Albania ( / æ l ˈ b eɪ norte yo ə , ɔː l -/ a(w)l-BAY-nee-ə;albanés:ShqipërioShqipëria),[a]oficialmente laRepública de Albania(en albanés:Republika e Shqipërisë),[b]es un país delsudeste de Europa. Está en losBalcanes, en losAdriáticoyJónicodentro delmar Mediterráneo, y compartefronteras terrestresconMontenegroal noroeste,Kosovoal noreste,Macedonia del Norteal este yGreciaal sur. Con una superficie de 28.748 km2(11.100 millas cuadradas), tiene una variada gama de condiciones climáticas, geológicas, hidrológicas y morfológicas. Los paisajes de Albania varían desde las escarpadas montañas cubiertas de nieve de losAlpes albanesesy losmontesKorab,Skanderbeg,Pindusy, hasta las fértiles llanuras que se extienden desde lasdel Adriáticoyel Jónico.Tiranaes la capital y la ciudad más grande del país, seguida deDurrës,VlorëyShkodër.

En la antigüedad, los ilirios habitaban las regiones del norte y centro de Albania, mientras que los epirotas habitaban el sur. Varias colonias griegas antiguas importantes también se establecieron en la costa. El reino ilirio centrado en lo que ahora es Albania fue la potencia dominante antes del ascenso de Macedonia . [7] En el siglo II a. C., la República romana anexó la región y, después de la división del Imperio romano, pasó a formar parte de Bizancio . El primer principado autónomo albanés conocido, el Líbano , se estableció en el siglo XII. El Reino de Albania , el Principado de Albania y Albania Véneta se formaron entre los siglos XIII y XV en diferentes partes del país, junto con otros principados y entidades políticas albanesas. A finales del siglo XV, Albania pasó a formar parte del Imperio otomano . En 1912, el moderno estado albanés declaró su independencia . En 1939, Italia invadió el Reino de Albania , que se convirtió en la Gran Albania , y luego en un protectorado de la Alemania nazi durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial . [8] Después de la guerra, se formó la República Popular Socialista de Albania , que duró hasta las Revoluciones de 1991 concluyeron con la caída del comunismo en Albania y finalmente el establecimiento de la actual República de Albania.

Desde su independencia en 1912, Albania ha experimentado una evolución política diversa, pasando de una monarquía a un régimen comunista antes de convertirse en una república constitucional parlamentaria soberana . Gobernada por una constitución que prioriza la separación de poderes, la estructura política del país incluye un parlamento , un presidente ceremonial , un primer ministro funcional y una jerarquía de tribunales. Albania es un país en desarrollo con una economía de ingresos medios-altos impulsada por el sector de servicios, en el que la manufactura y el turismo también desempeñan papeles importantes. [9] Después de la disolución de su sistema comunista, el país pasó de una planificación centralizada a una economía de mercado abierta . [10] Los ciudadanos albaneses tienen acceso universal a la atención sanitaria y educación primaria y secundaria gratuita.

Los orígenes históricos del término "Albania" se remontan al latín medieval , y se cree que sus cimientos están asociados con la tribu iliria de los albaneses . Esta conexión obtiene mayor apoyo del trabajo del geógrafo griego antiguo Ptolomeo durante el siglo II d. C., donde incluyó el asentamiento de Albanopolis situado al noreste de Durrës . [11] [12] La presencia de un asentamiento medieval llamado Albanon o Arbanon sugiere la posibilidad de una continuidad histórica. La relación precisa entre estas referencias históricas y la cuestión de si Albanopolis era sinónimo de Albanon siguen siendo temas de debate académico. [13]

El historiador bizantino Miguel Ataliates , en su relato histórico del siglo XI, proporciona la primera referencia indiscutible a los albaneses, cuando menciona que participaron en una revuelta contra Constantinopla en 1079. [14] También identifica a los arbanitai como súbditos del duque de Dyrrachium . [15] En la Edad Media, Albania era conocida como Arbëri o Arbëni por sus habitantes, que se identificaban como Arbëreshë o Arbëneshë . [16] Los albaneses emplean los términos Shqipëri o Shqipëria para su nación, designaciones que rastrean sus orígenes históricos hasta el siglo XIV. [17] Pero solo a finales del siglo XVII y principios del XVIII estos términos reemplazaron gradualmente a Arbëria y Arbëreshë entre los albaneses. [17] [18] Estas dos expresiones se interpretan ampliamente como símbolo de los "Hijos de las Águilas" y la "Tierra de las Águilas". [19] [20]

La presencia de habitantes mesolíticos en Albania se ha evidenciado en varios yacimientos al aire libre que durante ese período estaban cerca de la costa del Adriático y en yacimientos rupestres. Los objetos mesolíticos encontrados en una cueva cerca de Xarrë incluyen objetos de sílex y jaspe junto con huesos fosilizados de animales, mientras que los descubrimientos en el monte Dajt comprenden herramientas de hueso y piedra similares a las de la cultura auriñaciense . [21] La era neolítica en Albania comenzó alrededor del 7000 a. C. y se evidencia en hallazgos que indican la domesticación de ovejas y cabras y la agricultura a pequeña escala. Una parte de la población neolítica puede haber sido la misma que la población mesolítica de los Balcanes meridionales, como en la cueva de Konispol , donde el estrato mesolítico coexiste con hallazgos neolíticos precerámicos. La cultura de la cerámica de Cardium aparece en la costa de Albania y en todo el Adriático después del 6500 a. C., mientras que los asentamientos del interior participaron en los procesos que formaron la cultura Starčevo . [22] Las minas de betún albanesas de Selenicë proporcionan evidencia temprana de la explotación de betún en Europa, que data del Neolítico Tardío en Albania (desde 5000 a. C.), cuando las comunidades locales lo usaban como pigmento para la decoración cerámica, impermeabilizante y adhesivo para reparar vasijas rotas. El betún de Selenicë circuló hacia el este de Albania desde principios del quinto milenio a. C. La primera evidencia de su exportación comercial al extranjero proviene del Neolítico y la Edad del Bronce en el sur de Italia . El betún de alta calidad de Selenicë se ha explotado a lo largo de todas las eras históricas desde el Neolítico Tardío hasta la actualidad. [23]

La indoeuropeización de Albania en el contexto de la IE-ización de los Balcanes occidentales comenzó después de 2800 a. C. La presencia de túmulos de la Edad del Bronce Temprano en las proximidades de la posterior Apolonia data de 2679 ± 174 cal BC (2852-2505 cal BC). Estos túmulos funerarios pertenecen a la expresión meridional de la cultura Adriático-Ljubljana (relacionada con la posterior cultura Cetina ) que se trasladó hacia el sur a lo largo del Adriático desde los Balcanes del norte. La misma comunidad construyó túmulos similares en Montenegro (Rakića Kuće) y el norte de Albania (Shtoj). [24] El primer hallazgo arqueogenético relacionado con la IE-ización de Albania involucra a un hombre con ascendencia predominantemente Yamnaya enterrado en un túmulo del noreste de Albania que data de 2663-2472 cal BC. [25] Durante la Edad del Bronce Medio, aparecen sitios y hallazgos de la cultura Cetina en Albania. La cultura Cetina se trasladó hacia el sur a través del Adriático desde el valle Cetina de Dalmacia . En Albania, los hallazgos de Cetina se concentran alrededor del sur del lago Shkodër y aparecen típicamente en cementerios de túmulos como en Shkrel y Shtoj y castros como Gajtan (Shkodër), así como en sitios de cuevas como Blaz, Nezir y Keputa (Albania central) y sitios de cuencas lacustres como Sovjan (sureste de Albania). [26]

El territorio incorporado de Albania estuvo históricamente habitado por pueblos indoeuropeos , entre ellos numerosas tribus ilirias y epirotas . También hubo varias colonias griegas . El territorio conocido como Iliria correspondía aproximadamente al área al este del mar Adriático en el mar Mediterráneo que se extendía al sur hasta la desembocadura del Vjosë . [27] [28] El primer relato de los grupos ilirios proviene del Periplo del mar Euxino , un texto griego escrito en el siglo IV a. C. [29] Los briges también estaban presentes en el centro de Albania, mientras que el sur estaba habitado por los caonios epirotas , cuya capital estaba en Fenicia . [29] [30] [31] Otras colonias como Apolonia y Epidamnos fueron establecidas por ciudades-estado griegas en la costa en el siglo VII a. C. [29] [32] [33]

Los taulanti ilirios eran una poderosa tribu iliria que se encontraba entre las primeras tribus registradas en la zona. Vivían en un área que corresponde a gran parte de la actual Albania. Junto con el gobernante dardaniano Clito , Glaucias , el gobernante del reino taulantiano, luchó contra Alejandro Magno en la batalla de Pelium en 335 a. C. Con el paso del tiempo, el gobernante de la antigua Macedonia, Casandro de Macedonia, capturó Apolonia y cruzó el río Genusus ( en albanés : Shkumbin ) en 314 a. C. Unos años más tarde, Glaucias sitió Apolonia y capturó la colonia griega de Epidamnos . [34]

La tribu iliria de los ardiaeos , centrada en Montenegro, gobernaba la mayor parte del territorio del norte de Albania. Su reino ardiaeo alcanzó su mayor extensión bajo el rey Agrón , hijo de Pleurato II . Agrón extendió su gobierno también sobre otras tribus vecinas. [35] Tras la muerte de Agrón en el 230 a. C., su esposa, Teuta , heredó el reino ardiaeo. Las fuerzas de Teuta extendieron sus operaciones más al sur hasta el mar Jónico. [36] En el 229 a. C., Roma declaró la guerra [37] al reino por saquear extensamente los barcos romanos. La guerra terminó con la derrota iliria en el 227 a. C. Teuta fue finalmente sucedido por Gentius en el 181 a. C. [38] Gentius se enfrentó a los romanos en el 168 a. C., iniciando la Tercera Guerra Iliria . El conflicto resultó en la conquista romana de la región en el 167 a. C. Los romanos dividieron la región en tres divisiones administrativas. [39]

El Imperio romano se dividió en el año 395 a la muerte de Teodosio I en un Imperio romano de Oriente y uno de Occidente , en parte debido a la creciente presión de las amenazas durante las invasiones bárbaras . Desde el siglo VI hasta el siglo VII, los eslavos cruzaron el Danubio y absorbieron en gran medida a los griegos, ilirios y tracios indígenas en los Balcanes ; por lo tanto, los ilirios fueron mencionados por última vez en los registros históricos en el siglo VII. [40] [41]

En el siglo XI, el Gran Cisma formalizó la ruptura de la comunión entre la Iglesia ortodoxa oriental y la Iglesia católica occidental , que se refleja en Albania a través del surgimiento de un norte católico y un sur ortodoxo. El pueblo albanés habitó el oeste del lago Ochrida y el valle superior del río Shkumbin y estableció el Principado de Líbano en 1190 bajo el liderazgo de Progon de Kruja . [42] El reino fue sucedido por sus hijos Gjin y Dhimitri.

Tras la muerte de Dhimiter, el territorio quedó bajo el gobierno del albanés-griego Gregorio Kamonas y posteriormente bajo el Golem de Kruja . [43] [44] [45] En el siglo XIII, el principado se disolvió. [46] [47] [48] Se considera que el Líbano fue el primer esbozo de un estado albanés, que mantuvo un estatus semiautónomo como extremo occidental del Imperio bizantino , bajo el Dukai bizantino de Epiro o lascáridas de Nicea . [49]

_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall'Orto,_12-Aug-2007_-_11_-_Maometto_II_assedia_Scutari.jpg/440px-Venezia_-_Ex_Scola_degli_albanesi_(sec._XV)_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall'Orto,_12-Aug-2007_-_11_-_Maometto_II_assedia_Scutari.jpg)

Hacia finales del siglo XII y principios del XIII, los serbios y los venecianos comenzaron a tomar posesión del territorio. [50] La etnogénesis de los albaneses es incierta; sin embargo, la primera mención indiscutible de los albaneses se remonta a registros históricos de 1079 o 1080 en una obra de Michael Attaliates , quien se refirió a los albaneses como participantes en una revuelta contra Constantinopla . [51] En este punto, los albaneses estaban completamente cristianizados.

Después de la disolución del Líbano, Carlos de Anjou concluyó un acuerdo con los gobernantes albaneses, prometiendo protegerlos y sus antiguas libertades. En 1272, estableció el Reino de Albania y conquistó regiones del Despotado de Epiro . El reino reclamó todo el territorio de Albania central desde Dirraquio a lo largo de la costa del mar Adriático hasta Butrinto . Una estructura política católica fue la base de los planes papales de difundir el catolicismo en la península de los Balcanes. Este plan también encontró el apoyo de Helena de Anjou , prima de Carlos de Anjou. Alrededor de 30 iglesias y monasterios católicos se construyeron durante su gobierno, principalmente en el norte de Albania. [52] Las luchas internas de poder dentro del Imperio bizantino en el siglo XIV permitieron al gobernante medieval más poderoso de los serbios, Stefan Dusan , establecer un imperio de corta duración que incluía toda Albania excepto Durrës. [50] En 1367, varios gobernantes albaneses establecieron el Despotado de Arta . Durante ese tiempo, se crearon varios principados albaneses , en particular el Principado de Albania , el Principado de Kastrioti , el Señorío de Berat y el Principado de Dukagjini . En la primera mitad del siglo XV, el Imperio otomano invadió la mayor parte de Albania y la Liga de Lezhë se mantuvo bajo el mando de Skanderbeg , que se convirtió en el héroe nacional de la historia medieval albanesa.

Con la caída de Constantinopla , el Imperio otomano continuó un largo período de conquista y expansión con sus fronteras adentrándose profundamente en el sudeste de Europa . Llegaron a la costa albanesa del mar Jónico en 1385 y erigieron sus guarniciones en el sur de Albania en 1415 y luego ocuparon la mayor parte de Albania en 1431. [53] [54] En consecuencia, miles de albaneses huyeron a Europa occidental, particularmente a Calabria , Nápoles , Ragusa y Sicilia , mientras que otros buscaron protección en las montañas a menudo inaccesibles de Albania . [55] [56] Los albaneses, como cristianos, eran considerados una clase inferior de personas y, como tales, estaban sujetos a fuertes impuestos, entre otros, por el sistema Devshirme que permitía al sultán recolectar un porcentaje requerido de adolescentes cristianos de sus familias para componer el jenízaro . [57] La conquista otomana también estuvo acompañada por el proceso gradual de islamización y la rápida construcción de mezquitas.

Una revolución próspera y duradera estalló después de la formación de la Liga de Lezhë hasta la caída de Shkodër bajo el liderazgo de Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg , quien derrotó consistentemente a los principales ejércitos otomanos liderados por los sultanes Murad II y Mehmed II . Skanderbeg logró unificar varios de los principados albaneses, entre ellos los arianitis , dukagjinis , zaharias y thopias , y establecer una autoridad centralizada sobre la mayoría de los territorios no conquistados, convirtiéndose en el Señor de Albania . [58] La expansión del Imperio otomano se detuvo durante el tiempo en que las fuerzas de Skanderbeg resistieron, y se le atribuye ser una de las principales razones del retraso de la expansión otomana en Europa occidental , dando a los principados italianos más tiempo para prepararse mejor para la llegada otomana . [59] Sin embargo, el fracaso de la mayoría de las naciones europeas, con la excepción de Nápoles, en brindarle apoyo, junto con el fracaso de los planes del Papa Pío II de organizar una cruzada prometida contra los otomanos, significó que ninguna de las victorias de Skanderbeg impidió permanentemente que los otomanos invadieran los Balcanes occidentales. [60] [61]

A pesar de su brillantez como líder militar, las victorias de Skanderbeg sólo retrasaron las conquistas finales. Las constantes invasiones otomanas causaron una enorme destrucción en Albania, reduciendo enormemente la población y destruyendo rebaños de ganado y cultivos. Aparte de la rendición, no había forma posible de que Skanderbeg pudiera detener las invasiones otomanas a pesar de sus éxitos contra ellas. Su mano de obra y sus recursos eran insuficientes, lo que le impidió ampliar los esfuerzos de guerra y expulsar a los turcos de las fronteras albanesas. Por lo tanto, Albania estaba condenada a enfrentar una serie interminable de ataques otomanos hasta que finalmente cayó años después de su muerte. [62]

Cuando los otomanos se afianzaron en la región, las ciudades albanesas se organizaron en cuatro sanjaks principales . El gobierno fomentó el comercio estableciendo una importante colonia judía de refugiados que huían de la persecución en España. La ciudad de Vlorë vio pasar por sus puertos mercancías importadas de Europa, como terciopelos, artículos de algodón, mohairs, alfombras, especias y cuero de Bursa y Constantinopla . Algunos ciudadanos de Vlorë incluso tenían socios comerciales en toda Europa. [63]

El fenómeno de la islamización entre los albaneses se extendió principalmente a partir del siglo XVII y continuó hasta el siglo XVIII. [64] El Islam les ofrecía igualdad de oportunidades y progreso dentro del Imperio Otomano. Sin embargo, los motivos de la conversión eran, según algunos estudiosos, diversos según el contexto, aunque la falta de material de referencia no ayuda a la hora de investigar estas cuestiones. [64] Debido a la creciente represión del catolicismo, la mayoría de los albaneses católicos se convirtieron en el siglo XVII, mientras que los albaneses ortodoxos siguieron su ejemplo principalmente en el siglo siguiente.

Los albaneses eran considerados estratégicamente importantes, por lo que constituían una proporción significativa del ejército y la burocracia otomanos . Muchos musulmanes albaneses alcanzaron importantes posiciones políticas y militares y contribuyeron culturalmente al mundo musulmán en general . [64] Disfrutando de esta posición privilegiada, ocuparon varios altos cargos administrativos con más de dos docenas de grandes visires albaneses . Otros incluían a miembros de la prominente familia Köprülü , Zagan Pasha , Muhammad Ali de Egipto y Ali Pasha de Tepelena . Además, dos sultanes, Bayaceto II y Mehmed III , ambos tenían madres de origen albanés. [63] [65] [66]

El Renacimiento albanés fue un período que tuvo sus raíces a fines del siglo XVIII y continuó hasta el siglo XIX, durante el cual el pueblo albanés reunió fuerza espiritual e intelectual para una vida cultural y política independiente dentro de una nación independiente . La cultura albanesa moderna también floreció, especialmente la literatura y las artes albanesas , y con frecuencia estuvo vinculada a las influencias del Romanticismo y los principios de la Ilustración . [68] Antes del surgimiento del nacionalismo , las autoridades otomanas suprimieron cualquier expresión de unidad o conciencia nacional por parte del pueblo albanés.

La victoria de Rusia sobre el Imperio Otomano tras las guerras ruso-otomanas dio lugar a la firma del Tratado de San Stefano , que asignaba las tierras pobladas por albaneses a sus vecinos eslavos y griegos. Sin embargo, el Reino Unido y el Imperio austrohúngaro bloquearon el acuerdo y provocaron el Tratado de Berlín . A partir de este punto, los albaneses comenzaron a organizarse con el objetivo de proteger y unir las tierras pobladas por albaneses en una nación unitaria, lo que llevó a la formación de la Liga de Prizren . La liga contó inicialmente con el apoyo de las autoridades otomanas, cuya posición se basaba en la solidaridad religiosa del pueblo musulmán y los terratenientes relacionados con la administración otomana . Favorecieron y protegieron la solidaridad musulmana y llamaron a la defensa de las tierras musulmanas, lo que al mismo tiempo constituyó la razón para el título de la liga Comité de los Musulmanes Verdaderos . [69]

Aproximadamente 300 musulmanes participaron en la asamblea compuesta por delegados de Bosnia, el administrador del Sanjak de Prizren como representantes de las autoridades centrales y ningún delegado del Vilayet de Scutari . [70] Firmada por solo 47 diputados musulmanes, la liga emitió el Kararname que contenía una proclamación de que los pueblos del norte de Albania, Epiro y Bosnia y Herzegovina están dispuestos a defender la integridad territorial del Imperio Otomano por todos los medios posibles contra las tropas de Bulgaria , Serbia y Montenegro . [71]

Las autoridades otomanas cancelaron su ayuda cuando la liga, bajo Abdyl Frashëri , se centró en trabajar por la autonomía albanesa y solicitó la fusión de cuatro vilayatos , incluidos Kosovo , Shkodër , Monastir y Ioannina , en un vilayato unificado, el Vilayeto albanés . La liga utilizó la fuerza militar para evitar la anexión de las áreas de Plav y Gusinje asignadas a Montenegro. Después de varias batallas exitosas con las tropas montenegrinas, como la batalla de Novšiće , la liga se vio obligada a retirarse de sus regiones en disputa. La liga fue derrotada más tarde por el ejército otomano enviado por el sultán. [72]

.jpg/440px-Ismail_Qemali_(portrait).jpg)

Albania declaró su independencia del Imperio otomano el 28 de noviembre de 1912, acompañada por el establecimiento del Senado y el Gobierno por la Asamblea de Vlorë el 4 de diciembre de 1912. [73] [74] [75] [76] Su soberanía fue reconocida por la Conferencia de Londres . El 29 de julio de 1913, el Tratado de Londres delineó las fronteras del país y sus vecinos, dejando a muchos albaneses fuera de Albania, predominantemente divididos entre Montenegro , Serbia y Grecia . [77]

La Comisión Internacional de Control , con sede en Vlorë, se estableció el 15 de octubre de 1913 para encargarse de la administración de Albania hasta que sus propias instituciones políticas estuvieran en orden. [78] [79] La Gendarmería Internacional se estableció como la primera agencia de aplicación de la ley del Principado de Albania . En noviembre, los primeros miembros de la gendarmería llegaron al país. El príncipe de Albania, Guillermo de Wied (Princ Vilhelm Vidi), fue elegido como el primer príncipe del principado. [80] El 7 de marzo, llegó a la capital provisional de Durrës y comenzó a organizar su gobierno, nombrando a Turhan Pasha Përmeti para formar el primer gabinete albanés.

En noviembre de 1913, las fuerzas pro-otomanas albanesas habían ofrecido el trono de Albania al ministro de guerra otomano de origen albanés, Ahmed Izzet Pasha . [81] Los campesinos pro-otomanos creían que el nuevo régimen era una herramienta de las seis grandes potencias cristianas y de los terratenientes locales, que poseían la mitad de la tierra cultivable. [82]

En febrero de 1914, la población griega local proclamó en Gjirokastër la República Autónoma del Epiro del Norte contra la incorporación a Albania. Esta iniciativa duró poco y en 1921 las provincias del sur se incorporaron al Principado de Albania. [83] [84] Mientras tanto, la revuelta de los campesinos albaneses contra el nuevo régimen estalló bajo el liderazgo del grupo de clérigos musulmanes reunidos en torno a Essad Pasha Toptani , que se autoproclamó el salvador de Albania y del Islam. [85] [86] Para ganar el apoyo de los voluntarios católicos de Mirdita del norte de Albania, el príncipe Wied nombró a su líder, Prênk Bibë Doda , ministro de Asuntos Exteriores del Principado de Albania. En mayo y junio de 1914, la Gendarmería Internacional se unió a Isa Boletini y sus hombres, en su mayoría de Kosovo , [87] y los rebeldes derrotaron a los católicos del norte de Mirdita , capturando la mayor parte de Albania Central a fines de agosto de 1914. [88] El régimen del Príncipe Wied colapsó y abandonó el país el 3 de septiembre de 1914. [89]

El período de entreguerras en Albania estuvo marcado por persistentes dificultades económicas y sociales, inestabilidad política e intervenciones extranjeras. [90] [91] Después de la Primera Guerra Mundial , Albania carecía de un gobierno establecido y de fronteras reconocidas internacionalmente, lo que la hacía vulnerable a entidades vecinas como Grecia, Italia y Yugoslavia, todas las cuales buscaban expandir su influencia. [90] Esto condujo a una incertidumbre política, resaltada en 1918 cuando el Congreso de Durrës solicitó la protección de la Conferencia de Paz de París, pero le fue denegada, lo que complicó aún más la posición de Albania en el escenario internacional. Las tensiones territoriales aumentaron cuando Yugoslavia, particularmente Serbia, buscó el control del norte de Albania, mientras que Grecia apuntaba al dominio en el sur de Albania. La situación se deterioró en 1919 cuando los serbios lanzaron ataques contra los habitantes albaneses, entre otros en Gusinje y Plav , lo que resultó en masacres y desplazamientos a gran escala . [90] [92] [93] Mientras tanto, la influencia italiana continuó expandiéndose durante este tiempo, impulsada por intereses económicos y ambiciones políticas. [91] [94]

Fan Noli , conocido por su idealismo , se convirtió en primer ministro en 1924, con la visión de instituir un gobierno constitucional de estilo occidental, abolir el feudalismo, contrarrestar la influencia italiana y mejorar sectores críticos, incluyendo la infraestructura, la educación y la atención médica. [90] Se enfrentó a la resistencia de antiguos aliados, que habían ayudado a derrocar a Zog del poder, y luchó por asegurar la ayuda extranjera para implementar su agenda. La decisión de Noli de establecer lazos diplomáticos con la Unión Soviética, un adversario de la élite serbia, encendió acusaciones de bolchevismo desde Belgrado. [90] Esto a su vez condujo a una mayor presión de Italia y culminó con la restauración de Zog a la autoridad. En 1928, Zog hizo la transición de Albania de una república a una monarquía que obtuvo el respaldo de la Italia fascista , y Zog asumió el título de Rey Zog I. Los cambios constitucionales clave disolvieron el Senado y establecieron una Asamblea Nacional unicameral, preservando al mismo tiempo los poderes autoritarios de Zog. [90]

En 1939, Italia bajo Benito Mussolini lanzó una invasión militar de Albania, lo que resultó en el exilio de Zog y la creación de un protectorado italiano . [95] [96] A medida que avanzaba la Segunda Guerra Mundial , Italia apuntó a expandir su dominio territorial en los Balcanes, incluidas las reclamaciones territoriales en regiones de Grecia ( Chameria ), Macedonia, Montenegro y Kosovo. Estas ambiciones sentaron las bases de la Gran Albania , que tenía como objetivo unir todas las áreas con poblaciones de mayoría albanesa en un solo país. [97] En 1943, cuando el control de Italia declinó, la Alemania nazi asumió el control de Albania, sometiendo a los albaneses a trabajos forzados, explotación económica y represión bajo el dominio alemán . [98] La marea cambió en 1944 cuando las fuerzas partisanas albanesas, bajo el liderazgo de Enver Hoxha y otros líderes comunistas, liberaron con éxito a Albania de la ocupación alemana. [99]

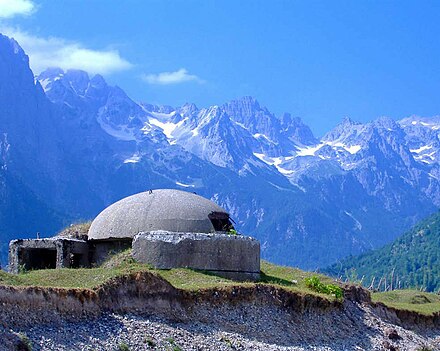

El establecimiento de la República Popular de Albania bajo el liderazgo de Enver Hoxha fue una época significativa en la historia moderna de Albania. [100] El régimen de Hoxha abrazó ideologías marxistas-leninistas e implementó políticas autoritarias , incluyendo la prohibición de prácticas religiosas, severas restricciones a los viajes y la abolición de los derechos de propiedad privada. [101] También se definió por un patrón persistente de purgas, represión extensa, casos de traición y hostilidad a las influencias externas. [101] Cualquier forma de oposición o resistencia a su gobierno fue respondida con consecuencias rápidas y severas, como el exilio interno, el encarcelamiento prolongado y la ejecución. [101] El régimen enfrentó una multitud de desafíos, incluyendo pobreza generalizada, analfabetismo, crisis de salud y desigualdad de género. [99] En respuesta, Hoxha inició una iniciativa de modernización destinada a lograr la liberación económica y social y transformar Albania en una sociedad industrial. [99] El régimen dio alta prioridad a la diversificación de la economía a través de la industrialización al estilo soviético, el desarrollo integral de infraestructura como la introducción de un sistema ferroviario transformador , la expansión de los servicios de educación y atención de salud, la eliminación del analfabetismo de los adultos y avances específicos en áreas como los derechos de las mujeres. [102] [103] [104] [105]

La historia diplomática de Albania bajo Hoxha se caracterizó por notables conflictos. [90] Inicialmente alineada con Yugoslavia como estado satélite, la relación se deterioró cuando Yugoslavia intentó incorporar a Albania dentro de su territorio. [90] Posteriormente, Albania estableció relaciones con la Unión Soviética y entabló acuerdos comerciales con otros países de Europa del Este, pero experimentó desacuerdos sobre las políticas soviéticas, lo que llevó a tensas relaciones con Moscú y a la separación diplomática en 1961. [90] Simultáneamente, las tensiones con Occidente aumentaron debido a la negativa de Albania a celebrar elecciones libres y las acusaciones de apoyo occidental a los levantamientos anticomunistas . La asociación duradera de Albania fue con China; se puso del lado de Pekín durante el conflicto chino-soviético , lo que resultó en la ruptura de los lazos con la Unión Soviética y la retirada del Pacto de Varsovia en respuesta a la invasión de Checoslovaquia en 1968. Pero sus relaciones se estancaron en 1970, lo que llevó a ambos a reevaluar su compromiso, y Albania redujo activamente su dependencia de China. [90]

Bajo el régimen de Hoxha, Albania sufrió una campaña generalizada dirigida contra el clero religioso de diversas confesiones, que resultó en persecuciones públicas y ejecuciones, especialmente dirigidas contra musulmanes, católicos romanos y seguidores de la Iglesia ortodoxa oriental. [90] En 1946, las propiedades religiosas sufrieron una nacionalización, coincidiendo con el cierre o la transformación de las instituciones religiosas en diversos fines. [90] Esto culminó en 1976, cuando Albania se convirtió en el primer estado constitucionalmente ateo del mundo. [107] Bajo este régimen, los albaneses se vieron obligados a renunciar a sus creencias religiosas, adoptar un estilo de vida secular y abrazar la ideología socialista. [90] [107]

Después de cuatro décadas de comunismo emparejadas con las revoluciones de 1989 , Albania fue testigo de un notable aumento del activismo político, particularmente entre los estudiantes, lo que llevó a una transformación en el orden imperante. Después de las primeras elecciones multipartidistas de 1991 , el partido comunista mantuvo un bastión en el parlamento hasta su derrota en las elecciones parlamentarias de 1992 dirigidas por el Partido Democrático . [108] Se dedicaron considerables recursos económicos y financieros a esquemas piramidales que fueron ampliamente apoyados por el gobierno. Los esquemas arrasaron entre una sexta y una tercera parte de la población del país. [109] [110] A pesar de las advertencias del Fondo Monetario Internacional , Sali Berisha defendió los esquemas como grandes empresas de inversión, lo que llevó a más personas a redirigir sus remesas y vender sus casas y ganado por efectivo para depositarlos en los esquemas. [111]

Los planes empezaron a desmoronarse a finales de 1996, lo que llevó a muchos de los inversores a sumarse a protestas inicialmente pacíficas contra el gobierno, solicitando la devolución de su dinero. Las protestas se tornaron violentas en febrero de 1997, cuando las fuerzas gubernamentales respondieron disparando contra los manifestantes. En marzo, la policía y la Guardia Republicana desertaron, dejando sus arsenales abiertos, que fueron vaciados rápidamente por milicias y bandas criminales. La guerra civil resultante provocó una ola de evacuaciones de extranjeros y refugiados. [112]

La crisis llevó a Aleksandër Meksi y Sali Berisha a dimitir de sus cargos tras las elecciones generales. En abril de 1997, la Operación Alba , una fuerza de mantenimiento de la paz de la ONU dirigida por Italia, entró en Albania con dos objetivos: ayudar a la evacuación de expatriados y asegurar el terreno para las organizaciones internacionales. La principal organización internacional implicada fue el elemento multinacional de la Policía albanesa de la Unión Europea Occidental , que trabajó con el gobierno para reestructurar el sistema judicial y, al mismo tiempo, la policía albanesa.

.jpg/440px-2019-11-26_Mamurras,_Albania_M6.4_earthquake_shakemap_(USGS).jpg)

Después de que su sistema comunista se desintegrara, Albania se embarcó en un camino activo hacia la occidentalización con la ambición de obtener la membresía en la Unión Europea (UE) y la Organización del Tratado del Atlántico Norte (OTAN). [114] Un hito notable se alcanzó en 2009, cuando el país logró la membresía en la OTAN, marcando un logro pionero entre las naciones del sudeste de Europa . [115] [116] En adhesión a su visión de una mayor integración en la UE, solicitó formalmente la membresía el 28 de abril de 2009. [117] Otro hito se alcanzó el 24 de junio de 2014, cuando al país se le concedió el estatus oficial de candidato . [118]

Edi Rama, del Partido Socialista , ganó las elecciones parlamentarias de 2013 y 2017. Como primer ministro , implementó numerosas reformas centradas en la modernización de la economía , así como en la democratización de las instituciones estatales, incluido el poder judicial y la aplicación de la ley . El desempleo ha disminuido de manera constante y Albania ha logrado la cuarta tasa de desempleo más baja de los Balcanes. [119] Rama también ha colocado la igualdad de género en el centro de su agenda; desde 2017, casi el 50% de los ministros han sido mujeres, el mayor número de mujeres en el cargo en la historia del país. [120] Durante las elecciones parlamentarias de 2021 , el gobernante Partido Socialista liderado por Rama consiguió su tercera victoria consecutiva, ganando casi la mitad de los votos y suficientes escaños en el parlamento para gobernar en solitario. [121] [122]

El 26 de noviembre de 2019, un terremoto de magnitud 6,4 devastó Albania, con epicentro a unos 16 km (10 mi) al suroeste de la ciudad de Mamurras . [123] El temblor se sintió en Tirana y en lugares tan lejanos como Taranto , Italia, y Belgrado , Serbia, mientras que las zonas más afectadas fueron la ciudad costera de Durrës y el pueblo de Kodër-Thumanë . [124] La respuesta integral al terremoto incluyó una importante ayuda humanitaria de la diáspora albanesa y de varios países de todo el mundo . [125]

El 9 de marzo de 2020, se confirmó que la COVID-19 se había propagado a Albania. [126] [127] De marzo a junio de 2020, el gobierno declaró el estado de emergencia como medida para limitar la propagación del virus. [128] [129] [130] La campaña de vacunación contra la COVID-19 del país comenzó el 11 de enero de 2021, pero al 11 de agosto de 2021, el número total de vacunas administradas en Albania era de 1.280.239 dosis. [131] [132]

El 21 de septiembre de 2024, se informó que el primer ministro de Albania, Edi Rama , estaba planeando crear el Estado Soberano de la Orden Bektashi , un microestado soberano para la Orden dentro de la capital de Albania, Tirana. [133]

Albania se encuentra a orillas del mar Mediterráneo en la península de los Balcanes en el sur y sureste de Europa , y tiene una superficie de 28.748 km² ( 11.100 millas cuadradas). [134] Limita con el mar Adriático al oeste, Montenegro al noroeste, Kosovo al noreste, Macedonia del Norte al este, Grecia al sur y el mar Jónico al suroeste. Se encuentra entre las latitudes 42° y 39° N y las longitudes 21° y 19° E. Las coordenadas geográficas incluyen Vërmosh a 42° 35' 34" de latitud norte como el punto más septentrional, Konispol a 39° 40' 0" de latitud norte como el más meridional, Sazan a 19° 16' 50" de longitud este como el más occidental, y Vërnik a 21° 1' 26" de longitud este como el más oriental. [135] El monte Korab , que se eleva a 2764 m (9068,24 pies) sobre el Adriático , es el punto más alto, mientras que el mar Mediterráneo, a 0 m (0,00 pies), es el más bajo. El país se extiende 148 km (92 mi) de este a oeste y alrededor de 340 km (211 mi) de norte a sur.

Albania tiene un paisaje diverso y variado con montañas y colinas que recorren su territorio en varias direcciones. El país alberga extensas cadenas montañosas, incluidos los Alpes albaneses en el norte, las montañas Korab en el este, los montes Pindus en el sureste, los montes Ceraunian en el suroeste y los montes Skanderbeg en el centro. En el noroeste se encuentra el lago de Shkodër , el lago más grande del sur de Europa. [136] Hacia el sureste emerge el lago de Ohrid , uno de los lagos más antiguos del mundo que existen de forma continua. [137] Más al sur, la extensión incluye el Gran y Pequeño Lago de Prespa , algunos de los lagos más altos de los Balcanes. Los ríos nacen principalmente en el este y desembocan en los mares Adriático y Jónico. El río más largo del país, medido desde la desembocadura hasta la fuente, es el Drin , que comienza en la confluencia de sus dos cabeceras, el Drin Negro y el Drin Blanco . De particular preocupación es el Vjosë , uno de los últimos grandes sistemas fluviales intactos de Europa.

En Albania, la cubierta forestal representa alrededor del 29,% de la superficie total del país, lo que equivale a 788.900 hectáreas (ha) de bosque en 2020, frente a las 788.800 hectáreas (ha) de 1990. Del bosque que se regenera naturalmente, se informó que el 11% era bosque primario (que consiste en especies de árboles nativos sin indicaciones claramente visibles de actividad humana) y alrededor del 0% de la superficie forestal se encontraba dentro de áreas protegidas. Para el año 2015, se informó que el 97% de la superficie forestal era de propiedad pública , el 3% de propiedad privada y el 0% con propiedad indicada como otra o desconocida. [138] [139]

El clima de Albania exhibe un nivel distinguido de variabilidad y diversidad debido a las diferencias de latitud, longitud y altitud. [140] [141] Albania experimenta un clima mediterráneo y continental , caracterizado por la presencia de cuatro estaciones distintas. [142] Según la clasificación de Köppen , Albania abarca cinco tipos climáticos primarios, que abarcan desde el mediterráneo y subtropical en la mitad occidental hasta el oceánico , continental y subártico en la mitad oriental del país. [143] Las regiones costeras a lo largo de los mares Adriático y Jónico en Albania son reconocidas como las áreas más cálidas, mientras que las regiones norte y este que abarcan los Alpes albaneses y las montañas Korab son reconocidas como las áreas más frías del país. [144] A lo largo del año, las temperaturas mensuales promedio fluctúan, desde −1 °C (30 °F ) durante los meses de invierno hasta 21,8 °C (71,2 °F) en los meses de verano. Cabe destacar que la temperatura más alta registrada de 43,9 °C (111,0 °F) se observó en Kuçovë el 18 de julio de 1973, mientras que la temperatura más baja de −29 °C (−20 °F) se registró en Shtyllë, Librazhd el 9 de enero de 2017. [145] [146]

Albania recibe la mayor parte de las precipitaciones en los meses de invierno y menos en los meses de verano. [141] La precipitación media es de unos 1.485 milímetros (58,5 pulgadas). [144] La precipitación media anual varía entre 600 y 3.000 milímetros (24 y 118 pulgadas) dependiendo de la ubicación geográfica. [142] Las tierras altas del noroeste y sureste reciben la cantidad más intensa de precipitaciones, mientras que las tierras altas del noreste y suroeste, así como las tierras bajas occidentales , la cantidad más limitada. [144] Los Alpes albaneses en el extremo norte del país se consideran una de las regiones más húmedas de Europa, recibiendo al menos 3.100 mm (122,0 pulgadas) de lluvia al año. [144] Se descubrieron cuatro glaciares dentro de estas montañas a una altitud relativamente baja de 2.000 metros (6.600 pies), lo que es extremadamente raro para una latitud tan meridional. [147]

.jpg/440px-Golden_eagle_(13434882845).jpg)

Albania, un punto crítico de biodiversidad , posee una biodiversidad excepcionalmente rica y contrastante debido a su ubicación geográfica en el centro del mar Mediterráneo y la gran diversidad de sus condiciones climáticas , geológicas e hidrológicas . [148] [149] Debido a su lejanía, las montañas y colinas de Albania están dotadas de bosques, árboles y pastos que son esenciales para la vida de una amplia variedad de animales, entre otros, para dos de las especies más amenazadas del país, el lince y el oso pardo , así como el gato montés , el lobo gris , el zorro rojo , el chacal dorado , el buitre egipcio y el águila real , este último constituyendo el animal nacional del país. [150] [151] [152] [153]

Los estuarios, humedales y lagos son extraordinariamente importantes para el flamenco común , el cormorán pigmeo y el ave extremadamente rara y quizás la más emblemática del país, el pelícano dálmata . [154] De particular importancia son la foca monje del Mediterráneo , la tortuga boba y la tortuga verde que suelen anidar en las aguas costeras y las orillas del país.

En términos fitogeográficos , Albania forma parte del Reino Boreal y se extiende específicamente dentro de la provincia Iliria de la Región Circumboreal y Mediterránea . Su territorio se puede subdividir en cuatro ecorregiones terrestres del reino Paleártico , a saber, dentro de los bosques caducifolios ilirios , los bosques mixtos de los Balcanes , los bosques mixtos de los Montes Pindus y los bosques mixtos de los Montes Dináricos . [155] [156]

En Albania se pueden encontrar aproximadamente 3.500 especies diferentes de plantas, lo que se debe principalmente a su carácter mediterráneo y euroasiático . El país mantiene una vibrante tradición de prácticas medicinales y a base de hierbas. Al menos 300 plantas que crecen localmente se utilizan en la preparación de hierbas y medicinas. [157] Los árboles dentro de los bosques son principalmente abetos , robles , hayas y pinos .

Albania ha participado activamente en numerosos acuerdos y convenciones internacionales destinados a fortalecer su compromiso con la preservación y la gestión sostenible de la diversidad biológica. Desde 1994, el país es parte del Convenio sobre la Diversidad Biológica (CDB) y sus Protocolos asociados de Cartagena y Nagoya . [158] Para cumplir con estos compromisos, ha desarrollado e implementado una Estrategia y Plan de Acción Nacional sobre Biodiversidad (NBSAP) integral. [158] Además, Albania ha establecido una asociación con la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza (UICN), avanzando en sus esfuerzos de conservación tanto a escala nacional como internacional. Guiado por la UICN, el país ha logrado avances sustanciales en la fundación de áreas protegidas dentro de sus fronteras, que abarcan 12 parques nacionales , entre otros Butrint , Karaburun-Sazan , Llogara , Prespa y Vjosa . [159]

Como signatario de la Convención de Ramsar , Albania ha otorgado un reconocimiento especial a cuatro humedales, designándolos como Humedales de Importancia Internacional, incluidos Buna - Shkodër , Butrint , Karavasta y Prespa . [160] La dedicación del país a la protección se extiende más allá de la esfera de la Red Mundial de Reservas de la Biosfera de la UNESCO , que opera en el marco del Programa sobre el Hombre y la Biosfera , evidenciado por su participación en la Reserva de la Biosfera Transfronteriza Ohrid-Prespa . [161] [162] Además, Albania alberga dos sitios naturales del Patrimonio Mundial , que abarcan la región de Ohrid y tanto el río Gashi como Rrajca como parte de los bosques de hayas antiguos y primigenios de los Cárpatos y otras regiones de Europa . [163]

.jpg/440px-A_fishermen_house_in_Karavasta_Lagoon_(Divjakë-Karavasta_National_Park).jpg)

Las áreas protegidas de Albania son áreas designadas y administradas por el gobierno albanés . Hay 12 parques nacionales , 4 sitios ramsar , 1 reserva de la biosfera y 786 otros tipos de reservas de conservación en Albania. [159] [164] Ubicado en el norte, el Parque Nacional de los Alpes albaneses, que comprende el antiguo Parque Nacional de Theth y el Parque Nacional del Valle de Valbonë , está rodeado por los imponentes picos de los Alpes albaneses . En el este, partes de las escarpadas montañas de Korab , Nemërçka y Shebenik se conservan dentro de los límites del Parque Nacional de Fir de Hotovë-Dangëlli , el Parque Nacional de Shebenik y el Parque Nacional de Prespa , este último abarcando la parte de Albania de los Grandes y Pequeños Lagos de Prespa .

Al sur, los montes Ceraunianos definen la costa albanesa del mar Jónico , dando forma al paisaje del Parque Nacional de Llogara , que se extiende hasta la península de Karaburun , formando el Parque Marino Karaburun-Sazan . Más al sur se encuentra el Parque Nacional de Butrint , que ocupa una península rodeada por el lago de Butrint y el canal de Vivari . Al oeste, extendiéndose a lo largo de la costa albanesa del mar Adriático , el Parque Nacional Divjakë-Karavasta cuenta con la extensa laguna de Karavasta , uno de los sistemas lagunares más grandes del mar Mediterráneo. Cabe destacar que el primer parque nacional de río salvaje de Europa, el Parque Nacional Vjosa , salvaguarda el río Vjosa y sus principales afluentes, que se origina en los montes Pindus y fluye hacia el mar Adriático. El Parque Nacional de las Montañas Dajti , el Parque Nacional de las Montañas Lurë-Dejë y el Parque Nacional de las Montañas Tomorr protegen el terreno montañoso del centro de Albania, incluidas las montañas Tomorr y Skanderbeg .

Los problemas ambientales en Albania abarcan en particular la contaminación del aire y del agua , los impactos del cambio climático , las deficiencias en la gestión de residuos , la pérdida de biodiversidad y el imperativo de la conservación de la naturaleza . [165] [166] Se prevé que el cambio climático ejerza impactos significativos en la calidad de vida en Albania. [167] El país está reconocido como vulnerable a los impactos del cambio climático , ocupando el puesto 79 entre 181 países en el Índice de Adaptación Global de Notre Dame de 2020. [168] Los factores que explican la vulnerabilidad del país a los riesgos del cambio climático incluyen peligros geológicos e hidrológicos , incluidos terremotos, inundaciones, incendios, deslizamientos de tierra, lluvias torrenciales, erosión fluvial y costera. [169] [170]

Como parte del Protocolo de Kioto y del Acuerdo de París , Albania se ha comprometido a reducir las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero en un 45% y lograr la neutralidad de carbono para 2050, lo que, junto con las políticas nacionales, ayudará a mitigar los impactos del cambio climático. [171] El país tiene un desempeño moderado y en mejora en el Índice de Desempeño Ambiental con una clasificación general de 62 de 180 países en 2022. [172] Sin embargo, la clasificación de Albania ha disminuido desde su ubicación más alta en la posición 15 en el Índice de Desempeño Ambiental de 2012. [173] En 2019, Albania tuvo una puntuación media en el Índice de Integridad del Paisaje Forestal de 6,77 de 10, lo que la situó en el puesto 64 a nivel mundial de 172 países. [174]

Desde que declaró su independencia en 1912, Albania ha experimentado una importante transformación política, atravesando distintos períodos que incluyeron un gobierno monárquico, un régimen comunista y el eventual establecimiento de un orden democrático. [175] En 1998, Albania pasó a ser una república constitucional parlamentaria soberana , lo que marcó un hito fundamental en su evolución política. [176] Su estructura de gobierno opera bajo una constitución que sirve como el documento principal del país. [177] La constitución se basa en el principio de la separación de poderes , con tres brazos de gobierno que abarcan el legislativo encarnado en el Parlamento , el ejecutivo dirigido por el Presidente como jefe ceremonial de estado y el Primer Ministro como jefe funcional de gobierno , y el poder judicial con una jerarquía de tribunales, incluidos los tribunales constitucional y supremo , así como múltiples tribunales de apelación y administrativos . [176]

El sistema jurídico de Albania está estructurado para proteger los derechos políticos de su población, independientemente de su afiliación étnica, lingüística, racial o religiosa. [176] [178] A pesar de estos principios, existen importantes preocupaciones en materia de derechos humanos en Albania que exigen atención. [179] Estas preocupaciones incluyen cuestiones relacionadas con la independencia del poder judicial, la ausencia de un sector de medios de comunicación libre y el persistente problema de la corrupción en varios órganos gubernamentales, agencias de aplicación de la ley y otras instituciones. [179] A medida que Albania sigue su camino hacia la adhesión a la UE, se están realizando esfuerzos activos para lograr mejoras sustanciales en estas áreas para alinearse con los criterios y estándares de la UE. [178]

Tras décadas de aislamiento durante el comunismo, Albania ha adoptado una orientación de política exterior centrada en la cooperación activa y la participación en los asuntos internacionales. En el centro de la política exterior de Albania se encuentra un conjunto de objetivos, que abarcan el compromiso de proteger su soberanía e integridad territorial, el cultivo de lazos diplomáticos con otros países, la defensa del reconocimiento internacional de Kosovo , la atención de las preocupaciones relacionadas con la expulsión de los albaneses de Cham , la búsqueda de la integración euroatlántica y la protección de los derechos de los albaneses en Kosovo , Grecia , Italia , Montenegro , Macedonia del Norte , Serbia y la diáspora . [181]

Los asuntos exteriores de Albania subrayan la dedicación del país a la estabilidad regional y la integración en las principales instituciones internacionales. [182] Albania se convirtió en miembro de las Naciones Unidas (ONU) en 1955, poco después de salir de un período de aislamiento durante la era comunista. [183] El país alcanzó un logro importante en su política exterior al asegurar la membresía en la Organización del Tratado del Atlántico Norte (OTAN) en 2009. [184] [185] Desde que obtuvo el estatus de candidato en 2014, el país también se ha embarcado en una agenda de reforma integral para alinearse con los estándares de adhesión a la Unión Europea (UE), con el objetivo de convertirse en un estado miembro de la UE. [118]

Albania y Kosovo mantienen una relación fraternal fortalecida por sus importantes vínculos culturales, étnicos e históricos. [186] Ambos países fomentan lazos diplomáticos duraderos, y Albania apoya activamente los esfuerzos de desarrollo e integración internacional de Kosovo. [186] Su contribución fundamental al camino de Kosovo hacia la independencia se ve subrayada por su temprano reconocimiento de la soberanía de Kosovo en 2008. [187] Además, ambos gobiernos celebran reuniones conjuntas anuales, como lo demuestra la reunión inaugural en 2014, que sirve como plataforma oficial para mejorar la cooperación bilateral y reforzar su compromiso conjunto con políticas que promuevan la estabilidad y la prosperidad de la región albanesa en general. [186]

_break_ground_on_a_new_checkpoint_in_the_district_of_Spin_Boldak,_Kandahar_province,_Afghanistan,_March_25,_2013_130325-A-MX357-127.jpg/440px-thumbnail.jpg)

Las Fuerzas Armadas de Albania están formadas por fuerzas terrestres , aéreas y navales y constituyen las fuerzas militares y paramilitares del país. Están dirigidas por un comandante en jefe bajo la supervisión del Ministerio de Defensa y por el Presidente como comandante supremo durante la guerra. Sin embargo, en tiempos de paz sus poderes son ejercidos por el Primer Ministro y el Ministro de Defensa . [188]

El objetivo principal de las fuerzas armadas de Albania es la defensa de la independencia, la soberanía y la integridad territorial del país, así como la participación en operaciones humanitarias, de combate, no combativas y de apoyo a la paz. [188] El servicio militar es voluntario desde 2010 y la edad mínima legal para el servicio es de 19 años. [189] [190]

Albania se ha comprometido a aumentar su participación en operaciones multinacionales. [191] Desde la caída del comunismo, el país ha participado en seis misiones internacionales, pero sólo en una misión de las Naciones Unidas en Georgia , donde envió tres observadores militares. Desde febrero de 2008, Albania ha participado oficialmente en la Operación Active Endeavor de la OTAN en el mar Mediterráneo . [192] Fue invitada a unirse a la OTAN el 3 de abril de 2008, y se convirtió en miembro de pleno derecho el 2 de abril de 2009. [193]

Albania redujo el número de tropas activas de 65.000 en 1988 a 14.500 en 2009. [194] [195] El ejército ahora consiste principalmente en una pequeña flota de aviones y buques de guerra. Aumentar el presupuesto militar fue una de las condiciones más importantes para la integración a la OTAN . En 1996, el gasto militar se estimaba en un 1,5% del PIB del país, para luego alcanzar un máximo en 2009 con un 2% y caer nuevamente al 1,5%. [196]

Albania se define dentro de un área territorial de 28.748 km² ( 11.100 millas cuadradas) en la península de los Balcanes . Se divide informalmente en tres regiones, las regiones del Norte , Central y Sur . Desde su Declaración de Independencia en 1912, Albania ha reformado su organización interna 21 veces. En la actualidad, las unidades administrativas principales son los doce condados constituyentes ( qarqe / qarqet ), que tienen el mismo estatus ante la ley. [197] Los condados se habían utilizado previamente en la década de 1950 y se recrearon el 31 de julio de 2000 para unificar los 36 distritos ( rrathë / rrathët ) de esa época. [198] [199] El condado más grande de Albania por población es el condado de Tirana con más de 800.000 personas. El condado más pequeño, por población, es el condado de Gjirokastër con más de 70.000 personas. El condado más grande, por área, es el condado de Korçë, que abarca 3.711 kilómetros cuadrados (1.433 millas cuadradas) del sureste de Albania. El condado más pequeño, por área, es el condado de Durrës , con una superficie de 766 kilómetros cuadrados (296 millas cuadradas) en el oeste de Albania.

Los condados se componen de 61 divisiones de segundo nivel conocidas como municipios ( bashki / bashkia ). [200] Los municipios son el primer nivel de gobierno local, responsables de las necesidades locales y la aplicación de la ley . [201] [202] [203] Unificaron y simplificaron el sistema anterior de municipios o comunas urbanas y rurales ( komuna / komunat ) en 2015. [204] [205] Para cuestiones menores de gobierno local , los municipios se organizan en 373 unidades administrativas ( njësia / njësitë administrative ). También hay 2980 aldeas ( fshatra / fshatrat ), barrios o distritos ( lagje / lagjet ) y localidades ( lokalitete / lokalitetet ) utilizadas anteriormente como unidades administrativas.

La transición de Albania de una economía socialista planificada a una economía mixta capitalista ha sido en gran medida exitosa. [208] El país tiene una economía mixta en desarrollo clasificada por el Banco Mundial como una economía de ingresos medios altos . En 2016, tuvo la cuarta tasa de desempleo más baja en los Balcanes con un valor estimado de 14,7%. Sus principales socios comerciales son Italia, Grecia, China, España, Kosovo y Estados Unidos. El lek (ALL) es la moneda del país y está fijado en aproximadamente 132,51 lek por euro.

Las ciudades de Tirana y Durrës constituyen el corazón económico y financiero de Albania debido a su gran población, infraestructuras modernas y ubicación geográfica estratégica. Las instalaciones de infraestructura más importantes del país pasan por ambas ciudades, conectando el norte con el sur y el oeste con el este. Entre las empresas más grandes se encuentran las petroleras Taçi Oil , Albpetrol , ARMO y Kastrati, la minera AlbChrome , la cementera Antea , el grupo inversor BALFIN y las tecnológicas Albtelecom , Vodafone , Telekom Albania y otras.

En 2012, el PIB per cápita de Albania se situó en el 30% de la media de la Unión Europea , mientras que el PIB (PPA) per cápita fue del 35%. [209] En el primer trimestre de 2010, después de la Gran Recesión , Albania fue uno de los tres países de Europa que registraron un crecimiento económico. [210] [211] El Fondo Monetario Internacional predijo un crecimiento del 2,6% para Albania en 2010 y del 3,2% en 2011. [212] Según Forbes , a diciembre de 2016 [update], el Producto Interno Bruto (PIB) estaba creciendo a un 2,8%. El país tenía una balanza comercial del -9,7% y una tasa de desempleo del 14,7%. [213] La inversión extranjera directa ha aumentado significativamente en los últimos años a medida que el gobierno se ha embarcado en un ambicioso programa para mejorar el clima empresarial a través de reformas fiscales y legislativas.

La agricultura del país se basa en unidades familiares dispersas de tamaño pequeño a mediano. Sigue siendo un sector importante de la economía de Albania . Emplea al 41% [214] de la población y aproximadamente el 24,31% de la tierra se utiliza para fines agrícolas. Uno de los sitios agrícolas más antiguos de Europa se ha encontrado en el sureste del país. [215] Como parte del proceso de preadhesión de Albania a la Unión Europea , se está ayudando a los agricultores a través de fondos del IPA para mejorar los estándares agrícolas albaneses. [216]

Albania produce cantidades significativas de frutas (manzanas, aceitunas , uvas, naranjas, limones, albaricoques , melocotones , cerezas , higos , guindas , ciruelas y fresas ), verduras (patatas, tomates, maíz, cebollas y trigo), remolacha azucarera , tabaco, carne, miel , productos lácteos , medicina tradicional y plantas aromáticas . Además, el país es un productor mundial importante de salvia , romero y genciana amarilla . [217] La proximidad del país al mar Jónico y al mar Adriático le da a la industria pesquera subdesarrollada un gran potencial. Los economistas del Banco Mundial y de la Comunidad Europea informan que la industria pesquera de Albania tiene un buen potencial para generar ingresos de exportación porque los precios en los mercados cercanos griego e italiano son muchas veces más altos que los del mercado albanés. Los peces disponibles en las costas del país son carpas , truchas , besugos , mejillones y crustáceos .

Albania tiene una de las historias más largas de viticultura de Europa . [218] La región actual fue uno de los pocos lugares donde se cultivaba vid de forma natural durante la Edad de Hielo. Las semillas más antiguas encontradas en la región tienen entre 4.000 y 6.000 años. [219] En 2009, la nación produjo unas 17.500 toneladas de vino. [220]

.jpg/440px-Cement_factory_in_Fushë-Krujë,_Albania_(10759257413).jpg)

El sector secundario de Albania ha experimentado muchos cambios y diversificación desde que colapsó el régimen comunista. Es muy diversificado, desde electrónica , manufactura , [221] textiles , hasta alimentos , cemento , minería , [222] y energía . La planta de Antea Cement en Fushë-Krujë se considera una de las mayores inversiones industriales en nuevos terrenos del país. [223] El petróleo y el gas albaneses son uno de los sectores más prometedores, aunque estrictamente regulados, de su economía. Albania tiene los segundos depósitos de petróleo más grandes de la península de los Balcanes después de Rumania , y las mayores reservas de petróleo [224] de Europa. La empresa Albpetrol es propiedad del estado albanés y supervisa los acuerdos petroleros estatales en el país. La industria textil ha experimentado una amplia expansión al acercarse a empresas de la Unión Europea (UE) en Albania. Según el Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT) , en 2016 [update], la producción textil tuvo un crecimiento anual del 5,3% y una facturación anual de alrededor de 1.500 millones de euros. [225]

Albania es un importante productor de minerales y se encuentra entre los principales productores y exportadores de cromo del mundo . [226] La nación también es un productor notable de cobre, níquel y carbón. [227] La mina Batra , la mina Bulqizë y la mina Thekna se encuentran entre las minas albanesas más reconocidas que aún se encuentran en funcionamiento.

El sector terciario representa el sector de más rápido crecimiento de la economía del país. El 36% de la población trabaja en el sector de servicios, que contribuye al 65% del PIB del país. [228] Desde finales del siglo XX, la industria bancaria es un componente importante del sector terciario y se mantiene en buenas condiciones en general debido a la privatización y la encomiable política monetaria . [229] [228]

Anteriormente uno de los países más aislados y controlados del mundo, la industria de las telecomunicaciones representa hoy en día otro importante contribuyente al sector. Se desarrolló en gran medida mediante la privatización y la posterior inversión de inversores nacionales y extranjeros. [228] Eagle , Vodafone y Telekom Albania son los principales proveedores de servicios de telecomunicaciones del país.

El turismo es reconocido como una industria de importancia nacional y ha estado aumentando de manera constante desde principios del siglo XXI. [230] [231] Representó directamente el 8,4% del PIB en 2016, aunque si se incluyen las contribuciones indirectas, la proporción aumenta al 26%. [232] En el mismo año, el país recibió aproximadamente 4,74 millones de visitantes, principalmente de toda Europa y de los Estados Unidos también. [233]

El aumento de visitantes extranjeros ha sido espectacular. Albania tuvo solo 500.000 visitantes en 2005, y aproximadamente 4,2 millones en 2012, un aumento del 740 por ciento. En 2015, el turismo de verano aumentó un 25 por ciento con respecto a 2014, según la agencia de turismo del país. [234] En 2011, Lonely Planet nombró a Albania como uno de los principales destinos turísticos, [235] [ verificación fallida ] mientras que The New York Times colocó a Albania como el cuarto destino turístico mundial en 2014. [236]

La mayor parte de la industria turística se concentra a lo largo del mar Adriático y el mar Jónico en el oeste del país. Pero la Riviera albanesa en el suroeste tiene las playas más pintorescas y prístinas; su costa tiene una longitud considerable de 446 kilómetros (277 millas). [237] La costa tiene un carácter distintivo, rica en variedades de playas vírgenes, cabos, calas, bahías cubiertas, lagunas, pequeñas playas de grava, cuevas marinas y muchos accidentes geográficos. Algunas partes de esta costa son muy limpias ecológicamente, incluidas áreas inexploradas, que son muy raras en el Mediterráneo . [238] Otras atracciones incluyen las áreas montañosas como los Alpes albaneses , las montañas Ceraunian y las montañas Korab , pero también las ciudades históricas de Berat , Durrës , Gjirokastër , Sarandë , Shkodër y Korçë .

El transporte en Albania está gestionado dentro de las funciones del Ministerio de Infraestructura y Energía y de entidades como la Autoridad de Carreteras de Albania (ARRSH), responsable de la construcción y mantenimiento de las autopistas y autopistas de Albania, así como la Autoridad de Aviación de Albania (AAC), con la responsabilidad de coordinar la aviación civil y los aeropuertos del país.

El aeropuerto internacional de Tirana es la principal puerta de entrada aérea al país y también es el centro principal de la aerolínea de bandera nacional de Albania , Air Albania . El aeropuerto transportó a más de 3,3 millones de pasajeros en 2019 con conexiones a muchos destinos en otros países de Europa , África y Asia . [239] El país planea aumentar progresivamente el número de aeropuertos, especialmente en el sur, con posibles ubicaciones en Sarandë , Gjirokastër y Vlorë . [240]

Las carreteras y autopistas de Albania se mantienen adecuadamente y a menudo todavía están en construcción y renovación. La Autopista 1 (A1) es un corredor de transporte integral y la autopista más larga del país. Está previsto que una Durrës en el mar Adriático a través de Pristina en Kosovo con el Corredor Paneuropeo X en Serbia. [241] [242] La Autopista 2 (A2) es parte del Corredor Adriático-Jónico , así como del Corredor Paneuropeo VIII y conecta Fier con Vlorë . [241] La Autopista 3 (A3) está en construcción y, después de su finalización, conectará Tirana y Elbasan con el Corredor Paneuropeo VIII. Cuando se completen los tres corredores, Albania tendrá aproximadamente 759 kilómetros (472 millas) de autopistas, que la conectarán con todos los países vecinos.

Durrës es el puerto marítimo más grande y con mayor actividad del país, seguido de Vlorë , Shëngjin y Sarandë . En 2014 [update], es uno de los puertos de pasajeros más grandes del mar Adriático , con un volumen anual de pasajeros de aproximadamente 1,5 millones. Los principales puertos sirven a un sistema de transbordadores que conectan Albania con islas y ciudades costeras de Croacia, Grecia e Italia.

The rail network is administered by the national railway company Hekurudha Shqiptare, which was extensively promoted by Hoxha. There has been considerable increase in private car ownership and bus usage while rail use decreased since the end of communism. A new railway line from Tirana and its airport to Durrës is planned. The location of this railway, connecting Albania's most populated urban areas, makes it an important economic development project.[243][244]

In Albania, education is secular, free, compulsory, and based on three levels.[245][246] The academic year is apportioned into two semesters, beginning in September or October and ending in June or July. Albanian is the primary language of instruction in the country's academic institutions.[246] The study of a first foreign language is mandatory and taught most often at elementary and bilingual schools.[247] Languages taught in schools are English, Italian, French and German.[247] Albania has a school life expectancy of 16 years and a literacy rate of 98.7%, with 99.2% for men and 98.3% for women.[248][249]

Compulsory primary education is divided into two levels, elementary and secondary school, from grade one to five and six to nine, respectively.[245] Pupils are required to attend school from the age six until they turn 16. Upon successful completion of primary education, all pupils are entitled to attend high schools, specializing in any field, including arts, sports, languages, sciences, and technology.[245]

Tertiary education is optional and has undergone a thorough reformation and restructuring in compliance with the principles of the Bologna Process. There are a significant number of private and public institutions of higher education in Albania's major cities.[250][246] Tertiary education is organized into three successive levels, the bachelor, master, and doctorate.

The constitution of Albania guarantees its citizens equal, free, and universal health care.[252] The health care system is organized into primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare, and is in a process of modernization and development.[253][254] The life expectancy at birth in Albania is 77.8 years, ranking 37th in the world and surpassing several developed countries.[255] The average healthy life expectancy is 68.8 years, ranking 37th in the world.[256] The country's infant mortality rate was estimated at 12 per 1,000 live births in 2015. In 2000, the country had the world's 55th-best healthcare performance, as defined by the World Health Organization.[257]

Cardiovascular disease is the principal cause of death in Albania, accounting for 52% of deaths.[253] Accidents, injuries, malignant and respiratory diseases are other primary causes of death.[253] Neuropsychiatric disease has also increased due to recent demographic, social, and economic changes in the country.[253]

In 2009, Albania had a fruit and vegetable supply of 886 grams per capita per day, the fifth-highest supply in Europe.[258] Compared to other developed and developing countries, Albania has a relatively low rate of obesity, probably thanks to the Mediterranean diet.[259][260] According to World Health Organization data from 2016, 21.7% of adults in the country are clinically overweight, with a Body mass index (BMI) score of 25 or more.[261]

Due to its location and natural resources, Albania has a wide variety of energy resources, ranging from gas, oil, and coal to wind, solar, water, and other renewable sources.[262][263] According to the World Economic Forum's 2023 Energy Transition Index (ETI), the country ranked 21st globally, highlighting the progress in its energy transition agenda.[264] Currently, Albania's electricity generation sector depends on hydroelectricity, ranking fifth in the world in percentage terms.[265][266][267] The Drin, in the north, hosts four hydroelectric power stations, including Fierza, Koman, Skavica and Vau i Dejës. Two other power stations, such as the Banjë and Moglicë, are along the Devoll in the south.[268]

Albania has considerable oil deposits. It has the 10th-largest oil reserves in Europe and the 58th in the world.[269] The country's main petroleum deposits are located around the Albanian Adriatic Sea Coast and Myzeqe Plain within the Western Lowlands, where the country's largest reserve is located. Patos-Marinza, also located within the area, is the largest onshore oil field in Europe.[270] The Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), part of the planned Southern Gas Corridor, runs for 215 kilometres (134 miles) across Albania's territory before entering the Albanian Adriatic Sea Coast approximately 17 kilometres (11 miles) northwest of Fier.[271]

Albania's water resources are particularly abundant in all the regions of the country and comprise lakes, rivers, springs, and groundwater aquifers.[272] The country's available average quantity of fresh water is estimated at 129.7 cubic metres (4,580 cubic feet) per inhabitant per year, one of the highest rates in Europe.[273] According to data presented by the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP) in 2015, about 93% of the country's total population had access to improved sanitation.[274]

.jpg/440px-Villa_of_the_former_Radio_Tirana_(03).jpg)

The freedom of press and speech, and the right to free expression is guaranteed in the constitution of Albania.[275] Albania was ranked 84th on the Press Freedom Index of 2020 compiled by the Reporters Without Borders, with its score steadily declining since 2003.[276] Nevertheless, in the 2020 report of Freedom in the World, the Freedom House classified the freedoms of press and speech in Albania as partly free from political interference and manipulation.[277]

Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSH) is the national broadcaster corporation of Albania operating numerous television and radio stations in the country.[278] The three major private broadcaster corporations are Top Channel, Televizioni Klan and Vizion Plus whose content are distributed throughout Albania and beyond its territory in Kosovo and other Albanian-speaking territories.

Albanian cinema has its roots in the 20th century and developed after the country's declaration of independence.[279] The first movie theater exclusively devoted to showing motion pictures was built in 1912 in Shkodër.[279] During the Peoples Republic of Albania, Albanian cinema developed rapidly with the inauguration of the Kinostudio Shqipëria e Re in Tirana.[279] In 1953, the Albanian-Soviet epic film, the Great Warrior Skanderbeg, was released chronicling the life and fight of the medieval Albanian hero Skanderbeg. It went on to win the international prize at the 1954 Cannes Film Festival. In 2003, the Tirana International Film Festival was established, the largest film festival in the country. The Durrës Amphitheatre is host to the Durrës International Film Festival, the second largest film festival.

After the fall of communism in 1991, human resources in sciences and technology in Albania have drastically decreased. As of various reports, during 1991 to 2005 approximately 50% of the professors and scientists of the universities and science institutions in the country have left Albania.[280] In 2009, the government approved the National Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation in Albania covering the period 2009 to 2015.[281] It aims to triple public spending on research and development to 0.6% of GDP and augment the share of GDE from foreign sources, including the framework programmes for research of the European Union, to the point where it covers 40% of research spending, among others. Albania was ranked 83rd in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[282][283]

Telecommunication represents one of the fastest growing and dynamic sectors in Albania.[284][285] Vodafone Albania, Telekom Albania and Albtelecom are the three large providers of mobile and internet in Albania.[284] As of the Electronic and Postal Communications Authority (AKEP) in 2018, the country had approximately 2.7 million active mobile users with almost 1.8 million active broadband subscribers.[286] Vodafone Albania alone served more than 931,000 mobile users, Telekom Albania had about 605,000 users and Albtelecom had more than 272,000 users.[286] In January 2023, Albania launched its first two satellites, Albania 1 and Albania 2, into orbit, in what was regarded as a milestone effort in monitoring the country's territory and identifying illegal activities.[287][288] Albanian-American engineer Mira Murati, the Chief Technology Officer of research organization OpenAI, played a substantial role in the development and launch of artificial intelligence services such as ChatGPT, Codex and DALL-E.[289][290][291] In December 2023, Prime Minister Edi Rama announced plans for collaboration between the Albanian government and ChatGPT, facilitated by discussions with Murati.[292][293] Rama emphasised the intention to streamline the alignment of Albanian laws with the regulations of the European Union, aiming to reduce costs associated with translation and legal services.[292]

The demographic statistics of Albania, as revealed by the 2023 census conducted by the Instituti i Statistikave (INSTAT), indicated a population of 2,402,113, with a notable decline from the 2,821,977 recorded in the 2011 census.[2][294] The decrease in inhabitants began after the disintegration of the communist regime in Albania and is associated with significant shifts within the political, economic, and social structure of Albania.[295][296] A principal factor in this transition incorporates a decline in fertility rates coupled with an increase in emigration, both contributing to persistent demographic changes and challenges.[297] It is forecast that the population will continue shrinking for the next decade at least, depending on the actual rates and the level of migration.[298] Currently, the population density of Albania is measured at 83.6 inhabitants per square kilometer with a varied distribution of inhabitants across different regions.[2][299] The counties of Tirana and Durrës showcase substantial concentrations of people, accounting for about 41% of the overall demographic of Albania, with 32% residing in Tirana and 9% in Durrës.[300] Conversely, more peripheral and rural counties such as Gjirokastër and Kukës present significantly lower population densities, with each aiding 3% to the overall population.[300]

Historically, the Albanian people have established several communities in many regions throughout Southern Europe. The Albanian diaspora has been formed since the late Middle Ages, when they emigrated to escape either various socio-political difficulties or the Ottoman conquest of Albania.[301] Following the fall of communism, large numbers of Albanians have migrated to countries such as Australia, Canada, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. Albanian minorities are present in the neighbouring territories such as the west of North Macedonia, the southeast of Montenegro, Kosovo in its entirety and parts of southern Serbia. Altogether, the number of ethnic Albanians living abroad is estimated to be higher than the total population inside Albania. As much as a third of those born in the country's borders now live outside of it, making Albania one of the countries with the highest rate of outmigration relative to its population in the world.[302][303] In 2022 the birth rate was 20% lower than in 2021, largely due to emigration of people of childbearing age.[304]

Subsequent to the collapse of communism in 1991, Albania has undergone a remarkable transformation in its urban landscape, emerging as one of the fastest urbanising countries in Europe.[305][306][307] At the forefront of this transformation is the Tirana-Durrës agglomeration, a densely populated urban corridor situated along the western coast of Albania.[308] This corridor has become the primary locus of population growth and settlement development, attracting a significant influx of internal migrants from the country's peripheral areas.[308] Despite an overall decline of the country's total population, the proportion of the urban demographic has consistently progressed from 47% in 2001 to 65% in 2023.[296][309][310] This sustained increase, coupled with the concentration in the Tirana-Durrës region, has led to a spread of regional imbalances, with the peripheral areas, particularly Dibër and Kukës, experiencing severe depopulation.[311][312][300]

The official language of the country is Albanian which is spoken by the vast majority of the country's population.[324] Its standard spoken and written form is revised and merged from the two main dialects, Gheg and Tosk, though it is notably based more on the Tosk dialect. The Shkumbin river is the rough dividing line between the two dialects. Among minority languages, Greek is the second most-spoken language in the country, with 0.5 to 3% of the population speaking it as first language, mainly in the country's south where its speakers are concentrated.[325][326][327][328] Other languages spoken by ethnic minorities in Albania include Aromanian, Serbian, Macedonian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Gorani, and Roma.[329] Macedonian is official in the Pustec Municipality in East Albania. According to the 2011 population census, 2,765,610 or 98.8% of the population declared Albanian as their mother tongue.[330] Because of large migration flows from Albania, over half of Albanians during their life learn a second language. The main foreign language known is English with 40.0%, followed by Italian with 27.8% and Greek with 22.9%. The English speakers were mostly young people, the knowledge of Italian is stable in every age group, while there is a decrease of the speakers of Greek in the youngest group.[331]

Among young people aged 25 or less, English, German and Turkish have seen rising interest after 2000. Italian and French have had a stable interest, while Greek has lost much of its previous interest. The trends are linked with cultural and economic factors.[332]