The Key lime or acid lime (Citrus × aurantiifolia or C. aurantifolia) is a citrus hybrid (C. hystrix × C. medica) native to tropical Southeast Asia. It has a spherical fruit, 2.5–5 centimetres (1–2 inches) in diameter. The Key lime is usually picked while it is still green, but it becomes yellow when ripe.

The Key lime has thinner rind and is smaller, seedier, more acidic and more aromatic than the Persian lime (Citrus × latifolia). It is valued for its characteristic flavor. The name comes from its association with the Florida Keys, where it is best known as the flavoring ingredient in Key lime pie. It is also known as West Indian lime, bartender's lime, Omani lime, or Mexican lime, the last classified as a distinct race with a thicker skin and darker green colour. Philippine varieties have various names, including dayap and bilolo.[1]

The English word lime was derived, via Spanish then French, from the Arabic word ليمة līma, which is, in turn, a derivation of the Persian word limu لیمو.[2] Key is from Florida Keys, where the fruit was naturalised. The earliest known use of the name is from 1905, where the fruit was described as "the finest on the market. It is aromatic, juicy, and highly superior to the lemon."[3]

C. aurantiifolia is a shrubby tree, growing to 5 metres (16 feet), with many thorns. Dwarf varieties exist that can be grown indoors during winter months and in colder climates. Its trunk, which rarely grows straight, has many branches, and they often originate quite far down on the trunk. The leaves are ovate, 2.5–9 centimetres (1–3+1⁄2 inches) long, resembling orange leaves (the scientific name aurantiifolia referring to this resemblance to the leaves of Citrus aurantium). The flowers are 2.5 cm (1 in) in diameter, are yellowish white with a light purple tinge on the margins. Flowers and fruit appear throughout the year, but are most abundant from May to September in the Northern Hemisphere.[4][5]

Skin contact can sometimes cause phytophotodermatitis,[6][7] which makes the skin especially sensitive to ultraviolet light.

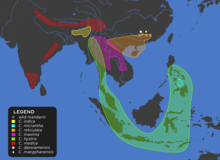

The Key lime cultivar is a citrus hybrid, Citrus micrantha × Citrus medica (a papeda-citron cross).[9][10][11]

The Key lime has given rise to several other lime varieties. The best known, the triploid progeny of a Key lime-lemon cross, is the Persian lime (Citrus × latifolia), the most widely produced lime, globally. Others are, like their parent, classed within C. aurantiifolia. Backcrossing with citron has produced a distinct group of triploid limes that are also of commercial value to a limited degree, the seedy Tanepeo, Coppenrath, Ambilobe and Mohtasseb lime varieties as well as the Madagascar lemon. Hybridization with a mandarin-pomelo cross similar to the oranges has produced the Kirk lime. The New Caledonia and Kaghzi limes appear to have resulted from an F2 Key lime self-pollination, while a spontaneous genomic duplication gave us the tetraploid Giant Key lime.[12][13] The potential to produce a wider variety of lime hybrids from the Key lime due to its tendency to form diploid gametes may reduce the disease risk presented by the limited diversity of the current commercial limes.[14]

C. aurantiifolia es originaria del sudeste asiático . Su aparente ruta de introducción fue a través de Oriente Medio hasta el norte de África , luego a Sicilia y Andalucía y luego, a través de exploradores españoles, a las Indias Occidentales , incluidos los Cayos de Florida . A Henry Perrine se le atribuye la introducción de la lima de los Cayos en Florida. [15] Desde el Caribe, el cultivo de lima se extendió a América del Norte tropical y subtropical, incluidos México , Florida y más tarde California .

En California, a finales del siglo XIX, las limas "mexicanas" eran más valoradas que los limones; sin embargo, en Florida, se las consideraba generalmente malas hierbas. Luego, en 1894-95, la Gran Helada destruyó los limoneros de Florida y los agricultores replantaron limas mexicanas en su lugar; pronto se las conoció como limas de Florida, un "cultivo regional querido". Pero cuando el huracán de Miami de 1926 las arrancó, se las replantó con limas persas más resistentes y sin espinas. [16]

Desde que entró en vigor el Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte , la mayoría de las limas Key que se comercializan en Estados Unidos se cultivan en México, América Central y América del Sur . También se cultivan en Texas , Florida y California.

Existen varios enfoques para el cultivo de limas. Esta variedad de cítrico se puede propagar a partir de semillas y crecerá fiel a la planta progenitora. Las semillas deben mantenerse húmedas hasta que se puedan plantar, ya que no germinarán si se dejan secar. [ cita requerida ] Si las plantas se propagan a partir de semillas, estas deben almacenarse al menos 5 a 6 meses antes de plantarlas. [ 17 ] Alternativamente, la propagación vegetativa a partir de esquejes o por acodo aéreo puede permitir la producción de frutos en el plazo de un año y a partir de líneas de plantas genéticamente más predecibles. Otro método, cavar alrededor de un árbol maduro para cortar las raíces, estimulará la aparición de nuevos brotes que se pueden trasplantar a otra ubicación. [ cita requerida ] Los clones a menudo se injertan por yema [ 18 ] en limón rugoso o naranja amarga para obtener portainjertos fuertes.

It is often advisable to graft the plants onto rootstocks with low susceptibility to gummosis because seedlings generally are highly vulnerable to the disease. Useful rootstocks include wild grapefruit, cleopatra mandarin and tahiti limes.[17] C. macrophylla is also sometimes used as a rootstock in Florida to add vigor.

Climatic conditions and fruit maturation are crucial in cultivation of the lime tree. Under consistently warm conditions potted trees can be planted at any season, whereas in cooler temperate regions it is best to wait for the late winter or early spring. The Key lime tree does best in sunny sites, well-drained soils,[19][20] good air circulation, and protection from cold wind. Because its root system is shallow, the Key lime is planted in trenches or into prepared and broken rocky soil to give the roots a better anchorage and improve the trees' wind resistance. Pruning and topping should be planned to maximise the circulation of air and provide plenty of sunlight. This keeps the crown healthily dry, improves accessibility for harvesting, and discourages the organisms that cause gummosis.[17]

The method of cultivation greatly affects the size and quality of the harvest. Trees cultivated from seedlings take 4–8 years before producing a harvest. They attain their maximal yield at about 10 years of age. Trees produced from cuttings and air layering bear fruit much sooner, sometimes producing fruit (though not a serious harvest) a year after planting. It takes approximately 9 months from the blossom to the fruit. When the fruit have grown to harvesting size and begin to turn yellow they are picked and not clipped. To achieve produce of the highest market value, it is important not to pick the fruit too early in the morning; the turgor is high then, and handling turgid fruit releases the peel oils and may cause spoilage.[17]

Shelf life of Key limes is an important consideration in marketing. The lime still ripens for a considerable time after harvesting, and it is usually stored between 12.5 and 15.5 °C (55–60 °F) at a relative humidity of 75–85%. Special procedures are employed to control the shelf life; for example, applications of growth regulators, fruit wax, fungicides, precise cooling, calcium compounds, silver nitrate, and special packing material. The preferred storage conditions are temperatures of 9–10 °C (48–50 °F) and a humidity over 85%, but even in ideal conditions post-harvesting losses are high.

In India most Key lime producers are small-scale farmers without access to such post-harvesting facilities, but makeshift expedients can be of value. One successful procedure is a coating of coconut oil that improves shelf life, thereby achieving a constant market supply of Key limes.[21]

Key limes are made into black lime by boiling them in brine and drying them. Black lime is a condiment commonly used in the Middle East.

The yield varies depending on the age of the trees. Five- to seven-year-old orchards may yield about 6 t/ha (2.7 tons/acre), with harvests increasing progressively until they stabilise at about 12–18 t/ha (5.4–8 tons/acre). Seedling trees take longer to attain their maximal harvest, but eventually out-yield grafted trees.[17]

The annual Key Lime Festival in Key West, Florida, has been held every year since 2002 over the Independence Day weekend and is a celebration of Key limes in food, drinks, and culture, with a significant emphasis on Key lime pie.[22]