Corea del Norte , [c] oficialmente la República Popular Democrática de Corea ( RPDC ), [d] es un país del este de Asia . Constituye la mitad norte de la península de Corea y limita con China y Rusia al norte en los ríos Yalu (Amnok) y Tumen , y con Corea del Sur al sur en la Zona Desmilitarizada de Corea . [e] La frontera occidental del país está formada por el mar Amarillo , mientras que su frontera oriental está definida por el mar de Japón . Corea del Norte, al igual que su homóloga del sur , afirma ser el único gobierno legítimo de toda la península y las islas adyacentes . Pyongyang es la capital y ciudad más grande.

La península de Corea fue habitada por primera vez en el Paleolítico Inferior . Su primer reino aparece registrado en los registros chinos a principios del siglo VII a. C. Tras la unificación de los Tres Reinos de Corea en Silla y Balhae a finales del siglo VII, Corea fue gobernada por la dinastía Goryeo (918-1392) y la dinastía Joseon (1392-1897). El Imperio coreano (1897-1910) que le siguió fue anexado en 1910 al Imperio del Japón . En 1945, tras la rendición japonesa al final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial , Corea se dividió en dos zonas a lo largo del paralelo 38 , con el norte ocupado por la Unión Soviética y el sur ocupado por los Estados Unidos . En 1948, se formaron gobiernos separados en Corea: la República Popular Democrática de Corea, socialista y alineada con la Unión Soviética , en el norte, y la República de Corea, capitalista y alineada con Occidente , en el sur. La Guerra de Corea comenzó cuando las fuerzas norcoreanas invadieron Corea del Sur en 1950. En 1953, el Acuerdo de Armisticio de Corea provocó un alto el fuego y estableció una zona desmilitarizada (DMZ), pero nunca se firmó un tratado de paz formal . Corea del Norte de posguerra se benefició enormemente de la ayuda económica y la experiencia proporcionada por otros países del Bloque del Este . Sin embargo, Kim Il Sung , el primer líder de Corea del Norte, promovió su filosofía personal de Juche como ideología estatal . El aislamiento internacional de Pyongyang se aceleró drásticamente a partir de la década de 1980 en adelante cuando la Guerra Fría llegó a su fin. La caída de la Unión Soviética en 1991 provocó un fuerte declive de la economía norcoreana. De 1994 a 1998, Corea del Norte sufrió una hambruna y la población siguió sufriendo desnutrición. En 2024, la RPDC abandonó formalmente los esfuerzos para reunificar pacíficamente a Corea . [11]

Corea del Norte es una dictadura totalitaria con un culto integral a la personalidad en torno a la familia Kim . Amnistía Internacional considera que el país tiene el peor historial de derechos humanos del mundo. Oficialmente, Corea del Norte es un " estado socialista independiente " [f] que celebra elecciones democráticas ; sin embargo, los observadores externos han descrito las elecciones como injustas, poco competitivas y predeterminadas, de manera similar a las elecciones en la Unión Soviética . El Partido de los Trabajadores de Corea es el partido gobernante de Corea del Norte. Según el artículo 3 de la constitución, el kimilsungismo-kimjongilismo es la ideología oficial de Corea del Norte. Los medios de producción son propiedad del estado a través de empresas estatales y granjas colectivizadas . La mayoría de los servicios, como la atención médica , la educación , la vivienda y la producción de alimentos , están subvencionados o financiados por el estado.

Corea del Norte sigue la política Songun , que da prioridad al Ejército Popular de Corea en los asuntos de Estado y en la asignación de recursos. Posee armas nucleares . Su ejército en servicio activo, compuesto por 1,28 millones de soldados, es el cuarto más grande del mundo. Además de ser miembro de las Naciones Unidas desde 1991, Corea del Norte también es miembro del Movimiento de Países No Alineados , del G77 y del Foro Regional de la ASEAN .

La ortografía moderna de Corea apareció por primera vez en 1671 en los escritos de viaje de Hendrick Hamel de la Compañía Holandesa de las Indias Orientales . [13]

Después de la división del país en Corea del Norte y Corea del Sur, las dos partes utilizaron términos diferentes para referirse a Corea: Chosun o Joseon ( 조선 ) en Corea del Norte, y Hanguk ( 한국 ) en Corea del Sur. En 1948, Corea del Norte adoptó la República Popular Democrática de Corea ( en coreano : 조선민주주의인민공화국 , Chosŏn Minjujuŭi Inmin Konghwaguk ; ) como su nombre oficial. En el resto del mundo, debido a que su gobierno controla la parte norte de la península de Corea , se la llama comúnmente Corea del Norte para distinguirla de Corea del Sur, que oficialmente se llama República de Corea en inglés. Ambos gobiernos se consideran el gobierno legítimo de toda Corea . [14] [15] Por esta razón, la gente no se considera a sí misma como “norcoreanos”, sino como coreanos en el mismo país dividido que sus compatriotas en el Sur, y se desalienta a los visitantes extranjeros de utilizar el primer término. [16]

Según la mitología coreana , en el año 2333 a. C., el reino de Gojoseon fue establecido por el dios-rey Dangun . Tras la unificación de los Tres Reinos de Corea bajo el Imperio de Silla Unificado en el año 668 d. C., Corea fue gobernada posteriormente por la dinastía Goryeo (918-1392) y la dinastía Joseon (1392-1897). En 1897, el rey Gojong proclamó el Imperio coreano , que fue anexado por el Imperio del Japón en 1910. [19]

Desde 1910 hasta el final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en 1945, Corea estuvo bajo el dominio japonés . La mayoría de los coreanos eran campesinos dedicados a la agricultura de subsistencia . [20] En la década de 1930, Japón desarrolló minas, represas hidroeléctricas, fábricas de acero y plantas manufactureras en el norte de Corea y la vecina Manchuria . [21] La clase obrera industrial coreana se expandió rápidamente y muchos coreanos fueron a trabajar a Manchuria. [22] Como resultado, el 65% de la industria pesada de Corea estaba ubicada en el norte, pero, debido al terreno accidentado, solo el 37% de su agricultura. [23]

Corea del Norte estuvo poco expuesta a las ideas occidentales modernas. [24] Una excepción parcial fue la penetración de la religión. Desde la llegada de los misioneros a fines del siglo XIX, el noroeste de Corea, y Pyongyang en particular, habían sido un bastión del cristianismo. [25] Como resultado, Pyongyang fue llamada la "Jerusalén del Este". [26]

En el interior montañoso y en Manchuria surgió un movimiento guerrillero coreano que hostigaba a las autoridades imperiales japonesas. Uno de los líderes guerrilleros más destacados fue el comunista Kim Il Sung . [27]

Tras la rendición japonesa al final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en 1945, la península de Corea quedó dividida en dos zonas a lo largo del paralelo 38 , con la mitad norte de la península ocupada por la Unión Soviética y la mitad sur por los Estados Unidos . Las negociaciones para la reunificación fracasaron. El general soviético Terenty Shtykov recomendó el establecimiento de la Administración Civil Soviética en octubre de 1945, y apoyó a Kim Il Sung como presidente del Comité Popular Provisional de Corea del Norte , establecido en febrero de 1946. En septiembre de 1946, los ciudadanos surcoreanos se levantaron contra el Gobierno Militar Aliado . En abril de 1948, un levantamiento de los isleños de Jeju fue aplastado violentamente. El Sur declaró su condición de Estado en mayo de 1948 y dos meses después el ardiente anticomunista Syngman Rhee [28] se convirtió en su gobernante. La República Popular Democrática de Corea se estableció en el Norte el 9 de septiembre de 1948. Shtykov fue el primer embajador soviético, mientras que Kim Il Sung se convirtió en primer ministro.

Las fuerzas soviéticas se retiraron del Norte en 1948, y la mayoría de las fuerzas estadounidenses se retiraron del Sur en 1949. El embajador Shtykov sospechaba que Rhee planeaba invadir el Norte y simpatizaba con el objetivo de Kim de unificar Corea bajo el socialismo. Los dos presionaron con éxito al líder soviético Joseph Stalin para que apoyara una guerra rápida contra el Sur, que culminó con el estallido de la Guerra de Corea. [29] [30] [31] [32]

El ejército de Corea del Norte invadió el Sur el 25 de junio de 1950 y rápidamente invadió la mayor parte del país. El Comando de las Naciones Unidas (UNC) se estableció posteriormente después de que el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU reconociera la agresión norcoreana contra Corea del Sur. La moción fue aprobada porque la Unión Soviética , un aliado cercano de Corea del Norte y miembro del Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU, estaba boicoteando a la ONU por su reconocimiento de la República de China en lugar de la República Popular China . [33] El UNC, liderado por los Estados Unidos, intervino para defender el Sur y avanzó rápidamente hacia Corea del Norte. Cuando se acercaron a la frontera con China, las fuerzas chinas intervinieron en nombre de Corea del Norte, cambiando nuevamente el equilibrio de la guerra. Los combates terminaron el 27 de julio de 1953, con un armisticio que restauró aproximadamente las fronteras originales entre Corea del Norte y Corea del Sur, pero no se firmó ningún tratado de paz. [34] Aproximadamente 3 millones de personas murieron en la Guerra de Corea, con una cifra proporcional de muertes civiles mayor que la Segunda Guerra Mundial o la Guerra de Vietnam . [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] En términos per cápita y absolutos, Corea del Norte fue el país más devastado por la guerra, que resultó en la muerte de un estimado de 12-15% de la población norcoreana ( c. 10 millones), "una cifra cercana o superior a la proporción de ciudadanos soviéticos muertos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial ", según Charles K. Armstrong . [40] Como resultado de la guerra, casi todos los edificios importantes en Corea del Norte fueron destruidos. [41] [42] Algunos se han referido al conflicto como una guerra civil, con otros factores involucrados. [43]

La península sigue dividida por una zona desmilitarizada fuertemente vigilada y en Corea del Sur persiste un sentimiento anticomunista y antinorcoreano. Desde la guerra, Estados Unidos ha mantenido una fuerte presencia militar en el Sur , que el gobierno norcoreano describe como una fuerza de ocupación imperialista. [44] Afirma que la Guerra de Corea fue causada por Estados Unidos y Corea del Sur. [45]

En la posguerra, en los años 1950 y 1960, se produjo un cambio ideológico en Corea del Norte, ya que Kim Il Sung intentó consolidar su poder. Kim Il Sung fue muy crítico del primer ministro soviético Nikita Khrushchev y sus políticas de desestalinización y criticó a Khrushchev como revisionista. [46] Durante el Incidente de la Facción de Agosto de 1956 , Kim Il Sung resistió con éxito los esfuerzos de la Unión Soviética y China para deponerlo en favor de los coreanos soviéticos o la facción pro china Yan'an . [47] [48] Algunos académicos creen que el incidente de agosto de 1956 fue un ejemplo de la demostración de independencia política de Corea del Norte. [47] [48] [49] Sin embargo, la mayoría de los académicos consideran que la retirada final de las tropas chinas de Corea del Norte en octubre de 1958 es la última fecha en la que Corea del Norte se volvió efectivamente independiente. A finales de la década de 1950 y principios de la de 1960, Corea del Norte intentó distinguirse internacionalmente convirtiéndose en líder del Movimiento de Países No Alineados y promoviendo la ideología del Juche . [50] En la formulación de políticas de los Estados Unidos, Corea del Norte era considerada entre las naciones cautivas . [51] A pesar de sus esfuerzos por escapar de las esferas de influencia soviética y china, Corea del Norte permaneció estrechamente alineada con ambos países durante la Guerra Fría. [52]

La industria era el sector favorecido en Corea del Norte. La producción industrial volvió a los niveles de preguerra en 1957. En 1959, las relaciones con Japón habían mejorado un poco, y Corea del Norte comenzó a permitir la repatriación de ciudadanos japoneses en el país. El mismo año, Corea del Norte revaluó el won norcoreano , que tenía un mayor valor que su contraparte surcoreana. Hasta la década de 1960, el crecimiento económico fue mayor que en Corea del Sur, y el PIB per cápita norcoreano era igual al de su vecino del sur hasta 1976. [53] Sin embargo, en la década de 1980, la economía había comenzado a estancarse; comenzó su largo declive en 1987 y colapsó casi por completo después de la disolución de la Unión Soviética en 1991, cuando se detuvo repentinamente toda la ayuda soviética. [54]

Un estudio interno de la CIA reconoció varios logros del gobierno norcoreano después de la guerra: atención compasiva a los huérfanos de guerra y a los niños en general, una mejora radical en el estatus de las mujeres, vivienda gratuita, atención médica gratuita y estadísticas de salud particularmente en expectativa de vida y mortalidad infantil que eran comparables incluso a las de las naciones más avanzadas hasta la hambruna norcoreana . [55] La expectativa de vida en el Norte era de 72 años antes de la hambruna, que era solo marginalmente menor que en el Sur. [56] El país alguna vez se jactó de un sistema de atención médica comparativamente desarrollado; antes de la hambruna, Corea del Norte tenía una red de casi 45.000 médicos de familia con unos 800 hospitales y 1.000 clínicas. [57]

La relativa paz entre el Norte y el Sur tras el armisticio se vio interrumpida por escaramuzas fronterizas, secuestros de celebridades e intentos de asesinato. El Norte fracasó en varios intentos de asesinato de líderes surcoreanos, como en 1968 , 1974 y el atentado de Rangún en 1983; se encontraron túneles bajo la DMZ y las tensiones estallaron por el incidente del asesinato con hacha en Panmunjom en 1976. [58] Durante casi dos décadas después de la guerra, los dos estados no buscaron negociar entre sí. En 1971, comenzaron a realizarse contactos secretos de alto nivel que culminaron en la Declaración Conjunta Sur-Norte del 4 de julio de 1972 que estableció los principios de trabajo hacia la reunificación pacífica. Las conversaciones finalmente fracasaron porque en 1973, Corea del Sur declaró su preferencia de que las dos Coreas buscaran membresías separadas en organizaciones internacionales. [59]

La Unión Soviética se disolvió el 26 de diciembre de 1991, poniendo fin a su ayuda y apoyo a Corea del Norte. En 1992, cuando la salud de Kim Il Sung comenzó a deteriorarse, su hijo Kim Jong Il comenzó a asumir lentamente diversas tareas estatales. Kim Il Sung murió de un ataque cardíaco en 1994 ; Kim Jong Il declaró un período de tres años de duelo nacional, después de lo cual anunció oficialmente su posición como nuevo líder. [60]

Corea del Norte prometió detener su desarrollo de armas nucleares bajo el Marco Acordado , negociado con el presidente estadounidense Bill Clinton y firmado en 1994. Basándose en la Nordpolitik , Corea del Sur comenzó a relacionarse con el Norte como parte de su Política del Sol . [61] [62] Kim Jong Il instituyó una política llamada Songun , o "lo militar primero". [63]

Las inundaciones de mediados de los años 1990 exacerbaron la crisis económica, causando graves daños a los cultivos y a la infraestructura y provocando una hambruna generalizada que el gobierno no pudo controlar, y que causó la muerte de entre 240.000 y 420.000 personas. En 1996, el gobierno aceptó la ayuda alimentaria de las Naciones Unidas. [64]

El entorno internacional cambió cuando George W. Bush se convirtió en presidente de los Estados Unidos en 2001. Su administración rechazó la Política de Transparencia de Corea del Sur y el Marco Acordado. Bush incluyó a Corea del Norte en su eje del mal en su Discurso sobre el Estado de la Unión de 2002. En consecuencia, el gobierno de los Estados Unidos trató a Corea del Norte como un estado rebelde , mientras que Corea del Norte redobló sus esfuerzos para adquirir armas nucleares. [65] [66] [67] El 9 de octubre de 2006, Corea del Norte anunció que había realizado su primera prueba de armas nucleares . [68] [69]

El presidente estadounidense Barack Obama adoptó una política de "paciencia estratégica", resistiéndose a hacer acuerdos con Corea del Norte. [70] Las tensiones con Corea del Sur y los Estados Unidos aumentaron en 2010 con el hundimiento del buque de guerra surcoreano Cheonan [71] y el bombardeo de Corea del Norte a la isla Yeonpyeong . [72] [73]

El 17 de diciembre de 2011, Kim Jong Il murió de un ataque cardíaco . Su hijo menor, Kim Jong Un, fue anunciado como su sucesor. [74] Ante la condena internacional, Corea del Norte continuó desarrollando su arsenal nuclear, que posiblemente incluya una bomba de hidrógeno y un misil capaz de alcanzar los Estados Unidos. [75]

A lo largo de 2017, tras el ascenso de Donald Trump a la presidencia de Estados Unidos, las tensiones entre Estados Unidos y Corea del Norte aumentaron, y hubo una retórica intensificada entre los dos, con Trump amenazando con "fuego y furia" si Corea del Norte alguna vez atacaba territorio estadounidense [76] en medio de amenazas norcoreanas de probar misiles que aterrizarían cerca de Guam . [77] Las tensiones disminuyeron sustancialmente en 2018 y se desarrolló una distensión . [78] Se llevaron a cabo una serie de cumbres entre Kim Jong Un de Corea del Norte, el presidente Moon Jae-in de Corea del Sur y el presidente Trump. [79]

El 10 de enero de 2021, Kim Jong Un fue elegido formalmente como Secretario General en el 8º Congreso del Partido de los Trabajadores de Corea , un título que anteriormente ostentaba Kim Jong Il. [80] El 24 de marzo de 2022, Corea del Norte realizó con éxito un lanzamiento de prueba de un misil balístico intercontinental por primera vez desde la crisis de 2017. [81] En septiembre de 2022, Corea del Norte aprobó una ley que se declaraba un estado nuclear . [82]

El 30 de diciembre de 2023, el líder norcoreano Kim Jong-un declaró provocativamente que Corea del Sur era un "estado vasallo colonial", [83] lo que marca un cambio significativo con respecto a la postura de larga data de reclamos mutuos sobre toda la península de Corea por parte de Corea del Norte y Corea del Sur. Esta declaración fue seguida por un llamado el 15 de enero de 2024 a una enmienda constitucional para redefinir la frontera con Corea del Sur como la "Frontera Nacional del Sur", lo que intensificó aún más la retórica contra Corea del Sur. Kim Jong-un también declaró que en caso de una guerra, Corea del Norte buscaría anexar la totalidad de Corea del Sur. [84]

Corea del Norte ocupa la parte norte de la península de Corea , situada entre las latitudes 37° y 43° N y las longitudes 124° y 131° E. Cubre un área de 120.540 kilómetros cuadrados (46.541 millas cuadradas). [2] Al oeste se encuentran el mar Amarillo y la bahía de Corea , y al este se encuentra Japón al otro lado del mar de Japón .

Los primeros visitantes europeos a Corea comentaron que el país se parecía a "un mar en un fuerte vendaval" debido a las muchas cadenas montañosas sucesivas que atraviesan la península. [85] Alrededor del 80 por ciento de Corea del Norte está compuesto de montañas y tierras altas, separadas por valles profundos y estrechos. Todas las montañas de la península de Corea con elevaciones de 2000 metros (6600 pies) o más se encuentran en Corea del Norte. El punto más alto de Corea del Norte es la montaña Paektu , una montaña volcánica con una elevación de 2744 metros (9003 pies) sobre el nivel del mar. [85] Considerado un lugar sagrado por los norcoreanos, el monte Paektu tiene importancia en la cultura coreana y ha sido incorporado al elaborado folclore y culto a la personalidad en torno a la familia Kim. [86] Por ejemplo, la canción "Iremos al monte Paektu" canta en alabanza a Kim Jong Un y describe una caminata simbólica a la montaña. Otras cordilleras importantes son la cordillera Hamgyong en el extremo noreste y las montañas Rangrim , que se encuentran en la parte centro-norte de Corea del Norte. El monte Kumgang en la cordillera Taebaek , que se extiende hasta Corea del Sur, es famoso por su belleza escénica. [85]

Las llanuras costeras son amplias en el oeste y discontinuas en el este. Una gran mayoría de la población vive en las llanuras y tierras bajas. Según un informe del Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente de 2003, los bosques cubren más del 70 por ciento del país, principalmente en pendientes pronunciadas. [87] Corea del Norte tuvo una puntuación media del Índice de Integridad del Paisaje Forestal de 2019 de 8,02/10, lo que la sitúa en el puesto 28 a nivel mundial de 172 países. [88] El río más largo es el río Amnok (Yalu), que fluye durante 790 kilómetros (491 millas). [89] El país contiene tres ecorregiones terrestres: los bosques caducifolios de Corea del Centro , los bosques mixtos de las montañas Changbai y los bosques mixtos de Manchuria . [90]

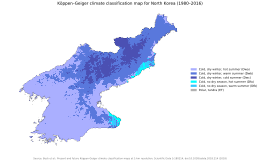

Corea del Norte tiene un clima continental húmedo según el sistema de clasificación climática de Köppen . Los inviernos traen un clima despejado intercalado con tormentas de nieve como resultado de los vientos del norte y noroeste que soplan desde Siberia . [91] El verano tiende a ser, con diferencia, la época más calurosa, húmeda y lluviosa del año debido a los vientos monzónicos del sur y sureste que transportan aire húmedo desde el océano Pacífico . Aproximadamente el 60 por ciento de todas las precipitaciones se producen entre junio y septiembre. [91] La primavera y el otoño son estaciones de transición entre el verano y el invierno. Las temperaturas máximas y mínimas medias diarias de Pyongyang son de -3 y -13 °C (27 y 9 °F) en enero y de 29 y 20 °C (84 y 68 °F) en agosto. [91]

Corea del Norte funciona como una dictadura totalitaria de partido único altamente centralizada . [92] [93] [94] [95] Según su constitución , es un estado autodenominado revolucionario y socialista "guiado en su construcción y actividades solo por el gran kimilsungismo-kimjongilismo". [96] Además de la constitución, Corea del Norte se rige por los Diez Principios para el Establecimiento de un Sistema Ideológico Monolítico (también conocidos como los "Diez Principios del Sistema de Una Ideología") que establecen estándares para el gobierno y una guía para los comportamientos de los norcoreanos. [97] El Partido de los Trabajadores de Corea (WPK), un partido comunista dirigido por un miembro de la familia Kim , [98] [99] tiene aproximadamente 6,5 millones de miembros [100] y controla la política norcoreana. Tiene dos partidos satélites, el Partido Socialdemócrata de Corea y el Partido Chondoísta Chongu . [101]

Kim Jong Un de la familia Kim es el actual Líder Supremo o Suryeong de Corea del Norte. [102] Dirige todas las principales estructuras de gobierno: es el secretario general del Partido de los Trabajadores de Corea y presidente de Asuntos de Estado . [103] [104] Su abuelo Kim Il Sung, el fundador y líder de Corea del Norte hasta su muerte en 1994, es el " presidente eterno " del país , [105] mientras que su padre Kim Jong Il, que sucedió a Kim Il Sung como líder, fue anunciado "Secretario General Eterno" y "Presidente Eterno de la Comisión de Defensa Nacional" después de su muerte en 2011. [103]

Según la Constitución, oficialmente existen tres ramas principales de gobierno. La primera de ellas es la Comisión de Asuntos Estatales (SAC), que actúa como "el órgano supremo de orientación nacional de la soberanía estatal". [106] [107] Su función es deliberar y decidir el trabajo de construcción de la defensa del Estado, incluidas las principales políticas del Estado, y llevar a cabo las instrucciones del presidente de la comisión, Kim Jong Un. [108] La SAC también supervisa directamente el Ministerio de Defensa , el Ministerio de Seguridad del Estado y el Ministerio de Seguridad Social . [108]

El poder legislativo está en manos de la Asamblea Popular Suprema (APS), unicameral. [109] Sus 687 miembros son elegidos cada cinco años por sufragio universal , [110] aunque los observadores externos han descrito las elecciones como similares a las de la Unión Soviética . [111] [112] Las elecciones en Corea del Norte también han sido descritas como una forma de censo gubernamental, debido a la participación cercana al 100%. Aunque las elecciones no son pluralistas , los medios estatales norcoreanos describen las elecciones como "una expresión del apoyo y la confianza absolutos de todos los votantes en el gobierno de la RPDC". [113] [114] Las sesiones de la Asamblea Popular Suprema son convocadas por el Comité Permanente de la APS, cuyo presidente ( Choe Ryong-hae desde 2019) es el tercer funcionario de mayor rango en Corea del Norte. [115] Los diputados eligen formalmente al presidente, vicepresidentes y miembros del Comité Permanente y participan en las actividades constitucionalmente designadas de la legislatura: aprobar leyes, establecer políticas internas y externas, nombrar a los miembros del gabinete, revisar y aprobar el plan económico estatal, entre otras. [116] La propia SPA no puede iniciar ninguna legislación independientemente de los órganos del partido o del estado. Se desconoce si alguna vez ha criticado o enmendado los proyectos de ley que se le presentan, y las elecciones se basan en una lista única de candidatos aprobados por el WPK que se presentan sin oposición. [117]

El poder ejecutivo recae en el Gabinete de Corea del Norte , encabezado por el primer ministro Kim Tok Hun desde el 14 de agosto de 2020, [118] quien es oficialmente el segundo funcionario de mayor rango después de Kim Jong Un. [115] El primer ministro representa al gobierno y funciona de forma independiente. Su autoridad se extiende a dos viceprimeros ministros, 30 ministros , dos presidentes de comisiones del gabinete, el secretario jefe del gabinete, el presidente del Banco Central , el director de la Oficina Central de Estadísticas y el presidente de la Academia de Ciencias . [119]

Corea del Norte, al igual que su contraparte del sur, afirma ser el gobierno legítimo de toda la península de Corea y las islas adyacentes. [120] A pesar de su título oficial como "República Popular Democrática de Corea", algunos observadores han descrito el sistema político de Corea del Norte como una "dictadura hereditaria". [121] [122] [123] También se la ha descrito como una dictadura estalinista . [124] [125] [126] [127]

El kimilsungismo-kimjongilismo es la ideología oficial de Corea del Norte y del PTC, y es la piedra angular de las obras del partido y las operaciones gubernamentales. [96] El Juche , parte del kimilsungismo-kimjongilismo más amplio junto con el Songun bajo Kim Jong Un, [128] es visto por la línea oficial norcoreana como una encarnación de la sabiduría de Kim Il Sung, una expresión de su liderazgo y una idea que proporciona "una respuesta completa a cualquier pregunta que surja en la lucha por la liberación nacional". [129] El Juche fue pronunciado en diciembre de 1955 en un discurso llamado Sobre la eliminación del dogmatismo y el formalismo y el establecimiento del Juche en el trabajo ideológico para enfatizar una revolución centrada en Corea. [129] Sus principios básicos son la autosuficiencia económica , la autosuficiencia militar y una política exterior independiente. Las raíces del Juche se componen de una compleja mezcla de factores, entre ellos la popularidad de Kim Il Sung, el conflicto con los disidentes prosoviéticos y prochinos y la lucha de siglos de Corea por la independencia. [130] El Juche fue introducido en la constitución en 1972. [131] [132]

El Juche fue inicialmente promovido como una "aplicación creativa" del marxismo-leninismo , pero a mediados de la década de 1970, fue descrito por la propaganda estatal como "el único pensamiento científico... y la estructura teórica revolucionaria más efectiva que conduce al futuro de la sociedad comunista". [ cita requerida ] El Juche eventualmente reemplazó al marxismo-leninismo por completo en la década de 1980, [133] y en 1992 las referencias a este último fueron omitidas de la constitución. [134] La constitución de 2009 eliminó las referencias al comunismo y elevó la política de Songun militar primero al tiempo que confirmaba explícitamente la posición de Kim Jong Il. [135] Sin embargo, la constitución conserva referencias al socialismo. [136] El WPK reafirmó su compromiso con el comunismo en 2021. [137] Los conceptos de autosuficiencia de Juche han evolucionado con el tiempo y las circunstancias, pero aún proporcionan la base para la austeridad espartana, el sacrificio y la disciplina que exige el partido. [138] El académico Brian Reynolds Myers ve la ideología actual de Corea del Norte como un nacionalismo étnico coreano similar al estatismo en el Japón Shōwa y al fascismo europeo . [139] [140] [141]

Desde la fundación de la nación, el liderazgo supremo de Corea del Norte ha permanecido dentro de la familia Kim, a la que en Corea del Norte se le conoce como el linaje del Monte Paektu . Es un linaje de tres generaciones que desciende del primer líder del país, Kim Il Sung, quien desarrolló Corea del Norte en torno a la ideología Juche y se mantuvo en el poder hasta su muerte. [142] Kim desarrolló un culto a la personalidad estrechamente vinculado a la filosofía estatal del Juche, que luego se transmitió a sus sucesores: su hijo Kim Jong Il en 1994 y su nieto Kim Jong Un en 2011. En 2013, la Cláusula 2 del Artículo 10 de los Diez Principios Fundamentales del Partido de los Trabajadores de Corea recientemente editados declaró que el partido y la revolución deben ser llevados "eternamente" por el "linaje del Monte Paektu". [143]

Según New Focus International , el culto a la personalidad, particularmente en torno a Kim Il Sung, ha sido crucial para legitimar la sucesión hereditaria de la familia. [144] El control que el gobierno norcoreano ejerce sobre muchos aspectos de la cultura de la nación se utiliza para perpetuar el culto a la personalidad en torno a Kim Il Sung, [145] y Kim Jong Il. [146] Durante una visita a Corea del Norte en 1979, el periodista Bradley Martin escribió que casi toda la música, el arte y la escultura que observó glorificaban al "Gran Líder" Kim Il Sung, cuyo culto a la personalidad se estaba extendiendo entonces a su hijo, el "Querido Líder" Kim Jong Il. [147]

Las afirmaciones de que la familia ha sido deificada son refutadas por BR Myers: "Nunca se han atribuido poderes divinos a ninguno de los dos Kim. De hecho, el aparato de propaganda en Pyongyang generalmente ha sido cuidadoso de no hacer afirmaciones que contradigan directamente la experiencia de los ciudadanos o el sentido común". [148] Explica además que la propaganda estatal pintó a Kim Jong Il como alguien cuya experiencia radicaba en asuntos militares y que la hambruna de los años 1990 fue causada en parte por desastres naturales fuera del control de Kim Jong Il. [149]

La canción " No Motherland Without You ", cantada por el coro del ejército norcoreano, fue creada especialmente para Kim Jong Il y es una de las melodías más populares del país. Kim Il Sung todavía es reverenciado oficialmente como el "Presidente Eterno" de la nación. Varios lugares de interés en Corea del Norte llevan el nombre de Kim Il Sung , incluida la Universidad Kim Il Sung , el Estadio Kim Il Sung y la Plaza Kim Il Sung . Se ha citado a desertores diciendo que las escuelas norcoreanas deifican tanto al padre como al hijo. [150] Kim Il Sung rechazó la noción de que había creado un culto a su alrededor y acusó a quienes sugirieron esto de " faccionalismo ". [151] Después de la muerte de Kim Il Sung, los norcoreanos se postraron y lloraron ante una estatua de bronce de él en un evento organizado; [152] escenas similares fueron transmitidas por la televisión estatal después de la muerte de Kim Jong Il. [153]

Los críticos sostienen que el culto a la personalidad de Kim Jong Il fue heredado de su padre. Kim Jong Il era a menudo el centro de atención a lo largo de la vida cotidiana. Su cumpleaños es uno de los días festivos públicos más importantes del país . En su 60º cumpleaños (según su fecha oficial de nacimiento), se produjeron celebraciones masivas en todo el país. [154] El culto a la personalidad de Kim Jong Il, aunque significativo, no era tan extenso como el de su padre. Un punto de vista es que el culto a la personalidad de Kim Jong Il era únicamente por respeto a Kim Il Sung o por miedo al castigo por no rendir homenaje, [155] mientras que fuentes del gobierno norcoreano lo consideran un auténtico culto al héroe. [156]

.jpg/440px-North_Korea_-_China_friendship_(5578914865).jpg)

Como resultado de su aislamiento, Corea del Norte es a veces conocida como el " reino ermitaño ", un término que originalmente se refería al aislacionismo en la última parte de la dinastía Joseon . [157] Inicialmente, Corea del Norte tenía vínculos diplomáticos solo con otros países comunistas, e incluso hoy, la mayoría de las embajadas extranjeras acreditadas en Corea del Norte se encuentran en Pekín en lugar de en Pyongyang . [158] En las décadas de 1960 y 1970, siguió una política exterior independiente, estableció relaciones con muchos países en desarrollo y se unió al Movimiento de Países No Alineados . A fines de la década de 1980 y en la de 1990, su política exterior se vio sacudida con el colapso del Bloque Soviético . Sufriendo una crisis económica, cerró varias de sus embajadas. Al mismo tiempo, Corea del Norte buscó construir relaciones con países desarrollados de libre mercado. [159]

Corea del Norte se unió a las Naciones Unidas en 1991 junto con Corea del Sur . Corea del Norte también es miembro del Movimiento de Países No Alineados , el G77 y el Foro Regional de la ASEAN . [160] En 2015 [update], Corea del Norte tenía relaciones diplomáticas con 166 países y embajadas en 47 países. [159] Corea del Norte no tiene relaciones diplomáticas con Argentina , Botsuana , [161] Estonia , Francia , [162] Irak , Israel , Japón , Taiwán , [163] Estados Unidos , [g] y Ucrania . [164] [165] [166] Alemania es inusual en mantener una embajada de Corea del Norte. El embajador alemán Friedrich Lohr dice que la mayor parte de su tiempo en Corea del Norte implicó facilitar la entrega de ayuda humanitaria y asistencia agrícola a una población plagada de escasez de alimentos. [167]

_05.jpg/440px-Kim_Jong-un_and_Vladimir_Putin_(2019-04-25)_05.jpg)

Corea del Norte disfruta de una estrecha relación con China , a la que a menudo se considera el aliado más cercano de Corea del Norte. [168] [169] Las relaciones se tensaron a partir de 2006 debido a las preocupaciones de China sobre el programa nuclear de Corea del Norte. [170] Las relaciones mejoraron después de que Xi Jinping , secretario general del Partido Comunista Chino y presidente chino, visitara Corea del Norte en abril de 2019. [171] Corea del Norte sigue teniendo fuertes lazos con varios países del sudeste asiático como Vietnam , Laos , Camboya , [172] e Indonesia . Las relaciones con Malasia se tensaron en 2017 por el asesinato de Kim Jong-nam . Corea del Norte tiene una estrecha relación con Rusia y ha expresado su apoyo a la invasión rusa de Ucrania . [173] [174]

Corea del Norte fue designada previamente como estado patrocinador del terrorismo por los EE. UU . [175] debido a su presunta participación en el atentado de Rangún de 1983 y el atentado de 1987 contra un avión de pasajeros de Corea del Sur . [176] El 11 de octubre de 2008, los Estados Unidos eliminaron a Corea del Norte de su lista de estados que patrocinan el terrorismo después de que Pyongyang aceptara cooperar en cuestiones relacionadas con su programa nuclear. [177] Corea del Norte fue designada nuevamente como estado patrocinador del terrorismo por los EE. UU. bajo la administración de Donald Trump el 20 de noviembre de 2017 después de que continuaran las pruebas nucleares. [178] El secuestro de al menos 13 ciudadanos japoneses por agentes norcoreanos en las décadas de 1970 y 1980 ha tenido un efecto perjudicial en la relación de Corea del Norte con Japón. [179]

El presidente estadounidense Trump se reunió con Kim en Singapur el 12 de junio de 2018. Se firmó un acuerdo entre los dos países en el que se respaldaba la Declaración de Panmunjom de 2017 firmada por Corea del Norte y Corea del Sur, en la que se comprometían a trabajar para desnuclearizar la península de Corea. [180] Se reunieron en Hanoi del 27 al 28 de febrero de 2019, pero no lograron llegar a un acuerdo. [181] El 30 de junio de 2019, Trump se reunió con Kim junto con el presidente surcoreano Moon Jae-in en la DMZ de Corea. [182]

La Zona Desmilitarizada de Corea con Corea del Sur sigue siendo la frontera más fortificada del mundo. [183] [184] Las relaciones intercoreanas son el núcleo de la diplomacia norcoreana y han experimentado numerosos cambios en las últimas décadas. La política de Corea del Norte es buscar la reunificación sin lo que considera una interferencia externa, a través de una estructura federal que retenga el liderazgo y los sistemas de cada lado. En 1972, las dos Coreas acordaron en principio lograr la reunificación por medios pacíficos y sin interferencia extranjera. [185] El 10 de octubre de 1980, el entonces líder norcoreano Kim Il Sung propuso una federación entre Corea del Norte y Corea del Sur llamada República Federal Democrática de Corea en la que inicialmente permanecerían los respectivos sistemas políticos. [186] Sin embargo, las relaciones se mantuvieron frías hasta principios de la década de 1990, con un breve período a principios de la década de 1980 cuando Corea del Norte ofreció proporcionar ayuda por las inundaciones a su vecino del sur. [187] Aunque la oferta fue recibida con agrado en un principio, las conversaciones sobre cómo entregar los suministros de socorro fracasaron y ninguna de las ayudas prometidas cruzó la frontera. [188] Los dos países también organizaron una reunión de 92 familias separadas. [189]

La Política del Sol instituida por el presidente surcoreano Kim Dae-jung en 1998 fue un hito en las relaciones intercoreanas. Alentó a otros países a colaborar con el Norte, lo que permitió a Pyongyang normalizar las relaciones con varios estados de la Unión Europea y contribuyó al establecimiento de proyectos económicos conjuntos Norte-Sur. La culminación de la Política del Sol fue la cumbre intercoreana de 2000 , cuando Kim Dae-jung visitó a Kim Jong Il en Pyongyang. [190] Tanto Corea del Norte como Corea del Sur firmaron la Declaración Conjunta Norte-Sur del 15 de junio , en la que ambas partes prometieron buscar la reunificación pacífica. [191] El 4 de octubre de 2007, el presidente surcoreano Roh Moo-hyun y Kim Jong Il firmaron un acuerdo de paz de ocho puntos. [192] Sin embargo, las relaciones empeoraron cuando el presidente surcoreano Lee Myung-bak adoptó un enfoque de línea más dura y suspendió las entregas de ayuda en espera de la desnuclearización del Norte. En 2009, Corea del Norte respondió poniendo fin a todos sus acuerdos previos con el Sur. [193] Desplegó misiles balísticos adicionales [194] y puso a su ejército en alerta máxima de combate después de que Corea del Sur, Japón y los Estados Unidos amenazaran con interceptar un vehículo de lanzamiento espacial Unha-2 . [195] Los siguientes años fueron testigos de una serie de hostilidades, incluida la presunta participación de Corea del Norte en el hundimiento del buque de guerra surcoreano Cheonan , [71] el fin mutuo de las relaciones diplomáticas, [196] un ataque de artillería norcoreano en la isla Yeonpyeong , [197] y la creciente preocupación internacional por el programa nuclear de Corea del Norte. [198]

En mayo de 2017, Moon Jae-in fue elegido presidente de Corea del Sur con la promesa de volver a la Política del Sol. [199] En febrero de 2018, se desarrolló una distensión en los Juegos Olímpicos de Invierno celebrados en Corea del Sur. [78] En abril, el presidente surcoreano Moon Jae-in y Kim Jong Un se reunieron en la DMZ y, en la Declaración de Panmunjom , se comprometieron a trabajar por la paz y el desarme nuclear. [200] En septiembre, en una conferencia de prensa conjunta en Pyongyang, Moon y Kim acordaron convertir la península de Corea en una "tierra de paz sin armas nucleares ni amenazas nucleares". [201]

En enero de 2024, Corea del Norte anunció oficialmente a través de su líder Kim Jong Un que ya no buscaría la reunificación con Corea del Sur. En cambio, Kim pidió "ocupar, subyugar y recuperar por completo" Corea del Sur si estalla la guerra. [202] Kim Jong Un también anunció a la Asamblea Popular Suprema que la constitución debería modificarse de manera que Corea del Sur fuera considerada el "enemigo principal e invariable" de Corea del Norte. [203] Además, se cerraron las agencias gubernamentales encargadas de promover la reunificación. [204]

.jpg/440px-AIR_KORYO_IL76_P912_AT_SONDOK_HAMHUNG_AIRPORT_DPR_KOREA_OCT_2012_(8179381094).jpg)

Se estima que las fuerzas armadas de Corea del Norte, o Ejército Popular de Corea (KPA), están compuestas por 1.280.000 efectivos activos y 6.300.000 de reserva y paramilitares, lo que la convierte en una de las instituciones militares más grandes del mundo . [205] Con un ejército en servicio activo que consiste en el 4,9% de su población, Corea del Norte mantiene la cuarta fuerza militar activa más grande del mundo detrás de China, India y Estados Unidos. [206] Alrededor del 20 por ciento de los hombres de entre 17 y 54 años sirven en las fuerzas armadas regulares, [206] y aproximadamente uno de cada 25 ciudadanos es un soldado alistado. [207] [208]

El KPA se divide en cinco ramas: Fuerza Terrestre , Armada , Fuerza Aérea y Antiaérea , Fuerza de Operaciones Especiales y Fuerza de Cohetes . El mando del KPA recae tanto en la Comisión Militar Central del Partido de los Trabajadores de Corea como en la Comisión de Asuntos Estatales independiente, que controla el Ministerio de Defensa . [209]

De todas las ramas del KPA, la Fuerza Terrestre es la más grande, compuesta por aproximadamente un millón de efectivos divididos en 80 divisiones de infantería , 30 brigadas de artillería , 25 brigadas de guerra especial, 20 brigadas mecanizadas, 10 brigadas de tanques y siete regimientos de tanques . [210] Está equipada con 3.700 tanques, 2.100 vehículos blindados de transporte de personal y vehículos de combate de infantería , [211] 17.900 piezas de artillería, 11.000 cañones antiaéreos [212] y unos 10.000 MANPADS y misiles guiados antitanque . [213] Se estima que la Fuerza Aérea posee alrededor de 1.600 aeronaves (entre 545 y 810 cumplen funciones de combate), mientras que la Armada opera aproximadamente 800 buques, incluida la flota de submarinos más grande del mundo. [205] [214] La Fuerza de Operaciones Especiales del KPA es también la unidad de fuerzas especiales más grande del mundo. [214]

Corea del Norte es un estado con armas nucleares , [207] [215] aunque la naturaleza y la fuerza del arsenal del país son inciertas. A septiembre de 2023 [update], las estimaciones de su tamaño oscilaban entre 40 y 116 ojivas nucleares ensambladas . [216] Las capacidades de lanzamiento [217] las proporciona la Fuerza de Cohetes, que tiene unos 1.000 misiles balísticos con un alcance de hasta 11.900 km (7.400 mi). [218]

Según una evaluación de Corea del Sur de 2004, Corea del Norte también posee un arsenal de armas químicas estimado entre 2.500 y 5.000 toneladas, incluidos agentes nerviosos, vesicantes, sanguíneos y vomitivos, así como la capacidad de cultivar y producir armas biológicas, incluido el ántrax , la viruela y el cólera . [219] [220] Como resultado de sus pruebas nucleares y de misiles, Corea del Norte ha sido sancionada en virtud de las resoluciones del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas 1695 de julio de 2006, 1718 de octubre de 2006, 1874 de junio de 2009, 2087 de enero de 2013, [221] y 2397 en diciembre de 2017.

La venta de armas a Corea del Norte por parte de otros estados está prohibida por las sanciones de la ONU, y las capacidades convencionales del KPA están limitadas por una serie de factores, entre ellos equipos obsoletos, suministros de combustible insuficientes y escasez de activos de comando y control digitales . Para compensar estas deficiencias, el KPA ha desplegado una amplia gama de tecnologías de guerra asimétrica , incluidos láseres cegadores antipersonal, [222] bloqueadores de GPS , [223] submarinos enanos y torpedos humanos , [224] pintura furtiva , [225] y unidades de guerra cibernética . [226] En 2015, se informó que Corea del Norte empleaba a 6.000 personas sofisticadas en seguridad informática en una unidad de guerra cibernética que operaba desde China. [227] Las unidades del KPA fueron culpadas por el hackeo de Sony Pictures en 2014 [227] y supuestamente han intentado bloquear los satélites militares de Corea del Sur . [228]

Gran parte del equipo que utiliza el KPA está diseñado y fabricado por la industria de defensa nacional . Las armas se fabrican en aproximadamente 1.800 plantas subterráneas de la industria de defensa repartidas por todo el país, la mayoría de ellas ubicadas en la provincia de Chagang . [229] La industria de defensa es capaz de producir una gama completa de armas operadas individualmente y por tripulación, artillería, vehículos blindados, tanques, misiles, helicópteros, submarinos, naves de desembarco e infiltración y entrenadores Yak-18 , e incluso puede tener una capacidad limitada de fabricación de aviones a reacción. [230] Según los medios estatales de Corea del Norte, el gasto militar ascendió al 15,8 por ciento del presupuesto estatal en 2010. [231] El Departamento de Estado de Estados Unidos ha estimado que el gasto militar de Corea del Norte promedió el 23% de su PIB de 2004 a 2014, el nivel más alto del mundo. [232] Corea del Norte probó con éxito un nuevo tipo de misil balístico lanzado desde submarinos el 19 de octubre de 2021. [233]

Corea del Norte tiene un sistema de derecho civil basado en el modelo prusiano e influenciado por las tradiciones japonesas y la teoría jurídica comunista. [234] Los procedimientos judiciales son manejados por el Tribunal Central (el tribunal de apelación más alto ), los tribunales provinciales o especiales a nivel de ciudad, los tribunales populares y los tribunales especiales. Los tribunales populares están en el nivel más bajo del sistema y operan en ciudades, condados y distritos urbanos, mientras que diferentes tipos de tribunales especiales manejan casos relacionados con asuntos militares, ferroviarios o marítimos. [235]

Los jueces son elegidos por sus respectivas asambleas populares locales, pero esta votación tiende a ser anulada por el Partido de los Trabajadores de Corea. El código penal se basa en el principio de nullum crimen sine lege (no hay delito sin ley), pero sigue siendo una herramienta de control político a pesar de varias enmiendas que reducen la influencia ideológica. [235] Los tribunales llevan a cabo procedimientos legales relacionados no solo con asuntos penales y civiles, sino también con casos políticos. [236] Los presos políticos son enviados a campos de trabajo , mientras que los delincuentes criminales son encarcelados en un sistema separado. [237]

El Ministerio de Seguridad Social mantiene la mayoría de las actividades de aplicación de la ley. Es una de las instituciones estatales más poderosas de Corea del Norte y supervisa la fuerza policial nacional, investiga los casos criminales y administra las instalaciones penitenciarias no políticas. [238] Se ocupa de otros aspectos de la seguridad interna, como el registro civil, el control del tráfico, los departamentos de bomberos y la seguridad ferroviaria. [239] El Ministerio de Seguridad del Estado se separó del Ministerio de Seguridad Pública en 1973 para realizar inteligencia nacional y extranjera, contrainteligencia y administrar el sistema de prisiones políticas. Los campamentos políticos pueden ser zonas de reeducación de corto plazo o " kwalliso " (zonas de control total) para detención de por vida. [240] El Campo 15 en Yodok [241] y el Campo 18 en Pukchang [242] han sido descritos en testimonios detallados. [243]

El aparato de seguridad es amplio [230] y ejerce un control estricto sobre la residencia, los viajes, el empleo, la vestimenta, la alimentación y la vida familiar. [244] Las fuerzas de seguridad emplean una vigilancia masiva . Se cree que vigilan estrechamente las comunicaciones celulares y digitales. [245]

El estado de los derechos humanos en Corea del Norte ha sido ampliamente condenado. Una investigación de la ONU de 2014 sobre el historial de derechos humanos de la RPDC encontró evidencia de "violaciones sistemáticas, generalizadas y graves de los derechos humanos" y afirmó que "la gravedad, escala y naturaleza de estas violaciones revelan un estado que no tiene paralelo en el mundo contemporáneo", [247] con Amnistía Internacional y Human Rights Watch manteniendo puntos de vista similares. [248] [249] [250] Los norcoreanos han sido referidos como "algunas de las personas más brutalizadas del mundo" por Human Rights Watch , debido a las severas restricciones impuestas a sus libertades políticas y económicas . [249] [250] La población norcoreana está estrictamente controlada por el estado y todos los aspectos de la vida diaria están subordinados a la planificación del partido y del estado. Según informes del gobierno de los EE. UU., el empleo es administrado por el partido sobre la base de la confiabilidad política, y los viajes están estrictamente controlados por el Ministerio de Seguridad Popular. [251] El Departamento de Estado de Estados Unidos dice que los norcoreanos no tienen elección en los trabajos que realizan y no son libres de cambiar de trabajo a voluntad. [252]

Existen restricciones a la libertad de asociación, expresión y movimiento; la detención arbitraria, la tortura y otros malos tratos tienen como resultado la muerte y la ejecución. [253] En Corea del Norte, por lo general, no se permite a los ciudadanos salir del país [254] a voluntad y su gobierno niega el acceso a los observadores de derechos humanos de las Naciones Unidas. [255]

El Ministerio de Seguridad del Estado detiene y encarcela extrajudicialmente a los acusados de delitos políticos sin el debido proceso. [256] Las personas percibidas como hostiles al gobierno, como los cristianos o los críticos del liderazgo, [257] son deportadas a campos de trabajo sin juicio, [258] a menudo con toda su familia y en su mayoría sin ninguna posibilidad de ser liberados. [259] El trabajo forzoso es parte de un sistema establecido de represión política . [252]

Según las imágenes satelitales y los testimonios de desertores, se calcula que unos 200.000 prisioneros están recluidos en seis grandes campos de prisioneros [257] [260] , donde se les obliga a trabajar para enmendar sus malas acciones. [261] Los partidarios del gobierno que se desvían de la línea gubernamental son sometidos a reeducación en secciones de campos de trabajo destinadas a ese fin. Aquellos que se consideran políticamente rehabilitados pueden volver a asumir puestos gubernamentales responsables tras su liberación. [262]

La Comisión de Investigación de las Naciones Unidas ha acusado a Corea del Norte de crímenes contra la humanidad . [263] [264] [265] La Coalición Internacional para Detener los Crímenes contra la Humanidad en Corea del Norte (ICNK) estima que más de 10.000 personas mueren en los campos de prisioneros de Corea del Norte cada año. [266]

Con 1.100.000 personas en esclavitud moderna (a través del trabajo forzado), Corea del Norte ocupa el puesto más alto del mundo en términos de porcentaje de población en esclavitud moderna, con un 10,4 por ciento esclavizado según el Índice de Esclavitud Global 2018 de Walk Free . [267] [268] Corea del Norte es el único país del mundo que no ha criminalizado explícitamente ninguna forma de esclavitud moderna. [269] Un informe de las Naciones Unidas incluyó la esclavitud entre los crímenes contra la humanidad que ocurren en Corea del Norte. [270]

Según el Departamento de Estado de los EE.UU., el gobierno de Corea del Norte no cumple plenamente con los estándares mínimos para la eliminación de la trata de personas y no está haciendo esfuerzos significativos para hacerlo. [252] Corea del Norte ha traficado a miles de sus propios ciudadanos supuestamente como trabajadores forzados a Rusia, [271] Polonia, [272] Malasia, [273] varias partes de África [274] y el Golfo Pérsico [275] donde la mayor parte de las ganancias de los trabajadores se las embolsa Pyongyang. [276]

El gobierno norcoreano rechaza las acusaciones de abuso de los derechos humanos, [277] [278] [279] calificándolas de campaña de desprestigio y de extorsión de derechos humanos para derrocar al gobierno. [280] [281] [282] En un informe de 2014 a la ONU, Corea del Norte desestimó las acusaciones de atrocidades como rumores descabellados. [277] El medio de comunicación estatal oficial, KCNA , respondió con un artículo que incluía insultos homofóbicos contra el autor del informe de derechos humanos, Michael Kirby , llamándolo "un viejo libertino repugnante con una carrera de homosexualidad de más de 40 años... Esta práctica nunca se puede encontrar en la RPDC que se jacta de una mentalidad sana y una buena moral... De hecho, es ridículo que tales homosexuales [ sic ] patrocinen el trato con los problemas de derechos humanos de otros". [278] [279] El gobierno, sin embargo, admitió algunos problemas de derechos humanos relacionados con las condiciones de vida y declaró que está trabajando para mejorarlos. [282]

.jpg/440px-Mirae_Scientists_Street_-_Nordkorea_2015_-_Pjöngjang_(22971791331).jpg)

Corea del Norte ha mantenido una de las economías más cerradas y centralizadas del mundo desde la década de 1940. [283] Durante varias décadas, siguió el modelo soviético de planes quinquenales con el objetivo final de lograr la autosuficiencia. El amplio apoyo soviético y chino permitió a Corea del Norte recuperarse rápidamente de la Guerra de Corea y registrar tasas de crecimiento muy altas. La ineficiencia sistemática comenzó a surgir alrededor de 1960, cuando la economía pasó de la etapa de desarrollo extensivo a la intensiva . La escasez de mano de obra calificada, energía, tierra cultivable y transporte impidió significativamente el crecimiento a largo plazo y resultó en un fracaso constante en el cumplimiento de los objetivos de planificación. [284] La importante desaceleración de la economía contrastó con Corea del Sur, que superó al Norte en términos de PIB absoluto e ingreso per cápita en la década de 1980. [285] Corea del Norte declaró que el último plan de siete años había fracasado en diciembre de 1993 y, a partir de entonces, dejó de anunciar planes. [286]

La pérdida de socios comerciales del Bloque del Este y una serie de desastres naturales a lo largo de la década de 1990 causaron graves penurias, incluida una hambruna generalizada . Para el año 2000, la situación mejoró debido a un esfuerzo masivo de asistencia alimentaria internacional, pero la economía sigue sufriendo escasez de alimentos, infraestructura en ruinas y un suministro de energía críticamente bajo. [287] En un intento por recuperarse del colapso, el gobierno inició reformas estructurales en 1998 que legalizaron formalmente la propiedad privada de activos y descentralizaron el control sobre la producción. [288] Una segunda ronda de reformas en 2002 condujo a una expansión de las actividades de mercado, monetización parcial , precios y salarios flexibles y la introducción de incentivos y técnicas de rendición de cuentas. [289] A pesar de estos cambios, Corea del Norte sigue siendo una economía dirigida donde el Estado posee casi todos los medios de producción y las prioridades de desarrollo son definidas por el gobierno. [287]

Corea del Norte tiene el perfil estructural de un país relativamente industrializado [290] , donde casi la mitad del producto interno bruto es generado por la industria [291] y el desarrollo humano se encuentra en niveles medios. [292] El PIB en paridad de poder adquisitivo (PPA) se estima en 40 mil millones de dólares, [5] con un valor per cápita muy bajo de 1.800 dólares. [6] En 2012, el ingreso nacional bruto per cápita fue de 1.523 dólares, en comparación con los 28.430 dólares de Corea del Sur. [293] El won norcoreano es la moneda nacional, emitida por el Banco Central de la República Popular Democrática de Corea . [294] La economía se ha desarrollado de manera espectacular en los últimos años a pesar de las sanciones. El Instituto Sejong describe estos cambios como "asombrosos". [295]

La economía está fuertemente nacionalizada. [296] La comida y la vivienda están ampliamente subsidiadas por el estado; la educación y la atención médica son gratuitas; [297] y el pago de impuestos fue abolido oficialmente en 1974. [298] Una variedad de bienes están disponibles en grandes almacenes y supermercados en Pyongyang, [299] aunque la mayoría de la población depende de mercados de jangmadang a pequeña escala . [300] [301] En 2009, el gobierno intentó frenar la expansión del libre mercado prohibiendo el jangmadang y el uso de moneda extranjera, [287] devaluando fuertemente el won y restringiendo la convertibilidad de los ahorros en la antigua moneda, [302] pero el pico de inflación resultante y las raras protestas públicas causaron una reversión de estas políticas. [303] El comercio privado está dominado por mujeres porque la mayoría de los hombres deben estar presentes en su lugar de trabajo, a pesar de que muchas empresas estatales no están operativas. [304]

.jpg/440px-Masikryong_North_Korea_Ski_Resort_(12300043424).jpg)

La industria y los servicios emplean al 65% [305] de los 12,6 millones de trabajadores de Corea del Norte. [306] Las principales industrias incluyen la construcción de maquinaria, el equipo militar, los productos químicos, la minería, la metalurgia, los textiles, el procesamiento de alimentos y el turismo. [307] La producción de mineral de hierro y carbón se encuentran entre los pocos sectores en los que Corea del Norte se desempeña significativamente mejor que su vecino del sur : produce aproximadamente 10 veces más de cada recurso. [308] Utilizando plataformas de perforación exrumanas, varias compañías de exploración petrolera han confirmado importantes reservas de petróleo en la plataforma norcoreana del Mar de Japón y en áreas al sur de Pyongyang. [309] El sector agrícola fue destrozado por los desastres naturales de la década de 1990. [310] Sus 3.500 cooperativas y granjas estatales [311] tuvieron un éxito moderado hasta mediados de la década de 1990 [312], pero ahora experimentan una escasez crónica de fertilizantes y equipos. El arroz, el maíz, la soja y las patatas son algunos de los cultivos principales. [287] Una contribución significativa al suministro de alimentos proviene de la pesca comercial y la acuicultura . [287] Las granjas especializadas más pequeñas, administradas por el estado, también producen cultivos de alto valor, incluidos el ginseng , la miel , el matsutake y las hierbas para la medicina tradicional coreana y china . [313] El turismo ha sido un sector en crecimiento durante la última década. [314] Corea del Norte ha tenido como objetivo aumentar el número de visitantes extranjeros a través de proyectos como la estación de esquí de Masikryong . [315] El 22 de enero de 2020, Corea del Norte cerró sus fronteras a los turistas extranjeros en respuesta a la amenaza de la pandemia de COVID-19 en Corea del Norte . [316]

El comercio exterior superó los niveles previos a la crisis en 2005 y continúa expandiéndose. [317] [318] Corea del Norte tiene varias zonas económicas especiales (ZEE) y regiones administrativas especiales donde las empresas extranjeras pueden operar con incentivos fiscales y arancelarios mientras que los establecimientos norcoreanos obtienen acceso a tecnología mejorada. [319] Inicialmente existían cuatro de esas zonas, pero produjeron poco éxito en general. [320] El sistema de ZEE se revisó en 2013 cuando se abrieron 14 nuevas zonas y se reformó la Zona Económica Especial de Rason como un proyecto conjunto chino-norcoreano. [321] La Región Industrial de Kaesong es una zona económica especial donde más de 100 empresas surcoreanas emplean a unos 52.000 trabajadores norcoreanos. [322] A agosto de 2017 [update], China es el mayor socio comercial de Corea del Norte fuera del comercio intercoreano, representando más del 84% del comercio exterior total ($5.3 mil millones), seguido de India con una participación del 3,3% ($205 millones). [323] En 2014, Rusia canceló el 90% de la deuda de Corea del Norte y los dos países acordaron realizar todas las transacciones en rublos . [324] En general, el comercio exterior en 2013 alcanzó un total de 7.300 millones de dólares (la cantidad más alta desde 1990 [325] ), mientras que el comercio intercoreano cayó a un mínimo de ocho años de 1.100 millones de dólares. [326]

La infraestructura de transporte en Corea del Norte incluye ferrocarriles, autopistas, rutas acuáticas y aéreas, pero el transporte ferroviario es, con diferencia, el más extendido. Corea del Norte tiene unos 5.200 kilómetros (3.200 millas) de vías férreas, en su mayoría de ancho estándar, que transportan el 80% del tráfico anual de pasajeros y el 86% del transporte de mercancías, pero la escasez de electricidad socava su eficiencia. [327] La construcción de un ferrocarril de alta velocidad que conecta Kaesong, Pyongyang y Sinuiju con velocidades superiores a 200 kilómetros por hora (120 mph) fue aprobada en 2013. [328] [ necesita actualización ] Corea del Norte se conecta con el Ferrocarril Transiberiano a través de Rajin .

El transporte por carretera es muy limitado: solo 724 kilómetros (450 mi) de los 25.554 kilómetros (15.879 mi) de la red de carreteras están pavimentados, [329] y el mantenimiento de la mayoría de las carreteras es deficiente. [330] Solo el 2% de la capacidad de carga se sustenta en el transporte fluvial y marítimo, y el tráfico aéreo es insignificante. [327] Todas las instalaciones portuarias están libres de hielo y albergan una flota mercante de 158 buques. [331] Ochenta y dos aeropuertos [332] y 23 helipuertos [333] están operativos y el más grande sirve a la aerolínea estatal, Air Koryo . [327] Los automóviles son relativamente raros, [334] pero las bicicletas son comunes. [335] [336] Solo hay un aeropuerto internacional , el Aeropuerto Internacional de Pyongyang , al que prestan servicio Rusia y China (consulte la Lista de aeropuertos públicos de Corea del Norte ).

La infraestructura energética de Corea del Norte está obsoleta y en mal estado. La escasez de energía es crónica y no se aliviaría ni siquiera con importaciones de electricidad porque la red mal mantenida causa pérdidas significativas durante la transmisión. [338] [339] El carbón representa el 70% de la producción de energía primaria, seguido de la energía hidroeléctrica con el 17%. [327] El gobierno de Kim Jong Un ha aumentado el énfasis en proyectos de energía renovable como parques eólicos, parques solares, calefacción solar y biomasa . [340] Un conjunto de regulaciones legales adoptadas en 2014 enfatizaron el desarrollo de la energía geotérmica, eólica y solar junto con el reciclaje y la conservación del medio ambiente. [340] [341] El objetivo a largo plazo de Corea del Norte es frenar el uso de combustibles fósiles y alcanzar una producción de 5 millones de kilovatios de fuentes renovables para 2044, frente a su total actual de 430.000 kilovatios de todas las fuentes. Se proyecta que la energía eólica satisfaga el 15% de la demanda total de energía del país bajo esta estrategia. [342]

Corea del Norte también se esfuerza por desarrollar su propio programa nuclear civil. Estos esfuerzos son objeto de muchas controversias internacionales debido a sus aplicaciones militares y a las preocupaciones sobre la seguridad. [343]

Los esfuerzos de I+D se concentran en la Academia Estatal de Ciencias, que gestiona 40 institutos de investigación, 200 centros de investigación más pequeños, una fábrica de equipos científicos y seis editoriales. [344] El gobierno considera que la ciencia y la tecnología están directamente vinculadas al desarrollo económico. [345] [346] A principios de la década de 2000 se llevó a cabo un plan científico quinquenal que enfatizaba la TI, la biotecnología, la nanotecnología, la tecnología marina y la investigación con láser y plasma. [345] Un informe de 2010 del Instituto de Política Científica y Tecnológica de Corea del Sur identificó la química de polímeros , los materiales de un solo carbono, la nanociencia , las matemáticas, el software, la tecnología nuclear y la cohetería como áreas potenciales de cooperación científica intercoreana. Los institutos norcoreanos son fuertes en estos campos de investigación, aunque sus ingenieros requieren capacitación adicional y los laboratorios necesitan actualizaciones de equipos. [347]

Bajo el lema “construir una poderosa economía del conocimiento ”, el Estado ha lanzado un proyecto para concentrar la educación, la investigación científica y la producción en una serie de “zonas de desarrollo de alta tecnología”. Las sanciones internacionales siguen siendo un obstáculo importante para su desarrollo. [348] La red de bibliotecas electrónicas Miraewon se creó en 2014 bajo lemas similares. [349]

Se han asignado importantes recursos al programa espacial nacional, que está gestionado por la Administración Nacional de Tecnología Aeroespacial (anteriormente gestionada por el Comité Coreano de Tecnología Espacial hasta abril de 2013). [350] [351] Los vehículos de lanzamiento de producción nacional y la clase de satélites Kwangmyŏngsŏng se lanzan desde dos puertos espaciales , el Campo de Lanzamiento de Satélites Tonghae y la Estación de Lanzamiento de Satélites Sohae . Después de cuatro intentos fallidos, Corea del Norte se convirtió en la décima nación espacial con el lanzamiento de la Unidad 2 de Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 en diciembre de 2012, que alcanzó la órbita con éxito pero se creía que estaba averiada y no operativa. [352] [353] Se unió al Tratado del Espacio Ultraterrestre en 2009 [354] y ha declarado sus intenciones de emprender misiones tripuladas y a la Luna . [351] El gobierno insistió en que el programa espacial tiene fines pacíficos, pero Estados Unidos, Japón, Corea del Sur y otros países sostuvieron que sirve para avanzar en el programa de misiles balísticos de Corea del Norte. [355] El 7 de febrero de 2016, una declaración transmitida por la Televisión Central de Corea dijo que un nuevo satélite de observación de la Tierra, Kwangmyongsong-4 , había sido puesto en órbita con éxito. [356]

El uso de la tecnología de las comunicaciones está controlado por el Ministerio de Correos y Telecomunicaciones . Existe un sistema telefónico de fibra óptica adecuado a nivel nacional con 1,18 millones de líneas fijas [357] y una cobertura móvil en expansión. [9] La mayoría de los teléfonos están instalados para funcionarios gubernamentales de alto rango y la instalación requiere una explicación por escrito de por qué el usuario necesita un teléfono y cómo se pagará. [358] La cobertura celular está disponible con una red 3G operada por Koryolink , una empresa conjunta con Orascom Telecom Holding . [359] El número de suscriptores ha aumentado de 3.000 en 2002 [360] a casi dos millones en 2013. [359] Las llamadas internacionales a través de servicios fijos o celulares están restringidas y no está disponible Internet móvil . [359]

El acceso a Internet en sí está limitado a un puñado de usuarios de élite y científicos. En cambio, Corea del Norte tiene un sistema de intranet amurallado llamado Kwangmyong , [361] que es mantenido y monitoreado por el Centro de Computación de Corea . [362] Su contenido se limita a los medios estatales, servicios de chat, foros de mensajes, [361] un servicio de correo electrónico y un estimado de 1000 a 5500 sitios web. [363] Las computadoras emplean el sistema operativo Red Star , un sistema operativo derivado de Linux , con un shell de usuario visualmente similar al de OS X. [ 363] El 19 de septiembre de 2016, un proyecto TLDR notó que los datos de DNS de Internet de Corea del Norte y el dominio de nivel superior se dejaron abiertos, lo que permitió transferencias de zona DNS globales. Un volcado de los datos descubiertos se compartió en GitHub . [10] [364]

La población de Corea del Norte era de 10,9 millones en 1961. [365] Con la excepción de una pequeña comunidad china y unos pocos japoneses étnicos, los 25.971.909 habitantes de Corea del Norte [366] [367] son étnicamente homogéneos. [368] Los expertos demográficos del siglo XX estimaron que la población crecería a 25,5 millones en 2000 y a 28 millones en 2010, pero este aumento nunca se produjo debido a la hambruna norcoreana . [369] La hambruna comenzó en 1995, duró tres años y provocó la muerte de entre 240.000 y 420.000 norcoreanos. [64]

Los donantes internacionales encabezados por los Estados Unidos iniciaron envíos de alimentos a través del Programa Mundial de Alimentos en 1997 para combatir la hambruna. [370] A pesar de una drástica reducción de la ayuda bajo la administración de George W. Bush , [371] la situación mejoró gradualmente: el número de niños desnutridos disminuyó del 60% en 1998 [372] al 37% en 2006 [373] y al 28% en 2013. [374] La producción alimentaria nacional casi se recuperó al nivel anual recomendado de 5,37 millones de toneladas de equivalente de cereales en 2013, [375] pero el Programa Mundial de Alimentos informó de una continua falta de diversidad dietética y de acceso a grasas y proteínas. [376] A mediados de la década de 2010, los niveles nacionales de emaciación severa, una indicación de condiciones similares a la hambruna, eran inferiores a los de otros países de bajos ingresos y aproximadamente a la par de los de las naciones en desarrollo del Pacífico y Asia Oriental. La salud y la nutrición de los niños son significativamente mejores en varios indicadores que en muchos otros países asiáticos. [377]

La hambruna tuvo un impacto significativo en la tasa de crecimiento de la población, que se redujo al 0,9% anual en 2002. [369] Fue del 0,5% en 2014. [378] Los matrimonios tardíos después del servicio militar, el espacio limitado para la vivienda y las largas horas de trabajo o estudios políticos agotan aún más a la población y reducen el crecimiento. [369] La tasa de natalidad nacional es de 14,5 nacimientos por año por cada 1.000 habitantes. [379] Dos tercios de los hogares consisten en familias extensas que en su mayoría viven en unidades de dos habitaciones. El matrimonio es prácticamente universal y el divorcio es extremadamente raro. [380]

North Korea shares the Korean language with South Korea, although some dialectal differences exist within both Koreas.[372] North Koreans refer to their Pyongan dialect as munhwaŏ ("cultured language") as opposed to the dialects of South Korea, especially the Seoul dialect or p'yojun'ŏ ("standard language"), which are viewed as decadent because of its use of loanwords from Chinese and European languages (particularly English).[381][382] Words of Chinese, Manchu or Western origin have been eliminated from munhwa along with the usage of Chinese hancha characters.[381] Written language uses only the Chosŏn'gŭl (Hangul) phonetic alphabet, developed under Sejong the Great (1418–1450).[383][384]

.jpg/440px-Chilgol_Church_(15545529301).jpg)

North Korea is officially an atheist state.[385][386] Its constitution guarantees freedom of religion under Article 68, but this principle is limited by the requirement that religion may not be used as a pretext to harm the state, introduce foreign forces, or harm the existing social order.[96][387] Religious practice is therefore restricted,[388][389] despite nominal constitutional protections.[390] Proselytizing is also prohibited due to concerns about foreign influence. The number of Christian churchgoers nonetheless more than doubled between the 1980s and the early 2000s due to the recruitment of Christians who previously worshipped privately or in small house churches.[391] The Open Doors mission, a Protestant group based in the United States and founded during the Cold War era, claims the most severe persecution of Christians in the world occurs in North Korea.[392]

There are no known official statistics of religions in North Korea. According to a 2020 study published by the Centre for the Study of World Christianity, 73% of the population are irreligious (58% agnostic, 15% atheist), 13% practice Chondoism, 12% practice Korean shamanism, 1.5% are Buddhist, and less than 0.5% practice another religion such as Christianity, Islam, or Chinese folk religion.[393] Amnesty International has expressed concerns about religious persecution in North Korea.[254] Pro-North groups such as the Paektu Solidarity Alliance deny these claims, saying that multiple religious facilities exist across the nation.[394] Some religious places of worship are located in foreign embassies in the capital city of Pyongyang.[395] Five Christian churches built with state funds stand in Pyongyang: three Protestant, one Roman Catholic, and one Russian Orthodox.[391] Critics claim these are showcases for foreigners.[396][397]

Buddhism and Confucianism still influence spirituality.[398] Chondoism ("Heavenly Way") is an indigenous syncretic belief combining elements of Korean shamanism, Buddhism, Taoism and Catholicism that is officially represented by the WPK-controlled Chondoist Chongu Party.[399] Chondoism is recognized and favored by the government, being seen as an indigenous form of "revolutionary religion".[387]

.jpg/440px-Laika_ac_Grand_People's_Study_House_(7968604172).jpg)

The 2008 census listed the entire population as literate.[380] An 11-year free, compulsory cycle of primary and secondary education is provided in more than 27,000 nursery schools, 14,000 kindergartens, 4,800 four-year primary and 4,700 six-year secondary schools.[372] 77% of males and 79% of females aged 30–34 have finished secondary school.[380] An additional 300 universities and colleges offer higher education.[372]

Most graduates from the compulsory program do not attend university but begin their obligatory military service or proceed to work in farms or factories instead. The main deficiencies of higher education are the heavy presence of ideological subjects, which comprise 50% of courses in social studies and 20% in sciences,[400] and the imbalances in curriculum. The study of natural sciences is greatly emphasized while social sciences are neglected.[401] Heuristics is actively applied to develop the independence and creativity of students throughout the system.[402] The study of Russian and English was made compulsory in upper middle schools in 1978.[403]

North Korea has a life expectancy of 72.3 years in 2019, according to HDR 2020.[404] While North Korea is classified as a low-income country, the structure of North Korea's causes of death (2013) is unlike that of other low-income countries.[405] Instead, it is closer to worldwide averages, with non-communicable diseases—such as cardiovascular disease and cancers—accounting for 84 percent of the total deaths in 2016.[406]

According to the World Bank report of 2016 (based on WHO's estimate), only 9.5% of the total deaths recorded in North Korea are attributed to communicable diseases and maternal, prenatal and nutrition conditions, a figure which is slightly lower than that of South Korea (10.1%) and one fifth of other low-income countries (50.1%) but higher than that of high income countries (6.7%).[407] Only one out of ten leading causes of overall deaths in North Korea is attributed to communicable diseases (lower respiratory infection), a disease which is reported to have declined by six percent since 2007.[408]

In 2013, cardiovascular disease as a single disease group was reported as the largest cause of death in North Korea.[405] The three major causes of death in North Korea are stroke, COPD and Ischaemic heart disease.[408] Non-communicable diseases risk factors in North Korea include high rates of urbanization, an aging society, and high rates of smoking and alcohol consumption amongst men.[405]

Maternal mortality is lower than other low-income countries, but significantly higher than South Korea and other high income countries, at 89 per 100,000 live births.[409] In 2008 child mortality was estimated to be 45 per 1,000, which is much better than other economically comparable countries. Chad for example had a child mortality rate of 120 per 1,000, despite the fact that Chad was most likely wealthier than North Korea at the time.[56]

Healthcare Access and Quality Index, as calculated by IHME, was reported to stand at 62.3, much lower than that of South Korea.[410]

According to a 2003 report by the United States Department of State, almost 100% of the population has access to water and sanitation.[411] Further, 80% of the population had access to improved sanitation facilities in 2015.[412]

North Korea has the highest number of doctors per capita amongst low-income countries, with 3.7 physicians per 1,000 people, a figure which is also significantly higher than that of South Korea, according to WHO's data.[413]

Conflicting reports between Amnesty and WHO have emerged, where the Amnesty report claimed that North Korea had an inadequate health care system, while the Director of the World Health Organization claimed that North Korea's healthcare system was considered the envy of the developing world and had "no lack of doctors and nurses".[414]

A free universal insurance system is in place.[297] Quality of medical care varies significantly by region[415] and is often low, with severe shortages of equipment, drugs and anesthetics.[302] According to WHO, expenditure on health per capita is one of the lowest in the world.[302] Preventive medicine is emphasized through physical exercise and sports, nationwide monthly checkups and routine spraying of public places against disease. Every individual has a lifetime health card which contains a full medical record.[416]

According to North Korean documents and refugee testimonies,[417] all North Koreans are sorted into groups according to their Songbun, an ascribed status system based on a citizen's assessed loyalty to the government. Based on their own behavior and the political, social, and economic background of their family for three generations as well as behavior by relatives within that range, Songbun is allegedly used to determine whether an individual is trusted with responsibility or given certain opportunities.[418]

Songbun allegedly affects access to educational and employment opportunities and particularly whether a person is eligible to join North Korea's ruling party.[418] There are 3 main classifications and about 50 sub-classifications. According to Kim Il Sung, speaking in 1958, the loyal "core class" constituted 25% of the North Korean population, the "wavering class" 55%, and the "hostile class" 20%.[417] The highest status is accorded to individuals descended from those who participated with Kim Il Sung in the resistance against Japanese occupation before and during World War II and to those who were factory workers, laborers, or peasants in 1950.[419]