz [299] y videollamadas individuales [ 297] y grupales [298] . [300] Su aplicación para Android tiene soporte integrado para SMS [301] y "Chat Heads", que son iconos redondos de fotos de perfil que aparecen en la pantalla independientemente de la aplicación que esté abierta, [302] mientras que ambas aplicaciones admiten múltiples cuentas, [303] conversaciones con cifrado de extremo a extremo opcional [304] y "Juegos instantáneos". [305] Algunas funciones, incluido el envío de dinero [306] y la solicitud de transporte, [307] están limitadas a los Estados Unidos. [306] En 2017, Facebook agregó "Messenger Day", una función que permite a los usuarios compartir fotos y videos en formato de historia con todos sus amigos y el contenido desaparece después de 24 horas; [308] Reacciones, que permite a los usuarios tocar y mantener presionado un mensaje para agregar una reacción a través de un emoji ; [309] y Menciones, que permite a los usuarios en conversaciones grupales escribir @ para dar una notificación a un usuario en particular. [309]

En abril de 2020, Facebook comenzó a implementar una nueva función llamada Messenger Rooms , una función de chat de video que permite a los usuarios chatear con hasta 50 personas a la vez. [310] En julio de 2020, Facebook agregó una nueva función en Messenger que permite a los usuarios de iOS usar Face ID o Touch ID para bloquear sus chats. La función se llama App Lock y es parte de varios cambios en Messenger con respecto a la privacidad y la seguridad. [311] [312] El 13 de octubre de 2020, la aplicación Messenger introdujo la mensajería entre aplicaciones con Instagram, que se lanzó en septiembre de 2021. [313] Además de la mensajería integrada, la aplicación anunció la introducción de un nuevo logotipo, que será una fusión del logotipo de Messenger e Instagram. [314]

Las empresas y los usuarios pueden interactuar a través de Messenger con funciones como el seguimiento de compras y la recepción de notificaciones, así como la interacción con representantes de servicio al cliente. Los desarrolladores externos pueden integrar aplicaciones en Messenger, lo que permite a los usuarios ingresar a una aplicación mientras están dentro de Messenger y, opcionalmente, compartir detalles de la aplicación en un chat. [315] Los desarrolladores pueden crear chatbots en Messenger, para usos como la creación de bots por parte de los editores de noticias para distribuir noticias. [316] El asistente virtual M (US) escanea los chats en busca de palabras clave y sugiere acciones relevantes, como su sistema de pagos para los usuarios que mencionan dinero. [317] [318] Los chatbots grupales aparecen en Messenger como "Extensiones de chat". Una pestaña de "Descubrimiento" permite encontrar bots y habilitar códigos QR especiales de marca que, cuando se escanean, llevan al usuario a un bot específico. [319]

La política de datos de Facebook describe sus políticas para recopilar, almacenar y compartir datos de los usuarios. [320] Facebook permite a los usuarios controlar el acceso a publicaciones individuales y a su perfil [321] a través de configuraciones de privacidad . [322] El nombre del usuario y la foto de perfil (si corresponde) son públicos.

Los ingresos de Facebook dependen de la publicidad dirigida, que implica analizar los datos de los usuarios para decidir qué anuncios mostrar a cada uno. Facebook compra datos de terceros, recopilados tanto de fuentes online como offline, para complementar sus propios datos sobre los usuarios. Facebook sostiene que no comparte los datos utilizados para la publicidad dirigida con los propios anunciantes. [323] La empresa afirma:

"Ofrecemos a los anunciantes informes sobre los tipos de personas que ven sus anuncios y el rendimiento de estos, pero no compartimos información que lo identifique personalmente (información como su nombre o dirección de correo electrónico que por sí sola puede usarse para contactarlo o identificar quién es usted) a menos que nos dé permiso. Por ejemplo, proporcionamos información demográfica y de intereses generales a los anunciantes (por ejemplo, que un anuncio fue visto por una mujer de entre 25 y 34 años que vive en Madrid y le gusta la ingeniería de software) para ayudarlos a comprender mejor a su audiencia. También confirmamos qué anuncios de Facebook lo llevaron a realizar una compra o realizar una acción con un anunciante". [320]

A partir de octubre de 2021 [update], Facebook afirma que utiliza la siguiente política para compartir datos de usuarios con terceros:

Aplicaciones, sitios web e integraciones de terceros en nuestros Productos o que los utilizan.

Cuando eliges usar aplicaciones, sitios web u otros servicios de terceros que usan o están integrados con nuestros Productos, estos pueden recibir información sobre lo que publicas o compartes. Por ejemplo, cuando juegas un juego con tus amigos de Facebook o usas un botón de Comentar o Compartir de Facebook en un sitio web, el desarrollador del juego o el sitio web pueden recibir información sobre tus actividades en el juego o recibir un comentario o enlace que compartas desde el sitio web en Facebook. Además, cuando descargas o usas dichos servicios de terceros, estos pueden acceder a tu perfil público en Facebook y a cualquier información que compartas con ellos. Las aplicaciones y los sitios web que usas pueden recibir tu lista de amigos de Facebook si eliges compartirla con ellos. Pero las aplicaciones y los sitios web que usas no podrán recibir ninguna otra información sobre tus amigos de Facebook de tu parte, ni información sobre ninguno de tus seguidores de Instagram (aunque tus amigos y seguidores pueden, por supuesto, elegir compartir esta información ellos mismos). La información recopilada por estos servicios de terceros está sujeta a sus propios términos y políticas, no a este.

Los dispositivos y sistemas operativos que proporcionan versiones nativas de Facebook e Instagram (es decir, donde no hemos desarrollado nuestras propias aplicaciones) tendrán acceso a toda la información que usted elija compartir con ellos, incluida la información que sus amigos comparten con usted, para que puedan brindarle nuestra funcionalidad principal.

Nota: Estamos en proceso de restringir aún más el acceso de los desarrolladores a los datos para ayudar a prevenir el abuso. Por ejemplo, eliminaremos el acceso de los desarrolladores a tus datos de Facebook e Instagram si no has usado su aplicación en 3 meses, y estamos cambiando el inicio de sesión, de modo que en la próxima versión, reduciremos los datos que una aplicación puede solicitar sin revisión de la aplicación para incluir solo el nombre, el nombre de usuario y la biografía de Instagram, la foto de perfil y la dirección de correo electrónico. Solicitar cualquier otro dato requerirá nuestra aprobación. [320]

Facebook también compartirá datos con las autoridades policiales si es necesario. [320]

Las políticas de Facebook han cambiado repetidamente desde el debut del servicio, en medio de una serie de controversias que abarcan desde cuán bien protege los datos de los usuarios, hasta qué punto permite a los usuarios controlar el acceso, hasta los tipos de acceso que se les da a terceros, incluidas empresas, campañas políticas y gobiernos. Estas facilidades varían según el país, ya que algunas naciones exigen que la empresa ponga los datos a disposición (y limite el acceso a los servicios), mientras que la regulación GDPR de la Unión Europea exige protecciones adicionales de la privacidad. [324]

El 29 de julio de 2011, Facebook anunció su programa Bug Bounty, que pagaba a los investigadores de seguridad un mínimo de 500 dólares (677 dólares de 2023 [20] ) por informar sobre agujeros de seguridad. La empresa prometió no perseguir a los piratas informáticos de "sombrero blanco" que identificaran tales problemas. [325] [326] Esto llevó a que los investigadores de muchos países participaran, en particular en la India y Rusia. [327]

El rápido crecimiento de Facebook comenzó tan pronto como estuvo disponible y continuó durante 2018, antes de comenzar a declinar.

Facebook superó los 100 millones de usuarios registrados en 2008, [328] y los 500 millones en julio de 2010. [69] Según los datos de la compañía en el anuncio de julio de 2010, la mitad de los miembros del sitio usaban Facebook diariamente, durante un promedio de 34 minutos, mientras que 150 millones de usuarios accedían al sitio a través del móvil. [70]

En octubre de 2012, los usuarios activos mensuales de Facebook superaron los mil millones, [96] [329] con 600 millones de usuarios móviles, 219 mil millones de cargas de fotos y 140 mil millones de conexiones de amigos. [97] La marca de los 2 mil millones de usuarios se cruzó en junio de 2017. [330] [331]

En noviembre de 2015, tras el escepticismo sobre la precisión de su medición de "usuarios activos mensuales", Facebook cambió su definición a un miembro conectado que visita el sitio de Facebook a través del navegador web o la aplicación móvil, o utiliza la aplicación Facebook Messenger , en el período de 30 días anterior a la medición. Esto excluía el uso de servicios de terceros con integración de Facebook, que anteriormente se contabilizaba. [332]

Entre 2017 y 2019, el porcentaje de la población estadounidense mayor de 12 años que utiliza Facebook ha disminuido del 67% al 61% (una disminución de unos 15 millones de usuarios estadounidenses), con una caída mayor entre los estadounidenses más jóvenes (una disminución en el porcentaje de estadounidenses de entre 12 y 34 años que son usuarios del 58% en 2015 al 29% en 2019). [333] [334] La disminución coincidió con un aumento en la popularidad de Instagram, que también es propiedad de Meta. [333] [334]

El número de usuarios activos diarios experimentó un descenso trimestral por primera vez en el último trimestre de 2021, bajando a 1.929 millones desde 1.930 millones, [335] pero aumentó de nuevo el trimestre siguiente a pesar de estar prohibido en Rusia. [336]

Históricamente, los comentaristas han ofrecido predicciones sobre el declive o el fin de Facebook, basándose en causas como una base de usuarios en descenso; [337] las dificultades legales de ser una plataforma cerrada , la incapacidad de generar ingresos, la incapacidad de ofrecer privacidad al usuario, la incapacidad de adaptarse a las plataformas móviles o el fin de Facebook para presentar un reemplazo de próxima generación; [338] o el papel de Facebook en la interferencia rusa en las elecciones de Estados Unidos de 2016. [ 339]

En abril de 2023, el mayor número de usuarios de Facebook se encontraba en India y Estados Unidos, seguidos de Indonesia, Brasil, México y Filipinas. [341] Por regiones, el mayor número de usuarios en 2018 se encuentra en Asia-Pacífico (947 millones), seguido de Europa (381 millones) y Estados Unidos y Canadá (242 millones). El resto del mundo tiene 750 millones de usuarios. [342]

Durante el período 2008-2018, el porcentaje de usuarios menores de 34 años disminuyó a menos de la mitad del total. [324]

En muchos países, los sitios de redes sociales y aplicaciones móviles han sido bloqueados de forma temporal, intermitente o permanente, incluidos: Brasil , [343] China , [344] Irán , [345] Vietnam , [346] Pakistán , [347] Siria , [348] y Corea del Norte . En mayo de 2018, el gobierno de Papúa Nueva Guinea anunció que prohibiría Facebook durante un mes mientras consideraba el impacto del sitio web en el país, aunque desde entonces no se ha producido ninguna prohibición. [349] En 2019, Facebook anunció que comenzaría a aplicar su prohibición a los usuarios, incluidos los influencers , que promocionen cualquier producto de vapeo , tabaco o armas en sus plataformas. [350]

"Estoy aquí hoy porque creo que los productos de Facebook dañan a los niños, fomentan la división y debilitan nuestra democracia. Los líderes de la empresa saben cómo hacer que Facebook e Instagram sean más seguros, pero no harán los cambios necesarios porque han puesto sus ganancias astronómicas por delante de las personas".

— Frances Haugen , condenando la falta de transparencia en torno a Facebook en una audiencia del Congreso de Estados Unidos (2021). [351]

"No creo que las empresas privadas deban tomar todas las decisiones por sí solas. Por eso hemos abogado por una actualización de las regulaciones de Internet durante varios años. He testificado en el Congreso varias veces y les he pedido que actualicen estas regulaciones. He escrito artículos de opinión que describen las áreas de regulación que creemos que son más importantes en relación con las elecciones, el contenido dañino, la privacidad y la competencia".

—Mark Zuckerberg, respondiendo a las revelaciones de Frances Haugen (2021). [352]

La importancia y la escala de Facebook han dado lugar a críticas en muchos ámbitos. Entre los problemas se incluyen la privacidad en Internet , la retención excesiva de información de los usuarios, [353] su software de reconocimiento facial , DeepFace [354] [355] su carácter adictivo [356] y su papel en el lugar de trabajo, incluido el acceso de los empleadores a las cuentas de los empleados. [357]

Facebook ha sido criticado por el uso de electricidad, [358] evasión fiscal, [359] políticas de requisitos de nombre real para los usuarios, [360] censura [361] [362] y su participación en el programa de vigilancia PRISM de los Estados Unidos . [363] Según The Express Tribune , Facebook "evitó miles de millones de dólares en impuestos utilizando empresas offshore". [364]

Se alega que Facebook tiene efectos psicológicos nocivos en sus usuarios, incluidos sentimientos de celos [365] [366] y estrés, [367] [368] falta de atención [369] y adicción a las redes sociales . [370] [371] Según Kaufmann et al., las motivaciones de las madres para usar las redes sociales a menudo están relacionadas con su salud social y mental. [372] La reguladora antimonopolio europea Margrethe Vestager declaró que los términos de servicio de Facebook relacionados con los datos privados estaban "desequilibrados". [373]

Facebook ha sido criticado por permitir a los usuarios publicar material ilegal u ofensivo. Los detalles incluyen violación de derechos de autor y propiedad intelectual , [374] discurso de odio , [375] [376] incitación a la violación [377] y terrorismo, [378] [379] noticias falsas , [380] [381] [382] y crímenes, asesinatos y transmisión en vivo de incidentes violentos. [383] [384] [385] Los comentaristas han acusado a Facebook de facilitar voluntariamente la difusión de dicho contenido. [386] [387] [388] Sri Lanka bloqueó Facebook y WhatsApp en mayo de 2019 después de los disturbios antimusulmanes , los peores en el país desde el atentado del Domingo de Pascua en el mismo año como medida temporal para mantener la paz en Sri Lanka. [389] [390] Facebook eliminó 3 mil millones de cuentas falsas solo durante el último trimestre de 2018 y el primer trimestre de 2019; [391] En comparación, la red social reporta 2.39 mil millones de usuarios activos mensuales. [391]

A finales de julio de 2019, la empresa anunció que estaba bajo investigación antimonopolio por parte de la Comisión Federal de Comercio . [392]

El grupo de defensa del consumidor, Which?, afirma que las personas siguen utilizando Facebook para crear valoraciones fraudulentas de cinco estrellas para diversos productos. El grupo ha identificado 14 comunidades que intercambian reseñas por dinero o artículos gratuitos como relojes, auriculares y aspersores. [393]

Facebook ha experimentado un flujo constante de controversias sobre cómo maneja la privacidad del usuario, ajustando repetidamente sus configuraciones y políticas de privacidad. [394]

Desde 2009, Facebook participa en el programa secreto PRISM, compartiendo con la Agencia de Seguridad Nacional de Estados Unidos audio, vídeo, fotografías, correos electrónicos, documentos y registros de conexión de los perfiles de usuarios, entre otros servicios de redes sociales. [395] [396]

El 29 de noviembre de 2011, Facebook llegó a un acuerdo con la Comisión Federal de Comercio por los cargos de que había engañado a los consumidores al no cumplir sus promesas de privacidad. [397] En agosto de 2013, High-Tech Bridge publicó un estudio que mostraba que Facebook estaba accediendo a enlaces incluidos en los mensajes del servicio de mensajería. [398] En enero de 2014, dos usuarios presentaron una demanda contra Facebook alegando que su privacidad había sido violada por esta práctica. [399]

El 7 de junio de 2018, Facebook anunció que un error había provocado que alrededor de 14 millones de usuarios de Facebook tuvieran su configuración predeterminada para compartir todas las publicaciones nuevas establecida en "pública". [400] Su acuerdo de intercambio de datos con empresas chinas como Huawei fue objeto de escrutinio por parte de los legisladores estadounidenses, aunque la información a la que se accedió no se almacenó en los servidores de Huawei y permaneció en los teléfonos de los usuarios. [401]

El 4 de abril de 2019, se encontraron 500 millones de registros de usuarios de Facebook expuestos en servidores en la nube de Amazon , que contenían información sobre amigos, me gusta, grupos y ubicaciones de registro de los usuarios, así como nombres, contraseñas y direcciones de correo electrónico. [402]

En septiembre de 2019, se descubrió que los números de teléfono de al menos 200 millones de usuarios de Facebook estaban expuestos en una base de datos abierta en línea. Incluían 133 millones de usuarios de EE. UU., 18 millones del Reino Unido y 50 millones de usuarios de Vietnam . Después de eliminar los duplicados, los 419 millones de registros se redujeron a 219 millones. La base de datos se desconectó después de que TechCrunch se comunicara con el servidor web. Se cree que los registros se acumularon utilizando una herramienta que Facebook deshabilitó en abril de 2018 después de la controversia de Cambridge Analytica . Una portavoz de Facebook dijo en un comunicado: "El conjunto de datos es antiguo y parece tener información obtenida antes de que hiciéramos cambios el año pasado... No hay evidencia de que las cuentas de Facebook estuvieran comprometidas". [403]

Los problemas de privacidad de Facebook provocaron que empresas como Viber Media y Mozilla suspendieran la publicidad en las plataformas de Facebook. [404] [405]

Un estudio de enero de 2024 realizado por Consumer Reports descubrió que, entre un grupo autoseleccionado de participantes voluntarios, cada usuario es monitoreado o rastreado por más de dos mil empresas en promedio. LiveRamp , un corredor de datos con sede en San Francisco, es responsable del 96 por ciento de los datos. Otras empresas como Home Depot , Macy's y Walmart también están involucradas. [406]

En marzo de 2024, un tribunal de California publicó documentos que detallaban el "Proyecto Cazafantasmas" de Facebook de 2016. El proyecto tenía como objetivo ayudar a Facebook a competir con Snapchat e implicaba que Facebook intentara desarrollar herramientas de descifrado para recopilar, descifrar y analizar el tráfico que generaban los usuarios al visitar Snapchat y, finalmente, YouTube y Amazon. La empresa finalmente utilizó su herramienta Onavo para iniciar ataques de intermediario y leer el tráfico de los usuarios antes de que se cifrara. [407]

La EEOC acusó a Facebook de cometer un sesgo racial "sistémico" con base en las quejas de tres candidatos rechazados y un empleado actual de la empresa. Los tres empleados rechazados, junto con el gerente de operaciones de Facebook en marzo de 2021, acusaron a la empresa de discriminar a las personas negras. La EEOC ha iniciado una investigación sobre el caso. [408]

Un " perfil oculto " se refiere a los datos que Facebook recopila sobre individuos sin su permiso explícito. Por ejemplo, el botón "Me gusta" que aparece en sitios web de terceros permite a la empresa recopilar información sobre los hábitos de navegación en Internet de un individuo, incluso si el individuo no es un usuario de Facebook. [409] [410] Los datos también pueden ser recopilados por otros usuarios. Por ejemplo, un usuario de Facebook puede vincular su cuenta de correo electrónico a su Facebook para encontrar amigos en el sitio, lo que permite a la empresa recopilar las direcciones de correo electrónico de usuarios y no usuarios por igual. [411] Con el tiempo, se recopilan innumerables puntos de datos sobre un individuo; cualquier punto de datos individual tal vez no pueda identificar a un individuo, pero en conjunto permite a la empresa formar un "perfil" único.

Esta práctica ha sido criticada por quienes creen que las personas deberían poder optar por no participar en la recopilación involuntaria de datos. Además, si bien los usuarios de Facebook tienen la capacidad de descargar e inspeccionar los datos que proporcionan al sitio, los datos del "perfil oculto" del usuario no están incluidos, y los no usuarios de Facebook no tienen acceso a esta herramienta de todos modos. La empresa tampoco ha aclarado si es posible o no que una persona revoque el acceso de Facebook a su "perfil oculto". [409]

El cliente de Facebook Global Science Research vendió información sobre más de 87 millones de usuarios de Facebook a Cambridge Analytica, una empresa de análisis de datos políticos dirigida por Alexander Nix . [412] Aunque aproximadamente 270.000 personas utilizaban la aplicación, la API de Facebook permitía la recopilación de datos de sus amigos sin su conocimiento. [413] Al principio, Facebook restó importancia a la importancia de la infracción y sugirió que Cambridge Analytica ya no tenía acceso. Facebook emitió entonces un comunicado expresando su alarma y suspendió a Cambridge Analytica. La revisión de documentos y entrevistas con antiguos empleados de Facebook sugirió que Cambridge Analytica todavía poseía los datos. [414] Esto fue una violación del decreto de consentimiento de Facebook con la Comisión Federal de Comercio . Esta violación potencialmente conllevaba una multa de 40.000 dólares (48.534 dólares de 2023 [20] ) por cada incidencia, lo que totaliza billones de dólares. [415]

According to The Guardian, both Facebook and Cambridge Analytica threatened to sue the newspaper if it published the story. After publication, Facebook claimed that it had been "lied to". On March 23, 2018, The English High Court granted an application by the Information Commissioner's Office for a warrant to search Cambridge Analytica's London offices, ending a standoff between Facebook and the Information Commissioner over responsibility.[416]

On March 25, Facebook published a statement by Zuckerberg in major UK and US newspapers apologizing over a "breach of trust".[417]

You may have heard about a quiz app built by a university researcher that leaked Facebook data of millions of people in 2014. This was a breach of trust, and I'm sorry we didn't do more at the time. We're now taking steps to make sure this doesn't happen again.

We've already stopped apps like this from getting so much information. Now we're limiting the data apps get when you sign in using Facebook.

We're also investigating every single app that had access to large amounts of data before we fixed this. We expect there are others. And when we find them, we will ban them and tell everyone affected.

Finally, we'll remind you which apps you've given access to your information – so you can shut off the ones you don't want anymore.

Thank you for believing in this community. I promise to do better for you.

On March 26, the Federal Trade Commission opened an investigation into the matter.[418] The controversy led Facebook to end its partnerships with data brokers who aid advertisers in targeting users.[394]

On April 24, 2019, Facebook said it could face a fine between $3 billion ($3.58 billion in 2023 dollars[20]) to $5 billion ($5.96 billion in 2023 dollars[20]) as the result of an investigation by the Federal Trade Commission.[419] On July 24, 2019, the FTC fined Facebook $5 billion, the largest penalty ever imposed on a company for violating consumer privacy. Additionally, Facebook had to implement a new privacy structure, follow a 20-year settlement order, and allow the FTC to monitor Facebook.[420] Cambridge Analytica's CEO and a developer faced restrictions on future business dealings and were ordered to destroy any personal information they collected. Cambridge Analytica filed for bankruptcy.[421]

Facebook also implemented additional privacy controls and settings[422] in part to comply with the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which took effect in May.[423] Facebook also ended its active opposition to the California Consumer Privacy Act.[424]

Some, such as Meghan McCain have drawn an equivalence between the use of data by Cambridge Analytica and the Barack Obama's 2012 campaign, which, according to Investor's Business Daily, "encouraged supporters to download an Obama 2012 Facebook app that, when activated, let the campaign collect Facebook data both on users and their friends."[425][426][427] Carol Davidsen, the Obama for America (OFA) former director of integration and media analytics, wrote that "Facebook was surprised we were able to suck out the whole social graph, but they didn't stop us once they realised that was what we were doing".[426][427] PolitiFact has rated McCain's statements "Half-True", on the basis that "in Obama's case, direct users knew they were handing over their data to a political campaign" whereas with Cambridge Analytica, users thought they were only taking a personality quiz for academic purposes, and while the Obama campaign only used the data "to have their supporters contact their most persuadable friends", Cambridge Analytica "targeted users, friends and lookalikes directly with digital ads."[428]

In July 2019, cybersecurity researcher Sam Jadali exposed a catastrophic data leak known as DataSpii involving data provider DDMR and marketing intelligence company Nacho Analytics (NA).[429][430] Branding itself as the "God mode for the internet," NA through DDMR, provided its members access to private Facebook photos and Facebook Messenger attachments including tax returns.[431] DataSpii harvested data from millions of Chrome and Firefox users through compromised browser extensions.[432] The NA website stated it collected data from millions of opt-in users. Jadali, along with journalists from Ars Technica and The Washington Post, interviewed impacted users, including a Washington Post staff member. According to the interviews, the impacted users did not consent to such collection.

DataSpii demonstrated how a compromised user exposed the data of others, including the private photos and Messenger attachments belonging to a Facebook user's network of friends.[431]