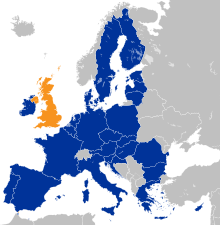

Brexit ( / ˈb r ɛ k s ɪ t , ˈb r ɛ ɡ z ɪ t / , [1] un acrónimo de "British exit") fue la retirada del Reino Unido (RU) de la Unión Europea ( UE ). Tras un referéndum celebrado en el Reino Unido el 23 de junio de 2016, el Brexit se llevó a cabo oficialmente a las 23:00 GMT del 31 de enero de 2020 (00:00 1 de febrero de 2020 CET ). [a] El Reino Unido, que se unió a las precursoras de la UE, las Comunidades Europeas (CE) el 1 de enero de 1973, es el único estado miembro que se ha retirado de la UE. Tras el Brexit, el derecho de la UE y el Tribunal de Justicia de la Unión Europea ya no tienen primacía sobre las leyes británicas . La Ley de (Retirada) de la Unión Europea de 2018 conserva el derecho de la UE pertinente como derecho interno , que el Reino Unido puede modificar o derogar.

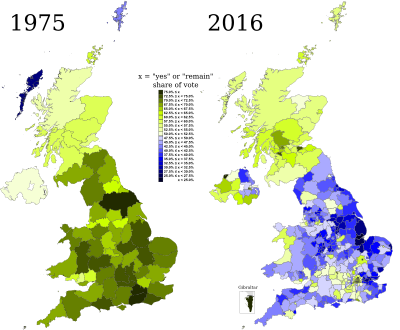

La UE y sus instituciones se fueron desarrollando gradualmente tras su creación. Durante el período de pertenencia británica, en el Reino Unido habían existido grupos euroescépticos que se oponían a aspectos de la UE y sus predecesores. El gobierno pro-CE del primer ministro laborista Harold Wilson celebró un referéndum sobre la permanencia en la CE en 1975 , en el que el 67,2 por ciento de los votantes optó por permanecer en el bloque. A pesar de la creciente oposición política a una mayor integración europea destinada a una " unión cada vez más estrecha " entre 1975 y 2016, en particular por parte de facciones del Partido Conservador en los años 1980 a 2000, no se celebraron más referendos sobre el tema.

En la década de 2010, la creciente popularidad del Partido de la Independencia del Reino Unido (UKIP), así como la presión de los euroescépticos en su propio partido, persuadieron al primer ministro conservador David Cameron a prometer un referéndum sobre la pertenencia británica a la UE si su gobierno era reelegido. Después de las elecciones generales de 2015 , que produjeron una pequeña pero inesperada mayoría general para el gobernante Partido Conservador, el prometido referéndum sobre la permanencia de la UE se celebró el 23 de junio de 2016. Entre los partidarios notables de la campaña Remain se encontraban Cameron, las futuras primeras ministras Theresa May y Liz Truss , y los ex primeros ministros John Major , Tony Blair y Gordon Brown ; entre los partidarios notables de la campaña Leave se encontraban los futuros primeros ministros Boris Johnson y Rishi Sunak . El electorado votó a favor de abandonar la UE con un 51,9% de los votos, con todas las regiones de Inglaterra y Gales, excepto Londres, votando a favor del Brexit, y Escocia e Irlanda del Norte votando en contra. El resultado llevó a la renuncia repentina de Cameron, su reemplazo por Theresa May y cuatro años de negociaciones con la UE sobre los términos de la salida y sobre las relaciones futuras, completadas bajo el gobierno de Boris Johnson, y durante este período el control del gobierno permaneció en manos del Partido Conservador.

El proceso de negociación fue políticamente desafiante y profundamente divisivo dentro del Reino Unido, lo que llevó a dos elecciones anticipadas en 2017 y 2019. Un acuerdo fue rechazado abrumadoramente por el parlamento británico , lo que causó una gran incertidumbre y llevó a posponer la fecha de retirada para evitar un Brexit sin acuerdo . El Reino Unido abandonó la UE el 31 de enero de 2020 después de que el Parlamento aprobara un acuerdo de retirada, pero continuó participando en muchas instituciones de la UE (incluido el mercado único y la unión aduanera) durante un período de transición de once meses para garantizar un comercio sin fricciones hasta que se acordaran e implementaran todos los detalles de la relación posterior al Brexit. Las negociaciones del acuerdo comercial continuaron a los pocos días del final programado del período de transición, y el Acuerdo de Comercio y Cooperación UE-Reino Unido se firmó el 30 de diciembre de 2020. Los efectos del Brexit están determinados en parte por el acuerdo de cooperación, que se aplicó provisionalmente desde el 1 de enero de 2021, hasta que entró en vigor formalmente el 1 de mayo de 2021. [2]

Tras un referéndum celebrado en todo el Reino Unido el 23 de junio de 2016 , en el que el 51,89 por ciento votó a favor de abandonar la UE y el 48,11 por ciento votó a favor de seguir siendo un estado miembro, David Cameron dimitió como primer ministro. El 29 de marzo de 2017, el nuevo gobierno británico dirigido por Theresa May notificó formalmente a la UE la intención del país de retirarse, iniciando el proceso de negociaciones del Brexit . La retirada, prevista originalmente para el 29 de marzo de 2019, se retrasó por el punto muerto en el parlamento británico tras las elecciones generales de junio de 2017 , que dieron lugar a un parlamento sin mayoría en el que los conservadores perdieron su mayoría pero siguieron siendo el partido más grande. Este punto muerto dio lugar a tres prórrogas del proceso del Artículo 50 del Reino Unido .

El estancamiento se resolvió después de la celebración de unas elecciones generales posteriores en diciembre de 2019. En esas elecciones, los conservadores que hicieron campaña a favor de un acuerdo de retirada "revisado" liderado por Boris Johnson obtuvieron una mayoría general de 80 escaños. Después de las elecciones de diciembre de 2019, el parlamento británico finalmente ratificó el acuerdo de retirada con la Ley de la Unión Europea (Acuerdo de Retirada) de 2020. El Reino Unido abandonó la UE a finales del 31 de enero de 2020 CET (23:00 GMT ). [3] Esto dio inicio a un período de transición que finalizó el 31 de diciembre de 2020 CET (23:00 GMT), durante el cual el Reino Unido y la UE negociaron su futura relación. [4] Durante la transición, el Reino Unido siguió sujeto a la legislación de la UE y siguió siendo parte de la Unión Aduanera de la Unión Europea y del mercado único europeo . Sin embargo, ya no formaba parte de los órganos o instituciones políticas de la UE. [5] [6]

La retirada había sido defendida por euroescépticos duros y se había opuesto a ella tanto proeuropeístas como euroescépticos moderados , y ambos lados del argumento abarcaban todo el espectro político. En 1973, el Reino Unido se unió a las Comunidades Europeas (CE), principalmente la Comunidad Económica Europea (CEE), y su permanencia como miembro fue aprobada en el referéndum de membresía de 1975. En las décadas de 1970 y 1980, la retirada de la CE fue defendida principalmente por la izquierda política, por ejemplo, en el manifiesto electoral de 1983 del Partido Laborista . El Tratado de Maastricht de 1992 , que fundó la UE, fue ratificado por el parlamento británico en 1993, pero no se sometió a referéndum. El ala euroescéptica del Partido Conservador lideró una rebelión por la ratificación del tratado y, junto con el Partido de la Independencia del Reino Unido (UKIP) y la campaña multipartidaria People's Pledge , encabezó una campaña colectiva, en particular después de que el Tratado de Lisboa también fuera ratificado por la Ley de la Unión Europea (Enmienda) de 2008 sin ser sometido a referéndum tras una promesa previa de celebrar un referéndum sobre la ratificación de la abandonada Constitución Europea , que nunca se celebró. Después de prometer celebrar un segundo referéndum de adhesión si su gobierno era elegido, el primer ministro conservador David Cameron celebró este referéndum en 2016. Cameron, que había hecho campaña a favor de la permanencia, dimitió tras el resultado y fue sucedido por Theresa May .

El 29 de marzo de 2017, el gobierno británico inició formalmente el proceso de retirada invocando el artículo 50 del Tratado de la Unión Europea con el permiso del Parlamento . May convocó elecciones generales anticipadas en junio de 2017, que dieron como resultado un gobierno minoritario conservador apoyado por el Partido Unionista Democrático (DUP). Las negociaciones de retirada del Reino Unido y la UE comenzaron a finales de ese mes. El Reino Unido negoció abandonar la unión aduanera y el mercado único de la UE. Esto resultó en el acuerdo de retirada de noviembre de 2018 , pero el parlamento británico votó en contra de ratificarlo tres veces. El Partido Laborista quería que cualquier acuerdo mantuviera una unión aduanera, mientras que muchos conservadores se opusieron al acuerdo financiero del acuerdo , así como al " backstop irlandés " diseñado para evitar los controles fronterizos entre Irlanda del Norte y la República de Irlanda . Los Demócratas Liberales , el Partido Nacional Escocés (SNP) y otros buscaron revertir el Brexit a través de un segundo referéndum propuesto .

El 14 de marzo de 2019, el parlamento británico votó a favor de que May pidiera a la UE que retrasara el Brexit hasta junio y luego hasta octubre. [7] Al no lograr que se aprobara su acuerdo, May renunció como primera ministra en julio y fue reemplazada por Boris Johnson . Intentó reemplazar partes del acuerdo y prometió abandonar la UE antes de la nueva fecha límite. El 17 de octubre de 2019, el gobierno británico y la UE acordaron un acuerdo de retirada revisado, con nuevos acuerdos para Irlanda del Norte. [8] [9] El parlamento aprobó el acuerdo para un mayor escrutinio, pero rechazó aprobarlo como ley antes de la fecha límite del 31 de octubre y obligó al gobierno (a través de la " Ley Benn ") a solicitar un tercer retraso del Brexit. Luego se celebraron elecciones generales anticipadas el 12 de diciembre. Los conservadores obtuvieron una gran mayoría en esa elección, y Johnson declaró que el Reino Unido abandonaría la UE a principios de 2020. [10] El acuerdo de retirada fue ratificado por el Reino Unido el 23 de enero y por la UE el 30 de enero; Entró en vigor el 31 de enero de 2020. [11] [12] [13]

Tras el referéndum del 23 de junio de 2016, muchas nuevas piezas de jerga relacionadas con el Brexit entraron en uso popular. [14] [15] La palabra Brexit es un acrónimo de la frase "British exit" (salida británica). [16] Según el Oxford English Dictionary , el término fue acuñado en una publicación de blog en el sitio web Euractiv por Peter Wilding, director de política europea en BSkyB , el 15 de mayo de 2012. [17] Wilding acuñó Brexit para referirse al final de la membresía del Reino Unido en la UE; para 2016, el uso de la palabra había aumentado en un 3400% en un año. [18] El 2 de noviembre de 2016, el Collins English Dictionary seleccionó Brexit como la palabra del año 2016. [19]

Los seis países europeos más importantes firmaron el Tratado de París en 1951, por el que se establecía la Comunidad Europea del Carbón y del Acero (CECA). La Conferencia de Messina de 1955 consideró que la CECA había sido un éxito y decidió ampliar el concepto, lo que dio lugar a los Tratados de Roma de 1957, por los que se establecían la Comunidad Económica Europea (CEE) y la Comunidad Europea de la Energía Atómica (Euratom). En 1967 , estas se conocieron como las Comunidades Europeas (CE). El Reino Unido intentó unirse en 1963 y 1967, pero estas solicitudes fueron vetadas por el presidente de Francia , Charles de Gaulle , que temía que el Reino Unido fuera un caballo de Troya para la influencia estadounidense. [20] [21]

Poco después de que De Gaulle dimitiera en 1969, el Reino Unido solicitó con éxito su adhesión a las Comunidades Europeas (CE). La adhesión a la entonces CEE se debatió a fondo en el largo debate celebrado en la Cámara de los Comunes en octubre de 1971, que condujo a la votación decisiva a favor de la adhesión por 356 votos a favor y 244 en contra. Como observó el historiador Piers Ludlow, el debate parlamentario de 1971 fue de gran calidad y consideró todas las cuestiones. Los británicos no fueron "engañados ni persuadidos para aceptar la adhesión a una entidad comercial limitada sin ser conscientes de que la CEE era un proyecto político susceptible de desarrollarse en el futuro". [22] El primer ministro conservador Edward Heath firmó el Tratado de Adhesión en 1972. [23] El Parlamento aprobó la Ley de las Comunidades Europeas más tarde ese año [24] y el Reino Unido se unió a Dinamarca y la República de Irlanda para convertirse en miembro el 1 de enero de 1973, sin referéndum. [25]

Durante los años 1970 y 1980, el Partido Laborista fue el más euroescéptico de los dos partidos principales, y los conservadores el más eurófilo. El Partido Laborista ganó las elecciones generales de febrero de 1974 sin una mayoría y luego participó en las elecciones generales posteriores de octubre de 1974 con el compromiso de renegociar los términos de membresía de Gran Bretaña en la CE, creyéndolos desfavorables, y luego celebrar un referéndum sobre si permanecer en la CE en los nuevos términos. [26] El Partido Laborista volvió a ganar las elecciones (esta vez con una pequeña mayoría), y en 1975 el Reino Unido celebró su primer referéndum nacional , preguntando si el Reino Unido debía permanecer en la CE. A pesar de la división significativa dentro del gobernante Partido Laborista, [27] todos los partidos políticos principales y la prensa convencional apoyaron la membresía continua en la CE. El 5 de junio de 1975, el 67,2% del electorado y todos los condados y regiones británicos menos dos [28] votaron a favor de permanecer; [29] El apoyo a la salida del Reino Unido de la CE en 1975 parece no tener relación con el apoyo a la salida en el referéndum de 2016. [30]

En 1979, el Reino Unido consiguió su primer opt-out , aunque la expresión no era contemporánea: era el único país de la CEE que no participaba en el Sistema Monetario Europeo .

El Partido Laborista hizo campaña en las elecciones generales de 1983 con el compromiso de retirarse de la CE sin referéndum. [31] Tras su dura derrota en esas elecciones, el Partido Laborista cambió su política. [31] En 1985, el segundo gobierno de Margaret Thatcher ratificó el Acta Única Europea —la primera revisión importante del Tratado de Roma— sin referéndum. [32]

En octubre de 1990, bajo presión de los ministros de alto rango y a pesar de las profundas reservas de Thatcher, el Reino Unido se unió al Mecanismo Europeo de Tipos de Cambio (MEC), con la libra esterlina vinculada al marco alemán . Thatcher renunció como Primera Ministra al mes siguiente, en medio de divisiones en el Partido Conservador que surgieron en parte de sus opiniones cada vez más euroescépticas. El Reino Unido se vio obligado a retirarse del MEC el Miércoles Negro de septiembre de 1992, después de que la libra esterlina se viera presionada por la especulación monetaria . [33] Italia se fue el mismo mes, pero pronto se reincorporaría en una banda diferente. El Reino Unido no buscó volver a ingresar y permaneció fuera del MEC.

El 1 de noviembre de 1993, después de que el Reino Unido y los otros once estados miembros hubieran ratificado, la CE se convirtió en la UE bajo el Tratado de Maastricht [34] compromiso entre los estados miembros que buscaban una integración más profunda y aquellos que deseaban mantener un mayor control nacional en la unión económica y política . [35] Dinamarca , Francia y la República de Irlanda celebraron referendos para ratificar el Tratado de Maastricht. De acuerdo con la Constitución del Reino Unido , específicamente la de la soberanía parlamentaria , la ratificación en el Reino Unido no estaba sujeta a la aprobación por referéndum. A pesar de esto, el historiador constitucional británico Vernon Bogdanor escribió que había "una clara justificación constitucional para requerir un referéndum" porque, aunque el electorado confía a los parlamentarios el poder legislativo, no se les da autoridad para transferir ese poder (los tres referendos anteriores del Reino Unido se referían a esto). Además, como la ratificación del tratado estaba en los manifiestos de los tres principales partidos políticos, los votantes opuestos a la ratificación tenían opciones limitadas para expresarlo. Para Bogdanor, si bien la ratificación por parte de la Cámara de los Comunes podría ser legal, no sería legítima, ya que requiere el consentimiento popular. La forma en que se ratificó el tratado, consideró, "probablemente tendría consecuencias fundamentales tanto para la política británica como para la relación de Gran Bretaña con la [CE]". [36] [37]

Thatcher, que anteriormente había apoyado el mercado común y el Acta Única Europea, en el discurso de Brujas de 1988 advirtió contra "un superestado europeo que ejerza un nuevo dominio desde Bruselas". Ella influyó en Daniel Hannan , quien en 1990 fundó la Campaña de Oxford para una Gran Bretaña Independiente; "En retrospectiva, algunos ven esto como el comienzo de la campaña por el Brexit", escribió más tarde el Financial Times . [38] La votación para aprobar el Tratado de Maastricht en 1993 desencadenó una fuerte respuesta euroescéptica, dividiendo al Partido Conservador y llevando a muchos partidarios anteriores a formar partidos euroescépticos alternativos. Esto incluyó a Sir James Goldsmith formando el Partido del Referéndum en 1994 para competir en las elecciones generales de 1997 con una plataforma de proporcionar un referéndum sobre la naturaleza de la relación del Reino Unido con el resto de la UE. [39] [40] El partido presentó candidatos en 547 distritos electorales en esa elección y ganó 810.860 votos (el 2,6% del total de votos emitidos) [41] , pero no logró obtener un escaño parlamentario porque el voto se distribuyó por todo el país. El Partido del Referéndum se disolvió tras la muerte de Goldsmith en 1997. [ cita requerida ] . El Partido de la Independencia del Reino Unido (UKIP), un partido político euroescéptico, se formó en respuesta a Maastricht en 1993. En 1997, Nigel Farage asumió el liderazgo del partido como un movimiento populista de centroderecha en Inglaterra . [42]

Antes de 2013, la cuestión de la pertenencia a la UE nunca obtuvo una puntuación superior al 5% en las encuestas sobre las prioridades de los votantes, con solo el 6% en 2013 [43] y el 11% en 2014. [44] Sin embargo, una proporción cada vez mayor de votantes consideraba que la inmigración y el asilo eran de importancia clave. [45] Al adoptar una plataforma antiinmigratoria de línea dura y combinar la cuestión con la pertenencia a la UE, el UKIP pudo lograr el éxito electoral, alcanzando el tercer lugar en el Reino Unido durante las elecciones europeas de 2004 , el segundo lugar en las elecciones europeas de 2009 y el primer lugar en las elecciones europeas de 2014 , con el 27,5% del total de votos. Esta fue la primera vez desde las elecciones generales de 1910 que un partido distinto del Laborismo o los Conservadores había obtenido la mayor proporción de votos en una elección nacional. [46] Este éxito electoral y la presión interna, incluso de muchos de los rebeldes de Maastricht que quedan dentro del partido conservador gobernante, ejercieron presión sobre el líder y primer ministro David Cameron , ya que las posibles deserciones de votantes al UKIP amenazaron con la derrota en las elecciones generales del Reino Unido de 2015. Esta amenaza se enfatizó cuando el UKIP ganó dos elecciones parciales (en Clacton y Rochester y Strood , desencadenadas por parlamentarios conservadores desertores) en 2014. [47]

Tanto las opiniones a favor como en contra de la UE tuvieron un apoyo mayoritario en diferentes momentos entre 1977 y 2015. [48] En el referéndum sobre la pertenencia a la CE de 1975 , dos tercios de los votantes británicos estaban a favor de seguir siendo miembros de la CE. Durante las décadas de pertenencia del Reino Unido a la UE, el euroescepticismo existió tanto en la izquierda como en la derecha de la política británica. [49] [50] [51]

Según un análisis estadístico publicado en abril de 2016 por el profesor John Curtice de la Universidad Strathclyde , las encuestas mostraron un aumento del euroescepticismo (el deseo de abandonar la UE o permanecer en la UE y tratar de reducir los poderes de la UE) del 38% en 1993 al 65% en 2015. La encuesta de BSA para el período de julio a noviembre de 2015 mostró que el 60% respaldaba la opción de continuar como miembro y el 30% respaldaba la retirada. [52]

En 2012, el primer ministro David Cameron rechazó inicialmente las peticiones de un referéndum sobre la pertenencia del Reino Unido a la UE, [53] pero luego sugirió la posibilidad de un referéndum futuro para respaldar su propuesta de renegociación de la relación de Gran Bretaña con el resto de la UE. [54] Según la BBC , "el primer ministro reconoció la necesidad de asegurar que la posición [renegociada] del Reino Unido dentro de la [UE] tuviera 'el apoyo incondicional del pueblo británico', pero necesitaban mostrar 'paciencia táctica y estratégica'". [55] El 23 de enero de 2013, bajo la presión de muchos de sus parlamentarios y del ascenso del UKIP, Cameron prometió en su discurso en Bloomberg que un gobierno conservador celebraría un referéndum sobre la pertenencia o no a la UE antes de finales de 2017, sobre un paquete renegociado, si era elegido en las elecciones generales del 7 de mayo de 2015. [56] Esto se incluyó en el manifiesto del Partido Conservador para la elección. [ 57] [58]

El Partido Conservador ganó las elecciones por mayoría. Poco después, se presentó al Parlamento la Ley del Referéndum de la Unión Europea de 2015 para permitir el referéndum. Cameron estaba a favor de permanecer en una UE reformada y trató de renegociar cuatro puntos clave: la protección del mercado único para los países no pertenecientes a la eurozona, la reducción de la "burocracia", la exención de Gran Bretaña de una "unión cada vez más estrecha" y la restricción de la inmigración procedente del resto de la UE. [59]

En diciembre de 2015, las encuestas de opinión mostraron una clara mayoría a favor de permanecer en la UE; también mostraron que el apoyo caería si Cameron no negociaba salvaguardas adecuadas [ definición necesaria ] para los estados miembros no pertenecientes a la eurozona y restricciones a los beneficios para los ciudadanos de la UE no pertenecientes al Reino Unido. [60]

El resultado de las renegociaciones se reveló en febrero de 2016. Se acordaron algunos límites a los beneficios laborales para los nuevos inmigrantes de la UE, pero antes de que pudieran aplicarse, un estado miembro como el Reino Unido tendría que obtener permiso de la Comisión Europea y luego del Consejo Europeo , que está compuesto por los jefes de gobierno de cada estado miembro. [61]

En un discurso ante la Cámara de los Comunes el 22 de febrero de 2016, Cameron anunció la fecha del referéndum para el 23 de junio de 2016 y comentó sobre el acuerdo de renegociación. [62] Habló de la intención de iniciar el proceso del Artículo 50 inmediatamente después de un voto a favor de abandonar la UE y del "período de dos años para negociar los acuerdos de salida". [63]

Después de que la redacción original de la pregunta del referéndum fuera cuestionada, [64] el gobierno acordó cambiar la pregunta oficial del referéndum a "¿Debería el Reino Unido seguir siendo miembro de la Unión Europea o abandonar la Unión Europea?".

En el referéndum, el 51,89% votó a favor de abandonar la UE (Leave) y el 48,11% votó a favor de seguir siendo miembro de la UE (Remain). [65] [66] Después de este resultado, Cameron dimitió el 13 de julio de 2016, y Theresa May se convirtió en primera ministra tras una votación por el liderazgo . Una petición que pedía un segundo referéndum atrajo más de cuatro millones de firmas, [67] [68] pero fue rechazada por el gobierno el 9 de julio. [69]

Un estudio de 2017 publicado en la revista Economic Policy mostró que el voto por el Brexit tendía a ser mayor en áreas que tenían ingresos más bajos y alto desempleo , una fuerte tradición de empleo manufacturero y en las que la población tenía menos calificaciones . También tendía a ser mayor donde había un gran flujo de inmigrantes de Europa del Este (principalmente trabajadores poco calificados) en áreas con una gran proporción de trabajadores nativos poco calificados. [71] Aquellos en los estratos sociales más bajos (especialmente la clase trabajadora ) tenían más probabilidades de votar por el Brexit, mientras que aquellos en los estratos sociales más altos (especialmente la clase media alta ) tenían más probabilidades de votar por el Brexit. [72] [73] [74] Los estudios encontraron que el voto por el Brexit tendía a ser mayor en áreas afectadas por el declive económico, [75] altas tasas de suicidios y muertes relacionadas con las drogas, [76] y reformas de austeridad introducidas en 2010. [77]

Los estudios sugieren que las personas mayores tenían más probabilidades de votar por el Brexit, y las personas más jóvenes, por el Brexit. [78] Según Thomas Sampson, economista de la London School of Economics , "los votantes mayores y menos educados tenían más probabilidades de votar por el Brexit [...] Una mayoría de votantes blancos querían irse, pero solo el 33% de los votantes asiáticos y el 27% de los votantes negros eligieron el Brexit. [...] Salir de la Unión Europea recibió apoyo de todo el espectro político [...] Votar por salir de la Unión Europea estaba fuertemente asociado con tener creencias políticas socialmente conservadoras, oponerse al cosmopolitismo y pensar que la vida en Gran Bretaña está empeorando". [79]

Las encuestas realizadas por YouGov respaldaron estas conclusiones, mostrando que factores como la edad, la afiliación a un partido político, la educación y los ingresos familiares eran los principales factores que indicaban cómo votaría la gente. Por ejemplo, los votantes del Partido Conservador tenían un 61% de probabilidades de votar por el Brexit, en comparación con los votantes del Partido Laborista, que tenían un 35% de probabilidades de votar por el Brexit. La edad fue uno de los factores más importantes que afectaron a si alguien votaría por el Brexit, ya que el 64% de las personas mayores de 65 años tenían probabilidades de votar por el Brexit, mientras que los jóvenes de 18 a 24 años tenían solo un 29% de probabilidades de votar por el Brexit. La educación fue otro factor que indicó la probabilidad de voto: las personas con un GCSE o un nivel de educación inferior tenían un 70% de probabilidades de votar por el Brexit, mientras que los graduados universitarios tenían solo un 32% de probabilidades de votar por el Brexit. Los ingresos familiares fueron otro factor importante, ya que los hogares que ganaban menos de £ 20,000 tenían un 62% de probabilidades de votar por el Brexit, en comparación con los hogares que ganaban £ 60,000 o más, que tenían solo un 35% de probabilidades de votar por el Brexit. [80]

Hubo grandes variaciones en el apoyo geográfico para cada lado. Escocia e Irlanda del Norte votaron mayoritariamente por la permanencia, aunque esto tuvo un impacto relativamente pequeño en el resultado general ya que Inglaterra tiene una población mucho mayor. También hubo diferencias regionales significativas dentro de Inglaterra, con la mayor parte de Londres votando mayoritariamente por la permanencia, junto con centros urbanos en el norte de Inglaterra como Manchester y Liverpool, que votaron por la permanencia con mayorías del 60% y 58% respectivamente. Se observaron tendencias opuestas en las áreas industriales y postindustriales del norte de Inglaterra , con áreas como North Lincolnshire y South Tyneside apoyando fuertemente la salida. [81]

Las encuestas de opinión revelaron que los votantes del Brexit creían que abandonar la UE "probablemente traería consigo un mejor sistema de inmigración, mejores controles fronterizos, un sistema de bienestar más justo, una mejor calidad de vida y la capacidad de controlar nuestras propias leyes", mientras que los votantes del Remain creían que la pertenencia a la UE "sería mejor para la economía, la inversión internacional y la influencia del Reino Unido en el mundo". Las encuestas revelaron que las principales razones por las que la gente votó por el Brexit fueron "el principio de que las decisiones sobre el Reino Unido deben tomarse en el Reino Unido", y que el Brexit "ofrecía la mejor oportunidad para que el Reino Unido recuperara el control sobre la inmigración y sus propias fronteras". La principal razón por la que la gente votó por el Remain fue que "los riesgos de votar por abandonar la UE parecían demasiado grandes en lo que respecta a cuestiones como la economía, el empleo y los precios". [82]

Tras el referéndum, la Comisión Electoral investigó una serie de irregularidades relacionadas con el gasto de campaña y posteriormente impuso una gran cantidad de multas. En febrero de 2017, el principal grupo de campaña a favor del Brexit, Leave.EU , fue multado con 50 000 libras esterlinas por enviar mensajes de marketing sin permiso. [83] En diciembre de 2017, la Comisión Electoral multó a dos grupos pro-UE, los Demócratas Liberales (18 000 libras esterlinas) y Open Britain (1250 libras esterlinas), por infringir las normas de financiación de campañas durante la campaña del referéndum. [84] En mayo de 2018, la Comisión Electoral multó a Leave.EU con 70 000 libras esterlinas por gastar de más ilegalmente e informar de forma incorrecta sobre préstamos de Arron Banks por un total de 6 millones de libras esterlinas. [85] Se impusieron multas menores al grupo de campaña pro-UE Best for Our Future y a dos donantes sindicales por información inexacta. [86] En julio de 2018, Vote Leave fue multado con £61.000 por gastar en exceso, no declarar las finanzas compartidas con BeLeave y no cumplir con las órdenes de los investigadores. [87]

En noviembre de 2017, la Comisión Electoral inició una investigación sobre las denuncias de que Rusia había intentado influir en la opinión pública sobre el referéndum utilizando plataformas de redes sociales como Twitter y Facebook. [88]

En febrero de 2019, la Comisión Parlamentaria de Cultura, Medios de Comunicación, Deporte y Medios Digitales pidió una investigación sobre la “influencia extranjera, la desinformación, la financiación, la manipulación de votantes y el intercambio de datos” en la votación del Brexit. [89]

En julio de 2020, el Comité de Inteligencia y Seguridad del Parlamento publicó un informe en el que acusaba al gobierno del Reino Unido de evitar activamente investigar si Rusia interfería en la opinión pública. El informe no se pronunció sobre si las operaciones de información rusas habían tenido un impacto en el resultado. [90]

La retirada de la Unión Europea se rige por el artículo 50 del Tratado de la Unión Europea . Fue redactado originalmente por Lord Kerr de Kinlochard , [91] e introducido por el Tratado de Lisboa que entró en vigor en 2009. [92] El artículo establece que cualquier estado miembro puede retirarse "de conformidad con sus propios requisitos constitucionales" notificando al Consejo Europeo su intención de hacerlo. [93] La notificación desencadena un período de negociación de dos años, en el que la UE debe "negociar y concluir un acuerdo con el Estado [que abandona], estableciendo las modalidades de su retirada, teniendo en cuenta el marco de su futura relación con la Unión [Europea]". [94] Si no se llega a un acuerdo en el plazo de dos años, la membresía termina sin un acuerdo, a menos que se acuerde una extensión por unanimidad entre todos los estados de la UE, incluido el estado que se retira. [94] Por parte de la UE, el acuerdo debe ser ratificado por mayoría cualificada en el Consejo Europeo y por el Parlamento Europeo. [94]

La Ley del Referéndum de 2015 no requería expresamente que se invocara el Artículo 50, [94] pero antes del referéndum, el gobierno británico dijo que respetaría el resultado. [95] Cuando Cameron renunció después del referéndum, dijo que sería el primer ministro entrante quien invocaría el Artículo 50. [96] [97] La nueva primera ministra, Theresa May , dijo que esperaría hasta 2017 para invocar el artículo, con el fin de prepararse para las negociaciones. [98] En octubre de 2016, dijo que Gran Bretaña activaría el Artículo 50 en marzo de 2017, [99] y en diciembre obtuvo el apoyo de los parlamentarios para su calendario. [100]

En enero de 2017, el Tribunal Supremo del Reino Unido dictaminó en el caso Miller que el gobierno solo podía invocar el artículo 50 si estaba autorizado por una ley del parlamento para hacerlo. [101] Posteriormente, el gobierno presentó un proyecto de ley con ese fin, que se convirtió en ley el 16 de marzo como la Ley de la Unión Europea (Notificación de Retirada) de 2017. [ 102] El 29 de marzo, Theresa May activó el artículo 50 cuando Tim Barrow , el embajador británico ante la UE, entregó la carta de invocación al presidente del Consejo Europeo, Donald Tusk . Esto hizo que el 29 de marzo de 2019 fuera la fecha prevista para que el Reino Unido abandonara la UE. [103] [104]

En abril de 2017, Theresa May convocó elecciones generales anticipadas, celebradas el 8 de junio , en un intento de "fortalecer [su] mano" en las negociaciones; [105] El Partido Conservador, el Laborismo y el UKIP hicieron promesas en sus manifiestos de implementar el referéndum, el manifiesto laborista difiere en su enfoque de las negociaciones del Brexit, como ofrecer unilateralmente la residencia permanente a los inmigrantes de la UE. [106] [107] [108] Los manifiestos del Partido Liberal Demócrata y del Partido Verde propusieron una política de permanecer en la UE a través de un segundo referéndum . [109] [110] [111] El manifiesto del Partido Nacional Escocés (SNP) propuso una política de esperar el resultado de las negociaciones del Brexit y luego celebrar un referéndum sobre la independencia de Escocia . [112] [113]

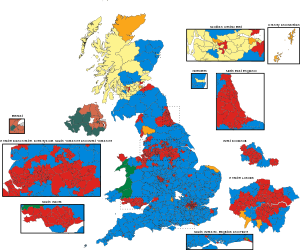

El resultado produjo un parlamento sin mayoría , los conservadores gobernantes ganaron votos y siguieron siendo el partido más grande, pero sin embargo perdieron escaños y su mayoría en la Cámara de los Comunes. El Partido Laborista ganó significativamente en votos y escaños, manteniendo su posición como el segundo partido más grande. Los demócratas liberales ganaron seis escaños a pesar de una ligera disminución en la cuota de votos en comparación con 2015. El Partido Verde mantuvo su único diputado, aunque también perdió cuota de votos a nivel nacional. Perdiendo votos y escaños fueron el SNP, que perdió 21 diputados, y el UKIP, que sufrió un cambio de -10,8% y perdió su único diputado. El Partido Unionista Democrático (DUP) y el Sinn Féin también ganaron votos y escaños. [114]

El 26 de junio de 2017, los conservadores y el DUP llegaron a un acuerdo de confianza y suministro por el cual el DUP respaldaría a los conservadores en votaciones clave en la Cámara de los Comunes durante el transcurso del parlamento. El acuerdo incluía una financiación adicional de 1.000 millones de libras para Irlanda del Norte, destacaba el apoyo mutuo para el Brexit y la seguridad nacional, expresaba el compromiso con el Acuerdo de Viernes Santo e indicaba que se mantendrían políticas como el triple bloqueo de las pensiones estatales y los pagos de combustible de invierno . [115] [116]

Antes de las negociaciones, May dijo que el gobierno británico no buscaría la membresía permanente en el mercado único , pondría fin a la jurisdicción del TJCE, buscaría un nuevo acuerdo comercial, pondría fin a la libre circulación de personas y mantendría el Área de Viaje Común con Irlanda . [117] La UE había adoptado sus directrices de negociación en mayo, [118] y nombró a Michel Barnier como negociador jefe. [119] La UE deseaba realizar las negociaciones en dos fases: primero, el Reino Unido aceptaría un compromiso financiero y beneficios de por vida para los ciudadanos de la UE en Gran Bretaña, y luego podrían comenzar las negociaciones sobre una relación futura. [120] En la primera fase, los estados miembros exigirían que el Reino Unido pagara una " factura de divorcio ", inicialmente estimada en £ 52 mil millones. [121] Los negociadores de la UE dijeron que se debe llegar a un acuerdo entre el Reino Unido y la UE para octubre de 2018. [122]

Las negociaciones comenzaron el 19 de junio de 2017. [119] Se establecieron grupos de negociación para tres temas: los derechos de los ciudadanos de la UE que viven en Gran Bretaña y viceversa; las obligaciones financieras pendientes de Gran Bretaña con la UE; y la frontera entre Irlanda del Norte y la República de Irlanda. [123] [124] [125] En diciembre de 2017, se alcanzó un acuerdo parcial. Aseguró que no habría una frontera dura en Irlanda, protegió los derechos de los ciudadanos del Reino Unido en la UE y de los ciudadanos de la UE en Gran Bretaña, y estimó que el acuerdo financiero sería de £ 35-39 mil millones. [126] May destacó que "nada está acordado hasta que todo esté acordado". [127] Después de este acuerdo parcial, los líderes de la UE acordaron pasar a la segunda fase de las negociaciones: discusión de la relación futura, un período de transición y un posible acuerdo comercial. [128]

En marzo de 2018, se acordó provisionalmente un período de transición de 21 meses y sus términos. [129] En junio de 2018, el Taoiseach irlandés Leo Varadkar dijo que había habido poco progreso en la cuestión fronteriza irlandesa —sobre la que la UE propuso un backstop , que entraría en vigor si no se había alcanzado un acuerdo comercial general al final del período de transición— y que era poco probable que hubiera una solución antes de octubre, cuando se acordaría todo el acuerdo. [130] En julio de 2018, el gobierno británico publicó el plan Chequers , que contenía sus objetivos para la relación futura que se determinaría en las negociaciones. El plan buscaba mantener el acceso británico al mercado único de bienes, pero no necesariamente de servicios, al tiempo que permitía una política comercial independiente . [131] El plan provocó renuncias en el gabinete, incluidas las del secretario del Brexit, David Davis [132] y el secretario de Asuntos Exteriores, Boris Johnson . [133]

El 13 de noviembre de 2018, los negociadores del Reino Unido y la UE acordaron el texto de un borrador del acuerdo de retirada, [134] y May consiguió el respaldo de su Gabinete al acuerdo al día siguiente, [135] aunque el Secretario del Brexit, Dominic Raab, renunció debido a "fallas fatales" en el acuerdo. [136] Se esperaba que la ratificación en el parlamento británico fuera difícil. [137] [138] [139] El 25 de noviembre, los 27 líderes de los países restantes de la UE respaldaron el acuerdo. [137] [138]

El 10 de diciembre de 2018, la Primera Ministra pospuso la votación en la Cámara de los Comunes sobre su acuerdo para el Brexit. Esto se produjo minutos después de que la Oficina de la Primera Ministra confirmara que la votación se llevaría a cabo. [140] Ante la perspectiva de una derrota en la Cámara de los Comunes, esta opción le dio a May más tiempo para negociar con los diputados conservadores y la UE, a pesar de que habían descartado más discusiones. [141] La decisión fue recibida con pedidos de muchos parlamentarios laboristas galeses de una moción de censura al Gobierno. [142]

También el 10 de diciembre de 2018, el Tribunal de Justicia de la Unión Europea (TJUE) dictaminó que el Reino Unido podía revocar unilateralmente su notificación de retirada, siempre que siguiera siendo miembro y no hubiera llegado a un acuerdo de retirada. La decisión de hacerlo debería ser "inequívoca e incondicional" y "seguir un proceso democrático". [143] Si los británicos revocaran su notificación, seguirían siendo miembros de la UE en virtud de sus actuales condiciones de membresía. El caso fue presentado por políticos escoceses y remitido al TJUE por el Tribunal de Sesiones de Escocia . [144]

El Grupo de Investigación Europeo (ERG), un grupo de apoyo a la investigación de parlamentarios conservadores euroescépticos, se opuso al tratado de acuerdo de retirada propuesto por el Primer Ministro. Sus miembros se opusieron firmemente a la inclusión en el Acuerdo de Retirada del mecanismo de salvaguarda irlandés . [145] [146] Los miembros del ERG también se opusieron al acuerdo financiero propuesto por 39.000 millones de libras con la UE y afirmaron que el acuerdo daría lugar a que el Reino Unido aceptara seguir cumpliendo las normas de la UE en importantes áreas políticas; y a la jurisdicción continua del TJCE sobre la interpretación del acuerdo y del derecho europeo todavía aplicable al Reino Unido. [147] [148]

El 15 de enero de 2019, la Cámara de los Comunes votó 432 a 202 en contra del acuerdo, lo que fue la mayoría más grande jamás obtenida contra un gobierno del Reino Unido. [149] [150] Poco después, la oposición presentó una moción de censura al Gobierno de Su Majestad , [151] que fue rechazada por 325 votos a 306. [152]

El 24 de febrero, la primera ministra May propuso que la próxima votación sobre el acuerdo de retirada se realizaría el 12 de marzo de 2019, 17 días antes de la fecha del Brexit. [153] El 12 de marzo, la propuesta fue derrotada por 391 votos contra 242, una pérdida de 149 votos, frente a los 230 que había recibido cuando se propuso el acuerdo en enero. [154]

El 18 de marzo de 2019, el Presidente informó a la Cámara de los Comunes que solo se podía realizar una tercera votación significativa sobre una moción que fuera significativamente diferente de la anterior, citando precedentes parlamentarios que se remontan a 1604. [155]

El Acuerdo de Retirada fue devuelto a la Cámara sin los acuerdos adjuntos el 29 de marzo. [156] La moción del Gobierno de apoyo al Acuerdo de Retirada fue derrotada por 344 votos contra 286, una pérdida de 58 votos, frente a los 149 que había cuando se había propuesto el acuerdo el 12 de marzo. [157]

El 20 de marzo de 2019, la Primera Ministra escribió al Presidente del Consejo Europeo, Tusk, solicitando que el Brexit se pospusiera hasta el 30 de junio de 2019. [158] El 21 de marzo de 2019, May presentó su caso en una cumbre del Consejo Europeo en Bruselas. Después de que May abandonara la reunión, una discusión entre los líderes restantes de la UE resultó en el rechazo de la fecha del 30 de junio y se ofreció en su lugar la opción de dos nuevas fechas alternativas para el Brexit. El 22 de marzo de 2019, las opciones de extensión fueron acordadas entre el gobierno británico y el Consejo Europeo. [159] La primera alternativa ofrecida fue que si los parlamentarios rechazaban el acuerdo de May en la próxima semana, el Brexit se produciría antes del 12 de abril de 2019, con o sin acuerdo, o alternativamente se solicitaría otra extensión y se daría el compromiso de participar en las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo de 2019 . La segunda alternativa que se ofreció fue que si los parlamentarios aprobaban el acuerdo de May, el Brexit se produciría el 22 de mayo de 2019. La última fecha era el día antes del inicio de las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo. [160] Después de que el gobierno considerara injustificadas las preocupaciones sobre la legalidad del cambio propuesto (porque contenía dos posibles fechas de salida) el día anterior, [161] el 27 de marzo de 2019 tanto los Lores (sin votación) [162] como los Comunes (por 441 a 105) aprobaron el instrumento estatutario que cambia la fecha de salida al 22 de mayo de 2019 si se aprueba un acuerdo de retirada, o al 12 de abril de 2019 si no se aprueba. [163] La enmienda se convirtió en ley a las 12:40 p. m. del día siguiente. [159]

Tras el fracaso del Parlamento británico en aprobar el Acuerdo de Retirada antes del 29 de marzo, el Reino Unido tuvo que abandonar la UE el 12 de abril de 2019. El 10 de abril de 2019, las conversaciones nocturnas en Bruselas dieron como resultado una nueva prórroga, hasta el 31 de octubre de 2019; Theresa May había solicitado nuevamente una prórroga solo hasta el 30 de junio. Según los términos de esta nueva prórroga, si el Acuerdo de Retirada se aprobaba antes de octubre, el Brexit se produciría el primer día del mes siguiente. El Reino Unido estaría entonces obligado a celebrar elecciones al Parlamento Europeo en mayo o abandonar la UE el 1 de junio sin un acuerdo. [164] [165]

Al conceder las prórrogas del artículo 50, la UE adoptó una postura de negarse a "reabrir" (es decir, renegociar) el Acuerdo de Retirada. [166] Después de que Boris Johnson se convirtiera en primer ministro el 24 de julio de 2019 y se reuniera con los líderes de la UE, la UE cambió su postura. El 17 de octubre de 2019, tras las "conversaciones de túnel" entre el Reino Unido y la UE, [167] se acordó un acuerdo de retirada revisado a nivel de negociadores, y fue respaldado por el gobierno británico y la Comisión de la UE. [168] El acuerdo revisado contenía un nuevo Protocolo de Irlanda del Norte , así como modificaciones técnicas a los artículos relacionados. [8] Además, también se revisó la Declaración Política. [169] El acuerdo revisado y la declaración política fueron respaldados por el Consejo Europeo más tarde ese día. [170] Para entrar en vigor, necesitaba ser ratificado por el Parlamento Europeo y el Parlamento del Reino Unido . [171]

El Parlamento británico aprobó la Ley de 2019 sobre la retirada de la Unión Europea (n.º 2) , que recibió la sanción real el 9 de septiembre de 2019, obligando al Primer Ministro a solicitar una tercera prórroga si no se ha llegado a un acuerdo en la próxima reunión del Consejo Europeo en octubre de 2019. [172] Para que se conceda dicha prórroga si la solicita el Primer Ministro, sería necesario que haya un acuerdo unánime de todos los demás jefes de gobierno de la UE. [173] El 28 de octubre de 2019, la UE acordó la tercera prórroga, con una nueva fecha límite de retirada del 31 de enero de 2020. [174] El "día de salida" en la legislación británica se modificó a esta nueva fecha mediante un instrumento estatutario el 30 de octubre de 2019. [175]

Después de que Johnson no pudiera inducir al Parlamento a aprobar una versión revisada del acuerdo de retirada para finales de octubre, optó por convocar elecciones anticipadas . Debido a que tres mociones para una elección general anticipada en virtud de la Ley de Parlamentos de Plazo Fijo de 2011 no lograron alcanzar la supermayoría de dos tercios necesaria para su aprobación, en su lugar, para eludir la ley existente, el Gobierno presentó un " proyecto de ley electoral " que sólo necesitaba una mayoría simple de diputados para votar a favor en la Cámara de los Comunes, que fue aprobado por 438 a 20, fijando la fecha de las elecciones para el jueves 12 de diciembre. [176] Las encuestas de opinión hasta el día de las elecciones mostraron una firme ventaja de los conservadores contra los laboristas durante toda la campaña. [177]

En el período previo a las elecciones generales del 12 de diciembre de 2019, el Partido Conservador se comprometió a abandonar la UE con el acuerdo de retirada negociado en octubre de 2019. El Partido Laborista prometió renegociar el acuerdo mencionado y celebrar un referéndum, dejando que los votantes elijan entre el acuerdo renegociado y permanecer en la UE. Los Demócratas Liberales prometieron revocar el Artículo 50, mientras que el SNP tenía la intención de celebrar un segundo referéndum, sin embargo, revocando el Artículo 50 si la alternativa era una salida sin acuerdo. El DUP apoyó el Brexit, pero buscaría cambiar las partes relacionadas con Irlanda del Norte con las que no estaba satisfecho. Plaid Cymru y el Partido Verde respaldaron un segundo referéndum, creyendo que el Reino Unido debería permanecer en la UE. El Partido del Brexit fue el único partido importante que se presentó a las elecciones que quería que el Reino Unido abandonara la UE sin un acuerdo. [178]

Las elecciones produjeron un resultado decisivo para Boris Johnson, ya que los conservadores ganaron 365 escaños (obtuvieron 47) y una mayoría general de 80 escaños, mientras que el Partido Laborista sufrió su peor derrota electoral desde 1935, tras perder 60 escaños, lo que les dejó con 202 escaños y solo un escaño en Escocia . Los liberaldemócratas ganaron solo 11 escaños y su líder, Jo Swinson, perdió su propio escaño. El Partido Nacional Escocés ganó 48 escaños después de ganar 14 escaños en Escocia.

El resultado rompió el punto muerto en el Parlamento del Reino Unido y puso fin a la posibilidad de celebrar un referéndum sobre el acuerdo de retirada y garantizó que el Reino Unido abandonaría la Unión Europea el 31 de enero de 2020.

.jpg/440px-Westminster_(49470617471).jpg)

Posteriormente, el gobierno presentó un proyecto de ley para ratificar el acuerdo de retirada. El proyecto fue aprobado en segunda lectura en la Cámara de los Comunes por 358 votos a favor y 234 en contra el 20 de diciembre de 2019 [179] y se convirtió en ley el 23 de enero de 2020 como la Ley de la Unión Europea (Acuerdo de Retirada) de 2020 [180] .

El acuerdo de retirada recibió el respaldo del comité constitucional del Parlamento Europeo el 23 de enero de 2020, lo que generó expectativas de que todo el parlamento lo aprobara en una votación posterior. [181] [182] [183] Al día siguiente, Ursula von der Leyen y Charles Michel firmaron el acuerdo de retirada en Bruselas, y fue enviado a Londres, donde Boris Johnson lo firmó. [11] El Parlamento Europeo dio su consentimiento a la ratificación el 29 de enero por 621 votos contra 49. [184] [12] Inmediatamente después de la aprobación de la votación, los miembros del Parlamento Europeo se tomaron de las manos y cantaron Auld Lang Syne . [185] El Consejo de la Unión Europea concluyó la ratificación de la UE al día siguiente. [186] A las 11 pm GMT del 31 de enero de 2020, la membresía del Reino Unido en la Unión Europea terminó, 47 años después de haberse unido. [13] Como confirmó el Tribunal de Justicia en el asunto EP v Préfet du Gers , [187] todos los nacionales británicos dejaron de ser ciudadanos de la Unión. [188]

Tras la salida británica el 31 de enero de 2020, el Reino Unido entró en un período de transición durante el resto de 2020. El comercio, los viajes y la libertad de movimiento se mantuvieron prácticamente sin cambios durante este período. [189]

El Acuerdo de Retirada sigue aplicándose después de esta fecha. [190] Este acuerdo otorga libre acceso de mercancías entre Irlanda del Norte y la República de Irlanda, siempre que se realicen controles a las mercancías que entran en Irlanda del Norte procedentes del resto del Reino Unido. El Gobierno británico intentó dar marcha atrás en este compromiso [191] aprobando el proyecto de ley sobre el mercado interior : legislación interna en el Parlamento británico. En septiembre, el secretario de Estado para Irlanda del Norte, Brandon Lewis, dijo:

Le diría a mi honorable amigo que sí, que esto viola el derecho internacional de una manera muy específica y limitada. [192]

lo que llevó a la dimisión de Sir Jonathan Jones , secretario permanente del Departamento Jurídico del Gobierno [193] y de Lord Keen , el oficial jurídico de Escocia. [194] La Comisión Europea inició acciones legales. [190]

Durante el período de transición, David Frost y Michel Barnier continuaron negociando un acuerdo comercial permanente . [195] El 24 de diciembre de 2020, ambas partes anunciaron que se había llegado a un acuerdo. [196] El acuerdo fue aprobado por ambas cámaras del parlamento británico el 30 de diciembre y recibió la sanción real en las primeras horas del día siguiente. En la Cámara de los Comunes, los conservadores gobernantes y el principal partido de oposición, el laborista, votaron a favor del acuerdo, mientras que todos los demás partidos de la oposición votaron en contra. [197] El período de transición concluyó según sus términos la noche siguiente. [198] Después de que el Reino Unido dijera que extendería unilateralmente un período de gracia que limitaría los controles al comercio entre Irlanda del Norte y Gran Bretaña, el Parlamento Europeo pospuso la fijación de una fecha para ratificar el acuerdo. [199] La votación se programó posteriormente para el 27 de abril, cuando se aprobó con una abrumadora mayoría de votos. [200] [201]

Hasta el 1 de julio de 2021 se aplicaba un régimen aduanero transitorio. Durante este período, los comerciantes que importaban mercancías estándar de la UE al Reino Unido podían aplazar la presentación de sus declaraciones aduaneras y el pago de los derechos de importación a la HMRC hasta seis meses. Este acuerdo simplificó y evitó la mayoría de los controles de importación durante los primeros meses de la nueva situación y fue diseñado para facilitar el comercio interno durante la crisis sanitaria de la COVID-19 y evitar grandes perturbaciones en las cadenas de suministro nacionales a corto plazo. [202] Tras los informes de que la infraestructura fronteriza no estaba lista, el gobierno del Reino Unido pospuso aún más los controles de importación de la UE al Reino Unido hasta finales de año para evitar problemas de suministro durante la actual crisis de la COVID. [203] A esto le siguió otro retraso de los controles de importación, en una situación de escasez de conductores de camiones; está previsto que los controles se introduzcan gradualmente durante 2022. [204]

En octubre de 2016, Theresa May prometió un "Gran Proyecto de Ley de Derogación", que derogaría la Ley de las Comunidades Europeas de 1972 y restablecería en la legislación británica todas las disposiciones previamente vigentes en virtud del derecho de la UE. Posteriormente, se lo rebautizó como Proyecto de Ley de Retirada de la Unión Europea y se presentó en la Cámara de los Comunes el 13 de julio de 2017. [205]

El 12 de septiembre de 2017, el proyecto de ley pasó su primera votación y segunda lectura por un margen de 326 votos a favor y 290 en contra en la Cámara de los Comunes. [206] El proyecto de ley fue modificado nuevamente en una serie de votaciones en ambas Cámaras. Después de que la ley se convirtiera en ley el 26 de junio de 2018, el Consejo Europeo decidió el 29 de junio renovar su llamamiento a los Estados miembros y a las instituciones de la Unión Europea para que intensificaran su labor de preparación a todos los niveles y para todos los resultados. [207]

La Ley de Retirada fijó el plazo hasta el 21 de enero de 2019 para que el Gobierno decidiera cómo proceder si las negociaciones no habían llegado a un acuerdo de principio sobre los acuerdos de retirada y el marco para la futura relación entre el Reino Unido y la UE; mientras que, alternativamente, hizo que la futura ratificación del acuerdo de retirada como tratado entre el Reino Unido y la UE dependiera de la promulgación previa de otra ley del Parlamento para aprobar los términos finales de la retirada cuando se completaran las negociaciones del Brexit . En cualquier caso, la Ley no alteró el período de dos años para la negociación permitido por el artículo 50 que finalizaba a más tardar el 29 de marzo de 2019 si el Reino Unido no había ratificado para entonces un acuerdo de retirada o acordado una prolongación del período de negociación. [208]

La Ley de Retirada, que se convirtió en ley en junio de 2018, preveía diversas posibilidades, incluida la de no negociar un acuerdo. Autoriza al gobierno a poner en vigor, mediante una orden dictada en virtud del artículo 25, las disposiciones que fijaban el "día de salida" y la derogación de la Ley de las Comunidades Europeas de 1972, pero el día de salida debe ser el mismo día y hora en que los Tratados de la UE dejaron de aplicarse al Reino Unido. [209]

El día de salida fue el final del 31 de enero de 2020 CET (23:00 GMT ). [175] La Ley de la Unión Europea (Retirada) de 2018 (modificada por un instrumento legal británico el 11 de abril de 2019), en la sección 20 (1), definió el "día de salida" como las 23:00 horas del 31 de octubre de 2019. [159] Originalmente, el "día de salida" se definió como las 23:00 horas del 29 de marzo de 2019 GMT ( UTC+0 ). [208] [210] [211]

En un informe publicado en marzo de 2017 por el Instituto de Gobierno se comentó que, además del proyecto de ley sobre la retirada de la Unión Europea, se necesitaría legislación primaria y secundaria para cubrir las lagunas en áreas de políticas como las aduanas, la inmigración y la agricultura. [212] El informe también comentó que el papel de las legislaturas descentralizadas no estaba claro y podría causar problemas, y que podrían necesitarse hasta 15 nuevos proyectos de ley adicionales sobre el Brexit, lo que implicaría una priorización estricta y limitar el tiempo parlamentario para el examen en profundidad de la nueva legislación. [213]

En 2016 y 2017, la Cámara de los Lores publicó una serie de informes sobre temas relacionados con el Brexit, entre ellos:

La Ley de Salvaguardias Nucleares de 2018 , relativa a la retirada de Euratom, se presentó al Parlamento en octubre de 2017. La ley contiene disposiciones sobre salvaguardias nucleares y para fines relacionados. El Secretario de Estado puede, mediante reglamentos ("reglamentos de salvaguardias nucleares"), establecer disposiciones con el fin de (a) garantizar que los materiales, instalaciones o equipos nucleares calificados estén disponibles únicamente para su uso en actividades civiles (ya sea en el Reino Unido o en otro lugar), o (b) dar efecto a las disposiciones de un acuerdo internacional pertinente. [214]

La Ley de la Unión Europea (Acuerdo de Retirada) de 2020 establece disposiciones legales para ratificar el Acuerdo de Retirada del Brexit e incorporarlo al derecho interno del Reino Unido. [215] El proyecto de ley fue presentado por primera vez [216] por el gobierno el 21 de octubre de 2019. Este proyecto de ley no se debatió más y caducó el 6 de noviembre cuando el parlamento se disolvió en preparación para las elecciones generales de 2019. El proyecto de ley se volvió a presentar inmediatamente después de las elecciones generales y fue el primer proyecto de ley que se presentó ante la Cámara de los Comunes en la primera sesión del 58.º Parlamento, [217] con cambios con respecto al proyecto de ley anterior, por el gobierno reelegido y se leyó por primera vez el 19 de diciembre, inmediatamente después de la primera lectura del Proyecto de Ley de Outlawries y antes de que comenzara el debate sobre el Discurso de la Reina . La segunda lectura tuvo lugar el 20 de diciembre y la tercera el 9 de enero de 2020. Esta ley recibió la sanción real el 23 de enero de 2020, nueve días antes de que el Reino Unido abandonara la Unión Europea .

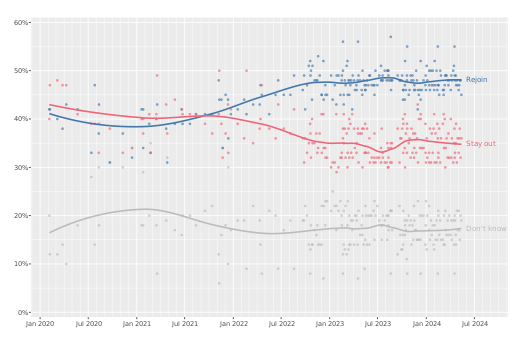

Las encuestas de opinión en general mostraron una caída inicial en el apoyo al Brexit desde el referéndum hasta fines de 2016, cuando las respuestas se dividieron equitativamente entre apoyo y oposición. El apoyo aumentó nuevamente a una pluralidad, que se mantuvo hasta las elecciones generales de 2017. Desde entonces, las encuestas de opinión tendieron a mostrar una pluralidad de apoyo a permanecer en la UE o a la opinión de que el Brexit fue un error, con el margen estimado aumentando hasta una pequeña disminución en 2019 (a 53% Permanecer: 47% Salir, a octubre de 2019 [update]). [218] Esto parece deberse en gran medida a una preferencia por permanecer en la UE entre aquellos que no votaron en el referéndum de 2016 (se estima que 2,5 millones de los cuales, a octubre de 2019 [update], eran demasiado jóvenes para votar en ese momento). [219] [220] Otras razones sugeridas incluyen ligeramente más votantes del Brexit que del Brexit (14% y 12% de cada uno, respectivamente, a octubre de 2019 [update]) [221], cambios en la forma en que votarían (particularmente en las áreas laboristas ) y las muertes de votantes mayores, [218] la mayoría de los cuales votaron a favor de abandonar la UE. Una estimación de los cambios demográficos (ignorando otros efectos) implica que si se hubiera celebrado un referéndum de la UE en octubre de 2019, [update]habría habido entre 800.000 y 900.000 votantes menos del Brexit y entre 600.000 y 700.000 votantes más del Brexit, lo que habría dado como resultado una mayoría del Brexit. [219]

En marzo de 2019, una petición presentada en el sitio web de peticiones del Parlamento británico, en la que se pedía al gobierno que revocara el Artículo 50 y permaneciera en la UE, alcanzó un nivel récord de más de 6,1 millones de firmas. [222] [223]

Las encuestas de YouGov han mostrado un descenso gradual pero progresivo de la percepción pública de los beneficios del Brexit, y el margen general de sentimiento sobre la corrección de la decisión del Brexit ha disminuido de ligeramente positivo en 2016 a -11% en 2022. [224] Una encuesta de mayo de 2022 mostró que la mayoría de los encuestados que expresaron una opinión pensaban que el Brexit había ido "mal" o "muy mal". [225] Un nuevo estudio mostró que desde el Brexit, los ciudadanos de otras naciones europeas estaban más en contra de abandonar la UE de lo que habían estado desde 2016. [226] Una encuesta de enero de 2023 en el Reino Unido también reflejó estas cifras, con un 54% de los encuestados que creían que el país estaba equivocado al abandonar la Unión Europea, mientras que el 35% de los encuestados creía que era la decisión correcta. [227] Un promedio de seis encuestas realizadas en junio y julio de 2023 muestra que el 58% de los votantes están a favor de reincorporarse a la UE y el 42% de los votantes están en contra. [228]

Desde 2020, los encuestadores han preguntado a los encuestados cómo votarían en un posible segundo referéndum para reincorporarse a la UE.

El 19 de diciembre de 2018, la Comisión Europea reveló su Plan de Acción de Contingencia en caso de una salida sin acuerdo en sectores específicos, en caso de que el Reino Unido abandone la UE "dentro de 100 días". [229]

A raíz de la votación del Reino Unido a favor de abandonar la Unión Europea, la Primera Ministra May creó el Departamento de Comercio Internacional (DIT) para alcanzar y ampliar los acuerdos comerciales entre el Reino Unido y los estados no pertenecientes a la UE, poco después de que asumiera el cargo el 13 de julio de 2016. [230] En 2017, empleaba a unos 200 negociadores comerciales [231] y estaba supervisado por el entonces Secretario de Estado de Comercio Internacional Liam Fox . En marzo de 2019, el gobierno británico anunció que reduciría muchos aranceles de importación a cero, en caso de un Brexit sin acuerdo. [232] La Confederación de la Industria Británica dijo que la medida sería un "mazazo para nuestra economía", [233] [234] [235] y la Unión Nacional de Agricultores también fue muy crítica. [236] Además, el plan parecía violar las normas estándar de la OMC. [237] [238] [239]

El 2 de junio de 2020, la canciller alemana, Angela Merkel, afirmó que la Unión Europea debe prepararse para el posible fracaso de las negociaciones comerciales del Brexit con el Reino Unido . Añadió que se estaban acelerando las negociaciones para intentar llegar a un acuerdo que pudiera ratificarse antes de fin de año. Su advertencia se produjo cuando venció la fecha límite para ampliar las negociaciones, que se espera que finalicen el 31 de diciembre con o sin acuerdo. [240]

Se han presentado litigios para explorar los fundamentos constitucionales sobre los que se sustenta el Brexit después del caso R (Miller) contra el Secretario de Estado para la Salida de la Unión Europea (conocido simplemente como el "caso Miller") y la Ley de Notificación de 2017:

... que el Parlamento, y en particular la Cámara de los Comunes como representantes democráticamente elegidos del pueblo, tiene derecho a tener voz y voto en la forma en que se produce ese cambio es indiscutible. [244]

— Tribunal Supremo del Reino Unido (UKSC/2019/41)

Muchos de los efectos del Brexit dependían de si el Reino Unido se retiraba con un acuerdo de retirada o antes de que se ratificara un acuerdo ( Brexit "sin acuerdo" ). [251] En 2017, el Financial Times dijo que había aproximadamente 759 acuerdos internacionales, que abarcaban 168 países no pertenecientes a la UE, de los que el Reino Unido ya no sería parte al abandonar la UE. [252]

Los economistas especularon que el Brexit tendría un impacto perjudicial en las economías del Reino Unido y al menos en parte de la UE27. En particular, hubo un amplio consenso entre los economistas y en la literatura económica de que el Brexit probablemente reduciría el ingreso per cápita real del Reino Unido en el mediano y largo plazo, y que el referéndum del Brexit en sí dañaría la economía. [79] [253] [254] Los estudios encontraron que la incertidumbre inducida por el Brexit redujo el PIB británico, el ingreso nacional británico, la inversión de las empresas, el empleo y el comercio internacional británico a partir de junio de 2016. [255] [256] [257]

Un análisis de 2019 encontró que las empresas británicas aumentaron sustancialmente la deslocalización a la UE después del referéndum del Brexit, mientras que las empresas europeas redujeron las nuevas inversiones en el Reino Unido. [258] [259] El análisis del Brexit del gobierno británico, filtrado en enero de 2018, mostró que el crecimiento económico británico se frenaría entre un 2 y un 8 % durante los 15 años posteriores al Brexit, cantidad que depende del escenario de salida. [260] [261] Los economistas advirtieron que el futuro de Londres como centro financiero internacional dependía de los acuerdos de pasaporte con la UE. [262] [263] Los activistas y políticos pro-Brexit han abogado por negociar acuerdos comerciales y migratorios con los países " CANZUK " ( Canadá , Australia , Nueva Zelanda y el Reino Unido) [264] [265] , pero los economistas han dicho que los acuerdos comerciales con esos países serían mucho menos valiosos para el Reino Unido que la membresía en la UE. [266] [267] [268] Los estudios proyectaron que el Brexit exacerbaría la desigualdad económica regional en el Reino Unido, afectando más duramente a las regiones que ya estaban en dificultades. [269]

El 11 de enero de 2024, la Alcaldía de Londres publicó " El alcalde destaca el daño del Brexit a la economía de Londres ". [270] El comunicado cita el informe independiente de Cambridge Econometrics que indica que Londres tiene casi 300.000 puestos de trabajo menos y, a nivel nacional, dos millones de puestos de trabajo menos como consecuencia directa del Brexit. [270] Se reconoce que el Brexit es un contribuyente clave a la crisis del coste de vida de 2023, ya que el ciudadano medio estará casi 2.000 libras peor y el londinense medio casi 3.400 libras peor en 2023 como resultado del Brexit. [270] Además, el Valor Añadido Bruto real del Reino Unido fue aproximadamente 140.000 millones de libras menos en 2023 de lo que habría sido si el Reino Unido hubiera permanecido en el Mercado Único. [270]

El impacto potencial en la frontera entre Irlanda del Norte y la República de Irlanda ha sido un tema polémico. Desde 2005, la frontera había sido esencialmente invisible. [271] Después del Brexit, se convirtió en la única frontera terrestre entre el Reino Unido y la UE [272] (sin contar las fronteras terrestres que los estados de la UE España y Chipre tienen con los Territorios Británicos de Ultramar ). Todas las partes involucradas acordaron que se debía evitar una frontera dura, [273] porque podría comprometer el Acuerdo de Viernes Santo que puso fin al conflicto de Irlanda del Norte . [274] [275] [276] Para prevenir esto, la UE propuso un "acuerdo de respaldo" que mantendría al Reino Unido en la Unión Aduanera y a Irlanda del Norte en algunos aspectos del Mercado Único hasta que se encontrara una solución duradera. [277] El Parlamento del Reino Unido rechazó esta propuesta. Después de más negociaciones en el otoño de 2019 , se acordó un modelo alternativo, el Protocolo Irlanda/Irlanda del Norte, entre el Reino Unido y la UE. En virtud del Protocolo, Irlanda del Norte queda formalmente fuera del mercado único de la UE, pero las normas de libre circulación de mercancías de la UE y las normas de la Unión Aduanera de la UE siguen aplicándose; esto garantiza que no haya controles ni inspecciones aduaneras entre Irlanda del Norte y el resto de la isla. En lugar de una frontera terrestre entre Irlanda e Irlanda del Norte, el Protocolo ha creado una « frontera aduanera de facto en el mar de Irlanda » para las mercancías procedentes de (pero no destinadas a) Gran Bretaña, [278] [279] para inquietud de destacados unionistas . [280]

After the Brexit referendum, the Scottish Government – led by the Scottish National Party (SNP) – planned another independence referendum because Scotland voted to remain in the EU while England and Wales voted to leave.[281] It had suggested this before the Brexit referendum.[282] The First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, requested a referendum be held before the UK's withdrawal,[283] but the British Prime Minister rejected this timing, but not the referendum itself.[284] At the referendum in 2014, 55% of voters had decided to remain in the UK, but the referendum on Britain's withdrawal from the EU was held in 2016, with 62% of Scottish voters against it. In March 2017, the Scottish Parliament voted in favour of holding another independence referendum. Sturgeon called for a "phased return" of an independent Scotland back to the EU.[285] In 2017, if Northern Ireland remained associated with the EU – for example, by remaining in the Customs Union – some analysts argued Scotland would also insist on special treatment.[286] However, in that event, the only part of the United Kingdom which would receive unique treatment was Northern Ireland.[287]

On 21 March 2018, the Scottish Parliament passed the Scottish Continuity Bill.[288] This was passed due to stalling negotiations between the Scottish Government and the British Government on where powers within devolved policy areas should lie after Brexit. The Act allowed for all devolved policy areas to remain within the remit of the Scottish Parliament and reduced the executive power upon exit day that the UK Withdrawal Bill provides for Ministers of the Crown.[289] The bill was referred to the UK Supreme Court, which found that it could not come into force as the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, which received royal assent between the Scottish Parliament passing its bill and the Supreme Court's judgement, designated itself under schedule 4 of the Scotland Act 1998 as unamendable by the Scottish Parliament.[290] The bill has therefore not received royal assent.[291]

Gibraltar, a British Overseas Territory bordering Spain, is affected by Brexit too. Spain asserts a territorial claim on Gibraltar. After the referendum, Spain's Foreign Minister renewed calls for joint Spanish–British control.[292] In late 2018, the British and Spanish governments agreed that any dispute over Gibraltar would not affect Brexit negotiations,[293] and the British government agreed that UK–EU treaties made after Brexit would not automatically apply to Gibraltar.[294] In December 2020, Spain and the UK reached an agreement in principle on future arrangements for Brexit and invited the European Commission to formalise it as a treaty.

The French and British governments say they remain committed to the Le Touquet Agreement, which lets UK border checks be completed in France, and vice versa (juxtaposed controls).[295] The two governments signed the Sandhurst Treaty in January 2018, which will shorten the time taken to process migrants attempting to reach the UK from Calais, from six months to one month. The UK also announced it will invest a further £44.5 million on border security at the English Channel.[295]

Brexit caused the European Union to lose its second-largest economy, its third-most populous country,[296] and the second-largest net contributor to the EU budget.[297]

The UK is no longer a shareholder in the European Investment Bank, where it had 16% of the shares.[298] The European Investment Bank's Board of Governors decided that the remaining member states would proportionally increase their capital subscriptions to maintain the same level of overall subscribed capital (EUR 243.3 billion).[299] As of March 2020, the subscribed capital of the EIB had increased by an additional EUR 5.5 billion, following the decision by two member states to increase their capital subscriptions (Poland and Romania). The EIB's total subscribed capital thus amounted to EUR 248.8 billion. Brexit did not impact the EIB Group's AAA credit rating.[300]

Analyses indicated that the departure of the relatively economically liberal UK would reduce the ability of remaining economically liberal countries to block measures in the Council of the EU.[301][302] In 2019, ahead of Brexit, the European Medicines Agency and European Banking Authority moved their headquarters from London to Amsterdam and Paris, respectively.[303][304][305]

The UK has left the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP),[306] which provides government financial support to farmers in the EU.[307] Brexit allowed the UK to develop its own agriculture policy[308] and the Agriculture Act 2020 replaced the CAP with a new system.[309] The UK also left the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP)[310] that lets all EU countries fish within 12 nautical miles of the British coast[311] and lets the EU set catch quotas.[312] The combined EU fishing fleets landed about six million tonnes of fish per year, as of 2016,[313] about half of which were from British waters.[314] By leaving the CFP, the UK could develop its own fisheries policy.[312] The UK did also leave the London Fisheries Convention that lets Irish, French, Belgian, Dutch and German vessels fish within six nautical miles of the UK's coast.[315]

Brexit poses challenges to British academia and research, as the UK loses research funding from EU sources and sees a reduction in students from the EU. Academic institutions find it harder to hire researchers from the EU and British students will face greater difficulties with studying abroad in the EU.[316] The UK was a member of the European Research Area and likely to wish to remain an associated member following Brexit.[317] The British government has guaranteed funding for research currently funded by EU.[318]

An early 2019 study found that Brexit would deplete the National Health Service (NHS) workforce, create uncertainties regarding care for British nationals living in the EU, and put at risk access to vaccines, equipment, and medicines.[319] The Department of Health and Social Care has said it has taken steps to ensure the continuity of medical supplies after Brexit.[320] The number of non-British EU nurses registering with the NHS fell from 1,304 in July 2016 to 46 in April 2017.[321][needs update]In June 2016, 58,702 NHS staff recorded a non-British EU nationality, and in June 2022, 70,735 NHS staff recorded an EU nationality. However, "to present this as the full story would be misleading, because there are over 57,000 more staff for whom nationality is known now than in 2016"[322][323]

Under the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, EU laws will no longer have supremacy over British laws after Brexit.[324] To maintain continuity, the Act converts EU law into British law as "retained EU law". After Brexit, the British parliament (and the devolved legislatures) can decide which elements of that law to keep, amend or repeal.[324] Furthermore, British courts will no longer be bound by the judgments of the EU Court of Justice after Brexit.

After Brexit, the UK is able to control immigration from the EU and EEA,[325] as it can end EU freedom of movement. The current British government intends to replace it with a new system[needs update] The government's 2018 white paper proposes a "skills-based immigration system" that prioritises skilled migrants. EU and EEA citizens already living in the UK can continue living there after Brexit by applying to the EU Settlement Scheme, which began in March 2019. Irish citizens will not have to apply to the scheme.[326][327][328] Studies estimate that Brexit and the end of free movement will likely result in a large decline in immigration from EEA countries to the UK.[329][330] After Brexit, any foreigner wanting to do so more than temporarily would need a work permit.[331][332]

By leaving the EU, the UK would leave the European Common Aviation Area (ECAA), a single market in commercial air travel,[333] but could negotiate a number of different future relationships with the EU.[333] British airlines would still have permission to operate within the EU with no restrictions, and vice versa. The British government seeks continued participation in the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA).[333] The UK has its own air service agreements with 111 countries, which permit flights to-and-from the country, and further 17 countries through its EU membership.[334] These have since been replaced. Ferries will continue, but with obstacles such as customs checks.[335] New ferry departures between the Republic of Ireland and the European mainland have been established.[335] As of August 2020[update], the government's Goods Vehicle Movement Service, an IT system essential to post-Brexit goods movements, was still only in the early stages of beta testing, with four months to go before it is required to be in operation.[336]

Concerns were raised by European lawmakers, including Michel Barnier, that Brexit might create security problems for the UK given that its law enforcement and counter-terrorism forces would no longer have access to the EU's security databases.[337]

Some analysts have suggested that the severe economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK has masked the economic impact of Brexit in 2021.[338] In December 2021, the Financial Times quoted a range of economists as saying that the economic impact of Brexit on the UK economy and living standards "appears to be negative but uncertain".[339] According to the Office for Budget Responsibility, the new trade agreement between the EU and UK could, over time, result in a 4% reduction in British productivity, compared with its level had the 2016 EU referendum gone the other way.[340]

Brexit was widely described as a factor contributing to the 2021 United Kingdom natural gas supplier crisis, in which panic buying led to serious disruption of road fuel supplies across the UK, as it exacerbated the UK's shortage of HGV drivers.[341][342][343] In a July 2021 report, the Road Haulage Association estimated the UK faced a shortage of up to 100,000 truck drivers.[344][345][346]

Forecasts were made at the time of the referendum that Brexit would impose trade barriers, leading to a decline in trade between the United Kingdom and the European Union: however after a dip in 2020 as result of worldwide lockdowns, by 2022 trade in both directions had risen to higher levels than before Brexit.[347]

Brexit has inspired many creative works, such as murals, sculptures, novels, plays, movies and video games. The response of British artists and writers to Brexit has in general been negative, reflecting a reported overwhelming percentage of people involved in Britain's creative industries voting against leaving the European Union.[348] Despite issues around immigration being central in the Brexit debate, British artists left the migrants' perspective largely unexplored. However, Brexit also inspired UK-based migrant artists to create new works and "claim agency over their representation within public spaces and create a platform for a new social imagination that can facilitate transnational and trans-local encounters, multicultural democratic spaces, sense of commonality, and solidarity."[349]

David Cameron placed himself on a collision course with the Tory right when he mounted a passionate defence of Britain's membership of the EU and rejected out of hand an "in or out" referendum.

Cameron said he would continue to work for "a different, more flexible and less onerous position for Britain within the EU".